World Journal of AIDS

Vol.2 No.2(2012), Article ID:19723,7 pages DOI:10.4236/wja.2012.22009

Treatment 2.0 Pilot in Vietnam—Early Progress and Challenges

![]()

1Ministry of Health Vietnam, Vietnam Authority for HIV/AIDS Control, Ha Noi, Vietnam; 2World Health Organization, Ha Noi, Vietnam.

Email: mesquitaf@wpro.who.int, mesquitaberkeley@hotmail.com

Received March 30th, 2012; revised April 28th, 2012; accepted May 16th, 2012

Keywords: Treatment 2.0; Vietnam; Innovation in Response

ABSTRACT

Announced in 2010 at the International AIDS Conference in Vienna and pioneered by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) leadership at the global level, Treatment 2.0 is a new approach to the HIV response that encourages innovation, efficiency, and sustainability. Building upon WHO and UNAIDS’ “3 by 5” Initiative, Treatment 2.0 focuses upon scale-up and universal access of life-saving ART treatment through strategic investments and innovations in five priority pillars that include: 1) Optimize drug regimens; 2) Provide point-of-care (POC) and other simplified diagnostic and monitoring tools; 3) Reduce costs; 4) Adapt service delivery; and 5) Mobilize communities [1-3]. The Treatment 2.0 approach is in line with UNAIDS’ 2011-2015 Strategy: Getting to Zero with the vision of, “Zero New infections; Zero discrimination; and Zero AIDSrelated deaths”, and as well as the four strategic directions for the health sector response outlined under WHO’s Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011-2015 [4,5]. At the Sixty-fourth World Health Assembly (WHA) in May 2011, it was formally announced that Vietnam has taken the leadership to pilot Treatment 2.0 in two of its provinces, with support from both the WHO and UNAIDS country offices [6,7]. Given that Vietnam is one of the few countries with a concentrated epidemic to pilot Treatment 2.0, the outcomes and experiences of this initiative can provide valuable insight to other countries who may consider implementation. The objectives of this article are therefore to: 1) Describe the early process for translating Treatment 2.0 concept in Vietnam’s context; and 2) Highlight early progress and challenges.

1. Introduction: Overview of the HIV Epidemic and Response in Vietnam

Since the first case of HIV in Vietnam was identified in 1990, the epidemic has rapidly spread though has remained concentrated amongst key populations at higher risk of HIV exposure—people who inject drugs, female sex workers and men who have sex with men. Sentinel surveillance in 2010 found a prevalence of 17.2% among people who inject drugs 4.6% among female sex workers and 0.26% amongst antenatal women. The Integrated Biological and Behavioral Study (IBBS) in 2009 found that the prevalence among men who have sex with men was 16.7%. According to the Vietnam HIV/AIDS Estimates and Projections 2007-2012, adult HIV prevalence (aged 15 - 49) was 0.44% in 2010. The epidemic in Vietnam has been largely driven by injecting drug use, with more than 70% of reported cases through this mode of transmission [8]. As of September 2011, there were 193,350 people living with HIV (PLHIV) reported through case-reporting system, including 47,030 patients with AIDS and 51,306 deaths due to complications from HIV related diseases.

The HIV program in Vietnam started as a small sub-committee in the 1990s. It has since expanded with many iterations of shifting responsibilities amongst various government offices. In the recent decade, there has been rapid attention and expansion of Vietnam’s HIV response. In 2000, the National Committee for AIDS, Drugs and Prostitution Prevention and Control was established. The Committee includes 16 ministries and mass organizations and is chaired by the Deputy Prime Minister responsible for the social sector. Each member assigns a Vice Minister or official of equivalent rank as its focal point for Committee-related work. Three ministries—the Ministry of Health (AIDS), the Ministry of Public Security (Drugs), and the Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs (Prostitution)—provide planning, technical and secretariat support, and policy and strategy development for the Committee in their respective area. The National Strategy for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control in Vietnam 2004-2010, with vision to 2020, released in 2004, helped set a framework for the current response. Furthermore, the establishment in 2005 of the Vietnamese Administration for HIV/AIDS Control (VAAC), followed by the creation of the Provincial HIV/ AIDS Control Centres (PACs) and their close collaboration with the People’s committee at the provincial level allowed for more coordinated muti-sectorial response. Additional policy since released, to expand and further define the HIV program, include the 2006 Law on Control and Prevention and the 2007 Interpretive Decree for specific clauses of the HIV/AIDS law. International support has also greatly expanded since 2004 to include major donors and international NGOs [8].

2. Commitment and Support to Pilot Treatment 2.0 in Vietnam

Vietnamese government commitment and widespread support from various stakeholders have been critical to the development of the Treatment 2.0 pilot. Several facilitating factors contributed to declaration of government commitment. First, leaders at the Vietnamese Administration of HIV/AIDS Control (VAAC), which leads the implementation of the national HIV response, had already been working to develop a system of integrated service delivery. Treatment 2.0 provided the appropriate direction and platform.

Second, there was strong commitment from the Joint UN Team on HIV, international partners and donors in Vietnam to support VAAC in adapting the global Treatment 2.0 framework. Although initial discussions about Treatment 2.0 were already being held between WHO, UNAIDS and VAAC, a visit and presentation by WHO headquarters representative to national, international partners and civil society, followed by an invitation to Vietnam to present at the World Health Assembly, solidified and formalized VAAC’s interest and commitment to piloting Treatment 2.0, the proposal came also in a time of general consensus amongst key stakeholders around reorganizing the HIV system to promote country ownership and sustainability.

Finally, the widespread media attention resulting from Vietnam’s presentation of a pilot concept at the World Health Assembly led to great interest from the public, in particular people living with HIV (PLHIV) to know more about the pilot and follow progress.

3. Contrasting Pilot Provinces: Can Tho and Dien Bien

VAAC decided that Treatment 2.0 would be piloted in two vastly different provinces of Vietnam: can Tho and Dien Bien (see figure 1). There are several key differences between these two provinces, which make them

Figure 1. Vietnam map with the two pilot provinces.

ideal for a pilot.

Although both provinces have followed similar trends with an injecting drug use driven epidemic, Can Tho’s epidemic is older. Its HIV program, therefore, has been in place for a longer period of time and has received significant support from international donors and partners. Dien Bien’s epidemic and HIV response is relatively new and thus still developing. Dien Bien is also a Northwestern mountainous province, with significant challenges in terms of access to health services.

In contrast Can Tho as a Southern province is more developed with a population that is about evenly split between urban and rural areas. As the pilot rolls out in these two provinces, VAAC is interested in piloting in three additional provinces that have yet to be identified.

4. Treatment 2.0 Pilot: Phased Approach

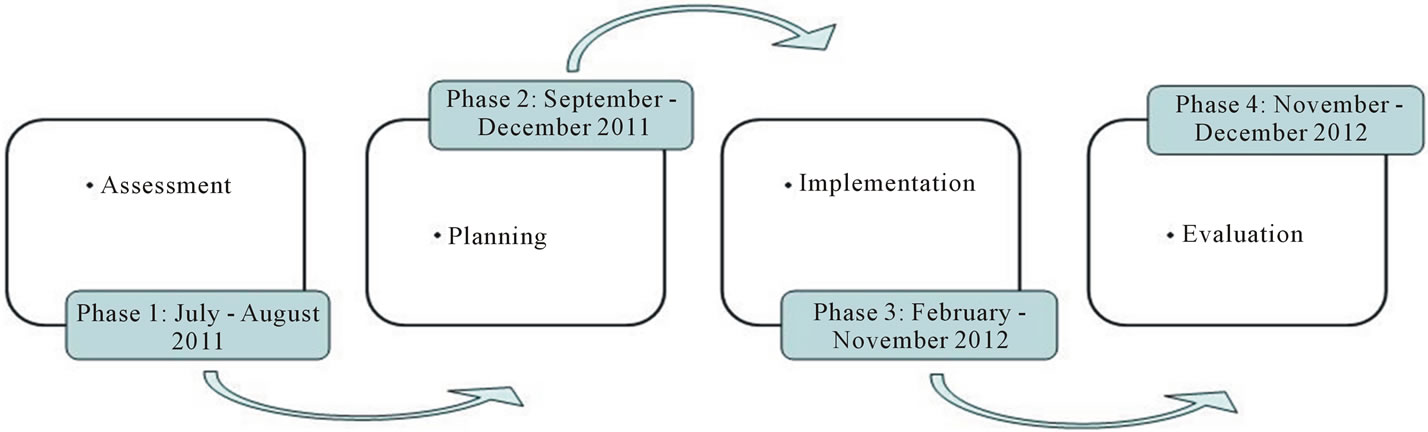

A series of phases for implementing the pilot have been developed (see Figure 2). This includes: 1) Assessment in July-August 2011; 2) Planning in September-December 2011; 3) Implementation from February-November 2012; 4) Evaluation from November-December 2012. Currently, the assessment and planning stages have been completed and first steps of implementation are in place.

4.1. Assessment

The assessment was a joint effort between VAAC, WHO, UNAIDS, and PEPFAR, which composed of two elements. The first was a desk review and compilation of available data from the two provinces. This included data from the government monitoring and evaluation systems, sentinel surveillance, case reports, estimates and projections, and results of projects and surveys from international partners. The second element was field visits to both Can Tho and Dien Bien provinces by a team composed of representatives from the four partners mentioned above. The team met with provincial officials and

Figure 2. Phased approach.

the community to present Treatment 2.0, as well as conduct a review of the existing HIV program and health system infrastructure. The primary goals included gathering additional data not available at the national level, understanding barriers to uptake of health services through meetings with PLHIV and key populations at higher risk peer educators, and understanding the local context in these provinces to inform the planning process.

4.2. Planning

The planning stage greatly expanded the number of collaborators involved to include all major donors, international and national NGOs, PLHIV, key populations at higher risk , health professionals from different levels of the health system, law enforcement agencies, provincial and local authorities from the two provinces among other participants. This consortium of stakeholders proved critical for a number of reasons. As Vietnam reaches middle-income country status and support from development donors is reduced, the nation is at risk of reversing progress made on responding to the HIV epidemic. To prevent and control HIV in the long term, Vietnam must focus its efforts on mobilizing greater and more diverse resources and using those resources effectively. An effective response to HIV focuses on high impact programmes and gives key populations at higher risk (including people who inject drugs, sex workers, men who has sex with men, and their partners) access to quality HIV services. Thus the Treatment 2.0 pilot was seen as an opportunity to further promote country ownership, and to be used as an appropriate platform to gather stakeholders to support short-term planning for a more effective, evidence informed HIV response in Dien Bien and Can Tho.

Second, various partners have different skills and expertise. As extensions from headquarters, both WHO and UNAIDS have defined and complementary expertise, critical for supporting the five priority work areas of Treatment 2.0. For WHO, this is primarily technical expertise focused on adaptation and implementation of evidence-based technical guidance for a simplified and more efficient treatment. UNAIDS’ expertise includes community mobilization, HIV prevention, stigma and discrimination elimination, and cost reduction. Other international partners, however, have varying expertise along the continuum of prevention, treatment and care. The planning process has allowed these partners to apply their greatest areas of expertise to technical working groups focused on the development or adaptation of technical guidance. For example, NIHE, Pasteur Institute in Ho Chi Minh City, US CDC, and WHO have developed technical guidance for a rapid testing algorithm. In addition UNAIDS has used its community mobilization expertise to involve PLHIV and KPA in the planning process and address community concerns.

Third, involvement of PLHIV and key populations at higher risk in the planning process was critical for a country like Vietnam. Low uptake of HIV services has been a cited as a major bottleneck in the HIV response. While there have been some successes in increasing the numbers of key populations at higher risk tested, significant gaps remain. Key populations at higher risk and PLHIV are highly marginalized populations and face high levels of stigma and discrimination. Fears related to protection of confidentiality, stigma, and lack of perceived risk, and fear of HIV diagnosis have been major reasons for low uptake and or late treatment initiation [9-11]. Treatment 2.0 has allowed a platform to include the perspectives of PLHIV and, key populations at higher risk in the planning process to design a system that adequately reaches and supports these communities through strengthened HIV prevention and risk reduction, accessible and confidential counselling and testing, and linkages to high quality adherence and care support.

5. Adapting Treatment 2.0 Pillars for Vietnam

It is recognized that implementing the full range of Treatment 2.0 goals will require significant innovation and long-term development and planning over a number of years [1]. There has been strong encouragement from both UNAIDS/WHO headquarters, however, to not delay and implement as many short-term goals as possible, while beginning to plan for mediumand long-term goals. VAAC has recognized this and together with WHO, UNAIDS and other international partners have been adapting aspects of the five pillars for implementation as part of the pilot.

5.1. Pillar 1: Optimize Drug Regimens

WHO’s 2010 updated guidelines call for earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment (ART) for those with CD4 counts of ≤350 cells/mm3 or WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 as well as drug regimens with reduced toxicity [12]. In Vietnam, a majority of patients initiate ART with CD4 counts ≤100 cells/mm3 [13]. The Treatment 2.0 pilot aims to elevate the average CD4 count at initiation to the newly released WHO standard. This will be linked to strengthening counselling and testing systems to identify HIV infections earlier. As far as drug regimen, Vietnam already has had plans in progress to phase out stavudine (d4T), which has been found to have high levels of toxicity [14,15]. Government procurement will be primarily for tenofovir (TDF) and zidovudine (AZT), and patients on d4T will be transitioned to these regimens. Fixed dose combinations of d4T or AZT, 3TC and nevirapine are already widely in use in Vietnam through funding from Global Fund and PEPFAR. Treatment 2.0 plans to ensure the swift phase-out of d4T and use of available fixed dose combination in the pilot provinces. It is hoped that introducing these changes are important steps towards the less-toxic one-pill-per-day regimen and will promote adherence and improve treatment outcomes.

5.2. Pillar 2: Provide Point-of-Care (POC) and Other Simplified Diagnostic and Monitoring Tools

Implementation and decentralization of rapid testing is the primary short-term focus under this pillar. For Vietnam, this will require a major shift for the HIV program given that current regulations require laboratory-based confirmatory testing, which may delay receipt up results until as long as 2 - 3 weeks later. Stand-a-lone VCT sites have been one major approaches to promote testing. Given low testing rates amongst, key populations at higher risk [11,16,17], however, this has not been enough. Treatment 2.0 plans to institute rapid testing through provider initiated testing and counselling (PITC) in service delivery points as well as widespread anonymous communitybased testing and counselling to better reach , key populations at higher risk. WHO is collaborating with US CDC, NIHE, and the National Reference Laboratory of Australia to develop rapid testing algorithm for these two settings, evaluate test kits already approved in Vietnam, and develop training curriculum. In the first phase of implementation, there will be intense supervision and training to support implementation and to address existing barriers to uptake. Together with Clinton Foundation (CHAI) two point of care simplified CD4 machines will be implemented—one per Province—to pilot same day HIV results plus same day CD4 and ARV initiation in some of the points of care proposed.

5.3. Pillar 3: Reduce Costs

Greater efficiency through integrating and decentralizing the HIV care and treatment and community mobilization are critical for getting people early in treatment, receive all the benefits of ARV treatment and develop long-term sustainability of HIV programs after Treatment 2.0 implementation [3]. It is hoped that implementation of Treatment 2.0 will support earlier identification of cases of HIV through community mobilization, stigma reduction, and improved access to confidential and rapid HIV testing. Earlier identification will allow earlier initiation of ART for those eligible, hopefully in the asymptomatic stage. This would reduce costs from co-morbidities and opportunistic infections and hospitalizations. Both strengthened prevention activities as well as prevention of secondary transmission from patients on ART [18], are expected to prevent new infections and reduce ART costs in the long-term. Furthermore, it is expected that outof-pocket costs will be reduced due to proximity of services to where people live while quality of life years will be also gained.

5.4. Pillar 4: Adapt Service Delivery

This work area is one of the major focuses for the Treatment 2.0 pilot in Vietnam. WHO supported VAAC in identifying areas in various service delivery systems where testing and counselling as well as ART delivery may occur, such as through methadone maintenance treatment clinics, polyclinics, and at commune level health stations. UNAIDS has been working to address major concerns around confidentiality and ensure that these adapted service delivery systems protect human rights and with services that are “client-oriented” toward, key populations at higher risk who have previously cited fears of stigma and discrimination as major barriers to accessing HIV services [9-11]. Due to the unique situation surrounding the history and financing of HIV, Vietnam, similar to many other countries, has developed a vertical HIV system. However, as there was already interest from Vietnam to streamline its HIV system, particularly as donor resources will be dramatically reduced over the next several years, Treatment 2.0 provided a platform to stimulate planning for integration and decentralization. This will include transitioning ART delivery from primarily the provincial or district levels down to the commune or primary care level. This is especially critical for Dien Bien, which is highly mountainous. Thus it is difficult for patients to access medications due to high out-of-pocket costs and the time required to travel to district health centers. Furthermore, integration of PITC and ART delivery with ancillary services at the commune level such as tuberculosis, methadone maintenance treatment, and antenatal care is also planned. Elimination of mother to child transmission of HIV was also agreed in the Province of Can Tho and in the city of Dien Bien. Among the satellites initiatives of Treatment 2.0 pilot, a research protocol will look after the feasibility of using ARV as prevention in all discordant couples of the two Provinces.

5.5. Pillar 5: Mobilize Communities

Community mobilization with integration across the other work areas is the primary area of support from UNAIDS. Low uptake of services, especially counselling and testing and adherence to ART, fuelled by fears of inadequate protection of confidentiality as well as stigma and discrimination have been major barriers [9-11]. UNAIDS has advocated for the inclusion of, key populations at higher risk and PLHIV in all stages of the Treatment 2.0 pilot. The assessment team interviewed, key populations at higher risk peer educators and PLHIV to determine what some of the major barriers are to service uptake in these two provinces. UNAIDS invited PLHIV leaders to a meeting to learn updates for Treatment 2.0 as well as share concerns as a first step for actively engaging and building trust of these community members to participate in the planning process. As part of the actual planning, key populations at higher risk and PLHIV were actively involved with participation from PLHIV and, key populations at higher risk from nation wide and from local organizations. In Dien Bien, representatives of a self-help network of PLHIV urged health authorities to pay due attention to the increased risk of disclosure of HIV status and the resulting stigma and discrimination that people may face when diagnostic and treatment services are brought to commune level. The pilot will need to squarely address this fear of disclosure in order to convince key populations at higher risk to take regular HIV tests, know their sero-status, and start treatment as soon as they are eligible.

6. Translating Treatment 2.0 in Vietnam’s Context: Early Progress and Challenges

6.1. Early Progress

High-level government commitment from VAAC and broad engagement of stakeholders across all levels are considered the greatest early successes. The high level of enthusiasm from VAAC, which became heightened through the WHA presentation and subsequent media attention to Treatment 2.0 has been critical for generating momentum from multiple stakeholders to offer support in essentially redesigning the HIV system. Country-leadership and ownership are critical for sustainability, and Vietnam has demonstrated major interest and support in developing a strengthened and more effective HIV response.

The two planning process (in Dien Bien and Can Tho) have gathered around 120 participants each, demonstrating enthusiasm and commitment from different sectors and key stakeholders in Vietnam. On the global stage, there has been much discussion of shifting resources and large-scale reductions of funding from donors. The Treatment 2.0 pilot acknowledges this, and provides avenues for the country, donors, international NGOs, and other program implementers to review their program priorities and determine where their support and assistance may be the best utilized and cost-effective. Furthermore, the consultation and engagement of, key populations at higher risk and PLHIV in the assessment, planning, and implementation process of Treatment 2.0 has been heavily promoted in recognition that the pilot can only be successful through institutionalizing stigma and discrimination reduction and ensuring that the program will be accessible and acceptable to these community members.

6.2. Challenges

A number of challenges, however, remain. Decentralization of the HIV system requires a large paradigm shift from the current models of very centralized HIV systems. Concerns from some government partners over quality of rapid testing with same day results or use of commune health stations for ART delivery may slow the process of implementing Treatment 2.0. Task shifting and restructuring responsibilities for testing and counselling and treatment will require significant training and capacity building as well as reorganization of human resources for health. There needs to be greater attention focused on strengthening quality of these services and operational research studies to demonstrate their effectiveness. ART needs to be combined with targeted behaviour-change programmes to develop an integrated response to the HIV epidemic that will support change at the individual and community levels, develop community responses, reduce stigma, and ensure the optimum uptake of biomedical and other services. These basic programme activities need to be underpinned by crucial programme and policy enablers to achieve an optimum comprehensive response.

Strong community engagement is required to address the high level of stigma and discrimination that blocks uptake of available services. Decentralization of HIV services to community level and the integration of these services within the healthcare system must include specific efforts to address a perceived lack of confidentiality that keeps many people from testing until they are extremely sick and can no longer deny their condition.

7. Conclusions

Vietnam is amongst one of the first countries to pilot Treatment 2.0, and thus many policy and programmatic lessons will be learned throughout this process. In the early stages, high level government commitment has generated significant momentum and an appropriate platform to engage multiple stakeholders in redesigning the HIV system to make it sustainable, integrated, decentralized, and accessible to, key populations at higher risk and PLHIV. Leadership from VAAC and support from the WHO and UNAIDS country offices have been critical to this process. While many of the elements of Treatment 2.0 may already be implemented in other countries, they are innovative for Vietnam where late diagnosis and late initiation have severely hindered the effectiveness of the HIV response. Because the epidemic has been concentrated amongst the key populations at higher risk, increasing uptake within these communities and the fight against stigma and discrimination has been critical.

Treatment 2.0 in Vietnam is not only a pilot of simplified and expanded ART delivery and access. As demonstrated in Vietnam, it is an opportunity to engage multiple stakeholders to redesign the HIV system for sustainability. Whether or not this approach will be successful will be determined as implementation progresses and outcomes are evaluated. However, should the pilots be found successful, Vietnam plans to bring Treatment 2.0 to scale and adopt the approach as its HIV national program. The outcomes of this pilot may also become a program model for concentrated epidemics to effectively stem the HIV epidemic and greatly impact the direction of the HIV response. As one of the first countries to advanced pilot Treatment 2.0, valuable lessons have already and will continue to be learned from this experience in Vietnam.

8. Acknowledgements

we would like to acknowledge the great contribution in revising and give inputs to this paper from colleagues from UNAIDS country office in Vietnam: Eamonn Murphy; Christopher Fontaine; Vladanka Andreeva; Nguyen Thi Cam Anh and Nguyen Thi Phuong Mai.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization, Joint United Nations Programe on HIV/AIDS, “The Treatment 2.0 Framework for Action: Catalysing the Next Phase of Treatment, Care and Support,” Geneva, 2011.

- G. Hirnschall and B. Schwartlander, “Treatment 2.0: Catalysing the Next Phase of Scale-Up,” The Lancet, Vol. 378, No. 9787, 2011, pp. 209-211. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60247-X

- B. Schwartlander, J. Stover, T. Hallett, R. Atun, C. Avila, E. Gouws, et al., “Towards an Improved Investment Approach for an Effective Response to HIV/AIDS,” The Lancet, Vol. 377, No. 9782, 2011, pp. 2031-2041. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60702-2

- World Health Organization, et al., “Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011-2015,” Geneva, 2011.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, “UNAIDS 2011-2015 Strategy: Getting to Zero,” Geneva, 2010.

- World Health Organization, “WHO HIV Strategy: Implementing Treatment 2.0, Side Event at the Sixty-Fourth World Health Assembly,” Geneva, 2011.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, “Vietnam Leads on Treatment 2.0— First Pilot Begins in Mid-2011,” Hanoi, 2011.

- Ministry of Health, “20 Years: Responding to HIV/AIDS in Vietnam,” Hanoi, 2010.

- L. Maher, H. Coupland and R. Musson, “Scaling up HIV Treatment, Care and Support for Injecting Drug Users in Vietnam,” International Journal of Drug Policy, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2007, pp. 296-305. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.006

- V. Van Tam, A. Pharris, A. Thorson, T. Alfven and M. Larsson, “It Is Not that I Forget, It’s just that I don’t Want Other People to Know: Barriers to and Strategies for Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV Patients in Northern Vietnam,” AIDS Care, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2011, pp. 139-145. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.507741

- A. D. Ngo, E. A. Ratliff, S. A. McCurdy, M. W. Ross, C. Markham and H. T. Pham, “Health-Seeking Behaviour for Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV Testing among Female Sex Workers in Vietnam,” AIDS Care, Vol. 19, No. 7, 2007, pp. 878-887. doi:10.1080/09540120601163078

- World Health Organization, “Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach,” Geneva, 2010.

- Vietnam Administration of HIV/AIDS Control, Pasteur Institute of Ho Chi Minh City, “Organization WH. Preliminary Results of HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment and Early Warning Indicators of HIV Drug Resistance, Southern Vietnam, 2010,” Ho Chi Minh City, 2011.

- R. Subbaraman, S. K. Chaguturu, K. H. Mayer, T. P. Flanigan and N. Kumarasamy, “Adverse Effects of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy in Developing Countries,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 45, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1093-1101. doi:10.1086/521150

- G. McComsey and J. T. Lonergan, “Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Patient Monitoring and Toxicity Management,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, Vol. 37, Suppl. 1, 2004, pp. S30-S35. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000137004.63376.27

- T. A. Nguyen, H. T. Nguyen, G. T. Le and R. Detels, “Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with HIV Infection among Men Having Sex with Men in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam,” AIDS and Behavior, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2008, pp. 476-482. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9267-y

- V. F. Go, C. Frangakis, L. Van Nam, T. Sripaipan, A. Bergenstrom, F. Li, et al., “Characteristics of High-Risk HIV-Positive IDUs in Vietnam: Implications for Future Interventions,” Substance Use & Misuse, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2011, pp. 381-389. doi:10.3109/10826084.2010.505147

- M. S. Cohen, Y. Q. Chen, M. McCauley, T. Gamble, M. C. Hosseinipour, N. Kumarasamy, et al., “Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 365, No. 6, 2011, pp. 493-505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105243