Advances in Breast Cancer Research

Vol.3 No.2(2014), Article ID:45332,7 pages DOI:10.4236/abcr.2014.32007

Social Support Provided to Women Undergoing Breast Cancer Treatment: A Study Review

Ana Fátima Fernandes*, Amanda Cruz, Camila Moreira, Míria Conceição Santos, Tiago Silva

Department of Nursing, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil

Email: *afcana@ufc.br

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 March 2014; revised 19 April 2014; accepted 25 April 2014

ABSTRACT

Breast cancer treatment may have implications for women’s quality of life and social support, which refers to mechanisms through which interpersonal relationships protect people from the detrimental effects of stress. This study’s objective was to analyze evidence available in the literature concerning social support provided to women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. The Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS), PubMed, Web of Science, Psycinfo and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases were used to select the studies. The papers were pre-selected after reading titles and abstracts and ten papers were ultimately selected after fully reading the texts. The studies were summarized, while their methodological designs and results were noted. The analysis of the studies shows that social support can be provided to women with breast cancer, such as emotional, instrumental and informational support. It is apparent that emotional and instrumental support is provided in the first phase of the treatment. The main sources of support include the spouses, family members and friends. Spouses provide emotional support, but mainly provide instrumental support, while family members and friends are the most important source of emotional support. The conclusion is that emotional support greatly contributes to the health-disease continuum, favoring treatment adherence and creating opportunities for women to express their feelings, positively influencing the treatment.

Keywords:Breast Cancer, Oncological Treatment, Social Support

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer affecting women around the world. There are approximately 1000 new cases every year and it accounts for a significant number of deaths among adult women, thus is a severe public health problem [1] .

The most common therapeutic modality for this type of cancer is mastectomy with extraction of the compromised breast. In some women, only parts of the breast are removed: quadrantectomy (removal of one quarter of the breast) and lumpectomy (removal of only the tumor and a small surrounding region), producing good results in terms of survival and a better aesthetic effect, since the breast is largely retained. In more advanced cases, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the indicated treatments. The choice for the most appropriate therapeutic method depends on various factors, such as age, the site of the tumor, financial availability, analysis of mammography, and the manner in which the patient deals with the affected breast [2] .

In addition to treatment-related implications, one should also consider the deleterious effects of the disease (fear of death, of rejection, of being stigmatized, of mutilation, relapse, the effects of the chemotherapy, uncertainty concerning the future and others), which are representations that concern health professionals involved with the quality of life of these patients [2] .

Patients with breast cancer have many needs, including a need for strategies to cope with associated stress, both during and after treatment. The creation and/or utilization of social support has been a strategy to reduce the deleterious effect of stressful events related to the treatment of breast cancer [3] . Social support or social networks are structures consisting of family, friends, neighbors, and other individuals who inter-relate and provide reciprocal support. It refers to mechanisms through which interpersonal relationships protect people from the detrimental effects of stress. Social support is a key for any individual’s emotional safety because every individual has a need to feel part of a family or group of friends [4] .

Given the previous discussion, we note that the breast cancer treatment leads to many situations that may threaten the psychosocial integrity of those affected by the disease. The social behavior of women is affected, leading to restrictions on their social lives and changes in daily life activities, facts that may contribute to depressive behavior and social isolation.

This study’s objective was to analyze evidence available in the literature regarding the social support provided to women with breast cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to accomplish this study’s objective, we conducted an integrative literature review, which is a technique that compiles and synthesizes scientific information by analyzing the results reported by studies. This review followed five distinct stages to meet the same methodological rigor of any conventional study .

The initial phase comprised the identification of the problem under study, after which a guiding question was asked and inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Having well-delineated criteria facilitates the other stages of the review, especially the differentiation of information concerning data collection . Therefore, the following guiding question was chosen: “What is the scientific knowledge available regarding social support provided to women with breast cancer undergoing treatment?

The databases chosen for a comprehensive search and selection of studies included: PubMed, digital files created by the National Library of Medicine (USA) in the biosciences field; Web of Science, encompassing a set of databases (Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Current Chemical Reactions and Index Chemicus) compiled by the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI); CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), which encompasses the main scientific studies in the nursing field; PsycINFO, a reference source for the psychology, behavioral and education sciences; and LILACS, which gathers scientific studies in the health field in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In this context, inclusion criteria were primary studies published in English, Spanish or Portuguese addressing some type of social support provided to women with breast cancer; studies in which social support was the main focus and object of study; and studies in which women with breast cancer were undergoing treatment or up to 24 months after the beginning of treatment.

Exclusion criteria were studies the subjects of which were younger than 18 years old or elderly individuals because social support, in these cases, would include other issues not strictly related to chemotherapy. Studies addressing other types of cancer were also excluded.

The search terms included social support, family, and breast neoplasms, which were used in different combinations to increase the number of potential references.

First, the titles of papers were analyzed to verify their adequacy to answer the guiding question. The papers were then further checked by reading the abstracts. The full texts of those studies that were preselected were then read to make sure they met the inclusion criteria previously established.

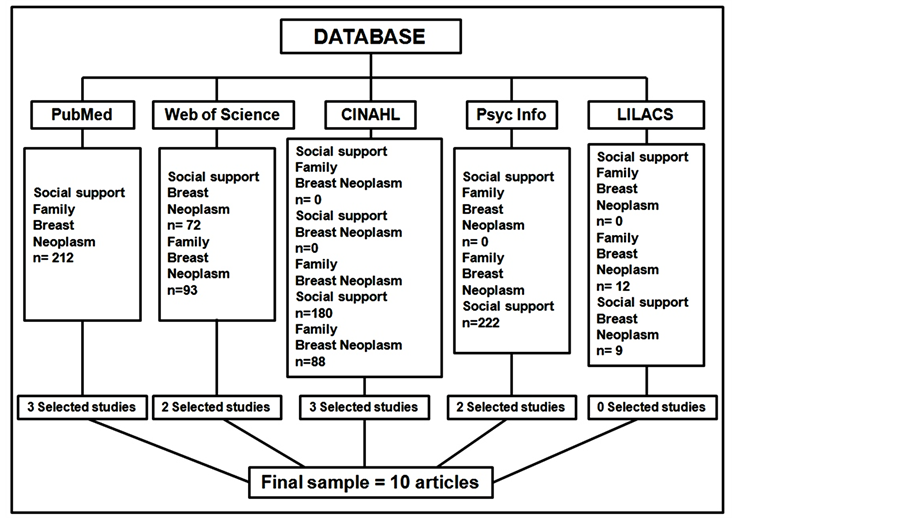

Following the established strategies, the final sample was composed of ten papers, three of which were found in the PubMed database, two in the Web of Science, three in CINAHL, and another two in PsycInfo (Figure 1).

2.1. Categorization of the Studies

An adapted instrument was used to collect and summarize data concerning the selected studies, which included information concerning the identification of studies, introduction and aims, methodology, description of results, conclusion, and level of evidence . The instrument was subjected to a pretest to establish its goodness of fit with the aims of the study and to ensure rigor. Two articles meeting the inclusion criteria were used to identify the most appropriate manner to use the instrument and to verify the validity of its content.

2.2. Analysis of Studies

Following categorization, the relevant aspects concerning the identification of the data from the studies and their content concerning introduction, methods, results, and conclusions were analyzed. Synthesis of information is presented in a descriptive manner and tables are used to summarize data, as well as the main findings of this study.

2.3. Interpretation of Results

Data are discussed and compared to theoretical knowledge addressing the implications resulting from this study.

2.4. Presentation of the Integrative Review

The review presents relevant and detailed information on procedures and findings and contributes to a critical analysis and a more thorough understanding of the subject under study.

Figure 1. References resulting from the combination of the search terms using the PUBMED, WEB OF SCIENCE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO and LILACS databases.

3. Results

Ten articles were selected for full-text analysis. Their data were extracted and analyzed for categorization based on the data collection instrument that was used in this review. Each paper and corresponding data collection instrument was given an identification number to generate an organized information structure. Table 1 lists details of the studies included in this review.

All ten papers included in the sample were published in English. Six of them originated in the United States [7] -[10] [14] [15] ; one paper was published in Canada [12] , another one in England [13] , one in Holland [11] , and one paper was published in Israel [16] .

An analysis of the database showed that three papers were found in PubMed [7] -[9] , another two in Web of Sciences [10] [11] , three in CINALH [12] -[14] , and two in PsycInfo [15] [16] . In regard to the studies’ methodological design, one consisted of a randomized clinical trial [13] and nine were descriptive studies [7] -[12] [14] -[16] .

We verified that researchers from the nursing field wrote four of the papers and only one study was conducted in partnership with other professionals, such as physicians. In regard to the year of publication, the papers were published between 1989 and 2011. The United States accounted for the highest number of publications and, even though some studies had other countries of origin, English predominated. In regard to characteristics concerning the types of studies, of the ten studies included in this review, one used a quantitative methodological approach, a randomized clinical trial with evidence level II [13] . The other nine studies used a qualitative methodological approach and were all descriptive studies with level of evidence IV [7] -[12] [14] -[16] .

4. Discussion

The results are consistent with existing literature addressing the need for support of women undergoing breast cancer treatment. Women undergoing treatment require greater support and are, in fact, more likely to receive it. This review shows that individuals undergoing treatment experience more problems concerning psychological, social, sexual and emotional issues and usually obtain the support and help necessary to overcome these side effects.

Additionally, emotional support influences the decisions women make to adhere to treatment, which also agrees with one study reporting that emotional support can influence and/or facilitate decisions concerning treatment adherence and post-treatment care, contributing to health promotion [17] .

Studies suggest there is a source of discomfort within the patient/spouse dyad due to changes in roles imposed by the disease and, as a result, the support provided is no longer a protective factor against distress [18] . No studies were found addressing a lack of balance between couples facing breast cancer. Even though patients facing such an important stressor related to health do benefit from support provided by the spouses, these benefits are also extended to the spouses themselves. Women with breast cancer may benefit their spouses with intimacy and

Table 1. Details of the studies included in this review.

provide support. The daily relationship between couples may benefit the patient’s wellbeing and provide a sense of connection through receiving and providing daily support to each other [7] .

Women with breast cancer perceive that less social support is provided over time. Some report that a lack of balance is perceived when support requested is not provided or when the support provided was not the support sought. One should take into account that perception of social support may be influenced by personality factors along with one’s psychological state [11] .

One study reports that women receive high levels of support but that it decreases over time [17] . This perception of decreased support may be related to lower availability of support or a lower quality of support, when available. The author speculates there are three explanations for these results: first, ongoing support affects the one providing it and may result in exhaustion; second, women acquire skills to deal with the disease over time, thereby the need for support provided by family, friends and others may decrease; and third, this perception of reduced support may be related to a certain incompatibility between the patient’s real needs and the support provided.

Patients experiencing greater psychological distress may view the supply of support as a sign of personal incompetence or loss or need for a previous level of independence. This may occur when the social support provided does not agree with one’s needs or desires. Likewise, it may occur when there is a lack of clear communication between suppliers and recipients of support, while such a lack of communication results in members of the social network being ill-informed regarding the patient’s situation. When support emphasizes the vulnerability of the recipients of care, their dependency or inequality, or when the recipient does not feel able to reciprocate, patients may feel more distress over support. Reciprocity attenuates the relationship between support supply and self-esteem or between support and distress among Japanese women. In this women’s cultural norm, giving back kindness received is the key to avoiding a sense of guilt and shame in their social interactions. If they cannot reciprocate, the support provided may become a negative and interfere in their self-esteem [17] .

This review’s findings indicate that distress and depression related to treatment side effects, together with social support, affect a patient’s psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and are consistent with the literature. This situation occurs in a greater proportion of patients in chemotherapy in which women under treatment experience significantly greater distress and experience problems regarding psychosocial adjustment. High levels of anxiety and distress and low affability tend to reduce as one’s perception of social support due to psychosocial changes are experienced by women undergoing breast cancer treatment.

Compared to older women, younger women with breast cancer are more likely to experience adverse psychosocial outcomes. This study found an inverse relationship between age and discomfort, indicating that older participants experience less distress [19] .

Single women report not being affected by the lack of a husband, though they were surrounded by family members and friends who provided support. Women with partners tend to have better mental health compared to single women. Among various types of instrumental and emotional support provided by other significant people, only emotional support provided by spouses, such as listening to concerns and instrumental support when helping at home, are predictors of less depressive symptoms [20] .

Different types of social support are tightly connected with quality of life. Attitudes such as involving the partner and the family in treatment so they become aware of the problems women with breast cancer face, educating women concerning the importance of social support, teaching them to ask for help and discuss their needs, are exercises of social support. During treatment, women often suffer from distress and social support may be provided when these actions are implemented, leading them to experience better quality of life.

Other types of support that influence quality of life include: support groups and expressive writing. Given the stress accruing from experiencing cancer, a support group is essential to maintaining patients’ hope and wellbeing. Women participating in support groups acquire more acknowledgment, awareness and management practices to deal with their treatment.

The direct effect of religious support was not found in the analyzed studies. This is inconsistent with the results of some previous studies specifically addressing positive effects of religion and, at the same time, is consistent with other studies suggesting that religion does not have a significant impact on the survival of breast cancer patients [21] . These relationships may be discussed in light of recent literature. Seeking support in religion through ritual practices or by invoking God in a situation of disease is an easily accessible strategy [22] . Religiosity may be both a negative and positive coping strategy. Individuals dealing with stress may become dependent on religious resources or question their own religion [23] . Additionally, people facing great hardships may seek comfort in religion.

Support during treatment comprises a complex balance among family, social well-being, psychosocial adjustment and quality of life. Finally, the success of treatment is not determined only by the cure of the disease, but mainly by how the patient perceives quality of life, one aspect of which is social support.

5. Conclusions

Women with breast cancer undergoing treatment have a real need for support. Providing social support is a part of integral care provided by nurses. Emotional support was the most beneficial in the adjustment of women with breast cancer, generating opportunities for them to express feelings and favoring treatment adherence. The main sources are the spouse, family and friends, while the spouse is the most important emotional support and the main source of instrumental support.

Over time, women may perceive a decrease in emotional support, which may be related to personality factors or to one’s psychological state. In some cases, women may even interpret the reception of support as personal incompetence.

Distress and depression accruing from the side effects of treatment together with perceived support may affect the psychosocial adjustment of women with breast cancer. Religiosity does not directly influence quality of life, though social support provided by support groups and ways to express feelings such as writing, may influence quality of life.

6. Relevance to Clinical Practice

Health professionals should assess women’s social networks, observing sources of support, the type of support provided and whether the needs of patients are being met by the support provided. Information needs of women should be assessed and acknowledged by nurses and other health workers, highlighting not only the importance of emotional and instrumental support but also of informational support. Support may be provided during treatment in environments where women have the opportunity to express their needs, feelings, and share their experiences with the disease.

Even though the experience of the women addressed in these studies probably does not represent the experience of the entire population of women with breast cancer, the knowledge acquired from these papers can be used by professionals around the world to explore the needs of women undergoing treatment in their own configurations for support, considering the context of practice of each professional, their competencies and skills and the preferences of women under their care.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Urban, C.A., Lima, R.S., Schunemann Junior, E., Hakimneto, C.A., Yamada, A. and Torres, L.F.B. (2001)Linfonodo Sentinela: Um Novo Conceito no Tratamento Cirúrgico do Câncer de Mama. Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões, 28,1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-69912001000300011

- Moura, F.M.J.S.P., Silva, M.G., Oliveira, S.C. and Moura, L.J.S.P. (2010) Os Sentimentos das Mulheres Pós-Mastectomizadas.Revista Escola de Enfermagem Anna Nery, 14, 477-484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1414-81452010000300007

- Moreira, C.B., Fernandes, A.F.C., Gomes, A.M.F., Silva, A.M.L. and Santos, M.C.L. (2013) Educational Strategy Experimented with Mastectomized Women: Experience Report. Journal of Nursing UFPE on Line, 7, 302-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.5205/reuol.3049-24704-1-LE.0701201339

- Tilden, V.P. and Weinert, C. (1987) Social Support and the Chronically Ill Individual. Nursing Clinics of North America, 22, 613-620.

- Whittemore, R. and Knalf, K. (2005) The Integrative Review: Update Methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546-553. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Ursi, E.S. and Gavão, C.M. (2006). Prevenção de Lesões de Pele no Perioperatório: Revisão Integrativa da Literatura. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 14, 124-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692006000100017

- Belcher, A.J., Laurenceau, J.P., Graber, E.C., Cohen, L.H. and Dasch, K.B. (2011) Daily Support in Couples Coping with Early Stage Breast Cancer: Maintaining Intimacy during Adversity. Health Psychology, 30, 665-673. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024705

- Budin, W.C. (1998) Psychosocial Adjustment to Breast Cancer in Unmarried Women. Research in Nursing & Health, 21, 155-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199804)21:2<155::AID-NUR6>3.0.CO;2-I

- Walsh, J.M. (2005) Social Support as a Mediator between Symptom Distress and Quality of Life in Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34, 482-493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884217505278310

- Lepore, S.J., Glaser, D.B. and Roberts, K.J. (2008) On the Positive Relation between Received Social Support and Negative Affect: A Test of Triage and Self-Esteem Threat Models in Women with Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 1210-1215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1347

- Oudsten, B.L.D., Heck, G.L.V., Van der Steeg, A.F.W., Roukema, J.A. and Vries, J.D. (2009) Personality Predicts Perceived Availability of Social Support and Satisfaction with Social Support in Women with Early Stage Breast Cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18, 499-508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0714-3

- Zemore, R. and Shepel, L.F. (1989) Effects of Breast Cancer and Mastectomy on Emotional Support and Adjustment. Social Science & Medicine, 28, 19-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90302-X

- Gellaitry, G., Peters, K., Bloomfield, D. and Horne, R. (2009) Narrowing the Gap: The Effects of an Expressive Writing Intervention on Perceptions of Actual and Ideal Emotional Support in Women Who Have Completed Treatment for Early Stage Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 77-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1532

- Makabe, R. and Hull, M.M. (2000) Components of Social Support among Japanese Women with Breast Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 27, 1381-1390.

- Alferi, S.M., Carver, C.S., Antoni, M.H., Weiss, S. and Durán, R.E. (2001) An Exploratory Study of Social Support, Distress, and Life Disruption among Low-Income Hispanic Women under Treatment for Early Stage Breast Cancer. Health Psychology, 20, 41-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.20.1.41

- Feigin, R., Greenberg, A., Ras, H., Hardan, Y., Rizel, S., Efraim, T.B. and Stemmer, S.M. (2000) The Psychosocial Experience of Women Treated for Breast Cancer by High-Dose Chemotherapy Supported by Autologous Stem Cell Transplant: A Qualitative Analysis of Support Groups. Psycho-Oncology, 9, 57-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<57::AID-PON434>3.0.CO;2-C

- Arora, N.K., Rutten, L.J.F., Gustafson, D.H., Moser, R. and Hawkins, R.P. (2007) Perceived Helpfulness and Impact of Social Support Provided by Family, Friends, and Health Care Providers to Women Newly Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 474-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1084

- Soler-Vila, H., Kasl, S.V. and Jones, B.A. (2003) Prognostic Significance of Psychosocial Factors in African-American and White Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer, 98, 1299-1308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11670

- Nausheen, B. and Kamal, A. (2007) Familial Social Support and Depression in Breast Cancer: An Exploratory Study on a Pakistani Sample. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 859-862. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1136

- Maly, R.C., Umezawa, Y., Leak, B. and Silliman, R.A. (2005) Mental Health Outcomes in Older Women with Breast Cancer: Impact of Perceived Family Support and Adjustment. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 535-545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.869

- Tominaga, K., Andow, J., Koyama, Y., Numao, S., Kurokawa, E., Ojima, M. and Nagai, M. (1998) Family Envairoment, Hobbies and Habits as Psychosocial Predictors of Survival for Surgically Treated Patients with Breast Cancer. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 36-41.

- Fernandes, A.F.C., Bonfim, I.M., Araújo, I.M.A., Silva, R.M., Barbosa, I.C.F.J. and Santos, M.C.L. (2012) Significado do cuidado familiar à mulher mastectomizada. Escola Anna Nery, 16, 27-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1414-81452012000100004

NOTES

*Corresponding author.