Open Journal of Orthopedics

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:43681,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ojo.2014.43011

Open Fracture Tibia Treated by Unreamed Interlocking Nail. Long Experience in El-Bakry General Hospital

Mohamed A. Abdelaal1, Saied Kareem2

1Consultant of Orthopedic Surgery, El-Bakry General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Cairo, Egypt

2Lecturer of Orthopedic Surgery, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Email: btmnail2010@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 1 January 2014; revised 5 February 2014; accepted 14 February 2014

ABSTRACT

Background: Internal splintage of open tibial fractures had gained acceptance as a preferred method of early stabilization of such injuries. Patients and Methods: Fifty-five patients had been operated upon. They were followed from July 2008 to March 2013 (56 months) with an average time of 39 months. The final results had been evaluated through a scheme including 7 parameters: pain, union, malunion, infection, range motions of nearby joints, implant and technical failure and activity and returning to the same work. Results: According to previous parameters, union was achieved in 52 cases (94.5%) at an average time of 20 weeks (16 - 52 weeks) with 5.5% incidence of nonunion. Excellent and good ranges of knee and ankle motions were achieved at final follow-up visit in 49 cases (89.09%). The incidence of complication was acceptable mainly malunion 7.3%, deep infection 12.7%, implant and technical failure 9.1% full activity and returning to the same work achieved in 89.1%. The overall net results of our series are as follows: excellent—19 cases (34.5%), good—27 cases (49.1%), fair—6 cases (10.9%) and poor—3 cases (5.5%). Conclusion: Utilizing unreamed interlocking nail for open tibial fractures is a good method of treatment particularly those of grade (II), and (IIIA).

Keywords:Fracture Tibia; Unreamed; Interlocking Nail

1. Introduction

Open tibial fractures are more frequent than any other long bone fractures. Because of high prevalence of complications associated with these fractures, the optimum method of treatment remains a subject of controversy [1] . The prognosis of these fractures is determined primarily by the amount of devitalized soft tissues caused by the injury and by the level and type of bacterial contamination. Also, the extent of soft tissue damage is determined by energy absorbed by the affected area at the time of injury. The goals of treating these fractures are: preventing infection, restoring soft tissue vitality, achieving bony union and instituting early joint motion and muscle rehabilitation. Various techniques had been utilized including: plaster cast immobilization [2] , functional cast brace utilized by Sarmiento [3] , external fixators either uniplanar or multiplanar fixators [4] [5] . Also, Circular fixators utilized for fractures of the periarticuler region, either proximal or distal, were proved to be effective to provide good stability [6] .

Internal fixation utilizing plates and screws provide rigid fixation for unstable fractures and so, reducing the problem of non-union [6] [7] . However, stripping of soft tissues to apply the plate had increased the rate of infection [8] .

Intramedullary fixation using Lottes and Ender nails [9] had been used successfully though they were not preferred in comminuted fractures as they might lead to shortening or redisplacement [10] [11] .

Interlocking nailing without reaming resulted in lower incidence of malunion, non-union and rate of infection and allowed early patient rehabilitation especially for unstable fractures [12] .

We aim in our study to present our experience on dealing with open tibial fractures treated by unreamed interlocking tibial nail. Also, assessing the effectiveness both clinically and radiologically utilized this procedure.

2. Patients and Methods

Fifty-Five patients with open tibial fractures were treated and followed from July 2008 to March 2013 (56 months). In our institute (El-Bakry General Hospital). There were 44 males (80%) and 11 females (20%). The age ranged between 25 to 65 years with mean age 33.2 years. Right side affected in 31 cases (56.4%) and left side in 24 cases (43.6%). The fractures were simple in 34 cases (61.8%) and comminuted in 21 cases (38.2%). The upper third affected in 11 cases (20%), middle third in 35 cases (63.6%) and lower third in 9 cases (16.4%). The causative trauma was motor car accident in 25cases (45.5%), fall from height in 19 cases (34.5%), direct trauma with heavy object in 9 cases (16.4%) and 2 cases (3.6%) caused by gunshot injury. Eight cases (14.5%) had associated muscle-skeletal injuries (5 with fracture femur; one case with stable pelvic fracture and two cases with colles. Regarding wound evaluation we utilized Gustilo-Anderson classification [13] . There were 17 cases Grade (II), 14 cases Grade (IIIA) and 7 cases Grade (IIIB) (Tables 1 and 2).

Resuscitation of the patient, thorough irrigation utilizing 3 - 7 liters saline solution. All contaminated, devitalized soft tissues and bone fragments were excised and gunshots extracted. Broad spectrum antibiotic was given (3rd generation cephalosporin, 1 gm. IV/12 hours).

Nailing was done at time of debridement in 32 cases, less than 12 hours in12 cases, delayed for 72 hours due to other medical problems in 6 cases and delayed between 7 - 15 days with average 6 days in 5 cases Table 3.

Table 1. Distribution of patients.

Table 2. Classification of fractures.

Table 3. Timing of nailing.

Surgical Technique

Length and width of nail was provisionally determined preoperatively. The nail of proper width and length was assembled to the Distal Locking Target Device to adjust distal locking screws position. Through longitudinal paramedian incision about 4 cm parallel to patellar tendon, the entry point of nail detected and opened using a curved Awl. Guide-wire passed through medullary canal down to level of the fracture site and under direct vision (in cases of Grade (II) and Grade (III) fractures) while utilizing image intensifier (in cases of Grade (I) fractures). The guide wire was directed toward the distal fragment and its position checked again radiographicaly for further confirmation. The chosen nail attached to insertion jig and driven over the guide wire through the medullary canal. Distal locking Target Device assembled to the jig and distal locking screws inserted first then the proximal ones.

The closure of the wound was done by primary closure in 32 cases; it was done by secondary closure with a lateral skin release in 15 cases; and it was done by secondary closure with a split thickness skin grafting in 5 cases and with secondary closure with muscle pedicle rotation flaps with split thickness skin grafting in 3 cases. There was a marginal flap necrosis in one case, but all of them were managed by debridement and re-suturing.

Wounds dressed every other day and weight bearing was encouraged for those who had no other associated injuries prohibiting walking (5 cases) and as soon as patient tolerability to pain permitted.

Dynamization by removal of either proximal or distal locking screws done for 38 cases (69.1%), fibular osteotomy in addition to dynamization done in two cases (3.6%), autogenous bone grafting done for 4 cases (7.3%), bone marrow injection for 3 cases (5.5%) and in two cases (3.6%) both dynamization and bone grafting had been done (Figures 1 and 2).

3. Results

The patients of this series were followed for 18 - 56 months with average 39 months. They were evaluated both clinically and radiologically. Evaluation based on a scheme including 7 items:

1) Pain; 2) Union and Non-union; 3) Malunion; 4) Infection; 5) Range of nearby joints motions; 6) Implant and technical failure; 7) Full activity and return to same work.

According to this scheme, results were classified into 4 categories: Excellent, Good, Fair and poor. The criteria of each item are explained in Table 4.

Patient rated (excellent) if all his parameters were rated excellent but if one parameter rated (good), his rate would decrease to good instead. The overall results of our series are as follows:

Excellent: 19 case (34.5%).

Good: 27 cases (49.1%).

Fair: 6 cases (10.9%).

Poor: 3 cases (5.5%).

3.1. Pain

Nineteen cases (34.5%) had no pain (Excellent), 28 cases (50.9%) had pain with strenuous activity (Good), 6 cases (10.9%) had pain elicited with normal activities (Fair) and in 2 cases (3.7%) pain developed even at rest (Table 5).

3.2. Union

Union evaluated clinically by capability of patient to bear weight fully on affected side without pain, absence of

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c) (d)

(d) (e)

(e)

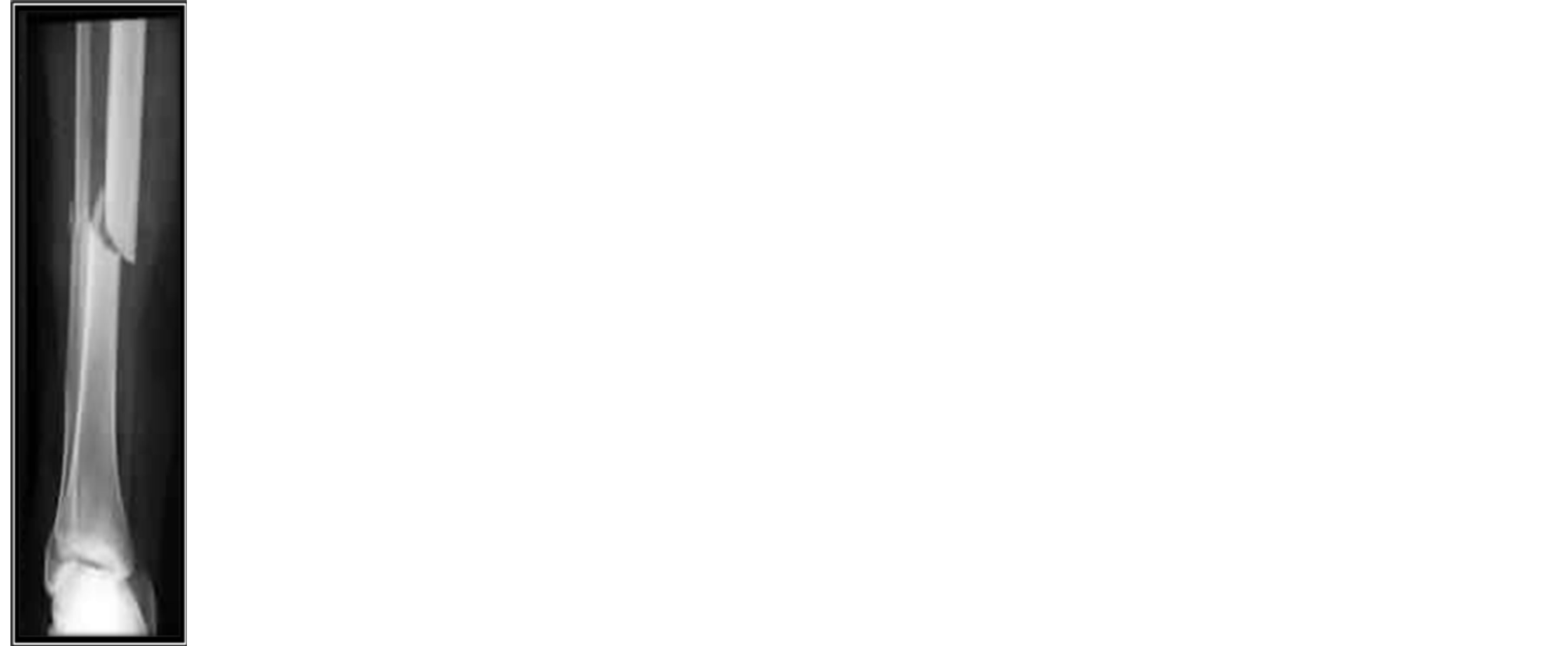

Figure 1. (a) Open fracture B.B. Rt. Leg Grade (II). (b) X-ray showing short oblique diaphyseal fracture. (c) Intramedullary fixation with Interlocking Tibial Nail. (d) four months post-operative showing complete union of fracture. (e) Full knee flexion with proper squatting of the patient.

Table 4. Full activity & return to same work.

(a)

(a) (b)

(b) (c)

(c) (d)

(d) (e)

(e) (f)

(f)

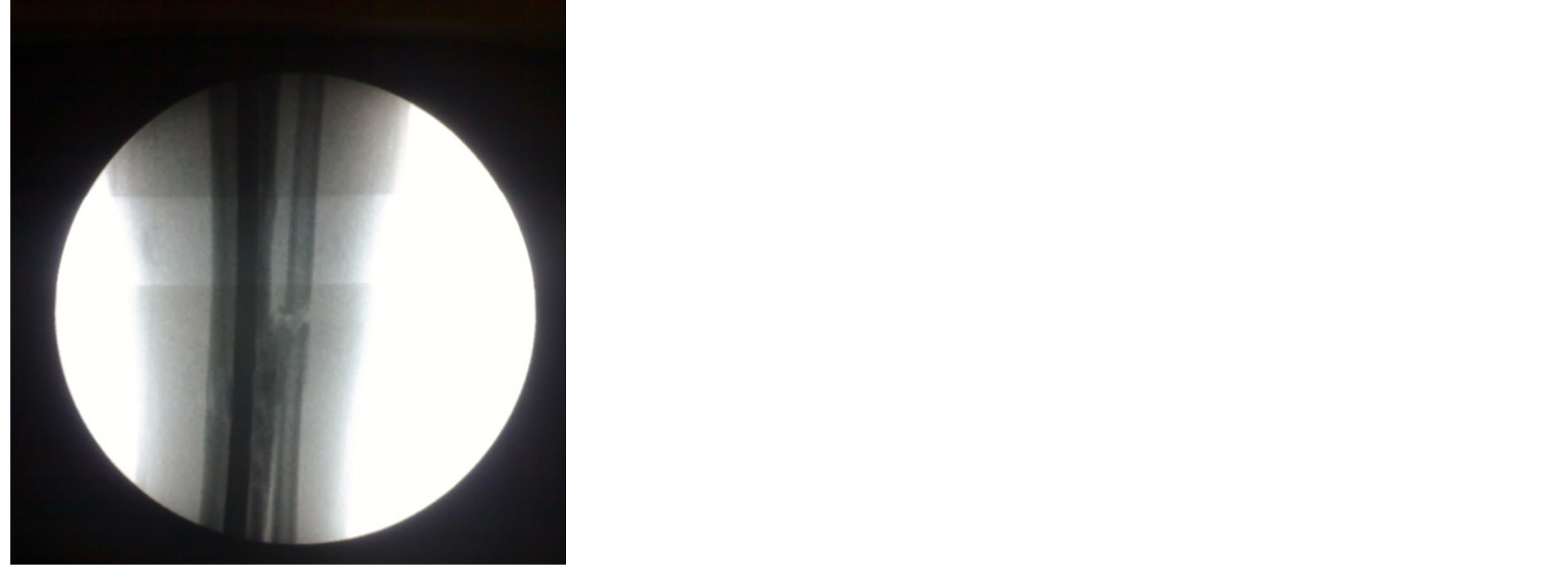

Figure 2. (a) Open fracture both bones left leg Grade ( IIIA). (b) X-ray showing diaphyseal fracture of both bones leg. (c) & (d) Intra-operative radiography during Nail applying. (e) Immediate post-operative with good reduction & proper alignment. (f) 3 months post-op. following dynamization.

Table 5. Distribution of pain.

movement at fracture site and radiologically by presence of bridging callus and-or-disappearance of fracture line on two radiographic views.

Fifty-two cases (94.5%) were fully united and the time of union ranged between 4 - 17 months with average 9 months. Nineteen cases (34.5%) united before 6 months and rated (Excellent), 28 cases (50.9%) united between 6 months and one year and rated (good), 5 cases (9.1%) united after one year and rated (Fair); while 3 cases (5.5%) failed to unite and rated (Poor) Table 6.

3.3. Malunion

Malunion was defined as angular deformity (either varus or valgus) of more than 5˚, anteroposterior angulations more than 10˚ or shortening more than one centimeter [14] .

Cases with neither malunion nor shortening rated (Excellent) and 36 cases (65.5%) of this category. Cases with less than 15˚ angular deformity or less than 3 centimeter shortening were considered (Good) and 16 cases (29.1%) were of this category. Cases with less than 20˚ angular deformity or less than 4 cm shortening considered (Fair). We had 2 cases (3.6%) with varus angulations (15˚ - 19˚). Cases with more than 20˚ angular deformity or more than 4 centimeter shortening rated (Poor) and 2 cases (3.6%) related to this category with valgus angulations of 25˚ and 30˚ (Table 7).

3.4. Infection

Cases with neither superficial nor deep infection were rated (Excellent). There were 21 cases (38.2%) related to this category. Patients with superficial infections were rated (Good) and this occurred in 27 cases (49.1%). Patients with properly controlled deep infection were rated (Fair) and there were 5 cases (9.1%) of this category. Cases with uncontrolled deep infection {2 cases (3.6%)} were rated (Poor) (Table 8).

3.5. Range of Motions

Range of motion of Knee and ankle joints were evaluated and compared with contralateral side. There were 21 cases (38.2%) with full range of motions of both knee and ankle joints and rated (Excellent), 23 cases (41.8%) lost less than 30˚ degrees of full range and rated (Good), 9 cases (16.4%) showed loss from 30˚ - 60˚ of full range and rated (fair) and 2 cases (3.6%) lost more than 60˚ of full range and rated (Poor) (Table 9).

3.6. Implant and Technical Failure

Patients with neither implant nor technical failure were rated (Excellent) and 50 cases (90.9%) related to this category. Patients with technical failure were rated (Good) and 3 cases (5.5%) of this category where one of dis

Table 6. Distribution of union rate.

Table 7. Distribution of malunion.

Table 8. Distribution of infection rate.

tal locking screws was outside its corresponding hole in the nail. Those with implant failure were considered (Fair) and there was one case where one locking screw broken. Patients with both technical and implant failure were rated (Poor) and there was one case where one locking screw broken and the nail was slightly low distally (Table 10).

3.7. Full Activity and Return to Same Work

Full activity of the patient and return to previous work was considered as (Excellent) result. It was achieved in 37 cases (67.3%). Return to same work with invalidity less than 20% was considered (Good) and was achieved in 12 cases (21.8%). Return to same work with more than 20% invalidity was rated (Fair) and 4 cases (7.3%) related to this category. In two cases (3.6%) patients were unable to return back to previous work and rated (Poor) (Table 11).

Distribution of overall results shown in Table 12.

4. Discussion

Open tibial fractures represent a challenge to most of orthopedic surgeons. They are considered an indication for operative fixation (Variable techniques had been used to treat these fractures:

Plaster cast described by many authors but its shortcomings of infection, malunion and shortening hinder its usage [2] .

External fixation is universally accepted as a technique of choice particularly for those grade (II) and grade (III) [15] . However; pin track infection, malunion and surgical demanding as a technique are major shortcomings [16] .

Table 9. Distribution of range of motions.

Table 10. Implant and technical failure.

Table 11. Full activity and return to same work.

Table 12. Summary of overall results.

Unreamed interlocking tibial nail is of utmost importance on treating open fractures in which Periosteal blood supply is already compromised by the original trauma. Also, allowing Control of rotation, axial alignment and length [17] [18] .

We compared our results with those of other series utilizing same technique of fixation [17] [19] [20] [21] . The prolonged period of follow-up which was not issued by many studies gave us a chance to predict even minor complications and these shortcomings that require very long period of follow-up.

Our series has 47 patients with no pain or occurring with vigorous activity. This may be explained by the fact that early rehabilitation of the patient would improve the psychological status of patient. Also, lower incidence of infection with its effect on development of cicatrization may lessen the incidence of pain [22] .

Delayed union reported in 5 cases (9.1%). Four cases were grade (III) and one case related to grade (II). These results emphasized the fact that the more the soft tissue injury, the slower the rate of bone healing. It was counteracted by bone grafting in 4 cases, bone marrow injection in 3 cases, fibular osteotomy in addition to dynamization of the fracture in 2 cases and in two cases dynamization in addition to bone grafting had been done. All cases of delayed union showed complete union by 12 months.

Non-union rate in our series is 5.5% (3 cases). All of them related to grade (III). These results are more or less coincident with the results of other studies [17] [19] [20] [21] . Also; the results emphasizes that the more devitalization of soft tissues; the higher the incidence of non-union [23] .

Malunion reported in 4 cases (7.3%). In 2 cases the distal locking screws were early removed (dynamization of the fracture) to counteract the development of delayed union. The other 2 cases showed sever infection and at the same time the patients bear weight early without casting protection as recommended by many authors [24] .

Seven cases of deep infection (12.7%) had been reported which is comparably high. This might be attributed to the increased number of grade (III) cases (21cases) with marked soft tissue devitalization. Also, delay interference in some cases might be a predisposing factor [25] . There was no deep infection in grade (I) cases and this may be attributed to preservation of soft tissue envelop around the fracture ends.

Regarding range of motions of knee and ankle joints as a key for evaluating efficiency of the technique. There were 21 cases (38.2%) regained full range of motions for both knee and ankle joints and this attributed to the early rehabilitation of the patient’s joints and the proper control of infection preventing its spread to nearby joints. In 11 cases (20%) the range of motions of knee joint was markedly affected. All of them related to grade (III) which explains that the more the soft tissues damage the more the delay of patient recovery which in turn affecting the nearby joints range of motions [26] .

There was high incidence of cases with neither implant nor technical failure accounting for 50 cases (90.9%). This may be due to perfection and mastering the technical issue. One more advantage of the technique is the use of Distal Targeting Device for applying the distal locking screws. This device minimizes the operative time and lessens the hazards proposed by exposure to radiation during nail application [27] .

5. Conclusion

Unreamed tibial nailing is considered a good method for management of open fracture tibia. The results of our series emphasize that strict adherence to technical prerequisites, proper wound management and frequent use of bone grafting or bone marrow injection may consider that this technique is safe, efficacious and could be the treatment of choice for grade (I) and grade (II) open tibial fractures.

References

- Nicoll, E.A. (1964) Fractures of the Tibial Shaft, a Survey of 705 Cases. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery (Br), 46, 373- 387.

- Sarmiento, A. and Latta, L.L. (1999) Functional Fracture Bracing. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 7, 66-75.

- Edwards, C.C. (1983) Staged Reconstruction of Complex Open Tibial Fractures Using Hoffmann External Fixation. Clinical Decisions and Dilemmas. Clinical Orthopaedics, 178, 130-161.

- Watson, J.T., Ripple, S. and Hoshaw, S.J. (2002) Hybrid External Fixation for Tibial Plateau Fractures: Clinical and Biomechanical Correlation. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 33, 199-209.

- Patzakis, M.J. and Wilkins, J. (1989) Factors Influencing Rate in Open Fracture Wounds. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 243, 36-40.

- Chapman, M.W. (1980) The Use of Immediate Internal Fixation in Open Fractures. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 11, 579-591.

- Farouk, O., Krettek, C. and Miclau, T. (1997) Minimally Invasive Plate Osteosynthesis and Vascularity: Preliminary Results of a Cadaver Injection Study. Injury, 28, 7-12.

- Lottes, J.O. (1974) Medullary Nailing of the Tibia with the Triflange Nail. Clinical Orthopaedics, 105, 253-266.

- Chapman, M.W. (1986) The Role of Intramedullary Fixation in Open Fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics, 212, 26-34.

- Bhandari, M., Guyatt, G. and Tornetta, P. (2008) Randomized Trial of Reamed and Undreamed Intramedullary Nailing of Tibial Shaft Fractures. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery (Am), 90, 2567-2578.

- Bonatus, L.B., Kassman, S., Stegemann, P. and France, J. (1994) Prospective Study of Union Rate of Open Tibial Fractures Treated with Locked Unreamed Intramedullary Nails. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 8, 45-49.

- Gustilo, R.B. and Anderson, J.T. (1976) Prevention of Infection in the Treatment of 1025 Open Fractures of Long Bones: Retrospective and Prospective Analyses. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery (Am), 58, 453-458.

- Andrew, H., Schmeling, G.J. and Finkemeied, M.B. (2003) Treatment of Tibial Fractures. Instructional Course Lecture. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery, 85-A, 352-368.

- Kyung, C., June, K., Deuk, S. and Jun, Y. (2007) Tibial Unreamed Intramedullary Nailing Using Schanz Screws in Displaced Diaphyseal Segmental Fractures. Orthopedics, 30, 11.

- Wani, I.H. and Salaria, A. (2012) Unreamed Solid Locked Nailing in the Treatment of Compound Diaphyseal Fractures of Tibia. Orthopedics, 3, 5.

- Ziran, B.H., Darwish, M. and Klatt, B.A. (2004) Intramedullary Nailing in Open Tibia Fractures: A Comparison of Two Techniques. International Orthopaedics, 28, 235-238.

- Agrawal, A., Vijendra, D. and Rajesh, K. (2013) Primary Nailing in Open Fractures of the Tibia—Is It Worth? Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8, 504-510.

- Salem, K.H. (2012) Critical Analysis of Tibial Fracture Healing Following Unreamed Nailing. International Orthopaedics, 36, 1471-1477.

- Sanders, R., Jersinovich, I. and Anglen, J. (1994) The Treatment of Open Tibial Shaft Fracture Using an Interlocking Intramedullary Nail without Reaming. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 8, 504-510.

- Kakar, S. and Tornetta, P. (2007) Open Fractures of the Tibia Treated by Immediate Intramedullary Tibial Nail Insertion without Reaming. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 21, 153-157.

- Penn-Barwell, J.G., Bennett, P.M., Fries, C.A. and Kendrew, J.M. (2013) Severe Open Tibial Fractures in Combat Trauma: Management and Preliminary Outcomes. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery, 95B, 101-105.

- Khatod, M., Botte, M.J. and Hoyt, D.B. (2003) Outcomes in Open Tibia Fractures: Relationship between Delay in Treatment and Infection. Journal of Trauma, 55, 949-954.

- Mouit, B., Gordon, G.H. and Marc, S.F. (2001) Treatment of Open Fractures of the Shaft of the Tibia. A Systemic Overview and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Bone Joint Surgery, 83-B, 62-68.

- Gordon, J.E. and O’Donnell, J.C. (2012) Tibia Fractures: What Should Be Fixed? Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 32, 52-61.

- Parrett, B.M., Matros, E., Pribaz, J.J. and Orgill, D.P. (2006) Lower Extremity Trauma: Trends in the Management of Soft Tissue Reconstruction of Open Tibia-Fibula Fractures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 117, 1315-1322.

- Finkemeir, C.G., Schmidt, A.H. and Kyle, R.F. (2000) A Prospective Randomized Study of Intramedullary Nails Inserted with and without Reaming for the Treatment of Open and Closed Fractures of the Tibial Shaft. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 14, 187.

- Vineet, J., Aggrawal, A. and Pankaj, J. (2005) Primary Unreamed Intramedullary Locked Nailing in Open Fractures of Tibia. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, 39, 30-32.