Open Journal of Biophysics

Vol.06 No.04(2016), Article ID:71661,108 pages

10.4236/ojbiphy.2016.64012

Motoyosi Sugita―A “Widely Unknown” Japanese Thermodynamicist Who Explored the 4th Law of Thermodynamics for Creation of the Theory of Life

Kazumoto Iguchi

Kazumoto Iguchi Research Laboratory (KIRL), Tokushima, Japan

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: September 6, 2016; Accepted: October 28, 2016; Published: October 31, 2016

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to introduce to you, the Western people, nowadays a “widely unknown” Japanese thermodynamicist by the name of Motoyosi Sugita and his study on the thermodynamics of transient phenomena and his theory of life. This is because although he was one of the top theoretical physicists in Japan before, during and after WWII and after WWII he promoted the establishment of the biophysical society of Japan as one of the founding members, he himself and his studies themselves have seemed to be totally forgotten nowadays in spite that his study was absolutely important for the study of life. Therefore, in this paper I would like to present what kind of person he was and what he studied in physics as a review on the physics work of Motoyosi Sugita for the first time. I will follow his past studies to introduce his ideas in theoretical physics as well as in biophysics as follows: He proposed the bright ideas such as the quasi-static change in the broad sense, the virtual heat, and the field of chemical potential etc. in order to establish his own theory of thermodynamics of transient phenomena, as the generalization of the Onsager-Prigogine’s theory of the irreversible processes. By the concept of the field of chemical potential that acquired the nonlinear transport, he was seemingly successful to exceed and go beyond the scope of Onsager and Prigogine. Once he established his thermodynamics, he explored the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics for the foundation of theory of life. He applied it to broad categories of transient phenomena including life and life being such as the theory of metabolism. He regarded the 4th law of thermodynamics as the maximum principle in transient phenomena. He tried to prove it all life long. Since I have recently found that his maximum principle can be included in more general maximum principle, which was known as the Pontryagin’s maximum principle in the theory of optimal control, I would like to explain such theories produced by Motoyosi Sugita as detailed as possible. And also I have put short history of Motoyosi Sugita’s personal life in order for you to know him well. I hope that this article helps you to know this wonderful man and understand what he did in the past, which was totally forgotten in the world and even in Japan.

Keywords:

Unknown Japanese Thermodynamicist, Motoyosi Sugita, Thermodynamics of Transient Phenomena, Virtual Heat, Broad Quasi-Static Change, Chemical Potential, Field of Chemical Potential, Diffusion Phenomena, Number of Partition, Dissipation Function, Onsager’s Theory of Irreversible Processes, Prigogine’s Least Production of Entropy, 4th Law of Thermodynamics, Maximum Principle, Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle, Bellman’s Optimality Principle, Theory of Metabolism, Theory of Life, Cybernetics

1. Introduction

Who knows Motoyosi Sugita? Who is Motoyosi Sugita?

The name of Motoyosi Sugita (see Figure 1) is “widely unknown” all over the world today. It is so as well even in Japan nowadays. In this paper I would like to introduce you to this important Japanese theoretical physicist.

Figure 1. Dr. Motoyosi Sugita (Born August 1905-Died 14 January 1990). The picture was taken at the age of 29 in front of his house in Tokyo, Japan in Summer in 1934. His son Yūkiti was born in May in this year. Yūkiti passed away on the 2nd of August in 2012 (By courtesy of Ms. Setsu Honda).

I did neither know his name nor his work until this spring in 2016. As I started recently writing a paper on the theory of thermodynamics in the irreversible processes, I found him, this brightest fellow in the early stage of Japan after WWII. Actually he was one of the top figures in the theoretical physicists in Japan right after WWII.

Motoyosi Sugita founded the Japanese Biophysics society as one of the first founding members. To start up the society, in order to show how the scientific society of Bio- physics was important to the Japanese Government, they presented a book on Biophysics as the proceedings of the first meeting among the Japanese Biophysicists [1] . In the part III of this book, Motoyosi Sugita wrote a review, “The Biological Open Systems and Fluid Equilibrium”, where his use of the words “Fluid equilibrium” was meant the so-called “Dynamical equilibrium”. It was his life-time objective to construct “Thermodynamics of life”.

As I read any one of his articles, I have been impressed by his very deep thought on Life as well as Thermodynamics. His ideas seem to me very important and crucial for understanding the physical aspects of life, and therefore, very prompt for making a breakthrough in the research of theoretical biology. Thus, in this paper I would like to summarize what I have studied from his works.

1.1. Birth

Motoyosi Sugita was born in Yatsushiro-machi in Kumamoto prefecture in Japan on August in 1905. Exact day of the born was not known so far. His father was Heishiro Sugita and his mother Haya Sugita. They had the first boy, but the boy was gone by sick before Motoyosi was born. So, Motoyosi became the officially first son of their family. His father Heishiro was the school teacher, later became a principal so that he went many places for teaching as a principal. During Heishiro was spending time at Kumamoto with his mother, Motoyosi was born.

1.2. Education

He graduated from the elementary school attached to the Kochi Teachers College and entered the Dai-ichi Junior High School in Kochi prefecture in 1919.

In 1921 he was admitted to the Konan Junior High School in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, moved from the Junior High School in Kochi. At this time most of good high schools in Japan had both junior high school and high school as one school system for 5 - 6 years. The Konan High School was one of them.

In 1926, he graduated from the physical science division in the Konan High School and entered the Department of Physics, the Faculty of Science, the Tokyo Imperial University.

In 1929, he graduated from the Department of Physics, the Faculty of Science, the Tokyo Imperial University. The Tokyo University at that time was under the old system of the Great Empire of Japan, which was totally different from the modern university system of Japan after WWII. Hence, the Tokyo Imperial University was perfectly different from the Tokyo University nowadays. The former was only for the top rank brilliant students selected from them in the Japanese society at that time.

1.3. Working

In 1929, He was enrolled as a researcher at the Institute for Electricity (Denki- Shikenjo), the Ministry of Traffic and Postal Affairs (Teishin-sho).

In September in 1934, he became a teacher at the School for the Japanese Navy Organization.

In August in 1941, he retired the School for the Japanese Navy Organization and became a researcher in Kobayasi Institute in Tokyo (see Figure 2). Here he published his first text book “Thermodynamics New Lecture” in 1942 [2] . He became a lecturer at the Department of Industrial Management, the Tokyo Commercial University.

In March in 1944, he became a professor at the Department of Industrial Man- agement, the Tokyo Commercial University. In April, he also worked as a lecturer at the Tsudajyuku University.

In June in 1949, he became a professor at the Department of Economics, the Hitotsubasi University (see Figure 3). As a concurrent post he became a professor at the Department of Commercial Science, the Hitotsubasi University (until it was re- pealed by the school system change by the Government in 1951).

In September in 1949, he earned the Ph.D. in Science from the Kyoto University by the doctoral thesis “Thermodynamics of Transient Phenomena”, whose partial fulfil- ment was published as a book “Thermodynamics of Transient Phenomena” from Iwanami-shoten in 1950 [3] .

In April in 1953, as concurrent posts, he became a professor at the Department of Sociology, and at the Department of Economics, the Hitotsubasi University. At the same time, he was promoted to be a lecturer for Condensed Matter Physics, at the Department of Engineering, the Meiji University.

Figure 2. Personnels of “Kobayasi Riken” in 1945. The picture was probably taken in front of the Kobayasi Institute (Kobayasi Rigaku Kenkyujo, shortly Kobayasi Riken), Tokyo, Japan, in March in 1945, right after WWII. Dr. Motoyosi Sugita is the second person from the left in the second row (By courtesy of the Kobayasi Rigaku Kenkyujo).

Figure 3. Prof. Motoyosi Sugita. The picture was probably taken at the age of 74 in the home office of his house, Tokyo, Japan in 1979 (By courtesy of Misuzu Shobo).

In September in 1956, he became a professor both for the Tokyo Commercial University and Hitotsubashi University until it was repealed by the school system change by the Government in 1962.

In April in 1959, he became a lecturer for the intensive lecture for Modern Technology at the Department of Management Sicence, the Konan University and a lecturer for the intensive lecture for the General Commercial Engineering, at the Department of Economics, the Ooita University.

1.4. Marrige

Motoyosi Sugita married Ms. Grace Sakae Oyama in 1933 (see Figure 4). Grace is her Canadian name. She was a Japanese originated Canadian whose ancestry was Christian and immigrated from Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan. She was born in Toronto, Canada. She graduated from the Victoria High School in Toronto. She entered the Nursing School there and graduated at the top of the school. She became the first nurse of the Japanese- Canadians in Canada.

She came to Japan for marriage with Motoyosi Sugita, leaving her family in Canada in 1933. During WWII, she spent very sad time because Japan and Canada became enemy each other, and her family in Canada was forced to be sent to the concentration camps in Canada. Long after WWII, when they visited USA and Canada for attending the International conferences for biophysics and bioengineering, she was able to meet her family members in Canada for the first time in 28 years.

They had one son, Yūkiti. Yūkiti went to Indonesia for his business after Motoyosi and Sakae died. However, he failed his business and he returned back to Japan. He spent his final days in his family’s summer house in Hokuto-shi, Yamanashi, Japan. Yūkiti died on 2 August 2012. Only one relative of Motoyosi Sugita’s family is Ms. Setsu Honda who lives in Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan. Other relatives are now living only in

Figure 4. Prof. Motoyosi Sugita and his wife, Grace Sakae Sugita. The picture was taken at his age of 56 in front of her parents’ home in Hirosaki, Aomori, Japan in July, 1961, when they visited there for their greeting to the family right before they went to attend the Conferences in Canada and USA. During the visit abroad she was able to meet her family and relatives in Canada for the first time in 28 years since she came to Japan for her marriage with him (By courtesy of Ms. Setsu Honda).

Canada.

The above information was sent as a letter from Ms. Setsu Honda as her courtesy. I really appreciate it from the bottom of my heart.

1.5. Visits Abroad

In July in 1961, he visited the United States of America and Canada for three months. He attended the 4th International Conference on the Medical Electronics held at New York and the International Conference on Mathematical Biology held at North Carolina.

In August in 1965, he visited the U.S.S.R., Austria, Italy, France, England, West Germany, and Denmark for three months. He attended the International Conference on Molecular Biology held at Napoli, Italy and the second International Conference on Biometrics held at Helgoländ, West Germany.

At the time, he became the president for Bioengineering of the Japanese Society for Medical and Biological Engineering (until 1967).

In 1967, he visited the U.S.S.R., Sweden, West Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Swiss, Austria for three months. He attended the 7th International Conference on Medical Electronics held at Stockholm, Sweden and the 3rd International Con- ference on Biometrics held at Helgoländ, West Germany.

In 1969, he retired from the Hitotsubashi University and became a professor emeritus (see Figure 5).

On the 14th day of January in 1990, he passed away at the age of 85.

Figure 5. Prof. Motoyosi Sugita. The picture was taken at his age of 80 in front of his second house in Hokuto-shi, Yamanashi, Japan in August in 1985 (By courtesy of Ms. Setsu Honda).

1.6. Publications

Motoyosi Sugita published many textbooks [1] - [6] as well as the general books, which were all written in Japanese such as Soceity and Cybernetics [7] , What is Cybernetics? [8] , W. Heitler: Thinking and Wanderings [9] , What is Information Science? [10] , Society and Theory of Systems [11] , Recommendation of Engineering Thinking [12] , The Function of Academics and Creation [13] .

At the same time he published many important scientific papers. Before WWII, he published papers written in German [14] - [21] . After WWII, he published many papers in the Japanese science journals for the public such as Kagaku (meaning Science) and Seibutsu Kagaku (meaning Bioscience) [22] - [35] and Iryo Denshi to Seitai Kogaku (meaning Medical Electronics and Bioengineering) [36] [37] . He published many Japanese articles in his working place reports: in the journal of Kobayasi Institute such as the Bulletin of Kobayasi Institute [38] - [59] ; and in his Hitotsubashi University journals such as the Annals of Hitotsubashi University [60] [61] [62] , Hitotsubashi Ronso [63] [64] [65] [66] [67] , the Bulletin of Hitotsubashi University [68] - [75] . He also published many papers written in English in Western Journals such as the Journal of Physical Society of Japan [76] [77] [78] [79] [80] and the Journal of Theoretical Biology [81] - [91] , as in the references. And also he published many other papers on Physics education and Mathematics education as well, which are neither included nor listed in this paper. You can just see them in the National Diet Library, “Kokkai Toshokan”, of Japan [92] .

1.7. The Research History of Motoyosi Sugita

As early as in 1930’s before WWII, he started to study physics. During this time, at first he seemed to spend much time to translate German physics papers written in Germany (Deutschland) such as Carl Wagner [93] and Georg Siemens [94] into the Japanese and published the articles to the Journal of the Mathematical and Physical Society of Japan (Su-butsu Gakkai Shi). Once he found the concept of the virtual heat, he applied it to the thermodynamics of transient phenomena, and in doing so, he published papers in German in the Japanese journals [14] - [21] .

Thus he seemed to be an expert for the German language in the Japanese physics society at that time before WWII, since in the Japanese education system at that time the Japanese education system had been admirringly adopted from the German system as the first foreign language in the schools in Japan. And surely before WWII, Germany was one of the top countries in sciences including Chemistry and Physics at that time.

Although it has been perfectly forgotten already, Japan was a leading long-time economical supporting country for Germany that was economically totally broken by the WWI. Many Japanese business men privately supported the German society as well. A famous example was Hajime Hoshi who was one of the richest fellows in Japan at that time and he was the founder of the Hoshi Pharmaceutical Company and the Hoshi College of Pharmacy. Hajime Hoshi had supported the Chemical Society of Germany for a long time until Germany would recover [95] up to the era of the Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich of Germany.

Nearly ten years before WWII, Sugita published several famous papers in German as well as in English in the Japanese journals [14] - [21] as mentioned above. However, after WWII his works seemed to be ignored in the Japanese physics society. Because since then, the Japanese education systems totally changed to fit with the English-based society of U.S.A. from the German-based society of Deutschland before WWII. This changed to adopt English as the first foreign language instead of Germany in the schools.

Motoyosi Sugita studied the foundation of thermodynamics for biological systems [2] , and continued it after WWII. From the line of his German physics study which was the top physics country at that time mentioned above, he studied the theory of the German physicists, Becker and Döring [96] and Volmer [97] and an American physicist Frenkel [98] on the cluster growth in the metastable phases in supersaturated vapors.

As early as in 1948 right after the damage of WWII slightly reduced in the society, Motoyosi Sugita published an important paper that discussed the relationship between the metastable (or quasi-static) phenomena in thermodynamics and biological pheno- mena in the Japanese journal, Kagaku [23] . It was also published in the textbook entitled by Thermodynamics of Transient Phenomena [3] .

As the Japanese society was coming back till 1950 he published a more fundamental paper in a Japanese journal, Seibutsu Kagaku [29] . After a long study on the theory of thermodynamics in the transient phenomena such as life, he first postulated that there might exist the 4th law of thermodynamics; otherwise one cannot understand biological phenomena. He stated his considerations on it in §5 entitled by “Can one consider the 4th law of thermodynamics?”. I would like to quote here in the corresponding part from its English version [60] as follows:

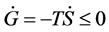

…By the way, let us think here the circumstance deeply. According to the 2nd law of thermodynamics, Gibbs’ free energy, G, of the world has tendency to decrease in isothermal and isometric change. On the other hand, we find the tendency that the velocity of decreasing of G, i.e.,  wants to take a large value as far as possible. This might be a general principle of nature which I should like to call temporarily the 4th law of thermodynamics.

wants to take a large value as far as possible. This might be a general principle of nature which I should like to call temporarily the 4th law of thermodynamics.

The foundation of such a large principle will be discussed later, and we can suggest here that it is very important and beneficial idea that the nature of the transient phenomena as well as the living system may be clarified and explained uniformly by this principle.

There are many delicate problems concerning human thought if we propose to clarify the nature of life on the basis of physical and chemistry. In any way the matter looks like as if it were concerned in the 4th law. …

Hence, following the line of thought of Motoyosi Sugita [29] , I can summarize the laws of thermodynamics as follows:

1) The first law (W. Thomson’s principle): The Gibbs free energy G is conserved in a closed system; .

.

2) The second law (Clausius’s principle): The entropy S always increases in any process; .

.

3) The third law (Nernst’s theorem): The entropy approaches zero as the absolute temperature T approaches zero; .

.

4) The 4th law (M. Sugita’s postulate): The decreasing rate of the Gibbs free energy always takes the maximum in any process;  = max, where

= max, where .

.

Fortunately Sugita published the above paper one year later in English [60] . But it was unfortunate since the journal of the Hitotsubashi university (to which he belonged) that he published was not famous at all among Western physicists as well as the Japanese physicists. And also it has not been available to the public for so long until recently after the internet service was provided.

In 1953 Motoyosi Sugita has found the way to apply the theory of thermodynamics of transient phenomena to more realistic biosystems such as metabolic systems [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [76] [77] [78] [79] . From this stage his research entered the second stage to construct the thermodynamics of life. Step by step his way of thinking became cybernetics-like, where the feedback control systems played an important role in his theory [46] - [59] [81] [83] - [91] . One of them was cited in Steuart Kauffman’s famous book, The Origins of Order [99] .

Since no computer system was easily available for the bio-systematic calculations in Japan at that time, Motoyosi Sugita collaborated with electrical engineers to construct analog-digital computer circuits for their calculations. They simulated the circuits to obtain the solutions of their-own models of the metabolic control systems. These ideas were summarized as books [1] [5] [6] .

After retiring the Hitotsubashi University, Motoyosi Sugita became to write and publish many general books to the community [7] - [13] .

Although he published many papers and textbooks in science as well as many general books in Japanese, he published only about ten papers in English by unknown reasons. That is why he was so unknown in the Western countries as well as in Japan. Hence, nobody knew him nowadays, and so did I, in spite of his extremely important contributions to the thermodynamics theory.

In this paper I would like to review some important consequences of his theory and discuss the maximum principle in the open non-equilibrium systems as the foundation for the 4th law of thermodynamics to the readers especially in the Western countries.

In Section 2, I will show the bright ideas of Motoyosi Sugita such as the concepts of the broad quasi-static change, the irreversible cycle, and the virtual heat.

In Section 3, I will discuss the Motoyosi Sugita’s approach to the diffusion pheno- mena as the first successful application of his concepts.

In Section 4, I will review the theory of phase change and condensation as a preparation for understanding the following sections.

In Section 5, I will present the theory of thermodynamics of transient phenomena of Motoyosi Sugita, where his theory of chemical reactions will be shown using the concept of the field of chemical potential.

In Section 6, I will show the Motoyosi Sugita’s concept of the maximum principle in the transient phenomena. Here  = max conjecture will be discussed, which is a demonstration for the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics.

= max conjecture will be discussed, which is a demonstration for the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics.

In Section 7, I will compare the work of Motoyosi Sugita and those of Lars Onsager and Ilya Prigogine. I hope that the content of this section will be shared with the Western people.

In Section 8, I will discuss the maximum principle of Motoyosi Sugita and that of Pontryagin as well as the Bellman’s principle of optimality. This includes my own theory of the application of the Pontryagin’s maximum principle to thermodynamics. Therefore, I believe that this section is as my emphasis most important among other things.

In Section 9, I will show the Motoyosi Sugita’s theory of metabolism which is the first application of his maximum principle to theory of life. He spent many years as many as 20 years for studying this problem from many sides repeatedly.

In Section 10, I will present the Motoyosi Sugita’s way of thinking on the theory of life. This opens up the thermodynamics of life or life being as well as the network thermodynamics.

In Section 11, as the final section, a simple summary will be made.

2. The Bright Ideas of Motoyosi Sugita

A couple of years after Onsager published his seminal papers on the reciprocal relations in the irreversible processes in 1931 [100] [101] , Motoyosi Sugita published the theory of thermoelectric effects and the Kelvin’s relation in 1933 [17] . This was much later published in Japanese in the Japanese journal during WWII [20] [21] and included in his new text book of theromodynamics, “Netsu Rikigaku Shinko”, meaning Thermo- dynamics New Lecture [2] . In this research he introduced the concept of broad quasi- static change, the virtual heat, and the irreversible cyclic processes in order to describe the irreversible changes in thermodynamics of transient phenomena.

2.1. Sugita’s Concept of the Broad Quasi-Static Change

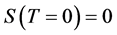

Motoyosi Sugita [2] [3] meant the quasi-static change “in the broad sense” by the naming of the broad quasi-static change. The broad quasi-static change is defined when the following conditions may be assumed:

(2.1)

(2.1)

where  and

and  are some functions of V and T, respectively.

are some functions of V and T, respectively.

These are a generalization of the conditions for the case of ideal gases where

and

and  are satisfied with k being the Boltzmann constant. When

are satisfied with k being the Boltzmann constant. When

these conditions are assumed to be satisfied, one can almost follow the standard approach of the quasi-static processes in thermodynamics which means that the process is indefinitely very slow. Indeed, even in the non-idealistic cases the treatment of the quasi-static change in the normal sense has been applied and given plausible results.

This means that the local equilibrium can be satisfied even in the non-equilibrium states, where the broad quasi-static change makes sense if one excludes the relaxation phenomena in which conditions 1) and 2) are not satisfied. Unless the relaxation phenomena are considered, the broad quasi-static change can be applied to most of irreversible processes. The concept of the broad quasi-static change has the amazing possibility of development, once it is combined to statistical mechanics.

Suppose that many macroscopic parts are in the equilibrium state. Let us denote by  the entropy of that i-th small part and by

the entropy of that i-th small part and by

Therefore, if we use

then we have

This means that when one considers the broad quasi-static change in the irreversible processes, one should not take or need not take the W or Z over the entire phase space. One must cut off the phase space into the small pieces that are in local equilibrium, and concatenate them to cover the whole phase space. This is the meaning of the local equilibrium in the point of view of Motoyosi Sugita.

2.2. Sugita’s Concept of the Virtual Heat

Another assumption that forms the theory of irreversible processes is the concept of the virtual heat. Let us consider the case when the heat

is satisfied, where

Substituting Equation (2.5) into Equation (2.A), we obtain

This

where

Now, from the concept of the broad quasi-static change,

Here we never think as if

holds true.

If we think of the adiabatic change without input and output of heat, i.e.,

Hence,

What is important here is the distinction between

In Equation (2.5), if the work

For the outside of the system, the reservoir gives the heat

Therefore, for the whole system we have

Thus, the Sugita’s concept of the virtual heat is very natural and important when one considers the thermodynamics of transient phenomena.

2.3. Sugita’s Concept of the Irreversible Cycle

Let us now consider the Sugita’s concept of the irreversible cycle. Let us denote by

since the reservoir gives the heat

Let us denote respectively by T and S the temperature and the entropy of the system (working material) that performs the cycle. Then we have

since the system receives the heat

After finishing the cyclic process, the system has to come back to the initial stage of the process (i.e., the initial condition) such that it yields

Hence, the total entropy change in the cycle is given by

On the other hand, for reversible processes, since

one has

Thus, the entropy change occurs only in the thermal reservoir outside the system in the process of the irreversible cycle, such that Equation (2.18) cannot conflict with the second law of thermodynamics. The equality of Equation (2.18) has a great meaning

that the integration of

irreversible cycle. Therefore, one can treat quantitatively the thermodynamics of the irreversible cycle in the same as that of the reversible cycle.

I would like to note that this aspect of the Sugita’s concept of the irreversible cycle is different from that of the Prigogine’s concept of the irreversible cycle, where the entropy change of the system is treated as a quantity that always increases during the process such that

Now let us consider the change in the thermal reservoir. The heat

since

called the reduced heat. However, the reduced heat is not a real heat for the reservoir, since the sign of it is reverse to that of entropy of the reservoir [Equation (2.22)]. Thus, although the concept of the reduced heat plays a historical role, it is not so important as a physical quantity. From Equation (2.19) together with Equation (2.15) the following holds

This is nothing but the Clausius’ inequality for the irreversible cycle, where the equality holds true for reversible processes. This can be regarded as the generalization of the standard proof for the Clausius’ inequality for the irreversible cycles [2] [3] [4] [113] .

Historically speaking, Clausius accomplished to derive this relation for the first time. From the fact that the equality holds true in the reversible processes, he showed that

represented a closed curve representing any thermodynamic cycle by a staircase with adiabatic curves and isothermal curves. Regarding the cycle as a combination of many infinitesimal Carnot cycles, for the high temperature sources, denote by

Now if the intervals could be made so as to be infinitesimally small, then Equation (2.24) becomes

This is the Clausius’ inequality derived from himself [113] .

However, once we look at the expressions in Equation (2.24), the sign of the reduced

heat

quasi-static reversible processes it becomes exactly the entropy change of the working material and hence the equality of the above Equation (2.25) can hold. From this situation, usually it has been thought that one cannot treat the theory quantitatively since the inequality holds in the irreversible processes or when one seeks for the

entropy by

because one escapes from the complexity of the irreversible processes such that one need not take into account the working material, and because one discusses the cycle process only considering the lost heats. On the other hand, although not always but when the process can be regarded as the broad quasi-static change, and when the true character of the virtual heat is clearly known such as the friction heat or thermal conduction, we can take

Since the state goes back to the initial state after the completion of the cycle, it seems trivial that the entropy goes back to its initial value as well. Since it was said that in the irreversible processes, one cannot say anything about the entropy in the midst of the process, we could not have said anything about like the above. Now we should note that

In order to derive the entropy, one must consider the quasi-static reversible processes and define the heat of the processes in the standard point of view as usual. But once one defines the entropy under the quasi-static change, one can use the relation

This is the argument of Motoyosi Sugita for the concepts of the broad quasi-static change, the virtual heat and the irreversible cycles in the thermal processes. He applied these concepts to the various physical systems such as the thermoelectric effects of Lord Kelvin [2] [3] [4] [14] [15] [17] [20] [21] as well as many biological systems [38] - [91] .

2.4. Application to the Kelvin’s Relation in the Thermoelectric Effect

As an application of the above results, we become able to treat the problem of thermoelectricity (see Figure 6), which had been thought to be difficult to consider. Now, let us denote by (1) the high temperature part with the temperature

Seeing from the outside of (1), the ejected heat per second

Next, let us denote the resistance by

This is the so-called Peltier heat. If we take

Figure 6. The system of thermoelectric effects.

For the part (2), we similarly obtain

where the minus sign in the left hand side comes from the reverse direction of the current i in the circuit.

Next consider the part

This is coreesponding to the quantity

Similarly for the wire B and considering the part

where the sign in the right hand side is due to the condition that the direction of the temperature is reversed to the direction of the current i.

In the stationary state, the sum of the heats that this system absorbs equals the work that the electromotive force E can do. Hence, one has

which is the equation corresponding to the relation (2.B) but its integrated form, where the integration of

Next, suppose that the relation

It is obvious when the thermoelectric couple is in the stationary state. Then the entropy change occurs only in the thermal reservoir (or one may think the one-round of electron through the circuit as a cycle.) From Equation (2.32) and Equation (2.33), the Kelvin’s relation is given by

So far we are based on the Clausius’ inequality:

Now, rewriting

The derivation of the above result Equation (2.37) is as follows: Denote by

For the wire A we find

By integration by parts we obtain

On the other hand, for the wire B we similarly obtain

respectively. Here we think that

Therefore, based on the inequality (2.37), one cannot derive the Kelvin’s relation, as long as the thermal conduction and Joule’s heat can be neglected. Namely, to take Equation (2.37) as the base is not wrong but not sufficient [3] . As Boltzmann [114] had shown the following relation

this cannot exactly yield the Kelvin’s relation.

Now, from Equation (2.36) the linear term of

This means that if Equation (2.36) is added a small quantity less than 0, then Equation (2.37) forms an inequality. Therefore, it is obvious that one cannot derive the desired result from it. On the other hand, we obtain Equation (2.36) by not only considering the heat flowing in from the outside of the system but also considering the heat that the system absorbs. And by this we can derive the Kelvin’s relation exactly.

In summary, the point of view of Motoyosi Sugita lies in the fact that one can obtain Equation (2.36) even for the irreversible cycles. Now, the entropy increase can be obtained immediately from Equation (2.46). Motoyosi Sugita [2] [3] [4] [20] [21] pointed out the insufficiency of the Tolman’s argument [115] in the same problem.

3. Sugita’s Approach to the Diffusion Phenomena

Let us next consider the Motoyosi Sugita’s approach to the diffusion phenomena [3] . In order to see how the concepts of the broad quasi-static change and the virtual heat work in each physical problem, he applied them to the diffusion problem [3] . The diffusion phenomena are really important phenomena when we construct the theory of thermodynamics in transient phenomena. To do so, I would like to follow his argument in his test book [3] .

3.1. Langevin Equation

Now let us consider an ideal gas that is constructed from the mixing of the two species of molecules 1 and 2. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that the density gradient only exists in x direction. This is equivalent to consider the one-dimensional diffusion problem along x direction.

Let us denote by

Hence,

Now, let us denote by

where

Or if we use

Now taking as

where

then the above equation looks like the Langevin equation type such as

So far we have considered the case of ideal gases. However, for more general cases, if we use

the right hand side of Equation (3.6) can be rewritten as

or if we use

As Sugita pointed out, the Langevin equation is the equation of motion that one thinks as if the stationary motion is considered statistically so that the effect of accele- ration cannot play a role to the averaged velocity, and the random forces come from like-particles in thermal motions are statistically averaged.

Next let us explain that when the work done by the resistance of friction

3.2. Mixing Entropy and Free Energy

Now let us denote by

where

If the equation is reversely seen, then the chemical potential has to be defined by

Now, since the G is decreasing by the mixing, from Equation (3.9) we have

This means that in the mixing system of ideal gases, the mixing entropy is increasing by the mixing of the molecules and by it G is decreasing. And although the decrease of G is the decrease per second in the irreversible process, we cannot necessarily know but surely know the change in time of G in the midst of the process.

Based on the Langevin equation Equation (3.6'), suppose that the molecule is forced to move by

For the sake of simplicity let us limit ourselves to the ideal gases. Then, only the energy per molecule

If we assume the process is an isothermal change, then replace

The first term in the right hand side vanishes if the boundary condition is taken. In the second term in the right hand side, since we have the continuity equation:

if we change

On the other hand, in the ideal system the change in G only occurs in the change of entropy. Therefore, if we rewrite

Hence, this agrees with Equation (3.11). From considering the above situation, we can recognize that the assumption that the force acting on the diffusion particle is given by Equation (3.6’) is not inconvenient.

Let us consider the case of the non-ideal systems [28] . In this case the chemical potential

Therefore, once we add the heats due to Equation (3.15) and Equation (3.16) to the above increase of entropy due to

This is not inconsistency but rather everything is consistent very much. If we compare the above with Equation (3.16), then

This means that

3.3. How to Count the Number of Partition

For this title, Motoyosi Sugita used the word the number of complexion. The number of complexion is nothing more than the number of partition in classical statistical mechanics or the number of sates in quantum statistical mechanics in the modern terminology [116] [117] . When the system is in equilibrium, the number of ways that particles interchange their positions in the system is nothing but the number of complexion in his terminology. In this equilibrium case, one can definitely define the chemical potential such as Equation (3.8).

Can such a treatment be allowed even in the midst of the non-equilibrium process? This was the Motoyosi Sugita’s problem. Obviously, it is allowed for the equilibrium state of the process. But it is not trivial for the non-equilibrium state in the irreversible or transient phenomena.

Suppose that the previous argument that provides Equation (3.8) is correct [28] . Assume that

where

Hence, by taking the functional derivative for the above with respect to

The second term in the right hand side comes from the mixing entropy of the system. Therefore, it corresponds to what one assumes that the number of partition at an instantaneous time in the midst of the process is given by

If we take

Now, suppose that the whole region of space is divided into small parts of

Next, if we remove the partitions and wait for a short time so that the diffusion occurs, and if we place the partitions in the system once again, then the distribution of the molecules becomes different concentrations of

In this way, as the distribution of concentrations is continuously changing by the diffusion, the corresponding region in phase space is also moving continuously through the region corresponding to each state in the midst of the irreversible process and going into the region corresponding to its final equilibrium state. Once the true equilibrium is achieved, not changing or mixing the molecules within the region

There is no limit for time in the equilibrium state, since each process is reversible so that an infinite time can be spent. Therefore, even if molecules are far apart to each other, the state that the molecules exchange their positions can be realized by the ergodic assumption. When the diffusion occurs,

In other words, the molecules within

On the other hand, for each diffusion molecule, it should not move with the constant velocity

In summary, the above argument is the Motoyosi Sugita’s argument on the application of the concepts of the broad quasi-static change and the virtual heat to the diffusion phenomena [3] . He also applied his brilliant concepts to many other systems such as the osmotic pressure for the cell membranes. However, I would like to skip this here.

4. The Theory of Phase Change and Condensation

Before going to discuss the Motoyosi Sugita’s theory of thermodynamics of transient phenomena in detail, let us look at the theory of nucleation or condensation in 1930’s [96] [97] [98] as an excursion.

His theory was motivated to be apply it to construct the thermodynamic theory or thermodynamics of life or life being [3] . In order to construct thermodynamics of life or life being, he presented mainly three big concepts:

1) the “field”of chemical potential;

2) the generalized nonlinear Ohm’s law;

3) the maximum principle in transient phenomena.

He extracted these concepts from intensively studying the theory of phase change and condensation or nucleation originated by the German physicists, Becker and Döring [96] and Volmer [97] and an American Physicist, Frenkel [98] before WWII. Therefore let us first review some of the early theory of nucleation phenomena as a prototype or precursor of the theory of thermodynamics of transient phenomena of Motoyosi Sugita.

4.1. Frenkel’s Theory on Nucleation in the Supersaturated State

When Mayer [120] studied statistical mechanically the nature of vapor, he considered clusters that are aggregated into groups of several molecules in addition to single molecules. Frenkel [98] simplified this idea to phenomenologically represent such groups of several molecules as spherical clusters with a certain radius.

Let us now denote by (n) a cluster with n molecules. Denote by

If we define by

then

Next, define by

then the Gibbs free energy G of the whole vapor is given by

where T is the temperature of the system, k is the Boltzmann constant. Here

When the mixing entropy between single molecules and clusters with different sizes should be evaluated, the expression of mixing entropy for molecules of identical sizes is assumed and used to this case. This seems a problem. And as n becomes large, the expression for the mixing entropy must be modified. Furthermore, we cannot imagine that big liquid drops can float in the vapor. Therefore, the above expression of the Gibbs free energy is not exact quantitatively. However, if we restrict ourselves to the phenomenological argument, then it seems sufficient to approximately represent the system by Equation (4.4).

On the other hand, let us denote by

Suppose that this mixture of clusters in vapor lies in equilibrium. In this case, seeking for the maximum of G with taking the variations of

or

This is the equation that determines the distribution of (n)-clusters first derived by Frenkel [98] .

This is the distribution of concentrations of (n) clusters in the equilibrium state in the saturated and the supersaturated vapors. It means as follows: When some part of the gas conforms the mixture of (n)-clusters and when the mixture is included in the system, the entropy becomes larger than the one when all the molecules stay as single molecules in the vapor. If we look into each molecule,

4.2. Supersaturated Vapors

Next following the argument of Frenkel [98] , let us consider the supersaturated vapor. When the vapor is supersaturated, since

where if we denote by

Considering Equation (4.8), as n becomes large,

Thus one can understand the behavior of the supersaturated vapor system pheno- menologically. If

Motoyosi Sugita pointed out the following [3] [23] : As stated in the previous section, one can assume that even in the transient phenomena, the expression of

Now, the cause that interrupts the changeover from the vapor phase to the liquid phase is the lack of the surface area which leads to the condensation. In order that the liquid phase emerges in the supersaturated vapor phase, it has to pass through the state of extremely small liquid drops in the midst of the process. Large clusters are not included in the midst of the growth. Very small is the rate that clusters gradually grow as the condensation occurs at the surface of small (n) clusters. Therefore, the system is at a standstill as a vapor. According to Frenkel [98] , this is the metastable state. The distribution of

Motoyosi Sugita noted here the following: When the Gibbs free energy for the entire system G is decreasing as the second law of thermodynamics shows, there appears some part which has larger Gibbs free energy, and this supports the place where con- densation occurs, and it determines the rate of the change in the transient phenomena.

The reason why clusters have large

Next, let us differentiate Equation (4.8) with respect to n and evaluate the maximum.

Substituting the value of

the liquid, M the molecular weight and

On the other hand, let us denote by

From this we find the Kelvin’s equation:

And if the maximum of

where K is the maximum size of the clusters. According to Frenkel [98] , the cluster of this size is the nucleus of condensation. The range that

In the above argument, we have assumed that in the metastable state the rate of growth of cluster is small enough. And although the system is not in equilibrium, we have treated it as if it were in equilibrium. This provides the variation principle

4.3. Kinetics of Cluster Growth

According to Becker and Döring [96] , the growth of the cluster is carried out in the following process:

Here 1 stands for a single molecule and it collides with (n), the cluster consisting of n molecules and condensates into

and so on, the probability of these processes must be very small enough compared with that of the collision process of Equation (4.14), since triple collisions or the collision between (3) and 1 are molecular dynamically very few events such that they loose the meaning to form

Volmer [97] slightly improved the calculation of Becker and Döring [96] . In his calculation he denotes by J the rate of the process of Equation (4.14), which is the total number of clusters per time from

where

Now in equilibrium of the growth process, both the forward and backward processes are attained such as

This provides

where N is the total number of molecules in the system such that

In the saturated vapor, it is no wander that Equation (4.18) must hold valid as well. However, even in the supersaturated vapor, the rate J is expected to be small such that

In summary the above theory is the theory of condensation in the supersaturated state originated by Becker and Döring [96] and completed by Volmer [97] and Frenkel [98] in the Western countries before WWII.

4.4. Thermodynamics of Kinetics of Cluster Growth

Motoyosi Sugita investigated the above theories of Becker and Döring [96] , Volmer [97] and Frenkel [98] very carefully.

In considering the kinetics of the cluster growth thermodynamically, since the half of Equation (4.18) could be valid even for the non-equilibrium state and then it holds as well, he rewrote Equation (4.18) as follows:

Denote now by

concentration 1, respectively. Then J is given as

Let us introduce the concept of the chemical resistance

and let us define the chemical potential for a single molecule in cluster (n) in the midst of the growth process by

Then Equation (4.19) can be rewritten as

The above equation looks like the Ohm’s law of

Now, from this point of view the growth process of clusters

can be regarded as a system of resistances in series in an electrical circuit following the Ohm’s law. In the nucleation process the resistance

Motoyosi Sugita noted the following: The mathematical form of Equation (4.22) is much more convenient than that of Becker etc. It is not the equation to show the destiny of the growth and the decomposition of clusters. Each cluster emerges as a result of statistical and thermal fluctuations and the system moves towards its dynamic equilibrium by following the field of force as the needles of a clock move. This idea becomes very important when we think of crystal growth and life being. What is important here is not the quantitative treatment but the qualitative treatment of the theory. In order to introduce the concept of the field of chemical potential, i.e., the m-field, the expression of J was written in the form of Equation (4.22) in terms of the chemical potentials

5. Thermodynamics of Transient Phenomena of Motoyosi Sugita

As is noticed in the above, the theoretical framework of the above theory is very general. Becker and Döring [96] as well as Volmer [97] applied it to the two-dimensional crystal growth on the surface of crystal. Indeed Motoyosi Sugita applied it to many physical systems in the broad quasi-static change or in the metastable state from physics to biology [4] [5] [6] [41] - [91] . In this section, I would like to focus our attention on the application to chemical reactions.

5.1. Motoyosi Sugita’s Theory of Chemical Reactions

Let us consider the chemical reaction of the following form [104] :

where

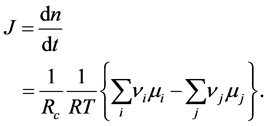

On the other hand, Motoyosi Sugita [3] [60] frequently used the following expression for it:

where

Denote by

species in mole (simply called the mole numbers). Let us denote by

where

reaction or degree of achievement and the reaction rate by Theophile De Donder [102] [103] [104] , respectively.

On the other hand, Motoyosi Sugita used

where i and j stand for the reacting and produced molecules. In this way Motoyosi Sugita emphasized the change of molecular numbers in molecular statistics [3] [5] [60] , while the De Donder’s school emphasized the change in the reaction equations [102] [103] [104] .

Following Motoyosi Sugita’s theory [5] , let us define the Gibbs free energy G as

where

It means that if the amount of

is done such that the Gibbs free energy increases. Since the sum in the Gibbs free energy G is linear in

Using the reaction equation of Equation (5.4), we have

where if

where

This is nothing but the Affinity introduced by De Donder [102] and Progogine [103] [104] before WWII as well as Marcelin [122] and Jouguet [123] even before WWI in Western countries.

From the knowledge of thermodynamics, G becomes the minimum when the system goes to chemical equilibrium. Hence, in chemical equilibrium,

This yields the following criterion for the direction of the reaction of Equation (5.2):

This is the criterion given through the concept of affinity.

Let us denote by

Simply suppose that the mixing entropy is approximately given as

where

Substituting these into

This yields

where we have defined as

Rewriting Equation (5.18), the law of mass action in the chemical equilibrium is given by

where

Now let us consider when the system is not in equilibrium. In this case, Equation (5.4) yields the rate equation:

where

Here if we may follow the argument of Prigogine et al. [103] [104] , then we may define as

where

5.2. Motoyosi Sugita’s Concept of the Generalized Nonlinear Ohm’s Law

Following the theory of Motoyosi Sugita [5] , let us define the chemical resistance

Here I would like to note the following: If we rewrite as

respectively, then we can derive the relation of detailed balance:

Thus, the equation for

Motoyosi Sugita jumped over the standard way of thought and he assumed that the chemical potential is meaningful even when the system is not in equilibrium yet. Therefore, he assumed for all components of the molecules

Using Equation (5.28) together with Equation (5.25), he was able to rewrite Equation (5.24) as follows:

Applying these into Equation (5.21) or Equation (5.23) and rewriting

was able to derive the following:

This expression has the generalized nonlinear form of the Ohm’s law:

Now we are able to know the following relation:

where

5.3. Motoyosi Sugita’s Concept of the Field of Chemical Potential

Equation (5.31) was first introduced by Motoyosi Sugita long long time ago [23] [29] [60] . He was inspired by the expresson of Equation (4.22). It was derived by Becker and Döring [96] , Volmer [97] and Frenkel [98] (shortly represent BDVF). They studied the theory of condensation considering the nucleation of clusters in the supersaturated state. Therefore, it describes the non-equilibrium state in the irreversible process of condensation.

Motoyosi Sugita recognized that when chemical equilibrium is slightly broken or when chemical reactions are going on, the physical conditions in chemical reactions are the same as those in condensation as well as nucleation. Thus I would like to express schematically the relationship between the Sugita’s J and the BDVF's J in the following:

The mathematical form in

As was discussed before in the previous section, in Equation (5.35) one can derive the above expression for J without any problem. However, the expression for

As an example, let us apply the concept to the condensation on the surface (of either liquid or solid). Denote by J the number of molecules per second that collide with the surface. Denote by

Here

Motoyosi Sugita recognized that this kind of rule for phase change seems very similar to that of the Gibbs’ phase rule for the equilibrium state [126] . In the former phase change occurs as a consequence of the broad quasi-static change in the irreversible process of transient phenomena, while in the latter phase change occurs as a con- sequence of the realization of equilibrium state. Thus there is a conceptual difference between them such as the former is time-dependent and the latter is not time- dependent. However, Motoyosi Sugita postulated the validity of the application of the concept of the field of chemical potential to many biological nonuniform systems such as polymers or macromolecules in protoplasm in cells.

Denote by K a part in a nonuniform system and denote by

and if the chemical reaction in equilibrium in the part K is given by

then the condition

must be satisfied. On the other hand, if the equilibrium is not yet attained, then the kinetic rate equation like Equation (5.35) and Equation (5.36) should be applied to describe the system. Even for dynamic systems such as the system of life or life being, if the system is in dynamic equilibrium such as fluid equilibrium or chemical equilibrium, then we may assume that Equation (5.39) is approximately satisfied in the sense of broad quasi-static change and of local equilibrium. This is the concept of the field of chemical potential introduced by Motoyosi Sugita long ago.

Now, let us turn back to the reason how Motoyosi Sugita noticed the concept of field of chemical potential, for a while. As mentioned in the previous sections, he studied the the quasi-static change in classical thermodynamics in Japan before WWII, where Japan was very isolated from Western countries occasionally dashing to the war. He found the way of exceeding it and called it the broad quasi-static change in quasi- thermodynamics. He understood that chemical potential

In my opinion, it is obvious that his way of thought came from this experience in his physics study, and then he applied the concept to other physical and chemical examples such as chemical reactions. The first look of Motoyosi Sugita for this discovery seems to be the following simple equation:

where

So, Motoyosi Sugita stepped forward to go beyond the equilibrium thermodynamics to the quasi thermodynamics of transient phenomena. Thus, although we think of chemical potential such as a numerical value for the equilibrium state in the standard point of view of thermodynamics, Motoyosi Sugita never thought like this but he always thought that chemical potential is a field defined on space-time such as the field in field theory even for dynamic, nonuniform, irreversible, non-reproducible and transient phenomena. This is his philosophy on the field of chemical potential.

5.4. Relationship between Cooperative Phenomena and Chemical Potential

Motoyosi Sugita further mentioned that the chemical potential plays an important role when the system undergoes phase change. It is not well-known in the recent modern text books in thermodynamics [103] [104] [105] [106] [108] [116] . This is the cooperative effect when the system undergoes a phase change in the irreversible process in transient phenomena. In other words, it can be dubbed the much more modern word, induction-association principle for the phenomena. The word inducetion- association principle was first introduced by Gilbert N. Ling [129] [130] and has been advocated by Gerald H. Pollack [131] [132] for a long time.

This very particular aspect of the phenomena is the following: When the system faces a phase change, if it undergoes the phase change, then it cannot occur so literally, however. Rather, it never occurs even when the temperature of the system already goes below the critical temperature at which the phase change is supposed to occur. This is the supersaturation phenomena, discussed before. At this moment, in order to make the system undergo the phase change, a nucleus or a stimulus, i.e., a kind of trigger is needed for the phase change. Otherwise, it stays still. Conversely speaking, even if the stimulus of a trigger is very very small or microscopically small, the entire system undergoes the phase change. Hence, the effect is very cooperative. This phenomenon is not perfectly understood yet even nowadays.

In order to understand this type of phenomenon, Motoyosi Sugita emphasized the importance of the concept of the field of chemical potential, namely the m-field. According to Frenkel [98] , even in solid, partially melt parts are included near melting point. But the parts do not develop so easily even below the melting point. He put it the name pre-melting. Motoyosi Sugita postulated that in such a case the m-field plays an important role. He imagined that the m-field is always fluctuating thermally or locally under various conditions. One good example is the cluster growth in the previous section. Local raise of the value of m-field promotes the local phase change in the system until the system goes to equilibrium. A local variation of m-field initiates the action at a distance to another point in the system. It is long-range interaction. Thus, local variation of m-field acts as a trigger for the phase change through the long-range interaction of m-field. This is the nucleation in the supersaturated phases.

In this way, the system can communicate through the m-field in the system just like when the electrical potential does. This means that m-field extends the lines of force as an induction of the generalized potential, the m-field. Mathematically, it may be con- sidered as the gradient of the m-field. Therefore, the idea of induction-association principle of Gilbert N. Ling seems very similar to that of cooperativeness of m-field of Motoyosi Siguta.

The cause of such lines of force comes from the m-field. The m-field consists of the mixing entropy term. Hence, the lines of force or the long-range interaction between the parts in the system appears as the consequence of the mixing entropy, e.g., the last term in Equation (5.40). In the standard viewpoint this nature of long-range interaction emerges as a consequence of electric effect. However, Motoyosi Sugita extended the concept such that so is true for the m-field as well. On the other hand, the action of energy is not long-range but local or short-range. Thus, the induction-action principle of Gilbert N. Ling and the cooperative effect of Motoyosi Sugita comes from the mixing entropy, not from the energy of the system.

Can one think of the field in life being as the m-field? He sometimes asked such a question. In such biomaterial or life or life being, the m-field is not made of a single component but is constructed by a huge number of components. Obviously, the structure of the m-field becomes very complex. If so, then it would be very very difficult to calculate the entropy term, calculating the partition number such as in Equation (3.23), since no simple formula exist for such complicated molecular systems. However, in principle and ideally, we can think of the Gibbs free energy G, the number of partition W and the sum of states Z, etc. Then we can expect that the system can move towards the direction of

His conclusion is as follows: The m-field is very long-range enough to affect each other. A slight variation such as temperature fluctuation can be eliminated by the cooperativeness of the entire system. Therefore, when one has to apply thermo- dynamics to the system in considering the entire system as a whole. Especially the second law of thermodynamics is such a law. One must be very careful when he applies the second law of thermodynamics to the partial systems. It is sometimes said the following: Since life is not a closed system, we cannot apply the second law of thermodynamics to life. This seems a ridiculous idea, since it misses the point. While one takes into account the Gibbs free energy, one may consider the partial systems, under the condition that temperatue is constant, one may consider the other parts as thermal sources by which some parts can be affected with other parts through the thermal communication to each other.

5.5. The m-Field, as an Invisible Force

In the previous example of the cluster growth in the supersaturated phase, the clusters grow like this:

Here in between the nearest states of clusters

The field of chemical potential of

In Equation (4.8) as n becomes large,

After the growth processes of non-equilibrium thermodynamics are finished, once such clusters or complicated life being develop their structures, the fully developed structures of such clusters or fully developed complicated structures of life being consist of very large Gibbs free energy by definition. This complicated situation seems to contradict the laws of thermodynamics.

Thus, Motoyosi Sugita noticed that there might exist some kind of hidden law of thermodynamics in addition to the three laws of thermodynamics. He postulated that there might exist the 4th law of thermodynamics which dominates the speed of the transient phenomena as mentioned in the introduction.

6. Motoyosi Sugita’s Concept of the Maximum Principle in Transient Phenomena

In this section, let us consider the most important contribution of Motoyosi Sugita in my viewpoint. As discussed in the previous section, the concept of the filed of chemical potential is quite important when we considerate the non-equilibrium processes.

6.1. Motoyosi Sugita's

As early as in 1950 Motoyosi Sugita wrote a paper entitled in Japanese, Biological Thermodynamics and its Method, which was published one year later from the Annals of the Hitotsubashi University, entitled in English Thermodynamical Method in Biology [60] . He stated in Japanese on the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics [29] as the paragraph quoted in Introduction. And also he first applied his theory of thermodynamics in the transient phenomena to the theory of metabolism.

For the reason why Motoyosi Sugita believed the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics, he listed several examples that seem to be related to this 4th law as follows:

Here let us see many instances suggesting this large principle of thermodynamics.

1) The cascade principle(Stufenregel) found by W. Ostwald [97] shows that the nature has the tendencies as if it wanted to take the pass of smaller resistance or make a de tour and want to establish the equilibrium as fast as possible.

2) Generalizing further the rule described above, it might be said that the nature prefers the line of the least resistance, if there are ways side by side for the equilibrium.

a) According to Volmer [97] , for instance, the crystal formation shows that such a pass is taken actually.

b) Eyring and others [124] [125] called such a process rate determining.

c) Electric current in conductor takes the distribution that heat loss is minimum if the total current takes a given value. Therefore the heat generation must be maximum if the potential difference will be taken as constant. Therefore, if a cell is applied to drive the current, it will take the distribution to dissipate the free energy of the cell as fast as possible.

d) Onsager [100] [101] has derived his reciprocal relation from the principle of least dissipation function. This principle might be considered to the maximum velocity of entropy increase which will be discussed later.

3) If a new passage is built independently which has less resistance than others already existing, then the circumstance above described, that might be the 4th law of thermodynamics, may also be seen from our common sense.

a) The new way may be considered having delicate catalytic action, therefore, large free energy of activation or small entropy. The free energy of activation determines the rate of development of such a passage acting as if the initial cost is to construct a highway. That is why the construction of the way of small resistance is retarded. Nevertheless, it becomes rate determining when it is performed and the old ways become only bypass or will be ruined.

b) The idea of natural selection or struggle for life of biology may be considered as having the relation to this principle. That is the free energy discharged through the old passage is used to the free energy of activation of new way, and the material itself constituting the old way may be useful also as the material of construction (see (v) of VI).

c) Such a circumstance like natural selection can be seen also in the inorganic worlds. For instance, let us observe the nuclear formation of ice in supersaturated water vapor under freezing point, and containing super-cooled water droplets. If the crystal nucleus is formed, not only the condensation occurs on this nucleus, but the super-cooled droplets vaporize and disappear. This is the consequence of the 4th law and the same phenomena can be seen on the discharged plate of PbSO4 of battery and also in the case of recrystallization of metals and others, and they are playing a role to promote the tendency to the thermodynamic equilibrium.

Thus from the early beginning of his research he recognized and imagined the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics, where he expected that some kind of the generalization of the least dissipation of energy of Onsager could be necessary. Therefore, I would like to call his expectation the Motoyosi Sugita’s

In the next section of that paper [29] [60] , VI. Mathematical Theory and Conclusion, he sketched the outline of the 4th law of thermodynamics as follows:

1) First, on the base of microscopic reversibility, Onsager [100] [101] has shown that

where

2) On the same base as Onsager, Landau and Lifshitz have shown that

in their statistical physics [134] .

3) Let us denote by

where

4) Let us consider quasi-chemical processes

between the components. This describes a set of chemical reactions such as chain reaction, whose set is denoted by s. It means that there are many chemical reactions that consist of a finite number set of molecules

5) Let us denote by

Through this linear transformation, the variables

6) Substituting Equation (6.6) into Equation (6.3), we find

where we have defined the affinity

I would like to note here that there is a sign mistake for Equation (6.79) in the English version of this paper [60] .

7) From the rate theory of chemical reaction,

where

8) Inserting Equation (6.9) into Equation (6.7), we can see that

The procedure, which neglected the higher term, corresponds with the cut off method discussed in Section 2. The summation of the right hand side of Equation (6.10) may be interpreted as

9) The reversal of the m-field can be interpreted if we consider the transition from the stage

In the above paper [29] [60] Motoyosi Sugita was not able to present the detail of the proof of the conjecture. It was limited to suggest the existence. However, in the succeeding papers [40] - [46] [48] [61] [75] [77] [78] [79] he argued the sketch of the conjecture and frequently tried to prove it.

6.2. Relationship between the Boltzmann’s H-Function and the m-Field

In order to investigate the Motoyosi Sugita’s conjecture, the so-called Boltzmann’s H-function plays an important role. So, let us first consider the relationship between the Boltzmann’s H-function and the m-Field for the molecular statistics. For this purpose I would like to restrict ourselves to consider the system of chemical reactions only. However, this way of thinking can be generalized to other physical, chemical and biological systems as well.

Since there is a basic idea for proving the conjecture in [75] , I would like to follow it here. Motoyosi Sugita first defines the Boltzmann’s H-function for chemical reactions by

where

And if we write

where the equality holds true only when

Next, let us consider the derivative of H-function with respect to time along the course of time development. Then, Motoyosi Sugita considers the following:

Let us consider the chemical reaction equations such as Equation (5.21) for chemical reactions of Equation (6.5), for our case here. Associated with the choice of the reaction Equation (6.6), we can write the chemical reaction equations in the following:

where P and R mean production and reduction in the chemical reactions, respectively, and

where

and

respectively. On the other hand the affinity for each chemical reaction is defined by Equation (6.8). The chemical equilibrium values

Obviously this produces the law of mass action such as Equation (5.22) for each chemical reaction:

Substituting all into Equation (6.15) using the definition of chemical potentials Equation (6.4), finally Motoyosi Sugita ends up with

This is nothing but Equation (6.10), where

Theorem 1 (Boltzmann’s H-theorem).

Let us now prove the H-theorem. Following the similar argument of Motoyosi Sugita [75] , we find the following:

where

then the summand looks like

Since

The equality holds only for the equilibrium. Hence, the theorem is proved.

6.3. Motoyosi Sugita’s Idea for the Proof of the Conjecture

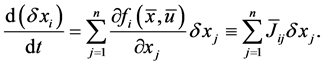

Motoyosi Sugita also considered more general case of the nonlinear processes, which may be represented by the following equations:

where x means a vector of

The stability of this system is investigated by the Lyapunov theorem. Denote by

where we have assumed that

Now the simplest Liapunov function is defined as

By differentiating this with respect to t, we obtain

If all real parts of the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix

Motoyosi Sugita applied this theorem to the Boltzmann’s H-function. And he proved the H-theorem is valid if the Lyapunov’s theorem holds.

Let us define the general Boltzmann’s H-function:

By differentiating the above equation, we immediately obtain

Motoyosi Sugita proved a mathematical theorem:

Theorem 2. If

where

Let us follow his proof, which is short. By assumption, we expand

Let us define

Using Equation (6.37), the Jacobian can be Taylor expanded in the following:

The remained procedure is to use Equation (6.35) and Equation (6.39) and to derive the right hand of Equation (6.34).

Hence, the theorem is proved. This is nothing more than the mean value theorem in the analysis for the analytic functions with many variables.

Using this theorem, Equation (6.33) turns out to be the following:

Now if all the real parts of

have the same sign. Therefore, we can obtain the following:

By differentiating Equation (6.33) with respect to t, we obtain

The second term in the above is always positive. Let us now substitute Equation (6.29) into the first term, we find

By definition

the Liapunov theorem is valid, all the real parts of eigenvalues of the Jacobian are negative. Hence, by multiplication, Equation (6.44) is always positive. From this fact, we obtain the following property of the H-function:

Theorem 3.

Let us define the entropy production

where k is the Boltzmann constant. Therefore, from Theorem 3 we immediately yield the following theorem:

Theorem 4.

This is nothing but the theorem of the minimum entropy production or the Prigogine’s principle of minimum entropy production [103] [104] .

In summary, this is the outline for the proof of the conjecture proposed by Motoyosi Sugita [75] . He tried again and again to prove this conjecture from various point of view. However, the general proof has never been done in his life time.

7. The Ideas of Motoyosi Sugita as a Specific Development of Lars Onsager’s Lifework

In 1951 Motoyosi Sugita first presented the theory of the maximum principle in transient phenomena such as those discussed in the previous section [38] . This paper was entitled as The Maximum Principle in the Transient Phenomena and the Application to Biology in Japanese. In this paper he first stated his vision and idea on the maximum principle in the transient phenomena. He argued the relationship between his idea of maximum principle and the existing old ideas such as the maximum-minimum principle in the Joule heat, the Boltzmann’s principle in the theory of gases, and the Onsager’s principle of the least dissipation of energy in the theory of irreversible processes [100] [101] . He finally applied his idea to many biological systems such as the thermodynamics of metabolism, the relationship between the maximum principle and the metabolism, the origins of life, and the dynamic equilibrium, the relaxation oscillations, the wholeness of life, etc.

In the succeeding paper in 1952, he further studied the maximum principle in relation to the Boltzmann’s H-theorem [40] . This paper was entitle as The Relationship between the Boltzmann’s H-Theorem and the Dissipation Function in Japanese. This paper is a really instructive one. As is discussed in the previous section, his theory preceded the times of Prigogine [103] [104] . So, in this section I would like to present his comparison between the Motoyosi Sugita’s theory and the Prigogine’s theory as well as Onsager’s theory [100] [101] and Katchalsky’s theory [105] [106] [108] . Fortunately for the Western people, these Japanese papers were summarized as the English versions [77] - [79] .

7.1. Relationship between the Boltzmann’s H-Function and the Irreversible Work

As is shown in the previous section, we have obtained the Boltzmann’s H-function, especially for the case of chemical reactions. Motoyosi Sugita first applied his idea of the virtual heat that has been discussed in the section II to the irreversible work of the system.

In order to see the difference between the method of Motoyosi Sugita and that of Ilya Prigogine more easily, let us change the notation of Motoyosi Sugita to adjust with that of Prigogine. Let us denote by i the internal system which is doing the irreversible work. Let us denote by e the external thermal reservoir, where we assume that no irreversible work has been done. By definition, we have

If the process is the broad quasi-static change (under the isothermal and isopressure), then we have

which is equivalent to

This is not satisfied when the irreversible work exists. In this case we have

which is the isothermal irreversible work. Or equivalently,

On the other hand, since the heat

Now we assume that there is no heat exchange otherwise, the total entropy of the system is given by

Since there is no irreversible work in the reservoir e,

This suggests that there exists the maximum principle in the transient phenomena in terms of the Boltzmann’s H-function. Hence, his conjecture is crucially important in the theory of non-equilibrium thermodynamics in the irreversible processes in the transient phenomena such as life. It also suggests the existence of the 4th law of thermodynamics.

On the other hand, Prigogine only showed that for the internal system

This means that the entropy of the internal system

However, as Motoyosi Sugita discussed long long ago, no matter what the irreversible process is taken into account, the following must be satisfied when the internal process is cyclic since the final state must come back to the initial state after one cycle:

On the other hand, as is shown in Section 2 [see Equation (2.19) and Equation (2.23)], we must have for the external reservoir after one cycle

This is the advantage of the Motoyosi Sugita’s concept of the virtual heat for the irreversible processes in the transient phenomena.

7.2. Relationship between the Boltzmann’s H-Function and the Dissipation Function

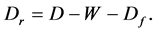

This argument can be generalized to the systems of flow dynamics or fluid dynamics. In this case there is matter exchange between the reservoir e and the system i. Let us denote by

This

or equivalently