Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation

Vol. 1 No. 2 (2013) , Article ID: 39916 , 9 pages DOI:10.4236/ojtr.2013.12005

Hydrotherapy treatment for patients with psoriatic arthritis—A qualitative study

![]()

1Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

2Samrehab, Sjukgymnastiken, Värnamo Sjukhus, Värnamo, Sweden; Email: maria.lindqvist@lj.se, gunvor.gard@med.lu.se

Copyright © 2013 Maria H. Lindqvist, Gunvor E. Gard. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 10 September 2013; revised 12 October 2013; accepted 19 October 2013

Keywords: Hydrotherapy; Psoriasis Arthritis; Rehabilitation; Qualitative Study

ABSTRACT

Purpose: To describe how patients living with psoriatic arthritis experience long-term hydrotherapy group treatment. Studies for this group of patients are lacking. Method: Qualitative interviews were conducted with ten informants after hydrotherapy treatment. The treatment included exercises for increased mobility, coordination, endurance, aerobic fitness, stretching and relaxation. The interviews were analysed with content analysis. Results: A theme “hydrotherapy—a multidimensional experience” and two categories emerged: situational factors and effects of hydrotherapy. The category “situational factors” comprised the subcategories: warm water, training factors and a competent instructor, and the category “effects of hydrotherapy” comprised the subcategories: psychological effects, improved physical capacity, social effects, changed pain experience and changes in work and participation in daily life. Conclusion: Positive effects of regular hydrotherapy in a group setting were shown in physical ability, energy, sleep, cognitive function, work and participation in daily life. The instructors had an important coaching role, which needs to be promoted.

1. INTRODUCTION

Psoriathic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthritis, often related to psoriasis. Nearly a third of patients with psoriasis also have inflammatory arthritis and enthesitis [1]. PsA has emerged as a specific disease independent of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [2]. It is a chronic disease with a wide range of impairments, limitations and restrictions [3]. The prevalence of psoriasis and psoriathic arthritis varies from 20 - 420 per 100,000 inhabitants across the world [4]. PsA can develop at any time but for the majority of people, it appears between the age of 30 and 50. Both genders are affected equally [5].

PsA has been grouped into five subtypes: distal interphalangeal, symmetric polyarthritis, assymetrical oligoarthritis and monoarthritis, spondylitis and arthritis mutilans [5]. There has been a controversy over the severity of peripheral PsA compared to RA. Except from the mutilans form (resorption of bone with dissolution of the joint), PsA was earlier found to be a milder disorder than RA. However, it has been suggested in recent reports that PsA can be as severe as RA. A recent study showed that function and quality of life scores are the same for both groups, but the joint damage in RA is significantly greater than in PsA after equivalent disease duration [6]. Another study showed that pain/disability and well-being were significantly lower in patients with PsA than in patients with RA [7]. Approximately 40% of patients with PsA may develop radiographic joint destruction [8]. It is common with axial disease in PsA. These patients have been said to experience severe pain and are therefore more hindered in their ability to function than patients with peripheral PsA [9]. Inflammatory spinal pain occurs in 40% of PsA-patients and radiologically defined sacroilitis in 78% of the patients [10,11]. Although there are similarities between axial PsA and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), important differences have been described [11]. PsA patients have reduced male preponderance, less overall disease severity, less severe sacroiliitis, less cervical involvement, and relative absence of ligamentous ossification compared to patients with AS [11]. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) showed significantly lower scores in PsA than in AS [12], and the correlation with external indicators of disease activity has shown contradictory results [12,13]. One study of physical functioning and disability in patients with PsA showed that 28% of the patients seemed resistant to become disabled over ten years but the remaining patients experienced permanent disability or moved between disability states [14]. There are three main groups of drug therapies which are used in treating PsA: Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Drugs (NSAID), Disease Modifying Anti Rheumatic Drugs (DMARD) and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alfa (TNF). Since 2002, there have been several advances in the therapeutics of spondyloarthropaties, particularly in AS and PsA due to the use of TNF blockers [15]. Enthesitis is characteristic for PsA patients [16]. Non-steroidal inflammatory medications, physiotherapy and steroid injections are recommended as being potentially effective treatments. Despite this, case series or controlled trials with Spondyloarthritis (SpA) patients treated with these could not be found [16].

Physical Therapy/Hydrotherapy

Physical therapy is as an essential part of the management of PsA. Swimming and group training is recommended especially for patients with axial disease [17] and stretching of muscles around the affected joints.

Hydrotherapy is defined as supervised structured exercises of specific extremities and joints in warm water. Immersion in warm water reduces the load on painful joints according to the law of Archimedes (287 BC) and allows exercise against water resistance. Thanks to the effects of temperature and pressure on nerve endings and muscle relaxation, pain may be relieved, which may facilitate mobilizing and strengthening of affected joints and muscles [18-20]. People with RA and PsA highly value hydrotherapy. Few randomized studies have studied the effect of hydrotherapy [21-23] or compared the benefits of hydrotherapy with exercises [24,25]. One recent study showed that patients with RA were more likely to report improved well-being after a hydrotherapy treatment program compared to exercise treatment [24]. Also in a randomized trial with people with AS, hydrotherapy had better short-term improvement in cervical rotation than exercise alone [25]. Within rheumatology, patients consider that it is important both with evaluations of treatments which can increase well-being and reduce fatigue and with studies of physical outcomes such as pain and disability [26,27]. Hydrotherapy may increase well-being, physical functioning and reduce fatigue among patients with rheumatologic diseases. So far, no scientific study of the effects of hydrotherapy for patients with PsA has been performed.

The aim of this study was to describe how patients living with PsA experience hydrotherapy.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

A hydrotherapy group led by physiotherapists, physiotherapy assistants or leaders in a patient organization was contacted to find informants. They recruited informants at three different hospitals. Information was also given by a leaflet. The informants were consecutively included in the study as soon as they agreed to participate.

Ten informants participated in the study, eight women and two men. The inclusion criteria were: being eighteen years or older, having a diagnosed PsA for at least one year, having the capacity to understand and speak Swedish, having participated in 10 or more hydrotherapy sessions, the latest treatment period not more than 3 months prior to the interview. The mean age of the participants was 55 years, ranging from 33 to 70 years. Their mean duration of illness was 10 years, ranging from 2 to 27 years. They had participated in hydrotherapy for an average of 9 years ranging from 0.5 to 27 years. Two were receiving social benefits for part-time sick leave and three were receiving full time sick leave or pension. Two were working and three were retired. Six were married and four lived alone or with their children.

2.2. Qualitative Interview Study

A qualitative interview study was performed. Qualitative studies are performed to increase the understanding of patients’ experiences, thoughts and actions for example when living with chronic diseases [28] and to describe experiences of a phenomenon [29,30]. To use an interview guide is recommended [29] and we used a semi-structured interview guide which covered the following fields: hydrotherapy as an exercise form, the effects of hydrotherapy on bodily functioning, activity and participation. A pilot interview was conducted before the study to check the procedure and complete the interview guide. Each interview started with an open question about the experience of hydrotherapy: can you tell me about your experience of hydrotherapy? The interviews were conducted during a period of 6-months. The interviewer was not involved in the informants’ treatment. Before the interview, the aim of the study was presented and the informants had the opportunity to ask questions. They were informed that their participation was optional and that they could end their participation at any time. They were also assured of confidentiality and signed a letter of informed consent [29].

The interviews took place in a setting chosen by the informants. Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim by the author. Each interview lasted between 35 and 60 minutes. This project has been approved by the central ethical review board in Linköping, number M238-09.

2.3. Data Analysis

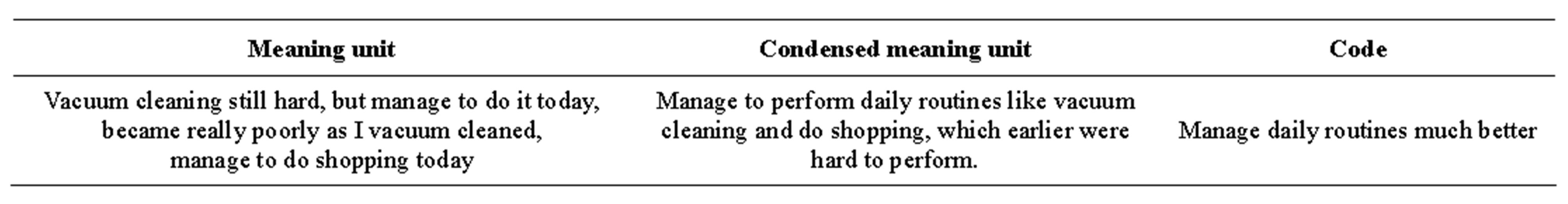

The data analysis was performed with content analysis following the steps recommended by Graneheim and Lundman [31]. The data was reviewed multiple times in order to assure a complete and thorough understanding of the collected data. The text was divided into meaning units which were condensed and abstracted and labeled with codes. Examples of meaning units, condensed meaning units and codes are shown in Table 1. The whole text was considered when condensing and labeling meaning units with codes. The various codes were compared concerning differences and similarities and sorted into two categories with eight sub-categories constituting the manifest content. The categories were discussed by the authors. A process of reflection and discussion resulted in an agreement about how to sort the codes. Finally the underlying meaning, the latent content, of the categories was formulated into a theme.

2.4. Hydrotherapy Program

The hydrotherapy group was led by physiotherapists, physiotherapy assistants or leaders in a patient organization. Each hydrotherapy session lasted 45 - 50 min (at 35˚C) and was conducted in groups of 5 - 17 patients. The informants participated once or twice a week. The program included exercises for increased mobility, coordination, endurance, aerobic fitness, stretching and relaxation. It comprised exercises for all parts of the body. The pace of the exercises was guided by music.

3. RESULTS

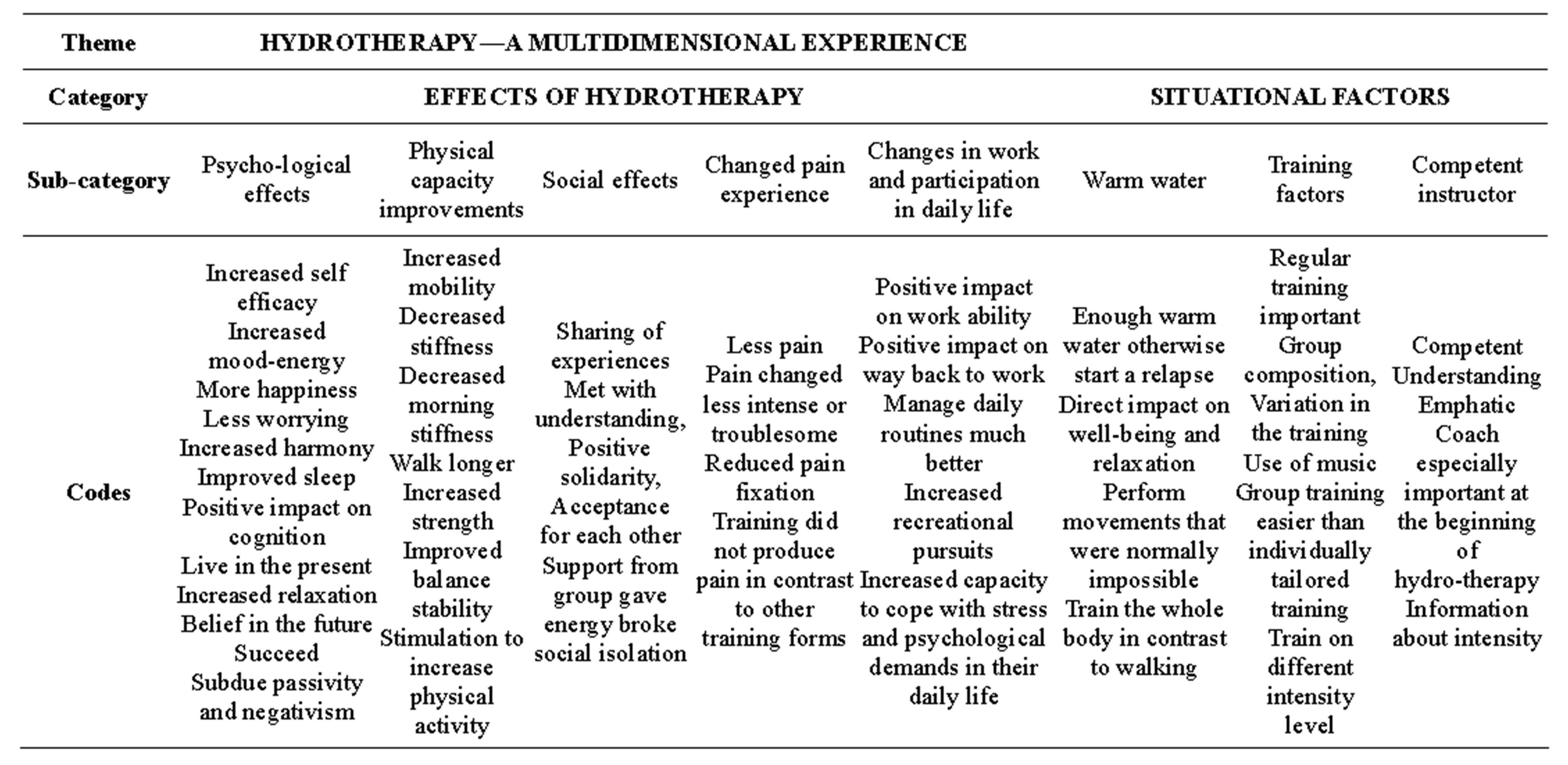

A theme “hydrotherapy—a multidimensional experience” and two categories emerged; situational factors and effects of hydrotherapy. The category “situational factors” comprised the subcategories: warm water, training factors and a competent coach and the category “effects of hydrotherapy” the subcategories: psychological effects, physical capacity improvements, social effects, changed pain experience and changes in work and participation in daily life Table 2.

3.1. Situational Factors of Hydrotherapy

3.1.1. Warm Water

All informants, but one described that warm water or enough warm water was important “It’s very important, I prefer being in the warm pool which is 34˚C - 36˚C.

Table 1. Description of the content analysis process.

Table 2. Theme, the two main categories, subcategories and codes.

When it’s cold, then I also have contractions in the thoracic spine. When it’s getting cold you feel your muscles tighten and then… I get pain” (Inf. 3). The water also seemed to have a direct impact on well-being and relaxation and enabled the informants to perform movements that were normally impossible more easily and with less pain. The informants could train the whole body in the water.

3.1.2. Training Factors

The hydrotherapy was experienced to be improved by different training factors, such as regular training, the group composition, variation in the training and the use of music. Regular training was important to get positive treatment effects. Without regular training the positive training effects gradually disappeared, with increased tiredness and reduced energy for work and/or leisure activities as a result. It took two to three sessions before any effects of the training could be experienced “I got a break from the hydrotherapy due to an operation on my hands, I felt after a while that my condition had become worse, it will take time to catch up again and achieve the same level I had before I took the break” (Inf. 1).

The group composition and homogeneity of the group in age and physical capacity was experienced to be important, together with the opportunity to train on different intensity levels. It was also easier to perform the exercises when doing them in a group. Variation in hydrotherapy exercises and the use of music in the training were experienced as important. It increased the joy and motivation and also helped the informants to perform the movements in the correct way.

3.1.3. A Competent Instructor

Most informants experienced that having a competent instructor was very important. The instructor should be competent, understanding and empathic. “Feeling safe with the instructors… they have to be capable” (Inf. 7).

The instructions from the coach were especially important at the beginning of the hydrotherapy session since the patients were afraid of performing the exercises in an incorrect manner. Some informants had experienced setbacks at the beginning of their training and found it difficult to choose the intensity of the training. Most informants got enough information from the instructor about how to tailor the training to themselves.

3.2. Effects of Hydrotherapy

Different effects of the hydrotherapy treatment were experienced such as psychological effects, improved physical capacity, social effects and a positively changed pain experience.

3.2.1. Psychological Effects

Psychological effects were experienced as an important subcategory, including experiences of increased selfefficacy, increased mood-energy, and increased relaxation. Hydrotherapy was experienced to increase the informants’ self-efficacy, self-confidence and beliefs in the future, which allowed them to try new tasks. It helped them to succeed and to subdue passivity and negativism. “I have much more belief in that I will not end up in a wheelchair and feel that I will manage more and more” (Inf. 4).

Improved mood was experienced as more happiness, less worrying, experiences of doing something fun, increased harmony, feelings of freedom and contentment about positive achievements. “It is important for me to be able to plan and do something I can manage, I feel fine to be able to do something that I find fun, and in that way I also feel better. In other words if I can cope with pain I am happier” (Inf. 8). Some experienced an increase in energy already the same day, others the day after a session, with positive impact on many aspects in their lives. Some informants experienced a positive tiredness directly after training and the increased energy was experienced after one day. Some experienced improved sleep and relaxation which had positive impact on emotions and cognitions and increased their ability to live in the present moment.

3.2.2. Improved Physical Capacity

Improved physical capacity was experienced. Almost all informants experienced increased mobility and decreased stiffness in general or decreased morning stiffness which for some enabled them to take a greater part in leisure activities and for some the ability to walk longer. “I feel less pain because I can control my body in another way when I walk. The body becomes limp not trained in the pool, I become stiff and then I can’t get my body to follow when I walk. I walk longer distances today” (Inf. 2). Others described increased strength or the possibility to retain strength. Improved physical fitness, improved balance, stability and a stimulation to increase physical activity were other important areas of improvement.

3.2.3. Social Effects

The social effects were very important for the majority of the informants. The sharing of experiences with others living with PsA or other rheumatic deceases and to be met with understanding were two important factors. “Meet others who are in the same situation is important. I can tell my husband that I feel so or so but he can’t grasp it anyway, but if I tell someone who suffer from the same condition they understand what it is and that I think is very important” (Inf. 5). The group helped the informants not to feel alone in their situation. The group also created a positive solidarity and acceptance for each other. To joke and laugh were considered very positive experiences. The support from the group gave energy and broke social isolation.

3.2.4. Positively Changed Pain Experience

Most informants experienced less pain after the training and/or that their pain changed into being less intense or troublesome. The training also reduced their pain fixation. The hydrotherapy training did not produce pain, in contrast to other forms of training for example strength training. “I think that I should have felt mentally and physically worse… and probably have been more closed up in myself with the pain” (Inf. 9).

3.2.5. Changes in Work and Participation in Daily Life

Changes in work and participation in daily life were also experienced. Half of the group experienced that hydrotherapy had a positive impact on their work ability; or on their prospects of finding their way back to work. An increased participation in daily life and in recreational pursuits was experienced. “My body gets stronger, it makes me manage more, it has had an impact on my whole life, actually, the training in the pool. I improve my mobility so I can take part in life in another way” (Inf. 2). Some informants experienced an increased capacity to cope with stress and psychological demands in their daily life. Some informants felt that they managed their daily routines with more ease and others that they possessed the strength and energy to do other things.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, no earlier study has explored how patients living with (PsA) experience hydrotherapy. In the present study, hydrotherapy was experienced as a multidimensional experience, influenced by factors in the treatment situation as well as by different effects. Situational factors experienced were warm water, training factors and a competent instructor. Almost all the informants stressed the importance of warm water, approximately 35˚C. The warm water had a direct impact on wellbeing and relaxation, which only to some extent has been confirmed earlier [18,32]. A 50% increase in cardiac output has been found at a water temperature of 35˚C (30). This, 35˚C, may be the most favourable temperature for hydrotherapy for patients with PsA and stresses the importance of facilitating pools with warm water for this group. Regular training was considered as very important. An earlier study of hydrotherapy for patients with RA has shown that the energy level can be maintained three months after the end of hydrotherapy treatment [22]. Regarding muscle strength, one study showed that positive effects of hydrotherapy may last for about two months [32], while another study showed less positive results [22]. Flexibility was maintained in one study at a three month follow up [33]. It appears that this group of patients benefit from continuous training. In addition, they required two to three sessions of training before any positive effects could be noticed. Geytenbeck found that the length of hydrotherapy training periods in different studies ranged from four days to 36 weeks with an average of 10 weeks [34]. The frequency of hydrotherapy training ranged from daily to weekly with an average of (2 - 3) times per week. She also states that researchers do not recommend any specific frequency or duration. Stenström and Minor, who have studied different forms of exercises for patients with RA state that strength training, is recommended be performed 2 to 3 times per week [35]. Other studies of duration of strength training state that eight to ten weeks training provide positive effects [36]. The duration of hydrotherapy for patients with rheumatic diseases needs to be further studied.

In this study some informants experienced that it was important to train in groups at tailored intensity training levels to be satisfactory. Too intense training sessions may cause setbacks and increase pain for some patients. That group training can be more effective than individual training has been confirmed in earlier studies [37].

A majority of the informants in this study experienced that music made the training more fun and inspiring and that it helped them in performing the movements. This has only to some extent been notified earlier [38]. An instrument, the Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2, can help instructors to select music that has a motivational effect. Karageorghis et al. state that motivational music might increase exercise enjoyment [38] and decrease pain and depression and promote individual empowerment [39] which is of great importance for these patients. Also competence development for instructors may imply more motivating training sessions and a positive difference in treatment effects. Concerning coaching, the informants stressed competence, understanding and empathy. The role as a coach demands a significant amount of knowledge and commitment. During this study the instructors had different qualifications. We consider it important that the instructors can update their competence regularly. The instructor’s motivation and engagement is important for positive training effects [40] and to strengthen patients’ vitality [40]. The importance of the training instructor needs to be further explored [41]. In addition, the informants found it difficult to know at what intensity they should begin to exercise. It has been recommended to begin with very light weights to avoid setbacks in training for patients with RA [42], but studies, comparing frequency and intensity of strength training are lacking [42]. In clinical practice it is well known that patients with PsA often have more pain after training than AS patients. This study stresses the importance of further studies about the dosage of strength training for PsA patients.

Different effects of hydrotherapy were noted. Psychological effects such as increased self-efficacy, moodenergy, and relaxation were experienced, which to some extent have been confirmed by earlier research on RA patients [21,22,33,34]. Positive mood enhances perceived self-efficacy and low mood diminishes it [43]. Hydrotherapy was also experienced as beneficial as the informants succeed in doing something they managed to do. Some informants experienced better sleep or required less sleep, which is new knowledge for this patient group. It has earlier been shown that total sleep time may increase and total nap time may decrease among patients with fibromyalgia who participated in hydrotherapy. [44]. Many patients with RA and PsA are very tired, which may be due to suffering from disturbed sleeping patterns. This needs to be further researched, since patients identify fatigue as an important outcome, and lack of sleep can be related to that [26].

The patients in this study got increased energy from the hydrotherapy training, influencing all aspects of their lives. This is very important since fatigue is as severe and frequent as pain among PsA patients [45,46]. Some informants stated that the relaxation they experienced had a positive influence on their cognitive capacity. It is well known from modern pain research that long lasting pain has an influence on the cognitive capacity [47,48]. Hydrotherapy has been shown to have effect on cognitive function in patients with fibromyalgia [49]. Further research of patients with PsA would be valuable. In this study the informants experienced physical capacity improvements which included increased joint mobility, reduced stiffness, increased strength, improved balance, and/or increased walking distance. The physical effect of increased joint mobility [25,50] has to some extent been confirmed on patients with RA and AS and decreased stiffness on patients with AS [25]. Increased strength has been confirmed on patients with RA [22,23] Improved balance [51] and an increased physical activity level have to some extent been confirmed by earlier studies on patients with RA [23]. Hydrotherapy as a measure to increase physical activity is very important from a health perspective since patients with RA and patients with other rheumatic diseases have an over representation of cardiovascular diseases [52].

The informants in this study experienced that group training increased their energy and broke their pattern of social isolation. Social support and its impact on physical health has been studied by Wallstone et al. [53], showing that there is a link between social support and physical health. It is important to belong to a particular group, it can predict improved health for women and fewer symptoms for men [54]. This needs to be further investigated in patients coping with rheumatic diseases. In other studies on patients with RA, social functioning and social support from the family and friends have been focused. Improved social functioning has been shown after three months of intensive hydrotherapy training [22]. In this study most, but not all, informants experienced less pain after hydrotherapy. As previously described, more pain could possibly be due to too much intense training [42]. Hydrotherapy helped some informants in breaking pain fixation which is important for self-management [43]. Less pain after hydrotherapy treatment has been confirmed earlier [25,50] from patients with RA and AS.

Half of the group in this study described that hydrotherapy had a positive impact on their work capacity and/or return to work. No quantitative study has shown any positive effect on work capacity among patients with RA, attending hydrotherapy [33], probably due to a too short training period [33]. A long-term study of the effects of hydrotherapy on work ability and participation in daily life can be recommended as also participation was experienced to be improved in the present study. An earlier study has shown that 51 of 91 (53%) ICF-categories concerning activity and participation were affected by PsA in at least 30% of participants [3]. A similar study of patients with RA showed that 16 of 48 (33%) categories were affected. Increased participation in daily life in the area of physical capacity has been confirmed by earlier studies on RA patients [22,33].

5. DISCUSSION OF METHOD

All informants were given the option of receiving a copy of the transcribed interview and had the opportunity to add information, but no one did. All data was also transcribed by the same person, the first author, these actions may have implied credible data [55]. The quotations were translated by a professional translator. Even though a consecutive selection was used, a variation of age and various experiences were achieved. We had both men and women, of various ages and with different experiences in our study which may have increased the credibility of the study [31]. A limitation was that only one informant had his/her origin from outside the Nordic countries and that only two men accepted to participate. The participating ten informants were the only available informants fulfilling the inclusion criteria in the region. However, it may be so that if the researcher, as in our study, is well acquainted with the research method and have thorough knowledge about the field, also a not so large number of informants can be enough to give a rich material [56]. In qualitative studies when using content analysis the pre understanding of the author always needs to be reflected upon. In this study a co-author who does not work with rheumatology patients assisted in categorizing the data which lends credibility to the study [31]. The transferability of a qualitative study can be facilitated with a clear description of the aim and context, selection of informants, data collection and process of analysis [31]. As authors we have considered these factors and mean that the results can be transferred to hydrotherapy treatment for patients with PsA in a similar hydrotherapy context. We recommend quantitative studies of hydrotherapy with the use of the psoriatic arthritis quality of life (PsAQoL) instrument, (which is the only reliable and valid instrument so far for this specific patient group) and to study [57] if quality of life of this patient group may be improved. There is also a need of further development of physical outcome measures for this specific patient group.

6. CONCLUSION

Positive effects of hydrotherapy were experienced on physical function, energy, sleep, cognitive function, ability to work and participation in daily life. Further controlled studies are needed. The hydrotherapy instructors had an important coaching role, which needs to be promoted.

REFERENCES

- Mease, P.J., Gladman, D.D., Kreuger, G.G. and Taylor, W.J. (2005) Prologue: Group for research and assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 64, 1-2.

- O’Neill, T. and Silman, A.J. (1994) Psoriatic arthritis. Historical background and epidemiology. Baillière’s Clinical Rheumatology, 8, 245-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0950-3579(94)80017-0

- Taylor, W.J., Gladman, D.D., Mease, P.J., Adebajo, A., Nash, P.J. and Feletar, M. (2009) The impact of psoriatic arthritis according to the international classification of functional health and disability (ICF). ACR/ARHD Annual Scientific Meeting, Philadelphia, 17-19 October 2009.

- Alamanos, Y., Voulgari, P.V. and Drosos, A.A. (2008) Incidence and prevalence of psoriatic arthritis: A systematic review. Journal of Rheumatology, 35, 1354-1358.

- Dhir, V. and Aggarwal, A. (2012) Psoriatic arthritis: A critical review. Clinical Review in Allergy & Immunology, 44, 141-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12016-012-8302-6

- Sokoll, K.B. and Helliwell, P.S. (2001) Comparison of disability and quality of life in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology, 28, 1842-1846.

- Mustur, D. and Vujasinovic-Stupar, N. (2007) The impact of physical therapy on the quality of life of patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. Medicinski Pregled, 60, 241-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.2298/MPNS0706241M

- Mease, P. and Goffe, B.S. (2005) Diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 52, 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2004.06.013

- Zink, A., Thiele, K., Huscher, D., Listing, J., Sieper, J., Krause, A., et al. (2006) Healthcare and burden of disease in psoriatic arthritis. A comparison with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Journal of Rheumatology, 33, 86-90.

- Battistone, M.J., Manaster, B.J., Reda, D.J. and Clegg, D.O. (1999) The prevalence of sacroilitis in psoriatic arthritis: New perspectives from a large, multicenter cohort. A department of veterans affairs cooperative study. Skeletal Radiology, 28, 196-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002560050500

- Nash, P. (2006) Therapies for axial disease in psoriatic arthritis. A systematic review. Journal of Rheumatology, 33, 1431-1434.

- Taylor, W.J. and Harrison, A.A. (2004) Could the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) be a valid measure of disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis? Arthritis & Rheumatism, 51, 311-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.20421

- Eder, L., Chandran, V., Shen, H., Cook, R.J. and Gladman, D.D. (2010) Is ASDAS better than BASDAI as a measure of disease activity in axial psoriatic arthritis? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 69, 2160-2164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.129726

- Husted, J.A., Tom, B.D., Farewell, V.T., Schentag, C.T. and Gladman, D.D. (2005) Description and prediction of physical functional disability in psoriatic arthritis: A longitudinal analysis using a Markov model approach. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 53, 404-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.21177

- Yan, L., Cortinovis, D. and Stone, M.A. (2004) Recent advances in the treatment of the spondyloarthropathies. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 16, 357-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.bor.0000129719.21563.35

- Ritchlin, C.T. (2006) Therapies for psoriatic enthesopathy. A systematic review. Journal of Rheumatology, 33, 1435- 1438.

- Klareskog, L., Saxne, T. and Enman, Y. (2005) Reumatologi. Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- Melzack, R. and Wall, P.D. (1965) Pain mechanism: A new theory. Science, 150, 971-979. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3699.971

- Kjellgren, A., Sundequist, U., Norlander, T. and Archer, T. (2001) Effects of flotation-REST on muscle tension pain. Pain Research & Management, 6, 181-189.

- Bender, T., Karagulle, Z., Balint, G.P., Gutenbrunner, C., Balint, P.V. and Sukenik, S. (2005) Hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, and spa treatment in pain management. Rheumatology International, 25, 220-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00296-004-0487-4

- Athern, M., Nicholls, E., Simionato, E., Clark, M. and Bond, M. (1995) Clinical and psychological effects of hydrotherapy in rheumatic diseases. Clinical Rehabilitation, 9, 204-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/026921559500900305

- Bilberg, A., Ahlmen, M. and Mannerkorpi, K. (2005) Moderately intensive exercise in a temperate pool for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled study. Rheumatology (Oxford), 44, 502-508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh528

- Stenström, C.H., Lindell, B., Swanberg, B., Swanberg, P., Harms-Ringdahl, K. and Nordemar, R. (1991) Intensive dynamic training in water for rheumatoid arthritis functional class II. A long term study of effects. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumathology, 20, 358-365. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/03009749109096812

- Eversden, L., Maggs, F., Nightingale, P. and Jobanputra, P. (2007) A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of hydrotherapy and land exercises on overall well being and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-8-23

- Helliwell, P.S., Abbott, C.A. and Chamberlain, M.A. (1996) A randomised trial of three different physiotherapy regimes in ankylosing spondylitis. Physiotherapy, 82, 85-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)66956-8

- Carr, A., Hewlett, S., Hughes, R., Mitchell, H., Ryan, S. and Carr, M. (2003) Rheumatology outcomes: The patient’s perspective. Journal of Rheumatology, 30, 880- 883.

- Her, M. and Kavanaugh, A. (2012) Patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 24, 327-334.

- Charmaz, K. (1990) Discovering chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science & Medicine, 30, 1161- 1172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90256-R

- Kvale, S. and Torhell, S.-E. (1997) Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- Gibson, B.E. and Martin, D.K. (2003) Qualitative research and evidence-based physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy, 89, 350-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60027-2

- Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Moberg, K.U. (2000) Lugn och beröring: Oxytocinets läkande verkan i kroppen. Natur och Kultur i Samarbete med Axelsons Gymnastiska Institut, Stockholm.

- Hall, J., Skevington, S.M., Maddison, P.J. and Chapman, K. (1996) A randomized and controlled trial of hydrotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research, 9, 206-215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199606)9:3<206::AID-ANR1790090309>3.0.CO;2-J

- Geytenbeek, J. (2002) Evidence for effective hydrotherapy. Physiotherapy, 88, 514-529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60134-4

- Stenstrom, C.H. and Minor, M.A. (2003) Evidence for the benefit of aerobic and strengthening exercise in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 49, 428-434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.11051

- Pollock, M.L. and Vincent, K.R. (1996) Resistance training for Health. The President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports Research Digest, Series 2, No. 8.

- Martin, J.E. and Dubbert, P.M. (1982) Exercise apllication and promotion in behavioral medicine: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 1004-1017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.50.6.1004

- Karageorghis, C.I., Priest, D.L., Terry, P.C., Chatzisarantis, N.L. and Lane, A.M. (2006) Redesign and initial validation of an instrument to assess the motivational quailties of music in exercise: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, 899-909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640410500298107

- Siedliecki, S.L. and Good, M. (2006) Effect of music on power, pain, depression and disability. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 54, 553-562. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03860.x

- Revstedt, P. (2002) Motivationsarbete. 3 Edition, Liber Utbildning AB, Falköping.

- SBU. (2007) Metoder för att främja fysisk aktivitet. 111- 113.

- Stenstrom, C.H. and Swärdh, E. (2006) Rätt doserad träning ger positiva effekter vid reumatoid artrit. Fysioterapi, 4, 40-46.

- Bandura, A. (1994) Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran, V.S. Ed., Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, Academic Press, New York, 71-81.

- Vitorino, D.F., Carvalho, L.B. and Prado, G.F. (2006) Hydrotherapy and conventional physiotherapy improve total sleep time and quality of life of fibromyalgia patients: Randomized clinical trial. Sleep Medicine, 7, 293- 296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2005.09.002

- Wolfe, F., Hawley, D.J. and Wilson. K. (1996) The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. The Journal of Rheumatology, 23, 1407-1417.

- Minnock, P. and Bresnihan, B. (2004) Pain outcome and fatigue levels reported by women with esablished rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 50, 1171-1198.

- Norrbrink, C. and Lundeberg, T. (2010) Om smärta ur ett fysiologiskt perspectiv. Studentlitteratur AB, Lund, 54- 55.

- Lee, D.M., Pendleton, N., Tajar, A., O’Neill, T.W., O’Connor, D.B., Bartfai, G., et al. (2010) Chronic widespread pain is associated with slower cognitive processing speed in middle-aged and older European men. Pain, 151, 30-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.024

- Munguia-Izquierdo, D. and Legaz-Arrese, A. (2007) Exercise in warm water decreases pain and improves cognitive function in middle-aged women with fibromyalgia. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 25, 823-830.

- Templeton, M.S., Booth, D.L. and O’Kelly, W.D. (1996) Effects of aquatic therapy on joint flexibility and functional ability in subjects with rheumatic disease. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 23, 376-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.1996.23.6.376

- Suomi, R. and Koceja, D.M. (2000) Postural sway characteristics in women with lower extremity arthritis before and after aquatic exercise intervention. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81, 780-785.

- Sattar, N., McCarey, D.W., Capell, H. and McInnes. I.B. (2003) Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation, 108, 2957-2963. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05

- Wallstone, B.S., Alagna, S.W., McEvoy., De Vellis, R. and De Vellis, R. (1983) Social support and physical health: The importance of belonging. Journal of American College Health Association, 53, 276-284.

- Hale, C.J., Hannum, J.W. and Espelage, D.L. (2005) Social support and physical health: The importance of belonging. Journal of American College Health, 53, 276- 284. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.6.276-284

- Poland, B.D. (1995) Transcription quality as an aspect of rigor in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 1, 290- 310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107780049500100302

- Malterud, K. (1998) Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning. Studentlitteratur, Lund.

- McKenna, S.P., Doward, L.C., Whalley, D., Tennant, A., Emery, P. and Veale, D.J. (2004) Development of the PsAQoL: A quality of life instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 63, 162-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.2003.006296