Open Journal of Business and Management

Vol. 1 No. 3 (2013) , Article ID: 38960 , 18 pages DOI:10.4236/ojbm.2013.13011

Collaborative Corporate Strategy Research Programmes (C.C.S.R.P.) a Conceptual Integrative Strategic Framework for a Practical Research Agenda

1Northampton Business School, University of Northampton, Northampton, UK

2Henley Business School, University of Reading, Reading, UK

Email: *nadeem.khan@northampton.ac.uk

Copyright © 2013 Nadeem Khan, Nada Korac-Kakabadse. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received August 16, revised October 1, accepted October 14, 2013

Keywords: Corporate Strategy Research Programme; Strategy; Collaborative Research; Holistic Framework

ABSTRACT

Researchers have been studying the strategies and the strategic behaviours of corporate firms for more than sixty years. Within the generated literature, contrasting philosophical positions and alternative assumptions underpin contested differences in strategic definition. Although this has created a rich tapestry of theoretical frameworks and schools of thought, the variety has further contributed to making practical research narrowly focused, complex and increasingly fragmented. In this paper we review the scholarly literature to establish an integrative definition of strategy and conceptualise our holistic novel corporate strategy research framework. We call this the Collaborative Corporate Strategy Research Programme (C.C.S.R.P.) which serves as a useful organising framework for corporate strategy research within the institution. This may further enable better structured and more meaningful longer term collaborative research between different institutions. Where corporation has outgrown government and operates across diverse markets, the research agenda has to innovatively adapt to better inform its stakeholders.

1. Introduction

During the last sixty years, scholarly contributions to the corporate strategy literature have engaged the term strategy in different ways [1-3] to predict and explain the established firm’s behaviour within environments. The firm itself has developed an array of constructs which include behavioural, social, transactional, agency, resource, evolutionary, ecological, and innovative conceptualisations. There remains a lack of consensus to both the theory of the firm [4: p. 5] and strategy definition [5]. Consequentially, the specialisations become compounded as antecedent conditions, assumptions to, and characteristics of corporate strategic analytical frameworks. The more traditional approaches such as Long Range Planning; Structure Conduct Performance; Strategic Conflict; Resource Based View; Knowledge Based View and Dynamic Capabilities have been complemented by ecological and evolutionary frameworks in recent years. Further, the origins of assumptions that underpin each framework emerge from the divergent branches of economic, organisational, psychological and biological sciences. The growth of research has enabled comparison within each school of thought. However, the universal purpose and inter-school application of a strategic definition/framework remains elusive in an increasingly interconnected world. Consequentially, holistic research opportunities within the field are limited.

Our paper critically reviews the breadth of contributions to strategy definition and corporate strategy frameworks during the last sixty years. We integrate the specialisations into a holistic conceptual framework more suited to comparative research of the twenty-first century corporation [6] within dynamic markets. Traditional geographic boundaries have to be transcended [7] to reflect the complex multi-layered internal (board; executive; division) and external (industry; government; regional or cultural) influential effects.

2. Mapping the Strategy Landscape

We present a review of the definition of strategy within the literature on corporate strategy from three perspectives: 2.1) the historical development into business terminology; 2.2) within scholarly theoretical debates on definition; and 2.3) contextualised within empirically supported published papers in relevant journals.

2.1. Strategy: A Historical Perspective

The language of strategy has military origins [8] which we can trace back to General Tzu’s classic Chinese writings [9]. He discusses positioning and planning in his famous work, The Art of War. Over the years, scholars have interpreted the wisdom and teachings of this historical eastern literature [10,11] and applied it to a variety of contexts [12-14] including twentieth century business strategy [15,16] The application to modern corporate case studies [17] demonstrates harmony between ancient eastern warfare strategies and modern western corporate firm behaviour. In this regard, the origins of strategy [18] may more specifically relate to human behaviour, as firstly to survive and then to influence. Further, Giles [19: p. 23] interpreted text identifies “moral law or harmony” as one of the factors that a General must be familiar with. In a non military context, morality [20] guides human behaviour and “harmony” is a sweet melodious sound [21: p. 455]. Therefore, in a business context, we may guide strategy by our ethics or may liken it to music, where a variety of instruments combine to create a unique fit at a point in time.

Providing a lexical definition of strategy Sykes, Hawker [21: p 1052; 22: p. 691] and Soanes [23: p 749] strictly adhere to the etymological derivation from the Greek word strategia which means “generalship”. In comparison, the thesaurus offers a wider compendium of meanings, including: “the use of skilful planning to secure one’s advantage in business; or a plan or design to achieve one’s aims” [24: p 1644]. Here, the terminology “plan” implies the intension to do as a one-time static activity. More recently, Waite et al. [25: p 804] use the word “action”, which implies a progressive closeness to reality and suggests doing as an on-going continuous activity.

In a business context, the firm [26,27] is exposed to competitive pressures as it attempts to satisfy demand. A dilemma exists in defining strategy (plan or action) within the dimensions of time and space between firm and marketplace. In an attempt to bridge this gap, the classic Andrew’s [28] definition refers to a pattern of decisions where “corporate strategy” focuses on firm resources and competence to achieve advantage based on a unique posture, derived from internal strengths/weaknesses and external opportunities/threats. This early conceptual strategy design model integrates causal features and implies interdependence and interrelatedness [29]. It distinguishes between corporate and business strategy and most importantly, explicitly incorporates the importance of stakeholders [30] within its definition.

It may be that the early intellectual route into business terminology may have its origins in Economic Organisation and Bureaucracy studies [31]. Nevertheless, the historical context and business definitions suggest strategy to be a high level activity which seeks some kind of advantage. Further, Andrews’ [28] definition refers to strategy within a unique situational context where posture through patterns implies time significance.

The main theme within these historical perspectives suggests that strategy is a high level (Corporate) plan or action to achieve advantage for stakeholders.

2.2. Strategy: A Theoretical Perspective

Strategy has a rich and diverse range of definitions by prominent thinkers over many years. Scholars have explored strategy and structure [32], long-range planning [33,34] strategy as patterns [2,35], strategy as practice [36], taxonomic classifications [8,37] strategy as decision making [38,39] at a competitive level [40,41], a corporate level [42,43] and from beyond the field [44-46]. The diversity of definition in itself implies either that all scholars disagree with each other [47] or that diversity is due to firm, context, time and leadership specific traits that cause a lack of commonly accepted, universal definitions [5]. This warrants a more in-depth review of the contrasting debates.

Mintzberg [2: p. 935] presents results of a long term study in which he argues that the works of Chandler [32] and Von Neumann and Morgenstern [48] use an “incomplete definition of strategy” for research and firm purposes. Mintzberg [2: p. 935] suggests that the functional definition of strategy as a plan, results in “abstract normative conclusions” as the plan is made in advance of the specific decisions that apply to it, requiring predictability. For research purposes, Mintzberg [2] prefers a wider definition of “a pattern in a stream of decisions” which evolves Andrews’ [28] definition. Strategy can be intended (forward looking) and realised (backward looking). This wider definition argues that strategy may become known as a result of actions [49], which may not necessarily have been intended. Strategy emerges as managers take decisions and it is formulated, formed and realised rather than just formulated. Mintzberg enhances his 1978 definition (plan, pattern) to five elements by 1987 with the addition of position, perspective and ploy [50]. The evolution from “decisions” [2] to “actions” [49] implies closer alignment to reality in contrast to long range planning. Mintzberg et al. [51] demonstrate self validation, as they state, “Strategy is a pattern, that is, consistency in behaviour over time”.

In contrast, Newman and Logun’s [52] definition suggests that strategy is consciously and purposefully formulated in advance of intended actions. As such, the implementation of strategy is disengaged from the planning of it and predictability is assumed. In this regard, the introduction of long term objectives [32] and understanding of the competitive domain [53] support Newman and Logan’s [52] definition. Andrews [28] extends this further by including all stakeholders. This group of scholars agree with the long range planning view and have defended it for the last fifty years. Chandler and Andrews intellectual base derives from Harvard, whereas Ansoff from Carnegie School. Ansoff [54] argues that prescriptive formulation and descriptive implementation cannot be combined in definition. The problem with Mintzberg’s [55] definition, according to Ansoff [54] is that the concept is prescriptive as strategy needs to be formulated in advance, yet emergent and realised outcomes that need to be observed for strategy to form are descriptive. In contrast, Mintzberg et al. [51], Rumelt et al. [31] and Schendel [56] prefer a definition that does not distinguish between formation and implementation. Mintzberg [57] argues that the linear planning definition distances strategy from reality, strategic thinking cannot be separated from operational management [58] and data analysis cannot produce novel strategies. Strategy to the latter group of scholars is a planned and emergent process rather than just planned.

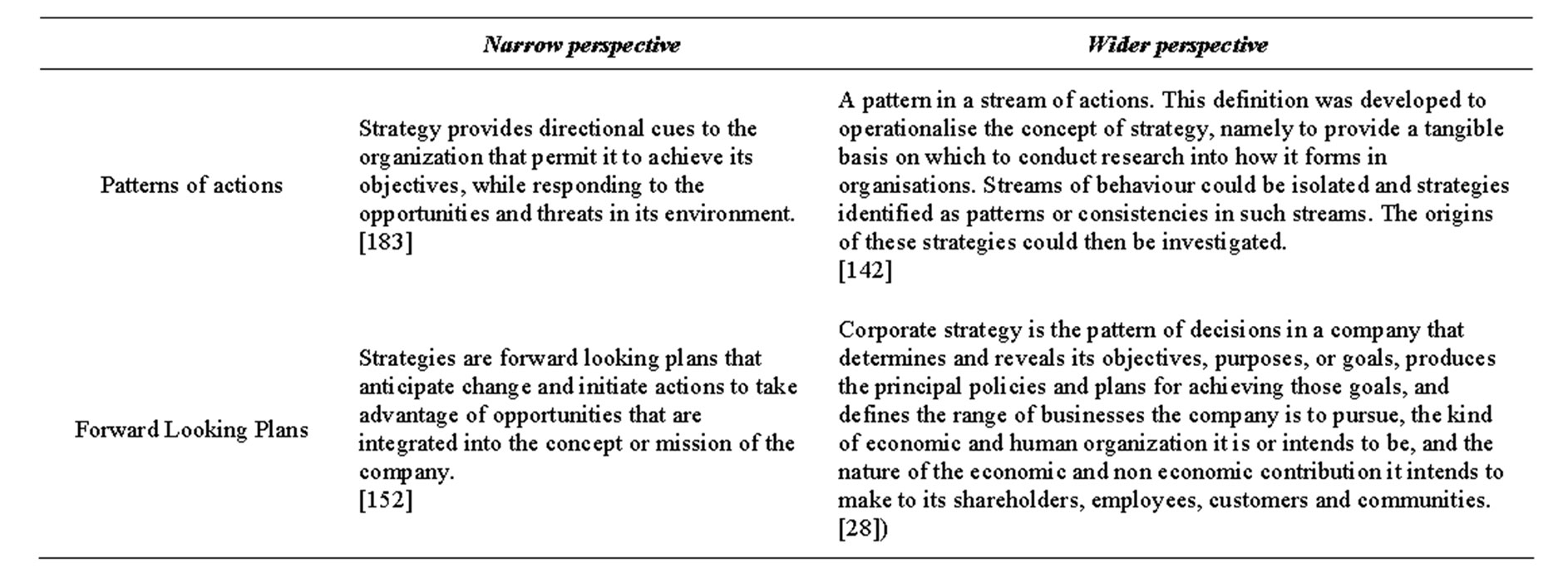

Table 1 below presents contrasting definitions of strategy as patterns of actions (behavioural) and forward looking plans (normative) where some definitions offer a narrow perspective and others offer a wider perspective.

Although individual scholars have heterogeneous views, Hax and Majluf [59: p. 7] have reviewed these in offering a unified multi-dimensional definition of strategy that builds on the seminal work of Chandler, Learned et al. [32,53] and Andrews [28]. This normative perspective combines long range goals, patterns and stakeholders within definition where the ultimate objective of strategy is to “benefit stakeholders”. However, as Bracker [8] suggests, the normative definitions seem to engage alternative meanings to terms such as “pattern, action or operationalise” compared with Schendel and Hofer [43] or Mintzberg and Waters [49]. Additionally, the transition from business policy [53] to strategic management [43] adds to the differences in views. Thus, it seems that the same word can have different meanings to different people.

A comparatively recent contribution to the formulation —implementation debate has emerged from a sociological perspective. Aligned to Mintzberg’s action approach, Strategy as Practice ((S-as-P) [60,61] proposes that strategy is what the firm and its actors do as an activity [62] rather than what they have. Practice is routinisation through self reinforced learning [63] where recursive and adaptive modes co-exist. This definition recognises that practitioners have tacit knowledge [64,65] where learning through participation engages wider intelligences [66] and awareness enables retrospective understanding [67] of behaviour. The post-processual perspective [68] offers a reflective lens which aligns with Mintzbergian definition [51] and attempts to widen the window of investigation from its sociological roots [69]. S-as-P engages the human/social element by focusing on actors’ daily actions and interactions at micro (within the firm) and macro (outside the firm) levels. Further, S-as-P views planning as an aid to strategic thinking if one uses it to synthesise practitioner thought and action.

Although a relatively newer concept with limited empirical support [36], the explanation of consequences of activity [70] may offer insight into realised strategy. The distinction is that research of Practices [71] can be reflective, whereas Practice [72] is embedded, current and on-going. This approach has most suited the research of strategising process outcomes [73]. The implication

Table 1. Strategy as a pattern of actions as opposed to forward looking plans.

being a need to observe the process in real time where the focus on praxis and practitioners requires access to and understanding of actors and internal routines to strategic outcomes. However, theoretical progress on attributions [74], sense-making [67,75], network pictures [76,77] and reflection in action [78] based on Heideggerian phenomenology [79] may enhance investigation, as actors are already embedded in practices [78]. Rather than limiting to the micro level, maybe we can extend these concepts to the macro firm level investigations.

We note that scholars have extended the debate on strategy to the phenomenon of absent strategy. Inkpen [80: p. 2] engages Mintzberg’s strategy [2] as a paradigm to defend the notion that “strategy can be absent in firms” [81] against Bauerschmidt’s [82] criticisms. The challenge is whether intended strategies are fully realised, whether realised strategies are those that were actually intended and to what extent strategies that have been realised are helpful to future success [83]. Further, the literature on non-market strategies [84] is growing where corporate lobbying for favourable outcomes is of increasing concern. This extends in chaotic environments or globalisation agendas to the role of the corporation in managing non-commercial political risks [85].

In summary, the qualitative approach encompasses formation, implementation and historical realisation of outcomes whereas the quantitative approach proposes strategy as internal forward planning. A research consideration is the need for access to firm routines [86] and decision making processes [87]. As an alternative definition, S-as-P engages a very different set of underlying assumptions to theory which emphasise process over content and belief systems within social interaction [68]. Further, the contrasting views seem to be based on differing perspectives of rationality [88]. Whether planned and/or emergent, the study of firms’ strategy is inherently linked to people as entrepreneurs [89] or actors within the firm [90] which more widely, are related to the environments in which the firm operates [40]. We may, therefore, define deliberate or emergent strategy based on how rational one views people [91], firm structures [92] and environments [93] in terms of realised strategy.

Whilst there is diversity in the definition of strategy, we can explain rational behaviour assumptions (Long Range Planning) and on-going activity (Strategy as Practice) within historical patterns (strategy as a result of action). Mintzberg’s progressive definition of realised strategy appears to offer the widest and most integrative investigative lens, whilst appealing to multi-layered research. It balances and synergises the attributes and assumptions of the contrasting alternative definitions i.e. bounded rationality and knowledge or planning, decision making processes, actual doing and consequences of activity.

2.3. Strategy: An Empirically Supported Published Papers Perspective

Scholars debate the academic and empirical research of strategy within internationally recognised journals. A critical investigation of these publications supports an understanding of how those scholars define strategy. What empirical research are scholars doing to support the definition? What are the trends within publications?

The special issue of the Strategic Management Journal (S.M.J.) presents creative and new thinking on issues and methodologies to evolve new strategy paradigms [94]. Phelan et al. [95: p. 1162] are keen to point out that the Strategic Management Journal (S.M.J.) has “…enjoyed a single editor (Dan Schendel) for the past twenty years” as they investigate the changes in content of S.M.J. Accepting the sustained high ranking of the journal, having a single editor allows for consistent editorial policy, but may have also influenced some of the on-going debates. Their findings highlight the increase in empirical investtigation, joint publications and rise in referencing within published papers. Nag et al. [96] support these findings as being positive, implying a preference for a firm specific approach. This more recent study uses Kuhn’s [97] paradigm of shared values to conduct a lexical study of the literature. The study attributes Schendel and Hofer [43] to rechristening the field of strategy. The findings identify the words “firm” and “performance” as most linked to strategy. Interestingly, economic scholars tend to have restricted conceptions of the field and they make little reference to “resources, managers and owners and internal firm” whereas managers were most widely faceted in definition. Nag et al. [96] conclude that the success of strategic management is its multiple perspectives. At the same time, the change in format of papers over the years indicates more stringent criteria for publication.

We can contrast this with Furrer et al.’s [98] more recent quantitative analysis of wider strategic literature. Their findings highlight an increase in articles using keywords: “capabilities and alliances” and a decrease in articles using keywords: “fit and environment”. Furrer et al. [98: p. 11] imply a shift in paradigms from the Structure Conduct Performance (S-C-P) model to the Resource Based View and suggest that current research in 2008, is focusing on integration of corporate and competitive strategies and their implications for performance and competitive posture. The statistical investigation highlights performance, resource based theory (capabilities) [99,100], the Structure Conduct Performance paradigm (environmental modelling) and Strategy and Structure [32] organisation as the top areas of investigation. However, we note that older papers will have benefited from time, citation and debate in the public domain.

These reflective analyses offer insight into the evolution of thinking on strategy. The first study highlights an increase in empirical investigation, whilst both studies acknowledge increased collaboration and integration of elements within debate on strategy. Paradigms and approaches in thinking are progressing with time [101] as earlier research forms a historical base for newer more appropriate paradigms and explanations. The 2008 focus suggests that a more dynamic nature of strategy is emerging towards the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Most recently, Macedo Soares [102], whilst introducing a framework of Global Strategic Network Analysis (GSNA) indicates that the Strategic Management Society has launched a new journal called The Global Strategy Journal (G.S.J.). This is a sister journal to the established S.M.J. and seeks to fill a gap in the market for a specific global orientated strategy journal. Edited by Stephen Tallman and Torben Pedersen, the ten themes include International and Global Strategy, Assembling the Global Enterprise, Performance and Global Strategy and Global Innovation. The leading debates in global strategy [103] identify a need for scholars to theoretically capture institutional views where the question remains: how can methodology best support a broad research scope?

The main theme within the empirically supported published papers is that current research is focused on corporate and competitive strategies through alliances and capabilities. The emergence of new journals reflects new challenges that require integrative responses within the field.

3. Traditional Corporate Strategy Intellectual Frameworks

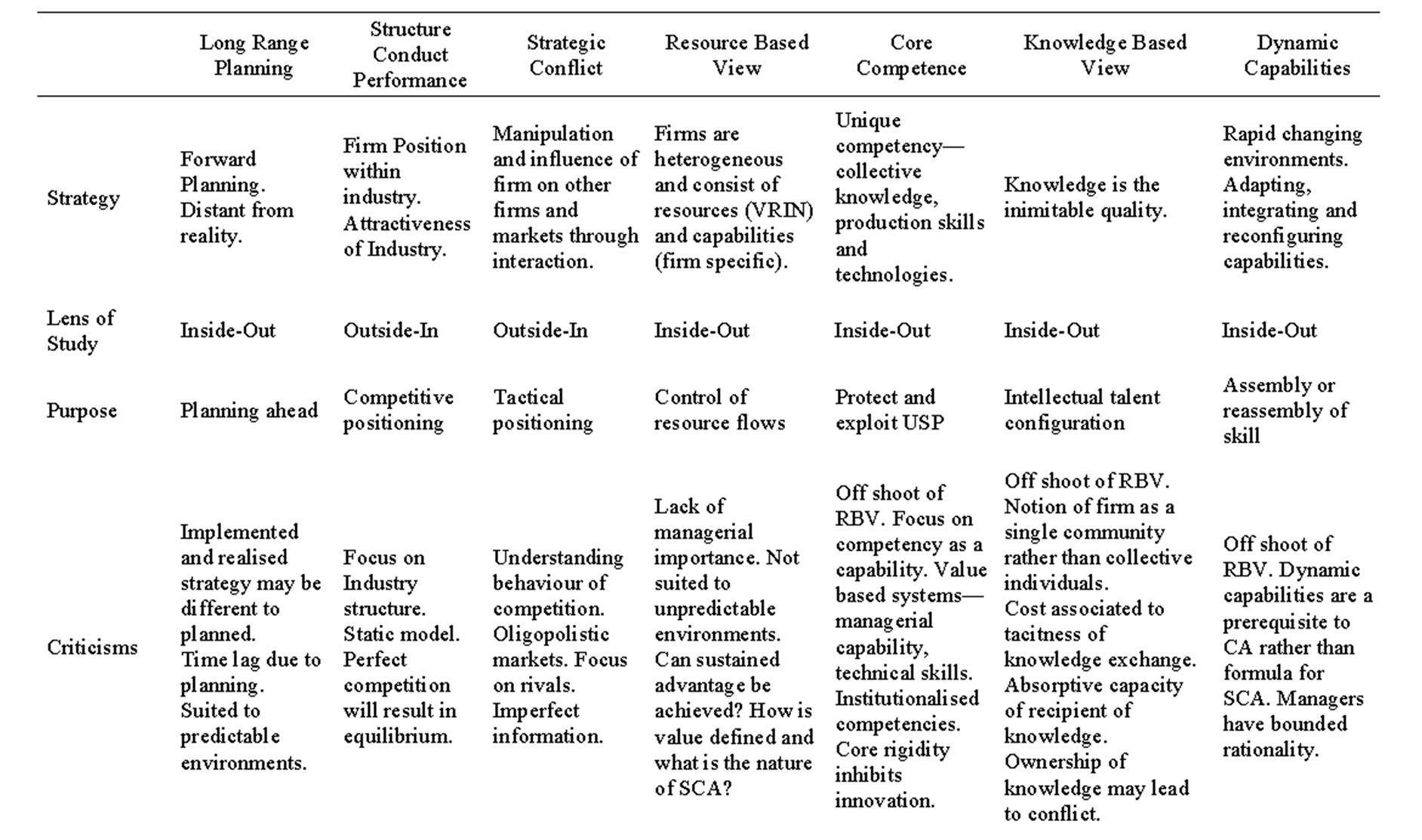

Supporting strategic definition, a range of strategic management theories have emerged as potential intellectual routes to analysis (Table 2). These include Long Range Planning (strategy as planning), Structure Conduct Performance (strategy as competitive posture in industry), the Strategic Conflict model (strategy is to keep rivals off-balance) which is an off-shoot of the Structure Conduct Performance model and Resource Based View (strategy as resources and capabilities). Comparing these, it becomes clear that the narrower purposes of strategy differ for each of the frameworks.

Farjoun [104] clusters these frameworks together suggesting that they are unified by shared epistemological Newtonian mechanistic logic. Internal differentiation emphasises explanation and prescription rather than the relationships that characterise strategy. Farjoun [104] suggests that these frameworks share simplistic assumptions that engage strategy as a posture and time as discrete, therefore this cluster is more suited to predictable environments. In contrast, the organic (adapted from [105]) cluster based on social and natural sciences offers a shift from strategic choice to strategic change where emphasis is based on continuous processes, time is incessant and strategy is about co-aligning and adapting to the dynamic environment. The organic cluster is a more interactive and integrative framework for research, as we can recognise co-ordinated action [104: p. 571] retrospectively as a “pattern in a stream of actions” [49: p. 257].

The Core Competence model (strategy as competence), Knowledge Based View (strategy as knowledge and information know how) and Dynamic Capabilities models (strategy as dynamic capability) are off shoots of the Resource Based View. Competence has derived from the psychological studies of managers and their performance and is the “collection of learning in the organisation and how to co-ordinate production skills and streams of technology” [106]; whereas, the Knowledge Based View focuses on knowledge transfer [107,108] and Dynamic Capabilities [109] use “processes, positions and paths” as internal unique routines to strategy. These models are bound by similar constraints as the Resource Based View [110], but also take a narrower definition of strategy than Andrew’s [28] and are therefore likely to limit the window of research. They propose that competence, knowledge and capability is the source of value within strategy rather than resources and capabilities. These attributes develop over time, where the deployment of strategy remains practically difficult to research [111].

Additionally, it is important to recognise that the different frameworks apply alternative definitions and meanings to sustained competitive advantage and value in terms of strategic outcomes based on their unique frameworks e.g. sustained competitive advantage is based on time [112] within the Structure Conduct Performance model whereas the Resource Based View defines sustained advantage based on inimitability.

In terms of strategic analysis, the frameworks define strategy in terms of internal firm attributes (suited to an inside-out view of the firm) and the environment (suited to an outside-in view of the firm). The research question arises here, how to understand the internal firm attributes in defining strategy? The Structure Conduct Performance based models are the only ones that offer a useable Outside-In view of strategy. Whilst the other models do provide a framework for analysis, the frustrating element is that they all demand internal firm know-how and firm access in defining strategy. This appears to be a major practical disadvantage in engaging these models for empirical strategic historical analysis. Further, the Structure Conduct Performance limitations are that it assumes a defensive position for the firm within the industry structure where it defines the firm in terms of the competition.

If we are to support the qualitative route to strategy definition [51], a wider construct that recognises heterogeneity of the firm and closeness to reality is required

Table 2. Traditional intellectual routes to strategic analysis.

from an outside-in perspective. Leadership elements [46] and the situation place the firm in a nurtured and natural environment, where firm and marketplace co-exist and we cannot understand them independently [113]. A branch of literature has emerged from social and organisational evolution that offers alternative intellectual frameworks.

4. Evolutionary Corporate Strategy Intellectual Frameworks

Supported by evolutionary economics [114,115] and using Friedman’s work [116] to define markets, Nelson and Winter [35] propose that routines are the equivalent of the biological gene in evolutionary economics and the unit of analysis for the firm. In this construct, it is the firm’s skills that lead to adaptation. The question is: do “routines” overcome the criticism of traditional strategic models in offering an integrative definition? Becker [86] suggests that the nature of “routines” and in particular “routine selection” in processes of variation, selection and retention still has limited research. This offers the opportunity to align investigation of “routines” within realised patterns [51]. Firm capabilities are captured as manifested within historic adaptation outcomes. Demonstrable examples of evolutionary economics’ cross-functional appeal include Boschma and Wenting [117]; and Miozzo and Grimshaw [118]. The ground breaking work of evolutionary economics has fuelled further biological derivations of strategic paradigms.

At a time when industry based competitive research was emerging [119,41], Henderson [49] discusses the nature of environments and firms’ behaviour within them. Applying a competitive frame to strategy for advantage, Henderson [49] proposes that in naturally competitive environments, the fittest survive [120]. This ecological perspective uses Wilson [121] as a theory of competition and suggests that Darwin [122] is a better guide to business strategy compared with classical economic theories. Henderson [44: p. 141] states that “strategy is a deliberate search for a plan of action that will develop a business’s competitive advantage and compound it”. The term “plan of action” implies distance from reality and supports the quantitative paradigm. Additionally, the dilemma of whether one relates humans directly to animals [122] or whether decision making abilities make humans different to animals has social implications for strategy. In terms of competition, the definition of advantage for each firm will be unique [123]—is it profit, market share, sales, growth and in which defined environment? Porter [112: p. 77] argues that the role of leadership is to “define and communicate the unique position, making tradeoffs and forging fit among activities”. So, does leadership have the ability to influence strategy in Henderson’s model? And How much value is given to the social element of strategy? Henderson [44] takes a natural approach to the marketplace in which the weak firms die off and the strong survive. Wilson and Hynes [124] additionally qualify that in evolution, selection can be natural (for advantage) and more importantly, as a result of drift (by chance). Hence, it is not necessary that evolution always means “survival of the fittest”. The term evolution is based on the implicit notion of inherited characteristics from the previous generation within a population. Wilson and Hynes [124] criticise business terminology for misunderstanding and ignoring the “genetic drift” [125] aspect of evolution.

Another strategic analytical route has emerged from the field of joint ventures and strategic alliances based on the biological concept of co-evolution, where two (or more) species reciprocally affect each other’s evolution [124]. Evolution is based on the implicit notion of inherited characteristics from previous generations, whereas co-evolution promotes joint advantages through simultaneous changes. The co-evolution model [45,126] embeds strategy in the firm’s adaptation choices. The firm, as an agent, is located within industry and institutional environment where the firm and marketplace co-exist and we cannot understand them independently [113]. The firm co-evolves through strategic alliances [127] using its distinctive capability as value to exploit and explore [128,129], with a view to gaining market power and extracting rents. Thus, through alliances with other agents, the firm secures joint value which is embedded in determining strategy. Das and Teng [130] define co-evolution as “the simultaneous development of organisations, alliances and the environment independently and interactively”.

This lens offers an outside-in definition of strategy and further, the model strongly supports research over long time frames [113] incorporating a historical perspective [131]. We can analyse the co-evolutionary definition of strategy at the society, industry and firm level [124] where evolution is part of co-evolution. The importance of this is that strategy can be defined individually, in dyads or groups. The model supports a more social perspective of the firm [46], thus incorporating a human political dimension to strategic alliances. This framework further offers multidirectional analysis at internal and external layers of interaction. The model refers to Kumar [132] in asking the question, “What is trust?” as it derives value within a continuum of joint exploitation and exploration between agents. The definition of strategy gives recognition to time and space through alliances as the strategic portfolio forms [133]. Most recently, co-evolution has been engaged at Global Multi Business Firm (GMBF) level based on a process of strategic assembly [134,135] with emphasis on leadership through animation.

5. The Rise and Fall of Intellectual Routes to Analysis

The literature suggests that the definition of strategy has gone through a series of Kuhnian [97: p. 88] style shifts over the last sixty years, where “crises are a necessary pre-condition for the emergence of novel theories”. Hoskisson et al. [136: p. 417] support this suggestion to some extent in their review of strategic management. They argue that the “primary theoretical and methodological basis” took a contingency perspective and used a resource framework which has since gone through a series of pendulum swings which evolutionary paradigm developments and methodological approaches support. Hoskisson et al. [136] suggest that each swing has resulted in increased sophistication and maturity.

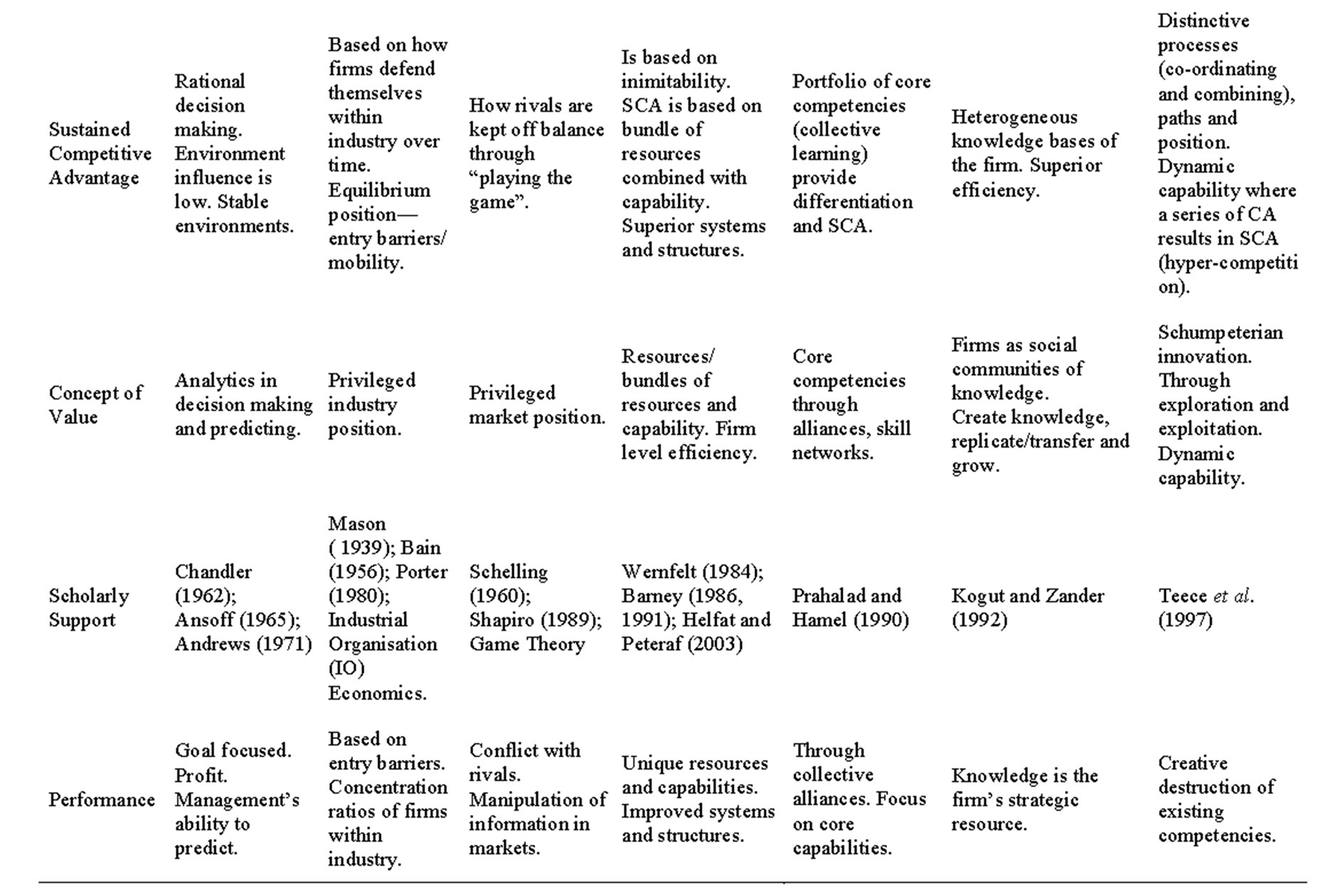

Similarly, Hafsi and Thomas’s [137: p. 512] historical investigation traces the differing approaches back to “two broad routes”—the holistic route and analytical route. These may represent the Qualitative and Quantitative paradigms of strategy in Table 3 below. Hafsi and Thomas [137] suggest that the analytical approach took over the holistic approach in the 1970s, which Rumelt et al. support [31]. This suggests that the scholarly study of strategy developed from earlier theorising towards a more analytical framework, as information became more readily available.

Hafsi and Thomas [137] themselves, hold the view that the academic field of strategy suffers from a high level of misunderstanding and isolation of elements that can be measured. Bower [37] seems to share this frustration twenty years earlier. Referring to Table 3 suggests that Hafsi and Thomas [137] and Bower [37] prefer a quantitative definition of strategy and at the time of writing, the qualitative route was dominating research in the field.

Comparatively, Barney [100] adopts a qualitative route (based on the assumptions of the firm for a resource based model of competitive advantage), along with Rumelt et al. [31] who imply the reason for disagreement in the field is positive, due to firms behaving differently i.e. situational. Haugstad [138] advocates strategizing as a doing activity (S-as-P) in highlighting that there are competing schools of thought and disagreements about what strategy theory should explain. Where S-as-P has different assumptions, Haugstad [138: p. 3] identifies the “considerable effort during the last decade within the field to identify ‘paradigms’ [56] and search for new approaches [31]”. Thus, the lack of holistic ontological and heuristic support to definition [137] is problematic.

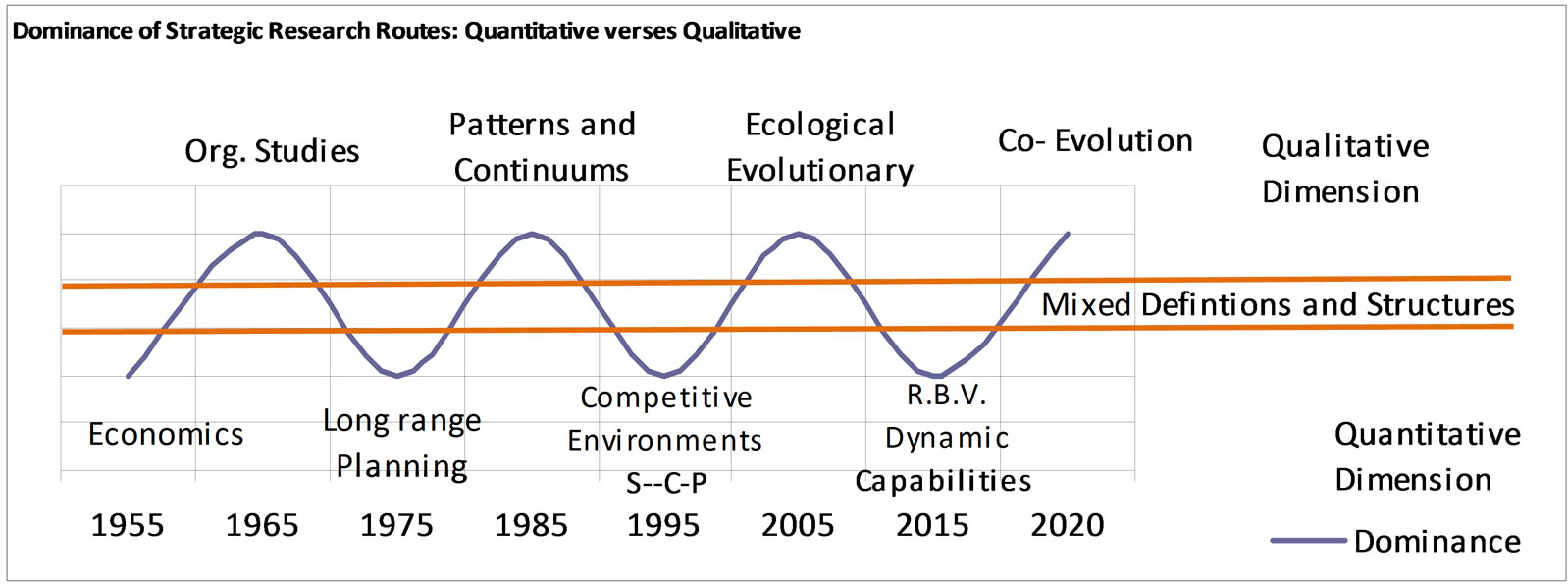

Applying Porter’s [112] ten year horizon of strategic position to the cyclical dominance of strategic schools of thought (Figure 1) offers a wider perspective of Hoskisson et al. [136] swings as a fluid development of strategy. The fluidity further recognises, by adapting Kolb’s [139] model, that definitions and theories take time [139] for individuals to conceive (2 yrs), to publish for debate (3 yrs), to empirically apply (2 yrs) and for others to accept (3 yrs). Thus, rather than Kuhnian [97] shifts, defining and developing strategy becomes a Lakatosian [140] progressive/degenerative research programme within the dimensions of time and space. Figure 1 portrays an idealised representation of the cyclical development of strategy. Whilst the figure presents the dominant schools within the continuum of time, the line recognises oscillations, at a microscopic level, as other schools of thought will have naturally been competing at the time.

Table 3. Qualitative and quantitative paradigms of strategy.

Adapted from Hafsi and Thomas (2005) [137].

Figure 1. Cyclical dominance of intellectual schools of thought in corporate strategy.

In Figure 1 above, the quantitative RBV and its offshoots (KBV; DC) currently dominate corporate strategy research. However, the shift towards evolutionary quailtative frameworks in the form of co-evolution reflects a need for holistic multi-level understanding within the field. Most recently, Moussetis [141] succinctly presents the historical competing theories, typologies and empirical studies in the field of strategy that have resulted in competing schools of thought. Whether referring to Mintzberg et al.’s [51] taxonomy or Moussetis’ [141] tables, we can follow the theoretical foundation of strategy. Current research continues to focus on specialisation within definition, e.g. Splitter and Seidl [142] refer to the work of Johnson et al.’ [143,144] and Golsorkhi et al. [145] on a “practice based approach to strategy” where knowledge and capability drive definition.

Scholars have explored the definitions, paradigms and development of corporate strategy research within space and time. The earliest theorising of strategy was contingent and resource based within stable and simple environments. The classical scholars Ansoff [33] and Andrews [28] pursued an integrative definition at the time. In the modern complex interconnected environment, a qualitative holistic definition within a multilevel framework is more appropriate for research purposes. There is a need for holistic longer term collaborative research within the field.

6. Towards a Collaborative Corporate Strategy Research Programme

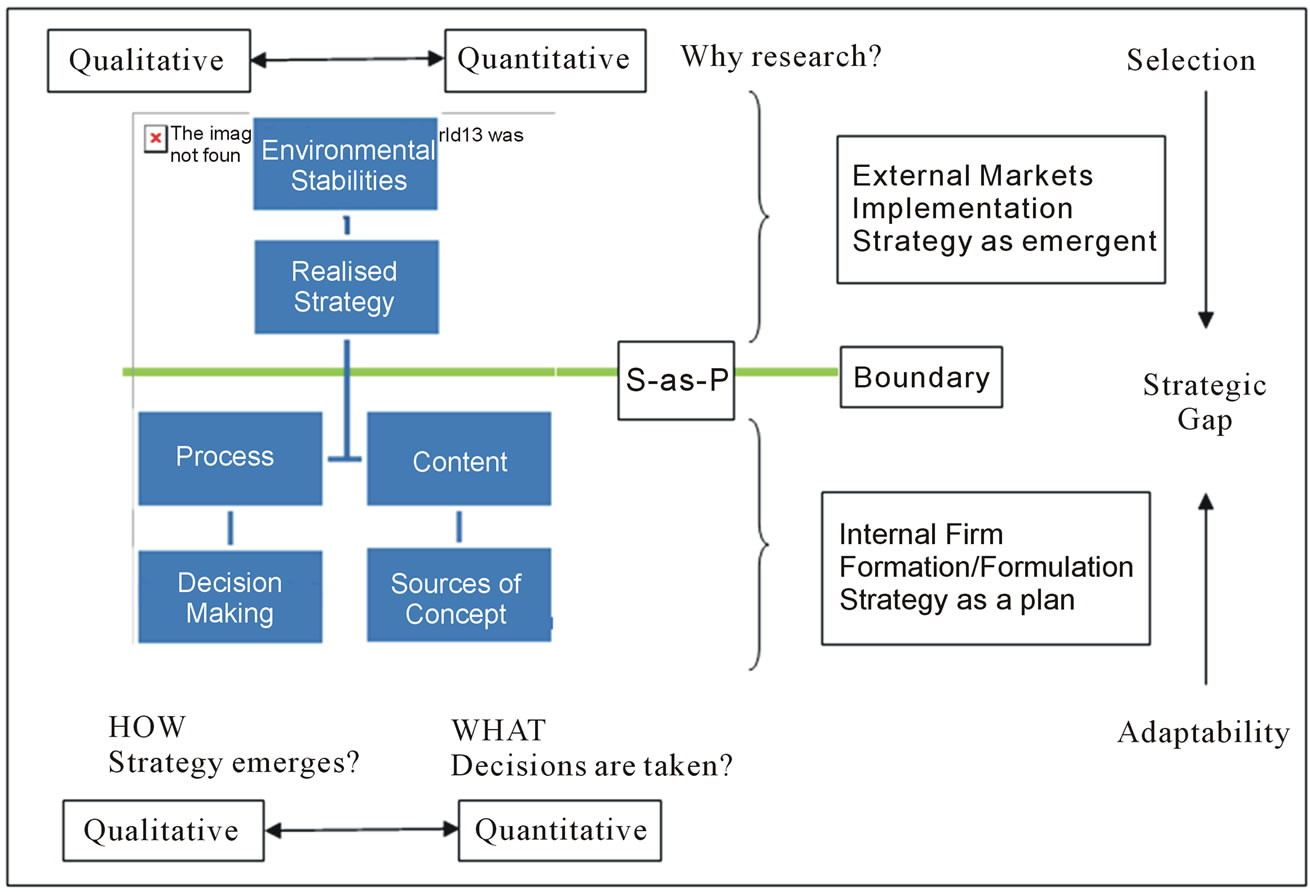

Over the years, the qualitative intellectuals have preferred continuums to appeal to unique firm qualities; whereas, quantitative intellectuals have pursued specialisation as routes to universally applicable research frameworks. Mintzberg and Waters’ [49] theoretical underpinning of emergent and planned within strategy formation continuum argues that the majority of firms use strategies with both emergent and planned qualities. This implies that the majority of firms are within the “Umbrella and Process strategies” [49]. In these two streams, leaders exercise partial control over actors, set direction and allow actors’ monitored decision making abilities within complex, unpredictable environments that require fast responses. Kipping and Cailluet [146] have used the continuum to conduct a historical study of Alcan and propose that there is a correlation between strategy and structure [32] and that “This co-evolution and the forces that drove it warrant additional research” [146: p. 103]. A much earlier study by Hall and Saias [147] seems to support the co-evolution of strategy and structure as a two way process of influence whereby strategy is internalised within the firm [148]. In this respect, we can interpret each bounded definition or strategic methodological approach to research within the proposed continuum ranging from qualitative to quantitative for each dimension of strategy (see Figure 2).

The dimensional boundaries [149] complexity [150] is enhanced with increasing research on the boundary between firm and marketplace. Coase [26] and Chandler’s [32] seminal works in stable environments have evolved into research on growth [27], absorptive capacities [151] and international entry modes [152] within dynamic unstable [153] markets. The firm adapts to environmental pressures and a gap exists between firm and environments [154]. This gap can be described as the difference between the firm’s current and desired position [155], a knowledge gap [108], the difference between action, learning and integration [156], strengths/weaknesses and opportunities/threats [28], or more appropriately the process of gap bridging between capability and opportunity space [157,158]. In this regard, the gap can be potential, deliberate, emergent or realised. The capabilityopportunity framework links deliberate and emergent and enhances hermeneutic and interpretative capacity in analysis of firm and environments. In this respect, innovation is the driver to expansion or contraction of the realised gap set (RGS). The RGS incorporates foresight, judgement, mindfulness and chance [124] as a firm

Figure 2. Collaborative corporate strategy research programmes (C.C.S.R.P.). Designed with references to Mintzberg and Waters (1985); Chakravarti, (1982), Pettigrew (1987); Slevin and Covin (1997); Dagnino (2003).

adapts to the market.

Casillas and Acedo’s [159; p. 18] most recent publication states that “the role of time must be incurporated into theory (and not just treated as a boundary condition) if theory is to provide accurate ontological support to phenomenon” [160: p. 658]. In this respect, our framework is under-pinned by multi-layered co-evolutionary theory [126] and events/processes represent points in time and space. The boundary between the firm and markets are interconnected and can influence each other from adaptive (within the firm) to global (market events) level.

Intra-firm specialisation based on strategic continuum [49] is offered by Slevin and Covin’s [92] in depth analysis of the strategy formation process [57] which develops a continuum of emergent to planned decision making. In this study, the authors discuss strategy as a process [161] and content [162] and there is further theoretical debate on decision making [163] and definition of content [31,164]. The result is continuums within continuums. A more detailed sociological process perspective offered by Pettigrew [58] refers to the debates between choice [165] and change scholars before selecting to make content (what) and process (how) inseparable. Pettigrew’s [58,161] guiding assumptions align with Mintzberg et al.’s [51] holistic definition rather than a linear definition as processes are embedded in contexts. Titus Jr. et al. [166] further Slevin and Covin’s work [92] in aligning firm growth with strategic process. The curvilinear findings support a midpoint for optimal growth of firms in the emergent to planned continuum. Figure 2 represents the co-evolving complexity [167] of qualitative versus quantitative continuums to content and process [168] as the scholarly dimensions of adaptive strategy.

Inter-firm strategy is influenced by strategic partnerships [45] which may take the form of alliances, collaborative R&D agreements or spin-off companies. The relationship and management of partnerships pursues shared strategic outcomes and joint benefits. Further environmental stability and dynamics result in selective influences. These may take the form of competitive dynamics, revision of institutional policies and competitive control mechanisms, or wider factors such as global supply chains [169] that impact business conduct. At the inter-firm level the selective influences on strategy are wider and the emergent or chance factor is higher due to lack of control and the political nature of co-operation.

The process [163,170] and nature [171,172] of decision making [173,174] has empirical studies over many years that advance earlier research. These studies support the view that strategy is influenced by environment, firm structure, learning, comprehensiveness of decision making, cognition, social relationships and networks [175], where as a result of internal and external influences [176,136] firm performance is impacted [177]. The deeper sociological perspective [176] includes elements of political [178] and cultural [179] influences within definition. Further, in some cases a firm may not have a strategy [81] and it may instead simply emerge as a result of doing [180]. If the definition of strategy is to consider these views, then it has to apply a qualitative definition rather than a quantitative one. Strategy cannot just be a long term plan, but must consider the incremental impacts of space and time in decision making. One must consider the influence of leaders as powerful stakeholders [181], other stakeholders [30] and the situational context as strategy is implemented and actually realised. These factors only become apparent from a historical perspective, once strategy has actually been realised.

In this regard, realised strategy [51] can provide a dimensional boundary (Figure 2) to explain strategy within phenomenon [182] and research analysis. The framework in Figure 2 thus incorporates the contrasting alternative definitions as partial windows within a wider Mintzbergian window to strategy. The heterogeneous firm exists in the marketplace. We must account for the influences of internal/external factors and the boundary between firm and environment as permeable and fluid to enable change.

No single institution is likely to have the full spectrum of skills and expertise for the complete research programme. In this regard, Figure 2 represents opportunity for building collaborative research programmes across networks of institutions with longer term visions and more holistic outcomes.

7. Contribution and Implications of C.C.S.R.P.

Currently, no such holistic framework of strategy research at the corporate level exists. The C.C.S.R.P. framework serves as a useful tool for organising corporate strategy research within the institution because it captures the full range of possibilities in strategy definition and the alternative strategic management methodological routes to investigation. The implications being that design of research may better engage internal skill sets and/or build relationships between multiple studies. In this case, the question arises whether the institution should specialise (depth) or extend (range) output for meaningful impact? Once a competitive position of corporate strategy research has been established within our framework, the potential to externally collaborate with complimentary skill sets from other institutions emerges. Thereby, the capacity for a longer term collaborative research agenda could include international case studies; multi-level management studies of corporation; or advanced mixed method investigations of greater practical value. Whereby the questions arise how to best form intellectual property and funding agreements between institutional alliances or co-operations? And how to assess the shared value of research output?

Examples of longer term research programmes may be the Centre for Corporate Strategy and Change at Warwick University [183] and the research on S-as-P at Aston University. However, these remain specialised and people specific. Therefore C.C.S.R.P. seeks to uniquely provide the opportunity to integrate research within and across institutions for holistic outcomes. In consideration, the C.C.S.R.P. framework is underpinned by eight assumptions to the research programme:

1) Ontological rationality includes morality [184].

2) History matters [185] and creates contexts [183]. from which reflective learning can help change behaveiour or forward looking strategies.

3) Strategy is a Mintzbergian window which includes formulation; formation; decision making and realisation [51].

4) Qualitative research is conceptual/abstract which provides the foundation for quantitative analytical research. Thus, progressive research requires collaborative qualitative and quantitative research cycles where each research module informs the next:

5) Co-evolution theory underpins the framework [126] where the firm and market-place co-exist and we need to understand both together. Multi-level influences can be at the firm; industry; national and global levels. Both adaptive and selective influences can impact strategic outcomes.

6) Within each of the dimensional boundaries .

.

in Figure 2, continuums can range between qualitative and quantitative philosophical and methodological positions. Modules of research can be conceptual, analytical or in advanced cases, mixed method.

7) The C.C.S.R.P. framework is inclusive of all strategic management frameworks which we can collaboratively combine to establish a holistic understanding of strategy from adaptive, selective and RGS perspectives.

8) We have derived this framework from the literature on strategy and strategic management. It is a corporate strategy framework that integrates research for longer term research programmes.

8. Future Research Direction

Coase [186] asks “why is the economy not run as one big factory?” His seminal work [26] identified the boundaries and heterogeneity of the firm. Most recently Schumpeterian change [187] has emerged in the form of the global financial crisis [188], Arab Spring, the rise of BRICS (Brazil, Russian, India, China and South Africa) and European integration which suggests that risk [189] and uncertainty [190] extend globally as a distinguishing feature of stable/unstable markets [153]. We have designed our framework to suit current dynamic/chaotic environments and longer term collaborative research programmes. The questions we raise in implications of C.C.S.R.P. could be addressed in how institutions internally assess and plan their capacity and competitive position of research output? More critical is how specialised research institutions manage their internal relationships and collaborate with each other externally? Could Verien structures support complimentary alliances? And resolve the limitation of intellectual rights of institution or individual researcher in longer term programmes? Alternatively, future research may address how methodological pathways best integrate research modules at different levels or internationally? As such, the C.C.S.R.P. framework is a contribution towards integrating the global strategic literature for better application of strategies (UN; World Bank) through collaborative skills and structured research programmes that respect diversity across interconnected environments.

REFERENCES

- I. Ansoff, “Strategies for Diversification,” Harvard Business Review, 1957, pp. 113-124.

- H. Mintzberg, “Patterns in Strategy Formation,” Management Science, Vol. 24, No. 9, 1978, pp. 934-948. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.24.9.934

- P. Jarzabkowski, “Shaping Strategy as a Structuration Process,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51, No. 4, 2008, pp. 621-656.

- R. M. Cyert and J. G. March, “A Behaviour Theory of the Firm,” 2nd Edition, Prentice Hall, Englewood, 1963.

- J. B. Quinn, “Strategies for Change: Logical Incrementalism,” Chicago, Irwin, 1980.

- P. Drucker, “The Concept of the Corporation,” The John Day Company, New York, 1972.

- T. R. Zenger, T. Felin and L. S. Bigelow, “Theories of the Firm Market Boundary,” Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2011, pp. 89-133.

- J. Bracker, “The Historical Development of the Strategic Management Concept,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1980, pp. 219-224.

- S. Tzu, “The Art of War (written on bamboo),” 512 BC.

- J. J. J. M. Amiot, “Art Militaire Chinois ou Recueil d’anciens Traités sur la Guerre Composés avant l’ère Chrétienne par Différents Généraux Chinois,” Traduit du Chinois par le Père Amiot, Didot l’Aîné, Paris, 1772.

- L. Giles, “English Translation of Tzu, S. on The Art of War: The Oldest Military Treaties in the World,” Texas Norte Press, El Paso, 2005.

- C. N. Chu, “The Art of War for Women: SunTzu’s Ancient Strategies and Wisdom for Winning at Work,” Currency Double Day, New York, 2007.

- J. Gimian and B. Boyce, “The Rules of Victory: How to Translate Chaos and Conflict,” 2008.

- E. Rogell, “The Art of War for Dating: Win over Women using Sun Tzu’s Tactics,” Adams Media Corporation, Boston, 2011.

- D. G. Krause, “The Art of War for Executives,” Berkeley Publishing Group, New York, 1995.

- G. Michaelson and S. Michaelson, “Sun Tzu for Success: How to Use the Art of War to MasterChallenges and Accomplish the Important Goals in your Life,” Adams Media, Boston, 2003.

- K. Krippendorf, “The Art of the Advantage: 36 Strategies to Seize the Competitive Edge,” Texere, NewYork, 2003.

- R. F. Grattan, “On the Origins of Strategy,” Defence and Strategy, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2009, pp. 137-150.

- L. Giles, “Translation of Tsu, S. on The Art of War: The Oldest Military Treaties in the World. Translated from Chinese with Introduction and Critical Notes,” The Project Gutenberg Ebook Publication, 1910. www.gutenberg.org

- A. Smith, “The Theory of Moral Sentiments,” Millar, London, 1759.

- J. B. Sykes, “The Concise Oxford Dictionary,” 7th Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1985.

- S. Hawker, “Little Oxford English Dictionary,” 9th Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

- C. Soanes, “The Paperback Oxford English Dictionary,” 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010.

- R. Ilson, “Reader’s Digest Great Illustrated Dictionary,” The Reader’s Digest Association Limited, New York, 1984.

- M. Waite, L. Hollingworth and D. Marshall, “Compact Oxford Thesaurus,” 3rd Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008.

- R. H. Coase, “The Nature of the Firm,” Economica (London School of Economics) New Series, Vol. 4, No. 16, 1937, pp. 386-405.

- E. Penrose, “The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. An Introduction by Cristos Petelis,” 4th Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 2009.

- K. R. Andrews, “The Concept of Corporate Strategy,” 3rd Edition, Dow Jones Irwin, Berkeley California, 1971.

- J. W. Rivkin and N. Siggelkow, “Balancing Search and Stability Interdependencies amongst Elements of Organisational Design,” Management Science, Vol. 49, No. 3, 2003, pp. 290-321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.3.290.12740

- R. E. Freeman, “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach,” Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

- R. P. Rumelt, D. E. Schendel and D. J. Teece, “Fundamental Issues in Strategy,” In: R. P. Rumelt, D. E. Schendel and D. J. Teece, Eds., Fundamental Issues in Strategy, Harvard University Press, Boston, 1994, pp. 9-54.

- A. D. Chandler Jr., “Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 1962, pp. 383-394.

- I. Ansoff, “Corporate Strategy: An Analytical Approach to Business Policy for Growth and Expansion,” McGraw Hill, New York, 1965.

- R. Whittington, “Completing the Practice Turn in Strategy Research,” Organisation Studies, Vol. 27, No. 5, 2006, pp. 613-634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840606064101

- R. Nelson and S. G. Winter, “An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change,” MA Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1982, pp. 1-50.

- P. Jarzabkowski and A. P. Spee, “Strategy as Practice: A Review and Future Direction for the Field,” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 69-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00250.x

- J. L. Bower, “Business Policy in the 1980s,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1982, pp. 630-638.

- E. Chaffee, “Three Models of Strategy,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1985, pp. 89-98.

- S. L. Brown and K. M. Eisenhardt, “Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos,” Harvard Business Press, Boston, 1998.

- M. E. Porter, “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analysing Industries and Competitors,” Free Press, NewYork, 1980.

- M. E. Porter, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance,” Free Press, New York, 1985.

- R. A. Burgelman, “A model of the Interaction of Strategic Behavior, Corporate Context, and the Concept of Strategy,” Academy of management Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1983, pp. 61-70.

- D. E. Schendel and C. W. Hofer, “Strategic Management: A New View of Business Policy and Planning,” Little, Brown, Boston, 1979.

- B. D. Henderson, “The Origin of Strategy: What Business Owes Darwin and Other Reflections on Competitive DyNamics,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 67, No. 6, 1989, pp. 139-143.

- M. P. Koza and A. Y. Lewin, “The Co-Evolution of Strategic Alliances,” Organisational Science Special Issue: Managing Partnerships and Strategic Alliances, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1998, pp. 255-264.

- B. Lovas and S. Ghoshal, “Strategy as Guided Evolution,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 9, 2000, pp. 875-896. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200009)21:9<875::AID-SMJ126>3.0.CO;2-P

- J. Hutchinson, “The Meaning of ‘Strategy’ for Area Regeneration: A Review,” The International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2001, pp. 265-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513550110390828

- J. Von Neumann and O. Morgenstern, “Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1953.

- H. Mintzberg and J. A. Waters, “Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 6, No. 3, 1985, pp. 257-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060306

- H. Mintzberg, “The 5Ps of Strategy,” California Management Review, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1987, pp. 11-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/41165263

- H. Mintzberg, B. Ahlstrand and J. Lampel, “Strategy Safari: Your Complete Guide Through the Wilds of Strategic Management,” 2nd Edition, Pearson Education Limited, Upper Saddle River, 2009.

- W. H. Newman and J. P. Logun, “Strategy Policy and Central Management,” 5th Edition, South Western Publishing Company, Cincinnati, 1971.

- E. P. Learned, C. R. Christensen, K. Andrews and W. Guth, “Business Policy: Text and Cases,” R. D. Irwin, Homewood, 1965.

- I. Ansoff, “Critique of Henry Mintzberg’s the Design School: Rediscovering the Basic Premises of Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, 1991, pp. 449-461.

- H. Mintzberg, “The Design School: Reconsidering the Basic Premises of Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 11, No. 3, 1990, pp. 171-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250110302

- D. E. Schendel, “Introduction to the Summer 1994 Special Issue—Strategy Search for New Paradigms,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, Suppl. S1, 1994, pp. 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150901

- H. Mintzberg, “The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning,” Financial Times Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2000.

- A. M. Pettigrew, “The Character and Significance of Strategy Process Research,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 13, No. S2, 1992, pp. 5-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250130903

- A. C. Hax and N. S. Majluf, “Strategy and the Strategy Formation Process,” Sloan School of Management, 1986, pp. 1-22.

- [61] R. Whittington, “Strategy Practice and Strategy Process: Family Differences and the Sociological Eye,” Organization Studies, Vol. 28, No. 10, 2007, pp. 1575-1586. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840607081557

- [62] G. Johnson, K. Scholes and R. Whittington, “Exploring Corporate Strategy,” 8th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2008.

- [63] L. S. Vygotsky, “Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes,” 14th Edition, Harvard University Press, Boston, 1978.

- [64] P. Jarzabkowski, “Centralised or De-Centralised? Strategic Implications of Resource Allocation Models,” Higher Education Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 1, 2002, pp. 5-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00200

- [65] M. Polanyi, “Tacit Knowledge,” University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1966.

- [66] M. Polanyi, “Knowing and Being,” University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1969.

- [67] H. Gardner, “Multiple Intelligences. The Theory in Practice,” Basic Books, New York, 1993.

- [68] K. E. Weick, “Sense Making in Organisations,” Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 1995.

- [69] R. Chia and R. B. MacKay, “Post-Processual Challenges for the Emerging Strategy-As-Practice Perspective: Discovering Strategy in the Logic of Practice,” Human Relations, Vol. 60, No. 1, 2007, pp. 217-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0018726707075291

- [70] H. Tsoukas, “Practice, Strategy Making and Intentionality: A Heideggerian Onto-Epistemology For Strategy-As-Practice,” In: D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl and E. Vaara, Eds., The Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009, pp. 47-62.

- [71] P. Jarzabkowski and R. Whittington, “A strategy as practice approach to strategy research and education,” Journal of Management Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2008, pp. 282-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1056492608318150

- [72] T. R. Schatzki, “Peripheral Vision: The Sites of Organizations,” Organization Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2005, pp. 465-484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050876

- [73] H. Tsoukas, “Complex Knowledge: Studies in Organisational Epistemology,” Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005.

- [74] S. Maitlis and T. B. Lawrence, “Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark: Discourse and Politics Is the Failure to Develop an Artistic Strategy,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2003, pp. 109-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.t01-2-00006

- [75] F. Heider, “The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations,” John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, 1958. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10628-000

- [76] P. Hansen, “Making Sense of Financial Crisis and Scandal: A Danish Bank Failure in the Era of Finance Capitalism,” Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, 2011.

- [77] D. Ford and M. Redwood, “Making Sense of Network Dynamics Through Network Pictures: A Longitudinal Case Study,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 34, No. 7, 2005, pp. 648-657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.05.008

- [78] S. C. Henneberg, P. Naude and S. Mouzas, “Sense Making and Management in Business Networks: Some Observations, Considerations and a Research Agenda,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 39, No. 3. 2010, pp. 355-360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2009.03.011

- [79] D. Yanow and H. Tsoukas, “What Is Reflection in Action? A Phenomenological Account,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 46, No. 8, 2009, pp. 1339-1364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00859.x

- [80] D. Moran, “Introduction to Phenomenology,” Routledge, Cornwall, 2000.

- [81] A. C. Inkpen, “The Seeking of Strategy Where It Is not: towards a Theory of Strategy Absence. A Reply to Bauerschmidt,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, No. 8, 1996, pp. 669-670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199610)17:8<669::AID-SMJ822>3.0.CO;2-1

- [82] A. C. Inkpen and N. Chaudhury, “The Seeking of Strategy Where It Is not: Towards a Theory of Strategy Absence,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, 1995, pp. 313-324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250160405

- [83] A. D. Bauerschmidt, “Speaking of Strategy: A Comment on Inkpen and Chaudhury’s (1995),” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, No. 8, 1996, pp. 665-667. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199610)17:8<665::AID-SMJ821>3.0.CO;2-G

- [84] H. Sminia, “Process Research in Strategy Formation: Theory, Methodology, and Relevance,” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 97-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00253.x

- [85] J. P. Bonardi, G. Holburn and R. Van den Bergh, “Nonmarket Performance: Evidence from US Electric Utilities,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 49, No. 6, 2006, pp. 1209-1228. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.23478676

- [86] Y. Q. Gao, “Institutional Change Driven by Corporate Political Entrepreneurship in Transitional China: A Process Model,” International Management Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2008, pp. 22-34.

- [87] M. C. Becker, “Organisational Routines: A Review of the Literature,” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2004, pp. 643-677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icc/dth026

- [88] M. Nilsson and H. Dalkmann, “Decision Making and Strategic Environmental Assessment,” Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2001, pp. 305-327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1464333201000728

- [89] L. A. Franco and F. Ackermann, “How OR can Contribute to Strategy Making,” Journal of Operational Research Society, Vol. 62, No. 5, 2011, pp. 911-932.

- [90] C. McGowan, “A Critical Investigation into how Independent Incubate Entrepreneurs Perceive their Role and Contribution,” Northampton Business School, 2011.

- [91] S. Mantere, “Role Expectations and Middle Manager Strategic Agency,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2, 2008, pp. 294-316.

- [92] G. Gigerenzer, “Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty. Evolution and Cognition,” Oxford University Press, New York, 2008.

- [93] Slevin, D. and J. Covin, “Strategy Formation Patterns, Performance and the Significance of Context,” Journal of Management, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1997, pp. 189-209.

- [94] W. G. Astley and A. H. Van De Ven, “Central Perspectives and Debates in Organisational Theory,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2, 1983, pp. 245-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2392620

- [95] C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “Strategy as a Field of Study: Why Search for a New Paradigm?” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. S2, 1994, pp. 5-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250151002

- [96] S. Phelan, M. Ferreira and R. Salvador, “The First Twenty Years of Strategic Management Journal,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23, No. 12, 2002, pp. 1161- 1168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.268

- [97] R. Nag, K. G. Corley, and D. A. Gioia, “The Intersection of Organisational Identity, Knowledge and Practice: AtTempting Strategic Change via Knowledge Grafting,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2007, pp. 821-847. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.26279173

- [98] T. Kuhn, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” 2nd Edition, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1970.

- [99] O. Furrer, H. Thomas and A. Goussevskaia, “The Structure and Evolution of the Strategic Management Field: A Content Analysis of 26 Years of Strategic Management Research,” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2008, pp. 1-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00217.x

- [100] B. Wernfelt, “A Resource Based View of the Firm,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 5, 1984, pp. 246- 250.

- [101] J. B. Barney, “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage,” Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1991, pp. 99-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- [102] J. Smothers, M. Hayek, L. A. Bynam, M. M. Novicevic, M. R. Buckley and S. Carraher, “Alfred D. Chandler, Jr.: Historical Impact and Historical Scope of His Works,” Journal of Management History, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2010, pp. 521-526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17511341011073997

- [103] T. D. L. V. A. Macedo Soarres, “Ensuring Dynamic Strategic Fit of Firms that Compete Globally Inalliances and Networks: Proposing the Global SNA—Strategic Network Analysis—Framework,” Revista Administracao Publica, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2011, pp. 67-105.

- [104] M. W. Peng and E. G. Pleggenkuhle-Miles, “Current Debates in Global Strategy,” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 51-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00249.x

- [105] M. Farjoun, “Towards an Organic Perspective on Strategy,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23, No. 7, 2002, pp. 561-594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.239

- [106] T. Burns and G. M. Stalker, “The Management of Innovation,” Tavistock, London, 1961.

- [107] C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “The Core Competence and the Corporation,” Harvard Business Review, 1990, pp. 71-91.

- [108] B. Kogut and U. Zander, “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities and the Replication of Technology,” Organization Science, Vol. 3, No. 1992, pp. 383-397. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

- [109] M. H. Zack, “Managing Codified Knowledge,” Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1999, pp. 45-58.

- [110] D. J. Teece, G. Pisano and A. Shuen, “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 7, 1997, pp. 509-533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

- [111] A. Lockett, S. Thompson and U. Morgenstern, “Reflections on the Development of the RBV,” International Journal of Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 9-28.

- [112] V. Ambrosini and C. Bowman, “What are Dynamic Capabilities and are They a Useful Construct in Strategic Management?” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2009, pp. 29-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00251.x

- [113] M. E. Porter, “What Is Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, 1996, pp. 61-78.

- [114] W. McKelvey, “Quasi-Natural Organisational Science,” Organisational Science, Vol. 8, No.4, 1997, pp. 352-380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.8.4.351

- [115] T. B. Veblen, “Why Is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 12, No. 3, 1898, pp. 373-397 (Reprinted in Veblen, The place of Science in Modern Civilisation and Other Essays, NewYork, Huebsch, 1919).

- [116] J. Schumpeter, “The Theory of Economic Development,” Harvard Press, Cambridge 1934

- [117] M. Friedman, “The Role of Monetary Policy,” American Economic Review, Vol. 58, No. 1, 1968, pp. 1-7.

- [118] R. A. Boschma, and R. Wenting, “The Spatial Evolution of the British Automobile Industry. Does Location Matter?” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2007, pp. 213-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtm004

- [119] M. Miozzo and D. Grimshaw, “Capabilities of Large Services Outsourcing Firms: The Outsourcing Plus Staff Transfer model in EDS and IBM,” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 20, No. 3, 2011, pp. 909-940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtr014

- [120] M. E. Porter, “The Contributions of Industrial Organisation to Strategic Management,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1981, pp. 609-620.

- [121] H. Spencer, “The Factors of Organic Evolution,” Reprinted with additions from Ninteenth Century, Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, 1886/2004.

- [122] E. O. Wilson, “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis,” The Belknap Press of Harvard University, Boston, 1975.

- [123] C. R. Darwin, “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life,” John Murray, London, 1859.

- [124] M. E. Porter, “Why do Good Companies Set Bad Strategies? Wharton’s SEI Centre Distinguished Lectures Series,” Emerald Group Publishing, Wharton Business School, 2009.

- [125] J. Wilson, and N. Hynes, “Co-Evolution of Firms and Strategic Alliances: Theory and Empirical Evidence,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 76, No. 5, 2009, pp. 620-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2008.08.005

- [126] R. Lande, “The Maintenance of Genetic Variability by Mutation in a Quantitative Character with Linked Loci,” Genetic Resources, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1975, pp. 221-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0016672300016037

- [127] A. Y. Lewin and H. W. Volberda, “Co-Evolution Dynamics within and between Firms: From Evolution to Co-Evolution,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 40. No. 8, 2003, pp. 2111-2136. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-6486.2003.00414.x

- [128] A. Parkhe, “Interfirm Diversity, Organisational Learning and Longevity in Global Strategic Alliances,” Bloomington, Indiana, 1991.

- [129] J. G. March, “Exploration and Exploitation in Organisational Learning,” Organisational Science, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1991, pp. 71-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

- [130] J. G. March, “The Future Disposable Organisations and Rigidities of Imagination,” Organisation, Vol. 2, No. 3/4, 1995, pp. 427-440.

- [131] T. K. Das and B. Teng, “The Dynamics of Alliance Conditions in the Alliance Development Process,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 39, No. 5, 2002, pp. 725-746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00006

- [132] R. Calori, M. Lubatkin, P.Very and J. F. Veiga, “Modelling the Origins of Nationally Bound Administrative Heritages: A Historical Institutional Analysis of French and British Firms,” Organisational Science, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1997, pp. 681-696. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.8.6.681

- [133] N. Kumar, “The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-Retailer Relationships,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 74, No. 6, 1996, pp. 92-106.

- [134] A. Arino and J. de la Torre, “Learning from Failure: Towards an Evolutionary Model of Collaborative Centures,” Organisation Science, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1998, pp. 306-325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.3.306

- [135] A. Arino, “Commentaries Building the Global Enterprise: Strategic Assembly,” Global Strategy Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1-2, 2011, pp. 47-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gsj.10

- [136] M. P. Koza , S. Tallman and A. Ataay, “The Strategic Assembly of Global Firms: A Micro Structural Analysis of Local Learning and Global Adaptation,” Global Strategy Journal, Vol. 1, No.1-2, 2011, pp. 27-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gsj.4

- [137] R. E. Hoskisson, M. A. Hitt, W. P. Wan and D. Yiu, “Theory and Research in Strategic Management: Swings of a Pendulum,” Journal of Management, Vol. 25, No. 3, 1999, pp. 417-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500307

- [138] T. Hafsi and H. Thomas, “The Field of Strategy: In Search of a Walking Stick,” European Management Journal, Vol. 23, No. 5, 2005, pp. 507-519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2005.09.006

- [139] B. Haugstad, “Strategy Theory: A Short Review of the Literature,” Kunne Nedtegnelse, SINTEF Industrial Management, 1999, pp. 1-10.

- [140] D. A. Kolb, “Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1984.

- [141] I. Lakatos and A. Musgrave, “Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1970.

- [142] R. Moussetis, “Ansoff Revisited: How Ansoff Interfaces with both the Planning and Learning School of Thought in Strategy,” Journal of Management History, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2011, pp. 102-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17511341111099556

- [143] V. Splitter and D. Seidl, “Does practice based research on strategy lead to practically relevant knowledge? Implications of a Bourdieusian perspective,” Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, Vol. 47, No. 1, 2011 pp. 98-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396322

- [144] G. Johnson, L. Melin and R. Whittington, “Micro strategy and strategizing: Towards an activity-based view,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2003, pp. 3- 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.t01-2-00002

- [145] G. Johnson, A. Langley, L. Melin and R. Whittington, “Strategy as Practice: Research Directions and Resources,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511618925

- [146] D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl and E. Vaara, “What Is Strategy-as-Practice? Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, pp. 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511777882.001

- [147] M. Kipping and L. Cailluet, “Mintzberg’s Emergent and Deliberate Strategies: Tracking Alcan’Sactivities in Europe, 1928-2007,” Business History Review, Vol. 84, No. 1, 2010, pp. 79-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007680500001252

- [148] D. J. Hall and M. A. Saias, “Strategy follows structure!” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1980, pp. 149-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250010205

- [149] J. D. Thompson, “Organisations in Action,” McGraw Hill, New York, 1967.

- [150] R. Feurer and K. Chaharbaghi, “Strategy Development: Past, Present and Future,” Management Decision, Vol. 33, No. 6, 1995, pp. 11-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00251749510087614

- [151] P. Anderson, “Complexity Theory and Organisational Science,” Organisational Science, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1999, pp. 216-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.3.216

- [152] W. M. Cohen and D. A. Levinthal, “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1990, pp. 128- 152. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- [153] K. D. Brouthers and J. F. Hennart, “Boundaries of the Firm: Insights from International Entry Mode Research,” Journal of Management, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2007, pp. 395- 425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300817

- [154] M. van Essen, P.J. Engelen and M. Carney, “Does good Corporate Governance Help in a Crisis? The Impact of Country and Firm-Level Governance Mechanisms in the European Financial crisis,” Corporate Governance: An International Review, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2013, pp. 201-224.

- [155] M. E. Porter, “Towards a dynamic theory of strategy,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. S2, 1991, pp. 95-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250121008

- [156] Y. J. Wind, “Positioning Analysis and Strategy,” In: G. Day, B. Weitz and R. Wensley, Eds., The Interface of Marketing and Strategy, JAI Press, Greenwich, 1990, pp. 387-412.

- [157] J. P. Bootz, “Strategic Foresight and Organisational Learning: A Survey and Critical Analysis,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 77, No. 9, 2010, pp. 1588-1594. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.06.015

- [158] G. B. Dagnino, “Bridging the Strategy Gap: Firm Strategy and Coevolution of Capability Space and Opportunity Space,” University of Pennsylvania Sol C. Snider Entrepreneurial Research Center Paper No. 306/2003, 2003. http://ssrn.com/abstract=684801

- [159] G. B. Dagnino and M. M. Mariani, “Dynamic Gap BridgIng and Realised Gap Set Development: The Strategic Role of the Firm in the Co-Evolution of Capability Space and Opportunity Space,” Innovation, Industrial Dynamics and Structural Transformation, Vol. 5, 2007, pp. 321-341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-49465-2_17

- [160] J. C. Casillas and F. J. Acedo, “Speed in the internationalisation process of the firm. International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2013, pp. 15-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00331.x

- [161] J. M. George and G. R. Jones, “The Role of Time in Theory and Theory Building,” Journal of Management, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2000, pp. 657-684.

- [162] A. M. Pettigrew, “What Is a Processual Analysis?” Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 13 No. 4, 1997, pp. 337-348 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00020-1

- [163] D. Barnes, “Research Methods for the Empirical Investigation of the Process of Formation of Operations Strategy,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 21, No. 8, 2001, pp. 1076-1095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005586

- [164] J. W. Fredrickson and T. R. Mitchell, “Strategic Decision Processes: Comprehensiveness and Performance in an Industry with an Unstable Environment,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1984, pp. 399-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/255932

- [165] C. Montgomery, B. Wernfelt and S. Balakrishnan, “Strategy Content and the Research Process: A Critique and Commentary,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, 1989, pp. 189-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100208

- [166] J. Child, “Organisational Structure, Environment and Performance: The Role of Strategic Choice,” Sociology, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1972, pp. 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/003803857200600101

- [167] V. K. Titus Jr., G. J. Covin and D. P. Slevin, “Aligning Strategic Processes in Pursuit of Firm Growth,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 64, No. 5, 2010, pp. 446-453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.03.003

- [168] A. Ziv, “Viewing Business Development Networks as Complex Adaptive Systems: Implications for Strategy Formation and Management’s Role,” 2004.Unpublished Report.

- [169] A. M. Pettigrew, “The Management of Strategic Change,” Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1987.

- [170] J. F. M. Swinnen and A. Vandeplas, “Market Power and Rents in Global Supply Chains,” Agricultural Economics, Vol. 41, Suppl. s1, 2010, pp. 109-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2010.00493.x

- [171] J. R. Dean and M. P. Sharfman, “Does Decision Process Matter? A Study of Strategic Decision-Making Effectiveness,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 2, 1996, pp. 368-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256784

- [172] O. Behling and N. L. Eckel, “Making Sense Out of Intuittion,” Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1991, pp. 46-54.