Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:42907,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.43019

Assessing the Readability and Usability of Online H-E-L-P Intervention for IPV Survivors

Rose E. Constantino1, Ayman M. Hamdan-Mansour2, Amanda Henderson3, Bonnie Noll-Nelson4, Willa Doswell5, Betty Braxter5

1Department of Community and Health Systems, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, USA

2Mental Health Nursing, Community Health Department, Faculty of Nursing, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

3University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, USA

4RN-BSN Department, Mount Aloysius College of Nursing, Cresson, USA

5Department of Health Promotion and Development, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, USA

Email: rco100@pitt.edu, a.mansour@ju.edu.jo, hendersona@upmc.edu, bnoll@mtaloy.edu, wdo100@pitt.edu, bjbst32@pitt.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 5 January 2014; revised 5 February 2014; accepted 15 February 2014

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the readability and usability of an online HELP (Health, Education, and Legal Program) intervention for women experiencing IPV (Intimate Partner Violence) by asking graduate nursing students to review in class nine online HELP intervention modules. Design: A descriptive online survey administered to 15 graduate nursing students was used to assess the readability and usability of an online HELP intervention. Methods: Participants were asked to perform the following activities: 1) reading the nine HELP modules on PowerPoint as posted on Blackboard (a web-based course management program), 2) filling in five blank lines under each heading (HEALTH, EDUCATION, LEGAL, and PROGRAM), by writing words or terms on the line after each heading, 3) ranking the words within each heading (with #1 as the highest and #5 as the lowest), 4) engaging in a class discussion of the rationale for the ranking, 5) re-ranking, and 6) voting on the ranking. The results were compiled to yield a master rank and vote order for each heading between 12 (received 12 votes) and 15 (received 15 votes) of the words that were ranked #1. Results: The words that were ranked #1 under each heading and the number of votes received were: Under HEALTH: Depression (15), Anger (14), Anxiety (13), and Pain (12); EDUCATION: Safety (15), Injury (14), Social Support (13) and Parenting/Child Care (12); LEGAL: Protection from Abuse (15), Attorney (14), Court/Hearing (13), and Rights (12); PROGRAM: Internet (15), Online (14), Intervention (13) and Resources (12). Conclusions: HELP intervention is readable and usable however, HELP needs to be piloted to ensure that survivors of IPV participants can access and benefit from HELP intervention.

Keywords:Intimate Partner Abuse; HELP

1. Background

As nurses care for women experiencing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) with a dearth of evidence-based interventions, we thought it fitting to provide students the experience in reviewing nine online intervention modules. IPV is a pervasive social and public health problem, resulting in millions of injuries and more than 1000 deaths in the US annually [1] [2] . In addition, medical and mental health care costs and other economic consequences of IPV exact a major financial toll on society exceeding $7 billion annually [3] [4] . IPV can include combinations of physical, psychological and emotional abuse and harassment perpetrated against a woman (85%) by a male who is a current or former intimate partner (boyfriend, fiancé, or spouse) [1] [5] -[8] . IPV is a complex pathologically synergistic system [9] [10] of a woman’s negative thinking, feelings, and behaviors. In addition, the perpetrator can isolate the survivor from family and friends, and deprive her of financial resources and sometimes her life [5] [6] [11] . The isolation of the survivor from family and friends poses a major barrier to reducing the burden of IPV sequelae [12] .

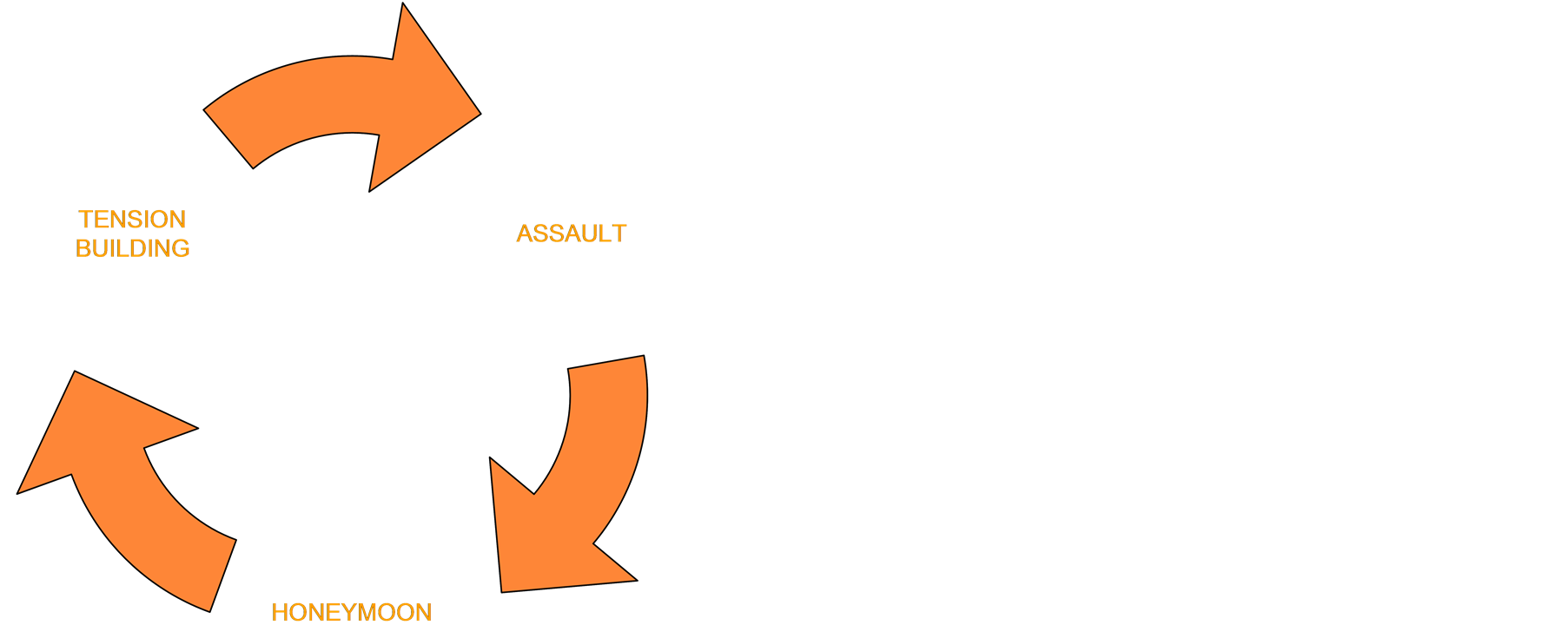

In spite of our knowledge of the health, safety, legal and social consequences of IPV, healthcare, legal and social service providers are unsure whether cost-effective online interventions could be developed and tested to reduce its consequences [13] . Women who survive IPV and do not seek help suffer physical, mental health, role fulfillment and psychological problems. The purpose of this study was to assess the readability and usability of an online Health Education and Legal Program (HELP) intervention designed to provide an integrated approach to support IPA survivors. Walker [14] describes three phases of IPV: tension-building, assault, and “honeymoon” defined as a phase of apparent calm and reconciliation following an episode of abuse (see Figure 1). Curnow [15] suggests that between the assault and the honeymoon phases, when the IPV survivor seeks protection from abuse, a window for help-seeking behavior is opened for her to seek help. However, the complexity of IPV and IPV intervention requires a Double Open Window of Empowerment (DOWE) that needs to be opened for both the survivor and healthcare or service provider. DOWE refers to the survivor being empowered through the decision-making process.

In developing HELP (Health, Education on safety Program) as an online intervention for IPA survivors, the Double Open Window of Empowerment (DOWE) served as the conceptual framework (see Figure 2). DOWE offers a double open window of empowerment; one for the survivor as she seeks help and another to empower

Figure 1. Walker’s cycle of intimate partner abuse.

Figure 2. The double window of empowerment for IPA survivors: A pictorial representation of the conceptual framework.

the service-provider through an online intervention that integrates health, education on safety program. The empowerment process is represented in the double open window allowing both survivor and service provider to share power with each other and with those within their circle [16] [17] .

HELP consists of eight modules delivered one week at a time for 8 weeks, including testing, review, and evaluation. Each module is presented in a standardized format: title, learning objectives, content, assignments, and contact information and is planned to be an accessible and cost-effective empowering online intervention for IPV survivors. HELP aims to empower both survivor and service provider in understanding the processes and consequences of the decision to seek Protection from Abuse (PFA) in court, enhance awareness of safe and dangerous behaviors, and exert control and autonomy over the decisions that affect lives [17] [18] .

2. Literature Review

IPV is a combination of physical, psychological and emotional abuse and harassment perpetrated against a woman (85%) by a male who is a current or former intimate partner (boyfriend, fiancé, or spouse) [1] [5] -[8] . IPV is a complex pathologically synergistic system [9] [10] of negative thinking, feeling, and behaviors perpetrated against a woman. In addition, the perpetrator can isolate the survivor from family and friends, and deprive her of financial resources and sometimes her life [5] [6] [11] [18] .

Medical and mental health care costs and other socioeconomic consequences of domestic abuse exact a major financial toll on society. The annual costs of IPV in the US are estimated to exceed $7 billion including more than $5 billion in medical and mental health care and nearly $2 billion in the indirect costs including expenses due to quality of life factors, lost earnings and productivity, and legal and educational costs [19] . IPV survivors had 60% higher rates of health problems than do women with no history of IPV [20] . Female survivors of IPA have been found to be restricted in gaining access to health, education, and legal services, take part in productive work, and social relationships [21] .

IPV survivors report 60% higher rates of health problems than do women with no history of IPA [22] . Female survivors of IPV have been found to be restricted in gaining access to health, education and legal services, take part in productive work and social relationships18. Women with a history of IPV are more likely to experience spells of unemployment, drop out of school, have health and legal problems, and become public assistance recipients [20] . They may also display behaviors that present further risks, such as substance abuse, alcoholism, and suicide attempts [22] .

Healthy People 2020 [23] acknowledge the urgency of reducing IPV by retaining from Healthy People 2010 the objective to reduce violence by current or former intimate partners. Also, the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s State Health Improvement Plan (SHIP) has aligned with Healthy People 2020 in prioritizing target objectives of leading health indicators for health action; “Violence and Injury” was ranked 4th among health indicators [24] [25] . Past research links occurrence and severity of multiple symptoms with impairments in functioning and quality of life in survivors of IPV [26] [27] . IPA has socioeconomic implications. Women with a history of IPV are more likely to experience spells of unemployment, drop out of school, have health and legal problems, and become public assistance recipients [18] . They may also display behaviors that present further risks, such as substance abuse, alcoholism, and suicide attempts [22] . Survivors of IPV lose a total of nearly 8 million days of paid work, the equivalent of more than 32,000 full time jobs and nearly 5.6 million days of household productivity each year [19] . Despite these disturbing statistics, IPV is one of the most underreported crimes, with only 40% of the general population reporting to authorities. However, approximately two-thirds of victims tell someone, often another person not a family member or police [19] . Telling someone albeit not a family member or police provides an opportunity for the healthcare or service providers to keep the double window of empowerment (DOWE) open through the HELP intervention.

3. Potential Advantage of Online Intervention

Online intervention allows survivors of IPV to access it in the privacy of their own home on their own time preference that is not currently practiced despite being sought by IPV survivors [28] -[30] . Furthermore, changed addresses, telephone numbers or relocation will not hamper continued HELP participation. Service and healthcare providers suggest that the effectiveness of an intervention for IPA survivors is enhanced by integrating advocacy services into a coordinated collaborative response including health, educational, and legal services but are unsure whether this integrated intervention can be delivered on line [27] . Survivors of IPV refrain from faceto-face social interactions due to feelings of stigmatization, shame, guilt, and alienation [1] . The Internet could, therefore, provides a protected environment where participants control and pace the degree of disclosure without the fear of face-to-face judgment, rejection, or devaluation [31] . Online intervention lessens social risks and inhibitions and enhances sharing of unwelcome thoughts and painful feelings [31] .

A legal intervention for IPV survivors is the Protection from Abuse (PFA). PFA is a court proceeding considered by service and healthcare providers as a positive step taken by the survivor toward safety and well-being [32] . However, seeking PFA places the survivor vulnerable to retribution and anger evoked in the abuser in response to the potential punishment during the temporary PFA, whether the Final PFA is granted or not by the court [28] [29] . The abuser may become angry due to potential punishment such as curtailment of basic freedoms, jail or exclusion from the residence. PFA may be temporary lasting 2 weeks or final lasting 6 months to 3 years. Furthermore, the community/public hears of the criminality of his behavior.

Other interventions focus only on the first window focusing on the survivor. Our challenge is to harness the power of the internet through HELP by offering a double open window of empowerment in facilitating online dialogue on health, education on safety and danger assessment, legal and social support with IPA survivors. HELP offers a Double Open Window of Empowerment for both survivor and for the nurse facilitator. The nurse facilitator uses online HELP as a tool to keep the window of empowerment open, allowing both survivor and service provider to share power and information with each other and with those within their circle [15] -[17] .

IPV is a pervasive national problem, where there is a gap in the research on interventions and resources for IPA [33] . A qualitative focus group study provided insight into the women experiencing IPA, particularly, utility, effectiveness, and accessibility of smartphones. The study results concluded that the smartphone is a feasible resource for women experiencing IPV [34] .

Safety, privacy, acceptability and utility need to be resolved when using a smartphone in this vulnerable population and must remain foremost to avoid unnecessary exposure to further harm (Lutz, 2009). IPV providers of care need to promote the therapeutic relationship, privacy and confidentiality for women with the use of technology. Smartphone supported interventions have shown a great deal of promise in other areas.

Once the abuse is identified, ongoing smartphone use may be a welcome resource and enhance outcomes with women living with IPV. Determining the feasibility of smartphone intervention will inform researchers about the usefulness, efficacy and cost of future efforts [34] , as well as consumer/client satisfaction. Women have shown a high degree of comfort with the smartphone as a mode of communication and education.

4. Methods

4.1. Design

A descriptive survey was conducted during a one 3-hour class period with two 7 - 10 minute breaks in between. The objective was to critique nine draft HELP modules and have the students respond to a brief survey. The nine HELP modules were posted on Blackboard as a reading assignment in preparation for this one class when the survey was administered.

4.2. Procedures

Fifteen graduate nursing students gave IRB-approved informed consent to participate in critiquing the nine draft HELP modules during class. It was emphasized that no aspect of their participation in the group would be graded and their decision to participate would not have any impact on their grade. The informed consent was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The survey sheet contained the following headings: health, education, legal, and program. Each heading was followed by five lines on which words or terms can be written. Participants were asked to perform the following activities: 1) reading the nine HELP modules on PowerPoint as posted on Blackboard (a web-based course management program), 2) filling in five blank lines under each heading (health, education, legal, and program), by writing words or terms on the line after each heading, 3) ranking the words within each heading (with #1 as the highest and #5 as the lowest), 4) engaging in a class discussion of the rationale for the ranking, 5) re-ranking, and 6) voting on the ranking. The results were compiled to yield a master rank and vote order for each heading between 12 (received 12 votes) and 15 (received 15 votes) of the words that were ranked #1.

HELP consists of nine modules delivered one week at a time for 12 weeks. Each module was presented and ranked words were integrated into the appropriate module. Module 1 was titled Thoughts, Emotions and Behaviors; Module 2 was Looking Through a Double Open Window; Module 3 Healing in Telling; Module 4 Relationships; Module 5 Health in HELP; Module 6 Education on Safety in HELP; Module 7 Legal Matters in HELP; Module 8 Acceptance, Balance and Competence; and Module 9 Seeing Through the Double Open Window of Empowerment.

5. Results

Each participant read aloud the words/terms they wrote after each heading and discussed the rationale for their ranking. A master ranking of words/terms under each heading was created. Only those words ranked #1 and received between 12 and 15 votes were included in the results as shown in Table 1. The words listed under each heading and the votes received were: HEALTH: Depression (15), Anger (14), Anxiety (13), and Pain (12); EDUCATION: Safety (15), Injury (14), Social Support (13) and Parenting/Child Care (12); LEGAL: Protection from Abuse (15), Attorney (14), Court/Hearing (13), and Rights (12); PROGRAM: Internet (15), Online (14), Intervention (13) and Resources (12). All participants offered suggestions and changes to the modules verbally or in writing.

6. Discussion

A systematic review of the literature on the use of interactive computerized intervention programs showed Internet-based interventions to be feasible and acceptable to participants in a wide variety of clinical and research populations and using a variety of technologies. In a feasibility study of a face-to-face group intervention among women who resided in shelters after obtaining PFA, several women requested to continue the intervention by email [25] [27] . To explore the preference of participants to continue the intervention by email, we tested an email intervention with six mother-child pairs after obtaining Protection from Abuse order [28] . A qualitative data analysis demonstrates that email was a feasible source of information, guidance and safety instructions [30] . Furthermore, our work with multiple sclerosis patients surviving IPA [35] and abused Jordanian women [36] - [38] calls for online intervention. However, computer skills and ownership could be barriers to HELP. Seeking permission for those without computers access to lab computers at the school of nursing should be explored. Providing the HELP user with a trained nurse facilitator to serve as a guide in online HELP is important. Training of HELP facilitators can be provided through clinical or course work or continuing education process.

The DOWE conceptual framework was seen by participants as proximately related to HELP albeit the relationship could be made clearer. Live examples of experiences between survivor and HELP facilitators should be presented as HELP is implemented. Further explanation of the DOWE is needed to both potential survivor and service provider if HELP intervention is to provide an opportunity to empower and to share power among survivor, healthcare or service provider and with those within their circle [15] -[17] . It may empower both survivor

Table 1. List of terms ranked #1 under each heading.

and service provider in understanding the processes and consequences of the decision to seek Protection from Abuse (PFA).

The terms listed under each heading for example, under HEALTH: Depression, Anger, Anxiety, and Pain; EDUCATION: Safety, Injury, Social Support and Parenting/Child Care; LEGAL: Protection from Abuse, Attorney, Court/Hearing, and Rights; PROGRAM: Internet, Online, Intervention and Resources could be conceptualized as risk factors in IPA with the exclusion of the terms under the PROGRAM heading. It was suggested that the acronym “P” (PROGRAM) in HELP needs to be changed to action word(s). We decided to change acronym “P” into “PP” in HELPP to stand for “Participant Preferred”. In this way, the participant or the survivor in HELPP intervention is included and her preference of the modality of HELPP intervention such as, Faceto-Face or Online is ascertained.

7. Conclusions

Online HELP is readable. The usability and feasibility of an online HELP intervention needs to be tested to ensure that potential participants can access and use the intervention. Each HELP module needs to be reviewed for clarity, simplicity, and brevity to reduce the burden on users. Online HELP intervention with IPA survivors as participants needs further refinement and testing. A pilot study on comparing the feasibility of HELP as an Online or Face-to-Face intervention could be suggested. Online HELP intervention once tested in a larger study and found effective should be shared with primary care providers, educators, and legal service providers. The words/ terms that were ranked number one under each heading need to be conceptualized and their measures explored. These words/terms should be conceptualized as risk factors in survivors of IPA. Further, the proximate relationship of DOWE as a conceptual framework with online HELP intervention needs to be explained. Pilot testing of HELP would allow for the refinement for its use in IPA survivors with co-morbidities and disabilities.

Computer skills and ownership could be barriers or opportunities to online HELP intervention. Providing those without computer access to school computer labs should be explored. Training of healthcare and service providers in online HELP intervention is important. Privacy and confidentiality should be protected and followup and referrals are crucial.

References

- Montalvo-Liendo, N., Wardell, D.W., Engebretson J. and Reininger, B.M. (2009) Factors Influencing Disclosures of Abuse by Women of Mexican Descent. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41, 359-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01304.x

- Saltzman, L.E., Fanslow, J.L., McMahon, P.M. and Shelley, G.A. (2002) Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008) Adverse Health Conditions and Health Risk Behaviors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence: United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57, 113-117.

- Tjaden, P. (2005) Defining and Measuring Violence against Women: Background, Issues, and Recommendations. Statistical Journal of the United Nations, 22, 217-234.

- Bracken, M.I., Messing J.T., Campbell, J.C. and LaFlair, L.N. (2010) Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse among Female Nurses and Nursing Personnel: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 137-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01612840903470609

- Campbell, J.C., Webster, D.W. and Glass, N. (2009) The Danger Assessment: Validation of a Lethality Risk Assessment Instrument for Intimate Partner Femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 653-674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317180

- Garcia-Moreno, C., Hansen, H., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L. and Watts, C. (2006) Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. Lancet, 368, 126-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8

- Rennison, M. (2003) Intimate Partner Violence, 1993-2001. In: Statistics BoJ, (Publication No. NCJ 197838): US Department of Justice, Washington DC.

- Constantino, R.E. and Crane, P.A. (2013) Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks and Models for Understanding Forensic Nursing. In: Constantino, R.E., Crane, P.A. and Young, S.E., Eds., Forensic Nursing: Evidence-Based Principles and Practice, F A Davis, Philadelphia.

- Hardin, S.K.R. (2005) Synergy for Clinical Excellence: The AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care. Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

- Campbell, J.C. (2002) Safety Planning Based on Lethality Assessment for Partners for Partners of Batterers in Treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 5, 129-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J146v05n02_08

- Campbell, J., Webster, D. and Glass, N. (2009) The Danger Assessment: Validation of a Lethality Risk Assessment Instrument for Intimate Partner Femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 653. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317180

- Krug, E.G., Dahlberg, L.L., Mercy, J.A., Zwi, A.B. and Lozano, R. (2005) World Report on Violence and Health. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Walker, L.E. (2000) The Battered Woman. Springer, New York.

- Curnow, S.A. (1997) The Open Window Phase: Help Seeking and Reality Behaviors by Battered Women. Applied Nursing Research, 10, 128-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0897-1897(97)80215-7

- Shearer, N.B.C., Fleury, J.D. and Belyea, M. (2010) Randomized Control Trial of the Health Empowerment Intervention. Nursing Research, 59, 203-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbbd4a

- Shearer, N.B.C. (2004) Relationships of Contextual and Relational Factors to Health Empowerment in Women. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 18, 357-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/rtnp.18.4.357.64094

- Bracken, M., Messing, J., Campbell, J., La Flair, L. and Kub, J. (2010) Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse among Female Nurses and Nursing Personnel: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 137-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01612840903470609

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) Costs of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in the United States. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/ipv_cost.html

- Campbell, J. (2002) Safety Planning Based on Lethality Assessment for Partners of Batterers in Treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 5, 129-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J146v05n02_08

- World Health Organization (2009) Reducing Violence through Victim Identification, Care and Support Programs. Violence Prevention: The Evidence.

- Coker, A.L., Smith, P.H., McKeown, R.E. and King, M.J. (2000) Frequency and Correlates of Intimate Partner Violence by Type: Physical, Sexual and Psychological Battering. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 553-559. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.4.553

- USDHHS (2009) Healthy People 2020. US Department of Human and Health Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington DC.

- Sirio, C., Zimmerman, R., May, J. and Burns, H. (2004) Pennsylvania Partners in Pursuit of Good Health: Building a Shared-Responsibility Model for State Health Improvement. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 10, 26-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00124784-200401000-00006

- PA Department of Health (2001) State Health Improvement Plan Harrisburg, 2001-2005, 18-19.

- McFarlane, J., Malecha, A., Gist, J., Watson, K., Batten, E. and Hall, I. (2004) Increasing the Safety-Promoting Behaviors of Abused Women. American Journal of Nursing, 104, 40-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200403000-00019

- Crane, P. and Constantino, R. (2003) Is Email Interaction Feasible for Intervention with Women and Children Exposed to Domestic Violence? A Literature Review. Advanced Practice Nursing, 3, 1-16.

- Constantino, R., Crane, P. and Kim, Y. (2005) Effects of a Social Support Intervention on Health Outcomes in Residents of a Domestic Violence Shelter: A Pilot Study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 20, 105-120.

- Holt, V.L. (2004) Civil Protection Orders and Subsequent Intimate Partner Violence and Injury. (No. NIJ 199722). National Institute of Justice, US Department of Justice, Washington DC.

- Constantino, R., Crane, P.A., Noll, B.S., Doswell, W.M. and Braxter, B. (2007) Exploring the Feasibility of Email-Mediated Interaction in Survivors of Abuse. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14, 291-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01080.x

- Litz, B.T., Engel, C.C., Bryant, R.A. and Papa, A. (2007) A Randomized Controlled Proof-of-Concept Trial of an Internet-Based, Therapist-Assisted Self-Management Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1676-1684.

- Holt, V.L., Kernic, M.A., Lumley, T., Wolf, M.E. and Rivara, F.P. (2002) Civil Protection Orders and Risk of Subsequent Police-Reported Violence. American Medical Association, 288, 589-594.

- Tjaden, P. and Thoennes, N. (2000) Extent Nature and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence; Finding from the National Violence against Women Survey. (NCJ Report No. 181867). National Institute of Justice, US Department of Justice, Washington DC.

- Noll-Nelson, B. (2011) Exploring the Feasibility of Smartphones as a Resource for Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence. Open Journal of Nursing, 2, 112-135.

- Tiwari, A., Fong, D.Y.T., Yuen, K.H., Yuk, H., Pang, P., Humphreys, J. and Bullock, L. (2010) Effect of an Advocacy Intervention on Mental Health in Chinese Women Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 304, 536-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1052

- Hamdan-Mansour, A., Constantino, R., Shishani, K., Safadi, R. and Bani-Mustafa, R. (2012) Evaluating Psychological and Mental Consequences of Abuse among Abused Jordanian Women. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 18, 205-212.

- Hamdan-Mansour, A., Constantino, R., Farrell, M., Doswell, W., Gallagher, M.E., Safadi, R., Shishani, K. and Banimustafa, R. (2011) Evaluating the Mental Health of Jordanian Women in Intimate Partner Abuse. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32, 614-623. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.580494

- Hamdan-Mansour, A., Arabiat, D., Sato, T., Imoto, A. and Obiad, B. (2011) An Investigation into Marital Abuse and Psychological Wellbeing among Women in the Southern Region of Jordan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22, 265- 273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1043659611404424