Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:28714,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.31004

Engagement in clinical learning environment among nursing students: Role of nurse educators*

![]()

Department of Adult Health and Critical Care, College of Nursing, Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman

Email: #melba123@rediffmail.com, ramesh@squ.edu.om, jayanthi@squ.edu.om, shreedev@squ.edu.om

Received 7 January 2013; revised 27 February 2013; accepted 1 March 2013

Keywords: Nursing Student Engagement; Clinical Learning Environment; Assessment; Learning Experiences; Nurse Educator; Student Centered Learning; Teaching-Learning Environment

ABSTRACT

Student engagement in a clinical learning environment is a vital component in the curricula of pre-licensure nursing students, providing an opportunity to combine cognitive, psychomotor, and affective skills. This paper is significant in Arab world as there is a lack of knowledge, attitude and practice of student involvement in the new clinical learning environment. The purpose of this review article is to describe the experiences and perspectives of the nurse educator in facilitating pre-licensure nursing students’ engagement in the new clinical learning environment. The review suggests that novice students prefer actual engagement in clinical learning facilitated through diversity experiences, shared learning opportunities, student-faculty interaction and active learning. They expressed continuous supervision, ongoing feedback, interpersonal relationship and personal support from nurse educators useful in the clinical practice. However, the value of this review lies in a better understanding of what constitutes quality clinical learning environment from the students’ perspective of engagement in evidence-based nursing, reflective practice, e-learning and simulated case scenarios facilitated by the nurse educators. This review is valuable in planning and implementing innovative clinical and educational experiences for improving the quality of the clinical teaching-learning environment.

1. INTRODUCTION

The quality of nursing education depends largely on the quality of the clinical experience planned in the nursing curriculum. In the clinical learning environment, there are varieties of influences that can significantly promote and hinder the clinical learning among novice students at the entry level. It is therefore vital that valuable clinical time be utilized effectively and productively as planned by the nurse educators. The birth of the baccalaureate nursing education in the Sultanate of Oman began with the baccalaureate nursing education at the College of Nursing (CON) Sultan Qaboos University in 2003. The BSN nursing education program was established to meet the growing health care demands and needs of the community. The nursing program incorporated the goal of the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses is to address the challenge of preparing future Omani nurses with the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to continuously improve the quality and safety of the healthcare systems in Oman [1]. Six competencies were included related to patient centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, informatics and safety for use in the nursing pre-licensure program [2, 3].

The nursing curriculum was built in line with the international nursing standards incorporating core/basic, specialty, complementary, advanced courses with residential practice for preparing professional Omani nurses. Students enrolled in the BSN program at the CON enter clinical practice in the Adult Health Nursing clinical course. They enter various clinical settings in the hospital and are exposed to various socio-cultural, racial-ethnic and psychosocial aspects of patients. It is a challenge for many student nurses to imbibe the various roles of the nurses in the clinical setting while learning new clinical concepts and application of these in nursing practice. The entry in the new clinical environment has been described as a place where nursing students go through intense emotional experiences (reality shock). Students have described entering the clinical arena as though they were being “thrown in at the deep end”. Boshuizen (2010) highlighted that the “shock of practice”, a crisis experienced by many nursing students on first entering the clinical workplace, is marked by a temporary decrease in their ability to properly incorporate basic biomedical science knowledge into their clinical reasoning [4]. Inherently, clinical learning becomes a stressful event for students exposed to the new clinical environment.

2. BACKGROUND

Engaging students in the teaching-learning process has been shown to improve the development of critical thinking skills [5], enhance openness to diversity, facilitate openness to challenge [6], among other important learning outcomes. Student engagement (SE) is fostered by pedagogical practices that encourage experiential learning, develop connections with the nursing curriculum, and promote student inquiry in the clinical environment. SE can be defined as students’ willingness to actively participate in the clinical learning process and to persist despite obstacles and challenges in the clinical environment. SE is the “the extent of students’ involvement and active participation in clinical learning activities” [7].

A supportive clinical learning environment (CLE) is vital to the success of the teaching learning process. Many nursing students perceive their clinical learning environment as anxiety and stress provoking. Clinical learning experience requires difficult adjustments for students as they come from different socio-economic and cultural background [8]. Nursing students feel vulnerable in the clinical learning environment, so it’s not surprising that learning in the clinical area presents a bigger threat to students than learning in the classroom. Student activities are unplanned in the clinical area [9] and not all practice settings are able to provide student nurses with a positive learning environment [10,11].

Many of the current innovate educational and teaching technology has been adapted by the nurse educators for the novice nursing students in the clinical practice. However there are no reviews describing the process of student engagement in the new clinical learning environment in the Middle East and Gulf countries. This review paper explores the clinical experiences and perspectives of nurse educators regarding student engagement through diversity experiences, shared learning opportunities, student-faculty interaction and active learning in Oman. Faculty have incorporated simulated case scenarios, evidence-based practice, e-learning (moodle), student portfolio and reflective practice while engaging students in the clinical learning environment. These experiences help nursing students to critically think and link theoretical concepts to clinical application through the use of real world examples, collaborative activities, synthesizing and analyzing information, discussion and presentation activities for transfer of knowledge that contribute to clinical learning.

3. AIM

The aim of this paper is to explore nursing student’s engagement in the new clinical learning environment through diversity experiences, shared learning opportunities, student-faculty interaction and active learning contributing to effective learning.

4. CONCEPTUAL MODEL

We have used a combined conceptual framework based on Kember (2005), Kolb (1984) and a Social constructivism approach [12-14]. The social constructivist model emphasizes the importance of the relationship between the student and the instructor in the learning process. These learning approaches harbour this interactive learning through reciprocal teaching, peer collaboration, problem-based instruction, web quests, anchored instruction and other approaches that involve learning with others [15].

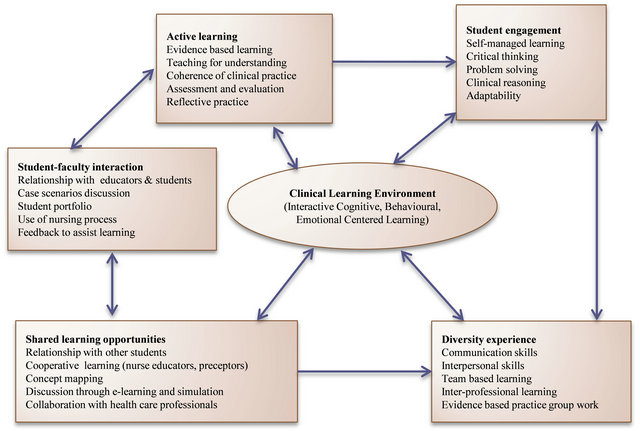

Student’s clinical experiences in the Adult Health and Critical Care Nursing (AHCCN) clinical courses, perspectives and knowledge of the nursing student’s level of understanding, interest, motivation, cultural norms, values, preferences and learning styles have helped to plan, engage and evaluate them in the clinical learning environment (Figure 1). Five clinical teaching-learning strategies, i.e., simulated case scenarios using METI ECS 100, evidence based teaching learning projects, e-learning through Moodle management software using interactive chats, forums and quizzes, student portfolio and reflective practice were used from 2009-2012. Nursing students in the clinical settings are oriented and assigned to a patient for comprehensive evidence based nursing care. They asked to observe, assess, plan, implement and evaluate the patient using the nursing process and applying the six nursing competencies. They identify problems encountered in nursing care, have clinical discussions using concept mapping, develop critical thinking and clinical reasoning, correlate and integrate nursing process to address the nursing management strategies for the patient. These students engage in finding answers to clinical questions, become active and co-operative learners and are motivated to learn through real life experiences, case scenarios and evidence based practice.

In our conceptual framework the nurse educator and the student in the clinical settings are equally involved in learning from each other which is also affected by their culture, values and background throughout the learning

Figure 1. Relationship between student engagement and clinical learning environment (Modified Kember 2005, Kolb 1984).

process. This also shapes the knowledge and truth that the student and nurse educator creates, discovers and attains in the clinical learning process. This becomes an essential part of the interplay between nurse’s educators and the interactive learning experiences. Students compare their version of the truth with that of the nurse educator and peers to get to a new, clinically tested version of truth. This creates a dynamic interaction between the clinical task, nurse educator and the student. The students and the nurse educators develop an awareness of each other’s perspectives and viewpoints and then look to their own beliefs, standards and values, thus being both subjective and objective at the same time.

Hurst notes that “the time students spend with patients should be devoted entirely to the patient. Each patient is unique, and what each says and reveals must be listened to and studied carefully’’. The role of the nurse educator in engaging students in the clinical learning environment occurs through use of various learning styles using cognitive, behavioural and emotional dimensions of higher thinking. The use of active learning, shared learning opportunities, faculty-student interaction and diverse experiences through various channels or means of teachinglearning involves student centered learning. The Kolb learning cycle links concrete experience (clinical experiences) with abstract conceptualization (learning process) through reflection and planning. The use of the learning principles and learning styles helps the nurse educators in facilitating students learning and sustaining an interest in clinical learning in the new environment.

5. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The clinical learning environment (CLE) is a multidimensional entity with a complex social context. The quality of student-educator interactions in the clinical learning environment showed that, while two-thirds of the educators were regarded as friendly and helpful, the rest were perceived as unconcerned and hostile [10]. There were significant differences between student’s perception of actual clinical learning environment with and preferred clinical learning environment [16].

Ramsden gives six key principles of effective teaching in clinical education, of which the fifth (1992) is “independence, [student] control, and active engagement” [17]. He believes that a deep approach is encouraged by “teaching and assessment methods that foster active and long-term engagement with clinical learning tasks” [18]. High motivation and engagement in clinical learning have consistently been linked to increased levels of student’s academic success in a variety of ways [19-22]. Engaged students earn better grades and exhibit increased practical competence along with the ability to transfer their skills to new situations [23]. Carini, Kuh, and Klein (2006) examined the different forms of student engagement associated with learning outcomes based on the RAND tests, college GPA, and the essay prompts on the GRE. RAND researchers administered NSSE and the RAND cognitive tests to 1352 students at 14 four-year colleges and universities [24]. There is a positive relationship between student engagement and learning outcomes such as critical thinking and grades.

In a number of studies student engagement has been identified as a desirable student centered approach in the clinical learning system/process of education [25,26]. It has been used to depict students’ willingness to participate in clinical activities, such as attending clinical training, submitting assignments and student oriented activaties [27,28]. [Students] who are engaged show sustained behavioral involvement in clinical learning activities accompanied by a positive emotional tone [29]. Studentstudent and student-faculty interaction in the clinical learning environment are the two major influences on course effectiveness [30]. Student participation in clinical, teacher encouragement, and cooperative studentstudent interaction contributes to developing critical thinking skills and integrating knowledge in practice [31]. A review of over 305 studies conducted since 1960 provides insights into the impact of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning on individual achievement in clinical settings. The results of 168 studies focusing on the type of learning and academic achievement found that cooperative learning promotes higher individual achievement than do competitive approaches [32].

Good practices in clinical education are ones that: encourage student-faculty contact, develop reciprocity and cooperation among students, encourage active learning, provide students with prompt feedback, emphasize time on task, communicate high expectations and respect diverse talents and ways of knowing [29,33]. Recognizing these interactive dynamics, we integrate various theoretical perspectives to explain how students engage in clinical learning practice. Thus meaningful clinical learning occurs when students are actively engaged with a variety of clinical learning tasks. The literature review used for this paper reflects the idea that positive clinical learning environment is essential for enhancing clinical learning among students in the nursing education.

6. ROLE OF THE NURSE EDUCATOR IN IMPROVING STUDENT ENGAGEMENT IN THE CLE

According to the nursing students, engagement in clinical environment is intense yet enjoyable motivating them to learn and develop analytical reasoning skills. Some students reported experiencing stress due to deficiencies in basic science knowledge and in their ability to apply it in the clinical setting. Deficiencies in anatomy, pharmacology, physiology, pathophysiology and the interpretation of diagnostic results were mentioned by some of these students. The patient contacts in the clinical setting were considered to be instrumental for clinical learning in the adult health and critical care courses. Students acknowledged that nursing process proved to be easier learnt from real patients than from textbooks. It was found that transferring knowledge and the effectiveness of clinical teaching strategies lies in facilitating student engagement through promoting diversity experiences, creating shared learning opportunities, maximizing student-faculty interaction, involving students in active learning, and setting high expectations [34].

Diversity Experiences. The unique clinical learning atmosphere afforded to these students in the Adult health and critical care clinical courses was rich in cultural diversity (using communication, inter-personal skills and team based learning). It enhanced the likelihood that they engage in interactions and learning opportunities with a broadened worldview through inter-professional learning and evidence based learning. These students reported an increase in drive to achieve, intellectual engagement, and thinking complexity with greater diversity experiences. An increasing body of literature focuses on the influence of student involvement in diversity experiences on cognitive development and learning engagement. Students’ involvement in diversity experiences promoted their growth in engagement, motivation, and active, complex thinking (e.g. enjoy analyzing reasons for behavior; prefer complex rather than simple explanations). Clinical experiences such as addressing diversity issues in clinical, engaging in diversity discussions with peers and attending various clinical events helped to shape students’ cognitive development [35,36].

Shared-Learning Opportunities. Collaborative techniques used in the AHCC clinical courses have shown to positively impact student engagement through the use of case scenario, evidence based practice, e-learning, student portfolio and simulation. They built working relationships with peers and staff nurses, preceptors and the nurse educators and initiated collaboration with health care professionals. Clinically relevant strategies promoted deeper integration and reorganization of new and existing clinical knowledge, resulting in substantial gains for the student clinical learning and engagement outcomes. An accumulation of research has documented the positive impact of collaborative, shared-learning experiences on student engagement and development [27,30, 37,38]. Collaborative learning redefines the learning experience as a social construction of knowledge and is required to work together to identify, explore, and analyze issues related to the case they are presented, and through the use of peer teaching, must reach a solution for their case problem [39]. They encourage students to think deeply about course material and to develop a shared knowledge through the presentation of unique perspectives among peers. Students involved in these strategies reported increased engagement in self-directed clinical learning activities, critical reasoning processes, and conveyed that their learning was more dynamic and active compared to the learning experienced in conventional curricula [37]. Students engaged in these clinical strategies reported thinking about course material more deeply than when in conventional courses, where often the primary aim is to memorize material [40].

Student-Faculty Interaction. Student-faculty interaction integrates students more deeply in the clinical courses using case scenarios, concept mapping, and feedback to assist learning. Related to student engagement, nurse educators interaction predicted improved development of problem-solving skills (i.e., seeking the best possible clinical answer even if it takes a long time; seeking knowledge for its own sake) and facilitated progress toward intellectual goals (i.e., acquiring skills for self-directed learning; acquiring abilities to raise clinical questions), while also improved satisfaction with the clinical environment. To promote engagement in the clinical courses, the nurse educators are available and accessible to students, and not solely for discussing an upcoming clinical evaluation or exam—but also to interact with students on a personal level. They show a willingness to informally discuss a broad range of clinical nursing topics that will help students grow both intellectually, and personally. Faculty does not only mentor students who are satisfied in the clinical settings, but also heightened students’ desire to engage in their clinical environment.

Active Learning. Examples of active learning practices included in the clinical courses are comprehensive care, writing case study papers; reflective practice, searching for evidence based references; completing clinical assessments that measure clinical decision making abilities, problem based interests, developing attitudes; summarizing or outlining major points from clinical readings or notes; participating in clinical discussions; and reading clinical articles or references that are frequently cited by other nursing and clinical authors. Thus, to promote student engagement in the clinical, the nurse educator used teaching for learning and coherence to clinical practice while incorporating clinical activities that required students to utilize active learning strategies [41,42]. Active learning is considered an essential practice for producing valued outcomes in clinical education [29]. Active learning increases in three important educational practices: student-faculty interaction, cooperation among students, and active learning which influenced intellectual and educational gains. Involvement in active learning accounted for more variance in student gains than did either of the other two practices. Increased active learning was associated with a greater ability to pursue ideas independently, a greater ability to find and synthesize information, greater interest in broadening one’s general education, and more desire to learn on one’s own [41].

Students enrolled in the AHCCN clinical reported greater involvement in course activities, writing activities, engaged more frequently with faculty and peers, and spent more time in the library than did students enrolled in conventional courses. Students reported spending more time outside of clinical with senior students conversing about clinical assignments and carrying on clinical course-related discussions that have originated in the clinical with the peers. Thus, not only did SE lead students to become more involved in clinical activities, but it also lead them to engage more deeply intellectually in and out of the clinical. Student satisfaction was less in the context of clinical learning environment [42,43]. Inter personal relationship among nursing students in the clinical learning environment is crucial to the development of positive learning environment [16]. 67% of the students expressed that encouragement and motivation from the teachers enhances the clinical learning [44,45].

Student engagement in clinical learning will enhance their effectiveness of learning and promote higher learning abilities [30]. It improves critical thinking, problem solving and clinical reasoning and adaptability to clinical situation. These strategies include creating clinical assignments that challenge students to seek answers beyond those presented in their basic textbook; ensuring that thought-provoking clinical discussions and debates are a normal clinical occurrence; asking students to generate a bibliography or annotated bibliography of references on a particular clinical topic that they may use in a later paper; or incorporating summary clinical assignments in which students are required to synthesize and integrate important clinical concepts from assigned readings. Such active learning practices should enhance students’ proclivity to engage in their clinical learning experience. Researchers have identified several domains for which student engagement has been shown to make a difference in student outcomes, including the development of cognitive and intellectual skills, adjustment to college resulting in high rates of retention, personal growth and psychosocial development, as well as longterm benefits extending well beyond the college years [23,30].

7. CONCLUSIONS

Maximizing student engagement is critical to achieving clinical learning outcomes considered central to the clinical curriculum in the undergraduate nursing education. The nurse educator’s vast experience in guiding or teaching nursing students in the clinical settings will provide a foundation for further studies in the area and will definitely contribute to the existing source of knowledge in this field. These studies will further be helpful in improving the students learning and future of teaching in the nursing education in Muscat. Students learning experiences in the clinical environment determine their short and long term commitment and responsibility in the nursing practice and are vital to the preparation of future qualified nursing professionals in Oman. The effectiveness of learning is closely linked to the quality of the teaching and the practicum component. Knowledge of how students cope with practicum stresses would have the benefit of informing teacher education programs of the most effective ways of providing them support. Nurse educators with sufficient training, facilitate professional development, and provide regular help instead of focusing on formative or summative student evaluation only. The nurse educators are a link between the clinical environment and the student for imparting quality clinical teaching. They need to work as a harmonious team for implement effective clinical learning procedures and create professional working relationships. Student engagement in the clinical courses have shown to play an important role in the acquisition of critical thinking skills and other cognitive abilities [5], the development of cognitive and intellectual skills [46], the acquisition of knowledge and the development of problem solving skills [32].

For successful SE, these clinical centered strategies include cognitive, conative, psychomotor and perceptional domains, blended with acquisition of life skills taught and learnt. Innovative clinical teaching-learning methods can highly motivate the students to be actively engaged, de-stress and improve bedside learning. The overarching goal of SE in the CLE is to enrich clinical learning experiences and prepare competent graduate student nurses with transfer of knowledge and practice for any health care setting. This shows that students develop self-awareness, critical thinking, and a new perspective through synthesis and evaluation. In this paper we addressed the roles of promoting diversity experiences, introducing shared-learning opportunities, maximizing student-faculty interaction, generating active learning, and setting high expectations and how they contribute to student engagement in the clinical learning environment. As the nursing profession is undergoing continuous evolution in Oman, to hold on during these changes the nursing students should be provided with an effective clinical learning environment to enhance the quality of nursing education. The success of clinical learning is largely dependent on clinical learning environment, or more poetically “the soul and spirit of nursing education”.

8. IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSE EDUCATORS

As elements of clinical environment can influence the student learning, integration of clinical learning should be threaded in the curriculum with educational interventions if appropriately conceived and implemented can and will make a difference. Provision of an effective clinical learning environment to nursing students is crucial in enhancing quality-based nursing practice. There should be ongoing educational research upon factors that characterize clinical learning environment which is beneficial in improving clinical learning. Nurse Administrators should take initiative in providing clinical placements for students to have an effective clinical learning environment that characterizes their clinical objectives and outcome measures.

Nurse educators can incorporate student’s engagement strategies in the clinical courses, implement and evaluate them for their effectiveness. Involving students in the teaching strategies (mentored seminar) and evaluation (peer review) helps to build confidence in the students to practice engagement. Balancing student’s clinical activities and clinical assignments helps to avoid stress among the students. Providing range of clinical activities with learning options to cater to various level of understanding among the students is also effective. Appreciating the individual difference and acknowledging reactive, proactive or controversial natures of expression [47]. Supporting with multidimensional resources to make the student involvement adequate in the clinical setting is helpful [46]. Orienting to the course objectives and expected learning tasks of the students are reinforced. Group students for reflective activities and promote learning as nature of the group will influence the learning [46,48]. Create an atmosphere to enable students to learn, ensure students know what is expected of them and give them the opportunity to learn by doing, where they can give feedback from their peers and lecturer in a safe and supportive environment [49].

Student engagement can be achieved by identifying the means of how to get engaged and the balance between the engagement and academic load. Stay connected with clinical course objectives and the nurse educator’s interaction with the student. Familiarize with the course requirements, standards and needs. Empower each student and propel the SE concept in the right direction in the new CLE. The coherence between the clinical assignment and accountability of the student differs from one to another and it will be reflected on the achievement of clinical learning objectives. Nurse educators have immense experience in engaging students in the real practice and effective teaching-learning strategies can be used to reduce the gap in theory-practice and bridge the differences. Simulated case scenarios, evidence based practice, e-learning via Moodle management, student portfolio and reflective practice can be introduced at various stages with learning objectives for various clinical. Student engagement is not only an effective clinical learning component of the curriculum but also helps to evaluate the curriculum for improving the quality of nursing education.

• 9. WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

• Transferring knowledge through diverse experiences and shared learning opportunities promotes student engagement.

• Meaningful, intellectual and concrete learning experiences lead to active learning among students in the clinical environment.

• Faculty-student interaction and working together enhance student outcomes in the new clinical learning environment.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Quality and safety education for nurses (2012) Overview. http://qsen.org/about/overview/

- Hickey, M.T., Forbes, M. and Greenfield, S. (2010) Integrating the institute of medicine competencies in a baccalaureate curricular revision: Process and strategies. Journal of Professional Nursing, 26, 214-222. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2010.03.001

- Cronenwett, L., Sherwood, G., Barnsteiner, J., Disch, J., Johnson, J., Mitchell, P. and Warren, J. (2007) Quality and safety education for nurses. Nursing Outlook, 55, 122- 131. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2007.02.006

- Boshuizen, H.P.A. (1996) The shock of practice: Effects on clinical reasoning. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York, 8-14 April 1996, 47.

- Pascarella, E.T., Palmer, B., Moye, M. and Pierson, C.T. (2001) Do diversity experiences influence the development of critical thinking? Journal of College Student Development, 42, 257-271.

- Pascarella, E.T., Cruce, T., Umbach, P.D., Wolniak, G.C., Kuh, G.D., Carini, R.M., Hayek, R.M. and Zhao, G.C. (2006) Institutional selectivity and good practices in undergraduate education: How strong is the link. Journal of Higher Education, 77, 251-285. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0016

- Cole, P.G. and Chan, L.K.S. (1994) Teaching principles and practice. Prentice Hall, New York.

- Campbell, I.E. (1994) Learning to nurse in the clinical setting. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20, 1125-1131. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20061125.x

- Massarweh, L.J. (1999) Promoting a positive clinical experience. Nurse Educator, 24, 44-47. doi:10.1097/00006223-199905000-00016

- Harth, S.C., Bavanandan, S. and Thomas, K.K. (2009) The quality of student tutor interaction in clinical learning environment. Medical Education, 26, 321-326. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00176.x

- Dunn, S.V. (2007) Undergraduate nursing students perception of their clinical learning environment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 1299-1306. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251299.x

- Kember, D. (2009) Promoting student-centered forms of learning across an entire university. High Education, 58, 1-13. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9177-6

- Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Eggen, P. and Kauchak, D. (2004) Educational psychology: Windows, classrooms. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- Giddens, J., Brady, D., Brown, P., Wright, M., Smith, D. and Harris, J. (2008) A new curriculum for a new era of nursing education. Nursing Education Perspectives, 29, 200-204.

- Chan, D.S. (2001) Development of the clinical learning environment inventory. Using the Theoretical Framework of Learning Environment Studies to Assess Nursing Students’ Perceptions of the Hospital as a Learning Environment, 41, 69-75.

- Ramsden, P. (1992) Learning to teach in higher education. Routledge, New York. doi:10.4324/9780203413937

- Ramsden. P. (1994) Using research on student learning to enhance educational quality. In: Gibbs, G., Ed., Improving Student Learning—Theory and Practice, Oxford Centre for Staff Development, Oxford.

- Black-Branch, J.L. and Lamont, W.K. (1998) Essential elements for teacher wellness: A conceptual framework from which to study support services for the promotion of wellness among student and preserve nurse educators. Journal of Collective Negotiations, 22, 243-261.

- Dev, P.C. (1997) Intrinsic motivation and academic achievement: What does their relationship imply for the classroom teacher? Remedial and Special Education, 18, 12-19. doi:10.1177/074193259701800104

- Kushman, J.W., Sieber, C. and Heariold-Kinney, P. (2000) This isn’t the place for me: School dropout. In: Capuzzi, D. and Gross, D.R., Eds., Youth at Risk: A Prevention Resource for Counselors, Nurse Educators, and Parents, 3rd Edition, American Counseling Association, Alexandria.

- Wood, R.E., Mento, A.J. and Locke, E.A. (1987) Task complexity as a moderator of goal effects: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 416-425. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.72.3.416

- Kuh, G.D., Pace, R. and Vesper, N. (1997) The development of process indicators to estimate student gains associated with good practices in undergraduate education. Research in Higher Education, 38, 435-454. doi:10.1023/A:1024962526492

- Carini, R.M., Kuh, G.D. and Klein, S.P. (2006) Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47, 1-24. doi:10.1007/s11162-005-8150-9

- Biggs, J.B. (1999) Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does? Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, Buckingham.

- Kember, D. (2005) Best practices in outcomes based teaching and learning at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Centre for Learning Enhancement and Research. http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/clear

- Cabrera, A., Crissman, J., Bernal, E., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. and Pascarella, E.T. (2002) Collaborative learning: Its impact on college students’ development and diversity. Journal of College Student Development, 43, 20-34.

- Windsor, A. (1987) Nursing student’s perception of clinical experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 26, 150- 155.

- Chickering, A.W. and Gamson, Z.F. (1987) Seven principles for good practice. AAHE Bulletin, 39, 3-7.

- Astin, A. (1993) What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

- McKeachie, W.J. (1996) Student ratings of teaching. American Council of Learned Societies Occasional Paper No. 33. http://www.acls.org/op33.htm#McKeachie.

- Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R. and Smith, K. (1998) Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Interaction Book Company, Edina.

- Tanner, C.A. (2006) The next transformation: Clinical education. Journal of Nursing Education, 45, 99-100.

- Godefrooij, M.B., Diemer, A.D. and Scherpbie, A.J.J.A. (2010) Students’ perceptions about the transition to the clinical phase of a medical curriculum with preclinical patient contacts; a focus group study. BMC Medical Education, 10, 28. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-10-28

- Gurin, P. (1999) The compelling need for diversity in education. Expert report. http://www.umich.edu/~urel/admissions/legal/expert/gurintoc.html

- Haas, B.K., Deardorff, K.U., Klotz, L., Baker, B., Coleman, J. and Dewitt, A. (2002) Creating a collaborative partnership between academia and service. Journal of Nursing Education, 41, 518-523.

- Cockrell, K.S., Caplow, J.A.H. and Donaldson, J.F. (2000) A context for learning: Collaborative groups in the problem-based learning environment. The Review of Higher Education, 23, 347-363. doi:10.1353/rhe.2000.0008

- Tinto, V. (2005) Moving from theory to action. In: Seidman, A., Ed., College Student Retention: Formula for Student Success, ACE & Praeger, Washington DC.

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Bernstein, P., Tipping, J., Bercovitz, K. and Skinner, H.A. (1995) Shifting students and faculty to a PBL curriculum: Attitudes changed and lessons learned. Academic Medicine, 70, 245-247. doi:10.1097/00001888-199503000-00019

- Koh, L.C. (2002) The perceptions of nursing students of practice-based teaching. Nurse Education in Practice, 2, 35-43. doi:10.1054/nepr.2002.0041

- Dunn, S.V. and Hansford, B. (1997) Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of their clinical learning environment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 1299-1306. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251299.x

- Hart, G. and Rotem, A. (1995) The clinical learning environment: Nurses perceptions of professional development in clinical settings. Nurse Education Today, 15, 3- 10. doi:10.1016/S0260-6917(95)80071-9

- Saarikoski, M. (2002) Clinical learning environment and supervision: Development and validation of the CLES evaluation scale. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Turku, Turku.

- Saarikoski, M. and Leino-Kilpi, H. (2002) The clinical learning environment and supervision by staff nurses: Developing the instrument. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39, 259-267. doi:10.1016/S0020-7489(01)00031-1

- Ewan, C. and White, R. (1996) Teaching nursing. 2nd Edition, Chapman and Hall, London.

- Quinn, F.M. (2000) Principles and practice of nurse education. 4th Edition, Nelson Thornes Limited, Cheltenham.

- Reece, I. and Walker, S. (2000) Teaching, training and learning a practical guide. 4th Edition, Business Education Publishers Limited, Sunderland.

- Oliver, R. and Endersby, C. (1994) Teaching and assessing nurses: A handbook for preceptors. Baillière Tindall, London.

NOTES

*Authors’ contributions: all authors drafted the manuscript, critical appraised and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

#Corresponding author.