Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications

Vol.06 No.03(2016), Article ID:67129,11 pages

10.4236/jcdsa.2016.63014

Treatment of Acute Cutaneous Leishmaniasis by Oral Zinc Sulfate and Oral Ketocanazole Singly and in Combination

Khalifa E. Sharquie1,2*, Adil A. Noaimi1,2, Wasnaa S. Al-Salam3

1Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

2Iraq and Arab Board for Dermatology & Venereology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq

3Department of Dermatology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 3 May 2016; accepted 3 June 2016; published 6 June 2016

ABSTRACT

Background: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is an endemic disease in many countries and caused by different species of Leishmania parasite. It results in a deformed scar after a relatively long period. Many therapies have been tried in treatment of this disease. Objective: To compare the effect of oral zinc sulfate and oral ketoconazole singly and in combination in the treatment of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. Patients and Methods: This single, blinded, therapeutic, controlled study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq, during the period, January 2015 to July 2015. Seventy-five patients with acute CL were enrolled in this study. The total numbers of lesions were 327, and the duration of lesions ranged from 4 to 12 (6.9 ± 0.7) weeks. The diagnosis was confirmed by smear and histopathology. Patients were divided into three groups: 24 patients in Group A were treated with oral zinc sulfate capsules 10 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks; 24 patients in Group B were treated with ketoconazole tablets 200 mg twice daily for 6 weeks and 27 patients in Group C were treated orally with a combination of zinc sulfate and ketoconazole for 6 weeks. All patients were seen regularly every 2 weeks for 6 weeks of treatment period, then monthly for the next three months as follow up period. Healing of the lesions was assessed by using Sharquie’s modified Leishmania score to assess the objective response to the topical or systemic therapy. Results:After six weeks, 75 patients have completed the treatment, 24patients received zinc sulfate capsule, 24 patients received oral ketoconazole and 27 patients received a combination of both treatments. The cure rate was (60%) in the group receiving oral zinc sulfate capsuleand (50%) in the one receiving oral ketoconazole tablet (P = 0.146) and (96%) in the combination group (P ˂ 0.04). Conclusion: The combination therapy using oral zinc sulfate and oral ketoconazole gave a high cure rate. The combination therapy is a new mode of therapy as both drugs act in a synergistic way.

Keywords:

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, Ketoconazole, Zinc Sulfate, Sharquie’s Modified Leishmania Score

1. Introduction

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is caused by different species of Leishmania with specific inclination of each species to a particular geographical region. It is endemic in 88 countries including Iraq, Iran, Brazil, Afghanistan, Peru, Sudan and Syria. It has afflicted 12 million people with 1 - 1.5 million new cases each year, putting 350 million people at risk. It is becoming a global problem with increasing incidence due to immigration and travel [1] . Hyperendemicity of leishmaniasis in Iraq has made it an important health problem and demanding high annual expenses when it is running in an epidemic state. Although cutaneous leishmaniasis is a self-limiting disease, its healing takes months to years and in some cases it becomes chronic. On the other hand, healing is associated with a deformed ugly scar [2] . Despite multiple treatment suggestions for cutaneous leishmaniasis, pentavalent antimony compounds are used as first-line treatment [3] ; however, due to their serious potential side effects including cardiac, hepatic and blood toxicity, pancreatitis, increased cases of clinical response failure [4] , high prices, lack of production technology in many of the developing endemic countries and prolonged treatment period, and the emergence of new species. There are strong efforts for finding an effective treatment with less side effects and more acceptable for patients. In many studies, oral zinc sulfate has been reported to be effective in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis and Sharquie et al. was the first researcher that has confirmed its effectiveness in acute and chronic Leishmania [5] - [7] and this study was followed by others like Firooz A. et al. [8] . Ketoconazole is a well known antifungal drug that was tried during the 1980s with limited success [9] . So the aim of the present work is to compare the use oral zinc sulfate and oral ketoconazole in the treatment of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis singly and in combination.

2. Patients and Methods

This case controlled, single, blinded, therapeutic study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Baghdad Teaching Hospital, Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq from January 2015 to July 2015. A total of 75 patients with acute CL were enrolled in this study. A history was taken from each patient regarding the followings: age, gender, address, duration of the lesions and their number, recurrence of the lesion, history of previous therapy, also family history, past medical history, obstetric history regarding the female in reproductive period and past drug history. Formal consent was taken from each patient before starting the therapy. Also, the ethical approval for this study was given by the scientific committee of the Scientific Council of Dermatology and Venereology-Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations.

Close physical examination was performed including site, size and type of the lesion; and regional lymphadenopathy. Patients with the following criteria were excluded from this study: pregnancy, lactating, chronic diseases like diabetes mellitus [10] , patients who received anti-leishmanial treatment either local or systemic.

2.1. Therapeutic Groups

Patients were divided into three groups:

(A) Zinc sulfate group: lesions were treated with oral zincsulfate in a dose of 10 mg/kg. Zincsulfate powder (heptahydrate purified) ZnSO4∙7H2O, M.W.287.54, purchased from THOMAS BAKER Company, India), is made into capsules together with glucose (BDH) as an excipient. The daily dose was calculated according to the body weight, and divided into three equal doses. Patients were instructed to take one capsule every eight hours preferably on an empty stomach. In case of young children, the parents were instructed to open the capsule and dissolve the contents in water.

(B) Ketoconazole group: lesions were treated with oralketoconazole tablet 200 mg twice daily purchased from Pharma International Company, Jordan. At baseline, laboratory tests were obtained including Serum Gamma- Glutamyltransferase (SGGT), Alkaline Phosphatase, ALT, AST, Total Bilirubin (TBL), Prothrombin Time (PT), International Normalization Ratio (INR), and viral hepatitis serology. In children, the dose was 3 mg/kg.

(C) Combination group: the third group of patients received a combination of oral zinc sulfate capsule in a dose of 10 mg/kg and ketoconazole tablet 200 mg twice daily. In addition, SGGT, alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, TBL, PT, INR, and viral hepatitis serology were performed.

2.2. Assessment of Cure Rate

Each lesion in the three groups was assessed through detecting the erythema and its diameter. Measuring the diameter of each lesion was carried out by palpation and marking the induration and measuring its diameter with a caliber in cm unit for rounded regular lesions, whereas for irregular lesions the two maximum diameters (length and width) were taken in order to calculate the mean and in ulcerative lesion, the diameter of ulcer was measured, then Sharquie’s modified leishmania score (Table 1) was used to assess the response to therapy. Patients in all three groups were assessed every 2 weeks for 6 weeks and on each visit the lesion parameters were re-assessed to record the degree of the response and to do scoring and to record any local and systemic side effects. Photos were taken for lesions in the same place, fixed illumination and distance using SONY® Cybershop camera W120 super steady 7.5Megapexiel.

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20. Data will be presented in mean ± S.D. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) will be calculated between therapeutic groups by Student t test, ANOVA, TUKEY HSD, and Scheffe.

3. Results

A total of 75 patients with acute CL were included in this study. The gender distribution was almost equal with 38 (51%) males and 37 (49%) females and their ages range from 1 to 80 years with a mean ± SD of 27.89 ± 1.82 years (Table 2). Most patients were of the young age group 31 - 40 (18%), 11 - 20 (17%). All patients in this study had multiple lesions with overall total number of 327.

Table 1. Sharquie’s modified Leishmania score to assess the objective response to the topical or systemic therapy.

Score 13-16: Mild response. Score 9-12: Moderate response. Score 5-8: Marked response. Score 0-4: Complete response &clearance. Both marked and complete responses are considered as a cure.

Table 2. Showing demographic features in three groups.

In 17 (22.4%) patients, the lesions were ulcerated while in 51 (68.1%) patients, the lesions were non-ulcerated, in six (8%) patients, the lesions were sporotrichoid while satellite lesions were seen in a single patient.

The most frequently affected site was the lower extremities 27 (36%), followed by face 24 (32%), upper limbs 21 (28%) and trunk (4%).

Patients came from different districts of the Baghdad city while others came from areas surrounding Baghdad including 41 (55%) from Alhusainia town. Family history of CL was positive in 56 (64%) of patients.

Group A: (Zinc sulfate)

A total of 24 patients with 77 lesions were included in this group. The mean duration of lesions of CL was 6.9 ± 0.7 weeks with a range of 4 - 12 weeks and the response to therapy was as follow:

In the baseline first visit, the mean Sharquie’s score was (16.000 ± 0.000 SD).

Two weeks after starting therapy: the mean score of response ± SD was 14.66 ± 1.632, this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value ˂ 0.001), (Table 3).

Four weeks after starting therapy: the mean score of response ± SD was 10.91 ± 3.322, this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit, (P value ˂ 0.000), (Table 3).

Six weeks after starting therapy: mean score of response ± SD was 6.458 ± 5.458, it was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value ˂ 0.000) (Table 3).

Regarding the percentage of grade of response in each visit during therapy, they were as follow:

Two weeks after starting therapy:

Twenty two (92%) of the treated patients showed mild improvement, 1 (4%) showed moderate response, 1 (4%) showed marked improvement, (Table 4).

Table 3. The mean and SD of total score within group A, B and C in each visit.

P = P value. *Paired t test was used to compare base line visit with other visits.

Table 4. Showing grade of response to treatment in group A, B, C.

Four weeks after starting therapy: Eleven (46%) of the treated patients showed mild improvement, 11 (46%) showed moderate response and only 1 (4%) showed complete response, (Table 4).

Six weeks after starting therapy:

Mild response was seen in 6 (25%) of patients, moderate response in 4 (12%), marked response in 1 (4%) patient while complete response in 13 (58%) patients and so the cure rate was (60%), (Table 4).

Wet and dry lesions responded equally well on this treatment. Apart from gastric upset, nausea and vomiting no appreciable side effects were noted. After healing, the scar was minimal or absent but post inflammatory hyperpigmentation was noted in all patients.

Group B: (Ketoconazole)

A total of 24 patients with 105 lesions were included in this group. The mean duration of lesions of CL was 6.5 ± 0.8weeks with a range of 4 - 12 weeks and the response was as follow:

In the baseline first visit the mean score of response ± SD was (16.000 ± 0.000), (Table 3).

Two weeks after starting therapy: the mean score of response ± SD was 15.00 ± 0.000, this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value ˂ 0.001), (Table 3).

Four weeks after starting therapy: mean score of response ± SD was 13.35 ± 1.886; this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit, P value ˂ 0.001, (Table 3).

Six weeks after starting therapy: mean score of response ± SD was 8.208 ± 3.787, it was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value ˂ 0.000), (Table 3).

Regarding the percentage of grade of response in each visit during therapy, were as follow:

Two weeks after starting therapy: Twenty four (100%) of the patient showed only mild improvement (Table 4).

Four weeks after starting therapy: Fifteen (63%) showed mild response and 9 (38%) showed moderate response, (Table 4).

Six weeks after starting therapy: Twelve (50%) of the patients showed mild response 6 (25%) showed marked response, and 6 (25%) showed complete response, this makes the cure rate 12 (50%), (Table 4).

Wet and dry lesions responded equally with this treatment. Four (5%) patients suffered from fatigue. After healing, the scar was minimal while post inflammatory hyperpigmentation was noticed in all patients.

Group C: Combination

A total of 27 patients with 143 lesions were included in this group. The mean duration of lesions of CL was 7.00 ± 0.75 weeks with a range of 4 - 12 weeks and the response was as follow:

In the baseline first visit the mean score of response ± SD was (16.000 ± 0.000), (Table 3).

Two weeks after starting therapy: the mean score of response ± SD was 11.740 ± 2.395; this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value < 0.000), (Table 3).

Four weeks after starting therapy: mean score of response ± SD was 6.481 ± 3.501; this was statistically significant when compared to the first visit, (P value < 0.000), (Table 3).

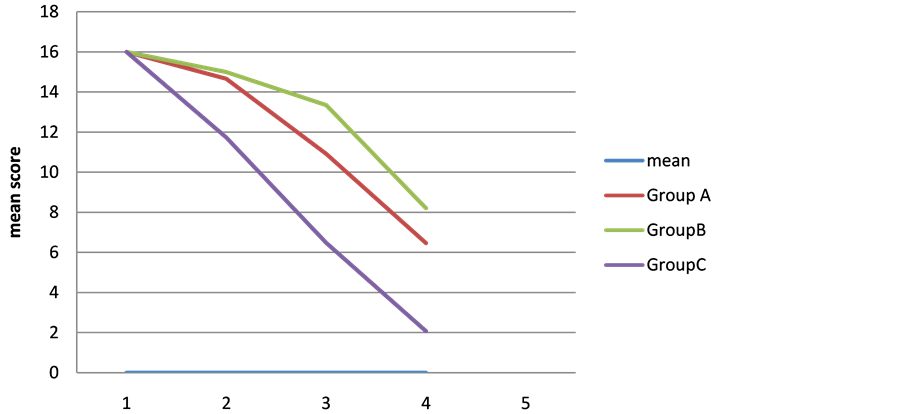

Six weeks after starting therapy: mean score of response ± SD was 2.074 ± 2.302, it was statistically significant when compared to the first visit (P value < 0.000), (Table 3), (Figure 1).

Regarding the percentage of grade of response in each visit during therapy, were as follow:

Two weeks after starting therapy: Twenty (74%) of the patients showed mild response, and 7 (26%) showed moderate response (Table 4).

Four weeks after starting therapy: One (4%) showed complete clearance, 13 (48%) showed marked response (Table 4).

Six weeks after starting therapy: one patient was mildly improved, 7 (26%) showed marked response and 19 (70%) of the patients showed complete response and most of the lesions were completely healed and thus the cure rate was (96%), (Table 4). Both wet and dry lesions responded similarly. There was minimal scarring but post-inflammatory was seen in all patients. In all groups, smear for Leishmania parasite were negative when taken from healed lesions. Ketocanazole had been used in the study both in single and in combination in 51 patients, during therapy there was no clinical signs and symptoms of systemic side effects. Laboratory tests showed liver enzyme elevation in 4% of patients in the combination group after one month of treatment, this does not need stopping the treatment then the laboratory tests return to normal value after one month.

4. Comparison between Groups

In comparison between zinc sulfate and combination therapy regarding the percentage of grade of response, there was no significant statistical difference at 2 week (P value = 0.402) but there was significant statistical

Figure 1. Showing the decline in the mean score after 6 weeks of therapy.

difference at 4 weeks (P value = 0.000). While at six weeks after starting therapy, there was statistical significant difference of (P value = 0.04) (Table 4).

The comparison between ketoconazole and combination group regarding the percentage of grade of response, there were significant statistical differences at 2 weeks (P value = 0.038), 4 weeks (P value = 0.000) and 6 weeks (P value = 0.000) (Table 4).

Regarding the complete response following 6 weeks of starting therapy, it was strongly higher in the combination group 19 (70%) than zinc sulfate group 13 (58%) and ketoconazole Group 6 (25%).

There was a statistically significant difference between groups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F = 9.389, P = 0.000). A Tukey post-hoc test revealed that the time to complete cure at six weeks was statistically significantly lower after taking combination treatment (P = 0.000) course compared to the ketoconazole course and zinc sulfate course (P = 0.04). There were no statistically significant differences between the zinc sulfate and ketoconazole groups (P = 0.146), (Table 4).When the three groups were correlated, all of them showed a marked reduction in the score response but the best one was the combination therapy (Figures 1-4).

5. Discussion

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a self healing disease, however, spontaneous cure may take several months or even years leaving an ugly scar, hence therapy aims to shorten the duration of lesions and prevent physical and mental scarring [11] .

While systemic treatment for CL is often advised when there are multiple lesions, more than five, or larger than 5 cm2 or lesions near critical areas like the eye or in children who could not be controlled during injection or in patients who refuse local treatment or when resistance to topical treatment is found [19] . The current recommended systemic treatment, which has been in use since 1950s, is parentally administered Pentavalent antimonial compounds. Although, it is effective but they are expensive and may cause serious side effects [11] . Other systemic drugs that were used in treatment of CL like oral allopurinol [20] , amphotericin B [21] , rifampicin [22] , antifungal agent [23] , trimethoprim [24] , levamisole [25] , dapson [26] , and chloroquine [27] .

Thus, the ideal therapy should be rapidly effective, easily administered, non-costly, available at all times, and should have minimal side effects [28] .

Zinc sulfate, elemental or in its various forms (salts), has been used as a therapeutic modality for centuries. Zinc, alone or as an adjuvant, has been found useful in many dermatological infections owing to its modulating actions on macrophage and neutrophil functions, natural killer cell/phagocytic activity, and various inflammatory

Figure 2. (a) A 45-year-old man with CL before treatment; (b) The same patient after 6 weeks of treatment with (ketoconazole and zinc sulfate).

Figure 3. (a) A 17-year-old female with CL before treatment; (b) The same patient after 6 weeks of treatment with (ketoconazole and zinc sulfate).

Figure 4. (a) A 30-year-old female with CL before treatment; (b) The same patient after 6 weeks of treatment with (ketoconazole and zinc sulfate).

cytokines. It is used in the treatment of viral wart [29] , leprosy [30] , acne vulgaris [31] , erosive pustuler psoriasis [32] , seborroeic dermatitis [33] . Zinc also directly affects the enzymatic system of Leishmania parasite [34] , as well as it has the ability of protein precipitation [27] . Zinc is an intracellular signal molecule that plays an important role in improving the function of macrophages, dendrocytes and monocytes and cell-mediated immunity that are in turn effective in body defense against Leishmania [34] . Moreover, zinc is involved in the determination of structural properties of molecules concerned with connection and entry of Leishmania into white blood cells [35] . Zinc also serves as a catalyst for enzymes responsible for DNA replication, gene transcription and RNA and protein synthesis. At the cellular level, zinc is critical for cell survival and affects signal transduction, transcription and replication [36] [37] . In the present work, the cure rate of zinc sulfate group was (60%). Several clinical trials have been conducted by Sharquie et al to evaluate the effect of oral zinc sulfate in treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Their results showed that the rate of cure in the group receiving oral zinc sulfate with 10mg/kg/day dose for 28.3 ± 1.4 days was (96.6%) [5] . While in the present work, the cure rate was 60% within six weeks of therapy and this was statistically significantly different (P value ˂ 0.000). The difference between these two studies could be attributed to different Sharquie’s scores used as the Sharquie’s modified Leishmania sore is more objective than the previous semi objective old Sharquie’s leishmania score [5] .

Ketoconazole is an antifungal drug that interferes with the fungal synthesis of ergosterol, a constituent of fungal cell membranes, as well as certain enzymes. As with all azole antifungal agents, ketoconazole works principally by inhibiting the enzyme cytochrome P450 14-alpha-demethylase (P45014DM) and thus block ergosterol synthesis [38] . Moreover, ketoconazole has an antibacterial effect that coincides with its greater inhibition of the biosynthesis of C-55 isoprenoid alcohol and vitamin K. The phosphorylated derivative of C-55 isoprenoid alcohol has functional importance in the biosynthesis of bacterial cell wall and membrane polymers, and the menaquinone vitamin K plays a role in the electron transport of Gram-positive bacteria. The reduced synthesis of these vital compounds may contribute to the antibacterial activity of ketoconazole [39] . Also it has an anti-inflammatory potential suggested by the known inhibitory effect of ketoconazole on 5-lipoxygenase activity and seems comparable to that of weak steroids [40] . In present study, the cure rate after six weeks oral ketoconazole was 50% which was lower than Alsaleh et al. study [41] , from Kuwait who used a higher oral dose 600 mg/day ketoconazole with cure 60% and oral 800 mg/day ketoconazole with cure rate 66.7% at the end of six weeks of treatment [41] . This diversity of cure rate could be explained by the higher dose of ketoconazole and the different scoring system.

Although single therapies, using oral zinc sulfateor oral ketoconazole, have given a good satisfactory result, yet it encourages us to conduct a study using a combination of both drugs to see whether they have a synergetic or a summation effect. Accordingly, the combination therapy gave a cure rate of 96% and using Tuckey HSD test suggests that this combination hasa synergistic effect.

The cure rate of combination therapy, in the present study was 96% which was comparable with intralesional sodium stiboglugonate with a cure rate reaching to 94% with one or 2 injections [42] , but sodium stiboglugonateis expensive, not available, difficult in storage, and painful [11] . In comparison with azithromycin the cure rate was 85% in a dose (500 - 1000 mg/d, for 2 or 10 days per month, and a maximum of 4 months of treatment [43] . A comparison with dapsone, a study in Kuwait showed that oral dapson (100 - 150 mg daily) gives 43.8% cure rate as monotherapy which is too low when compared with present study [44] . In Saudi Arabia, fluconazole (200 mg/d for 6 weeks) at the 3-month follow-up the cure rate was 59% but this drug is also expensive and the cure rate is too low [45] , but comparable with oral ketoconazole (50%) used in the present work.

The therapeutic use of combination of zinc sulfate and ketoconazole provide a solution for the rapid development of resistance and drug to drug interaction in currently new emerging antifungal drugs, they work in a synergistic way by:

1) The blockage of ergosterol biosynthesis done by ketoconazole could be enhanced by the use of zinc sulfate [38] .

2) Antileishmania activity of ketocanazole by its ability to disrupt protozoa membrane transport by blocking the proton pump could be enhanced by the use of zinc sulfate [33] .

3) The anti leishmanial effect of zinc by inhibiting the enzymes that are important for the parasite carbohydrate metabolism and virulence [36] [37] , also the increase in intracelluar zinc content of cells results in cell death, G1 and G2/M cell cycle arrest and increased apoptotic fraction [46] . All This could be enhanced by ketoconazole.

Oral zinc sulfate or oral ketoconazole can be used in combination with topical therapy like topical 25% zinc sulfate solution [47] or topical 25% podophyllin [16] in order to have a higher cure rate.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present work has proven that using oral zinc sulfate or oral ketoconazole drugs can give satisfactory results while the combination of both drugs gives a high cure rate of (96%) in patients with CL. We suggest making a combination tablet of zinc sulfate and ketoconazole to be used in the treatment of CL.

Disclosure

This study was an independent study and not funded by any drug companies.

Cite this paper

Khalifa E. Sharquie,Adil A. Noaimi,Wasnaa S. Al-Salam,1 1, (2016) Treatment of Acute Cutaneous Leishmaniasis by Oral Zinc Sulfate and Oral Ketocanazole Singly and in Combination. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications,06,105-115. doi: 10.4236/jcdsa.2016.63014

References

- 1. Desjeux, P. (2004) Leishmaniasis: Current Situation and New Perspectives. Comparative Immunology Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 27, 305-318.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.004 - 2. Dowlati, Y. (1996) Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (Old World). Clinics in Dermatology, 14, 513-517.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0738-081X(96)00047-8 - 3. Khatami, A., Firooz, A., Gorouhi, F. and Dowlati, Y. (2007) Treatment of Acute Old World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review of the Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 57, 335.e1-335.e29.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.016 - 4. Lawn, S.D., Yardley, V., Vega-Lopez, F., Watson, J. and Lockwood, D.N. (2003) New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Returned Travelers: Treatment Failures Using Intravenous Sodium Stibogluconate. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97, 443-445.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(03)90084-8 - 5. Sharquie, K.E., Najim, R.A. and Farjou, I.B. (1998) Zinc Sulphate in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: An in Vitro and Animal Study. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 93, 831-837.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761998000600025 - 6. Sharquie, K.E., Najim, R.A., Farjou, I.B. and Al-Timimi, D.J. (2001) Oral Zinc Sulphate in the Treatment of Acute Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 26, 21-26.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00752.x - 7. Sharquie, K.E. and Najim, R.A. (2004) Disseminated Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Saudi Medical Journal, 25, 951-954.

- 8. Firooz, A., Khatami, A., Khamesipour, A., Nassiri-Kashani, M., Behnia, F., Nilforoushzadeh, M., et al. (2005) Intralesional Injection of 2% Zinc Sulfate Solution in the Treatment of Acute Old World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, 4, 73-79.

- 9. Hell, R.C., Brogden, R.N., Carmen, A., Morley, P.A., Speight, T.M. and Avery, G.S. (1982) Ketocanazole: A Review of Its Therapeutic Efficacy in Superficial and Systemic Fungal Infections. Drug, 23, 1-23.

- 10. Cupp-Vickery, J.R, Garciaa, C., Hofacrea, A. and McGee-Estrada, K. (2001) Ketoconazole-Induced Conformational Changes in the Active Site of Cytochrome P450eryF1. Journal of Molecular Biology, 311, 101-110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2001.4803 - 11. Sharquie, K.E. and Al-Talib, K. (1988) Intralesional Therapy of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Sodium Stibogluconate Antimony. British Journal of Dermatology, 119, 53-57.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb07100.x - 12. Sharquie, K.E., Hussian, A.K. and Turki, K.M. (1994) Intralesional Therapy of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Hypertonic Sodium Chloride Solution. Pan-Arab Ass dermatologists, 5, 85-91.

- 13. Sharquie, K.E. and Al-Azzawi, K.E. (1996) Intralesional Therapy of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with 2% Zinc Sulfate Solution. J Pan Arab League Dermatologist, 7, 41-46.

- 14. Al-Sudany, N.K. and Ali, Y.J. (2015) Intralesional 8.33% Rifamycin Infiltration; New Treatment for Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Journal of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery, 20, 39-45.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdds.2015.11.001 - 15. Bryceson, A.D.M. (1987) Therapy in Man. In: Peters, W. and Killick-Kendrick, R., Eds., The Leishmaniasis in Biology and Medicine.

- 16. Sharquie, K.E., Noaimi, A.A. and Al-Ghazzi, G. (2015) Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis by Topical 25% Podophyllin Solution. Journal of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery, 15, 108-113.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdds.2014.10.001 - 17. Zarcarian, S.A. (1985) Complication, Indication and Contraindication in Cryosurgery. In: Zarcarian, S.A., Ed., Cryosurgery for Skin Cancer and Cutaneous Disorders, Mosby, St. Louis, 283-298.

- 18. Vegas-lopez and Hay, R.T. (2004) Parasitic Worm and Protozoa. In: Burn, B. and Coxn, G.C., Eds., Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, Vol. 32, 7th Edition, Black Well Publishing, Oxford, 1-48.

- 19. World Health Organization (1984) The Leishmaniasis: Report of a WHO Express Committee. WHO Technical Report Series No. 701, World Health Organization, Geneva.

- 20. World Health Organization (1992) Allopurinol. In: A New Perspective in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. WHO Drug Information, 6, 45-46.

- 21. James, W.D., Berger, T.G. and Elson, D.M., Eds. (2006) Parasitic Infestation, Sting, and Bites. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, Vol. 20, 10th Edition, WB Saunders Company, Toronto, 421-457.

- 22. Joshi, R.K. and Nambair, P.M.K. (1989) Dermal Leishmaniasis and Rifampicin. International Journal of Dermatology, 28, 612-614.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb02541.x - 23. Berman, J.D., Goad, L.J., Beach, D.H. and Holz, J.J. (1986) Effect of Ketoconazole on the Sterol Biosynthesis by Leishmania mexicana mexicana amastigotes in Murine Macrophage Tumor Cells. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 20, 85-92.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0166-6851(86)90145-3 - 24. Turki, K.M. and Abboud, M.M. (1983) Effect Inhibitors of Folic Acid Biosynthesis on Promastigotes L. donovani. Iraqi Journal of Science, 24, 131-134.

- 25. Buller, P.G. (1978) Levamisole Therapy of Chronic L. tropica. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 81, 221-224.

- 26. Dogra, J. (1991) A Double Blind Study on the Efficacy of Oral Dapson in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 85, 212-213.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(91)90025-T - 27. Bryceson, A. (1979) Review of Tropical Dermatology. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. British Journal of Dermatology, 94, 223-226.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb04375.x - 28. Sarhan, G.M. (1985) Epidemiological and Clinical Studies on Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Postgraduate Thesis, College of Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad.

- 29. Sharquie, K.E., Khorsheed, A.A. and Al-Nuaimy, A.A. (2007) Topical Zinc Sulphate Solution for Treatment of Viral Warts. Saudi Medical Journal, 28, 1418-1421.

- 30. Mathur, K., Bumb, R.A., Mangal, H.N. and Sharma, M.L. (1984) Oral Zinc as an Adjunct to Dapsone in Lepromatous Leprosy. International Journal of Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 52, 331-338.

- 31. Cunliffe, W.J. (1979) Unacceptable Side-Effects of Oral Zinc Sulphate in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology, 101, 363.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb05636.x - 32. Ikeda, M., Arata, J. and Isaka, I. (1982) Erosive Pustular Dermatosis of the Scalp Successfully Treated with Oral Zinc Sulphate. British Journal of Dermatology, 106, 742-743.

- 33. Piérard-Franchimont, C., Goffin, V., Decroix, J. and Piérard, G.E. (2002) A Multicenter Randomized Trial of Ketoconazole 2% and Zinc Pyrithione 1% Shampoos in Severe Dandruff and Seborrheic Dermatitis. Skin Pharmacology and Applied Skin Physiology, 15, 434-441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000066452 - 34. Prasad, A.S. (2009) Zinc: Role in Immunity, Oxidative Stress and Chronic Inflammation. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care, 12, 646-652.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283312956 - 35. Puentes, F., Guzmán, F., Marín, V., Alonso, C., Patarroyo, M.E. and Moreno, A. (1999) Leishmania: Fine Mapping of the Leishmanolysin Molecule’s Conserved Core Domains Involved in Binding and Internalization. Experimental Parasitology, 93, 7-22.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/expr.1999.4427 - 36. Bernstein, B.E., Hoffman, R.C. and Klevit, R.E. (1994) Sequence-Specific DNA Recognition by Cys2, His2 Zinc Fingers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 726, 92-104.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52800.x - 37. Rhodes, D. and Klug, A. (1993) Zinc Fingers. Scientific American, 268, 56-65.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0293-56 - 38. Eil, C. (1992) Ketoconazole Binds to the Human Androgen Receptor. Hormone and Metabolic Research, 24, 367-370.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1003337 - 39. Bossche, H.V., Lauwers, W., Willemsens, G., Marichal, P., Cornelissen, F. and Cools, W. (1984) Molecular Basis for the Antimycotic and Antibacterial Activity of N-Substituted Imidazoles and Triazoles: The Inhibition of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis. Pesticide Science, 15, 188-198.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ps.2780150210 - 40. Cutsem, J.V., Gerven, F.V., Cauwenbergh, G., Odds, F., Paul, A.J. and Janssen, P.A. (1991) The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Ketoconazole: A Comparative Study with Hydrocortisone Acetate in a Model Using Living and Killed Staphylococcus aureus on the Skin of Guinea Pigs. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 25, 257-261.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0190-9622(91)70192-5 - 41. Alsaleh, Q.A., Dvorak, R. and Nanda, A. (1995) Ketoconazole in the Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Kuwait. International Journal of Dermatology, 34, 495-497.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb00622.x - 42. Berman, J.D., Waddell, D. and Hanson, B.D. (1985) Biochemical Mechanisms of the Antileishmanial Activity of Sodium Stibogluconate. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 27, 916-920.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.27.6.916 - 43. Berman, J.D. (1988) Inhibition of Leishmanial Protein Kinase by Anti-Leishmanial Drugs. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 38, 298-303.

- 44. Neal, R.A. (1987) Experimental Chemotherapy. In: Peters, W. and Killick-kendrik, R., Eds., The Leishmaniasis in Biology and Medicine, Academic Press, London.

- 45. Bryceson, A.D., Chulay, J.D., Mugambi, M., Were, J.B., Gachihi, G., Chunge, C.N., Muigai, R., Bhatt, S.M., Ho, M., Spencer, H.C., et al. (1985) Visceral Leishmaniasis Unresponsive to Antimonial Drugs. II. Response to High Dosage Sodium Stibogluconate or Prolonged Treatment with Pentamidine. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 79, 705-714.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0035-9203(85)90199-3 - 46. Wang, Y.H., Li, K.J., Mao, L., Hu, X., Zhao, W.J., Hu, A., Lian, H.Z. and Zheng, W.J. (2013) Effects of Exogenous Zinc on Cell Cycle, Apoptosis and Viability of MDAMB231, HepG2 and 293 T Cells. Biological Trace Element Research, 154, 418-426.

- 47. Sharquie, K.E., Noaimi, A.A. and Shararah, Z.A. (2015) Topical Therapy of Acute Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Using Zinc Sulphate (25%) Solution versus Podophyllin Solution (25%). A Thesis Submitted to the Scientific Council of the Iraqi Board for Medical Specializations in Dermatology and Venereology.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.