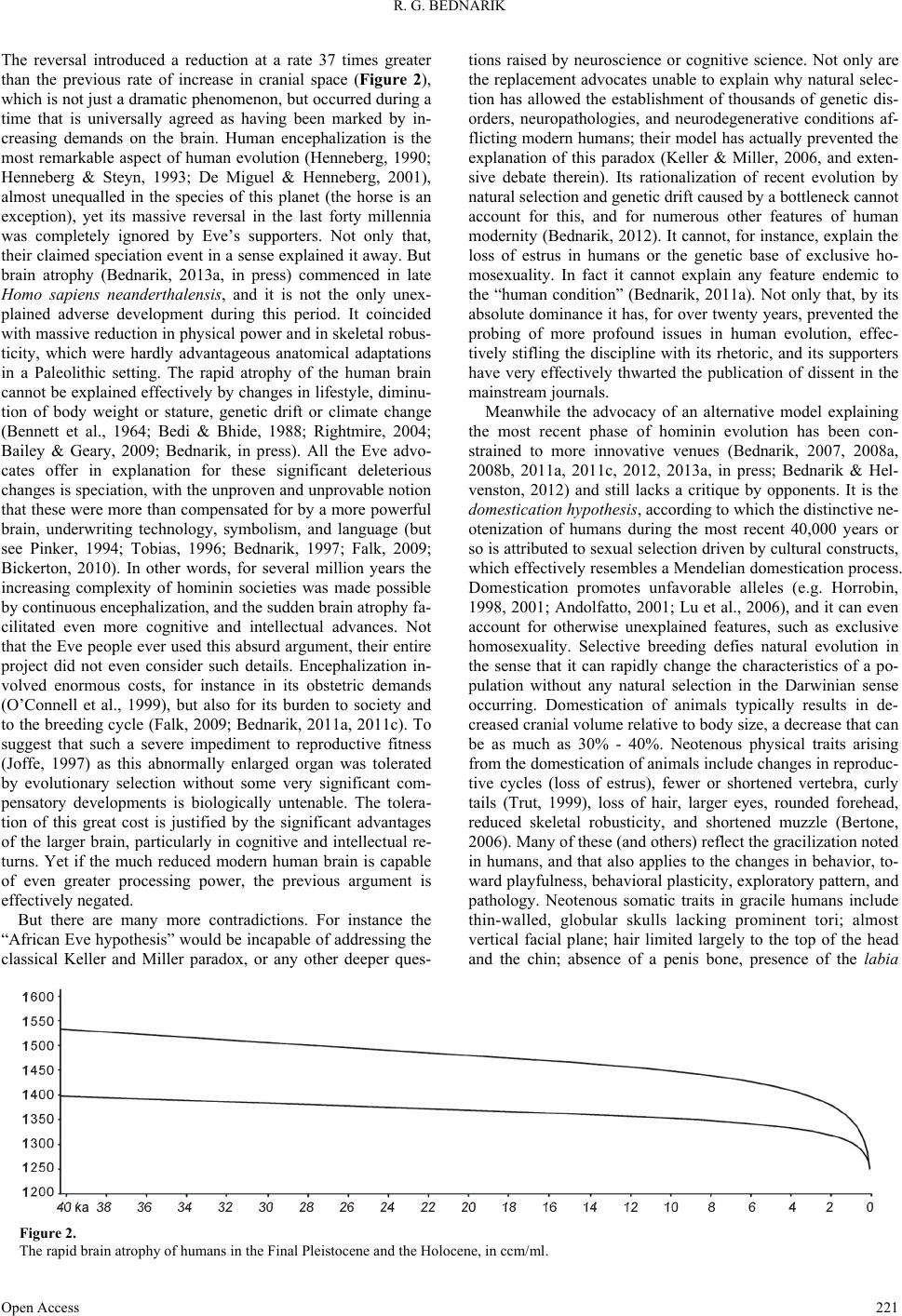

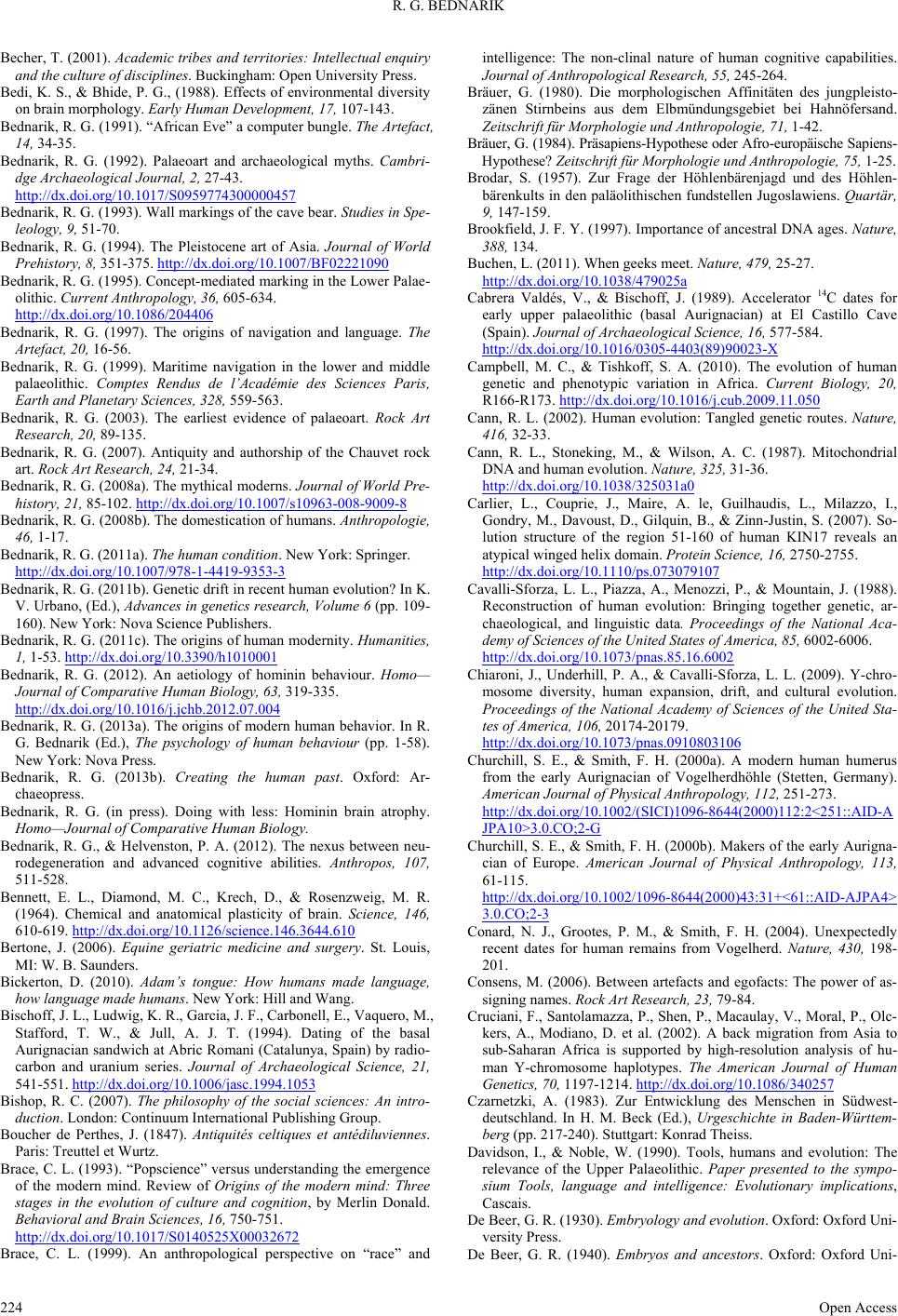

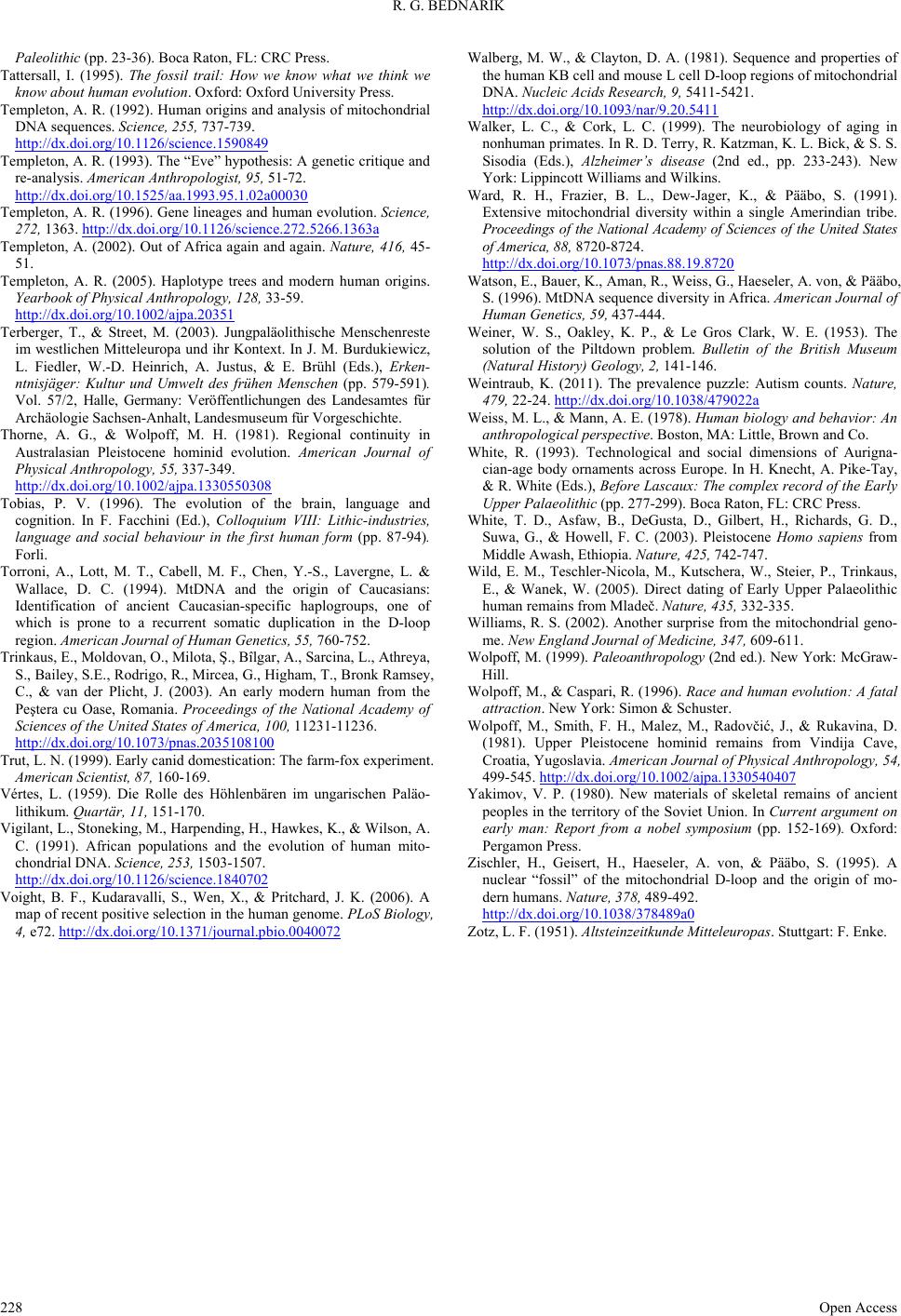

Advances in Anthropology 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 216-228 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.34031 Open Access 216 African Eve: Hoax or Hypothesis? Robert G. Bednarik International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO), Caulfield South, Melbourne, Australia Email: robertbednarik@hotmail.com Received September 11th, 2013; revised October 9th, 2013; accepted October 29th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Robert G. Bednarik. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The replacement hypothesis proposes that “modern humans” evolved only in sub-Saharan Africa, through a speciation event rendering them unable to breed with other hominins. They then spread throughout Af- rica, then to Asia, Australia and finally to Europe, replacing all other humans by exterminating or out- competing them. In this critical analysis of the replacement hypothesis it is shown that it began as a hoax, later reinforced by false paleoanthropological claims and a series of flawed genetic propositions, yet it became almost universally accepted during the 1990s and has since dominated the discipline. The nu- merous shortcomings of the hypothesis are appraised from genetic, anthropological, and archaeological perspectives and it is refuted. The resulting hiatus in the history of the human genus is then filled with an outline of a comprehensive alternative theory presented recently, which not only explains the origins of “modern humans” but also numerous so far unexplained aspects of being human. Keywords: Replacement Hypothesis; Domestication Hypothesis; African Eve; Human Evolution; Genetics; Epistemology Introduction Since the decades—long rejection of the contemporaneity of humans and Diluvial (Pleistocene) fauna (cf. e.g. Boucher de Perthes, 1846), the former existence of early hominins (cf. Fuhlrott, 1859), the Pleistocene age of certain cave art (cf. Sau- tuola, 1880) or the universal rejection of Dubois’ (1894) fossil man, pleistocene archaeology and paleoanthropology have been plagued by the failure to rise above sectarian preoccupations and struggles for authority. The proposition of this paper is that this “pre-paradigmatic state” (Kuhn, 1962) still pertains, and it is illustrated with an example that has mesmerized the disci- pline during recent decades: the origins of “anatomically mod- ern humans” (AMHs), a nonsensical concept (Latour, 1993). The notion that the “Upper Paleolithic” was introduced into Europe from Africa has been around for a long time, for in- stance Dorothy Garrod believed in this invasion in the early 20th century. In 1973 Professor Reiner Protsch “von Zieten” proposed that modern humans arose in sub-Saharan Africa, presenting a series of false datings (Terberger & Street, 2003; Schulz, 2004) of presumed “modern” fossil specimens from Europe over the following years (Protsch, 1973, 1975; Protsch & Glowatzki, 1974; Protsch & Semmel, 1978; Henke & Pro- tsch, 1978). In 2003 it was shown that all of his datings had been concocted and he was dismissed by the University of Frankfurt. However, his idea had in the meantime been deve- loped into the “Afro-European sapiens” model (Bräuer, 1984), and a few years later the “African Eve” complete replacement scenario appeared (Cann et al., 1987; Stringer & Andrews, 1988; Mellars & Stringer, 1989) and was vigorously developed sub- sequently (e.g. Vigilant et al., 1991; Tattersall, 1995; Krings et al., 1997). It was followed by the Pennisi (1999) model, the “wave theory” (Eswaran, 2002), the Templeton (2002) model, and the “assimilation theory” (Smith et al., 2005), among others. Of these, the mitochondrial Eve model is the most extreme, contending that the purported African invaders of Asia, then Australia and finally Europe, were a new species, unable to interbreed with the rest of humanity. They replaced all other humans, either by exterminating or out-competing them (be it economically or epidemiologically). In addition to having been spawned by a hoax there were right from the start significant methodological problems with this “African Eve theory”, as the media had dubbed it. The initial computer modeling by Cann et al. (1987) failed and its haplotype trees were irrelevant. Based on 136 extant mitochon- drial DNA samples, it arbitrarily selected one of 10267 alterna- tive and equally credible haplotype trees (which are very much more than the number of elementary particles of the entire uni- verse, about 1070). For instance Maddison (1991) demonstrated that a re-analysis of the Cann et al.’s model could produce 10,000 haplotype trees that are more parsimonious than the one chosen by these authors. Yet no method could even guarantee that the most parsimonious tree result should even be expected to be the correct tree (Hartl & Clark, 1997: p. 372). Cann et al.’s assump- tion of constancy of mutation rates of mtDNA was similarly a myth (Rodriguez-Trelles et al., 2001, 2002). As Gibbons (1998) noted, by using the modified putative genetic clock, Eve would not have lived 200,000 years ago, as Cann et al. had contended, but only 6000 years ago. The various genetic hypotheses about the origins of “Moderns” that have appeared over the past few decades placed the hypothetical split between these and other humans at times ranging from 17,000 to 889,000 years bp (e.g. Vigilant et al., 1991; Barinaga, 1992; Ayala, 1996; Brookfield 1997). They are all contingent upon purported models of human  R. G. BEDNARIK demography, but these and the timing or number of coloniza- tion events are practically fictional: there are no sound data available for most of these variables. This applies to the conten- tions concerning mitochondrial DNA (“African Eve”) as much as to those citing Y-chromosomes (“African Adam”; Hammer, 1995). The divergence times projected from the diversity found in nuclear DNA, mtDNA, and DNA on the non-recombining part of the Y-chromosome differ so much that a time regression of any type is extremely problematic. Contamination of mtDNA with paternal DNA has been demonstrated in extant species (Gyllensten et al., 1991; Awadalla et al., 1999; Morris & Ligh- towlers, 2000; Williams, 2002), in one recorded case amounting to 90% (Schwartz & Vissing, 2002). The issues of base substi- tution (Lindhal & Nyberg, 1972) and fragmentation of DNA (Golenberg et al., 1996) have long been known, and the point is demonstrated, for instance, by the erroneous results obtained from the DNA of insects embedded in amber (Gutierrez & Marin, 1998). Other problems with interpreting or conducting analyses of paleogenetic materials are alterations or distortions through the adsorption of DNA by a mineral matrix, its che- mical rearrangement, microbial or lysosomal enzymes degrada- tion, and lesions by free radicals and oxidation (Geigl, 2002; Carlier et al., 2007). These preliminary considerations suggest that the genetic ba- sis of the replacement hypothesis was far from sound right from its inception. The story of how it rapidly became the dominant model in human evolution, and how for over two decades it determined what could be published in mainstream venues or what kind of research would be funded not only rivals the his- tory and the effects of the Piltdown hoax (Weiner et al., 1953); it exceeds it in terms of its consequences. It is therefore justi- fied to examine the epistemology of the “African Eve hypothe- sis” in some detail, and to determine how it was possible that an entire discipline was again captivated by a paradigm that, upon careful reflection, was always improbable—and contradicted by all the relevant sound evidence available at the time it was proposed. Although initially conceived on the basis of fossil skeletal evidence (Protsch, 1973; Bräuer, 1984), it was only in 1987 that the replacement hypothesis became primarily found- ed on genetics. Its massive influence, however, has affected the disciplines of paleoanthropology and Pleistocene archaeology so profoundly that their entire current doctrines need to be que- stioned to detect the wide-ranging effects of this paradigm. This will be attempted here by examining the relevant genetics, anth- ropology and archaeology, after which an outline of the model to replace the replacement hypothesis will be presented. This paper attempts to present the differences between two hypotheses, one of which is almost bereft of empirical support, while the other has ample support and offers extensive expla- natory potential. The apparent biases by the author are simply a reflection of this state. The Genetics Since 1987 the genetic distances in nuclear DNA (the dis- tances created by allele frequencies) proposed by different re- searchers or research teams have produced conflicting results (e.g. Vigilant et al., 1991; Barinaga, 1992; Ayala, 1996; Brook- field, 1997), and some geneticists concede that the models rest on untested assumptions; others even oppose them (e.g. Bari- naga, 1992; Hedges et al., 1992; Maddison et al., 1992; Tem- pleton, 1992, 1993, 1996, 2002, 2005; Brookfield, 1997; Klyo- sov & Rozhanskii, 2012a, 2012b; Klyosov et al., 2012; Klyosov & Tomezzoli, 2013). The key claim of the replacement theory, that the “Neanderthals” were genetically so different from the “Moderns” that the two were separate species, has been under strain since Gutierrez et al. (2002) demonstrated that the pair- wise genetic distance distributions of the two human groups overlap more than claimed, if the high substitution rate varia- tion observed in the mitochondrial D-loop region (see Walberg & Clayton, 1981; Torrini et al., 1994; Zischler et al., 1995) and lack of an estimation of the parameters of the nucleotide subs- titution model are taken into account. The more reliable genetic studies of living humans have shown that both Europeans and Africans have retained significant alleles from multiple popula- tions of Robusts (Hardy et al., 2005; Garrigan et al., 2005; cf. Templeton, 2005). After the Neanderthal genome yielded results that seemed to include an excess of Gracile single nucleotide polymorphisms (Green et al., 2006), more recent analyses con- firmed that “Neanderthal” genes persist in recent Europeans, Asians, and Papuans (Green et al., 2010). “Neanderthals” (use of this term here is only to comply with established jargon and implies no approval; the generic term “Robusts” is preferable) are said to have “interbred” with the ancestors of Europeans and Asians, but not with those of Africans (Gibbons, 2010; cf. Krings et al., 1997). The African alleles occur at a frequency averaging only 13% in non-Africans, whereas those of other re- gions match the Neanderthaloids in ten of twelve cases. “Nean- derthal genetic difference to humans [note however that all members of the genus Homo are humans!] must therefore be interpreted within the context of human diversity” (Green et al., 2006: p. 334). This suggests that gracile Europeans and Asians evolved largely from local robust populations, which had long been obvious from previously available evidence. For instance Alan Mann’s finding that tooth enamel cellular traits showed a close link between Neanderthaloids and present Europeans, which both differ from those of Africans (Weiss & Mann, 1978), had been ignored by the Eve protagonists, as has much other empirical evidence (e.g., Roginsky et al., 1954; Yakimov, 1980). In response to the initial refutations of the Eve model, Cann (2002) made no attempt to argue against the alternative propo- sals of long-term, multiregional evolution. So what was it that prompted Pleistocene archaeology and paleoanthropology to recycle Protsch’s African hoax? Cavalli- Sforza et al. (1988) considered that the phylogenetic tree sepa- rates Africans from non-Africans, a view reinforced by Klyo- sov et al. (2012). But whereas the first authors interpreted this as placing the origin of “modern humans” in Africa, Klyosov et al. showed that this separation continued for 160 ± 12 ka since the split of the haplogroups A from haplogroups BT (Cruciani et al., 2002); therefore Africans and non-Africans evolved es- sentially separate. As Klyosov et al. most pertinently observe, “a boy is not a descendant of his older brother”. Therefore, con- trary to Chiaroni et al. (2009), haplogroup B is neither restricted to Africa, nor is it at 64 ka remotely as old as the haplogroups A are (some of these may be older than 160 ka). Another flaw of the replacement model was that Cann et al. had also mis-estimated the diversity per nucleotide (single locus on a string of DNA), incorrectly using the method developed by Ewens (1983) and thereby claiming greater genetic diversity of Africans, compared to Asians and Europeans. This oft-repeated claim (e.g. Hellenthal et al., 2008; Campbell & Tishkoff, 2010) is false: the genetic diversity coefficients are very similar, 0.0046 for both Africans and Asians, and 0.0044 for Europeans. Even the premise of genetic diversity is false, for instance it is Open Access 217  R. G. BEDNARIK greater in African farming people than in African hunters- foragers (Watson et al., 1996), yet the latter are not assumed to be ancestral to the former (see e.g. Ward et al., 1991). Similarly, the contention that genetic diversity of extant humans decreases with increasing geographical distance from Africa (e.g. Atkin- son, 2011) is doubtful, and has no bearing on the questions of the origins of the “AMHs”. Certainly such diversity diminishes markedly in regions first occupied in the Final Pleistocene or Holocene, which is to be expected, but the number of haplo- types is higher in Eurasia than in Africa. It is interesting to note that the “genetic clock” archaeologists subscribe to in reference to these purported AMHs is rejected when it is applied to the dog, implying its split from the wolf occurred 135 ka ago. Archaeologists disallow it because there is no paleontological evidence for dogs prior to about 15,000 years ago (Napierala & Uerpmann, 2010; but see Germonpré et al., 2009). The same restraint and avoidance of a catastrophist scenario is needed in relation to hominins. After all, humans are only one of the many species that have managed to colonize a great variety of environments, from the Arctic to the tropics, and in all cases genetic diversity is thought to be the result of introgression. Perhaps this discrepancy in approach is attribut- able to humanistic fervor (Bednarik, 2011a). That view is sup- ported by a critical consideration of the fossil hominin evidence and a review of the cultural indices, both of which have been recruited extensively in support of the “African Eve hypothe- sis”. The Paleoanthropology As noted, the original impetus of the African Eve notion de- rived from the false datings of numerous hominin remains, especially in Europe. This included those of the four Stetten individuals from Vogelherd, Germany, widely claimed to be about 32 ka old (e.g. Churchill & Smith, 2000a, 2000b), when in fact their Neolithic provenience had long been noted (Gieseler, 1974; Czarnetzki, 1983: p. 231) and they are between 3980 ± 35 and 4995 ± 35 carbon-years old (Conard et al., 2004). The Hahnöfersand calvarium, the “northernmost Neanderthal speci- men found” and dated to 36,300 ± 600 bp or 35,000 ± 2000 bp (Bräuer, 1980) by Protsch, is actually a Mesolithic “Neander- thal”, at 7470 ± 100 bp or 7500 ± 55 bp (Terberger & Street, 2003). The Paderborn-Sande skull fragment, purportedly 27,400 ± 600 years old (Henke & Protsch, 1978), is only 238 ± 39 carbon-years old (Terberger & Street, 2003). The Kelsterbach skull, dated to 31,200 ± 1600 years bp (Protsch & Semmel, 1978; Henke & Rothe, 1994), is probably of the Metal Ages (Terberger & Street, 2003) but has mysteriously disappeared from its safe. And the cranial fragment from Binshof, dated by Protsch to 21,300 ± 20 bp, is in fact only 3090 ± 45 years old. These German finds are not the only misdated fossils from the crucial period of the “Early Upper Paleolithic” in Europe. The “modern” Robust specimen from Velika Pećina, Croatia, is now known to be only 5045 ± 40 radiocarbon years old (Smith et al., 1999). Those from Roche-Courbon (Geay, 1957) and Combe-Capelle (originally attributed to the Châtelperronian le- vels; Klaatsch & Hauser, 1910) are now thought to be Holo- cene burials (Perpère, 1971; Asmus, 1964), as probably is the partial skeleton from Les Cottés (Perpère, 1973). The “type fos- sils” of early “modern” Europeans, the “Aurignacian” Crô-Ma- gnon specimens, are not at all of modern skeletal anatomy; es- pecially cranium 3 is quite Neanderthaloid. Moreover, at about 27,760 carbon-years (Henry-Gambier, 2002) they are of the Gravettian and not of the Aurignacian. A similar pattern per- tains to the numerous relevant Czech specimens, most of which are intermediate between robust and gracile. This includes the Mladeč sample, now dated to between 26,330 and 31,500 bp (Wild et al., 2005), the very robust specimens from Pavlov and Předmostí (both between 26 and 27 ka), Podbaba (undated), and the slightly more gracile and more recent population from Dolní Věstonice. The same pattern of “intermediate” forms continues in the specimens from Cioclovina (Romania), Bacho Kiro levels 6/7 (Bulgaria) and Miesslingtal (Austria). The earliest liminal “post-Neanderthal” finds currently avail- able in Europe are the Peştera cu Oase mandible from Romania (Trinkaus et al., 2003), apparently in the order of 35 ka old, and the partial cranium subsequently found in another part of the same cave (Rougier et al., 2007). Both lack an archaeological context and are not “anatomically modern”. The six human bones from another Romanian cave, Peştera Muierii (~30 14C ka bp), are also intermediate between robust and gracile types (Soficaru et al., 2006). In fact literally hundreds of Eurasian specimens of the last third of the Late Pleistocene are interme- diate between robust Homo sapiens and H. sapiens sapiens, or imply that a simplistic division between “Moderns” and “Ne- anderthals” is false. They include the finds from Lagar Velho, Crete, Starosel’e, Rozhok, Akhshtyr’, Romankovo, Samara, Sungir’, Podkumok, Khvalynsk, Skhodnya, Denisova, and Nar- mada, as well as several Chinese remains such as those from the Jinniushan and Tianyuan Caves. The replacement advocates ignored this obvious obstacle to their model, of numerous inter- mediate or liminal forms contradicting their belief that robust and gracile populations were separate species. Moreover, they failed to appreciate that not a single fully gracile specimen in Eurasia can credibly be linked to any Early Upper Paleolithic tool tradition, be it the Aurignacian, Châtelperronian, Uluzzian, Proto-Aurignacian, Olschewian, Bachokirian, Bohuni-cian, Stre- letsian, Gorodtsovian, Brynzenian, Spitzinian, Telmanian, Sze- letian, Eastern Szeletian, Kostenkian, Jankovichian, Altmühlian, Lincom-bian, or Jerzmanovician (Bednarik, 2011a). Therefore their proposition that these industries were introduced from sub-Saharan Africa is without basis, especially as there are no geographically intermediate Later Stone Age finds from right across northern Africa until more than 20,000 years after the Upper Paleolithic had been established in Eurasia. Similarly, the African Eve advocates ignored that at least six Early Upper Paleolithic sites have yielded human skeletal remains attributed to Neanderthals: the Châtelperronian layers of Saint Césaire (~36 ka) and Arcy-sur-Cure (~34 ka) in France, the Aurigna- cian of Trou de l’Abîme in Belgium, the Hungarian Jankovi- chian of Máriaremete Upper Cave (~38 ka; Gábori-Csánk, 1993), the Streletsian of Sungir’ in Russia (which yielded a Neanderthaloid tibia from a triple grave of “Moderns”; Bader 1978), and the Olschewian of Vindija in Croatia (Smith et al., 1999, 2005; Ahern et al., 2004). The Neanderthals at the latter site are the most recent such remains reported so far (28,020 ± 360 and 29,080 ± 400 carbon years bp). Like other late speci- mens they are much more gracile than most earlier finds—so much so that many consider them as transitional (e.g. Smith & Raynard, 1980; Wolpoff et al., 1981; Frayer et al., 1993; Wol- poff, 1999; Smith et al., 2005). The replacement paradigm is not even supported by the pa- leoanthropological finds from Africa, which generally mirror the gradual changes in Eurasia through time. It is often claimed Open Access 218  R. G. BEDNARIK that “AMHs” date from up to 200 ka ago, yet no such speci- mens exist. The skulls from Omo Kibish offer some relatively modern features as well as substantially archaic ones; especially Omo 2 is very robust indeed (McDougall et al., 2005). Their dating, also, is not secure, and Omo 2 is a surface find. The much more complete and better dated Herto skull, BOU-VP- 16/1, is outside the range of all recent humans in several cranial measurements (White et al., 2003)—and is just as archaic as other specimens of the late Middle Pleistocene, in Africa or elsewhere. The lack of “anatomically modern” humans from sub-Saharan Africa prior to the supposed Exodus is glaring: the Border Cave specimens have no stratigraphic context; Dar es Soltan is undated; and the mandibles of Klasies River Mouth lack cranial and post-cranial remains. The Hofmeyr skull from South Africa, about 36 ka old, features intermediate morphol- ogy (Grine et al., 2007, 2010) comparable to that found in Europe at that time, e.g. in Romanian specimens. Similarly, extant Australians, with their average cranial capacity of 1264 cc (males 1347 cc, females 1181 cc, i.e. well within the range of Homo erectus), possess molars and other indices of robustic- ity matching those of Europeans several hundred millennia ago, yet they are “AMHs”. Their tool traditions were of Mode 3 types (Middle Paleolithic) until mid-Holocene times, and re- mained so in Tasmania until European colonization. Clearly, the guiding principle of the replacement advocates, that Mode 4 technologies were introduced together with “modern” anatomy is false, in Europe as well as elsewhere. The scarcity of African fossils of the African Eve “species” prompted the replacement advocates to turn to the Levant for help, which would be on the route the Exodus had taken, and the Mount Carmel finds from Qafzeh Cave and Skhul Shelter were recruited as “Moderns” (Stringer et al., 1989; Grün & Stringer, 1991; Stringer & Gamble, 1993; McDermott et al., 1993). Yet all of these skulls present prominent tori and reced- ing chins, even Qafzeh 9, claimed to be of the most modern appearance. The distinct prognathism of Skhul 9 matches that of “classic Neanderthals”, and the series of teeth from that cave has consistently larger dimensions than Neanderthaloid teeth. Supposedly much later “Neanderthal” burials in nearby Tabun Cave as well as the Qafzeh and Skhul material are all associ- ated with the same Mousterian tools, and the datings of all Mount Carmel sites are far from soundly established, with their many discrepancies. The TL dates from Qafzeh, for instance, clash severely with the amino racemization dates (ranging from 33 to 45 ka), and are in any case plagued by inversion: the lower layer 22 averages 87.7 ka, the middle layer 19 is 90.5 ka, while the uppermost layer 17 averages 95.5 ka (Mercier et al., 1993; cf. Bada & Masters Helfman, 1976). Therefore the claims of 90-ka-old “modern” humans from Mount Carmel, a corner- stone in the Eve model, are unsound, and this population is best seen as transitional between robust and gracile forms, from a time when gracilization had commenced elsewhere as well. The Archaeology The Early Upper Paleolithic (EUP) tool traditions of Eurasia, claimed to indicate the arrival of Eve’s progeny there, all evol- ved locally. They first appear fairly simultaneously between 45 ka and 40 ka bp, even earlier, at widely dispersed locations from Spain to Siberia (e.g. Makarovo 4/6, Kara Bom, Denisova Cave, Ust’-Karakol, Tolbaga, Kamenka, Khotyk, Podzvon-kaya, Tolbor Dorolge, & Bednarik, 1994). The earliest carbon date was provided by Senftenberg, Austria, at >54 ka bp (Felgen- hauer, 1959). The Aurignacian of Spain commences at least 43 ka ago (Bischoff et al., 1994; Cabrera Valdés & Bischoff, 1989). EUP variants such as the Uluzzian (Palma di Cesnola, 1976, 1989), the Uluzzo-Aurignacian, and the Proto-Aurignacian (43 - 33 ka bp) have been reported from southern Italy (Kuhn & Bietti, 2000; Kuhn & Stiner, 2001). The montane Aurignacoid tradition of central Europe, the Olschewian (42 - 35 ka bp), clearly developed from the region’s final Mousterian (Bayer, 1929; Kyrle, 1931; Bächler, 1940; Zotz, 1951; Brodar, 1957; Malez, 1959; Vértes, 1959; Bednarik, 1993). The Bachokirian of the Pontic region (>43 ka bp), the Bohunician of east-central Europe (44 - 38 ka bp; Svoboda, 1990, 1993), and various tra- ditions of the Russian Plains complete the picture to the east. Some of the latter industries, such as the Streletsian, Gorodtso- vian, and Brynzenian derived unambiguously from Mousteroid technologies, whereas the Spitzinian or Telmanian are free of Mode 3 bifaces (Anikovich, 2005). The gradual development of Mode 3 industries into Mode 4 traditions can be observed at various sites along the Don River, in the Crimea and northern Caucasus, with no less than seven accepted tool assemblages coexisting between 36 and 28 ka ago: Mousterian, Micoquian, Spitzinian, Streletsian, Gorodtsovian, Eastern Szeletian and Au- rignacian (Krems-Dufour variant). A mosaic of early Mode 4 industries began before 40 ka bp on the Russian Plain and ended only 24 - 23 ka ago. In fact in the Crimea, the Middle Pa- leolithic is thought to have ended only between 20 - 18 ka bp, which is about the same time the Middle Stone Age ended across northern Africa. In the Russian Plain, the first fully de- veloped Upper Paleolithic tradition, the Kostenkian, appears only about 24 ka ago. The Russian succession of traditions connecting Mode 3 and 4 technocomplexes is repeated in the Szeletian of eastern Eu- rope (43 - 35 ka bp; Allsworth-Jones, 1986), the Jankovician of Hungary; and the Altmühlian (~38 ka bp), Lincombian (~38 ka bp) and Jerzmanovician (38 - 36 ka bp) further northwest. Similarly, the gradual development from the Middle Paleolithic at 48 ka bp (with “Neanderthal” footprints of small children) to the Upper Paleolithic is clearly documented in Theopetra Cave, Greece (Kyparissi-Apostolika, 2000; Facorellis et al., 2001). Thus there is a complete absence of evidence in the presumed eastern or southeastern entry region of Europe, of an intrusive technology arriving from the Levant. Nor should it be expected, considering that in the Levant both Mode 3 and Mode 4 indus- tries were used by robust as well as more gracile populations: the replacement advocates’ notion that their “Moderns” intro- duced Mode 4 in Europe is refuted by all archaeological evi- dence. The Mousteroid traditions of the Levant developed gra- dually into blade industries, e.g. at El Wad, Emireh, Ksar Akil, Abu Halka, & Bileni Caves, and that region’s Ahmarian is tran- sitional. This can be observed elsewhere in southwestern Asia, for instance the Aurignacoid Baradostian tradition of Iran clear- ly develops in situ from Middle Paleolithic antecedents. The late Mousterian of Europe is universally marked by regiona- lization (Kozłowski, 1990; Stiner, 1994; Kuhn, 1995; Riel-Sal- vatore & Clark, 2001), miniaturization, and increasing use of blades, as well as by improved hafting technique. This includes the use of backed or blunted-back retouch on microliths set in birch resin in Germany, almost as early as the first use of mi- crolithic implements in the Howieson’s Poort tradition of far southern Africa. Therefore the notion that a genetically and paleoanthropologically unproven people with a Mode 4 tool set Open Access 219  R. G. BEDNARIK travelled from sub-Saharan Africa across northern Africa is completely unsupported, while there is unanimous proof that these traditions developed in situ in many Eurasian regions long before they reached either northern Africa or the Levant. Precisely the same applies to paleoart. The replacement ad- vocates relied considerably on the unassailability of their belief that the EUP traditions, especially the Aurignacian, were by “AMHs” (Graciles). As mentioned above, there are no unam- biguous associations between “AMHs” and any of the many identified EUP tool traditions, including the Aurignacian. These “cultures”, as they are called, are merely etic constructs, “ob- server-relative or institutional facts” (Searle, 1995); as “archae- ofacts” or “egofacts” (Consens, 2003) they have no real, emic existence. They are entirely made up of invented (etic) tool types and based on the misunderstanding in Pleistocene archa- eology that tools are diagnostic for identifying cultures. The authentic cultural variables of Pleistocene archaeology have never been employed in creating the period’s cultural nomen- clature. Cultures are defined by cultural variables, but Pleisto- cene archaeology as it is conducted relegates the cultural infor- mation available (such as rock art and portable “art”) to mar- ginal rather than central status, forcing it into the false techno- logical framework it has created. One of the effects of this misunderstanding has a direct bear- ing of the “African Eve hypothesis”. Among the EUP traditions its advocates attribute to AMHs, the Châtelperronian was in 1979 discovered to be the work of Neanderthals. But the Châ- telperronian of Arcy-sur-Cure in France had produced nume- rous portable palaeoart objects, including beads and pendants (Figure 1). So the Eve supporters argued that the primitive Neanderthals, incapable of symboling, must have “scavenged” and used these artifacts (White, 1993; Hublin et al., 1996). They failed to explain, however, why such primordial creatures would possibly scavenge symbolic objects and what they would do with them. This is one of numerous examples of the accom- modative reasoning of the replacement advocates, others can be found in d’Errico (1995), d’Errico and Villa (1997) and Ri- gaud et al. (2009); or in the assertion that Early Pleistocene Figure 1. Body ornaments made and used by “Neanderthals”, from Arcy-sur-Cure, France: two ivory ring fragments, two perforated animal canines, and a fossil shell with an artificial groove for attachment. seafaring colonizers (Bednarik, 1997, 1999, 2003) might have drifted on vegetation. After it was first observed that there is no evidence linking early Aurignacian finds to the purported Mo- derns (Bednarik, 1995), it was proposed that no such link exists to any EUP industry (Bednarik, 2007, 2008a). The contention that the Aurignacian rock art (e.g. in Chauvet Cave, Zarzamora Cave, El Castillo) and portable paleoart (e.g. in Hohlenstein), arguably the most complex and sophisticated of the entire Upper Paleolithic, is the work either of “Neanderthals” or of their direct descendants (Bednarik, 2007, 2008a, 2011a, 2011b; Sadier et al., 2012) has demolished the last vestiges of support for the “African Eve hypothesis”. It now stands refuted. The re- cord shows unambiguously that the Upper Paleolithic of Eura- sia developed in situ, that the hominins in question evolved in situ, and that introgression accounts fully for the genetic obser- vations. “Modern” or gracile humans derive from archaic H. sa- piens in four continents, they interbred no more than grand- children breed with their grandparents. Klyosov et al. 2012, who demonstrate genetically that recent human evolution in Eurasia must have occurred in situ, list no less than 24 papers asserting that “AMHs” (see Tobias, 1996 for a cogent rejection of this concept) entered Europe between 27 and 112 ka ago. Most of these nominate 40 to 70 ka as the time of the “African invasion”. It would seem that these unte- nable propositions simply reflect archaeological estimates of a phenomenon that never actually occurred (Bednarik, 2013b). Replacing the “African Eve Hypothesis” Replacing the replacement theory is not going to be easy, because of the deeply embedded vested interests defending it. Yet it lacks any archaeolo-gical, paleoanthropological, techno- logical, or cultural evidence (Bednarik, 1991, 1992, 1995, 1997, 2008a, 2011a). Introgressive hybridization (Anderson, 1949), allele drift based on generational mating site distance (Harpen- ding et al., 1998), and genetic drift (Bednarik, 2011b) through episodic genetic isolation during climatically unfavorable events (Barberi et al., 1978; Fedele et al., 2002, 2003; Fedele & Gia- ccio, 2007) account for the mosaic of hominin forms found from the Arctic (Schulz, 2002; Schulz et al., 2002; Pavlov et al., 2001) to the tropics, from Iberia to Australia. The failure of the “African Eve hypothesis” leaves a huge hiatus in the received narrative of hominin evolution, in that the most controversial part of it is left without an explanation. The alternative multi- regional model, almost vanquished in the wake of Eve, offers a reprieve, but it is in need of much greater detail. Its vantage position derives from default: as the single origin notion fails, there is only one option left, namely that changes occurred in many centers in four continents. This is broadly what the ar- chaeological, paleoanthropological, and genetic data gathered so far imply, but for the past decades only a handful of scholars subscribed to this position (e.g. Thorne & Wolpoff, 1981; Bed- narik, 1992, 1995 et passim; Brace, 1993, 1999; Wolpoff & Ca- spari, 1996; Wolpoff, 1999; Eckhart, 2000; Henneberg, 2004). What remains profoundly lacking is a theory of the processes underlying the rather sudden appearance of what has been term- ed “AMHs”. The greatest mistake of the replacement advocates was to disregard the inherent fundamentals of the hominin changes toward the end of the Pleistocene. For instance human brain volume, after the relentless encephalization of millions of years, suddenly began decreasing rapidly (Henneberg, 1988, 2004). Open Access 220  R. G. BEDNARIK Open Access 221 The reversal introduced a reduction at a rate 37 times greater than the previous rate of increase in cranial space (Figure 2), which is not just a dramatic phenomenon, but occurred during a time that is universally agreed as having been marked by in- creasing demands on the brain. Human encephalization is the most remarkable aspect of human evolution (Henneberg, 1990; Henneberg & Steyn, 1993; De Miguel & Henneberg, 2001), almost unequalled in the species of this planet (the horse is an exception), yet its massive reversal in the last forty millennia was completely ignored by Eve’s supporters. Not only that, their claimed speciation event in a sense explained it away. But brain atrophy (Bednarik, 2013a, in press) commenced in late Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, and it is not the only unex- plained adverse development during this period. It coincided with massive reduction in physical power and in skeletal robus- ticity, which were hardly advantageous anatomical adaptations in a Paleolithic setting. The rapid atrophy of the human brain cannot be explained effectively by changes in lifestyle, diminu- tion of body weight or stature, genetic drift or climate change (Bennett et al., 1964; Bedi & Bhide, 1988; Rightmire, 2004; Bailey & Geary, 2009; Bednarik, in press). All the Eve advo- cates offer in explanation for these significant deleterious changes is speciation, with the unproven and unprovable notion that these were more than compensated for by a more powerful brain, underwriting technology, symbolism, and language (but see Pinker, 1994; Tobias, 1996; Bednarik, 1997; Falk, 2009; Bickerton, 2010). In other words, for several million years the increasing complexity of hominin societies was made possible by continuous encephalization, and the sudden brain atrophy fa- cilitated even more cognitive and intellectual advances. Not that the Eve people ever used this absurd argument, their entire project did not even consider such details. Encephalization in- volved enormous costs, for instance in its obstetric demands (O’Connell et al., 1999), but also for its burden to society and to the breeding cycle (Falk, 2009; Bednarik, 2011a, 2011c). To suggest that such a severe impediment to reproductive fitness (Joffe, 1997) as this abnormally enlarged organ was tolerated by evolutionary selection without some very significant com- pensatory developments is biologically untenable. The tolera- tion of this great cost is justified by the significant advantages of the larger brain, particularly in cognitive and intellectual re- turns. Yet if the much reduced modern human brain is capable of even greater processing power, the previous argument is effectively negated. But there are many more contradictions. For instance the “African Eve hypothesis” would be incapable of addressing the classical Keller and Miller paradox, or any other deeper ques- tions raised by neuroscience or cognitive science. Not only are the replacement advocates unable to explain why natural selec- tion has allowed the establishment of thousands of genetic dis- orders, neuropathologies, and neurodegenerative conditions af- flicting modern humans; their model has actually prevented the explanation of this paradox (Keller & Miller, 2006, and exten- sive debate therein). Its rationalization of recent evolution by natural selection and genetic drift caused by a bottleneck cannot account for this, and for numerous other features of human modernity (Bednarik, 2012). It cannot, for instance, explain the loss of estrus in humans or the genetic base of exclusive ho- mosexuality. In fact it cannot explain any feature endemic to the “human condition” (Bednarik, 2011a). Not only that, by its absolute dominance it has, for over twenty years, prevented the probing of more profound issues in human evolution, effec- tively stifling the discipline with its rhetoric, and its supporters have very effectively thwarted the publication of dissent in the mainstream journals. Meanwhile the advocacy of an alternative model explaining the most recent phase of hominin evolution has been con- strained to more innovative venues (Bednarik, 2007, 2008a, 2008b, 2011a, 2011c, 2012, 2013a, in press; Bednarik & Hel- venston, 2012) and still lacks a critique by opponents. It is the domestication hypothesis, according to which the distinctive ne- otenization of humans during the most recent 40,000 years or so is attributed to sexual selection driven by cultural constructs, which effectively resembles a Mendelian domestication process. Domestication promotes unfavorable alleles (e.g. Horrobin, 1998, 2001; Andolfatto, 2001; Lu et al., 2006), and it can even account for otherwise unexplained features, such as exclusive homosexuality. Selective breeding defies natural evolution in the sense that it can rapidly change the characteristics of a po- pulation without any natural selection in the Darwinian sense occurring. Domestication of animals typically results in de- creased cranial volume relative to body size, a decrease that can be as much as 30% - 40%. Neotenous physical traits arising from the domestication of animals include changes in reproduc- tive cycles (loss of estrus), fewer or shortened vertebra, curly tails (Trut, 1999), loss of hair, larger eyes, rounded forehead, reduced skeletal robusticity, and shortened muzzle (Bertone, 2006). Many of these (and others) reflect the gracilization noted in humans, and that also applies to the changes in behavior, to- ward playfulness, behavioral plasticity, exploratory pattern, and pathology. Neotenous somatic traits in gracile humans include thin-walled, globular skulls lacking prominent tori; almost vertical facial plane; hair limited largely to the top of the head and the chin; absence of a penis bone, presence of the labia Figure 2. The rapid brain atrophy of humans in the Final Pleistocene and the Holocene, in ccm/ml.  R. G. BEDNARIK majora and hymen; alignment of the organs of the lower abdomen, such as rectum, urethra and vagina forward of the spine; slow closing of the cranial sutures; shape of the cartilage of the ear; and the shape of both hands and feet. All of these features in modern humans resemble those of fetal chimpanzees, and all of them disappear in apes around birth or soon after, whereas in humans sexual maturity is attained before full so- matic development, and the juvenile characteristics are retained for life (De Beer, 1930, 1940; Haldane, 1932; Ashley Montagu, 1960; Badcock, 1980). Neotenous development of recent homi- nins is one of many results of selective breeding. Unintentional self-domestication through deliberate breed- ing-mate choice is unique to recent humans: no other animal, including primates, exhibits preferences in mate selection of youth or specific body ratios, facial features, skin tone or hair; yet in present humans these are deeply entrenched, practically “hardwired”. Facial symmetry, seen to imply high immuno- competence (Grammer & Thornhill, 1994; Shackelford & Lar- sen, 1997), is also of importance, and in female humans neo- tenous facial and other features are strongly preferred by males (Jones, 1995, 1996). Since this applies today, the rational way to examine the issue is to consider at what point in human de- velopment the influence of non-evolutionary currents can be first detected. The fossil record suggests that around 40 ka ago, cultural practice had become such a determining force in hu- man society that breeding mate selection became increasingly moderated by cultural factors, i.e. by factors attributable to learned behavior (Bednarik, 2008a, 2008b, 2011a, 2013a). These could have included the application of a variety of cultural con- structs in such choices, such as social standing, communication skills, body decoration (which becomes notably prominent 40 ka ago, although existing earlier), but most especially culturally negotiated constructs of physical attractiveness. Besides the domestication hypothesis there is currently no alternative explanation for the rapid and continuing establish- ment of the thousands of neuropathological, neurodegenerative and other detrimental alleles typically absent in extant non-hu- man primates (Rubinsztein et al., 1994; Walker & Cork, 1999; Olson & Varki, 2003). Selective genetic sweeps tend to yield relatively recent etiologies, of less than 20,000 years, for all hu- man neuropathologies. For instance the absence of such schi- zophrenia susceptibility alleles as NRG3 is demonstrated in an- cestral robust humans (Voight et al., 2006), and this mental ill- ness has been suggested to be of very recent etiology (Hare, 1988; Bednarik & Helvenston, 2012). Numerous deleterious conditions were derived from the neoteny accounting for mod- ern humans, including cleidocranial dysplasia or delayed clo- sure of cranial sutures, malformed clavicles, and dental abnor- malities (genes RUNX2 and CBRA1 refer), type 2 diabetes (gene THADA); the microcephalin D allele, introduced in the final Pleistocene (Evans et al., 2005); or the ASPM allele, an- other contributor to microcephaly, which appeared around 5800 years ago (Mekel-Bobrov, 2005). A good example of the recent advent of detrimental genes is that of CADPS2 and AUTS2, involved in autism and absent in robust humans. The human brain condition autistic spectrum disorder seems to have be- come notably more prominent in recent centuries, even decades (Jacob et al., 2009; Weintraub, 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Buchen, 2011). These and thousands of other deleterious genetic pre- dispositions (the genes accounting for about 1700 of the 5000 - 6000 Mendelian disorders had been identified over a decade ago) cannot be accounted for in a system determined entirely by natural selection, and unless many of them can be detected in pre-gracile hominins, their widespread existence in the extant human genome can only be explained by the domestication hy- pothesis. It is the most elegant explanation ever formulated for the human condition (Bednarik, 2011a). Conclusion In other words, this alternative hypothesis, which replaces the replacement hypothesis, is not only in agreement with all the empirical evidence, being it archaeological, anthropological, or genetic; it also has astonishing explanatory power, something entirely lacking in the Eve hypothesis. It is capable of elucidat- ing the Keller and Miller paradox, explaining exclusive homo- sexuality, the shedding of estrus, the swift neotenization in re- cent humans, the rapid atrophy of human brains, the prolifera- tion of mental illness and all other neuropathology, and of countless other genetically based disorders and conditions. It explains comprehensively the human condition as we know it: the contradictions, tensions, and paradoxes accounting for the complexities of human nature. The domestication hypothesis is even capable of explaining how recent humans compensated cognitively for their rapid brain size reduction (Bednarik, in press), a simple issue that is so fundamental to the nature of our sub-species that it cannot be overemphasized. By comparison, the replacement hypothesis explains practically nothing. Two considerations emerge from this insight. First, it needs to be asked why such an unlikely model as the “African Eve hypothesis” ever gained such wide, almost universal acceptance. Its popularity appears to be attributable to the feel-good sub- liminal message that all extant humans are essentially distant cousins. It also seems to express a faint feminist message, and the idea that Africans, as the source of us all, should not be dis- criminated against. These wholesome notions may be very com- mendable, but they cannot change that the hypothesis also ra- tionalizes genocide, explaining it as an inevitable process—a rather less opportune aspect. But a more rational perspective which needs to be asked: is it the role of science to exercise moral acumen in presenting its findings, or does science strive to operate as a detached agent and present its findings without any subliminal perspective? The question is not whether it suc- ceeds in this, but merely what it aims for. The second consideration follows on from the first. The re- placement of humanist psychology with scientific modes of investigation is a symptom of the inevitable general process of supplanting the “soft sciences” with the “hard” (Becher, 2001; Bednarik, 2011a), a slow but inevitable course. Just as astro- logy was replaced with astronomy, or phrenology with neuro- science, in many of its practices traditional archaeology lacks the rigor of a scientific discipline. Phenomena that are of in- terest to it, such as behavior, thinking, intention, or personality, cannot be quantified effectively and with a semblance of ob- jectivity by the humanities (cf. Panksepp, 1998). The impro- bably high support research which has reported for initial hypo- theses in such humanities as psychology and psychiatry (Sterl- ing, 1959; Klamer et al., 1989; Fanelli, 2010) is several times that yielded in the hard sciences, indicating systematic bias. The logical and methodological rigor employed to test hypo- theses varies systematically across disciplines and fields. Papers in psychology, psychiatry, and business studies report positive testing of hypotheses five times as often as space science, while the biological disciplines rank intermediate. Studies applying Open Access 222  R. G. BEDNARIK behavioral and social methodologies on people rank 3.4 times hi- gher than physical and chemical studies on non-biological ma- terial, using the same index of confirmation bias (Press & Tanur, 2001). The social sciences are thus qualitatively differ- rent from the hard sciences (Shipman, 1988; Latour, 2000; Si- monton, 2004; Bishop, 2007; Bednarik, 2011a), and psycho- logy and psychiatry, for instance, “pretend to be sciences, off- ering allegedly empirical observations about the functions and malfunctions of the human mind” (Szasz, 2006). Yet they are still considerably more rigorous than Pleistocene archaeology, arguably the softest of the “soft sciences” (Bednarik, 2013b). This is most apparent in investigating the epistemology of the “African Eve” or replacement hypothesis, which became incredibly popular without presenting comprehensive empirical evidence and without really explaining anything with its central proposition. Initially based on a 1970s hoax that was uncovered in 2003/4, it has very adversely affected the course of the disci- pline for two or three decades, through its biases against com- peting theories. The inherent practice of Pleistocene archae- ology, evident since the times of Boucher de Perthes and Pen- gelly, of stifling dissent rather than addressing it continues to determine the discipline’s dogma. But it is not the rejection of such dissent that one should find disturbing; it is the subse- quent grudging acceptance of corrections and the inexorable watering down and inevitable corruption of the alternatives. The many historical cases all present the same pattern: ulti- mately, usually several decades later, the corrections were ac- cepted, but the discipline misinterpreted them and veered off on yet another false course. The entire discipline would not exist if the propositions of Boucher de Perthes and Pengelly had not been absorbed, and yet ever since it has inevitably rejected major corrections, throughout most of two centuries, only to eventually accept them in corrupted forms. The explanation of this “inverted falsificationism” is beyond the scope of the pre- sent paper, but it has been attempted (Bednarik, 2013b). In the case of the “African Eve hypothesis” this mechanism has led to the most incredible ideas. Among them are the pro- positions that only H. sapiens sapiens are human (even by some geneticists), that all earlier hominins should rightly belong to the apes (Davidson & Noble, 1990), that the use of language and symbolism began with the “Moderns”, that these were un- able to breed with any other hominins, and that they are su- perior to the Robusts in a whole raft of ways. The last-mention- ed shows that Pleistocene archaeology has never addressed the most important question in the discipline: what is it that caused the development of hominins to change from an evolutionary (dysteleological) process to a teleological one? It is generally agreed that this process began as an evolutionary progression, determined essentially by Darwinian natural selection. It should also be obvious that it ended as the precise opposite: a teleo- logical, clearly not evolutionary process. In speaking of “cul- tural evolution”, archaeologists illustrate the incommensurabi- lity of their discipline and the sciences: archaeological pro- gressivism, based as it is on a Eurocentric reality construct, implicitly views development as teleological, toward “more de- veloped” forms. Regarding evolution as having an ultimate pur- pose, the creation of a superior species, is an ideologically in- spired falsity (i.e. deriving from religion), and the concept of “cultural evolution” is an oxymoron. One might say that the development and transmission of culture is by memes rather than genes, and is reversible. Thus the change from a dysteleo- logical to a teleological development is the key element in understanding the human condition (Bednarik, 2011a), and yet it has never been examined in this light. How human self-se- lection and human culture changed the process to a teleological one is therefore crucial to understanding recent hominin history. But it is incompatible with the view that supposedly modern humans (cf. Latour, 1993) are the result of a speciation event— that they are a species different from robust H. sapiens types. Their gradual appearance in four continents is attributable to culture sidelining natural selection, and all “modern” humans derive from robust populations. Hence our ancestors did not “interbreed” with them (which in the Eve model is in any case impossible as it would negate the concept of species); we are their progeny, albeit altered by a process we ourselves brought about. It involved selection in favor of neoteny—and it is called domestication. REFERENCES Ahern, J. C. M., Karavanic, I., Paunović, M., Janković, I., & Smith, F. H. (2004). New discoveries and interpretations of fossil hominids and artifacts from Vindija Cave, Croatia. Journal of Human Evo- lution, 46, 25-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2003.09.010 Allsworth-Jones, P. L. (1986). The Szeletian: Main trends, recent re- sults, and problems for resolution. In M. Day, R. Foley, & R. Wu (Eds.), The pleistocene perspective (pp. 1-25). London: Allen and Unwin. Anderson, E. (1949). Introgressive hybridization. New York: John Wi- ley and Sons. Andolfatto, P. (2001). Adaptive hitchhiking effects on genome variabi- lity. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development, 11, 635-641. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00246-X Anikovich, M. (2005). Early upper paleolithic cultures of eastern Eu- rope. Journal of World Prehistory, 6, 205-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00975550 Ashley Montagu, M. F. (1960). An introduction to physical anthropo- logy. Springfield: Thomas. Asmus, G. (1964). Kritische Bemerkungen und neue Gesichtspunkte zur jungpaläolithischen Bestattung von Combe-Capelle, Périgord. Eiszeitalter and Gegenwart, 15, 181-186. Atkinson, Q. D. (2011). Phonemic diversity supports a serial founder effect model of language expansion from Africa. Science, 332, 346- 349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1199295 Awadalla, P., Eyre-Walker, A., & Maynard Smith, J. (1999). Linkage disequilibrium and recombi-nation in hominid mitochondrial DNA. Science, 286, 2524-2525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5449.2524 Ayala, F. J. (1996). Response to Templeton. Science, 272, 1363-1364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.272.5266.1363b Bächler, E. (1940). Das Alpine Paläolithikum der Schweiz. Basle: Mo- nographien zur Urund Frühgeschichte der Schweiz. Bada, J., & Masters Helfman, P. (1976). Application of amino acid ra- cemization dating in paleoanthropology and archaeology. Extrait du Colloque de l’U.I.S.P.P., Union Internationale des Sciences Préhis- toriques-Protohistoriques, 39-63. Badcock, C. R. (1980). The psychoanalysis of culture. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Bader, O. N. (1978). Sungir’: Verkhnepaleoliti-cheskaya stoyanka. Mo- scow: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka”. Bailey, D. H., & Geary, D. C. (2009). Hominid brain evolution: Testing climatic, ecological, and social competition models. Human Nature, 20, 67-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12110-008-9054-0 Barberi, F., Innocenti, F., Lirer, L., Munno, R., Pescatore, T. S., & San- tacroce, R. (1978). The campanian ignimbrite: A major prehistoric eruption in the Neapolitan area (Italy). Bulletin of Volcanology, 41, 10-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02597680 Barinaga, M. (1992). “African Eve” backers beat a retreat. Science, 255, 686-687. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1738842 Bayer, J. (1929). Wildkirchlikultur. Eis zeit und Urgeschi chte, 6, 142. Open Access 223  R. G. BEDNARIK Becher, T. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bedi, K. S., & Bhide, P. G., (1988). Effects of environmental diversity on brain morphology. Early Human Development, 17, 107-143. Bednarik, R. G. (1991). “African Eve” a computer bungle. The Artefact, 14, 34-35. Bednarik, R. G. (1992). Palaeoart and archaeological myths. Cambri- dge Archaeological Journal, 2, 27-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959774300000457 Bednarik, R. G. (1993). Wall markings of the cave bear. Studies in Spe- leology, 9, 51-70. Bednarik, R. G. (1994). The Pleistocene art of Asia. Journal of World Prehistory, 8, 351-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02221090 Bednarik, R. G. (1995). Concept-mediated marking in the Lower Palae- olithic. Current Anthropology, 36, 605-634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/204406 Bednarik, R. G. (1997). The origins of navigation and language. The Artefact, 20, 16-56. Bednarik, R. G. (1999). Maritime navigation in the lower and middle palaeolithic. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences Paris, Earth and Planetary Sciences, 328, 559-563. Bednarik, R. G. (2003). The earliest evidence of palaeoart. Rock Art Research, 20, 89-135. Bednarik, R. G. (2007). Antiquity and authorship of the Chauvet rock art. Rock Art Research, 24, 21-34. Bednarik, R. G. (2008a). The mythical moderns. Journal of World Pre- history, 21, 85-102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10963-008-9009-8 Bednarik, R. G. (2008b). The domestication of humans. Anthropologie, 46, 1-17. Bednarik, R. G. (2011a). The human condition. New York: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-9353-3 Bednarik, R. G. (2011b). Genetic drift in recent human evolution? In K. V. Urbano, (Ed.), Advances in genetics research, Volume 6 (pp. 109- 160). New York: Nova Science Publishers. Bednarik, R. G. (2011c). The origins of human modernity. Humanities, 1, 1-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/h1010001 Bednarik, R. G. (2012). An aetiology of hominin behaviour. Homo— Journal of Comparative Human Biology, 63, 319-335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchb.2012.07.004 Bednarik, R. G. (2013a). The origins of modern human behavior. In R. G. Bednarik (Ed.), The psychology of human behaviour (pp. 1-58). New York: Nova Press. Bednarik, R. G. (2013b). Creating the human past. Oxford: Ar- chaeopress. Bednarik, R. G. (in press). Doing with less: Hominin brain atrophy. Homo—Journal of Com p a r a t i v e H u m a n Biology. Bednarik, R. G., & Helvenston, P. A. (2012). The nexus between neu- rodegeneration and advanced cognitive abilities. Anthropos, 107, 511-528. Bennett, E. L., Diamond, M. C., Krech, D., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (1964). Chemical and anatomical plasticity of brain. Science, 146, 610-619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.146.3644.610 Bertone, J. (2006). Equine geriatric medicine and surgery. St. Louis, MI: W. B. Saunders. Bickerton, D. (2010). Adam’s tongue: How humans made language, how language made humans. New York: Hill and Wang. Bischoff, J. L., Ludwig, K. R., Garcia, J. F., Carbonell, E., Vaquero, M., Stafford, T. W., & Jull, A. J. T. (1994). Dating of the basal Aurignacian sandwich at Abric Romani (Catalunya, Spain) by radio- carbon and uranium series. Journal of Archaeological Science, 21, 541-551. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1994.1053 Bishop, R. C. (2007). The philosophy of the social sciences: An intro- duction. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. Boucher de Perthes, J. (1847). Antiquités celtiques et antédiluviennes. Paris: Treuttel et Wurtz. Brace, C. L. (1993). “Popscience” versus understanding the emergence of the modern mind. Review of Origins of the modern mind: Three stages in the evolution of culture and cognition, by Merlin Donald. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16, 750-751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00032672 Brace, C. L. (1999). An anthropological perspective on “race” and intelligence: The non-clinal nature of human cognitive capabilities. Journal of Anthropolog i c a l Research, 55, 245-264. Bräuer, G. (1980). Die morphologischen Affinitäten des jungpleisto- zänen Stirnbeins aus dem Elbmündungsgebiet bei Hahnöfersand. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 71, 1-42. Bräuer, G. (1984). Präsapiens-Hypothese oder Afro-europäische Sapiens- Hypothese? Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 75, 1-25. Brodar, S. (1957). Zur Frage der Höhlenbärenjagd und des Höhlen- bärenkults in den paläolithischen fundstellen Jugoslawiens. Quartär, 9, 147-159. Brookfield, J. F. Y. (1997). Importance of ancestral DNA ages. Nature, 388, 134. Buchen, L. (2011). When geeks meet. Nature, 479, 25-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/479025a Cabrera Valdés, V., & Bischoff, J. (1989). Accelerator 14C dates for early upper palaeolithic (basal Aurignacian) at El Castillo Cave (Spain). Journal of Archaeological Science, 16, 577-584. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(89)90023-X Campbell, M. C., & Tishkoff, S. A. (2010). The evolution of human genetic and phenotypic variation in Africa. Current Biology, 20, R166-R173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.050 Cann, R. L. (2002). Human evolution: Tangled genetic routes. Nature, 416, 32-33. Cann, R. L., Stoneking, M., & Wilson, A. C. (1987). Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature, 325, 31-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/325031a0 Carlier, L., Couprie, J., Maire, A. le, Guilhaudis, L., Milazzo, I., Gondry, M., Davoust, D., Gilquin, B., & Zinn-Justin, S. (2007). So- lution structure of the region 51-160 of human KIN17 reveals an atypical winged helix domain. Protein S c i e n c e , 16, 2750-2755. http://dx.doi.org/10.1110/ps.073079107 Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Piazza, A., Menozzi, P., & Mountain, J. (1988). Reconstruction of human evolution: Bringing together genetic, ar- chaeological, and linguistic data. Proceedings of the National Aca- demy of Sciences of the United States of America, 85, 6002-6006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.16.6002 Chiaroni, J., Underhill, P. A., & Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (2009). Y-chro- mosome diversity, human expansion, drift, and cultural evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United Sta- tes of America, 106, 20174-20179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0910803106 Churchill, S. E., & Smith, F. H. (2000a). A modern human humerus from the early Aurignacian of Vogelherdhöhle (Stetten, Germany). American Journal of Physica l Anthropology, 112, 251-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(2000)112:2<251::AID-A JPA10>3.0.CO;2-G Churchill, S. E., & Smith, F. H. (2000b). Makers of the early Aurigna- cian of Europe. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 113, 61-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1096-8644(2000)43:31+<61::AID-AJPA4> 3.0.CO;2-3 Conard, N. J., Grootes, P. M., & Smith, F. H. (2004). Unexpectedly recent dates for human remains from Vogelherd. Nature, 430, 198- 201. Consens, M. (2006). Between artefacts and egofacts: The power of as- signing names. Rock Art Research, 23, 79-84. Cruciani, F., Santolamazza, P., Shen, P., Macaulay, V., Moral, P., Olc- kers, A., Modiano, D. et al. (2002). A back migration from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa is supported by high-resolution analysis of hu- man Y-chromosome haplotypes. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 70, 1197-1214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/340257 Czarnetzki, A. (1983). Zur Entwicklung des Menschen in Südwest- deutschland. In H. M. Beck (Ed.), Urgeschichte in Baden-Württem- berg (pp. 217-240). Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss. Davidson, I., & Noble, W. (1990). Tools, humans and evolution: The relevance of the Upper Palaeolithic. Paper presented to the sympo- sium Tools, language and intelligence: Evolutionary implications, Cascais. De Beer, G. R. (1930). Embryology and evolutio n. Oxford: Oxford Uni- versity Press. De Beer, G. R. (1940). Embryos and ancestors. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Open Access 224  R. G. BEDNARIK versity Press. De Miguel, C., & Henneberg, M. (2001). Variation in hominid brain size: How much is due to method? Homo—Journal of Comparative Human Biology, 52, 3-58. d’Errico, F. (1995). Comment on Bednarik, R. G., “Concept-mediated markings of the Lower Palaeolithic”. Current Anthropology, 36, 618- 620. D’Errico, F., & Villa, P. (1997). Holes and grooves: The contribution of microscopy and taphonomy to the problem of art origins. Journal of Human Evolution, 33, 1-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1997.0141 Dubois, E. (1894). Pithecanthropus erectus, eine menschenähnliche Übergangsform aus Java. Batavia, Netherlands: Landersdruckerei. Eckhardt, R. B. (2000). Human paleobiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542367 Eswaran, V. (2002). A diffusion wave out of Africa. Current Anthro- pology, 43, 749-774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/342639 Evans, P. D., Gilbert, S. L., Mekel-Bobrov, N., Vallender, E. J., Ander- son, J. R., Vaez-Azizi, L. M., Tishkoff, S. A., Hudson, R. R., & Lahn, B. T. (2005). Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans. Scien ce , 309, 1717-1720. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1113722 Ewans, W. J. (1983). The role of models in the analysis of molecular genetic data, with particular reference to restriction fragment data. In B. S. Weir (Ed.), Statistical analysis of DNA sequence data (pp. 45-73). New York: Marcel Dekker. Facorellis, Y., Kyparissi-Apostolika, N., & Maniatis, Y. (2001). The cave of Theopetra, Kalambaka: Radiocarbon evidence for 50,000 years of human presence. Radiocarbon, 43, 1029-1048. Falk, D. (2009). Finding our tongues: Mothers, infants and the origins of language. New York: Basic Books. Fanelli, D. (2010). “Positive” results increase down the hierarchy of the sciences. PLoS ONE, 5, e10068. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010068 Fedele, F. G., & Giaccio, B. (2007). Paleolithic cultural change in western Eurasia across the 40,000 BP timeline: Continuities and en- vironmental forcing. In P. C. Reddy (Ed.), Exploring the mind of an- cient man. Festschrift to Robert G. Bednarik (pp. 292-316) New Delhi, India: Research India Press. Fedele, F. G., Giaccio, B., Isaia, R., & Orsi, G. (2002). Ecosystem impact of the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption in Late Pleistocene Europe. Quaternary Research, 57, 420-424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/qres.2002.2331 Fedele, F. G., Giaccio, B., Isaia, R., & Orsi, G. (2003). The Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, Heinrich Event 4, and Palaeolithic change in Europe: A high-resolution investigation. In Volcanism and the earth’s atmosphere (pp. 301-325). Washington DC: Geophysical Monograph 139, American Geophysical Union. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/139GM20 Felgenhauer, F. (1959). Das Paläolithikum von Willendorf in der Wachau, Niederösterreich. Vorbericht über die monographische Bear- beitung. Forschun g e n u n d Fortschritte, 33, 152-155. Frayer, D. W., Wolpoff, M. H., Smith, F. H., Thorne, A. G., & Pope, G. G. (1993). Theories of modern human origins: The paleontological test. American Anthropology, 95, 14-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aa.1993.95.1.02a00020 Fuhlrott, C. J. (1859). Menschliche Überreste aus einer Felsengrotte des Düsselthals. Ein Beitrag zur Frage über die Existenz fossiler Men- schen. Verhandlungen des Naturhistorischen Vereins Preussen und Rheinland Westphalen, 1 6, 131-153. Gábori-Csánk, V. (1993). Le Jankovichien: Une Civilisation Paléolithi- ques en Hongrie. Liège, Belgium: ERAUL 53. Garrigan, D., Mobasher, Z., Severson, T., Wilder, J. A., & Hammer, M. F. (2005). Evidence for archaic Asian ancestry on the human X chromosome. Molecular Biological Evolution, 22, 189-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi013 Geay, P. (1957). Sur la découverte d’un squelette aurignacien? en Charente-Maritime. Bulletin de la Société Préhistoroque Française, 54, 193-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/bspf.1957.5985 Geigl, E.-M. (2002). Why ancient DNA research needs taphonomy. Paper presented to Conférence ICAZ, Bi oshere to Lithosphere . Germonpré, M., Sablin, M. V., Stevens, R. E., Hedges, R. E. M., Hofreiter, M., Stiller, M., & Després, V. R. (2009). Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes. Journal of Archaeo- logical Science, 36, 473-490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033 Gibbons, A. (1998). Calibrating the mitochondrial clock. Science, 279, 28-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5347.28 Gieseler, W. (1974). Die Fossilgeschichte des Menschen. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss. Golenberg, E. M., Bickel, A., & Weihs, P. (1996). Effect of highly fragmented DNA on PCR. Nucleic Acids Research, 24, 5026-5033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/24.24.5026 Grammer, K., & Thornhill, R. (1994). Human facial attractiveness and sexual selection: The role of symmetry and averageness. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 1 0 8, 233-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233 Green, R. E., Krause, J., Ptak, S. E., Briggs, A. W., Ronan, M. T., Simons, J. F., Du, L., Egholm, M., Rothberg, J. M., Paunovic, M., & Pääbo, S. (2006). Analysis of one million base pairs of Neanderthal DNA. Nature, 444, 330-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature05336 Green, R. E., Krause, J., Briggs, A. W., Maricic, T. et al. (2010). A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science, 328, 710-722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1188021 Grine, F. E., Bailey, R. M., Harvati, K., Nathan, R. P., Morris, A. G., Henderson, G. M., Robot, I. et al. (2007). Late Pleistocene human skull from Hofmeyr, South Africa, and modern human origins. Sci- ence, 315, 226-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1136294 Grine, F. E., Gunz, P., Betti-Nash, L., Neubauer, S., & Morris, A. G. (2010). Reconstruction of the late Pleistocene human skull from Hofmeyr, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 59, 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.02.007 Grün, R., & Stringer, C. B. (1991). Electron spin resonance dating and the evolution of modern humans. Archaeometry , 33, 153-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1991.tb00696.x Gutierrez, G., & Marin, A. (1998). The most ancient DNA recovered from amber-preserved specimen may not be as ancient as it seems. Molecular Biological Evolution, 15, 926-929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025998 Gutierrez, G., Sanchez, D., & Marin, A. (2002). A reanalysis of the ancient mitochondrial DNA sequences recovered from Neandertal bones. Molecular Biological Evolution, 1 9 , 1359-1366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004197 Gyllensten, U., Wharton, D., Josefsson, A., & Wilson, A. C. (1991). Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in mice. Nature, 352, 255-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/352255a0 Haldane, J. B. S. (1932). The causes of evolution. London: Longmans, Green & Co.; New York: Harper Brothers. Hammer, M. F. (1995). A recent common ancestry for human Y chro- mosomes. Nature, 378, 376-378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/378376a0 Hare, E. H. (1988). Schizophrenia as a recent disease. The British Jour- nal of Psychiatry, 153, 521-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.153.4.521 Hardy, J., Pittman, A., Myers, A., Gwinn-Hardy, K., Fung, H. C., Silva, R. de, Hutton, M., & Duckworth, J. (2005). Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens. Biochemical Society Transactions, 33, 582-585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BST0330582 Harpending, H. C., Batzer, M. A., Gurven, M., Jorde, L. B., Rogers, A. R., & Sherry, S. T. (1998). Genetic traces of ancient demography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95, 1961-1967. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.4.1961 Hartl, D., & Clark, A. (1997). Principles of population genetics. Sun- derland, MA: Sinauer. Hedges, S. B., Kumar, S., Tamura, K., & Stoneking, M. (1992). Human origins and analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Science, 255, 737-739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1738849 Hellenthal, G., Auton, A., & Falush, D. (2008). Inferring human colonization history using a copying model. PLoS Genetics, 4, e1000078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000078 Open Access 225  R. G. BEDNARIK Henke, W., & Protsch, R. (1978). Die Paderborner Calvaria—ein dilu- vialer Homo sapiens. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 36, 85-108. Henke, W., & Rothe, H. (1994). Paläoanthropologie. Berlin. Henneberg, M. (1988). Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene. Human Biology, 60, 395-405. Henneberg, M. (1990). Brain size/body weight variability in Homo sapiens: Consequences for interpreting hominid evolution. Homo— Journal of Comparati v e H u m an Biology, 39, 121-130. Henneberg, M. (2004). The rate of human morphological microevo- lution and taxonomic diversity of hominids. Studies in Historical Anthropology, 4, 49-59. Henneberg, M., & Steyn, M. (1993). Trends in cranial capacity and cra- nial index in Subsaharan Africa during the Holocene. American Jour- nal of Human Biology, 5, 473-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.1310050411 Henry-Gambier, D. (2002). Les fossiles de Cro-Magnon (Les-Eyzies- de-Tayac, Dordogne): Nouvelles données sur leur position chrono- logique et leur attribution culturelle. Bulletins et mémoires de la So- ciété d’Anthropologie de Paris, 14, 89-112. Horrobin, D. F. (1998). Schizophrenia: The illness that made us human. Medical Hypotheses 50, 269-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9877(98)90000-7 Horrobin, D. F. (2001). The madness of Adam and Eve: How schizo- phrenia shaped hu manity. New York: Bantam. Hublin, J. J., Spoor, F., Braun, M., Zonneveld, F., & Condemi, S. (1996). A late Neanderthal associated with Upper Palaeolithic arte- facts. Nature, 381, 224-226. Burack, J. A., Charman, T., Yurmiya, N., Zelazo, P. R. eds. (2009). The development of autism: Perspectives from theory and research. London: Taylor & Francis/Routledge. Joffe, T. H. (1997). Social pressures have selected for an extended juvenile period in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 32, 593- 605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1997.0140 Jones, D. M. (1995). Sexual selection, physical attractiveness and facial neoteny: Cross-Cultural evidence and implications. Current Anthro- pology, 36, 723-748. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/204427 Jones, D. M. (1996). An evolutionary perspective on physical attrac- tiveness. Evolutionary A nth ro po logy, 5, 97-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1996)5:3<97::AID-EVA N5>3.0.CO;2-T Keller, M. C., & Miller, G. (2006). Resolving the paradox of common, harmful, heritable mental disorders: Which evolutionary genetic mo- dels work best? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 385-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06009095 Kim, Y. S., Leventhal, B., Koh, Y.-J., Fombonne, E., Laska, E., Lim, E.-C., Chun, K.-A., Kim, S.-J., Kim, Y.-K., Lee, H. et al. (2011). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 904-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101532 Klaatsch, H., & Hauser, O. (1910). Homo Aurignaciensis Hauseri. Prähistorische Zeitschrift, 1, 273-338. Klamer, A., Solow, R. M., & McCloskey, D. N. (1989). The cones- quences of economic rhetoric. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511759284 Klyosov, A. A., & Rozhanskii, I. L. (2012a). Re-examining the out of Africa theory and the origin of Europeoids (Caucasoids) in light of DNA genealogy. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 80-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2012.22009 Klyosov, A. A., & Rozhanskii, I. L. (2012b). Haplogroup R1a as the proto Indo-Europeans and the legendary Aryans as witnessed by the DNA of their current descendants. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 1- 13. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2012.21001 Klyosov, A. A., Rozhanskii, I. L., & Ryanbchen-ko, L. E. (2012). Re-examining the Out-of-Africa theory and the origin of Europeoids (Caucasoids). Part 2. SNPs, haplogroups and haplotypes in the Y- chromosome of chimpanzee and humans. Advances in Anthropology, 2, 198-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2012.24022 Klyosov, A. A., & Tomezzoli, G. T. (2013). DNA genealogy and lin- guistics. Ancient Europe. Advances in Anthropolo gy, 3, 101-111. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.32014 Kozłowski, J. K. (1990). A multiaspectual approach to the origins of the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe. In P. Mellars (Ed.), The emergence of modern humans. An archaeological perspective (pp. 419-438). Edin- burgh: Edinburgh University Press. Krings, M., Stone, A., Schmitz, R. W., Krainitzki, H., Stoneking, M., & Pääbo, S. (1997). Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of mod- ern humans. Cell, 90, 19-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80310-4 Kuhn, S. L. (1995). Mousterian lithic technology. An ecological per- spective. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kuhn, S. L.; & Bietti, A. (2000). The late middle and early Upper Pa- leolithic in Italy. In O. Bar-Yosef, & D. Pilbeam (Eds.), The geog- raphy of Neandertals and modern humans in Europe and the greater Mediterranean (pp. 49-76). Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Kuhn, S. L.; & Stiner, M. C. (2001). The antiquity of hunter-gatherers. In C. Panter-Brick, R. H. Layton, & P. Rowley-Conwy (Eds). Hunter- gatherers: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 99-142). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. (1st ed., 2nd ed. 1970). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Kyparissi-Apostolika, N. (2000). Theopetra Cave. Twelve years of excavation and research 1987 -1998. Athens: Institute for Aegean Pre- history. Kyrle, G. (1931). Die Höhlenbärenjägerstation. In O. Abel, & G. Kyrle, (Eds), Die Drachenhöhle bei Mixnitz (pp. 804-962). Vienna, Austria: Speläologische Monographien, Band 7-9. Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lindhal, T., & Nyberg, B. (1972). Rate depurination of native deoxyri- bonucleic acid. Biochemistry, 11, 3610-3618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bi00769a018 Lu, J., Tang, T., Tang, H., Huang, J., Shi, S., & Wu, C.I. (2006). The accumulation of deleterious mutations in rice genomes: A hypothesis on the cost of domestication. Trends in Genetics, 22, 126-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.004 Maddison, D. R. (1991). African origin of human MtDNA re-examined. Systematic Zoology, 40, 355. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2992327 Maddison, D. R., Ruvolo, M., & Swofford, D. L. (1992). Geographic origins of human mitochondrial DNA: Phylogenetic evidence from control region sequences. Systematic B iology, 41, 111-124. Malez, M. (1959). Das Paläolithikum der Veternicahöhle und der Bärenkult. Quartär, 11, 171-188. McDermott, F., Grün, R., Stringer, C. B., & Hawkesworth, C. J. (1993). Mass-spectrometric U-series dates for Israeli Neanderthal/early modern hominid sites. Nature, 363, 252-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/363252a0 McDougall, I., Brown, F. H., & Fleagle, J. G. (2005). Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature, 433, 733-736. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03258 Mekel-Bobrov, N., Gilbert, S. L., Evans, P. D., Vallender, E. J., Anderson, J. R., Tishkoff, S. A., & Lahn, B. T. (2005). Ongoing adaptive evolution of ASPM, a brain size determinant in Homo sapiens. Science, 309, 1720-1722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1116815 Mellars, P., & Stringer, C. (1989). Introduction. In P. Mellars, & C. Stringer (Eds.), The human revolution: Behavioural and biological perspectives on the origins of modern humans (pp. 1-14). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Mercier, N., Valladas, H., Bar-Yosef, O., Vandermeersch, B., Stringer, C., & Joron, J.-L. (1993). Thermoluminescence date for the Mous- terian burial site of Es-Skhul, Mt. Carmel. Journal of Archaeological Science, 20, 169-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1993.1012 Morris, A. A. M., & Lightowlers, R. N. (2000). Can paternal mtDNA be inherited? The Lancet, 355, 1290-1291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02106-1 Napierala, H., & Uerpmann, H.-P. (2010). A “new” Palaeolithic dog from central Europe. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 22,127-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/oa.1182 O’Connell, J. F., Hawkes, K., & Jones, N. G. B. (1999). Grand- mothering and the evolution of Homo erectus. Journal of Human Open Access 226  R. G. BEDNARIK Evolution, 36, 461-485. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jhev.1998.0285 Olson, M. V., & Varki, A. (2003). Sequencing the chimpanzee genome: Insights into human evolution and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics, 4, 20-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrg981 Palma di Cesnola, A. (1976). Le leptolithique archaïque en Italie. In B. Klíma (Ed.), Périgordien et gravettien en Europe (pp. 66-99). Nice, France: Congrès IX, Colloque XV, UISPP. Palma di Cesnola, A. (1989). L’Uluzzien: Faciès italien du Leptolithique archaïque. L’Anthropologie, 93, 783-811. Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience: The foundation of human and animal emotions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pavlov, P., Svendsen, J. I., & Indrelid, S. (2001). Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago. Nature, 413, 64-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35092552 Pennisi, E. (1999). Genetic study shakes up Out of Africa Theory. Science, 283, 1828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.283.5409.1828 Perpère, M. (1971). L’aurignacien en Poitou-Charentes (étude des collections d’industries lithiques). Doctoral thesis, University of Paris. Perpère, M. (1973). Les grands gisements aurignaciens du Poitou. L’Anthropologie, 77, 683-716. Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: The new science of language and mind. London: Penguin Books. Press, J. S., & Tanur, J. M. (2001). The subjectivity of scientists and the Bayesian approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118150634 Protsch von Zieten, R. R. R. (1973). The dating of Upper-Pleistocene Subsaharan fossil hominids and their place in human evolution: With morphological and archaeological implications. PhD thesis, Univer- sity of California, Los Angeles. Protsch, R. (1975). The absolute dating of Upper Pleistocene sub- Saharan fossil hominids and their place in human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution, 4, 297-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(75)90069-X Protsch, R., & Glowatzki, H. (1974). Das absolute Alter des paläo- lithischen Skeletts aus der Mittleren Klause bei Neuessing, Kreis Kelheim, Bayern. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 34, 140-144. Protsch, R., & Semmel, A. (1978). Zur Chronologie des Kelster- bach-Hominiden. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart, 28, 200-210. Riel-Salvatore, J., & Clark, G. A. (2001). Grave markers: Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic burials and the use of chronotypology in contemporary Paleolithic research. Current Anthropology, 42, 449- 479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/321801 Rigaud, S., d’Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., & Neumann, C. (2009). Critical reassessment of putative Acheulean Prosphaere globularis beads. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36, 25-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2008.07.001 Rightmire, G. P. (2004). Brain size and encephalization in early to Mid-Pleistocene Homo. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 124, 109-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.10346 Rodriguez-Trelles, F., Tarrio, R., & Ayala, F. J. (2001). Erratic overdispersion of three molecular clocks: GPDH, SOD, and XDH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 11405-11410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.201392198 Rodriguez-Trelles, F., Tarrio, R., & Ayala, F. J. (2002). A methodo- logical bias toward overestimation of molecular evolutionary time scales. Proceedings of the Na tional Academy of Sciences of th e United States of America, 99, 8112-8115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.122231299 Roginsky, Ya. Ya., Gerasimov, M. M., Zamyatnin, S. N., & Formozov, A. A. (1954). Zaklyuchenie po nakhodke iskopaemogo cheloveka v peshchernoi stoyanke Starosel’e bliz g. Bakhchisary. Sovetskaya Etnografiya, 1954, 39-41. Rougier, H., Milota, Ş., Rodrigo, R., Gherase, M., Sarcină, L., Moldo- van, O., Constantin, R. G., Franciscus, C., Zollikofer, P. E., Ponce de León, M., & Trinkaus, E. (2007). Peştera cu Oase 2 and the cranial morphology of early modern Europeans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 1165-1170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610538104 Rubinsztein, D. C.; Amos, W.; Leggo, J.; Goodburn, S.; Ramesar, R. S.; Old, J.; Dontrop, R.; McMahon, R.; Barton, D. E., & Ferguson-Smith, M. A. (1994). Mutational bias provides a model for the evolution of Huntington’s disease and predicts a general increase in disease prevalence. Nature Genet i c s, 7, 525-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng0894-525 Sadier, B., Delannoy, J.-J., Benedetti, L., Bourlès, D. L., Jaillet, S., Geneste, J.-M., Lebatard, A.-E., & Arnold, M. (2012). Further constraints on the Chauvet Cave artework elaboration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 8002-8006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118593109 Sautuola, M. Sanz de (1880). Breves appuntes sobre algunos obietos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander. Santander, Spain: Martínez. Schulz, H.-P. (2002). The lithic industry from layers IV-V, Susiluola Cave, western Finland, dated to the Eemian interglacial. Préhistoire Européenne, 16-17, 7-23. Schulz, H.-P., Eriksson, B., Hirvas, H., Huhta, P., Jungner, H., Purhonen, P., Ukkonen, P., & Rankama, T. (2002). Excavations at Susiluola Cave. Suomen Museo, 109, 5-45. Schulz, M. (2004). Die Regeln mache ich. Der Spiegel, 34, 128-131. Schwartz, M., & Vissing, J. (2002). Paternal inheritance of mitochon- drial DNA. New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 576-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020350 Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. London: Allen Lane. Shackelford, T. K., & Larsen, R. J. (1997). Facial asymmetry as an indicator of psychological, emotional, and physiological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72 , 456-466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.456 Shipman, M. D. (1988). The limitations of social research. London: Longman. Simonton, D. K. (2004). Psychology’s status as a scientific discipline: Its empirical placement within an implicit hierarchy of the sciences. Review of General Psychology, 8, 59-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.1.59 Smith, F. H., Janković, I., & Karavanić, I. (2005). The assimilation model, modern human origins in Europe, and the extinction of Neandertals. Quaternary Inter n a tional, 137, 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2004.11.016 Smith, F. H., & Ranyard, G. (1980). Evolution of the supraorbital region in Upper Pleistocene fossil hominids from south-central Europe. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 53, 589-610. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330530414 Smith, F. H., Trinkaus, E., Pettitt, P. B., Karavanić, I., & Paunović, M. (1999). Direct radiocarbon dates for Vindija G1 and Velika Pećina Late Pleistocene hominid remains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96, 12281- 12286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.22.12281 Soficaru, A., Doboş, A., & Trinkaus, E. (2006). Early modern humans from the Peştera Muierii, Baia de Fier, Romania. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103, 17196-17201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608443103 Sterling, T. D. (1959). Publication decisions and their possible effects on inferences drawn from tests of significance—Or vice versa. Journal of American Statistical Association, 54, 30-34. Stiner, M. C. (1994). Honor among thieves. A zooarchaeological study of Neandertal ecology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Stringer, C. B., & Andrews, P. (1988). Genetic and fossil evidence for the origin of modern humans. Science, 239, 1263-1268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.3125610 Stringer, C., & Gamble, C. (1993). In search of the Neanderthals: solving the puzzle of hu m a n origins. London: Thames & Hudson. Stringer, C. B., Grün, R., Schwarcz, H. P., & Goldberg, P. (1989). ESR dates for the hominid burial site of Es Skhul in Israel. Nature, 338, 756-758. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/338756a0 Svoboda, J. (1990). The Bohunician. In J. K. Kozłowski (Ed.), La mutation (pp. 169-192). Liège, Belgium: ERAUL. Svoboda, J. (1993). The complex origin of the Upper Paleolithic in the Czech and Slovak Republics. In H. Knecht, A. Pike-Tay, & R. White (Eds.), Before Lascaux: The complete record of the early Upper Open Access 227  R. G. BEDNARIK Open Access 228 Paleolithic (pp. 23-36). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Tattersall, I. (1995). The fossil trail: How we know what we think we know about human evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Templeton, A. R. (1992). Human origins and analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Science, 255, 737-739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1590849 Templeton, A. R. (1993). The “Eve” hypothesis: A genetic critique and re-analysis. American Anthropologist, 95, 51-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aa.1993.95.1.02a00030 Templeton, A. R. (1996). Gene lineages and human evolution. Science, 272, 1363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.272.5266.1363a Templeton, A. (2002). Out of Africa again and again. Nature, 416, 45- 51. Templeton, A. R. (2005). Haplotype trees and modern human origins. Yearbook of Physical Anth r o po l ogy, 128, 33-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20351 Terberger, T., & Street, M. (2003). Jungpaläolithische Menschenreste im westlichen Mitteleuropa und ihr Kontext. In J. M. Burdukiewicz, L. Fiedler, W.-D. Heinrich, A. Justus, & E. Brühl (Eds.), Erken- ntnisjäger: Kultur und Umwelt des frühen Menschen (pp. 579-591). Vol. 57/2, Halle, Germany: Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt, Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte. Thorne, A. G., & Wolpoff, M. H. (1981). Regional continuity in Australasian Pleistocene hominid evolution. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 55, 337-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330550308 Tobias, P. V. (1996). The evolution of the brain, language and cognition. In F. Facchini (Ed.), Colloquium VIII: Lithic-industries, language and social behaviour in the first human form (pp. 87-94). Forli. Torroni, A., Lott, M. T., Cabell, M. F., Chen, Y.-S., Lavergne, L. & Wallace, D. C. (1994). MtDNA and the origin of Caucasians: Identification of ancient Caucasian-specific haplogroups, one of which is prone to a recurrent somatic duplication in the D-loop region. Americ a n J o u r n al o f H u m a n Genetics, 55, 760-752. Trinkaus, E., Moldovan, O., Milota, Ş., Bîlgar, A., Sarcina, L., Athreya, S., Bailey, S.E., Rodrigo, R., Mircea, G., Higham, T., Bronk Ramsey, C., & van der Plicht, J. (2003). An early modern human from the Peştera cu Oase, Romania. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 11231-11236. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2035108100 Trut, L. N. (1999). Early canid domestication: The farm-fox experiment. American Scientist, 87, 160-169. Vértes, L. (1959). Die Rolle des Höhlenbären im ungarischen Paläo- lithikum. Quartär, 11, 151-170. Vigilant, L., Stoneking, M., Harpending, H., Hawkes, K., & Wilson, A. C. (1991). African populations and the evolution of human mito- chondrial DNA. Science, 253, 1503-1507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1840702 Voight, B. F., Kudaravalli, S., Wen, X., & Pritchard, J. K. (2006). A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biology, 4, e72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072 Walberg, M. W., & Clayton, D. A. (1981). Sequence and properties of the human KB cell and mouse L cell D-loop regions of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 9, 5411-5421. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/9.20.5411 Walker, L. C., & Cork, L. C. (1999). The neurobiology of aging in nonhuman primates. In R. D. Terry, R. Katzman, K. L. Bick, & S. S. Sisodia (Eds.), Alzheimer’s disease (2nd ed., pp. 233-243). New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Ward, R. H., Frazier, B. L., Dew-Jager, K., & Pääbo, S. (1991). Extensive mitochondrial diversity within a single Amerindian tribe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science s of the United States of Ameri ca, 88, 8720-8724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.19.8720 Watson, E., Bauer, K., Aman, R., Weiss, G., Haeseler, A. von, & Pääbo, S. (1996). MtDNA sequence diversity in Africa. American Journal of Human Genetics, 59, 437-444. Weiner, W. S., Oakley, K. P., & Le Gros Clark, W. E. (1953). The solution of the Piltdown problem. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology, 2, 141-146. Weintraub, K. (2011). The prevalence puzzle: Autism counts. Nature, 479, 22-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/479022a Weiss, M. L., & Mann, A. E. (1978). Human biology and behavior: An anthropological perspective. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co. White, R. (1993). Technological and social dimensions of Aurigna- cian-age body ornaments across Europe. In H. Knecht, A. Pike-Tay, & R. White (Eds.), Before Lascaux: The complex record of the Early Upper Palaeolithic (pp. 277-299). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. White, T. D., Asfaw, B., DeGusta, D., Gilbert, H., Richards, G. D., Suwa, G., & Howell, F. C. (2003). Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature, 425, 742-747. Wild, E. M., Teschler-Nicola, M., Kutschera, W., Steier, P., Trinkaus, E., & Wanek, W. (2005). Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladeč. Nature, 435, 332-335. Williams, R. S. (2002). Another surprise from the mitochondrial geno- me. New England Journal of Medicine, 34 7, 609-611. Wolpoff, M. (1999). Paleoanthropology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw- Hill. Wolpoff, M., & Caspari, R. (1996). Race and human evolution: A fatal attraction. New York: Simon & Schuster. Wolpoff, M., Smith, F. H., Malez, M., Radovčić, J., & Rukavina, D. (1981). Upper Pleistocene hominid remains from Vindija Cave, Croatia, Yugoslavia. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 54, 499-545. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330540407 Yakimov, V. P. (1980). New materials of skeletal remains of ancient peoples in the territory of the Soviet Union. In Current argument on early man: Report from a nobel symposium (pp. 152-169). Oxford: Pergamon Press. Zischler, H., Geisert, H., Haeseler, A. von, & Pääbo, S. (1995). A nuclear “fossil” of the mitochondrial D-loop and the origin of mo- dern humans. Natur e, 378, 489-492. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/378489a0 Zotz, L. F. (1951). Altsteinzeitkunde Mitteleurop as. Stuttgart: F. Enke.