Advances in Physical Education 2013. Vol.3, No.4, 175-186 Published Online November 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2013.34029 Open Access 175 Techniques Used by Elite Thai and UK Muay Thai Fighters: An Analysis and Simulation Tony Myers1, Nigel Balmer2, Alan Nevill3, Yahya Al-Nakeeb4 1Newman University, Birmingham, UK 2University College London, London, UK 3University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK 4Qatar University, Doha, Qatar Email: tony.myers@newman.ac.uk Received August 18th, 2013; revised September 18th, 2013; accepted September 26th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Tony Myers et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background: Muay Thai is a combat sport growing in international popularity. Previous research has highlighted marked jurisdictional differences in the judging systems employed, but no studies have com- pared techniques used by fighters across geographic regions or have been on how these might be a func- tion of the different judging systems employed. This paper aimed to address this issue by examining dif- ferences in technique selection and application between Thai and UK Muay Thai fighters using notational analysis. Method: The winners of thirty-two fights involving 16 Thai and 16 UK fighters were analysed. Three multilevel Poisson regression models were used to estimate differences in technique frequency and key performance indicators between Thai and UK fighters. Results: Thai fighters used more attacking and defensive techniques than UK fighters, particularly knees (p < 0.001), roundkicks to the body (p < 0.001), and push kicks (p < 0.001). Thai fighters also tended to catch an opponent’s leg significantly more often than UK fighters (p < 0.001), but UK fighters were significantly more likely to use other defensive techniques. There were also statistically significant interactions between nationality and a range of quality indicators, including delivering techniques at an appropriate distance (p < 0.001), the effectiveness of techniques used (p < 0.001), and returning to a balanced stance (p < 0.001). Conclusions: The results suggested that Thai fighters using better distancing, were more effective and more balanced. The practical implications of findings and their implications for the sport and future research are discussed. Keywords: Muay Thai; Notational Analysis; Technique Selection; Multilevel Poisson Regression Introduction For many years international boxing has been the primary televised combat sport enjoying worldwide media exposure. However, recently other combat sports have challenged this monopoly. Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) now averages over 3 million viewers for pay-per-view fights and is growing in popularity (Brown, 2011). Muay Thai, a major component of MMA, is considered to be one of the fastest growing martial arts in the world (Yuvanont, Buristrakul, & Kittimetheekul, 2010). From its martial origins it developed into Thailand’s national sport and is now practiced across the globe. Thai box- ers compete in an international style boxing ring, where they try to defeat their opponent by scoring points, knockouts or stop- pages using a range of full-contact blows delivered to most parts of the body. Legal techniques in the sport include a vari- ety of punches, elbows, knee strikes, kicks and grappling tech- niques (Board of Boxing Sport, 2002). While there are different versions of the rules applied at different levels, professional Muay Thai fighters compete in various weight categories over five three-minute rounds, punctuated by two-minute rest peri- ods (World Muaythai Council, 1995). Previous research into the sport has highlighted marked ju- risdictional differences in judging. Clear differences have been found in the judging practices in Thailand and those generally employed in the west (Myers, 2007). Interestingly, the Thai judging system seems to produce more consistency in decisions. Thai judges have been shown to have far higher levels of agreement on which fighters are considered to have won a par- ticular fight compared to western judges (Myers, Nevill, & Nakeeb, 2010). This research team not only found higher con- sistency between Thai judges’ decisions but also found that UK judges were more consistent when they were trained to apply Thai judging criteria. The judging system used internationally has also shown its susceptibility to particular judging biases. For example, international judges have been shown to be sus- ceptible to nationalistic bias (Myers et al., 2006) as well as home crowd influences with crowd noise biasing decisions (Myers & Balmer, 2012; Myers, Nevill, & Nakeeb, 2012). While we have seen judging differences systems employed across regions and differential bias too, what about the differ- ences in techniques used by fighters from different geographic regions? Anecdotal evidence points to perceptions of Thai na- tionals having a superior and quite a distinct fighting style. Could this be merely a function of the way Thai judges score fights or is the “Thai style” of fighting actually superior? While formal analysis has been scant, technical and tactical differ-  T. MYERS ET AL. ences have been identified between regional and national level fighters in the sport. Researchers found the national level fight- ers landed significantly more techniques on target (59.1% vs. 42.6%), used significantly more knees (82.1% vs. 64.9%) and delivered significantly more kicks (69.5% vs. 48.3%) than their regional counterparts (Michielon et al., 2008). If differences exist across levels in a single country, are the differences be- tween countries likely to be still greater? Performance analysis, in its various guises, has been suc- cessfully used to explore technical idiosyncrasies in a variety of sports. One popular method, notational analysis, attempts to reliably record and quantify critical aspects of sport perform- ance (Hughes & Bartlett, 2008). In practice, notational analysis is a generic term used to describe a number of different systems that use symbols to represent specific “events” such as prede- termined actions observed during competitive sport. This tech- nique offers a more objective method of monitoring and ana- lyzing performance than that obtained from subjective observa- tion. The evaluation of the data generated from this type of analysis not only provides an overview of technical and tactical aspects of performance, whether successful or unsuccessful, but also allows coaches to provide accurate feedback to athletes (Hughes & Franks, 2004). Combat sports have been the focus of notational studies, par- ticularly Karate and Taekwondo. For example, in Taekwondo technique profiles of youth taekwondo performance have been studied and identified (Casolino et al., 2012), on differences in technique frequency between medalists and non-medalists (Kwok, 2012) and differences across different weight classes and genders (Falco, Landeo, Menescardi, Bermejo, & Estevan, 2012). Ring combat sports similar in nature to Muay Thai have also received some attention. El-Ashker (2011) analyzed 33 finals and semi-finals of a national boxing championship in Cairo, Egypt in 2010. The offensive and defensive techniques used by winning and losing boxers were recorded using a hand notation system. In addition to collecting basic frequency of techniques used, there was also a retrospective calculation of effectiveness. This was achieved by applying a simple formula to frequencies of successful and unsuccessful techniques. However, effectiveness was determined by frequency of blows landed rather than on any assessment of the actual effect of the punches. While the study represents the first credible effort to use notational analysis in amateur boxing, the detail of analysis was hindered by the application of hand notation and accord- ingly its usefulness for coaches subsequently compromised. A recently developed computerized notational analysis system for amateur boxing addresses some of these issues (Thomson, Lamb, & Nicholas, 2012). Different methods have been used to evaluate quality of per- formance in terms of the technique choice and tactical decisions including differences in technique selection between elite and non-elite performers (e.g. Brown, Lauder, & Dyson, 2011; Lupo et al., 2010) and winners and losers (e.g. Csataljay et al., 2012). More pertinent to the present study, comparisons have also been made across geographical regions. Eaves and Broad (2007) compared the playing patterns of professional rugby league teams in the English Super League with teams playing in the Australian National Rugby League. Significant regional playing differences were found between the teams examined. These differences pointed to tactics that could be employed by coaches to improve English teams performance. A similar type of comparison would be beneficial in Muay Thai. As mentioned previously, there appears to be an assumption in the Muay Thai community that fighters from Thailand use a different and more effective style of fighting compared to that used by fighters in the west. However, no published studies have examined these differences or possible reasons for which should they exist. In exploring differences in performance, researchers have employed a range of different statistical analysis techniques. These range from parametric tests such as independent t-tests (Häyrinen, Hoivala, & Blomqvist, 2004; Laird & McLeod, 2009), one-way ANOVAs (Kwok, 2012) and factorial ANOVAs (El-Ashker, 2011; Ibáñez at al., 2009), as well as a range of non-parametric tests including Mann-Whitney U tests (O’Do- noghue & Ingram, 2001; Ortega, Villarejo, & Palao, 2009) and Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA by ranks (Falco et al., 2012; Lago-Peñas, 2010). While standard parametric procedures used can be appropriately applied when data are normally distributed and fulfill all other parametric assumptions, often the count data collected in notational analysis do not follow a normal distribu- tion (Nevill et al., 2002). While the non-parametric alternatives used are essentially distribution free, information is lost when transforming values into ranks, so these tests lack the statistical power of parametric tests (O’Donoghue, 2010). This lack of power means that non-parametric analysis can be insensitive to even relatively large differences (Hughes, 2004). While data generated from notational analysis are often not normally dis- tributed, they do conform to Poisson and Binomial distributions (Hughes et al., 2011; Nevill et al., 2002). Although these dis- tributions have not being widely applied in notational analysis studies, given the advantages afforded by their application, a Poisson distribution was used to model data in the present study. To make an appropriate study of the differences in tech- niques used by Thai and UK fighters, we felt it important to consider the impact of individual differences within these na- tionality groups. Although there is potential for homogeneity in fighters from the same country in terms of their technique se- lection, individual fighters are still likely to display some dif- ferences in the patterns of techniques employed, which are attributable to differing anthropometric and physiological char- acteristics. The need to consider fighter-level variance and clustering of techniques at the fighter level when exploring group differences can invalidate the use of ANOVA and tradi- tional ordinary least squares regression models (Bliese & Hanges, 2004; Kenny & Judd, 1986). Although novel in nota- tional analysis, multilevel Poisson regression analysis was con- sidered appropriate to explore differences between Thai and UK fighters. Given the paucity of objective information on technique quality and selection available to coaches and competitors in Muay Thai, the aims of this study were: 1) to describe tech- nique selection and associated key qualitative aspects of per- formance across fighters of both nationalities; 2) to determine differences between elite Thai and elite UK fighters, and; 3) to consider if previously identified judging differences might be one plausible factor in differences found. Given that top-level Thai competitors are considered to be the best technical Muay Thai fighters in the world, we consider analyzing this group essential for improving performance across the rest of the world. The study hypothesized that there would be a significant dif- ference in technique selection and application between Thai and UK fighters. Open Access 176  T. MYERS ET AL. Open Access 177 Method There would then be a prompt to enter information on: 1) the distancing prior to delivery; 2) if the technique was delivered on balance or not; 3) the speed of technique; 4) the result of the technique; 5) its effect; 6) if the fighter returned to a balanced stance, and; 7) if the technique was followed immediately by another technique. After this qualitative information was en- tered, the software automatically returned to the initial screen, ready for the operator to enter information on the next tech- nique. Participants Muay Thai technique selection and application of two groups of 16 professional Muay Thai fighters were assessed during competition in this study (total of 32 fighters). Only the winners of the 32 bouts were analysed. The first group consisted of 16 male Muay Thai fighters of Thai nationality in weight classes’ 50 kg to 63.5 kg (Mean = 54.97, SD = 4.60). All Thai fighters were Thai champions. The ages of the Thai group ranged from 17 to 24 years (Mean = 20.75, SD = 1.98). The second group consisted of 16 male Muay Thai fighters from the UK compet- ing in weight classes’ 57 kg to 71 kg (Mean = 63.38, SD = 5.09). All UK fighters were UK champions. The age of the UK fighters ranged from 18 to 29 years (Mean = 24.38, SD = 3.67). The program was written so that information entered via the interactive screens was automatically recorded chronologically in a Microsoft Excel worksheet. The program provided text details and number references for each technique recorded. The text details were intended to help “eyeballing” of data patterns, and the number references to help speed up data totaling. A range of attacking (see Figure 1) and defensive techniques (see Figure 2) were analysed using the software, along with some associated key quality indicators. Performance aspects that were recorded related to the scoring criteria used by judges using the Thai system and judges using the UK system. These included: 1) the frequency of attacking techniques; 2) the type of technique used; 3) the target of the technique; 4) the effect of the technique; 5) balance before and after delivery and distanc- ing, and finally; 6) if the technique was part of a combination of techniques. The type and success of defensive techniques were also recorded. These included: the frequency of particular de- fensive techniques, the type of defensive techniques used, the effectiveness of the defense, balance after the defense and if it was followed immediately by a counter attack. Procedure All fights were presented in a digitally recorded format and included complete footage of each fight. The videos were not recorded specifically for the purpose of the study and as such included footage of more than one angle. All of the fights com- prised of five rounds, each three minutes in duration. All fights analysed involved evenly matched competitors. Notational analysis software was written in Visual Basic programming language. It was written specifically for the pur- pose of notational analysis of Muay Thai. The program was written to enable data to be entered via a mouse being “clicked” over appropriately labeled data “buttons” displayed on one of three interactive screens. The initial screen was designed as an interactive interface allowing the analyst to enter basic attack or defense technique details. The program allowed initial tech- nique details to be entered and then automatically displayed a further screen allowing qualitative information on the attack or defense being analyzed. For example, if the fighter being ana- lyzed had delivered a right round kick to the body the program allowed the operator to “click” the mouse button over the “right round kick to the body” button. The attack screen would then be automatically displayed allowing the operator to enter quali- tative variables associated with that technique. When an attacking technique was identified, the following additional information was recorded on the Excel spreadsheet: 1) balance before delivery, recorded as either “on balance” or “off balance”; 2) the result of the technique, recorded as ei- ther ”hit”, “missed”, “evaded”, “blocked”, “caught”, “coun- tered”, “caught body”, “caught neck”, or “thrown”; 3) the effect of the technique on the opponent, recorded as having “no ef- fect”, “some effect”, or “highly effective”; 4) balance and physical composure after technique delivery, recorded as “re- turned to a balanced” stance or “didn’t return to a balanced stance”, and finally; 5) an assessment was made of whether the Figure 1. Hierarchy of attacking techniques.  T. MYERS ET AL. Figure 2. Hierarchy of defensive techniques. technique formed part of a combination or not. This was re- corded as either “followed immediately by another technique” or “not continued”. When a defensive technique was identified, the following additional information was recorded on the Excel spreadsheet: 1) the technique used by the opponent in their attack; 2) balance on defense delivery, recorded as either “on balance” or “off balance”; 3) then result of the opponent’s technique recorded as either” hit”,” missed”, “evaded”, “blocked”, “caught”, “coun- tered”, “caught body”, “caught neck”, or “thrown”; 4) the effect of the defense, recorded as having ”no effect”, “some effect”, or as “highly effective”; 5) balance and physical composure after defense delivery, recorded “as returned to a balanced stance” or “didn’t return to a balanced stance”, and finally; 6) if the defensive action was followed immediately by an attacking technique or not. This was recorded as either “continued” or “not continued”. After each fight the information generated by the software from each round was summarized manually onto a fight sum- mary spreadsheet. After the fights involving UK fighters, the summary data was transferred to another spreadsheet. This was repeated for data notated from the Thai competitors. Reliability Intra and inter-observer reliability testing was carried out on the computerized notational system. The same system was em- ployed as used by Blomqvist, Luhtanen, and Laakso (1998) to calculate the reliability of data generated by a computerized notational analysis system used in badminton. An observer notated a single fight, then after a two-week period re-notated the same fight. A second observer also notated the same fight. Data was compared and percentages of agreement calculated for each variable. The fight notated for the reliability study included one hun- dred and fifty-four techniques. The highest intra-observer agreement were found in the following: “technique selection”, “balance on delivery”, “result”, “effect”, “balance after deliv- ery” and “continued” (100%), the lowest were found in “speed of delivery” (98.35%). The highest inter-observer agreement was found in “technique selection”, “result” and “continued” (100%), the lowest in “speed of delivery” (97.7%). These results indicated that the notational analysis system used in the study was reliable for evaluating the variables ex- amined in this study. Data Analysis First, descriptive statistics of the overall frequency of attack- ing techniques, defensive techniques and quality indicators were calculated, and then the frequency of specific techniques with their associated quality indicators (mean frequencies of the specific techniques delivered at an appropriate distance, tech- niques delivered on balance, balance following the technique, and techniques had some effect). Second, multilevel Poisson regression models were used to explore whether the frequency of techniques or indicators of different types varied signifi- cantly by fighter nationality. The models compared the fre- quency of techniques/indicators of different types used over 32 bouts by sixteen Thai and sixteen UK fighters (only the winners of the bouts were analysed). Multilevel models were used since the frequencies of techniques of each type were nested within fighters, with the two-level models fitted using MLwiN (Ras- bash et al., 2012). Failure to consider this type of data structure can result in a number of practical and technical difficulties, including the underestimation of the standard errors associated with regression coefficients (Rasbash et al., 2012). Three models were fitted; the first modeling frequency of at- tacking techniques (see Table 1), the second frequency of de- fensive techniques (see Table 2) and the third frequency of technique quality indicators (see Table 3). In the first model, independent variables were nationality of fighter (UK vs. Thai), offensive technique type (with “clinching for attack” as the reference category) and the interaction between nationality and offensive technique type. The second model mirrored the first, though offensive technique type was replaced by defensive technique type (with “catch leg” as the reference category). The third model again mirrored the previous two models, but with technique type replaced with quality of technique indicators (with “appropriate distance” as the reference category). Model estimates were then used to examine differences in the rates of different offensive and defensive techniques between UK and Thai fighters. For offensive techniques, defensive techniques and quality indicators, the models were then used to simulate mean frequencies of techniques/indicators of each type for Thai and UK fighters. These mean frequencies are displayed in Fig- ures 3 to 5. Open Access 178  T. MYERS ET AL. Table 1. Two level multilevel Poisson model of fighter’s frequency of attacking techniques by nationality and technique type. Parameter Level Model Coefficient Standard Error Fixed Constant 2.83 0.10 Nationality UK 0.00 - Thai −0.27 0.14 Technique Clinching for attack 0.00 - Knees −0.77 0.10 Legal throw −1.90 0.16 Punches 0.39 0.08 Roundkick to leg −0.44 0.09 Roundkick to body/neck 0.03 0.08 Teep (push kick) −0.68 0.10 Nationality × Technique Thai × Knees 1.11 0.14 Thai × Legal throw −0.46 0.28 Thai × Punches −0.08 0.12 Thai × Roundkick to leg 0.28 0.14 Thai × Roundkick to body/neck 0.92 0.12 Thai × Teep (push kick) 1.26 0.13 Random Fighter-level variance 0.09 0.03 Note: *Values in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Table 2. Two level multilevel Poisson model of fighter’s frequency of defensive techniques by nationality and technique type. Parameter Level Model Coefficient Standard Error Fixed Constant −0.83 0.39 Nationality UK 0.00 - Thai 2.08 0.41 Technique Catch leg 0.00 - Defend using clinch 2.46 0.39 Evade by stepping 2.13 0.40 Leg Block raised 0.36 0.49 Other 3.09 0.39 Skip/sway back 0.54 0.48 Nationality × Technique Thai × Defend using clinch −1.25 0.42 Thai × Evade by stepping −0.03 0.42 Thai × Leg block raised 0.18 0.52 Thai × Other −5.04 0.54 Thai × Skip away/back 0.11 0.50 Random Fighter-level variance 0.09 0.03 Note: *Values in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Open Access 179  T. MYERS ET AL. Table 3. The two level multilevel Poisson model of fighter’s frequency of quality indicators by nationality and technique type. Parameter Level Model Coefficient Standard Error Fixed Constant 4.21 0.09 Nationality UK 0.00 - Thai 0.53 0.12 Indicator Appropriate distance 0.00 - Delivered on balance 0.00 0.04 Effect −0.46 0.05 Returned to balanced stance −0.20 0.05 Nationality × Indicator Thai × Delivered on balance 0.04 0.05 Thai × Effect 0.23 0.06 Thai × Returned to balanced stance 0.17 0.06 Random Fighter-level variance 0.11 0.03 Note: *Values in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Figure 3. Mean frequency (and SD) of each attacking technique for Thai and UK fighters, simulated from the statistical model in Table 1. Results Overall Frequency of Techniques across Groups Overall the 32 bouts yielded a total of 3500 offensive tech- niques (with a mean of 110.31 per fighter), 1283 defensive techniques (mean of 39.84 per fighter) with 31336 quality indi- cators associated with the techniques recorded (mean of 979.25 per fighter). With regard to overall number of techniques, Thai fighters delivered more attacking techniques (mean of 124.06, SD = 14.94) than UK fighters (mean of 96.56, SD = 3.02). Ta- ble 4 shows the mean number of attacking techniques and qual- ity indicators of different types (per fighter). Across both groups, kicking techniques were the most fre- quent attack across fighters followed by punches and then knees. The most frequently used punching technique was the straight punch (mean of 18.72, SD = 9.43), followed by hook punches (mean of 3.38, SD = 1.62) and lastly the uppercut (mean of 0.41, SD = 0.32). Targets used for attacks included legs, body, head and neck. The most frequently attacked targets across groups were the body (mean of 49.23, SD = 11.24), fol- lowed by the head and neck (mean of 20.92, SD = 3.47) and legs (mean of 13.03, SD = 5.12). Thai fighters targeted the body most frequently (mean of 59.97 ± 19.17), followed by the head (mean of 16.44 ± 5.87) and then the legs (mean of 13, SD = 10.34). UK fighters favored the head (mean of 25, SD = 3.18) as their primary target, followed by the body (mean of 19.25, SD = 3.31) and then the legs (mean of 13.06, SD = 3.34). Blocking using the raised leg was the most frequently used defense across groups (mean of 9.47, SD = 11.79), followed by clinching an opponent to prevent their attacks (mean of 8.44, SD = 6.16), then the combined use of a range of techniques (mean of 6.81, SD = 2.07), evading a technique by stepping Open Access 180  T. MYERS ET AL. Figure 4. Mean frequency of each defensive technique for Thai and UK fighters, simulated from the sta- tistical model in Table 2. Figure 5. Mean frequency of qualitative indicators for Thai and UK fighters, simulated from the statis- tical model in Table 3. (mean of 4.84, SD = 7.10), skipping or swaying away from a technique (mean of 3.72, SD = 4.49) and catching the leg (mean of 1.34, SD = 2.39). Overall, Thai fighters used a greater number of defensive techniques (mean of 55.94, SD =13.85) than their UK counterparts (mean of 20.25, SD = 1.58). As can be seen in Table 1, there was a significant interaction between attacking technique type and fighter nationality, in particular a number of techniques far more common for Thai fighters. Compared to the reference technique category “clin- ching for attack”, which Thai fighters were less likely to per- form (though the difference fell marginally short of signifi- cance; testing the model term, χ21 = 3.64, p = 0.056), there were highly significant increases in the frequency of “knees” (χ21 = 65.17, p < 0.001), “roundkicks to body/neck” (χ21 = 90.74, p < 0.001) and “teeps” (χ21 = 64.13, p < 0.001) for Thai fighters when compared to their UK counterparts, as indicated by the significant positive interaction terms for these techniques. Differences are also illustrated in Figure 1. As shown, Thai fighters were somewhat less likely to perform “clinching to attack”, “legal throws” and “punches”, but far more likely to perform “knees” (11.0 more per bout on average), “roundkicks to body/neck” (17.1 more per bout on average) and “teeps” (15.4 more per bout on average). The significant fighter-level variance term indicated that there was clustering in the fre- quency of techniques by fighter, highlighting the importance of correctly accounting for the hierarchical structure in the data. As shown in Table 2, as with attacking techniques, there was evidence of highly significant differences between Thai and UK fighters in the frequency of defensive techniques of different types. Referring to the reference category technique “catch leg”, the significant positive “Thai” term in the model indicated that Thai boxers used the technique highly significantly more often (χ21 = 25.12, p < 0.001). Non-significant interaction terms for “evade by stepping”, “leg block raised” and “skip away/back” also indicated that these techniques were far more common for Thai compared to UK fighters (as the terms indicate that the difference by nationality was similar to the significant diffe observed for the “catch erenc Open Access 181  T. MYERS ET AL. Table 4. Mean frequency of attacking techniques and associated quality indicators. Frequency Appropriate distance On balance Balance after Effect Attacking Techniques Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Clinching to attack 15.97 11.22 13.53 8.56 13.13 8.50 12.84 8.52 10.88 8.05 Teep (push kick) 16.75 10.18 12.22 10.91 14.50 10.16 12.81 9.89 9.50 7.67 Roundkick (body & neck) 26.03 11.64 21.56 13.01 22.38 13.88 19.16 14.38 17.22 11.87 Roundkick (leg) 11.59 7.37 9.34 5.46 9.22 5.85 8.16 5.38 6.06 4.26 Punches 22.28 12.99 18.13 10.93 19.69 11.60 17.25 9.93 11.00 5.96 Legal throw 2.69 4.67 1.94 2.66 1.97 2.75 1.47 2.06 1.88 2.56 Knees 14.09 10.96 13.66 9.21 12.38 10.89 11.59 10.64 9.63 7.83 leg” reference category). In contrast, UK fighters were highly significantly more likely to use “other” defensive techniques, as indicated by the large negative and highly significant “Thai × other” interaction term (testing the model term, χ21 = 86.83, p < 0.001). Figure 4 illustrates the mean frequency of defensive techniques used by Thai and UK fighters simulated from the model in Table 2. As can be seen, all techniques apart from “other” were considerably more common for Thai compared to UK fighters. Again, the significant fighter-level variance term indicated that there was clustering in the frequency of tech- niques by fighter. Quality Indicators Table 3 presents multilevel Poisson regression output mod- eling frequency of quality indicators on the basis of technique type, fighter nationality and the interaction between the two. As previously, Figure 5 uses the model estimates in Table 3 to simulate predicted mean frequencies of each quality indicator for Thai and UK fighters. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, all quality indicators were more common for Thai compared to UK fighters. For the reference category indicator “appropriate distance”, there was a highly significant difference between Thai and UK fighters (χ21 = 19.18, p < 0.001), with Thai fight- ers exhibiting the indicator far more often. The non-significant “Thai × delivered on balance” term suggested that Thai fighters also exhibited the “delivered on balance” indicator more often, with the difference similar to that for the “appropriate distance” reference category. As with the previous two models, there was also evidence of significant interaction between nationality and indicator type. In this case, positive significant terms for “Thai × effect” and “Thai × returned to balance” suggested that the difference between Thai and UK fighters was greater still for these indicators (compared to the difference observed for the “appropriate distance” reference category). Figure 5 illustrates the differences in mean frequency of quality indicators by fighter nationality. As shown, Thai fight- ers exhibited a greater number of each of the quality indicators when compared to UK fighters, though the difference was at its greatest for “effect” and “returned to a balanced state”. As pre- viously, the significant fighter-level variance term indicated that there was clustering in the frequency of quality indicators by fighter. Discussion The results point to the winners of Muay Thai bouts being proactive in using attacking techniques; overall fighters deliv- ered almost three times more attacking techniques than defen- sive techniques. Nevertheless, the observed and simulated data also highlight differences in the frequency of attacking and defensive techniques and in the associated qualitative variables measured alongside technique frequencies applied by the re- spective groups of fighters. Observed data suggests Thai fight- ers used more attacking and defensive techniques on average than their UK counterparts. Nonetheless, the Thai fighters actu- ally had a lower ratio of attacking techniques to defensive tech- niques suggesting, on average, they had a more balanced profile for these techniques. Both observed and simulated data pointed to differences in the number of specific techniques delivered, as well as differences in effectiveness and other qualitative vari- ables that may prove useful to coaches and athletes. The results also confirmed the predicted fighter level variance in attacking techniques, defensive techniques and in the quality indicators examined, revealing individual as well as group based differ- ences in the patterns of techniques employed. These individual variances supported the choice of multilevel analysis, high- lighting the need to consider the possibility of modeling differ- ences at both group and individual level when evaluating per- formance analysis. Attacking Techniques Kicking techniques were the most frequently employed form of attack, with round kicks to the body and neck being the most common kick used by fighters across groups. This supports previous findings that also found roundkicks to the body and legs the most frequently applied techniques by Muay Thai fighters (Michielon et al., 2008). This is perhaps not that sur- prising given the observed data in the present study suggests 66.15% of the roundkicks delivered were effective. Certainly the power of roundkicks to the body has been confirmed em- pirically. In a study on the kinetic and kinematic characteristics of Muay Thai roundkicks delivered at different heights, mid- dle-level kicks were found to generate the greatest peak force and impulse (Sidthilaw, 1997). Along with the fact that effec- tive strikes are an important factor in scoring bouts (Board of Boxing Sport, 2002), these particular kicking techniques can also be visually impressive and easily seen by judges (Myers, Nevill & Al-Nakeeb, 2010) further supporting their wide use by fighters. Nevertheless, there were differences in the frequency of their application across groups. Thai fighters employed sig- nificantly more roundkicks to the body and neck than their UK peers. Simulation confirmed these observed differences, pre- Open Access 182  T. MYERS ET AL. dicting almost twice the mean frequency for the Thai fighters. The more frequent use of this technique by this group may be explained by the Thai judges generally considering body kicks to be better scoring techniques than either punches or round kicks to the legs, at least given similar levels of physical effect (Myers, 2007). In view of their potential for scoring, and gen- eral effectiveness, combined with the recent adoption of Thai scoring across the UK, the republic of Ireland and in some states in North America, roundkicks to the body seem appropri- ate technique for coaches and athletes to focus upon in training. Punching attacks were the second most frequently used at- tacking technique across groups, representing 20.4% of all at- tacks used, yet the least effective pro rata with only 49.37% of the punches thrown having an effect on an opponent. The pat- tern of punches was similar to that observed in international boxing. The most common punching technique across groups was the straight punch, followed by hook punches and lastly the uppercut. El-Ashker (2011) also found straight punches to be the most frequently used punch in boxing, arguing that they are the most efficient. Certainly, straight punches appear to be quicker to reach their intended target than other punches (Piorkowski, Lees, & Barton, 2011). While the observed data suggests UK fighters tended to use more punching techniques overall than their Thai counterparts, this difference was not significant. Frequency data simulated from the model also points to marginally higher mean frequencies for UK fighters. The slightly greater use of punching in the UK group possibly reflects this groups more frequent exposure to international boxing than to Muay Thai in their formative years. That said, the Thai fighters in the study would also have been very famil- iar with international boxing techniques, with part of their fight preparation often including international boxing sparring (De Cesaris, 1999; Thienvibul, 1977). However, in Thailand pun- ches have a lower potential for scoring when compared with kicks or knees unless they are observed to be very effective (Myers, 2007). As such, the Thai fighters may have used re- duced punching volume, focusing instead upon punching effect. Given their speed, efficient use and the nature of scoring in Muay Thai, it appears sensible to suggest coaches should en- courage fighters to focus on power rather than just volume of punches delivered. In Muay Thai, the use of kneeing techniques is considered important by a number of authors (Delp, 2005; Ruangsa, 1972; Saengsawang, 1979). The execution of strong knees has the potential not only to score well, but also to show considerable effect. In the present study fighters across both groups delivered a higher number of effective strikes with their knees (68.35%) than with any other striking technique in their arsenal. So it was surprising that knee strikes were the least frequently used of all striking techniques across the groups as a whole. This was at odds with the findings of a previous study that found, propor- tionally, national level fighters in previous studies have tended to prefer knee strikes to other techniques (Michielon et al., 2008). The reason for high individual variance and lower than expected frequency of knees given their scoring potential, may be a consequence of the different somatotypes of fighters in- volved in the study. For instance, anecdotal evidence points to knees often being favored by taller fighters, relative to weight, rather than shorter fighters. This remains speculative as in the present study fighters’ somatotypes were not explicitly re- corded. Somatotype should be considered in any future studies, as encouraging the use of techniques unsuited to a particular body type is counterproductive. Nonetheless, the Thai fighters did use significantly more knees than UK fighters. Simulation from our model points to Thai fighters using knees more fre- quently than they did punches, roundkicks to the legs, throws, or clinching to attack an opponent. Considering the potential effect of well-delivered knees, it would be useful for coaches to prioritize the use of this technique where suitable for a particu- lar athlete. The teep technique was the third most commonly used tech- nique across groups. This is unsurprising given the appropriate application of this technique can disturb an opponent’s timing and balance as they attempt to deliver attacking techniques, and even secure a knockout on occasion (Delp, 2005). Thienvibul (1977) even claimed the teep to be the most important kicking technique in Muay Thai, used to counter all other kicking tech- niques. However, in the present study only just over half of all the teeps recorded were effective, perhaps evidence of their use as a counter technique rather than a direct form of attack. Fur- thermore, there were clear differences in the use of teeps across the groups. The observed results show significant differences between groups, with Thai fighters using the technique far more frequently than UK fighters. Simulated data predicts this dif- ference to be largest across groups, with Thai fighters predicted to use three times the number of teeps UK fighters do. To be used effectively, teeps require good balance before and after delivery (Kanwongkham, 1987; Thienvibul, 1977). This may be one of the reasons for the different frequencies found be- tween the groups studied. Particularly given the significant differences in balance identified in the present study, with UK fighters having poorer balance than Thai fighters. Evidence from this study suggests coaches should encourage fighters to practice and employ teep techniques more frequently given their overall efficacy, but any teaching strategy implemented would need to focus on improved balance during their deploy- ment. The most effective, but least used technique across groups were legal throwing techniques. 69.89% of throws used were effective but their use was very limited. Nevertheless, there was significant fighter level variance with some fighters employing the technique as frequently as 11 times in a fight, while many others did not use the technique at all. While there was no sig- nificant difference in the use of throws between Thai and UK fighters, simulation from the model suggests UK fighters used almost twice as many throws than Thai fighters. Observed dif- ferences may be the result of UK fighters capitalizing on any poor balance found in that group of fighters. UK fighters used the technique of clinching to attack more frequently, although this difference was not a statistically significant one. The simu- lation predicted that UK fighters are likely to apply this tech- nique 30.17% more often than Thai fighters. Thai fighters tended to use this technique far more defensively in the present study. However, whether the clinching was applied as an at- tacking or defensive action is possibly a moot point in terms of overall fighting strategy. Especially since clinching has a ten- dency to fluctuate between attack and defense within any single exchange. Defensive Techniques The results reported a significant difference in the defensive strategies used by each group. The most basic difference being that the Thai fighters defended themselves much more fre- Open Access 183  T. MYERS ET AL. quently than the UK group did. The evidence showed the Thai fighters used a number of defensive techniques far more fre- quently than their UK counterparts, including blocking using the raised leg, evading by stepping, and swaying away from their opponent’s kicks. Thai fighters also caught their oppo- nent’s kicking leg significantly more often than the UK fighters did. In contrast, UK fighters were more likely to use a range of other defensive techniques. These techniques included covering up using an international style boxing guard, blocking with the forearm, ducking under a technique and jumping back away from an attack. One of these techniques in particular, jumping back out and out of the range of an attacking technique, has been criticized. Krutsuwan (Myers, 2000) suggested that using this type of defense resulted in poor balance and offered a lim- ited the opportunity to counterattack. A fighter who jumps back out of range would have to readjust the weight distribution of their stance before being able to deliver a further technique. UK fighters might benefit by reducing their use of jumping back as a defense strategy, replacing it with a technique that would allow the possibility of immediate counterattack such as blocking or catching the kick. The Thai group used both of these techniques more frequently. Equally, UK fighters could be encouraged to employ another technique frequently used by Thai fighters, evading attacks by stepping back rather than by jumping away from techniques. Simulation using the multilevel Poisson regression model predicted that Thai fighters were almost eight times as likely to use stepping to avoid an attack, thus allowing the possibility of controlling their position with- out loss of balance and immediate countering. The second most frequently applied defense method was us- ing clinching to defend against an opponent’s attack. While UK fighters tended to prefer to use clinching frequently as an attack, they applied the technique far less in defense. Simulation from the multilevel model, predicted Thai fighters would use this technique twice as many times as UK fighters. Nevertheless, as mentioned previously, the use of clinching techniques for attack and defense can alternate within a single exchange, and so dif- ferences can be considered largely irrelevant in terms of fight tactics and strategy. Quality Indicators All quality indicators associated with the delivery of tech- niques were more common for Thai fighters when compared with UK fighters. In what is arguably the most important vari- able, the “effect of technique”, there was a highly significant difference between Thai and UK fighters. The number of effec- tive techniques landed by a fighter determines how a fight is scored in Muay Thai (Board of Boxing Sport, 2002). Effective techniques are considered so important in Muay Thai, that they can even cancel out all the less effective techniques landed in a round. There were also significant differences in fighters deliv- ering techniques on balance and returning to balance following delivery. Simulation using multilevel Poisson regression model produced for quality indicators predicted Thai fighters would deliver over twice as many effective techniques, and return to a balanced stance following the delivery of a technique more than twice as many times as UK fighters. The model also predicted Thai’s would deliver 70% more techniques at an appropriate distance, and 77% more techniques on balance than their UK peers. Myers (2007) and De Cesaris (1999) have highlighted the importance of balance in Muay Thai. When fighters are judged using the Thai judging system, if a fighter loses their balance following the delivery of a technique, it is unlikely to score as highly as when balance is maintained (Myers, Nevill, & Al-Nakeeb, 2010). To be successful in exploiting openings in an opponent’s defenses, a fighter needs to maintain close pro- ximity to their opponent while maintaining a balanced stance, suggesting that balance and appropriate distancing are essential prerequisites for taking advantage of any openings. Overall, the differences found between the competitors in the multilevel analysis and subsequent simulation highlights a se- ries of important differences between the groups analysed. The overall frequency of attacks and defenses used, and more im- portantly the very large differences in terms of the qualitative variables associated with those techniques, points to the Thai fighters analysed in this study being superior Muay Thai ath- letes in comparison to their UK counterparts. Nonetheless, some of the differences in frequency may be attributable to differences in the weight classifications of the fighters analysed. The Thai fighters analysed competed in the 50 kg to 63.5 kg weight classes, whereas the UK fighters competed in the heav- ier 57 kg to 71 kg classes. Alternative Explanations One possible argument for between group differences could be the mean difference in weight of fighters in each group. It is possible that the lighter Thai fighters delivered more techniques on average than their heavier UK counterparts; a lighter body- weight facilitating delivery. This might plausibly explain some of the within group variance found in both groups. Nevertheless, this would not easily explain the differences found in technique selection or quality indicators associated with those techniques. While there were mean differences between groups, the means were somewhat skewed by a single heavier UK fighter and a single very light Thai fighter. Many of the fighters analyzed competed in the same weight class. Perhaps a more credible alternative explanation of results may be the application of the different systems used to judge the fighters analysed in the present study. Until fairly recently the majority of Muay Thai competitions in the UK were judged in a similar way to international boxing, a concept familiar to western judges. Conversely in Thailand, Muay Thai is judged in a unique way with cultural nuisances making it substantially different to the judging system traditionally applied in the UK. There were a number of marked differences between the groups of fighters that could potentially be attributed to the judging criteria applied. These include the frequency of particular tech- niques employed, and the qualitative aspects of techniques such as balance. For example, the more frequent use of the round- kick to the body by the Thai fighters could be explained by the Thai judges regarding this technique as superior to either punches or a roundkick to the legs, even given the same level of physical effect. Whether the differences shown are the result of the hypothe- sized superiority of Thai fighters or the judging systems em- ployed, could be resolved by analyzing the techniques of cur- rent UK fighters. Since 2008 an increasing number of Muay Thai fights in the UK have been judged using a system that is very similar to that used in Thailand (Myers, Nevill, & Nakeeb, 2010). As such, it would be interesting to examine the tech- niques used UK fighters judged exclusively with the post 2008 system, to determine the impact of this newly implemented Open Access 184  T. MYERS ET AL. system of judging on technique application. Limitations and Future Research One limitation of this study was in the use of pre-recorded footage, and the analysis might have benefitted from the accu- racy of purposely-recorded footage, and filmed perhaps from more than one angle. This would have allowed for more control alongside the possibility of more detailed variables to be ana- lysed. Using purposely-recorded footage would also have of- fered the possibility of using automatic analysis software that was incorporated with the actual recorded footage. The use of more sophisticated software that could be incorporated with the actual recorded footage, would lead to the possibility of more precise data collection. With the use of such software, it may be possible to time the delivery of techniques enabling their speed to be accurately determined. Furthermore, if overhead recor- dings were included as an information source for data collec- tion, then accurate positional information could also be gath- ered. This would lead to the possibility of determining if par- ticular techniques were successful when delivered with an op- ponent backed against the ropes or in the centre of the ring. A further improvement in software design would be in incorpo- rating automatic statistical analysis and graphic output as an integral part of the software programme. This would save an enormous amount of analysis time. Reducing analysis time would consequently allow a greater number of fights to be ana- lysed, thereby improving the breadth of any Muay Thai data- base developed. Conclusion and Practical Implications In conclusion, the results of the study suggest that there are differences in fighting style between Thai and UK fighters. The reasons for these differences are less clear but may plausibly be down to the particular emphasis in training or reflect jurisdic- tional differences in terms of rule interpretation application which the groups of fighters were regularly exposed to. Overall, Thai fighters used more attacking and defensive techniques than their UK counterparts. They also delivered a far greater number of effective techniques, more techniques at an appro- priate distance, a larger number of techniques on balance, and they were also balanced far more often following the execution of a particular technique. These findings suggest that the Thai fighters were superior in a number of key areas compared to the UK fighters examined. The results offer potentially useful practical advice and di- rection to coaches and athletes in terms of training and tech- nique selection for competition. The study suggests that UK fighters tend to focus on attacking techniques at the expense of defensive techniques. Thai fighters were shown to predomi- nantly focus on a good defense allowing them to avoid getting hurt and focus on exploiting an opponent’s weaknesses. This suggests that coaches and fighters would benefit from empha- sizing effective defensive techniques to a greater extent, par- ticularly leg blocks and the leg raise defense position. The findings presented here also highlight the potential benefit of coaches focusing on techniques that have a high scoring poten- tial in the eyes of judges. This is particularly pertinent when given the recent adoption of Thai scoring across the UK, the republic of Ireland and in specific North American states. Thai style scoring clearly emphasizes particular techniques, which include appropriately delivered yet strong roundkicks and knee techniques. Therefore, it would be useful for Muay Thai coaches to encourage their use. Given that Thai scoring criteria are currently more widely applied internationally, it also ap- pears that the application of punching techniques should be given consideration by coaches. It would be better for coaches to encourage fighters to use punches to create openings to fa- cilitate higher scoring techniques, or otherwise be delivered with good timing, full power and accuracy to show effect. The results strongly imply that in all techniques delivered, quality and not just volume should be emphasized. The findings also point to the need for athletes and coaches to focus on balance before, during and after technique delivery. Finally, the results of this study show that multilevel Poisson regression models can be usefully applied to notational analysis, and potentially offer a superior method of analysis when there are high levels of individual level variance. REFERENCES Bliese, P. D., & Hanges, P. J. (2004). Being both too liberal and too conservative: The perils of treating grouped data as though they are independent. Organizational Research M e thods, 7, 400-417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231a66d Blomqvist, M., Luhtanen, P., & Laakso, L. (1998) Validation of a nota- tional analysis system for badminton. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 35, 137-150. Board of Boxing Sport (2002). Standard Rules and regulations for Boxing Sport Competitions B.E. 2545. Bangkok: Office of Profes- sional Sports, Sports Authority of Thailand. Brown, A. (2011) The fight for it all. Seidman Business Review, 17, 22- 23. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/sbr/vol17/iss1/10 Brown, M. B., Lauder, M., & Dyson, R. (2011). Notational analysis of sprint kayaking: Differentiating between ability levels. International Journal of Perform a n ce Analysis in Sport, 11, 171-183. Casolino, E., Lupo, C., Cortis, C., Chiodo, S., Minganti, C., Capranica, L., & Tessitore, A. (2012). Technical and tactical analysis of youth taekwondo performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26, 1489. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318231a66d Csataljay, G., James, N., Hughes, M. D., & Dancs, H. (2012). Per- formance differences between winning and losing basketball teams during close, balanced and unbalanced quarters. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 7, 341-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.4100/jhse.2012.72.02 De Cesaris, M. (1999). Lezioni Di Muay Thai: Thai Boxing. Milano: De Vecchi Editore. Delp, C. (2005). Muay Thai Basics: Introductory Thai Boxing Tech- niques. California: Blue Snake Books. Eaves, S., & Broad, G. (2007). A comparative analysis of professional rugby league football playing patterns between Australia and the United Kingdom. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 7, 54-66. El-Ashker, S. (2011). Technical and tactical aspects that differentiate winning and losing performances in boxing. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 11, 356-364. Falco, C., Landeo, R., Menescardi, C., Bermejo, J. L., & Estevan, I. (2012). Match analysis in a University Taekwondo championship. Advances in Physical Education, 2, 28-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2012.21005 Häyrinen, M., Hoivala, T., & Blomqvist, M. (2004). Differences be- tween winning and losing teams in men’s European top-level vol- leyball. Proceedings of VI Conference Performance Analysis, 168- 177. Hughes, M., & Bartlett, R. (2008). What is performance analysis? In M. Hughes, & I. M. Franks (Eds.), The essentials of performance analy- sis: An introduction (pp. 8-20). London: Routledge. Open Access 185  T. MYERS ET AL. Open Access 186 Hughes, M. (2004). Notational analysis-a mathematical perspective. International Journal of Performance An alysis in Sport, 4, 97-139. Hughes, M., James, N., Hughes, M., Vuckovic, G., & Dancs, H. (2011). Performance analysis—The future. In: M. D. Hughes, H. Dancs, K. Nagyvaradi, T. Polgar, N. James, & G. Vuckovic (Eds.), Research methods and performance analysis (pp. 246-256). Szombathely: University of West Hungary, Institute of Sport Science. Hughes, M. D., & Franks, I. M. (2004). Notational analysis of sport. London: E. & F.N. Spon. Kanwongkham J. (1987) Muay Thai—Boxing. Bangkok: O.S. Printing House. Kenny, D. A., & Judd, C. M. (1986). Consequences of violating the in- dependence assumption in analysis of variance. Psychological Bulle- tin, 99, 422-431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.3.422 Kwok, H. H. M. (2012). Discrepancies in fighting strategies between Taekwondo medalists and non-medalists. Journal of human Sport and Exercise, 7, 806-814. http://dx.doi.org/10.4100/jhse.2012.74.08 Lago-Peñas, C., Lago-Ballesteros, J., Dellal, A., & Gómez, M. (2010). Games-related statistics that discriminated winning, drawing and losing teams from the Spanish soccer league. Journal of Sports Sci- ence and Medicine, 9, 288-293. Lupo, C., Tessitore, A., Minganti, C., & Capranica, L. (2010). Nota- tional analysis of elite and sub-elite water polo matches. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24, 223-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c27d36 Michielon, G., Scurati, R., Longo, S., & Invernizzi, P. L. (2008). Tech- nical and tactical differences in regional and national level Thai box- ers. Book of abstracts of the 13th Annual Congress of European Col- lege of Sport Science (ECSS), Tenutosi a Estoril nel. Myers, T. D. (2000) An Interview with Master Chokechaichana Krutsuwan (Pimu). United Kingdom Muay Thai Magazine, 20-22. Myers, T. D. (2007) Cultural differences in judging Muay Thai. Annual Conference of the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences Abstracts. Journal of Spo rts Sciences, 25, 235-369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640410600958410 Myers, T. D., & Balmer, N. J. (2012). The impact of crowd noise on officiating in Muay Thai: Achieving external validity in an experi- mental setting. Frontiers in Ps ychology, 3, 1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00346 Myers, T. D., Balmer, N. J., Nevill, A. M., & Al-Nakeeb, Y. (2006). Evidence of nationalistic bias in Muaythai. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 21-27. Myers, T. D., Nevill, A. M., & Al-Nakeeb, Y. (2010). An examination of judging consistency in a combat sport. Journal Quantitative Analy- sis of Sports, 6, 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.2202/1559-0410.1178 Myers, T. D., Nevill, A. M. & Al-Nakeeb, Y. (2012). The influence of crowd noise upon judging decisions in Muay Thai. Advances in Physical Education, 2, 148-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2012.24026 Nevill, A. M., Atkinson, G., Hughes, M. D., & Cooper, S. M. (2002). Statistical methods for analysing discrete and categorical data re- corded in performance analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20, 829- 844. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026404102320675666 O’Donoghue, P. (2010). Research methods for sports performance analysis. London: Routledge O’Donoghue, P., & Ingram, B. (2001). A notational analysis of elite tennis strategy. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 107-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/026404101300036299 Ortega, E., Villarejo, D., & Palao, J. M. (2009). Differences in game statistics between winning and losing rugby teams in the Six Nations Tournament. Journal of Sports Science a n d M edicine, 8, 523-527. Piorkowski, B. A., Lees, A., & Barton, G. J. (2011). Single maximal versus combination punch kinematics. Sports Biomechanics, 10, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2010.547590 Rasbash, J., Steele, F., Browne, W. J., & Goldstein, H. (2012) A user’s guide to MLwiN, v2.26. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol. Ruangsa, Y. (1972) Textbook of Muay Thai. Thonburi: Charernkij Printing. Saengsawang, P. (1979). The development of Muay Thai. M.A. Thesis, Thailand: Chulalongthorn University. Thienvibul, C. (1977). Muay Thai. Bangkok: Suksasamphan Printing. Thomson, E., Lamb, K., & Nicholas, C. (2012). The development of a reliable amateur boxing performance analysis template. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31, 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.738922 World Muaythai Council (1995) Constitution, by-laws, rules and regu- lations. Bangkok: WMTC. Yuvanont, P., Buristrakul, P., & Kittimetheekul, N. (2010). Audience satisfaction management of Thai Boxing in Thailand: A case study of Lumpini and Ratchadamnern Stadiums. Featured Research in Sport Entertainment and Venues Tomorrow. Columbia, SC, 50.

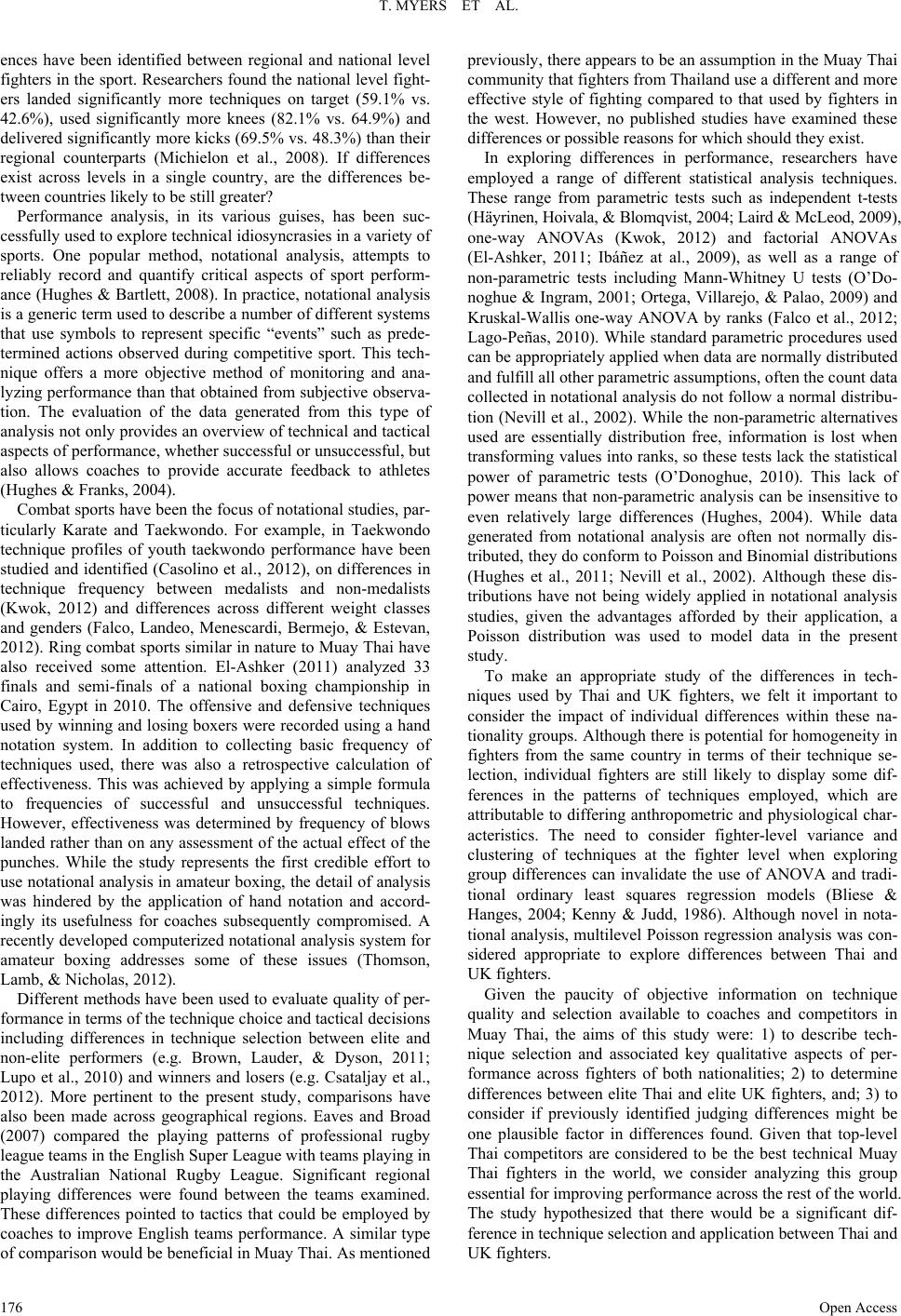

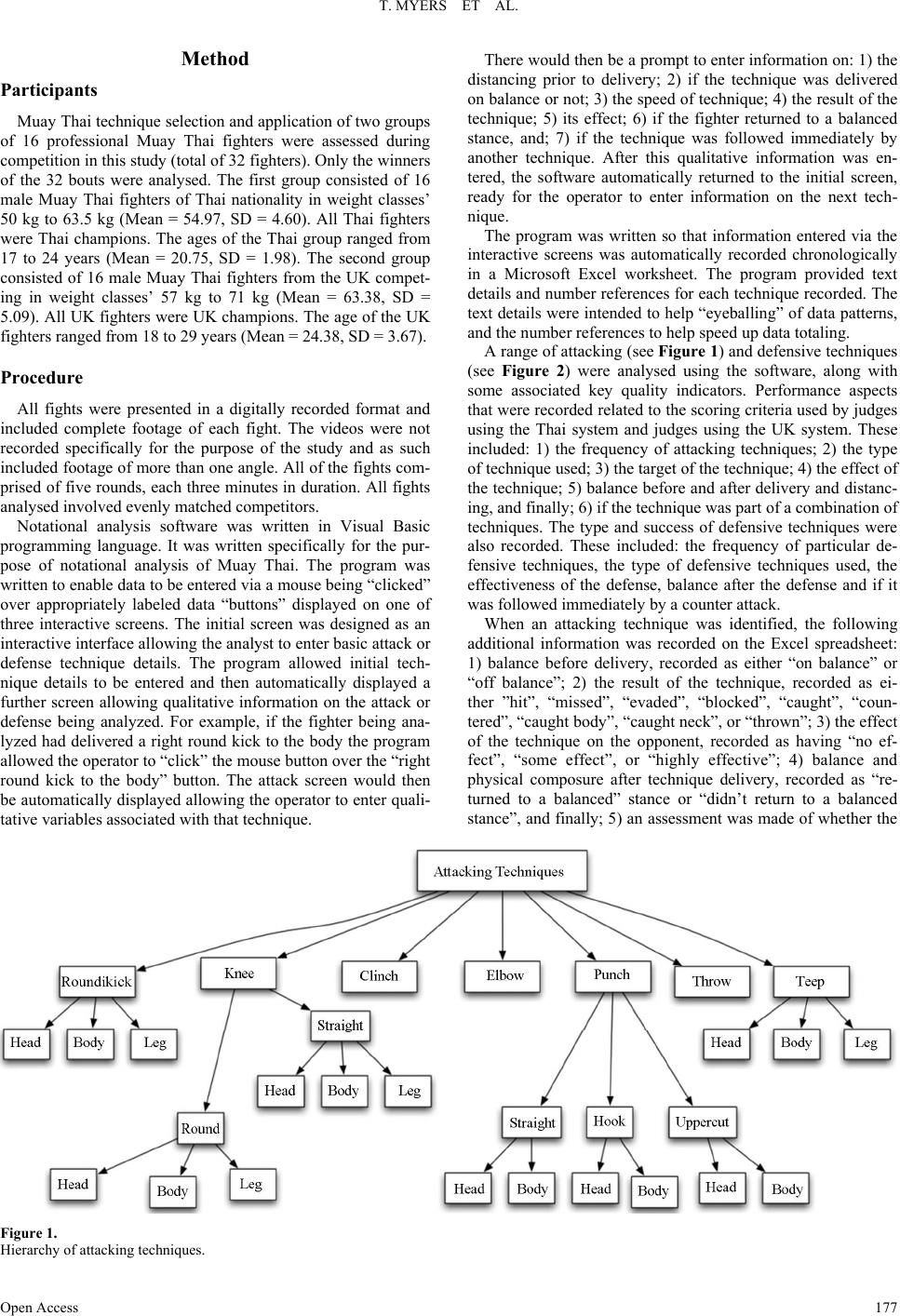

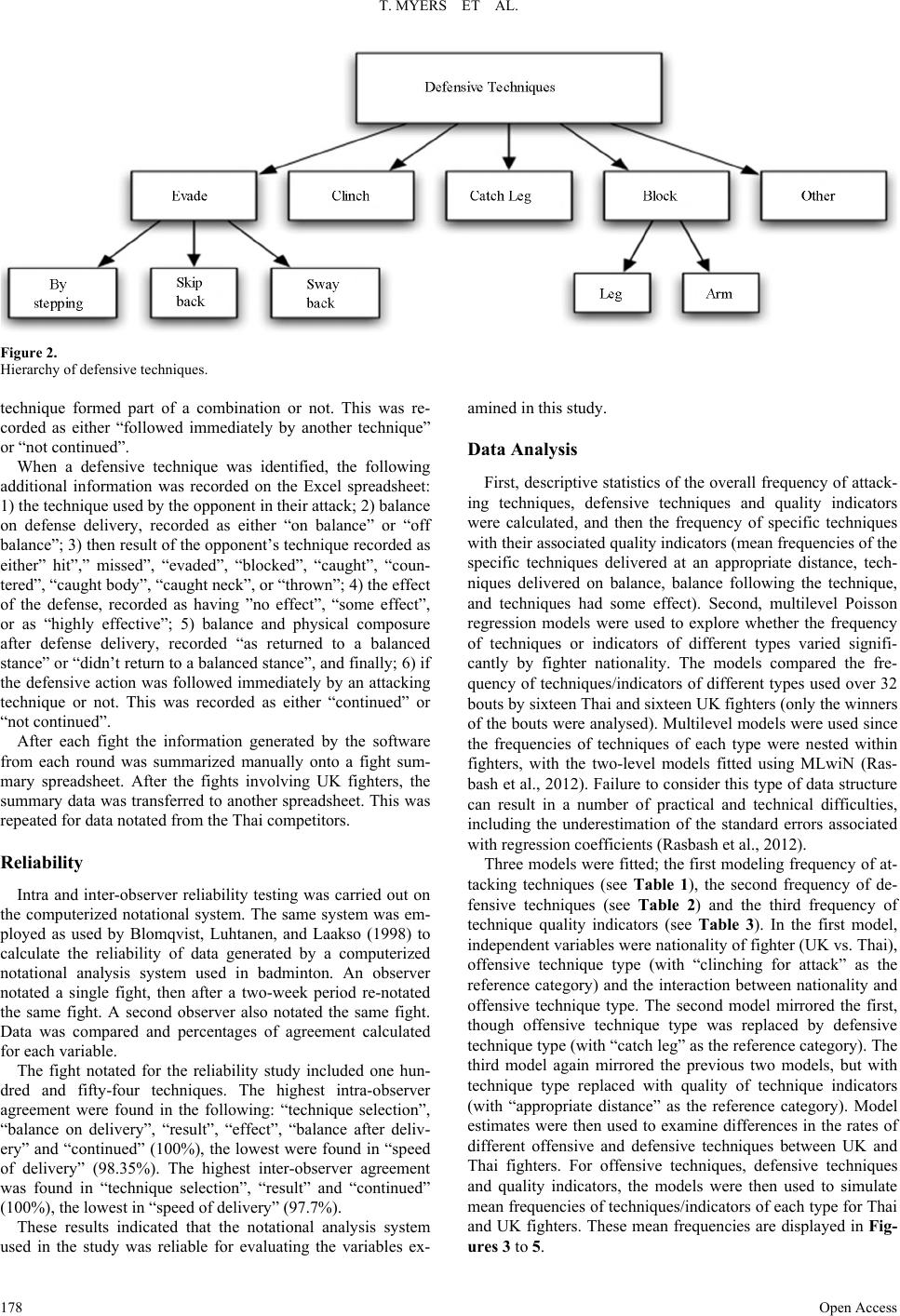

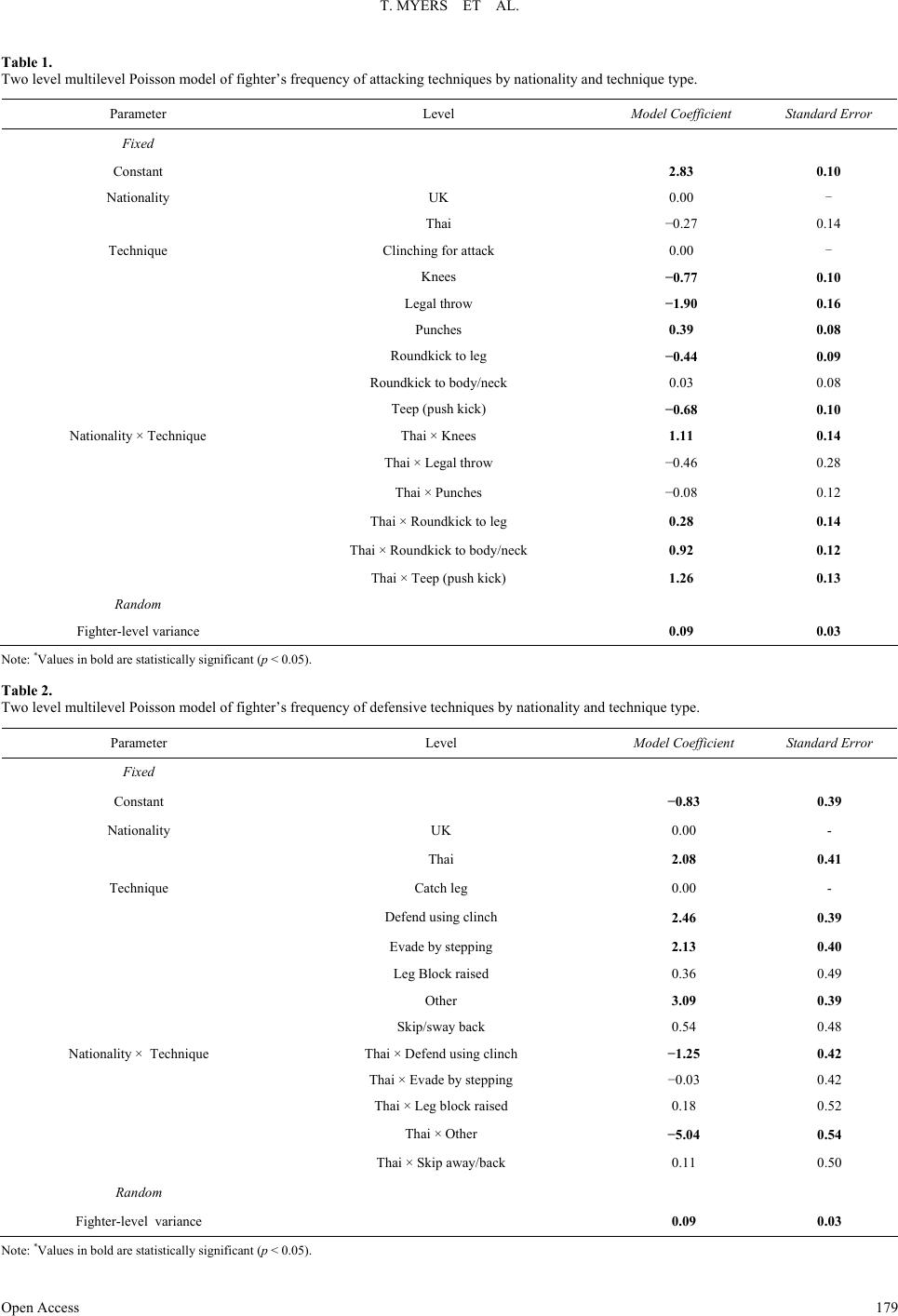

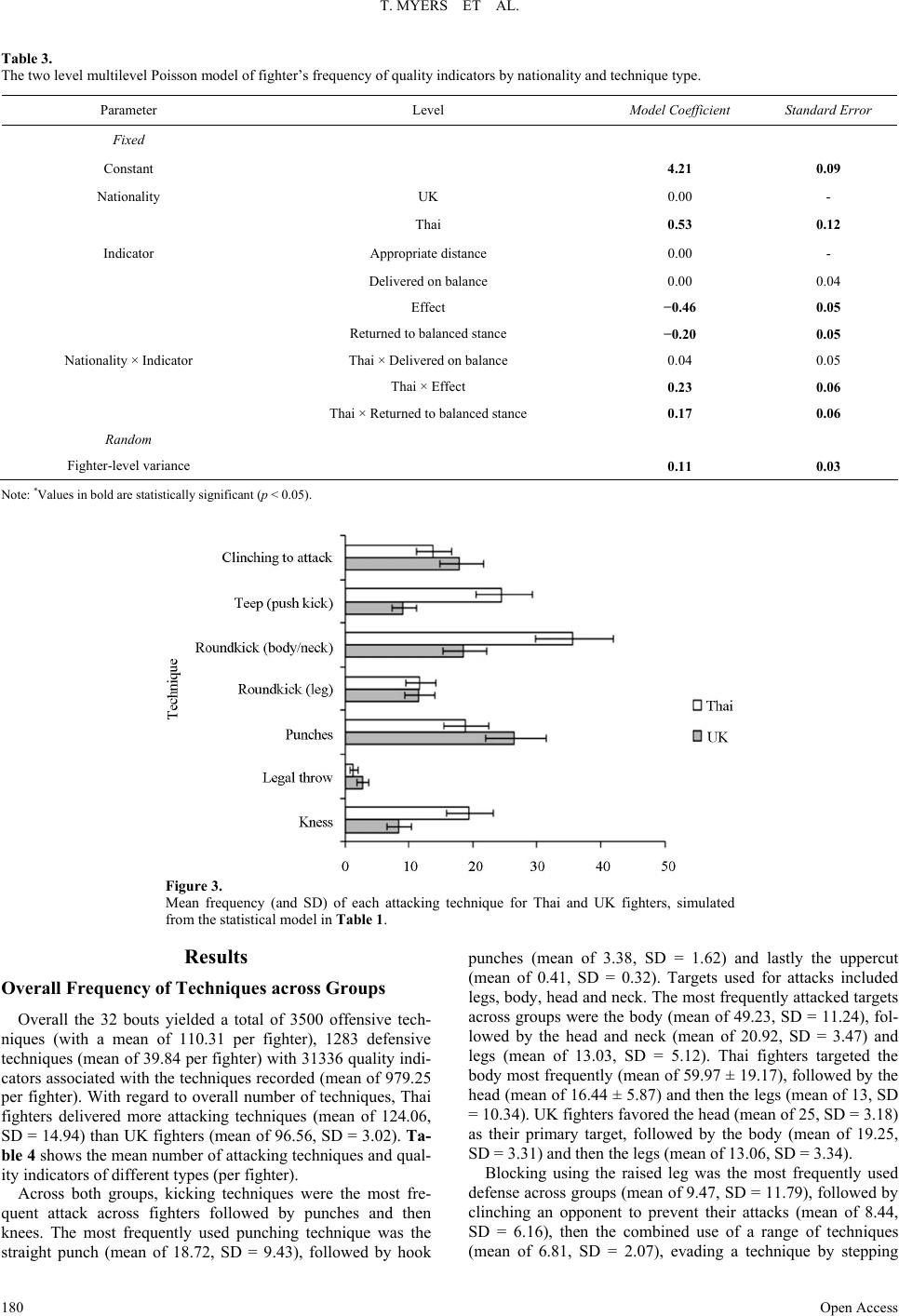

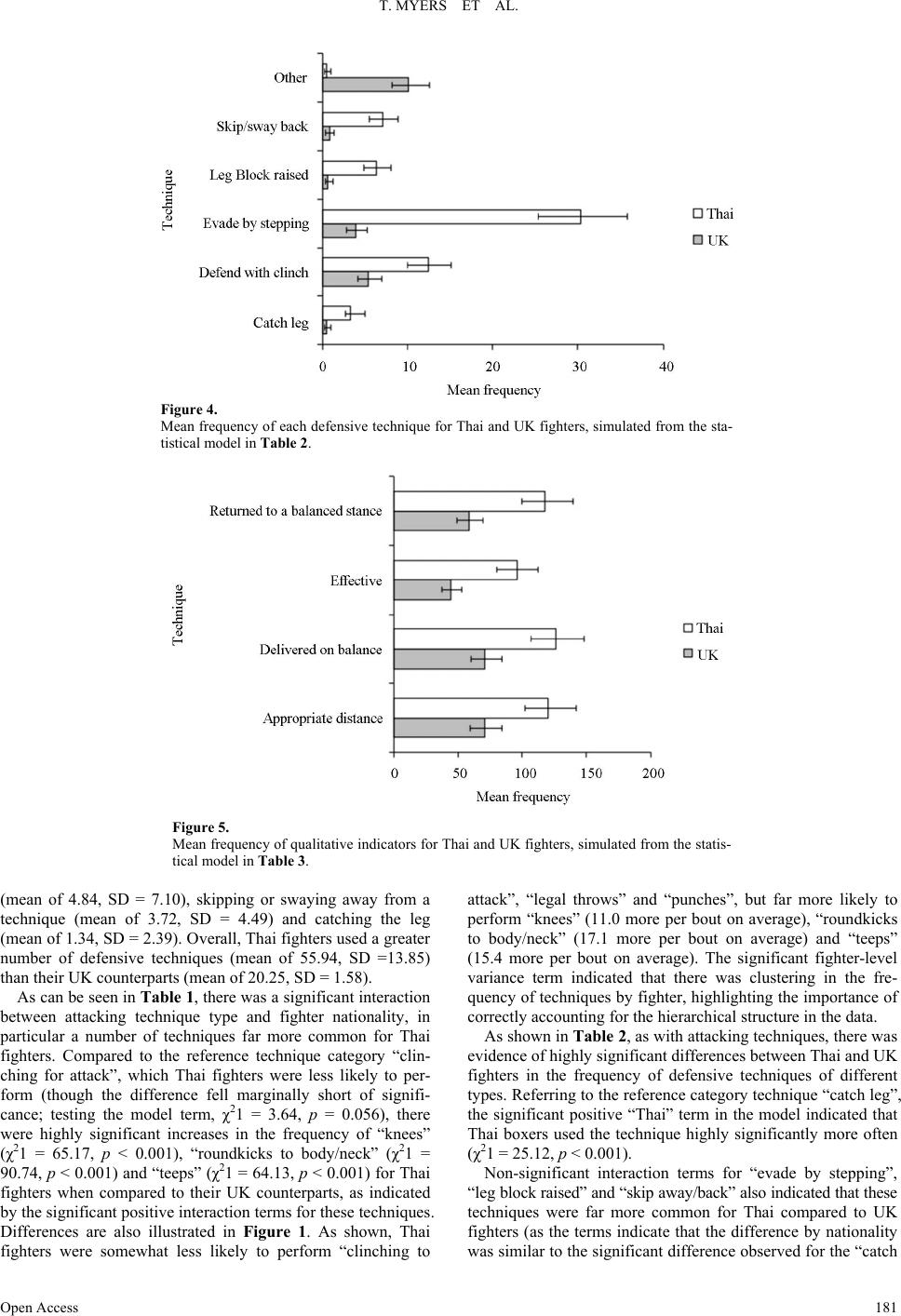

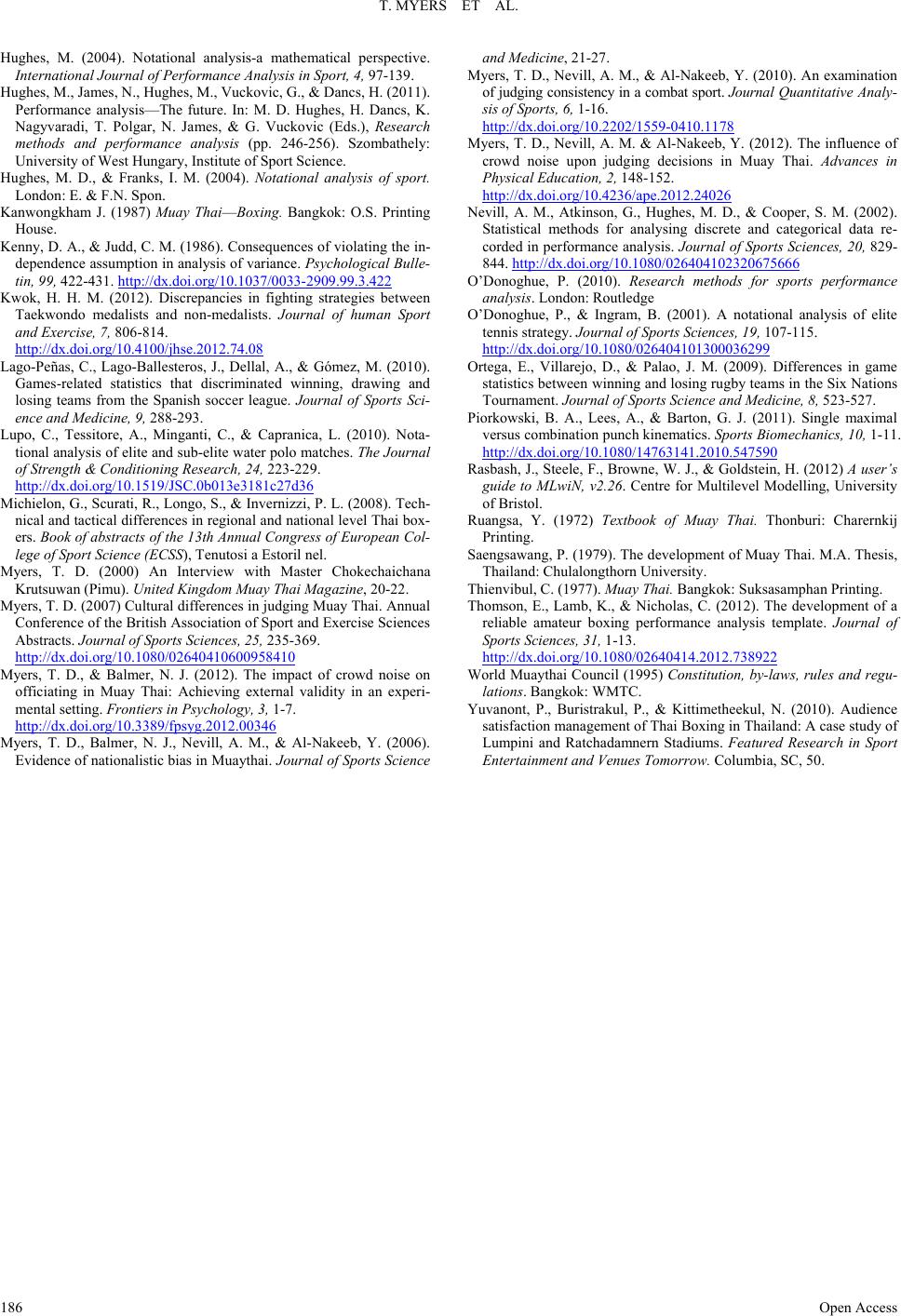

|