Open Journal of Nursing, 2013, 3, 485-492 OJN http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.37066 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojn/) OPEN ACCESS Perception gaps for recognition behavior betw e e n s taff nurses and their managers Chiharu Miyata1, Hidenori Arai1, Sawako Suga2 1Department of Hu m an Health Sciences, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan 2Department of N u rsing, Kansai University of Nursing and Health Sciences, Hyogo, Japan Email: miyata.chiharu.45v@st.kyoto-u.ac.jp Received 16 July 2013; revised 10 September 2013; accepted 2 October 2013 Copyright © 2013 Chiharu Miyata et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Nurse managers play a critical role in improving the work environment. Important leadership characteris- tics for nurse managers include visibility, accessibility, communication, recognition, and support. The nurse manager’s recognition behaviors strongly influence the job satisfaction of staff nurses. In our previous study, we investigated how staff nurses perceived the nurse manager’s recognition behaviors and revealed that there was a divergence in practical approaches to these behaviors between the nurse manager and the staff. We assume that one factor causing this diver- gence could be perception gaps between the nurse manager and the staff. The aim of this study, there- fore, was to uncover what types of perception gaps exist between the nurse manager and staff nurses and whether the background of staff nurses, such as years of experience or academic background, could affect the staff nurses’ perceptions. This quantitative, cross- sectional study invo lved 10 hospitals in Ja pan. A total of 1425 nurses completed the questionnaire. The re- sults showed that staff nurses considered “Respect job schedule preferences” to be the most important of the recognition behaviors. In contrast, nurse manag- ers gave “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurses to discuss patient care and unit management” the highest score for importance. Four factors (marriage status, age, years of clinical experience, and training background) affected the professional awareness of recognition behaviors. Our results suggest that nurse managers need to consider these factors when they conduct recognition behaviors. Keywords: Recognition Behavior; Nurse Manager; Staff Nurses 1. INTRODUCTION In the face of the current shortage of nurses, it is urgent to procure sufficient human resources by training nurses and preventing them from leaving the profession. The im- portance of improving staff motivation and work envir- onments and thereby enhancing job satisfaction as a mean s of preventing turnover and career change has recently been highlighted. One of the factors influencing work environ- ment and job satisfaction is the nurse manager’s manage- ment ability; in particular, the importance of recognition behavior, which is defined as assessing nurses’ perfor- mances and accomplishments in a concrete manner, has been reported [1]. Studies on nurse managers’ recognition behaviors identified work-related stress, commitment, au- tonomy, communication with superiors and colleagues, and recognition behavior as factors related to improved job satisfaction among nurses. Moreover, the recognition beha- vior of nurse managers was defined as their explanations of nurses’ performance and ability evaluations, which were presented in a 38-item scale for recognition behavior by nurse managers [2]. Goode & Blegen [3] conducted a survey on the perceptions of staff nurses, focusing on nurse managers’ recognition behavior. The researchers reported that performance recognition behaviors, consisting of 27 items, and achievement recognition behaviors, consisting of eight items, improved job satisfaction and prevented nurses from leaving their profession. In response to the study by Blegen [2], Ozaki [4] trans- lated the scale into Japanese and modified it to correspond to nursing staff scenarios in Japan. A factor analysis show- ed that five factors (reporting/announcing results, super- vising and supporting staff nurses, assigning jobs with responsibility, reporting evaluations from patients, and res- pect for desired working hours) correlated with job sa- tisfaction. In our previous study, we investigated how nursing staff perceived the nurse manager’s recognition behaviors and revealed that there was a distinction between the nurse managers’ and the staff ’s practical approaches to these be- haviors. We assume that one factor causing this distinction  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 486 could be possible perception gaps between the nurse ma- nager and the staff. We describe the development of a research-based management intervention to provide recog- nition and the implementation of the intervention by nurse managers. The aim of this study was to uncover what types of perception gaps exist and which factors, such as years of experience and academic background, could affect these perception gaps. 2. METHODS 2.1. Participants The study was conducted in 10 hospitals with 100 beds or more in the Kanto, Kansai, and Kyushu regions of Japan. Following the agreement of the involved organi- zations, a meeting was held so that the researchers could explain the project and procedures to all of the unit nurse managers. Individuals were informed that their answers would be treated anonymously and con- fidentially. 2.2. Data Collection We used a descriptive, cross-sectional design. The in- strument used for data collection was questionnaire about recognition behavior developed by Blegan [2]. This scale was translated by Ozaki [4] and converted to a revised 35-item Japanese scale. The questionnaires were divided into two parts. Part One consisted of the background information of responders, and Part Two contained 35-items for determining recognition beha- vior. The following demographic data were collected: age, gender, marital status, overall work experience, position (nurse manager or staff), academic background (associates degree, diploma in nursing, junior college graduate, or university/graduate university), mental health, and physical health. The participants were asked to describe a variety of nurse manager recognition beha- viors using a four-point Likert-scale ranging from “fully agree” to “fully disagree”. 2.3. Ethical Consideration The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School and the Faculty of Medicine. Additionally, research permission was given by the chief nursing directors of all 10 hospitals. The questionnaires included the researchers’ contact details, and the collected information was provided voluntarily and kept anonymous. 2.4. Statistical Analysis All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 20.0J (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for Windows. The categorical data were described using frequencies and percentages. Recognition behavior was analyzed using principal factor analysis. The median values and inter- quartile range (IQR) were used to describe continuous data. The evaluations of the implementation of the three extracted factors were compared using the Mann- Whitney U-test. Demographic comparisons based on recognition behavior were analyzed using the Kruskal- Wallis test, and a multiple comparison was performed using a multiple analysis of variance (ANOVA) fol- lowed by the Bonferroni test. 3. RESULTS A total of 1425 nurses participated in this study. The participants were nurse managers (n = 117) and staff nurses (n = 1248). Ninety-four percent of the nurse managers were women, and 63% of them were married. The mean age was 47.7 years (range : 42.2 - 53.2 years). Regarding professional work experience, 14% had 10 - 19 years of nursing experience, and 86% had 4 - 19 years of experience. The nurse managers’ academic backgrounds included an associate’s degree (25%), a diploma in nursing (57%), junior college graduation (13%), and university or graduate school education (5%). Among the staff nurses, 94% were women, and 66% were single. The mean age was 33.8 years (range: 24.7 - 42.9 years). Regarding professional work ex- perience, 30% had 10 - 19 years of nursing experience, and 28% had 4 - 9 years (range: less than one year-42 years). Their academic backgrounds included an as- sociate’s degree (15%), a diploma in nursing (56%), junior college graduation (8%), and university or gra- duate school education (21%; Table 1). We compared the three items with the highest aver- ages among the 35 questions to determine the differences between nurse managers’ and staff nurses’ views of recognition behavior (Table 2). The staff nurses gave “Respect job schedule preferences” the highest score, indicating that they considered it the most important recognit i o n behavior. This was followed by “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurses to discuss patient care and unit management” and “Patient evaluations that compliment individual nurses on the unit are posted on the bulletin board.” For nurse managers, “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurses to discuss patient care and unit management” had the highest score, followed by “Patient evaluations that compliment individual nurses on the unit are posted on the bulletin board” and “The nurse manager evaluates the staff by their work”; therefore, the top two items were the same as those indicated by the staff nurses. The three items with the lowest average score were “Release time is given to spend a day with the supervisor  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 487 Table 1. Demographic characteristics of nurses (n = 1425). Nurse manager (n = 177) Staff nurse (n = 1248) Demographic variable n % n % Gender Male 11 6 81 6 Female 166 94 1167 94 Marital status Single 66 37 826 66 Married 111 63 422 34 Age range, years, mean (±SD) 47.7 (±5.5) 33.8 (±9.1) Under 30 0 0 516 44 30 - 39 14 8 319 27 40 - 49 94 53 260 22 Over 49 69 39 81 7 Overall work experience, years, mean (±SD) 25.1 (±5.6) 11.0 (±8.7) Under 3 0 0 288 23 4 - 9 0 0 346 28 10 - 19 24 14 373 30 Over 19 153 86 241 19 Academic background Associate degree 45 25 186 15 Diploma in nursing 100 57 703 56 Junior college graduate 23 13 101 8 University or graduate university 9 5 258 21 Table 2. Nurse managers’ behaviors that provide recognition for performance and achievement (the highest average). Staff nurses (n = 1248) Nurse managers’ behaviors Mean (SD) I Respect job schedule pr eferences 3.15 (0.65) II Nurse manager meets with the staff nursee to discuss patient care a nd uni t management. 3.15 (0.62) III Patient evaluations that compliment individual nurses on th e u nit are posted on the bulluten board. 3.08 (0.62) Nurse managers (n = 177) Nurse managers’ behaviors Mean (SD) I Nurs e manager meets with the staff nursee to discuss patient care and unit management. 3.34 (0.59) II Patient evaluations that compliment individual nurses on th e u nit are posted on the bulluten board. 3.33 (0.57) III The nurse manager evaluates the staff by their work. 3.29 (0.54) to experience management functions,” “Achievements are announced in the hospital newsletter,” and “Release time is given to work on special projects for the unit,” suggesting that they had a low lev el of importance to the staff as recognition behaviors (Table 3). For the nurse managers, the lowest three items were “Release time is given to work on special projects for the unit,” “Pre- ference for selection of hours is given to the nurse,” and “Helps with the staffs’ job when busy.” Using the responses to these 35 questions related to recognition behavior, we performed a factor analysis (main factor method: promax rotation) for nurse mana g er s  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 488 Table 3. Nurse manager’s behaviors that provide recognition for performance and achievement (the lowest average score). Staff nurses (n = 1248) Nurse managers’ behaviors Mean (SD) I Release time is given to spend a day with the supervisor to experi en ce ma nagement functions. 2.63 (0.69) II Achievements are announc ed in t he h osp it al n ews le tt er. 2.64 (0.71) III Release time is given to work on special projects for the unit. 2.67 (0.75) Nurse Managers (n = 177) Nurse managers’ behaviors Mean (SD) I Release time is given to work on special projects for the unit. 2.75 (0.66) II Preference for selection of hours is given to the nurse. 2.75 (0.64) III Helps with the staffs’ job when busy. 2.77 (0.71) and staff nurses. We also performed a factor analysis that excluded items that had many plural factors, taking a load of 0.4 as a reference. As a result, five items (“The nurse manager praises the staff individually,” “Release time is given to spend a day with the supervisor to ex- perience management functions,” “Senior nursing ma- nagement receives a letter from the nurse manager regarding the staff nurse’s performance,” “Private verbal feedback is given by the nurse manager,” “Using time to serve the staff”) were excluded from the 35 items due to low factor loadings (0.4 or less) in both the staff nurses’ and nurse managers’ responses. For the staff nurses, an additional six items (“The nurse manager brags about the performance of the unit staff nurse,” “The nurse manager encourages the staff nurse to develop expertise in one aspect of care,” “Peer review provides an opportunity for the staff nurse to share developed projects/materials,” “Release time is gi- ven to work on special projects for the unit,” “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurse to provide support and assistance towards professional and career goals,” “The nurse manager congratulates the nurse in front of peers”) were excluded, for a total of 11 excluded items. Eventually, we extracted 24 items, which were classified into three factors. Factor One consisted of eight items related to evaluation, such as “The achievements of nurses are posted on the bulletin board” and “Achieve- ments are announced in the hospital newsletter” and was classified as “Evaluation, presentation, and report.” Fac- tor Two consisted of nine items related to job schedule preferences, patient care, and participation in decision- making in wards, such as “Respect job schedule pre- ferences,” “Helps with the staffs’ job when busy,” “The nurse is given preference for t he selection of work ho urs” and was classified as “Individual value and transfer of responsibility.” Factor Three consisted of seven items related to participation in training and professional abi- lity activities, su ch as “Staff nurses are asked to represent the unit at hospital meetings” and “Staff nurses are selected as presenters for new employees” and was la- beled “Professional development.” For the nurse managers, an additional eight items (such as “Staff nurses are encouraged to participate in professional activities at the local and national level”) were excluded. We classified the 28 remaining items into three factors. Factor One included 14 items related to staff considerations, such as “For consistently working extra hours, a written letter is given to the staff nurse and a copy is placed in the personnel file” and “Respect job schedule preferences” and these items were categorized as “Individual consideration and development.” Factor Two consisted of nine items related to the publication of evaluations and reports to the nurse manager, such as “Nurses’ achievements are posted on the bulletin board” and “Achievements are announced in the hospital newsletter,” and these items were called “Notification and report of achievements.” Factor Three was composed of three items related to the nurse manager’s behavior in evaluating the staff, such as “The nurse manager con- gratulates the nurse in front of peers” and “The nurse manager brags about the performance of unit staff nurse,” and this factor was labeled “Expression of eva- luation.” The internal consistency of each factor in the factor analysis for both nurse managers and staff was 0.50, indicating the reliab ility of the questionn a ire (Table 4). We compared the median score of the lower item total score for factors with staff’s attributes. In Factor Three, married nurses obtained a significantly higher score than did single nurses, the 40-year age group obtained higher scores than the 20-year age group did, and those with 10 - 19 years clinical experience obtained higher scores than those with three years’ experience or less, in- dicating the importance of Factor Three as a recog- nition behavior. However, in terms of academic background, university  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 489 and college graduates obtained a significantly lower score compared with those with associate degrees and diplomas in nursing, indicating that Factor Three was not considered important in those areas (Table 5). Table 4. Resu lt of exploratory factor analysis on recognition behavior. Staff nurses (n = 1248) Factor Number of items Cronbach’s alpha Factor loadings I Evaluation presentation and report 8 0.869 0.577 - 0.83 II Individual value and transfer of respo n s ibility 9 0.847 0.48 - 818 III Professional development 7 0.752 0.532 - 0.816 Nurse managers (n = 177) Factor Number of items Cronbach’s alpha Factor loadings I Individual consideration and development 14 0.869 0.489 - 0.858 II Evaluation presentation and repor t 9 0.847 0.418 - 0.678 III Expression of evaluation 4 0.752 0.488 - 0.639 Table 5. Demographic comparison based on recognition behavior analyzed by an exploratory factor (Staff nurses). Factor One Factor Two Factor Three Median IQR p Median IQR p Median IQR p Gender Male 23 20 - 2527 25 - 2921 19 - 22 Female 24 21 - 240.763a) 27 25 - 290.992 21 19 - 22 0.876 Marital status Single 23 21 - 2427 25 - 2921 18 - 21 Married 23 21 - 250.293a) 27 25 - 300.152 21 19 - 23 0.001 Age range, years Under 30 24 21 - 2427 25 - 2721 18 - 21 30 - 39 23 20 - 2427 25 - 2721 19 - 22 40 - 49 24 21 - 2427 25 - 2721 19 - 22 Over 49 23 21 - 24 0.121 27 24 - 27 0.62 21 21 - 22 0.002 Overall work experience, years Under 4 23 21 - 2427 25 - 2921 18 - 21 4 - 9 24 20 - 2427 25 - 2921 18 - 22 10 - 19 23 21 - 2527 25 - 3021 19 - 23 Over 19 23 21 - 25 0.513 27 24 - 29 0.46 21 19 - 23 0.002 Academic background Associate degree 24 20 - 2527 25 - 3021 19 - 22 Diploma in nursing 24 21 - 2427 25 - 2921 19 - 22 Junior college graduate 23 21 - 2527 25 - 2921 18 - 21 University or graduate university 23 21 - 24 0.993 27 24 - 28 0.06 21 18 - 21 0.001 n = 1248, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 a)Mann-Whitney test. Kruskal-Wallis test and the mu ltiple c omparisons test were per formed b y a mult iple ana lysis of vari- ance.  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 490 4. DISCUSSION Compared with the average of the each lower item (35 questions) concerning recognition behavior for staff nurses, the highest scores were obtained for “respect job schedule preferences”. This is most likely because of the importance of a good work-life balance. Inadequate work scheduling and long working times have been identified as a major threat to employees’ health and well-being. Shift working has been found to cause fatigue, sleep disruptions, impaired concentration, irritability, and somatic symptoms, such as digestive problems [5,6]. However, studies have suggested that the effects of shift work can be reduced not only by adopting ap- propriate shift rotations [7] but also by increasing the predictability of work schedules [8] and choices over shift patterns [9]. Among the survey respondents, 66% were single; those respondents placed importance on having sufficient individual free time. Further, 71% were younger than 30 years old, at a point in life when they experience many life-changing events, such as marriage and giving birth. It is also possible that younger nurses experience more stress and fatigue be- cause they have greater family responsibilities than older nurses do [10]. In terms of less important items among the recognition behaviors, “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurses to discuss patient care and unit management” was selected by both staff nurses and nurse managers. According to previous research, an important predictor of a staff nurse’s job satisfaction is the p rofession al practice model [11-14]. Some characteristics of professional practice are autonomy and shared governance [15]. Nurse managers should not just listen to the thoughts and opinion s of staff nurses in a one-sided way; instead, they should convey the intentions of their own actions and let the staff nurses participate in decision-making [16]. This shows that nurse managers are also aware of the importance of this type of communication. Among the recognition behaviors, the item of which the staff nurses were the least aware was “Release time is given to spend a day with the supervisor to experience management functions”. This may be because the daily work demands of a nurse, such as the introduction of sophisticated medical devices and the need for increased care for the elderly, are becoming increasingly complex, and either the nurses have insufficient interest or knowl- edge of administrative matters or they believe that such matters are the responsibility of the nurse manager. In comparison, there was a tendency for nurse managers not to be aware of the item “Helps with the staff’s job when busy”. This result suggests that in Japan, staff nurses do not regard the nurse manager as an “administrator”, but rather as a staff member who performs nurse duties, as a previous study indicates [4]. Furthermore, most staff nurses recognized the nurse manager as another member of the nursing staff who performs nursing duties rather than someone in a “management position”, which sug- gests that the difference between the nurse manage- ment and staff roles may not be clear to staff nurses. Thus, a trend toward insufficient understanding of management was observed among this study’s res- pondents. A slight difference in the lower items among the fac- tors was observed from the results of the factor ana- lysis; however, a common awareness was noted for two factors, including items relating to consideration to each staff member, notification of achievements and reports. Two lower items (“The nurse manager congratulates the nurse in front of peers” and “The nurse manager brags about the performance of the unit staff nurse”) were excluded from the factor analysis for staff nurses. In contrast, these items were included as “Expression of evaluation” in the factor analysis for nurse managers. These exclusions occurred because staff nurses do not like to be praised in public. In addition, this exclusion may arise from the fact that Japanese people are con- servative, believe that “envy is th e companion of honor”, and prefer quieter, emotional approval to receiving ap- proval openly [17]. Furthermore, the lower items in Fac- tor Three for the staff (“Professional development”) were included in Factor One (“Consideration and development of individual”) for the nurse managers, which indicates their respect for each staff nurse. Higher scores in the 40-year age group and the group with 10 - 19 years clinical experience relative to the 20- year age group and tho se with three years’ experience or less, respectively, underline the importance of Factor Three as a recognition behavior. Nurses in mid-career were defined as those who had been in practice for 11 and 22 years and those between the ages of 31 and 50. Strong associations were found between retention and control over nursing practice for nurses in mid-career [18]. Thus, staff nurses aged 40 - 49 years have been trained as experts in their profession; they have a strong desire for career advancement as professionals and keen- ly wish to receive recognition. In the same way, for Factor Three, there was less awareness of recognition behavior among university and college graduates than among those with associate de- grees and diplomas in nursing. This occurred because the lower items are related to participation in hospital con- ferences, selection as preceptors, and participation in seminars, and graduates most likely desire more aca- demic career advancement [19], which is not included in these activities. This aspect of staff nurses’ professional development needs to be considered by including it in future training.  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 491 5. CONCLUSIONS A Our results indicate that nurse managers assign the maximum respect to such recognition behaviors as “Nurse manager meets with the staff nurses to discuss patient care and unit management” and “Patient eval- uations that compliment ind ividual nurses on the unit are posted on the bulletin board”; in this respect, staff members’ and nurse managers’ responses were con- cordant. However, staff nurses regarded “respect job schedule preferences” as the most important recognition behavior, indicating that there was different awareness of this behavior between staff and nurse managers. Our results also showed that marriage status, age, years of clinical experience, and training background influenced the awareness of recognition behavior as a “professional job”. We predict that the burnout of staff nurses, which can be caused by in creased nursing duties and by difficulties in interpersonal relationships, will increase in the future. We believe that recognition behaviors are an effective way to support nurses’ self-realization . 6. RECOMMENDATIONS A The results of this study indicate what types of re- cognition behaviors staff nurses expect from nurse ma- nagers and what staff nurses consider important. The results can also reflect the difference in awareness be- tween the nurse manager and staff nurses and suggest future directi o ns for the educat i on of nurse managers. A nurse holds a patient’s life in her hands. It is a professional job in which she or he must take care of the patient and show a high degree of flexibility with me- dical techniques and skills. For this professional job, it has been reported that praise from the superior is more effective than providing information or emotional sup- port for preventing burnout [20]. This fact also indicates that it is desirable for the nurse manager to be aware of the importance of giving her staff and their work praise and approval. Moreover, it has been shown that the leadership of the nurse manager influences staff nurses’ job satisfaction. It has been reported that staff nurses do not merely want the nurse manager to manage the ward; rather, they want her or him to play a functional role within the overall infrastructure in which they look to her or him for leadership to ensure their status as inde- pendent professionals [21]. In the future, transforma- tional leadership will no doubt be required, including such recognition behavior such as sensitivity toward the staff and providing stimulation and motivation. 7. LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY A Many interlinked factors, such as an individual sense of values, regional characteristics, and job locations, may be important to this study, but they have not been discussed. In addition, regarding the survey items used, changes in the environment surrounding treatment, and changes in nurses’ working co nditions and training, need to be considered in the futu re. 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank all of the nurses who took time from their busy schedules to participate in this study. REFERENCES [1] Muya, M., Katsuyama, K. and Aoyama, H. (2009) An analysis of factors influencing job satisfaction of mid- career nurses at acute care hospitals. The Journal of the JANAP, 13, 14-23. [2] Blegen, M.A. (1992) Recognizing staff nurse job per- formance and achievements. Research in Nursing & Health, 15, 57-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770150109 [3] Blegen, M.A. (1993) Nurses’ job satisfaction: A meta- analysis of related variables. Nursing Research (New York), 42, 36. [4] Ozaki, F. (2003) Influence of head nurse recognition behavior to staff nurses’ job satisfaction. Niigata Medical Journal, 117, 155-161. [5] Spurgeon, A. and Cooper, C.L. (1997) Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: A review of the current position. Occupational and environmental medicine (London, England), 54, 367. [6] Scott, A. (2000) Shiftwork and health. Occupational and Environmental M e d ic i n e , 27, 1057-1077. [7] Harrington, J.M. (2001) Health effects of shift work and extended hours of work. Occupational and Environ- mental Medicine (London, England), 58, 68. [8] Costa, G., Lievore, F., Casaletti, G., et al. (1989) Circa- dian characteristics influencing interindividual differ- ences in tolerance and adjustment to shiftwork. Ergo- nomics, 32, 373-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00140138908966104 [9] Barton, J., Smith, L., Totterdell, P., et al. (1993) Does individual choice determine shift system acceptability? Ergonomics, 36, 93-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00140139308967859 [10] Peters, V.P.J.M., Rijk, A.E. and Boumans, N.P.G. (2009) Nurses’ satisfaction with shiftwork and associations with work, home and health characteristics: A survey in the Netherlands. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 2689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05123.x [11] George, V., Burke, L., Rodgers, B., et al. (2002) Devel- oping staff nurse shared leadership behavior in profes- sional nursing practice. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 26, 44-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006216-200204000-00008 [12] Newhouse, R.P. and Mills, M.E.C. (2002) Enhancing a professional environment in the organized delivery sys-  C. Miyata et al. / Open Journal of Nursing 3 (2013) 485-492 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 492 tem: Lessons in building trust for the nurse administrator. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 26, 67-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006216-200204000-00010 [13] Mark, B.A., Salyer, P.J. and Wan, T. (2003) Professional nursing practice: Impact on organizational and patient outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 33, 224- 234. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200304000-00008 [14] Hall, L.M. and Doran, D. (2004) Nurse staffing, care delivery model and patient care quality. Journal of Nurs- ing Care Quality, 19, 27-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001786-200401000-00007 [15] Havens, D. and Aiken L.H. (1999) Shaping systems to promote desired outcomes: The magnet hospital. Journal of Nursing Administration, 29, 14-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005110-199902000-00006 [16] Tsukamoto, N., Yuki, T., Funaki, Y., et al. (2009) The influence of the head nurse from the viewpoint of the or- ganizational climate on burnout among staff nurses. Jour- nal of Japanese Society of Nursing Research, 32, 105- 112. [17] Ohta, H. (2011) Shounin to motivation [Recognition and Motivation]. Dobunkann, Tokyo. [18] Shindul-Rothschild, J. (1995) Life-cycle influences on staff nurse career expectations. Nursing Management, 26, 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006247-199506000-00009 [19] Hirai, S., Ebi, M., Yamada, S., et al. (2002) The nurses’ needs to study at graduate schools. Bull. Aichi Pre. Coll. Nurse. Health, 8, 33-40. [20] Ida, M. and Fukuda, H. (2004) Impact of workplace sup- port for nurses on the burn-out. The Journal of the Psy- chological Institute, Rissho University, 2, 77-88. [21] Takatani, Y. (2007) Transformational leadership by nurse managers and job satisfaction: As seen in relation to years of nursing experience and basic nursing education. UH CNAS, RINCPC Bulle ti n, 14, 93-105.

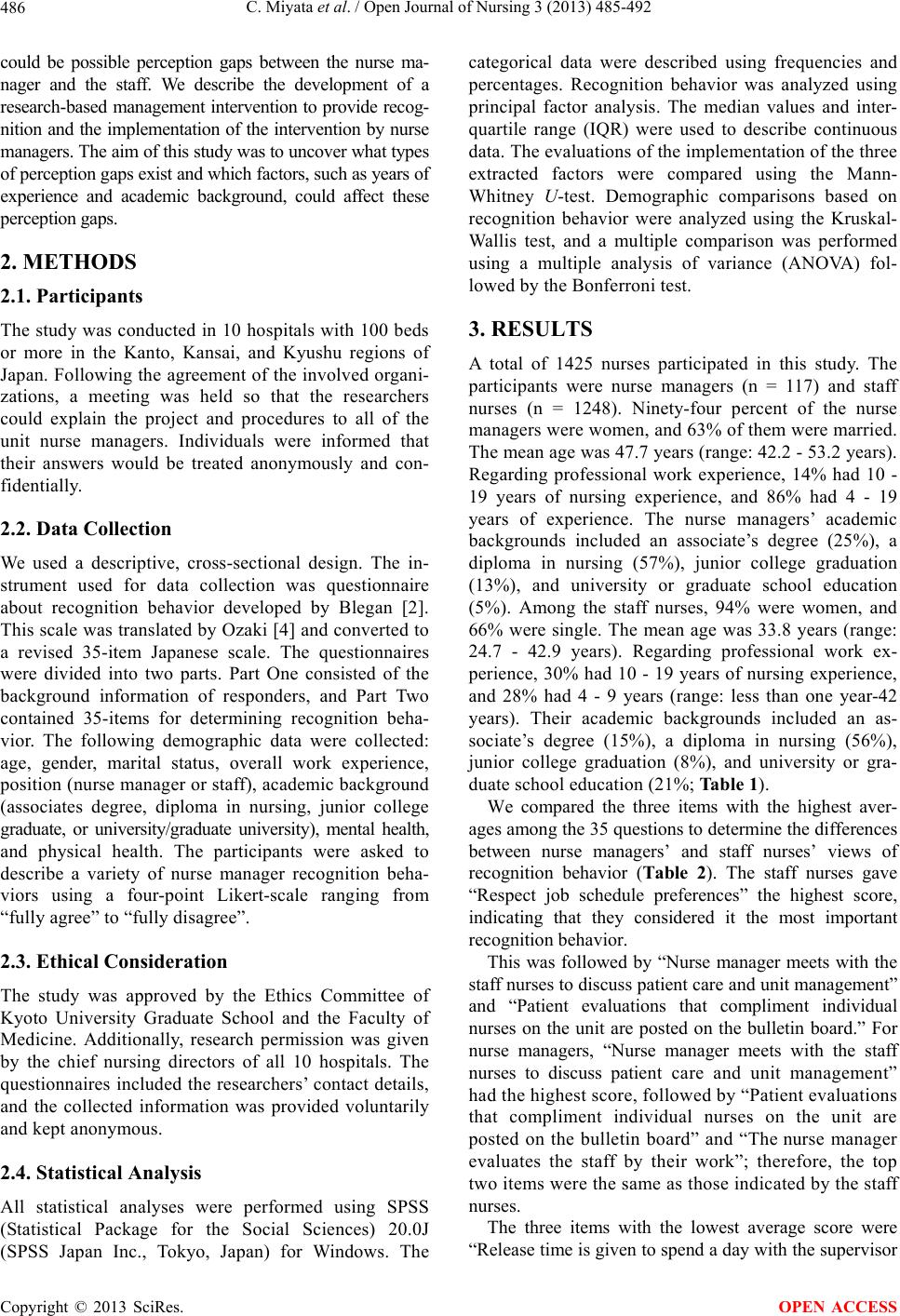

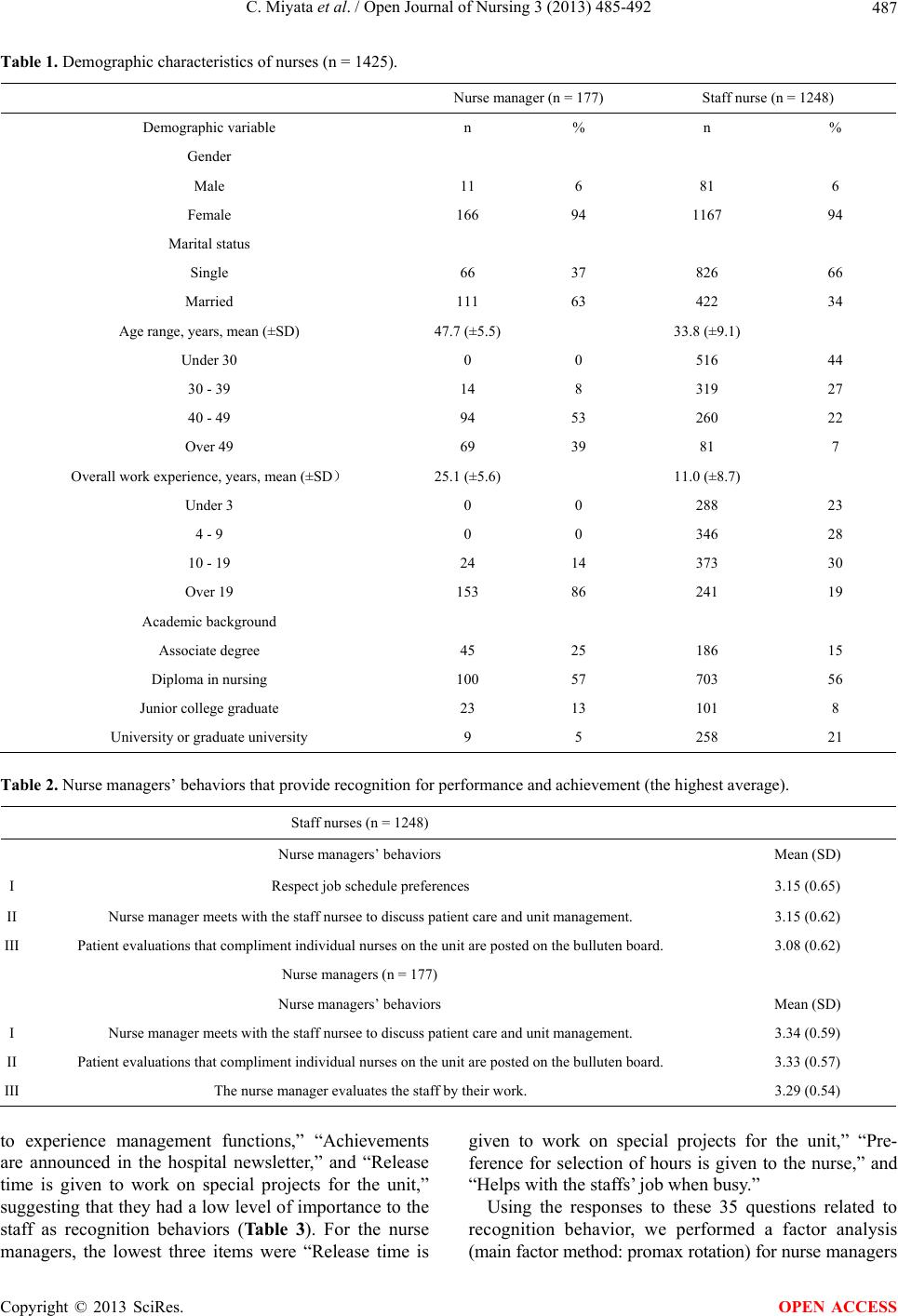

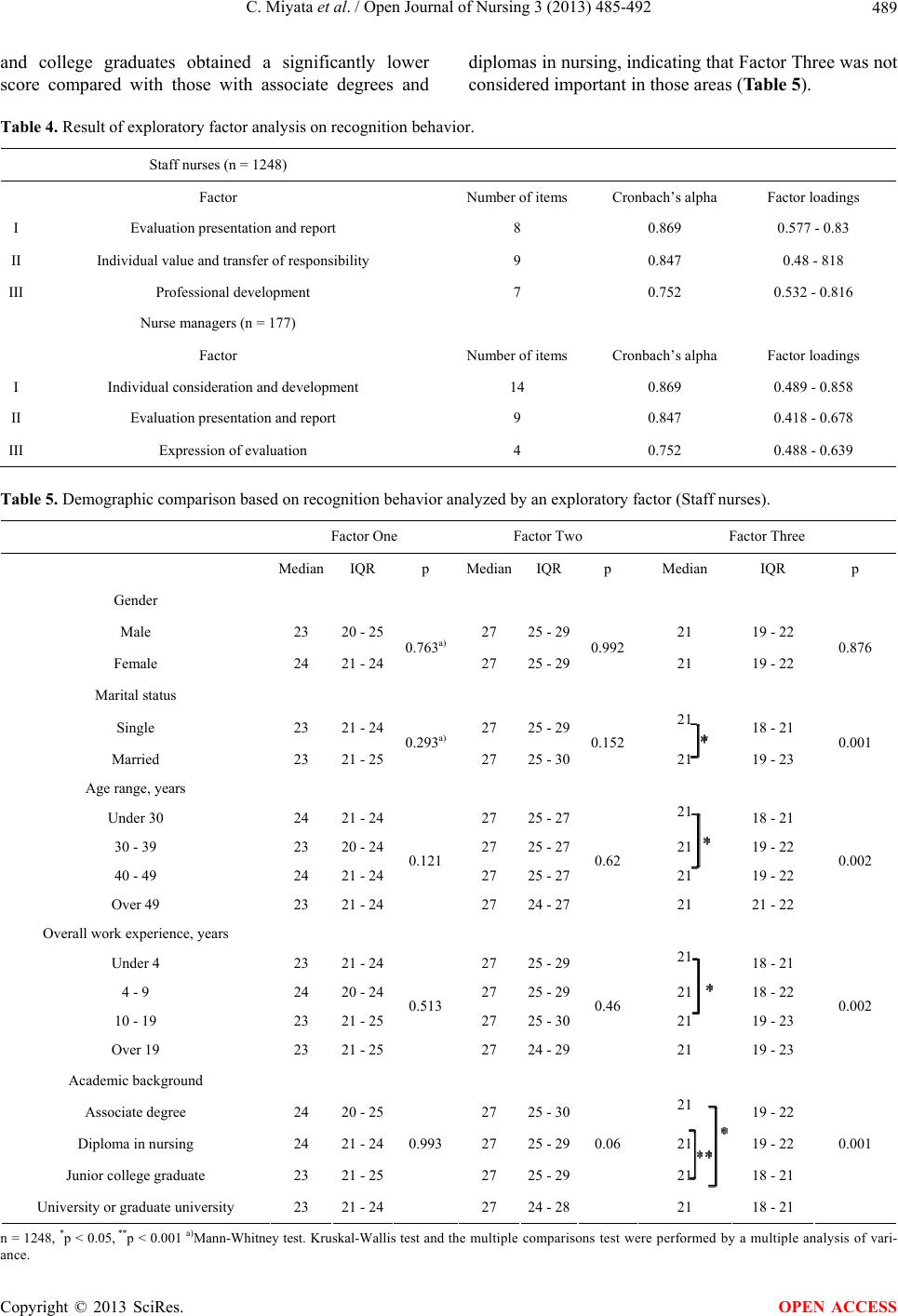

|