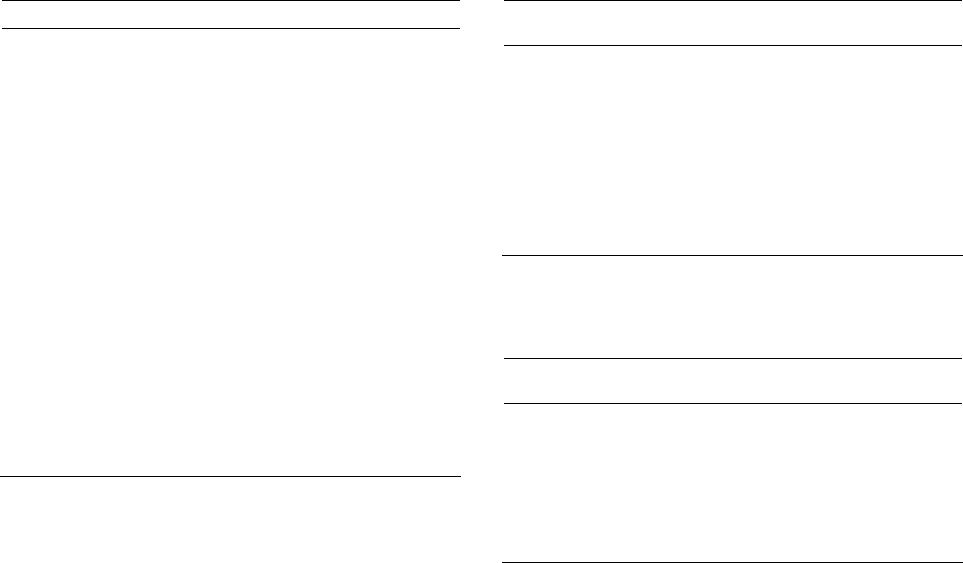

Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 2013, 1, 67-84 Published Online November 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jdaip) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jdaip.2013.14008 Open Access JDAIP Analysis of Factors That Affect the Long-Term Survival of Small Businesses in Pretoria, South Africa Zeleke Worku Tshwane University of Technology Business School, Pretoria, South Africa Email: WorkuZ@tut.ac.za Received September 15, 2013; revised October 17, 2013; accepted October 31, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Zeleke Worku. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The paper is based on a 5-year follow-up study (2007 to 2012) of a random sample of 349 small business enterprises that operate in and around the city of Pretoria in South Africa. Data were gathered from each of the businesses on so- cioeconomic factors that were known to affect the long-term survival of small businesses. The objective of the study was to identify and quan tify key predictors of viability and long-term survival. Pearson’s chi-square tests of associations, binary logistic regression analysis and the Cox Proportional Hazards Model were used for screening of variables, and for estimating odds ratios and hazard ratios of key predictors of viability and long-term survival. The study found that 188 of the 349 businesses that took part in the study (54%) were not viable, and that the long-term survival and viability of small businesses were adversely af fected by lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of supervisory support to newly estab- lished businesses, and in ability to operators running newly established busin e sses to acquire relevant vocational skills. Keywords: Small Businesses; Entrepreneurial Skills; Vocational Skills; Odds Ratio; Hazard Ratio 1. Introduction This paper was based on a 5-year long study (2007 to 2012) of a random sample of 349 small and medium sized en- terprises conducting business in and around the city of Pretoria, South Africa in which factors responsible for failure in small businesses were investigated by using panel data analysis. At the end of the study, 188 of the 349 small businesses were not financially viable. The purpose of the study was to identify and quantify key va- riables that were responsible for failure in the 188 busi- nesses that were not viable. This is the first study of its kind in Pretoria, is exploratory in nature, and describes the current state of small businesses that are operating in Pretoria. 2. Background of Study According to the South African Small Enterprise Devel- opment Agency [1], 60% of South African small busi- nesses fail within their first year of operation. The agency has found that although the South African De- partment of Trade and Industry provides incentives and support to small and medium sized enterprises, the de- gree of support provided to newly established small businesses is grossly inadequate. As a result, small and medium sized enterprises are seen failing in a number of areas of specialization [1-4]. The purpose of this research was to identify factors that affect the growth and devel- opment of small enterprises that conduct business in and around Pretoria. The South African Chamber of Com- merce and Industry [2] has reported that more than 30% of the total gross domestic product of South Africa is attributed to small and medium-sized enterprises. Also, 20% of all units exported by South Africa are produced by small and medium-sized enterprises. It is impossible to grow the South African national economy on a sus- tainable basis without simultaneously achieving sus- tained growth and development in small and medium- sized enterprises [5]. Swanson [6] has reported that real- izing sustained growth and development in small and medium-sized enterprises is a critical requirement for achieving sustained growth and development at the na- tional level. Failure in small and medium-sized enter- prises amounts to failure in the national economy ac- cording to Zheng, O’Neill and Morrison [7], Friedman, Miles and Adams [8] and Nieman [9]. This particular study is essential for finding out the root causes of failure in small and medium-sized enterprises that are conduct- ing business in the Pretoria region of South Africa. Very few studies have been conducted so far in an d around the Z. WORKU 68 city of Pretoria. For this reason, this study carries sig- nificant weight and importance. Future researchers can use findings from this study for conducting large scale studies at other regions of South Africa. Small businesses and enterprises make a significant contribution to the South African national economy. The growth and development of national economies is de- pendent on the rate at which small enterprises grow. In recognition of this fact, the South African National Gov- ernment supports and actively promotes the growth and development of small businesses in South Africa [10]. However, the failure rate of newly established small businesses in South Africa is hi g h. 3. Objectives of Study The overall objective of this study was to identify key predictors of failure in small enterprises in Pretoria, and to propose feasible remedial actions so that support could be provided to struggling small business enterprises. The study had the following specific objectives: To describe the characteristics of small enterprises conducting busin e ss in and around Pretoria; To identify factors that adversely affect sustained growth and viability in small enterprises in Pretoria; and To propose suitable and feasible remedial actions that could assist small and medium-sized enterprises in Pretoria. 4. Research Questions This study aims to provide adequate answers to the fol- lowing researc h questions: What are the socioeconomic characteristics of small business enterprises operating in and around the city of Pretoria? What are the key factors that adversely affect long- term viability in newly established small enterprises operating in and around th e city of Pretoria? 5. Literature Review According to the South African Small Enterprise Devel- opment Agency [1], although the South African Gov- ernment promotes the growth and development of small and medium-sized enterprises by massively investing in local institutions such as the South African Centre for Small Business Promotion (CSBP), Ntsika Enterprise Promotion Agency and Khula Enterprise Finance, the failure rate in newly established Sou th African small and medium-sized enterprises is as high as 60%. The study conducted by Ladzani and Netswera [4] has found that small and medium-sized enterprises often fail due to lack of access to finance and lack of entrepreneurial skills. At the national level, South African small and medium-sized enterprises in all economic sectors are characterized by an acute shortage of entrepreneurial and technical skills and difficulty in raising finance from micro-lending in- stitutions at favourable rates [1]. According to research conducted by the South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry [2], the situation at the Pretoria region is not different from the situation at the national level. The purpose of the study is to identify and quantify key fac- tors that are responsible for failure in small and me- dium-sized enterprises operating in the Pretoria region. Findings obtained from the study conducted by the South African Small Enterprise Development Agency [1] show that 60% of all newly established small businesses in South Africa fail within their first year of operation. According to the report, although the South African De- partment of Trade and Industry provides incentives and support to small and medium sized enterprises, the de- gree of support provided is grossly inadequate. As a re- sult, small and medium sized enterprises are seen failing in a number of areas of specialization [1-4]. A cco rding to Zheng, O’Neill and Morrison [7], Friedman, Miles and Adams [8] and Nieman [9], it is essential to develop small and medium-sized business enterprises in order to develop national economies. To date, very few studies have been conducted in the Pretoria region to identify and quantify the key factors that are responsible for failure in small and medium- sized enterprises. Small Businesses are often regarded as high risk operations locally and globally due to the pres- ence of factors that are difficult to predict adequately [11]. According to Useem [12], it is essential to support and guide small busine ss enterprises in the early stage of establishment by providing them with supervisory and skills-related support and supervision. White [13] has found that small and medium-sized enterprises often ex- perience costly bureaucratic and administrative chal- lenges. In South Africa, small and medium-sized enter- prises are set up with minimal support an d guidan ce fro m the national Government although the duty of the na- tional Government is to create an enabling economic environment. The study was conducted against the back- ground of the need to obtain vital information that ex- plains why more than half of all newly established small and medium-sized enterprises fail in the first three years of their establishment in Pretoria. Findings from the study are valuable for providing meaningful assistance to businesses that operate in Pretoria. According to Lawal [14] and Joseph [15], small, micro and medium-sized enterprises are defined as an enter- prise with a maximum asset base of about 10 million Rand excluding land and working capital in which be- tween 10 and 300 employees work. According to Oboh [16], small, micro and medium-sized enterprises are de- fined as an enterprise that has an asset of between 2500 Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 69 and 20 million Rand excluding the cost of land and working capital. According to the National Small Busi- ness Act of South Africa [3], small, micro and medium- sized enterprises are defined as follows: Micro enterprises: With growth potential that in- volves the owner and family members or at the most four employees and whose turnover is below 150,000 Rand, the threshold for VAT registration; Small enterprises: With 5 to 100 employees and are owner-managed and fulfil all the trappings associated with formality . Medium-sized enterprises: With 100 to 200 employ- ees which are still owner-managed and fulfill all the trappings associated with formality. Small, Micro, Medium-scale Enterprises (SMMEs) are also defined as enterprises with a minimum asset base of 25 million Rand excluding the cost of land and working capital by the South African Department of Trade and Industry [3]. The rapid increase in consumer expenditure by resi- dents in the Pretoria region since the early 1990s and the fact that the overwhelming majority of township dwellers have chosen to stay in their townships has enabled small businesses to set up shop s with a view to render essential services to residents in the Pretoria region of Gauteng Province. The importance of small and medium-sized enterprises is well documented in terms of economic development, competitiveness, and innovation. The con- tribution and importance of small enterprises to the na- tional economy is based on the ability of the sector to create employment opportunities to the masses, utilize- tion of local resources, output expansion, transformation of traditional and local technology, the production of intermediate goods, the promotion of an even develop- ment, the reduction of income disparities, and its ability to increase the revenue base for the South African Gov- ernment. Small, micro and medium-sized enterprises (SMMEs) are of a great importance in the area of low capital and output ratio, op timal utilization of local inputs and other multiplier effect per unit of investment. The SMME sector is viewed by the South African Depart- ment of Trade and Industry [3] as the key element in fostering economic growth among the unemployed masses in urban and semi-urban parts of Pretoria. Small and medium-sized enterprises often use locally made and available technologies for operation, growth in SMMEs amounts to growth in local and indigenous technology. The SMME sector is crucially needed for achieving overall economic growth and for the alleviation of pov- erty among the masses. The SMME sector is supported by the South African Government as a means of building capacity in local entrepreneurs an d to promote the use of local raw materials, technologies and manpower. The SMME sector plays a critical role in job creation, skills development, technology transfer, and the allevia- tion of poverty among the unemployed. As a result, the South African Government regards the SMME sector as an engine of growth and economic expansion. The SMME sector in South Africa is similar to the SMME sectors in other Sub-Saharan African countries, and is exposed to high failure rate, lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of resources, lack of access to finance and lack of modern technology. Although growth in the SMME sec- tor is essential for establishing sustained growth in the overall economy, the sector is characterized by high fail- ure rate due to lack of en trepreneurial and techn ical skills that are essential at the market place [17]. According to the South African Department of Trade and Industry [3], small, micro and medium-sized enter- prises (SMMEs) contribute around 40% of South Af- rica’s gross domestic profit, and employ more than half of the private sector work- force. It is estimated that as much as 80% of new jobs in world economies are being created by SMMEs, and this makes the SMME sector a key player in the national economy. There are more than 1.5 million self-employed people in the SMME sector, and they contribute about 40% of the total remuneration in South Africa. The South African Department of Trade and Industry [3] promotes small businesses by imple- menting a number of key initiatives. Examples of such initiatives are the Centre for Small Business Promotion (CSBP), Ntsika Enterprise Promotion Agency and Khula Enterprise Finance. The CSBP implements and adminis- ters the aims of the national strategy, which includes job creation. The DTI has recently signed an agreement with the European Union which will see the EU donating R550m to start a risk capital fund for SMMEs. The fund will be administered by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and the European Investment Bank, and 90 enterprises will benefit. The IDC allocates 75% of new business loans to SMMEs. The South African Women’s Entrepreneur Network was rolled out country- wide in 2002, alongside manufacturing advisory centres in all provinces. Non-governmental organizations include the Small Enterprise Foundation, which has a microcredit programme aimed at micro-enterprises, and the Tshu- misano credit programme that specifically supports and promotes female entrepreneurs. The NTSIKA pro- gramme provides non-financial support services to the SMME sector, tackling issues like management devel- opment, marketing and business development services. The agency also helps with research and inter-business linkages. Khula offers financial support mechanisms to the sector. The financial products include loans, the na- tional credit guarantee system, grants and institutional capacity building. The KHULA programme provides micro-lending to newly established businesses. The BRAIN programme (Business Referral and Information Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 70 Network) offers basic information and essential service links to entrepreneurs. The BRAIN website includes in- formation about the government’s incentives and SMME support agencies, as well as links to business centres. The Franchise Advice and Information Network (FRAIN) programme strives to supply high quality information and support services to individuals and small businesses in order to promote growth and improvement in franchise businesses. The FRAIN programme is implemented by NAMAC (National Coordinating Office for Manufactur- ing Advisory Centres) with assistance from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). The Na- mac programme has developed an extensive delivery structure across South Africa that serves as a channel for the application of new tools, information, products and projects, thus enabling the effective delivery of solutions aimed at SMMEs. The emphasis is on Historically Dis- advantaged Individuals' (HDI) businesses. The Business Partners Limited (BPL) programme provides assistance to small and medium enterprises financially. The pro- gramme provides financial assistance at a cost of be- tween 150,000 Rand and 15 million Rand. The Tourism Enterprise Programme (TEP) supports small businesses in the tourism industry financially and technically. The main objectives of the programme are to encourage and facilitate the growth and expansion of small and medium enterprises in the tourism economy, resulting in job crea- tion and revenue generating opportunities. Primary em- phasis is placed on historically disadvantaged entrepre- neurs and enterprises. For example, at the World Parks Congress the TEP was instrumental in facilitated deals which provided employment for its beneficiaries. The National Small Business Office (NSBO) in SARS is the custodian of all small business tax and customs policy matters within SARS. The office exists to maximise compliance among small businesses while at the same time finding ways to reduce the compliance burden faced by these businesses in South Africa. There are various business structures that are suitable for small businesses. The structure of the business deter- mines the legal status of the business enterprise. De- pending on the nature of the business, the number of people involved, management capabilities, personal risk and future business plans, a suitable business structure can be chosen for a newly established company. A sole- trading company is suitable for running a business that has no fixed assets. The owner is the sole employee. In- come accrues directly to the owner and there are no complicated statutory returns other than meeting basic legal and tax requirements. The disadvantage is that the business is not a separate legal entity, so the owner is liable for, and can be sued for, the business’s debts. If the owner of the business dies, the business ceases to exist. A business based on partnership enables 20 or fewer partners to operate a business by pooling their resources and skills together. A close corporation (CC) company enables a business a separate legal identity without the formalities of the Companies Act that governs (Pty) Ltd companies. This structure is ideal for a business that purchases stock on credit. A CC company can have be- tween one and 10 m embers, each of whom owns an agreed percentage o f the b usi ness a nd w ho i s li abl e for managing it properly. A CC cannot be owned by a company or be a subsidiary of another CC or company. A CC (rather than its members) can sue and be sued. All CC companies in South Africa are governed by the Close Corporations Act, which is administered by the Companies and Intellectual Property Registra tion Of f ice ( C IP RO ). A review of the literature shows that small and me- dium-sized enterprises are often beset by a host of factors that curtail their survival. In the majority of Sub-Saharan African countries, the most no table obstacles to sustained growth and development are lack of access to finance [18], the acute shortage of entrepreneurial skills [19], poor infrastructural development [20] and heavy bu- reaucracy and legislative obstacles [21]. The study con- ducted by Chapman [22] has found that superior and well-proven entrepreneurial skills are essential for estab- lishing viable small, micro and medium enterprises glob- ally, and that business operators who lack entrepreneurial skills must aspire to improve their capacity of business leadership constantly. The South African Government aims to use small and medium-sized enterprises for the creation of employment opportunities for the masses. To this end, the South Af- rican Government has invested heavily in the sector with a view to foster economic growth, job creation and the alleviation of poverty at the national level. The South African Government has an agreement with the European Union in the European Union donates 550 million Rand for establishing a risk capital fund for small and medium- sized enterprises [1 ]. According to Useem [12], th e qual- ity of entrepreneurial skills and leadership is a critical factor that determines the survival of small businesses. Ratten and Suseno [23] have reported that although access to finance is critical for the growth and develop- ment of small businesses, entrepreneurial skills are equally important. Small and medium-sized enterprises in the Pretoria are similar to enterprises in other parts of South Africa. They are characterized by a high failure rate in the first three years of establishment, lack of en- trepreneurial skills, failure to assess the market condition, failure to utilize financial and logistical resources pru- dently, poor quality of leadersh ip, the wastage and abuse of scarce resources, failure to meet the expectations of customers, inability to acquire training on essential en- trepreneurial skills, and failure to dr aw up business plans for their operations. Lack of leadership is a critical prob- Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 71 lem in the SMME sector. According to Rowe, small and medium-sized enterprises that perish in their first three years of establishment are often characterized by poor leadership qualities and poor organizational skills. Entrepreneurial skills are essential for steering small businesses in a manner in which they are profitable and viable. A good entrepreneur has good leadership skills. Such leadership skills and the ability to make the right choices enable small businesses to thrive under difficult circumstances. Leadership skills are key attributes of successful companies locally and globally [25]. Yuki [26] has found that superior leadership skills and entrepre- neurrial success are inseparable. According to Yuki [26], good business leaders adhere to the key principles of corporate governance. These principles are accountabil- ity and transparency. In this regard, Abor and Biekpe [27] have reported that good corporate governance and sound leadership skills are critically needed in small and me- dium-sized enterprises. In successful businesses, signify- cant market research is conducted by leaders and stake- holders. In addition, business processes are well defined in order to cut down operational cost. Industry bench- marks and standards of service delivery are adhered to by business leaders as a means of satisfying the needs and requirements of customers. The study conducted in Ghana by Carmingnani [28] has found that the viable small, micro and medium-sized enterprises set up in Ghana are often led by competent business leaders with superior entrepreneurial skills and sound market research experience. The study conducted by Coelho and Matias [29] shows that entrepreneurial success depends on market condi- tions, the possession of adequate skills and capital, and the ability of business owners to secure a reliable clien- tele base. Doom, Milis, Poelmans and Bloemen [30] have found that high performance institutions and vibrant small businesses require superior technical and entrepre- neurial skills and the ability to negotiate amicable terms of service delivery with potential customers at the mar- ketplace. Globally, all national governments of the world’s lead- ing economies actively support the Small, Micro and Medium Enterprises (SMME) sector globally [31]. Sup- port is provided to the SMME sector in various ways. One commonly used method of providing SMMEs with support is the adoption of tax-related policies that pro- vide preferential treatment to newly established small businesses [32]. The study by Hussey and Eagan [33] has shown that small and medium enterprises that thrive to protect the environment are often granted tax breaks in view of their contribution to values that are deemed im- portant to the national economy. The other commonly used method of supporting small and medium-sized en- terprises is the provision of skills-based and entrepre- neurrial trainings free of charge [34]. Small and me- dium-sized enterprises that spend significant resources in promoting basic innovation and research and develop- ment are often provided with adequate support by na- tional governments as a means of promoting science and technology in the economic sector. In this regard, the most notable examples are small and medium-sized en- terprises in countries such as China, South Korea, Sin- gapore and Japan [35]. The rationale of providing such support is motivated by the desire to use the SMME sec- tor as a driver of national technological advancement [36]. Keller [37] has reported that superior business leader- ship is required for ensuring the survival of small busi- nesses in competitive markets. Qian, Theodore, Peng and Zeming [38] have f ound th at superior business lead ersh ip is a critical requirement for ensuring viability in small businesses, and that leadership skills must be constantly improved by business leaders. The study by Luke [39] has found that the ability to provide superior services at competitive price is a critical requirement for establish- ing reputation. The ethical aspect of conducting business carries enormous weight in the eyes of customers. This is especially true in newly established businesses because newly established businesses often take a long period of time before they can establish their credibility at the market place. In South Africa, a series of procedures need to be fol- lowed in order to set up a small business. Newly estab- lished businesses must be registered with the South Af- rican Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and the South African Receiver of Revenues [3]. The registration of closed corporations (CC companies) is governed by the Closed Corporation s Act. The Act is administered by the Companies and Intellectual Property Registration Office (CIPRO). The establishment of private companies (PTY) or Limited Companies (Ltd) is also governed by an Act in South Africa. Such companies need to be au- dited annually. For this reason, auditing skills are essen- tial in setting up PTY or Ltd companies. In order to set up a new small business, it is essential to have adequate capital, stock and a good marketing skill. Working capi- tal is needed for at least six months according to guide- lines set out by the South African Department of Trade and Industry (2013: 3) to new beginners. The guideline recommends that new entrepreneurs must have th e ability to determine their start-up cost. Such entrepreneurs must be able to take inventory, draw up a list of items that need to be stocked and ordered, estimate selling prices, and market their goods and services effectively. Failure to have such skills often results in a loss and failure [40]. According to Meyer and Heppard [41], start-up costs include expenses before the starting date such as market research, registration fees, legal fees, office stationery, Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 72 design and printing of corporate identity (business cards and letterheads), registration of a domain name and crea- tion of a website, installations and utility connections (if moving into a new property), start-up inventory, cash reserve to support the company during the early months before sales reach break- even levels, current assets, such as fixtures and signage, office furniture and vehicle, and fixed assets. Newly established businesses must make arrangements for overdrafts with their banks. Most banks demand collateral as a requirement for extending loan to new entrepreneurs. As such, it may not be easy for newly established businesses to borrow money from comer cial- banks at favourable rates. Lack of access to easy finance has been pointed out as a major cause of failure in SMMEs in most Sub-Saharan African countries [42]. Small businesses that are newly established in the Euro- pean Union benefit from superior infrastructure, high technological input and minimal bureaucracy. The same cannot be said about newly established small businesses in Sub-Saharan African countries including South Africa [43]. Newly established small businesses are often ex- posed to hidden costs such as wastage of valuable time on bureaucracy, water and light expenses, telephone fees, transportation cost, maintenance fees, employee turnover, outsourcing functions, and the payment of commission and administration fees to service providers. Most newly established businesses pay consultants to set up business plans. They also pay fees to have their tax returns com- pleted and submitted in time. The cost of renting busi- ness premises in central business districts is often a cost- ly exercise for newly established small businesses [44]. Newly established small businesses often do not have the skills to manage their cash flow an d perform auditing exercises. The study conducted by McGrath and Mac- millan [45] indicates that auditing and accounting skills are essential for viability in small and medium-sized en- terprises. According to the researchers, newly established firms are often characterized by over-spending, wastage of scarce resources such as time, failure to take stock and inventory, failure to order items that are needed in time and in good quantity, and lack of skills in welcoming constructive suggestions from potential customers. Lynn [46] has reported that failure to manage or control fi- nances according to approved business plans is a differ- ential factor that adversely affects business processes in newly established firms globally, and that su ch problems are rampant in the world’s poorly developed economies. Poor cash flow is one of the major causes of failure in small businesses. Businesses may be profitable. However, if they fail to manage cash flow issues efficiently, they could easily go bankrupt. The ability to manage cash flow enables business owners and operators to forecast their cash flow. Cash flow problems are abundant in South African small and medium-sized enterprises due to lack of formal education in the preparation of business plans, forecasting, auditing and accounting among busi- ness owners and oper ators. In this regard, the problem in the Pretoria region of Gauteng Province is not so differ- ent from the problem in all South African metropolitan cities. There is an acute need for training newly estab- lished businesses on auditing, accounting, business plan preparation, report writing, oral presentations, stock tak- ing and inventory. The majority of small businesses fail to acquire tech- nical assistance in areas related to auditing and account- ing in an attempt to save cost. The ability to develop a cash flow forecast enables business operators to estimate the amount of money that is likely to flow into and out of their business over a period of time, thereby enabling them to allocate suitable budgets for their operations, set realistic targets and operational budgets, and monitor their overall performance. Mullins [47] has pointed out that efficient organizational skills are essential for viab il- ity in small business enterprises, and that such skills en- able business operators to manage utilization of their resources effectively. According to O’Dwyer, Gilmore and Carson [48], bu- siness operators, managers and owners working in newly established enterprises must have th e ability to determine what portion of their sales should be kept in cash, what purchases should be made in order to secure enough stock, when such stock must be ordered and purchased, how much opening stock is needed, how much capital is required, how much loan is needed for operational re- quirements and needs, where such loans should be ob- tained, the rate at which loans shou ld be raised, the list of routine daily, weekly and monthly expenses, ways and means of reducing such expenses, fees paid for employ- ees in exchange for their labour-related services, how much monthly salaries should be paid out to employees, and how marketing should be done to potential custom- ers. According to O’Donnell [49], it is essential to have adequate information on the cost of similar goods and services by rival business operators. Based on findings from the study conducted by Porter and Tanner [50], th e world’s most successful and vibrant small businesses and enterprises are characterized by service excellence, dedication for satisfying their cus- tomers, research, innovation and development, and atten- tion to quality. In this regard, small and medium-sized enterprises in Sub-Saharan African countries including South Africa are characterized by lack of entrepreneurial skills and relatively lower professional standards. The authors argue that service excellence often leads to a solid and sustainable customer base, and that dedication for rendering quality services is a requirement for sus- tained growth and development at the market place. The level of skills possessed by the majority of business op- Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 73 erators in newly established businesses is often poor. As such, operators working in newly established businesses must be dedicated for achieving service excellence and reliable clientele. However, it is impossible to secure reliable clientele without demonstrating devotion for service excellence [51]. The study by Chetty and Stangl [52] has found that dedication for service excellence is a key requirement for credibility at the marketplace, and that newly established businesses cannot survive without possessing solid reputation and credibility at the market place. This assessment is consistent with findings re- ported by Bekele and Worku [53], Carroll and Wagar [54], Cooper and Schindler [20] and Bosworth [21]. Ac- cording to Abor and Adjasi [55], the vast majority of newly established businesses that fail in their first three years of establishment are characterized by poor repute- tion and low entrep reneurial sk ills in the eyes o f potential customers, and often struggle to establish credibility. This explains why service excellence is critically needed in newly established small and medium-sized enterprises in the Pretoria region of Gauteng Province. It follows that newly established firms need to allocate enough re- sources for the acquisition of essential entrepreneurial and technical skills in their first three years of establish- ment. Ingstrup [56], Isaksson [57], Jack, Moult, Anderson & Dodd [58] and Jiang & Mike [59] have suggested useful methods of minimizing operational cost at newly estab- lished small enterprises. These methods include keeping overheads down, avoiding credit terms, debt collection, improving supplier payment terms, keeping stock to a minimum. The study conducted by Jagoda, Maheshwari and Lonseth [60] has found that newly established small businesses must not possess more stock than is needed because they could easily tie up all their free cash in stocks that are too difficult to sell fast enough. Jonsson and Lindbergh [61] have found that newly established businesses often fail due to lack of mentorship pro- grammes and lack of accurate market-related information. Maine, Shapiro and Vining [62] have reported that newly established businesses need to develop capacity for the effective and timely utilization of market-related infor- mation. The authors have also found that new entrepre- neurs have a tendency for rendering services on credit, and that such a practice often leads to bankruptcy in most economies. According to Kozovska [63], efficient debt collection requires business owners and operators to be aggressive in demanding monies that are owed by cus- tomers. If businesses fail to collect debt in time, they stand to go bankrupt. Malhotra and Temponi [64] have found that the ability to collect outstanding debt from customers in time is critical for the survival of newly established businesses. The cost of labour and human capital is often high in South African businesses. It is essential for newly estab- lished businesses to save cost by minimizing labour. At the Pretoria region, a few small businesses make an at- tempt to use family members as a means of saving mo- ney that should otherwise be paid for labour. The prac- tice becomes useful if family members possess the entre- preneurial skills that are needed for business operation. Otherwise, the practice could be detrimental for sus- tained growth. Zhu, Chew and Spangler [65] have re- ported that the ability to utilize human capital efficiently as well as leadership and organizational qualities are es- sential for long term survival and viability in small and medium-sized enterprises globally. According to Foster [66], the cost of labour and capital in small business en- terprises should be managed at competitive rates based on market conditions. The cost of goods and services fluctuates seasonally. The cost of some goods and ser- vices increases depending on demand that comes in cer- tain seasons of the year. For example, the cost of warm clothes and winter shoes increases in winter. It would be prudent to keep extra stock for the next season in cases where it is not possible to sell such items currently. The other innovative method of managing cash flow is to allow customers to pay phase by phase depending on how much they can afford. However, in selling items on credit, the proper paperwork and procedures must be followed as a means of avoiding loss. In some cases, late payment should be allowed by debtors. According to Hashim, Ahmad and Leng [17], good leadership is a pre-requisite for the effective accom- plishment of organizational tasks in small and medium- sized business enterprises globally. The style of leader- ship of an entrepreneur has a significant bearing on the ability of the business enterprise to win and retain loyal customers on a sustainable basis. Good leaders have the ability to interact with their potential customers effec- tively. In cases where there are complaints from custom- ers, good leaders have the ability to resolve disputes and misunderstandings promptly to the complete satisfaction of customers. Such a track record counts heavily in the eyes of the community. Good business leaders foster in- tegrity, good leadership, and high efficiency in the eyes of potential customers. Different leadership styles result in different organizational effectiveness and performance in small and medium-sized enterprises. Workers employed in business enterprises where the leadership is autocratic in style are less efficient and productive in comparison with workers employed in business enterprises where the leadership is democratic [57]. The styles of managerial leadership towards subor- dinate staff and the focus of power can be classified into three categories. The authoritarian style of leadership is autocratic, and the focus of power is with the manager and all interactions within the group move towards the Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 74 manager. The manager alone exercises decision-making and authority for determining policy, procedures for achieving goals, work tasks and relationsh ips , control of rewards or puni shment [47]. The ability to respond to queries from customers and the manner in which customers are treated are crucially important for viability in small businesses. The study by Harms, Kraus and Reschke [67] shows that small and medium-sized enterprises that fail to respond to queries made by customers often fail in the first three years of their existence. A good ex ample in this regard is the fail- ure of over 50% of all newly established small busi- nesses in areas such as Soweto, Alexandra, Tembisa and Sebokeng in their first three years of establishment over the period from 1994 to 2012 [2]. Street vendors often thrive in areas where formally setup small businesses fail. Consumers have a tendency to look for competitive prices at all times. This indicates that small businesses must be adequately informed about the selling price of goods and services. This requires the ability to do re- search in the market by gathering information on selling price and the quality of goods and services. Judge and Piccolo [68] have found that good entre- preneurs have good business leadersh ip skills. Accord ing to the authors, leadership skills such as learning from competitors and fellow subordinates are quite helpful. The other key leadership skills are the ability to improve organizational leadership and performance by improving the degree of customer satisfaction, staff satisfaction, and financial performance. Understanding leadership is im- portant to small and medium scale enterprises (SMMEs) because leadership binds subordinates to work together and stimulate employees’ motivation. Effective leader- ship provides the building block for organizational per- formance. It is absolutely essential to the survival and growth of every organization. Autocratic leadership is detrimental to the growth of businesses. In autocratic business institutions, the leaders are not democratic enough in their relations with their sub-ordinate, and problems that affect organizational performance are not frankly and effectively brough t to the attention of leaders for fear of reprisal. As a result, overall productivity is low. 6. Methods and Materials of Study The study design of the research is longitudinal (01 January 2007 to 31 December 2012) and descriptive. Data was gathered from a random sample of 349 small businesses and enterprises conducting business in and around the city of Pretoria. Data was gathered on a large number of socio-economic variables that affect the long- term survival of businesses. Data were gathered regularly from each of the 349 small business enterprises regularly on a monthly basis during the period of study by a Doc- toral student enrolled at the Business School of Tshwane University of Technology in Pretoria. Table 1 shows the list of variables based on which data was collected from each of the enterprises. Some of the variables were measured based on an ordinal scale that varied from 1 (lowest possible value) to 5 (highest possible value). Some of the variables were nominal variables (Yes, No). The remaining variables were nu- meric variables that had to be measured in numbers. Example: Duration of operation of business in years. Statistical data analysis was done by using Pearson’s chi-square tests of association [69], binary logistic re- gression analysis [70] and the Cox Proportional Hazards Model [71]. Binary logistic regression analysis [70] was used for estimating odds ratios. The outcome variable Y is di- chotomous, and has only 2 categories. That is, 1ifbusiness isnotviable 0otherwise Y 12 ,,, k XX ˆ are a combination of k discrete and con- tinuous explanatory variables that affect the dependent variable Y. An estimated regression coefficient is denoted by . In logistic regression analysis, a regression coef- ficient is estimated for each explanatory variable in- cluded in the model. In general, the binary logistic re- gression of a dichotomous outcome variable Y on a com- bination of k discrete and continuous independent vari- ables 12 ,,, k XX is defined by the following logit function: 011 ˆˆˆ logln 1 i ik i p it pXX p k The odds ratio corresponding to the explanatory variable i th i is equal to ˆ exp where ˆi denotes the estimated regression coefficient corresponding to i . The hazard function for the Cox Proportional Hazards Model [71] is gi ven by: 01 ,exp p ii i htXh tX where 1,, XX is a collection of p explanatory variables that affect survival time. The Cox model uses survival times and censoring for the estimation of parameters. In Cox regression, the measure of effect is the hazard ratio, which involves only the ’s. Estimates of the ’s are maximum likelihood estimates. 0 ht is the baseline hazard function. It in- volves t, but not the X variables. Some of the 349 busi- nesses in the study were right censored. Odds ratios were estimated by performing binary logistic regression analy- sis under the random effects assumption. Hazard ratios Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU Open Access JDAIP 75 Table 1. List of variables of study and their levels. Variable of study Possible values Category of business Automotive sale or repair Carpentry or maintenance Music or DVD shop Convenience store Food outlet Liquor store Travel and lodging services Child care services Computer and internet shop Secretarial services Health, beauty and fitness services Home based services Professional consultancy Legal services Security services Transport services Low cost franchise Retail franchise Sports and recreation services Others Duration of operation Duration in years Amount of start-up capital in Rand Amount in Rand Source of start-up capital Own, Borrowed, Others Amount of current capital in Rand Amount in Rand Amount of tax paid in Rand at the end of last y ear Amount in Rand Level of education of operator Primary or less Secondary Diploma Degree or above Business being conducted by owner or employed manager Owner, Employed manager Gender of business operator Male, Female Level of entrepreneurial skill of operator 1) if poor 2) if below average 3) if average 4) if above average 5) if good Level of auditing skills 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Level of book-keeping skills 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Level of report-writing skills 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Level of presentation skills 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Existence of a business plan Yes, No Access to training on entrepreneurial skills Yes, No Employment of a technical assistant or consultant for preparing a business plan or ta x a sse ssment report Yes, No Supervisory assistance from t he Department of Trade and Industry Yes, No Monitoring and evaluation assistance from the Department of Trade and Industry Yes, No Experience of having to borrow a loan Yes, No Total revenue in Rand at end of most recent month Total revenue in Rand Amount of loan bo rrowed in Rand Amount in Rand Ease of securing a loan Easy, Difficult Reason for taking loan Reason Existence of unpaid loan Yes, No Experience of needing collateral for securing loan Yes, No Ownership of premises Yes, No Amount of money paid for rent per month Amount in Rand Amount of money paid for water and lights per month Amount in Rand Number of full time employees Number of employees  Z. WORKU 76 Continued Suitability of business premises for conducting business Yes, No Source of supplies Private, Government, Others Amount of profit made at the end of last year in Rand Profit made in Rand Experience of a financial loss Yes, No Failure to file a tax return Yes, No Experience of a labour dispute Yes, No Extent to which business has been affected by inflation 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Ease at which money could be borrowed from the commercial banks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Degree of convenience of borrowing money from the commercial banks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Perception on the fairness of terms of repaym en t to commercial banks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Ease at which money could be borrowed from micro-lenders 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Degree of convenience of borrowing m oney from micro-lenders 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Perception on the fairness of terms of repayment to micro-lenders 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Experience of selling on credit Yes, No Having a solid clientele base Yes, No Level of demand for goods or service s 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Perception on the degree of assistance provided by the South African Government 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 were estimated by performing panel data analysis based on the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Estimated odds ratios an d hazard ratios were used as a meas ure of ef fect, and for ranking influential predictors of viability and survival in order of their strength. Kaplan-Meier survival probability curves were used for comparing viable and non-viable businesses with regards to the most influential predictor variable (level of entrepreneurial skills). Descriptive and summary statis- tics were also obtained. The adequacy of the fitted Cox regression model was assessed using the likelihood ratio test and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) statistic. The fulfilment of the proportional hazards assumption was tested by use of log-minus-log plots. The duration of survival of businesses was measured for each of the 349 enterprises in the study by using 01 January 2007 as the starting point. Enterprises that were still operational at the end of the study period (31 December 2012) were considered right-censored observations as their exact durations of survival could not be measured due to ad- ministrative censoring (inability to measure the survival times of businesses beyond the date at which the study came to an end) at the en d of the study period. For enter- prises that ceased operation prior to 31 December 2012, survival time was defined as the number of days of op- eration between 01 January 2007 and the date of closure. The Cox Proportional Hazards Model takes censored observations into account, and this property of the model makes it quite attractive in comparison with other models used for panel data analysis in economic studies [71,72]. In Cox regression, hazard ratios are used as an econo- metric measure of effect. Key predictors of survival are identified and estimated based on hazard ratios. Kap- lan-Meier survival probability curves were used for comparing businesses that survived the 5-year study pe- riod (viable businesses ) with businesses that did not sur- vive the study period (non-viable businesses ) with re- gards to key predictors of survival. Kaplan-Meier sur- vival probability curves were used for comparing viable businesses with non-viab le businesses graphically. At the 5% level of significance, influentialpredictors of survival are characterized by hazard ratios that differ from 1 sig- nificantly, 95% confidence intervals of hazard ratios that do not contain 1, and P-values that are smaller than 0.05. 7. Results of Data Analysis Table 2 shows the distribution of factors that affect the long-term survival of enterprises for viable and non-vi- able businesses. The table provides frequency propor- tions for 6 key predictors of viability and long-term sur- vival for viable and non-viable businesses. In the 5-year- study period, 188 of the 349 businesses in the study (54%) failed while the remaining 161 businesses (46%) man- aged to survive. The table shows that 68% of viab le busi- nesses possessed adequate entrepreneurial skills whereas only 26% of non-viable businesses did the same. Viable businesses managed to acquire adequate supervisory su- pport when they were newly established (51%). The cor- responding figure for non-viable businesses was 27%. The level of vocational skills possessed by viable busi- nesses (77%) was relatively higher than the level of vo- cational skills possessed by non- viable businesses (38%). Viable businesses were able to secure loans relatively easily (74%) in comparison with non-viable businesses (37%). Viable businesses were operated by managers with relatively higher levels of formal education (71%) in comparison with non-viable businesses (43%). Non- Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 77 Table 2. Group proportions with regards to the financial viability of small businesses. Predictor variable Viable (n = 161) Not viable (n = 188) Level of entrepreneurial skills Adequate: 68% Inadequate: 32% Adequate: 26% Inadequate: 74% Acquisition of supervisory support by newly established small businesses Adequate: 51% Inadequate: 49% Adequate: 27% Inadequate: 73% Level of relevant vocational skills acquired by business operator Adequate: 77% Inadequate: 33% Adequate: 38% Inadequate: 62% Ability to secure loan needed for operation Easy: 74% Difficult: 26% Easy: 37% Difficult: 63% Level of formal education acquired by business operator College level or above: 71% Below college level: 29% College level or above: 43% Below college level: 57% Past history of bankruptcy Yes: 11% No: 89% Yes: 58% No: 42% viable businesses were characterized by a past history of bankruptcy (58%). The corresponding figure for viable busin esses was only 11%. Table 3, below, shows adjusted odds ratios estimated from binary logistic regression analysis in which the ran- dom effects model was used. It can be seen from the ta- ble that viability in small businesses is significantly in- fluenced by 4 predictor variables. The 4 influential pre- dictor variables are lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of supervisory support to newly established small busi- nesses, inability to acquire relevant vocational skills, and low initial capital, in a decreasing order of strength. The most influential predictor variable affecting long-term viability and survival is lack of entrepreneurial skills. The percentage of overall correct classification for the fitted logistic regression model was equal to 89.07%. The P-value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was equal to 0.1076 > 0.05, thereby indicating that the fitted logistic regression model was theoretically reliable. Hazard ratios estimated from the Cox Proportional Hazards Model are shown below in Table 4. It can be seen from the table that viability in small businesses was significantly influenced by 3 factors. The 3 influential predictor variables are lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of supervisory support to newly established small busi- nesses, and inability to acquire relevant vocational skills, in a decreasing order of strength. The most influential predictor variable affecting long-term viability and sur- vival is lack of entrepreneurial skills. It can be seen from Tables 3 and 4 that hazard ratios estimated from the Cox Proportional Hazards Model Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios estimated from binary logistic regression analysis. Variable *Adjusted Odds Ratio P-value 95% C.I. Lack of entrepreneurial skills 3.86 0.000 (1.43, 6.02) Lack of supervisory support to newly established small businesses 3.54 0.000 (1.71, 5.96) Inability to acquire relevant vocational skills3.27 0.000 (1.77, 5.81) Low initial capital 2.03 0.004 (0.35, 3.42) *Adjustme nt was done for geographical location, age of owner and gender. Table 4. Adjusted hazard ratios from the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Variable *Adjusted Hazard Ratio P-value95% C.I. Lack of entrepreneurial skills 3.87 0.000(1.44, 6.01) Lack of supervisory support to newly established small businesses3.55 0.000(1.72, 5.94) Inability to acquire relevant vocational skills3.29 0.000(1.79, 5.83) *Adjustme nt was done for geographical location, age of owner and gender. were fairly similar to odds ratios estimated from binary logistic regression analysis. In view of the fact that the design of the study is longitudinal, and not cross-sec- tional, hazard ratios estimated from the Cox Proportional Hazards Model carry more weight theoretically in com- parison with odds ratios estimated from binary logistic regression model. As such, interpretation of results will be made based on hazard ratios. The hazard ratio of the variable “Lack of entrepre- neurial skills” is 3.87. This shows that businesses that are run by operators who do not have adequate entrepre- neurial skills are 3.87 times more likely to fail in com- parison with businesses that are run by operators who have adequate entrepreneurial skills. It can be seen from Table 1 that 68% of the 161 viable businesses in the study were run by operators who had adequate entrepre- neurial skills, whereas only 26% of the 188 non-viable businesses in the study were run by operators who had adequate entrepreneurial skills. The hazard ratio of the variable “Lack of supervisory support to newly estab- lished small businesses” is 3.55. This shows that newly established businesses that had inadequate supervisory support were 3.55 times as likely to fail in comparison with businesses that enjoyed adequate supervisory sup- port. The hazard ratio of the variable “Inability to ac- quire relevant vocational skills” is 3.29. This shows that businesses that were run by operators with poor vo- Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 78 cational skills were 3.29 times as likely to fail in com- parison with businesses that were run by operators with adequate vocational skills. Adjustment was done for three potential confounding variables: geographical loca- tion of business in the city, age of owner and gender of owner. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios did not differ much. This shows that none of the three variables used for adjustment was a confounding or effect modify- ing variable. The adequacy of the fitted Cox model was assessed using log-minus-log plots, the likelihood ratio test and the AIC (Akaike’s Information Criterion) as di- agnostic procedures. All log-minus-log plots were paral- lel, showing that the assumption of proportional hazards was satisfied. The P-value from the likelihood ratio test was small (0.0001 < 0.01), thereby showing that the 6 variables constituting the fitted Cox model were jointly efficient in explaining variability in long term survival at the 1% level of significance. The estimated value of the AIC statistic was also small (10.01), thereby showing that the discrepancy between the fitted and true models was insignificant [73]. Kaplan-Meier survival probability plots were used for comparing the survival probabilities of viable and non- viable businesses with regards to entrepreneurial skills. It can be seen from Figure 1 that businesses that were run by operators with adequate entrepreneurial skills have a relatively larger probability of survival in comparison with businesses that were run by operators with inade- quate entrepreneurial skills. 8. Discussion of Results The study has found that 188 of the 349 businesses that took part in the study (54%) were not viable, and that the long-term survival and viability of small businesses was adversely affected by lack of entrepreneurial skills, lack of supervisory support to newly established businesses, and inability to operators running newly established 0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 020 40 60 analysis time Adequate skillsInadequate skills Kaplan-Meier survival estimates Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities by level of entrepreneurial skills. businesses to acquire relevant vocational skills. The 188 non-viable businesses in the study (46%) were charac- terized by low level of entrepreneurial skills, low level of supervisory support, lack of relevant vocational skills, difficulty in securing loans, low level of formal education, and a past history of bankruptcy. The study has shown that businesses that were run by operators with adequate entrepreneurial skills have survived much better than those that were run by operators who did not possess adequate entrepreneurial skills. Results obtained from Pearson’s chi-square tests of associations (P < 0.05) showed that businesses fail due to lack of initial capital, failure to utilize finance in accordance with business plan, high labour cost, shortage of entrepreneurial skills that are needed for operating business, adverse market condi- tions, difficulty in securing loans needed for business, inability to pay fees that are required for renting business premises, inability to draw up business plans, inability to do bookkeeping, the practice of selling on credit, the status of business being operated, and lack of training opportunities that are relevant to the business being op- erated. Businesses that failed were characterized by loss of money, inability to draw up business plans, inability to do book-keeping, inability to acquire technical and voca- tional skills due to shortage of finance. The key findings of this study are in agreement with results reported by Jiang & Mike [59], Globerman, Peng & Shapiro [74], Zoogah, Vora, Richard & Peng [75], Peng, Rabi & Sea- Jin [76] and Daley-Harris [77]. The South African edu- cational curriculum does not prepare potential entrepre- neurs adequately for the task of operating newly estab- lished businesses. The content of the curriculum for vo- cational training at the high school and undergraduate level is vastly inadequate and irrelevant to the specific needs of young graduates who aspire to thrive in business. This failure constitutes a major obstacle to the growth and development in small and medium-sized businesses and enterprises in South Africa. The study has shown that the failure to utilize finance in accordance with business plan is detrimental for vi- ability, and that non-viable businesses are characterized by a past history of bankruptcy. Similar findings have been reported in other Sub-Saharan African and South- East Asian countries in which it has been found that suc- cessful businesses are often run by operators with sound entrepreneurial skills and fiscal discipline [78]. Success- ful operators improve their managerial, vocational and technical skills incrementally. Managerial ability was assessed in terms of the ability of owners or operators to produce sound business plans, perform standard book- keeping, auditing and record-keeping duties, introducing appropriate technologies and expertise, acquiring innova- tive business skills from rival enterprises, degree of mo- tivation and commitment in sharing useful experience Open Access JDAIP Z. WORKU 79 with employees, commitment in terms of empowering employees, investing in skills related training opportuni- ties for employees, ability in resolving business related disputes amicably, etc. Successful businesses and enter- prises were associated with managers who enjoyed what they were doing, whereas unsuccessful businesses and enterprises were associated with mangers with little or no motivation and commitment. Although there is an understanding that the SMME sector has the potential for contributing to the growth of the national economy, the sector needs to be supported by the national Government. The study conducted by Kumar, Antony, Madu, Montgomery and Park [78] has shown that the sustained growth of the national economy depends on the sustained growth of the SMME sector. This is especially true in developing economies such as South Africa. Klotz, Horman, Bi and Bechtel [79] have found that all tender procedures that might benefit small businesses and enterprises must be administered with adequate transparency as a means of supporting the SMME sector. Dasanyaka and Sardana [80] have found that strategic partnerships between national and provin- cial Governments as well as academic institutions benefit the SMME sector in terms of producing workable plans of actions. Edwards, Sengupta and Tsai [81] h ave argued that mentorship is critically helpful for reducing failure rate in newly established small enterprises. Studies con- ducted by Dougherty [82] and Estebanez, Grande & Co- lomina [83] have found that support mechanisms and supervision are critically needed for reducing failure rates in newly established enterprises. Rumiler and Brache [84] have reported that business processes that aim to benefit small, micro and medium enterprises must be free from bureaucratic procedures and bottlenecks in order to enable small businesses to reach their full poten- tial in the SMME sector of the economy. Black-owned enterprises conducting businesses in and around Pretoria need tangible support and mentorship in order to grow and make a sustainable contribution to job creation and the alleviation of poverty among the masses. The strategic benefit of entrepreneurial and managerial skills for the long term survival of small and medium- sized enterprises has been pointed out by Rummler and Brache [84] and Smith and Fingar [85]. Both authors have found that the lack of entrepreneurial and manage- rial skills constitutes a major obstacle to the development of SMMEs. These findings have been corroborated by Zhang [86], Wennberg & Lindqvist [87], Van Praag [88] and Sun & Liu [89] in which it has been found that the acute shortage of entrepreneurial and technical skills has become one of the key reasons why newly established small and medium-sized enterprises fail to grow on a sustainable basis. The study conducted by Hicks, Culley, Mc Mahon & Powell [90] has found that newly estab- lished small enterprises cannot thrive in situations where infrastructure is poorly developed. The constant shortage of entrepreneurial skills in small and small and medium- sized enterprises is further exacerbating the plight of emerging firms in and around Pretoria. The shortage of such skills is responsible for the high rate of failure of newly established companies. According to Clemens [18] and Wagner [91], it is strategically important to have access to skills-based programmes of training if newly established companies are to bridge the skills gap in the SMME sector. Business programmes that are offered by South African universities are not relevant to the survival needs of small and medium-sized enterprises. The ab- sence of accredited training programmes in this regard has aggravated problems that arise from the lack of tech- nical skills. Due to the nature of the SMME sector, access to fi- nance remains vital because projects can get delayed in cases where contractors fail to raise adequate working capital for the project being done. Since contractors are expected to utilize initial capital before claiming for work done, the extent to which they are able to access financial backing is fundamental. Under financial con- straints, small and small and medium-sized enterprises are likely to perform poorly on a contract [91]. Based on findings reported by Dowla [92], Harris & Rae [93], Hadaya & Pellerin [94], Mc Adam, Moffett, Hazlett & Shelvlin [95] and Curran & Blackburn [96], the key rea- son why the majority of newly established firms go out of business in the first three years following establish- ment is their inability to raise the finance needed for the completion of projects. Newly established businesses seek financial assistance from financial institutions such as the Industrial Devel- opment Compotation (IDC), Business Partners Limited (BPL), Khula Enterprise Finance Limited (KFL), as well as the big four South African commercial banks (Amal- gamated Bank of South Africa (ABSA), First National Bank (FNB), Standard Bank and Nedban k). Althoug h the commercial banks have adequate funds to lend, their lending policies are quite stringent, and are based on col- lateral. The other microfinance institutions do not have adequate funds to satisfy the needs of newly established firms. Also, their lending rates are quite high, and are not affordable to small enterprises. The study conducted by Smedlund [97] has shown that it is quite difficult and unaffordable for the majority of small enterprises to bor- row money on unfavourable terms from financial institu- tions conducting business. Basically, these financial in- stitutions have limited resources, and impose rather stringent repayment conditions on borrowers. This con- dition exacerbates the plight of newly established firms. Newly established firms often lack the ability to utilize borrowed money wisely and according to plan. They Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 80 have poor auditing, managerial and entrepreneurial skills. They do not report their progress at the workplace regu- larly to financial institutions that choose to lend them money. As a result, the majority of commercial banks and micro-lending financial institutions are often reluc- tant to lend monies to newly established small and me- dium-sized enterprises conducting business in the Preto- ria region of Gauteng Province. The academic curriculum used in South African terti- ary level academic institutions needs a fundamental overhaul and review in order for young graduates to ac- quire entrepreneurial and technical skills that are essen- tial for operating businesses successfully. Studies con- ducted by Bekele and Worku [53] and Zoogah, Vora, Richard and Peng [75] have found that the failure of ter- tiary level academic institutions to equip young graduates with skills that are relevant to the actual needs of society is the key reason why young graduates in the world’s least developed nations are virtually unemployable. 9. Recommendations Based on findings obtained from the study, the following recommendations are made to the South African De- partment of Trade and Industry, the South African De- partment of Higher Education and Training, and the South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry with a view to improve viability in small and medium-sized enterprises operating in the Pretoria region of Gauteng Province. The recommendations have the potential for improving the plight of struggling small and medium- sized enterprises in the region. It is necessary to design relevant and tailor-made skills based training programmes on vocational and entrepreneurial activities in which young matric graduates can be equipped with the skills they need to run businesses successfully; It is necessary to provide mentorship and supervisory assistance to newly established small and medium- sized enterprises fo r a period of at least three years or more; It is vital to encourage academic and research institu- tions to create academic programmes in which train- ees can acquire experiential training by working for businesses and industries as part of their academic training in South African institutions of higher learn- ing. Such programmes should be jointly coordinated and funded by the South African Department of Higher Education and Training, the South African Department of Trade and Industry, and the South Af- rican Chamber of Commerce. Doing so has the poten- tial for producing graduates who possess skills that are relevant to the actual needs of business, industry and government. It is necessary to monitor and evaluate the viability of newly established small businesses on a monthly ba- sis. This task falls under the ambit of the South Afri- can Department of Trade and Industry. Such an in- tervention has the potential for minimizing the rate at which newly established small businesses fail in and around the city of Pretoria. 10. Limitation of Study The study was conducted only in the Pretoria region of Gauteng Province in South Africa mostly due to shortage of resources. Small and medium-sized enterprises oper- ating in and around the city of Pretoria have a smaller capacity in terms of trade volume and exposure to the general South African market in comparison with busi- nesses that operate in and around the city of Johannes- burg. As such, it would be worthwhile to extend the study to the city of Johannesburg. Findings obtained from this particular study may not be generalized to businesses that operate in and around the city of Johan- nesburg. REFERENCES [1] South African Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA), “SAIE Learning Loop: Why the Loop?” 2013. http://www.entrepreneurship.co.za/page/small_business_r esources [2] South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry, “Business Confidence Index-Press Release,” 2013. http://www.sacci.org.za/ [3] South African Department of T rade and Industry, “SMME Development,” 2013. http://www.thedti.gov.za/sme_development/sme_develop ment.jsp [4] W. M. Ladzani and G. G. Netswera, “Support for Rural Small Businesses in Pretoria, South Africa,” Development Southern Africa, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2009, pp. 14-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03768350902899512 [5] E. Saru, “Organizational Learning and HRD: How Ap- propriate Are They for Small Firms?” Journal of Euro- pean Industrial Training, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2007, pp. 36-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090590710721727 [6] R. A. Swanson, “Analysis for Improving Performance,” Berrett-Koehler Publishers, London, 2007. [7] C. Zheng, G. O’Neill and M. Morrison, “Enhancing Chi- nese SME Performance through Innovative HR Prac- tices,” Journal of Personnel Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2011, pp. 175-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00483480910931334 [8] A. L. Friedman, S. Miles and C. Adams, “Small and Me- dium-Sized Enterprises and the Environment: Evaluation of a Specific Initiative Aimed at All Small and Medium- Sized Enterprises,” Journal of Small Business and Enter- prise Development, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2000, pp. 325-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006849 [9] G. Nieman, “Training Entrepreneurs and Small Business Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 81 Enterprise in South Africa: A Situational Analysis,” Journal of Education + Training, Vol. 1, No. 43, 2001, pp. 445-450. [10] South African Parliament, “Small Enterprise Development Agency Annual Report for 2011/2012,” 2013. http://www.pmg.org.za/report/ [11] E. B. Wagner, “Small Business Survival Relies on Grit, Perseverance,” American City Business Journals, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2003, pp. 1-4. [12] M. Useem, “How to Groom Leaders of the Future,” In: Financial Times Mastering Management, Prentice Hall, New York, 2001. [13] C. J. White, “Research: A Practical Guide,” Inthuthuko Publishing, Cape Town, 2005. [14] A. A. Lawal, “Management in Focus,” Abdul Industrial Enterprises, Lagos, 2005. [15] M. I. Joseph, “New Partnership for Micro, Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (MSMSEs),” Journal of Eco- nomic and Environmental Issues, Vol. 5, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 1-14 [16] G. Oboh, “Contemporary Issues on Banking: Issues on Financing Small and Medium Enterprises in Nigeria,” Percept Press Limited, Lagos, 2004. [17] M. K. Hashim, S. Ahmad and O. L. Leng, “Leadership Style and Job Satisfaction among Employees in SMMEs: Emerging Issues in Small and Medium Enterprises,” Universiti Utara Malaysia Press, Kuala Lumpur, 2006. [18] B. Clemens, “Economic Incentives and Small Firms: Does It Pay to Be Green?” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 59, No. 4, 2006, pp. 492-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.08.006 [19] S. Chromie, “Assessing Entrepreneurial Inclinations: Some Approaches and Empirical Evidence,” European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2000, pp. 7-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/135943200398030 [20] D. R. Cooper and P. S. Schindler, “Business Research Methods,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 2006. [21] G. Bosworth, “Education, Mobility and Rural Business Development,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2009, pp. 660-677. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14626000911000983 [22] M. Chapman, “When the Entrepreneur Sneezes, the Or- ganization Catches Cold: A Practitioner’s Perspective on the State of the Art in Research on the Entrepreneurial Personality and the Entrepreneurial Process,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2000, pp. 97-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/135943200398102 [23] V. Ratten and Y. Suseno, “Knowledge Development, So- cial Capital and Alliance Learning,” International Jour- nal of Educational Management, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2006, pp. 60-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513540610639594 [24] W. G. Rowe, “Creating Wealth in Organizations: The Role of Strategic Leadership,” Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2001, pp. 81-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AME.2001.4251395 [25] A. Tarabishy, G. Solomon, J. R. Fernald and M. Sashkin, “The Entrepreneurial Leader’s Impact on the Organi- zation’s Performance in Dynamic Markets,” Journal of Private Equity, Vol. 8, No. 4, 2005, pp. 20-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.3905/jpe.2005.580519 [26] G. Yukl, “Leadership in Organizations,” 3rd Edition, Prentice-Hall, New York, 2002. [27] J. Abor and N. Biekpe, “Corporate Governance, Owner- ship Structure and Performance of SMEs in Ghana: Im- plications for Financing Opportunities,” Corporate Gov- ernance, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2007, pp. 288-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14720700710756562 [28] G. Carmignani, “The Definition of a Standard to Imple- ment a Process Management System,” Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2009, pp. 395-349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14637150910960639 [29] D. A. Coelho and J. C. O. Matias, “Innovation in the Or- ganisation of Management Systems in Portuguese SMEs,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2010, pp. 324-329. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2010.031905 [30] C. Doom, K. Milis, S. Poelmans and E. Bloemen, “Criti- cal Success Factors for ERP Implementations in Belgian SMEs,” Journal of Enterprise Information Management, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2010, pp. 378-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17410391011036120 [31] T. Fuller and Y. Tian, “Social and Symbolic Capital and Responsible Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Investiga- tion of SME Narratives,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 67, No. 3, 2006, pp. 287-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9185-3 [32] A. Gilmore, D. Carson and K. Grant, “SME Marketing in Practice,” Journal of Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2001, pp. 6-11. [33] D. M. Hussey and P. D. Eagan, “Using Structural Equa- tion Modelling to Test Environmental Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturers: Can SEM Help SMEs?” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2007, pp. 303-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.12.002 [34] H. Jenkins, “Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 67, No. 3, 2006, pp. 241-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9182-6 [35] B. Jones, “Entrepreneurial Marketing and the Web 2.0 Interface,” Journal of Research in Marketing and Entre- preneurship, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2010, pp. 143-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14715201011090602 [36] J. A. G. Van Kleef and N. J. Roome, “Developing Capa- bilities and Competence for Sustainable Business Man- agement as Innovation: A Research Agenda,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2007, pp. 38-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.06.002 [37] R. T. Keller, “Transformational Leadership, Initiating Structure & Substitutes for Leadership: A Longitudinal Study of Research & Development Project Team Per- formance,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 91, No. 1, 2006, pp. 202-210. Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 82 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.202 [38] G. Qian, T. A. Khoury, M. W. Peng and Z. M. Qian, “The Performance Implications of Intra- and Inter-Regional Geographic Diversification,” Strategic Management Jour- nal, Vol. 31, No. 9, 2010, pp. 1018-1030. [39] M. A. Luke and G. R. Maio, “Oh the Humanity! Human- ity-Esteem and Its Social Importance,” Journal of Re- search in Personality, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2009, pp. 586-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.001 [40] A. Mehra, B. R. Smith, A. L. Dixon and B. Robertson, “Distributed Leadership in Teams: The Networks of Leadership Perceptions & Team Performance,” The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2006, pp. 232-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.003 [41] G. D. Meyer and K. A. Heppard, “Entrepreneurial Strate- gies: The Dominant Logic of Entrepreneurship,” Irwin University Books, New York, 2000. [42] A. Macpherson and R. Holt, “Knowledge, Learning and Small Firm Growth: A Systematic Review of the Evi- dence,” Research Policy, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2007, pp. 172- 192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.10.001 [43] N. O’Regan and A. Ghobadian, “Testing the Homogene- ity of SMEs: The Impact of Size on Managerial and Or- ganisational Processes,” European Business Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2004, pp. 64-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09555340410512411 [44] M. Kirchgeorg and M. I. Winn, “Sustainability Marketing for the Poorest of the Poor,” Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2006, pp. 171-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bse.523 [45] G. R. McGrath and I. C. Macmillan, “The Entrepreneurial mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportu- nity in an Age of Uncertainty,” Harvard Business School Press Books, Boston, 2000. [46] J. Lynn, “Business Process Automation: A Gateway to Better Business Management-Focus: BPM,” 2013. http://www.joanlynn.ulitzer.com [47] L. J. Mullins, “Management and Organizational Behav- iour, 8th edition,” Prentice Hall, New York, 2007. [48] M. O’Dwyer, A. Gilmore and D. Carson, “Innovative Marketing in SMEs,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 43, No. 1-2, 2009, pp. 46-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560910923238 [49] A. O’Donnell, “The Nature of Networking in Small Firms,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2004, pp. 206-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13522750410540218 [50] L. J. Porter and S. J. Tanner, “Assessing Business Excel- lence,” 2nd Edition, Heinemann, London, 2004. [51] H. Chen, A. Papazafeiropoulou and Y. K. Dwivedi, “Ma- turity of Supply Chain Integration within Small and Me- dium-Sized Enterprises: Lessons from the Taiwan IT Ma- nufacturing Sector,” International Journal of Manage- ment and Enterprise Development, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2010, pp. 325-347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJMED.2010.037562 [52] S. K. Chetty and L. M. Stangl, “Internationalization and Innovation in a Network Relationship Context,” Euro- pean Journal of Marketing, Vol. 44, No. 11-12, 2010, pp. 1725-1743. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090561011079855 [53] E. Bekele and Z. Worku, “Factors that Affect the Long Term Survival of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Ethiopia,” South African Journal of Economics, Vol. 76, No. 3, 2008, pp. 548-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2008.00207.x [54] W. R. Carroll and T. H. Wagar, “Is There a Relationship between Information Technology Adoption and Human Resource Management?” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2010, pp. 218- 229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14626001011041229 [55] J. Abor and K. Adjasi, “Corporate Governance and the Small and Medium Enterprise Sector: Theory and Impli- cation,” Corporate Governance, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2007, pp. 111-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14720700710739769 [56] M. B. Ingstrup, “The Role of Cluster Facilitators,” Inter- national Journal of Globalisation and Small Business, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2010, pp. 25-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJGSB.2010.035329 [57] R. Isaksson, “Total Quality Management for Sustainable Development: Process Based Systems Model,” Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. 5, 2006, pp. 632-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14637150610691046 [58] S. Jack, S. Moult, A. R. Anderson and S. Dodd, “An En- trepreneurial Network Evolving: Patterns of Change,” In- ternational Small Business Journal, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2010, pp. 315-337. [59] Y. I. Jiang and M. W. Peng, “Are Family Ownership and Control in Large Firms Good, Bad, or Irrelevant?” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2011, pp. 15-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10490-010-9228-2 [60] K. Jagoda, B. Maheshwari and R. Lonseth, “Key Issues in Managing Technology Transfer Projects: Experiences from a Canadian SME,” Management Decision, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2010, pp. 366-382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00251741011037747 [61] S. Jonsson and J. Lindbergh, “The Impact of Institutional Impediments and Information and Knowledge Exchange on SMEs’ Investments in International Business Relation- ships,” International Business Review, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2010, pp. 548-561. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.04.002 [62] E. M. Maine, D. M. Shapiro and A. R. Vining, “The Role of Clustering in the Growth of New Technology-Based firms,” Journal of Small Business Economics, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2010, pp. 127-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9104-3 [63] K. Kozovska, “The Role of Regional Clusters and Firm Size for Firm Efficiency,” International Journal of Glob- alisation and Small Business, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2010, pp. 41-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJGSB.2010.035330 [64] R. Malhotra and C. Temponi, “Critical Decisions for ERP Integration: Small Business Issues,” International Jour- nal of Information Management, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2010, pp. 28-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2009.03.001 Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU 83 [65] W. Zhu, I. K. H. Chew and W. D. Spangler, “CEO Transformational Leadership & Organizational Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Human-Capital-Enhancing Human Resource Management,” The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2005, pp. 39-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.06.001 [66] S. T. Foster, “Managing Quality: Integrating Supply Chain,” Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2007. [67] R. Harms, S. Kraus and C. H. Reschke, “Configurations of New Ventures in Entrepreneurship Research: Contribu- tions and Research Gaps,” Management Research News, Vol. 30, No. 9, 2007, pp. 661-673. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01409170710779971 [68] T. A. Judge and R. F. Piccolo, “Transformational & Tran- sactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Re- lative Validity,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 89, No. 5, 2004, pp. 755-768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755 [69] B. Dawson-Saunders and R. G. Trapp, “Basic Clinical Biostatistics,” 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York. [70] D. W. Hosmer and S. Lemeshow, “Applied Logistic Re- gression Analysis,” 2nd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York. [71] M. Cleves, W. Gould and R. Guitierrez, “An Introduction to Panel Data Analysis Using STATA,” Revised Edition, STATA Press, College Station. [72] D. Kleinbaum, “Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Tex t,” Springer-Verlag, New York. [73] M. Verbeek, “A Guide to Modern Econometrics,” John Wiley and Sons, New York, 2000. [74] S. Globerman, M. W. Peng and M. S. Daniel, “Corporate Governance and Asian Companies,” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2011, pp. 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10490-010-9240-6 [75] D. Zoogah, R. Vora, O. Richard and M. W. Peng, “Stra- tegic Alliance Team Diversity, Coordination, and Effec- tiveness,” International Journal of Human Resource Ma- nagement, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2011, pp. 510-529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.543629 [76] M. W. Peng, S. B. Rabi and C. Sea-Jin, “Asia and Global Business,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2010, pp. 373-376. [77] S. Daley-Harris, “Microcredit Campaign Strategies and Social Business Movement: What Can the Social Busi- ness Movement Learn from the Early Promotion of Mi- crocredit?” The Journal of Social Business, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2011, pp. 46-61. [78] M. Kumar, J. Antony, C. N. Madu, D. C. Mongomery and S. H. Park, “Common My ths of Six Sigma Demystified,” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Manage- ment, Vol. 25, No. 8, 2008, pp. 878-895. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02656710810898658 [79] L. Klotz, M. Horman, H. H. Bi and J. Bechtel, “The Im- pact of Process Mapping on Transparency,” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Vol. 57, No. 8, 2008, pp. 623-636. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17410400810916053 [80] S. Dasanayaka and G. D. Sardana, “Development of SMEs Through Clusters: A Comparative Study of India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka,” World Review of Entrepreneur- ship, Management and Sustainable Development, Vol. 6, No. 1-2, 2010, pp. 50-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2010.031638 [81] P. Edwards, S. Sengupta and C. J. Tsai, “The Context- Dependent Nature of Small Firms’ Relations with Sup- port Agencies: A Three-Sector Study in the UK,” Interna- tional Small Business Journal, Vol. 28, No. 6, 2010, pp. 543-565. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266242610375769 [82] L. Dougherty, “Putting Poverty in Museums: Strategies to Encourage the Creation of the For-Profit Social Busi- ness,” Boston College Third World Law Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2009, pp. 357-380. [83] R. P. Estebanez, E. U. Grande and C. M. Colomina, “In- formation Technology Implementation: Evidence in Spanish SMEs,” International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2010, pp. 39-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/18347641011023270 [84] G. A. Rummler and A. P. Brache, “Business Process Management in US Firms Today,” 2013. http://rummler-brache.com [85] H. Smith and P. Fingar, “Business Process Management, the Third Wave: The Breakthrough That Redefines Com- petitive Advantage for the Next Fifty Years,” Meghan- Kiffer Press, New York, 2006. [86] J. Zhang, “The Problems of Using Social Networks in En- trepreneurial Resource Acquisition,” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2010, pp. 338- 361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266242610363524 [87] K. Wennberg and G. Lindqvist, “The Effect of Clusters on the Survival and Performance of New Firms,” Small Business Economics, Vol. 34, No. 3, 2010, pp. 221-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9123-0 [88] C. M. Van Praag, “Business Survival and Success of Young Small Business Owners,” Brunel Business School, Lon- don, 2003. [89] C. H. Sun and K. E. Liu, “Information Asymmetry and Small Business in Online Auction Market,” Small Busi- ness Economics, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2010, pp. 433-444. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9160-8 [90] B. J. Hicks, S. J. Culley, C. A. McMahon and P. Powell, “Understanding Information Systems Infrastructure in Engineering SMEs: A Case Study,” Journal of Engineer- ing and Technology Management, Vol. 27, No. 1-2, 2010, pp. 52-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2010.03.004 [91] E. B. Wagner, “Small Business Survival Relies on Grit, Perseverance,” American City Business Journals, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2003, pp. 1-2. [92] A. Dowla, “In Credit We Trust: Building Social Capital by Grameen Bank in Bangladesh,” Journal of Socio Eco- nomics, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2006, pp. 102-122. [93] L. Harris and A. Rae, “The Online Connection: Trans- forming Marketing Strategy for Small Businesses,” Jour- nal of Business Strategy, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2010, pp. 4-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02756661011025017 [94] P. Hadaya and R. Pellerin, “Determinants and Perform- Open Access JDAIP  Z. WORKU Open Access JDAIP 84 ance Outcome of Manufacturing SMEs Use of Inter- net-Based IOISs to Share Inventory Information,” Inter- national Journal of Electronic Business, Vol. 8, No. 6, 2010, pp. 477-504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJEB.2010.037131 [95] R. McAdam, S. Moffett, S. A. Hazlett and M. Shevlin, “Developing a Model of Innovation Implementation for UK SMEs: A Path Analysis and Explanatory Case Analy- sis,” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2010, pp. 195-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266242609360610 [96] J. Curran and R. A. Blackburn, “Researching the Small Enterprise,” Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2001. [97] A. Smedlund, “The Knowledge System of a Firm: Social Capital for Explicit, Tacit and Potential Knowledge,” Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2008, pp. 63-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13673270810852395