Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

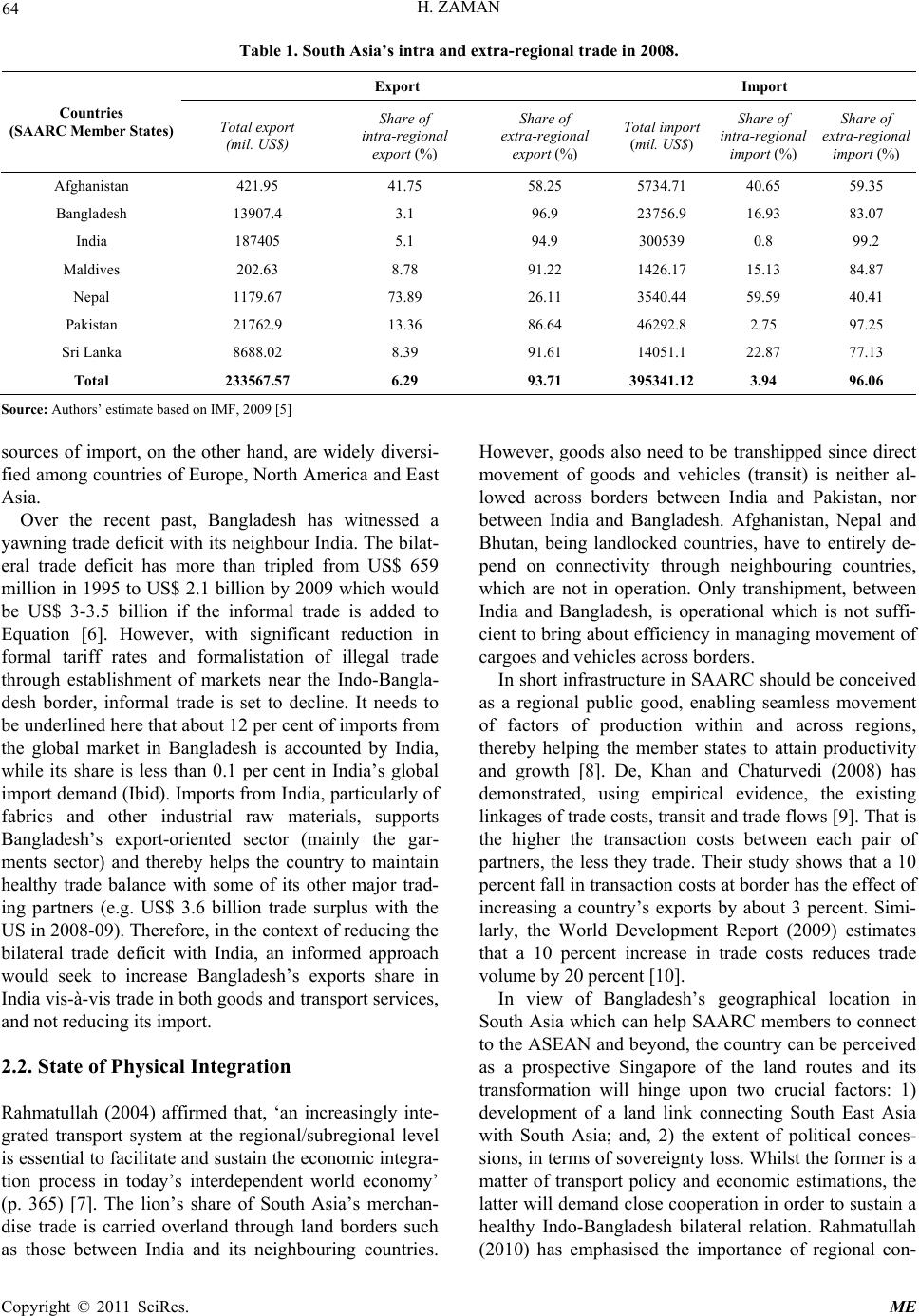

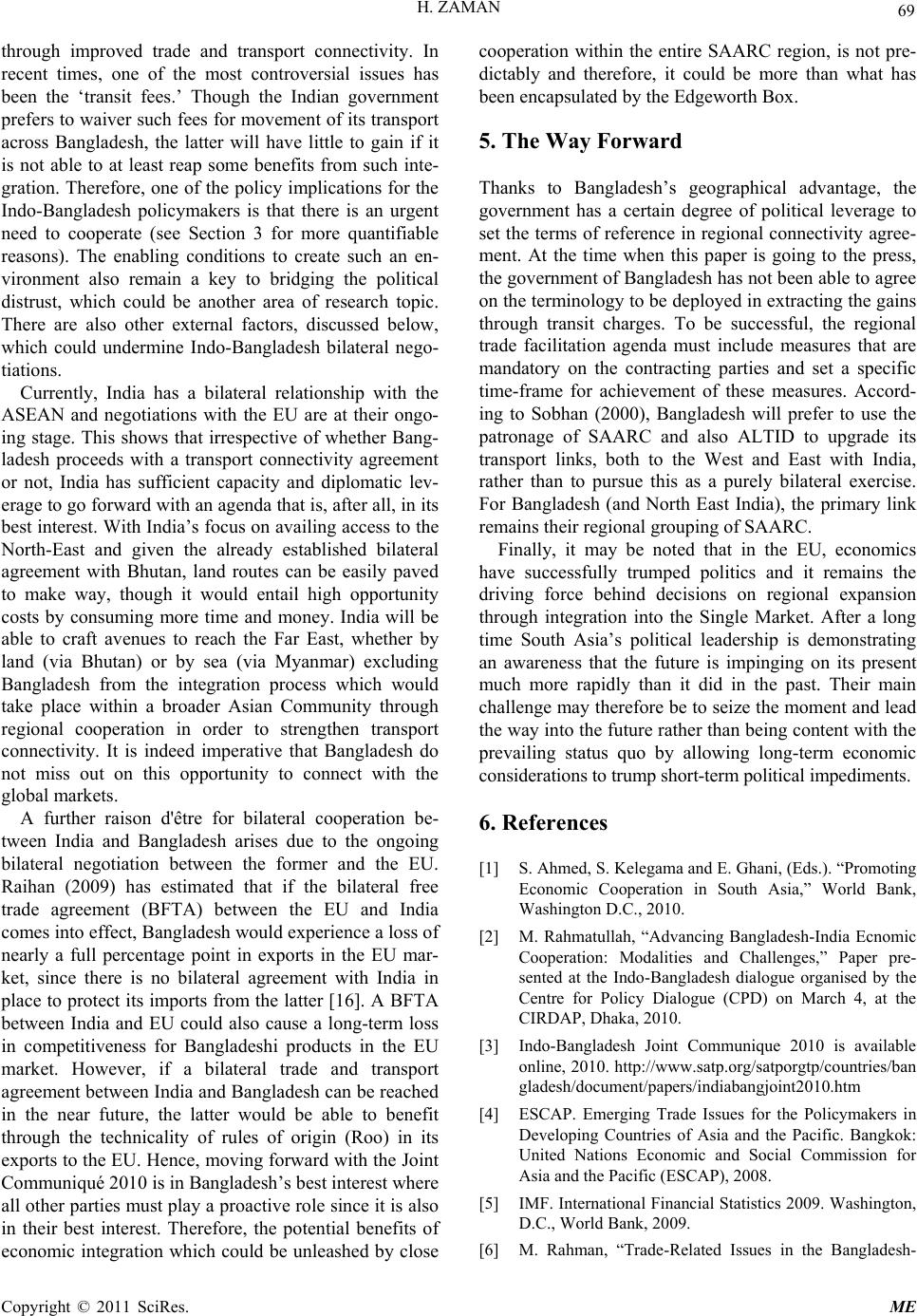

Modern Economy, 2011, 2, 62-70 doi:10.4236/me.2011.21010 Published Online February 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/me) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME An Edgeworth Box Approach toward Conceptualising Economic Integration Hasanuzzaman Zaman Centre for Policy Dialogue, Dhaka, Bangladesh E-mail: zaman.h1984@gmail.com Received December 2, 2010; revised January 11, 2010; accepted January 14 , 2011 Abstract The joint-communiqué originating from the January 2010 summit between India and Bangladesh has opened new doors of opportunities for addressing economic integration not just between India and Bangladesh, but across the South Asian region. In this article, an Edgeworth Box approach has been deployed to help con- ceptualise the various Pareto-optimal solutions that are to be realised through close bilateral cooperation in particular. The article attempts to address some of the issues deterring establishment of trade and transport integration between Bangladesh and India, which are also relevant from the perspective of the entire South Asia region. Keywords: Economic Integration, Game Theory, Edgeworth Box, Cooperation, Trade, Transport, Connectivity 1. Introduction South Asia is considered to be on e of the least integrated regions in the world today [1]. Though the region inher- ited an integrated transport system from the British, this was fragmented not only by the partition of India in 1947 but also by its political aftermath . South Asia now needs to be re-integrated within the context of greater political harmony as it has entered into the second era of South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). However, due to lack of integration of the transport sys- tem in South Asia, logistic costs are high and ranges be- tween 13–14.0 per cent of GDP, compared to 8.0 per cent in USA [2]. Intr a-regional trade among the SAARC member states was only US$ 14.7 billion in 2008 or around 6.3 per cent of their total global trade, compared to 60.0 per cent in NAFTA and 26.0 per cent in the ASEAN region. In order to augment trade flows within SAARC, integration of the transport network in South Asia is, therefore, crucial for landlocked countries such as Nepal and Bhutan and regions such as North-East In- dia which shares 98.0 percent of its border with Bangla- desh and only 2.0 percent of its bord er with the mainland India. This is also especially imperative from the per- spective of Nepal since it holds the highest share of in- tra-industry trade within the SAARC community. The joint-communiqué originating from the January 2010 summit between India and Bangladesh is a key to unlock the potential that a unified South Asian market could offer to its members [3]. It is also evident that the communiqué has opened new doors of opportunities for improving trade and transport relations, not just between India and Bangladesh, but across the South Asian region. This is critically important for stimulating the SAARC regional integration process. The summit declaration offered the North-East Indian states access to Chittagong port and, West Bengal access to Mongla port in South- West Bangladesh. In turn, India has agreed to provide unrestricted transit to Nepal an d Bhutan not just for their bilateral trade with Bangladesh but to use its ports for third country trade. These agreements will need, in due course, to be operationalised for initiating economic in- tegration not just between India and Bangladesh, but across South Asia. It is in the aforesaid context that this paper makes an attempt to theorise South Asia’s regional cooperation agenda by focusing on the two key actors, India and Bangladesh, which possess substantial comparative ad- vantage with regards to their export basket and geo- graphical location respectively. Suffice to mention that in view of Bangladesh’s geo-strategic advantage as a result of its location and India’s important role as a source of import for the region’s other countries, we will closely examine the Indo-Bangladesh bilateral relationship since  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 63 it has wider implications from the regional integration perspective. 1.1. Objectives and Methodology The overarching objective is to contribute towards theo- retical knowledge on economic integration by using em- pirical evidence to support the case of close cooperation. The paper’s point of departure is based on the premise that bilateral non-cooperation is undermining the physi- cal integration of South Asia and deterring the efforts of establishing a single market in the SAARC reg ion. The researchers consulted two key resource persons, Dr. M. Rahmatullah, Former UNESCAP Director and currently (2010), Policy Adviser for Transport Sector Management Reform of the Planning Commission, Gov- ernment of Bangladesh, and Professor Mustafizur Rah- man, Executive Director, Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), in order to elicit latest information in the context of transport and trade respectively. Relevant literature dealing with trade facilitation measures was reviewed to better understand the interplay of different institutional and market forces influencing the economic integration process in the SAARC region. Using secondary sources of information such as recent studies that have been car- ried out on the economic integration topic by renowned economists and researchers, we have argued that bilateral cooperation can help to operationalise the SAARC re- gional integration agenda as envisaged in its mandate – creation of a single market in the region. This article deploys a game theoretic approach to help conceptualise the various possible strategies that partner countries may consider in arriving at their Pareto-opti mal solutions, and thereby improve their prevailing status quo in terms of their trade and transport relations. The explanation derived from the game theory has been ex- tended by the Edgeworth Box to put it in the wider con- text of bilateral/regional cooperation. 1.2. Layout of the Paper The paper is organised into four sections. The following section provides a brief literature review relevant to the topic of this paper given the already large volume of work that been done on this discipline. Section 2 has been prepared in a manner that helps to set the tone of the present paper, i.e., non-cooperation, at bilateral and regional level is no longer a viable option for countries in South Asia, especially for Bangladesh. Section 3 identi- fies key issues undermining regional cooperation and also discusses the provisions relating to South Asia’s economic integration process as stipulated in the Indo Bangladesh Joint Communiqué 2010. Section 4 then substantiates on the discussion and presents the concep- tual framework to highlight the theoretical underpinnings of bilateral and regional cooperation. Section 5 con- cludes. 2. Cooperation and Economic Integration 2.1. State of Trade Integration As is known in economics, there are five stages of eco- nomic integration: a) preferential trade area; b) free trade area; c) customs union; d) free market; and, e) economic union. The SAARC region is on stage 2 of the economic integration process and as a result of the high export similarity, the scope for intra-South Asia export has been narrowed down. India records the highest export similar- ity index which reduces its neighbouring countries’ op- portunities to explore its large market [4]. Inevitably, export similarity is also reflected in the similar kinds of tariff structures in South Asia which have also choked the scope of intra-industry trade between the SAARC member states. South Asia remains far behind most other regions in terms of share of overall trade. Extra-regional trade dominates South Asia’s overall trade structure account- ing for 93.7 per cent of the region’s total export and 96.1 per cent of import (Table 1). The share of intra-regional export for any country is calculated by taking its total export to a region (SAARC in this case), divided by its total exports which is then multiplied by 100 . In estimat- ing the share of extra-regional export, since we already calculated the intra-regional export, the remainder ac- counts for the share of exports earnings generated from the global market. The similar methods are used to cal- culate the share of intra-regional and extra-regional im- port. Although small economies such as Afghanistan and Nepal maintain relatively high er level of trade within the region, overall trade is skewed due to low level of in- tra-regional trade of large economies like India and Paki- stan. Most of region’s export is destined to developed countries: European countries accounted for 23 per cent of region’s export while the US for 16 per cent during 2008. However, the share of export to these two regions registered a decline over time (from 53 per cent in 2000 to 39 percent in 2008) while export to other regions has considerably increased. Leading export destinations of the region such as Europe and North America involve large markets, offer diversified export opportunities and provide preferential market access for LDCs of the region. India, and in some cases, Pakistan are two of the major export destinations for Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka mainly because of geographical proximity, common borders and bilateral partnership/trading agreements. The region’s  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 64 Table 1. South Asia’s intra and extra-regional trade in 2008. Export Import Countries (SAARC Member States) Total export (mil. US$) Share of intra-regional export (%) Share of extra-regional export (%) Total import (mil. US$) Share of intra-regional import (%) Share of extra-regional import (%) Afghanistan 421.95 41.75 58.25 5734.71 40.65 59.35 Bangladesh 13907.4 3.1 96.9 23756.9 16.93 83.07 India 187405 5.1 94.9 300539 0.8 99.2 Maldives 202.63 8.78 91.22 1426.17 15.13 84.87 Nepal 1179.67 73.89 26.11 3540.44 59.59 40.41 Pakistan 21762.9 13.36 86.64 46292.8 2.75 97.25 Sri Lanka 8688.02 8.39 91.61 14051.1 22.87 77.13 Total 233567.57 6.29 93.71 395341.12 3.94 96.06 Source: Authors’ estimate ba sed on IMF, 2009 [5] sources of import, on the other hand, are widely diversi- fied among countries of Europe, North America and East Asia. Over the recent past, Bangladesh has witnessed a yawning trade deficit with its neighbou r India. The bilat- eral trade deficit has more than tripled from US$ 659 million in 1995 to US$ 2.1 billion by 2009 wh ich would be US$ 3-3.5 billion if the informal trade is added to Equation [6]. However, with significant reduction in formal tariff rates and formalistation of illegal trade through establishment of markets near the Indo-Bangla- desh border, informal trade is set to decline. It needs to be underlined here that about 12 per cent of imports from the global market in Bangladesh is accounted by India, while its share is less than 0.1 per cent in India’s global import demand (Ibid). Imports from India, particularly of fabrics and other industrial raw materials, supports Bangladesh’s export-oriented sector (mainly the gar- ments sector) and thereby helps the country to maintain healthy trade balance with some of its other major trad- ing partners (e.g. US$ 3.6 billion trade surplus with the US in 2008-09). Th eref ore, in the contex t of reducing the bilateral trade deficit with India, an informed approach would seek to increase Bangladesh’s exports share in India vis-à-v is trade in both good s and transp ort services, and not reducing its import. 2.2. State of Physical Integration Rahmatullah (2004) affirmed that, ‘an increasingly inte- grated transport system at the regional/subregional level is essential to facilitate and sustain th e economic integra- tion process in today’s interdependent world economy’ (p. 365) [7]. The lion’s share of South Asia’s merchan- dise trade is carried overland through land borders such as those between India and its neighbouring countries. However, goods also need to be transhipped since direct movement of goods and vehicles (transit) is neither al- lowed across borders between India and Pakistan, nor between India and Bangladesh. Afghanistan, Nepal and Bhutan, being landlocked countries, have to entirely de- pend on connectivity through neighbouring countries, which are not in operation. Only transhipment, between India and Bangladesh, is operational which is not suffi- cient to bring about efficiency in managing movement of cargoes and vehicles across borders. In short infrastructur e in SAARC should be conceived as a regional public good, enabling seamless movement of factors of production within and across regions, thereby helping the member states to attain productivity and growth [8]. De, Khan and Chaturvedi (2008) has demonstrated, using empirical evidence, the existing linkages of trade costs, transit and trade flows [9]. That is the higher the transaction costs between each pair of partners, the less they trade. Their study shows that a 10 percent fall in transaction costs at border has the effect of increasing a country’s exports by about 3 percent. Simi- larly, the World Development Report (2009) estimates that a 10 percent increase in trade costs reduces trade volume by 20 percent [10]. In view of Bangladesh’s geographical location in South Asia which can help SAARC members to connect to the ASEAN and beyond, the co untry can be perceived as a prospective Singapore of the land routes and its transformation will hinge upon two crucial factors: 1) development of a land link connecting South East Asia with South Asia; and, 2) the extent of political conces- sions, in terms of sovereignty loss. Whilst the former is a matter of transport policy and economic estimations, the latter will demand close cooperatio n in order to sustain a healthy Indo-Bangladesh bilateral relation. Rahmatullah (2010) has emphasised the importance of regional con-  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 65 nectivity in South Asia and the potential gains that a transit agreement could accrue to both India and Bang- ladesh and for the region in general. 3. Urgency for Regional Cooperation 3.1. Costs of Non-Cooperation De (2009b) demonstrates that there is a positive and di- rect relationship between infrastructure stock and per capita income in South Asia, which has grown over time: a 1 percent increase in the stock of infrastructure has been associated with a 1 percent increase in per capita income in South Asia [11]. On the other hand, rising inequality in infrastructure stock has also been responsi- ble for widening the inequality gap in South Asia. In such a backdrop, the urgency for cooperation in order to promote a strong growth process need not be overstated. According to Sobhan (2000), physical integration of the marginalised countries in South Asia into the global system with more dynamic adjacent regions (through trade facilitation measures), will cumulate to much more than the sum of its parts and such close cooperation can be expected to unleash certain economic synergies, which could have a transformatory impact on the fortunes of these countries linked by the transport network [12]. This hypothesis has been quantified by Wilson and Ostuki (2007) who estimate that if South Asia and the rest of the world were to raise their levels of trade facilitation half- way to the East Asian average, the gains to the region would be US$ 36 billion [13]. Out of these gains, about 87 per cent would be generated from South Asia’s own efforts (leaving the rest of the world unchanged). In overall terms, regional expansion of trade in South Asia can be substantially developed with concrete programmes of action to address barriers to economic integration. It needs to be recalled here that as an integral part of the Asian Highway Network and Trans Asian Railway development, intermodal interfaces has been proposed at vantage locations to serve industrial and other clusters, and centres to facilitate seamless movement of goods and services across borders. However, in order to make ef- fective utilisation of these routes through intermodal transport connectivity, relevant government authorities need to put a concerted effort in reducing the high trans- action costs associated with the movement of vehicles and cargoes. ADB (2008) summarises some of the key issues pertaining to the lack of physical, industrial and communication infrastructure impeding growth in South Asia [14]. Air and maritime ports are ranked as less competitive in South Asia as compared to East Asia. While it takes 2 hours to clear a vessel in Singapore and Laem Chabang, Thailand, it takes to 2-3 days in Chit- tagong (Ibid). At Delhi airport average cargo dwell time is 2.5 days. Furthermore, a journey of 34 days by land- come-sea routes could be performed within 9-10 days if appropriate policies and infrastructure are put in place [15]. The cost of transport for one 20 foot loaded con- tainer from Delhi ICD to Dhaka is US$ 2,500 which comes down US$ 1,900 if the shipping route is via Mumbai, Kolkata and then Chittagong instead of the Mumbai, Singapore and then Chittag ong (Ibid). 3.2. Indo-Bangladesh Joint Communiqué 2010 It needs to be recalled here that the government of India, in the Joint Communiqué 2010, has committed to pro- vide Bangladesh with US$ 1 billion credit for a range of projects which include development of railway infra- structure, increasing supply of locomotives and passen- ger coaches. Bangladesh and India have already allowed transit to each other for bilateral traffic and it will be in Bangladesh’s interest to resolve connectivity issue sub- regionally, by providing connectivity to all the 3-land- locked countries/territory at a time (Nepal, Bhutan and North-East India). Since heavy Indian trucks cannot en- ter Bangladesh as a result of its highways’ physical weakness, it has been suggested that inter-district Bang- ladeshi truckers could provide logistic support to carry goods using multi-axle vehicles and/or truck-trailers to carry containers. The government of Bangladesh has agreed to allow use of Mongla Port by Nepal, Bhutan and India, and at present, it is estimated that the port has 80 percent spare capacity (Rahmatullah, 2010). Nepal and Bhutan are using the already congested Kolkata port and the use of Mongla Port could help to ease traffic flows between the Indo-Bangladesh which will enable Bangladesh to trade in transport services, and earn port charges, rail charges, road transport charges, and transit fee. Also, the govern- ment has permitted the use of Chittagong Port by the North-East Indian States, which has 40 percent spare capacity at present level of management efficiency (Ibid). In recent times, November 2010, a British firm, Port Evo, has offered US$ 800 million investment proposal for developing the Mongla port under Public-Private Part- nership (PPP). Indeed, development of Mongla port will play a significant role in promoting trade and commerce as Bhutan and Nepal will use this port when transit fa- cilities will be launched. Notwithstanding the many positive interventions by both Bangladesh and India, until expressways can be built, railway is the preferred mode of transport for moving goods across Bangladesh (and also India). The Indo-Bangladesh Joint Communiqué 2010 envisages establishment of two rail links: a) Birgunj-Rauzal-Kathi-  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 66 har-Rohanpur-Khulna (connecting Nepal and Bangla- desh via India); and, b) Akhaura-Agartala (connecting North-East India with Ban gladesh). In case of the former, though transhipment facility for containers/cargo at Khulna will be carried forward by truck (38 km to Mon- gla Port), it would greatly assist Mongla port to remain competitive with Kolkata port in terms of managing ex- port-import traffic. Overall, the Khulna-Mongla project can play a bridging role in providing greater access to Mongla Port for goods coming from or going to Nepal. The Akhaura-Agartala rail link will be strategic in the near future in connecting North-East India with its mainland (via Bangladesh). Finally, it is imperative to examine the Inland Water Transport (IWT) related provisions in the IBJC 2010 which stipulated ‘Ashug anj in Bangladesh and Silghat in India shall be declared ports of call. The IWTT Protocol shall be amended through exchange of letters. A joint team will assess the improvement of infrastructure and the cost for one-time or longer term transportation of ODCs (Over Dimensional Cargo) from Ashuganj’ (para 22). IWT is the cheapest mode of transportation and prevails only between India and Bangladesh; however, due to poor implementation and underutilisation of the facilities, between 1995 and 2002, the goods transported were slightly more than a hundred thou sand metric ton s a year (Sikri, 2009). India is expected to provide invest- ment in Ashuganj port development where Bangladesh will have the scope to earn considerable foreign ex- change through IWT charges, port charges, road trans- port chares and transit fees, which will need to be nego- tiated ex-ante and specified in the agreements. Having highlighted the high costs of non-cooperation, in the following section, the status of regional and bilat- eral (Indo-Bangladesh) cooperation has been conceptu- alised in terms of their trade and transport relations, two key factors responsible for facilitating region al economic integration. 4. Theorising Bilateral and Regional Cooperation 4.1. Background There is no doubt that much empirical work has been done on the topic of regional cooperation and economic integration. However, few have attempted to deploy a theory which could help provide a conceptual framework to better comprehend the complex nature of cooperation in the SAARC context. In this section, the paper’s point of departure, i.e., bilateral non-cooperation is no longer a viable option, is conceptualised using two frameworks - the game theory and Edgeworth Box. Both the frame- works are deployed in order to help conceptualise the urgency and scope for regional and Indo-Bangladesh cooperation, reflecting the prevailing status quo in terms of their export and transport relations (which have been discussed in the previous section). As maybe recalled, India has its interest to utilise Bangladesh’s geographical advantage to connect to its North-East region, comprising the seven sisters and be- yond to the ASEAN region; on the other hand, Bangla- desh is keen to reduce the ever growing bilateral trade deficit with India through increasing its exports (both in goods and transport services). Inev itably, development in the bilateral status quo between India and Bangladesh will carry unpredictable consequences for regional inte- gration but since the paper conceives the Indo-Bangla- desh Joint Communiqué 2010 as the key to catalyse the SAARC regional integration process, we will initially focus on these two co untries’ agendas and later extend it to the wider region. 4.2. Game Theory Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics which attempts to capture the behaviour of agents in strategic situations, in which an individual’s success in making the right choice is directly dependent on the others’ prefer- ences. In equilibrium, each player of the game adopts a strategy that they prefer the most. Two key equilibrium concepts have been developed (the Nash equilibriu m and Prisoner’s Dilemma) in an attempt to decipher the deci- sion-making process of agents in strategic situations which are often conflictin g in nature. The game theory is applied from the perspective of SAARC regional and Indo-Bangladesh cooperation in two ways – 1) where countries/member states know the equilibrium strate- gies of the other players (Nash Equilibrium); and, 2) where one country faces difficulties in comprehending the others’ strategies (Prisoner’s Dilemma). In the following table, we have illustrated the urgency for cooperation under both the assumptions and in doing so, we have identified two dominant strategies. To keep matters coherent, let us start with the bilateral coopera- tion case. India and Bangladesh have to take part in a cooperation game with an example payoff matrix shown in Table 2. It is to be mentioned here that the numbers have been established arbitrarily in view of the logic that non-cooperation carries high costs for both Bangla- desh and India. Table 2. Nash equilibrium and prisoner’s dilemma. India Cooperate (A) Defect (B) Cooperate (A)100, 100 0, 50 Bangladesh Defect (B ) 50, 0 0, 0  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 67 In other words, if India cooperates, Bangladesh will be able to increase its export earnings through trade in both goods and transport services. On the other hand, India will defect when Bangladesh is not keen to let it connect with its seven sisters. Similarly, Bangladesh’s coopera- tion will imply that it is willing to br idge mainland India with its North-East region. If, however, India is not ready to provide means by which Bangladesh could reduce its bilateral trade deficit, the latter will defect. In the back- drop of the prevailing high costs of non-cooperation, which have been discussed in the previous Section 2, the players should cooperate, both adopting strategy A to receive the highest payoff, i.e., 100 (dominant strategy 1). If both players chose strategy B though, there is still a Nash equilibrium, although each player is awarded less than optimal payoff. If India decides to cooperate and Bangladesh defects (strategies A and B respectively), the pay-off would be lower than what would have been real- ised through und er cooperation. Thus, Nash equilibrium occurs when both parties ei- ther cooperate or defect and no agent can benefit by changing only his or her own strategy unilaterally. However, when information asymmetry prevails (e.g. absence of technical details, political uncertainty, etc), both parties can enter into a prisoner’s dilemma (PD) situation. In such cases, where countries are not aware of each other’s strategies, both will be inclined to defect and adopt strategy B with a zero payoff (dominant strat- egy 2). The paradox is that both states are acting ration- ally, but producing an evidently irrational result. There- fore, in case of India and Bangladesh, governments and concerned policymakers will need to play a strategic role in bridging the information gap an d political uncertainty. To put it in the regional framework, we could simply replace Bangladesh as SAARC. Given India’s growing role in the international arena, if all member states of SAARC are willing to cooperate, India should also fol- low the same sui t and max imi se the pay-off (strategy A). On other hand, if India is not willing to cooperate, all other member states will also defect since the gains real- ised under strategy A is significantly less than what would be generated by adopting strategy B. Therefore, given India’s increasing leadership in global relations, it has to take the lead role by prioritising regional interests. 4.3. Edgeworth Box Analysis In economics, an Edgeworth box is used to represent distribution of different resources. It is used frequently in general equilibrium theory and can aid in finding the competitive equilibrium of a simple system. It is a useful tool to help con ceptualise the scop e for both region al and Indo-Bangladesh cooperation using a set of preference (indifference) curves where the competitive equilibrium may take place. It brings together two agents and two factors (trade and transport in this case) in a 2 × 2 dia- gram, depicting areas where Pareto improvement can take place. Ceteris paribus, i.e., assuming all other things remain the same, the theory makes the following three assumptions: a) The indifference (preference) curves are non-iden- tical, i.e., India wants to expand its transpo rt connectivity outreach to the North-East and beyond, while Bangla- desh and other South Asian countries want to reduce their bilateral trade deficit with India. b) No increasing returns, i.e., a zero-sum gum whereby all players stand to gain or lose. c) No asymmetry information, i.e., zero transaction costs implying that parties are well-informed about their strategic decisions. These assumptions allow a researcher to get on with the task of putting the regional cooperation and Indo- Bangladesh relations in a conceptual framework. The last two assumptions inherits the Nash Equilibriu m prin ciples where with zero transaction costs, countries can reach a mutually beneficial situation (a Pareto optimal equilib- rium). All these three assumptions offer a first-best world scenario which can then be used to understand the real world scenario, and subsequently explore second best alternatives. To illustrate this first-best world scenario, let us start with the Indo-Bangladesh bilateral relations. Figure 1 presents two countries India (OA) and Bangladesh (OB) initially faced with the status quo at w, with indifference curves UA0 and UB0. This situation is self-explanatory in terms of theory – an institutional market failure (non-Par eto optimal) wher e both countr ies stand to bene- fit through Pareto improvement from bilateral coopera- tion. The endowment consists of two factors – bilateral transport connectivity (y-axis) and bilateral volume of Y X B ’’ X B’ X B O B XC U A 3 F Y A ’’ Y B ’’ U A O Y A W Y B U B O U B 3 U B 2 C O A X A’’ X A’ X A X Y U B 1 U A 2 E Y A’ Y B ’ U A 1 Figure 1. Edgeworth box analysis.  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 68 export (x-axis), comprising both goods and services be- tween the two neighbours. In the graph, the variables represent the state of trade and transport connectivity in the Indo-Bangladesh rela- tions. Specifically, the endowment factor can be concep- tualised as the following - XA = India’s current trade level to Bangladesh, where it is a dominant export player. XB = Bangladesh’s current trade level to India, where it is a dominant import player. YA = India’s geographical disadvantage to connect with its seven sisters and beyond. YB = Bangladesh’s position to connect with India’s seven sisters and beyond. In terms of numbers, XA and XB represent the current bilateral trade deficit that Bangladesh is facing today with India (US$ 2.1 billion in formal terms). YA and YB are unique from the perspective of transport connectivity. In other words, given that mainland India shares 2 per cent of its border with North-East India, YA represents its inability to transport goods since North-East India shares 98 percent of its border with Bangladesh. It is theoretically affirmative that there is much scope for Pareto improvement, in other words, both countries can make each other better off without causing harm to either through close cooperation, assuming there are no transaction costs (e.g. lack of political will). In the best-world scenario, if Bangladesh were to remove its border restrictions for movement of cargoes and vehicles and allow India to connect with its North-East (moving from YA to YA’), perhaps mainland India would be also willing to allow Bangladesh to export more to its market. XB’ is the new level of Bangladesh’s exports with India, implying that its imports from India would reduce to XA’. In this scenario, both Bangladesh and India would have negotiated with each other to the extent that India would allow more exports from Bangladesh, whilst the latter will have granted transport connectivity facilities for India’s cargoes and other modes of transport. However, as may be recalled, Bangladesh’s interest would not be to reduce import from India (which would directly under- mine the development of its industrial sector), but instead, focus should be made on increasing export earnings through trade in tran sport services. This trend of bargaining for ‘more trade for more connectivity’ could continue further to reach XA’’ and XB’’ where both the countries would still be better off without causing any harm to each other. This is also relevant from the transport perspective since at YA’ India can be said to have connected with its seven sisters, while Bangladesh’s border exists physically at YB” , it ha s become virtually ineffective due to its augmentation of exports to the Indian market XA’’. Let us focus on point E and assume that it represents the Pareto-optimal equilibrium, with UA1 and UB1 as the countries’ new preference curves. In the best world sce- nario it reflects that Bangladesh and India can improve their bilateral status quo in terms of their trade and transport relations through close cooperation, but once they reach equilibrium, it would be difficult for the countries to make each other better off unilaterally, without eroding the other party’s interests. It is to be noted that any movement from w to E or any other point on the CC (contract-curve) can be considered a Pareto improvement. Assuming OA as India and OB to represent all other SAARC member states, the above discussion on bilateral relations can be directly applied in the regional coopera- tion context. Put simply, if India is willing to allow SAARC countries to increase their export in its market, India will also gain by transport connectivity which will aid it to reach its seven sisters and beyond in the East, and to Central Asia, Middle East and Europ e in the W est. Conversely, if the member states of SAARC are willing to let India use their territories to con nect with the global market, India should also cooperate by letting in more export from these countries. Thus, at least in theory, the CC remains identical for regional integration as also for bilateral cooperation. The emergence of a South Asian community would be greatly accelerated if its govern- ments and particularly the government of India were to commit themselves to invest their political and diplo- matic resources in advancing the process of integration. In supporting such initiatives India would need to move beyond the bilateralism which has been favoured by its bureaucracies to seek solutions within a broader South Asian community. 4.4. Theoretical Shortcomings Both the above discussed theories, in their static form, have attempted to illustrate the urgency and scope for cooperation. The game theory is a version of a ‘tit-for- tat’ or ‘give and take’ game and it is only designed to provide a framework to recognise when countries are likely to cooperate with each other. Similarly, in assum- ing zero transaction costs, the Edgeworth theory reflects a Nash Equilibrium situation to the extent that both countries are informed about each other’s strategies. Nevertheless, if we allow for some dynamics to take place, all such propositions, inevitably, will be rendered irrelevant. If India is not willing to allow more exports from Bangladesh and other countries to enter its market whereby the latter may not be too keen on granting con- nectivity, both countries can look for alternative options to move their respective agendas forward. What this best-world scenario reveals that there is am- ple of scope for improving the Indo-Bangladesh relations  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 69 through improved trade and transport connectivity. In recent times, one of the most controversial issues has been the ‘transit fees.’ Though the Indian government prefers to waiver such fees for movement of its transport across Bangladesh, the latter will have little to gain if it is not able to at least reap some benefits from such inte- gration. Therefore, one of the policy implications for the Indo-Bangladesh policymakers is that there is an urgent need to cooperate (see Section 3 for more quantifiable reasons). The enabling conditions to create such an en- vironment also remain a key to bridging the political distrust, which could be another area of research topic. There are also other external factors, discussed below, which could undermine Indo-Bangladesh bilateral nego- tiations. Currently, India has a bilateral relationship with the ASEAN and negotiations with the EU are at their ongo- ing stage. This shows that irrespective of whether Bang- ladesh proceeds with a transport connectivity agreement or not, India has sufficient capacity and diplomatic lev- erage to go forward with an agenda that is, after all, in its best interest. With India’s focus on availing access to the North-East and given the already established bilateral agreement with Bhutan, land routes can be easily paved to make way, though it would entail high opportunity costs by consuming more time and money. India will be able to craft avenues to reach the Far East, whether by land (via Bhutan) or by sea (via Myanmar) excluding Bangladesh from the integration process which would take place within a broader Asian Community through regional cooperation in order to strengthen transport connectivity. It is indeed imperative that Bangladesh do not miss out on this opportunity to connect with the global markets. A further raison d'être for bilateral cooperation be- tween India and Bangladesh arises due to the ongoing bilateral negotiation between the former and the EU. Raihan (2009) has estimated that if the bilateral free trade agreement (BFTA) between the EU and India comes into effect, Bangladesh would experience a loss of nearly a full percentage point in exports in the EU mar- ket, since there is no bilateral agreement with India in place to protect its imports from the latter [16]. A BFTA between India and EU could also cause a long-term loss in competitiveness for Bangladeshi products in the EU market. However, if a bilateral trade and transport agreement between India and Bangladesh can be reached in the near future, the latter would be able to benefit through the technicality of rules of origin (Roo) in its exports to the EU. Hence, moving forward with the Joint Communiqué 2010 is in Bangladesh’s best interest where all other parties must play a proactive role since it is also in their best interest. Therefore, the potential benefits of economic integration which could be unleashed by close cooperation within the entire SAARC region, is not pre- dictably and therefore, it could be more than what has been encapsulated by the Edgeworth Box. 5. The Way Forward Thanks to Bangladesh’s geographical advantage, the government has a certain degree of political leverage to set the terms of reference in regional connectivity agree- ment. At the time when this paper is going to the press, the government of Bangladesh has not been able to agree on the terminology to be deployed in extracting the gains through transit charges. To be successful, the regional trade facilitation agenda must include measures that are mandatory on the contracting parties and set a specific time-frame for achievement of these measures. Accord- ing to Sobhan (2000), Bangladesh will prefer to use the patronage of SAARC and also ALTID to upgrade its transport links, both to the West and East with India, rather than to pursue this as a purely bilateral exercise. For Bangladesh (and North East India), the primary link remains their regional grouping of SAARC. Finally, it may be noted that in the EU, economics have successfully trumped politics and it remains the driving force behind decisions on regional expansion through integration into the Single Market. After a long time South Asia’s political leadership is demonstrating an awareness that the future is impinging on its present much more rapidly than it did in the past. Their main challenge may therefore be to seize the moment and lead the way into the future rather than being content with th e prevailing status quo by allowing long-term economic considerations to t rump short-te rm political impediments. 6. References [1] S. Ahmed, S. Kelegama and E. Ghani, (Eds.). “Promoting Economic Cooperation in South Asia,” World Bank, Washington D.C., 2010. [2] M. Rahmatullah, “Advancing Bangladesh-India Ecnomic Cooperation: Modalities and Challenges,” Paper pre- sented at the Indo-Bangladesh dialogue organised by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) on March 4, at the CIRDAP, Dhaka, 2010. [3] Indo-Bangladesh Joint Communique 2010 is available online, 2010. http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/ban gladesh/document/papers/indiabangjoint2010.htm [4] ESCAP. Emerging Trade Issues for the Policymakers in Developing Countries of Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), 2008. [5] IMF. International Financial Statistics 2009. Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2009. [6] M. Rahman, “Trade-Related Issues in the Bangladesh-  H. ZAMAN Copyright © 2011 SciRes. ME 70 India Joint Communiqué: Maximising Bangladesh’s Benefits and Strategies for Future,” Paper presented at the Indo-Bangladesh dialogue organised by the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) on March 4, at the CIRDAP, Dhaka, 2010. [7] M. Rahmatullah, “Promoting Transport Cooperation in South Asia,” In Regional Cooperation in South Asia. A Review of Bangladesh’s Development. Dhaka: Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), 2004. [8] P. De, “Regional Cooperation for Regional Infrastructure Development: Challenges and Policy Options for South Asia,” Discussion Paper No. 160. New Delhi: Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), 2009a. [9] P. De, A. R. Khan and S. Chaturvedi, “Transit and Trade Barriers in South Asia: A Review of the Transit Regime and Performance of Strategic Border Crossings,” Work- ing Paper, No. 56, 2008. [10] World Development Report 2009. Reshaping Economic Geography. World Bank, Washington D.C., 2009. [11] P. De, “Inclusive Growth and Trade Facilitation: Insights from South Asia,” Policy Brief, No. 16, 2009b. [12] R. Sobhan, “Rediscovering the Southern Silk Route,” The University Press Limited (UPL), Dhaka, 2000. [13] J. S. Wilson and T. Otsuki, “Regional Integration in South Asia: What Role for Trade Facilitation?” Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4423, 2007. [14] ADB. Quantification of Benefits from Economic Coop- eration in South Asia. Asian Development Bank (ADB), Manila, 2008. [15] V. Sikri, “The Connectivity Issues,” Paper Presented at the Indo-Bangladesh Dialogue Organised by the Asian Institute of Transport Development (AITD) on October 14-16, at the India International Centre (IIC), New Delhi, 2009. [16] S. Raihan, “European Union-India Bilateral Free Trade Agreement Potential Implications for the Excluded Low Income Economies in Asia and Africa,” UNESCAP: ARTNeT, 2009. |