Health

Vol.5 No.12(2013), Article ID:41475,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.512300

Sexual knowledge, attitudes and values among Chinese migrant adolescents in Hong Kong

![]()

Department of Health and Physical Education, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong, China; zzzemmy@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Man-Yee Emmy Wong, Tak-Ming Lawrence Lam. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 3 November 2013; revised 8 December 2013; accepted 25 December 2013

Keywords: Adolescent; Attitude; Knowledge; Migration; Sexuality

ABSTRACT

Internal migration in China has introduced critical challenges to the education and health of migrant adolescents. The aim of this study was to explore the differences in sexual knowledge and attitudes among migrate and local adolescents. Survey research with a total of 616 adolescents in grades equivalent to US 10th and 11th grades including 113 migrants completed a selfadministered questionnaire. Misconceptions of adolescent physical development, sexual activity, marriage, birth control, sexually transmitted diseases and the probability of pregnancy were found in most of the migrant adolescents. Significantly lower attitudinal scores were found for the sub-scales of clarity of personal sexual values, understanding of emotional needs, social behavior, sexual responses; attitudes towards gender role, birth control, premarital intercourse, use of force in sexual activity, the importance of family and satisfaction with social relationship in migrant adolescents. Migrant adolescents have a low level of knowledge of sexual activities. The content of education programs should include engagement in sexual behavior to equip adolescents with unbiased and factual knowledge. The adolescents have a high demand for family support. School based sex education programs should involve the participation of parents to address these issues.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sexual health and sexuality issues have become an increasingly important topic in China. Tang and colleagues (2011) studied a sample of 5156 unmarried female workers in China with an average age of 20.2 years old, and found that they had a low level of sex-related knowledge, especially in the areas of contraceptive methods and HIV/STD transmission and prevention [1]. Other studies have demonstrated that 15% to 35% of Chinese college students in China were unaware that HIV transmission could be prevented by using condoms, and 40% to 60% of the students believed that HIV/AIDS could be transmitted by mosquito bite [2,3]. A study of the knowledge levels of safe sex among Mainland Chinese adolescents reported that only slightly more than half of the respondents could identify a method of contraception. Their knowledge levels of safe sex were generally low, especially among the rural population and migrants [4].

A growing body of literature suggests that Chinese adolescents hold favorable attitudes towards premarital sex. An United Nations-funded survey conducted by the Peking University Population Research Institute indicated that 60% of Chinese youth aged 15 to 24 were open-minded about premarital sex and 22% had had sexual encounters at the time of the survey [5]. A study conducted in Taiwan reported that the average age of first sexual experience for boys was only 16.1 years old [6]. A systematic review investigating unintended pregnancy and induced abortion among unmarried women in China showed that 54% of urban women had sexual experience before their marriage. One third of them had been pregnant and nearly all had had an induced abortion [7].

Sexual health is a complex multi-factorial construct which has many determinants. Migration, gender, socialization of individuals, and the influence of the environment are all important factors. Internal migration in China continued to increase to 271 million persons in 2011, rising by 9.77 million persons over the previous year [8]. Migrant women were found to be three times more likely to get Chlamydia than non-migrant women [9]. The majority of internal migration population is adolescents between the ages of 15 and 24 years old. Studies have indicated that migrant adolescents are more likely to participate in premarital sex, unprotected sex and early engagement in sexual behavior [5,10,11]. They are also less likely to use condoms when compared with nonmigrants [12]. These risky sexual behaviors are more likely to result in teenage pregnancy, unsafe abortions and sexually transmitted infections. They are also particularly vulnerable to performing risky sexual behavior under the influence of rapid modernization and exposure to new ideas [1,13]. While they want to assimilate to local mainstream values and customs, they may also change their health-related attitudes which may thus lead to an increase in risky behaviors [14].

Migrant adolescents may raise different complications for student health behaviors. In China, sex education is included in the formal curricula of secondary schools [3]. Additionally, the China Family Planning Association has also set up different sex education programs beyond the school campus to educate adolescents about reproductive health. There have been a number of new migrants from Mainland China to Hong Kong. However, in terms of the sexual knowledge and attitudes towards sexuality of these young migrant students in Hong Kong, few studies have been reported [15]. No study has been conducted to compare the sexual knowledge and attitudes towards sexuality of migrant and local students.

The purposes of this study are therefore to (a) investigate the levels of sexual knowledge, and the attitudes and values towards sexuality of migrant student adolescents in Hong Kong, and (b) compare the sexual knowledge, attitudes and values towards sexuality of migrant and local adolescents. Following these aims, the research questions are:

Research Question 1: What are the levels of sexual knowledge, and the attitudes and values towards sexuality of migrant adolescents in Hong Kong?

Research Question 2: Are there significant differences in the sexual knowledge, attitudes and values towards sexuality of migrant and local adolescents in Hong Kong?

2. METHOD

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design. Data were collected from secondary school students in grades equivalent to US 10th and 11th grades from threehigh schools located in three different districts from March to April, 2011. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the academic institution, and permission to conduct the research was obtained from the participating schools.

2.1. Participants

The participants were 10th to 11th grade high school students who were able to communicate in Cantonese and were studying in a co-educational school. This age group of students was selected because the prevalence rate of first sexual encounter/intercourseis relatively high at this age [16]. In this study, a migrant student was defined as a person who has resided in Hong Kong for less than seven years. Local adolescent was defined as a youth who has resided in Hong Kong for more than or equal to seven years. This classification was based on the Basic Law of Hong Kong that a person who has ordinarily resided in Hong Kong for a continuous period of more than seven years could be considered as a permanent resident, disregarding whether he/she was born outside Hong Kong.

2.2. Measures

The Chinese version of the Mathtech Sexuality Questionnaire for Adolescents (MSQ-A) was used to measure adolescent sexuality. The MSQ-A consists of Mathtech Knowledge (MKT) and Mathtech Attitudes and Values (MAV) [17]. The Chinese version was translated and validated by Ip [15]. Approval for using the Chinese version of MKT and MAV was granted by the measures’ author, Ip. The knowledge test (MKT) consists of 32 multiple choice items with four possible responses but only one correct choice. It includes 8 areas: 1) 7 questions addressingphysical development; 2) 2 questions for social relationships; 3) 3 for sexual activity; 4) 2 for pregnancy; 5) 3 for marriage; 6) 3 for probability of pregnancy; 7) 7 for birth control; and 8) 5 for sexually transmitted infections. One mark is given for the correct answer of each item. Higher scoring students represent having a higher knowledge level of sexuality. The testretest reliability coefficient for the English version was 0.89 [17] and the Kuder-Richardson 20 coefficient for the Chinese version was 0.76 [15].

The Attitude and Value Inventory (MAV) consists of 70 items with 14 subscalescovering 6 psychological outcomes including 1) clarity of (i) long-term goals and (ii) personal sexual values; 2) understanding of (i) emotional needs, (ii) personal social behavior and (iii) personal sexual responses; 3) attitude towards (i) gender roles, (ii) sexuality in life, (iii) birth control, (iv) premarital intercourse and (v) violence in sexual activity; 4) recognition of family importance; 5) self-esteem; and 6) satisfaction with (i) personal sexuality and (ii) social relationships. There are 5 questions for each subscale.

All items are 5 point Likert-type from 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; and 5 = strongly agree. Each item was either a positive statement or a negative statement. Reverse scoring was carried out in accordance with the guidelines. Subscale scores were derived by summing the relevant items. Students obtaining higher scores indicated that they perceived higher levels of agreement with the attitudes or values in accordance with the prescribed measurement [15]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the English version for the subscales ranged from 0.58 to 0.94 [17] and for the Chinese version ranged from 0.50 to 0.91 [15]. Socio-demographic data including the participants’ age, gender, family income, type of accommodation and living district were also collected.

2.3. Data Collection

A pilot test was carried out with nine 10th grade students to test the procedures and the language of the instruments. Minor changes to the wording of the information sheet were made to ensure clarity. No students involved in the pilot study were included in the main study. All eligible students from the three co-educational secondary schools from three districts in Hong Kong were invited to participate in the study on a voluntary basis if they fulfilled the study criteria. Information sheets to parents were sent out and parental consents for minors were obtained by the school teachers before data collection. The study was explained and an information sheet to students was given to describe the nature of the study. Informed consent was collected immediately after the explanation of the study. An instruction sheet to describe how to fill out the questions was also provided. The Chinese version of MSQ-A was distributed to the students at the end of their last lesson. They were asked to complete the self-administered questionnaire. After completion, the completed questionnaires were collected and sealed in an envelope to ensure confidentiality and nondisclosure to others.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS V20.0 statistical software program. Data were analyzed descriptively using percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Bivariate analyses were conducted between migrant status, other potential variables and the knowledge and attitudes towards sexuality using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Multiple linear regression analysis was applied to examine the differences in the two main outcome variables between migrants and non-migrants with adjustment for potential confounding factors. For further comparisons of subscales between groups, a multivariate approach of Hostelling’s t-tests to adjust for multiple outcomes of the analysis was applied. A significance level of 5% was used for hypothesis testing.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

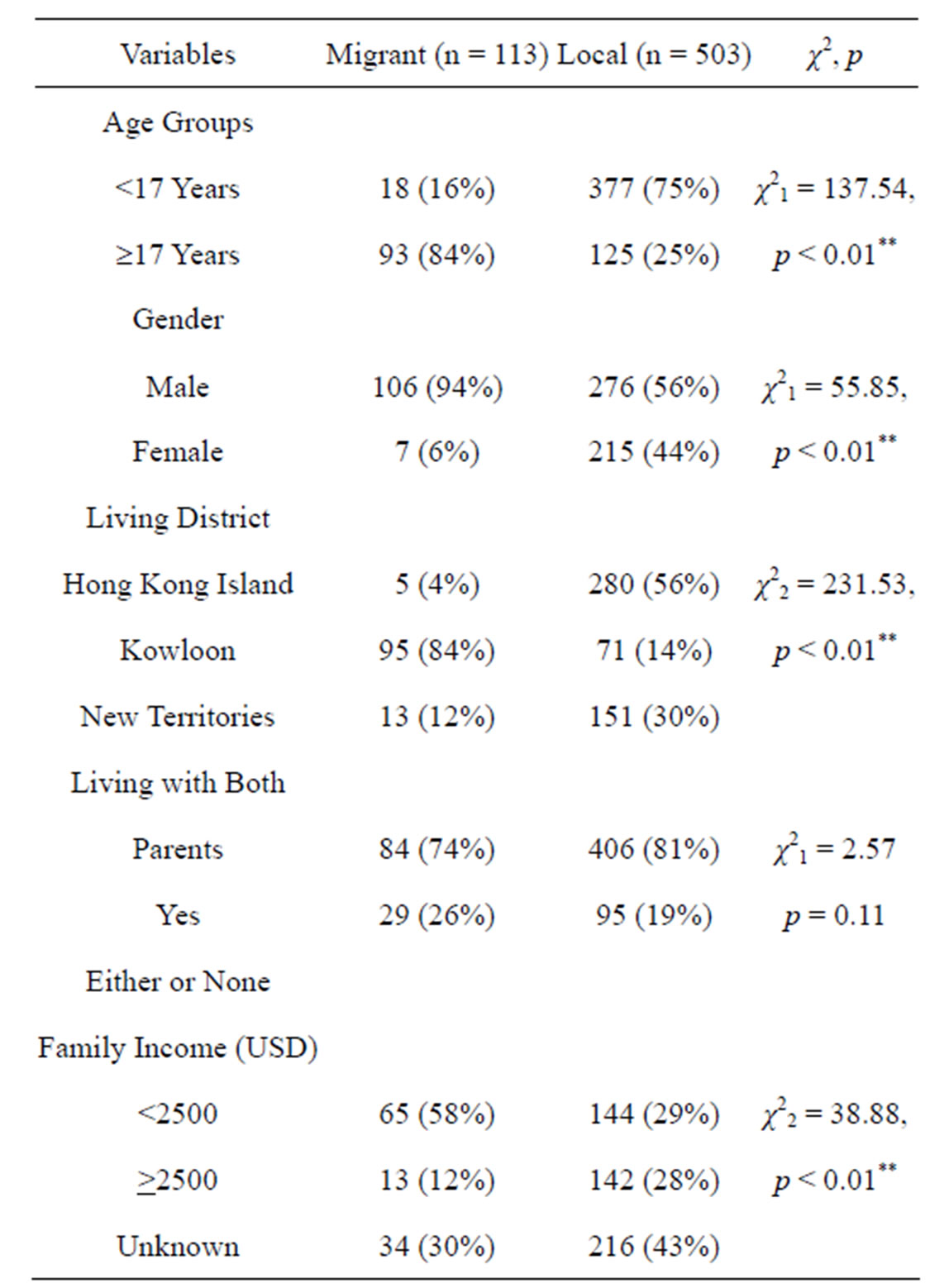

A total of 616 adolescents responded to the survey providing usable information that represented 88.8% of the total number of adolescents in this study. In terms of migration status, 113 (18.4%) were migrant adolescents, while there were 503 local adolescents. The comparison of their demographic characteristics is summarized in Table 1. The sample consisted mainly of younger adolescents aged less than 17 years (n = 395, 64.3%) with migrant adolescents significantly older than the local adolescents (χ2 = 137.54, p < 0.01). Slightly less than a third were male adolescents (n = 382, 63.2%). Only 7 female migrant adolescents were included in this study (χ2 = 55.85, p < 0.01). There was significant difference in the living district (χ2 = 231.53, p < 0.01), with 84% of migrant adolescents living in Kowloon district. The majority of these adolescents were living with both parents (n = 491, 79.8%). A quarter (n = 155, 25.2%) reported a family monthly income of US $2500 or more, with 40% indicating that they did not know about their family in-

Table 1. Comparison of demographics characteristics among the migrant and local adolescents (n = 616).

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

come at all. Migrant adolescents were less well off than the local adolescents (χ2 = 38.88, p < 0.01).

3.2. Sexual Knowledge and Attitudes and Values towards Sexuality of Migrant Adolescents

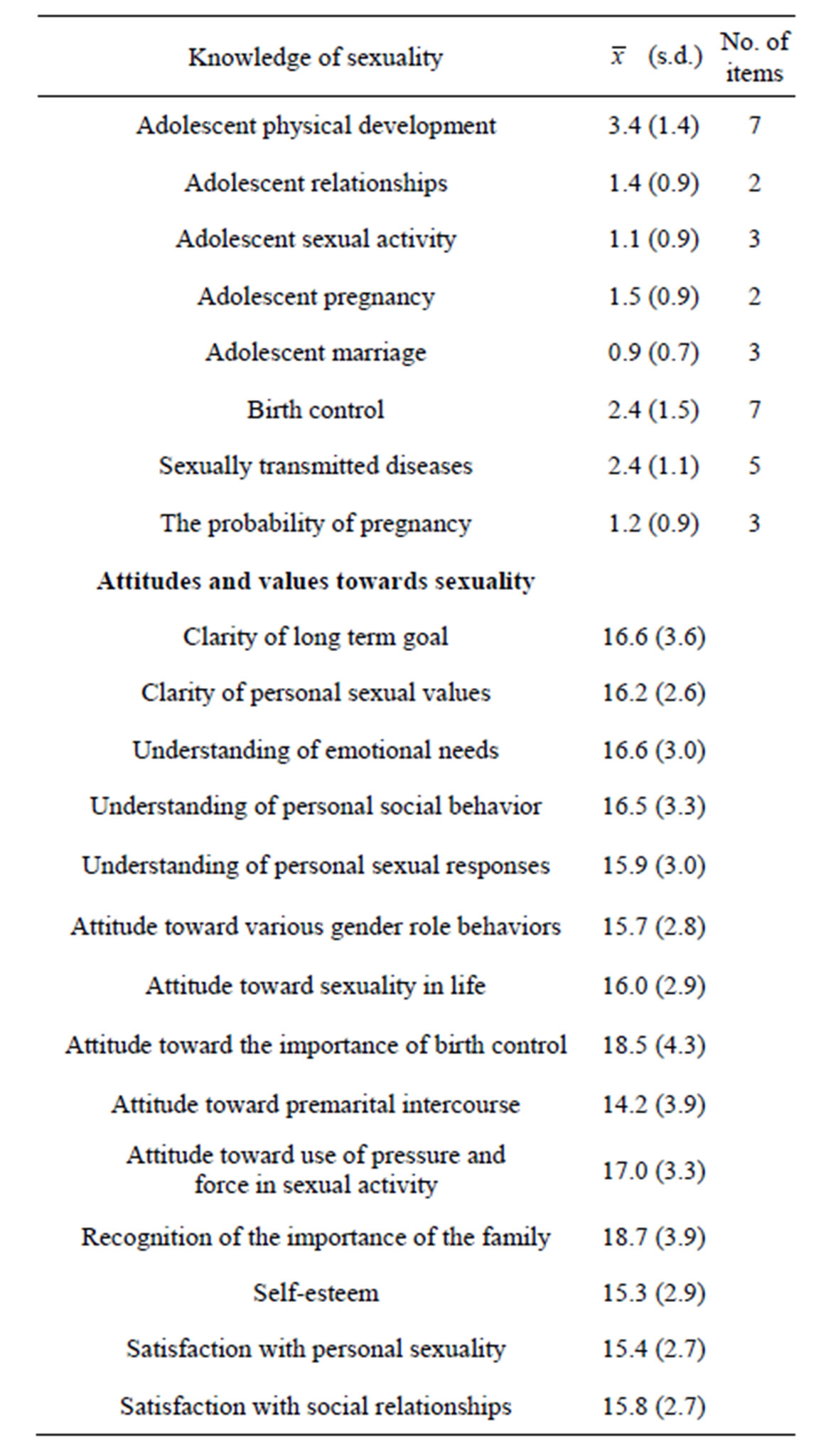

The data regarding the migrant adolescents’ sexual knowledge is presented in Table 2. The main results show that less than half of the adolescents knew about adolescent physical development (correct % = 48.6%), sexual activity (36.7%), marriage (30%), birth control (34.3%), sexually transmitted infections (48%) or the probability of pregnancy (40%).

Considering the low knowledge score of birth control among migrant adolescents, the attitude toward impor-

Table 2. Sexual knowledge and attitudes toward sexuality of migrant students (n = 113).

tance of birth control gave a very interesting finding. The mean attitudinal score of attitude toward birth control was 18.5 out of the maximum score 25 (SD = 4.3) which was the second highest attitude score among the subscales of attitudes towards sexuality, while the highest scores of the attitude towards sexuality was recognition of the importance of the family ( = 18.7; SD = 3.9). The lowest attitude score was attitude toward premarital intercourse (

= 18.7; SD = 3.9). The lowest attitude score was attitude toward premarital intercourse ( = 14.2; SD = 3.9). Other attitudinal scores less than 16 included understanding of personal sexual responses (

= 14.2; SD = 3.9). Other attitudinal scores less than 16 included understanding of personal sexual responses ( = 15.9, SD = 3.0), gender role behaviors (

= 15.9, SD = 3.0), gender role behaviors ( = 15.7; SD = 2.8), self-esteem (

= 15.7; SD = 2.8), self-esteem ( = 15.3; SD = 2.9), satisfaction with personal sexuality (

= 15.3; SD = 2.9), satisfaction with personal sexuality ( = 15.4; SD = 2.7), and satisfaction with social relationships (

= 15.4; SD = 2.7), and satisfaction with social relationships ( = 15.8; SD = 2.7).

= 15.8; SD = 2.7).

3.3. Comparison of the Sexual Knowledge, Attitudes and Values Towards Sexuality of Migrant and Local Adolescents

The bivariate relationships between migrant status, demographic variables and sexual knowledge as well as attitudes toward sexuality were examined. Without adjustment to other variables, migration status was significantly associated with both sexual knowledge (t = −3.67, p < 0.01) and attitudes towards sexuality (t = −3.90, p < 0.01). Other potential confounding variables found to be associated with sexual knowledge include age, gender and living district. Family income was also associated with attitudes toward sexuality in addition to gender and living district. These variables were included in the regression analyses for the adjusted relationship between duration of migration and sexual knowledge as well as attitudes towards sexuality for their potential confounding effects.

After adjusting for potential confounders, there was insufficient evidence of an association between migrant status and sexual knowledge (t = −0.18, p = 0.86). On the other hand, migrant status was significantly related to overall attitudes towards sexuality (t = −2.97, p < 0.01), with those who had migrated to Hong Kong less than 7 years previously, on average, nearly 10 units lower than those who had migrated earlier or who were born in Hong Kong.

Further analyses of the differences between groups for each sub-scale of attitudes toward sexuality indicated that of the 14 sub-scales, significant differences were found in 10. In all of these 10 sub-scales, migrant adolescents scored significantly lower than the local adolescents. The 10 subscales were clarity of personal sexual values (F = 8.59, p < 0.01), understanding of emotional needs (F = 6.46, p = 0.01), understanding of personal social behavior (F = 5.49, p = 0.02), understanding of personal sexual responses (F = 12.12, p < 0.01), attitude toward various gender role behaviors (F = 28.82, p < 0.01), attitude toward the importance of birth control (F = 20.23, p < 0.01), attitude toward premarital intercourse (F = 4.93, p = 0.03), attitude toward use of pressure and force in sexual activity (F = 20.18, p < 0.01), recognition of the importance of the family (F = 13.45, p < 0.01) and satisfaction with social relationships (F = 7.88, p < 0.01). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Although there was no significant difference in the overall knowledge scores of the two groups, local adolescents had higher sexual knowledge scores than migrant adolescents in all the subscales of sexual knowledge. The statistically significant higher scores of the subscales were adolescent physical development (F = 4.77; p = 0.03), adolescent relationships (F = 16.62; p < 0.01), adolescent sexual activity (F = 10.31; p < 0.01) and birth control (F = 20.78; p < 0.01).

Table 3. Comparisons of attitudinal sub-scales between local and migrant adolescents.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

4. DISCUSSION

This study investigated the sexual knowledge and attitudes toward sexuality of Chinese migrant adolescents and compared the issues for the Chinese migrant and local adolescents in Hong Kong, using a well-tested Chinese version of MSQ-A. Consistent with the previous studies conducted among local adolescents in Hong Kong [15], the level of sexual knowledge among adolescents in this study is generally low, while that of the migrant adolescents is lower than that of the local adolescents. A possible explanation for this situation is that sexual knowledge and related issues have had no obvious improvement in the education system in recent years.

Lo (2009) comments that the sex education in Hong Kong is highly ineffectual. The current teaching curricula for sex education in secondary school is largely focused on understanding the human anatomy of the reproductive system, while sexuality issues are often avoided. Current teaching on sex education is based on the guidelines published in 1997 and 2001. These guidelines, however, are not compulsory for schools to follow but are recommendations only. Schools usually integrate sex education into biology, science and liberal studies [19,20]. The sexual knowledge level among the migrant adolescents was even lower than that of local adolescents. While reproductive and sexual knowledge in China is considered as inadequate [4,21,22], the local sex education becomes worse for migrant adolescents. In this study, the migrant adolescents had an especially low level of knowledge of sexual activities, marriage, birth control and probability of pregnancy, which are related to the practical issues of sex engagement.

Inconsistent with recent studies conducted in other Western countries of Chinese migrant college students [23], but similar to the findings of previous studies in Hong Kong [24,25], the attitudes of adolescents in this study were less tolerant of premarital intercourse. One possible explanation is that there are cultural differences among adolescents growing up in Hong Kong in comparison to those in Western countries. Hong Kong is fundamentally a place with strong Chinese heritage with traditional Chinese sexual values that are mainly based on Confucian thinking. The tradition stresses the role of the individual in family and societal structures.

The importance of the family perceived by the migrant adolescents was a significant factor affecting their attitudes toward sexuality in this study. Previous studies have suggested that sexual behavior is significantly associated with the interaction of family, social, personal, substance use and environmental factors [26-29]. The family, social and environmental factors in this study could be related to the family income and satisfaction with social relationships among migrant adolescents. Wang and colleagues (2006) found that adolescents living with their parents were less sexually active and supported the importance of family influences as a strong protection affecting adolescents’ positive sexual attitudes [30]. However, traditional Chinese parents are reluctant to discuss sexual matters with their children. Together with the lack of school-based sex education programs, this further contributes to adolescents’ poor understanding of sexuality that may heighten their susceptibility to engage in sexual activities [31,32].

The migrant adolescents were significantly older than the local adolescents in this study. The reason may be related to the discretionary places and central allocation of secondary school places in Hong Kong. It is common for parents to help their children choose the high band secondary schools if their children achieve good academic performance. As new migrant adolescents take time to adapt to the local education curriculum, the current system may not favor them in obtaining places in high band schools. In this study, the other two secondary schools were more popular than the secondary school in the Kowloon district, so migrant students were more likely to study in this school.

4.1. Limitations

In light of the study limitations, this study was focused on a sensitive issue in Chinese culture. The adolescents might have underreported their attitudes and values. In order to minimize this bias, their confidentiality was ensured using the anonymous self-administered survey [33]. Second, another limitation identified was the other factors which may be associated with their sexual knowledge and their attitudes towards sexuality including the occurrence of sex experiences, substance abuse, parents’ influence and their relationship with their parents. Further study is needed to investigate the effects of these variables. Third, we employed convenience samples in the regression analysis. We used a relatively large sample size that can reduce the random effect and which provides a more precise estimate. Fourth, migrant adolescents reflected that they had negative attitudes toward various gender role behaviors and use of pressure and force in sexual activity. It provides essential information to understand the migrant adolescents’ attitudes towards the virtues of pluralism. However, the number of female migrant adolescents is inadequate to provide further analysis in this study. Further study is needed to study the concept of sexual orientation and to explore the areas of homosexuality among migrant adolescents.

4.2. Implications for School Health

With understanding of the migrant adolescents’ sexual knowledge and attitudes of sexuality, health administrators should note that there is a need to revise and redesign the guidelines for existing sex education content to inculcate adolescents with positive attitudes and values toward sexuality and to meet the needs of the current society [22,34]. While migrant adolescents’ attitudes toward the importance of birth control were particularly positive but with limited birth control knowledge, the content of education programs should go beyond growth and puberty and should include use of contraceptive methods, harmful effects associated with abortion, premature sex, total abstinence from sex and engagement in sexual behavior to equip students with unbiased and factual knowledge [18].

School health officials are encourage to make use of these findings to design the sex education programs focusing on reviewing basic sexual knowledge and healthy behavior in the teaching package [35]. More family involvement and school adjustment may help migrant adolescents to adapt to the changes and different cultures in their new living environment [36]. School-based adolescent-parents communication programs can increase parental access to the schools and help migrant adolescents appreciate the value of traditional approaches. Parents can be helped to understand ways of problem solving and finding resolutions that are acceptable to both parties. Parent support groups can provide a platform for migrant parents to share their experiences of facing conflicts with their children. Programs might emphasize skills promoting migrant competence according to cultural and social needs for traditional and modern sexual values.

Given migrants’ lack of sexual knowledge and strong needs for family support, school-based interventions in collaboration with health educators may be more effective, especially for the limitations of the current education curriculum [37,38]. Health educators might need to proactively contact the schools to build up a sense of school connectedness for adolescent development. They may help to set up a youth development program targeting the learning needs and the attitudes of the migrant adolescents which can provide support to guide their sexual choices [39]. Health educators can help in teacher training [40] and involved in different sex education programs to work with migrating adolescents and their parents.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study to examine the differences in the sexual knowledge, attitudes and values towards sexuality of Chinese migrant adolescents in Hong Kong. It contributes to the international literature by expanding the knowledge across cultures on adolescents’ sexual values. The results show that adolescents in Hong Kong lack sexual knowledge and a substantial proportion of them have limited birth control knowledge. The scores on attitudes towards sexuality of the migrant adolescents are significantly lower than those of the local adolescents for most of the items. Health education programs that target improving the sexual knowledge of adolescents and building family support for self-belief among migrant adolescents are needed.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our grateful acknowledgement of the schools and teachers for their assistance in data collection, and the students who agreed to participate in this study, and of Prof. Ip for her approval to use the Chinese version of MSQ-A.

REFERENCES

- Tang, J., Gao, X., Yu, Y., Ahmed, N.A., Zhu, H., Wang, J. and Du, Y.(2011) Sexual knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among unmarried migrant female workers in China: A comparative analysis. BMC Public Health, 11, 1-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-917

- Chen, H., Zhang, L., Han, Y., Lin, T., Song, X., Chen, G. and Zheng, X. (2012) HIV/AIDS knowledge, contraceptive knowledge, and condom use among unmarried youth in China. AIDS Care, 24, 1550-1558. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.674093

- Sun, X., Liu, X., Shi, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, P. and Chang, C. (2013) Determinants of risky sexual behavior and condom use among college students in China. AIDS Care, 25, 775-783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.748875

- Zhang, L., Li, X. and Shah, I.H. (2007) Where do Chinese adolescents obtain knowledge of sex education in China? Health Education, 107, 351-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09654280710759269

- Peking University (2010) Final report on the 2009 national youth reproductive health survey. Institute of Population Research, Peking University, Beijing.

- Ma, K.Y. (2010) Health newsletter 5. Education in sexuality: DOH tackles sensitive issue of sex among teens. Department of Health, Taiwan.

- Qian, X., Tang, S.L. and Garner, P. (2004) Unintended pregnancy and induced abortion among unmarried women in China: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 4, 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-4-1

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (2012) China’s total population and structural changes in 2011. National Bureau of Statistics of China, China.

- Wang, W., Wei, C., Buchholz, M., Martin, M.C., Smith, B.D., Huang, Z.J. and Wong, F.Y. (2010) Prevalence and risks for sexually transmitted infections among a national sample of migrants versus non-migrants in China. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 21, 410-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/ijsa.2009.008518

- Li, S.H., Huang, Y., Cai, G., Xu, F.H. and Shen, X. (2009) Characteristics and determinants of sexual behavior among adolescents of migrant workers in Shanghai (China). BMC Public Health, 9, 195-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-195

- Tang, L., Chen, R., Huang, D., Wu, H., Yan, H., Li, S. and Braun, K.L. (2013) Prevalence of condom use and associated factors among Chinese female undergraduate students in Wuhan, China. AIDS Care, 25, 515-523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.720360

- Sudhinaraset, M., Astone, N. and Blum, R.M. (2012) Migration and unprotected sex in Shanghai, China: Correlates of condom use and contraceptive consistency across migrant and non-migrant youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, S68-S74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.007

- Yu, J. (2010) An overview of the sexual behaviour of adolescents and young people in contemporary China. Australasian Medical Journal, 3, 397-403. http://dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2010.317

- Reijneveld, S.J., van Nieuwenhuijzen, M., Velderman, M.K., Paulussen, T.W. and Junger, M. (2012) Clustering of health and risk behaviour in immigrant and indigenous Dutch residents aged 19-40 years. International Journal of Public Health, 57, 351-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0350-4

- Ip, W.Y., Chau, J.P.C., Chang, A.M. and Lui, M.H.L. (2001) Knowledge of and attitudes toward sex among chinese adolescents. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 23, 211-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/019394590102300208

- The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong (2007) Youth sexuality study 2006. The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

- Kirby, D. (1990) Sexuality questions and scales for adolescents. ETR Associate, Stockton.

- Lo, A. (2009) Reform of sex education for the next generation. Improving Hong Kong, 6, 8-10.

- Government Information Centre (2006) Sex education in schools press releases. http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/200605/17/P200605160251.htm

- Education Bureau (2011) Sex education website preface.

- Guo, W., Wu, Z., Shimmele, C.M. and Zheng, X. (2012) Condom use at sexual debut among Chinese youth.

- World Health Organization (2010) Social determinants of sexual and reproductive health: Informing future research and programme implementation. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Zhuang, X., Wu, Z., Poundstone, K., Yang, C., Zhong, Y. and Jiang, S. (2012) HIV-related high-risk behaviors among Chinese migrant construction laborers in Nantong, Jiangsu. PLoS ONE, 7, 1-6.

- Lam, T.H., Stewart, S.M. and Ho, L.M. (2001) Prevalence and correlates of smoking and sexual activity among Hong Kong adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29, 352-358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00301-9

- Wong, W.C., Lee, A., Tsang, K.K. and Lynn, H. (2006) The impact of AIDS/sex education by schools or family doctors on Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11, 108-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13548500500156105

- Wang, J., Simoni, P., Wu, Y. and Banvard, C. (2008) Female adolescents’ attitude towards sexually risky behaveiors. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 10, 120- 133.

- Liu, Z.H., Wei, P.M., Wang, X.S., Huang, M.H., Li, X.N. and Yang, G.P. (2008) Investigation on influencing factors of sexual behaviors among college students in Nanjing. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 24, 1243-1245.

- Lee, L.K., Chen, P.C., Lee, K.K. and Kaur, J. (2006) Premarital sexual intercourse among adolescents in Malaysia: A cross-sectional Malaysian school survey. Singapore Medical Journal, 47, 476-481.

- Wu, Y. (2009) Incidence of sexual behaviors and the influencing factors among undergraduates in Guangzhou. Modern Preventive Medicine, 36, 282-284.

- Wang, J., Simoni, P. and Wu, Y. (2006) Human Papillomavirus (HPV) in rural adolescent females: Knowledge, protective sex, and sexual risk behaviors. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care, 6, 74-88.

- Kunnuji, M.O.N. (2012) Parent-child communicaton on sexuality-related matters in the city of Lagos, Nigeria. Africa Development, 37, 41-58.

- Sax, L. (2005) Why gender matters: What parents and teachers need to know about the emerging science of sex differences. Doubleday, New York.

- Gao, E., Lou, C. and Liu, Y. (2003) Assessment on accuracy of the data concerning first sexual behavior in Shanghai, China. Reproduction and Contraception, 10, 421-435.

- Fok, S.C. (2005) A study of the implementation of sex education in Hong Kong secondary schools. Sex Education, 5, 281-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14681810500171458

- Henderson, M., Wight, D., Raab, G.M., Abraham, C., Parkes, A., Scott, S. and Hart, G. (2007) Impact of a theoretically based sex education programme (SHARE) delivered by teachers on NHS registered conceptions and terminations: Final results of cluster randomised trial. BMJ, 334, 133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39014.503692.55

- van Geel, M. and Vedder, P. (2011) The role of family obligations and school adjustment in explaining the immigrant paradox. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 187-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9468-y

- Sudhinaraset, M., Mmari, K., Go, V. and Blum, R. (2012) Sexual attitudes, behaviours and acculturation among young migrants in Shanghai. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14, 1081-1094. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.715673

- Markham, C.M., Fleschler Peskin, M., Addy, R.C., Baumler, E.R. and Tortolero, S.R. (2009) Patterns of vaginal, oral, and anal sexual intercourse in an urban seventh-grade population. Journal of School Health, 79, 193-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00389.x

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) School connectedness: Strategies for increasing protective factors among youth. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta.

- Herr, S.W., Telljohann, S.K., Price, J.H., Dake, J.A. and Stone, G.E. (2012) High school health-education teachers’ perceptions and practices related to teaching HIV prevention. Journal of School Health, 82, 514-521. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00731.x