Engineering, 2013, 5, 189-194 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2013.510B040 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/eng) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG Positive-Negative Emotional Categorization of Clothing Color Based on Brightness Xiao-Feng Jiang1,2, Xiao-Pei Bian1 1College of Textile and Clothing Engineering, Soochow University, Suzhou, China 2National Engineering Laboratory for Modern Silk, Soochow University, Suzhou, China Email: xfjiangsz@163.com Received May 2013 ABSTRACT In current study, behavioral measures were conducted to investigate clothing color. The purpose was to focus on the rule that color brightness influenced positive-negative emotional categorization. Results showed that the effect of brightness on clothing color emotion categorization was significant. With the increase of brightness, the variation curve of positive emotion appears to be a “U-shaped”, whereas that of the negative emotion shows an upside down “U- shaped”. Compared with the low brightness colors, the emotion reaction to the high brightness colors was more positive; Most of the colors with different brightness scales were classified as positive emotions and the minors were classified as negative emotions; the positive colors could be done much faster than the negative ones. Keywords: Color Emotion; Response Time; Brightness; Categorization; Positive-Negative 1. Introduction Color is ubiquitous in our perceptual experience of the world when we encounter objects like clothing items. It is widely recognized that color is an essential ingredient in the perception of fashion, since it plays an imperative role in wearer’s emotional expression and the image building on various occasions. For example, for sports- wear, vivid and medium brightness are more used in representing active and vigorous activities. For under- wear, colors of high brightness are usually chosen to keep in harmony with the relaxed conditions and to give relatively comfortable and simple impression. However, for working uniform, the occupational characteristic is mainly emphasized, and it is necessary to select the col- ors of lower brightness for office clothing in order to show solemnities [1-3]. The brightness can be changed by adding black or white, which may evoke dissimilar human feelings [4]. Much research on brightness stimuli of color indicated that individuals associate colors with emotions, for ex- ample, a color of higher brightness will evoke light and pure feelings; that of medium brightness may be easily perceived as an implicit and featureless sense; that of lower brightness represents mysterious and depressed sensation, etc. [5-7]. These feelings, evoked by either colors or color combinations, are called color emotions. However, the relation between color and emotion is very intricate, because it may be influenced by the factors such as genders, cultural backgrounds and so on. Never- theless, some researchers found that the influence of cul- tural background was very limited, whereas brightness and saturation were the most important factors influen- cing color emotion. For example, J. H. Xin et al. investi- gated cross-regional color emotions, and found that the hue was much less predominant for color emotions than brightness and saturation [8]. It is notable that color emotions can also be divided into the positive and negative parts in line with the arousal by different colors. For instance, Red has both positive and negative impressions such as passionate, active, and conversely raging and offensive. Blue also has both positive and negative impressions such as faith- ful and calm, but on the other hand impassive and de- pressed. Shirley Willett’s color codification of emotions intuitively suggested the positive-negative emotions of colors. That is, the outside circle includes positive traits and the inside circle indicates negative ones [9]. Some researchers believed that positive-negative emotions of color are typically expressed with semantic word pairs, such as “vivid/sombre”, “gaudy/plain”, “striking-sub- dued” etc [10]. Except for the hue of colors, some studies aimed at the brightness, from which the effects of posi- tive-negative emotions also have been found. Boyatzis and Varghese reported that bright colors evoke mainly positive emotional associations, while dark colors evoke negative emotional associations [11]. Numerous re- searches focus on the relation between emotion and the color perceived by human beings. Unfortunately, most of  X.-F. JIANG, X.-P. BIAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG them have used only square color patches in the experi- ments and do not consider any effect of shape [12,13], while a few studies used contextualized colors such as full scale simulations of clothing. In fact, these investiga- tive results were unrealistic to apply to clothing [14]. Furthermore, only few researches have provided experi- mental evidence on positive-negative emotional catego- rization of clothing color based on human behavior. Thus, in this study, clothing as stimuli were selected, and the behavioral cognition of colors based on brightness was evaluated using psychology software tools. This study has three main objectives as follows: 1) To investigate the influence of different brightness on the positive-negative emotional categorization; 2) To explore the rule of positive-negative emotional categorization; 3) To evaluate the time course during the categoriza- tion. 2. Experiment 1 2.1. Participants 50 undergraduate students from Soochow University (18 males, 32 females, aged in 20 - 22) participated in the experiment. All the subjects reported that they are right- handled and they have normal corrected vision. The par- ticipants were tested individu ally. 2.2. Stimuli 60 words were picked out from a large number of litera- tures to describe colors as stimu li and were formed into 30 word pairs preliminarily. 2.3. Procedure The experiment consisted of two phases. In one phase the suitability of words were evaluated and in another phases the positivity and negativity of words were evaluated. In Phase 1, each trial had only one word, and it began with the presentation of a fixed cross in the center of the screen for 100 ms. After 400 ms, a word was displayed for 300 ms on a white background randomly. After that, the participants must evaluate the suitability or positivi- ty-negativity of the word (show n in Figure 1). Responses were collected via keyboard. Before the experiment, 10 trial words were used to acquaint with the manipulative method by the participants. Then, an instruction page informed the participants that they had done with the test and that the phase 1 was about to begin. The stimuli and the procedure in Phase 2 were the same as those in Ph ase 1. 2.4. Results and Discussion The results are shown in Figure 1. When the acceptance Figure 1. Procedure of presenting stimuli. rate is above 50%, it means that more than half of the subjects thought that the evaluated word is suitable or positive. If it is below 50%, it means that half of them thought that the evaluated word is unsuitable or negative. The picked words show in Figure 2. It is obvious that the acceptance rate of each admitted positive word was much larger than 50%, while the admitted negative word was smaller than 50%. The seven word pairs chosen from the measurement were “light/dark”, “warm/cool”, “vivid/ sombre”, “graceful/vulgar”, “vigorous/weary”, “high- class/low-class” and “dynamic/passive”. The behavioral test in this experiment answered prop- erly what we concerned. That is, which words are more suitable to be used to describe clothing colors and which words are positive and negative? Therefore, we are firm- ly convinced that these word pairs assessed from the ex- periments are effective to be used as stimuli in Experi- ment 2. Behavioral test has some advantages. On the one hand, it makes subjects decide the best words, which reflected the subjects’ objective cognitive level of cloth- ing colors and avoided our subjective intention to pick out color words. On the other hand, each word had an independent test, which was not subject to interference from the other words. 3. Experiment 2 3.1. Participants 38 undergraduate students who have already finished experiment 1 (14 males, 24 females, aged in 20 - 22) participated in th is experiment, whose majors have noth- ing to do with clothing. All subjects had normal or cor- rected-to-normal vision and were unaware of the purpose of the experiment. 3.2. Equipment and Stimuli The stimuli were presented on a 17-inch monitor con- nected to a 2 GHz Pentium computer in a dimmed room, the distance between participants and monitor was about 60 cm, and the visual angle was 12.3˚ × 4.9˚, using E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). In this experiment, the color images were used as stimuli. Pic-  X.-F. JIANG, X.-P. BIAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG Figure 2. Acceptance rates of the seven word pairs. tures were produced with the Photoshop 7.0 procedure. Five basic colors were selected evenly from the 360˚ color wheel at the interval of 72 ˚. Then, according to the hue/saturation pattern, every basic color was divided into 9 sub-colors with different brightness (change interval: 18), in which the brightness at level 1 was lowest while it was highest at level 9. Finally, all these colors were pre- sented in clothing (shown in Figure 3). All the colors are based on the RGB color mode. 3.3. Procedure There were 45 pictures used as stimuli. The experiment included 630 trials and was divided into three phases for alleviating the subjects’ fatigue. Each trial had only one word and one color picture, and it began with the pres- entation of a fixed cross in the center of the screen for 100 ms. After 400 ms, a word was displayed for 300 ms on a uniform white background, and then followed by a color image which appeared randomly. After that, the participants must evaluate the emotion of the color of the image (shown in Figure 4). Responses were collected via keyboard. The subjects pressed “A” in keyboard if he thought the color emotion was in accordance with the word. Otherwise, he should press “L” in keyboard. Be- fore the experiment, 10 trial images were also provided to acquaint with the manipulative method. Then, an in- struction page informed the participants that they had done with the test and that the phase 1 was about to begin. The stimuli and the procedure in Phase 2 and Phase 3 were the same with those in Phase 1. 3.4. Results and Discussion 3.4.1. Differences of Positive-Negative Emotional Categorization Figure 5 presents the mean categorization accuracy of positive-negative emotions for seven word pairs. In gen- eral, In 630 colors, about two-thirds of them (M = 0.59, MSE = 0.02) were classified as the traits of positive emotion. On the contrary, only around one-thirds of them (M = 0.31, MSE = 0.02) were classified as the traits of Figure 3. The sample of brightness changes for clothing. Figure 4. Procedure of presenting stimuli. Figure 5. Differences of positive-negative emotional catego- rization among the word pairs. negative emotion. The data were fed into multiple-factor repeated-measures ANOVA, with Type (positive, nega- tive) × Brightness (1-9). There was a significant main effect of type [F (1, 37) = 113.37, p < 0.00], implying that participants deemed that most of the colors are posi- tive. In addition, there is also a significant interaction suitable positive-negative  X.-F. JIANG, X.-P. BIAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG effect between type and word pair. However, there was no significant main effect of word pair [F (6, 222) = 1.85, p = 0.11], suggesting that the differences of emotional categor i z a tion are not re markabl e among the w or d pa i rs. 3.4.2. Rules of Positive-Negative Emotional Categorization Based on Brightness Mean categorization ratings for colors are plotted in Figure 6. There was a significant main effect of bright- ness [F (2, 296) = 23.05, p < 0.00], implying that there were prominent differences of emotional categorization among various clothing brightness. Apparently, with the increase of brightness, the varia- tion curve of negative emotion shows a “U-shaped”, whereas that of the positive emotion shows an upside down “U-shaped”. That is, they presented a pattern that the positive emotions gradually weakened after enhanc- ing according to brightness scales from 1 to 9, the lower brightness colors had weaker positive emotions, but the medium brightness colors had stronger positive emotion. But for negative emotion, it shows the inverse trend. In fact, the “U-shaped” is not asymmetrical. Compared with the low brightness colors, the high brightness colors were easier to be categorized as the positive emotions. In addi- tion, there is also a significant interaction effect among the type, word pair and brightness, [F (48, 1776) = 9.04, p < 0.00]. In order to investigate the emotional categori- zation for every word pair, we conducted an ANOVA of Type (positive, negative) × Brightness (1 - 9) with re- peated measurement, respectively. The results show that the main effects of brightness are very significant for seven word pairs, as shown in Table 1. 3.4.3. RTs of Positive-Negative Emot ional Categorization The response times (RTs) for positive and negative emo- tions are shown in Figure 5. There was a significant main effect of type [F (1, 37) = 61 .01, p < 0. 00], indicat- ing that significant differences of RTs existed between the two emotional types during the Participants catego- rizing them. Compared with categorizing the negative emotions (M = 736.7 ms, MSE = 23.1 ms), categorizing the positive emotions (M = 677.8 ms, MSE = 19.4 ms) were faster. This evidence revealed a fact that it is diffi- cult to classify negative emotions. For the word pairs, there was also a significant main effect in RTs [F (6, 222) = 7.10, p < 0.00]. It suggests that the differences of RTs were distinct among the word pairs. For example, the speed of emotional categorization after the word pair “light/dark” Primi n g (M = 690.7 ms, MSE = 20.4 ms) was faster than that of emotional categorization after the word pair “dynamic/passive” priming (M = 728.1 ms, MSE = 24.3 ms). We also used a two-way ANOVA of Type (positive, Figure 6. Tendency of positive-negative emotional categori- zation based on brightness. negative) × Brightness (1 - 9) with repeated measurement respectively so as to verify this phenomenon. The results show that the main effects are very significant for all the seven word pairs. As shown in Table 2. Further results confirm the fact that categorizing the positive emotions is easier than categorizing the negative emotions. The classification results of seven words consistently reflected a rule. That is, no matter what the brightness is, the subjects responded more quickly in classifying the colors as positive emotion than as negative emotion. There are many explanations about this phenomenon. The reasonable ones are as follows: Firstly, based on the theory of H. Bless [15], the participants were more likely to adopt the heuristic strategy in a positive mood, which is a top-down way of processing information, and more depends on the color schema in the brain and ignores the details. On the contrary, the participants were more likely to adopt the strategy in a negative mood. That is a bot- tom-up way of processing , which less depends on the color schema in the brain and gives more attention to the details. Therefore, the time is less in matching the color schema than in processing the details. Accordingly, it prolonged the response time. Secondly, there are two methods for handling envi- ronment or stimuli for human. They are behavioral ap- proach and behavioral avoidance. When facing with a positive environment or stimulus, he can respond with approach, while when facing with a negative environ- ment or stimulus, he may makes a response with avoid- ance, which must have triggered a delayed-response [16]. According to this theory, the participants spontaneously adopt the way of approach to complete the classification task after the onset of positive emotion, while the avoid- ance is used after the onset of negative emotion, which would increase the response time. Based on affective- matching theory, if the affective word is in line with the evaluation of target stimuli, rationality which promotes positive response will be added. Otherwise, it will create a sense of unreasonable, repressing the response [17].  X.-F. JIANG, X.-P. BIAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG Table 1. Main effect of emotional categorization for the seven word pairs. Source Sum of squares Mean square F Sig. Partial eta squared Light/dark 18.03 18.03 141.61 0.000 0.79 Warm/cool 3.27 3.27 20.44 0.000 0.36 Vivid/sombre 14.94 14.94 115.63 0.000 0.76 Graceful/vulgar 21.80 21.80 88.36 0.000 0.70 Vigorous/weary 9.81 9.81 44.03 0.000 0.54 High-class/low-class 20.95 20.95 114.25 0.000 0.76 Dynamic/passive 17.37 17.37 90.36 0.000 0.71 Table 2. Main effect for RTs of emotional categorization for the seven word pairs. Source Sum of squares Mean square F Sig. Partial eta squared Light/dark 527913.44 527913.44 23.83 0.000 0.39 Warm/cool 706203.19 706203.19 18.89 0.000 0.34 Vivid/sombre 281005.11 281005.11 17.31 0.000 0.32 Graceful/vulgar 464731.30 464731.30 13.34 0.001 0.26 Vigorous/weary 566694.10 566694.10 15.90 0.000 0.30 High-class/low-class 686642.96 686642.96 28.25 0.000 0.43 Dynamic/passive 1052850.04 1052850.04 35.32 0.000 0.49 Figure 7. RTs of positive-negative emotional categorization for the seven word pairs. Figure 8. RTs of positive-negative emotional categorization based on bright ness. Finally, in this experiment, the probability of positive and negative words was the same, but the subjects pre- ferred to classify most of color as positive, which has been mentioned in the previous discussion. So the con- flicts were less between positive words and clothing col- or than those between negative words and clothing color, resulting in longer RTs. This is in line with the Stroop effect and we believe this explanation is most persuasive [18]. 4. Conclusion Several significant findings have been revealed from the behavioral. Firstly, the effect of brightness on clothing color emotion categorization was incredibly remarkable and stable. With the increase of brightness, the variation curve of positive emotion presented a “U-shaped”, whe- reas that of the negative emotion showed an upside down “U-shaped”. And the emotion reaction to the high bright- ness colors was more positive, compared to the low brightness colors. Secondly, most of the colors with dif- ferent brightness levels were classified into the group of positive colors and the minors were classified into the group of negative colors. Finally, categorizing the posi- tive colors was much faster than categorizing the nega- tive ones. 5. Acknowledgements This work was funded by A Project Funded by the Prior- ity Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher  X.-F. JIANG, X.-P. BIAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ENG Education Institutions (PAPD), and was supported by JSNSF Grant (No. BK2012196). REFERENCES [1] A. Naitou and S. Kobayashi, “A Dressing Image and a Color Effect of Women’s Suits,” Journal of the Japan Research Association for Textile End-Use, Vol. 43, No. 10, 2002, pp. 52-62. [2] C. Mizutani, S. Otsuki, C. Ued and S. Park, “A Compari- son of the Relationship between Color of Wearing Clothes and Fashion Consciousness in Japan and Korea,” Journal of Textile Engineering, Vol. 54, No. 1, 2008, pp. 9-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.4188/jte.54.9 [3] K. Ito, “Color Affection Produced by Two-Color Combi- nations Appearing in Fashion Magazines,” Journal of the Japan Research Association for Textile End-Use, Vol. 48, No. 11, 2007, pp. 32-41. [4] T. Nakamura, T. Sato and K. Teraji, “Arrangement of Co- lour Image Words into the Non-Luminous Object Colour Space,” Journal of Color Science Association of Japan, Vol. 18, 1994, pp. 10-18. [5] X. P. Gao, et al., “Analy sis of Cross-Cultural Color Emo- tion,” Color Research and Application, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2007, pp. 223-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20321 [6] L. C. Ou and M. R. Luo, “A St udy of Color Emotion and Color Preference. Part I: Color Emotions for Single Col- ors,” Color Research and Application, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2004, pp. 232-240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20010 [7] X. P. Gao and J. H. Xin, “Investigation of Human’s Emo- tional Responses on Colors,” Color Research and Appli- cation, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2006, pp. 411-417. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20246 [8] J. H. Xin, K. M. Cheng, G. Taylor, T. Sato and A. Han- suebsai, “Cross-Regional Comparison of Color Emotions. II. Quantitative Analysis,” Color Research and Applica- tion, Vol. 29, No. 6, 2004, pp. 458-466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20063 [9] Shirley Willet Color Codification. http://home.earthlink.net/~smwillett/color of emo tions.html [10] A. Naitou and S. Kobayashi, “A Dressing Image and a Color Effect of Women’s Suits,” Journal of the Japan Research Association for Textile End-Use, Vol. 43, No. 10, 2002, pp. 52-62. [11] C. F. Boyatzis and R. Varghese, “Children’s Emotional Associations with Colors,” Journal of Genetic Psycholo- gy, Vol. 155, 1994, pp. 77-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20063 [12] L.C. Ou, M. R. Luo, A. Woodcock and W. Angela, “A Study of Colour Emotion and Colour Preference. Part II: Colour Emotions for Two-Colour Combinations,” Colour Research and Application, Vol. 29, 2004, pp. 292-298. [13] A. C. Moore, A. K. Romney and T. L. Hsia, “Cultural, Gender, and Individual Differences in Perceptual and Semantic Structures of Basic Colors in Chinese and Eng- lish,” Journal of Cognition and Culture, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2004, pp. 1-28. [14] T. W. Whitfield and T. J. Wiltshire, “Color Psychology: A Critical Review,” Genetic, Social, and General Psy- chology Monographs, Vol. 116, No. 4, 1990, pp. 385- 411. [15] H. Bless, G. L. Clore, N. Schwarz, V. Golisano, C. Rabe and M. Wölk, “Mood and the Use of Scripts: Does a Happy Mood Really Lead to Mindlessness?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 4, 1996, pp. 665-679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/col.20063 [16] R. J. Davidson, D. C. Jackson and N. H. Kalin, “Emotion Plasticity, Context and Regulation: Perspectives from Af- fective Neuroseience,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 126, No. 4, 2000, pp. 890-909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.890 [17] K. C. Klauer and J. Musc h, “Affective Priming: Findings and Theories,” In: J. Musch and K. C. Klauer, Eds., The Psychology of Evaluation: Affective Processes in Cogni- tion and Emotion, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, 2003, pp. 7-49. [18] J. R. Stroop, “Studies of Interference in Serial Verbal Re- actions,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 18, 1935, pp. 643-662. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0054651

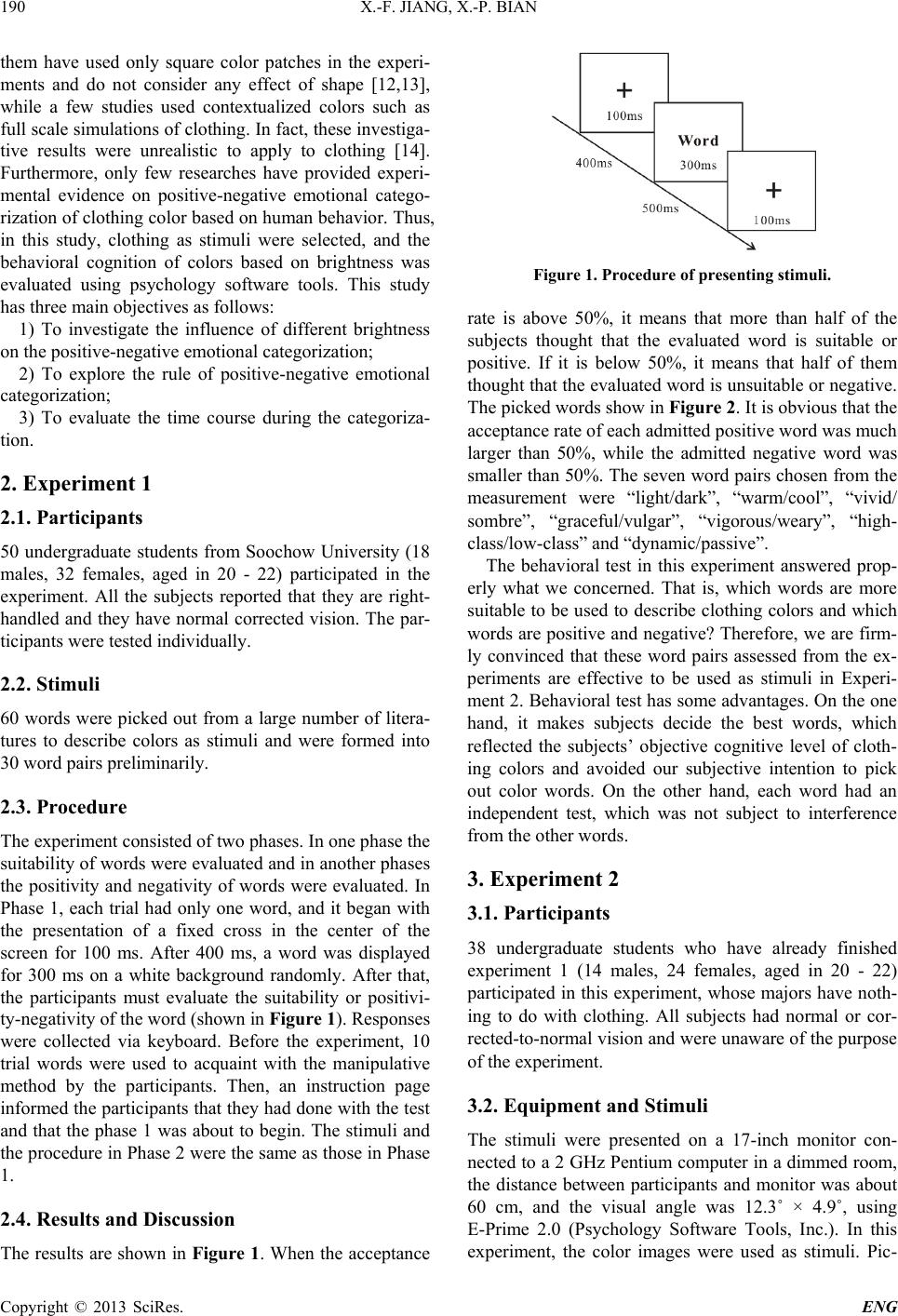

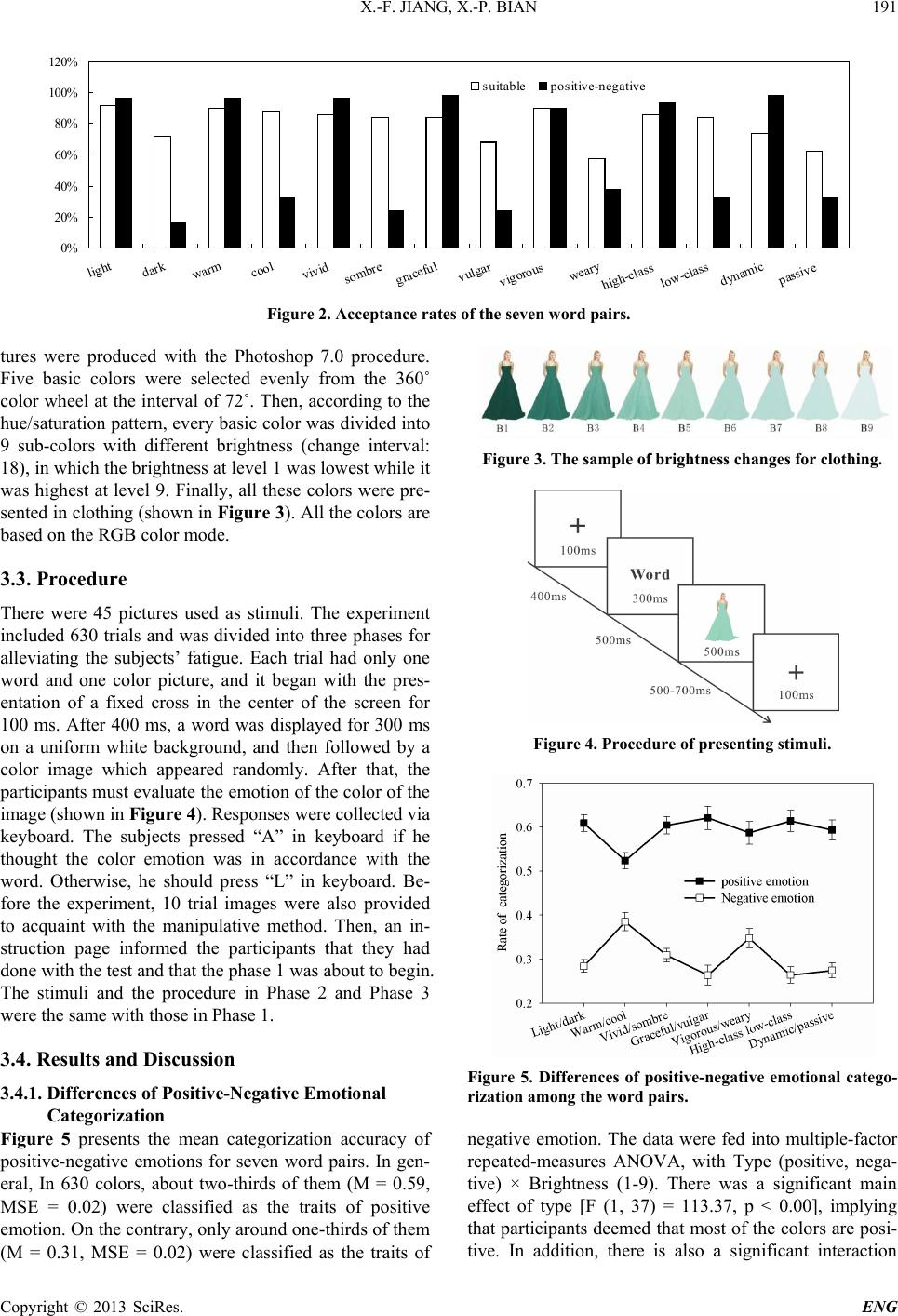

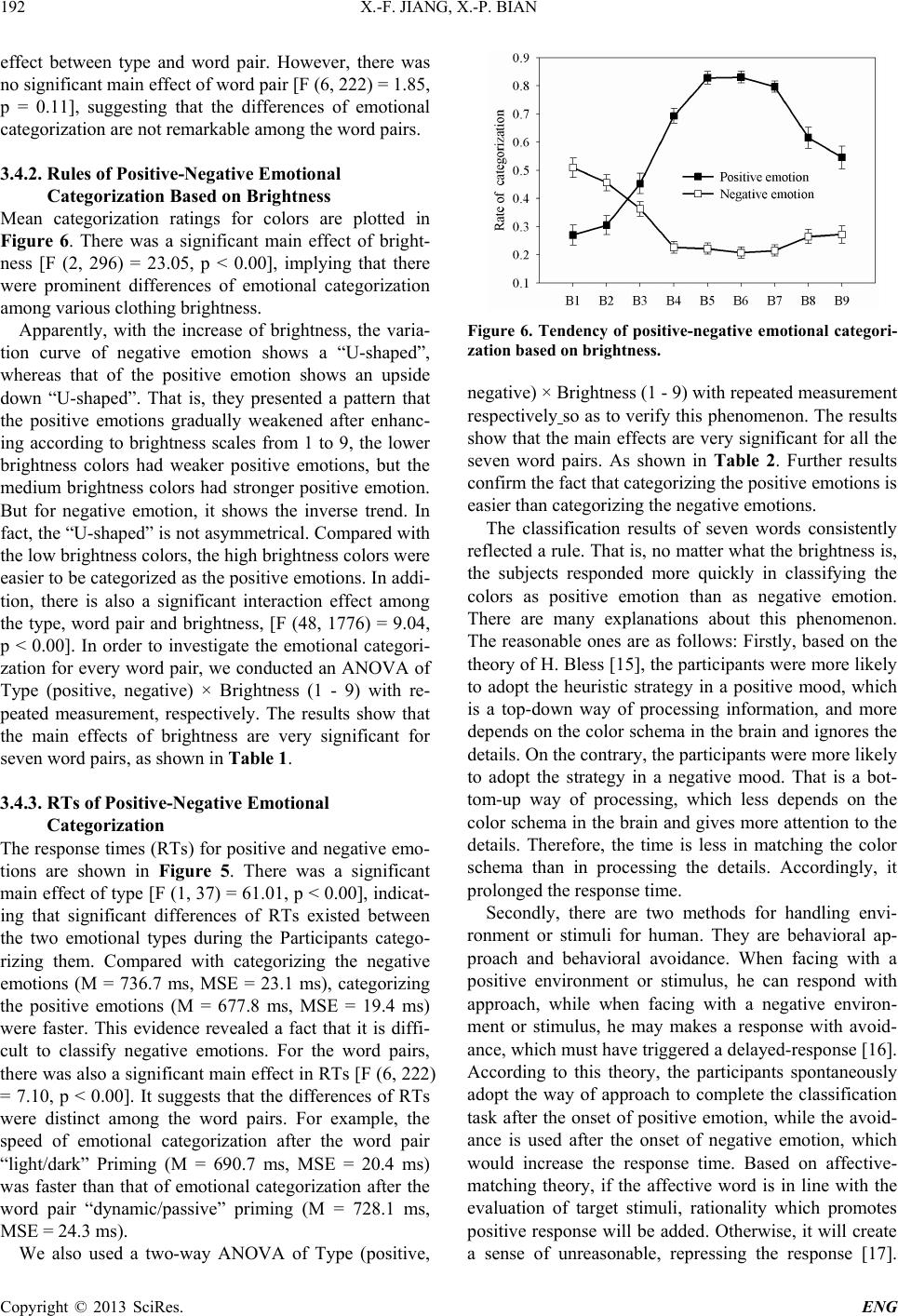

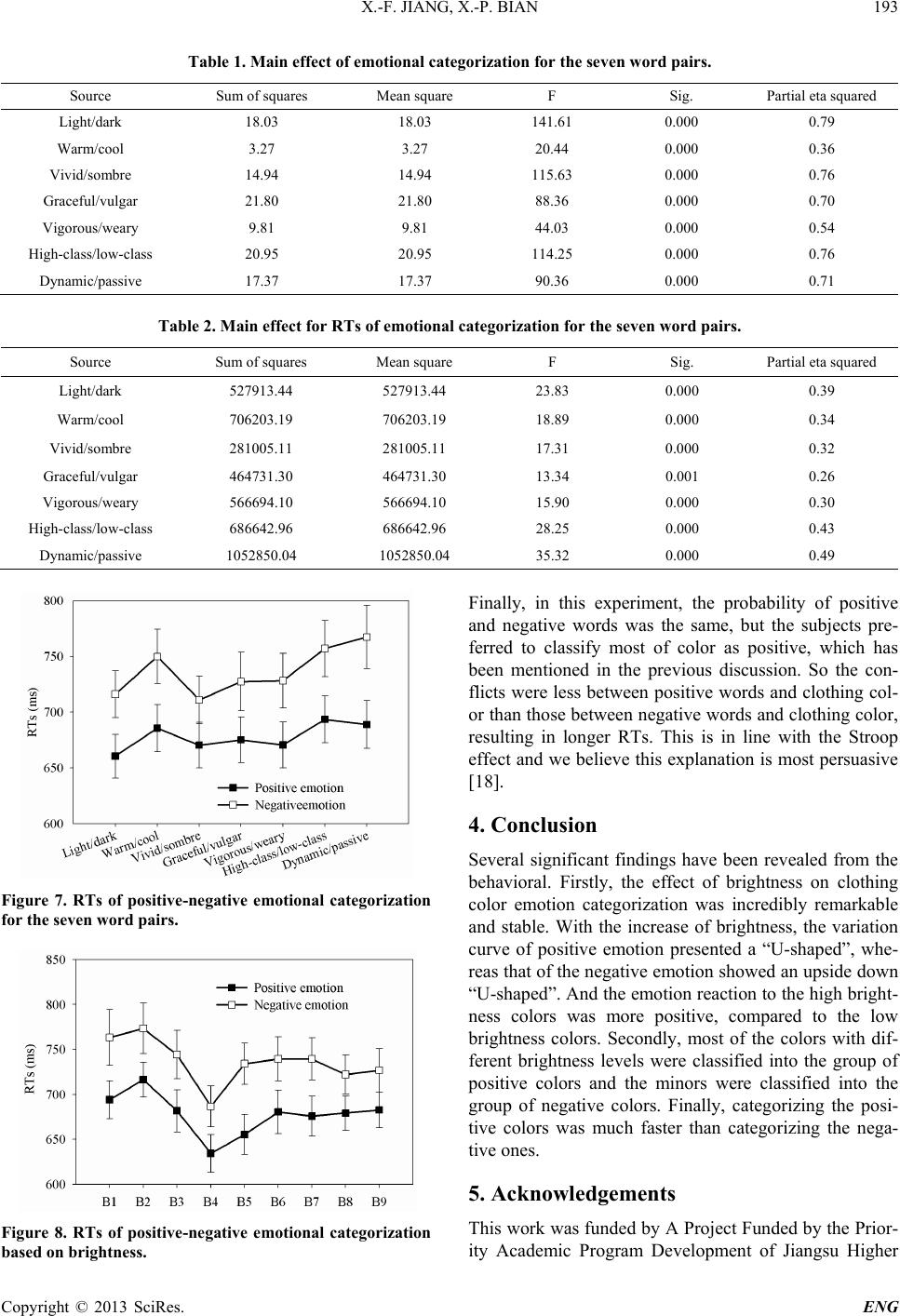

|