Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.10A, 61-71 Published Online October 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.410A010 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61 Continued Education to Integrate the Educational Laptop: Reflections on Educational Practice Change Shirley Takeco Gobara1, Dirce Cristiane Camilotti2 1Instituto de Física, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Cam po Grande, Brazil 2Núcleo de Tecnologias Educacionais Regional, Secretaria de Educação do Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Brazil Email: stgobara@gmail.com, dcamilotti@gmail.com Received August 28th, 2013; r evised September 28th, 2013; accepted October 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Shirley Takeco Gobara, Dirce Cristiane Camilotti. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the ori gin al work is properly cited. This paper presents the analysis and reflection of continuous formation for the use of educational laptop by teacher, and is held in the context of the implementation of the Project one computer per student (PROUCA), a pilot project-phase-II, in one of the public schools of the city of Terenos, MS, Brazil. This is a qualitative research of a case study type conducted from the analysis of the plans lesson made by two teachers throughout the training provided for the use of educational laptop, of the interactions with the tutor during training and information obtained in interviews semi-structured realized after training. The results suggest that the training contributed to the appropriation of the knowledge concerning the use and handling of the laptop features related to technical and pedagogical aspects and promoted the reflection on practice. The analysis showed that there was an increase in teachers’ planning, related to the content worked in the Modules and in the interactions with the tutor, but it was not enough to cause significant change in the pedagogy of theirs classroom practices, highlighting the need for continuing training with situations that prioritize the discussions of teachers’ pedagogical conceptions. Keywords: Continuing Education; Educational Laptop; Reflective Practice Introduction The use of computers in primary and secondary education has been happening in Brazil since the 1980’s and the purpose of its inclusion was, and still is, to promote student interaction, help the teaching and learning process, promote digital inclu- sion and democratize the access to information. In this sense, the computerization program of Brazilian pub- lic schools reaches to most basic education schools, because they have at least one computer lab provided by the initiative of the Ministry of Education—MEC. After several years of in- vestment in projects for deploying technology rooms in public schools, in April 1997, MEC created the National Educational Technology—Proinfo, regulated by Decree 6300, of December 12, 2007, to promote the pedagogical use of Information and Communication Technology—ICT, at public primary and sec- ondary education networks (Adams, 2000: p. 139). To partici- pate in this program, MEC has established an agreement with State governments offering computers and installing computer labs in public schools of basic education and, in return, local governments are responsible for the infrastructure of schools, installation and opera ting equi pment. Besides the presence of computers in technological rooms, in 2005 the project One Computer per Student—OCS was pre- sented to the Brazilian Government and, in 2006 the first phase began, which was Pre-pilot, and developed in five public schools from five Brazilian states. After this stage, in 2010 it moved to the second phase, Pilot Project, with the participation of several public schools in every state of the country and pro- ject OCS became One Computer per Student—PROUCA1, coordinated by MEC, which besides maintaining the purpose of integrating students in the information society, brings to the Brazilian educational context the ability of each student, from public schools participating in this program, to have an educa- tional laptop, which causes significant changes in the school and in the classroom. As a consequence, these changes require re-planning actions and developing new strategies that involve the whole school and local community, not only teachers and students. The presence of these laptops in schools enables the inte- grated use of technological resources by the student, articulat- ing global and local situations with access to new cultural con- texts. In addition, this feature contributes to the construction of new knowledge and new opportunities for the majority of stu- dents who were practically restricted to using only textbooks. Brazilian public schools generally have only one computer lab, limiting the use of this feature by many students. However, using these resources in the school context does not mean an improvement on the teacher practice or in the educational activities. It is necessary to integrate these tech- nologies into the school curriculum, providing support for in- novative and meaningful educational experiences (Almeida & Valente, 2011). From the point of view of the learning process, the insertion 1Program’s abrevia ti o n in Portuguese.  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI of computers in school can be influenced by different ap- proaches, among which Almeida and Prado (2011) highlight in the constructionist ideas discussed by Papert (1984, 1990). In this first approach, the learner builds knowledge when he uses the computer to produce a performance of his interest, actively participating in his learning. Opposed to this approach, there is the instructional approach that maintains a teacher-centered pedagogical practice, in which the computer is used only as a way to convey information to the student (Valente, 1998). For the implantation of technologies in education, following the perspective of construction in knowledge, that is, construc- tionist, two aspects should be observed according to Valente (2005): aspects related to technical and pedagogical knowledge, that should grow together, and aspects related with knowledge of specificities of each technology in educational contexts, demanding from teacher’s pedagogic experiences using those resources. This paper aims to present a reflection on the contribution of continuing education undertaken to use educational laptop from the analysis of the planning, assessments of lessons, interviews with the two teachers and the interactions between the tutors. The participating teachers of the training initiated in October 2010 to December 2011 in one of the schools of the city of Terenos. Evidences of innovating planning prepared by the teachers were also investigated. Context of Continuing Education for the Use of Educational Laptop In 2010, the phase II—Pilot, from the One Computer per Student Program (PROUCA2) started with the distribution of educational laptops for 300 Brazilian public schools, State and Municipal. The main objectives of PROUCA relate to the need for improving the quality of education, digital inclusion and integration of the Brazilian production chain in the manufac- turing process and equipment maintenance (MEC, 2010). In the State of Mato Grosso do Sul (MS) 19 schools are par- ticipating in PROUCA, nine located in the Municipality of Terenos (Total-UCA3), two in the State Capital Campo Grande and one school in the inner cities of the State (Anastácio, Costa Rica, Dourados, Ladário, Nova Andradina, São Gabriel do Oeste, Paranaíba and Ponta Porã). Figure 1 shows the location of the cities in the state. In 2010, phase II, pilot, from the One Computer per Student (PROUCA) began with the distribution of educational laptops to 300 brazilian public schools, state and municipal. The main objectives of PROUCA are related with the need of improving the quality of education, digital inclusion and integration of the Brazilian production chain in the manufacturing process and equipment maintenance (ECM, 2010). In the State of Mato Grosso do Sul—MS 19 schools partici- pated in PROUCA, nine located in the Municipality of Terenos (UCA—Total), two in the capital Campo Grande and schools in the inner cities of the State (Anastácio, Costa Rica, Dourados, Ladário, Nova Andradina, São Gabriel do Oeste, Paranaíba and Ponta Porã). Figure 1 shows the location of the cities in the state. One of PROUCA challenges is to promote the pedagogical use of the educational laptop; it is imperative to train teachers and administrators to focus on promoting their autonomy in the use of the laptop resource in the context and integrated into the pedagogical practice. Training for the use of the educational laptop in each participating State of this program was proposed and developed by Brazilian researchers and educators with recognized experience in the field, and belongs to the Working Group of Pedagogic Advi sory, WGPA4. According to PROUCA overall project, responsibility for teacher training was given to Local Institutions of Higher Education (IHE—Local) with the collaboration of the linked State and Municipal Technology Groups. In the State of Mato Grosso do Sul—MS, Federal Uni- versity of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) was the institution re- sponsible for training teachers who work in schools chosen to participate in this program in this State. The training was offered in distance mode, initially on the platform eProinfo5 and after in UFMS-Moodle6 platform, with a workload of 160 hours. The course was organized into four Modules. The methodology of training encompassed the technological, pedagogical and theoretical dimensions, with the proposed lesson plans with laptop use, related to the content of the Mod- ule, the implementation and evaluation of classes developed in the last module. The Module I was designed to the technological appropria- tion of Linux Educational Metasys7, the applications of the laptop and the virtual learning environment, with the propose of exploring the applications and programs of the laptop and the preparation of planning a lesson class. In Module II the use of Web 2.0 was discussed with emphasis on the blog, email and chat list and with a focus on interaction and the technical and pedagogical aspects. Module III was designed for teacher’s ac- tion in use of the laptop, with the goal of providing grants to plan and develop innovative teaching practices and encourage the structuring of networks of support and cooperation between students and teachers, addressing possible uses geared to ques- tioning, solving problems, challenges and collective writing. In this Module the participants prepared a lesson plan using the resources of the laptop from the pedagogical experiences dis- cussed, and executed that lesson plan and evaluated their results. In Module IV the proposed methodological work was planning and developing an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary project using the tools of the laptop. Continuing Education of Teachers: What the Experts Say It is indisputable that any innovation in education involves the training of teachers, which are a priority and strategic group to improve the quality of education (Belloni, 2001). So, to en- able the implementation of a program like PROUCA it is im- perative that teachers and other segments of the school in- volved (engineers and managers)—are trained before and dur- ing their performance using a laptop (Almeida & Prado, 2011). In order that the use of educational laptop occurs in a con- structionist perspective, it is necessary for educators to take 4http://www.uca.gov.br/institucional/projeto.jsp, access 30-01-2013. 5http://e-proinfo.mec.gov.br, last checked 30-01-2013. 6http://virt ual.ufms.br/, accesse d 30-01-2013. 7The operating system is Linux Metasys Classmate with educational ap- plications developed by the Brazilian company International Syst (http:// www. metas s.com.br Last checked 30-01-2013. 2Program’s abrevia ti o n in Portuguese. 3On the initiative of the Federal, State and Municipal governments, six Brazilian municipalities will have all their schools served, where they are called UCA T o tal. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63 Figure 1. Location of the cities participating in the PROUCA8. ownership of the technical knowledge (how to use the features offered by the machine) and of the knowledge about the educa- tional potentials related to the use of this technology, in other words, how to integrate these computer features in their every- day teaching practices (Cox, 2003). This involves changing the traditional role of the teacher, since it requires a transformation in the way it operates, going to play a role of facilitator of learning and environment organizer, real and/or virtual, to in- dulge the student to “learn with” and “learn about the thinking” (Almeida, 2000; Almeida & Meadow, 2011). However, putting into practice new knowledge in continuing education courses, leading to the reconstruction of pedagogical practice is not a simple task and immediate (Almeida & Prado, 2011). Furthermore, it is necessary that the teacher do periodi- cally reflect on their action (practice). Therefore, it is necessary that the teacher, not initiated on the use of these technologies, make a training covering the pedagogical, technological and didactic dimensions (Belloni, 2001; Schön, 1992). These dimensions include the necessary knowledge for the integration of technological resources in school. The pedagogi- cal dimension relates to the expertise of the teaching and learn- ing processes, the technological dimension covers the use of available technical means and implies the ability to make deci- sions about their use and didactic dimension in relation to spe- cific training and their implications in a given area of knowl- edge (BELLONI, 2001). 8http://www.brasil-turismo.com/mapas/mapa-ms.htm, last checked 26-08- 2013.  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI For Schön (1992) the development of professional knowl- edge is based on research and trial practice. The knowledge that emerges in practical situations, characterized as the unique uncertain ones and conflicting, can be described by observation and reflection on the actions. The theory of reflective practice, proposed by the author, is based on the ideas of reflection-in- the-action, reflection-about-the-action and reflection on reflec- tion-in-the-action. The reflection-in-the-action is triggered when the known methods are not sufficient to meet the unexpected situations that arise in this action and the teacher is urged to create new strategies to resolve the problems. This reflective process assists the creation of practical systematic knowledge in the reflection-about-the-action, which is the mental reconstruc- tion of the action to analyze it from observation, description and analysis, resulting in a new perception of the action and allowing the understanding of the practice and its reconstruc- tion. For the quality of the continuing education of teachers, ac- cording to Nóvoa (1991), the personal aspects, professional and organizational are considered fundamental. For him, for inno- vations to occur, in the teacher formation it must be considered: The personal development through critical-reflective training, the professional development, from questioning the independ- ence and professionalism of the teacher in front of the organs and bureaucratic administration and school development, which raises changes in school organization. Continued education linked to reflexive action of the teacher is only possible with the breakdown of traditional training processes, from the proposition of situations that favor teachers in training the awareness about the processes occurring in teaching and learning, understanding its practice and its trans- formation to the benefit of personal development, and profes- sional students (Almeida, 2000). For this “we need to enhance the knowledge and practices of teachers and work the implicit theoretical and conceptual, often unknown to them, in addition to establishing connections between pedagogical and scientific knowledge” (Almeida, 2000: p. 47). Thus, the formation of reflective teachers for computer use, according to Valente (1993), should provide the experience of situations where the computer is used as an educational re- source for the purpose of bringing the teacher to understand its historical role as an educator, to favor student learning with computer use and the methodology that best suits his working style. In this context, the formation capable of promoting the integration of laptop and transformation in the teacher’s peda- gogical action is one that is based in the articulation of theo- retical knowledge with practice, leading to reflection, and ena- bling research and contextualization of knowledge with a view to promote a transformation in the pedagogical action. Another important aspect of contextualized reflective train- ing are the interactions established between teachers-students, teachers-tutor and tutor-students. In reports of Prado and Al- meida (2003) they highlight the need for interaction and col- laboration between the subjects in training. In courses devel- oped in online environments, in distance mode, the interac- tions favor the development of “learning by doing” through the exchange of experiences and dialogue with one another, allow- ing participation in a constructive process that enables the rep- resentation of ideas and context and/or recontextualization practice (Prado & Almeida, 2009). In this process it is essential the role of the tutor who must conduct the pedagogic mediation towards the encouragement and motivation that drives the par- ticipants to learn, by creating strategies that conduct to reflec- tion on practice, clearance of actions taken and reconstruction of pedagogical practice (Masseto, 2000; Prado & Almeida, 2009). This requires the tutor’s approach in the context of the teacher in training in order to create situations for the use of the educational laptop to promote the contextualization of theory and reflection over the actions taken. The ideas of construction of knowledge, which grow con- tinuously in a “spiral of learning” and “virtual being together”, proposed in Valente’s research (2009) show the importance of the interaction between the tutor and the teacher participating in the training, as the pedagogical mediation for the reflective formation and contextual training. In the teacher’s training context, the tutor acts as a more experienced person who cre- ates circumstances for the construction of knowledge and for the reflection about teaching practice using the educational laptop. Research Methodology This is a qualitative research case study (Ludke & Adnre, 1986; Yin, 2010) held in a public school of the Municipal Terenos/MS. According to these benchmarks, the case study should address multiple sources of evidence, with a time of study not necessarily long, being constituted, in this study, of two cases, two teachers who are participants of this research. They were identified as teacher A (TA) and teacher B (TB). Teacher A has a degree with a specialization in pedagogy fo- cused in special education, working with the early grades of elementary school, she works as a teacher for 19 years and for the past two years has been using the computer to teach, how- ever sporadically. Teacher B has also a degree in pedagogy with a specialization in special education. She works as teacher of lower grades of elementary school for 16 years and works as a professor at the computer lab for three years. Procedure: Materials and Data Collection Data collection was carried out from monitoring, systemati- cally observing the plans prepared by these two teachers and interactions occurring with the tutor throughout the training offered by UFMS. The training took place from November 2010 to November 2011, in distance mode, in virtual learning environment (UFMS Moodle). At the end of each Module of the training, activities were proposed that required the construction of a planning of one or more classes using the laptop resources. In Module I this activ- ity was optional, in II it was mandatory and on III besides the planning it was required to run the class. The proposals were accompanied by guidelines for the organization of planning on items that included: objectives, methodology, resources and evaluation. The guidance was that there was consistency be- tween objectives and evaluation and that the methodology should be centered in the construction of knowledge with active students’ participation and achievement of activities exploring the laptop features. After the training an interview was conducted, semi-struc- tured, in order to investigate teachers’ perception about the contribution of training to use the laptop in their classes. These interviews were done from a script with ten questions and were audio taped and notes were taken during the interviews. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI Methodol og y for Data Anal ysi s The analysis of the planning Module I, II and III were carried out from the perspective of content analysis according to Bardin (1979), seeking evidence: the consistency between ob- jective and evaluation, in the proposed methodology with a focus on construction of knowledge by students articulated using laptop resources and innovation in the proposal and im- plementation of the lesson. The criteria adopted for the analysis of the lesson planning were based on the current proposals of constructivist teaching and learning as opposed to traditional instructive approaches. The coherence between the objectives and the evaluation was considered present on the analysis when the tools and evalua- tion criteria proposed were enough to verify that the learning objectives have been achieved. The methodology was ranked as constructionist when the proposed actions have focused on the construction of knowledge by the student using the laptop’s resources. The planned activities were characterized as innova- tive when they showed the reconstruction of pedagogical prac- tice from the integration of the laptop with the existing practice; this definition is derived from the interpretation of Belloni ideas (2003) and the observation of the presence of constructionist features (Valente, 1998; Papert, 1984, 1990). Interactions between the teachers and the tutor were also analyzed. For the analysis of the evaluation of the class’ devel- opment (Module III) were considered teacher’s reflections on possible changes suggested during the interactions between them and the tutor, after the execution of this class. After the training an interview was conducted, semi-struc- tured, in order to investigate the teachers’ perception about the contribution of training for using the laptop in their classes. These interviews were done from a script with ten questions and were audio taped and notes were taken during the inter- views. Results The results of the analyzes are presented in the same order in which the actions took place during the formation and study: planning, interactions with the tutor, evaluation of the teachers on the school run in Module III and interviews with the teach- ers. Analysis of the Planning To determine the categories of analysis, summarized in Ta- bles 1-3, the items proposed in the planning guidelines were observed. In the Module I planning TA shows no consistency between objective and evaluation because the evaluation pro- posal was insufficient to investigate whether the initial objec- tives of the lesson were achieved. The proposed methodology prioritizes activities of repetition, instructionism. In Module II it has been possible to observe elements that indicate a methodology focused on the production of the stu- dents and activities other than those traditionally held by it. In the context of the activities proposed by this teacher, the use of the blog, stated in the planning of Module II, is an innovative element, since it is an innovative resource in their practice prior to training. However, according to the criteria used in the anal- ysis, only this does not guarantees innovation in the proposed class, since their use is geared for access to information and not for the production and interaction of students. In Module III, all the evidence found, summarized in Table 3, suggests that there has been progress in scheduling, with con- sistency between objectives and assessment and a methodology that encourages students to seek knowledge in virtual and non- virtual sources and to apply it in concrete activities. The planning of teacher TB also shows an evolution, how- ever, this occurs precisely in Module III and not gradually as noted in the planning of TA. In Module I, the planning does not bring the description of the assessment, but proposes a method- ology centered on the student, through its active participation in Table 1. Analysis of the planning of Module I of the teachers A and B. Module 1 Investigated elements (categories) Teacher A Teacher B Consistency between objective and evaluation No. Objective: “To i d entify each letter by name.” Evaluation: “I t is necessary to assess the progress of children in different forms (of the game).” No. Objective: “To i d entify, demonstrat e and explain the fights know by the class; Recognise t h e differences, techniques and tactics; compare the technical characteristics.” There was no mention of the evaluation form. Constructionist approach methodology No. A game was used where children typed the letters ap pearing on the screen. “Identify the alphabet in a fun way.” Yes. “... prepare a short glossary containing the most used techniques and tactics.” “... students can socialize their findings, registering them as a modality that they researched.” Innovation in the proposed classNo. No. Table 2. Analysis of the pla nning from Module II of teachers A and B. Module II Investigated elements (categories) Teacher A Teacher B Consistency between objective and evaluation Yes. Objective: “Learn the proper writing of the words” Evaluation: “Held procedurally with the observation of correct words by the teacher and group participation for correction (collective).” No. Objective: “ T o identify al ph abet letters and short words” Evaluation: “It will be done individually through participation, interaction and student engagement.” Constructionist approach methodolog y No. “... to access the teacher’s blog and record in the notebook the figures posted there.” No. “... students will see the alphabet and short words and will have to type them correctly . ” Innovation in the proposed class No. No. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI Table 3. Analysis of Module III planning of teachers A and B. Module III Investigated elements (categories) Teacher A Teacher B Consistency between objective and evaluation Yes. Objective: “To allow the contact with different text styles in order to understand its structure and characteristics”. Evaluation: “It will be continued, noting the placement of the students, considering the oral and written produc t ion.” Yes. Objective: “Awaken the taste for reading and writing”. There was no mention of the Evaluation: “…will be observed and written and text production and the participation in the scheduled activities.” Constructionist approach methodology Yes. “…collective production of text on the l aptop using the text editor; …presentation of productions to other classrooms; ...comments on the teacher’s blog about the productions .” Yes. “The students will make their own productions using th e text editor and image; from their draws and productions students will make a collective production ; th ey will all present their production in the blog with images registration.” Innovation in the proposed class No. No. the activities. In Module II the elements that characterize the evolution of planning were not observed, but in Module III this teacher presents all the elements that indicate the improvement of the planning quality. Although the methodology observed in the planning of the Module III, from both teachers, encourages the search for knowledge in virtual sources using the laptops, their practice continues with strong instructional influences, with research activities, typing, copying text from the internet and games that emphasize repetition. Justified practice because, according to Moran (2007), the innovation occurs in a third stage of the technological learning, with the disruption of the traditional practices and full appropriation of the pedagogical, mainly in the implementation of new technologies in schools, for example, the laptop. Several authors claim that the use of these technolo- gies provides only significant changes, from innovative prac- tices, when promoting intentional change in the school to ease the curriculum organization and the teaching and learning process (Moran, 2007; Almeida & Valente, 2011). According to Belloni (2003: p. 4): “Innovation is driven by a desire, a willingness to change, the details of which will be drawing during the process to reach a finalized action, subject to observation and eval- uation. So, to better understand what pedagogical innova- tion is, it is necessary to consider it as a process that leads to an intentional completed action.” The stimulus to the production of individual and collective texts, the use of the blog to register the student’s activities and reviews of colleague’s productions are elements that were pre- sent in the teacher’s actions. However, during training, those activities were only proposed to meet a requirement of training, therefore, these are actions that didn’t exceed the initial pro- posal, indicating that there was indeed no innovation in the teaching practices. But it was observed that there was inten- tionality in the search for change during and after the training of these teachers, which consists in an important element to innovation, according to Beloni (2003). Analysis of Interactions of the Teachers with the Tutor Analyzes of interactions made by the tutor were restricted to the planning of Module II and III, that were mandatory training activities. In Module I, in which the posting of planning was optional, mediations were not conducted. Interactions between the tutor and teachers were conducted using the tool “Tasks” at the course environment and tutors were advised, initially by the staff, to conduct mediations throughout the course. Analyzes of tutor’s interactions about the plans were made following the same categories of analysis used in planning. In both modules, the plans prepared by teachers were posted and only later, after being checked by the tutor, interactions were carried out with suggestions of amendments, when neces- sary, to align them with the objectives of the training, without the requirement of posting a new planning. Due to the time for the development of the class proposed in the planning, it was not required to post the reworked plans. A new posting was only required when the initial proposal did not contemplate the use of laptop. In this way, to each planning there was an inter- active dialogue, except for the planning of Module III by TA for which there were three interaction moments. Interactions with Teacher TA During the interaction performed by the tutor on planning Module II, the positive aspects of coherence between the objec- tives and evaluation present in planning were emphasized, ac- cording to excerpts 1 and 2. Aspects of methodology and use of laptop resources and blog were prioritized pointing out the need to use the blog with emphasis on the active participation of the student and to stimulate production, highlighting the benefits of this type of activity for learning. Suggestions of activities char- acterized as constructionist were also made. “... Another important point is the evaluation process, which in your case has the participation of the students. This is very positive because from questioning and guidance they may real- ize the mistakes and you will check if your initial goals were reached”. (Excerpt 1, answer from the tutor about planning Module II from TA). “... consider focusing your method in the production per- formed by the students using the blog, this way, instead of reg- istering posts (simple) and make comments to the pictures. “(Excerpt 2, answer from the tutor about planning Module II from TA). The influence of this interaction can be seen in the evolution of the planning of Module III (Table 1), with the proposal of conducting activities that stimulated the production and interac- tion of students according to the guidelines of the tutor. Al- though TA has not responded to the tutor in the environment, their response occurred through actions in the preparation of a new plan that demonstrates that the interaction facilitated re- flection on pedagogical practice and rescheduling of classes with the laptop. In this sense, the training provided to the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI teacher the contextualization and de-contextualization of the pedagogical practice, which favored the occurrence of reflec- tion and to establish new understandings (Prado & Valente, 2002), resulting in a changing practice of her action. There were analyzed three feedbacks in the process of inter- action with the teacher about the planning of the Module. In the first it was asked to post a new planning in which the method- ology propose the use of the laptop resources from the guide- lines for the realization of the activity, as there was a need for modifications in relation to the planning initially posted, which did not include the use of laptop as it can be seen in excerpts 3 and 4. These changes were part of the conditions to conclude the planning and to begging the development of the class of Module III, who proposed the execution of activities using the laptop from a constructionist methodology with emphasis on student participation. “... although you mention the blog and the internet as a re- source to be used, in your methodology there are no actions/ activities with the use of this tool. Thus, consider reworking the activities using the laptop” (Excerpt 3, first response to the planning of the Module of TA). “... Here are some suggestions: The texts can be transcribed directly in the laptop’s editor, using the spell checker to review the incorrect words (this can be done in a group); Instead of publishing students’ productions in murals, use the blog as a disclosure way, posting texts and encouraging comments from students in the class or other classes. How are 1st year children, if necessary, may act as a scribe in the comments posted to the texts.” (Excerpt 4, first response to the planning of Module III of TA). From these changes it was held the post of planning exam- ined in Table 1, based on the guidelines contained in the first and second responses. In excerpt 5, still referring to the first interaction on the plan- ning of the Module III, there is also a lack of elements that indicate consistency between objectives and assessment in ac- cordance with the observation pointed out by the tutor on the items of the planning. “... Also noticed that your planning does not follow the pro- posed sequence (Identification, Content, Objective, Methodol- ogy and Evaluation). This sequence is important for the reader of our plan to understand the different steps of the proposed work” (Excerpt 5, first feedback from the tutor to the planning of Module III of TA). In the second feedback, the tutor noted that TA had posted a new plan that had been proposed by a colleague of the class and after the questioning of her own, it was asked a new schedule with the changes suggested in the first interaction, as shown in the excerpt 6. “... You did not have to post another plan, but just to make the adjustments in this. Before evaluating, just a question: You and the colleague developed the plan together (each with in its own class)...” (Excerpt 6, according to feedback to the planning of Module III of TA). In excerpt 7, of the third feedback, it is observed that the tu- tor emphasized the improvements in relation to the planning of the first posting and the coherence observed between objective and evaluation and a methodologies facing the use of the laptop with a focus on active participation of students, showing that the proposed changes were made in the first interaction. “... it was worth to keep the previous plan. The activity is quite interesting and the by the results already obtained, I be- lieve it will be very positive for the learning process. The use of laptop and your blog in activities that would previously have been made with other features, make lessons more interesting and encourages the participation of children...” (Excerpt 7, third response to the planning of module 3 of TA). The fact that none of the comments or suggestions forwarded by the tutor in Module II was incorporated into the plan in the first posting of the Module can be linked to the lack of habit of the teachers to periodically check the course environment. It is found in the records of the interaction Environment of this teacher that the access to the message of the tutor on the plan- ning Module II only occurred after the request of the posting of a new planning of Module III. This occurrence reinforces the idea that the guidelines contained in the interactions (feedback) provide the reflection and change of teaching practice regarding the organization of the planning and proposing activities focus- ing constructionist with the use of the laptop. In this context, the interaction provided the reconstruction of the meanings of the teacher, with the tutor playing the role of observer, mediator and organizer of the theory with the practice. This activity is essential so the long distance interaction, in a virtual environments, can have a meaning, from the monitoring, constant observation and intervention in the development of the teachers participating in the training (Almeida & Prado, 2009). Interaction with Teacher TB Two feedbacks were made for the planning of teacher TB, in respect to the second and third Module. According to excerpt 8, the feedback of planning on Module II, the tutor mainly em- phasized aspects of the methodology, because in this planning there is only the presence of activities in which students would access information. According to this planning analysis, Table 1, there is inconsistency between objective and assessment and the proposal does not present the innovative features of class. This caused and excessive preoccupation by the tutor to ensure the use of the laptop with constructionist approach, which eventually left the pedagogical aspects related to other items proposed on the planning in background. “... Just one note, try to think of activities whose methodol- ogy is centered on the production of the student using the tool (laptop and blog) in order to facilitate their learning...” (Excerpt 8, the tutor’s response to the planning of Module II of TP). It is important that the implementation of tutoring encom- passes the pedagogical, technological and didactic dimensions (Belloni, 2001), offering support for educational use and tech- nical knowledge, integrated to the didactic knowledge, to use the laptop resources. In addition to observing these dimensions, it is important that the tutor’s pedagogical mediation is per- formed with the purpose of creating conditions that favor the production of knowledge, with the interactivity being poten- tiating an interaction, embodied in action between people (Prado & Almeida, 2003). In excerpt 9, there is an emphasis on the feedback by the tu- tor on improving the quality of the planning of Module III in respect to the previous Modules, particularly in the methodol- ogy that encouraged the pursuit of knowledge by the student, which highlights the importance of guidelines contained on interactions performed to promote teacher reflection and to cause changes in their teaching. Regarding the planning items, the tutor suggested to intensify the use of the blog for interaction among students, beyond us- ing it only to record, because the proposal to use it only as an Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI online space for registration of the student does not allow ex- ploring the potential of this feature to promote interaction be- tween students and teacher. Therefore, it is important that dur- ing the training, teachers are encouraged to perform reflection and discussion on the specifics of each technology related to the pedagogical applications. According to Valente (2005) this is an important aspect to be observed on the implantation of edu- cational technologies, and “the educator should know what each of these technological facilities has to offer and how it can be explored in different educational situations” (Valente, 2005: p. 5). This knowledge is essential when planning activities us- ing the laptop, because depending on the content to be explored and the didactic objectives there are different applications of the laptop features. “... This ‘to do’ (focused on the production of the student) enables the development of autonomy and moments of collec- tive activities, as proposed, the reflection and development of attitudinal skills, as indicated in your goal... The last item of the objectives could be removed, since the use of these resources are forms/tools to achieve the goals listed previously; b) if you have feasible time, encourage students to review and analyze the productions of colleagues posted on the blog as a way to complete the work.” (Excerpt 9, response to the planning of the Module III of TP). In summary, the analysis regarding the plans showed that in- teraction between tutor and teacher resulted in improvements in planning. Suggestions and guidelines dispensed in the interac- tions of the tutor, feedback in Module II were considered at the planning of Module III. The tutor’s role regarding TB supports the idea that the primary role of the tutor is to guide the learn- ing process through interaction (Prado & Almeida, 2003). However, according to Prado and Valente (2002), it is essential that these interactions are recorded in the spaces (environment) of offline communication, as these records show the various levels of reflection that occur during the learning process. It can also be observed in interactions, the affectivity in the tutor-teacher relationship, through the enhancement of success and suggestions that stimulated a review of methodological and/or inappropriate concepts, as well as clarification of any doubts. According with La Taille and colleagues (1992) ideas, affectivity can be interpreted as something that drives actions and the interaction presupposes affection. The comparison of analyzes of interactions performed with both teachers and of plans elaborated shows that interaction between tutor and teachers was a key factor in the contribution of the formation and evolution observed. Especially in the planning of Modules II and III, due to guidance and suggestions of pedagogical use of the laptop and discussions of planned activities, such as continued monitoring of teachers in training in their locus of work: their school context. Analysis of the Evaluations of Teachers on the Implementation of the Lesson Plan in Module III In Module III, besides the planning and execution of the les- son, it was requested an evaluation of the developed class, where they should mention the positives aspects, the difficulties encountered and the changes made in relation to the initial planning. Analysis of the Evaluation of the Teacher A According to excerpt 10, on lesson evaluation, the teacher pointed problems related to the Internet and laptop and, from these difficulties, reflected and suggested alternatives to miti- gate them, making changes in the initial planning using the image editor to replace the use of the blog. However, this fea- ture does not offer the potential to perform the proposed activ- ity using the blog. “... difficulties in handling the laptop mainly because most kids could not connect (the laptop) to the internet. I would not use the internet, and would use another application, such as Tux Paint. It was a class where all the children participated enthuse- astically.” (Excerpt 10, evaluation class of the Module III of TA). Using a text editor, although relevant to not harm the class, would make unviable to achieve the objectives of Module II that proposes the utilization of Web 2.0 tools to promote the construction of knowledge. It also demonstrates the weakness in relation to pedagogical aspects inherent to the use of this resource and shows the importance of the teacher to know the potentialities and restrictions of the pedagogical resources of the laptop, in addition to the technical aspects, as advocated by Valente (2005). The teacher mentioned as a positive aspect of the class the enthusiasm of students when using the laptop resources, but did not mention aspects related to the learning process. This dem- onstrates the teacher’s view on the use of technological re- sources toward the mastery of technique and that the construc- tion of knowledge related to the pedagogical dimension of training were not yet consolidated, indicating that the teacher is still in the first stage of the technological learning cited by Moran (2007), where technologies are used to improve the performance of what was already done in the classroom. The alteration proposal mentioned by the teacher for the planning suggests that the performed formation is not enough to bring to comprehension that the use of technological resources should be associated and integrated to curricular contents and not only to the knowledge of the laptop tools. Analysis of the Evaluation of Teacher B Excerpt 11 shows that on the evaluation of TB there were difficulties mentioned about capturing the images produced by students and problems with the internet. With regard to the changes that she would do in relation to the initial planning, the teacher mentioned the use of another application suitable for her purposes to address the difficulties, which demonstrates the appropriation of technological knowledge related to the use of image editors from the laptop. The proposal of such modifica- tions agreed with suggestions mentioned in answers to the tu- tor’s interactive planning and demonstrates, as Valente (2005), that teacher’s technical knowledge should be related to the pedagogical knowledge, because without knowing the potential of the resources it is not possible to warrant the decision mak- ing in the classroom in respect to the teacher’s didactic objec- tives. Still, in excerpt 11, it can be observed that as TA, this teacher also mentioned as a positive aspect of the class a largest student interest, showing that the contribution of the laptop use for learning was not evaluated, an important element for the plan- ning of future activities by the teacher. “... the downside was the runtime classes and not having managed to capture the image of all laptops... The very slow internet connection in that day, interfered in the research and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI with the selection of the images of the tales. Choosing just one tool of the laptop as an example, the Kolour Paint... Students’ interest was immense.” (Excerpt 11, evaluation class of the Module III of TB). The analyzes of the evaluations performed by the teachers TA and TB suggest that the formation caused no reflection about the action on TA in relation to the objectives of the Mod- ule because it does not put forward proposals to amend the planning from the knowledge worked during the training. In contrast, there was a reflection on the part of TB demonstrated by the practical application of the concepts explored in the training. The changes proposed on the initial planning made by TB, suitable to difficulties for the development of the class and to the didactic objectives proposed, reinforces the evidence that there was reflection-in-action, while with TA this process did not occur satisfactorily, since the proposed solutions for the difficulties encountered were not appropriate to the lesson’s objectives. For Schön (1992), when the teachers do not find answers for unexpected situations, as the problems mentioned by the teachers during the development of lessons, reflec- tion-in-action is triggered, but knowledge from these responses is not formally understood. So for the systematization of the knowledge acquired during training activities conducted in the classroom, it is necessary the reflection about the action, whereby the teacher becomes aware, understands and recon- structs its practice. Analysis of the Interviews According to the information obtained in the interview sum- marized in Table 4, TA has a degree in pedagogy focused in special education, working with early classes of elementary schools, working as a teacher for 19 years and using the com- puter in class for two years, with the implementation of PROUCA and the beginning of training. TB has also a degree in pedagogy with specialization in special education. She has been acting as a computer teacher for 3 years and in the early classes of elementary school for 16 years. Before the training for the laptop use, TA had not participated in another training, she only organized meetings in the city network of schools where the monitor guided the exploration of laptop’s resources. According to her, these meetings contributed with suggestions of activities for the laptop with students, like games and typing. TB only participated in a basic course of computing (Windows applications) and after a few years began a course focused on the pedagogical use of technology (Project Development/Pro- info), but has not completed the course. They report that before the training they had difficulty han- dling the laptop by not knowing the tools, the classes being restricted to activities with instructional characteristics, such as typing ready texts, research based in copying information from the internet and games who favored repetition and trial and error. The use based in instructional activities may be associ- ated with the little technological fluency of teachers and the participation only in courses and workshops, which did not involve technical and pedagogical aspects of computer use, an important characteristic of teacher training (Belloni, 1998), as the ones focused on the pedagogical use of educational tech- nologies. When asked about the contribution of training to their peda- gogical practice, improvements of the pedagogical aspects of Table 4. Summary of interviews with teachers TA and TB on training. Items investigated Teacher A (TA) Teacher B (TB) Participation and contribution of other courses; There was no participation in other courses. Attended a b asic course in computer science (te chnical information). Instructions for use before tr ai ning; -Use in gaming and typing of words. -Using the internet for research. Difficulties in u sing the computer; -Difficulties in handling the laptop and comput er. -Difficulties in handling the tools of the laptop. Contributions training for pedagogical practice; -Improved pla nn in g and use of resources. -Improved pla nn in g , -Knowledge of the possibilities of using the laptop and -Decision-making at the time of development of the classes. Laptop use after training. Once a week for: -Typing wo rds; -Production of small texts; -Math games and -Research on the internet. Use frequently in: -Production of texts and problems, -Notes from class information, -Research on the internet and -Math games. Difficulties for laptop use after training. -Difficulty in use in math classe s f o cused on the production of the student. -Difficulties in operating system restrictions (slow). -Lack of mastery of some applications. Change in tea ching practice after training. Yes. Greater resources area of the laptop and went to work better content. Yes. Activities undertaken before the noteboo k and book are perform ed on the laptop, such as research and production of texts. Contributions training for pla nni n g. The suggestions discussed in the training were used in planning activities. Knowledge of planning items and loca- tions to seek suggestions for pedagogic al use of the laptop. Aspects of training that contributed to the acquisition of knowledge. Informati on content o f the Modules. Suggestions for pedagogical use of the laptop. Determination to carry out the proposed activities. Help and encouragement of responsible PROUCA the municip ality. Guidelines i n setting the course and the tutor. Interaction wit h colleague s. Help and encouragement of responsible PROUCA the municip ality. planning were pointed as well as the knowledge about the po- tential of the laptop and its applications. TB also mentione d that the training also contributed with knowledge that assists in solving some of the technical problems during class. TA re- ported that she struggles to work math content for not knowing applications for this purpose; TB mentioned the lack of master- ing some applications, such as KSpread and KLogo. These difficulties show that there was no satisfactory appropriation of knowledge of the Module I (technological appropriation) train- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI ing, associated with technical aspects of using the resources of the laptop, widely discussed in this Module. In the teacher’s speech and in the analysis of planning (Table 1) there is evidence that the pedagogical knowledge related to planning was constructed from the proposed activities. How- ever, only the pedagogical domain or only the technical knowledge is not sufficient for the effective deployment and integration of technology in school (Valente, 2005). It is neces- sary that such knowledge are together fulfilling the demands of each other so that all dimensions about the use of these re- sources are sufficient for the teacher to understand their poten- tial, as well as to incorporate them into their practice (Almeida, 2007). Teachers said that there was a change in pedagogical practice due to the acquisition of knowledge about the features of the laptop to work the curricular content. TA stated that she uses the laptop once a week, as agreed with the school board, in productions of texts, typing, gaming and internet. TB said she uses the laptop whenever it is needed, which comprises several times a week: for the production of texts, in problems, taking note of information, Internet searches and math games. Al- though this information shows that the there was acquisition of knowledge about the use of the laptop, they were not sufficient to provoke a change of effective educational practice which results in the integration of resources to curricular activities in innovative ways. This is more evident in TA’s testimony whose use is restricted to the scheduling once a week, with practices similar to those performed before the training, except for the production of texts. They also mentioned that the knowledge built during training contributed to the planning of using the laptop from the sugges- tions and approaches discussed in the Modules, which is con- firmed by performing activities such as problem solving and production of texts by TB. Although not mentioned by the teachers, examples of conducting collaborative and innovative activities, after training, at different times of the interview they mentioned that “no copy is made, but production by students”, which supports the idea that there is recognition that students learn by doing something that is meaningful with the computer. However, these ideas are not easily incorporated into practice and reinforce Almeida and Prado (2011) critics that only the training focused on the use of technology, which deals with the constructionist principles, does not guarantee that there will be change in the practice of teaching in line with such principles. It is necessary that the teacher understands these ideas based on theories that help to overcome the “intuitive level of action” (Almeida, 2007: p. 160) and help to produce knowledge that allows to feed pedagogical practices based on active student participation in the learning process. About the aspects that contributed to the acquisition of knowledge for the educational use of laptop during training, TA quoted the information available in the Modules, the tutor’s suggestions for pedagogical use of the laptop, her determination to carry out the proposed activities, the help and encouragement of PROUCA County responsible. Besides the assistance of the local responsible, TB mentioned the guidelines contained in the course environment, interaction with colleagues in school and guidance and monitoring of the tutor. These data show that the content and guidelines were important for the training and knowledge built and the approach of the three dimensions de- scribed by Belloni (2001) focused on contextualized training (Almeida & Prado, 2011), facilitated the understanding and learning of teachers and provided an opportunity to carry out practical activities from the discussed theory. Another aspect mentioned by the teachers and that deserves to be highlighted is the role of the tutor who, in the view of participants, not only exercised the role of information provider, but also of guide and partner of new discoveries and learning, profile that, according to Prado and Almeida (2003), can sti- mulate a different position of the teacher towards their stu- dents. It is also important to highlight the collaboration of the PROUCA County responsible who worked together with the school, playing the role of a classroom collaborator, which helped to minimize the resistance, the initial fear and difficul- ties regarding the use of resources of the laptop and the meth- odology of distance learning. Conclusion The data obtained from analysis of the plans and the inter- views were compared in order to ascertain the assistance of training for the use of the educational laptop and change in teaching practice. The analysis suggests that there is an im- provement of the planning done by TA and TB during training, especially in the consistency between objectives and assess- ment, and in proposing a methodology aimed at the construc- tion of knowledge by the student. These improvements are related to the content working on the Modules and feedbacks made by the tutor focusing on technical and pedagogical train- ing. Regarding innovative proposals, even if the activities of lap- top use have been different from the activities proposed for using the computer technology room, they are not characterized as innovative as the laptop is still used for performing tradi- tional activities. The tutor’s feedback to teachers is characterized by mentor- ing, interaction and encouraging reflection on practice in ac- cordance with the proposed activity planning, providing a cli- mate of trust and mutual respect, and also mentioned in the interviews, which stimulate teachers to reflect on the reworking of planning. Although the analysis points that there was an improvement of planning, from the acquisition of knowledge related to the use of the laptop, class evaluation and an interview with TA suggest that the training did not provide a reflection on her practice, as there was no effective appropriation of knowledge for the use of laptop tools discussed in the Modules. As for TB, the interview revealed that the training helped her to reflect on the changes in planning effective action on a proposal for (re-)planning. The contribution of the training to the observed changes re- sulted in two different profiles of teachers and was associated with the course proposal added to the suggestions and guidance from the tutor and the presence of the PROUCA responsible for the school, which served as a local collaborative institution for the study and implementation of the proposed activities. The analysis of the interviews showed that, after the training, the teachers continued using the laptop, but there is still a strong instructional character in the proposed activities that reproduce practices performed before deploying PROUCA, only with changes in the use of the resource, suggesting that the peda- gogical knowledge acquired has not been fully incorporated into their teaching practices. The results of this research highlight the need for continued Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70  S. T. GOBARA, D. C. CAMILOTTI Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 71 training for laptop use with situations that prioritize discussions of teachers’ pedagogical conceptions and emphasize the analy- sis of the use of different applications of the laptop in order to complement the training undertaken, because only such training seems to have been insufficient to raise awareness about the processes of teaching and learning and an innovative approach that will contribute to the change in the teachers’ pedagogic practice to use the laptop effectively contributing to improving the quality of teaching. REFERENCES Almeida, M. B. E., & Valente, J. A. (2011). Tecnologias e currículo: Trajetórias converg entes ou divergentes? (93 p). São Paulo: Paulus. Almeida, M. E. B. (2000). Informática e formação de professores. Coleção Informática para a mudança na Educação, Brasília (p. 123). Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação. Almeida, M. E. B. (2007). Integração das tecnologias à educação: Novas formas de expressão do pensamento, produção escrita e leitura. In: J. A. Valente and M. E. B. Almeida (Org.), Formação de edu- cadores a distância e integração de mídias (pp. 159-169). São Paulo: Avercamp. Almeida, M. E. B., & Prado, M. E. B. B. (2011). Indicadores para a formação de educadores para a integração do laptop na escola. In: M. E. B. Almeida, & M. E. B. B. Prado (Org.), O computador portátil na escola: Mudanças e desafios nos processos de ensino e apren- dizagem (pp. 34-48). São Paulo: AVERCAMP. Bardini. L. (1979). Análise de conteúdo ( 229 p). Lisboa: Edições 70. Belloni, M. L. (2001). Educação a distância. Campinas: Autores As- sociados. Belloni, M. L. (2003). A televisão como ferramenta pedagógica na for- mação de professores. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, 29, 287- 301. Belloni, M. L.(1988). Tecnologia e formação de professores: Rumo a uma pedagogia pós-moderna? Educação e Sociedade, 19 , 143-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73301998000400005 Cox, K. K. (2003). Informática na educação escolar. Campinas: Au- tores Associados. La Taille, Y., Oliveira, M. K., & Dantas, H. (1992). Piaget, vygotsky, wallon: Teorias psic o g enéticas em discussão. São Paulo: Summus. Ludke, M., & André, M. (1986). Pesquisa em educação: Abordagens qualitativas. São Paulo: EPU. Masetto, M. T. (2000). Mediação pedagógica e o uso da tecnologia (pp. 133-173). In: J. M. Moran, M. T. Masetto, & M. A. Behrens, Novas tecnologias e mediação pedagó g i c a. São Paulo: P apirus. MEC (Ministério da Educação) (2010). Projeto um computador por aluno. Brasília. http://www.uca.gov.br/institucional/projeto.jsp. Moran, J. M. (2007). A educação que desejamos: Novos desafios e como chegar lá. Campinas: Papirus. Novoa, A. (1991). A formação contínua de professores: Realidades e perspectivas. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro. Papert S., & Harel, I. (1990). Situating constructionism. In: Harel (Ed.), Constructionist learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Media Laboratory. http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html Papert, S. (1993). The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. New York: Basic Books. Prado, M. E. B. B., & Almeida, M. E. B. (2003). Redesenhando estratégias na própria ação: Formação do professor a distância em ambiente digital (pp. 71-85). In: M. E. B. Almeida (Eds.), Educação a distância via intern e t . São Paulo: PUC-SP. Prado, M. E. B. B., & Almeida, M. E. B. (2009). Formação de edu- cadores: Fundamentos reflexivos para o contexto da educação a distância (pp. 65-82). In: J. A. Valente, and S. B. V. Bustamante (Eds.), Educação a distância: Prática e formação do profissional reflexivo. São Paulo: Avercamp. Prado, M. E. B. B., & Valente, J. A. (2002). A educação a distância possibilitando a formação do professor com base no ciclo da prática pedagógica (pp. 27-50). In: M. C. Moraes (Eds.), Educação a dis- tância: Fundament os e p r á t ic a s . C ampinas: UN IC AMP/NIED. Schön, D. (1992). Formar professores como profissionais reflexivos (pp. 78-91). In: A. Nóvoa (Eds.), Os professores e sua formação. Lisboa: Dom Quixote. Valente, J. A. (1993). Formação de profissionais na área de informática em educação (pp. 114-134). In: J. A. Valente (Eds.), Computadores e conhecimento: Repensando a educação. Campinas/SP: Gráfica Cen- tral da Unicamp. Valente, J. A. (1998). Informática na educação: Instrucionismo x con- strucionismo. Publicações do campinas: NIED-UNICAMP. http://www.educacaopublica.rj.gov.br Valente, J. A. (2005). Pesquisa, comunicação e aprendizagem com o computador: O papel do computador no processo ensino-apren- dizagem (pp. 22-31). In: M. E. Almeida, & J. M. Moran. Brasília: MEC/SEED. Valente, J. A. (2009). O “estar junto virtual” como uma abordagem de educação a distância (pp. 37-64). In: J. A. Valente, & S. B. V. Bustamante (Eds.), Educação a distância: Prática e formação do profissional reflexivo. São Paulo: Avercamp. Yin, R. K. (2010). Estudo de caso: Planejamento de métodos. Porto Alegre: Bookman.

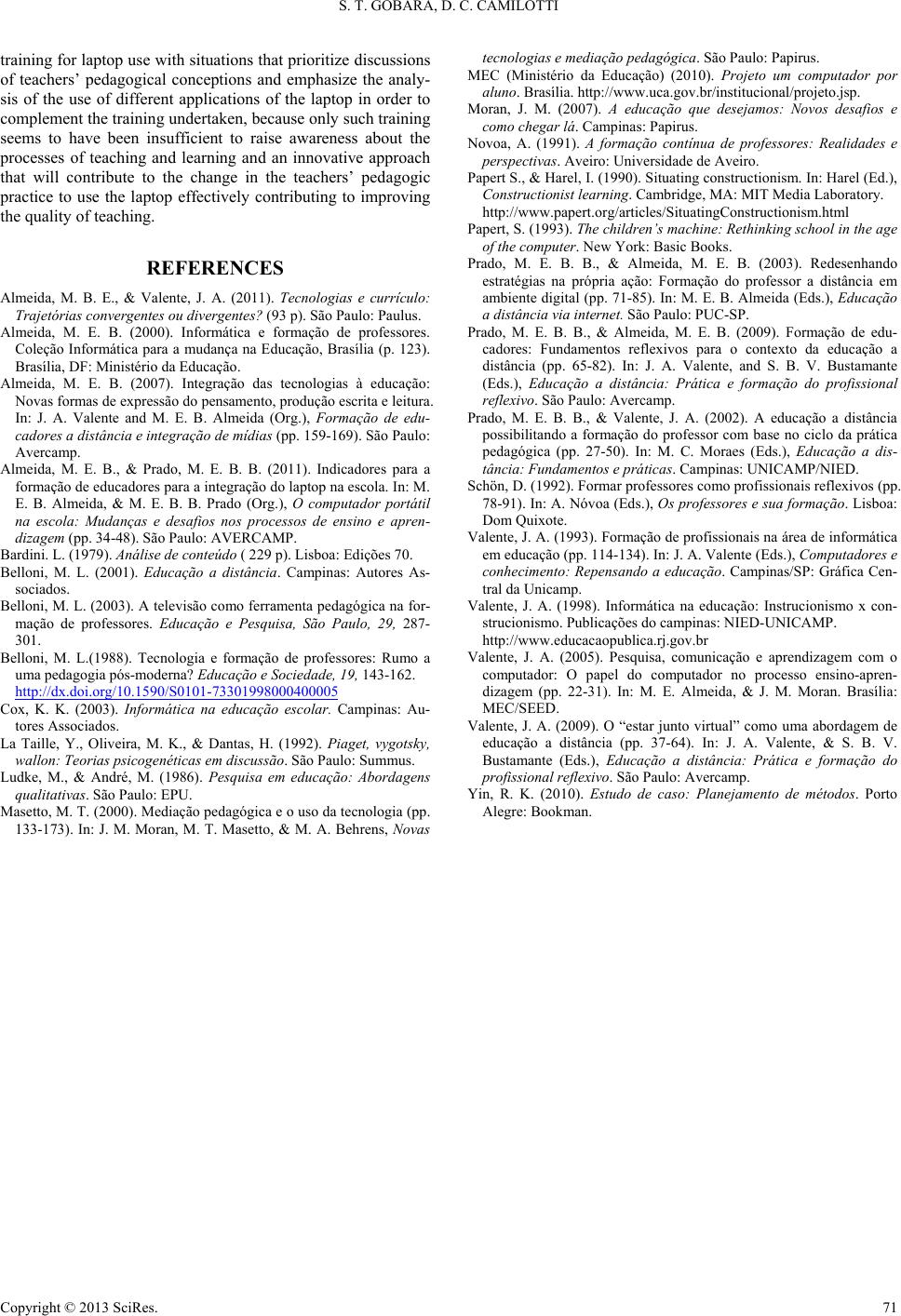

|