W. JOHDO 265

5. Welfare Analysis

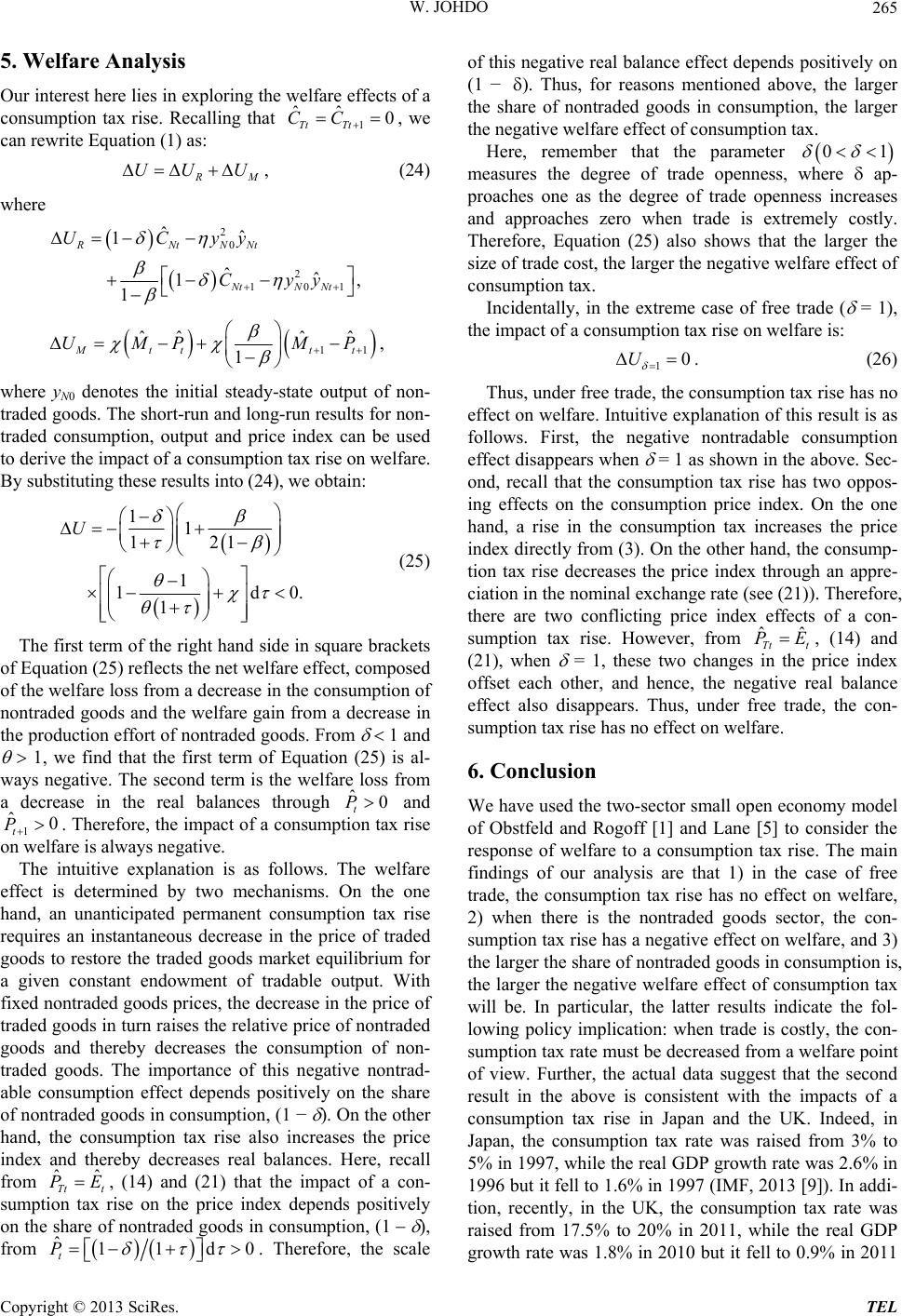

Our interest here lies in exploring the welfare effects of a

consumption tax rise. Recalling that , we

can rewrite Equation (1) as:

1

ˆˆ 0

Tt Tt

CC

M

UU U , (24)

where

2

0

2

101

ˆˆ

1

ˆˆ

1

1

RNtNNt

NtN Nt

UCyy

Cyy

,

11

ˆˆˆˆ

1

Mtt t

UMP MP

t

,

where yN0 denotes the initial steady-state output of non-

traded goods. The short-run and long-run results for non-

traded consumption, output and price index can be used

to derive the impact of a consumption tax rise on welfare.

By substituting these results into (24), we obtain:

11

121

1

1d

1

U

0.

(25)

The first term of the right hand side in square brackets

of Equation (25) reflects the net welfare effect, composed

of the welfare loss from a decrease in the consumption of

nontraded goods and the welfare gain from a decrease in

the production effort of nontraded goods. From

and

, we find that the first term of Equation (25) is al-

ways negative. The second term is the welfare loss from

a decrease in the real balances through and

1. Therefore, the impact of a consumption tax rise

on welfare is always negative.

ˆ0

t

P

ˆ0

t

P

The intuitive explanation is as follows. The welfare

effect is determined by two mechanisms. On the one

hand, an unanticipated permanent consumption tax rise

requires an instantaneous decrease in the price of traded

goods to restore the traded goods market equilibrium for

a given constant endowment of tradable output. With

fixed nontraded goods prices, the decrease in the price of

traded goods in turn raises the relative price of nontraded

goods and thereby decreases the consumption of non-

traded goods. The importance of this negative nontrad-

able consumption effect depends positively on the share

of nontraded goods in consumption, ( −

). On the other

hand, the consumption tax rise also increases the price

index and thereby decreases real balances. Here, recall

from , (14) and (21) that the impact of a con-

sumption tax rise on the price index depends positively

on the share of nontraded goods in consumption, (

),

from

ˆˆ

Tt t

PE

ˆt

P11

d0

. Therefore, the scale

of this negative real balance effect depends positively on

( − ). Thus, for reasons mentioned above, the larger

the share of nontraded goods in consumption, the larger

the negative welfare effect of consumption tax.

Here, remember that the parameter

01

measures the degree of trade openness, where ap-

proaches one as the degree of trade openness increases

and approaches zero when trade is extremely costly.

Therefore, Equation (25) also shows that the larger the

size of trade cost, the larger the negative welfare effect of

consumption tax.

Incidentally, in the extreme case of free trade

= 1,

the impact of a consumption tax rise on welfare is:

10U

. (26)

Thus, under free trade, the consumption tax rise has no

effect on welfare. Intuitive explanation of this result is as

follows. First, the negative nontradable consumption

effect disappears when

= 1 as shown in the above. Sec-

ond, recall that the consumption tax rise has two oppos-

ing effects on the consumption price index. On the one

hand, a rise in the consumption tax increases the price

index directly from (3). On the other hand, the consump-

tion tax rise decreases the price index through an appre-

ciation in the nominal exchange rate (see (21)). Therefore,

there are two conflicting price index effects of a con-

sumption tax rise. However, from , (14) and

(21), when

= 1, these two changes in the price index

offset each other, and hence, the negative real balance

effect also disappears. Thus, under free trade, the con-

sumption tax rise has no effect on welfare.

ˆˆ

Tt t

PE

6. Conclusion

We have used the two-sector small open economy model

of Obstfeld and Rogoff [1] and Lane [5] to consider the

response of welfare to a consumption tax rise. The main

findings of our analysis are that 1) in the case of free

trade, the consumption tax rise has no effect on welfare,

2) when there is the nontraded goods sector, the con-

sumption tax rise has a negative effect on welfare, and 3)

the larger the share of nontraded goods in consumption is,

the larger the negative welfare effect of consumption tax

will be. In particular, the latter results indicate the fol-

lowing policy implication: when trade is costly, the con-

sumption tax rate must be decreased from a welfare point

of view. Further, the actual data suggest that the second

result in the above is consistent with the impacts of a

consumption tax rise in Japan and the UK. Indeed, in

Japan, the consumption tax rate was raised from 3% to

5% in 1997, while the real GDP growth rate was 2.6% in

1996 but it fell to 1.6% in 1997 (IMF, 2013 [9]). In addi-

tion, recently, in the UK, the consumption tax rate was

raised from 17.5% to 20% in 2011, while the real GDP

growth rate was 1.8% in 2010 but it fell to 0.9% in 2011

Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL