Theoretical Economics Letters, 2013, 3, 31-39 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2013.35A2006 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/tel) Studying Economics Reduces Overexploitation in a Common Resource Experiment Nikolaos Georgantzis1, José Santiago Arroyo-Mina2, Daniel Guerrero3 1Department of Economics, Jaume I University, Castellón, Spain 2Department of Economics, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cali, Colombia 3Department of Economics, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cali, Colombia Email: ngeorgantzis@ugr.es, jarroyo@javerianacali.edu.co, dguerrero@javerianacali.edu.co Received July 24, 2013; revised August 30, 2013; accepted September 9, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Nikolaos Georgantzis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This paper studies the economical behavior of agents, who make decisions regarding the sustainability of Com- mon-Pool Resources (CPR). For this purpose, economical experiments are applied to simulate the yield of a CPR taking into account the influence of economical training on the learning process of individuals regarding their decisions for sustainability. Based on a non-cooperative game with simultaneous choices, the results of experiments show that after several rounds the existence of economical knowledge reflects a better learning process for making decisions regarding sustainability of CPR. Keywords: Common-Pool Resources; Non-Cooperatives Games; Learning Processes 1. Introduction Economic theory proposes a set of assumptions to ana- lyze the decisions that an agent makes. These assump- tions suggest that the agent has a set of preferences with consistent and complete information on relevant aspects of their environment. To understand the assumptions of behavior of an agent, Nash [1] suggests that the agent has unlimited skills that are used to estimate the best decision; in other words, to achieve his highest welfare and predict any kind of consequences that derive their decisions. In contrast, Simon [2] noted that the agent’s decisions are derived from conditions significantly different to the assumptions of economic theory. These conditions are defined as limitations in the choices of the agent. Such limitations are focused on the principle that agents at the moment of making decisions have incomplete knowledge of the context about a particular situation, they have lim- ited cognitive skills that impede them to process all available information to make choices, nor they can an- ticipate events that affect their decisions; these limita- tions define the concept of bounded rationality1, such as: 1) Limited and non-perfect knowledge about the environ- ment which the agent is into; 2) the agents face the incapa- bility to consider every alternative to solve a problem; and 3) the available information is impossible to assimilate. Referring to the analysis of market decision making, Bowles [5] argues that agents are adaptive and fallow to establish rules to minimize the costs derived from cogni- tive limitations when facing situations of the complex analysis, then the agents behave according to the context to determine whether a behavior is appropriate or not in a given scenario, referring themselves to the current state or to the experienced by another agent, deriving a proc- ess of transmission of information and establishing the motivations and incentives in decision making. From above, the baseline of this paper combines the results of Ostrom et al. [6], and Cardenas & Ostrom [7] according to the relevance for studying the behavior of the logics about individual and collective rationality of agents regarding the decisions of sustainability of CPR. Due to this reason, an economical experiment is devel- oped where a CPR yield is simulated allowing to analyze dilemma that the agent is into, deciding whether to yield the amount of CPR, which maximizes his private benefits, or to yield the amount of CPR, which maximizes the so- cial benefits of the group, he participates. 1The concept of bounded rationality emerges as an alternative to clas- sical rationality prevailing in the economic theory. Simon [3] shows that there are choice situations, explaining to encourage new develop- ments that challenge the classical rationality in economics. For exam- le, Plata & Mejia [4] show that situations of imperfect competition (oligopoly) and the expectations and uncertainty are good examples o bounded rationality. The structure of the paper that includes this introduc- tion is organized followed by Section 2 where is featured C opyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 32 the theoretical model for the designed methodology and the applied economical experiments. Next, Section 3 de- scribes the applied of the experiments and the procedures to conduct them. Section 4 shows the analysis and the interpretation of the results obtained for the conduction of the experiments. Finally, Section 5 is presented with some final comments. 2. Theoretical Model2 The proposed model performs the social dilemma of CPR yield, where the aggregated decisions of agents converge to Nash-Cournot equilibrium, even so to Wal- rasian equilibrium.3 According to Ostrom et al. [6], and Cardenas [8], where an agent decides to assign an effort level for CPR yield, considering also the yield decisions of the N addi- tional CPR’s users, therefore assume a maximizer agent i into a static scenario,4 having an objective function de- fined by his own productive effort level xi, besides the aggregated effort level from the others CPR users who interact with him. Hereby, the private benefit func- tion is defined as: 1 , N iij j Yxx (1) Focus on (1), it is assumed that when the private yield increases, the private revenue increases too. This condi- tion is defined for: 0 i i Y x Furthermore, it is assumed that the marginal revenues of private effort are decreasing, therefore: 2 20 i i Y x then, due to the resource rivality condition, when the ag- gregated yield increases, the private welfare decrees, it is so: 0 i j Y x Following above, it can be assumed that each agent has a maximum effort level ei, reflecting the decreasing marginal revenues of labor:5 2 1 2 ii i xax bx (2) In (2), a and b are positive parameters of agents pro- ductivity. Furthermore, 0, ii e. This function im- plies that the agent can yield up to the maximum sus- tainable yield level: MSY a xb which indicates the agent obtains positive marginal reve- nues; nevertheless, yield amounts larger than xMSY would provide negative marginal revenues. Considering the aggregated yield, and what each j agent does not yield, it is defined the private benefit objective function to maxi- mize: 2 1 1 2 N ii ijj j Yax bxex (3) In (3), the parameter represents the cost assumed by agent i caused by the externality imposed by the aggre- gated yield of agents. If it is assumed, that every single agent has same yield technology, and their endowments are equal, it is proposed yield capabilities symmetry, then e = ei, and defining (3) as: 2 1 1 2 N ii ij Yax bxnex j (4) where n is the amount of CPR user. In (4), each (player) agent i chooses a level of yield xi, looking for maximize his own private benefits, then: Na xb (5) In (5), it is assumed a strictly positive yield 0, Ni e. The expression (5) is a solution that de- pends on the parameters a and b, also on the externality cost parameter . This solution, as Ostrom et al. [6] pro- posed, does not take into count on the amount of CPR users, also is considered as the individual competitive solution. On other hand, it is proposed the social optimum6 by the expression: 22 1 2 ii i WYaxbxnen 2The theoretical model presented for the design of economical experi- ments is translated from Arroyo & Guerrero [9]. 3The Walrasian competitive equilibrium defines the prices such as a mechanism that coordinate the consumer individual actions, leading net demanded quantities to be equivalent to available supplied quanti- ties on market (Walras [10]). 4According to Gibbons [11], and Shy [12] assumptions, the agents have a complete information structure that allow them to have a ra- tional decision making in a simultaneous way, ergo the agents find a long term equilibrium where the resource yield is equal to the resource natural growth. The interested reader can find a broader explanation on Clark [13]. i x (6) 5Gordon [14] developed the model of open access is developed; this model indicates that natural resources face biologic adversities, in- cluding the extinction possibility. In this model, the effort level in- creases will bring decreasing marginal revenues of labor, and so, when the natural growth is exceeded, these revenues will be progressively derived in smaller yield levels. 6A social optimum or Pareto-efficient is an allocation of resources where every single agent enjoys his greatest welfare, given the utility function of others (Varian, 1998). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 33 In (6), it is expressed aggregated benefit of the CPR yield to every user. Assuming the maximizer agents, it is obtained: San xb (7) Taking into account (7), as long as more users are in- volved into the CPR yield the amount of xS decreases. Therefore, it is concluded by Ostrom et al. [6] that an amount n of users bigger than 1 (n > 1), will lead to xS < xN, and the associated social dilemma of CPR. 3. Experimental Design This experimental design studies the behavior of agents towards the learning in order to accomplish the benefits maximization considering the sustainability of CPR, ac- cording the suggested by Ostrom et al. [6] and Cardenas [8]. The solution presented in (8), defines the individual yield that maximizes the private benefits, i.e.: Na xb (8) In (8), is presented a: the revenue per yielded unit; b: the cost that players assume for the decreasing marginal productivity; : the cost of the externality imposed by the depletion of the CPR; and n: number of players. From Cardenas [8], it is suggested that a = 60, b = 5, = 20. There by, the yield that maximizes private benefit is de- fined by: 60 208 5 Na xb Indicating that player maximizes his benefits when he yields 8 units. Equation (7) presents the solution that defines the in- dividual yield that maximizes social benefit. Considering that in each group participate, a maximum of 5 players (n = 5), the obtained result is: 60 5(20)8 5 San xb Although, as pointed by Cardenas [8] the yield must be strictly positive, thereby the minimum possible yield is: 1 S x Having these two solutions, the set of possible extrac- tion of each player is within a discrete range between 1 and 8 complete units. Hence, each player will define the best strategy, considering the best possible strategies of other players. For those reasons, as a hypothesis to evaluate in this economic experiment, it is stated that: The level of knowledge in economic theory, and deci- sions of previous periods affect the economical behavior of players for sustainability of CPR. Specifically, the more level of knowledge in economics, the better learn- ing process regarding decision for CPR sustainability; therefore, the average yield decision xi of each player during rounds 6 - 10 of experiment must reduces for the learning gained by the player during rounds 1 - 5. The former hypothesis is funded on the changes of teaching methodologies of economics in the last 15 years, where it has switched from an individual training to co- operative learning groups. According to above, Bartlett [15] points out that this kind of methodologies is based on a structure those incentives competences on students to maximize their collective work in order to accomplish common goals. Likewise, Fox [16] assures that co-opera- tive learning obtained by students onto their basic courses allows every single student to look for beneficial results for the group, even so for himself. Finally, another major change in the method of teach- ing of economics focuses on the design and implementa- tion of experiments in class. To Noussir & Walker [17], the use of experiments in teaching of economics stimu- lates interest of the student, provides demonstrations of the principles of the subject in reality and reflects the limitations of the models taught in undergraduate courses. Additionally, as suggested Yandell [18], the application of experiments in class contributes positively to the learning experience, the interest and satisfaction of stu- dents. 3.1. Experiment Application7 The applied economical experiments recreate a lab in which individuals simulate the extraction of a CPR like fishing. They were performed at the Pontificia Universi- dad Javeriana Cali, and Universidad Santiago de Cali, Colombia, along the months of February and September 2011. Players observed in the experiment are: undergraduate students of Economy, Business Administration, Ac- counting and Finance, Law, Architecture, Psychology, and graduate students in Environmental Management and Sustainable Development and Environmental Education Master from both universities. The economical experiment includes a sample of 245 players. Experiments were conducted forming groups of five players, each with a monitor that supported in spe- cific situations. Before starting the game, players were presented an exhibition of the context of the experiment, the rules, also were explained that individual pay-offs depended on their own yield besides the aggregate of yield from your competitors. All pay-offs were paid in 7In Appendix A is shown the protocol, the suggested instructions to layers, the individual decision making formats and the table of points that were used in the experiment. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 34 monetary form.8 3.2. Experiment Instructions Each player was given a sheet where he should indicate each round, the number of individual CPR’s yield (e.g., number of fish caught) which player considered optimal. Additionally, it was given to each player a sheet where it was compiled individual and aggregated yielded amount of the group. Being a simultaneous non-cooperative game, only monitor knew the individual amount of each group member, therefore announcing the yielded aggre- gated amount within the group at the end of each round. Finally, it was provided to each player a table with pay-offs they would receive once the yielded amount by the group was announced. Each session of experiments was performed in 10 rounds. In each round each player simultaneously chose a yield level of xi CPR among 1 and 8. Therefore, the ag- gregated level had a minimum of 5, and a maxi- mum of 40 units. The pay-off received for each player in each round, as suggested by Ostrom et al. [6], and Cardenas (2010a), can be expressed by: ij wf xx i (9) where wi is the individual pay-off in each round, which included a minimum of 198 points, where xi = 1, and , which is the maximum possible amount of aggregated yield of competitors when every single yielded 8 units. Also, the maximum individual score of 880 points, obtained when xi = 8, , when each competitor yielded only 1 unit. 32 j x 4 j x 4. Results As already explained, the applied economical experiment studies the behavior of agents regarding the decision in favor of the sustainability of CPR, considering that a higher level of knowledge in economics reflects a better learning process for this kind of decisions. Particularly, experiment analyzes whether average yield decisions xi of each player during rounds 6 - 10 decreases due to the learning gained by the player during rounds 1 - 5. 4.1. Descriptive Analysis This economic experiment includes sample of 245 play- ers, who were asked their level of knowledge in eco- nomic theory, sex, age and years of schooling. The sam- ple includes 132 men, and 113 women players. Table 1 summarizes the information of the sample. Before showing the econometric analysis of the ex- perimental results, a chart is presented below in Figure 1 with the average extraction of players during rounds 1 - 5 (stage 1) and 6 - 10 (stage 2). The results suggest that average yield decisions of players are influenced by their initial periods as sug- gested by the work of Huck et al. [19], Rassenti et al. [20], and Fajfar [21]. Particularly, the results show that the average decrease from 4.94 units extraction during rounds 1 - 5 (formation of knowledge), to 4.91 units dur- ing rounds 6 - 10 (learning for sustainable yield deci- sions). 4.2. Economics Knowledge and Sustainability Decisions of CPR To analyze the behavior of the players based on the learning obtained in the experiment during rounds 1 - 5considering that more knowledge in economics theory reflects a greater commitment to sustainable yield deci- sions for CPR, it is defined that the average extraction xi obtained by each player for rounds 6 - 10 of the experi- ment, was less than or equal to the average extraction obtained during rounds 1 - 5. Thereby, each participant with his profile (other academic training than economics) will recognize extraction levels that allow him to get the highest scores in the experiment considering the sustain- ability of a CPR, as seen in Table 2. The results reported in Table 2 stands out two situa- tions: Table 1. Summary of information from fishermen. Average Min Max Years of Schooling 13.2 5 18 Age 26.5 16 65 Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. Figure 1. Average yield: Rounds 1 - 5 vs. Rounds 6 - 10. Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. The change from stage 1 to stage 2 is statistically significant at 5%. 8The accumulated score in the experiment was converted to a monetary figure in Colombian pesos, which is paid once the experiment ended. The average paid was $6.60 per player. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 35 Table 2. Average yield by groups. Groups of Students Rounds 1 - 5 Rounds 6 - 10 Economics 5.33 5.32 Accounting 5.13 4.83 Environmental* 4.58 4.54 Business Admin 5.11 5.06 Psychology 4.70 5.60 Architecture 4.07 3.80 Law 4.55 4.18 Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. *Student of post- graduate programs with orientation to natural resource sustainability. 1) All participants in the experiment except the group of psychology students follow the same trend of de- creasing in the average extraction xi obtained during rounds 6 - 10, compared to the rounds 1 - 5. Additionally, the performance of the group of law students turns out particular. The average extraction decisions of this group during rounds 6 - 10, rounds compared to 1 - 5 decreases 8.24%, showing a greater learning process with relation to their sustainable yield decisions CPR. This result is consistent with the hypothesis formulated for the expe- riment, due to the curriculum of law program includes courses in economics, which could facilitate the learning process in the experiment because the elements, instru- ments and methods of analysis that provides the training in economics.9 2) The group of psychology students did not follow the suggested behavior on the formulated hypothesis for ex- perimental design: the average yield decisions increased 19.15% in rounds 6 - 10 compared to rounds 1 - 5. In other words, the behavior of psychology students did not adjust towards sustainable yield decisions of CPR in rounds 6 - 10 of the experiment as the other participants did. This situation could be the result of the schooling curriculum of psychology, inasmuch as excludes assign- ments of economics theory, bounding the learning proc- ess in the experiment. Besides from the above results, it is interesting to ex- amine the behavior of players when is involved the schooling years variable in the analysis of learning proc- ess regarding sustainable decisions of CPR as is shown in Figure 2. This result suggests that in experiment, after 13.2 years of average schooling, extraction decisions will de- crease as years of schooling increase. Particularly, and as suggested by Becker [22], and Brock & Durlauf [23], the processes of human capital formation reward the agent Figure 2. Average yield and schooling years. Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. The change from stage 1 to stage 2 is statistically significant at 5%. who decides to participate in them, and society as a whole. Thus, the experiment evidenced that the higher level of education of participants, the better learning process regarding sustainable decisions of CPR (6 - 10 rounds during extraction average reaches 4.13 if 18 years of education). 4.3. Empirical Analysis Considering that applied economical experiment has transverse cutting units (players) with information that is observed during periods Ti (10 rounds of the experi- ment), a static model of panel data with conjoint regres- sion10 is presented: ',1,,,1 it ititi xeiNt T (10) As suggested by Baltagui [24], and Hsiao [25], this model identify the specific individual effects that are not included in the estimation, i.e., this model points out the effect that determinants appointed above might influence on the sustainability decisions of CPR. 4.4. Interpretation of Results The estimations of econometric model contrast the aver- age yield decisions of each player during rounds 6 - 10, with those obtained in rounds 1 - 5, considering the de- terminants already mentioned, focusing on the existence of economics theory training as shown in Table 3.11 The results show that the signs of the estimated pa- rameters in the model behave as expected. Thus, to vali- 10With the encouragement that the model consider all the assumptions that allow to prove empirically the theoretical hypothesis already men- tioned, it captures the non-observed effect in the model, from the in- clusion of a parameter for each individual in the regression as sug- gested by Baltagui [24], and Hsiao [25]. 11For convenience in the edition of the table is not displayed the infor- mation of each estimation by group of participants, however, each o the estimated models has a R-squared between 0.90 and 0.98, i.e. the estimations are correct. 9This result is consistent to suggested by Bartlett [15] due to the stu- dents of disciplines related to economics have within their curriculum courses of Microeconomics and Game Theory, which are based on environments of cooperative learning that allow individuals to learn more and more efficiently. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 36 Table 3. Economics know ledge and learning re garding CPR sustainability. Players Coef. p-value [95% Conf. Interval] Economics 0.15933 0.000 0.134146 0.184527 Accounting 0.11399 0.000 0.095092 0.132889 Environmental* 0.09709 0.000 0.091509 0.102688 Business Admin 0.12552 0.000 0.116807 0.134247 Psychology 0.12683 0.000 0.112492 0.141174 Architecture 0.10927 0.000 0.087832 0.130724 Law 0.12225 0.000 0.097773 0.146742 Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. *Student of post- graduate programs with orientation to natural resource sustainability. date the hypothesis that behavior of players in the ex- periment regarding sustainable decisions of CPR is in- fluenced by the level of knowledge in economics theory of participants. Particularly, it is accepted that the aver- age extraction xi during rounds 6 - 10 decreases due to learning gained by the player during rounds 1 - 5 consid- ering the level of knowledge in economics theory of the participants. Particularly, the result of economics student group (increase in 15.93% during rounds 6 - 10 of the experi- ment) confirms that more knowledge and training in this discipline influences the sustainable decisions of CPR learning process because the methods of teaching of the discipline enhance the criteria for judging the suitability of these sustainable choices.12 Additionally, the other groups of students who parti- cipated in the experiment reflect a similar behavior as a function of the effect of the level of knowledge in eco- nomics on its preservation decisions by CPR. Specifi- cally, their sustainability decisions for CPR during rounds 6 - 10 experiment 12.05% increase on average. Regarding the performance of the players when con- sidering their ages, education and sex, a table is pre- sented summarizing the results of the estimated model according to econometric methodology described above. Table 4 shows that the signs of the estimated parame- ters for the selected econometric model behave as ex- pected. Regarding the educational level, the result shows that for each additional year in the level of schooling of participants compared to the average schooling years of the sample (13.2), extraction decisions for the sustain- ability of RUC increased 8.4%, confirming that recorded in Becker [22], and Brock & Durlauf [23] for the proc- esses of human capital formation. Table 4. Panel data model with conjoint regression. Lyield13 Coef. p-value [95% Coef. Interval] Age 0.0012188 0.061* −0.003519 −0.006956 Schooling0.0847114 0.000 0.0707961 0.0986267 Sex 0.2579147 0.000 0.1739859 0.3418438 Source: Proper estimations from applied experiments. *Statistically signifi- cant at 10%. The others at 5%. Furthermore, although the age variable turns out to be statistically significant, it can be noticed that having more or less years compared to the average age of the participants, only influences a 0.12% on sustainable de- cisions of CPR. In other words, if a player is 1 year older than the average age of the sample (26.5 years), he is not guaranteed that learning process for sustainability deci- sions of RUC is actually more significant. Therefore, this result suggests that the processes of teaching and training in environmental education could focus on all age groups of society. Regarding the results of the sex variable, the result shows that men learned faster than women in rounds 1 - 5 in 25.8%, and therefore they adjust their sustainable decisions of CPR faster than women. 5. Concluding Remarks The objective of this paper is to study the behavior of agents when makeing decisions related to the sustainabil- ity of Common Pool Resources (CPR). For this purpose, an economical laboratory was recreated where agents simulated the extraction of CPR as fishing. The results presented in this study are a product of economical ex- periments applied to 245 undergraduate students in eco- nomics, accounting, business administration, architecture, psychology, law and graduate students in environmental management and master in environmental education, belonging to two universities in the city of Santiago de Cali, Colombia. Based on a non-cooperative game with complete in- formation and simultaneous choices, the results of the experiment show that after several rounds the agents have some kinds of learning abilities for sustainable deci- sion of CPR as suggested by Ostrom et al. [6], and Clark [13]. Specifically, the theoretical hypothesis proposed re- garding the influence of economics and teaching and training on sustainability decisions of RUC is accepted. Particularly, it is validated that the existence of a higher level of knowledge of economic theory reflects a better learning process for sustainable decisions of CPR. Thereby, it is demonstrated that average yield xi decision of the group of students with higher levels of knowledge in economic theory, decreased during rounds 6 - 10 of 12This kind of behavior suggests that the level of expectations of play- ers combined with their expected choice error, behavior of CPR sus- tainability are formed: “If people give importance to a particular value associated with the conservation, one can expect a positive assessment to the activities that promote conservation. Economists say that indi- viduals gain greater utility” (Lynne et al. [26]). 13The model contains a sample n = 245, R2 = 0.9433, F = 0.000. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL 37 the experiment for the learning obtained by themselves during rounds 1 - 5, guarantying the propose by Huck et al. [19], and Fajfar [21], who claim that agents have a learning curve for their decisions. Finally, and as a suggestion, future designs of experi- mental and behavioral economics related to natural re- sources and sustainability of CPR should take into ac- count: 1) Including different skills from those that eco- nomic theory provides, i.e. studying the decisions of agents based on structures unlike cost analyses and bene- fits. 2) Studying the behavior of agents facing unex- pected as global warming, since this type of phenomena may affect the CPR’s. REFERENCES [1] J. Nash, “The Bargaining Problem,” Econometrica, 1950 Vol. 18, No. 2, 1950, pp. 155-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1907266 [2] H. Simon, “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice,” The Quaterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 69, No. 1, 1955, pp. 99-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1884852 [3] H. Simon, “Rationality in Psychology and Economics. Rational Choice: The Contrast between Economics and Psychology,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 99, No. 4, 1986, pp. S209-S224. [4] L. Plata and I. Mejia, “Racionalidad Clasica o Raciona- lidad Limitada?” Archivos Jornadas de Epistemología Económica, Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires, 2010. [5] S. Bowles, “Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions and Evolution,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2004. [6] E. Ostrom, R. Gardner and J. Walker, “Rules, Games, and Common-pool Resources,” University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1994. [7] J. Cárdenas and E. Ostrom, “What Do People Bring into the Game: Experiments in the Field about Cooperation in the Commons,” Agricultural Systems, 2004, Vol. 82, No. 3, 2004, pp. 307-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2004.07.008 [8] J. Cárdenas, “Dilemas de lo Colectivo: Instituciones, Pobreza y Cooperación en el Manejo Local de los Recursos de uso Común,” Colección CEDE 50 años, Facultad de Economía, 2010. [9] S. Arroyo and D. Guerrero, “Determinantes de Decisiones Sociales Para Preservar Recursos de uso Común: Apli- caciones Experimentales Bajo un Modelo de Aprendizaje a la Cournot,” Journal of Management and Economics for Iberoamerica, in process, 2012. [10] L. Walras, “Elementos de la Teoría Política Pura,” Alian- za Editores, 1990. [11] R. Gibbons, “Game Theory for Applied Economists,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1958. [12] O. Shy, “Industrial Organization: Theory and Applica- tions,” MIT Press, Cambridge, 1995. [13] C. Clark, “Mathematical Bioeconomics: The Optimal Ma- nagement of Renewable Resources,” Wiley Interscience Publication, Hoboken, 1990. [14] H. S. Gordon, “The economic Theory of a Common Pro- perty Resource: The Fishery,” Journal of Political Econ- omy, Vol. 62, No. 2, 1954, pp.124-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/257497 [15] R. Bartlett, “Making Cooperative Learning Work in Eco- nomic Classes,” In: Becker and Watts (compilers), Eds., Teaching Economics to Undergraduates: Alternatives to Chalk and Talk, 1998. [16] E. Fox, “Introduction to Cooperative Learning,” In: R. T. Johnson and D. W. Johnson, Eds., Methods for Develop- ing Cooperative Learning on the Web, 2001. http://courses.cs.vt.edu/~cs4624/s01/docs/cooplearning.p df [17] C. Noussir and J. Walker, “Student Decision Making as Active Learning: Experimental Economics in the Class- room,” Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, 1998. [18] B.H. Baltagi, “Econometric Analysis of Panel Data,” John A. Wiley & Sons, New York, 1995. [19] S.Huck, H. Normann and J. Oechssler, “Learning in Cournot Oligopoly: An Experiment,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 1, No. 8, 1999, pp. 80-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00418 [20] S. Rassenti, S, Reynolds, V. Smith and F. Szidarovsky. “Adaptation and Convergence of Behavior in Repeated Experimental Cournot Games,” Journal of Economic Be- haviour and Organization, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2000, pp. 117- 146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(99)00090-6 [21] P. Fajfar, “Information and Competition in Cournot’s Model: Evidence from the Laboratory,” Social Science Research Network, 2006, p. 884231. [22] G. S. Becker. “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” The Journal of Political Economy, 1968, Vol. 76, pp. 169-217. [23] W. BrockandS. Durlauf. “Discrete Choice with Social Interactions,” Review of EconomicStudies, Vol. 68, No. 2, 2001, pp. 235-260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00168 [24] D. Yandell, “Effects of Integration and Classroom Ex- periments on Student Learning and Satisfaction,” In: I. S. University and P.-H. P. Co., Eds., Economics and the Classroom Conference, 1999. http://home.sandiego.edu/~yandell/idaho.pdf [25] C. Hsiao, “Analysis of Panel Data,” 2003. [26] G. Lynne, J. Shonkwiler, and L. Rola. “Attitudes and Farmer Conservation Behavior,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1988, pp. 12-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1241971  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 38 Appendix A. Protocol of Experiments The sessions of economical experiments were conducted as follows: Appendix A1. Information Session This session begins with the explanation about what is a Common-Pool Resource CPR. Following, several exam- ples of these natural resources are presented, then it is explained the concepts of rivalry and exclusion. There- fore, the present is introduced and each participant de- cided whether or not to participate. After forming groups of 5 players the context of the game is presented, the formats of individual choice and points are provided to players (see Appendices B and C), the rules are ex- plained making it clear that the game do not allow inter- actions between players, and finally how to get individ- ual score. In this session, the players were notified if the pay-offs were going to be paid with money or academic incentives. After the introduction, three rounds of prac- tice were conducted for players to become familiar with the dynamics of the game. Appendix A2. Application Rounds 1 - 10 It allowed him to freely choose each player the number of units you want to extract the resource. Each player wrote on Individual extraction format the drives you want to play. The monitor was collecting group at the end of each round individual decisions of each player, with the encouragement of total extracted total power by the group, and then communicate them. Then each player scored his punctuation in dot format. This procedure was repeated until round 10. Appendix B. Individual Decision Table Player No Age Sex Years of scholling Rounds A: Individual Amount of Yield B: Aggregated Amount of Yield of Group C (B - A): Aggegated Amount of Yield from other participants D: Score Practice 1 Practice 2 Practice 3 1 2 3 10 Total Appendix C. Individual Score Table My own amount of yield Aggregated amount of other participants 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 4 758 790 818 840 858 870 878 880 5 738 770 798 820 838 850 858 860 6 718 750 778 800 818 830 838 840 7 698 730 758 780 798 810 818 820 8 678 710 738 760 778 790 798 800 9 658 690 718 740 758 770 778 780 10 638 670 698 720 738 750 758 760 11 618 650 678 700 718 730 738 740 12 598 630 658 680 698 710 718 720 13 578 610 638 660 678 690 698 700 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  N. GEORGANTZIS ET AL. 39 Continued 14 558 590 618 640 658 670 678 680 15 538 570 598 620 638 650 658 660 16 518 550 578 600 618 630 638 640 17 498 530 558 580 598 610 618 620 18 478 510 538 560 578 590 598 600 19 458 490 518 540 558 570 578 580 20 438 470 498 520 538 550 558 560 21 418 450 478 500 518 530 538 540 22 398 430 458 480 498 510 518 520 23 378 410 438 460 478 490 498 500 24 358 390 418 440 458 470 478 480 25 338 370 398 420 438 450 458 460 26 318 350 378 400 418 430 438 440 27 298 330 358 380 398 410 418 420 28 278 310 338 360 378 390 398 400 29 258 290 318 340 358 370 378 380 30 238 270 298 320 338 350 358 360 31 218 250 278 300 318 330 338 340 32 198 230 258 280 298 310 318 320 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL

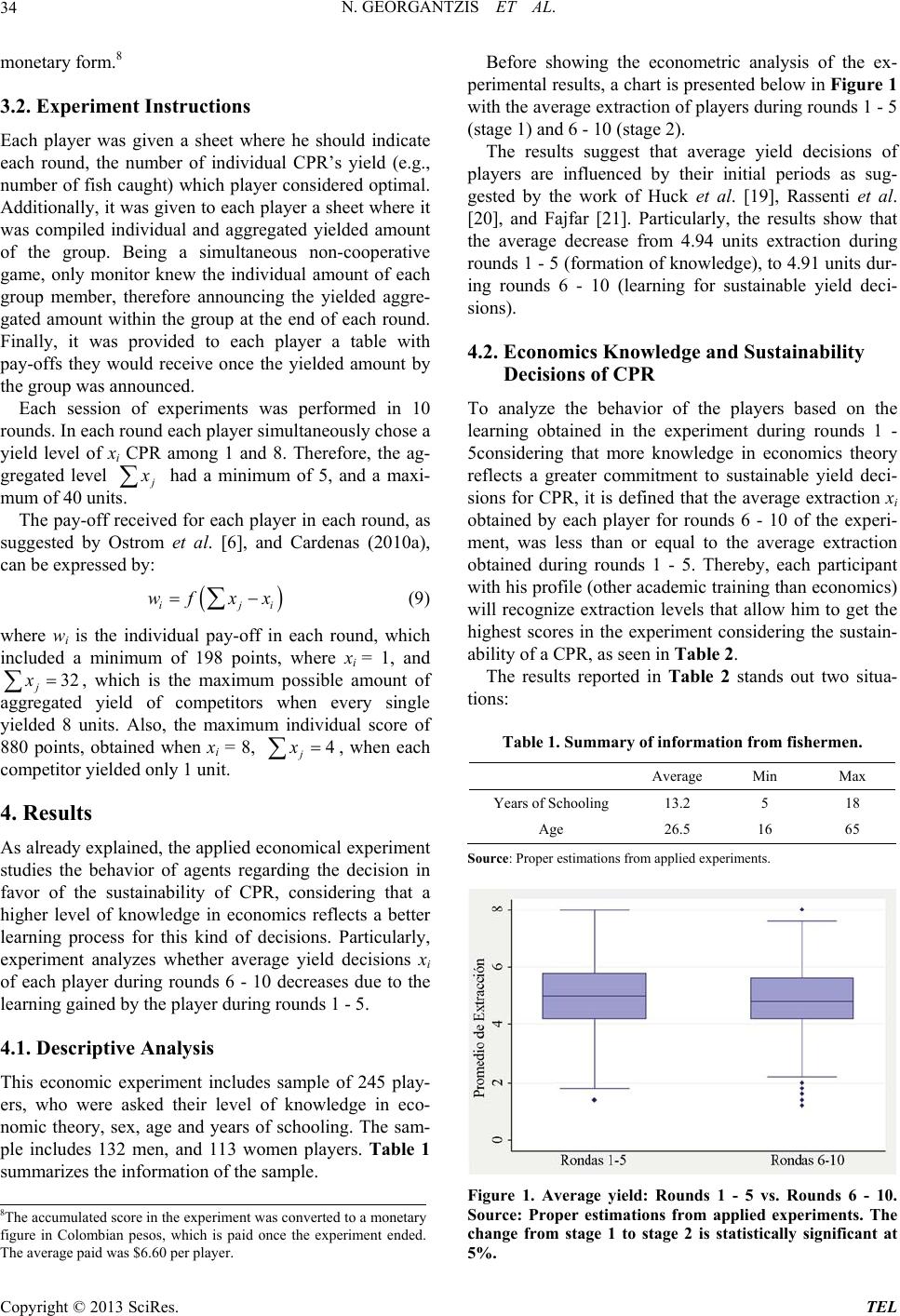

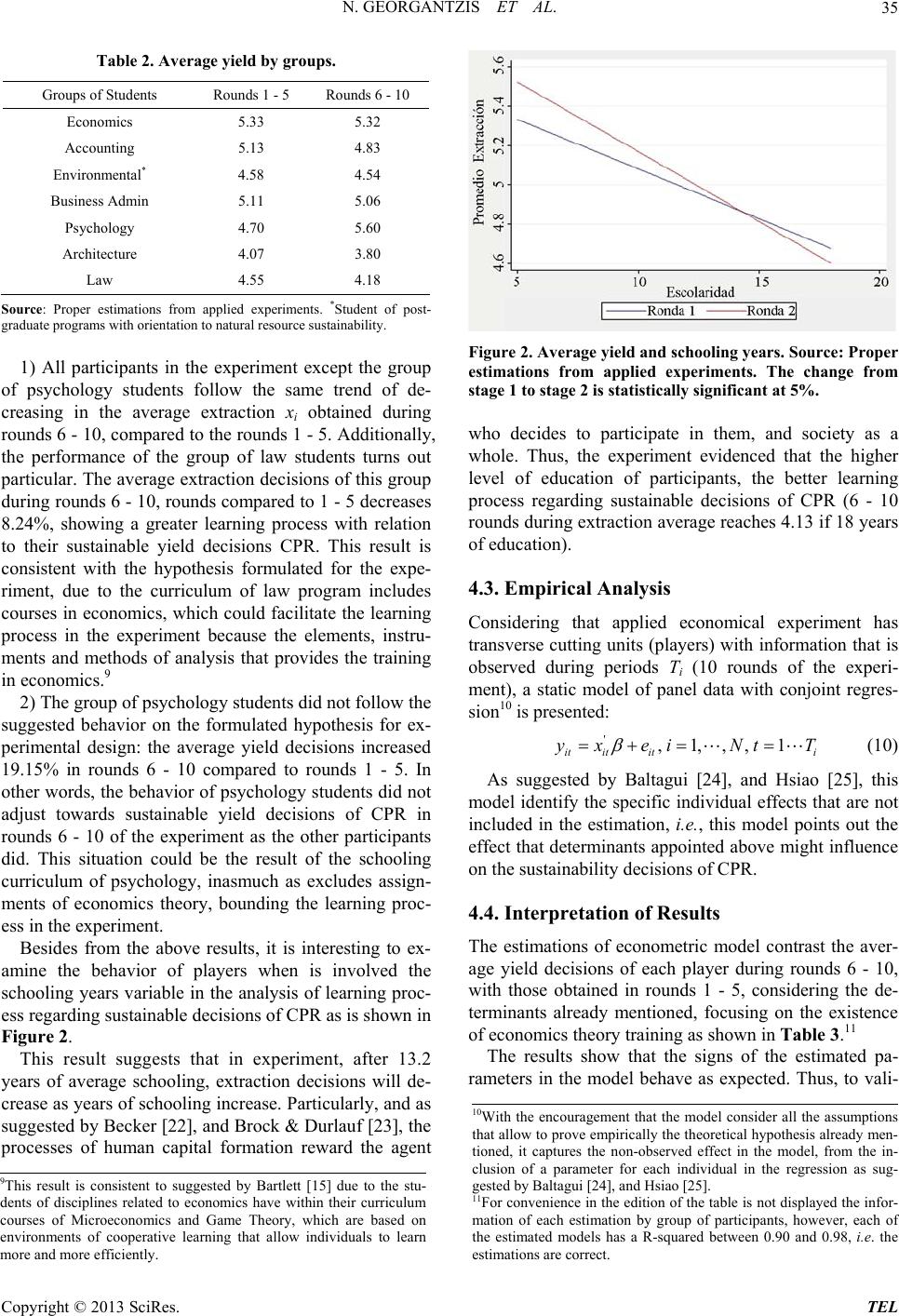

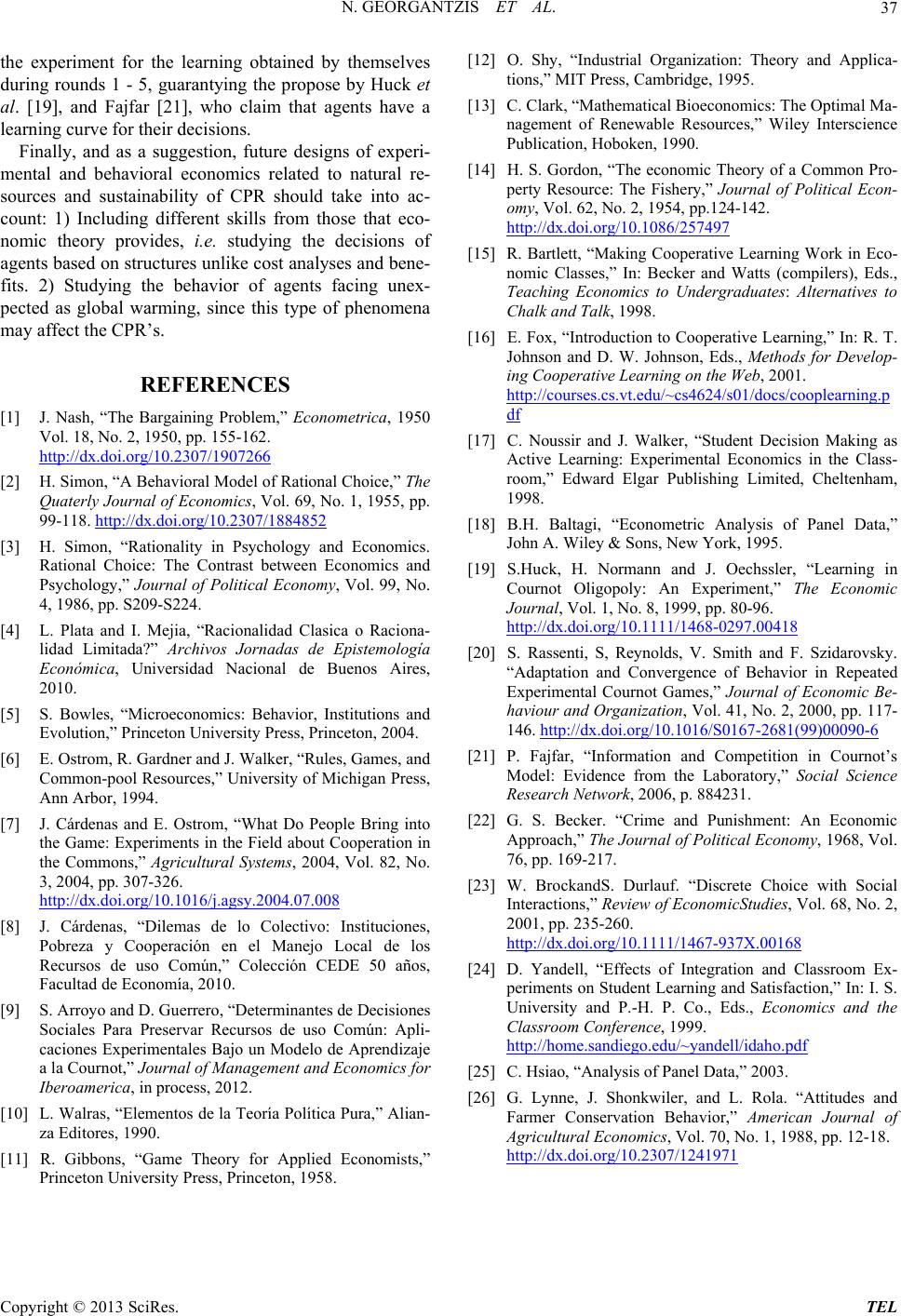

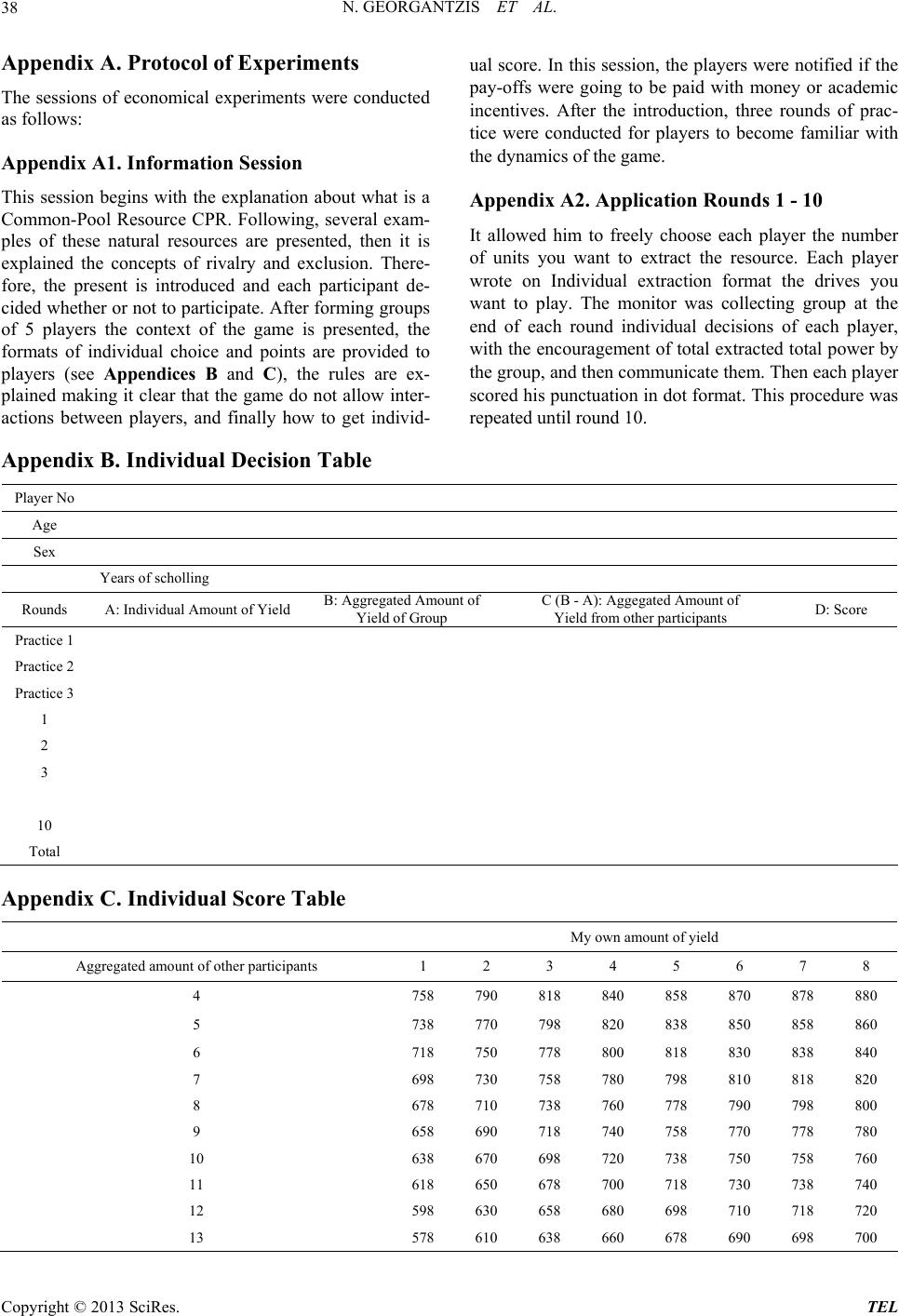

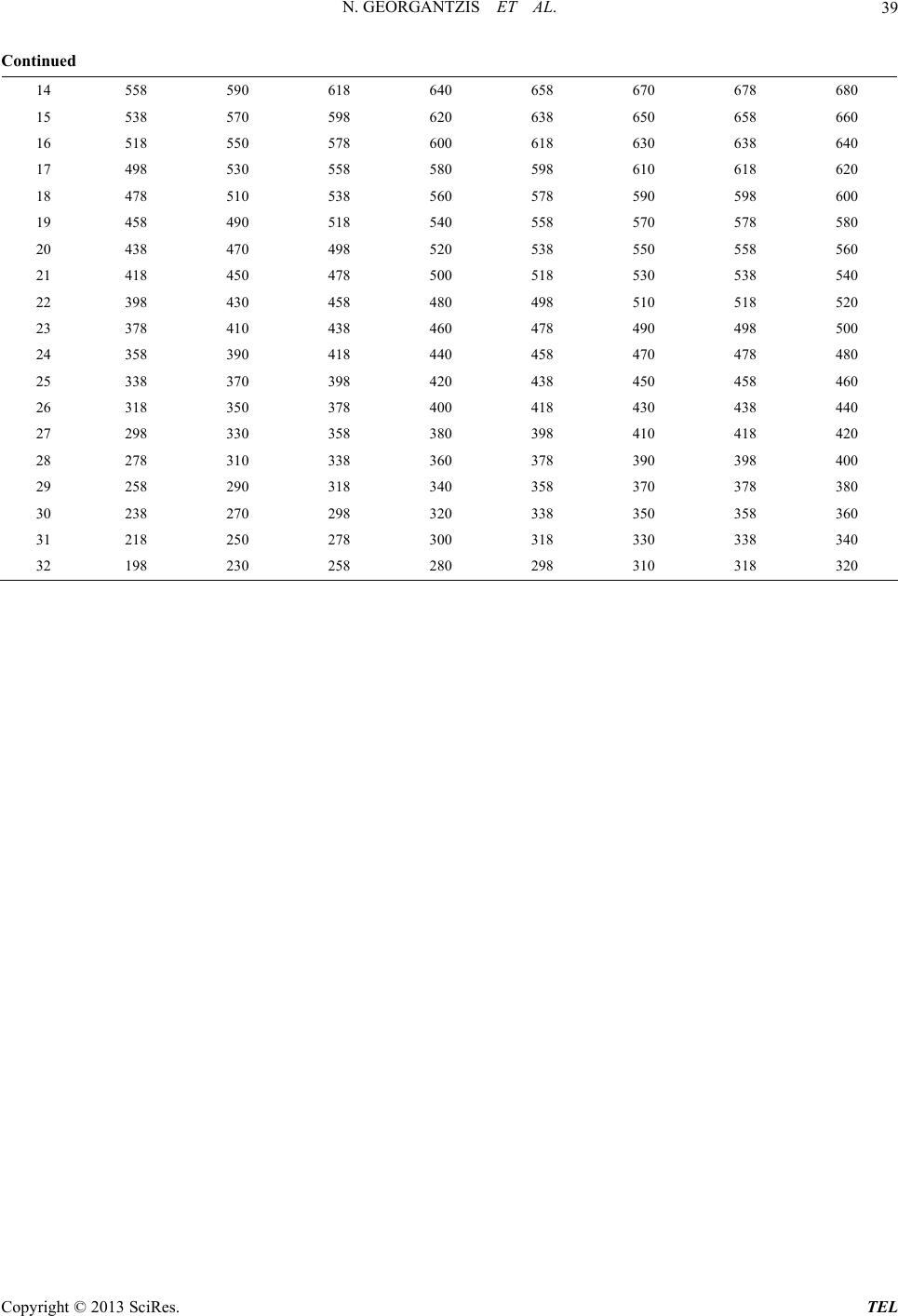

|