Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

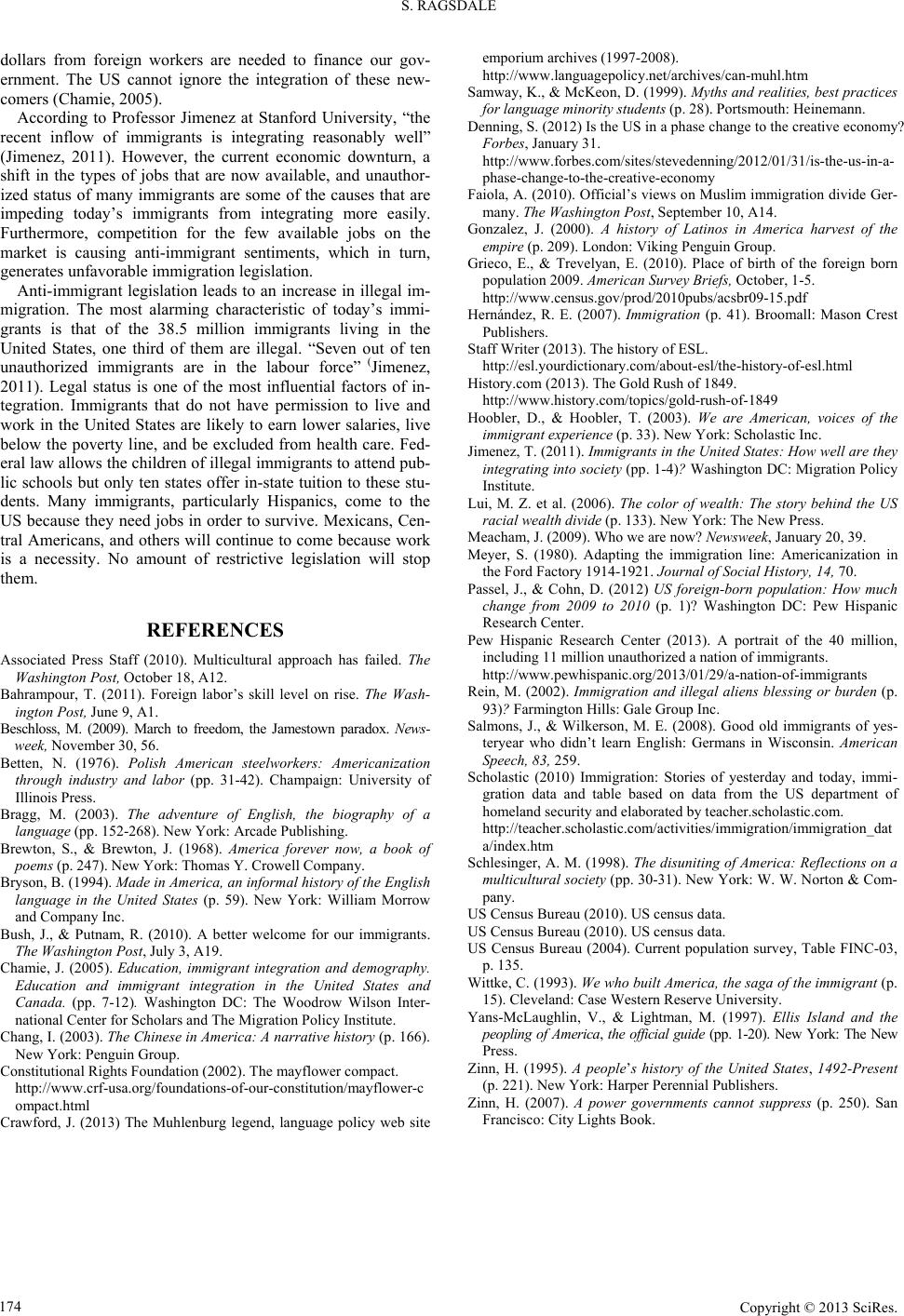

Advances in Historical Studies 2013. Vol.2, No.3, 167-174 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2013.23021 Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 167 Immigrants in the United States of America Stacy Ragsdale Department of Filology and Languages, UNED Univ ersity, Madrid, Spain Email: stacyrags@verizon.net Received July 6th, 2013; revised August 8th, 2013; accepted August 18th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Stacy Ragsdale. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Immigrant population has formed over many hundreds of years. Newcomers have arrived in large waves when jobs were plentiful and resources were unlimited; and immigration slowed during times of eco- nomic recession. Early immigrants were predominantly White Europeans that farmed the land and tried hard to find enough food to eat and a warm place to live. The Industrial Revolution brought new types of jobs which required communication and skills. Today there are 38.5 million immigrants living in the United States the majority of which are Latino. The job market has become very competitive for these new immigrants, so competitive in fact, that American residents are pressuring politicians to pass anti- immigration legislation thus making the immigration integration process very difficult. This article inves- tigates the immigration movement in the United States and events that have molded the United States in which we live today. Keywords: Immigration; Legislation; Education; History; Integration; Obstacles A Nation of Immigrants Is Born The Statue of Liberty has long symbolized the beginning of a new life for millions of immigrants fleeing poverty and hard- ship hoping to pursue happiness in the United States of Amer- ica. It is the subject for Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Co- lossus”. “Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land; here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand a mighty woman with a torch, whose flame is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand glows world- wide welcome; her mild eyes command the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she with silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” (Lazarus, 1968) Lazarus’ famous poem is engraved on a tablet cemented to the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty stands. The Statue of Liberty was the first monument most immigrants saw upon their arrival and it seemed to welcome them to the United States. Immigration to the United States can be detected as early as 15,000 BC and it still continues today. Throughout history there have been periods of massive immigration mixed with other periods in which immigration was strictly regulated and so the numbers dropped dramaticallyImmigration arrival to the US has generally come in what historians call “waves”. The first major wave of immigration begins in the early 1800s and ends around 1890. After a lull in arrivals, the second important im- migration wave comes in 1890 and lasts until the early 1920s. The third massive immigration wave begins in the 1930s near the end of the Great Depression and continues until present day. Newcomers have arrived in large waves when jobs were plentiful and resources were unlimited; and immigration has slowed during times of economic recession. Early immigrants were predominantly White Europeans that farmed the land and tried hard to find enough food to eat and a warm place to live. The Industrial Revolution brought new types of jobs that re- quired communication and skills. In 2011, the Pew Hispanic Research Center estimated that there were 40.4 million immi- grants living in the United States (Pew Hispanic Research Cen- ter, 2013) the majority of which were Latinos. The job market has become very competitive for these new immigrants. So competitive, in fact, that Americans are pressuring politicians to pass anti-immigration legislation thus making the immigration integration process very difficult. Early Immigrants Put down Roots in Ethnic-Like Settlements The first US settlers that arrived to the United States en- dured many hardships to make their dreams of a home in a new land a reality. The voyage to the US posed other obstacles to immigration. Passage was expensive and the journey could take from six weeks to six months. “Immigrants were packed into steerage. The usual height of the steerage deck was from 4 to 6 feet and the lower deck was hardly more than a black hole... No provisions were made for ventilation, the only fresh air came in through the hatches and these had to be closed during storms” (Wittke, 1993). Passengers were required to bring and cook their own food which could not stay fresh and immediately became mouldy and rotten. Diseases such as typhus, cholera, and smallpox were common on such a crowded and dirty jour- ney. In his book, A People’s History of the United States,  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 168 Howard Zinn publishes a contemporary account of one of these voyages: “On the 18th of May 1847, the “Urania”, from Cork, with several hundred immigrants on board, a large proportion of them sick and dying of the ship fever, was put onto quarantine at Grosse Isle. This was the first of the plague- smitten ships from Ireland which that year sailed up the St. Lawrence. But were driven in by an easterly wind, and of that enormous number of vessels there was not a one free from the taint of malignant typhus, the offspring of fa- mine and of the foul ship-hold... a tolerably quick passage occupied from 6 to 8 weeks... Who can imagine the hor- rors of even the shortest passage in an emigrant ship crowded beyond its utmost capacity of stowage with un- happy beings of all ages, with fever raging in their midst... the crew sullen or brutal from very desperation, or para- lysed with the terror of the plague-the miserable passen- gers unable to help themselves or afford the last relief to each other, one-fourth, or one-third, or one-half of the en- tire number indifferent stages of the disease; many dying, some dead; the fatal poison intensified by the indescrib- able foulness of the air breathed and rebreathed by the gasping sufferers-the wails of children, the ravings of the delirious, the cries and groans of those in moral agony! ... there was no accommodation of any kind on the island... Hundreds were literally flung on the beach, left amid the mud and stones to crawl on the dry land how they could... May of these... Gasped out their last breath on that fatal shore, not able to drag themselves from the slime in which they lay...” (Zinn, 1995) The hardships of immigration did not end with the journey over the sea. Once newcomers arrived they faced the challeng- ing chore of setting up new homes in a foreign land. Jamestown established by the English in 1607, was located along the James River and has been reported as being “soggy and mosquito- plagued”. Settlers at Jamestown had to build new homes, hunt or grow their own food. Many were not used to hard work and immediately became ill. Colonial immigrants felt homesick, as they would probably never see their families or country again. Many settlers packed up their belongings and tried to return home by ship. Lord Delaware who was a governor from Lon- don forced them to return to Jamestown and continue attending the mandatory church services. The Jamestown settlers endured many hardships, suc h as starva tion, harsh winters, and hostility from the Powhatan Indians. In 1610, Jamestown settlers faced a very harsh winter that was later to be known as “the starving time”. This period, characterized as a time with no food or wa- ter, drove settlers to eats rodents, cats, snakes, and even walk- ing boots. “One settler later claimed that some residents had turned to cannibalism, and that one neighbour had killed, ‘salted’ and eaten his pregnant wife... By the end of that terri- ble season, more than half of Jamestown’s settlers had per- ished” (Beschloss, 2009). Immigrants that came before the 1800s established their own ethnic colonies in different parts of the US. The earliest settlers came mostly from Spain and France and founded the first U.S. cities: Pensacola (1559) and San Augustine (1565) by the Spaniards and Fort Caroline (1564) by the French. In the Rio Grande valley, Spaniards later founded Santa Fe in 1607-1608 and Albuquerque in 1706. Spaniards settled in New Mexico and Florida, and the French all along both sides of the Missis- sippi river all the way North to Canada. Later, the English came and settled along the east coast in Virginia and Pennsylvania. The Dutch followed and settled in along the Hudson River in New York, while the Irish-Scots settled in western Pennsyl- vania and in the southern US Ethnic-like settlements in which inhabitants maintained their own cultural traditions and lan- guages began to form throughout the New World (Wittke, 1939). Some nationalities held tightly to their own ways and were reluctant to embrace a new culture and language; as a result, many Englishmen began to resent these new neighbors. In 1753, Benjamin Franklin wrote the following about the German Americans: “Few of their children in the country try to learn English. The signs in our streets have inscriptions in both lan- guages… Unless the stream of their importation could be turned…they will soon outnumber us so that we will not pre- serve our language and even our government will become pre- carious” (Bush & Putnam, 2010). The large German popula- tion was beginning to make Franklin and other citizens fear that the US would become overwhelmingly German. Germans were not the only immigrants that were feared and disliked, the Irish also faced discrimination when they began to immigrate in large numbers. In A Power Governments Cannot Suppress, author Howard Zinn describes “there was virulent anti-Irish sentiment in the 1840s and 1850s, especially after the failure of the potato crop in Ireland killed one million people and drove millions more abroad, most of them to the United States”. “No Irish Need Apply”, a phrase that often appeared in employment ads, symbolized the prejudice that existed against the Irish immigrants. Benjamin Franklin disliked the Irish, whom he called “a low and squalid class of people” (Zinn, 2007). Even before the US was established as a country, coexis- tence between ethnic groups was not trouble-free. Germans were generally criticised for the way they clung to their native language. Irish and were numerous and some considered them lazy. The Dutch also felt the sting of criticism. Dr. Drew Ham- ilton found the Dutch “both old and young... and remarkably ugly... in their persons slovenly and dirty” (Hoobler, 2003). Early colonist had never encountered such ethnic diversity in their homeland and this adjustment was proving to be chal- lenging. The United States won its independence from the British in 1776 and elected George Washington as its first president. Wa- shington welcomed immigration however he encouraged them not to come as “clannish groups but as individuals, prepared for intermixture with our people, then they would be assimilated to our customs, measures and laws: in a word, soon become one people”. John Quincy Adams held similar views and called for new immigrants to “cast off the European skin, never to resume it” (Schlesinger, 1998). He encouraged looking forward to pos- terity instead of backwards toward ancestry. With the birth of a new country, government needed a way to govern and com- municate with their new colonies and states; so they became motivated to educate colonists. English Becomes the US Common Language Although all of the US government business is conducted in English and many states have named English as their official language; the United States as a country has no declared official language. The United States were born on land discovered by  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 169 the Spanish, inhabited by Native Americans, and later settled by English, Dutch, Germans; but the English language finally prevailed. Perhaps the reason lies in the fact that the early Eng- lish settlers came here to stay and build a home, while other nationalities came for other purposes. When Christopher Columbus discovered the New World, he and his men came looking for riches that would impress the King and Queen of Spain and would secure funding for future expeditions. The Columbus expedition came and returned but did not settle. Later, the French and Dutch came to the New World to make fortunes in trade before returning to their home country. Why was it that none of these languages installed itself in the New World? The first English colony in which the Pil- grims settled in 1619 was Jamestown. Settlers had not been able to worship freely in England so they came to the New World to practice religious freedom and create a community in which they could advance Christianity. The Puritan’s bible was written in English; therefore in order to learn about religion, people needed to know English to understand about God. Learning English became a top priority for future generations so children could read the bible and worship. The first year in the New World, many Pilgrims died from lack of food, cold, and illness. Those who survived did so thanks to the Native Americans that helped the Pilgrims; one in particular named Squanto saved the Pilgrims and communicated with them in English. Squanto had been kidnapped years earlier by English sailors and taken to England. Due to the success of English colonies, the arrival of English immigrants increased. “By the end of the seventeenth century, English was being heard and taught along more than a thousand miles of the eastern coast” (Bragg, 2003). Shortly after, in 1620, 102 passengers set sail on the May- flower toward the new world. Forty one of them were Pilgrims that had left England in order to pursue a religious freedom. The rest of the passengers were indentured servants, craftsmen, women, and children that had obtained the right to settle on land claimed by the Virginia Company near the Hudson River. However, their voyage left them near Cape Cod, far north of their destination. Although they tried to sail south, sand bars made navigation difficult so the pilgrims decided to settle in Plymouth. Some passengers were unhappy with the new set- tlement and threatened to live as they pleased without reguard to their neighbors. As a result, colony leaders drafted the May- flower Compact, a document pledging allegiance to England yet simultaneously establishing a form of self government that would ensure the general good of the colony. Thus another group of Englishmen settled on the east coast (Constitutional Rights Foundation, 2002). By 1776, the use of English was spreading but other nation- alities held on tightly to their native language. German was the principle language used around eastern Pennsylvania, as a mat- ter of fact, “the first US Census reported 8.7 percent of Ameri- can spoke it as their first language” (Gonzalez, 2000). There were over 30 newspapers published in German and early Ger- man bilingual education was established. Some accounts tell a story that the colonist were prepared to adopt German as a common language and abandon English as a protest toward English colonial policy. On his Language Policy Web Site Emporium Archives (1997-2008), James Crawford, writer, lecturer, and formerly the Washington editor of Educa- tion Week, blogs about the legend of Frederick Muhlenburg. The Muhlenberg legend relates a story that the German lan- guage failed to become the official language of the United States because of Muhlenberg’s one vote. Crawford believes that this legend derives from a similar vote related to publishing some of the federal laws i n German while Muhlenberg was the Speaker of the US House of Representatives. “In 1795, the House defeated this proposal on a 42-41 vote, in which Muhlenberg may have stepped down from the Speaker’s chair to break a tie. Existing records, however, make it impossible to ascertain what role, if any, the Speaker played. It is known that he was never fluent in German.” (Crawford, 2013) According to English journalist Bill Bryson, any allegation that there was a vote to install German as the official language is absolutely false. “The only known occasion on which Ger- man was ever an issue was in 1795 when the House of Repre- sentatives briefly considered a proposal to publish federal laws in German as well as in English as a convenience to recent immigrants, and that proposal was defeated. Indeed, as early as 1778, the Continental Congress decreed that messages to for- eign emissaries be issued “in the language of the United States” (Bryson, 1994). In 1900, Germans continued to be one of the largest minorities living in the US until the post World War I era when the US began an Americanization policy. In their investigation “Good Old Immigrants of Yesteryear Who Didn’t Learn English: Germans in Wisconsin,” Miranda E. Wilkerson and Joseph Salmons suggest that early immigrants did NOT immediately learn English upon their arrival as many believe. “The full range of evidence shows that into the twentieth century, many immigrants, their children, and sometimes their grandchildren remained functionally monolingual many dec- ades after immigration into their communities had ceased. Qualitative data from the 1910 US Census, augmented by qua- litative evidence from newspapers, court records, literary texts, and other sources, suggest that Germans of various socioeco- nomic backgrounds often lacked English language skills. Ger- man continued to be the primary language in numerous Wis- consin communities, and some second- and third-generation descendants of immigrants were still monolingual as adults” (Salmons & Wilkerson, 2008). Furthermore Germans were not barred from certain types of jobs due to their monolingual status; “In Hustisford, German- town, and Kiel, monolinguals worked in a variety of settings, not only as farmers and laborers, but as stonemasons, black- smiths, cheese makers, tailors, and butchers, not to mention preachers, teachers, and foremen. In an urban setting such as Sheboygan, monolinguals were similarly widely distributed across occupations.” (Salmons & Wilkerson, 2008) Another way in which English was spread was by conquer- ing or purchasing territories. Louisiana was a colony of France that became United States property through the Louisiana Pur- chase in 1803. This land acquisition more than doubled the size of the country. When Louisiana became a state in 1812, most of the residents spoke French so their public documents were written in French and their courts and schools operated in both French and English. The governor at that time, Jacques Villere did not speak a word of English. By 1840, Englishmen had settled in all parts of Louisiana and French had become a sec- ond language. English began to prevail as more English speak- ers settled there (Gonzalez, 2000). “It would be the French who would give the opening English needed to flood over North America (Bragg, 2003).” President Jefferson immediately had Captain Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to find a river that would facilitate trade to the west coast. The Gold Rush of  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 170 1849 would draw English-speaking colonists west. When miners discovered gold in 1848 in California, millions crossed the United States in attempt to settle in California and find their fortune. This significant event redistributed the US population, and became known as the Gold Rush. “As news spread of the discovery, thousands of prospective gold miners traveled by sea or over land to San Francisco and the surround- ing area; by the end of 1849, the non-native population of the California territory was some 100,000 (compared with the pre- 1848 figure of less than 1,000). A total of $2 billion worth of precious metal was extracted from the area during the Gold Rush, which peaked in 1852” (History.com, 2013). The English language travelled west with many gold seekers The transition from Spanish to English for Mexicans living on territories annexed by the US in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo took a much longer time. Most residents eventually learned English but kept Spanish and became bilingual. Simi- larly in 1898, the US occupied Puerto Rico and tried to im- pose English as one of the official languages. When Anglo administrators tried to impose English as the language of in- struction, many students dropped out of school and the entire education system almost collapsed. Negro slaves coming in were also forced to adopt English as their new language. They were processed through a receiving station called Sullivan’s Island in Charleston, South Carolina. Half of the slaves that were taken from the West Indies were unloaded here. These immigrants came from West Africa where there were hundreds of local languages being spoken at that time. On the voyage to the New World, speakers of the same language were broken up in order to avoid mutinies and to keep slaves powerless. Many of these slaves began to use a form of “pidgin” English, a simplified form of speech with a limited vocabulary used for communication between people with dif- ferent languages. This form of English would develop further as it came ashore; so many slaves arrived speaking a form of Eng- lish. Slaves were not allowed to learn the written form of Eng- lish so that their masters would have more control over them (Bragg, 2003). Thus the English language came and spread throughout the United States as a common language. “In 1789, 90 percent of America’s four million white inhabitants were of English de- scent” (Bryson, 1994). Before the American Revolution, colo- nist considered themselves Englishmen and did not want to break away from the motherland. It took long consideration and hot debate to convince all of the colonies to declare independ- ence. As we have seen, US immigrants from different parts of the world adopted the English as their language, but immigrants also left their mark on the English language. By the end of the sixteenth century, there were words from fifty different lan- guages being used as “English” (Bragg, 1994). English was able to grow by incorporating such words as “rendezvous” (French), “pyjamas” (Hindustani), “alcohol” (Arabic), “cafete- ria” (Spanish), “taekwondo” (Korean), and “breeze” (Portu- guese). Newcomers brought their foods and spices such as goulash (Hungarian), ravioli (Italian), chilli (Mexican), and bratwurst (German); thus transforming British English into US English, the language of a melting pot. Industrial Revolution Brings Changes The colonial period ended and immigration continued its course through the Industrial Revolution. The invention of Ful- ton’s steam engine made transatlantic travel speedier, however new obstacles awaited immigrants upon their arrival to the US. Newcomers now needed to pass inspections and exams in order to remain in the US. Early immigrants were received at the dock in New York. Their muscles and teeth were inspected to see if the immigrant could withstand hard work, later the in- spection took place at Ellis Island. Once newcome rs had pa ssed inspection and were free to stay, they would likely encounter a “runner”. New York was infested with runners, who were hired to take advantage of immigrants by leading them into hotels, boarding houses, or train stations. These establishments would in turn overcharge the immigrant for everything and take ad- vantage of them. In 1903, a new immigration record was set when 857,046 foreigners arrived in the United States. Ellis Island, an immi- gration station in New York Bay was built and many of these new immigrants passed through its doors. In the years before World War I, a new group of immigrants began to arrive from Asia. These newcomers settled primarily on the west coast. These immigrants were not processed at Ellis Island; they went through Angel Island immigration station in San Francisco. Based on the 1890 US Census, it is stated that 20% of the country’s Chinese immigrants had settled in San Francisco, the main port of entry on the west coast at that time. San Francisco was the first US city to have a Chinatown, founded in 1850s (Yans-McLaughlin & Lightman, 1997). The graph (Figure 1) (Scholastic, 2010) details US immigration growth by decade. Chinese settlers were not the only oriental immigrants arriv- ing in the 1850s; the Japanese outnumbered the Chinese. More than 100,000 Japanese immigrated to the United States between 1900 and 1925. Unlike the Chinese, Japanese immigrants did not tend to settle in San Francisco or other West Coast cities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The majority of Japanese migrated to Hawaii, a US territory that had not yet become a state. As more immigrants arrived, the Japanese eventually replaced native Hawaiians as the most numerous group on the island chain. Benjamin Franklin’s concerns reappeared in the late 1800s because many native-born Americans, once again, feared that the great influx of immigrants might cause a loss of control over their country. In the 1860s, the Chinese were welcomed as cheap labour that would build our railroads. Later there was a job shortage and then Chinese were seen as a threat. In the early 1900s, both the Japanese and the Chinese encountered preju- dice and even violent attacks. Angry native-born Americans began to demand legislation that restricted Chinese and Japa- nese immigration. The Naturalization Act of 1870 and The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 were passed in response to pub- lic opinion and aimed to curb immigration from China. A “gen- tlemen’s agreement” was made in 1908 to end immigration from Japan. These laws radically cut Chinese immigration for the next 10 years and prohibited Chinese residents from be- coming citizens (Hernández, 2007). Congress passed The Naturalization Act of 1906. This Act required all immigrants to speak English in order to become nationalized citizens and languages other than English were to be discouraged. Up until this time, immigrants didn’t really need to learn English beyond the conversational level because prior to the 1800s, they lived same ethnic communities and spoke their native tongue. Most immigrants were farmers or craftsmen and had little need for a new language. During the  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 171 Figure 1. Total Immigrants by Decade Source: teacher.scholastic.com. industrial revolution, most immigrants worked in factories and were able to do their jobs with little or no English. The Naturalization Act of 1906 was a clear message from the US government: learn the predominate language and adopt the white majority culture or go back home. Before passage of this law, newcomers had continued to settle in ethnic-like neigh- borhoods making it simple for them to interact in their own language and keep their culture alive. More importantly, the lack of English knowledge had never been a barrier to entering the job market. Most immigrants easily found jobs in factories even though they knew that these jobs were often underpaid and offered hazardous conditions. The Naturalization Act of 1906 was one of the factors that encouraged English language learning but it was not the only cause. The Industrial Revolution slowly caused US industries to require workers that could learn new skills and communicate in English. In the 1800s many Chinese immigrants had jobs that required little English. They worked as miners, railroad con- struction workers, cooks, and laundrymen. By the 1900s Eng- lish became an obstacle as they became entrepreneurs. Lack of English skills made merchants vulnerable to “unscrupulous suppliers, complaining customers and thieves” (Chang, 2003). Shop workers had to find non-verbal ways of communicating such as saving the last piece of merchandise and showing it to the supplier as a way of re-ordering more supplies. In public school, classes had been given in English since the 1800s. Chi- nese children also learned English by reading English-language newspapers, listening to the radio, watching movies and reading comic books. In the early twentieth century Henry Ford revealed his con- cern about non native workers when he stated, “These men of many nations must be taught the American ways, the English language, and the right way to live” (Meyer, 1980). Ford had discovered that most of his employees did not speak English and communication problems forced Ford to spend a large amount of money on company interpreters. These issues re- sulted in the opening of The Ford School in 1914. Ford Motor Company started an “Americanization” program to help new immigrants adapt to the mass production system. In order for employees to collect their full salary of 5 dollars a day, they had to live in a single family home and not in an apartment. As a result, many immigrants moved outside their ethnic neighbourhoods. Ford offered English classes to employees that participated fully in this program. By the mid-1920s, most states had instituted English-only instructional policies in both private and public schools, which was essentially a form of submersion education for immigrant children. Ford was not the only company to look for its own solutions for teaching immigrant workers English. In 1918, over one thousand immigrant US steel workers in Gary, Indiana were enrolled in “opportunity classes”. The curriculum designed by Peter Roberts of the Young Men’s Christian Association, YMCA, dealt with citizenship education. Robert’s classes taught immigrants everyday words and phrases related to home and work, buying, selling, and travelling. Reading and Geog- raphy also formed part of the curriculum followed by “patriotic texts”. “The final phase of the YMCS program prepared the worker for the naturalization exam.” (Betten, 1976) In the 1920s, anti-immigration sentiment became even more widespread. Nativists, those who favoured the interests of cer- tain established inhabitants of an area or nation as compared to claims of newcomers or immigrants, lobbied vigorously for even more restrictions. Congressman Albert Johnson of Wash- ington worried that because the county was letting in newcom- ers from countries that “did not embrace or even know democ- racy, our capacity to maintain our cherished institutions stood diluted by a stream of alien blood” (Hernandez, 2007). So John- son proposed The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and The Im- migration Act of 1924, (Johnson-Reed Act) that set up a new quota system and restricted Italian, Jewish, Polish, and Asian immigration. As a result, only half a million immigrants were admitted into the United States during the 1930s, compared with the 4 million who had come during the 1920s. Embracing Ethnic Diversity? Because few jobs were available during the Great Depression, non-English speakers had no alternative but to take positions with unsafe working conditions, long hours, and 7-day-work weeks. Sometimes immigrants received low pay or none at all, but they were unable to defend themselves because they didn’t speak English. Resentment toward immigrants in the workplace was common, especially when work was scarce and job compe- tition was fierce. The Second World War would revive the US economy and bring more positions to the ailing US job mar- ket.  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 172 A surge in US nationalism overtook the country due to the war victory and people began to believe that nationalism was the glue that would bind the country together. Franklin D. Roosevelt said in 1943, “The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart: Americanism is not and never was, a matter of race and ancestry. A good American is one who is loyal to our creed of liberty and de- mocracy.” (Schlesinger, 1998) Another consequence of World War II was that “the United States began to recognize once again the importance of foreign languages, foreign language education, and cooperation with (as opposed to fear of) speakers of other languages which natu- rally led to a greater interest in ESL education. The US army was in need of bilingual soldiers for posts in Germany; how- ever, few Americans spoke German. This was one of the factors that caused many linguists and educators in the 1950s to put a lot of effort into English as a Second Language, ESL, research and producing a variety of ESL teaching methods that are still used, at least in part, today” (Your Dictionary The History of ESL). The 1940s marked the beginning of an expansion for ESL programs. If it seemed that the US was beginning to embrace the idea of ethnic diversity in the US during these post WWII years, Presi- dent Johnson removed all doubts in 1965. On Sunday October 3, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act at the foot of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbour. “Our beautiful America was built by a nation of strangers… from a hundred different places or more that have poured forth into an empty land, joining and blending in one mighty and irresistible tide” (Meacham, 2009). The bill that Lyndon signed on that day would transform the United States into a society of diverse cultures, religions, and ethnic groups. Immigration Nationality Act, INA, eliminated the quota by nationality system and gave preference to skilled workers and family of US residents. The 1965 law marked the beginning of a massive wave of immigration to the US. Even though the Nationality Act of 1965 did not cause an immediate increase in population, most historians believe that the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the doors to the third wave of immigration that is still in progress today. This wave began slowly and Latin American and Asian arrivals were twice as high as that of the Europeans marking a shift from a predominately European immigrant population to a Latino one. Throughout the 80s, immigration continued to rise and more than 8 million new immigrants came that figure increased be- tween 1991 and 2000 to 9.1 million. European immigration decreased to 705,000 in the eighties and then as a result of the fall of communism in the 1990s, 1.3 million Europeans came. Uncounted illegal immigrants add significantly to that total according to McLaughlin and Lightman. Later in an attempt to curb illegal immigration, the Immigration Reform and Control Act was passed in 1986. This act established sanctions against employers who hired illegal immigrants and offered amnesty for illegal immigrants requesting legal status. An agricultural guest program was set up for alien laborers. By the 1990s, immigrants were coming mostly from Asia, South and Central America, according to Mei Ling Rein author of Immigration and Illegal aliens: Burden or Blessing. These immigrants were more likely to be women, around the age of 29, with a technical occupation such as a labourer, machine operator or service occupation. Mexico was the county with the most immigrants (131,575) in 1998. Mexico was followed by China (36,884), India (36,482), Philippines (34,466) and the Dominican Republic (20,387). These immigrants wanted to live in a community where they felt comfortable, one that had lots of jobs, and hopefully had friends and family already living in that same community. Unfortunately 40% of new immigrants that came in 1998 only wanted to live in two states: California (25.8%) and New York (14.6%). Florida, Texas, New Jersey and Illinois were other popular destinations. The chart below (Figure 2) (US Census Bureau, 2004) illustrates data found in the U.S. Census Bureau Current Population survey of 2004. Immigrants during these years were more likely to be poor. According to Rein, “in 1999 more than one third (36.3%) of foreign born full time, year round workers earned less than $20,000 compared to one fifth (21.3) of their native counter parts.” In 2003, the majority of Latino immigrants earned be- tween $25,000 and $39,999 each year while the majority of whites earned over $80,000. The wage gap between immigrants and whites was extremely wide (Rein, 2002). In their book, The Color of Wealth: The Story Behind the US Racial Wealth Divide, Meizhu Lui and Barbara use home own- ership data from 2003 to point out that all immigrant groups were not faring equally as well. Among white residents 75.4% owned a home while only 48.1% of African Americans and 46.7% of Latinos did so. Fifty six percent of Asian/Pacific Is- landers owned homes and fifty four percent of Native Ameri- cans did as well. There was also a large variation in the values of the homes owned. According to data compiled by Barbara J. Robles, analysis or federal Bank survey of consumer finances, the mean White primary residence value was $141,769 in 2003, the Negro primary residence value was $45,476, and the Latino primary residence value was the lowest at $53,548 (Meizhu, Robles, Leondar-Wright, Brewer, & Adamson, 2006). US Immigrants Today Today’s immigrants are different from early immigrants for several seasons. The early immigrant population was predomi- nantly European; modern day immigrants come mostly from Latin America and Asia. Early immigrants were rural farmers; today the immigrants that arrive are urban workers. Early im- migrants came to the United States to stay and had little possi- bility of returning home and there was little contact with their country of origin. Today’s immigration allows for more back and forth movement between the country of origin and the US White and Hispanic Income Yearly Earnings in 2003Percentage of Whites Percentage of Latinos 0 - $14,999 6.5% 16.48% $15,000 - 24,999 9.35% 18.26% $25,000 - 39,999 15.50% 22.60% $40,000 - 59,999 18.71% 17.90% $60,000 - 79,999 15.81% 11.07% $80,000 34.13% 13.67% Figure 2. White and Hispanic income in 2003; Source: US Census Bureau Cur- rent Population survey 2004, Table FINC-03, p. 13 .  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 173 Also advanced technology allows immigrants to stay in touch with their homeland. Perhaps the most important transformation has occurred within the US itself; the US has shifted from an agricultural based economy then to an industrial economy and finally to an information-based economy, therefore, today’ s immigra nt is e x - periencing a lack of low-skilled jobs. The following table (Fig- ure 3), based on Passel and Cohn’s Pew Hispanic Research Center report (Passel & Cohn, 2012), illustrates the make-up of the US immigrant population in 2009 and 2010. Many of the factory and farm jobs that were available to early immigrants, have moved to other countries and the US job market is now a difficult place for unskilled workers. The US economy has shifted from agriculture, to industry, then services, and finally information. As Steve Denning at Forbes magazine explains, “In 1900, it took a large portion of the US population to produce enough food for the country as a whole. With better farming practices, fewer people were needed. At the beginning of the 1930s, more than a fifth of all Americans still worked on farms. A much smaller percentage was actually needed. Today, 2 percent of Americans produce more food than we can con- sume. The Great Depression, was about finding jobs for all those who were no longer needed on farms.” (Denning, 2012). As a result of these economic changes, the number of un- skilled jobs available has decreased. A college degree, excellent English skills and job training are now necessary to succeed. According to authors Katharine Davies Samway and Denise McKeon: “whereas our immigrant grandparents generally needed no more than oral, interpersonal communication skills in English, at most, in order to succeed in the United States, today’s immigrants must reach high levels of literacy in order to participate beyond the poverty level. Conse- quently, simply placing newcomers in an English-speak- ing environment will not adequately prepare them to par- ticipate fully in the life of the nation” (Samway & Mc- Keon, 1999). Immigrants now need to be well educated to succeed in the United States, and educational institutions are the key to help- 2009 2010 Total (thousands) 39,929 39,313 Mexico 11,747 11,707 Central America 2989 3015 Carribean 3749 3529 South America 2740 2675 South/East Asia 9985 9743 Middle East 1384 1353 Europe and Canada 5798 5847 Africa and Oceania 1501 1414 Other 37 30 Figure 3. Revised immigrant population living in the US 2009-2010; Source: Pew Hispanic Research Center. ing immigrants obtain better jobs. Unfortunately immigrant children are not performing as well in US public schools school as native-born White children are. The Department of Edu- cation measures national reading and math proficiency through the NAEP, National Assessment of Educational Process. In 2011, of the 8th graders in the “all” category, 24% of them were reading below proficient level while 36% of Latinos scored below proficient on the NAEP reading evaluation. Also 27% of all children scored below level in Math, but the figure was 39% for Latinos. This gap between White and Hispanic academic performances is known as the Hispanic Achievement Gap. Addressing this gap would ensure a prosperous future for US Hispanics. In 2010, the foreign-born population was 38.5 million resi- dents, 12.5% of the total US population. Over half of them (53.1%) came from Latin America, over a quarter of them (27.7%) came from Asia, 12.7% came from Europe, 3.9% came from Africa, and 2.7% came from “other” regions (Grieco & Treveyan, 2010). Of the 20.5 million immigrants from Latin America, 56% of them came from Mexico and China sent the most immigrants from Asia. Of those immigrants 79% entered the US before the year 2000. Eighty per cent of the population speak only English at home. Today’s immigration population is much more geographi- cally diverse. Only fifty six percent of the total foreign-born population lives in the traditional immigration states: California (9.9 million), New York (4.2 million), Texas (4.0 million), and Florida (3.5 million). The other 46% settled in non-traditional Midwestern or southern states. Many states that have not typi- cally had large Latino populations are experiencing growth in their Hispanic population. In Georgia, the Latino population has grown by 96.1% from 2000 to 2010; Alabama increased by 144.8%, Mississippi by 105.9%, Tennessee by 134.2%. Latino population is still increasing in traditionally Latino states but at a slower rate; California increased by 27.8%, Arizona by 46.3, Texas by 41.8%, and Florida by 57.4%; but there are now large increases in other states (US Census, 2010). The modern immigrant work force is made up of diverse backgrounds. The poorest and least skilled workers are immi- grating to the United States along with the most educated and wealthy workers. The immigrant work force has increased from 14.6 million in 1994 to 29.7 million in 2010; however an im- portant shift has taken place. For the first time in the year 2007, the number of skilled workers outnumbered the lower-skilled workers. According to a report published by the Brookings Ins- titution and based on census data, “30% of the county’s work- ing-age immigrants, regardless of legal status, have at least a bachelor’s degree, while 28% lack a high school diploma” (Bahrampour, 2011). The report also found that more highly skilled immigrants came from India, China, and the Philippines; while Mexico and Central America tended to send lower skilled labour. These skilled immigrants tended to work in coastal cities or metropolitan areas. Lower skilled workers were more common in the areas near the US Mexican border. Even though an immigrant has a higher education, their foreign credentials are often not recognized in the US therefore, half of the US immigrants are working at a job for which they are over quail- fied. Immigration expert Joseph Chamie claims that without im- migration, the US population growth would decrease by as much as 80%. The United States relies on immigration to keep growing as a nation. Furthermore the US must look to immi- gration in order to complete its aging work force. Finally, tax  S. RAGSDALE Copyright © 2013 SciRe s . 174 dollars from foreign workers are needed to finance our gov- ernment. The US cannot ignore the integration of these new- comers (Chamie, 2005). According to Professor Jimenez at Stanford University, “the recent inflow of immigrants is integrating reasonably well” (Jimenez, 2011). However, the current economic downturn, a shift in the types of jobs that are now available, and unauthor- ized status of many immigrants are some of the causes that are impeding today’s immigrants from integrating more easily. Furthermore, competition for the few available jobs on the market is causing anti-immigrant sentiments, which in turn, generates unfavorable immigration legislation. Anti-immigrant legislation leads to an increase in illegal im- migration. The most alarming characteristic of today’s immi- grants is that of the 38.5 million immigrants living in the United States, one third of them are illegal. “Seven out of ten unauthorized immigrants are in the labour force” ( Jimenez, 2011). Legal status is one of the most influential factors of in- tegration. Immigrants that do not have permission to live and work in the United States are likely to earn lower salaries, live below the poverty line, and be excluded from health care. Fed- eral law allows the children of illegal immigrants to attend pub- lic schools but only ten states offer in-state tuition to these stu- dents. Many immigrants, particularly Hispanics, come to the US because they need jobs in order to survive. Mexicans, Cen- tral Americans, and others will continue to come because work is a necessity. No amount of restrictive legislation will stop them. REFERENCES Associated Press Staff (2010). Multicultural approach has failed. The Washington Post, October 18, A12. Bahrampour, T. (2011). Foreign labor’s skill level on rise. The Wash- ington Post, June 9, A1. Beschloss, M. (2009). March to freedom, the Jamestown paradox. News- week, November 30, 56. Betten, N. (1976). Polish American steelworkers: Americanization through industry and labor (pp. 31-42). Champaign: University of Illinois Press. Bragg, M. (2003). The adventure of English, the biography of a language (pp. 152-268). New York: Arca d e Pu b li sh in g . Brewton, S., & Brewton, J. (1968). America forever now, a book of poems (p. 247). New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. Bryson, B. (1994). Made in America, an informal history of the English language in the United States (p. 59). New York: William Morrow and Company Inc. Bush, J., & Putnam, R. (2010). A better welcome for our immigrants. The Washington Post, Ju ly 3, A19. Chamie, J. (2005). Education, immigrant integration and demography. Education and immigrant integration in the United States and Canada. (pp. 7-12). Washington DC: The Woodrow Wilson Inter- national Center for Scholars and The Migration Policy Institute. Chang, I. (2003). The Chinese in America: A narrative history (p. 166). New York: Penguin Group. Constitutional Rights Foundation (2002). The mayflower compact. http://www.crf-usa.org/foundations-of-our-constitution/mayflower-c ompact.html Crawford, J. (2013) The Muhlenburg legend, language policy web site emporium archives (1997-2008). http://www.languagepolicy.net/archives/can-muhl.htm Samway, K., & McKeon, D. (1999). Myths and realities, best practices for language minor i ty students (p. 28). Portsmouth: Heinemann. Denning, S. (2012) Is the US in a phase change to the creative economy? Forbes, January 31. http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2012/01/31/is-the-us-in-a- phase-change-to-the-creative-economy Faiola, A. (2010). Official’s views on Muslim immigration divide Ger- many. The Washington Post, September 10, A14. Gonzalez, J. (2000). A history of Latinos in America harvest of the empire (p. 209). London: Viking Penguin Group. Grieco, E., & Trevelyan, E. (2010). Place of birth of the foreign born population 2009. American Su rv ey B riefs, October, 1-5. http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/acsbr09-15.pdf Hernández, R. E. (2007). Immigration (p. 41). Broomall: Mason Crest Publishers. Staff Writer (2013). The history of ESL. http://esl.yourdictionary.com/about-esl/the-history-of-esl.html History.com (2013) . The Gold Rush of 1849. http://www.history.com/topics/gold-rush-of-1849 Hoobler, D., & Hoobler, T. (2003). We are American, voices of the immigrant experience (p. 33). New York: Scho last ic Inc. Jimenez, T. (2011). Immigrants in the United States: How well are they integrating into society (pp. 1-4)? Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute. Lui, M. Z. et al. (2006). The color of wealth: The story behind the US racial wealth divide (p. 133). New York: The New Press. Meacham, J. (2009). Who we are now? Newsweek, January 20, 39. Meyer, S. (1980). Adapting the immigration line: Americanization in the Ford Factory 1914-1921. Journal of Socia l History, 14, 70. Passel, J., & Cohn, D. (2012) US foreign-born population: How much change from 2009 to 2010 (p. 1)? Washington DC: Pew Hispanic Research Center. Pew Hispanic Research Center (2013). A portrait of the 40 million, including 11 million unauthorized a nation of immigrants. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/01/29/a-nation-of-immigrants Rein, M. (2002). Immigration and illegal aliens blessing or burden (p. 93)? Farmington Hills: Gale Group Inc. Salmons, J., & Wilkerson, M. E. (2008). Good old immigrants of yes- teryear who didn’t learn English: Germans in Wisconsin. American Speech, 83, 259. Scholastic (2010) Immigration: Stories of yesterday and today, immi- gration data and table based on data from the US department of homeland security and elaborated by teacher.scholastic.com. http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/immigration/immigration_dat a/index.htm Schlesinger, A. M. (1998). The disuniting of America: Reflections on a multicultural society (pp. 30-31). New York: W. W. Norton & Com- pany. US Census Bureau (2010). US census data. US Census Bureau (2010). US census data. US Census Bureau (2004). Current population survey, Table FINC-03, p. 135. Wittke, C. (1993). We who built America, the saga of the immigrant (p. 15). Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University. Yans-McLaughlin, V., & Lightman, M. (1997). Ellis Island and the peopling of America, the official guide (pp. 1-20). New York: The New Press. Zinn, H. (1995). A people’s history of the United States, 1492-Present (p. 221). New Yo r k: Harper Perennial Publishe rs. Zinn, H. (2007). A power governments cannot suppress (p. 250). San Francisco: City Lights Bo ok. |