Health

Vol.5 No.12(2013), Article ID:41467,14 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.512298

“Breast is best”—Infant-feeding, infant mortality and infant welfare in Germany during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries

![]()

Institute for the History of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; *Corresponding Author: voegele@uni-duesseldorf.de

Copyright © 2013 Jörg Vögele et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 21 October 2013; revised 25 November 2013; accepted 12 December 2013

Keywords: Paediatrics; History of Medicine; Infant Feeding; Infant Mortality; Infant Health; Germany

ABSTRACT

Breastfeeding is considered to be the key variable for infant health. Consequently, UNICEF and the World Health Organization promote the beginning of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth and recommend to exclusively breastfeed the infant during the first six months. The origins of these modern breastfeeding campaigns can be traced back to the beginning of the twentieth century. Whereas high infant mortality rates traditionally were considered to be a matter of fate and the declining birth rates towards the end of the nineteenth century raised fears about the nation’s future and led to the emergence of an increasing infant welfare movement in imperial Germany. As low breastfeeding rates were identified as a key factor behind the high infant mortality rates, the main objective of the infant care movement was to increase breastfeeding. The paper examines how the context of infant care and infant mortality was constructed and how breastfeeding campaigns in the context of infant mortality, breastfeeding rates and socio-political changes developed during the twentieth century. Thus the paper covers the period from the beginnings of social paediatrics at the beginning of the 20th century, the breastfeeding campaigns embedded into Nazi ideology during the Third Reich, until the declining breastfeeding ratios and the “feeding on demand”-movement in the 1970s as well as the ideological differences between West and East Germany during the Cold War.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past 150 years, the average life-expectancy in Western Europe has more than doubled. At the constitution of the German Empire, life-expectancy at birth was 36 years for men and 39 years for women, in 2008/10, however, these figures amounted 78 and 83 years respectively [1]. The successful reduction of infant mortality played a decisive role in this development. Whereas during the last third of the nineteenth century, more than 20 percent per year of birth did not reach their first birthday, the infant mortality rate in Germany today is below 0.5 percent, and the life-expectancy of infants is higher than that of one-year-old and older. The key turn of this development occurred after 1900: Apart from individual crisis years, infant mortality fell almost continuously during the course of the twentieth century. At the end of the 1920s, it decreased below the 10 percent mark, and in the 1950s it went below 5 percent (Figure 1). Meanwhile, death in the industrialized nations has not only withdrawn from infancy and childhood, but has largely withdrawn from all age groups under 70 years. From a global perspective, however, this report reads completely different: While according to UNICEF infant mortality in 2010 amounted to 0.5 percent in industrialized nations, it surpassed 4 percent in developing countries and 7 percent in least developed countries, with peaks of 11.2 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 11.4 percent in Sierra Leone [2].

Whereas nowadays perceived as a tragedy, the death of an infant in preand early modern societies was traditionally conceived as an unpreventable matter of fate, accompanied even by parental indifference [3,4]. On one hand, parents protected themselves psychologically in the face of high infant mortality by emotional distance, on the other hand, this in turn exactly led to further infant deaths. Mother’s love, as we conceive it today, is

Figure 1. Infant mortality in Germany, 1816-2007. Prussia 1816-1900, Reichsgebiet 1901-1938, until 1989 Western Germany, from 1990 Germany. Sources: Vögele, 2001, 294; 2001; DESTATIS.

said to be merely a construct of modernity. High infant mortality was interpreted in religious terms in the sense of the Bible “[…] the Lord gave and the Lord has taken away; let the Lord’s name be praised” [5]. Particularly in Catholic areas not the survival of the infant, but its baptism was reckoned to be the most important objective. Consequently, the infant was often taken to the church within a few hours or days after birth, even in the winter and even when the church was in more than one hour distance, in emergency cases it was even allowed that a lay person could baptize the infant. For such purposes, doctors constructed instruments which made it possible to baptize the embryo in utero [6].

It was the decline of birth rates towards the end of the nineteenth century that led to an increasing perception of the continuing high infant mortality rates, particularly when assessed from an international perspective. Fears about the nation’s future in economic and military respects made the reduction of infant mortality a central and scandalized theme in the debates on social policy. Economists calculated the value of a newborn, and estimated the national economic loss caused by the deaths of infants [7]. In this context, physicians gained increasing attention and scientific authority. As a result, this led to the establishment of paediatrics in German academia, and in the wake of this rise a substantially increasing number of scientific papers were published, dealing with the subject of infant mortality in the socio-political, demographic, economic and medical contexts.

Around 1900, more than 70 percent of all infant deaths resulted from gastro-intestinal disorders [8]. This pinpoints the disproportionate role of digestive diseases and disorders amongst infants, which were attributed to inadequate feeding practices. Consequently, feeding practices have been regarded as the key determinant of infant mortality in Germany, specifically the question of whether and how long the infant was breastfed, when the transition to the so-called artificial nutrition took place, which formula, or which quantity etc. was fed [9]. Infant mortality, infant feeding and breastfeeding behaviour of the mothers became the subjects of scientific research and large-scale public health campaigns. For these reasons, the infant diet and in particular breastfeeding were declared the centrepiece of social paediatrics and its infant welfare movement in the early twentieth century. Lines of argument that have been brought to fore are propagated with breastfeeding recommendations to this day; in fact, breastfeeding propaganda has been the only public health campaign which lasted over the complete twentieth century. This paper examines how the context of infant care and infant mortality during the Empire was constructed and how breastfeeding recommendations in the context of infant mortality, breastfeeding rates and socio-political changes developed during the twentieth century.

2. INFANT WELFARE AND INFANT MORTALITY DURING THE GERMAN EMPIRE

A complex set of determinants is responsible for the amount and trend of historical infant mortality: Legitimacy of the babies, fertility, weather and climate, improved hygienic conditions in the wake of sanitary reforms (water supply, milk supply, sewerage), public health care, housing and general living conditions, education, wealth and occupation of parents, and general attitudes toward life and death [10-15]. A key variable for infant mortality in both historical and contemporary perspective, however, is the diet of infants. Since curative therapies were available only to a limited extent, paediatric medicine at the turn of the century increasingly focused on social hygienic approaches and nutritional science [16]. The shift to artificial feeding has been associated with high infant mortality, as preparing the food with milk or water or—as in some areas of practice—pre-chewed by adults could cause gastro-intestinal infections. Particularly notorious were the socalled meal-pap and sugar water, often prepared in the morning and warmed up three to four times a day. The bottle was filled with pre-chewed bread and sugar and the nipple dipped in beer [17]. It was even reported that it was not uncommon to use opiate additives in artificial food to pacify the infants in southern Germany. Contemporaries often criticised the widespread use of beer, gin, and spirits to “nourish” the infant or child. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, parental guidelines for infant care felt obliged to point out that alcohol might damage the infant’s health [18]. In sum, extensive breastfeeding thus was linked with low death rates, since it minimized the risks of malnutrition and provided some protection against bacterial infection.

Estimates on a national level at the beginning of the twentieth century, revealed that the death rate of “bottle fed” babies was up to seven times higher than that of the breast fed children [19]. Contemporary local surveys indicated that the breastfeeding rate tended to decrease with rising income, particularly in the upper classes of society breastfeeding was less common [20]. Breastfeeding could even outbalance the impact of social class on health and life-expectancy: Less breastfed infants died even under precarious economic and social conditions than artificially fed infants in families with a good economical background. In selected sections of the administrative district of Düsseldorf, the mortality rate of bottle-fed children from wealthier families (paternal yearly income of more than 1500 Marks) was, with around 30 percent for one-year-olds and 18 percent for two-yearolds, much higher than the mortality rate of breastfed children from poorer families (paternal yearly income of less than 1500 Marks) with 14 and 7 percent respectively. Among infants from poor families who were artificially fed, the mortality rate was 56 percent in the first quarter of their first year and 32 percent in the second quarter [21].

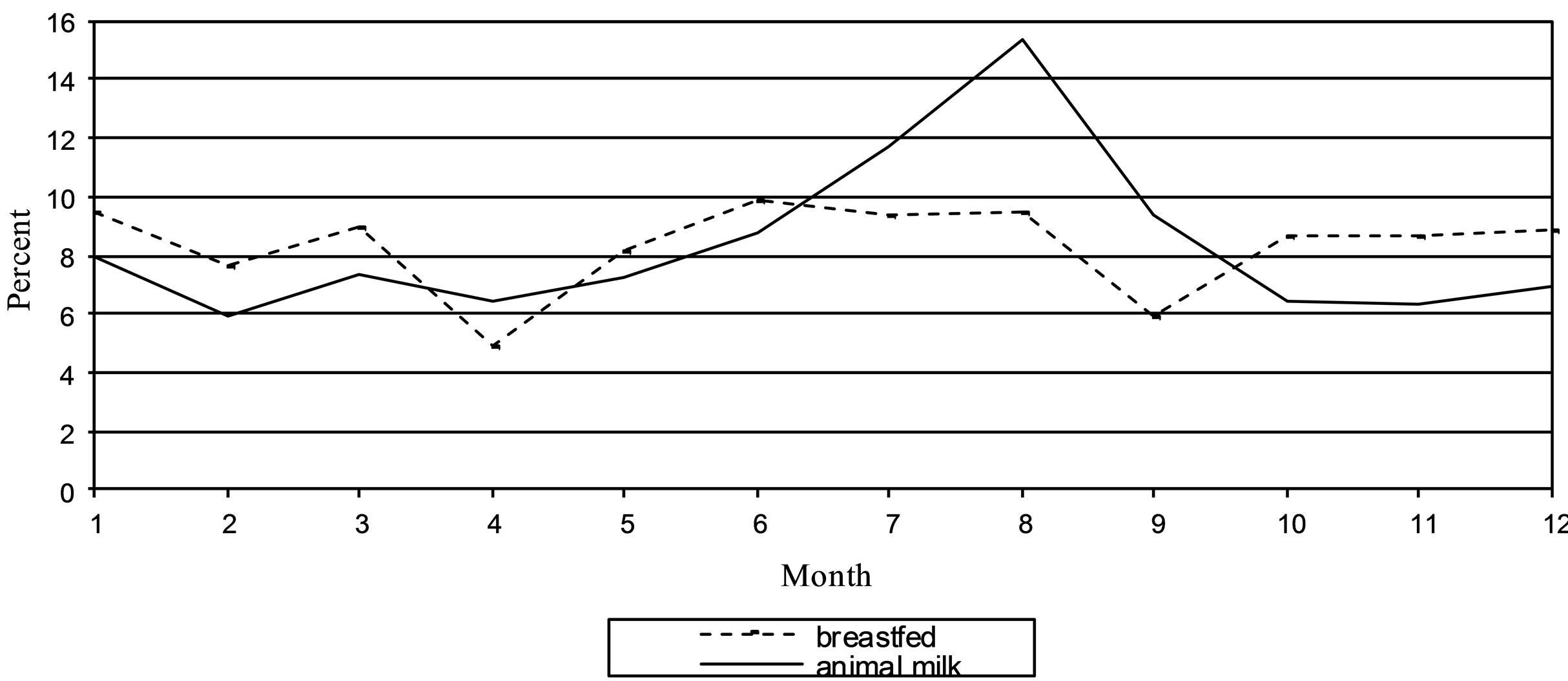

Furthermore, breastfeeding served as a prophylaxis against the highly feared summer diarrhoea. Traditional seasonal fluctuations in infant mortality persisted well into the twentieth century, with a pronounced summer peak and affected most powerfully artificially-fed infants [22]. Excellent long-run sources in Hamburg show that summer infant mortality was even higher in the early twentieth century, when compared with the preceeding hundred years [23]. Data for Berlin, where information about infant feeding was collected in the course of the census, reveals that excess summer mortality affected artificially-fed infants most profoundly, whereas breastfeeding provided some protection in the hot periods of the year (Figure 2).

There were also strong regional differences in breastfeeding rates. Thus the eastern and south-eastern regions of the German Empire registered high infant mortality rates related to low breastfeeding in these areas. It was further alarming that breastfeeding rates in the Empire not only were low by international standards, but were also declining in the growing industrial cities of the Empire [24]. To name just a few examples: In the city of Cologne, only 40 percent of all women breastfed their children in 1902, whereas one generation before, the mothers of these women had still breastfed their babies to more than 90 percent [25]. According to the breastfeeding surveys of Berlin, made periodically as part of the census, the rate of infants exclusively breastfed by their mothers decreased from 55.2 percent in 1885 to 30.5 percent in 1910 [26-29].

These developments led to the establishment of nu-

Figure 2. Seasonal distribution of infant mortality in berlin according to nourishment, 1908 (Percent). Source: Statistisches Jahrbuch der Stadt Berlin, 32, 1913, 183.

merous infant welfare centres in Germany as well as in other Western European countries at the beginning of the twentieth century [30]. In many places they were founded by city councils or local civic societies. In Germany, the “Verein für Säuglingsfürsorge im Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf” and the “Kaiserin Auguste Victoria-Haus zur Bekämpfung der Säuglingssterblichkeit im Deutschen Reiche”, (“Association for infant welfare in the district of Düsseldorf” and the “Empress Augusta Victoria House for the control of infant mortality in the German Empire”) were both founded in 1907, the latter under the patronage of the German Empress [31,32]. They both served as examples for the foundation of other institutions. In the course of the same year over a hundred infant care centres were registered [33]. Their aim was to encourage mothers to breastfeed their infants through education and supervision. Consequently, breastfeeding campaigns were launched throughout Germany, balancing in their means between propaganda and instruction, education and control [34,35].

The campaigners designed leaflets and popular parents’ guides that postulated a personal responsibility of each individual for his own health and the health of his descendants with respect to society. They organised courses for mothers in urban centres and employed country teachers travelling from village to village throughout the country to teach mothers the basics of infant care. Paediatricians understood the importance of the way of presenting and explaining in order to successfully popularise the basics of hygiene in infant care and preventive health care. Arthur Schlossmann, director of the Düsseldorf children’s hospital, summarised: “We have to reach the great masses with our lessons and reminders, and we have to turn our knowledge of infant care into a common knowledge—this must be the goal towards which we strive” [36]. From the three ways of teaching—orally, written or figuratively—soon the latter was judged as the most effective. The visualisation of knowledge seemed the most promising to reach all levels of society [37]. A picture was considered to be perfect for fast and easy communication; it could function as an optical signal and enable a faster and better transfer of contents than reading or listening could. As a result, exhibitions on health care increased on a national and international level. The first exhibition about infant care took place in 1906 in Berlin, and the success of the great Hygiene-Exhibition of 1911 in Dresden ultimately demonstrated that the principle of the exhibition was gaining importance within teaching women and mothers in particular, eventually leading to the popularization of picture based knowledge. It created an alliance between doctors as instructive scientists and society as an advised entity. In a civil political sense there were positive side effects of this presentation and celebration of medical knowledge for the profession of the pediatrician. In addition to the knowledge transfer, the opportunity of visualization also implied a popularization of the medical profession itself. Expert knowledge could now also be displayed within a non-expert-public; by simplified presentations of human anatomy, for example, or in relation to organic processes of the body. The exhibitions gradually enhanced the prestige of the profession. Even economically the exhibition concepts led to a lucrative connection between medicine and industry. Due to financial constraints on the part of the organizers, exhibition space was regularly leased to companies. The products presented were therefore both exhibits and commercial advertising [38]. Since the exhibitions were, however, presented only locally and for a limited period of time, relevant material was soon compiled and published, such as the “Atlas der Hygiene des Säuglings und des Kleinkindes” (atlas of infant hygiene), developed and edited by Fritz Rott and Leo Langstein at the Empress Auguste Victoria House and published from 1918 to 1926 in three subsequent editions, each with small changes to the former [39]. The collection of 100 coloured images on the subject of infant care, which covered the main points by photos, graphs and diagrams, could serve for illustrative purposes in the classroom or as a small portable exhibition. The images in the Atlas were scientifically correct and yet easily comprehendible, tying in with traditional ways of representation and aesthetic customs [40]. The contents were displayed vividly, so that they could be understood at first sight. Other modern media were also used: Arthur Schlossmann is said to have produced an educational film about infant care with actors of the Düsseldorf theatre as early as 1912 [41].

The centrepiece of the mothers’ instruction in infant care were breastfeeding recommendations. Breastfeeding was characterized as the “natural way” to feed an infant, being essential for the survival chances and healthy development of infants, the “heart and the milk of a mother” were labelled as “irreplaceable”. A regular schedule of five to six meals per day and a night break was advised. In practical baby care, this was combined with socalled breastfeeding premiums which were systematically increased since 1904 for needy families, either granted by payment in kind or, more common, in cash. Usually the support lasted three to six months [42]. The amount of the grant varied strongly—in the ten largest German cities, payments ranged from 0.25 marks per week in Frankfurt up to five marks in Düsseldorf [43]. In some cities a specific aid in times of risk was granted: in Düsseldorf payment was increased during the summer months in order to counteract the increased risk due of artificial nutrition due to the hot temperatures [44].

However, there were extensive bureaucratic procedures and methods, and often these were downright discriminatory [45-47]. The mothers had to give their consent to unannounced home visits, they had to visit the welfare centre on a weekly basis, in some towns at least fortnightly. To receive a breastfeeding premium, they had to prove that they were breastfeeding, and to demonstrate this, they had to feed the infant before the (male) staff present or bring the used diapers to the centre. Obviously, the approach was based on a widespread lack of knowledge of living conditions in the lower classes. Even if the mothers approved of these new facilities and accepted the associated new values, they could not exploit their potential. For example, a visit to the centre demanded time, hardship and expense. The roads to the centres were long and could often be covered only by expensive public transport. When there were other children, these had to be left unattended at home or taken to the centre as well. In short, these approaches could not work too well, because they ignored the living conditions of the urban working-class family. Neither the budget nor the multiple burdens of a woman as supplementary income earner, housewife and mother were considered. This discrepancy between theory and practice declined in the years of World War I and the Weimar Republic, when infant care was systematically expanded, and was additionally anchored on a state level.

3. INFANT MORTALITY AND BREASTFEEDING RATES DURING WORLD WAR I AND THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC

The effects of World War I on infant mortality are assessed in different ways [48,49]. On the one hand, families experienced difficult life circumstances, rationing and economic hardship, on the other hand the infant care has been strengthened, especially during the war years [50-52]. Given wartime population losses and declining birth rates Arthur Schlossmann called on behalf of the Board of the German Society of Paediatrics (DGfK) on the national government to strengthen infant care: “More than ever it means that we should care about our special field and put emphasis on the importance of paediatrics, because from this field the reconstruction of the German people can be achieved, so that we get over the severe wounds, which the war has inflicted upon us” [53]. The heat wave in 1911 had claimed countless victims among infants, and this had been used as an argument to intensify efforts for the welfare of infants [54]. Similarly there was an impulse to intensify efforts once again after the outbreak of war had caused increasing infant mortality rates. A great many welfare measures thus were taken and the infant mortality rates actually decreased, especially in the cities in the years 1915 and 1916, mostly because more mothers started breastfeeding their babies.

Whereas the first few months of war had led to an initial decrease in breastfeeding frequency and an increase in recorded infant mortality, the ongoing war had caused food shortages and a collapse of the municipal milk supply, forcing mothers to start breastfeeding again [55,56]. This was supported by the introduction of the state maternity benefit. This payment was—unlike the municipal breastfeeding premiums—not hinged on any control visits. Although a claim was based on the father’s or husband’s participation in the war, and not on the status of the mother, the health insurance agencies paid enlarged support during the war, so that self-insured women received these services as well. This strengthened the role of welfare centres because the breastfeeding premiums were distributed by them. This way, the visits to the counselling centres increased significantly and at the same time the mothers were bound to the institution over a longer period of time. The work of the counselling was thus integrated into the public services. This caused an enormous expansion of infant care during World War I. Thus Marie Baum, managing director of the Düsseldorf association of infant welfare, confirmed that the impact of the mothers’ counselling centre had enormously expanded since the introduction of the state maternity benefit. Voluntary visits, which had been campaigned for in vain, had now been achieved by this simple combination of a legal payment with an observation by the counselling centre [57]. Elsewhere, she commented that the shortcomings during the war years caused such a substantial rise in breastfeeding rates which all their campaigning had not been able to achieve [58].

This development marked a significant change in the infant care, because now the state had engaged in substantial financial commitments. Until then, the financial responsibility had always been left to the local authorities, private organisations and health insurance agencies. Although the state maternity benefit was cancelled during the demobilisation, the “Gesetz über Wochenhilfe und Wochenfürsorge” (law on maternity benefit and weekly care) of September 26th 1919 reinstated the provisions of the war time maternity regulations. To complement the maternity benefit a weekly family help was introduced in the Reich Insurance Code (RVO), and at the same time, the reimbursement for impecunious and uninsured mothers prevailed through the state.

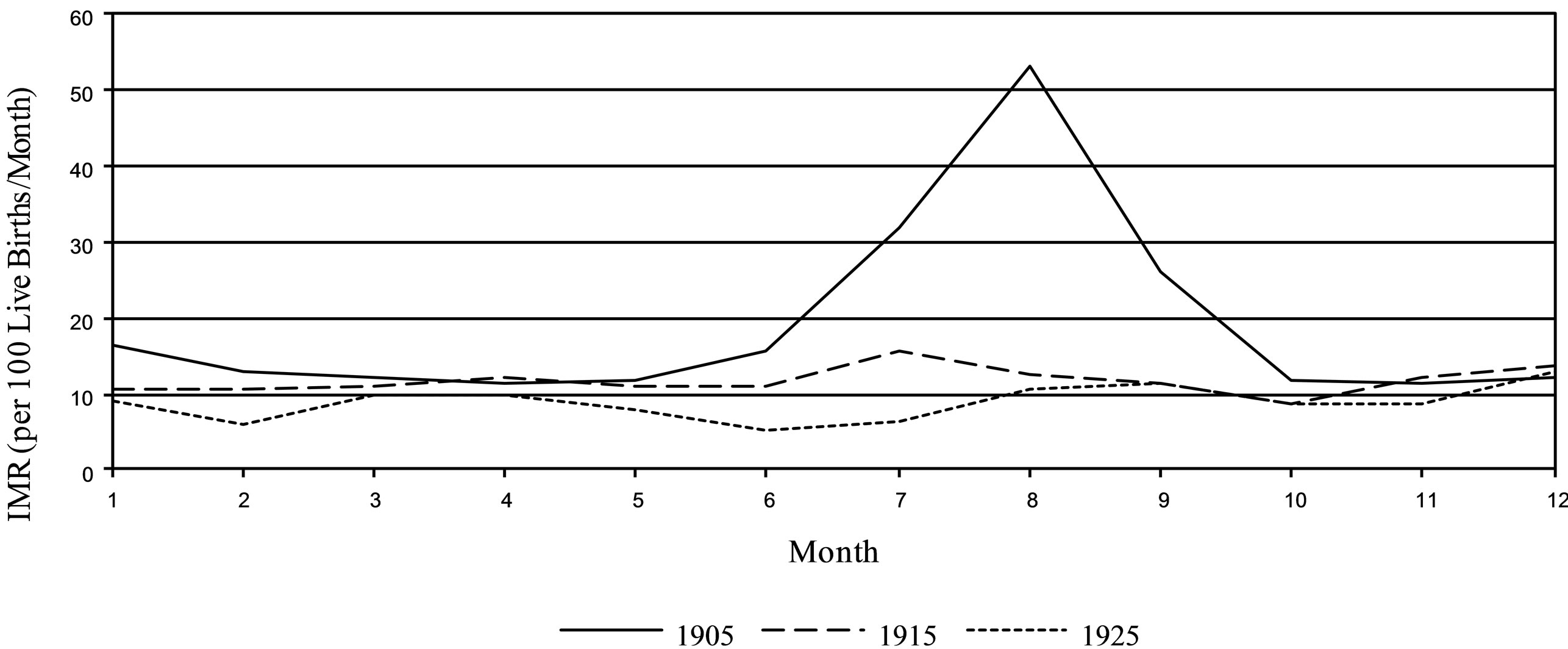

Local contemporaries estimated the impact of these measures as positive. In Munich an investigation of the district association showed that about 70 percent (of 30,000 infants) were breastfed during the years 1916- 1919 [59]. Even from an external perspective these changes were noticed. The English government, which followed with interest the trend of infant mortality rates in the German Empire during the war, expressed a somewhat reserved but generally impressed judgment. The report of the Intelligence Department stated that the breastfeeding rates had increased but—with a stand-offish tone—that the women after the three-month payments would promptly wean their infants (Local Government Board, 1918). Even if this was the case, the overall situation that more mothers breastfed their infants and that the breastfeeding period was at least three months can be assessed quite positively regarding the situation before 1914. Accordingly, the number of deaths due to gastrointestinal diseases also decreased and the infamous summer peak as shown here by the example of Düsseldorf consequently disappeared (Figure 3). The war years showed, in fact, a substantial increase in breastfeeding rates and duration in the German cities with a subsequent drop in infant mortality (Figure 1), to which a combination of relatively cool summers and a sharp decrease in birth rates had contributed additionally.

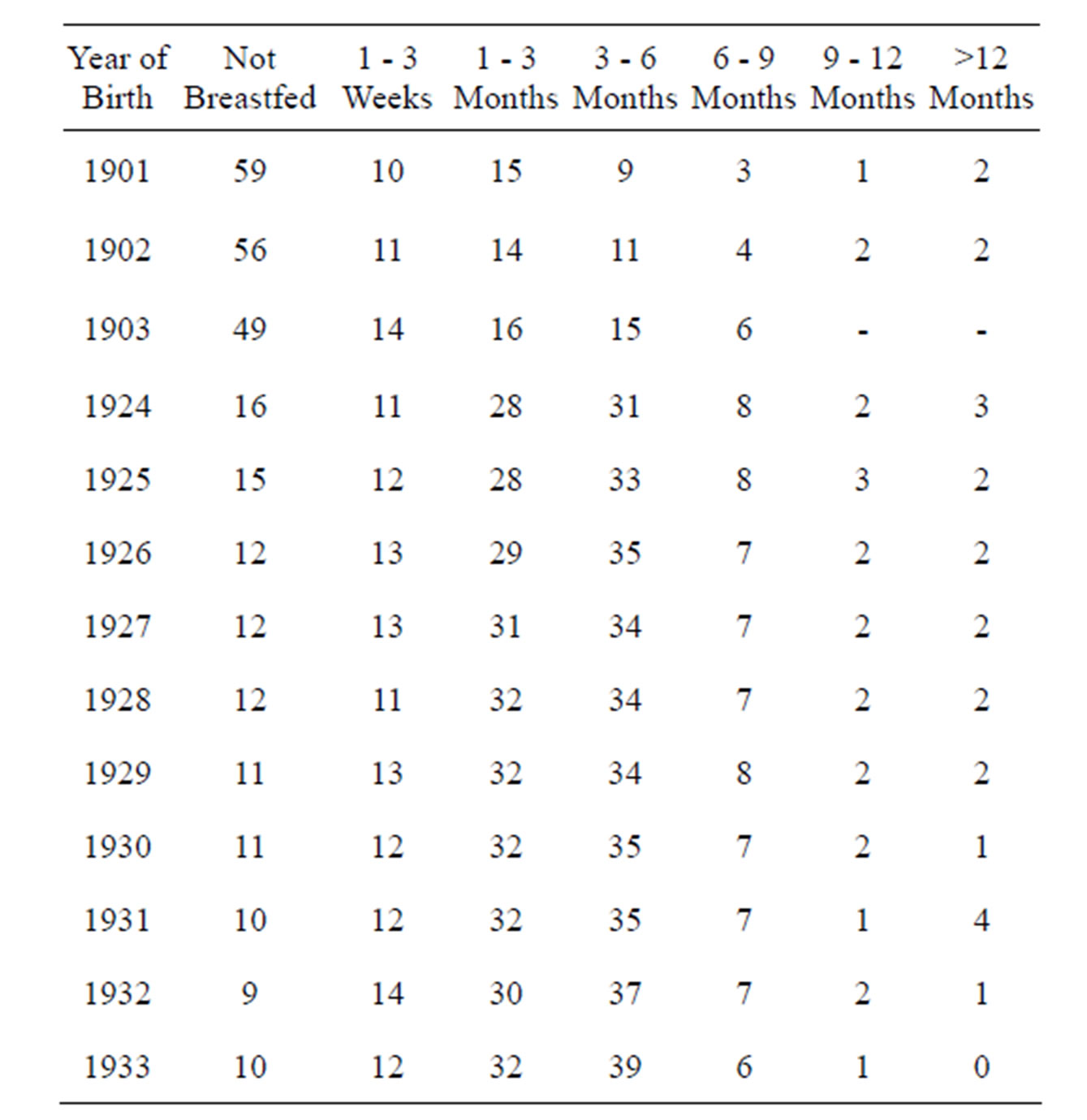

While local and regional studies from the AngloSaxon countries showed that the breastfeeding rates in these countries were decreasing during the first third of the twentieth century [60,61], the developments in Germany seem to have been more complex—although such a statement is so far based on a few local data [62]. In Berlin, a snapshot of from Neukölln for the year 1922 indicates that the breastfeeding rates in comparison to the pre-war period substantially increased: Thus, of 100 pregnancies after a month 87 were breastfed, after three months 55 and after six months still 19 [63]. Given the fact that in Bavaria traditionally low breastfeeding rates prevailed, the development in Munich was even more impressive. The statistics of the Bavarian State Statistical Office surveys carried out a poll regarding breastfeeding behaviour and duration from 1900 to 1904 simultaneously with the smallpox vaccinations. According to this survey about 41 percent of all mothers breastfed their children in 1901, and 59 percent applied entirely artificial nutrition [64]. The statistics of the Bavarian Landesimpfanstalt (state vaccination institute) were continued during the post-war years. Corresponding data was compiled in Munich from the age cohorts from 1924 to 1933 for 38,000 infants. The percentage of artificially fed infants was significantly lower than at the beginning of the century, and amounted to 16 percent in 1924 with a downward trend in subsequent years up to 10 percent in 1933 (Table 1). It shows a continuous increase of the number of infants who were breastfed over 1 - 3 months, and especially those of breastfed infants over 3 - 6 months, while the number of breastfed infants over six months declined.

4. “GERMAN MOTHER, YOU HAVE TO BREASTFEED YOUR BABY”— JOHANNA HAARER AND BREASTFEEDING PROPAGANDA IN NAZI-GERMANY

Breastfeeding propaganda constituted a central element of the Nazi infant care, its importance ranked highly on the national health agenda, which was dominated by racial ideology. The overall enormous breastfeeding rates above 90 percent, however, have to be seen in relative terms, if in addition the duration of breastfeeding is considered—and actually amounted about 70 percent at the time of the first visit at the infant care centre [65]. At the same time the popularisation strategies reached a new dimension. Thus the Munich publisher JF Lehmann, who had published racial hygienic and eugenic writings since World War I and from 1929 openly supported the NSDAP, launched a new popular guide book for young mothers. The publisher supported a young female doctor (specialist in pulmonary medicine,

Figure 3. Infant mortality in Düsseldorf, 1905, 1915 and 1925-seasonal. Sources: Jahresbericht des Statistischen Amts der Stadt Düsseldorf für 1905, 4-5; Jahresbericht der Stadt Düsseldorf für 1915-18, 33 and 37; Jahresbericht der Stadt Düsseldorf für 1925, 22 and 25.

Table 1. Breastfeeding ratio in Munich, 1901-1933 (in Percent).

Source: Bernsee, 1938, 113.

not in paediatrics), who after the birth of their first twin children had written easily comprehensible newspaper articles on the topics of pregnancy, childbirth and infant care: Johanna Haarer (1900-1988). Her guide, “The German mother and her first child”, which was first published in 1934, quickly developed into a best-seller [66]. In educational perspective, historians have postulated that Haarer propagated a repressive and harmful “poisonous paedagogy” or “black paedagogy”, which, regarding bonds between mother and child, had had a longterm influence on early childhood socialisation in German post-war society [67,68]. In a more medical perspective, the content of the guide with its high prevalence on breastfeeding was quite in the tradition of guides from the Weimar Republic and the Empire, but written in a much more aggressive language. In the edition of 1934, relevant passages about breastfeeding read: “German mother, you have to breastfeed your baby! [...] German mother, breastfeeding is not only your duty towards your child, but you also fulfil a racial duty. The ability to breastfeed is one of the most valuable genetic properties” [69]. The basic argument referred to the infant’s health and the reduced risk of premature death: “Bottle-fed babies get ill 10 times more frequently than breastfed babies, and among infants who died only 1 out of 6 was breastfed” [70].

Perhaps the reason for Haarer’s success cannot solely be attributed to the ideological sphere, as has been emphasised in the research literature, but might also be due to the fact that she addresses some hitherto rarely discussed details (e.g. about the value and importance of the first milk) and also particularly addresses the needs and problems of young mothers (such as breastfeeding difficulties). As the title of “The German mother and her first child” indicated, there was a stronger focus on the mother. No longer the “baby atlas”, the infant handbooks were focussed upon, but the young mother and her first child were addressed. The emphasis on the first child also suggested that this experience and knowledge could be learned and adopted and were not exclusively natural, innate instincts—even though Haarer regarded the ability to breastfeed generally as hereditary.

Even after the Second World War Johanna Haarer’s book remained a best-seller in the Federal Republic of Germany until the late 1980s, reaching many editions, selling more than 1.2 million copies in total. In the Soviet zone of occupation in 1946 it was put on the list of banished books [71,72]. In Western Germany the title was slightly modified into “The mother and her first child”, the linguistic style revised, elements of racial ideology and rhetoric were eliminated, while the idea of breastfeeding was still strictly promoted. In the edition of 1965 this read: “During the first months, (your mother’s milk) provides all the food your child requires for its healthy development [...]” [73]. The argument remains rather imprecise and almost vague: “Breastfeeding is good for your own health. [...] For the child, the advantages of breastfeeding cannot be overestimated.” [...] “Bottle-fed infants get ill more often. Certain diseases do not occur, or only in a mild form, such as an infant seizures and rickets” [74].

5. 1960/70s COLD WAR AND THE “BREASTFEEDING REVOLT”

While in the time of the Empire and the Weimar Republic there were only isolated voices that gave moderate comments on infant feeding or uttered even a relaxation of previously recommended rigid intervals for breastfeeding, these schematic dietary recommendations were softened in the 1960s and 1970s, according to advances in nutritional science—also supported by pressure from the women’s movement. Instead, a self-demand feeding concept developed in the USA during the 1940s, was propagated and popularised. This programme promised benefits for both the infant and the mother and was already realised during the hospital stay by accommodation of mother and child in the same room (rooming-in). This diametrically opposed change quickly entered into the paediatric handand textbooks, as the nutritional physiology models could not be countered [75]. Also in the popular West German breastfeeding handbooks of the 1960/1970s, the strong emphasis on breastfeeding as a condition for the healthy development of infants was softened in favour of artificial feeding—already from the third or fourth week after birth. At the same time, the international bestseller “The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care” by the famous American pediatrician Benjamin Spock was translated into German and helped to spread a more liberal attitude towards infants and children. Spock strongly supported breastfeeding and advocated a deeper understanding of the children’s needs and family dynamics while keeping the balance between permissive approach and an educational rigor. Conversely, the term of so-called breastfeeding fanatics and breastfeeding fanaticism came up, stressing that too much pressure on mothers who were physically unable to breastfeed which might evoke feelings of guilt or inadequacy. Simultaneously, the scientific research developed baby food into a high-tech product that large food companies globally promoted with sophisticated advertising campaigns. The question of “breast or bottle?” became increasingly important for parents also as a question of lifestyle [76]: The option of artificial food, for example, enabled a stronger inclusion of the father’s role. Furthermore, as during the 1960s and 1970s progress and technology gained more importance in society, the propagation of an early change to artificial infant nutrition fell on fertile ground. In addition, in the context of the emerging environmental movement the potential toxic contamination of breast milk (especially by DDT or dioxin) became an issue. It was discussed both in science—1978 the socalled “residue commission” of the DFG (German research council) reported on pollutant concentrations in breast milk—as well as in arts, culture and society or by the media.

Only in the last decades of the twentieth century resistance increased to the sometimes even aggressive marketing methods of food companies for artificial feeding of infants, especially in developing countries where food companies tried to open up new markets, not least because of declining birth rates in industrialised nations. Accordingly, the debates became internationalised. In 1974, the English charity society “War on Want” published a study, “The baby killer”, which was based mainly on studies in Africa and postulated strong negative effects of bottle feeding on the health and survival of infants and young children. When in the same year the Swiss “Working Group Third World” of Bern translated this study and published it under the provocative title “Nestlé Kills Babies”, the Nestlé Company filed a complaint and went to court. The company wanted to counteract the title of the booklet and also the statements that Nestlé was responsible for the deaths of thousands of babies, Nestlé’s marketing was unethical and Nestlé’s sale staff was dressed like nurses. The Nestlé process ended in 1976 with a conviction of the accused, although Nestlé in the run-up to the process dropped three of the four charges. Members of the working group were sentenced only for the title of the publication and charged with a rather symbolic penance of 300 Swiss Francs per person. In addition, the judge advised the company to rethink its marketing practices. In the media this was spread as a moral victory for the Third World group [77]. In 1984, the company finally agreed to the guidelines established by the WHO and UNICEF in 1981 of 118 WHO member states (only the delegates of the United States were against it), to comply with the “International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes”. At the same time, the experts returned to classic views since the 1980s and referred increasingly to the health benefits of breastfeeding and advocated almost unanimously a period of at least six months of breastfeeding.

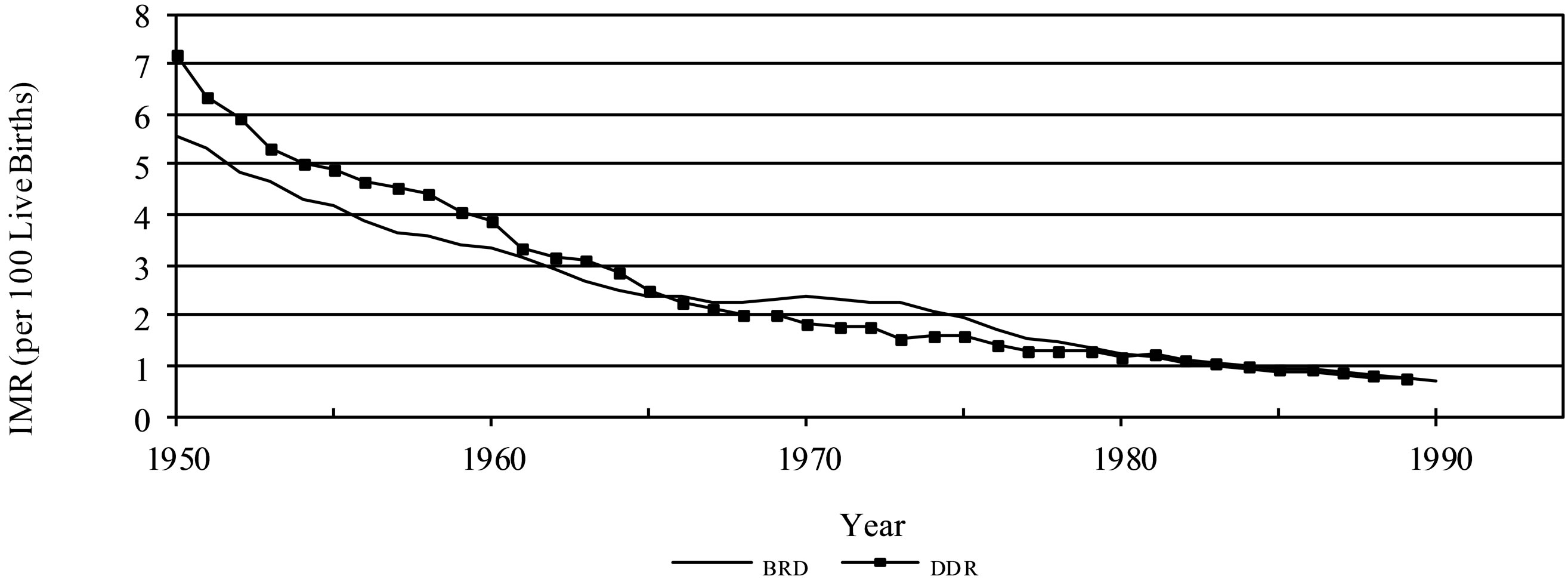

As the infant mortality serves as an indicator of prosperity and advance of a society, the different levels of infant mortality in Eastern and Western Germany were used as an argument in the ideological conflicts of the Cold War propaganda (Figure 4). West Germany interpreted the lower rates in the GDR during the late 1960s and early 1970s merely as related to newly introduced

Figure 4. Infant mortality in Western and Eastern Germany, 1950-1989. Sources: StJBBRD; StJBDDR.

twofold criteria for live birth in East Germany [78]. By contrast, in East Germany the lower rates were attributed to the local intensive prevention and care, which however, in the long run, was esteemed not to be able to keep up with the western high-tech medicine. This, in turn, was considered to be the explanation why infant mortality rates in the west declined below the rates in the east [79,80].

Traditionally, the infant mortality was used as an argument to convince the mothers of the benefits of breastfeeding. For example, social hygienic approaches of the Weimar Republic were initially resumed in the GDR. But then again artificial baby food products manufactured in state-owned enterprises could hardly be declared unsuitable. Rather, it was pointed out that “[...] also an artificial diet now ensures the success of your child’s prospering”, and especially in the 1970s, the products of Milasan or KI-NA were recommended [81,82]. Despite this, breastfeeding in the GDR was still considered to be more favourable, and in this context it was pointed out that surplus milk could be given to other mothers out of solidarity, or picked up by a milk collecting point for which a fee was paid (milk bank). Far greater ideological difficulties and discussions arose from the “ad libitum breastfeeding” concept. In the late 1970s this led to comments like the following: “Some paediatricians in the US have even made it a theory and recommend to breastfeed according to the demand of the children. But all this has not proven to be favourable. The 4-hour intervals and the long rest during the night have proven favourable for the infant’s prospering” [83]. Benjamin Spock’s book of baby and child care was available in eastern Germany (GDR), and was also translated into Russian and several other eastern European languages [84]. In this context, his critical attitude towards the Vietnam War might have supported the vast distribution of his work in communist countries.

6. CONCLUSION

Recent studies suggest that breastfeeding rates in Germany have been increasing since the 1980s, and are now above 90 percent, although the recommended duration of breastfeeding of six months is not met by far. Whereas 68 percent of the 1998-2001 birth cohorts were still being breastfed for four months, the duration of breastfeeding declined in subsequent years [85]. Therefore, the National Breastfeeding Committee announced: “Breastfeeding—it might be a little longer!” In international comparison, the latest German breastfeeding rates are particularly low compared to the Scandinavian countries [86]. According to recent research, there is the need for further sustained breastfeeding campaigns. From a global perspective, WHO and UNICEF have consistently emphasised the need for breastfeeding. The main argument is still the infant mortality—as it was in Germany in the early twentieth century. This breastfeeding propaganda is now especially important for developing countries, where the percentage of exclusively breastfed children under the age of six months is only 38 percent. Yet, it is also important for infants in other parts of the world: “But non-breastfed children in industrialised countries are also at a greater risk of dying—a recent study of post-neonatal mortality in the United States found a 25% increase in mortality among non-breastfed infants” [87]. Infant nutrition, breastfeeding propaganda and infant mortality are still pressing issues—and a medical and social-historical perspective can give insights to the development of modern health conditions, the development of paediatrics and the fundamental social change in the perception of mother and child.

REFERENCES

- (2013) Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung, Sterblichkeit, http://www.bib-demografie.de/DE/ZahlenundFakten/08/sterblichkeit_node.html

- (2013) UNICEF, children in an urban world, the state of the world’s children 2012, statistics, basic indicators. http://www.unicef.org/sowc2012/statistics.php

- Ariès, P. (1975) Geschichte der kindheit. Hanser, Munich.

- Badinter, E. (2010) Der konflikt: Die frau und die mutter. Beck, Munich.

- Bible: Job 1.21.

- Vögele, J. (2001) Sozialgeschichte städtischer gesundheitsverhältnisse während der urbanisierung. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin.

- Vögele, J. (2009) Wenn das leben mit dem tod beginnt— Säuglingssterblichkeit und gesellschaft in historischer perspektive. In: T. Halling, S. Fehlemann, & J. Vögele Eds., Macht Ein Langes Leben Sinn? Der Vorzeitige Tod Als Identitäts und Sinnstiftungsmuster in Historischer Perspektive, Center Historical Social Research, Cologne, 66-82.

- Vögele 2001, 120.

- Vögele, J., Halling, T. and Rittershaus, L. (2010) Entwicklung und popularisierung ärztlicher stillempfehlungen in deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert. Medizinhistorisches Journal, 45, 222-250.

- Spree, R. (1981) Soziale ungleichheit vor krankheit und tod. Zur sozialgeschichte des gesundheitsbereichs im deutschen kaiserreich. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen.

- Kintner, H. J. (1982) The determinants of infant mortality in Germany from 1871 to 1933. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Imhof, A.E. (1994) Lebenserwartungen in deutschland, norwegen und schweden im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Akademie-Verl, Berlin.

- Spree, R. (1995) On infant mortality change in Germany since the early 19th century (Münchener Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Beiträge, No. 95-03). Munich: Univ.

- Haines, M. and Vögele, J. (2000) Infant and child mortality in Germany, 19th-20th centuries. Colgate University, Hamilton.

- Vögele, 2001.

- Seidler, E. (1976) Die ernährung der kinder im 19. Jahrhundert. In: E. Heischkel-Artelt, Ed., Ernährung und Ernährungslehre im 19. Jahrhundert, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 288-302.

- Müller, R. (2000) Von der wiege zur bahre. Weibliche und männliche lebensläufe im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert am Beispiel Stuttgart-Feuerbach. HohenheimVerl, Stuttgart.

- Vögele 2001, 154.

- Vögele 2001, 153-161.

- Spree 1981, 68 and 174.

- Baum, M. (1917) Grundriss der säuglingsfürsorge. 5th and 6th Edition, Bergmann, Wiesbaden.

- Imhof, A.E. (1981) Unterschiedliche säuglingssterblichkeit in Deutschland, 18. bis 20. Jahrhundert-Warum? Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft 7-3, 343-382.

- Vögele 2001, 318.

- Vögele 2001, 155.

- Selter, P. (1902) Die nothwendigkeit der mutterbrust für die ernährung der säuglinge. Centralblatt Für Allgemeine Gesundheitspflege, 21, 377-392.

- Prinzing, F. (1930-1931) Handbuch der medizinischen statistik. 2nd Edition, Fischer, Jena.

- Böckh, R. (1887) Die statistische messung des einflusses der Emährungsweise der kleinen kinder auf die sterblichkeit derselben. VI. Internationaler Congress für Hygiene und Demographie zu Wien 1887, Issue No. 28. Vienna, 3-48.

- Böckh, R. (1887). Tabellen betreffend den einfluss der ernährungsweise auf die kindersterblichkeit. Bulletin de l’Institute International de Statistique, 2, 14-24.

- Silbergleit, H. (1911) Säuglings und säuglingssterblichkeitsstatistik. In: F. Zahn, Ed., Die Statistik in Deutschland Nach Ihrem Heutigen Stand, Schweitzer, Munich, 434-455.

- Vögele, J. (1998) Urban mortality change in England and Germany, 1870-1910. Liverpool UP, Liverpool.

- Stöckel, S. (1996). Säuglingsfürsorge zwischen sozialer hygiene und eugenik. Das beispiel berlins im kaiserreich und in der weimarer republik. De Gruyter, Berlin.

- Vögele 2001.

- Trumpp, J. (1908) Die milchküchen und beratungsstellen im dienste der säuglingsfürsorge. Zeitschrift für Säuglingsfürsorge, 2, 119-137.

- Frevert, U. (1984) The civilizing tendency of hygiene. working-class women under medical control in imperial Germany. In: J. C. Fout, Ed., German Women in the Nineteenth Century. A Social History, Holmes & Meier, New York, 320-344.

- Fehlemann, S. (2009) Armutsrisiko mutterschaft, mütterund säuglingsfürsorge im rheinisch-westfälischen industriegebiet 1890-1924. Klartext, Essen.

- Schlossmann, A. (1912) Buchbesprechung säuglingspflegefibel von schwester Antonie Zerwer. Mit einem vorwort von Prof. Langstein (Berlin, Verlag Julius Springer). Zeitschrift für Säuglingsfürsorge, 6, 233-234.

- Kollwitz, H. (1925) Hygienische volksbelehrung durch das Bild. Zeitschrift für Schulgesundheitspflege und Soziale Hygiene, 9, 393-396.

- Brüning, H. (1911) Ueber ausstellungen für säuglingsfürsorge. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, 37, 1642-1643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1130918

- Langstein, L. and Rott, F. (1918) Atlas der hygiene des säuglings und des kleinkindes für unterrichtsund Belehrungszwecke (2nd Edition, 1922; 3rd Edition, 1926). Springer, Berlin.

- Rittershaus, L. (2013) Visualisierung in der säuglingsfürsorge anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts: Der “Atlas der hygiene des säuglings und kleinkindes”. Cuvillier, Göttingen.

- Vögele, J. (2010) “Has all that has been done lately for infants failed?”1911, Infant Mortality and Infant Welfare in Early Twentieth-Century Germany. Annales de Démographie Historique, 2, 131-146.

- Rott, F. (1914) Umfang, bedeutung und ergebnisse der unterstützungen an stillende mütter. Schoetz, Berlin.

- Vögele 2001, 384.

- Rott 1914, 26.

- Frevert 1984.

- Vögele 2001, 386-393.

- Fehlemann 2009.

- Dwork, D. (1987) War is good for babies und other young children. A history of the infant and child welfare movement in England 1898-1918. Travistock, London.

- Winter, J. and Cole, J. (1993) Fluctuations in infant mortality rates in Berlin during and after the First World War. European Journal of Population, 9, 235-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01266019

- Local Government Board. (1918) Infant welfare in Germany during the war. Report prepared in the Intelligence Department of the local government board, London.

- Butke, S. & Kleine, A. (2004) Der Kampf für den gesunden nachwuchs. Geburtshilfe und säuglingsfürsorge im Deutschen Kaiserreich. Ardey, Münster.

- Fehlemann 2009.

- Schlossmann, A. (1918) Kinderkrankheiten und Krieg. Verhandlungen der 31. Versammlung der Gesellschaft für Kinderheilkunde, Leipzig 1917 (pp. 1-28) Bergmann, Wiesbaden, 28.

- Vögele 2010.

- Bericht über das neunte geschäftsjahr des vereins für säuglingsfürsorge im regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf 1915- 1916. (1915) Düsseldorf, 8.

- Woelk, W. (2000) Von der Gesundheitsfürsorge zur wohlfahrtspflege: Gesundheitsfürsorge im rheinischwestfälischen Industriegebiet am beispiel des vereins für säuglingsfürsorge im regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf. In: Vögele, J. and Woelk, W. Eds., Stadt, Krankheit und Tod. Geschichte der städtischen Gesundheitsverhältnisse während der Epidemiologischen Transition (vom 18. bis ins frühe 20. Jahrhundert), Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, 339-359.

- Baum 1917, 188.

- Bericht 1915/16, 65.

- Hecker, R. (1923) Studien über sterblichkeit, todesursachen und ernährung Münchener säuglinge. Archiv für Hygiene, 93, 280-294.

- [61] Apple, R. D. (1987) Mothers and Medicine: A Social History of Infant Feeding, 1890-1950. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

- [62] Wolf, J. H. (2001) Don’t kill your baby: Public health and the decline of breastfeeding in the nineteenth and twentyeth centuries. Ohio State University Press, Columbus.

- [63] Kintner, H. J. (1985) Trends and regional differences in breastfeeding in Germany from 1871 to 1937. Journal of Family History, 10, 163-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/036319908501000203

- [64] Seine majestät das kind. Ein ratgeber für Mütter, solche die es werden wollen und alle, die das kind lieben. (1928) Eigenbrödler, Berlin.

- [65] Seidlmayer, H. (1937) Geburtenzahl, säuglingssterblichkeit und stillung in München in den letzten 50 Jahren. MD Thesis, Univ., Munich.

- [66] Kollmann, A. (1938-1939), Stillverhältnisse und stillprobleme, Der Öffentliche Gesundheitsdienst, 4, Teilausgabe A, 386-394.

- [67] Dill, G. (1999) Nationalsozialistische säuglingspflege. Eine frühe erziehung zum massenmenschen. Enke, Stuttgart.

- [68] Chamberlain, S. (1997) Adolf Hitler, die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind: Über zwei NS-Erziehungsbücher. Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen.

- [69] Gebhardt, M. (2009) Die Angst vor dem kindlichen Tyrannen. Eine geschichte der erziehung im 20. jahrhundert. Deutsche Verlag-Anstalt, Munich.

- [70] Haarer, J. (1934) Die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind. 1st Edition, Lehmann, Munich. 102.

- [71] Haarer 1934, 103.

- [72] Benz, U. (1988) Brutstätten der nation. “Die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind” oder der anhaltende Erfolg eines Erziehungsbuches. Dachauer Hefte, 4, 144-163.

- [73] Haarer, J. and Haarer, G. (2012) Die deutsche Mutter und ihr letztes Kind-Die Autobiografien der erfolgreichsten NS-Erziehungsexpertin und ihrer jüngsten Tochter, (Ed. and introduced by Rose Ahlheim.) Offizin, Hannover:.

- [74] Haarer, J. (1965) Die Mutter und ihr erstes Kind. Gerber, Munich. 122.

- [75] Haarer 1965, 123.

- [76] Manz, F., Manz, I. and Lennert, T. (1997) Zur geschichte der ärztlichen stillempfehlungen in Deutschland. Monatsschrift für Kinderheilkunde, 145, 572-587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001120050155

- [77] Heimerdinger, T. (2009) Brust oder flasche? Säuglingsernährung und die Rolle von Beratungsmedien. In: Simon, M. et al. Eds., Bilder, Bücher, Bytes. Zur Medialität des Alltags, 36. Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde in Mainz vom 23. bis 26. September 2007, Waxmann, Münster, 100-110

- [78] The formula flap, Time Magazine, July 12, 1976

- [79] Whereas in the BRD since 1957 pulmonary respiration, heart beat or pulsation of the umbilical cord was considered as a sign of life, in the GDR since 1961 at least two criteria, pulmonary respiration and heart beat, were considered to be necessary to be relevant for the statistical definition as a life birth, cf. Mallik, S. (2007) Die Entwicklung der Säuglingssterblichkeit im Fokus gesellschaftlicher Bedingungen. Ein Ost-West-Vergleich. IFAD, Berlin, 23.

- [80] Mallik 2007.

- [81] Wauer, R. and Schmalisch, G. (2008) Die entwicklung der kinder-, säuglingsund neugeborenensterblichkeit in Deutschland seit gründung der Deutschen gesellschaft für kinderheilkunde. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderund Jugendmedizin E.V. Ed., 125 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderund Jugendmedizin e.V., Heenemann, Berlin, 133-143.

- [82] Dittmer, A. and Gmyrek, D. (1973) Der säugling. Wissenswertes über das erste lebensjahr. Verlag Volk und Gesundheit, Berlin. 3.

- [83] Mann, K. et al. (1977) Kleine Kinder-keine Sorgen. Verlag Volk und Gesundheit, Berlin, 81-82.

- [84] Mann et al. 1977, 71.

- [85] Kardauskaite-Jacobs, L. (2012) Ärztliche Stillempfehlungen in Litauen, 1945-1991. Unpubl. Magisterarbeit. Univ., Düsseldorf. 43.

- [86] Lange, C., Schenk, L. and Bergmann, R. (2007) Verbreitung, dauer und zeitlicher trend des stillens in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Kinderund Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 50, 624-633. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-007-0223-9

- [87] Sievers, E. and Kersting, M. (2011) Deutschland braucht ein nationales stillmonitoring. http://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/232/deutschland_braucht_ein_nationales_stillmonitoring.pdf

- [88] UNICEF. (2012) Breastfeeding. Impact on child survival and global situation. http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_24824.html

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Apple, R.D. (1987). Mothers and Medicine: A Social History of Infant Feeding, 1890-1950. Madison: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

Ariès, P. (1975). Geschichte der Kindheit (1st German ed.). Munich: Hanser.

Badinter, E. (2010). Der Konflikt: Die Frau und die Mutter. Munich: Beck.

Baum, M. (1917). Grundriss der Säuglingsfürsorge (5th and 6th ed.). Wiesbaden: Bergmann.

Benz, U. (1988). Brutstätten der Nation. “Die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind” oder der anhaltende Erfolg eines Erziehungsbuches. Dachauer Hefte, 4, 144-163.

Bericht über das achte Geschäftsjahr des Vereins für Säuglingsfürsorge im Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf 1914/ 15. (1915). Düsseldorf.

Bericht über das neunte Geschäftsjahr des Vereins für Säuglingsfürsorge im Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf 1915/ 16. (1915). Düsseldorf.

Bernsee, H. (1938). Kampf dem Säuglingstod. An der Wiege des Lebens der Nation. Munich: Lehmann.

Böckh, R. (1887). Die statistische Messung des Einflusses der Ernährungsweise der kleinen Kinder auf die Sterblichkeit derselben. VI. Internationaler Congress für Hygiene und Demographie zu Wien 1887, Issue no. 28. Vienna, 3-48.

Böckh, R. (1887a). Tabellen betreffend den Einfluss der Ernährungsweise auf die Kindersterblichkeit. Bulletin de l’Institute International de Statistique, 2:2, 14-24.

Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung, Sterblichkeit, last access 27.02.2013. http://www.bib-demografie.de/DE/ZahlenundFakten/08/sterblichkeit_node.html

Butke, S. and Kleine, A. (2004). Der Kampf für den gesunden Nachwuchs. Geburtshilfe und Säuglingsfürsorge im Deutschen Kaiserreich. Münster: Ardey.

Chamberlain, S. (1997). Adolf Hitler, die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind. Über zwei NS-Erziehungsbü- cher. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verl.

Dill, G. (1999). Nationalsozialistische Säuglingspflege. Eine frühe Erziehung zum Massenmenschen. Stuttgart.

Dittmer, A. and Gmyrek, D. (1973). Der Säugling. Wissenswertes über das erste Lebensjahr, Berlin: Verl. Volk u. Gesundheit.

Dwork, D. (1987). War Is Good for Babies und Other Young Children. A History of the Infant and Child Welfare Movement in England 1898-1918. London: Travistock.

Fehlemann, S. (2009). Armutsrisiko Mutterschaft, Mütterund Säuglingsfürsorge im rheinisch-westfälischen Industriegebiet 1890-1924. Essen: Klartext.

Frevert, U. (1984). The Civilizing Tendency of Hygiene. Working-Class Women under Medical Control in Imperial Germany. In J. C. Fout (Ed.), German Women in the Nineteenth Century. A Social History (pp. 320- 344). New York: Holmes & Meier.

Gebhardt, M. (2009). Die Angst vor dem kindlichen Tyrannen. Eine Geschichte der Erziehung im 20. Jahrhundert. Munich: Deutsche Verl.-Anst.

Haarer, J. (1st ed.) (1934). Die deutsche Mutter und ihr erstes Kind. Munich: Lehmann.

Haarer, J. (1965). Die Mutter und ihr erstes Kind. Munich: Gerber.

Haarer, J. and Haarer, G. (2012). Die deutsche Mutter und ihr letztes Kind—Die Autobiografien der erfolgreichsten NS-Erziehungsexpertin und ihrer jüngsten Tochter, ed. and introduced by Rose Ahlheim. Hannover: Offizin-Verl.

Haines, M. and Vögele, J. (2000). Infant and Child Mortality in Germany, 19th-20th Centuries (Colgate University, Department of Economics, Working Paper Series 100-10). Hamilton, NY.

Hecker, R. (1923). Studien über Sterblichkeit, Todesursachen und Ernährung Münchener Säuglinge. Archiv für Hygiene, 93, 280-294.

Heimerdinger, T. (2009). Brust oder Flasche? Säuglingsernährung und die Rolle von Beratungsmedien. In M. Simon et al. (Eds.), Bilder, Bücher, Bytes. Zur Medialität des Alltags, 36. Kongress der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde in Mainz vom 23. bis 26. September 2007 (pp. 100-110). Münster: Waxmann.

Imhof, A. E. (1981) Unterschiedliche Säuglingssterblichkeit in Deutschland, 18. bis 20. Jahrhundert—Warum? Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft 7-3, 343- 382.

Imhof, A. E. (Ed.) (1994). Lebenserwartungen in Deutschland, Norwegen und Schweden im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Berlin: Akademie-Verl.

Jahresbericht des Statistischen Amts der Stadt Düsseldorf (1905, 1915-18, 1925). Düsseldorf.

Kardauskaite-Jacobs, L. (2012). Ärztliche Stillempfehlungen in Litauen, 1945-1991. Unpubl. Magisterarbeit. Düsseldorf: Univ.

Kintner, H. J. (1982). The Determinants of Infant Mortality in Germany from 1871 to 1933, unpublished Ph.D. thesis. Ann Arbor: Univ. Michigan.

Kintner, H. J. (1985). Trends and Regional Differences in Breastfeeding in Germany from 1871 to 1937. Journal of Family History, 1985, 163-182.

Kollmann, A. (1938/39), Stillverhältnisse und Stillprobleme, Der Öffentliche Gesundheitsdienst, 4, Teilausgabe A, 386-394.

Kollwitz, H. (1925). Hygienische Volksbelehrung durch das Bild. Zeitschrift für Schulgesundheitspflege und soziale Hygiene, 9, 393-396.

Lange, C., Schenk, L. and Bergmann, R. (2007). Verbreitung, Dauer und zeitlicher Trend des Stillens in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Kinderund Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt, 50, 624-633.

Langstein, L. and Rott, F. (1918 [repr. Lübeck 1989]), Atlas der Hygiene des Säuglings und des Kleinkindes für Unterrichtsund Belehrungszwecke. (2nd ed. 1922, 3rd ed. 1926). Berlin: Springer.

Local Government Board (1918). Infant Welfare in Germany during the War. Report prepared in the Intelligence Department of the Local Government Board. London.

Mallik, S. (2007). Die Entwicklung der Säuglingssterblichkeit im Fokus gesellschaftlicher Bedingungen. Ein Ost-West-Vergleich. Berlin: IFAD.

Mann, K., et al. (1977). Kleine Kinder—keine Sorgen, Berlin: Verl. Volk u. Gesundheit.

Manz, F., Manz, I. and Lennert, T. (1997). Zur Geschichte der ärztlichen Stillempfehlungen in Deutschland. Monatsschrift für Kinderheilkunde, 145, 572-587.

Müller, R. (2000). Von der Wiege zur Bahre. Weibliche und männliche Lebensläufe im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert am Beispiel Stuttgart-Feuerbach, Stuttgart: Hohenheim-Verl.

Prinzing, F. (1930-31). Handbuch der medizinischen Statistik. (2nd ed.), Jena: Fischer.

Rott, F. (1914). Umfang, Bedeutung und Ergebnisse der Unterstützungen an stillende Mütter. Berlin: Schoetz.

Schlossmann, A. (1912). Buchbesprechung Säuglingspflegefibel von Schwester Antonie Zerwer. Mit einem Vorwort von Prof. Langstein (Berlin, Verlag Julius Springer). Zeitschrift für Säuglingsfürsorge, 6, 233-234.

Schlossmann, A. (1918). Kinderkrankheiten und Krieg. Verhandlungen der 31. Versammlung der Gesellschaft für Kinderheilkunde, Leipzig 1917 (pp. 1-28). Wiesbaden: Bergmann.

Seidler, E. (1976). Die Ernährung der Kinder im 19. Jahrhundert. In: E. Heischkel-Artelt (Ed.), Ernährung und Ernährungslehre im 19. Jahrhundert (pp. 288-302). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Seidlmayer, H. (1937). Geburtenzahl, Säuglingssterblichkeit und Stillung in München in den letzten 50 Jahren. MD thesis, Munich: Univ.

Seine Majestät das Kind. Ein Ratgeber für Mütter, solche die es werden wollen und alle, die das Kind lieben. (1928). Berlin: Eigenbrödler.

Selter, P. (1902). Die Nothwendigkeit der Mutterbrust für die Ernährung der Säuglinge. Centralblatt für allgemeine Gesundheitspflege, 21, 377-392.

Sievers, E. and Kersting, M. Deutschland braucht ein Nationales Stillmonitoring, download 29.11.2011. http://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/343/deutschland_braucht_ein_nationales_stillmonitoring.pdf

Silbergleit, H. (1911). Säuglingsund Säuglingssterblichkeitsstatistik. In: F. Zahn (Ed.), Die Statistik in Deutschland nach ihrem heutigen Stand, Vol. 1 (pp. 434-455). Munich: Schweitzer.

Spree, R. (1981). Soziale Ungleichheit vor Krankheit und Tod. Zur Sozialgeschichte des Gesundheitsbereichs im Deutschen Kaiserreich, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Spree, R. (1995). On Infant Mortality Change in Germany since the Early 19th Century (Münchener Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Beiträge, No. 95-03). Munich: Univ.

Statistisches Bundesamt, Destatis, Lebenserwartung in Deutschland. Durchschnittliche und fernere Lebenserwartung nach ausgewählten Altersstufen, last access 29. 11.2011. https://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Inter-net/DE/Content/Statistiken/Bevoelkerung/GeburtenSterbefaelle/Tabellen/Content50/LebenserwartungDeutschland,te mplateId=renderPrint.psml

Stöckel, S. (1996). Säuglingsfürsorge zwischen sozialer Hygiene und Eugenik. Das Beispiel Berlins im Kaiserreich und in der Weimarer Republik, Berlin: De Gruyter.

Trumpp, J. (1908). Die Milchküchen und Beratungsstellen im Dienste der Säuglingsfürsorge. Zeitschrift für Säuglingsfürsorge, 2, 119-137.

UNICEF, Breastfeeding. Impact on child survival and global situation, last access 29.11.2011. http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_24824.html

UNICEF, Children in an Urban World, The State of the Worlds Children 2012, Statistics, Basic Indicators, download 27.02.2013. http://www.unicef.org/sowc2012/statistics.php

Vögele, J. (1998). Urban Mortality Change in England and Germany, 1870-1910. Liverpool: Liverpool UP.

Vögele, J. (2001). Sozialgeschichte städtischer Gesundheitsverhältnisse während der Urbanisierung, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Vögele, J. (2009). Wenn das Leben mit dem Tod beginnt—Säuglingssterblichkeit und Gesellschaft in historischer Perspektive. In: T. Halling, S. Fehlemann and J. Vögele (Eds.), Macht ein langes Leben Sinn? Der vorzeitige Tod als Identitätsund Sinnstiftungsmuster in historischer Perspektive (pp. 66-82). Cologne: Center Historical Social Research.

Vögele, J. (2010). “Has all that has been done lately for infants failed?”—1911, Infant Mortality and Infant Welfare in Early Twentieth-Century Germany. Annales de démographie historique, 2, 131-146.

Vögele, J., Halling, T. and Rittershaus, L. (2010). Entwicklung und Popularisierung ärztlicher Stillempfehlungen in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert. Medizinhistorisches Journal, 45, 222-250.

Wauer, R. and Schmalisch, G. (2008). Die Entwicklung der Kinder-, Säuglingsund Neugeborenensterblichkeit in Deutschland seit Gründung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinderheilkunde. In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderund Jugendmedizin e.V. (Ed.), 125 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderund Jugendmedizin e.V. (pp. 133-143). Berlin: Heenemann.

Winter, J. and Cole, J. (1993). Fluctuations in Infant Mortality Rates in Berlin during and after the First World War. European Journal of Population, 9, 235-263.

Woelk, W. (2000). Von der Gesundheitsfürsorge zur Wohlfahrtspflege: Gesundheitsfürsorge im rheinischwestfälischen Industriegebiet am Beispiel des Vereins für Säuglingsfürsorge im Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf. In: J. Vögele and W. Woelk (Eds.), Stadt, Krankheit und Tod. Geschichte der städtischen Gesundheitsverhältnisse während der Epidemiologischen Transition (vom 18. bis ins frühe 20. Jahrhundert) (pp. 339-359). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Wolf, J. H. (2001). Don’t Kill Your Baby: Public Health and the Decline of Breastfeeding in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Columbus: Ohio State Univ. Press.