Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

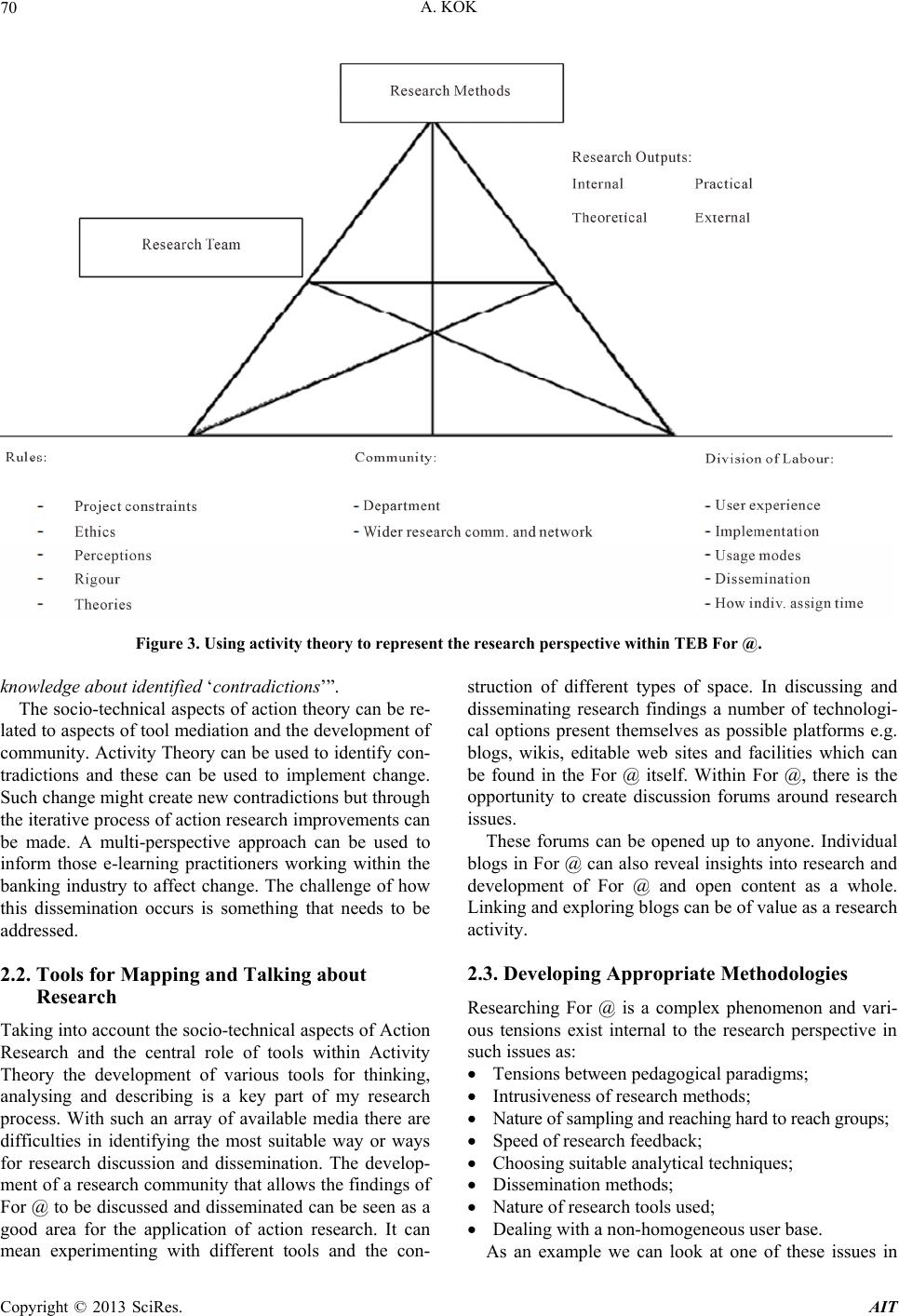

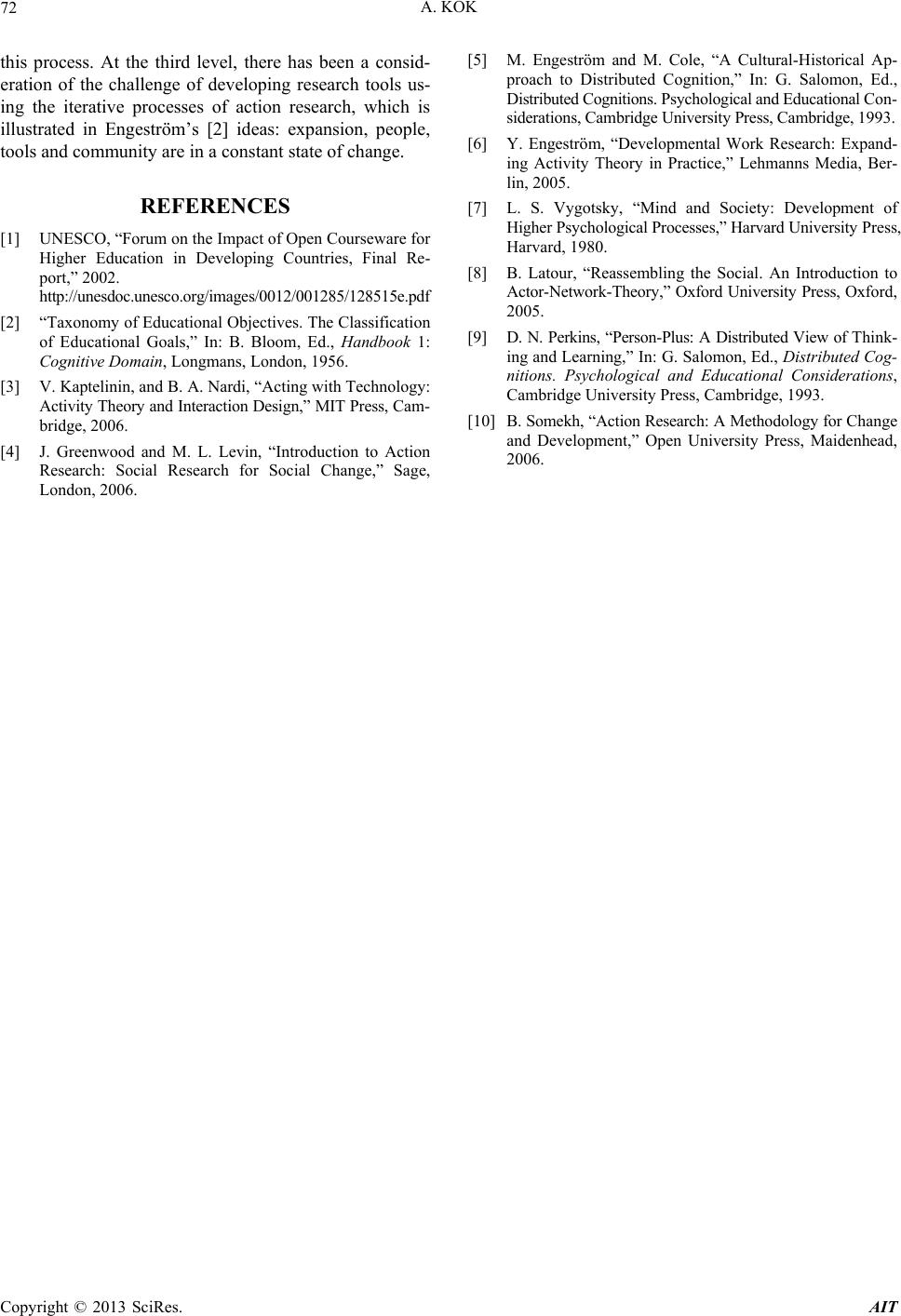

Advances in Internet of Things, 2013, 3, 66-72 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ait.2013.34009 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ait) Behind the Scenes with a Video Training Platform: The Challenges of Researching the Provision of Open Educational Resources Ayse Kok Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey Email: ayshe.kok@gmail.com Received June 5, 2013; revised July 22, 2013; accepted August 3, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ayse Kok. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which per- mits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Video training platforms are now being implemented on a large scale in organizations. In this paper, I look at a video training platform including open educational resources available for many employees with varying patterns and motiva- tions for use. This has provided me with a research challenge to find methods that help other practitioners in the field understand and explain such initiativ es. I describe ways to model the research and identif y where pressures and contra- dictions can be found, drawing on a reflective view of my own practice in performing the research. Open educational resources are defined as technology-enabled educational resources that are openly available for consultation, use and adaptation by users for non-commercial purposes [1]. The bank subject to this case study has been the first organisation in Turkey that provided open educational resources for all its employees. The video platform (called “For @ Tube”) provides users with over 100 video lectures drawn from reputable universities around the world including Yale and Harvard. Other learning tools such as discussion forums, blogs and traditional e-learning courses have been made avail- able to the users on th e e-learning platform called “For @” since 2006. In this paper, I ai m to introduce th e new video training platform (“For @ Tube”) and outline some of the main research issues surrounding such an initiative. I seek to explore theoretical and practical approaches that can provide suitable tools for analysis. Activity theory is seen as a suitable approach for macroanalysis and its use is illustrated in terms of the complexity of large scale research. Activity theory, besides informing research perspectives, can be turned in upon the research process itself, allowing us to con- sider the challenges and context of the research. By using activity theory in this way and illustrating from a range of practical approaches, I demonstrate and illustrate a useful research approach. Keywords: E-Learn ing; Open Content; Video; Action Research ; Activity Theory 1. Introduction Open educational resources are defined as technology- enabled educational resources that are openly available for consultation, use and adaptation by users for non- commercial purposes (UNESCO, 2002). The in ternet has recently seen an increase in such initiatives, including areas such as MIT Open Course Ware, CORE (China Open Resource for Education), Wikipedia, Open Learn and Open Course Ware Universia. Key features of many of such in itiatives includ e the prov ision of course co ntent, the ability to adapt, use and develop content, the avail- ability of social learning tools, and the introduction of other learning tools. The range of initiatives is illus- trated by the membership of the Open Cour se Ware Con- sortium (http://www.ocwconsortium.org) which has mem- bers from a diverse number of countries. The impact of these resources and changes in the ability of individual users to access such educational materials is likely to impact significantly on how people learn. The confine- ment of knowledge to educational institutes is likely to be challenged. Alternatively, new power structures may arise as a result of “big players” dominating the open resource markets. The question arises as to how these open resources will impact on the learning of employees or groups of employees. Will these resources empower learners and how will learners’ experience change? Cou- pled with the advent of open resources, there is also a development of new software and hardware tools such as software that supports social learning and mobile com- puting that may change the possible affordances of such technologies. C opyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT  A. KOK 67 For @ Tube (Figure 1) is a video training platform provided by a Turkish banking institution and it entails open educational resources. The project was officially launched on 20 August 2012. Currently it provides over 200 video lectures for personal study. The material used in this platform is mostly derived from global universi- ties’ course materials. In addition, training videos from local providers and the global bank’s (with whom the Turkish bank has established a joint venture) videos are also utilized. The conversion of all of these materials into an appropriate provision for For @ was conducted using an “integrity” model where the content is kept as close as possible to the original source material with adjustments made relating to presentation on the web, rights issues, and reshaping for a wider audience. The entrance point for the video training platform is a website for employees called “For @”. The e-platform “For @” which is a web-based application developed by a third company is divided into 2 sections (F igure 1): E-learning portal: The e-learning portal called For @ includes over 350 asynchronous web-based courses, an online library and a social learning platform which pro- vides digital collaboration tools such as blogs, forums and an internal social networking platform. This built-in social environment enables participants to share informa- tion about the training they have taken online or offline and communicate with colleagues at other branches. The digital learning catalog (including videos) consists of four types of training: 1) Mandatory courses: These can be in the form of ex- isting catalog courses or courses specifically developed for the bank based on the managers’ needs (courses about product/process/service). 2) Regulatory mandatory courses: These are courses that need to be taken by every bank personnel due to the compliance issues within the Turkish banking industry (e.g.: information securıty, operational risk). 3) Elective courses: These are courses which can be selected from the existing course catalog based on one’s specific interest. Figure 1. General appearance of the online learning plat- form used in the bank. 4) Personal development: These are catalog courses that aim to improve one’s soft skills through his/her pro- fessional life. Some of these courses can also be accessed from the online performance management tool based on the specific targeted skills of the employees. It is also a high level management mandate to conduct frequent online exams via the LMS in order to enhance the branch personnels’ information about the bank’s products and sevices. From time to time, online knowl- edge competition s are also held within the bank based on the departmental requests. Video Portal: This section includes video-based les- sons in the categories of finance, professional develop- ment, bank-specific areas and personal development. Videos that are produced internally or announcements of higher level management are also included in this sec- tion. The platform has also searching capabilities, tutorials, and a technical and content help desk, is targeted at nearly 9200 users of the bank. The platform is planned to be made compatible with the mobile phones (any smart- phone apart from Blackberry can display the online courses.). 2. Video Training Platform—The Research Challenge For @ Tube (Figure 2) is a large project with a dedicated e-learning team including also individuals involved with research and evaluation. Besides this dedicated research team others within the project have research interests including academics responsible for the transformation and development of content. The project as a whole is viewed in terms of an action research model where the results and impacts of research are fed back into project development. Within th is paradigm there is also the chal- lenge and the tension between academic research requir- ing high degrees of rigour and having underlying theo- retical aims and that of applied research with the re- quirement of fast-feedback and relating more to the suc- cess of the site via such issues as marketing, usability studies, site design etc. Researching such a large project involves examining several different areas, each of which presents its own set of challenges. The four main strands of research include; training with For @, the users’ experience, project de- velopment, and sustainability. To this, we can add a meta-layer; the challenge of researching open content. This paper is chiefly concerned with this objective and aims to illustrate our own problems and dilemmas in conducting such research and by offering our insights into models of research provide a guide for others in re- search techniques. An idealised approach to the research has been to: 1 ) Identify and develop theoretical frameworks for Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT  A. KOK Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT 68 Figure 2. General appearance of the video training platform used in the bank. analysis at macro and micro levels; 2) Find tools and ways of mapping and talking about our research; 3) Develop and find appropriate methodologies to en- able us to collect and process research findings. This list may seem very logical and structured as pre- sented here but the evolution of the framework, as we learn within an action research paradigm is more hap- hazard and iterative in nature. A research technique is seen not as something developed in advance but rather as something in the process of development with continual trials, implementations and reworking. For @ itself is a continually evolving construct and this presents an addi- tional challenge to research. The three approaches listed above will be described in more detail with specific ref- erence to research within the project and also to re- searching users’ experience. 2.1. Developing Theoretical Frameworks of Analysis at the Macro- and Micro-Levels 2.1.1. Acti on Research One possible criticism of academic research is that the impacts of such research often have little effect on or- ganisational practice. A possible reason for this may be the divide that exists between the world of academia and the world of work. The process of academic research can be very slow with the major outputs often consisting of writings in journals for an academic audience. Research is often conducted from “afar” that is, it is separate from the object of research. An advantage of this is that re- search is more likely to be independent if not connected to the object of the research. This independence and ob- jectivity is unlikely to be untainted in that research and researchers are embedded within research paradigms, personal social-cultural influences, and the influence of the grant holders who partially or wholly shape the re- search questions. The principles of action research call for a research process that involves change within that which is researched [2]. In a sense it is more of an ex- perimental “trial and error” process in that it is iterative, ongoing and affects change in practice. It can therefore be seen as a process of reflection and practice, often re- ferred to as praxis. In order to affect action research it is necessary to 1) Involve more of the organisation than simply the ded icated rese archers, 2) To integrate the results of the research into decision making at managerial levels. Dangers exist however when moving towards a culture of “self-development” where Action Research is seen as an efficiency tool as opposed to its more idealised aims of development and empowerment of workers [3]. There are also dangers when research is taken out of the hands of research savvy practitioners and placed in those of research novices. Hence, there may be many models of action research adopted according to one’s perspective. Another key issue of action research is the “social-tech- nical” view which sees the successful development of any organisation being an integration of the right social and developmental environment with the use of appro-  A. KOK 69 priate tools. For example, the use of tools for doing re- search and for enhancing interpersonal communication within the research community and others in the organi- sation is part of praxis resulting from the research itself. Action research can provide us with a framework of re- search at the level of For @ as an organisation but also as a framework of reflection and practice. In this case we see this as a way of developing ourselves as individuals and as a team allowing an exploration of ways of work- ing and knowing. It has been mentioned [4]: “The self of the researcher can best be understood as intermeshed with others through webs of interpersonal and professional relationships that co-construct the re- searcher’s identity.” In this sense action research is abou t both personal and professional development. 2.1.2. Activit y Theory as a Way of Modelling Macro-Behaviour For @ Tube represents one of the largest open education interventions in the financial sector in Turkey and as such the opportunity exists to understand how this oper- ates and develops at a macro level. Possible contenders for analysis include activity theory and actor network theory which allow potential ways of understan di n g macro-behaviour. Actor Network Theory (ANT) focuses on identifying the various actors in a social organizations and examin- ing the relationship between these actors [5]. Activity theory focuses on action as it is mediated by tools within a socio-cultural context [5]. It was used as an analytical framework in this instance because of its educational applications including learning in organisations and that ANT was felt to be less clearly structured as an analytical tool. The foundation for Activity Theory comes from the Vygotskian view that all action is mediated by tools whether these be external or internal, concrete or psy- chological [6]. This has been developed into concepts such as “person plus” and cognition as a distributed ac- tivity located within a social group and th e tools that they use (Perkins, 1993). Leont’ev, a prodigy of Vygotsky, explored the way in which this could be applied through emphasising the activity as the main unit of analysis (Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2006). Engeström extended the framework and the subject- tools-object model to take into account aspects of the context within which such action was taken [6,7]. He represented the interrelationships between these contex- tual elements within a triangular structure each node rep- resenting some aspect of interaction. The additional con- textual nodes that he added were “rules”, “community” and “division of labour” [8,9]. This framework was adopted as a practical tool of analysis since it could be applied to view For @ from any number of different perspectives. These different perspectives could then be contrasted, reflected upon, or pushed against each other to force the identification of characteristics within each perspective and various “contradictions” that existed between such perspectives. Figure 3 demonstrates the use activity theory as a way of viewing the research aspects of For @. Researching such a complex and large training initiative provides many opportunities and areas for potential study and of- ten these are driven by project aims. These aims can be envisaged as being part of the rules in which the research is located and represent rules embedded in project design. Other rules are external to the project and include guide- lines for general social research. These deal with issues such as research ethics which can sometimes create ten- sions in terms of the need for fast feedback and the drives for “interesting stories” that may come from other parts of the project such as marketing, or management. “Rule s” may also relate to perceptions of individuals within the team (i.e. not formally held or shared rules) and relate to theoretical perceptions and opinions on the nature of good educational practice. Much research demands a certain standard of rigour (lower risk of error) which might create contradictions with the need for quick feed- back (higher risk of error) to help move the implementa- tion process forward. This contradiction highlights a general problem of the slowness of academic research to reach and inform its intended audience. By identifying and recognising this contradiction ways can be investi- gated for disseminating research internally in order to quickly feedback into the implementation and adaptation processes. When examining Figure 3 contradictions maybe ana- lysed within the structure itself e.g. between the research interests, motivations, and perceived views of the team players, between individuals and rules, about the essence and nature of research itself, about the choice of methods to monitor the learning effectiveness of TEB For @. Con- tradictions can also be viewed of as occurring across dif- ferent perspectives. For example, a contradiction may exist between the need for neutrality and a critical ap- proach of the researchers within the research perspective and the need for promotion and publicity within a mar- keting perspective that is directed towards gaining the attention of us ers . 2.1.3. Activit y T h eo ry and Ac tion Research It is clear that Action Research and Activity Theory can be used effectively together. As Somekh (2006) says when talking about Action Research, “…activity theory is particularly helpful because it gives priority to col- aborative decision making on the basis of sharing l Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT  A. KOK Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT 70 Figure 3. Using activity theory to represent the research perspective within TEB For @. knowledge abou t identified ‘contradictions’”. The socio-technical aspects of action theory can be re- lated to aspects of tool mediation and the development of community. Activity Theory can be used to iden tify con- tradictions and these can be used to implement change. Such chang e might create new contr adiction s but through the iterative process of action research improvements can be made. A multi-perspective approach can be used to inform those e-learning practitioners working within the banking industry to affect change. The challenge of how this dissemination occurs is something that needs to be addressed. 2.2. Tools for Mapping and Talking about Research Taking into account th e socio-technical aspects of Action Research and the central role of tools within Activity Theory the development of various tools for thinking, analysing and describing is a key part of my research process. With such an array of available media there are difficulties in identifying the most suitable way or ways for research discussion and dissemination. The develop- ment of a research community that allows the findings of For @ to be discussed and disseminated can be seen as a good area for the application of action research. It can mean experimenting with different tools and the con- struction of different types of space. In discussing and disseminating research findings a number of technologi- cal options present themselves as possible platforms e.g. blogs, wikis, editable web sites and facilities which can be found in the For @ itself. Within For @, there is the opportunity to create discussion forums around research issues. These forums can be opened up to anyone. Individual blogs in For @ can also reveal insights into research and development of For @ and open content as a whole. Linking and exploring blogs can be of value as a research activity. 2.3. Developing Appropriate Methodologies Researching For @ is a complex phenomenon and vari- ous tensions exist internal to the research perspective in such issues as: Tensions between pedagogical paradigms; Intrusiveness of research methods; Nature of sampling and reaching hard to reach groups; Speed of research feedback; Choosing suitable analytical techniques; Dissemination methods; Nature of research tools used; Dealing with a non-homogeneous user base. As an example we can look at one of these issues in  A. KOK 71 more depth. One of these is the fact the user base appears to be very heterogeneous and heavily skewed in terms of time spent on the site toward the low user. This pyrami- dal structure in terms of the time spent visiting a site is probably a common occurrence in many web sites al- though comparative studies are difficult because open content sites may differ greatly in form and function. Every website is in a sense competing against a large number of other sites in terms of grabbing a person’s attention and part of the decision that people make in spending time on a site is their initial perception of the site’s value. This can very much depend on how the home page of the site is presented and whether the site gives a clear indication of what kind of content or activ- ity that it might contain. A major challenge is to find out about the user experi- ence. Questions relating to this challenge include: 1) How does the use of For @ fit into the wider con- text of the user’s formal and informal learning context? 2) Are users learning from For @? If so how are they learning? 3) Are users engaging and using the tools? If so what are they using the tools for? Distinctions will exist in terms of types of users. Learners may primarily study or use content but others may engage with social learning or using For @ tools. Part of the challenge is to identify the types of user. One possible means of tracing the user’s experience is by us- ing website logs. Generally one can infer whether a user was browsing, skimming, downloading or printing con- tent, or systematically studying or reading parts of a unit. This however does not tell us about what the user is learning and with For @ it is not possible to use pre- and post-study tests since learners will often not be studying a unit as a whole. In this instance, thinking of the units as courses is inappropriate since th is implies a journey fro m a starting point to an end point, and an externally struc- tured pathway through th e material often with some form of assessment. Identifying learning therefore depends on the unique experiences of users and needs to be process orientated. In order to get at the experience of users and the process of learning qualitative studies can provide a rich picture and thick description of users’ experience. There are also several technological tools that can help the researcher in this process although there is always the problem of the degree of intrusiveness in any research exercise. One method of examining whether learning is taking place is by in situ observation and making inferences from user activity. Getting users to think aloud and to record their thoughts can help in this although there are disadvantages to this technique. Another is by using in- terviews where a user’s learning experience can be ex- amined. Simple questions such as “What have you learned?” or “What have you found out that you didn’t know before?” can act as the basis for more probing questions perhaps relating to a range of skills within Bloom’s taxonomy [3]. A problem of such interviews is that they can become an additional form of training in that by causing the participant to recall or reconstruct their experience one is actually changing and r eshap ing it. Thus the research is adding to the learning experience. Remote monitoring can allow a clearer insight into the actual live experience of the learner. 3. Discussion For @ represents one of the largest developments within the open content community in the corporate settings in Turkey and presents a challenge for research. This chal- lenge exists within four strands: teaching with For @, the users’ experience, project development, and sustainabi- lity. In this paper, I have indicated and discussed the use of action research and activity theory as tools to enable us to think and understand the dynamics of a large educa- tional initiative. Action research can potentially allow reflection, action and change within such a project. Ac- tivity Theory represents a tool for recognising areas for action and change and communicating issues to the pro- ject team. It also allows us as researchers to inwardly analyse our own behaviour and help in our personal and professional development. As researchers, there is a need to disseminate inter- nally and externally the research findings to inform- change. The development of communication tools and the novel use of technology to do this are considered an evolutionary process, experiment and change by trial and error. Providing useful research networks and integrating with others are important in the social construction of knowledge and understanding about open educational resources. How to use tools such as For @ Tube effec- tively is a challenge and an important part of my own iterative process of development within an action re- search framework. Reflecting on my own research prac- tice can be considered a meta-research process. Some of the research challenges of finding out about users’ experience have been illustrated. Possible techno- logical tools that can help in this process have been dis- cussed. A consideration of the use of tools as appropri- ated by individuals is a characteristic of the socio-tech- nical view of action research. I have considered re- searching For @ Tube in terms of a number of different perspectives and themes. A three level approach has been presented. At one level, For @ Tube can be viewed using activity theory to shape various perspectives and then examine intra-nodal and extra-nodal contradictions be- tween the perspectives. At the level of the community of researchers, there has been a consideration of the sharing and dissemination of knowledge and the tools can aid Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT  A. KOK Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AIT 72 this process. At the third level, there has been a consid- eration of the challenge of developing research tools us- ing the iterative processes of action research, which is illustrated in Engeström’s [2] ideas: expansion, people, tools and community are in a constant state of change. REFERENCES [1] UNESCO, “Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries, Final Re- port,” 2002. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001285/128515e.pdf [2] “Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals,” In: B. Bloom, Ed., Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain, Longmans, London, 1956. [3] V. Kaptelinin, and B. A. Nardi, “Acting with Technology: Activity Theory and Interaction Design, ” MIT Press, C a m- bridge, 2006. [4] J. Greenwood and M. L. Levin, “Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change,” Sage, London, 2006. [5] M. Engeström and M. Cole, “A Cultural-Historical Ap- proach to Distributed Cognition,” In: G. Salomon, Ed., Distributed Cognitions. Psychological and Educational Con- sid e r a t i o ns, C a m b r i d g e U n i v er sity Pre s s , C a m b r i d g e , 1993. [6] Y. Engeström, “Developmental Work Research: Expand- ing Activity Theory in Practice,” Lehmanns Media, Ber- lin, 2005. [7] L. S. Vygotsky, “Mind and Society: Development of Higher Psychological Pr ocesses,” Harvard University P ress, Harvard, 1980. [8] B. Latour, “Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network- Theory,” Oxford University Pre ss, Oxford , 2005. [9] D. N. Perkins, “Person-Plus: A Distributed View of Thin k- ing and Learning,” In: G. Salomon, Ed., Distributed Cog- nitions. Psychological and Educational Considerations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993. [10] B. Somekh, “Action Research: A Methodology for C ha n ge and Development,” Open University Press, Maidenhead, 2006. |