Current Urban Studies 2013. Vol.1, No.3, 59-73 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/cus) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/cus.2013.13007 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 59 Morrow Tomorrow: Exploring the Pedagogical Experience of a Planning Studio Involving Students with Mixed Skills Mahyar Are fi , D avid J. Edelma n University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA Email: mahyararefi@g mail.co m Received July 4th, 2013; revised August 12th, 2013; accepted August 26th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Mahyar Arefi, David J. Edelman. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the origina l w o rk is properly cited. This article explores the pedagogical experience of a group of graduate planning students with diverse undergraduate backgrounds in a degree capstone studio. The studio concentrates on the “shrinking” vil- lage of Morrow, Ohio. Following a brief overview of the shrinking cities literature, the article discusses the specific issues of economic decline facing the Village of Morrow and its population. It then delves into two specific aspects of this pedagogical experience, namely, a two-part SWOT analysis based on the data collected by the students directly and from a community charrette, and three redevelopment scenarios developed following an analysis of the lessons learned from this experience. The discussion and conclu- sion focus on the pros and cons of a planning studio involving students with mixed (design and non-de- sign) skills. Keywords: Planning Pedagogy; Shrinking Cities; Scenario Building; SWOT Analysis; Redevelopment Strategies Introduction This article explores the pedagogical experience of 38 gradu- ate Community Planning students from the University of Cin- cinnati who proposed three redevelopment projects for a “shrin- king” town in Ohio. With the end of the United Parcel Service’s (UPS) tenure in Morrow, the once bustling village has lost eco- nomic opportunities in the areas of transportation and freight shipping, and has experienced population decline and infra- structure disinvestment over the last three decades. To better understand Morrow’s current socio-economic and physical woes, a brief historical account of the village is given, followed by a closer look at data collection and analysis as well as the three recommendations. The pedagogical experience presented in this article stems from the belief in encouraging planning students of two distinct types to work together to not only propose physical designs, but other planning interventions as well. Thus, students with sig- nificant design skills must work collectively with the students who lack these skills but have other important knowledge and abilities. To do this, the two instructors set up a pre-conceived pedagogical framework using Coyle’s (2011) 6 “support sys- tems.” It is important to note that the graduate students who participated in this project had a wide variety of educational backgrounds, including architecture, landscape architecture, engineering, geography, sociology, political science, economics, and finance, which means the students had multiple skill sets and could not just simply be categorized as students with de- sign abilities and those without them. Bringing students to- gether with different training prior to graduate school creates a vibrant learning environment, but also sometimes leads to fric- tion. Taking stock of students’ skills and know-how dictates how to divide the work and distribute responsibilities in the studio. However, there are times when those with design backgrounds feel overwhelmed because those who lack those skills rely on them and have high expectations about their contributions to the project (i.e., scenario building and rendering). High expec- tations can, in turn, inadvertently expose those students to more peer pressure compared to the others, although those with supe- rior organizational and writing skills also feel they have a heavy workload. This is, to some extent, what happened in this studio. Stu- dents with GIS, Auto CAD, Photoshop, design, and map-mak- ing skills assumed leadership in two of the three groups, while those with organizational and writing skills led the third. How- ever, the instructors anticipated this unevenness of skills, and to remedy this discrepancy, the students with design/technical skills were distributed equally to all scenario-building groups. The discrepancy in organizational and writing ability, unfortu- nately, was not addressed to the same extent. This article delves into these issues in what follows, and ends with some general observations and a discussion of the students’ learning out- comes and the challenges surrounding studios having students with mixed skills. Morrow’s Brief History Morrow became an incorporated village in 1845 when the Little Miami Railroad Company completed its rail line through it. As the railroad became more important to the village and the region, businesses started to grow in and around Morrow, and another rail line, from Cincinnati to Zanesville, was built. Then, “by the 1860’s the village had become a major transfer point  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN between three types of transportation: river, highway, and rail- way” (1979 Village of Morrow Comprehensive Plan). The vil- lage continued to grow until the 1940s, when the decline of the national rail system hit the area. In 1959, one of a series of floods that occurred in just a few years severely damaged Mor row (1979 Village of Mor row Com- prehensive Plan). With the loss of the railroad and the floods, the historic business district of Morrow deteriorated and suf- fered from disinvestment. Then, as the dominant form of na- tional transportation became the interstate highway system, the village’s Main Street became neglected. Nevertheless, the situation is not entirely bleak. Outside the Village of Morrow, the first 20 vines were planted in 1969 that would soon become Valley Vineyards, a winery that exist to this day (www.valleyvineyards.com). In 1984, the railroad passing through Morrow was converted into the Little Miami Scenic Bike Trail. The first 13.5 mile segment that was con- structed started in Loveland and ended in Morrow. This bike trail is now the longest trail in Ohio and, as Figure 1 shows, extends 62 miles from Cincinnati past Dayton (OKI, 1999). Both Valley Vineyards and the Little Miami Scenic Bike Trail have helped to bring visitors to Morrow. Morrow is in the Little Miami School District, and by 2009 a new high school, intermediate school, and junior high school were built right outside of the village (Figure 2). Nathaniel Development also bought 156 acres to build high-end homes within Morrow, but this new development, the Woodlands at Morrow, has had only a small portion of its lots filled so far. Figure 1. Little Miami Scenic Bike Trail; Source: www.traillink.com. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 60  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN Figure 2. Location Map of Morrow, OH; Source: www.googlemaps.com. An Overview of the Shrinking Cities Literature The “shrinking cities syndrome” (Adhya, 2013; Bowns, 2013) is not just an American, but also a global phenomenon, dating back to the post WWII era. Old manufacturing cities such as Detroit, Michigan or Gary, Indiana exemplify the so-called “rust-belt” cities, remnants of a shift from industrial to post- industrial development strategies in the US as part of global economic restructuring. The rise of China as a new economic giant and the transformation of the US and Japan from Indus- trial to knowledge-based economies represent this shift. Closure of industrial plants, the rise of brown fields in the US, Europe and Japan, disappearing neighborhoods and declining cities epi- tomize such urban transformations. Policies to curb decline also vary widely, ranging from culturally-based initiatives and com- munity design projects, to creative partnerships (locally and re- gionally). Successful cultural policies or initiatives (Mayer and Holzheimer, 2009), typically wind up boosting the local econ- omy by investing in local cultural practices such as “music concerts, dances and festivals, and crafts and cooking” (Bowns, 2013: p. 73). Research has identified some of the factors affect- ing small town shrinkage (i.e., deindustrialization, depopulation, globalization and suburbanization) (Sassen, 1991; Bluestone & Harris, 1982; Bowns, 2013; Adhya, 2013). These studies contend that to curb local decline, local and re- gional collaborations are imperative, and they pay attention to place-based development and community participation theory (Adhya, 2013; Zingale & Riemann, 2013). Such strategies highlight walkability and Main Street revitalization projects as important measures to curb small city decline. Yet, other stud- ies focus on governance, as any successful stabilizing strategy must involve empowerment, capacity building and community participation to ensure sustainable development (Feldhoff, 2013; Hospers, 2013). Problem Statement What was once avibrant small community has declined stea- dily for two decades. More broadly, the endemic economic and physical decline characterizing small town America also hovers over Morrow. Population loss, fewer local businesses and an ever smaller economic base, etc. are symptomatic of “shrinking cities,” and Morrow is no exception to these trends (see Figure 3). Furthermore, Morrow’s 5.2% foreclosure rate (HUD, 2013: February 22), which is higher than Warren County’s 3.9%, cou- pled with its already aging housing stock, calls for immediate attention. While Morrow represents hundreds of other languishing small communities, taking stock of its natural and man-made resources and assets would be the first step in the right direction. Such a direction is first rooted in better understanding Mor- row’s physical and economic woes, which in turn, provides a Morrow Villlage T otal Population (1970-2010) 1300 1280 1260 1240 1220 1200 1180 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Figure 3. Morrow’s population loss over time. Source: Social Explor er and Census Bureau 2010. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN basis for crafting a planning strategy for a sustainable vibrant future for its residents. What follows represents an inroad into the key problematic issues associated with Morrow’s steady de- cline, and exploring three specific projects which conceivably assist the village to regain some of its lost vitality over time. The projects conjured up in this study reflect the students’ ob- servations based on their interaction with the community and Morrow’s local officials. Research Method As part of an effort to reverse its economic and physical de- cline, the Village of Morrow commissioned a graduate capstone studio at the University of Cincinnati’s School of Planning in the spring semester of 2013. To this end, the studio explored three specific development strategies in two phases: Phase I: Data Collection and SWOT Analysis; Phase II: Redevelopment Recommendations Any planning strategy for Morrow requires an understanding of the potentials and limitations of its supporting systems: tran- sportation, energy, natural environment, water and solid waste management, and economic and physical conditions. Sustain- able communities have vibrant support systems for their daily functions. Without an efficient, multi-modal transportation sys- tem, a healthy natural environment, a vital economy and so forth, planning for sustainable communities would more than likely fail. The first step in the right direction, therefore, can be taken only when and if these support systems are identified and capitalized upon. During Phase I, the students were divided into six groups, each of which was responsible for collecting information on one of the above-mentioned supporting systems. The students collected information from various sources in local and county government. In addition to utilizing secondary sources, the groups each visited the village several times for fieldwork. The key part of Phase I consisted of a two-part SWOT analysis. SWOT stands for a systematic understanding of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. A well-attended public gathering, or charrette, hosted by the Village of Morrow made it possible for the students to interact with the community. The main purpose of this gathering was for the students to come into close contact with residents and see firsthand what they thought about the potentials and challenges facing their own community. Particular emphasis was placed on questions re- garding the six support systems, which provided the students with invaluable information for the next phase of the work. Phase 1: The SWOT Analysis Prior to the charrette, the class identified what it considered to be Morrow’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This gave the students a better understanding of its dynamics prior to checking them against the community’s perceptions of its problems/potentials. In other words, this stage was done in two parts. In the first part, the students relied solely on their group observations of Morrow’s problems and prospects, and the second part, (the reality check), involved getting input from the community directly. Prior to the community charrette, the students (see Table 1) found the following to be Morrow’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats: The latter part consisting of the data collected during the community charrette (see Table 2), along with the students’ own observations formed the basis for scenario building and re- commendations. About 30 individuals who represented a cross-section of the community gathered in the local high school auditorium to free- ly express what they thought were Morrow’s strengths, weak- nesses, opportunities and threats. They wrote their ideas on Post: It notes and placed them under labels for each of the four cate- gories. These notes were grouped, and members of the commu- nity were given the chance to rank these answers based on which ideas needed the most at tention. There was a 4-tier rank- ing system using different colored sticker dots; blue stickers indicated the highest priority, and then yellow, green and red. Red was a source of confusion for some members of the com- munity because while it was meant to indicate ideas of least priority, some thought it meant that these items were not an issue. After the dots were put on the items, the SWOT done by the class was compared to, and combined with, the community SWOT. This combined SWOT is what is discussed next. Table 1. SWOT analysis based on t he st ud en ts’ observations. Source: Compiled by the authors. Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats Natural Envir onment Beauty Mineral resources Fresh water Agriculture Exported produce No local revenue Mines & Wildlif e Gravel mines Wildlife Slope Flooding Topography Scenic views Valleys Location 100 year floodplain PUD 40% of Morrow Village green space Vacant Buildings Aging buildings Woodlands 1/2 Village area Tree variety Auto-Dependency Weakened walkability Tourism Bird watching Hiking Biking I - 71 Freeway Redirect l ocal traffic to I - 7 1 Green Space Preserve green Main Street Water Bodies Little Miami River Todd’s Fork Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN Table 2. SWOT analysis based o n t h e c ommunity Charrette. Source: Compiled by authors. Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats Development potential Drug abuse Tax incentives Flooding Farmers’ M arket No arts Housing subsidies Fear of change Natural envir o nment No grocery s tore Main Stree t redevelopment. No business diversity River No public trans portation School redeve lopment Apathy Bike trail Vacant stores Village rebra n d ing Neighboring government relatio n s Winery Aging building structures Parks Schools Quality water supply No connect ion between river and Main St. Community events Aging community Tourism & history No sense of community River recreation Aging infrastructure Available land at low cost Limited ho us ing option s Technology (Fiber optics) Community image Security & walkability Limited t ax revenue Key: High priority; Medium priority; Low priority; No priority. Strengths Natural environment, tourism, topography, affordable land value, a walkable Main Street and the bike trail were identified as Morrow’s strong points. The existance of clean water, a walking path along the center and both sides of Main Street, as well as a designated bike path, all are positive aspects that Morrow can rebrand towards its redevelopment. With its close proximity to Cincinnati, Columbus, and Cleveland, on the one hand, and its significance as an historical district, on the other, Morrow’s location was identified as a strength. Weaknesses The lack of robust businesses (especially on Main Street) was identified as a weakness. The age of the buildings and va- cancy of certain structures were also identified as areas that need to be improved. The lack of a sense of community and togetherness is also something that was identified in a variety of ways. The poor usage of Main Street was identified as a weak- ness as well. Improving signage and attracting a wider variety of ages were further identified as areas that need improvement, as were housing options for the elderly and a wider demogra- phic in Morrow. Moreover, the absence of a grocery store was widely considered a weakness. Opportunities Businesses were identified as Morrow’s growth engine. Spe- cifically, the community considers a grocery store, restaurants and the Main Street redevelopment as the untapped opportuni- ties critical to its revival. The participants also acknowledged improvement of the existing schools and rebranding the village as promising venues for enhancing Morrow’s image. In addi- tion, Morrow has potential to increase energy efficiency and adopt more sustainable development practices. Interesting top- ics not addressed include alternative energy and water supply sources, the Planned Unit Development (PUD), the gravel mine and future annexations. Threats Aging infrastructure, susceptibility to flooding, a languishing economy, a prevailing sense of apathy and a poor community image were identified as high priority areas in need of planning. More to the point, the aging sewer system needs improvement; part of the natural environment and agricultural land are located in the floodplain, and areas of land fill need protection. The sense of apathy towards change, conducting business as usual, and the declining sense of community were reoccuring themes during the SWOT charrette. Surprisingly, promoting sustain- able development strategies was not a major concern. Phase 2: Three Recommendations To ensure cohesion, consistency, and continuity from Phase I, the students considered in Phase II the applicability of the SWOT analysis surrounding the six supporting systems they had examined earlier. This approach helped them to be more sensitive to recommendations grounded in group observations and community input. Based on the SWOT analysis carried out in Phase I, and through fieldwork, three main location-specific redevelopment themes emerged in Phase II. These were: rede- velopment (The Main Street), re-inhabitation (The Plaza), and re-greening (The PUD). These three themes emerged in re- sponse to the issues observed during the students- and commu- nity-driven SWOTs. Broadly speaking, the three projects re- flected three separate responses to Morrow’s pressing issues: The Main Street represented Morrow’s shrinking economy, loss Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN of employment opportunities and Morrow’s traditional physical and social anchor (redevelopment). Yet, preserving the existing stock of green space and different roles it plays in integrating natural beauty and the imperatives of sustainability emerged as a second recurrent theme (re-greening). Finally, adaptive reuse of existing structures (i.e., the school or the plaza building) seemed a recurrent theme, which attracted much attention (re- inhabitation). The redevelopment theme ranged from the replacement of dilapidated buildings to reducing auto-dependency by creating compact, walkable public spaces. The re-inhabitation theme concentrated on taking advantage of existing structures, which could be recycled back to the community by creating vibrant places through adaptive reuse. Finally, re-greening represented viable measures for creating new parks, as well as preserving or reconstructing wetlands, and existing green spaces (see Figure 4). The vitality of Main Street in Morrow is a key issue with much promise for the vitality of the entire village. For many people, this street symbolizes its collective identity. The stores along it create a critical mass for a tightly knit, walkable busi- ness district. However, many of these businesses are struggling to make ends meet, or have become vacant over time. Their steady decline over two decades is a reminder of Kelling and Wilson’s famous (1982) “broken-windows syndrome,” which notes that vacant, languishing businesses are akin to a chain reaction or to a vicious cycle of further suffering and decline. This theory implies that situations like this can only make mat- ters worse, and that once businesses are trapped in a cycle of decline, further decline spreads. One of the three groups of students, therefore, looked at redeveloping Main Street in Phase II. The second project area was a strip mall known as “The Plaza.” This is a rather large, decaying building symptomatic of many towns across the country. The second group of students focused on the retrofit or partial adaptive reuse of this structure, that is, on re-inhabiting it. In many shrinking cities over the last few decades, the adaptive reuse or redevelopment of existing building stock has gained popularity as an effective strategy for sustainable development. These students focused their efforts on redeveloping the Plaza as a new Innovation Center, a think- tank for engaging in state-of-the art technological solutions to future problems. The PUD or the planned unit development emerged from the SWOT analysis as the third allocated project area. This rather large, partially developed piece of land, centrally located not far from Main Street, is one of the key areas of the village with significant vegetation cover, and contains new, large-lot hous- ing stock. However, for many reasons, the entire PUD is not yet developed, although zoned for it. The third group of students made efforts to come up with an alternative development strat- egy for re-greening this site, i.e., preserving a significant part of it as a green field. Theme 1: Redevelopment Addressing the disconnection between Morrow’s central business district, the surrounding residential areas, and the Lit- tle Miami Scenic Bike Trail, which has great potential to attract people to the village, emerged as a design priority (see Figure 5). Currently, cyclists and pedestrians have no reason to spend time on Main Street. Instead, through-traffic regularly bypasses Figure 4. The locations of 3 redev e l opment projects; Source: www.googlemaps.com. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN (a) (b) Figure 5. Theme 1: Main street redevelopment plan. Source: Proposed by students. (a) Before; (b) After. the lackluster business district. To remedy this, the students re- commend an Adventure Recreation Area with economic and recreational appeal to both tourists and Morrow’s residents. This proposed facility connects Main Street and West Pike Street commercial developments with the pedestrian and bicy- cle-friendly environment of the trail. Due to the parcel mix, a three-phased development plan is suggested to accommodate financial and legal feasibility. This development includes the following elements: a BMX course, an indoor climbing center and a high-rope course. The Adventure Recreation Area will be well-publicized throughout the entire development process to drive interest and excitement for the development. Therefore, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN significant community input is necessary to coordinate devel- opment phases, prioritize projects and market opportunities. While the Adventure Recreation Area provides an opportu- nity to develop a completely unique use for Main Street, special attention to detail must be given to shielding existing residential and commercial developments from the negative externalities associated with this type of project (i.e., dust, loitering, conges- tion, noise and bright lighting). Coordination and open commu- nication between village planning committee members, Village of Morrow administrators and the public is, t herefore, necessary for the success of the development. To best mitigate negative externalities, a phased development plan will enable an ongoing assessment of development progress. A successful example of exemplary coordination among stakeholders is the Cleveland Velodrome project in Cleveland, Ohio. The project development process employed here incur- porates significant stakeholder collaboration and organization. A 501(c) 3 nonprofit was formed in 2007 by a committed group of stakeholders. Fast Track Cycling, Inc. consists of a 12-mem- ber volunteer Board of Trustees with legal, financial, political, non-profit, track cycling, fund raising and construction respon- sibilities (Clevel & Velodrome, 2013). Various teams of stakeholders took the visionary idea of in- corporating an Olympic-grade velodrome into Cleveland’s Broadway/Slavic Village neighborhood. Ultimately, a nearly 9- acre site in the neighborhood was selected to house the velo- drome. Due to considerable project costs (an initial $8 million total), the velodrome was phased in as an outdoor track that was constructed and opened in August of 2012. Currently, Fast Track Cycling, Inc. is working on the subsequent two phases of project development, which include a turf recreation field and a connected air-dome insulating the velodrome and recreation field, with additional amenities to service track visitors. An an- ticipated 500,000 annual visitors to the Cleveland Velodrome project will revitalize the neighborhood and generate significant economic impact for the City of Cleveland. This model of vol- unteer stakeholder participation and coordination is, therefore, an ideal model for envisioning an Adventure Recreation Area in the Village of Morrow (Clevel & Velodrome, 2013). With respect to the supporting systems of Phase I, the con- cept addresses the existing vacancies along Main Street and serves as a catalyst for a more inviting and viable central busi- ness district. Additionally, maintaining the small-town charac- ter of Morrow by proposing better-enforced property mainte- nance and encouraging development that works with the area aesthetics are key considerations drawn from the initial physical analysis. As for transportation, this scheme ensures better con- nectivity, walkability and well-planned parking along Main Street. Balancing vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic is crucial to the vitality of Morrow’s Central Business District, and this proposal encourages positive measures towards creat- ing this balance. Maintaining the integrity of the natural environment is an- other critical factor in the Main Street redevelopment plan. The Central Business District has a number of green spaces sprin- kled between Main and West Pike Streets. Better development, maintenance and amenities for these spaces prevent possible erosion and/or flooding due to Morrow’s proximity to the Little Miami River. Furthermore, the introduction of native trees to line the streets l helps create a healthier downtown. As for en- ergy, a desire for greener development and reduced travel time to work emerged during Phase I, and this proposal enhances green-building practices, increases density and develops retail stores that can create a substantial economic impact and job creation. Economic development is a key element of Morrow’s Main Street project. Leveraging Morrow’s unique assets, developing a genuine branding strategy, and creating viable businesses fo rm the basis of this redevelopment strategy. Additionally, input from Morrow residents indicated that economic development was a top priority, and this proposal provides implementable guidelines to spur redevelopment in Morrow’s Central Business District. Finally, water and sanitation priorities are considered in this proposal, with the stress placed on creating “dual-pur- pose” landscapes. These suggestions emphasize creating better- manicured landscapes that are aesthetically pleasing and help cycle water through the land. Additionally, the sustainable de- velopment recommendations further suggest the introduction of branded waste receptacles and improved property maintenance to assist with sanitation. Theme 2: Re-inhabitation The second group focused on Morrow’s shopping plaza, built in the 1960s, with its current seven storefronts, three of which are vacant (see Figure 6). Although one store will be occupied within the coming months, the shopping plaza is deteriorating fast. Nevertheless, the plaza’s location and size give it a strate- gic advantage as a re-inhabitation site. In addition to the vacant storefronts, most of the lot is taken up by empty parking spaces, and the surrounding properties do not gain any market value from the plaza. Converting the site into the Morrow Innovation Center connects corporations and institutions in southwest Ohio with state-of-the-art technology. The Innovation Center capitalizes on its proximity to three me- tro areas and the resources offered, as it is at the nexus of Cin- cinnati, Dayton and Columbus, and it could serve as a meeting point for their institutions. Morrow’s fiber-optic capabilities, which emerged during the community charrette (see Table 2), provide some untapped op- portunities for the village as well as the adjacent municipalities. Access to fiber optics allows new businesses to move to Mor- row and grow. Residents and companies are able to communi- cate in cyberspace. The current models for innovation centers across the country use this technology to nurture the relation- ships among corporations, entrepreneurs, universities and local governments, and the 25 to 44 years old “creative class” could be attracted to a new innovation center. While Morrow may not have a critical mass of creative class, but its fiber optics capa- bilities, and its proximity to major cities, can potentially attract young professionals to the innovation center. The Innovation Center proposal recommends replacing the existing buildings with a new structure, which, combined with better landscaping and more appealing street frontage, makes the area physically more attractive. The improved appearance assists in the re-inhabitation of the Village of Morrow by mak- ing it more desirable for new residents and businesses. The development of the nearby park will also attract residents and visitors. The Morrow Innovation Center proposal integrates the site with the existing Little Miami Bike Trail. This integration enhances the connectivity of Morrow’s transportation options. The planned multi-use trail provides a better sense of commu- nity and connection throughout the village. Economically speaking, this proposal should result in creating new jobs, both Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67 (a) (b) Figure 6. Re-inhabitation plan. So urce: Proposed by s t ud e nt s . (a) Before; (b) After. during construction and after the center begins operation. It is expected to help generate secondary employment to support the new technology jobs too. The new employment opportunities would increase the likelihood of success of the Main Street Redevelopment and the PUD redevelopment projects. Higher employment and population will, in turn, increase the tax base of the village. These recommendations reflect the community aspirations expressed during the charrette. As parts of the village lie within the 100-year floodplain, new developments including the Innovation Center’s site must have provisions to avoid or mitigate risks of flooding. These provisions include measure such as minimizing impervious surface, and increasing plant cover. Existing pavements should be used for sidewalks and parking lots to further reduce flood- ing potentials. The proposal for the Innovation Center takes advantage of Morrow’s strengths (i.e., the water bodies in order to integrate the project site, the bike trail, and the Little Miami River) not to mention creating additional green spaces. A pro-  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN posed park restores natural areas and provides a connection between residents and their environment, while the neighbor- hood trail offers opportunities to interact with the natural envi- ronment of the village. As for energy, the proposed plaza redevelopment site re- places the aging, energy inefficient structure with a new, much more efficient one. The proposal recommends seeking LEED certification for the rebuilt structure, ensuring a higher level of energy efficiency than standard development. The structure at the re-inhabited site should use solar heating for hot water, an inexpensive and easily implemented technology. Energy Star rated equipment should be used wherever possible. Overall, this proposal provides an excellent opportunity for energy efficient development as discussed in the energy section of Phase I. Fi- nally, the Innovation Center provides opportunities for tech- nology industry investors and entrepreneurs to take advantage of the high quality water resources the village can provide. Storm water remediation efforts and resource efficient tech- niques described previously help to mitigate the stress placed by the project on aging sewer and water infrastructure, and necessary upgrades should be included in developer proposals. Any need for additional sewer taps should be met by the vil- lage’s existing surplus. Also, additional efforts to improve sus- tainability of the redeveloped site should include the imple- mentation of a recycling program to reduce the production of waste as well as the cost of its disposal. Finally, the suggestions of the solid waste and water group for improved infiltration of rain water into soil should be aided by the reduction of imper- vious surface coverage as described in the natural environment section. The increased infiltration of storm water also helps to protect the area’s aquifers. The key to sustainable re-inhabitation here is to incorporate connectivity with economic development (Dunham & Wil- liamson, 2011). The existing bike path can serve as the con- necting thread between the Innovation Center and the rest of the village. Additionally, the public library provides a source of traffic and adds to the walkability of the village, so its place- ment within the plaza is strategic both now and after the inau- guration of the Innovation Center. Morrow can become a vil- lage that has turned its declining population and stagnant eco- nomy into one that provides its residents with local amenities and jobs, and that attracts talented professionals and thriving businesses. Theme 3: Re-greening The Woodlands at Morrow Planned Unit Development (PUD) exhibits many of the shortcomings of traditional suburban de- sign, including large parcel sizes and sprawled development patterns. Originally designed to have over 900 new homes spread over 156 acres, the lack of pedestrian connections in the PUD encourages a reliance on the automobile and isolates the area from the rest of Morrow (Figure 7). As it stands, the PUD is only partially developed, but the area was chosen as a key re-greening site because of its unique history and beautiful natural setting. The unfinished nature of the original PUD project, however, entices most developers to propose its full development as a green field site. Maintaining the PUD site as the main green focal point for the entire village (based on the pre-charrette SWOT), on the one hand, and the development opportunity it created for increasing the limited housing options and as a Future De velopmen t Develop ed R esi dential Area Fool/C lu b house Future De velopmen t Open Space 0 400 800 Ft Develop e d Resi dential Area Future De velopmen t Open Space Figure 7. The developer’s proposal . Source: Village of Mor row. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN venue for “branding” (based on the charrette SWOT) on the other, attracted the students to propose it as a third project theme. This project, while sending somewhat conflicting mes- sages, showed promise upon further examination. The students sought to strike a balance between its partial development and maintaining the rest of it for recreational and ecological pur- poses. As a recurrent theme during the charrette, Morrow’s lack of housing variety signified a major problem. Single family detached housing, small “granny flats” in backyards, duplexes, row houses, apartment buildings and other housing types pro- vide affordability and increase variety. If designed properly, a higher density neighborhood can yield both greater affordabi- lity and an enhanced sense of community. Retrofitting the PUD through in-fill cluster housing, therefore, increases housing options. The students proposed cluster housing as opposed to con- tinuing the PUD’s initial large lot zoning scheme. Cluster housing promised other advantages including improving water and solid waste management by reducing the existing number of sewer taps. It also preserves open and green space by focus- ing on compact design, which, in addition to preserving more green space, provides a more efficient storm water management system by decreasing the amount of runoff. As a dual-purpose open space, the remainder of the PUD site serves both as a community park and gathering area, which also reduces the likelihood of flooding. In addition to controlling runoff, com- pact cluster housing reduces solid waste by enabling compost- ing and recycling programs. In terms of economic development, the partial development of the PUD creates untapped housing opportunities to supple- ment the existing housing stock in downtown Morrow. The re- greening design could also incorporate hiking and biking trails, kayaking and canoeing opportunities, as well as a golf course, conservatory facilities and/or camp grounds in close proximity to downtown. A new mixed-use component of the PUD plan could create new economic development opportunities by di- versifying the housing and commercial options of the village. All of these design features provide incentives for tourism with- in and outside the PUD site. The major design element that has already been integrated into the PUD’s existing conditions is the pristine natural envi- ronment. The majority of the PUD area is a natural, undevel- oped landscape. The key design feature of the PUD was to pre- serve green space and wildlife, and to increase the area of per- meable surface to manage runoff. Coupling preservation with wildlife conservation, and incorporating hiking trails, also add- ed recreation opportunities with economic development bene- fits. Redesigning and partially densifying the PUD enhances the sense of community and its image (which was recognized as a problem in the charrette). Improved signage and gateways were also identified asways to improve walkability and way finding in the PUD project. Reducing large parcel sizes enhances the close-knit, walkable sense of community, and strengthens ac- cess to public amenities within five to ten minute walk ratios, which would, in turn, enhance social interaction. These pedestrian walking paths can be part of a larger system of mobility: street networks, pedestrian walkways and bike lanes. Creating places where residents and visitors can walk safely leads to more people utilizing Morrow’s amenities and activities. Connecting the Loveland Bike Trail with an expanded bike trail network permits bikers to easily maneuver in and beyond Morrow. Multi-use trails are a great part of a transportation circulation system, as well as a recreational activity. The paths located in the forested area are suitable for both hiking and mountain biking, where as those in the residential areas help pedestrians and bicyclists to commute from one place to an- other. The Loveland Bike Trail is one of the most important assets within Morrow, but, currently, it is not utilized at its highest and best use. Building a bike trail network off of the Loveland Bike Trail that links to other assets throughout Mor- row is a great way to connect visitors to the rest of the village. It will also allow Morrow residents to travel throughout the village safely and access the Loveland Bike Trail and commu- nities along it. Using renewable energy sources can also further enhance the PUD project. Incorporating solar panels into the new residential units helps reduce the carbon footprint and ultimately saves energy. Energy reduction can also be obtained by curtailing automobile dependency through increased accessibility within the PUD and Morrow. LEED design standards are proposed for new homes. Incorporating these standards helps save energy and water, thereby providing an all-round healthy environment. LEED homes maximize fresh air indoors and minimize expo- sure to airborne toxins and pollutants. These buildings have the potential to use 20% to 30% less energy than a home built to code. LEED Neighborhood Development (LEED ND) integrat- es principles of smart growth, urbanism and green buildings. This type of neighborhood design successfully protects and en- hances overall health, the natural environment and the quality of life of a community. The new design incorporates fewer ve- hicle miles traveled and increases access to amenities by foot or bicycle. It also promotes more efficient energy and water use. Key LEED ND items that the PUD can incorporate are: agri- cultural land conservation, bicycle networks, steep slope pro- tection, walkable streets, mixed-income, improved access to civic and public spaces, local food production, tree-lined and shaded streets, solar orienta tion and storm water management. Students proposed three different site plans for the PUD. Each of the three options seeks to unify the natural and physical environments and create better connections within and outside of the PUD. The principles used in each of the three unique de- signs are tailored specifically to complement and build-upon Morrow’s existing infrastructure. These three site plans, there- fore, represent a future for the PUD that will fit directly into the existing urban fabric of the village and enhance Morrow’s fu- ture development. Preserving the existing green space in the form of a nine-hole golf course is the idea behind the first PUD concept (Figure 8). A golf course seemed viable to students because it attracted potential tourists while preventing further development of the PUD as a green field site. In the proposed design, a new road connects two separately developed areas of the PUD and the main roads leading to downtown. The road is split into four sections delineated by traffic circles that slow traffic through the neighborhood yet do not necessitate stop-and-go intersec- tions. Entering through a new neighborhood gateway on the west side of the PUD, travelers are greeted by tree-lined streets before entering the first residential area consisting of single family homes located across from wooded, undeveloped lots. After passing the first traffic circle, two-family lots transition into commercial and mixed-use spaces on both sides of the street. This space consists of a plaza with the golf center, small Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN Community Farm 0 400 800 Ft mercial Center Family Park Single Fami ly Lookout To wer Lookout Tower Town Houses Figure 8. PUD Option 1. Source: Propose d by students. retail shops and an information center serving the nature trails south of the PUD. The final section of this thoroughfare starts at the edge of the commercial area and incorporates large sin- gle-family lots before reaching the final traffic circle and con- nection to Morrow-Blackhawk Road. The trails are unpaved and overlook the natural scenic area supported also by an information center and several dispersed bathroom facilities throughout the site. Transitioning from the nature preserve north through the residential neighborhoods, a small community park on the northwest corner of the PUD pro- vides a play area and terminates at the historic old stone-house brewery building. As one moves farther north, new pedestrian bridges and bike paths connect the PUD to the rest of Morrow and to its regional bike trails. The final design element just north of the PUD across the river is a community farm located in the lower part of the site. This farm provides planting space for growing produce and crops for the village, serving as an opportunity to educate the community on the importance of local food. Finally, the steep slopes in the PUD would be used for storm water management before running downhill to the proposed retention pond. The second PUD option (Figure 9) consists of two housing types: the current single-family homes and two-family units. A gateway leading into the residential area marks the community boundary. A new road following the natural topography con- nects the two distinct residential areas with the forest, providing a place for people to spend their weekends. A conservatory is added at the southern edge of the PUD to act as a gathering place for people visiting the forested area. The conservatory features education programs about the surrounding wildlife and hosts a series of programs for residents and visitors to enjoy throughout the year. A lookout tower is constructed at the highest point in the forest for people to climb and lookout over the forest and the Village of Morrow. Cabins and campgrounds are added to allow visitors to spend a night in the woods. The land located north of the PUD along the river is converted into a community farm, which is used to produce food for Morrow residents. It also incorporates special educational programs for young residents through a partnership with local schools. There are three bridges for pedestrians and bicyclists to connect the PUD with the farm, and the rest of Morrow, and two access points from the PUD to the river that allow for kayaking and canoeing. The third PUD option (Figure 10) focuses on a communal area, which connects the two residential parts of the PUD and the park around it. The space is a small-scale mixed-use center with commercial uses on the ground floor and residential units on top. At this communal space, there is a gateway entrance to the park and a small trailhead for parking. A recreational play- ground for children is also on site, as is a place to enjoy café refreshments and spend time with the family. The square con- nects the two segments of the PUD with an area of mutual in- terest and activity. There are connections made throughout the residential area through vacant parcels to make the community more walkable and green. Entrance into the neighborhood is from four main access points, including the current ones off Woodland-Morrow Road and Morrow-Blackhawk Road, as well as two new entrances from Morrow-Blackhawk Road, which connect to the commu- nal area in the center and to Thorton Park in the east. The forest Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN 0 400 800 Ft Gateway Community Farm Boat Put-in Single and Two Family Houses Boat Put-in Lookout Tower Conservatory Cabin Figure 9. PUD Option 2. Source: Propose d by students. 0 400 800 Ft Gateway Single Family Golf Trai l (Multi use) Historic Community Park Community Farm Small Retail Shops Two Family Houses Pavilion Playground ine-hole Golf Course Large Single Fa mily Golf Center Information Center Figure 10. PUD Option 3. Source: Propose d by students. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 71  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN is interlaced with a series of natural trails for both biking and hiking. There are two fire towers in the forest for people to climb and lookout over Morrow and to provide points of inter- est for residents and visitors. A community farm is proposed along the river to produce food for Morrow residents, as well as provide a small source of local employment and income gen- eration. It includes a family park on the western edge to add to the draw of the riverfront and the community farming area. A partnership with local schools would be created to teach young residents about nutrition and growing their own food. There is also a bike trail and pedestrian path that cross the river and connect the PUD to the rest of Morrow. Discussion and Conclusion Given the amount and variety of work that the course com- prised, the majority of students found it a valuable experience. The extent to which current planning education in the United States should offer a healthy dose of practice along with theory has been subject to heated debate among students, academics and professional planners in recent years (Sorkin, 2012; Baner- jee & Meyers, 2005; Arendt, 2012). Nonetheless, working with students with what we call mixed capabilities (i.e., design and non-design), posed different challenges in a studio setting. The main takeaway from this experience is the ways in which the instructors structured the studio in order to maximize the pro- ductivity and minimize the potential tensions, which could have arisen from working in a planning studio with mixed-skill stu- dents. What follows outlines these lessons and takeaways. As stated above, these challenges arise from the rather broad scope of planning education in the United States, on the one hand, and the expected quality of the deliverables on the other. To put it differently, the interaction between these two student groups has its advantages as well as disadvantages. Diversify- ing the studio environment and promoting critical thinking can be considered an advantage. In the particular case of this studio, discussions among the design and non-design students about how to better showcase Morrow as a shrinking village during the post-SWOT stage of the project, and during the recommen- dation stage, exemplify the advantages of having a diverse group of students. In many cases, the non-design students chal- lenged the design students’ eagerness to jump into the design stage as soon as possible. That is, the non-design students es- pecially those with economic backgrounds-resisted the tempta- tion to spend more time on design and less on critical thinking and analysis. Instead, they pushed for more in-depth discus- sions surrounding the means for boosting the economy through non-physical or non-design interventions (i.e., financing the projects or seeking out federal or state grant programs). In opposition, the design students were quick to emphasize the role of physical design alternatives or recommendations as the key component of the deliverables. Limited design alterna- tives (options or scenarios), and peer pressure to meet deadlines on only a few students with the required set of design skills, constitute the major disadvantages of working in planning stu- dios with mixed skills. The excessive peer pressure (especially toward the end of the semester) on the few students with archi- tecture or landscape architecture degrees, created, at times, a tense working environment. Building a physical model (with the before and after design components), creating professional qualify drawings in a timely fashion, and compiling a profes- sional report with sufficient illustrations and diagrams, were the three major tasks during the recommendation stage. But be that as it may, to many of the capstone students-es- pecially those who came from non-design or non-physical backgrounds and had no real-world planning experience-the final project before graduation presented a full-fledged oppor- tunity where they could enhance and hone their practical skills for getting ready to enter the job market. These skills included performing the SWOT analysis, participating in or organizing the charrette, scenario building, and teamwork. To enable this to occur, the instructors made provisions to ensure that the students were exposed to a real-world planning project with tangible deliverables and outcomes. As is the case with almost all planning projects, a degree of uncertainty and “wickedness” (Rittel & Webber, 1973) characterized this pro- ject as well. These uncertainties ranged from handling logistical issues (i.e., allocating time for field trips to Morrow or making appointments to meet with the mayor or stakeholders), to data collection (e.g., gathering statistics and demographic data, as- certaining whether Morrow was indeed “shrinking”), to even forming groups. Previous experience in studio-type projects played a key role in time management and dealing with anxiety. In a class with 38 students, less than a third (many of whom were from China) had an architecture, landscape architecture or physical planning background. The instructors ensured that each of the six initial teams in Phase I and the three large groups in Phase II had an equal number of designers alongside non-designers. This decision helped to level the playing field-especially during the recom- mendation or scenario-building stage. While this eased poten- tial tension, other unanticipated problems caused some concern. Estimating the amount of work to be done (for individual team members) turned out to be much harder for some than others. While the students with design experience became responsible for design decisions, the non-designers were in charge of com- posing the report. Academic writing posed some challenges as well; some narratives and initial drafts were found to be less than professional. Moreover, during the last three weeks, the teams were in- structed to incorporate their designs into the body of the report with the text accompanying it. But revising the designs and some coordination issues delay ed finalizing the document. These delays further caused the students to only present their final projects to Morrow’s Mayor and Village Administrator rather than the community at large. While frustrating at times, this experience similar to real-world projects and the students found these experiences quite valuable. Aside from these logistical issues, insufficient design expe- rience in the case of the majority of the planning students posed some serious challenges, which are related to the content of planning education as previously mentioned. While diverse stu- dent backgrounds are certainly useful in most planning projects, they might create major problems at the design thinking or planning stage if enough design-trained planners are not pre- sent. In this particular case, giving focus to the project by collect- ing data on the six supporting systems helped to minimize re- dundancy while increasing efficiency. However, it turned out in some cases that collecting appropriate data on some of the sys- tems (i.e., water and solid waste or energy) was more difficult than it seemed at first. Furthermore, one of the pedagogical goals in this project was to show what a “shrinking town” (or village) looks like physically, spatially and statistically. Thus, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 72  M. AREFI, D. J. EDELMAN collecting coherent and convincing data (both for laypeople as well as experts and decision-makers) was easier said than done. This was perhaps one of the most important, yet intractable, aspects of this studio, which most students found useful. The proposal or recommendation stage and the subsequent design solutions (based on the collected data) turned out to be less interesting and relevant to those who knew they did not wish to pursue urban design in the future. As such the data collection and analysis appealed to some, while the design recommenda- tions drew the attention of other students in this class. Capstone studios, then, with students of mixed educational backgrounds have both pros and cons. Student diversity can create momentum and engage participants to share their per- spectives (i.e., how to think about financing a planning project or how to create socially vibrant neighborhoods) in group ac- tivities and discussions. On the other hand, a minimum level of physical and design savvy seems necessary during the planning and scenario-building stage. The absence of people with design skills can seriously undermine the credibility and plausibility of the recommendations regardless of how sophisticated and ad- vanced students’ social, analytical and quantitative skills might be. With respect to this capstone project, the Main Street group came up with a believable concept. What they could have done better, perhaps, was to propose improved designs. The Innova- tion Center group too could have proposed a stronger project by exploring alternative building placement options within the site. With respect to the PUD group, although they came up with three schemes, they could have focused more on alternate hous- ing schemes, and two of the proposed schemes were rather si- milar. These and many more issues illustrate that diverse edu- cational and disciplinary backgrounds, while valuable, require good design thinking to achieve superior solutions. Despite these reservations, however, this capstone class won the 2013 Directors’ Choice Award for superior work at the Master’s level, which is a highly prestigious award given by the Univer- sity of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning. Acknowledgements The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mayor Mike Erwin of the Village of Morrow, Ohio for funding this project. REFERENCES Adhya, A. (2013). From crisis to projects: A regional agenda for ad- dressing foreclosures in shrinking first suburbs: Lessons from War- ren, Michigan. Urban Design International, 18, 43-60. doi:10.1057/udi.2012.31 Arendt, R. (2012). Planning education: Striking a better balance. Planetizen. http://www.planetizen.com/node/59072 Bluestone, B., & Harrison, B. (1982). The deindustrialization of Amer- ica. New York: Basic Books. Bowns, C. (2013). Shrinkage happens… in small towns too! Respond- ing to de-population and loss of place in Susquehanna River Towns. Urban Design International, 1 8 , 61-77. doi:10.1057/udi.2012.27 Coyle, S. (2011). Sustainable and resilient communities: A comprehen- sive action plan for towns, cities, and regions. Hoboken: The John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Dunham-Jones, E., & Williamson, J. (2011). Retrofitting suburbia: Urban design solutions for redesigning suburbs. Hoboken: The John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Feldhoff, T. (2013). Shrinking communities in Japan: Community ow- nership of assets as a development potential for rural Japan? Urban Design International, 18, 99-109. Hospers, G. (2013). Coping with shrinkage in Europe’s cities and towns. Urban Design International, 1 8 , 78-89. doi:10.1057/udi.2012.29 Kelling, G. L., & Wilson, J. Q. (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety . The Atlantic, March 1. Mayer, H., & Holzheimer, T. (2009). Virginia’s creative economy. Vir- ginia’s Issues and Answe rs , 15, 2-12. Myers, D., & Banerjee, T. (2005). Toward greater heights for planning: Reconciling the differences between profession, practice, and acade- mic field. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71, 121- 129. doi:10.1080/01944360508976687 Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of plan- ning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155-169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730 Sassen, S. (1991). The global city: New York, London. Tokyo, Prince- ton: Princeton University Press. Sorkin, M. (2012). How green is my city: The state of sustainable ur- banism. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 179-182. Warren County Historical Society (1979). Village of morrow compre- hensive plan. www.googlemaps.com Zingale, N., & Riemann, D. (2013). Coping with shrinkage in Germany and the United States: A cross-cultural comparative approach toward sustainable cities. Urban Design International, 18, 90-98. doi:10.1057/udi.2012.30 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 73

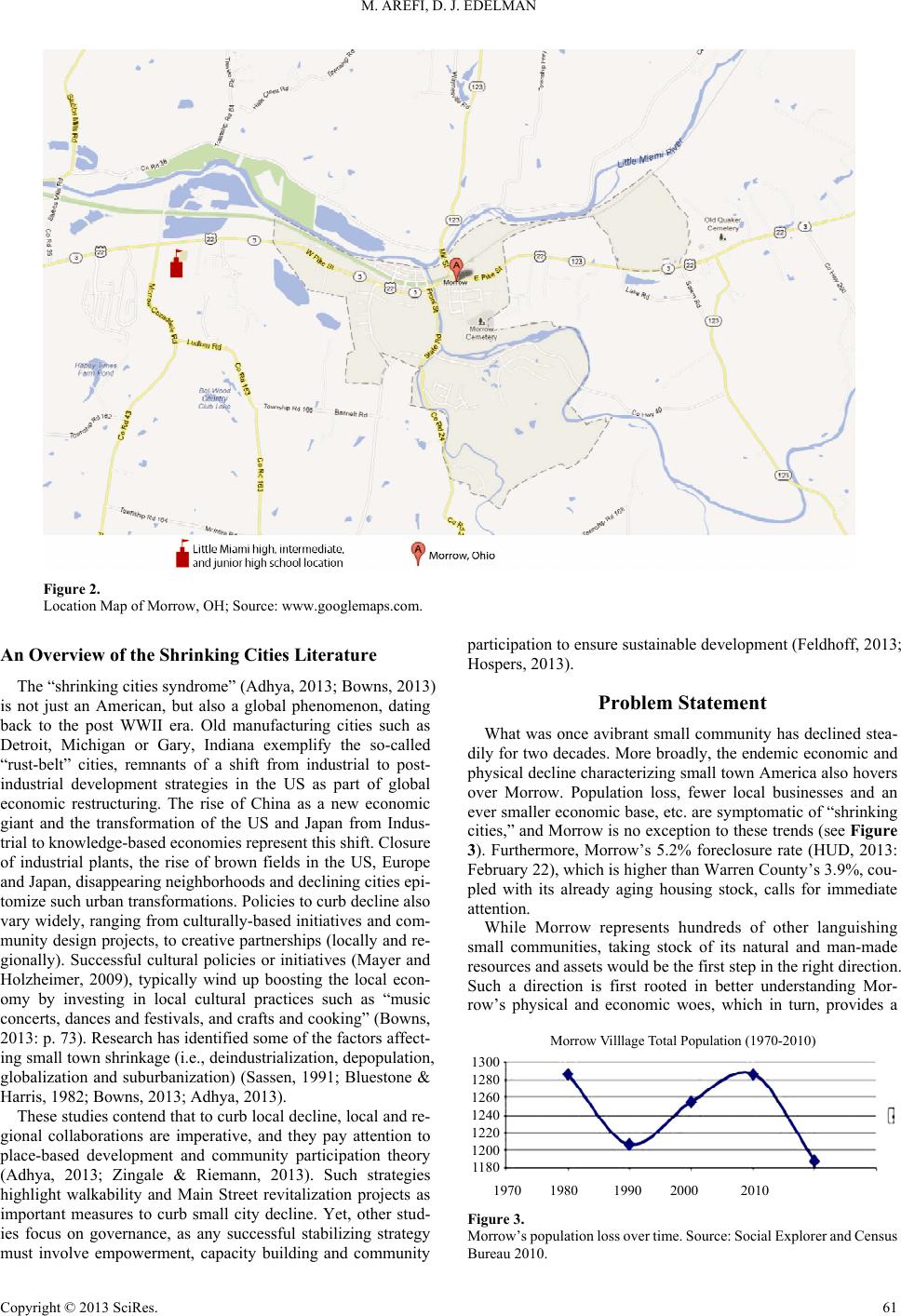

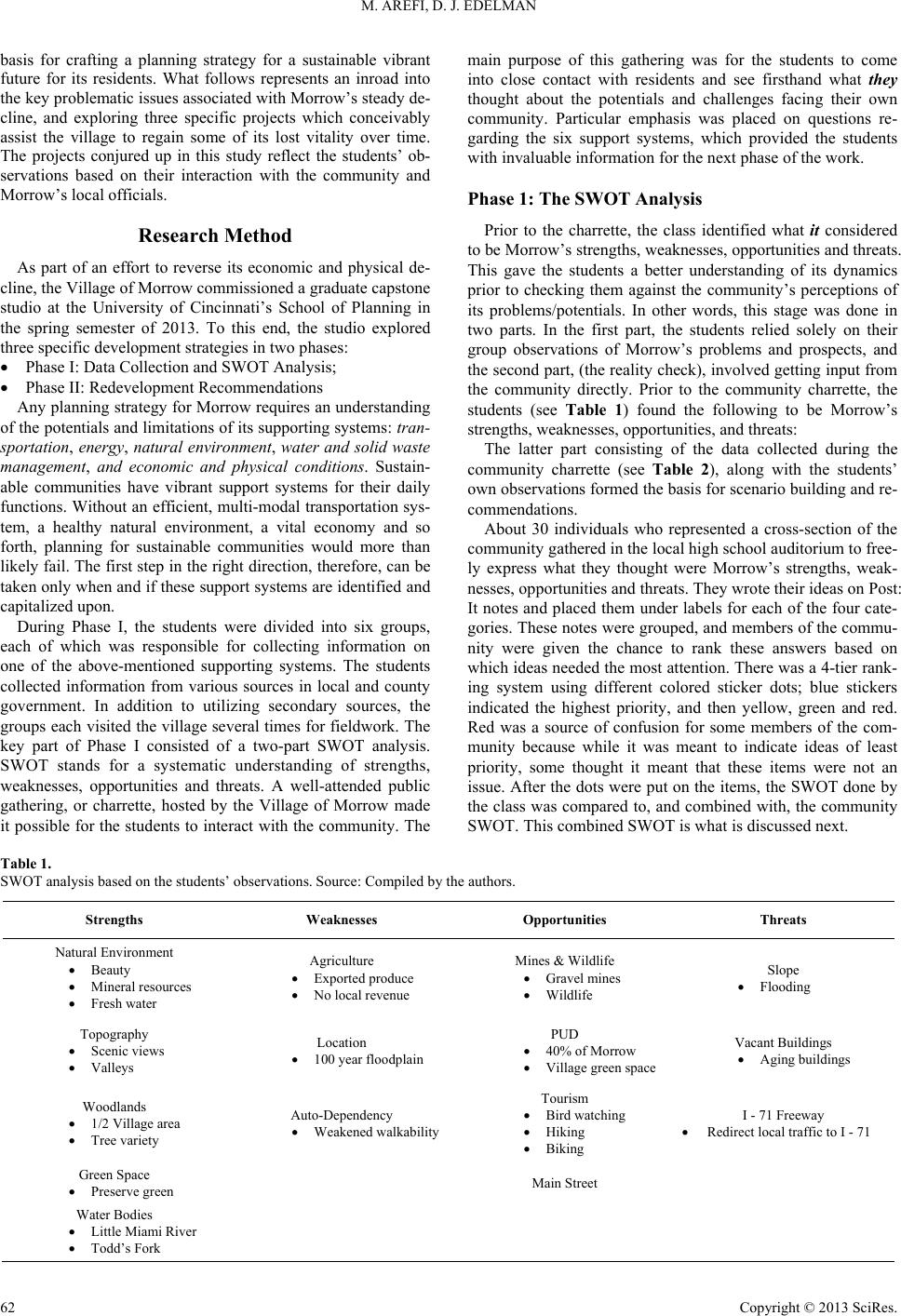

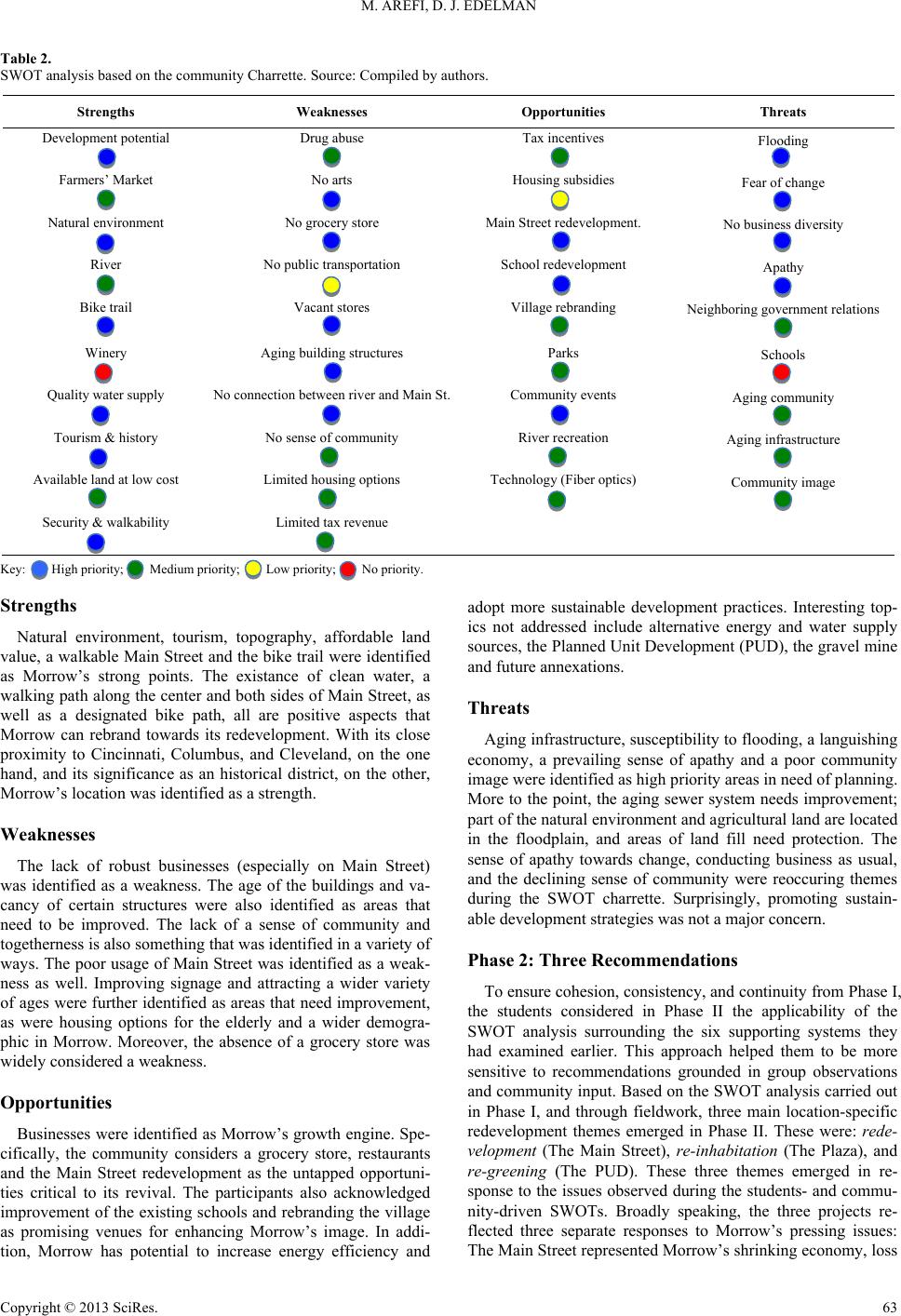

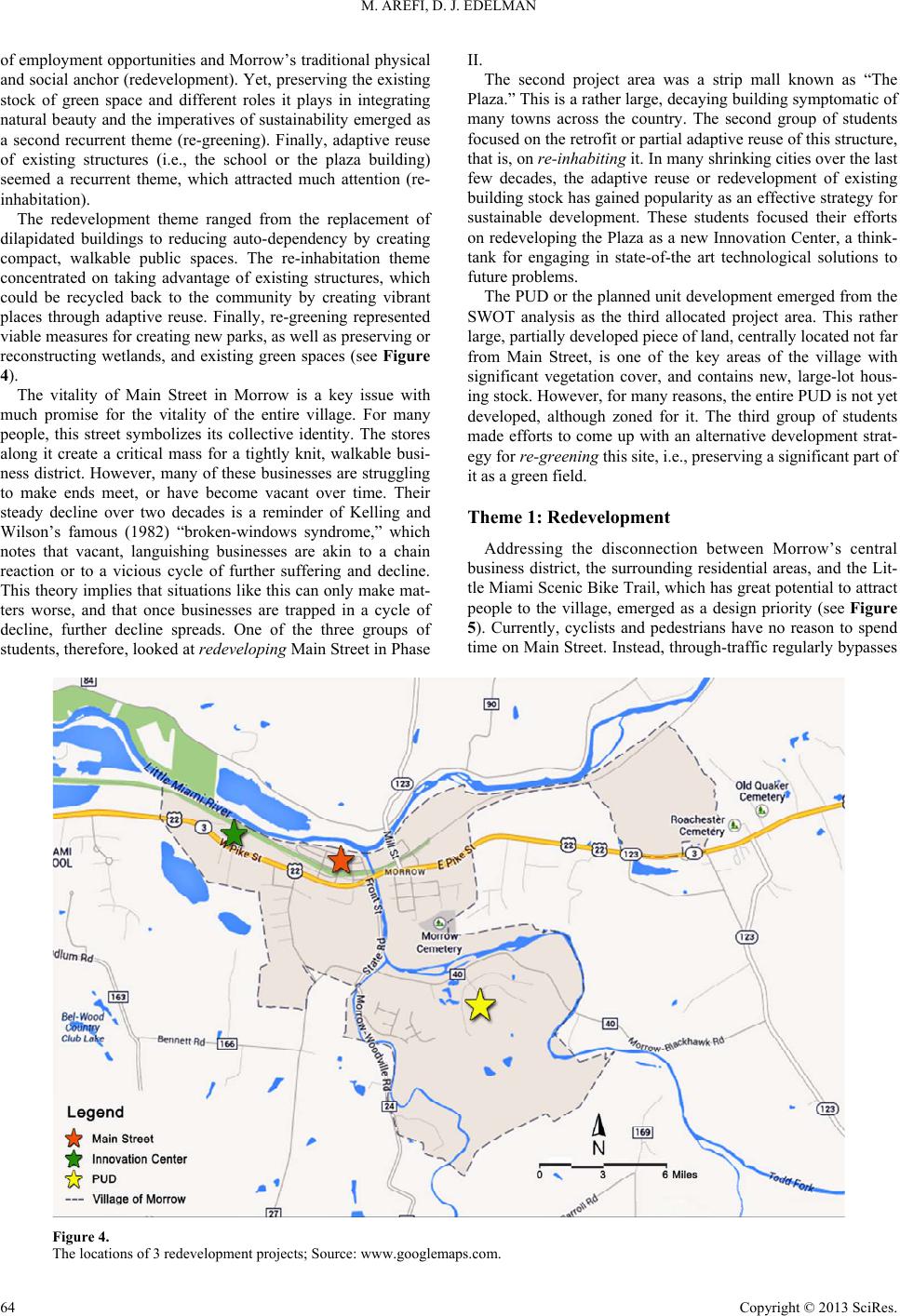

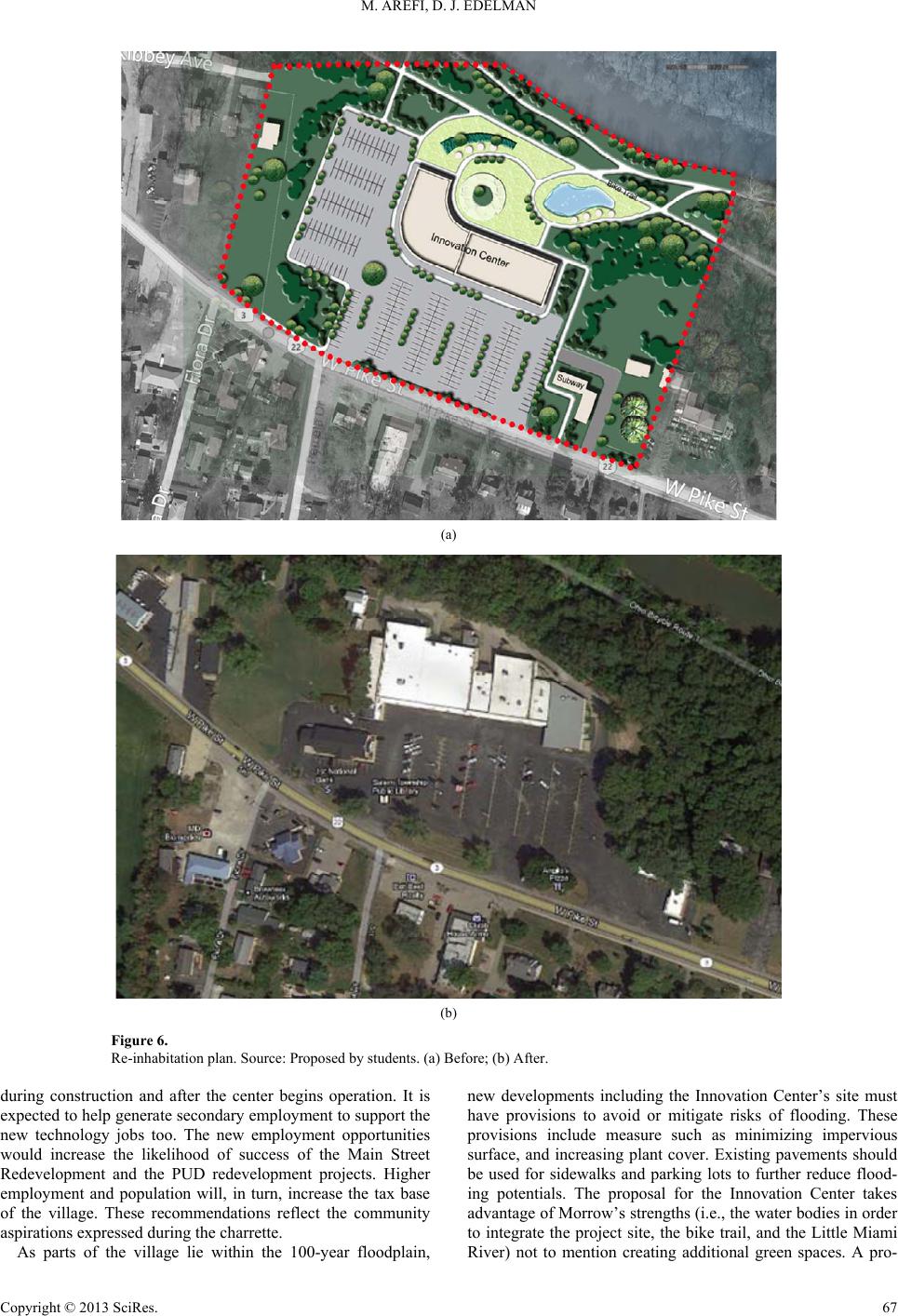

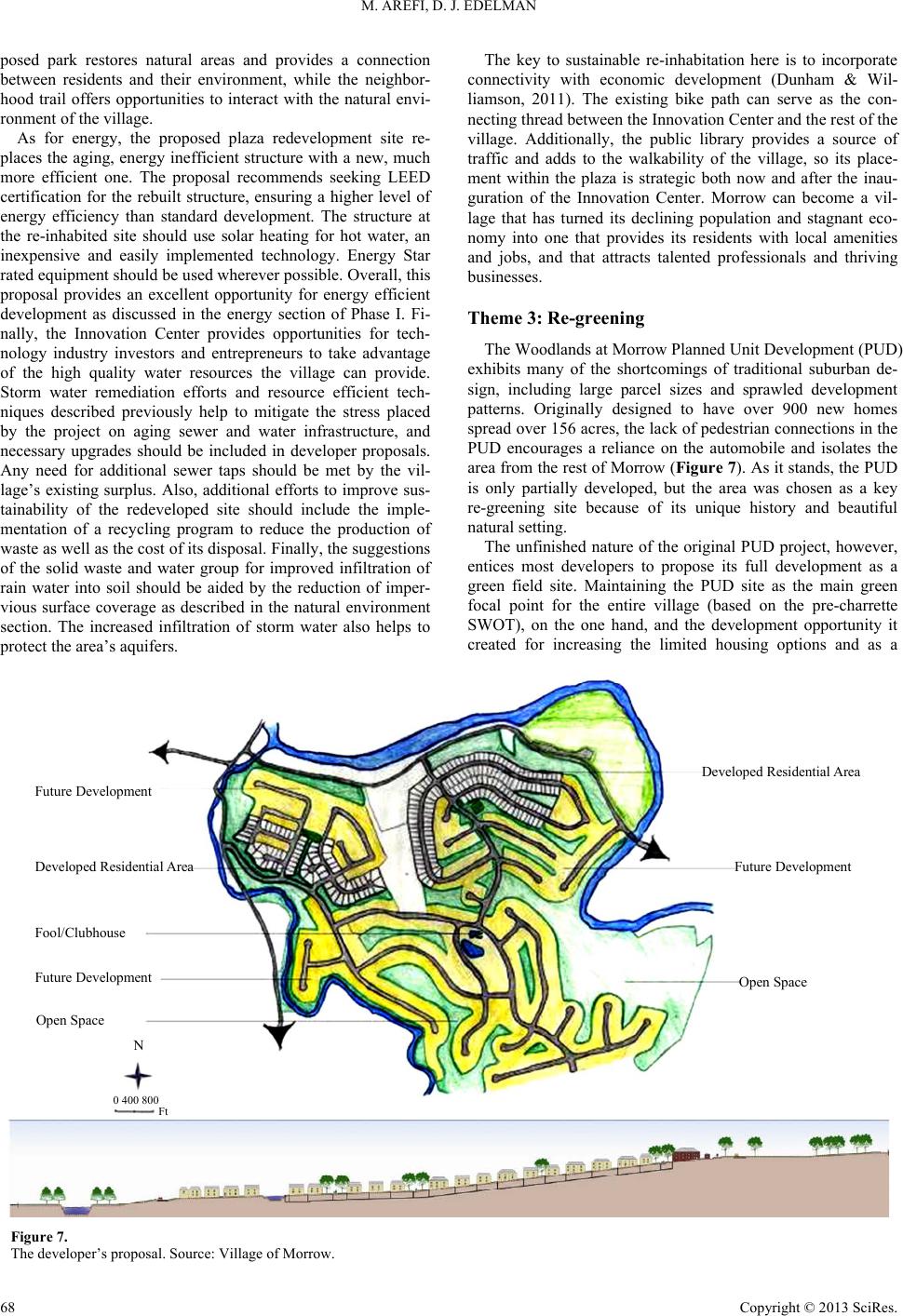

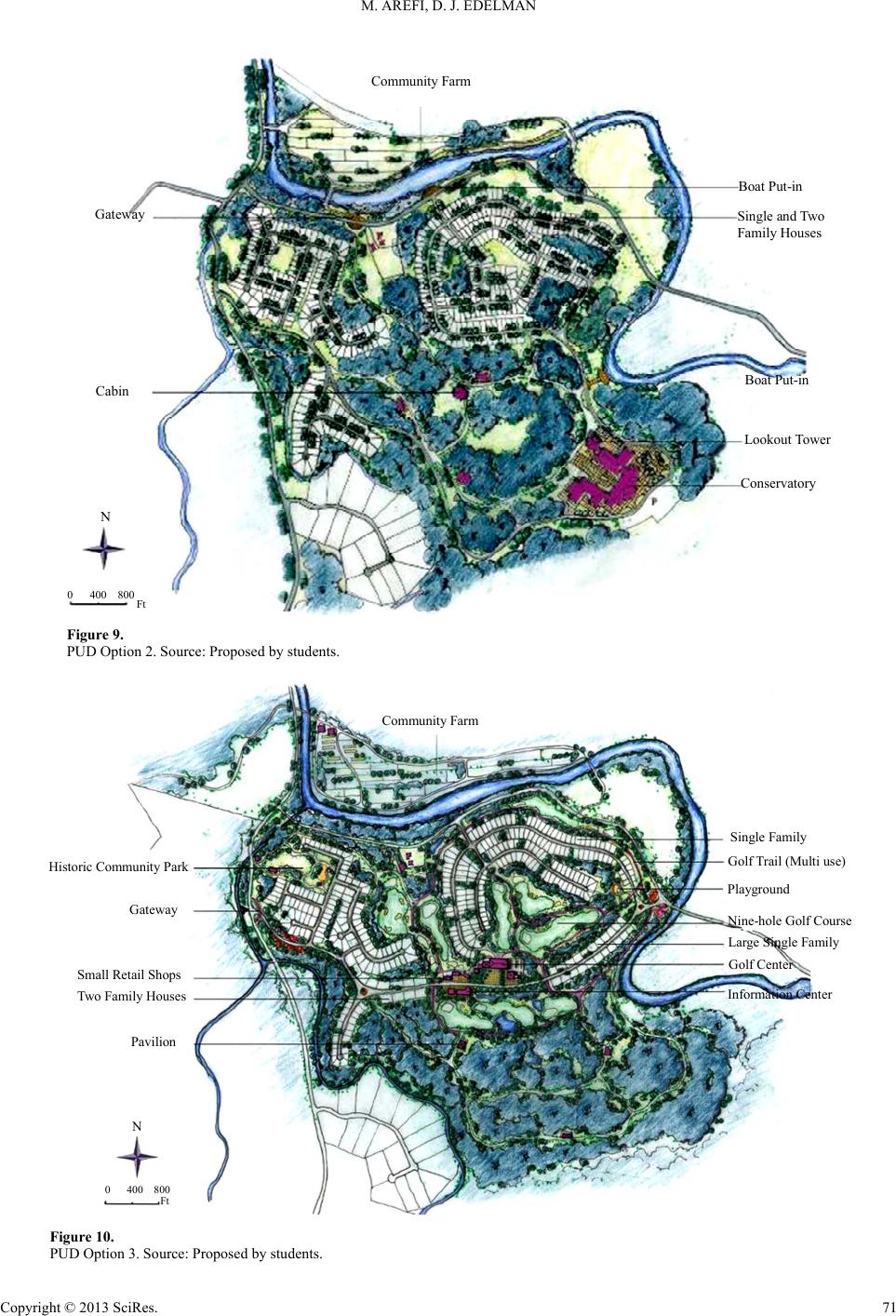

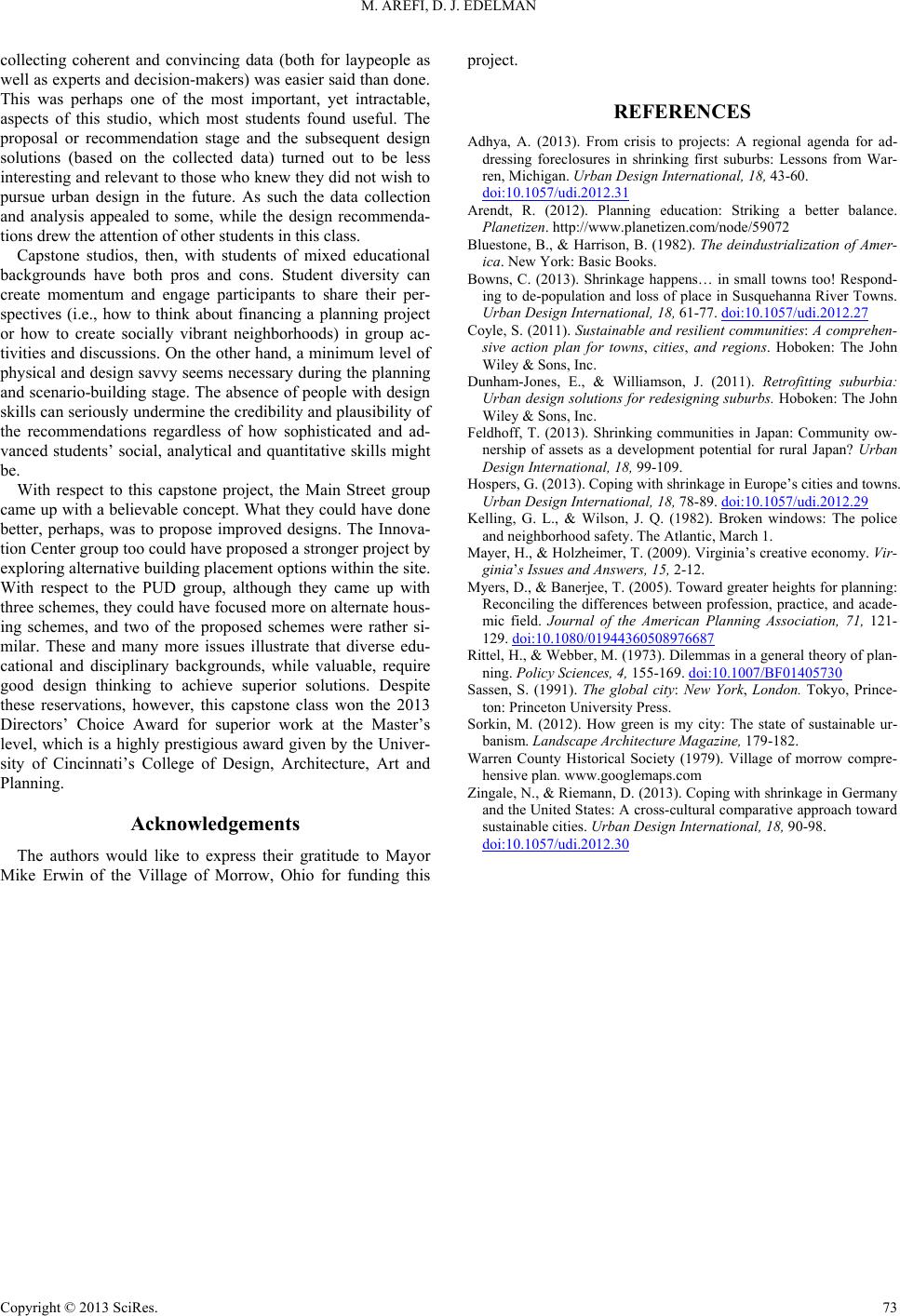

|