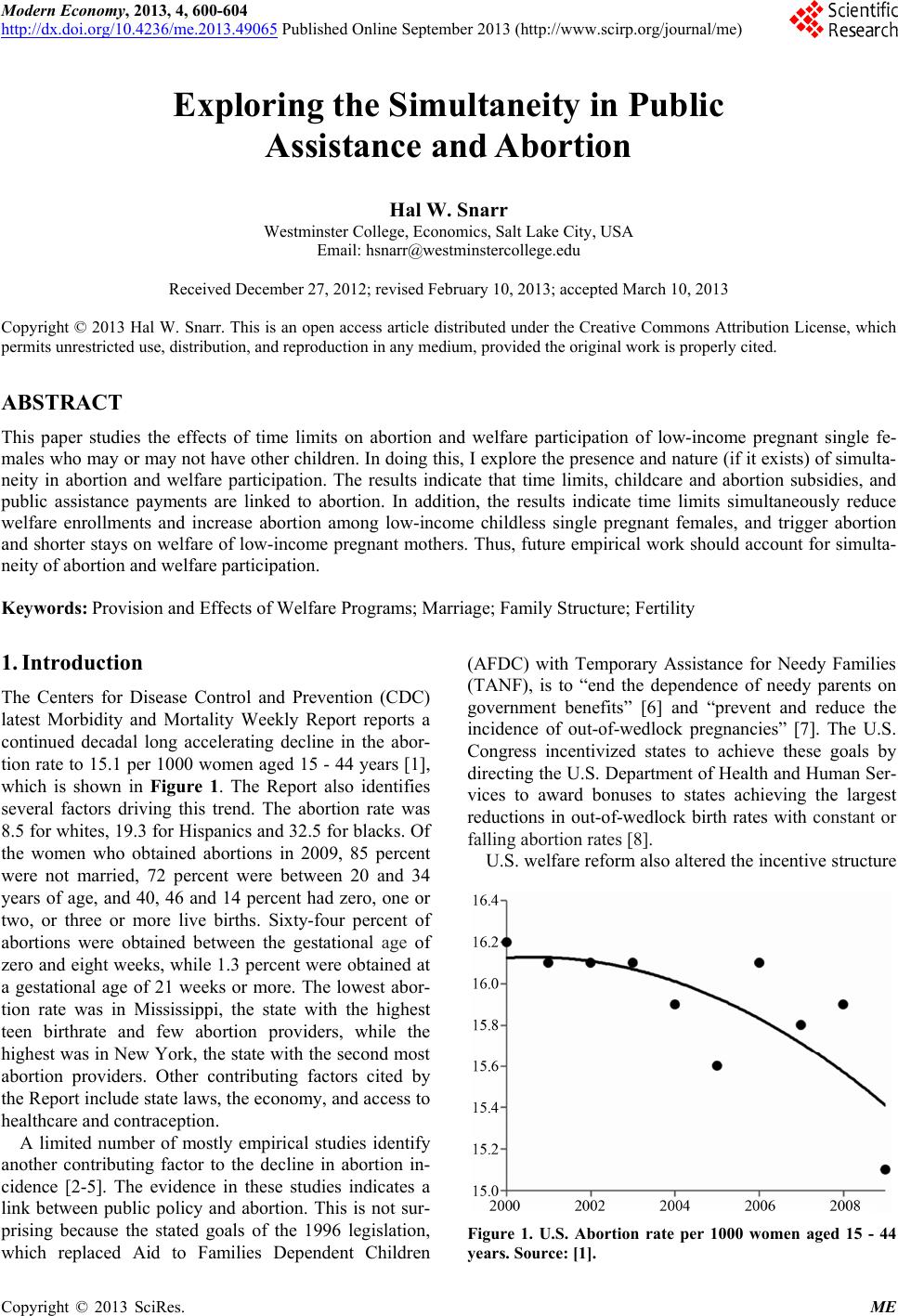

Modern Economy, 2013, 4, 600-604 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/me.2013.49065 Published Online September 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/me) Exploring the Simultaneity in Public Assistance and Abortion Hal W. Snarr Westminster College, Economics, Salt Lake City, USA Email: hsnarr@westminstercollege.edu Received December 27, 2012; revised February 10, 2013; accepted March 10, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Hal W. Snarr. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This paper studies the effects of time limits on abortion and welfare participation of low-income pregnant single fe- males who may or may not have other children. In doing this, I explore the presence and nature (if it exists) of simulta- neity in abortion and welfare participation. The results indicate that time limits, childcare and abortion subsidies, and public assistance payments are linked to abortion. In addition, the results indicate time limits simultaneously reduce welfare enrollments and increase abortion among low-income childless single pregnant females, and trigger abortion and shorter stays on welfare of low-income pregnant mothers. Thus, future empirical work should account for simulta- neity of abortion and welfare participation. Keywords: Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs; Marriage; Family Structure; Fertility 1. Introduction The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report reports a continued decadal long accelerating decline in the abor- tion rate to 15.1 per 1000 women aged 15 - 44 years [1], which is shown in Figure 1. The Report also identifies several factors driving this trend. The abortion rate was 8.5 for whites, 19.3 for Hispanics and 32.5 for blacks. Of the women who obtained abortions in 2009, 85 percent were not married, 72 percent were between 20 and 34 years of age, and 40, 46 and 14 percent had zero, one or two, or three or more live births. Sixty-four percent of abortions were obtained between the gestational age of zero and eight weeks, while 1.3 percent were obtained at a gestational age of 21 weeks or more. The lowest abor- tion rate was in Mississippi, the state with the highest teen birthrate and few abortion providers, while the highest was in New York, the state with the second most abortion providers. Other contributing factors cited by the Report include state laws, the economy, and access to healthcare and contraception. A limited number of mostly empirical studies identify another contributing factor to the decline in abortion in- cidence [2-5]. The evidence in these studies indicates a link between public policy and abortion. This is not sur- prising because the stated goals of the 1996 legislation, which replaced Aid to Families Dependent Children (AFDC) with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), is to “end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits” [6] and “prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies” [7]. The U.S. Congress incentivized states to achieve these goals by directing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Ser- vices to award bonuses to states achieving the largest reductions in out-of-wedlock birth rates with constant or falling abortion rates [8]. U.S. welfare reform also altered the incentive structure Figure 1. U.S. Abortion rate per 1000 women aged 15 - 44 years. Source: [1]. C opyright © 2013 SciRes. ME  H. W. SNARR 601 heads of which low-income households are faced with. Under the new program, participants are required to work, are limited to 5 years of assistance, and can lose all or some assistance money if they fail to work. To date, only [5] have theoretically modeled the abortion effects of welfare reform. They examine two specific aspects of welfare reform: permitting childless pregnant single fe- males to enroll in TANF [9] and lump-sum TANF diver- sion payments [10]. Their model implies that lump-sum diversion TANF payments have lower abortion among low-income mothers but raise it for women who are childless and pregnant. The empirical results only sup- port the first part of that statement. This paper focuses on the effect of time limits on abor- tion to explore the simultaneity of abortion and welfare participation, which may explain why [5] rejected their second hypothesis: diversion payments and TANF eligi- bility for low-income women who are childless and pregnant increase abortion incidence. This issue should concern researchers because failing to account for it can bias coefficient estimates. Although scant research ac- counts for simultaneity in welfare program participation and out-of-wedlock births [11,12], simultaneity of par- ticipation and abortion has been overlooked. 2. Model of Pregnancy Termination and Welfare Enrollment The link between abortion incidence of childless preg- nant single females and two TANF provisions is theo- retically modeled in [5]. It focused on some states per- mitting childless pregnant single females to enroll in TANF and using lump-sum payments to divert potential participants from enrolling in TANF. In this section, I use that model to study the effects of time limits on preg- nancy termination and welfare program participation de- cisions of low-income Pregnant Singles (PS) who may or may not have other children. 2.1. The Budget Constraint Several factors affect PS’s budget constraint. She must decide between pregnancy termination or an out-of-wed- lock birth in month t = 0. If termination is chosen, A = 1, otherwise A = 0. PS may have other children. If so, O = 1, otherwise O = 0. Pregnancy termination costs K in month 0, but birth costs k each month thereafter 0t until the child reaches adulthood in period T. Following [5], public assistance payment P exceeds PS’s subsistence needs but her earnings Y do not because her skill level is too low . PY In the first scenario, PS has other children 1O and is enrolled in welfare in month 0. If PS chooses birth in month zero, t is the age of her newborn. This allows her to receive monthly public assistance payment P until her newborn reaches adulthood at age T. If PS chooses termination, her youngest reaches adulthood earlier. For example, if this child is 12 months old at month 0, she can receive payment P for T – 12 consecutive months. Given that PS’s planning horizon is longer if she chooses birth, I differentiate the two planning horizons with T1and T0 where T0 > T1. More generally, the planning horizon is denoted TA with the subscript taking on the values of indicator A. After month TA, PS must return to work because her youngest child has become an adult. She earns Y every month after returning to work. Thus, PS’s budget constraint before welfare reform 0R is 1 0 0 0 t tT Tt tT 10 1 1 1, 0 1 t AP K AP APA P k cAO RT AYA P k Y (1.0) If time limit τ is the maximum number of months PS can receive public assistance, and it is less than PS’s planning horizon 10 TT , welfare reform (R = 1) alters the budget constraint above: 0 0 0 0 t t tT tT 1 1 1, 1 1 t AP K AP APA P k cAO R AYA Yk Y (1.1) In the second scenario, PS does not have other chil- dren (O = 0) and is working a low wage job. Because she has no other children, her planning horizon is T0. Choos- ing termination means PS continues to work and earn Y per month. Choosing birth, however, means childless PS stops working and enrolls in public assistance. Hence, her budget constraint pre-reform (R = 0) is 0 0 0 t t tT 0 1 0, 0 1 t AY K AY cAO RAYAPkT Y (2.0) but is 0 0 0 t t tT tT 0 1 1 0, 1 1 t AY K AY AYA P k cAO R AYA Yk Y (2.1) post reform. With regard to time limit τ, because child- less PS is not enrolled in public assistance in period 0, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ME  H. W. SNARR 602 she can remain on assistance until month τ. PS with chil- dren, on the other hand, was enrolled in public assistance in month 0, meaning she must exit public assistance the month before τ is reached. Thus, 0t is used in Equation (1.1) but 0t is used in Equation (2.1) 2.2. Constrained Lifetime Utility Given the budget constraints above, PS maximizes the same lifetime utility function that the agent in [5] maxi- mizes: 0 t t t Uu (3) where 0,1 , and , tt tt uc AcaAbA 1 . Equation (3) is adapted from the model in [13] with the agent’s decisions collapsing to pregnancy termination or birth 1A 0 t A a . Periodic utility function u exhibiting constant marginal utility of consumption equaling 1 follows from [14]. If θ and φ are both in in- terval (0, 1), then and t b are asymptotic in t. These expressions model pregnancy termination remorse and out-of-wedlock childbearing regret waning over time, respectively. Substituting the budget constraints into (3) gives 0 ,, t t t V AORcAORAA 1 (4) where 01 t t a a and 01 t t b b The difference in PS’s lifetime utility between choos- ing pregnancy termination and proceeding with an out- of-wedlock birth is given by ,1, 0, OR VVORVOR or , 0 1, 0, t ORt t t VcORc OR (5) Equation (5) is the gain (or loss) in PS’s lifetime utility resulting from choosing pregnancy termination over an out-of-wedlock birth. Its value depends on several factors like, for example, PS’s disutility of pregnancy termina- tion (α) relative to her disutility of out-of-wedlock (β), the value of public assistance payment P relative to what she can earn in the labor market (Y), the one-time cost of pregnancy termination (K), the monthly costs of raising children, the age of her youngest child (TA), the length of welfare reform’s time limit (τ), whether she has other children or not, and whether or not welfare reform has been enacted. 2.3. Welfare Reform’s Effect on Pregnancy Termination In this section, the marginal benefits of pregnancy ter- mination before and after welfare reform is enacted are compared for PS who has other children to one who does not. For childless PS, Equation (5) simplifies to 00 11 0,0 11 TT VKkY P (6) but when public assistance is limited to τ months Equa- tion (5) simplifies to 011 0,1 11 T VKkY P . (7) Given values of K and k, suppose policy makers picked P, which happened to make childless PS indiffer- ent between birth and termination when continued par- ticipation in public assistance was unlimited. Thus, 0 = ΔV0,0, which can be expanded as follows: 01 0 1 0,0 1 1 1 01 1 T T VKkY YP P Replacing the expression in [·] with ΔV0,1, and simpli- fying yields 01 1 0,1 1 T VP Y , which is positive because P > Y, and 0 < ρ < 1 and τ < T0 imply 01 1T . Thus, imposing a time limit welfare receipt increases termination incidence among low-in- come childless pregnant singles, and simultaneously in- hibits their enrollment in public assistance. For PS mother, Equation (7) simplifies to 00 1 11 1 1,0 11 TT T VKkY P (8) but when public assistance is limited to τ months Equa- tion (5) simplifies to 01 1,1 1 T VK k . (9) Because ΔV0,0 can be expanded as follows 00 1 1 11 1 0,0 1 11 1 TT T T VKk Y YP P Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ME  H. W. SNARR 603 And ΔV0,0 = 0, the expression in [·] is simply ΔV1,0. Making the switch and simplifying yields 11 1,01 T VP Y which is positive because P > Y, and 0 < ρ < 1 and 0 < T1 imply . Thus, prior to the imposition of a time limit, a childless PS who is indifferent between termina- tion and out-of-wedlock birth chooses termination if she was already the mother of other children. 11 1T Similarly, because ΔV0,0 can be written as 00 11 0,0 11 TT VKkY P And ΔV0,0 = 0, the expression in [·] is simply ΔV1,1. Making the switch and simplifying yields 01 1,1 1 T VP Y which is positive because P > Y, and 0 < ρ < 1 and 0 < T0 imply . Because T1 < T0, 01 1T 0 11 1T T or 0 11 1T T or 1,0 1,1 VV Thus, limiting the length of time a PS can remain on public assistance makes pregnancy termination more likely for those with other children. Interestingly enough, the model indicates that preg- nancy termination is a more difficult decision for child- less PS who is faced with public assistance time limits than it is for PS mothers not faced with time limits. Ex- panding ΔV1,0 as follows illustrates this 11 1 1,0 11 T VPY 1 PY Because the quantity in [·] is , rearranging the above result gives 0,1 V 1 0,11,01 VV PY Therefore, if low-skilled childless PS females are in- different between pregnancy termination and out-of- wedlock birth before time limits are posed, the following holds: 0,00,1 1,01,1 0VVVV. Thus, the gain to pregnancy termination is greatest for a PS female who has other children and is faced with time limits on public assistance. This is followed in de- clining order by a PS who has other children and is enti- tled to public assistance payments over her lifespan, a childless PS who is faced with time limits, and a child- less PS who is entitled to continuous public assistance. 2.4. Other Policy Effects Comparative static analysis is used to examine how other policies like childcare and abortion subsidies and the value of public assistance payments affect pregnancy ter- minations of both types of PS before and after welfare reform. Because ΔVO,R can be expressed in terms of ΔV1,1 for all O and R, all are rewritten as follows. 01 0,01,1 1 T VV P Y , 1 0,11,11 VV PY , and 0 11 1 1,0 1,11 T T VV PY . Doing the above simplifies the analysis greatly. The devoutness or religiosity of PS affects pregnancy termination [15] via regret parameter α. If religion is more important in period 2 than it is in period 1, PS in the more religious period will be more reluctant to choose pregnancy termination 21 . If the differ- ence in α2 and α1 is large enough such that the gain to PS mothers faced with time limits is negative aa 1,1 0V , the gains are negative for all others: 0,00,11,01,1 0VVVV (10) Thus, policies that are designed to humanize the fetus reduce abortion incidence. The intuitive nature of this result lends credence to the model, and the policy impli- cations that follow. Policy makers wishing to reduce terminations among low-income PS mothers can affect it via changes to childcare and abortion costs: 01 1,1 1,1 and 1 1 T VV kK Because 1,1 Vk is positive due to 0 < ρ < 1 and T0 > 0, subsidizing childcare (reducing k) reduces the gains to abortion. The partial derivative on the left indi- cates that raising the cost of abortion via reducing abor- tion subsidies or restricting its access (physically or le- gally) reduces the gains associated with it [16]. If either action is such that the gain to a PS mother who is faced with time limits is negative , property (10) holds. 1,1 0V Policy makers can affect reductions in pregnancy ter- minations by raising public assistance payment P be- cause the following partial derivatives are all negative: 01 0,0 1 T V P , Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ME  H. W. SNARR Copyright © 2013 SciRes. ME 604 1 0,1 1 V P , and 0 11 1 1,0 1 T T V P . If the increase in public assistance payment P is large enough to make the gain to abortion for a PS mother who is faced with time limits negative , property (10) holds. This makes sense given that raising payment P reduces the cost of raising children. 1,1 0V 3. Conclusions The results in this paper indicate a behavioral response to time limits may simultaneously reduce welfare program enrollment and increase abortion incidence among low- income childless single pregnant females. With respect to low-income pregnant single mothers, time limits trigger abortion and shorter stays on welfare. Both of these re- sults suggest that future empirical work should account for simultaneity of abortion incidence and welfare par- ticipation. This paper also informs policy. The results indicate that time limits, childcare and abortion subsidies, and public assistance payments are linked to abortion inci- dence. Welfare reform in general could be driving much of the decadal decline in the abortion rate. The results also help to support the CDC’s claim that factors such as abortion access, state laws, the economy, and access to healthcare and contraception contribute to the reduction in abortion incidence. REFERENCES [1] CDC, “Abortion Surveillance—United States,” 2009. [2] M. Camasso, “Isolating the Family Cap Effect on Fertility Behavior: Evidence from New Jersey’s Family Develop- ment Program Experiment,” Contemporary Economic Po- licy, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2004, pp. 453-467. doi:10.1093/cep/byh034 [3] T. Joyce, R. Kaestner, S. Korenman and S. Henshaw, “Family Cap Provisions and Changes in Births and Abor- tions,” Population Research and Policy Review, Vol. 23, No. 5-6, 2004, pp. 475-511. doi:10.1007/s11113-004-3461-7 [4] J. Klerman, “Fertility Effects of Medicaid Funding of Abortions: A Disaggregated Analysis,” Mimeo, RAND, Santa Monica, 1998. [5] H. Snarr and J. Edward, “Does Income Support Increase Abortions?” Social Choice and Welfare, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2009, pp. 575-599. doi:10.1007/s00355-009-0380-x [6] Social Security Act–Sec. 401. [42 U.S.C. 601] (a)(2) [7] Social Security Act–Sec. 401. [42 U.S.C. 601] (a)(3) [8] 2001 TANF Annual Report to Congress. www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ofa/data-reports/ar2001/chapt er08.pdf [9] G. Rowe and J. Versteeg, “Welfare Rules Databook: State TANF Policies as of July 2003,” Urban Institute, 2005. www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411183_WRD_2006.pdf [10] C. Harvey and M. Berkowitz, “Review of Diversion Pro- grams,” Disability Research Institute, 2006. www.dri.uiuc.edu/research [11] H. Snarr, “Was It the Economy or Reform That Precipi- tated the Steep Decline in the Welfare Caseload?” Ap- plied Economics, Vol. 45, No. 4, 2013, pp. 525-540. doi:10.1080/00036846.2011.607135 [12] L. Stevans, “Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and Non-Marital Births in the USA: An Exami- nation of Causality,” Applied Economics, Vol. 28, No. 4, 1996, pp. 417-427. doi:10.1080/000368496328542 [13] T. Kane and D. Staiger, “Abortion Access and Teen Motherhood,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 111, No. 2, 1996, pp. 467-506. doi:10.2307/2946685 [14] H. Fang and D. Silverman, “On the Compassion of Time- Limited Welfare Programs,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 88, No. 7-8, 2004, pp. 1445-1470. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00183-4 [15] R. King, S. Myers and D. Byrne, “The Demand for Abor- tion by Unmarried Teenagers: Economic Factors, Age, Ethnicity and Religiosity Matter,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 51, No. 2, 1992, pp. 223- 235. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1992.tb03349.x [16] M. Medoff, “The Determinants and Impact of State Abor- tion Restrictions,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 61, No. 2, 2002, pp. 481-493. doi:10.1111/1536-7150.00169

|