Open Journal of Leadership 2013. Vol.2, No.3, 45-55 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojl) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojl.2013.23006 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 45 The Science of Leading Yourself: A Missing Piece in the Health Care Transformation Puzzle* Wiley W. Souba Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, USA Email: Chip.Souba@Dartmouth.edu Received June 10th, 2013; revised July 18th, 2013; accepted August 8th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Wiley W. Souba. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Personal transformation is a prerequisite for sustainable transformation of our health care system. Inte- grating research from the language sciences, phenomenology, psychology and neurobiology, this article reviews the science of leading oneself. Because this “inward” journey can be alien and disorienting, the Language Leadership Performance Model is helpful in illustrating the relationship between the circum- stances the leader is dealing with (the leadership challenge), the context (point of view) the leader brings to that challenge, and the leader’s way of being and acting (the definitive source of the leader’s perform- ance). Using language, effective leaders reframe their leadership challenges such that their naturally cor- related ways of being and acting provide them with new opportunity sets for exercising exemplary lead- ership. Using a house metaphor (The House of Leadership), a foundation for being a leader and a frame- work for exercising leadership are constructed. Laying the foundation of the model involves mastering the four pillars of being a leader. Erecting the framework entails building a contextual schema, which, when mastered, becomes a construct that in any leadership situation gives one the power to lead effectively as one’s natural self-expression. Both of these activities—laying the foundation and erecting the frame- work—involve a deconstruction of one’s existing leadership paradigm. Finally, A Heuristic for Leading Oneself is offered as a useful guide or owner’s manual as one embarks on this inward journey. Leading oneself is a uniquely human activity—studying it and how it works is a vital piece in solving the health care transformation puzzle. Keywords: Leadership; Language; Health Care Reform; Ontology; Phenomenology; Academic Medicine Introduction “Progress is impossible without change,” wrote George Ber- nard Shaw, “and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything” (Shaw, 1920). This is, perhaps, our greatest leadership challenge in medicine. Virtually everyone acknowl- edges that the status quo isn’t working and that a radical over- haul of our health care system is needed. But when it comes to changing, we often overlook a fundamental truth: systems don’t change in any meaningful kind of way until and unless people change first (Wind & Crook, 2006; Souba, 2009; Souba, 2011a). In Peter Block’s words, “If there is no transformation inside each of us, all the structural change in the world will have no impact on our institutions” (Block, 1996). We cannot solve our quality, cost and access challenges with technical solutions alone. We, too, must change. We must change how we think about health care, how we speak about its future, and how we work together to correct its failings. In order to reframe how we approach our health care challenges, a renewed context for lea- dership is needed, one that distinguishes being a leader as the foundation for what leaders know and do (Souba, 2011a; Souba, 2011b). If you’re not being a leader, it is impossible to act like a leader. Goss (Goss, 1995) explains: Transformation and change are different phenomena. Change is a function of altering what you are doing—to improve some- thing that is already possible in your reality (better, different, more). Transformation is a function of altering the way you are being—to create something that is currently not possible in your reality. Most approaches to leadership development are based on the assumption that inculcating people with specific characteristics and traits will make them effective leaders (Zaccaro, Kemp, & Bader, 2004). However, effective leaders know that leadership does not come from imitating certain styles or memorizing an article on the attributes of successful leaders. Barker (1997) re- minds us that “we have become mired in an obsession with the rich and powerful, with traits, characteristics, behaviors, roles, styles, and abilities of people who by hook or by crook have obtained high positions, [yet] we know little if anything more about leadership.” Leading oneself is less about styles and traits and more about discovering one’s natural self-expression. This is a key prerequisite for leading others. Parikh (2005) explains: Unless one knows how to lead one’s self, it would be pre- sumptuous for anyone to be able to lead others effectively… Leading one’s self implies cultivating the skills and processes to experience a higher level of self-identity beyond one’s ordi- nary, reactive ego level… *Funding/Support: None. Other disclosures: None. Ethical approval: Not applicable.  W. W. SOUBA To get beyond their “ordinary, reactive ego”, effective lead- ers relentlessly work on “unconcealing” the prevailing mental maps that they carry around in their heads (Souba, 2011a; Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). This unveiling is critical because leaders are more effective when they are not limited by their hidden frames of reference and taken-for-granted worldviews. This new way of understanding leadership requires that leaders spend more time learning about and leading themselves. Erik- sen (2008) expounds: Too often, leaders of organizational change see the organiza- tion as an object separate of themselves… To be an effective leader, one must understand the nature of leadership, one’s self, and [the] organization within the unfolding of one’s day-to-day experience… [It is] clear how important it is for a leader to be the organizational change he or she seeks. Socrates reminds us that the unexamined life is not worth living (Plato, 1998). To lead effectively, we must begin by exa- mining ourselves. In this essay, I review the science of leading oneself, integrating research from the language sciences, phe- nomenology, psychology and neurobiology, disciplines that have advanced our understanding of this inward aspect of lead- ership. Leading oneself is a uniquely human activity—studying it and how it works is a vital piece in solving the health care transformation puzzle. The Connectome You Are Today Determines the Leader You Are Today Research in neuroscience has made it unambiguously clear that every aspect of our life experience and every choice we make is generated by neuronal patterns in our brain (Pascual- Leone, Amedi, Fregni, & Merabet, 2006; Kolb, Gibb, & Rob- inson, 1995; LeDoux, 2003; McGilchrist, 2012; Tse, 2013). MIT professor Sebastian Seung (Seung, 2012) contends that who you are, moment to moment, situation to situation lies in the specific connections between your neurons, which change as you learn and grow. The term connectome refers to the total- ity of connections between neurons in a nervous system. While your neural networks at any given moment encode your thoughts, feelings and perceptions, you also have a “typical” way of being our think of as personality, which is the self in- voked by the idea that you are your connectome. Both your genome and your experiences shape and mold your connectome, acting as critical determinants of the “way you wound up being” at any point in time in your life. While your genome is determined at the moment of fertilization, your connectome changes throughout your life. Your life experi- ences (in particular the stressful, traumatic ones) change your connectome by rewiring, reweighting, reconnecting, and/or re- generating synapses (Seung, 2012). Because of the plasticity of the brain in children, the wiring that occurs during childhood is an especially important landscaper of brain structure and func- tion (Teicher, 2002; Bluck & Habermas, 2001; Miller, 2008; Staudinger, 1999; Brownlee, 1996). While we are not born with a neural network that is code for “I am inadequate”, over time, such networks can become reflexive and automatic in children who are consistently humiliated and shamed. When these neu- ral circuits are triggered by certain events later in life, the fa- miliar feelings of anxiety, ineptness, and fear are re-activated. To some extent, all children develop feelings of inadequacy that are the result of their brain’s misinterpretation of some- thing someone said or did that was misconstrued as meaning they were unacceptable, didn’t belong or fit in, or didn’t meas- ure up (Souba, 2006). These errors in prospection occur be- cause simulations are unrepresentative (we tend to remember our best and worst experiences), essentialized (we omit features that can influence our experience), abbreviated (we select only a few moments of a future event), and decontextualized (we exclude contexts that can shape our experiences) (Gilbert & Wilson, 2007). The brain’s account of an event (I got a “D” on the test so I’m stupid) is an inaccurate version of what really happened (I got a “D” on the test), but the brain’s interpretation becomes our reality and our truth. These erroneous thought constructs originate in childhood when we are impressionable, vulnerable and lack the cognitive maturity to reason logically. As we learn what’s acceptable and what’s important (and what’s not), we label ourselves with certain life-long deficien- cies and imperfections. Perhaps our accomplishments in school didn’t live up to our parents’ expectations and we decided that we’re “not smart enough.” Such “self-diagnoses” are invariably “terminal”; if, at a young age, you indict yourself as inadequate, try as you might, you can never quite measure up (Souba, 2011b). When children believe that something is wrong with them, they instinctively develop survival strategies. They “design” themselves to have a set of thought processes, behaviors, and ways of doing things that seemingly give them some measure of success. These coping strategies shape our personality and contribute to “the way we wound up being.” For example, one of the ways virtually all human beings “wound up being” is averse to change. It is not changed per se that we are opposed to; rather, it’s the associated loss and fear that we (understandably) resist (Souba, 2008). These underlying default “survival” circuits are genetically programmed and designed to respond unconditionally to stimuli arising from challenging life circumstances (Atkinson B., At- kinson L., Kutz, Lata P., Lata J., & Szekely, 2005). While all of us are born with these neural response programs, they become wired uniquely in each of us, based in part upon the emotion- ally significant experiences we’ve had in our lives. In John Green’s words, “You don’t remember what happened. What you remember becomes what happened” (Green, 2006). Self-defeating stories are difficult to rewrite because they are deeply rooted in neural operating systems that are encoded to carry out their instructions automatically when activated. For new, more positive (constructive) narratives to become suffi- ciently wired into our neural circuitry we must first become aware of the encumbering narratives that tend to run our lives. Without this expanded awareness, our programmed (and coun- terproductive) ways of being and acting will routinely be trig- gered whenever we are confronted with a stressful leadership challenge. I am belaboring the point about these limiting “ways we wound up being” for two reasons. First, we do not wind up being the way we are solely by chance. As we inevitably be- come acculturated and indoctrinated, we erect barriers to the full range of possible ways of being. These ways of being are reinforced by our parents when we’re young (“You’ll never make it if you don’t get good grades”) and later in life by our profession (“You’ll never earn credibility unless you get pro- moted”). Paradoxically, our attempts to overcome our perceiv- ed imperfections result in ways of being and acting that further widen the gap between our inauthentic and true selves. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 46  W. W. SOUBA Second, we tend to overlook that we are not stuck with our automatic ways of being and acting when we are confronted with a leadership challenge. The plasticity of the adult brain is indisputable, allowing us to “go beyond” the way we wound up being (Buonomano & Merzenich, 1998). Until you have re-in- vented yourself to be free from the constraints of your past (including your past successes), you will not have the power to deal effectively with what is the source of resistance to change, either your own or others (Goss, 1995). This is critical as expanding our portfolio of possible leader- ship strategies will allow each of us to exercise more competent leadership under a more comprehensive range of situations. Thus, we must be willing to transcend the way we “wound up being”, rather than simply tweaking it. We must expand our opportunity set of ways of being, thinking, speaking and acting rather than being stuck with a narrow repertoire of leadership options. Flipping the Prevailing Paradigm of Leadership At the core of most models of leadership lies the premise that knowledge is the foundation for leading effectively (Figure 1) —the more the leader knows about goal setting, strategy, and change management, the more effective he or she will be. This implicit leadership theory—leadership equated with a person in charge who has answers—is pervasive. It is the way most ex- ecutives, deans, and department chairs think about leadership. We learned to think this way from our superiors and role mod- els. This way of thinking about and exercising leadership hap- pens without much conscious intent and thus is difficult to challenge or even discuss. It has become woven seamlessly into the fabric of academic medicine’s culture. This way of teaching leadership, which is anchored in theo- ries and explanations, is not wrong but it is no longer adequate. Theories of leadership, while useful for analysis and discussion, do not confer what it is to be a leader and to exercise leadership effectively. Theories do not grant the “boots-on-the-ground” being and actions of effective leaders. Moreover, human beings do not lead from a theoretical approach; we lead from the per- spective of the way leadership is experienced. Explanations alone don’t teach what is required to be a leader much as text- books don’t impart what it is to be a doctor or chef or pianist. Knowing is not enough. By contrast, an emerging, new model anchors effective lead- ership in the leader’s way of being (Figure 1). What is distinc- tive about this ontological phenomenological perspective is that it provides access to ways of exercising effective leadership as-lived, in the first-person, in the real world, in real time and with real results (Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). Neuroscience tells us about what happens “in here” but we can’t actually ex- perience our activated neural networks in vivo; we can only ex- perience what is generated “in here” out in the world, that is, “out here” where leadership and life happen. Most of us are not clear about this so we encounter life through a set of beliefs or theories or concepts. In Noë’s words, “You are not your brain. Your brain is in your head but you are not. Where you and I are—where we exist—is out here in the world” (Noë, 2009). The inimitability of the ontological phenomenological in- quiry resides in its capacity to disclose the actual nature of be- ing a leader and exercising leadership by revealing hidden ways of being and acting that limit our freedom to think strategically, Figure 1. Flipping the prevailing model of leadership. In the current prevailing (epistemological) model of leadership, knowing is the anchoring foun- dation of leading effectively. By contrast, the emerging model anchors effective leadership in the leader’s way of being. Said somewhat poe- tically, if you’re not being a leader, it is impossible to act like a leader. innovate, and execute (Souba, 2011a; Souba, 2011b). Once these constraints are revealed, options for leading more natu- rally and intuitively become possible. When we exercise lead- ership as our natural self-expression, we invariably perform at our best (Box 1). In this emerging leadership paradigm, the leader’s knowl- edge and expertise are not the foundation for leadership but they do play an essential role by illuminating and informing the circumstances and challenges he or she is confronted with. This “advising/apprising” role involves a conversation, in a literal sense, in which the situation can “talk back” to the leader. The resultant wisdom is essential to achieving mastery. Becoming a More Effective Leader Every system, including the human operating system, is built to get the results it gets. Moreover, every system has a design limit, which when reached cannot be surpassed unless it un- dergoes transformation. For human beings, reinvention means new ways of being, thinking and acting. Not surprisingly, rein- vention and mastery are tightly linked. All of us, regardless of our talents, must learn to lead our- selves. “Conventional thinking”, writes Lee Thayer, “always and inevitably leads to conventional results” (Thayer, 2004). Slowly but surely we are learning that the process of trans- forming ourselves and our organizations is not just about ac- quiring more knowledge or changing our business strategy but also about exposing the hidden contexts that shape our ways of being and acting and limit our opportunity set for leading our- selves and others more effectively. Change resides in new ways of being, talking, and acting, which are shaped by our underly- ing yet hidden beliefs and assumptions (Souba, 2009). The kind of learning required to shift our worldviews is enormously challenging, but it is essential for effective leadership in health care given the enormous disequilibrium and turbulence in the environment. Leading ourselves begins by discovering who we are. “Be- coming a leader,” writes Warren Bennis, “is synonymous with becoming yourself. It is that simple. It is that difficult” (Bennis, 1994). This may sound like a cliché but if we don’t look at ourselves realistically, we will never learn from our experiences and we won’t be able to crystallize what we truly care about and what we are willing to take a stand for. What it is to be Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 47  W. W. SOUBA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 48 performance is firstly a function of his or her way of being (and acting) with those circumstances. The model stresses the im- portance of shifting certain of our prevailing (yet hidden) con- texts in order to become more effective leaders. human is inextricably linked to the way in which we lead. What gets in the way of (constrains) our being human also gets in the way of our leadership. Leverage the Power of Language The LLPM highlights three key interdependencies. First, our effectiveness as leaders is first and foremost a function of our moment-to-moment, situation-to-situation way of being and acting. Second, our way of being and acting is always consis- tent with (correlated with) the way in which the circumstances we are dealing with occur for us. Since many of the circum- stances (leadership challenges) we are confronted with are in- evitable (e.g., decreasing reimbursement, new payment models, a reduced NIH salary cap), recontextualizing (reframing) them —rather than resisting them—is essential to tackling them. Third, recontextualization is always a linguistically-mediated process. Language provides direct access to the context you bring to the circumstances you’re dealing with and direct access to the way in which those circumstances occur for you. As such, language provides access to the source of your way of being and acting. What is distinctive about the human world is that it is con- stituted in, shaped by, and accessible through language (Souba, 2011a; Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). In other words, access to any phenomenon is granted by language. Language acts as a lens (a context) through which we “see” and understand life’s challenges, other people, and ourselves. More relatedly, the way any leadership challenge occurs for us is through language. Making sense of our leadership challenges and crafting solu- tions is a linguistic process. Alfred Korzybski, a Polish engineer and philosopher, main- tained that our ability to solve complex challenges is limited by the architecture of our brain and the structure of our languages (Korzybski, 2008; Korzybski, 1995; Korzybski, 1990). He wondered why structures built by engineers rarely collapse and, if they do, the underlying defect can be uncovered, whereas social systems (health care systems, economies, governments) not infrequently collapse but the basic defect is often unclear. Korzybski (Korzybski, 1990) drew the following conclusion: Stated slightly differently, the way in which the world, others, and you yourself occur for you is a function the conversation (your listening) that uses you. “We, mankind, are a conversa- tion,” wrote Heidegger. “The being of men is founded in lan- guage. But this becomes actual in conversation” (Heidegger, 1979). This conversation (with yourself and others) is inevita- bly biased by your beliefs, filters, and assumptions, thereby acting as a context (a point of view) that skews your perception and your interpretation. At a young age we begin to acquire an already-always-listening that filters and distorts what we see and hear. Some people listen through a “life is difficult” head- set. They lug this listening around with them to the various challenges that show up in their lives. They are this listening. It is the space inside of which life occurs for them. Hyde (Hyde, 1994) elaborates: What do engineers do neurologically when they build a bridge? … The engineers use a special, perfect yet restricted form of representation called mathematics, similar in structure to the facts they deal with; use of such symbolization yields predictable empirical results. In contrast, architects of social systems employ languages that are often structurally dissimilar to the facts and have dif- ferent meanings for different constituencies. As a consequence, when these systems collapse, the basic structural flaw is diffi- cult to identify. Our leadership challenges are similar. Because every leadership challenge we deal with “dwells” in language, what we need when leadership is called for is a language (a conversational domain) that creates a context that uses us such that we are left being a leader and exercising leadership effec- tively as our natural self-expression (Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Granger, & Dimag- gio, 2010). [E]ach of us at every moment is always already listening in a particular way, listening from… the particular set of values and concerns that constitute our identity. Our way of being and our understanding of the world, given by these values and concerns, constitute the listening that each of us always already is, the listening that determines the way the world occurs for us. I am stressing the importance of language because it is the most powerful and underutilized resource leaders have at their disposal. We all know people who are quite articulate, but, as Denning (Denning, 2008) points out, if people aren’t listening to you, you’re wasting your voice and your time. Changing people’s entrenched thought constructs and behaviors that have been successful for decades often requires a story about the future that engages them. That future, which is only a possibil- ity today, must be appealing enough to produce the necessary The Language Leadership Performance Model (LLPM) de- scribes the relationship between the circumstances the leader is dealing with (the leadership challenge), the context (point of view) the leader brings to that challenge, and the leader’s way of being and actions (the ultimate source of the leader’s per- formance) (Figure 2). In contrast to the popular model of lead- ership, which assumes the leader’s performance is due largely to his or her knowledge, the LLPM proposes that the leader’s Figure 2. The Language Leadership Performance Model (LLPM). The model describes the rela- tionship between the leadership challenge (the circumstances the leader is dealing with), the context the leader brings to that challenge, and the leaders being and acting (the ul- timate source of the leader’s performance). In contrast to the popular model of leader- ship, which presupposes the leader’s performance is due largely to his/her knowledge, the LLPM proposes that the leader’s performance is firstly a function of his/her way of being and acting with those circumstances. The model stresses the role of language in shifting certain of our prevailing (yet hidden) contexts as key to exercising more effec- tive leadership. Adapted from Souba, 2011b.  W. W. SOUBA courage in people to challenge the status quo. And, it must be inspirational enough to unite and align them so that their deci- sions and actions can be coordinated efficiently and effectively. Master leaders use language to prompt cognitive shifts in others, jarring them loose from their entrenched worldviews, so they can recontextualize their leadership challenges in such a way that their naturally correlated ways of being and acting provide them with new opportunity sets (previously unavailable) for exercising exemplary leadership (Souba, 2011b). The House of Leadership Foundation The House of Leadership (HOL), a metaphorical model, pro- vides an anchoring foundation for being a leader and a practical framework for exercising leadership effectively (Figure 3). Laying the foundation of the model involves mastering the four pillars of being a leader. Building the framework entails con- structing for yourself a contextual schema, which when mas- tered becomes a structure (construct) that in any leadership si- tuation gives you the power to lead effectively as your natural self-expression. Being (the foundation) and action (the frame- work) are distinct but inseparable. Both of these activities— laying the foundation and erecting the framework—will require that you deconstruct, at least in part, your existing leadership paradigm. The foundation of the HOL is anchored by four ontological pillars: awareness, commitment, integrity, and authenticity (Souba, 2011a). Awareness refers to mindful presence, which involves bringing your full concentration to the situation at hand and paying attention purposefully, non-judgmentally and with curiosity. A key aspect of awareness is being mindful of the distortions created by your already-always-listening, that pervasive running commentary (inner critic) that’s thinking for you and biasing you. When you are aware of this self-talk, its tendency to “control” you diminishes, opening up possibilities for new ways of being, thinking and acting. Burrell and Morgan (Burrell & Morgan, 1979) explain: In order to understand alternative points of view, it is impor- tant that a [leader] be fully aware of the assumptions upon which his own perspective is based. Such an appreciation in- volves an intellectual journey which takes him outside of the Figure 3. The House of Leadership. The house metaphor provides the leader with a solid foundation for being a leader and a practical framework for exercising leadership effectively. The leader’s know-how and know- what serve to inform the leader in making choices and decisions. realm of his own familiar domain. It requires that he become aware of the boundaries which define his perspective. It re- quires that he journeys into the unexplored. It requires that he become familiar with paradigms which are not his own. Only then can he look back and appreciate in full measure the precise nature of his starting point. For humans (and teams and organizations), integrity has to do with one’s word being whole and complete (Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011; Christensen, 2009). By “keeping your word” we mean doing what you said you would do—keeping your promise. There must be clarity about what one is giving one’s word to, to whom it is being given, and by when the promise given by the word will be completed. Research by Sull (Sull, 2003) suggests that when strategy implementation falters, broken or poorly understood promises are usually the reason. Authenticity means being the accountable author of one’s ac- tions and behaviors (Souba, 2011a). Being authentic is being and acting consistent with who you hold yourself out to be for others (to include who you allow others to hold you to be), and who you hold yourself to be for yourself. To live authentically means to be, regardless of the circumstances and predicaments we find ourselves in, responsible for creating our future—i.e., “cause in the matter” (Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011). As humans, we always find ourselves dealing with something that matters to us in some way; and, in dealing with it, we’re always “being” some way. For example, if I’m being cynical in dealing with medicine’s challenges, the world of health care reform could occur for me as hopeless. While we presume that we, in our day-to-day lives, display (reveal) our way of being, that way of being actually reveals us—who we are, what we stand for. The term commitment means being “committed to something bigger than yourself” such that who you are being and your actions are in service of realizing something beyond your per- sonal concerns for yourself (Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). The future is always the context for the present and a bold, compel- ling future provides you with the resolve and intestinal fortitude (in the present) to deal with whatever breakdown may occur along the way to creating that future. Fulfilling on your com- mitments often creates something to which others can also be committed, and have a sense that their lives are about some- thing bigger than themselves. When people are operating inside these commitments, their tolerance for uncertainty increases, and their enthusiasm, vitality and ingenuity are enhanced. The House of Leadership Framework The four foundational building blocks for “being a leader” support the five-part framework for exercising effective lead- ership: relationality, actionality, symbolicity, temporality, and locality (Figure 3). Leadership isn’t routine (management can be) and in order for the work of leadership to get done, 1) rela- tionships are critical; 2) there must be action; 3) language is essential; 4) it must live in the domain of a created future, and; 5) we must lead “out here” from an as lived perspective rather than “in here” from a set of theories. Relationality conveys that leadership is born out of relational spaces created by building high-powered human interactions. Effective leadership today entails building connections and networked relationships that foster creativity, promote collabo- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 49  W. W. SOUBA ration and enhance resource exchange (Souba, 2007). Using fMRI to record brain activity, Stephens and colleagues (Ste- phens, Silbert & Hasson, 2010) found that during successful communication, speakers’ and listeners’ brains exhibit tempo- rally connected response patterns, a “mind meld” of sorts. This neural coupling abates substantially in the absence of good communication. Actionality—the state of action—is essential for effective leadership. There is no mental state, or thought process that alone effects change—only action does. Interestingly, we tend to judge others by their actions, while we judge ourselves by our intentions. All too often, we let ourselves off the hook if we believe our intentions are good. It is a useful exercise to verify for yourself that, in the absence of an interceding action, the future that unfolds will be one that is largely a continuation of your past. Given the natural correlation between the “occur- ring” and your way of being and acting, without a shift in the way in which your leadership challenge occurs for you, your actions and the results they produce (the future) will be the same. Symbolicity refers to our natural propensity to organize our perceptions and experiences into symbols and symbol systems. Language (spoken and written) is the major medium leaders use to make leadership happen. Language is the vehicle we use for making decisions, resolving most disputes, and conveying pos- sibilities. While language converts events into “talkable” ob- jects, it is inevitably associated with variable meanings and dif- ferent interpretations; thus, “to claim that one’s own viewpoint is “objective”, that is, valid in all contexts, is clearly a misappro- priation of the truth” (Mey, 2003). Things—ideas, conversations, people—become intelligible to human beings through a process of linguistic distinctions. Speaking is less about transmitting words to someone else and more about participating in a “saying” that is a showing. “What unfolds essentially in language is saying as pointing… The saying grants those who belong to it their listening to language and hence their speech… [This saying] lets what is coming to presence shine forth…” (Heidegger, 1971). In using language as a “showing” that clarifies priorities or shows the way, good leaders help themselves and others “see” differently. This property of language, its ability to bring forth, out of the un- spoken realm, new ideas and possibilities, will determine the future of our health care system and our world. Temporality, as used here, does not refer to clock time. Rather, it refers to the fact that you have a future that you are living into. All of your experiences (perceptions, memories, etc.) have a common temporal structure: a reference to past experi- ences, a current openness or clearing to what is present, and an anticipation of the moments of experience that are just about to happen (Gallagher & Zahavi, in press). Humans can also con- ceptualize far into the future. If you look for yourself, you will see that the future is the context for the present. In other words, both what is so in the present, and the possibilities for dealing with what is so, occur for you in the context of the future you are living into (Erhard, Jensen & Granger, 2011). Given the fu- ture-oriented nature of leadership, temporality is why leader- ship can happen in the first place. Locality refers to where leadership happens. Because our brain generates our life experiences, we tend to believe that where we (our ways of being) are “located” is in our brain. For example, if we want to understand someone’s motives, we’ll often say, “I need to get into his head.” It is not surprising that we often identify our brain at the center of who we are and where our “I” resides. But leadership does not happen in your brain. Your brain generates your ways of being and your ac- tions, but leadership happens out here in the world. Carol Stei- ner (Steiner, 2002) explains: Our fundamental nature [is] to be practically rather than theoretically open to the world. To be practically open means to do things with the world, to be active, to be engaged in human pursuits, to be hands on, to get our hands dirty, rather than “liv- ing in our heads”… Interpretation does not happen in our heads. It happens in the world. Martin Heidegger (Heidegger, 1962; Dreyfus, 1991) recog- nized the phenomenological nature of leading “out here” a cen- tury ago when he characterized human being as “being-in-the- world.” Life as lived happens “out-here” in the world. And exemplary leaders lead “out-here” rather than “in-here.” The “in-here” work of thinking, formulating theories, and generat- ing explanations informs their leadership “out-here.” As life is lived, how could we be anywhere else? Anton reminds us that “we are always already in various concrete social relations with the world; never are we in need of first making contact. Hu- mans are always already outside themselves, co-caught-up in various intentional relations and involvements” (Anton, 1999). I am belaboring this point about where life is lived because, as physicians and scientists, we spend much of our time ana- lyzing data, writing grants, and thinking about diagnostic di- lemmas. Such activities are cognitively intense—we have a ten- dency to “be in our heads”, so to speak. We might use familiar expressions such as, “I’ve been racking my brain all day” or “My brain is fried.” Associated with this tendency to “be in our heads” is a listening that opines in the midst of our thinking. It usually shows up for us as a subtle voice that asks questions and makes judgments like: “Do I agree with that? Am I right? I don’t believe that.” Understandably, we may come to believe that who we are is our thoughts, impulses, and urges. Neuroscience allows us to learn about what happens “in- here” (in our brain) but we can’t actually experience our acti- vated neural networks. We can only experience what is gener- ated “in here” out in the world, that is, “out here” where leader- ship and life happen. Parker Palmer (1999) eloquently express- es the importance of the inward journey: Why must we go in and down? Because as we do so, we will meet the darkness that we carry within ourselves—the ultimate source of the shadows that we project onto other people. If we do not understand that the enemy is within, we will find a thou- sand ways of making someone ‘out there’ into the enemy, be- coming leaders who oppress rather than liberate others… Good leadership comes from people who have penetrated their own inner darkness and arrived at the place where we are at one with one another, people who can lead the rest of us to a place of “hidden wholeness” because they have been there and know the way. Creating a New Context Our dilemmas in health care, as vexing and problematic as they are, must be confronted. We can’t, in Barbara Shelly’s words, “go back to the old way, in which the only real guaran- tee of being able to afford health care was to never, ever get sick” (Shelley, 2013). As you take on your leadership chal- lenges, the LLPM and the HOL will provide you with a user’s manual of sorts. These tools are not intended to be rigid pre- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 50  W. W. SOUBA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 51 scriptions since, in practice, leadership in not linear or formu- laic. A heuristic for leading yourself (Table 1) can also be a useful guide as you take on this work. Recontextualization is a process that extracts content from its original context and embeds it into a new context. This refra- ming process, which is always a linguistically-mediated event, entails a change of meaning—in other words, a change in the way in which your leadership challenge occurs for you. How- ever, before you can create a new context, you must first “un- conceal” your prevailing context. Exposing your reigning (hid- den) context(s) involves identifying your unexamined beliefs, taken-for-granted assumptions, and already always listening relative to what it is to be a leader and what it is to exercise effective leadership so as to free yourself from the confines imposed by them (Souba, 2010; Souba, 2011a; Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). When your contexts become revealed, you will begin to see the inadvertent process by which they were created and the degree to which they govern your leadership decisions. You will discover that you have a choice about who you can be, independent from these contexts. Master leaders use language to recontextualize their leader- ship challenges so that their naturally correlated ways of being and acting can emerge, resulting in effective leadership. When leaders linguistically unveil limiting contexts, they can create new contexts that shift the way leadership challenges occur for them. This is step one in providing you access to a wider range of ways of being and acting. Creating for oneself a new context is often one of the most challenging aspects of becoming an extraordinary leader. Our obsolete mental maps, which frequently worked in the past, are exceedingly difficult to revise. John Kenneth Galbraith (Gal- braith, 1971) reminds us that “faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving there’s no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.” Much as a scientist must think methodically to gain insights into her research ques- tions, you must apply rigorous thinking to the puzzle called “you and your leadership.” But these insights aren’t acquired by measuring or assaying; they are acquired first-hand as an as- lived experience, through rigorous, disciplined thinking. Many people think they are thinking when they are simply reshuffling their biases. We need a higher quality of thinking from more people in order to transform our health care system. Heidegger (Heidegger, 1966) pulls no punches when he writes: Table 1. A heuristic for leading yourself. Step Distinction/Comment 1 Identify a leadership challenge you are dealing with where you’ve been ineffective (unproductive) in getting the results you desire. A leadership challenge exists when you are not realizing the outcome you want for the circumstances you’re dealing with and, without some intervention (a different approach or set of tactics), the same unwanted outcome will persist. 2 How does your leadership challenge occur for you and how do you occur for yourself in dealing with it? Include what it is that’s not working for you as well as your complaints. The term “occur” refers to the way in which “what you are dealing with” (the occurring) is present (shows up) in some way for you (e.g., frustrating, unfair, difficult, hopeless) and the way in which you occur for yourself in dealing with it (e.g., confident, incompetent, awkward) 3 What unproductive (limiting) ways of being and what actions (behaviors) are contributing to your ineffectiveness (underperformance) and hindering you from leading as your natural self-expression? Your effectiveness as a leader is a function of your ways of being and your actions (or inactions). You must “unconceal” these limiting ways of being and acting that constrain your freedom to lead effectively as your natural self-expression. What gets in the way of your natural self-expression are the encumbering ways you wound up being. 4 Verify for yourself that, in the absence of an interceding action, the future that unfolds will be one that is largely a continuation of the past. Given the natural correlation between the “occurring” and your way of being and acting, without a shift in the way in which your leadership challenge occurs for you, your actions and the results they produce (the future) will be the same. 5 Listen to your leadership challenge. Describe the conversation that is using you? How does it shape the way in which your leadership challenge occurs for you? Who you are being moment to moment is a function of your listening. Each of us is a listening (a conversation with ourselves) that “uses us” by providing us with a point of view (a context) from which we make sense of our circumstances and orient our actions. 6 Separate the facts you are dealing with in your leadership challenge from your “languaging” (interpretation, explanation, narrative) of the facts. When you’re able to separate the facts (e.g., my budget got cut) from your interpretation (that’s not fair, it can’t be balanced), you’ll discover that much of what you believed to be the case was just your story. What you thought was unalterable now becomes open to change. 7 What intuitive and spontaneous ways of being and acting (i.e., those that are a manifestation of your natural self- expression) would grant you the performance and results you desire (that is, enable you to deal effectively with your leadership challenge)? Take into consideration universal, all-purpose ways of being and acting that would leave you more effective (e.g., optimistic, respectful, curious) as well as more distinctive cognitive and emotional states and actions (e.g., vigilant, analytical, pragmatic, setting expectations). Recall that the source of your “as lived” performance is most fundamentally a product of your way of being, and your matched actions. 8 In what way(s) would your leadership challenge have to occur for you and how would you have to occur for yourself so that your naturally self-expressed ways of being and acting would intuitively arise? In order to access your leadership challenge so that it occurs for you as hittable rather than unhittable, you must reframe (recontextualize) it. Recall that the way you choose to speak to and listen to yourself and to others (i.e., your language) about the challenge you are dealing with shapes and colors the way those challenges occur for you. 9 What can you say (to yourself and others) about the future you are committed to such that your stand for that future will grant you the being and acting in the present required to take on your leadership challenge and the obstacles you will encounter along the way? In committing to a future that is bigger than you are, the realization of which fulfills on what is important to you and what you truly care about, you will “re-wire” neural networks in your brain in such a way that they generate the correlated ways of being and acting necessary to realize that future as your natural self-expression. Such a potent relationship with language will give you the power to speak the future you are committed to into existence.  W. W. SOUBA Let us not fool ourselves. All of us, including those who think professionally, as it were, are often enough thought poor; we all are far too easily thought-less… Man today is in flight from thinking. This flight from thought is the ground of thoughtlessness… Part of this flight is that man will neither see nor admit it. Man today will even flatly deny this flight from thinking… For the way to what is near is always the longest and thus the hardest for us humans. This is the way of medita- tive thinking. Meditative [reflective] thinking demands of us not to cling one-sidedly to a single idea, nor to run down a one- track course of ideas. [Reflection] demands of us that we en- gage ourselves with what at first sight does not go together at all. Each of us experiences the world through the lenses of our accrued contexts, which arise in, reside in and are continuously molded by language. Language is and has been a powerful sculp- tor of who we are today. It is within this context that opportuni- ties for transformational change reside. Using our willpower to strip away the various levels of context so people can discover other possibilities for their relationships, commitments, and ac- tions is a critical leadership responsibility (Malpas, 2002). While neuroscientists such as Sam Harris insist that free will is an illusion, Harris (Harris, 2012) acknowledges that it has actu- ally increased his feelings of freedom. A creative change of inputs to the system—learning new skills, forming new relationships, adopting new habits of atten- tion—may radically transform one’s life… Getting behind our conscious thoughts and feelings can allow us to steer a more intelligent course through our lives. On the other hand, cognitive psychologist and neuroscientist Peter Tse accepts that while we are not free to change the way we are at any moment, we can, through a process he calls dy- namical synaptic reweighting, change mental events in the fu- ture. Tse (Tse, 2013) writes: Physically realized mental events can change the physical basis not of themselves in the present, but of future mental events. How? By triggering changes in the physically realized informational/physical criteria for firing that must be met by future neuronal inputs before future neuronal firing occurs that realizes future mental events. Such criterial causation does not involve self-causation. Your connectome changes in response to changes in your thoughts, speech and behaviors. The words that come out of your mouth matter, a lot. But before you can create a new con- text that “liberates” your (naturally self-expressed) ways of be- ing and acting, you must expose your prevailing context(s) and limiting ways of being and acting that handicap your perform- ance. This is no cakewalk as our entrenched ways of being and acting are invariably frozen solid and exceedingly difficult to thaw. In order to unfreeze them, there must be a compelling reason to change. There must be something you are willing to take a stand for. For example, the associate dean leading a ra- dical curriculum reform initiative must shift his context from, “The faculty will never buy into this” to “We’re going to design a curriculum that sets the standard for preparing physician- leaders.” In committing to a future bigger than you are (a future that surpasses than your own agenda), the realization of which ful- fills on what is important to you and what you truly care about, you will change your connectome such that its re-wired neural networks will generate the correlated ways of being and acting necessary to realize that future as your natural self-expression. Such a potent relationship with language gives you the power to speak the future you are committed to into existence. It begs the question: What can you say about the future you’re commit- ted to such that it will grant you the being and acting required to take on your leadership challenge and the obstacles you will encounter along the way? Who are You Really Nobel Laureate Saul Bellows (Bellows, 1976) reminds us that, as human beings, we are confronted with “an immense, painful longing for a broader, more flexible, fuller, more co- herent, more comprehensive account of what we human beings are, who we are, and what this life is for.” Our understanding of what it is to be a leader is inseparable from our understanding of what it is to be human. Most of us “see” ourselves and others as objects with proper- ties, titles, abilities, possessions, which can be measured (Table 2). Most humans are concerned with six properties (attributes) known as the 6 As (our 6 Achilles’ heels): admiration, achieve- ment, attention, authority, appearance, and affluence (Souba, 2011b). They are the primary indicators of looking good and measuring up in our culture. How we understand ourselves is the foundation of our values, our choices, and our relationships with each other. A context that understands human beings as objects with properties is shallow and limiting. What we lose is our awe that the world actually exists, that we exist (Heidegger, 1962). To be human is to be amazed by “being” and to be grateful for the privilege of being alive. Ratcliffe (2013) writes: Not knowing everything about a person is integral to our sense of her as a person. The reason for this is that persons are not merely experienced as objects within one’s world, a sense of their being persons involves an appreciation of their potential to reshape one’s world, to transform to varying degrees the pos- sibilities it offers. What makes us uniquely human, then, is not our insulated knowledge, but our fundamental concern or care about our condition (Heidegger, 1962). Human beings are those beings for whom their being matters. Care (as used here) does not mean attending to one’s needs or wants; rather, it is the require- ment we each have to choose, to take a stand, to make a com- mitment. Moment by moment we can choose how to “be” as we deal with life’s challenges. Yet, choosing authentically is a co- nundrum because we are “thrown” into a world that we do not choose, one that often seems indifferent to our concerns. A different way of understanding who we are most funda- mentally as human beings is as a “clearing” of conscious intel- ligibility in which we can choose the way in which the world shows up for us (Heidegger, 1962). As expressed below, this is a captivating metaphor. In the midst of beings as a whole an open place occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting... Only this clearing grants and guaran- tees to us humans a passage to those beings that we ourselves are not, and access to the being that we ourselves are (Heideg- ger, 1971). The clearing is at once both a physical space (similar to a glade in a forest) and a field of consciousness (Edgeworth, 2003). In one sense we are the clearing. In another sense, the clearing is the space where our being emerges, where we be- come aware and intentional and where other entities emerge out of hiddenness. While this metaphor might imply that the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 52  W. W. SOUBA Table 2. Who are we? What does it mean to be human? Prevailing Understanding An Object with Properties Emerging Understanding A Clearing of Intelligibility ● We live (talk, act) as if we’re objects with measurable properties. We tend to define people based on their properties (job, title, income) ● Human beings are drawn to six properties known as the 6As (our 6 Achilles’ heels) ● Admiration; achievement; affluence; attention; authority; appearance ● This way of understanding who we are, as objects with properties, promotes unproductive ways of being and acting ● Inauthenticity; out of integrity; poor self-awareness; self-absorbed (committed only to one’s personal agenda) ● Human beings are a clearing of conscious intelligibility in which the world shows up for us. In this clearing, our way of being and acting match the way in which the world occurs for us. “Things show up in the light of our understanding of being” (Dreyfus, 1991). ● We dwell in already made clearings that have become littered with outdated, confining ways of being, thinking and working. The “clearing out” of these outdated mental maps occurs via distinctions, which always live in language. ● The disclosure of the authentic self is always accomplished as a clearing-away of our concealments (our hidden biases and assumptions). process of leading yourself is a passive or undemanding one, it is not. The breakthroughs in thinking that ensue from the in- ward journey of leadership are frequently “torn out of hidden- ness” (Heidegger, 1962) such that we experience the “essential unfolding as the destining of a revealing” (Soccio, 2007). In- sights often do emerge out of obscurity into the light. And it is through wrestling with them as they emerge—with all of their discord and defiance—that transformation is born (Box 2). No- where is this need for transformation greater than in health care. The disclosure of the authentic self is always accomplished as a clearing-away of these concealments, which leads to a clearing for action that is an “emergent bounded aggregate of ways of being and acting that become possible through lan- guage” (Crevani, 2011). Language allows us to be astonished by Being (Heidegger, 1979). Once we become truly amazed by “being” we cannot help but be grateful for the privilege of ex- periencing the world with a continual sense of appreciation and wonder. Given this context, we must each ask: In the clearing that I am, what ways of being and what behaviors will create the requisite leadership that will ensure a bright future for health care? In his Magnum opus, The Master and his Emissary, Iain McGilchrist (McGilchrist, 2012) argues that the left hemisphere of the human brain, which thinks in classes and categories, has slowly come to dominate the right hemisphere, which provides us with meaning and has “ontological supremacy.” This domi- nance has resulted in bureaucratization, fragmentation, exces- sively rigid thinking, and an unhealthy focus on metrics such that “we’re in danger of forgetting everything that makes us human.” McGilchrist contends that left brain’s emphasis on represen- tational language developed because of its practical utility but at the expense of context and awareness of the inherent. We must reengage the right brain in the health care reform conver- sation. The solution is not just a question of better integrating the two hemispheres. The right brain is both the gatekeeper and the conciliator, an especially important role when it comes to tackling leadership challenges. Without this wisdom, our com- plex challenges will continue to plague us. Acknowledgements The author thanks Meredith Bartelstein, Kathi Becker, James Borchert, Joe DiMaggio, Werner Erhard, Faith Goodness, Kari Granger, Aaron Grober, Deborah Hastings, Michael Jensen, Pam Gile, Cathy Pipas, Glenda Shoop, Fran Todd, Mary Turco, and Craig Westling and for their helpful conversations and insights. REFERENCES Anton, C. (1999). Beyond the constitutive-representational dichotomy: The phenomenological notion of intentionality. Communication The- ory, 9, 26-57. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1999.tb00161.x Atkinson, B., Atkinson, L., Kutz, P., Lata, J., Lata, K., Szekely, J., & Weiss, P. (2005). Rewiring neural states in couples therapy: Advanc- es from affective neuroscience. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 24, 3-13. doi:10.1521/jsyt.2005.24.3.3 Barker, R. (1997). How can we train leaders if we do not know what leadership is? Human Relations, 50, 343-362. doi:10.1177/001872679705000402 Bennis, W. (1994). On becoming a leader. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. Bickerton, D. (1996). Language and human behavior. Seattle, Wash: University of Washington Press. Block, P. (1996). Stewardship. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publish- ers. Bluck, S., & Habermas, T. (2001). Extending the study of autobiogra- phical memory: Thinking back about life across the life span. Review of General Psychology, 5, 135-147. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.135 Boje, D., Oswick, C. and Ford, J. (2004). Language and organization: The doing of discourse. Academy of Management Review, 29, 571- 577. Brownlee, S. (1996). The biology of soul murder: Fear can harm a child’s brain. Is it reversible? US News and World Report. Buonomano, D., & Merzenich, M. (1998). Cortical plasticity: From sy- napses to maps. Annual Reviews of Neurosc ience , 21, 149-186. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149 Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organi- zational analysis: Elements of the sociology of corporate life. Lon- don: Heinemann. Christensen, K. (2009). Integrity: Without it nothing works. Interview with Michael Jensen. Rotman: The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management, 99, 16-20. Crevani, L. (2011). Clearing for action: Leadersh i p as a re la t io na l p he - nomenon. Doctoral Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:414603 Denning, S. (2008). The secret language of leadership. Leader to Lea- der, 48, 14-19. doi:10.1002/ltl.275 Dreyfus, H. (1991). Being-in-the-world: Commentary on Heidegger’s being and time. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Edgeworth, M. (2003). The clearing: Heidegger and excavation. Posted on archeolog. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 53  W. W. SOUBA http://traumwerk.stanford.edu/archaeolog/2006/09/the_clearing_heid egger_and_exc_1.html Erhard, W., Jensen, M., & Granger, K. (2011). Creating leaders: An on- tological/phenomenological model. In S. Snook, N. Nohria, & R. Khurana (Eds.), The handbook for teaching leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Erhard, W., Jensen, M., Zaffron, S., & Granger, K. (2011). Course ma- terials for being a leader and the effective exercise of leadership: An ontological/phenomenological model (May 10, 2011). Harvard Bu- siness School NOM Working Paper No. 09-038. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1263835 Erhard, W., Jensen, M., Granger, K., & Dimaggio, J. (2010). Mastering the principles and effective delivery of “the ontological leadership course. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1638429 Eriksen, M. (2008). Leading adaptive organizational change: Self-refle- xivity and self-transformation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 21, 622-640. doi:10.1108/09534810810903252 Galbraith, J. (1971). Economics, peace and laughter. New York: New American Library. Harris, S. (2012). Free will. New York: Free Press. Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (in press). Primal impression and enactive perception. In D. Lloyd, & V. Arstila (Eds.), Subjective time: The philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of temporality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Gilbert, D., & Wilson, T. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317, 1351-1354. doi:10.1126/science.1144161 Goss, T. (1995). The last word on power. New York: Crown Publish- ing. Green, J. (2006). An abundance of katherines. New York: Dutton Juve- nile. Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time. New York: Harper & Row. Heidegger, M. (1966). Discourse on thinking. New York: Harper and Row. Heidegger, M. (1971a). Poetry, language and thought. New York: Har- per & Row. Heidegger, M. (1971b). On the way to language. New York: Harper and Row. Heidegger, M. (1979). Holderlin and the essence of poetry. Existence and being. Regnery/Gateway: South Bend, Ind. Hyde, R. (1994). Listening authentically: A heideggerian perspective on interpersonal communication. In K. Carter, & M. Presnell (Eds.), Interpretive approaches to interpersonal communication. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Kolb, B., Gibb, R., & Robinson, T. (1995). Brain plasticity and behav- ior. Eat Sussex: Psychology Press. Korzybski, A. (2008). Manhood of humanity: The science and art of human engineering. Gloucester: Dodo Press. Korzybski, A. (1995). Science and sanity: An introduction to non-Ari- stotelian systems and general semantics. Englewood, NJ: The In- stitute of General Semantics. Korzybski, A. (1990). Collected writings 1920-1950. Englewood, NJ: The Institute of General Semantics. LeDoux, J. (2003). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. New York: Penguin Books. Malpas, J. (2002) The weave of meaning: Holism and contextuality. Language & Communication, 22, 403-419. doi:10.1016/S0271-5309(02)00017-4 McGilchrist, I. (2012). The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the western world. New Haven, CT: Yale Univer- sity Press. Mey, J. (2003). Context and (dis)ambiguity: A pragmatic view. Journal of Pragmatics, 35, 331-347. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00139-X Miller, A. (2008). The drama of the gifted child: The search for the true self. New York: Basic Books. Noë, A. (2009). Out of our heads. New York: Hill and Wang. Palmer, P. (1999). Let y o ur life speak. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Parikh, J. (2012). The zen of management maintenance: Leadership starts with self-discovery. http://hbswk.hbs.edu/archive/4790.html Pascual-Leone, A., Amedi, A., Fregni, F., & Merabet, L. (2005). The plastic human brain cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, 377- 401. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216 Plato, A. (1988). Plato’s portrait of sokrates. Guilford, CT: J Norton. Seung, S. (2012). Connectome. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Shaw, G. (2011). Famous-quotes.com. http://www.1-famous-quotes.com/quote/5826 Shelly, B. (2013). Passive resistance to Obamacare. http://www.jsonline.com/news/opinion/shelly01-mv9p1oe-20547571 1.html Soccio, T. (2007). Archetypes of wisdom: An introduction to philoso- phy. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Souba, C. (2009). Leading again for the first time. Journal of Surgical Research, 157, 139-153. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2009.09.018 Souba, W. (2010). The language of leadership. Academic Medicine, 85, 1609-1618. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ee0045 Souba, W. (2011a). The being of leadership. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 6, 5. doi:10.1186/1747-5341-6-5 Souba, W. (2011b). A new model of leadership performance in health care. Academic Medicine, 86, 1241-1252. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c0385 Souba, W. (2006). The inward journey of leadership. Journal of Surgi- cal Research, 131, 159-167. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2006.01.022 Souba, W., & McFadden, D. (2008). The double whammy of change. Journal of Surgical R esearch, 151, 1-5. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2008.11.808 Souba, W. (2007) The leadership dilemma. Journal of Surgical Re- search, 138, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.01.003 Staudinger, U. (1999). Social cognition and a psychological approach to an art of life. In F. Blanchard-Fields, & T. Hess (Eds.), Social cognition, adult development a n d a g ing. New York: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012345260-3/50016-1 Steiner, C. (2002). The technicity paradigm and scientism in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR7-2/steiner.html Stephens, G., Silbert, L., & Hasson, U. (2010). Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 14425-14430. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008662107 Sull, D. (2003). Managing by commitments. Harvard Business Review, 81, 82-91. Bellows, S. (2013). Nobel laureate lecture. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1976/bell ow-lecture.html Ratcliffe, M. (2013). The structure of interpersonal experience. In D. Moran, & R. Jensen (Eds.), Phenomenology of Embodied Sub- jectivity. Dordrecht: Springer (forthcoming 2013). Teicher, M. (2002). Scars that won’t heal: The neurobiology of child abuse. Scientific American, 286, 68-75. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0302-68 Thayer, L. (2004). Leadership: Thinking, being, doing. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corporation. Tse, P. (2013). The neural basis of free will: Criterial causation. Cam- bridge, MA: MIT Press. Watts, R. (2011). Fables of fortune. Austin, TX: Emerald Book Co. Wind, Y., & Crook, C. (2006) The power of impossible thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton Publishing. Zaccaro, S., Kemp, C., & Bader, P. (2004) Leader traits and attributes. In J, Antonakis, A, Cianciolo, & R Sternberg (Eds.), The Nature of Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 54  W. W. SOUBA Box 1. Your Natural Self-Expression Imagine what it would be like if you met (for the first time) your greatest hero and you didn’t have to figure out in your head how to “be” with that person. You didn’t have to concern yourself with impressing that person or winning him or her over or looking good as you became acquainted. In other words, the “you” that showed up was your natural, spontaneous and inherent way of being and acting. Your natural self-expression was just there. By “natural self-expression” we mean that way of being and acting that is an intuitive and effortless response to whatever set of circumstances one is dealing with (Souba, 2011b). Suppose you weren’t limited to those automatic, ineffective ways of being that often show up when you’re confronted with a difficult challenge such as a budget shortfall or poor per- former? What if you weren’t stuck with your kneejerk predis- position to raising your voice, making excuses, blaming others, or disengaging when the going gets tough? What if you had access to a much wider range of possible ways of being and acting rather than being confined to those default ways of being that have become so engrained yet are so unhelpful and unpro- ductive? What if your natural self-expression prevailed regard- less of what was thrown at you in life? What if you were free to just “be” at any and all times with no limitations? What would it be like to always have access to your best self, leading as your natural self-expression rather than from some compen- dium of theories or concepts? In dealing with any leadership situation, what if that thing (voice) that was already always there watching you, judging you, keeping score wasn’t there? What if that “I”, your iden- tity, that you think defines you wasn’t there either? What would it be like to experience life inside a context such that you were always fully present to life and your natural self-expression was one of being fully engaged with whatever you were dealing with, to include the disappointments, and the defeats? Your effectiveness (performance) as a leader is largely a function of your ways of being and your actions (or inactions) (Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, & Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jen- sen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). In order to gain access to lead- ing as your natural self-expression, you must first expose your engrained beliefs and worldviews about leadership (e.g., I have to look good; If I fail, I’ll look incompetent; I have to be in charge) that are holding you back. This will allow you to loosen up those limiting (and often hidden) ways of being and acting that have become your automatic go-to winning formulas (e.g., micromanaging, avoiding tough conversations, blaming others) that actually constrain your freedom to lead effectively. When Michelangelo was asked how he went about creating his masterpiece David out of a massive block of marble, he said, “David was inside the rock all along. My only job was to re- move the unnecessary rock from around him so he could es- cape.” (Watts, 2011). In a sense, Michelangelo removed the barriers to the marble’s natural expression of itself. Similarly, what gets in the way of our natural self-expression is the en- cumbering ways we wound up being. When we relax their hold on us, we make room to create a new context (a new, wider leadership lens) that has the power in any leadership situation to shape the circumstances we’re dealing with such that our way of being and acting will be consistent with being a leader and exercising leadership effectively (Souba, 2011b; Erhard, Jensen, Granger, 2011; Erhard, Jensen, Zaffron, & Granger, 2011). & Box 2. Moth or Chameleon Leadership In the first half of the 19th century, England transitioned from an agricultural economy to an industrial one. Prior to this, light- colored moths were able to blend in with light-colored bark and tree lichens, while the less common black moth, unable to dis- guise itself, was more likely to be eaten by birds. When the London countryside became inundated with emissions from new coal-burning factories, the lichens died and the trees became black from soot and grime. This provided protection to dark- colored moths while the lighter-colored moths (which had lost their survival advantage) were easy targets for birds and even- tually died off. This kind of directional natural selection, in re- sponse to changing conditions, highlights the plight of the aca- demic medical center that is unable to change. In contrast to moths, the dwarf chameleon uses its real-time color changing abilities to camouflage and protect itself. De- pending on the environmental circumstances the chameleon is dealing with, it is able to change its color palette in millisec- onds to acclimatize to temperature changes, adapt to stress, and avoid predators. Said somewhat metaphorically, the chameleon is able to alter its way of being such that its natural self-expres- sion matches the circumstances it is dealing with. When dealing with change, defaulting to our familiar, auto- matic ways of being and behaving that have worked in the past is a natural human tendency. If the solutions to the problems that confront us were straightforward, standard operating proce- dures might be enough. Increasingly, however, we are con- fronted in health care with challenges that are unanticipated, unfamiliar, and complex. In this kind of environment, leaders must have access to a much broader, more imaginative range of ways of leading. Humans do not have camouflage faculties but we do have language. Whereas biologic evolution was the sole determinant of change for eons, the introduction of language changed the possibilities. Language overcomes the protracted and limited al- ternatives that evolution makes available; it “is exactly what enables us to change our behavior, or invent vast ranges of new behavior, practically overnight, with no concomitant genetic changes” (Bickerton, 1996). Boje and colleagues (Boje, Oswick & Ford, 2004) stress that “language is… a way to recontextualize content. We do not just report and describe with language; we also create with it. And what we create in language “uses us” in that it provides a point of view (a context) within which we “know” reality and orient our actions.” In other words, the way you choose to speak to and listen to yourself and to others about the leadership chal- lenge you’re dealing with shapes and colors the way in which it occurs for you. When language brings about a revision in our worldview, context or thinking, the way in which our circum- stances or problems occur for us invariably shift. When this happens, it opens the door to new thinking constructs, new at- titudes, and new ways of working together. Master leaders use language to recontextualize their leadership challenges in such a way that their naturally correlated ways of being and acting provide them with new opportunity sets for exercising leader- ship as their natural self-expression. Indeed, it is this very pro- perty of language, its ability to change our thinking to modify behavior, which will determine the kind of health care system that we will create. Are you a moth leader with a fixed way of being or a chame- leon leader who’s not stuck with a single way of being and cting? a Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 55

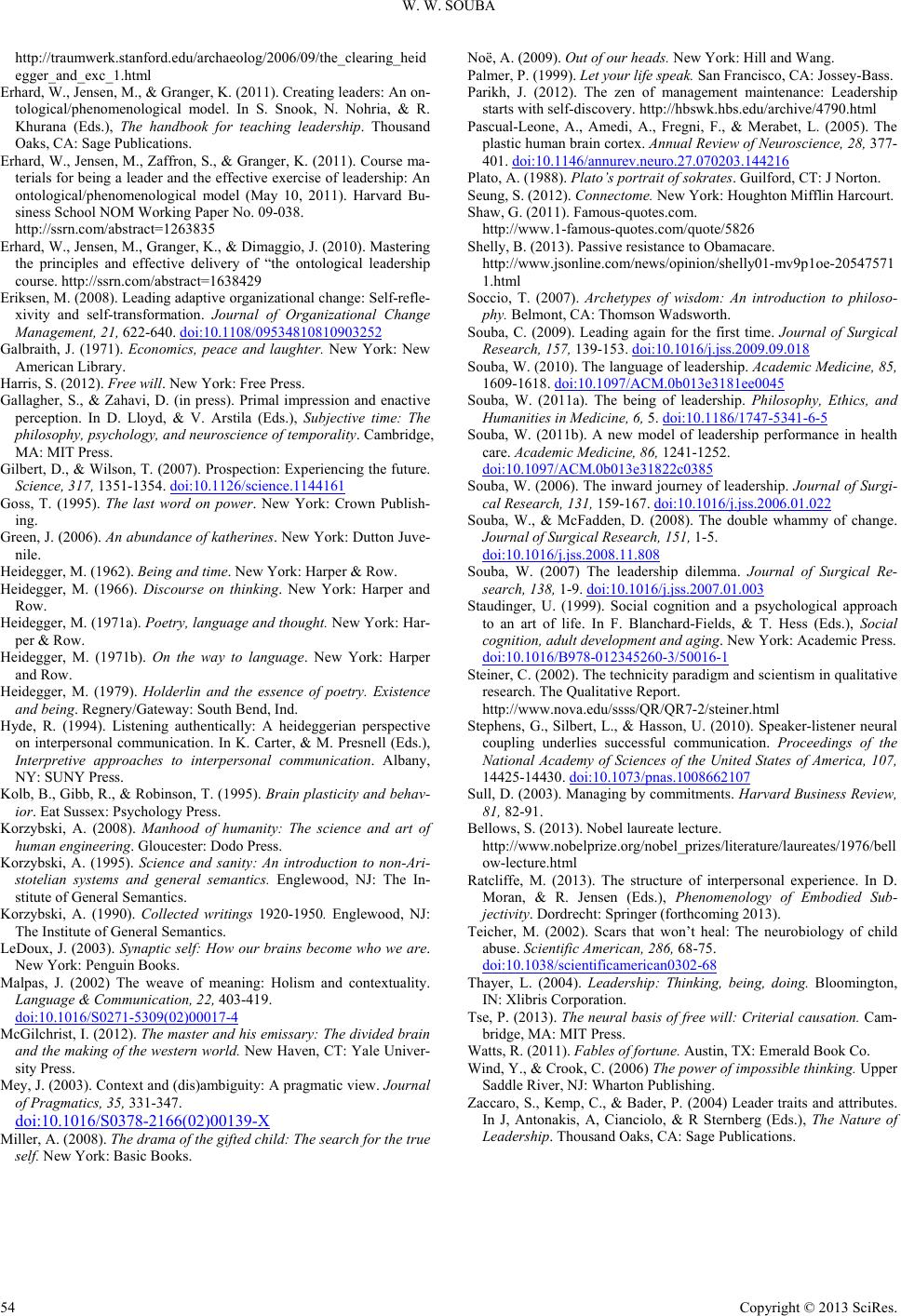

|