Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.7, 592-606 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.47085 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 592 Development and Validation of a Mental Wellbeing Scale in Singapore Chan Mei Fen1, Isnis Isa1, Chang Weining Chu2, Chew Ling1, Sng Yan Ling1 1Health Promotion Board, Singapore City, Singapore 2Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, Singapore City, Singapore Email: mohamad_isnis_isa@hpb.gov.sg Received April 12th, 2013; revised May 14th, 2013; accepted June 13th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Chan Mei Fen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. With a total number of 3400 participants, a sequence of four studies in two waves of data collection, the present study identified the conceptualization and construction of a mental wellbeing scale in a modern Asian multi-ethnic community-Singapore. Study 1 consisted a series of interviews (N = 351), surveys (N = 161) and focus group discussions (N = 59) to examine the popular conceptualization and manifestation of the construct of mental wellbeing in Singapore. The multi-ethnic inputs were then categorized into popular categories to construct a prototype of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing (SMWEB) Scale. With a nationally representative sample of 741 participants, Study 2 found the internal reliability (α = .962, 30 items) and a strong construct validity of the SMWEB. EFA and CFA confirmed a five dimensional struc- ture of the SMWEB: Asian Self-esteem, Social Intelligence, Emotional Intelligence, Resilience and Cog- nitive Efficacy. Each dimension is internally coherent and culturally meaningful. With an additional na- tionally representative sample of 2091 participants, Study 3 constructed a short form of the SMWEB, the SMWEB-S with high internal reliability (α = .932, 16 items) and strong construct validity. Using Sample 2 and the SMWEB-S, Study 4 further validated the SMWEB as a measure of mental wellbeing by testing two theoretical models: the multi-dimensional model of mental wellbeing and the two factor model of mental wellbeing versus mental disorders. Excellent fit indices were found with both models. Further, the SMWEB-S showed significant construct validity by significantly predicting the culturally sanctioned goal pursuits: personal income and education attainment. Keywords: Mental Wellbeing; Psychological Wellbeing Introduction Definition o f M ental Wellbein g a nd Its Assessm e nt The concept of mental wellbeing has experienced a rapid re- vival (Hefferon, & Boniwell, 2011; Kaneman, Diener, & Schwartz, 1999; Seligman, 2002). The evolutionary change of the definition (Bradburn, 1969; Keyes, 2005; Ryff, 1989, Ryff, & Singer, 1998) and measurement ( Diener, Wirtz, Tov et al., 2009; Ryff, 1989) is evident in the official definitions of health and mental health in international and national health service agencies (see for instance, US Department of Health and Hu- man Services/USDHSS, 1999; World Health Organization, 2007). World Health Organization (WHO) (2007, 2010) defines mental health no longer as the state of being free from mental illness (WHO, 1948) but as that which enable the individual to live her life to its fullest (Keyes & Annas, 2009), to actualize one’s growth potential (Vitterso, 2004) and to experience hap- piness and satisfaction along the way (Kaneman, Diener, & Schwartz, 1999, Keyes, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Seligman, 2002). Furthermore, mental wellbeing is now understood as an integral process in its own right, independent of mental illness (Bradburn, 1969; Jahoda, 1958; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Mental wellbeing is more than happiness (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Singer, 1989); it involves the concept of growth towards optimal de- velopment (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Waterman, 1993)—flourishing (Keyes & Haidt, 2002; Keyes & Annas, 2009) and resilience- thriving even in times of difficulty (Block J. H. & Block J., 1980; Carver, 1998; Hefferson & Boniwell, 2011). Healthy functioning of the individual (Valliant, 2000) in dif- ferent cultural contexts might be expressed in the ways that are considered most conducive for optimal development for most members in the population (Bryant & Veroff, 1982; Campfield, 2006). These beliefs and expectations of optimal development are defined by the world views and values (Christopher, 1999) prevalent in the cultural community (Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976; Ryff & Singer, 1989). It follows that in differ- ent cultural communities; there might be a different set of ex- pected attitudes and behaviors of living that defines healthy functions and happiness (Christopher, 1999; Suh & Diener, 2002; Tov & Diener, 2009). Assessment of mental wellbeing of the population in any cultural community needs to take into consideration its cultural expectations and using instruments constructed on the normative expectations of the community (Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick et al., 2007; Mental Health Ireland, 2008, USDHSS, 1999). Mental wellbeing has been seen as a worldwide concern (WHO, 2007) as evidenced in the increasing interest in various countries to promote mental health of its citizenry (Mental  C. M. FEN ET AL. Health Ireland, 2008; Diner, Wirtz, Tov et al., 2010; Tennant, Hiller, Fishwick et al., 2007). Countries where the predominant cultures differ significantly from those in countries where the assessment tools originated need to develop their own assess- ment tools based on the popular conception and manifestations of healthy mental functioning. The present article reports the development and validation of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (SMWEB) in a multi- ethnic but predominantly Chinese (74% of the general popula- tion; 13 % Malays, 9.2 % of Indians and around 3% others; Singapore Census Bureau, 2010) modern industrialized city- state of Singapore (Department of Statistics, Singapore, 2010). Four studies are reported in the present article: Study 1 iden- tified the conceptualization and manifestations of mental well- being in Singapore to form a prototype of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (SMWEB). Study 2 using a nationally repre- sentative r sample (N = 741) to validate the SMWEB by iden- tifying its internal structure and its construct validity (Cronbach & Meel, 1955). Study 3 constructed a short form of the SMWEB (SMWEB-S) with items selected to maintain its in- ternal structure and meaningful dimensions for use in popula- tion level surveys. With a larger nationally representative sam- ple (N = 2091), Study 4 further conducted convergent and dis- criminant validation (Campbell & Fiske, 1959) of the SMWEB- S by differentiating it from mental illness symptoms assessed by the depression and anxiety symptoms of the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg & Williams, 1988) and by confirming its validity with the concurrent measure of World Health Or- ganization’s Mental Wellbeing measure (WHO, 2010). Study 4 further identified the SMWEB-S’ concurrent validity on the common goals pursued by Singaporeans, education attainment and personal income. Study 1: Conceptualization and Manifestation of Mental Wellbeing in Singapore This study consisted of several phases, with sequential use of in-depth interviews, surveys and focus group discussions to identify the conceptualization and manifestations of the concept of mental wellbeing in Singapore (Bowling, Gabriel, Dykes et al., 2003). We then used the resulting item pool to construct a prototype of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (SMWEB). Phase 1: In-depth interview to identify conceptualization and manifestation of mental wellbeing. Participants: 351 respondents, 142 male and 226 female Singaporeans, age ranged from 15 to 56 (Mean 22.9, sd = 5.9). Participants were selected randomly at various places in Singapore such as res- taurants, university and polytechnic canteens and classes, com- munity clubs, libraries, as well as through personal contacts. All participants were Asians and 91% of them were Chinese, the rest were Indians (3%) and Malays (6%). Procedure: Participants were presented the following open-ended ques- tions and were encouraged to give as many responses and as freely as possible: When you think of “wellbeing”, what are the feelings or thoughts that come to your mind? What do you think mental health is? “What do you see in a person that led you to think that he/she is mentally healthy?” Results & Data Analysis: The content of their responses were coded for mental health related statements by two Singaporean Chinese psychology graduates. The statements were then classified into larger cate- gories for coding. Reliability between the two coders was Cohen’s (1960) Kappa = .87. Test Construction: The qualitative responses obtained from the interview results were then examined and selected to be included into the proto- type wellbeing scale with the following selection criteria: 1) The top 30 items with the highest frequency among the responses. Thirty is a number selected because from our past experiences for constructing instrument for large scale screen- ing, respondents lose interest and concentration once the in- strument is longer than 30. Furthermore, 30 is the number of elements in a data set that is required for using parametric sta- tistics. 2) Those that fell around the borderline of the top thirty were carefully evaluated in terms of their cultural relevance and lit- erature support. Thirty items were selected into the prototype scale. Review- ing the thirty items, the researchers were satisfied with their meaning and cultural relevance. The selected items were used to construct a prototype scale of the Singapore Mental Wellbe- ing Scale (SMWEB) (see Table 1). Phase 2 Face validity of the Prototype SMWEB with multi- ethnic inputs Since the item pool were generated from largely Chinese Singaporean respondents. Additional samples were recruited to test the face validity of the prototype and to solicit inputs for additional items, especially from the non-Chinese Singaporean participants. Participants: Two samples were recruited for assessing the face validity of the SMWEB prototype. Sample one consisted of 161 Singa- porean university students (72 males and 89 females; mean age 22, sd = 1.5 years). This multi-ethnic sample consisted of 1.3% Malays, 1.3% Indians and 97% Chinese. Sample two consisted of participants attending a series of focus group discussions. 56 male and female Singaporean residents aged 18 - 69 years were recruited from the general population through conven- ience sampling. Among them, there were 25 Chinese, 16 Ma- lays and 15 Indians. We conducted 3 groups in English, and 1 each in Malay, Indian and Mandarin. Each group was made of 8 to 9 members of one of the national ethnic groups: Malays, Chinese and Indians. Procedure: Two types of procedures were used to identify face and con- tent validity: Individual ratings and focus group discussions. Rating for Face Validity: For sample one, the SMWEB-pro- totype was shown to the participants individually, they were asked to independently rate whether they she/he agree that the item measures the concept of mental wellbeing (Fink, 1995). The percentage of agreement that the item is a measure of wellbeing in Singapore was calculated and recorded. Focus Group Discussion on Content Validity: Focus group discussions were conducted with sample two. There were 8 or 9 members in each group and was facilitated by a research assis- tant of the same ethnic background speaking the same lan- guages as the participants. Focus group participants were asked to comment on the items of SMWEB and to make suggestions of additional items for meanings of mental wellbeing that were not included in the prototype. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 593  C. M. FEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 594 Table 1. Percentage of agreement for face validity and descriptive statistics of items in the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale. First Wave (N = 741) Second Wave (N = 2091) Items Percentage of “yes” answers (N = 161) M SD M SD 1. I feel balanced in myself. 95% 3.88 0.75 7.49 1.36 2. I am appreciative of life. 75% 3.99 0.73 7.81 1.11 3. I accept what life has to offer. 65% 3.93 0.72 7.66 1.24 4. I am able to accept myself. 80% 4.09 0.69 7.85 1.05 5. I am able to think clearly. 90% 4.13 0.69 7.9 0.99 6. I am able to think rationally. 90% 4.09 0.72 7.86 0.99 7. I am able to make good decisions. 55% 3.99 0.70 7.75 1.03 8. I am able to accept reality. 95% 4.06 0.69 7.78 1.12 9. I appreciate my own self-worth. 50% 4.07 0.7 7.86 0.99 10. I am able to make friends. 75% 4.18 0.72 7.97 1.01 11.I am able to keep company with others. 45% 4.13 0.69 7.91 1 12. I am able to seek help when needed. 50% 3.96 0.76 7.61 1.25 13. I am able to offer help to others. 45% 4.06 0.72 7.71 1.18 14. I am able to maintain a good family life. 50% 4.14 0.71 7.91 1.08 15. I feel peace. 45% 4.03 0.75 7.66 1.28 16. I seek for self-development/growth/cultivation. 40% 3.87 0.74 7.53 1.37 17. I am alert. 50% 4.04 0.67 7.76 1.06 18. I am not depressed. 90% 3.83 0.86 7.57 1.52 19. I am optimistic about the future. 60% 3.88 0.77 7.33 1.46 20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 75% 3.93 0.69 7.47 1.26 21. I am resilient under life s crises. 65% 3.81 0.70 7.33 1.32 22. I stand firm under stress 85% 3.84 0.73 7.39 1.31 23. I am spiritual. 35% 3.76 0.85 7.25 1.52 24. I am content. 65% 3.92 0.74 7.57 1.29 25. I am happy. 70% 4.01 0.77 7.71 1.19 26. I am calm. 60% 3.95 0.73 7.65 1.15 27. I have the strong support of my family and friends. 45% 4.12 0.76 7.89 1.11 28. I can handle most situations. 60% 3.94 0.71 7.51 1.22 29. I am able to contribute positively to the world. 65% 3.84 0.76 7.26 1.38 30. I believe that life is a continued development of myself. 55% 4.06 0.72 7.61 1.22 Note: Scale for wave 1; Scale for wave 2. Results: Results obtained from sample 1 are presented in Table 1. All items received more than 40% endorsement from the partici- pants. No disagreement was voiced from focus group partici- pants and no additional items were suggested. High positive endorsement was expressed by the non-Chinese participants as well. No additional items were added. No items were deleted. Study 2: Internal Structure and Construct Validity of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale The results of study 1 supported the hypothesis that the SMWEB shows appropriate content and face validity as a measure of mental wellbeing across different ethnic samples in Singapore. We then explored the psychometric property, inter-  C. M. FEN ET AL. nal structure and construct validity of the SMWEB with a na- tionally representative sample of Singaporean adults across a wide range of ages (18 - 84). Method Participants and Sampling Procedure: A nationally representative sample of 741 was recruited to participate in the study. The participants were obtained from the Department of Statistics Sampling Frame (Singapore Statistics Department, 2010). The sample was made of participants from a wide range of educational attainment, from no formal educa- tion to university graduates, with the average education around upper secondary school. The sample ages ranged from 18 to 69, with a mean of 43.80 years and sd of 13 years. We obtained national census statistics from the Department of Statistics of Singapore (2010) and conducted geographical stratification of the different housing zones in Singapore to closely resemble the ethnic distribution in the national census data. The resultant sample (N = 741) were also checked for ethnic distribution and it is evenly represented according to Singapore national census 2010. Table 2 presents the gender and ethnic distribution of the sample. Procedures: Participants were recruited by household interviews whereby the researchers randomly approached households in the geo- graphic zones from the Department of Statistics sample of Sin- gapore. Materials: In addition to the SMWEB, the following instruments were used to form the nomological net (Cronbach & Meel, 1955) for construct validation: 1) for concurrent validity: a measure of the same psychological construct—mental wellbeing but constructed for use by Scot Health in the United Kingdom: the Warwick Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWEBS) (Tennant et al., 2007), 2) for convergent and discriminant validity: measures of posi- tive affects (PA) (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) and subjec- tive wellbeing—Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffith, 1985) and measures of negative affect (NA) (Watson et al., 1988) and depression measured by the abbrevi- ated version of Asian Adolescent Depression Scale (AADS) (Woo, Chang, Fung, Koh, Kee, & Seah, 2004). Also used as a convergent measure of happiness, we calculated a Hedonic Balance (HB) indicator by calculating the algebraic difference between PA and NA. Data Analysis: Table 2. Gender and ethnic distribution of First and Second Wave samples. First Wave (N = 741) Second Wave ( N = 2091) Frequency Percentage (%) Frequency Percentage (%) Gender Male 343 46.3 599 28.6 Female 398 53.7 1492 71.3 Ethnicity Chinese 516 69.6 1453 69.4 Malay 115 15.5 340 16.3 Indian/ other 110 14.8 298 14.3 We first calculated the internal reliability, categorized the items into meaningful domains and identified the internal structure of the SMWEB scale. Exploratory factor analyses (CFA) followed by confirmatory factor analyses (EFA) were conducted to identify the best fit model of the SMWEB. Through correlation analyses, we identified the concurrent, convergent and discriminant validity of the SMWEB. Results Internal structure and reliability of SMWEB: Internal reliability: We found the internal reliability of the SMWEB to be a high α = .962. Structure of Mental Wellbeing A single latent construct Repeated factor analytic attempts have derived the conclu- sion that there is one underlying construct of SMWEB. The high internal reliability suggesting that the items were highly intercorrelated with each other supporting the hypothesis that there might be a singular underlying construct that defines mental wellbeing in Singapore. This result is similar to that of Tennant et al (2007) with the WMWEB that there is one latent construct of mental wellbeing. However, inspecting the scree plot and Eigen values of the principal component extraction results, suggested that the scale may be divided into several subcomponents, as has been found in other mental health (Campton, Smith, Cornish & Quell, 1996) and wellbeing (Heady, Kelley & Wearing, 1993) measures. Scree plots showed a shape L-shaped curve with one big com- ponent accounting for 48% of the variance. There were four factors with Eigen values larger than 1; the second, third and fourth component accounted for 4.5%, 4.19% and 3.5 % of variance respectively. Figure 1 presents the Scree plot and Table 3 presents of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale after Principal Component Analysis. Since there were 11 items loaded on the first factor, we fur- ther subjected the first factor to a second CFA. With extraction of two factors and Promax rotation, a two factor solution was found. The two factors showed items bearing the meaning of emotional intelligence and resilience and were highly in- ter-correlated (r = .73). Table 4 presents the results. The other three factors showed meanings of self-acceptance and self-cultivation, realistic and effective cognitive processes Figure 1. Scree plot of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale first wave data. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 595  C. M. FEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 596 Table 3. Principle component analysis of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale. Component Items 1 2 3 4 26. I am calm. 0.78 0.63 0.51 0.51 20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 0.77 0.52 0.61 0.53 25. I am happy. 0.77 0.71 0.46 0.52 22. I stand firm under stress 0.77 0.45 0.56 0.45 24. I am content. 0.77 0.61 0.38 0.47 21. I am resilient under life s crises. 0.75 0.5 0.56 0.48 19. I am optimistic about the future. 0.75 0.58 0.59 0.57 28. I can handle most situations. 0.74 0.48 0.58 0.57 30. I believe that life is a continued development of myself. 0.73 0.46 0.59 0.55 29. am able to contribute positively to the world (e.g. environment, work, community) 0.69 0.43 0.62 0.55 27. I have the strong support of my family and friends. 0.66 0.52 0.38 0.62 23. I am spiritual. 0.59 0.33 0.32 0.4 18. I am not depressed. 0.55 0.52 0.44 0.49 2. I am appreciative of life. 0.54 0.86 0.52 0.49 3. I accept what life has to offer. 0.53 0.82 0.46 0.48 4. I am able to accept myself. 0.53 0.78 0.67 0.53 1. I feel balanced in myself 0.52 0.72 0.46 0.43 8. I am able to accept reality. 0.53 0.7 0.64 0.58 15. I feel peace. 0.65 0.66 0.64 0.56 5. I am able to think clearly. 0.52 0.61 0.83 0.5 6. I am able to think rationally. 0.53 0.6 0.81 0.54 7. I am able to make good decisions. 0.55 0.55 0.77 0.54 17. I am alert. 0.6 0.38 0.73 0.52 9. I appreciate my own self-worth. 0.56 0.64 0.72 0.58 16. I seek for self- development/growth/cultivation 0.6 0.33 0.61 0.44 11. I am able to keep company with others. 0.53 0.46 0.52 0.87 10. I am able to make friends. 0.5 0.47 0.55 0.83 13. I am able to offer help to others. 0.6 0.5 0.54 0.79 12. I am able to seek help when needed. 0.48 0.45 0.44 0.74 14. I am able to maintain a good family life. 0.64 0.59 0.55 0.69 Table 4. Principal component with Promax rotation and Keiser normalization of factor 1 of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale. Component 1 2 20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 0.84 0.58 21. I am resilient under life s crises. 0.8 0.57 30. I believe that life is a continued development of myself. 0.78 0.55 19. I am optimistic about the future. 0.78 0.63 22. I stand firm under stress 0.77 0.59 28.I can handle most situations. 0.77 0.61 29. I am able to contribute positively to the world (e.g. environment, work, community) 0.75 0.54 24. I am content. 0.59 0.87 25. I am happy. 0.66 0.85 26. I am calm. 0.68 0.82 27. I have the strong support of my family and friends. 0.61 0.67 23. I am spiritual. 0.44 0.66  C. M. FEN ET AL. and social intelligence. Therefore, a five factor hypothesis was proposed to account for the first wave data. Based on the theo- retical content of the items, the list was sorted into a five factor structure with more conceptual clarity than the CFA results: Asian self-esteem, Emotional intelligence, Resilience and Cog- nitive efficacy. Five Meaningful Dimensions Literature on the construct of mental wellbeing identified in North America suggested multiple meaningful dimensions (Ryff & Singer, 1989; Keyes, 2002). Inspection of the item content of the SMWEB Scale and the CFA results, the items were conceptually grouped into five meaning dimensions: Cog- nitive efficiency (CE), Asian Self-esteem (ASE), Social intelli- gence (SI), Emotional intelligence (EI) and Resilience (RE). Meaningful Dimensions: Asian Self-Esteem (ASE): refers to the acceptance of the self and the belief that the self is a dynamic process that is continu- ously evolving through growth and learning. ASE consists of the following items (see Table 5). Social Intelligence (SI): refers to the knowledge and com- petence in developing good social relationships and interde- pendence with others. SI consists of the following items (see Table 6). Emotional Intelligence (EI): refers to the intelligence of be- ing able to recognize and manage one’s own emotions to achieve happiness and peace. EI consists of the following items (see Table 7). Resilience (RI): refers to the psychological processes that enable the individual to withstand negative impact in life and to thrive in the face of difficulty. RI consists of the following items Table 5. Descriptive statistics of Asian self-esteem. Items Mean SD 4. I am able to accept myself. 4.09 0.69 9. I appreciate my own self-worth. 4.07 0.70 16. I seek for self-development/growth/cultivation. 3.87 0.74 29. am able to contribute positively to the world (e.g. environment, work, community) 3.84 0.76 30. I believe that life is a continued development of myself. 4.06 0.72 Note: Internal Reliability α = .834. Table 6. Items and descriptive statistics of social intelligence (N = 741, Likert Scale 1 - 5). Items Mean SD 10. I am able to make friends. 4.18 0.72 11. I am able to keep company with others. 4.13 0.69 12. I am able to seek help when needed. 3.96 0.76 13. I am able to offer help to others. 4.06 0.72 14. I am able to maintain a good family life. 4.14 0.71 28. I can handle most situations. 3.94 0.71 Note: Internal Reliability α = .866. (see Table 8). Cognitive Efficacy (CE): refers to the cognitive skills and competence the individual possesses that enables the individual to perceive the world in a realistic way and to be able to make effective decisions in order to manage one’s life events. CE consists of the following items (see Table 9). Each dimension showed high internal reliability suggesting that the dimensions are internal coherent. These dimensions were also inter-correlated with each other, suggesting that they Table 7. Items and descriptive statistics of emotional intelligence (N = 741, Likert Scale 1 - 5). Items Mean SD 1. I feel balanced in myself. 3.88 0.75 2. I am appreciative of life. 3.99 0.73 3. I accept what life has to offer. 3.93 0.72 8. I am able to accept reality. 4.06 0.69 15. I feel peace. 4.03 0.75 18. I am not depressed. 3.83 0.86 23. I am spiritual. 3.76 0.85 24. I am content. 3.92 0.74 25. I am happy. 4.01 0.77 26. I am calm. 3.95 0.73 Note: Internal Reliability α = .90. Table 8. Items and descriptive statistics of resilience (N = 741, Likert Scale 1 - 5). Items Mean SD 19. I am optimistic about the future. 3.88 0.77 20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 3.93 0.69 21. I am resilient under life s crises. 3.81 0.70 22. I stand firm under stress 3.84 0.73 27. I have the strong support of my family and friends. 3.94 0.71 Note: Internal reliability α = .84. Table 9. Items and descriptive statistics of cognitive efficacy (N = 741, Likert Scale 1 - 5). Items Mean SD 5. I am able to think clearly. 4.13 0.69 6. I am able to think rationally. 4.09 0.72 7. I am able to make good decisions. 3.99 0.7 17. I am alert. 4.04 0.67 Note: Internal Reliability α = .850. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 597  C. M. FEN ET AL. might belong to the same underlying latent construct. Table 10 presents the dimensions and internal reliability of each dimen- sion. Table 11 presents the inter-correlations between dimen- sions and the SMWEB. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the fit of the data to the hypothesized five factor model using AMOS 19. Following latest convention on selecting fit indices (Kenny, 2012), we presented the χ2, normed fit index (NFI), Comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of ap- proximation (RSMEA).We found a reasonably good fit with the following indices: χ2 = 14.7, df = 5, p < .01, NFI = .981, CFI = .985, RSMEA = .122. However, when errors were allowed to correlate between ASE and CE, which reduced the RMSEA to .000, the fit is nearly perfect, χ2 = 3.161, df = 4, p = .531; NFI = .99. CFI = 1.00. The dimensions were shown to have standardized regress weights of .81 (ASE), .88 (SI), .91 (EI), .83 (RI) & .88 (CE) on the underlying latent construct. Therefore, the model of five manifested dimensions with one latent variable model is strongly supported (see Figure 2). Construct validity Concurrent validity: It can be seen that the SMWEB corre- lated positively with the WEMWEBS with high magnitude. Supporting concurrent validity, SMWEB and WMWEB showed shared variance of around 38% (r =.88, p < .000) suggesting that Table 10. Descriptive statistics of the SMWEB meaningful dimensions in the First and Second Waves. First Wave Second Wave M SD α M SD α ASE 3.97 0.55 0.83 7.62 0.96 0.86 SI 4.08 0.55 0.87 7.83 0.86 0.87 EI 3.96 0.56 0.9 7.62 0.96 0.96 RI 3.86 0.58 0.84 7.4 1.12 0.96 CE 4.09 0.59 0.85 7.82 0.88 0.89 Note: SMWEB: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale; ASE: Asian Self Esteem; SI, Social Intelligence, EI: Emotional Intelligence; RI: Resilience CE: Cognitive Efficacy, First Wave scale 1 - 5; second Wave scale 1 - 9. Table 11. Correlation Matrix of the SMWEB and its meaningful dimensions. SMWEB ASE SI EI RI CE SMWEB 1 ASE 0.82** 1 SI 0.89** 0.76** 1 EI 0.92** 0.72** 0.77** 1 RI 0.93** 0.78** 0.74** 0.82** 1 CE 0.80** 0.70** 0.69** 0.72** 0.67** 1 M 3.99 3.45 4.08 3.96 3.9 4.09 SD 0.51 0.48 0.55 0.56 0.55 0.59 Note: SMWEB: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale; ASE: Asian Self Esteem; SI, Social Intelligence, EI: Emotional Intelligence; RI: Resilience CE: Cognitive Efficacy. **significance <0.01. SWMEB measures a highly similar construct of WEM-WEB. Convergent and discriminant validity: As a mental wellbeing measure, it is expected that the SMWEB should correlate posit- ively with measures of happiness, assessed as Hedonic Balance (HB) and life satisfaction (LS); it should correlate negatively with negative affects (NA) and depression. However, as men- tioned earlier, mental wellbeing is a conceptually larger con- struct from happiness (Keyes & Haidt, 2002; Ryff, 1989; Vit- terso, 2004, Waterman, 1993). So it should correlate with the happiness measures positively but moderately compared to its correlation with the WMWEBS (Campbell & Fiske, 1955). This was supported by its positive but moderate correlations with HB and LS Scales, and moderate negative correlations with NA and the Asian Adolescent Depression (AAD) Scales. Table presents the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of SMWEB, WMWEB and other validating variables (See Table 12 for the correlations). We therefore have sufficient support that the SMWEB is in- deed a measure of mental wellbeing, which is a larger concept than happiness. Study 3: Construction of a Short Form of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (SMWEB-S) We aimed to use the SMWEB for population level screening Figure 2. Five dimension model CFA long form. Table 12. Correlation matrix between the SMWEB and validation variables in the First Wave sample. SWLSAADSPA HB SMWB WEMWEBS SWLS 1 AADS −0.38** 1 PA 0.37** −0.23** 1 HB 0.42** −0.48** 0.78** 1 SMWB 0.64** −0.43** 0.43** 0.52** 1 WEMWEBS 0.72** −0.46** 0.46** 0.54** 0.81** 1 M 3.572.123.50 1.75 3.98 3.82 SD 0.720.670.82 1.08 0.50 0.59 α. 0.880.940.96 0.89 0.79 0.85 Note: **significance <0.01. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 598  C. M. FEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 599 for health promotion purposes. To facilitate the ease of use for screening purposes at the population, Study 3 aimed to con- struct a short form of the SMWEB. The short form should re- tain the internal structure and meaningfulness of the SMWEB in order to be a viable alternative for assessing the same under- lying constructs—mental wellbeing. Method Participants: Two samples were used for this purpose. Sample 1 consisted of the sample used in Study 2 (N = 741). A new and larger nationally representative sample (N = 2091) was recruited with the same geographical sampling method for the construction of a short form and for further validation in Study 4. Procedure: The following steps were conducted to construct and validate the short form of SMWEB Scale: Item selection and validation: We carefully review the items within each dimension and selected the items that showed high item total correlations and delete the ones that are redundant with other items in the same dimension. The selected items were then forming a prototype short scale. Identifying internal reliability and meaningful structure: We then assessed the internal reliability of each new dimension and the new prototype. Comparing mean differences with the SMWEB: We com- pared the item mean of the short prototype against the item mean of SMWEB in both samples, until we identify a prototype that showed no quantitative difference from the 30 item original and show high internal reliability of the whole scale as well as acceptable internal reliability of each dimension. Results After 21 iterations we finally identified a short form of the SMWEB that fulfilled these criteria. Table presents the items selected for the Singapore Mental Wellbeing-Short Form (SMWEB-S). The selected items and their conceptual groupings are pre- sented in Table 13. The internal reliability of the short form SMWEB-S (16 items; α = .932, p < .000) is high and accept- able. The short form SMWEB-S showed no significant item mean differences from that of the original form in either sample: Paired t-tests showed t = 1.658, df = 740, p = .097 for Sample 1 and t = 6.196, df = 2090, p = .00 for Sample 2, though signifi- cant but with mean differences = .019, r = .986, the differences were negligible and acceptable. The SMWEB-S showed the same concurrent, discriminant and convergent validity as the SMWEB (See Table 14). The SMWEB-S was also found to be highly correlated with the SMWEB in both the first sample (N = 741) and the second sample (N = 2091). Tables 15-17 pre- sent the results. CFA showed that the best fit model is the five factor model Table 13. Item Means and standard deviation of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-Short Form (SMWEB-S). First Wave (N = 741) Second Wave (N = 1029) Items M SD M SD S2. I am appreciative of life. 3.99 0.73 7.81 1.11 S19. I am optimistic about the future. 3.88 0.77 7.33 1.46 S9. I appreciate my own self-worth. 4.07 0.70 7.86 0.99 S13. I am able to offer help to others. 4.06 0.72 7.71 1.17 S16. I seek for self- development/growth/cultivation 3.87 0.74 7.53 1.37 S7. I am able to make good decisions. 3.99 0.70 7.75 1.03 S5. I am able to think clearly. 4.13 0.69 7.9 1.00 S20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 3.93 0.69 7.47 1.26 S25. I am happy. 4.01 0.77 7.71 1.20 S26. I am calm. 3.95 0.73 7.65 1.15 S23. I am spiritual. 3.76 0.85 7.25 1.52 S24. I am content. 3.92 0.74 7.57 1.29 S10. I am able to make friends. 4.18 0.72 7.97 1.01 S8. I am able to accept reality. 4.06 0.69 7.78 1.12 S4. I am able to accept myself. 4.09 0.69 7.85 1.05 S12. I am able to seek help when needed. 3.96 0.76 7.61 1.25 Αlpha 0.93 0.94  C. M. FEN ET AL. Table 14. Items and descriptive statistics of the SMWEB-s meaningful dimensions in First and Second Waves samples. First Wave (N = 741) Second Wave (N = 2091) M SD α M SD α ASES 0.83 .86 9. I appreciate my own self-worth. 4.07 0.7 7.86 0.99 30. I believe that life is a continued development of myself. 4.06 0.72 7.61 1.22 4. I am able to accept myself. 4.09 0.69 7.85 1.05 SIS 0.87 0.87 13. I am able to offer help to others. 4.06 0.72 7.71 1.18 10. I am able to make friends. 4.18 0.12 7.97 1.01 12. I am able to seek help when needed. 3.96 0.76 7.61 1.25 EIS 0.90 0.96 2. I am appreciative of life. 3.99 0.73 7.81 1.11 25. I am happy. 4.01 0.77 7.71 1.19 26. I am calm. 3.95 0.73 7.65 1.15 23. I am spiritual. 3.76 0.85 7.25 1.52 24. I am content. 3.92 0.74 7.57 1.29 8. I am able to accept reality. 4.06 0.69 7.78 1.12 RIS 0.84 0.96 19. I am optimistic about the future. 3.88 0.77 7.33 1.46 20. I am able to cope with life s challenges. 3.93 0.69 7.47 1.26 CES 0.85 0.89 7. I am able to make good decisions. 3.99 0.70 7.75 1.03 5. I am able to think clearly. 4.13 0.69 7.90 0.99 SMWEB: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale; ASE: Asian Self Esteem; SI, Social Intelligence, EI: Emotional Intelligence; RI: Resilience CE: Cognitive Efficacy. Table 15. Correlation of Singapore Mental Wellbeing-Short Form (SMWEB-S) with the five meaningful dimensions in singapore mental wellbeing scale (SMWEB) (first wave N = 741, on liker scale 1 - 5). SMWEB-S ASE SI EI RI CE SMWEB-S 1 ASE 0.82** 1 SI 0.89** 0.72** 1 EI 0.92** 0.72** 0.78** 1 RI 0.93** 0.76** 0.77** 0.87** 1 CE 0.80** 0.71** 0.69** 0.72** 0.70** 1 Mean 3.99 3.45 4.08 3.96 3.9 4.09 SD 0.51 0.48 0.55 0.56 0.55 0.59 Note: NB: SMWEB-S: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-Short Form; ASE: Asian Self Esteem; SI, Social Intelligence, EI: Emotional Intelligence; RI: Resilience; CE: Cognitive Efficacy. **p < .000. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 600  C. M. FEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 601 Table 16. Correlation of the singapore mental wellbeing scale-short form (SMWEB-S) and the five meaningful domains within the SMWEB-S (second wave N = 2091, on likert scale 1 - 9). SMWEBS ASES SIS EIS RIS CES SMWEBS 1 ASES 0.90** 1 SIS 0.82** 0.82** 1 EIS 0.93** 0.76** 0.67** 1 RIS 0.83** 0.68** 0.62** 0.72** 1 CES 0.76** 0.73** 0.58** 0.68** 0.55** 1 Mean 7.67 7.81 7.76 7.63 7.4 7.82 SD 0.87 0.89 0.97 0.97 1.26 0.93 Note: SMWEBS: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; ASES: Domain 1 of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; SIS: Domain 2 of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; EIS: Domain 3 of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; RIS: Domain 4 of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; CES: Domain 5 of Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale –short form; **p < .01. Table 17. Convergent validity and discriminant validity of Singapore mental wellbeing scale-short form (SMWEB-S) (first wave N = 741, likert scale 1 - 5). SMWEB-S SWLS AADS PA NA SMWEB-S 1 SWLS 0.64** 1 AADS −0.41** −0.38** 1 PA 0.41** 0.37** −0.23** 1 NA −0.30** −0.22** 0.48** −0.04 1 Mean 3.99 3.58 2.12 3.5 1.75 SD 0.51 0.72 0.67 0.82 0.68 Note: SMWEB-S: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-short form; SWLS: Subjective wellbeing measured as Life Satisfaction; AADS: Asian Adolescent (Is it Adolescent or Adult as the study conducted among adult Singaporeans?) Depression Scale; PA: Positive Affects; NA: Negative Affects. **p < .01 as shown in Figure 3. With the following fit indices: χ2 = 3.036, df = 2, p = .219, NFI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, RSMEA = .016. Be- cause of the correlated errors between ASES and CES, and between EI and RI, we further tested two alternative models: The Keyes three-factor-model (Keyes, 2002) with ASES and CES combined to form a Positive Self Function (PSF) factor and EIS and RIS combined to form an Emotional Wellbeing (EIW) factor. CFA showed that the model is underidentified. A four factor model, with ASES and CES combined into PSF but EIS and RIS remained as two separate factors, was tested; CFA showed a reasonable fit but the χ2 = 15.491; df = 1, p = .000, RMSEA = .084, suggesting a poorer fit than the five-factor- model of χ2 = 3.036, df = 2, p = .219 and RMSEA = .016. We chose the five-factor-model as the best model of SMWEB-S. Study 4: Differentiating Mental Wellbeing from Mental Disorder Figure 3. Five dimension model CFA sample 2 short form. Three questions were addressed in Study 4 as further valida- tion of the SMWEB-S: Its concurrent validity with the World Health Organization Mental Wellbeing, the WHO-5 (WHOM), developed by the World Health Organization (2010), its dis- criminant validity with mental illness indicators and a potential ceiling effect. The SMWEB-S was constructed on the concep-  C. M. FEN ET AL. tualization and expected manifestation of mental health of Sin- gaporeans. We intended to further validate the construct valid- ity of the SMWEB-S by analyzing its relationship with the pan- culturally applicable measure of mental wellbeing, the WHOM. Research literature on mental health (for instance, Jahoda, 1958) has suggested that mental wellbeing should be seen as a concept in its own right rather than as the opposite end of men- tal illness. Keyes, Shmotkin & Ryff (2002) had empirically shown that measures of mental wellbeing are either orthogonal or moderately correlated with measures of mental illness. In Study 4 we aimed to further test the validity of the SMWEB-S as a measure of mental wellbeing by analyzing its relationship with measures of mental disorders. Mental wellbeing is defined as a construct that reflects per- sonal striving (Carver, 1998; Emmons, 1986: p. 199); personal striving is guided by the life goals (Oishi, 2001) set by the indi- vidual. In Singapore, financial earning and education attain- ment are commonly shared goals. We therefore chose personal income and education attainment as criterion measures of SWMEB-S to test its predictive validity. The SMWEB constructed in the first wave of validation used a response scale of 1 to 5. The frequency distribution in Study 2 showed a negatively skewed distribution with over 50% of the scores fell between 4 and 5 (sees Figure 4). Because of a concern about a potential ceiling effect, a longer Likert scale response format from 1 to 9 was used in this current study to provide more response options for the respon- dents. Method Participants: A nationally representative sample of 2091 participants was recruited for the present study. Table presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. Procedure and Materials The following instruments were used: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-Short Form (SMWEB-S): The 16 item Singapore Mental Wellbeing-Short Form (SMWEB- S) was used. In the current study, the response format was the following: 1---2---3---4---5---6---7---8---9, with 5 as the neutral point, 1 being never, and 9 being always. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ): The general health questionnaire has been widely used as a screening tool for mental disorders. It consists of self-reported symptoms of af- Figure 4. Sample distribution of SMWEB, first wave. fective disturbance—anxiety and depression and social dys- functions (Goldberg & Williams, 1988). The version we used for the current validation is the GHQ12 (12 items) each item is rated on a four point scale (less than usual to much more than usual). For the current sample, the GHQ showed an internal reliability α = .717 for the entire scale, α = .838 for the anxiety and depression subscale, and α = .894 for the social dysfunction subscale. They are moderate but acceptable. World Health Organization Mental Health Measure (WHOM): The world Health Organization published a short mental health measure, which consists of five items that tap the definition of mental health by WHO. The internal reliability of the WHOM for the present sample was found to be α = .915. Information on Personal Income and Level of Education At- tainment Personal income and level of education attainment were as- sessed as part of the demographic information of respondents. Personal income was rated in reported dollar value of monthly income and categorized into a rating scale of 0 - 10; education attainment was rated on the level of formal education attained and also rated into a scale of 0 - 10. Data Analysis: Constructing subscale scores and Correlation matrix: The item mean of each subscales of each measurement used was first calculated. This resulted in a smaller number of input vari- ables for large scale analysis. A correlation matrix was con- structed to present the intercorrelations, internal reliability and descriptive statistics of the variables entered into analyses. Exploratory (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA): Exploratory factor analysis of the constructed sub-scale scores was conducted to see whether the subscale scores fell into the same groupings as the scales they originated from. Predictive Validity through Regressions: Finally, to further validate the construct validity of mental wellbeing as positive functions, the hypothesized outcome variables, individual in- come and education attainment were regressed on SMWEB-S to explore the predictive validity of SMWEB-S. Results With the extended response format of 1 to 9, more response options are afforded in order to reduce the ceiling effect. Though the mean remains high at 7.66 (median = 8.00), only 5% of the responses are at the ceiling of 9, which is at the chance level. There is obviously a positive bias in responses to wellbeing measures (see Figure 5) (Diener, Wirtz, & Tov, 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 3.01-4.00 4.01-5.00 5.01-6.006.01-7.00 7.01-8.00 8.01-9.00 Number of Parti cipant s Figure 5. Sample distribution of SMWEB, second wave. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 602  C. M. FEN ET AL. 2010). This result again is similar to Tennet et al.’s (2007) find- ing in Scotland. SMWEB-S, SMWEB and WHOM were found to be highly correlated suggesting concurrent validity of SMWEB-S as a measure of mental wellbeing (Table 18). Correlation matrix showed that the components of GHQ, de- pression and anxiety are negatively correlated with components of SMWEB-S, while social dysfunction was moderately related to SMWEB-S. Social dysfunction was conceptually similar to positive functions measured by SMWEB-S; so it was dropped from further analysis. Table 19 presents the correlation results. A series of factor analysis on SMWEB-S dimensions and GHQ anxiety and depression dimensions consistently showed that the wellbeing dimensions and GHQ dimensions fell into two categories. Tables 20-22 present the CFA results. A one latent variable model with the five dimensions of SMWEBS and WHOM as the sixth manifested dimension (see Figure 6) was tested and found to have an excellent fit: χ2 = 8.50, df = 4, p = .075, NFI = .999, CFI = .999, RSMEA = .023, supporting the hypothesis that SMWEBS and the WHOM jointly tap the same underlying latent construct mental wellbe- ing, which we labeled Thriving. Using components of SMWEB-S and the depression and anxiety components of GHQ, a two factor model of mental wellbeing and mental disorder showed excellent fit (see Figure Table 18. Correlation of the Singapore Mental Wellbeing-Short Form (SMWEB- S), with the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (SMWEB) and Scot Health Mental Wellbeing Scale (MWEB) (first wave N = 741, Liker Scale 1 - 5). SMWEB-S WEMWEBS SMWEB SMWEB-S 1 WEMWB 0.80** 1 SMWEB 0.98** 0.81** 1 Mean 3.99 3.82 3.98 SD 0.51 0.6 0.5 Note: NB: SMWEB-S: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale-Short Form; WEM- WEBS: The Warwick-Edingburg Mental Wellbeing Scale;, SMWEB: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale (**p < .001). Table 19. Correlations between GHQ components of anxiety and depression and dimensions of SMWEBS. AX DP ASE SI EI RI CE AX 1 DP 0.62** 1 ASE −0.20** −0.24** 1 SI −0.16** −0.20** 0.71** 1 EI −0.26** −0.28** 0.75** 0.67** 1 RI −0.24** −0.30** 0.68** 0.62** 0.72** 1 CE −0.20** −0.22** 0.72** 0.58** 0.68** 0.55**1 Note: **p < .01. 7). We found a reasonably good fit: χ2 = 66.54, df = 10, p =.000, NFI = .999, CFI = .999, RSMEA = .052. This result supported the claim by Ryff (1989) and Keyes et al., (2002) that mental wellbeing and mental disorder are two moderately related but independent constructs. They negatively correlated with each Table 20. Factor loadings for exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation of Singapore Mental Health Scale, world health organization mental health scale and global health questionnaire and social desirability scale. Component 1 2 SMWEB 0.89 WHO 0.88 0.18 GHQ 0.98 Note: SMWEB: Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale; WHO: World Health Or- ganization Mental Health Scale; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire. Table 21. Factor loading for exploratory factor analysis of components of GHQ, anxiety and depressions and dimensions of Singapore Mental Wellbe- ing Scale-Short Form. Component 1 2 AX 0.81 DP 0.78 ASES 0.88 SIS 0.81 EIS 0.89 RIS 0.83 CES 0.80 Note: Factor loadings that were larger than 0.4 were shown in the table. Table 22. Factor loadings of WHO mental wellbeing measure (WHO5) and di- mensions of SMWEBS and anxiety and depression of GHQ. Component 1 2 AX 0.81 DP 0.78 ASES 0.87 SIS 0.80 EIS 0.89 RIS 0.83 CES 0.79 WHO5 0.66 Note: Factor loadings that were larger than 0.4 were shown in the table. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 603  C. M. FEN ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 604 Figure 6. Six dimension model CFA of mental wellbeing-thrive. Figure 7. Two factors model of complete mental health.  C. M. FEN ET AL. other in moderate magnitude (r = −.35, p <.00). Figure 7 graphically represents the two factor model. We added the WHOM into the model and found an excellent fit (χ2 = 99.69, df = 14, p =.00, NFI = .989, CFI = .993, RSMEA = .054). However, the correlation between the mental health model, which consists of components of SMWEB-S and WHOM, and the mental disorder factor remains the same at r = .−36, meaning that WHOM did not add additional variance to the relationship between SMWEB-S and mental disorder. These results further reinforce the construct validity of the SMWEB-S as a measure of mental wellbeing, not merely a measure of absence of mental illness. Predictive validity of the SMWEB-S was supported by re- sults of regression analysis. We found that SMWEB-S predicts individual income (β = .043, R2 = .002, p = .000) and education attainme nt (β = .101, R2 = .014, p = .000) with statistical signi- ficance, suggesting that the SMWEB-S is tapping an underlying construct that facilitates the pursuit of culturally sanctioned goals. Discussion The concept of mental wellbeing refers to a set of psycholo- gical processes that promote positive outcomes in a person’s life (Hefferon & Boniwell, 2010). This psychological construct has been found in contemporary research literature to be inde- pendent of mental disorder (Ryff, 1989; Keyes & Annas, 2009). As underlying psychological processes, mental wellbeing’s manifestations would be shaped and conditioned by the pre- vailing values and social ecological conditions of the environ- ment (Christopher, 1999; Ryff, 1989, Tov & Diener, 2010). We used a series of qualitative interviews, focus group discus- sions to identify the meanings and manifestations of mental wellbeing in Singapore, which included not only emotional happiness but also positive functions that are believed to be healthy. Using these results we constructed the Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale and carefully selected items to con- struct the short form of the SMWEB (SMWEB-S). The SMWEB-S concurred with other measures of mental wellbeing: the UK constructed Warwick Mental Wellbeing Scale (WMWEBS) and the pan-cultural mental wellbeing Scale of the World Health Organization (WHOM). It moderately correlated with hedonic balance and life satisfaction (happiness) and negatively correlated with negative affects and depression. This pattern of correlations supports the conclusion that the SMWEB-S taps an underlying process of mental wellbeing which goes beyond merely happiness but also include positive functions of the individual. The high internal reliability suggests that the SMWEB-S taps a single underlying construct. Examining the meaning of the items, we found that they could be grouped into five meaning- ful groups: Asian Self-Esteem consists of items that denote self-acceptance and self-development, Emotional Intelligence refers to feeling calm and peaceful, content. Social Intelligence refers to interdependence and reciprocal support with others. Resilience refers feeling in control and being able to cope with challenges in life, and finally Cognitive Efficacy refers to being vigilant, being able to think realistically and rationally. These five groups of items formed five sub-subscales or dimensions of the SMWEB-S. Each dimension is internally coherent and can stand on its own; however the five facets are highly corre- lated suggesting that they are different manifestations of the same underlying process. This was confirmed with CFA analy- ses. However, we found that SMWEB-S only moderately corre- lated with GHQ’s anxiety and depression symptoms. We hy- pothesized a two factor model with anxiety and depression being the manifested variables of mental disorder (MD), and dimensions of SMWEB as manifested variables of the mental wellbeing. CFA found an excellent fit. We added WHOM to the model as one of the manifested variables of mental wellbe- ing-thriving. The fit is nearly perfect, suggesting that mental wellbeing and mental disorders are two separate factors re- flecting two separate underlying psychological processes. Finally, if SMWEB-S is indeed a measure of positive mental functions, it should predict success in life, especially success measured in terms of popular and culturally sanctioned goal pursuit (Tov & Diener, 2009). In Singapore, these culturally sanctioned measures of success are personal income and educa- tional attainment. The SMWEB-S was found to concur signifi- cantly with personal income and education. These results fur- ther support that the SMWEB-S taps a culturally sanctioned construct of thriving, growth and development that goes beyond merely happiness. Conclusion In conclusion, the SMWEB is a measure of positive psycho- logical functions in Singapore. It taps a construct that goes beyond happiness to include positive functions of the individ- ual’s psychological systems. Mental wellbeing in Singapore is a single construct with five meaningful dimensions that reflect Singaporeans’ understanding of wellbeing: being peaceful and content, valuing the self in continued growth; reciprocating interdependence, thinking realistically and rationally, and being strong and resilient. These five meaningful dimensions reflect the values and beliefs of the contemporary Asian culture. The Singapore Mental Wellbeing Scale is therefore empirically valid and culturally meaningful as a screening tool for mental wellbeing in Singapore. REFERENCES Block, J. H., & Block, J. (1980). The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), Development of cognition, affect and social relations: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 39-101). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Bowling, A., Gabriel, Z., Dykes, J., Marriott-Dowling, L., Evans, O., Fleissig, A., Banister, D., & Sutton, S. (2003). Let’s ask them: A na- tional survey of definitions of quality of life and its enhancement among people aged 65 and over. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56, 269-306. Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of wellbeing. Chicago: Aldine. Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (1982). Structure of psychological wellbeing: A social historical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 43, 653-673.doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.4.653 Camfield, L. (2006). The why and the how? Understanding subjective wellbeing in four developing countries: Exploratory work by the WoD group. Wellbeing in Developing Countries Group, Economic and Social Research Council. Bath: University of Bath. Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bul- letin, 56, 81-105. doi:10.1037/h0046016 Campton, W. C., Smith, M. L., Cornish, K. A., & Quell, D. L. (1996). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 605  C. M. FEN ET AL. Factor structure of mental health measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 402-413. Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and link- ages. Journal of Social Issues, 54, 245-266. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01217.x Christopher, J. C. (1999). Situating psychological wellbeing: Exploring the cultural roots of its theory and research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 77, 141-152. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02434.x Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Edua- tion and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37-46. doi:10.1177/001316446002000104 Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psycho- logical tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281-302. doi:10.1037/h0040957 Department of Statistics of Singapore (2010). Singapore census statis- tics. Singapore City: Department of Statistics of Singapore. Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larson, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). Satis- faction with life scale. Journal of personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W. et al. (2009). New measures of wellbe- ing: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247-66. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12 Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal striving: An approach to personality and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 51, 1058-1068. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.1058 Emmons, R. A. (1991). Personal strivings, daily life events, and psy- chological and physical wellbeing. Journal of Personality, 59, 453- 472. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00256.x Fink, A. (1995). How to measure survey reliability and validity (Vol. 7). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A users guide to the general health questionnaire. Slough: NFER-Nelson. Heady, B. W., Kelley, J., & Wearing, A. J. (1993). Dimensions of mental health: Life satisfaction, positive affect, anxiety, and depres- sion. Social Indicators Research, 29, 63-82. doi:10.1007/BF01136197 Hefferon, K., & Boniwell, I. (2011) Positive psychology: Theory, re- search, and applications. New York: Open University Press/Mc- Graw-Hill. Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concept of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books. doi:10.1037/11258-000 Kaneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwartz, N. (1999). Wellbeing: The foundation of hedonic psychology. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation. Kenny, D. A. (2012). Measuring model fit. http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languish- ing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207-222. doi:10.2307/3090197 Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness or mental health? Investigating axiom of the complete state of health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 539-548. Keyes, C., &Annas, J. (2009). Feeling good and functioning well: Dis- tinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 117-125. doi:10.1080/17439760902844228 Keyes, C. L. M., & Haidt, J. (2002a). Introduction: Human flourish- ing—The study of that which makes live worth living. In C. L. M. Keyes, & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived (pp. 3-12). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Keyes, C. L. M., & Haidt, J. (2002). Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Keyes, C., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing wellbeing: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 82, 1007-1022. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007 Mental Health Ireland (2008). Mental health act of Ireland. Irish Stat- ute Book. Oishi, S. (2001). Goals, culture and subjective wellbeing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1674-1682. doi:10.1177/01461672012712010 Ryan, R., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudemonic wellbeing. Annual Re- view of Psychology, 52, 141-166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Exploration on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. Journal of Personality and So- cial Psychology, 57, 1069-1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological wellbeing revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719-727. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 1-28. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0901_1 Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). The past and future of positive psychology. In C. L. M. Keyes, & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychol- ogy and the life well lived (pp. 14-20) Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Suh, M. E., & Diener, E. (2000). Self—The hyphen between culture and subjective wellbeing. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective wellbeing (pp. 63-87). Cambridge, MS: The MIT Press. Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Welch, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The War- wick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Develop- ment and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 63. Tov, W., & Diener, E. (2009). The wellbeing of nations: Linking to- gether trust cooperation and democracy. The Science of wellbeing, Research in Social Indicators Series, 37, 155-173. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2350-6_7 Valliant, G. E. (2000). Adaptive mental mechanisms. Their role in a positive psychology. American Psychologist, 55, 89-98. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.89 Vitterso, J. (2004). Subjective wellbeing versus self-actualization: Using the flow simplex to promote a conceptual clarification of sub- jective quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 65, 299-331. doi:10.1023/B:SOCI.0000003910.26194.ef Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudemonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Jour- nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 671-691. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.678 Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. (1988). The development and validation of short measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 World Health Organization (1948). World Health Organization consti- tution. Geneva: World Health Organization. World Health Organization (2001). The world health report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding. Geneva, World Health Organi- zation. World Health Organization (2007). Mental health: Strengthening men- tal health promotion, WHO Fact Sheets, No. 220. Geneva, World Health Organization. World Health Organization (2010) WHO-five well-being index (WHO- 5). http://www.who-5.org/ Woo, B. S. C., Chang, W. C., Fung, D. S. S., Koh, J. B. K., Leong, J. S. F. Kee, C. H. Y., & Seah, C. K. F. (2004). Development and valida- tion of a depression scale for Asian adolescents, Journal of Adoles- cence, 27, 677-689. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.12.004 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 606

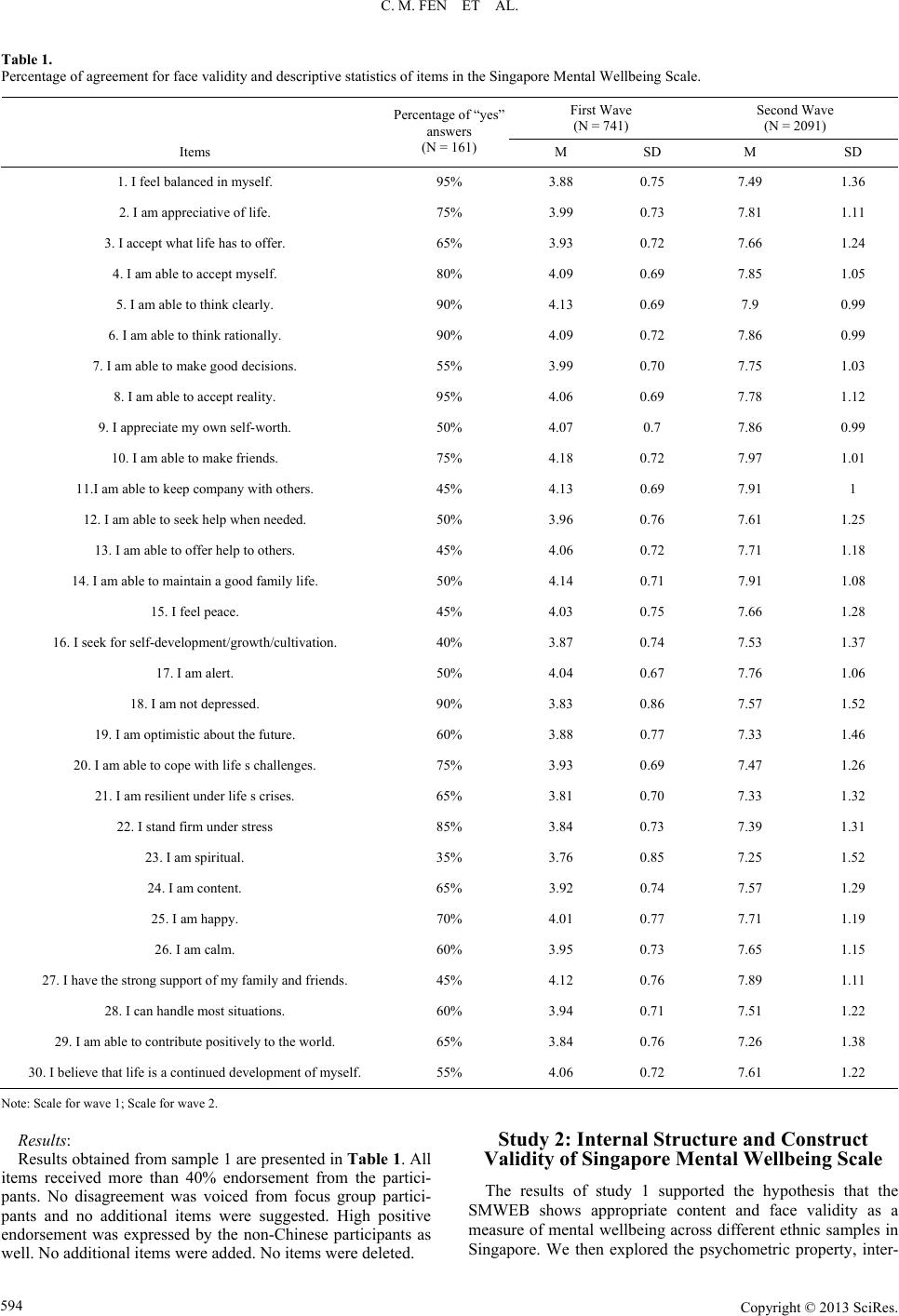

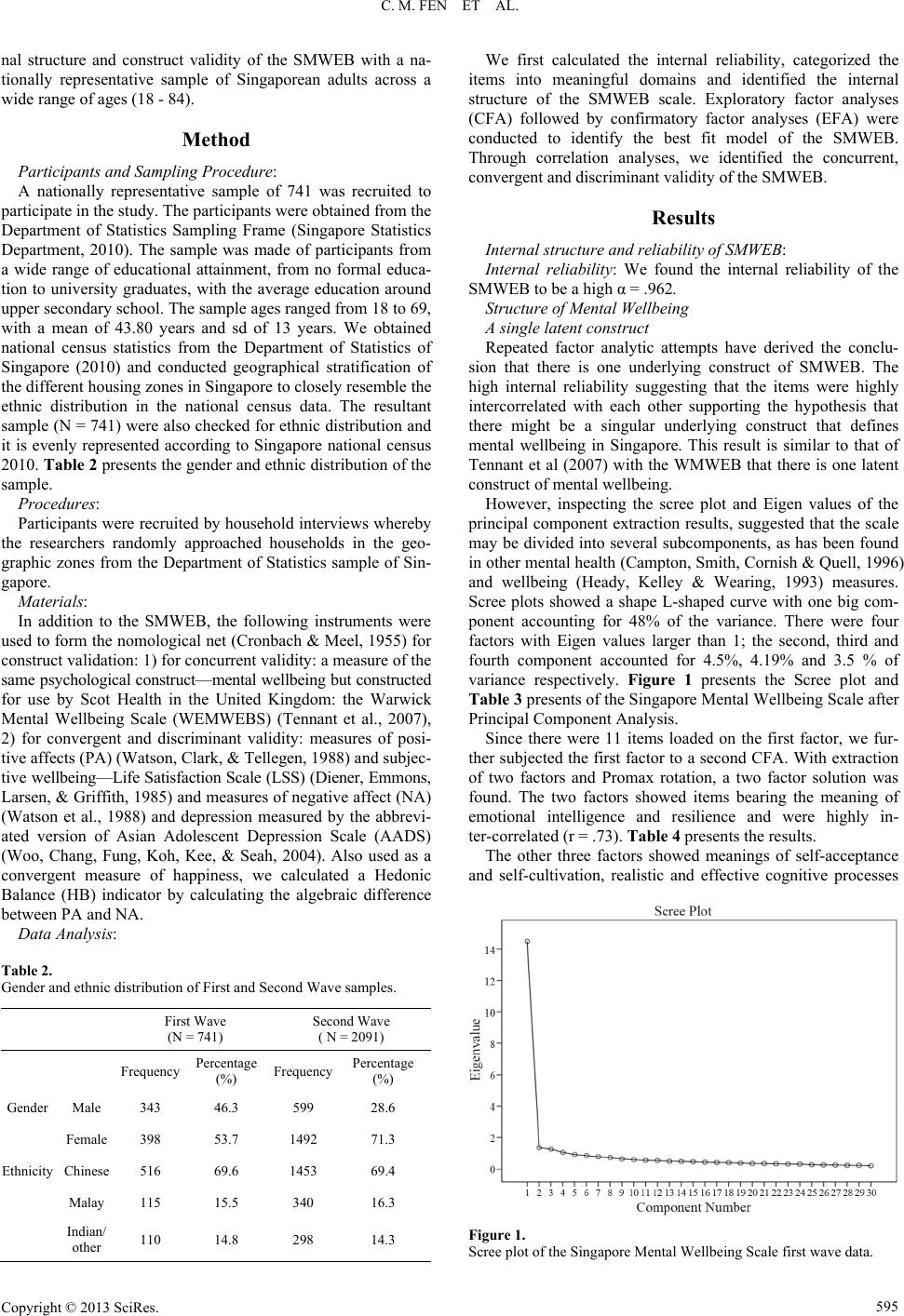

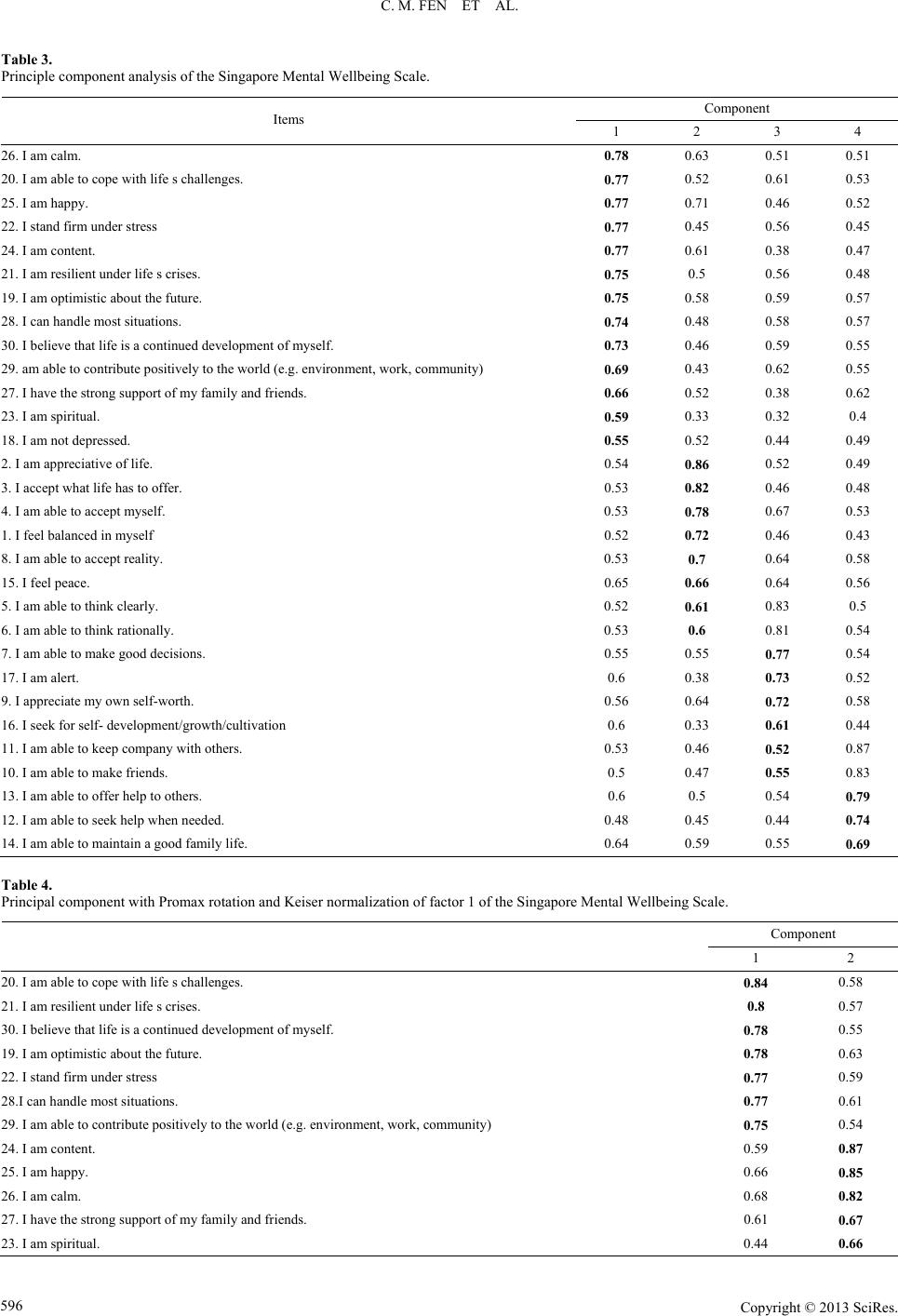

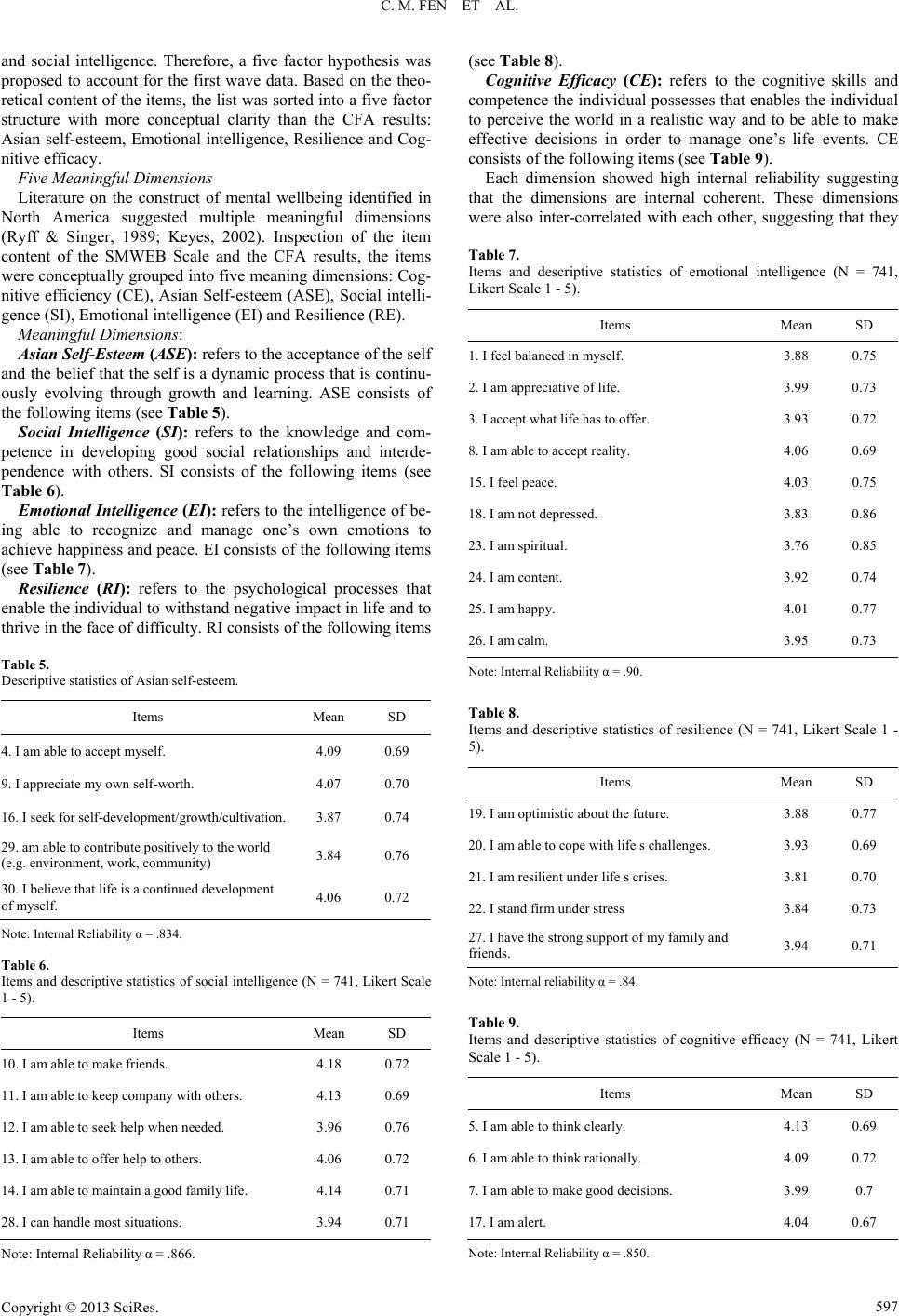

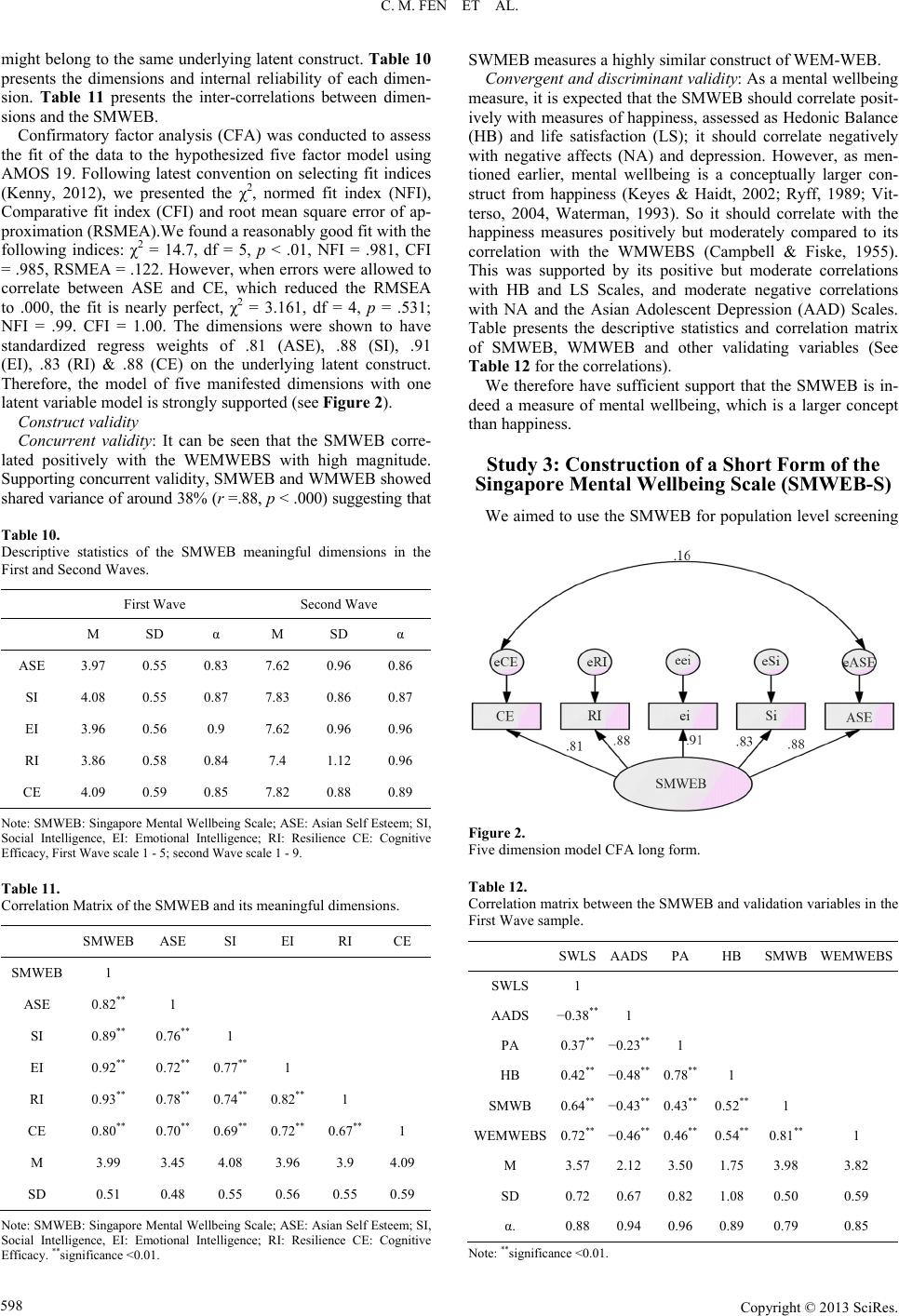

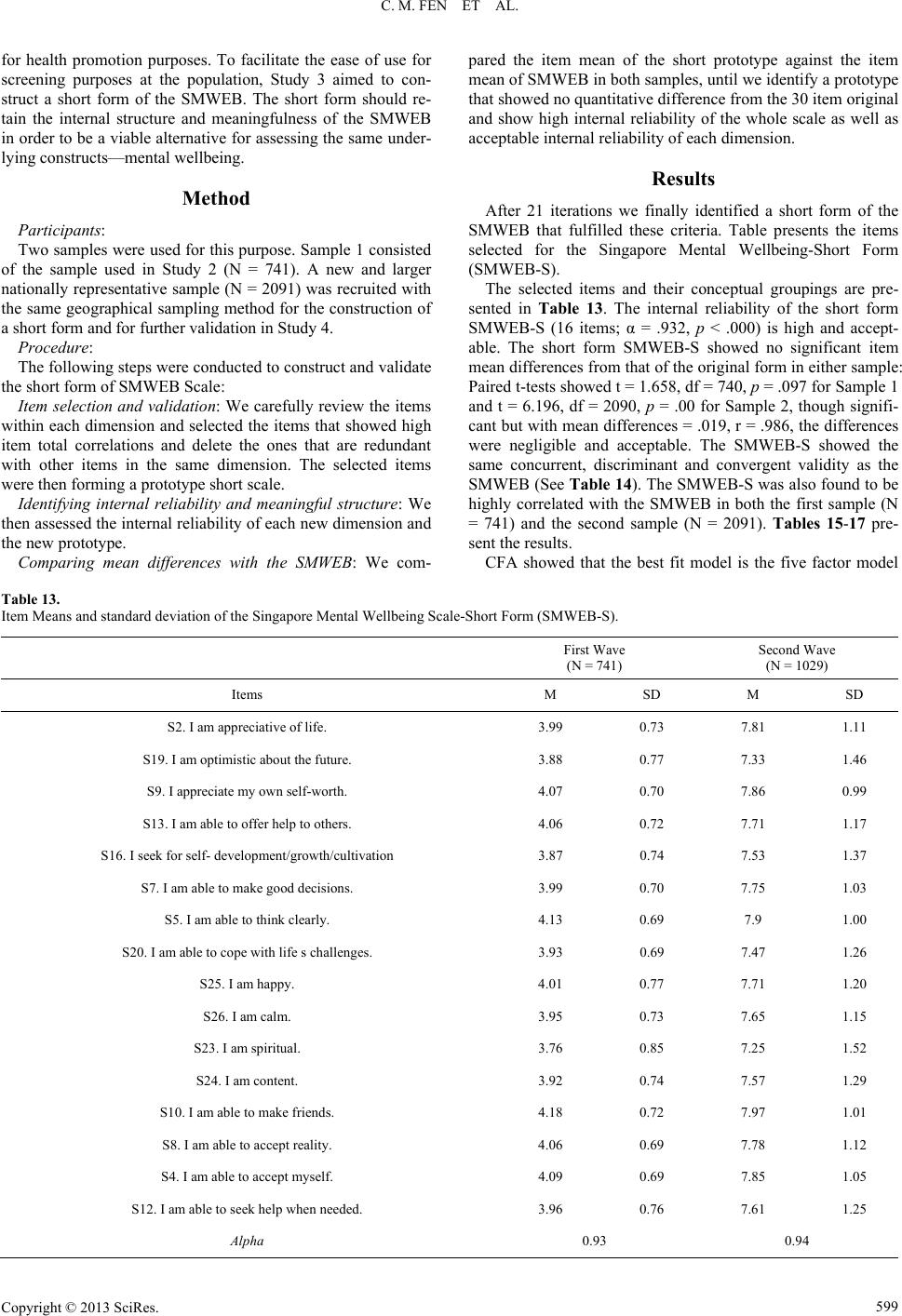

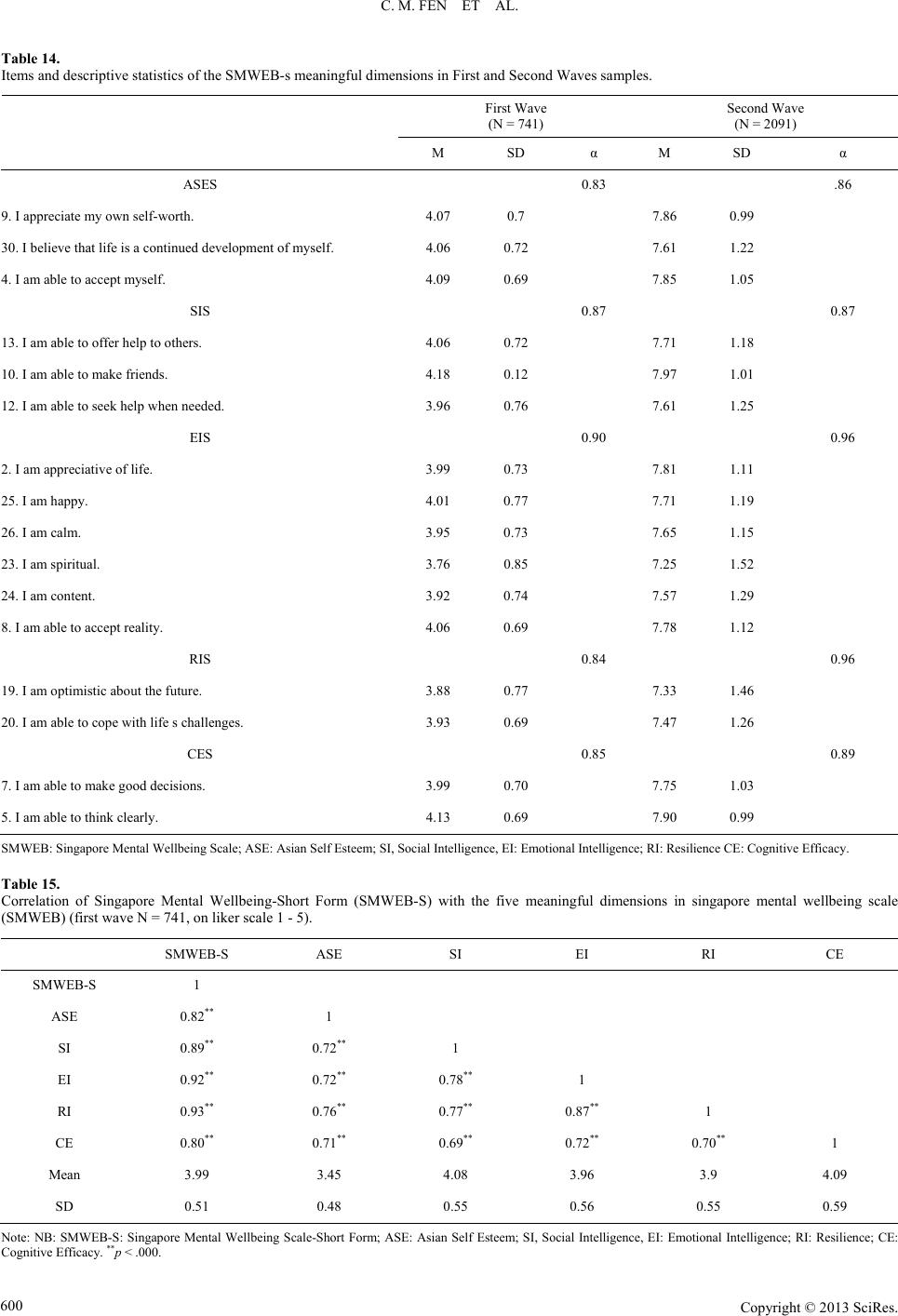

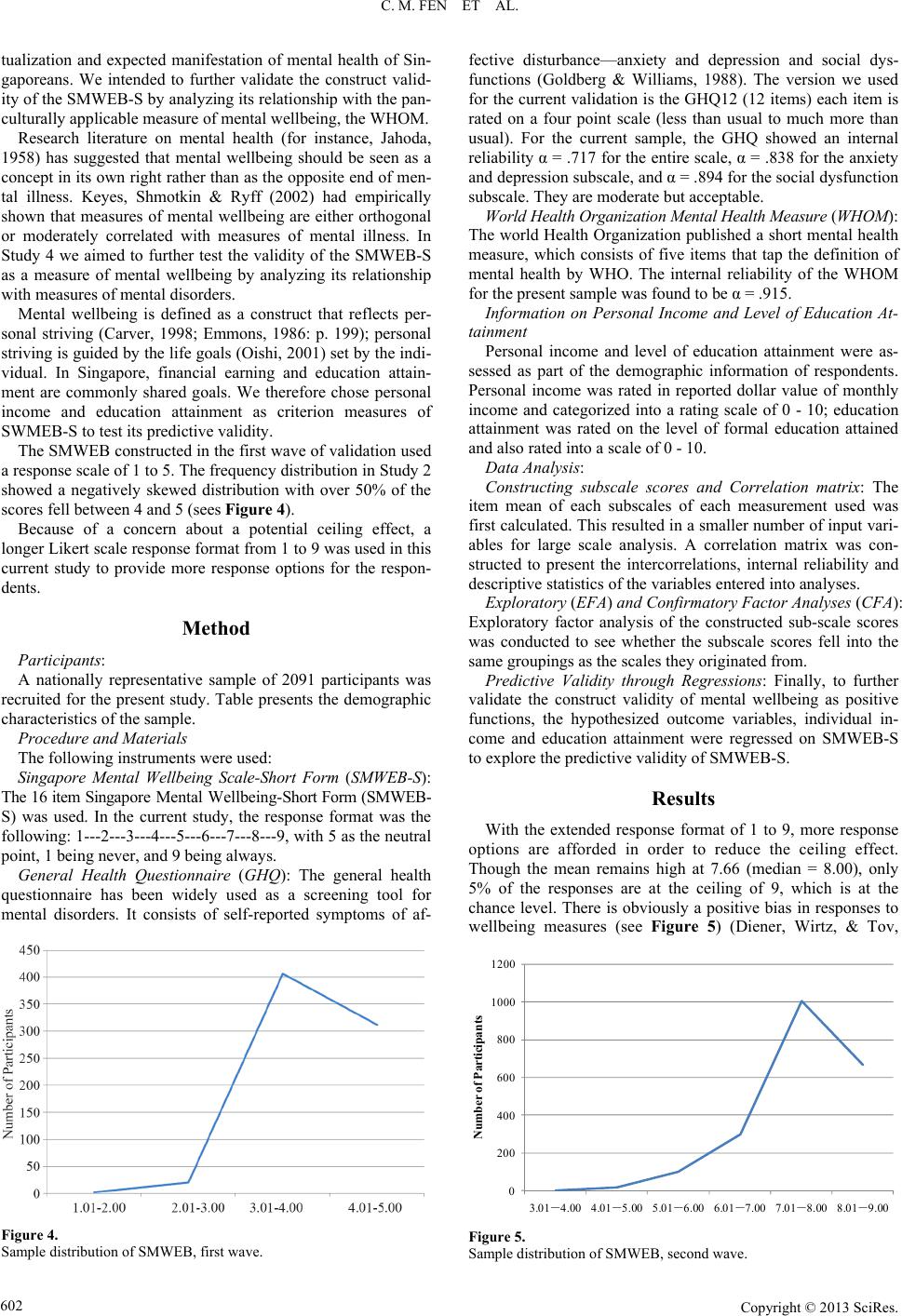

|