Theoretical Economics Letters, 2013, 3, 211-215 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2013.34035 Published Online August 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/tel) Social Welfare under Quantity Competition and Price Competition in a Mixed Duopoly with Network Effects: An Analysis* Yasuhiko Nakamura College of Economics, Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan Email: yasuhiko. r.nakamura@gmail.com Received May 6, 2013; revised June 6, 2013; accepted July 6, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Yasuhiko Nakamura. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In their recent work, Matsumura and Ogawa (2012) showed that in the context of a mixed duopoly, equilibrium social welfare is higher in price-setting competition than in quantity-setting competition. We found that when the strength of network effects is sufficiently high, the above result is totally reversed; thus, in a mixed duopoly, the presence of net- work effects weakens the superiority of price-setting co mpetition with respect to equilibrium social welfare. Keywords: Mixed Duopoly; Network Effect; Price Competition; Quantity Competition 1. Introduction This study compares equilibrium social welfare between price-setting competition and quantity-setting competi- tion in a mixed duopoly with network effects. The net- work effects that we consider in this paper were intro- duced in Katz an d Shapiro [1] and applied in Hoernig [2 ], Nakamura [3 ], and Nakamura [4]. These effects reflected a simple mechanism where the surplus obtained by a firm's client increases directly with the number of other clients of this firm. In this study, we show that when the strength of such network effects is sufficiently high, the equilibrium social welfare is higher in a quantity-setting competition than in a price-setting competition ; this find- ing is strikingly different from those in th e existin g litera- ture in this field including Ghosh and Mitra [5] and Ma- tsumura and Ogawa [6]. Although we can consider the European automobile industry as a representative example in a mixed oligopo- listic industry, as described in Katz and Shapiro [1], net- work effects as positive consumption externalities are likely to arise in the automobile market1. In such an in- dustry, foreign automobile firms’ sales may be less than expected because of the perceptions that consumers hold about the less experienced and smaller service networks of new or less popular brands. Thus, in a mixed oligop- oly, the presence of network effects as positive consump- tion externalities sh ould be analyzed since they influ ence the equilibrium market outcomes in both price-setting and quantity-setting competitions. By building a simple extention of the model from Ma- tsumura and Ogawa [6] in line with Hoernig [2], Naka- mura [3], and Nakamura [4], we find that a sufficiently high level of network effects reverses the ranking order of the equilibrium social welfare between price-setting competition and quantity-setting competition. Thus, when the strength of network effects is sufficiently high, the equilibrium social welfare can be higher in quantity com- petition than in price-setting competition, because the relatively large total output levels in the former yield a strictly positive influence on equilibrium social welfare in accordance with the sufficiently high level of network effects. Therefore, in a mixed market, the superiority of price-setting competition is weakened if network effects such as consumers’ expectations about each firm’s equi- librium market share are sufficiently strong. *We are grateful for the financial support by KAKENHI (25870113). All remaining errors are our own. 1As one example, a Spanish public-owned automobile manufacturer, SEAT competes with Volkswagen which is one of the most famous German private automobile manufacturers. In addition, Renault which is the most famous partia lly Fren ch public-owned fi rm compete s with many rivate firms in Europe. Recentl , Romanian private firm, Dacia merged with Renault, and it became a s econd marque for t h e Renault gr o up . See Barcena-Ruiz and Garzon [7] for other examples and detail discussions of the European automobile industry as a mixed oligopolistic market. 2. Model We formulate a mixed duopolistic model composed of one public firm and one private firm, with an additional term that reflects the network effects introduced in Katz C opyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  Y. NAKAMURA 212 and Shapiro [1] and applied by Hoernig [2], Nakamura [3], and Nakamura [4]. We assume that firm 0 is a welfare-maximizing public firm, whereas firm 1 is a pure profit-maximizing private firm. Similar to Hoernig [2], Nakamura [3], and Nakamura [4], firm faces a linear demand of the following form: i and 0,1;, iiij qanypbpi ij (1) where and are demand parameters. indicates the strength of network effects, and i is consumers’ expectations on firm ’s equilibrium mark et sh are. As explained in Hoernig [2], Nakamura [3 ], and Nakamura [4], the above demand system can be derived from the following quasi-linear concave utility function of a representative consumer: 0a 1 0,1b 0,n y i 22 001 01 0101 2 2 010101 01 2 ,;,11 21 ,, 1 aq qqq bqq Uqqy ymbb b ybyq ybyq nfy b y where m denotes the income of the representative con- sumer and represents some symmetric function of expectations. In this paper, in the same manner as in Hoernig [2], Nakamura [3], and Nakamura [4], we sup- pose that ,f 22 01001 1 ,221 2 yynybyyyb 2. The marginal cost of production of both firms 0 and 1 is commonly assumed to be c. The profit function of firm i is given by ii i , where i is given as (1)3. Consumer surplus is expressed as the representative consumer’s utility as follows: pcq ,0,1;iji j q 010100 11 ,;,CS Uqqyypqpq, whereas producer surplus is given by the sum of the profits of both firms 0 and 1, 01 . Finally, we sup- pose that social welfare is defined as the sum of consum- er surplus and producer surplus. We consider “rational expectations” to be a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium by imposing the rational ex- pectations condition that 00 yq and 11 à la Katz and Shapiro [1], Hoernig [2], Nakamura [3], and Naka- mura [4]. yq 3. Welfare Analysis 3.1. p-p Game In this subsection, we discuss the p-p game where firms 0 and 1 simultaneously choose their price levels. By considering y0 and y1 as given, public firm 0 maximizes the social welfare with respect to 0 whereas private firm 1 maximizes its profit with respect to . In this case, the social welfare is given as follows: p 1 p 0101 23 22 01 0 22 2222222 1100 01 2 2222 01 11 2 01 2 2101 2 ,;, 21 122 1 21 21 21 2 21 2 21 21 21 21 21 1. 21 Wppyy pbbcbpbp bp bb abpbpnyn ybnyy b bn y ynyn y b ab bcnyy b bcbpnyy b 1 Note that the term of the price level of firm 0, 0 is independent of the term of consumers’ expectations about the market share of both firms 0 and 1, 0 and 14. On the other hand, the profit of firm 1 is given as follows: p y y 1010110 11 ,;, .ppyypcabpp ny The respective reaction functions of firms 0 and 1, , are given as follows i r 0, 1i: 001 1 ,prpcbcbp (2) 11010 1 ;2prp yacbpny. (3) Note that the price level of firm 0 does not depend on consumers’ expectations about the market share of both firms 0 and 1 in its reaction function. We obtain the rational expectations Nash equilibrium outcomes by substituting the rational expectations assump- tion that 00 yq and 11 yq into Equations (2) and (3). The equilibrium market outcomes namely the output and price levels of firms 0 and 1, profit of firm 0, producer surplus and consumer surplus are given as follows: 01 2 01 22 11 ,, 12 21 ,, 22 pp pp pp pp abc abc qq nbn ab cbnabc ppc bn bn 2This assumption in the form of ,f i mplies that the representative consumer’s utility is the highest with respect to the consumption vector of the goods produced by both the public firm and the private firm, , when expectations are rational and correct. 01 ,qq 3We assume that 1>abc 4Thus, as described below, in firm 0’s reaction function,its price level does not depend on consumers’ expectations about the market share o both firms 0 and 1, and . 0 y1 y 0 in order to ensure the non-negati- vit of all e uilibrium outcomes. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  Y. NAKAMURA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL 213 2322 2 2 15 6232 . 21 12 pp CS abc bbnnb n m bnbn 2 02 22 2 2 1, 12 111, 12 pp pp ba bc nbn babcbb n PS nbn Furthermore, the payoffs of both firms 0 and 1 are given as follows: 234 2 2 2 17 22474 , 21 12 pp abc bbbnnb n Wm bnbn 2 12 2 1 2 pp abc bn 3.2. q-q Game social welfare with respect to q0 whereas private firm 1 maximizes its profit with respect to q1. In this case, the social welfare is given as follows: In this subsection, we discuss the q-q game where firms 0 and 1 simultaneously choose their output levels. By con- sidering y0 and y1 as given, public firm 0 maximizes the 222 01 001101 0101 2 22 00100011101 1 2 212 21 ,;, 21 222 22. 21 abqqqbqqq bcqq Wqqy yb nqybnq ynybnqynq ybnyyny b On the other hand, the profit of firm 1 is given as follows: 0101 10101 12 1 ,;, 1 abbqq bnyny qqyy qc b 11001 2001 ,, 11 qrqyy ab bcbqbnyny 2. (5) The respective reaction functions of firms 0 and 1, are given as follows : i r 0, 1i 2 001011 0 ;, 1qrqyy bcbqny 1 We obtain the rational expectations Nash equilibrium outcomes by substituting the rational expectations assump- tion that 00 yq and 11 yq into Equations (4) and (5), The equilibrium market outcomes including the output and price levels of firms 0 and 1, profit of firm 0, and consumer surplus are given as follows: 1abbny (4) 2 01 2 2 11 1121 ,, 21 211 qqqq qq ba bc babcbnn qq bnn bnnn 0 ,pc 10 2 2 2 2 2 1,0 21 11 , 21 qq qq qq abc pc bnn ba bc PS bnn , 222 23 2 2 115221212123 . 212 11 qq babcbnnbnbnnn CS m bbnn n Furthermore, the payoffs of both firms 0 and 1 are given as follows:  Y. NAKAMURA 214 22 24 2 2 174212124 , 121 1 qq abc bbnnbnnn Wm bbnn n 2 2 12 2 11 . 21 qq ba bc bnn On comparing the equilibrium social welfare between price-setting competition and quantity competition, we obtain the following result: 22 2422 2 2 22 14183483 0 22(1 )12 ppqq babcbnn n bnn WW bnnn bn 2 242 2 24 442 10,1,0,1. 33 bbb b nb bb Then, we obtain the proposition on the ranking order of equilibrium social welfare between price-setting com- petition and quantity-setting competition. Proposition 1 When the strength of network effects in a mixed duopoly is sufficiently high, that is, 242 224 >442133nbbbb b b 1 , the equilibrium social welfare is higher in quantity-setting competition than in price-setting competition; otherwise the opposite is the case. In Figure 1, the difference in the equilibrium social welfare between price-setting competition and quantity- setting competition is described. Surprisingly, Proposi- tion 1 implies that when the strength of network effects is sufficiently high, the result on the ranking order of the equilibrium social welfare between a price-setting com- petition and a quantity-setting competition obtained in Ghosh and Mitra [5] and Matsumura and Ogawa [6] is totally reversed; hence, the equilibrium social welfare can be higher in quantity-setting competition than in price- setting competition. The intuition behind this result is given by using the following lemma: Lemma 1 For the rational expectations Nash equi- librium in price and quantity competitions, the ranking orders of the equilibrium market outcomes are given as follows: 1) 001100 1 ,,,and pqqppqqqqppppq ppppqq qq and qq qqpppp qq qq q , 2) , 01 01 01 01 qq qqpp pp qq qq 3) and pqq qqpp PSPSCSCS. Note that the above equality of the price level of private firm 1 is satisfied only when 5. 0n From Lemma 1, even if network effects are introduced, the ranking orders of equilibrium outcomes except for the price level of firm 1 are the same as those obtained in Ghosh and Mitra [5]. The introduction of network effects widens the difference in the price level of firm 0 between price-setting competition and quantity-setting competi- tion, implying that such a low level of 0 creates a strong downward pressure on firm 1’s price level. Thus, when takes some sort of positive value, firm 0’s price level is strictly higher in price-setting competition than in quantity-setting competition. Therefore, in particular when the strength of network effects is sufficiently low, since the ranking order of the equilibrium market out- comes seldom changes against the introduction of net- work effects, the equilibrium social welfare is higher in price competition than in quantity competition owing to the large difference of the equilibrium producer surplus re lative to that of the equilib ri um consumer surplus, which is similar to Ghosh and Mitra [5] and Matsumura and Ogawa [6]. qq p n On the other hand, by following the formula of equi- librium social welfare à la Ghosh and Mitra [5], and by imposing the rational expectations condition that y0 = q0 and y1 = q1, we can represent the equilibrium social welfare as follows: 010011010 1 ,; ,,Wqqyqyqsqqdqq 01 01 2 01 2 01 01 11 where141, 141. qq abcqqb nq qb dq qnqqb As explained in Ghosh and Mitra [5] and Matsumura and Ogawa [6], on the basis of the facts that 0s and 0d , the effect of on the equi- librium social welfare outstrips the effect of 01 dq q 01 qq when 0n ; consequently, the equilibrium social wel- 5When , the fact that such an equality holds is indicated in Ghosh0n and Mitra [5]. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL  Y. NAKAMURA 215 Figure 1. Comparison of the equilibrium social welfare be- tween price-setting competition and quantity-setting com- petition. fare is higher in price-setting competition than in quan- tity-setting competition if no network effects are con- sidered. However, as becomes higher, in a quantity- setting competition, the positive effect of n 01 qq owing to on the equilibrium 01 01 qq qqpppp qq qq social welfare increases. On the other hand, the negative effect of owing to on the equilibrium social welfare decreases. Therefore, the degree of the strength of network effects, n, reverses the order of the equilibrium social welfare between price- setting and quantity-setting competitions. 01 dq q 01 01 qq qqpppp qq qq 4. Conclusions This study compared the equilibrium social welfare be- tween price-setting competition and quantity-competition in a mixed duopolistic market with network effects. In Ghosh and Mitra [5] and Matsumura and Ogawa [6], where network effect is not considered, it was shown that the equilibrium social welfare is always higher in price- setting competition than in quantity competition6. How- ever, in this paper, when the strength of network effects is sufficiently high, we found that the ranking order of the equilibrium social welfare between price-setting com- petition and quantity-setting competition is totally revers- ed. Thus, when network effects are explicitly considered, the superiority of price competition with regard to social welfare weakens in a mixed duopolistic market. Furthermore, by following Matsumura and Ogawa [6], where public firm 0 and private firm 1 can choose their strategic variables (i.e., their price leve ls or outp ut lev e ls ), even if the network effects are explicitly introduced, we obtain the same results as those in their paper. Thus, in the two-stage game wherein both firms 0 and 1 simul- taneously choose either their price contracts or their quantity contracts in the first stage, and accordingly en- gage in market competition in the second stage, we find that price-setting competition is a unique market compe- tition structure led by dominant strategies such that both the firms take the price contracts7. REFERENCES [1] M. Katz and C. Shapiro, “Network Externalities, Compe- tition, and Compatibility,” American Economic Review, Vol. 75, No. 3, 1985, pp. 424-440. [2] S. Hoernig, “Strategic Delegation under Price Competi- tion and Network Effects,” Economics Letters, Vol. 117, No. 2, 2012, pp. 487-489. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.06.045 [3] Y. Nakamura, “Capacity Choice in a Price-Setting Mixed Duopoly with Network Effects,” Modern Economy, Vol. 4, No. 5, 2013, pp. 418-425. doi:10.4236/me.2013.45044 [4] Y. Nakamura, “Endogenous Timing in Price-Setting Pri- vate and Mixed Duopoly with Network Effects,” 2013, Mimeograph. [5] C. Ghosh and M. Mitra, “Comparing Bertrand and Cour- not in Mixed Markets,” Economics Letters, Vol. 109, No. 2, 2010, pp. 72-74. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2010.08.021 [6] T. Matsumura and A. Ogawa, “Price versus Quantity in a Mixed Duopoly,” Economics Letters, Vol. 116, No. 2, 2012, pp. 174-177. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.02.012 [7] J. C. Bárcena-Ruiz and M. B. Garzón, “Mixed Duopoly, Merger and Multiproduct Firms,” Journal of Economics, Vol. 80, No. 1, 2003, pp. 27-42. doi:10.1007/s00712-002-0605-2 6Matsumura and Ogawa [6] found that the equilibrium social welfare becomes higher in price competition than in quantity competition re- gardless of the relation of goods produced by both the firms, that is, substitutable goods or complementary goods. 7Detailed discussions and proofs on the above are available upon re- quest. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. TEL

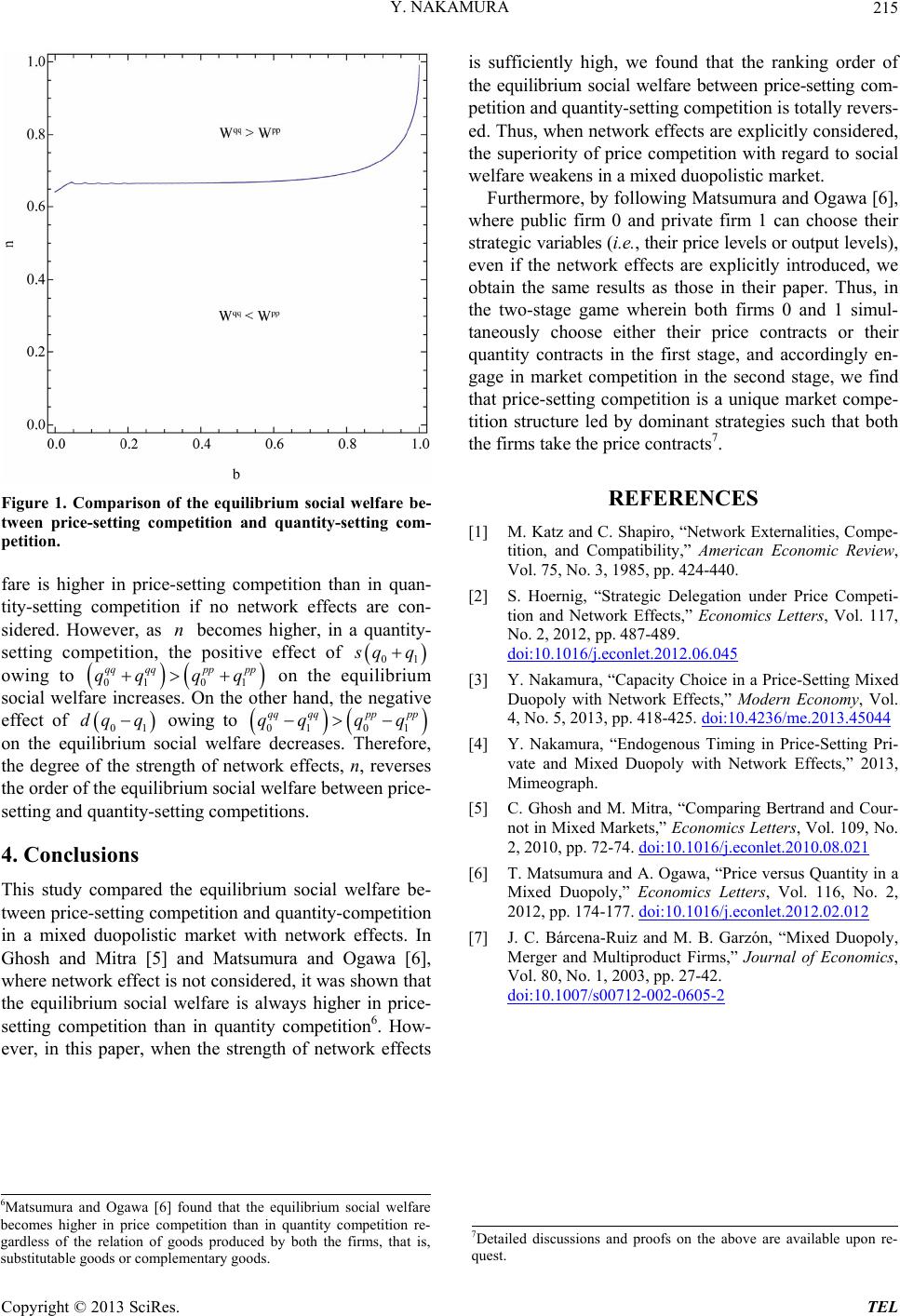

|