Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.7A1, 33-42 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.47A1005 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 33 Patterns of Variation: A Way to Support and Challenge Early Childhood Learning? —Concluding Reflections from Learning Study Projects Conducted in Swedish Early Childhood Education Agneta Ljung-Djärf1, Mona Holmqvist Olander Brante1,2, Eva Wennås Brante1,2 1Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden 2Department of Pedagog i c a l , Curricular and Professional Studies, Universit y of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Email: agneta.ljung-djarfkr.se Received May 17th, 2013; revised June 16th, 2013; accepted June 23rd, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Agneta Ljung-Djärf et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is pr ope rly cited. The purpose in this article is to elaborate on how the use of patterns of variation designed by variation theory can challenge and develop the early childhood education (ECE) practice. The analysis is based on six learning study (LS) projects conducted in Swedish ECE. A LS is a systematical, theoretical based de- velopment of teacher professionalism, often in close cooperation with researchers. The projects included 17 teachers, 140 children and 7 researchers. The video documented empirical material consists of 16 analysis meetings, 14 interventions and 407 pre-, post-, and delayed posttests. Each project is a concrete example of the use of patterns of variation to increase early childhood learning. In all cases a tendency of qualitative changes in children’s ways of discerning the object of learning could be noticed. The purpose is to search for how this can be understood from a variation theoretical perspective. The main focus is on changed ways of performing the interventions to search for how patterns of variation were used to create and capture the learning situations throughout the projects. One of our findings is that we have seen that it takes more than one intervention for the teachers to capture which aspects of the object of learning are critical in the targeted group, but as the iterative process allows them to try out the design more than once, they manage to find them. The second finding is that the teachers changed focus from taken for granted assumptions of each child to focusing on their own design to facilitate the child’s learning. Finally, the aspect supposed to be discerned has to vary against an invariant background to be discerned by the chil- dren, and to separate the principle from the representation is needed to be able to generalize their new knowledge. Keywords: Patterns of Variation; Variation Theory; Learning Study; Early Childhood Education Introduction The focus of this article is on how patterns of variation, based on variation theory (Lo, 2012; Lo & Marton, 2012; Mar- ton & Booth, 1997), are found to challenge and develop early childhood learning and development. Early childhood educa- tion (ECE) in Sweden is organized as pre-school for the 1 - 5-year-olds and a pre-school-class for the 6-year-olds. It is voluntary to attend but all children have the right to participate. It is free of charge 15 hours a week, if additional child care is needed it is coated with a cost. The first curricula, implemented in 1998 (Ministry of education and research, 1998), was influ- enced by a pre-school tradition inspired by Fröbel, who advised the teachers to follow the children’s interests and development without steering them (see e.g., Fröbel, 1995). There is also a clear connection between play and early childhood learning. The implementation of the ECE curriculum gave indeed status and legitimacy to the ECE practice and work, but, later on, the educational practice was also criticized not stimulating chil- dren’s learning systematically (The Swedish national agency for education, 2004). An ECE “doing culture”—with a main focus on what to do instead of what to learn—was in focus of such critique. So, in accordance with governmental suggestions (Memorandum U2008/6144/S, 2008) a new education act (Ds, 2009: p. 25) and a revised curriculum (The Swedish national agency for education, 2010) a clarification of the educational mission were made. The new content and learning objectives placed emphasis on literacy, mathematics, science, and tech- nology. ECE practices were also required to conduct systematic quality work including pedagogical documentation and evalua- tion. However, the implementation of new learning objectives has been a challenging task due to e.g. a lack of a ECE tradition aiming at specific learning objectives as well theoretical tools on learning to support such new requirements. The Swedish ECE practice of today is a high quality playful learning environment based on children’s perspective. It is an educational practice influenced by a valuable and internation- ally renowned ECE research approach as well as peddagogical tradition initiated primarily by professor Ingrid Pramling Sa- muelsson the, so called, developing pedagogy (se e.g., Pram- ling, 1994; Pramling Samuelsson & Asplund Carlsson, 2003;  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Pramling Samuelsson & Mårdsjö, 2007). A long and wide vari- ety of studies have been conducted demonstrating its positive impact on ECE practice and learning. Three main pedagogical strategies of the developing pedagogy is described as to: Create and capture situations around which children can think and speak; Get children to think, reflect and express themselves ver- bally and in other ways; Take advantage of the diversity of children’s ideas. Further on it is an approach where children’s meaning mak- ing and variation is central aspects. Variation from this point of departure implies that teachers illustrate children’s ways of thinking by focusing on different levels of generality and to address ways to understand a single learning object—both of the individual child, and the child group as a whole. Developing pedagogy takes advantage of children’s intentions and perspec- tives to capture and challenge the child’s world with the help of variation. Variation in this sense implies varied views of a phenomenon. The expressed variation, e.g. different ways of thinking and talking about the same phenomenon is used as an asset in making the children aware of a greater number of dif- ferent ways of understand something (Pramling & Pramling Samuelsson, 2011: p. 9). During the teaching and learning proc- ess, variation in this sense is seen as a rich resource at work for expanding children’s experiences of the world. However, from a variation theoretical perspective, variation has been given another meaning. An LS is a systematical plat- form to help teachers to put variation theory into practice (Lo, 2012; Lo & Marton, 2012). It is a model actualized in concrete teaching and learning situations by use of this specific theory of learning as guiding principle. The LS model is used to develop teacher professionalism; often in close cooperation with re- searchers (Holmqvist, 2011). During the past few years a proc- ess of trying out the LS model has been conducted in different educations settings around the world (Lo, 2012; Lo & Marton, 2012). LS has mainly been used in different primary or com- pulsory educational setting but has also, as mentioned, been tried out in ECE practices. Completed ECE LS projects (see e.g., Holmqvist, Brante, & Tullgren 2012; Holmqvist, Tullgren, & Brante, 2010; Landgren & Svärd, 2013; Ljung-Djärf, 2013; Ljung-Djärf & Magnusson, 2010; Ljung-Djärf, Magnusson, & Peterson, submitted) shows that the LS design may also fit into the ECE context but needs to be adjusted to suit the early edu- cation culture and context and young children’s conditions and needs. Four main features were a school based LS model and early childhood activity seem to have different points of views, are the approach to learning, ways of guiding the children, what content the teachers focus on and ways of assessing learning outcome (Ljung-Djärf & Holmqvist Olander, 2013). When hav- ing such features in mind a process of trying out a use of the LS model in ECE practice have shown that it is possible to apply and adjust to early childhood settings to deepen the teachers’ understanding about children’s learning (Holmqvist et al., 2010; Holmqvist et al., 2012; Ljung-Djärf & Holmqvist Olander, 2013) to change focus from doing to learning (Ljung-Djärf & Magnusson, 2010; Ljung-Djärf et al., submitted) but also an experienced professional development by participating in a LS project (Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2012). The ECE LS model developed in these projects implies some similarities compared with development pedagogy but also some differences. A main similarity is the base of seeing learn- ing from a learner’s perspective based on a phenomenographi- cal (Marton & Booth, 1997) point of departure. Both develop- mental pedagogy and the ECE LS model implemented in the projects uses interviews as a way to reveal and use children’s perspectives on their surrounding world when create and cap- ture learning situations. As a critical difference, though, appears the view of what variation and discernment entail (Pramling & Pramling Samuelsson, 2011: p. 9). The purpose in this article is to elaborate on how the use of patterns of variation designed by variation theory can challenge and develop the ECE practice i.e. especially regarding teachers’ readiness to create and stimulate learning situations. The research question is: What might patterns of variation designed by variation the- ory afford ECE practice? Initially, we will give a brief introduction to the theoretical point of departure, purpose, and design of the ECE LS model. The Theoretical Point of Departure of the LS Model; Variation Theory From a variation theory perspective learning is always learn- ing about something. In a LS this something is called the object of learning. An object of learning consists of many features. Such features have to be discerned by the learner if the com- plexity of a phenomenon can be understood. To a young child, this is obviously a long and extensive process based on con- tinuous experiences of different kinds and different contexts. Let us illustrate this with a very simplified example on a possi- ble object of learning; what is a dog? The phenomenon “dog” is defined by several features that cohesive defines it as a dog, i.e. the number of legs, the barking sound and shape of the paws. To fully understand what a dog is, assumes an understanding of the whole (“a dog”) as well as the parts (i.e., legs, sound and paws) and the relation between them. Lo and Marton (2012) claims that “There must be a whole to which the parts belong before the parts can make sense to us. We cannot learn mere details without knowing what they are details of” (p. 26). A feature, i.e., such as those mentioned above, is critical when not yet discerned by someone. A small child discerns a variety of living creatures as “a dog” before having discerned the specific features that defines a specific animal. Such specific features are i.e.; it is something that has four legs, barks and has paws. By that, whether an aspect is critical or not is determined in the relation between the phenomenon and a learner, or in other words it is a real critical aspect to that specific person (Olteanu & Olteanu, 2010). When an aspect is discerned by the learner it is no longer a critical aspect but an aspect defining the specific phenomenon. From a variation theoretical approach a way to experience differences between aspects or values or features of an aspect is to experience contrast, i.e., what something is and what something is not. To reuse the dog example this is about experiencing that a lot of animals have a similar shape of the body and the same number of legs (i.e., horse, cat and dog). So, to discern that there is a difference between the horse, cat and the dog a learner has to focus on something else i.e., the sound they are making. Such contrast can be discerned by experienc- ing a barking dog and a mewing cat simultaneously or being based on a memory of i.e., a mewing cat when hearing the bark of a dog. When contrasts are experienced it is possible to sepa- rate the aspect from the object it belongs to and focus on it. All aspects cannot be in focal awareness at the same time. A varia- tion of an aspect against a background of sameness can be at- tained through patterns of variation. Such variations can also be Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 34  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. attained by pointing out what something is by showing what it is not. The experienced variation enables thus a discernment of the critical feature from the phenomena, it stands out (Runesson & Mok, 2003) from the background and we can become focally aware of it. From a variation theory perspective, this implies to open a dimension of variation, by which critical aspects are made possible to discern. If we want to design a learning situa- tion on the sound of a dog in focus we have to open up a di- mension of variation that makes this aspect, and no other, pri- marily stand out against an invariant background. When we put the sounds of different animals in the foreground by varying only the sound we have varied sound against a background of sameness. Let us give another example based on the understanding of the shape of a cylinder. How can a situation that makes the shape of a cylinder standout be arranged? We can for example choose to illustrate the shape of by, as in the first example (Ta- ble 1), the use of cylinders in different sizes, or as in the second example, differently colored cylinders in the same size, or as in the third example, a blue cylinder and a blue cubicle in the same size. From a variation theoretical perspective is it essential to open up a dimension of variation that makes a potential critical as- pect, and no other, primarily stand out against an invariant background when designing a learning situation. Table 2 sum- marizes how the use of different aspects to appear as variant or invariant make different aspects to stand out, or in other words to appear as background respectively foreground. To make a feature stand out is from a variation theoretical point of view, a matter of not originates primarily from same- ness, but from difference. Learners are usually offered exam- ples that have the focused meaning in common, but differ oth- erwise as e.g., in Examples 1 and 2 above. Variation theory suggests that we turn this pattern around and let the focused meaning vary, while other things remain invariant as e.g. in example 3 above. By varying potential critical aspects they will stand out and afforded to be in focus of a joint discussion (see also Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2013). To summarize, learning can take place when critical aspects are discerned, which is made possible when a dimension of variation is opened around that critical aspect by a simultaneous Table 1. A summary of used concrete material in the three examples (Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2013) . Example 1 Example 2 Example 3 Table 2. Example on patterns of variation that makes different aspects to stand out (Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2013). Example 1: size stands o ut Example 2: color stands out Example 3: shape stands out Size Variant—different sizes Invariant—only one size Invariant—only one size Color Invariant—only redVariant—different colors (green and red) Invariant—only blue Shape Invariant—only cubicles Invariant—only cubicles Variant—different shapes (cubicle and cylinder) contrast of the aspects in the dimension of variation. But, how contrasts are designed for is not possible to tell without know- ing who the learners are. Lo (2012) highlights how intertwined critical aspects and features are, it is impossible for a person to discern a critical feature without knowing which critical aspect it relates to. Purpose and De sign of the ECE LS Model LS is a kind of action research that combines a theory on learning, variation theory, with the concept of the Asian model of lesson study (see e.g., Lewis, 2002; Yoshida & Fernandez, 2004). It is a model aiming to get teachers to learn in and from their own practice. In a LS project researchers and teachers work together as a team trying to collaboratively generate, share, develop and implement knowledge about learning with the aid of variation theory concepts and notion. By that, it is a process built up by a joint theoretical based reflection on the educational practice through research ventures. Educational practice in this context refers to the practice of teaching with respect to a defined content and in specific institutional settings. The process is organized in a structured and predetermined way (see e.g., Holmqvist, 2011; Häggström, Bergqvist, Hans- son, Kullberg, & Magnusson, 2012). Initially, there are two or three planning meetings to identifying of the object of learning and its critical aspects and ways of assess children’s learning. The object of learning is what the teachers and the children are supposed to focus on during the forthcoming activities. On one hand, a distinct object of learning affords an analysis of ways of discerning that specific object of learning from one delimited activity. On the other hand it is sometimes found as contradic- tive to traditional ECE practice. It has even been talked about as a risk that this way of working will result in a “fragmentatisa- tion of knowledge quite contrary to the preschool tradition” (Pramling & Pramling Samuelsson, 2011: p. 9). The identifica- tion of an object of learning is then followed by a process of screening, searching for possible stumbling blocks in how young children might discern this specific object of learning. The screening could be arranged as interviews, a practical task or an observation. The screening is aiming to reveal potential critical aspects (Olteanu & Olteanu, 2010) of the object of learning, i.e., features of the object of learning that seems to be difficult to discern. The screening is not a way to search for overall rules connected to stages of development in a specific age group but a way to coordinate children’s and the teachers perspectives related to a shared object of learning, enabling them to continue with their mutual learning activity. The in- formation from the screening is used when designing a “test”. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 35  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. As the term test is quite challenging in relation to the ECE practice it is important to emphasize that the construction and use of tests not is a way to assess the children based on estab- lished standards nor it is a way to evaluate and compare one individual with another. Instead, the term test in this context implies a way to catch sight of what the children as a group did seemingly discern related to a specific activity and object of learning and by that, give the teachers a clue on a possible way to create and capture challenging learning situations. In line with Swedish ECE practice and tradition interviews is a com- mon way to identify children’s ways of perceiving phenomenon in their surrounding world (se e.g., Doverborg & Pramling, 2000). During the ECE LS projects tests, mainly in the form of interviews, were used to identifying qualitative changes in how the children discern the object of learning before and after an intervention or learning activity. By that the development and evaluation of qualitative changes at a group level is used as a methodological tool to reflect on and develop practice further on. After the initial planning and identifying of the object of leaning and its potential critical aspects, described above, the subsequent project comprises commonly three cycles; each con- taining four specified steps. The cyclic process can be com- pared with the action research spiral, in which the reflection of the evaluation of the first action is the point of departure for further development. A LS cycle is organized as a pre-test, an intervention, a post-test and an analysis and planning meeting aiming to reflect on practice to further develop the practice in the next cycle (see Figure 1). The aim of such a process is to use teachers’ initial assumptions and existing values as point of departure to challenge and reconsider it by the use of evidence- based reflection. In other words, the model is about invention and re-invention of knowledge on teaching and learning. A Description of the ECE Learning Study Projects The analysis is based on six LS projects conducted in Swed- ish ECE. The projects analyzed in this study have used varia- tion theory as point of departure; beforehand when planning, during the interventions and after the interventions in discus- sions and evaluations. Teachers have thus been introduced to variation theory in a theoretical way but also by implementing the theory directly into their educational practice. Table 3 sum- marizes the objects of learning and participants in the cycles of each project. The empirical material is mainly video documented and con- sists in total of 16 meeti ng s, 14 in terventions, and 407 te sts in the form of individual pre-, post-, and delayed post-tests (Table 4). Figure 1. The design of the LS cycles (L ju ng- Djä rf et al., submitted). The tests were conducted in different ways. In project 1 and 2 the children were individually interviewed (Holmqvist et al., 2012). In project 3 all children were individually asked to an- swer three questions concerning where there were most items in diffe rent occasions with diffe rent materials (Holmqvist & Tull- gren, 2009). In project 4 the children were individually given a pile of wooden blocks and the teacher asked them to sort the blocks. The intension was to see if the children sorted them with shapes as a starting point (Landgren & Svärd, 2013). Pro- ject 5 used individual interviews based on concrete organic objects in different degrees of degradation (Ljung-Djärf & Mag- nusson, 2010; Ljung-Djärf et al., submitted). Finally in project 6, the tests had a written form and each child completed it by itself sitting together with their friends (Ljung-Djärf, 2013). In all cases qualitative changes in ways of discerning the object of learning were searched for. As the scoring was based on quail- tative assessments of the children’s answers, a preliminary as- sessment was first made of the children’s responses during the interview. After each session the video documentation was ana- lysed and the assessments were reviewed separately by two re- searchers. Table 5 summarizes the material used and how the tests were scored. The assessment of children’s learning is summarized quanti- tatively in Table 6. Table 3. Object of learning and participants in the projects. Teachers n = 17 Children n = 140 Researcher s n = 7 Project 1: whole and half 0 3 (4 - 6-yea r- ol ds) A & B Project 2: numbers and letters 0 3 (4 - 6-year-olds) A & B Project 3: more and most (in Swedish; most by size or number) 3 39 (4 - 5-year-olds)A & B Project 4: 3D geometrical shapes 4 25 (2 - 3-year-olds)A & C Project 5: organic decomposition 5 26 (4 - 5-year-olds)D, E & F Project 6: twice as 5 44 (6-year-olds) D Table 4. The empirical material. Meetings n = 16 Interventions n = 14 Pre-/post-/ delayed p os t t ests n = 407 Project 1: whole and half 0 1 3/3/0 Project 2: numbers and l etters0 1 3 / 3/0 Project 3: more and most 4 3 39/39/39 Project 4: 3D geometrical shapes 4 3 25/25/18 Project 5: organic decomposition 4 3 26/26/26 Project 6: twice as 4 3 44/44/44 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 36  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 37 Table 5. Used material and ways of evaluate the results. Material use d for tests Numbers of questions/score per question/m aximum score Project 1: whole and half Full, half, and quarter circles m ade of paper Open questions to ensure the children’s understan din g/ not q ua ntif ie d Project 2: nu mbers and letters 16 cards containing letters or numbers 16/not quantified Project 3: more and most Logic blocks, potatoes, nuts, sausages, meatballs, and bottles partially fille d w it h w ater 7/1 point/7 poin ts Project 4: 3D geometrical shapes Wooden blocks in four different shapes and colours No questions, 1 point if they sorted three blocks alike, tests were interrupted afte r 10 minutes Project 5: organic de composition Apple, bread, and leaf in different degrees of decomposition 9/each 0 - 2 points/18 points Project 6: twice as Printed booklet with drawn pictures illustrat ing four different respon se options f o r each question 7/each 0 - 1 point/7 points Each project has previously been analyzed and published separately, focusing either on children’s learning and/or teach- ers learning (see e.g., Holmqvist, 2011; Holmqvist et al., 2010; Holmqvist et al., 2012; Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2013; Ljung-Djärf & Magnusson, 2010; Ljung-Djärf et al., submitted; Ljung-Djärf, 2013; Landgren & Svärd, 2013), chal- lenges and possibilities when applying such a school generated process on pre-school context (Ljung-Djärf & Holmqvist Olander, 2013), the pre-school teachers views on being co- participants in a LS project (Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2012). A joint conclusion from all studies is the positive ex- perience teachers express of having a mutual understanding of theoretical concepts. This meta language functions well as a tool for reflecting together, develop the educational practice and challenge granted assumptions (Holmqvist Olander & Ljung-Djärf, 2012; Ljung-Djärf & Holmqvist Olander, 2013; Ljung-Djärf et al., submitted). Analysis This is a qualitative re-analysis based on six ECE LS projects conducted by a Swedish research group to find out in what ways patterns of variation have impact on children’s learn- ing.The first study was conducted in 2008 and the last in 2011. Participating teachers and researcher have made an intense and impressive work, during a process of collective analysis of the educational practice. In all cases qualitative changes in chil- dren’s ways of discerning the object of learning could be no- ticed. The purpose of the meta-analysis is to search for in what ways the used patterns of variation have been used to make this change possible. Throughout this process the verbatim tran- scripts and results of each of the LS projects and the original video recordings were studied and re-analysed in relation to each other, rather than individually, to find the important fea- tures. To be able to grasp the extensive material we have mainly focused on in what ways aspects of an object of learning has been offered the children by the use of patterns of variation. The process of analysis can be described as interplay between empirical data and the variation theoretical perspective. Such process of abduction implies an interpretation of data and de- vise of a theory to explain them. The interventions were de- signed from a variation theoretical point of departure to high- light potential critical aspects and to assess qualitative changes in children’s ways of discerning such critical aspects before and after the activity. Changed ways of discerning has then been related to the theoretical intensions. Results Each of the six LS projects is seen as evidence based docu- mentation on how the use of patterns of variation as a peda- gogical tool developed the ECE practice. From the results of the conducted LS projects an analysis of the patterns of varia- tion has been done. The results include a description of the LS cycles and their patterns of variation. Analysis of Patterns of Variation: Whole and Half In this first part of the pilot study three children participated, aged 4, 5 and 6 years old. The study was aiming at a detailed study in what ways patterns of variation could be used in teaching children the object of learning whole and half. By the use of variation theory, the aspect kept invariant was dividing an object into two similar parts, halves, and the aspect kept varying was the items used. By that the children were offered to discern cutting apples, pears and cakes into halves. The alterna- tive would have been just cutting e.g. apples into halves as- suming the children will understand and generalize to other objects as soon as they have been taught the concept half. However, the results show that children do not put the same meaning into the concept half as thought; instead they under- stood half as something cut into pieces, no matter how many. By that they were not sure how many halves a whole pear or cake could be cut into, even if they have discerned that an apple was cut into two halves. If we have not taken into consideration the difficulty for children to transfer their experience of cutting into halves for one representation to another, their understand- ing that a whole apple which were cut in two halves might only be right concerning apples and maybe not for any other item. Analysis of Patterns of Variation: N um bers and Letters The second part of the pilot study with three children aged 4, 5 and 6, was about the difference between numbers and letters. This was made to see what patterns the children would notice by themselves without teaching. They sorted cards in a discus- sion-like observation. As in the study above, the material used and the design was based on variation theory. Tolschinsky’s (2003) results showed that children from several different  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Table 6. The assessment of the children’s learning (mean results, pre-/post-/ respectively delay e d posttest). Cycle A Cycle B Cycle C Project 1: whole and half Not quantified Not quantified Not quantified Project 2: numbers and letters Not quantifie d Not quantified Not quantified Project 3: more and most 3.7/4.3/ 4.7 3.5/4.8/ 4.9 5.3/5.9/5.9 Project 4: 3D geometrical shapes 1.3/2.5/4.5 1.7/1.7/2.2 1.0/1.2/2.6 Project 5: organic decomposition 7.9/8.9/8.9 6.6/6.8/8.0 8.5/10.9/11.7 Project 6: tw ice as 1.4/1.7/1.4 1.2/1.3/1.8 0.7/2.1/2.2 countries could differ between numbers and letters. The chil- dren got cards with numbers (single figures or numbers) and letters (single letters and words) which de were told to sort in any way they wished. On the number cards, decimal point and minus were also introduced. The results show that the children noticed features of both numbers and letters, and could sort them into two different heaps. However, as they also got cards with the figure 0 and the letter O, they were confused and made one heap with cards containing 0 and O. This feature seemed to be important for them, but the decimal point and minus sign were not mentioned or noticed at all by any of the three chil- dren. The pattern of variation used was to keep letters and fig- ures at different cards, but varying how they were presented as single letters/figures or words/numbers. Analysis of Patterns of Variation: M ore and Most To teach children (n = 39) the difference between more and most regarding how many, a study including three interventions in three different groups of children were implemented. The results show that the third group got the highest scores, based on how they have responded regarding where there are most (regarding highest number) in an interview where they have met e.g. four ordinary sized sausages and five very small sau- sages, or three filled bottles compared to five empty bottles and so on. The items were by that designed based on variation the- ory, as the critical aspect was to separate between how many and how much which the questions were all about. During the interventions, the pattern of variation was changed as shown in Table 7. In the first session, everything varied, such as the ob- jects used (dolls, wooden blocks, teddy bears and so on), the size of the obj ect a nd the mat erial (plastic dolls, cloth dolls etc.). In the second, the objects were the same; teddy bears, but still the size differed as well as the focused aspects. In the second session, the teacher also started to talk about if the teddy bears were friends or not, if they had quarreled and were angry at each other during the comparison between how many and how much, which started a discussion about the teddy bears’ human behaviors instead. To avoid this, the teachers changed pattern of variation in the third session, and used cotton wool which could be divided into smaller parts or put together into bigger parts. In this session, only the size varied at the same time as the object (cotton wool) and material (cotton wool) was invariant. Table 7. Used patterns of variation in project 3 on more and most. Cycle A Cycle B Cycle C Objects Variant—dolls, wooden blocks, teddy bears etc . Invariant—teddy bears Invariant—cotton wool Material Variant—plastic, cloths, wood etc Invariant—cloth Invariant—cotton wool Size Variant—different sizes Variant—different sizes Variant—different sizes Analysis of Patterns of Variation: 3D Geometrical Shapes In this project patterns of variation were used to make 3D geometrical shapes to be in focus. As the children (n = 25) were quite young (2 - 3-year-olds) this was indeed a challenging task. Landgren and Svärd (2013) report that the joint discussions, theoretical reflections and analysis shaped three somewhat different learning situations. The first one started with teachers giving each child four blocks of different shapes and different colors. When the children had all four blocks at the same time it was hard for them to know what they should focus on (colour or shape), too much varied, and they saw shapes in general instead of discerning the critical aspect that separates a cubicle from a cylinder or cone. Of course the children saw that the blocks were differed, the aspect shape was not the only one that differed. At the second learning situation the teachers gave the chil- dren one shape after another, all of natural wooden. They talked about the shapes of the blocks, but made no comparison be- tween the different shapes. The teachers had made four robots of paper board and tinfoil, one in each shape (as shown in Fig- ure 2). The robots’ mouths were also shaped as the block; that is, the cylinder robot had a round hole as mouth and the cubicle robot had a square as a mouth. Now the teachers told the chil- dren that the robots could only eat blocks shaped as them, could the children feed the robots with the right block? This activity was designed to direct children’s attention to- wards the shape of the block they held and, actually, to trans- form a 3D-experience in their hands to a 2D pattern—the mouths, quite a challenging task for such a young child. The teachers noticed in their reflection afterwards that they had talked more about food than discussing why or why not a shape fitted into a mouth. Their focus had been on the process, feed- ing the robots and making the robots human-like; and by that leaving the object of learning (shapes) in the background. They thus understood that they could improve this situation even more. The third learning situation started in the same way, each child got a shape one at a time, but this time, when each child had all four, teachers initiated a discussion about what differ- ences and similarities could be found between the blocks. Then the robots arrived and were fed. Finally, a suitcase was brought in with empty tins, boxes and things like that. The children and teachers helped each other to order the objects in front of a robot; the cans in front of the cylindrical robot and so on. In this study, the teachers used robots to make the children match the shape of the cubes with the mouths of the robots. This is an example of how teachers usually use imagination and play in an ECE learning situation. However, in this case it can be ques- tioned if it would not be more featable to do holes in a paper Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 38  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Figure 2. The robots used in cycle second and third intervention (Landgren & Svärd, 2013). instead of feeding robots. By that the risk of seeing the robots hunger as main activity will be avoided and more focus kept on the shapes. Analysis of Patterns of Variation: Organic Decomposition From the initial screening in this project two potential critical aspects were chosen to be in focus; 1) the decomposers break down and convert organic matter, and 2) is a perpetually ongo- ing process. The matter discussed in the LS project group was how we could design a situation to make such an object of learning discernible to be used as point of departure in further discussions. Our first approach was to use a sort of play and drama frame and from that starting up a discussion and reflec- tion on what would happen to a bag of waste (fresh, organic as well as inorganic items) when left in the forest. The children made suggestions as i.e. it will be eaten by a bird or taken by a gobbling. As we wanted to direct the attention towards decom- posers, as e.g. mould, we decided to use different sorts of or- ganic partly decomposed objects as point of departure during the next intervention. Nor this illustration seemed to draw chil- dren’s attention toward the object of learning. In the last activi- ity we used one sort of organic object in different levels of de- composition (fresh, mouldy, soil) at a time. This time the chil- dren seemingly discerned the mould and this could be used as a point of departure during a joint discussion and reflection. The used patterns of variation are summarized in Table 8. When using only fresh items (as in cycle A) or partly de- composed items (as in cycle B) it was, more or less, taken for granted that the children would discern the defining features of decomposers and the on-going process of decomposition by an abstract reflection in the group. It was also taken for granted that the children had and could make use of previous experi- ences of degrees of decomposition of organic items. During this two cycles the teacher kept the focused features, fresh objects (cycle A) respectively partly decomposed objects (cycle B) invariant and varied other out of focus aspects (e.g., different fresh pic-nic objects and different partly decomposed fruits, vegetable and sticks). According to variation theory this is not the best way to do it. During cycle C, the object (e.g., tomato) was kept invariant and instead the rate of degradation varied, the on-going process of degradation became in focus. This group made use of an illustration that did afford an experience of contrast related to the on-going decomposition process si- multaneously. When the teachers in intervention C posed the question “What is the difference between the tomatoes” the idea was to use simultaneity as a tool to direct focus on contrast of a the difference between a fresh tomato and a partly decom- posed one (see Figure 3). This was then used as basis for joint reflection in the group. As mentioned above, from a variation theoretical perspective meaning derives from difference, not sameness. By letting one value in the same dimension of variation (degradation) was brought in focus the learners were able to experience such dif- ference. Even if difference can be discerned by the aid of memories and earlier experiences it cannot be taken for granted that a small child has such experiences and are able to remem- ber and can make such connections all by themselves. Analysis of Pa ttern s of V ari ation: Twice as The initial screening showed that the understanding of “twice as” as “one more” was a common way to make sense of the concept. Potential critical aspects seemed to be aware of the relation between the initial amounts to be able to determine what twice as something is. During the interventions different representations, appearances of the representations and way of illustrating the object of learning were made to be variant or invariant during the three interventions trying to make the con- trast of the previous identified critical aspects of object of learning, twice as, stand out in the learning situation. During the first activity there were examples using natural coloured wooden blocks as illustrations and there were other examples using amounts of children to illustrate the initial amount as well as twice as. The focus was on twice as in the sense of twice as many. During cycle B the group used wooden blocks and tried to exemplify twice as by using a variation of examples (twice as; high, long, and many). Lastly, during the third cycle, they tried to illustrate and challenge the fact that one has to focus on the initial qua ntity to be able t o say any thing about if some th ing is twice as by the use of a variation of appearance (blue and red) of used representations (pieces of LEGOTM). By that the teacher could initiate a joint reflection on the initial quantity and twice as by being illustrated simultaneously. Table 9 summarizes the used patterns of variation. In cycle A and B we tried to use a variety of examples of twice as. During the last intervention (cycle C) it was decided to use only a few examples but to try to clearly illustrate the relation between the initial quantity and twice as by using two Figure 3. The teacher and the children in group 3, project 4, examine and discuss the differences between the tomatoes. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 39  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 40 Table 8. Used patterns of variation i n p roject 4 on organic decomposition. Cycle A Cycle B Cycle C Representations Variant—different sorts of organic an d inorganic objects Variant—different sorts of organic objects Invariant—one sort of organic object at a time Level of degra dation Invariant—all obje cts were freshInvariant—all obje cts were partly decomposed Variant—different levels of decomposition (fresh, mouldy, soil) Table 9. Used patterns of variation in project 6 on the concept twice as. Cycle A Cycle B Cycle C Objects Variant—in some examples wooden blocks and in some example s a number of children Invariant—only wo oden blocks Invariant—o nly pieces of L EGOTM Meaning Invarian t — on l y twice as man y Variant—twice as many, long, highInvariant—only twice as many Appearance of objects illustrating the initial sum respectively twice as Invariant—the appearance of woode n locks respe ctively childre n w ere the same illustrating the initial am o unt or twice as Invariant—the appearance of the wooden bl ocks was the same either illustrating the initial amount or twice as Variant—blue and red pieces of LEGO™ and a two colored paper were used to separate the initial amount and twice as simultaneously coloured LEGOTM pieces. Relating to what was said before, such way of arrange the situation could be said to, from a varia- tion theoretical perspective, confuse the children as both colour and quantity was varying. But instead it was found to make the object of learning clear and discernible. How can this be under- stood from the theoretical perspective? The first intervention assumed, or even took for granted, that the children easily or automatically discerned the main prince- ple of twice as more or less by the teacher using the concept twice as and showed some examples. By the use of generaliza- tion the teacher tried to visualize that the same principle is ap- ply able to different representations (wooden block and chil- dren). In line with the theoretical perspective the analysis sug- gests that it is basic to initially focus on differences rather than sameness as generalization cannot help the learner if they have not captured what is critical. Figure 4. The material used in cycle C. During the second intervention (cycle B) the natural coloured wooden blocks were used to make the children to separate an initial quantity from twice as the initial quantity by discerning these simultaneously. However, it became quite messy on the floor when a lot of wooden blocks were placed out in a some- what unstructured way. It was not easy for the children to separate which wooden blocks illustrating the initial quantity and which were illustrating twice as and on the behalf of this also difficult to discern the contrast between the initial quantity and twice as. When the teacher were talking about twice as many, long and high at the same time it also might have con- fused some of the children. Due to the variation theory it is crucial to let only one aspect related to the object of learning vary at the time as more may mess up the possibilities to dis- cern what is intended to discern. By using such varied appearance of the pieces of LEGOTM it was also possible for the teacher to direct the children’s focus towards the relation between theses quantities by the use of well-known terms (blue and red). Previously discerned colours helped this six-year-olds to discern the contrast between the initial amount and twice as. During this intervention generali- zation in terms of to generalise what “twice as” means, no mat- ter of an original amount, is made discernible. According to the test-results this seemed to be successful. By testing to vary the representation, and then the meaning of twice as (number, size and so on) they finally found that to separate the original amount from twice as by the use of different colours was nec- essary to make the children discern the relationship between the original amount and twice as. Thus has also been found in an- other study about halfing and doubling of numbers (Holmqvist Olander & Nyberg, in press). In the third intervention we used both invariation in repre- sentations (pieces of LEGOTM) and the way of illustrating twice (only twice as many) but variation in the appearance of the LEGOTM pieces (blue and red) together with a two coloured paper to separate the initial quantity from the quantity of twice possibly to discern simultaneously but also to make the contrast between the both visualized and clear (see Figure 4). Patterns of Variation a Way to Support and Challenge Early Childhood Learning? The purpose of this article has been to elaborate on how the use of patterns of variation designed by variation theory can  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. challenge and develop ECE practice. In summary, patterns of variation seem to have something to offer when it comes to a conscious creation and capturing of situations around which children can think and speak. Instead of focusing on the child’s individual development, the focus is on the object of learning and the handling of it to facilitate learning for the child. This means the teachers do not judge the children’s behavior or abilities; instead they try to change the learning situation in a way making all children discern what is going to be taught or developed. By that, the way of using patterns of variation, the teachers professional development gain by giving them a tool to use in future learning situations with other children as it is re- lated mainly to the object of learning and minor to a specified child. The analysis has shown that a joint reflection on used patterns of variation shows qualitative changes in the children’s ways of discerning the object of learning before and after an intervention. The teachers seem to have a developed ability to sharpen the use of illustrations to make a potential critical as- pect to “stand out”. This has been noticed in all projects, for example project 3, cycle A, when the project group strived against not letting everything vary simultaneously as, from a variation theory perspective, all aspects cannot be in focal awareness at the same time. Or in project 4 when the illustra- tions in cycle C made the degradation process as on-going stood out from the illustrations of organic objects in different degrees of degradation. In this case, the experienced variation enabled a discernment of a potential critical aspect, or in other words it stood out from a background of sameness and the children became focally aware of it. The need of a conscious use of simultaneity in the concrete situation has also been high- lighted. From a variation theoretical perspective contrast can be used to make the children experience what something is and what something is not by offering aspects that are in some kind of relation to each other simultaneously (Lo, 2012; Lo & Mar- ton, 2012). Such an example is to let the children see the origin- nal amount together with the new amount when learning how to double, instead of letting the original amount disappear during the instruction (see Figure 4). This can be done in the concrete situation or based on a previous experience and memory, if the teacher really knows that the child really has such experience. When analyzing the initial intervention of the projects it was clear that the te achers in many cases took for grante d and base d on a presumption of previous experiences of these young chil- dren. This could be seen i.e. in project 4 when only fresh ob- jects (cycle A) respectively only partly decomposed objects (cycle B) were used as illustrations. On behalf of this we will argue on the need of the teacher taking the responsibility to afford experiences of “critical features simultaneously” (Lo, 2012: p. 61) and use such experiences afforded in the concrete situation as basis for discussions instead of leaving to the chil- dren to create simultaneity by her- or himself. Further on, the projects have also pointed at the need to challenge the chil- dren’s learning by a conscious use of separation to make the child able to generalize as a way to contribute to create a pur- poseful educational practice. This was intentionally used in the first study by the use of different representations (apple, pear, cake) to make the children aware of that half is not related to a specific object, no matter what object a whole always become two identical halves. To understand this, the child has to sepa- rate what half is from the object and develop a general idea instead. In the sixth study, the children got several different amounts to work with, to make them separate what twice as many are from the amount. No matter what the amount is, they have to generalize the assumption that it takes the same amount once and once again to get twice as much. The analysis have highlighted and exemplified how the par- ticipating teachers’, as the ECE LS projects progressed, created and captured ECE learning situations in a new and, seemingly, more carefully considered way at least regarding the design of the patterns of variation. This new way was not about “using variation between one particular object of learning and another as a means of helping the learner discern and hence understand this object of learning in a particular and singular way” (Pram- ling & Pramling Samuelsson, 201 1: p. 9) but to use such knowl- edge when creating and capturing learning situations might challenge, and a joint reflection on a potential critical aspect can make great differences. While creating patterns of variation in this way, they supported the children to discern something potential critical in this joint reflection rather than focused at the child’s behavior as such. By that, they sharpened their focus on learning content and consciously used children’s meaning making as an indicator of potential critical aspects when creat- ing and capturing learning situations. As far as we have found, this is a substantial contribution to coordinate the children’s and teacher’s perspective to a shared object of learning, enabling them to continue with their mutual learning activity. One of our findings is that we have seen that it takes more than one inter- vention for the teachers to capture which aspects of the object of learning are critical in the targeted group, but as the iterative process allows them to try out the design more than once they manage to find them. The second finding is the teachers chan- ged focus from taken for granted assumptions of each child to focusing on their own design to facilitate the child’s learning. Finally, the aspect supposed to be discerned has to vary against an invariant background to be discerned by the children, and to separate the principle (e.g., to half or double) from the repre- sentation is needed to be able to generalize their new knowl- edge. However, the results is limited to the six studies reported in this article, and the findings need to be supported in further projects focusing more on the explicit use of patterns of varia- tion to further on expand the knowledge of what the use might afford early childhood learning and development. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the participating teachers who gen- erously shared their time and teaching, and our research team Learning Design (LeaD) at Kristianstad University, Sweden, for encouragement and support. REFERENCES Doverborg, E., & Pramling, I. (2000). Att förstå barns tankar: Kommu- nikationens betydelse [Understanding children’s thoughts: The sig- nificance of communication]. S t oc kh o lm: Liber. Ds (2009). Den nya skollagen: För kunskap, valfrihet och trygghet [The new Education Act—For knowledge, choice and securi ty]. Fröbel, F. (1995). Människans fostran [Human education]. Lund: Stu- dentlitteratur. Häggström, J., Bergqvist, M., Hansson, H., Kullberg, A., & Magnusson, J. (2012). Learning study—En guide [Learning study—A guide]. Gothenburg: Gothenburg Un iv ersity. Holmqvist Olander, M., & Ljung-Djärf, A. (2012). Using learning study as in-service training in preschool. In J. Sutterby (Ed.), Early education in a global context: Advances in early education and day care (Vol. 16, pp. 91-108). Bingley: E merald. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 41  A. LJUNG-DJÄRF ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 42 Holmqvist Olander, M., & Ljung-Djärf, A. (2013). Theoretical appro- priation in pre-school teachers’ expressions after in-service training. Creative Education, 4. Holmqvist Olander, M., & Nyberg, E. (in press). Learning study guided by variation theory: Exemplified by children learning to half and double whole numbers. International Journal of Research in Early Childhood. Holmqvist, M. (2011). Teachers’ learning in a learning study. Instruc- tional Science, 39, 497-511. doi:10.1007/s11251-010-9138-1 Holmqvist, M., & Tullgren, C. (2009). Pre-school children discerning numbers and letters. Forum on Public Policy. http://forumonpublicpolicy.com/spring09papers/archivespr09/holmq vist.pdf Holmqvist, M., Brante, G., & Tullgren, C. (2012). Learning study in pre-school: Teachers’ awareness of children’s learning and what they actually learn. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 1, 153-167. doi:10.1108/20468251211224190 Holmqvist, M., Tullgren, C., & Brante, G. (2010). Using variation theory to analyze what preschool children experience exemplified by wholes and parts as the object of learning. In J. V. Carrasquero, M. Holmqvist, D. McEachron, A. Tremante, & F. Welsch (Eds.), Pro- ceedings (Vol. 1, pp. 8-11). Orlando: International Institute of Infor- matics and Systemics. Landgren, L., & Svärd, H. (2013). Lärande för de yngre barnen [Learn- ing activities for the younger children]. In M. Holmqvist Olander (Ed.), Learning study i förskolan och förskoleklassen [Learning study in early childhood e d u cation]. Lund: Studentlitteratur. Lewis, C. (2002). Lesson study: A handbook of teacher-led instruc- tional change. Philadelphia, PA: Research for Better Schools, Inc. Ljung-Djärf, A. (2013). The learning study process: A collaborative way to develop the use of contrast of critical aspects in preschool educational practice. Journal of Studies in Education, 3, 33-47. Ljung-Djärf, A., & Holmqvist Olander, M. (2013). Using learning study to understand pre-schoolers’ learning: Challenges and possi- bilities. International Journal of Early Childhood, 45, 77-100. doi:10.1007/s13158-012-0067-9 Ljung-Djärf, A., & Magnusson, A. (2010). Pre-school children’s sus- tainable thinking: The organic decomposition process as intended object of learning at pre-school. Paper Presented at the World Asso- ciation of Lesson Studies (WALS), Brunei Darussalam. Ljung-Djärf, A., Magnusson, A., & Peterson, S. (submitted). From doing to learning: Changed focus during a pre-school learning study project on organic decomposition. International Journal of Science Education. Lo, M. L. (2012). Variation theory and the improvement of teaching and learning. Göteborg: Acta Universitatas Go thenburgensis. Lo, M. L., & Marton, F. (2012). Towards a science of the art of teach- ing: Using variation theory as a guiding principle of pedagogical de- sign. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 1, 7-22. doi:10.1108/20468251211179678 Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Memorandum U2008/6144/S (2008). Uppdrag till statens skolverk om förslag till förtydliganden i läroplanen för förskolan [Assignment to the national agency of education on proposed clarifications in pre- school curriculum]. Stockholm: Ministry of educa tion and research. Ministry of Education and Research (1998). Curriculum for the pre- school, Lpfö-98. Stockholm: Fritzes. Olteanu, C., & Olteanu, L. (2010). To change teaching practice and students’ learning of mathematics. Education I nquiry, 1, 381-397. Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Asplund Carlsson, M. (2003). Det lekande lärande barnet i en utvecklingspedagogisk teori [The playing and learning child in a theory of developmental pedagogy]. Stockholm: Liber. Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Mårdsjö, A.-C. (2007). Grundläggande färdigheter och färdigheters grundläggande (2nd ed.) [Basic skills and the base of skills]. Lund: Studentlitteratur. Pramling, I. (1994). Kunnandets grunder. Prövning av en fenomeno- grafisk ansats till att utveckla barns sätt att uppfatta sin omvärld [The basis of knowledge. A phenomenographic approach to develop children’s conceptions of the world]. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. Pramling, N., & Pramling Samuelsson, I. (2011). Introduction and frame of the book. In N. Pramling, & I. Pramling Samuelsson (Eds.), Educational encounters: Nordic studies in early childhood didactics (Vol. 4, pp. 1-14 ). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1617-9_1 Pramling, N., & Pramling, Samuelsson, I. (2008). Didaktiska studier från förskola och skola [Didactic studies in pre-school and school]. Malmö: Gleerups. Runesson, U., & Mok, I. A. C. (2003). Discernment and the question “What can be learned”? In F. Marton, & A. Tsui (Eds.), Classroom discourse and the space of learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erl- baum Associates. The Swedish National Agency for Education (2004). Förskola i bry- tningstid. Nationell utvärdering av förskolan. Rapport 239 [Pre- school in transition: A national evaluation of preschool. Report 239]. Stockholm: Fr itze s. The Swedish National Agency for Education (2010). Curriculum for the pre-school, lpfö 98/20 1 0 . Stockholm : Fri t ze s. Tolchinsky, L. (2003). The cradle of culture and what children know about writing and numbers before being taught. NJ: Lawrence Erl- baum Associates. Yoshida, M., & Fernandez, C. (2004). Lesson study: A Japanese ap- proach to improving mathematics teaching and learning. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

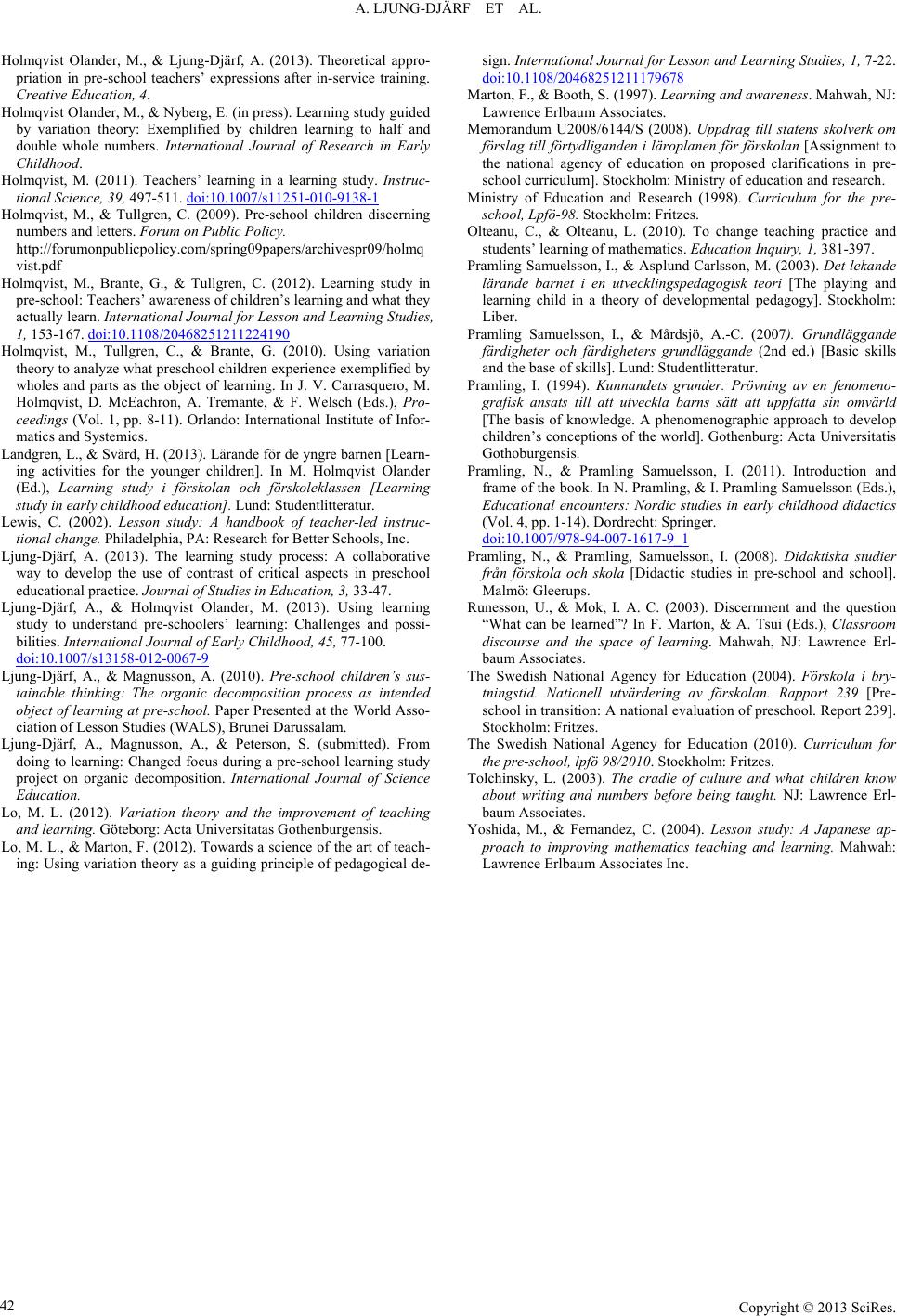

|