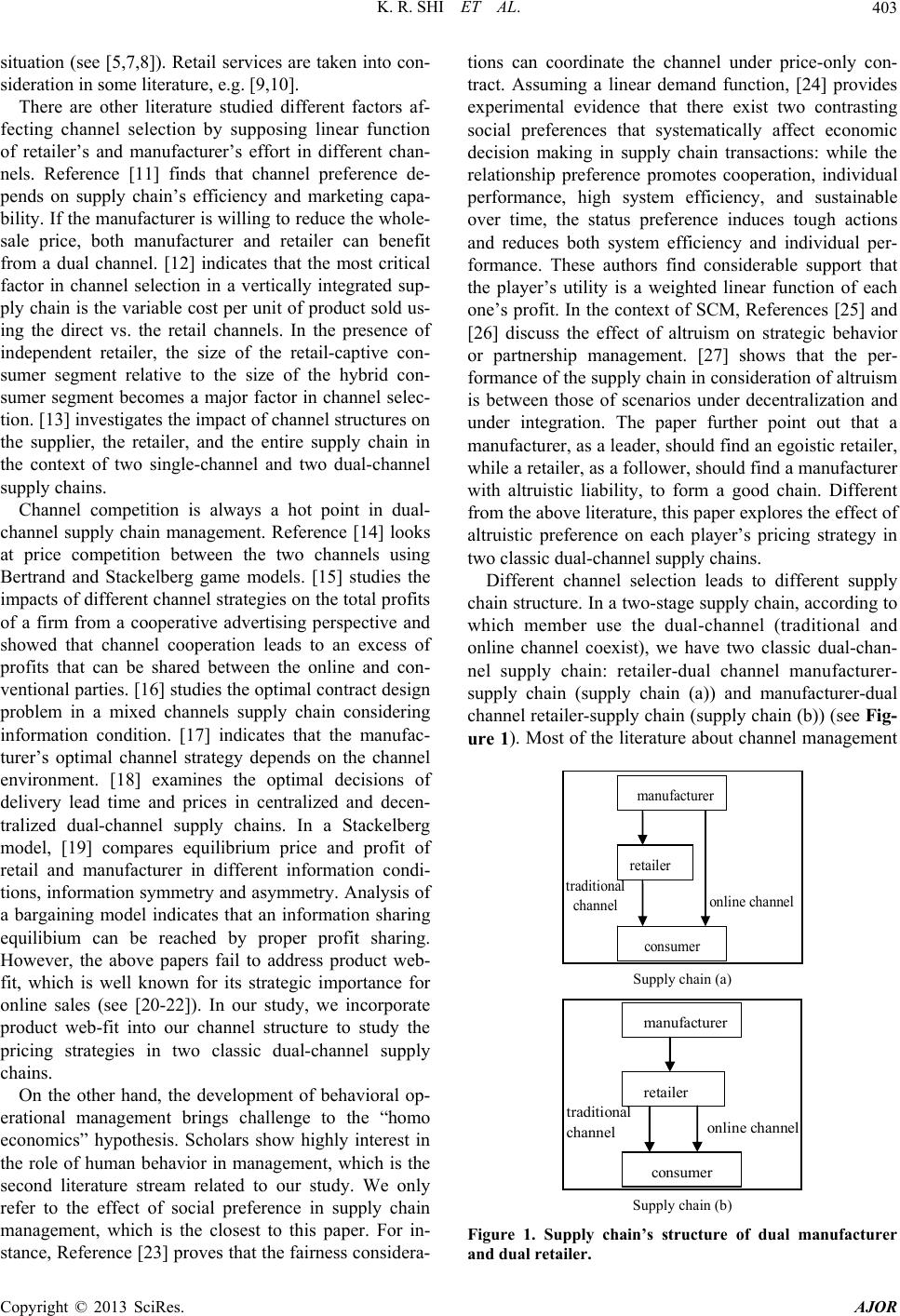

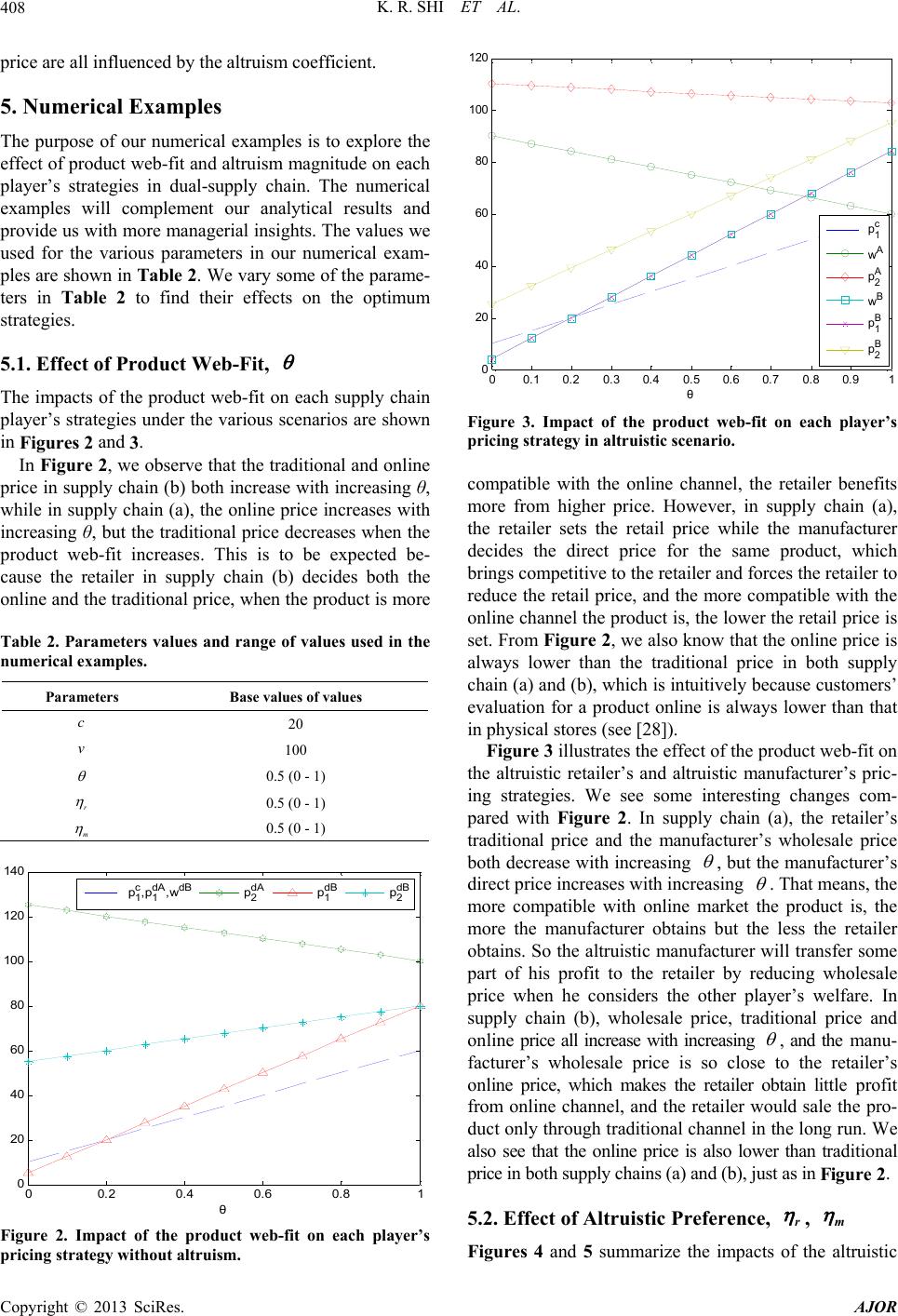

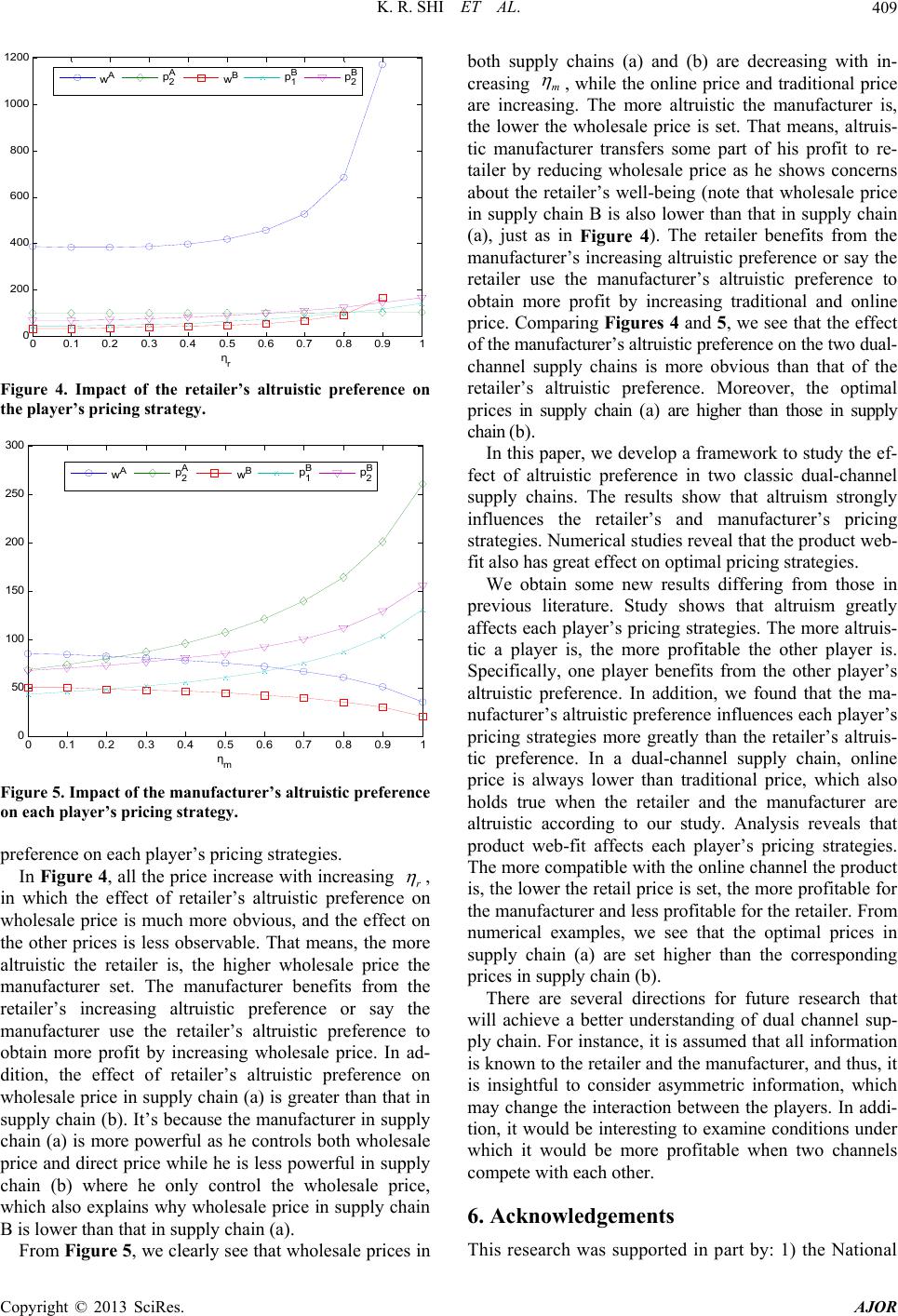

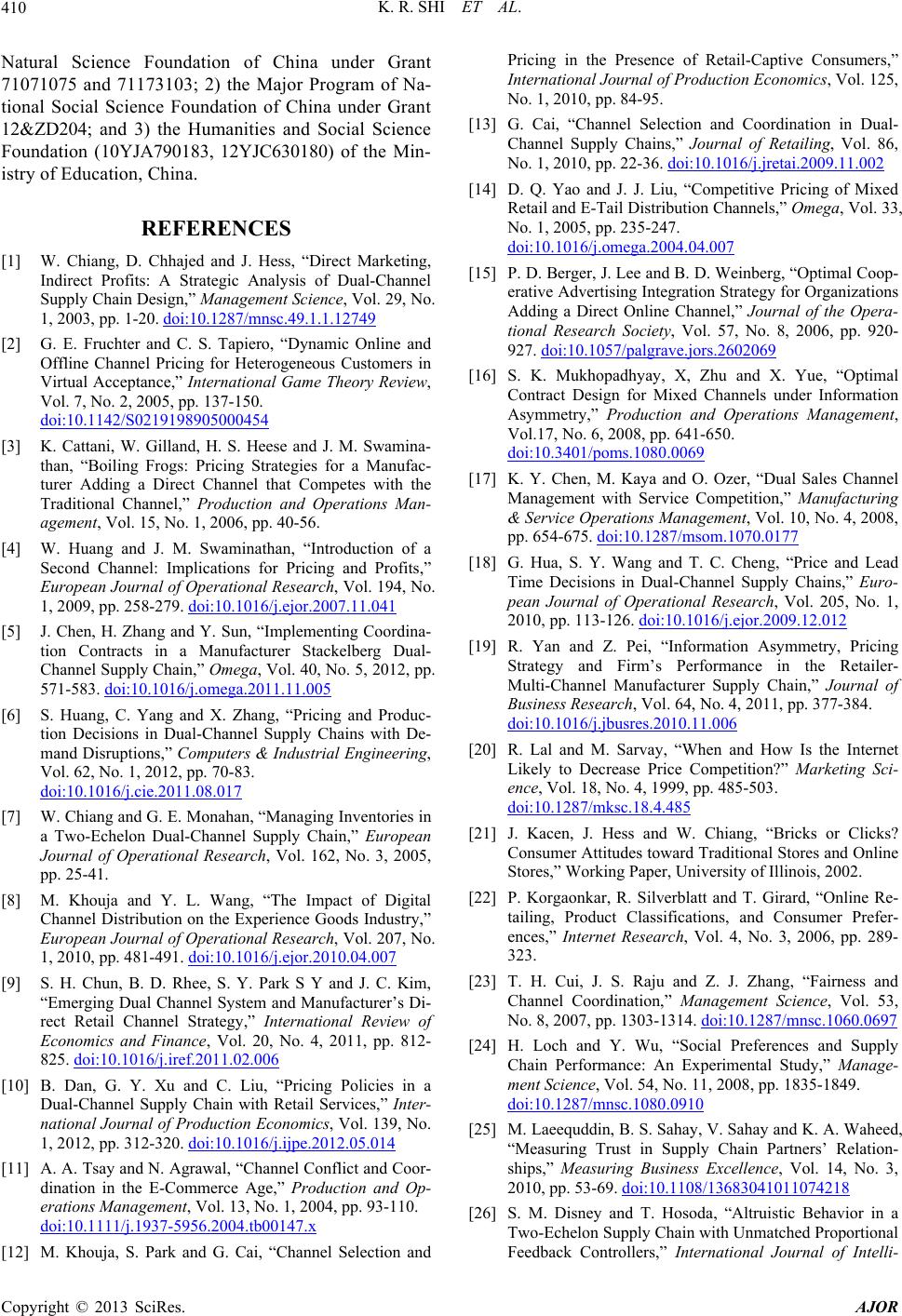

American Journal of Operations Research, 2013, 3, 402-412 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajor.2013.34038 Published Online July 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajor) Altruism and Pricing Strategy in Dual-Channel Supply Chains Kuiran Shi, Feng Jiang, Qi Ouyang College of Economics and Management, Nanjing University of Technology, Nanjing, China Email: jfandfly@163.com, ouyangqihn@163.com, shikuiran@njut.edu.cn Received May 1, 2013; revised June 1, 2013; accepted June 10, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Kuiran Shi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT With the development of behavioral operational management, human behavior such as altruism, fairness and trust has received considerable attention. This paper studies the effect of altruism on retailer’s and manufacturer’s pricing strat- egy in two classic dual-channel supply chains by presenting Stackelberg game models. The analysis shows that the player’s altruism preference strongly affects their pricing strategies. The more altruistic one player is, the more profits the other player obtains. Moreover, the effect of manufacturer’s altruistic preference is larger than that of retailer’s. In addition, online price is always lower than offline price in dual-channel supply chain, which still holds true considering altruism. The results also reveal that the product web-fit has significant effect on the player’s optimal pricing strategies. The more compatible with online market the product is, the lower the retail price is set, and the more profit the manu- facturer obtains whereas the less the retailer gets. Keywords: Altruism; Dual-Channel Supply Chain; Pricing Strategy; Product Web-Fit 1. Introduction With the emergence and development of internet, con- sumers’ demand is increasing at an amazing speed, which opens an online market with great potential. Ac- cording statistical data of iResearch, the amount of online shopping reached 498 billion in 2010, which is predicted to exceed 1000 billion in the year of 2013. Facing such temptation, every corporation is eager to share this “big cake” by adding an online channel besides the traditional one. According to one survey, about 42% of the top sup- pliers in a variety of industries such as IBM, Nike, Dell, Pioneer Electronics and Cisco System are selling directly to consumers through the direct online channel (see [1]). In addition, more and more retailers such as Wal-mart, Gome, Suning and Watsons also successfully opened their online market. In a word, e-commerce channel is increasingly adopted in supply chain. Dual-channel sup- ply chain management is thus paid with high attention in recent years. There are two main streams of research related to our paper, channel management in dual-channel supply chain and social preference. In the following, we briefly review the most related research and describe our contributions with respect to the vast, growing literature. Contrary to tremendous interest in the dual-channel distribution strategy, much recent research on dual chan- nel management tends to focus on pricing strategies rather than finding an optimal distribution strategy. Ref- erence [1] shows that a direct online channel plays a role of exerting potential competition pressure on the existing retailer by increasing the manufacturer's negotiation power and reducing the double marginalization in the retail market even though its profit is non-positive. Ref- erence [2] concludes that the manufacturer’s optimal strategy is to charge the same price across both channels. [3] shows that an equal-pricing strategy—the online channel and the retail channel are priced the same—is appropriate as long as the retail channel is significantly more convenient than the Internet channel. [4] studies the optimal pricing strategy when a retailer sells its product through both the internet channel and the traditional channel. Reference [5] indicates that a manufacturer’s contract with a wholesale price and a price for the direct channel can coordinate the dual-channel supply channel, benefiting the retailer but not the manufacturer. Refer- ence [6] shows that the optimal pricing decisions are af- fected by customers’ preference for the direct channel and the market scale, in both centralized and decentral- ized dual-channel supply chains. A lot of literature prove that dual-channel strategy is more preferable under most C opyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 403 situation (see [5,7,8]). Retail services are taken into con- sideration in some literature, e.g. [9,10]. There are other literature studied different factors af- fecting channel selection by supposing linear function of retailer’s and manufacturer’s effort in different chan- nels. Reference [11] finds that channel preference de- pends on supply chain’s efficiency and marketing capa- bility. If the manufacturer is willing to reduce the whole- sale price, both manufacturer and retailer can benefit from a dual channel. [12] indicates that the most critical factor in channel selection in a vertically integrated sup- ply chain is the variable cost per unit of product sold us- ing the direct vs. the retail channels. In the presence of independent retailer, the size of the retail-captive con- sumer segment relative to the size of the hybrid con- sumer segment becomes a major factor in channel selec- tion. [13] investigates the impact of channel structures on the supplier, the retailer, and the entire supply chain in the context of two single-channel and two dual-channel supply chains. Channel competition is always a hot point in dual- channel supply chain management. Reference [14] looks at price competition between the two channels using Bertrand and Stackelberg game models. [15] studies the impacts of different channel strategies on the total profits of a firm from a cooperative advertising perspective and showed that channel cooperation leads to an excess of profits that can be shared between the online and con- ventional parties. [16] studies the optimal contract design problem in a mixed channels supply chain considering information condition. [17] indicates that the manufac- turer’s optimal channel strategy depends on the channel environment. [18] examines the optimal decisions of delivery lead time and prices in centralized and decen- tralized dual-channel supply chains. In a Stackelberg model, [19] compares equilibrium price and profit of retail and manufacturer in different information condi- tions, information symmetry and asymmetry. Analysis of a bargaining model indicates that an information sharing equilibium can be reached by proper profit sharing. However, the above papers fail to address product web- fit, which is well known for its strategic importance for online sales (see [20-22]). In our study, we incorporate product web-fit into our channel structure to study the pricing strategies in two classic dual-channel supply chains. On the other hand, the development of behavioral op- erational management brings challenge to the “homo economics” hypothesis. Scholars show highly interest in the role of human behavior in management, which is the second literature stream related to our study. We only refer to the effect of social preference in supply chain management, which is the closest to this paper. For in- stance, Reference [23] proves that the fairness considera- tions can coordinate the channel under price-only con- tract. Assuming a linear demand function, [24] provides experimental evidence that there exist two contrasting social preferences that systematically affect economic decision making in supply chain transactions: while the relationship preference promotes cooperation, individual performance, high system efficiency, and sustainable over time, the status preference induces tough actions and reduces both system efficiency and individual per- formance. These authors find considerable support that the player’s utility is a weighted linear function of each one’s profit. In the context of SCM, References [25] and [26] discuss the effect of altruism on strategic behavior or partnership management. [27] shows that the per- formance of the supply chain in consideration of altruism is between those of scenarios under decentralization and under integration. The paper further point out that a manufacturer, as a leader, should find an egoistic retailer, while a retailer, as a follower, should find a manufacturer with altruistic liability, to form a good chain. Different from the above literature, this paper explores the effect of altruistic preference on each player’s pricing strategy in two classic dual-channel supply chains. Different channel selection leads to different supply chain structure. In a two-stage supply chain, according to which member use the dual-channel (traditional and online channel coexist), we have two classic dual-chan- nel supply chain: retailer-dual channel manufacturer- supply chain (supply chain (a)) and manufacturer-dual channel retailer-supply chain (supply chain (b)) (see Fig- ure 1). Most of the literature about channel management manufacturer retaile consumer traditional channel online channel Supply chain (a) manufacturer retailer online channel traditional channel consumer Supply chain (b) Figure 1. Supply chain’s structure of dual manufacturer and dual retailer. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 404 studied channel selection and price setting with respect to the manufacturer or the retailer. By comparing two clas- sic dual-channel supply chains in the altruism and non- altruism scenario, this paper tries to explore the effect of altruism on each player’s pricing strategies. We incorpo- rate product web-fit into demand function. Reference [28] indicates that a product bought online is less valuable to the consumer than an identical product bought through a traditional retailer. There can be several reasons for this phenomenon. First, real product can be touched by consumers in physical stores, which well conveys product attributes, while online channel cannot. Second, for the online purchase, possession and gratifi- cation is delayed, whereas they are instant when the product is purchased through the traditional channel. Besides, consumers typically will be charged a transport fee for online purchases, and returns to online stores are difficult. All these factors reduce the value of the product for online purchases. Suppose that the value of the product is when it is bought through traditional channel, and the value of the same product is v v 1 when it is purchased online. The parameter is defined as product web-fit, and is determined by product attributes and the nature of online marketing. Based on empirical analysis of data, Reference [21] shows that product web-fit turns out to be less than one for most product categories (see Table 1). Therefore, product web-fit varies with product categories and the value of product web-fit ranges from zero to one 0 < θ < 1. The value of zero signifies that the product is not compatible with online marketing at all and the value of one signifies that the product is completely compatible with online sales. Our paper considers such products whose web-fit range from zero to one. In this paper, we present an analytical framework for product web-fit in a centralized and a decentralized dual-channel supply chain system. In each system, we formulate Stackelberg game model to compare two clas- sic dual-supply chains. In the decentralized system, al- truism and non-altruism scenario are compared to exam the effect of altruism on pricing strategy. This paper con- tributes to the literature in the following three aspects: 1) we incorporate product web-fit in the demand function, which is more reasonable in fact; 2) we study the effect of altruism on each player’s pricing strategies, a new perspective in dual-channel supply chain management; 3) two classic dual-channel supply chains are compared. The reminder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the notation and formulates the de- cision models for the manufacturer and the retailer. In Table 1. Product web-fit for web-based online channel. Category Book Shoes ToothpasteDVD player FlowerFood items 0.904 0.769 0.886 0.787 0.7920.784 Sections 3 and 4, we examine the price decisions of the retailer and the manufacturer in the non-altruism and altruism scenarios respectively. Section 5 gives numeri- cal examples to illustrate the influence of altruism and product web-fit on the retailer’s, the manufacturer’s and whole supply chain’s profits. We conclude the results and suggestions for future research in Section 6. All proofs are in the appendix. 2. The Model In this paper, we consider a manufacturer who produces a single product at a unit cost c and distributes it through an independent retailer channel at a wholesale price w. The product is sold through online channel at price p1 and through traditional channel at price p2. Customers can choose either the traditional retail channel or the online channel to purchase the product. We assume that in traditional channel consumers’ evaluation of a product is v, and the retailer’s price is p2, then those consumers whose evaluation exceed p2 would purchase the product through traditional channel as they can get surplus. vr, which equals to p2, is the marginal valuation for buying from the traditional channel. We therefore have the demand functiond D = v − p2 when the retailer sales products only in physical stores. Now we discuss mixed channel. Product web-fit needs to be considered. Consumers’ evaluation of a product in online channel is supposed to be θv, and the product is sold online at the price of p1, then consumers would pre- fer to buy the product from online channel if θv > p1 v > p1/θ as they can get surplus θv − p1·vd, which equals p1/θ, is the marginal valuation for buying from the online channel. When facing two channels, consumers would prefer the channel which brings them more surpluses. So when 12 vp vp , 21 1 pp v , consumers would choose online channel. vdr, which equals 21 1 pp , is the marginal valuation for buying from traditional channel when comparing consumer surplus. When vd < vr, then vd < vr < v dr, and those consumers whose evalua- tions are in the interval [vd, vdr] would prefer to buy from the online channel, whose evaluations are in the interval [vdr, v] would prefer traditional channel. When vd > vr, then vd > v r > v dr, and no consumers is willing to buy from the online channel as traditional channel would bring more surplus in comparison, those consumers whose evaluations are in the interval [vr, v] would prefer to buy from the traditional channel, but those whose Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 405 evaluations are in the interval [0, v r] will not buy the product from either of the two channels. A similar mar- ket structure has been used by References [1] and [29]. Thus, the demand functions for the online and traditional channels, respectively, can be expressed as 21 1 1 ppp 1 d (1) 21 1 pp dv 2 22 Apwd 21 1 wcdp cd 2211 B rpwd pwd (2) In supply chain (a), the retailer’s and manufacturer’s profits are determined by r A (3) m (4) In supply chain (b), the retailer’s and manufacturer’s profits are determined by (5) 12 d d 2211cpcd pcd B mwc (6) If the dual-channel supply chain is vertically integrated, then the profit of the centralized dual-supply chain (both supply chains (a) and (b)) is (7) Note that the formulations of supply chains (a) and (b)’s profits in centralized system are identical. The fol- lowing section considers a centralized system in which all the decisions are centralized to maximize the per- formance of the entire supply chain, that is, the manu- facturer is vertically integrated with the retailer. She con- trols both decisions: the retail price and direct sale price. The centralized system solution serves as a benchmark for the decentralized setting. Then we consider a decen- tralized supply chain under the Stackelberg game led by the manufacturer. For the decentralized situation, two supply chains ((a) and (b)) are compared in non-altruism and altruism scenarios respectively. In supply chain (a), the decision process is assumed to follow the following sequence: the manufacturer, as the Stackelberg leader, determines the wholesale price and direct sale price first, then the retailer as the follower, sets his own retail price based on the manufacturer’s de- cisions. Similarly, in supply chain (b), the manufacturer sets the wholesale price first, and the retailer decides the traditional and online retail price accordingly. Here the subscript “m”, ”r”, ”c” means the parameters corresponding to the manufacturer, the retailer and the wholesale system; the superscript “c”, “d”, “A” and “B” means the parameters corresponding to the centralized and decentralized system, supply chains (a) and (b). In supply chain (a), we call the online channel as the direct channel because the manufacturer sells products through online channel directly. 3. Non-Altruism In this Section, we discuss the retailer’s and manufac- turer’s price strategies when both of them are not altruis- tic. 3.1. Centralized Dual-Channel Supply Chain Model The supply chain performs best if the channel is centrally controlled. Since the wholesale price is only used to di- vide the profit between the retailer and the manufacture, w is no longer decision variable in the centralized supply chain. The decision variable is only p1, p2. Substituting (1) and (2) into (7), we obtain: 22 1 1 2 11 11 c pp p pc pp cv p (8) Proposition 1. The online price and the traditional price are given by 12 ccv p ,22 ccv p , and the total profit πc is given as 222 4 c cv cv 1 c p1 c p v 1 c p . We easily know and will increase with in- creasing , which is reasonable because, intuitively, the higher the consumers’ evaluation for a product is, the higher its price will be set. In addition, increase with increasing while is independent of 1 c p . 3.2. Decentralized Dual-Channel Supply Chain Model In this Section, we discuss the decentralized system, in which the retailer and manufacturer maximize their own profits respectively. We model the decision process as a sequential, Stackelberg game, with the manufacturer as the leader and the retailer as the follower. We first give the retailer’s and the manufacturer’s best response func- tions, then present the method to decide the Stackelberg equilibrium strategies of the two players. 3.2.1. Retailer-Dual Channel Manufa c turer-Supply Chain Substituting (1) and (2) into (3) and (4), we obtain 21 21 A r pp pwv (9) 2121 1 1 11 A m pp ppp wc vpc (10) Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 406 Proposition 2. In retailer-dual channel manufacturer- supply chain, the optimal price of manufacturer and re- tailer are given respectively by 12 dA vc p , 2 dA vc w , 2 dA p3 24 v v . The corresponding profits of manufacturer, retailer and total supply chain are given as 222 2 24 8 c vc A m vv , 2 1 16 A r v , 22 16 A c vv 2 2 348cvc dA dA w2 dA p 1 dA p , respectively. We can easily know that , , all increase with increasing , which is intuitively reasonable. also increases with increasing 1 p v , while 2 decreases with increasing dA p , and is independent of dA w . Pro- position 2 indicates that in supply chain (a), the formula- tions of the optimal wholesale price and the optimal di- rect sale price are identical to the optimal traditional price and the online price in the centralized system. In other words, compared with the pricing strategies in the centralized supply chain, the manufacturer should con- sider the retailer as an end customer and set the whole- sale price equal to the retail price in the centralized sup- ply chain, and keep the direct sale price unchanged. Note that when is between 0 and 1, 1 is always smaller than , which would render the retailer order his products through the online channel instead of the tra- ditional channel. The extreme case is that the manu- facturer sells all his products through the online chan- nel. dA p dA w 3.2.2. Manufacturer-Dual Channel Retailer-Supply Chain Substituting (1) and (2) into (5) and (6), we obtain 21 21 1 1 1 pp v pp p 2 1 B rpw pw (11) 1 p wc v B m (12) Proposition 3. In Manufacturer-dual channel retailer- supply chain, the optimal price of manufacturer and re- tailer are given respectively by 2 dB wcv , 14 dB p3vc , 2 2 4 dB vc v p . The corresponding profits of manufacturer, retailer and total supply chain are given as 222 2 8 B m ccvv , 22 2 16 B r ccvv , 22 36 12 16 B c ccvv dB wdB pdB p v , respectively. From Proposition 3, we see that , 1, 2 are all increasing functions to and . Not that is between 0 and 1, 1 is always smaller than2, that means, the retailer sets a lower online price to appeal consumers into online market. Compared with supply chain (a), the manufacturer sets a smaller wholesale price in supply chain (b). A reasonable explanation is that when the retailer opens an online channel, the retailer benefits from dual-channel while whether the manufac- turer’s profit will be increased depends on the value of product web-fit. As a result, the manufacturer in supply chain B had better to reduce wholesale price, otherwise the retailer may contact another manufacturer to get lower wholesale price and higher profit. dB pdB p rrr m U 4. Altruism Instead of being purely self-interested, both the manu- facturer and retailer share some mutual concerns about the well-being of the others. Using altruistic utility or the “reciprocity-free” formulation in Reference [30], verified in the experiments by [24], the retailer’s utility function is: (13) where the coefficient 0,1 r 0 r measures the degree of altruistic preference of the retailer towards the manufac- turer. If , the retailer is purely competitive to- wards the manufacturer, conversely, if 1 r r , the re- tailer is fully cooperative with the manufacturer. The larger (less) is, the more cooperative (competitive) the retailer towards the manufacturer will be. Similarly, the manufacturer’s utility is mmm r U (14) where 0,1 m r is the manufacturer’s altruistic pref- erence. Note that the retailer’s profit takes full ac- count of the inventory risk while m takes no inventory risk at all, therefore Um reflects the manufacture willing- ness to share part of the supply chain inventory risk, and m characterizes the degree of this willingness. 4.1. Retailer-Dual Channel Manufacturer-Supply Chain Substituting (9) and (10) into (13) and (14), we obtain: Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. AJOR 407 21 21 2 1 11 r A r pp pp pwv wUcv 211 1 ppp pc (15) 2121 1 1 11 A m m pp ppp wc vpcpw21 2 1 pp Uv p (16) Proposition 4. For given w and 1, the optimal pric- ing strategy of altruistic retailer is given by: Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 1 A rr pwv 21 2 ppvw 2 A p w1 p . Substituting into (16), then taking the first order condition with respect to and and setting them to zero, we get the manufacturer’s best response: 12 Acv p , 2 12222 21 2 rm rmrmr A rm rm cvv w A w2 A p Then substituting and into , we get the retailer’s best response: 1 A p 2 222 12 42 rm rmrmrm A mrm vc vv p 6 2 r r From Proposition 4, we know that the altruistic re- tailer’s traditional price and the altruistic manufacturer’s wholesale price both decrease with increasing θ in supply chain (a), while the retailer’s retail price decreases with increasing θ. That means, the more compatible with online market the product is, the more profitable for the manufacturer and less profitable for the retailer. In addi- tion, both the manufacturer’s optimal wholesale price and the retailer’s retail price are affected by the altruism coefficient, but the manufacturer’s direct price is inde- pendent of the altruism magnitude. 4.2. Manufacturer-Dual Channel Retailer-Supply Chain Substituting (11) and (12) into (13) and (14), we obtain: 2121 11 21 11 r r Bpp pppp pww wcUv pv (17) 121211 21 11 B mm pppppp wc vpwvpwU (18) Proposition 5. For given w, the optimal pricing stra- tegy of altruistic retailer is given by 1 1 2 B rr pwcwv , 2 1 2 B rr pwcwv . Substituting 1 p and 2 p into (18) and taking the first order condition with respect to w, letting it to zero, we have: 2 2 12 Brrm m rmrm cc cvv w , which is the altruistic manufacturer’s best response. Then substituting w1 into p2 and p, we get the altruistic retailer’s best response: 1 3 22 mmrmr mrmB mrm vcvc c prm 2 2 22 mmrmr mrmB mrm vcvvc c prm From Proposition 5, we know that the optimal whole- sale price, traditional price and online price all increase with increasing in altruism scenario. Compared with supply chain (a), in supply chain (b), the retailer, who adopted dual channel, owns more power to control the traditional and online prices, which leads to the positive correlation between her profit and the product web-fit. In addition, the wholesale price, online price and traditional  K. R. SHI ET AL. 408 price are all influenced by the altruism coefficient. 120 5. Numerical Examples The purpose of our numerical examples is to explore the effect of product web-fit and altruism magnitude on each player’s strategies in dual-supply chain. The numerical examples will complement our analytical results and provide us with more managerial insights. The values we used for the various parameters in our numerical exam- ples are shown in Tabl e 2. We vary some of the parame- ters in Table 2 to find their effects on the optimum strategies. 5.1. Effect of Product Web-Fit, The impacts of the product web-fit on each supply chain player’s strategies under the various scenarios are shown in Figures 2 and 3. In Figure 2, we observe that the traditional and online price in supply chain (b) both increase with increasing θ, while in supply chain (a), the online price increases with increasing θ, but the traditional price decreases when the product web-fit increases. This is to be expected be- cause the retailer in supply chain (b) decides both the online and the traditional price, when the product is more Table 2. Parameters values and range of values used in the numerical examples. Parameters Base values of values c 20 v 100 0.5 (0 - 1) r 0.5 (0 - 1) m 0.5 (0 - 1) 00.2 0.4 0.6 0.81 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 θ p 1 c ,p 1 dA ,w dB p 2 dA p 1 dB p 2 dB Figure 2. Impact of the product web-fit on each player’s pricing strategy without altruism. 00.1 0.20.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.70.8 0.9 1 0 20 40 60 80 100 θ pc 1 wA pA 2 wB pB 1 pB 2 Figure 3. Impact of the product web-fit on each player’s pricing strategy in altruistic scenario. compatible with the online channel, the retailer benefits more from higher price. However, in supply chain (a), the retailer sets the retail price while the manufacturer decides the direct price for the same product, which brings competitive to the retailer and forces the retailer to reduce the retail price, and the more compatible with the online channel the product is, the lower the retail price is set. From Figure 2, we also know that the online price is always lower than the traditional price in both supply chain (a) and (b), which is intuitively because customers’ evaluation for a product online is always lower than that in physical stores (see [28]). Figure 3 illustrates the effect of the product web-fit on the altruistic retailer’s and altruistic manufacturer’s pric- ing strategies. We see some interesting changes com- pared with Figure 2. In supply chain (a), the retailer’s traditional price and the manufacturer’s wholesale price both decrease with increasing , but the manufacturer’s direct price increases with increasing .hat means, the more compatible with online market the product is, the more the manufacturer obtains but the less the retailer obtains. So the altruistic manufacturer will transfer some part of his profit to the retailer by reducing wholesale price when he considers the other player’s welfare. In supply chain (b), wholesale price, traditional price and online price all increase with increasing T , and the manu- facturer’s wholesale price is so close to the retailer’s online price, which makes the retailer obtain little profit from online channel, and the retailer would sale the pro- duct only through traditional channel in the long run. We also see that the online price is also lower than traditional price in both supply chains (a) and (b), just as in F ig ure 2. 5.2. Effect of Altruistic Preference, r , m Figures 4 and 5 summarize the impacts of the altruistic Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 409 00.1 0.20.3 0.40.5 0.6 0.70.8 0.91 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 η r w A p A 2 w B p B 1 p B 2 Figure 4. Impact of the retailer’s altruistic preference on the player’s pricing strategy. 00.1 0.20.3 0.40.5 0.6 0.70.8 0.91 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 η m w A p A 2 w B p B 1 p B 2 Figure 5. Impact of the manufacturer’s altruistic preference on each player’s pricing strategy. preference on each player’s pricing strategies. In Figure 4, all the price increase with increasing r , in which the effect of retailer’s altruistic preference on wholesale price is much more obvious, and the effect on the other prices is less observable. That means, the more altruistic the retailer is, the higher wholesale price the manufacturer set. The manufacturer benefits from the retailer’s increasing altruistic preference or say the manufacturer use the retailer’s altruistic preference to obtain more profit by increasing wholesale price. In ad- dition, the effect of retailer’s altruistic preference on wholesale price in supply chain (a) is greater than that in supply chain (b). It’s because the manufacturer in supply chain (a) is more powerful as he controls both wholesale price and direct price while he is less powerful in supply chain (b) where he only control the wholesale price, which also explains why wholesale price in supply chain B is lower than that in supply chain (a). From Figure 5, we clearly see that wholesale prices in both supply chains (a) and (b) are decreasing with in- creasing m , while the online price and traditional price are increasing. The more altruistic the manufacturer is, the lower the wholesale price is set. That means, altruis- tic manufacturer transfers some part of his profit to re- tailer by reducing wholesale price as he shows concerns about the retailer’s well-being (note that wholesale price in supply chain B is also lower than that in supply chain (a), just as in Figure 4). The retailer benefits from the manufacturer’s increasing altruistic preference or say the retailer use the manufacturer’s altruistic preference to obtain more profit by increasing traditional and online price. Comparing Figures 4 and 5, we see that the effect of the manufacturer’s altruistic preference on the two dual- channel supply chains is more obvious than that of the retailer’s altruistic preference. Moreover, the optimal prices in supply chain (a) are higher than those in supply chain (b). In this paper, we develop a framework to study the ef- fect of altruistic preference in two classic dual-channel supply chains. The results show that altruism strongly influences the retailer’s and manufacturer’s pricing strategies. Numerical studies reveal that the product web- fit also has great effect on optimal pricing strategies. We obtain some new results differing from those in previous literature. Study shows that altruism greatly affects each player’s pricing strategies. The more altruis- tic a player is, the more profitable the other player is. Specifically, one player benefits from the other player’s altruistic preference. In addition, we found that the ma- nufacturer’s altruistic preference influences each player’s pricing strategies more greatly than the retailer’s altruis- tic preference. In a dual-channel supply chain, online price is always lower than traditional price, which also holds true when the retailer and the manufacturer are altruistic according to our study. Analysis reveals that product web-fit affects each player’s pricing strategies. The more compatible with the online channel the product is, the lower the retail price is set, the more profitable for the manufacturer and less profitable for the retailer. From numerical examples, we see that the optimal prices in supply chain (a) are set higher than the corresponding prices in supply chain (b). There are several directions for future research that will achieve a better understanding of dual channel sup- ply chain. For instance, it is assumed that all information is known to the retailer and the manufacturer, and thus, it is insightful to consider asymmetric information, which may change the interaction between the players. In addi- tion, it would be interesting to examine conditions under which it would be more profitable when two channels compete with each other. 6. Acknowledgements This research was supported in part by: 1) the National Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. 410 Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 71071075 and 71173103; 2) the Major Program of Na- tional Social Science Foundation of China under Grant 12&ZD204; and 3) the Humanities and Social Science Foundation (10YJA790183, 12YJC630180) of the Min- istry of Education, China. REFERENCES [1] W. Chiang, D. Chhajed and J. Hess, “Direct Marketing, Indirect Profits: A Strategic Analysis of Dual-Channel Supply Chain Design,” Management Science, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2003, pp. 1-20. doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.1.1.12749 [2] G. E. Fruchter and C. S. Tapiero, “Dynamic Online and Offline Channel Pricing for Heterogeneous Customers in Virtual Acceptance,” International Game Theory Review, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2005, pp. 137-150. doi:10.1142/S0219198905000454 [3] K. Cattani, W. Gilland, H. S. Heese and J. M. Swamina- than, “Boiling Frogs: Pricing Strategies for a Manufac- turer Adding a Direct Channel that Competes with the Traditional Channel,” Production and Operations Man- agement, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2006, pp. 40-56. [4] W. Huang and J. M. Swaminathan, “Introduction of a Second Channel: Implications for Pricing and Profits,” European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 194, No. 1, 2009, pp. 258-279. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2007.11.041 [5] J. Chen, H. Zhang and Y. Sun, “Implementing Coordina- tion Contracts in a Manufacturer Stackelberg Dual- Channel Supply Chain,” Omega, Vol. 40, No. 5, 2012, pp. 571-583. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2011.11.005 [6] S. Huang, C. Yang and X. Zhang, “Pricing and Produc- tion Decisions in Dual-Channel Supply Chains with De- mand Disruptions,” Computers & Industrial Engineering, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2012, pp. 70-83. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2011.08.017 [7] W. Chiang and G. E. Monahan, “Managing Inventories in a Two-Echelon Dual-Channel Supply Chain,” European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 162, No. 3, 2005, pp. 25-41. [8] M. Khouja and Y. L. Wang, “The Impact of Digital Channel Distribution on the Experience Goods Industry,” European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 207, No. 1, 2010, pp. 481-491. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2010.04.007 [9] S. H. Chun, B. D. Rhee, S. Y. Park S Y and J. C. Kim, “Emerging Dual Channel System and Manufacturer’s Di- rect Retail Channel Strategy,” International Review of Economics and Finance, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2011, pp. 812- 825. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2011.02.006 [10] B. Dan, G. Y. Xu and C. Liu, “Pricing Policies in a Dual-Channel Supply Chain with Retail Services,” Inter- national Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 139, No. 1, 2012, pp. 312-320. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.05.014 [11] A. A. Tsay and N. Agrawal, “Channel Conflict and Coor- dination in the E-Commerce Age,” Production and Op- erations Management, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2004, pp. 93-110. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2004.tb00147.x [12] M. Khouja, S. Park and G. Cai, “Channel Selection and Pricing in the Presence of Retail-Captive Consumers,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 125, No. 1, 2010, pp. 84-95. [13] G. Cai, “Channel Selection and Coordination in Dual- Channel Supply Chains,” Journal of Retailing, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2010, pp. 22-36. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2009.11.002 [14] D. Q. Yao and J. J. Liu, “Competitive Pricing of Mixed Retail and E-Tail Distribution Channels,” Omega, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2005, pp. 235-247. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2004.04.007 [15] P. D. Berger, J. Lee and B. D. Weinberg, “Optimal Coop- erative Advertising Integration Strategy for Organizations Adding a Direct Online Channel,” Journal of the Opera- tional Research Society, Vol. 57, No. 8, 2006, pp. 920- 927. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602069 [16] S. K. Mukhopadhyay, X, Zhu and X. Yue, “Optimal Contract Design for Mixed Channels under Information Asymmetry,” Production and Operations Management, Vol.17, No. 6, 2008, pp. 641-650. doi:10.3401/poms.1080.0069 [17] K. Y. Chen, M. Kaya and O. Ozer, “Dual Sales Channel Management with Service Competition,” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2008, pp. 654-675. doi:10.1287/msom.1070.0177 [18] G. Hua, S. Y. Wang and T. C. Cheng, “Price and Lead Time Decisions in Dual-Channel Supply Chains,” Euro- pean Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 205, No. 1, 2010, pp. 113-126. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2009.12.012 [19] R. Yan and Z. Pei, “Information Asymmetry, Pricing Strategy and Firm’s Performance in the Retailer- Multi-Channel Manufacturer Supply Chain,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 64, No. 4, 2011, pp. 377-384. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.006 [20] R. Lal and M. Sarvay, “When and How Is the Internet Likely to Decrease Price Competition?” Marketing Sci- ence, Vol. 18, No. 4, 1999, pp. 485-503. doi:10.1287/mksc.18.4.485 [21] J. Kacen, J. Hess and W. Chiang, “Bricks or Clicks? Consumer Attitudes toward Traditional Stores and Online Stores,” Working Paper, University of Illinois, 2002. [22] P. Korgaonkar, R. Silverblatt and T. Girard, “Online Re- tailing, Product Classifications, and Consumer Prefer- ences,” Internet Research, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2006, pp. 289- 323. [23] T. H. Cui, J. S. Raju and Z. J. Zhang, “Fairness and Channel Coordination,” Management Science, Vol. 53, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1303-1314. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0697 [24] H. Loch and Y. Wu, “Social Preferences and Supply Chain Performance: An Experimental Study,” Manage- ment Science, Vol. 54, No. 11, 2008, pp. 1835-1849. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1080.0910 [25] M. Laeequddin, B. S. Sahay, V. Sahay and K. A. Waheed, “Measuring Trust in Supply Chain Partners’ Relation- ships,” Measuring Business Excellence, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2010, pp. 53-69. doi:10.1108/13683041011074218 [26] S. M. Disney and T. Hosoda, “Altruistic Behavior in a Two-Echelon Supply Chain with Unmatched Proportional Feedback Controllers,” International Journal of Intelli- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR  K. R. SHI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR 411 gent Systems Technologies and Applications, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2009, pp. 269-286. doi:10.1504/IJISTA.2009.024257 [27] Z. H. Ge, Q. Y. Hu, “Who Benefits from Altruism in Supply Chain Management?” American Journal of Op- erational Research, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2012, pp. 59-72. doi:10.4236/ajor.2012.21007 [28] R. C. King, R. Sen and M. Xia, “Impact of Web-Based E-Commerce on Channel Strategy in Retailing,” Interna- tional Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2004, pp. 103-130. [29] R.Yan, J. Wang and B. Zhou, “Channel Integration and Profit Sharing in the Dynamics of Multi-channel Firms,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2010, pp. 430-440. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2010.04.004 [30] G. Charness and M. Rabin, “Understanding Social Pref- erences with Simple Tests,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, No. 3, 2002, pp. 817-869. doi:10.1162/003355302760193904  K. R. SHI ET AL. 412 Appendix Proof of Proposition 1 Taking the second-order partial derivatives of c with respect to and , we have the Hessian matrix 1 p2 p 1 2 22 2 12 22 2 21 2 cc cc ppp H pp p 11 2 11 22 11 . Since 1 2 20 c p , and 11 2 2 11 0 22 11 c , is strictly jointly concave in and . So the optimal solution exists. Then let the first-order condition equal to zero, we derive Proposition 1. 1 p2 p A r Proof of Proposition 2 Taking the second-order partial derivatives of with respect to , we have 2 p 2 2 2 r p 20 1 A r . Then let the first-order partial derivative of with respect to be zero, we have 2 p 1 2 vp w A 2 1 p, then substitute it into (10), and m becomes a joint function of and . We can easily obtain the opti- mal solution by analyzing Hessian matrix and the first- order condition. 1 pw Proof of Proposition 3 Taking the second-order partial derivatives of r with respect to and , we have the Hessian matrix 1 p2 p 1 2 22 2 12 22 2 21 11 2 211 22 11 BB rr BB rr ppp H pp p . Since 1 2 20 c p , and 11 2 211 0 22 11 c , is strictly jointly concave in and . So the optimal solution exists. Then let the first-order condi- tions equal to zero, we derive 1 p2 p 12 wv p , 22 wv p w . Substituting them into (12), and letting the first-order condition of be zero, we have 2 cv w , and then Proposition 3 is proved. Proof of Proposition 4 The proof of Proposition 4 is similar to Proposition 2, so we omit it. Proof of proposition 5 The proof of Proposition 5 is similar toProposition 3, so we omit it. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. AJOR

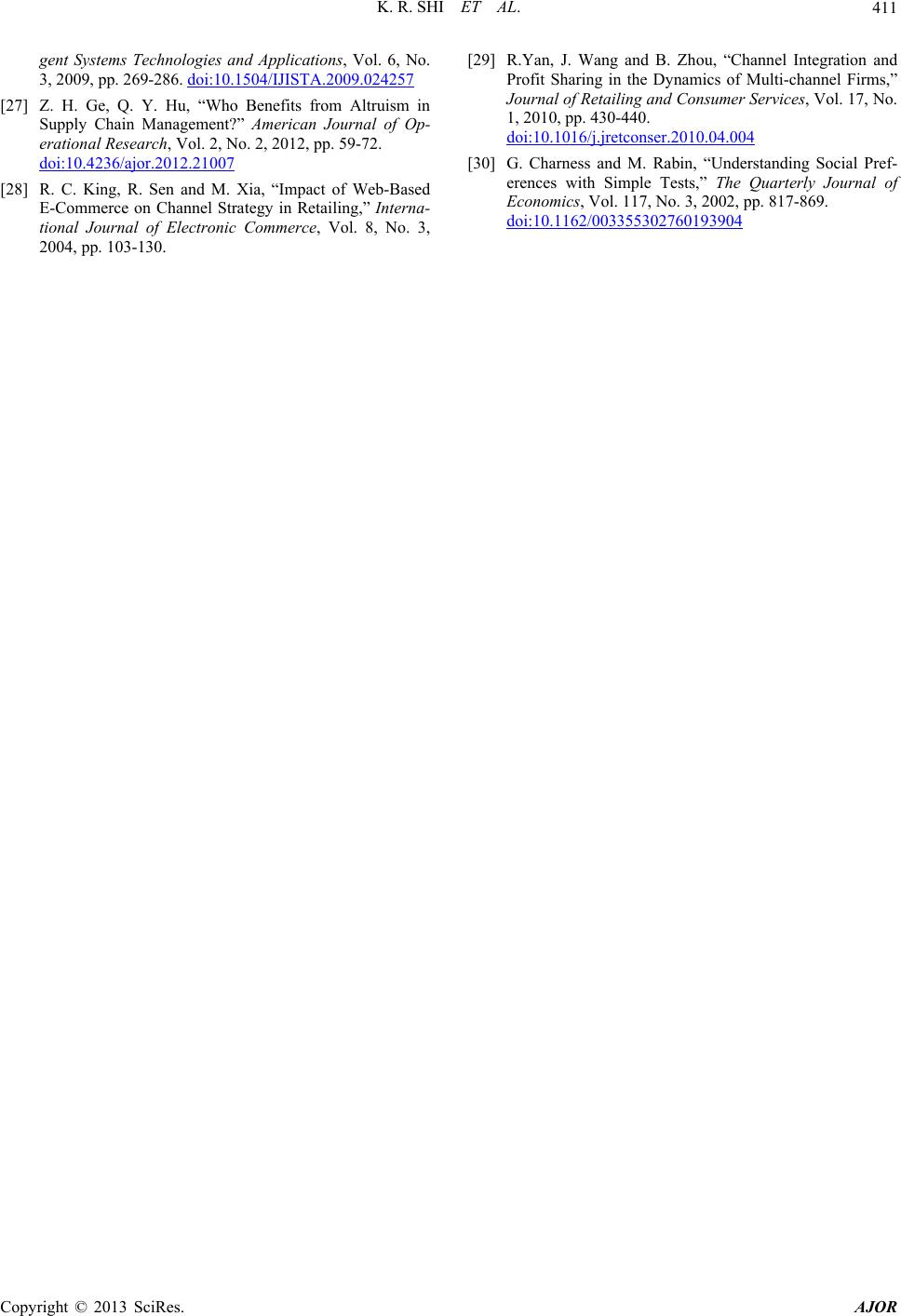

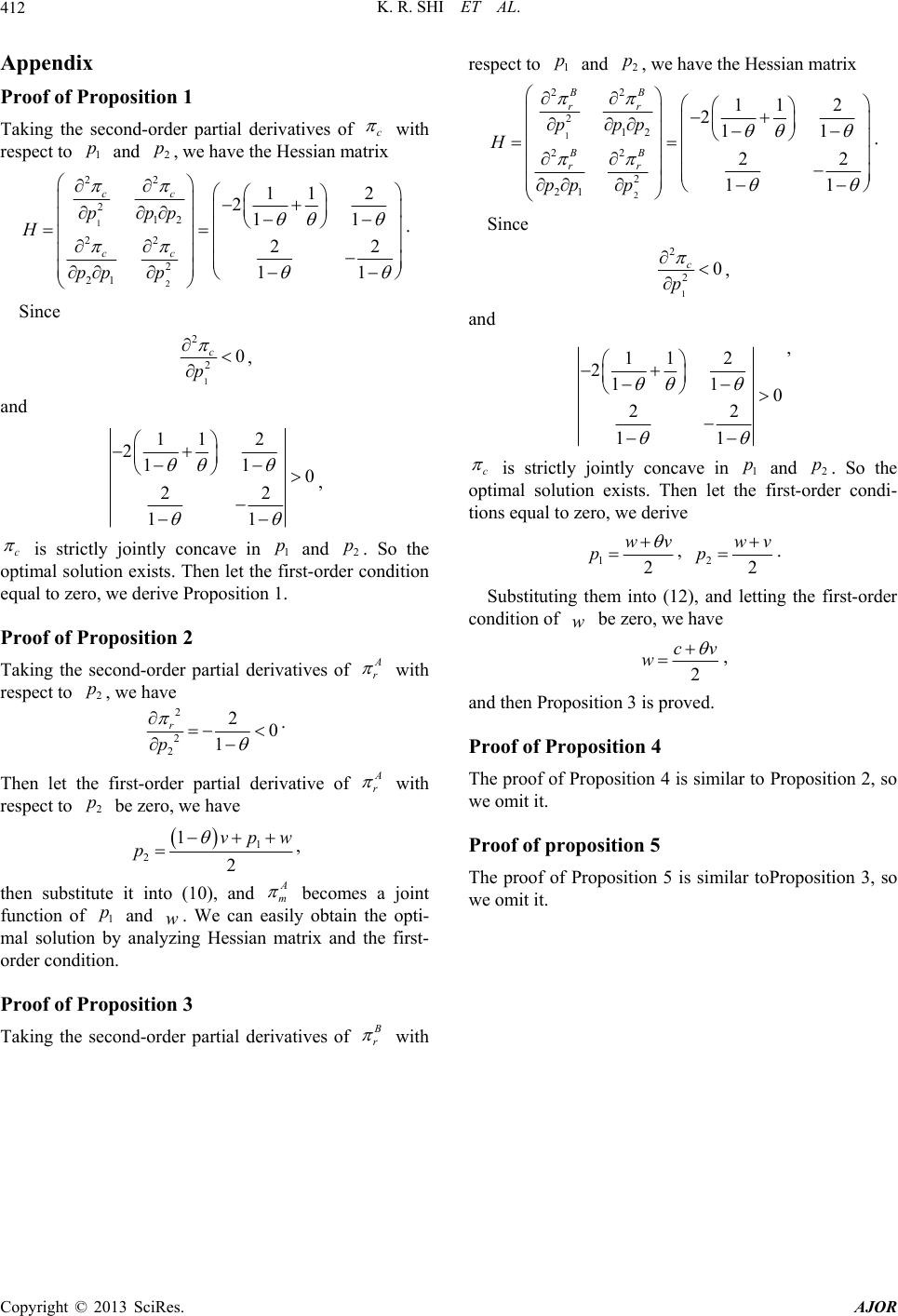

|