Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.7A, 1-10 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.47A001 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 Bilingualism and Measures of Spontaneous and Reactive Cognitive Flexibility Raphiq Ibrahim1,2*, Reut Shoshani1, Anat Prior1,2, David Share1,2 1Learning Disabilities Department, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel 2The Edmond J. Safra Brain Research Center for the Study of Learning Disabilities, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel Email: *raphiq@psy.haifa.ac.il Received April 20th, 2013; revised May 22nd, 2013; accepted June 21st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Raphiq Ibrahim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In this study, we assessed possible consequences of bilingualism on executive function among adults. Three groups of adults were tested with a series of tests designed to tap two types of cognitive flexibility: reactive flexibility and spontaneous flexibility (The experimental groups comprised bilinguals equally proficient in Hebrew and English (balanced), Hebrew-dominant bilinguals and English-dominant bilin- gual participants). The results revealed several significant differences where the balanced bilinguals per- formed better relative to individuals from the same cultural background. In both types of flexibility tasks, the balanced-bilinguals were found to be superior to the Hebrew-dominant group but not compared to those who mastered English as their primary language. A significant difference between the balanced-bi- lingual group and the Hebrew-dominant group was found in the task which required spontaneous cogni- tive flexibility and the one which required reactive cognitive flexibility. The comparison of these unique findings with other findings in the literature and their psycholinguistic implications are discussed. Keywords: Bilingualism; Attention; Executive Functions; Spontaneous Flexibility; Reactive Flexibility Introduction In everyday life, the bilingual person has to be sensitive to external linguistic signals from his or her surroundings (“bot- tom-up” control) and at the same time must perform an internal directing (“top-down” control) in order to translate the external input and choose the language in which s/he wants to produce the output (Green, 1998). These choices are considered to en- hance executive aspects of perception and thinking for children (Bialystok, 1999; Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008) and adults (Col- zato, Bajo, van den Wildenberg, Paolieri, Nieuwenhuis, La Heij, & Hommel, 2008). Several studies have shown that among bilinguals both languages are active even if only one of them is being used (Brysbaert, 1998). It was found, for example, that bilingual subjects can listen to one language while simultane- ously speaking in their second language (Grosjean, 1988). The joint brain activity of the two languages requires a mechanism for keeping the languages separate in order to allow fluent speech in one language without any intrusions from the other one. Green (1998) developed an inhibitory control model in which the non-relevant language is suppressed by the same executive functions used generally to control attention and in- hibition. Another study used a modified antisaccade task in order to explore the cognitive effects of bilingualism among adults (Bialystok, Craik, & Ryan, 2006). In a typical antisac- cade task, the viewer fixates a central location while a stimulus is flashed to one side of the fixation. The viewer is asked to make an antisaccadic eye movement in the opposite direction to the flashed cue. Success on this task requires the ability to override the reflexive response of initiating a saccade toward a target and is therefore is tied to intact executive functions. An advantage was found among bilingual adult subjects in a ver- sion of the task which used a behavioral response method. The advantage was seen under different task conditions rep- resenting distinctive executive functions-response suppression, inhibitory control and task switching. These executive proc- esses are highly developed among bilinguals who must manage and control two lexical systems. Colzato and her colleagues (2008) explored the mechanism underlying the bilingual advantage in inhibiting irrelevant in- formation and representations. Their results suggest that the cognitive processing advantages that bilinguals enjoy are not due to direct active inhibition processing but rather to con- structing and maintaining more efficient goal representations in working memory. They propose that learning to keep two or more languages separate leads to a general improvement in “reactive inhibition” mechanisms in which goal-relevant infor- mation is selected from competing goal-irrelevant information. These results converge with other findings which suggest a bi- lingual advantage in situations involving high processing de- mands from working memory besides the executive need for inhibition (Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004). In most studies into the effects of bilingualism on executive functions, as well as on other functions, children have been the subjects. Children who grow up in a bilingual environment are continually obliged to attend to the abstract dimensions of lan- guage. Since they are able to name the same object with differ- *Corresponding author.  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. ent names, they come to appreciate the distinction between words and their meaning, as well as understand the arbitrary nature of object names (Ianco-Worrall, 1972). Apparently, bilingual children are said to acquire an advan- tage in a process defined by Bialystok (1993) as the “analysis of representations”—the process by which mental representa- tions are constructed in memory, and the way in which they are organized, analyzed and retrieved. The need to associate words from two languages with a common concept requires more ad- vanced representation because the connections between the words exist at a more abstract level than the connection between a particular word and its meaning. This semantic structure might be expected to be more hierarchical than that of the monolin- gual, and the process of constructing this structure could en- hance children’s representational processes (Bialystok, 1999). Previous research conducted by Bialystok (1999) has dem- onstrated that bilingual children showed an advantage over monolingual children on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) which involved switching from one set of rules to another. Later, Zied and his colleagues supported this conclu- sion by using a Stroop Task where the subjects were required to respond to the ink color in which color names are printed while ignoring the color word itself (Zied, Phillipe, Karine, Valerie, Ghislaine, & Arnaud, 2004). They explained that the need to manage two lexical systems created a considerable cognitive challenge for the bilingual person. In addition to the need to maintain separate access to each language, there are situations in which concurrent use of the two languages takes place ne- cessitating a selection between two competitive responses. Re- cent research on bilingual aduls suggested that a bilingual’s experience with language switching speeded the maturation of attention and executive processes (Kiesel et al., 2010; Meiran, 2010). The question of whether the specific language combina- tions that bilinguals speak might influence the existence or degree of cognitive benefits they enjoy has only recently started to receive attention in the literature ((Bialystok, 2010; Costa, Hernandez, & Sebastian-Gall’s, 2009; Hilchey & Klein, 2011; Prior & MacWhinney, 2010; Prior & Gollan, 2011). Hilchey and Klein (2011) similarly locate the bilingual advantage in a central executive system that regulates processing across a wide range of tasks and domains. They explained that the bilingual advantage is mainly attributed to the need to manage language selection. The continual use of and exposure to two languages throughout life promotes executive functioning, as mentioned before, and therefore may increase the effectiveness of the cor- tical region responsible for these functions. Evidence that switching languages is supported by the same neural paths which are responsible for other cognitive control mechanisms comes from an ERP study which compared brain activity dur- ing language switching in a digit naming task to activity during suppression of responses in a Go/No-Go task among bilingual subjects (Jackson, Swainson, Cunnington, & Jackson, 2001). Another imaging study which supports the assumption that the management of two language systems leads to systematic changes in frontal executive functions was carried out by Bia- lystok, Craik et al., (2005). In this study, young bilingual sub- jects activated more frontal regions compared to monolingual subjects during a task which required inhibition control. Bilingualism has also been shown to have a positive effect on the functioning of an individual’s attentional system across the life-span (e.g., Bialystok, 1999; Costa et al., 2008). Using the Flanker Task (subjects are asked to indicate whether a cen- tral arrow that was presented along with four flanker arrows pointing to the same [congruent] or different [incongruent] direction points to the right or to the left), Costa and his col- leagues (2008) showed that responses tended to be slower for incongruent than for congruent trials (the conflict effect). The bilingual advantage in this task was indexed by a reduced con- flict effect for bilinguals in comparison to monolinguals. The researchers claimed that, this effect may reflect an impact of bilingualism on the efficiency of other cognitive processes than conflict resolution per se, as has already been suggested by several authors (e.g., response suppression and switching; Bia- lystok, Craik, & Ryan, 2006). In a recent study, Prior and colleagues (Prior & Gollan, 2011; Prior & MacWhinney, 2010), tried to elaborate on the nature of executive control advantages accrued by bilinguals, with spe- cific emphasis on cognitive flexibility; and how individual dif- ferences in executive control and cognitive flexibility might further our understanding of the variability in second language learning outcomes. They compared the performance of bilinguals and monolin- guals in a task switching paradigm that included only two tasks, and most importantly, task repetition trials. The inclusion of task repetition trials allows for calculating switching costs, namely, the increased difficulty in responding in trials where the task set changes when compared to trials where the task set remains unchanged. In this paradigm, bilinguals demonstrated a smaller switch cost than monolinguals, although in Prior and Gollan (2011) this finding was limited to only one of the two bilingual groups examined. According to Bialystok (1993), because bilinguals hold lin- guistic representations of two languages, they consistently ex- perience the need to attend to representations from one lan- guage while inhibiting these from the irrelevant language. This dissociation between “analysis of representations” and “control of attention” has been found in tasks from several domains. In meta-linguistic tasks, bilingual children have been found to be superior to monolinguals at judging the grammaticality of sen- tences containing distracting semantic information (for example, deciding whether the sentence Apples grow on noses is gram- matically correct), but both groups were equivalent in detecting grammatical violations in sentences that had no distracting information (Apples on trees grow) (Cromdal, 1999). The Present Study The above literature highlights the contribution of bilingual- ism to the development of executive functions, starting from early childhood. As noted earlier, previous studies among adult bilinguals have focused on executive functions which involve selective attention and control of inhibition as well as on work- ing memory. The present study will expand the frame of refer- ence to the executive function of cognitive flexibility which has not been examined to date. However, it should be mentioned that a previous study (Bialystok, Martin & Viswanathan, 2005) examining the executive functions of control of attention and inhibition with the “Simon Task1”, unexpectedly found a bilin- 1The Simon task assesses the extent to which subjects respond when stimu- lus and response side corresponded compared to when they did not, even when stimulus positions were irrelevant for the task. For example, if sub- ects are asked to press a left key in response to a green stimulus and a right key in response to a red stimulus, response will be faster when the green stimulus ap ears on the left than when it appears on the right. The influence of the irrelevant spatial stimulus feature on performance is known as the Simon effect (see review in Lu & Proctor, 1995). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 2  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. gual advantage in both task conditions (congruent and incon- gruent) across a wide range of ages. It might be that these re- sults indicate bilingual superiority in managing a mixed set of items - a process which requires cognitive flexibility. According to Spiro and Jehng (1990), cognitive flexibility is defined as “the ability to adaptively re-assemble diverse ele- ments of knowledge to fit the particular needs of a given under- standing or problem-solving situation” (p. 169). According to Eslinger and Grattan (1993), cognitive flexibility is not a uni- tary process, and is based on multiple components such as pro- duction of a diversity of ideas, considering response alterna- tives and modifying plans and behavior in response to changing circumstances in order to attain long term goals. From a neurocognitive point of view, cognitive flexibility has been localized to the frontal lobes (Cicerone, Lazar, & Shapiro, 1983; Milner & Petrides, 1984). Eslinger & Grattan (1993) distinguished between two types of cognitive flexibility: Spontaneous flexibility and reactive flexibility. Spontaneous flexibility refers to the ability to generate a diversity of ideas. Spontaneous flexibility tasks typically require subjects to ac- cess various classes and categories of knowledge while by- passing automatic and habitual responses and strategies in order to attend to novel features of knowledge. In contrast, reactive flexibility refers to the readiness to shift cognition and behavior according to the particular demands and context of a situation. It is important to emphasize that bilingualism is not an “all-or-none” phenomenon but is rather an individual charac- teristic which can exist in different degrees (Hornby, 1977). Indeed, it is possible to define groups of bilinguals according to their relative proficiency in each of two languages. Lambert, Havelka and Gardener (1959) introduced the term “balanced bilingualism” to refer to individuals with full linguistic compe- tence in both languages. On the other hand, a “dominant” bi- lingual person has higher proficiency in one language, and uses it more often than the other language (Wei, 2000). Due to expanding globalization processes in recent decades, it has become increasingly difficult to identify individuals who have been exposed to only a single language throughout their lives (monolinguals). Therefore, the present study explored the effect of bilingualism on the executive function of cognitive flexibility by comparing a group of balanced bilinguals who have “mother tongue” proficiency in two languages, to two other dominant bilingual groups. Since studies with bilingual adults (Kroll & Stewart, 1994) and children (Bialystok, 1999) have revealed that the cognitive and linguistic consequences of bilingualism are more salient for those bilinguals who are relatively balanced in their proficiency, the main hypothesis of the present study is that balanced bilin- gual subjects would perform better on various cognitive tasks compared to dominant bilingual subjects. In addition, due to the fact that spontaneous cognitive flexibility requires more cogni- tive resources and more advanced executive abilities, the sec- ond hypothesis of the present study is that the the balanced bilinguals’ performance would be stronger in cognitive tasks which require spontaneous cognitive flexibility. Method Subjects Forty-nine right-handed young adults ranging in age from 20 to 35 years (M = 24.4, SD = 3.5) participated in this study. There were no significant differences between the mean ages of the three groups and none of the subjects in this study reported having either attention deficits or learning disabilities. There were three bilingual groups in this study: Balanced bilinguals (n = 17). Hebrew-dominant bilinguals (n = 17) and English-dominant bilinguals (n = 15). The criterion for being designated a bal- anced bilingual was that both English and Hebrew were used actively on a daily basis since early childhood. Most of the balanced bilingual subjects had grown up in “mixed” families where one of the parents spoke English as a native language and the other spoke native Hebrew. Some subjects came from homes (in Israel) in which both parents spoke English, and were therefore exposed to both languages since infancy. In addition, some of the subjects in this group resided for varying periods in an English-speaking country. Subjects in the Hebrew-dominant group were young Israeli adults who speak Hebrew as a native language and were not functionally fluent in any other language. The subjects in the English-dominant group were foreign students who came to Israel for academic studies. English was their native tongue and they were not fluent in any other language. Tools and Procedure Language Background Questionnaire All subjects completed a language background questionnaire to establish their language history and patterns of language use. For each language known to the subject, three dimensions of language fluency (spoken production, reading and writing) were rated on a 6-point scale ranging from not fluent at all (0) to extremely fluent (5). Subjects in the balanced-bilingual group rated themselves as being highly fluent both in Hebrew (aver- age of the three language dimensions: M = 4.98, SD = 0.35) and in English (average of the three language dimensions: M = 4.73, SD = 0.26) while subjects in the other two groups rated them- selves as being highly fluent only in one language. Although the data reveal higher self-reported second language profi- ciency of the Hebrew-dominant group (M = 3.3) than the Eng- lish-dominant group (M = 1.9), the background data reported by the subjects reinforces the distinction between the balanced- bilingual group who were exposed to two languages from early childhood and the other two groups who reported acquiring the second language later in life without using it on a daily basis. It is possible that cultural factors partly explain the differences in self-evaluations, that is, an over-estimation of the Hebrew-do- minant group’s English skills. In order to ensure that the balanced bilingual group had met the research criteria of speaking Hebrew and English since early childhood, the subjects in this group completed an addi- tional language questionnaire. In this questionnaire, they were asked to indicate the percentage of time in which each language had been used during three periods of their life: language usage at home, at school (or university) and with friends. The bal- anced-bilingual group reported using Hebrew 52.8% of the time up to the age of 12 years. Between 12 to 18 years they reported using Hebrew 61.7% of the time and 59.3% in their adulthood. These findings are displayed in Table 1. 1) Background measures In order to partial out the influence of verbal and non-verbal general intelligence as well as memory capacity, the following tasks were administrated: Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (Raven, 1958). This Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 3  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 4 Table 1. Mean percentage of time usage (means and standard deviations in parentheses) of Hebrew across the life-span among balanced bilinguals. Home School/University Friends M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) Overall M (SD) Up to 12 years old 24.1 (23.8) 72.4 (33.1) 62.1 (30.2) 52.8 (25.4) Between 12 - 18 years old 24.1 (23.73) 86.8 (16.58) 74.1 (23.4) 61.7 (33.12) Above 18 years old 27.1 (24.94) 78.4 (27) 72.4 (22.78) 59.3 (28.07) Note: Mean percentage of English-language time usage is the reciprocal of these figures. standardized test was originally designed as a measure of non- verbal reasoning ability. The test contains five sets, each of 12 items (A to E). In each test item, the subject is asked to identify the missing segment required to complete a larger pattern. All items are presented in black ink on a white background. Both the sets and the items within each set are arranged in order of difficulty. Subjects are given a score for each correct answer, and a general summary score is also calculated. Vocabulary (Wechsler, 1981). The vocabulary subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) was administered in order to assess general verbal intelligence. This test consists of 33 words (the Hebrew version) or 35 words (the English version) which the subject has to define. The English version of the test was administered to the English-dominant bilingual group, while the Hebrew version was administered to both the Hebrew-dominant bilingual group and the balanced bilingual group. Depending on the definition given by the sub- ject, each response was awarded up to two points. The general raw score was converted into a standardized score based on subjects’ age. Digit Span (forward and backward). This task was used as a measure of verbal memory capacity. It has two parts (digit span forward and digit span backwards)—each composed of a series of digit strings. Subjects were required to repeat each string of digits after it had been spoken by the experimenter—in the same order (digit span forward) or in reverse order (digit span backwards). There are two trials at each string length (ranging from two to nine). Each part of the task was discontinued when two consecutive errors at the same string length were made. The overall score in each part was the total number of correct digit series reproduced by the subject. An average score for performance on both parts was calculated. Wechsler Memory Scale III Spatial Span (forward and backward). This task, a measure of visual-spatial memory span, contains two parts (spatial span forward and spatial span back- wards). Ten cubes are attached to a board in an irregular ar- rangement. In each trial, the experimenter taps the blocks in a prearranged sequence (which varies from a sequence of two to eight cubes). The subject is required to reproduce the tapping pattern as it was presented (spatial span forward) or in the re- verse order (spatial span backwards). Each part of the task was discontinued when two consecutive errors at the same sequence length were made. The overall score for each part was the number of correct sequences tapped by the subject. An average score for performance on both parts was also calculated. 2) Experimental measures a)Spontaneous cognitive flexibility In order to assess spontaneous cognitive flexibility, the fol- lowing tasks were administered: Alternate Uses (adapted from: Guilford, Christensen, Merri- field & Wilson, 1978). In the “Alternate Uses” Task each sub- ject is asked to think beyond the common or conventional use of six objects, and to think up as many alternate uses as come to mind during 80 seconds for each object. The objects were—a bed sheet, a paper clip, a shoe, a cardboard box, an automobile tire and a drinking glass. Acceptable responses were conceiv- able uses that were different from each other and different from the common use. The overall score was the number of accept- able responses for all six objects. Design Fluency (Jones-Gotman & Milner, 1977). The Design Fluency Task was administered according to procedures de- veloped by Jones-Gotman and Milner (1977). Each subject was given four minutes in which to come up with as many different kinds of drawings as s/he could, using four lines, straight or curved, each time. The subject was instructed not to draw meaningful forms (such as the letter “W” or a square) and was shown examples of acceptable and unacceptable drawings. All repetitions were identified and subtracted from the total: these included rotations or mirror-image versions of previous draw- ings. In addition, all nameable drawings or drawings with an incorrect number of lines were also disqualified. The overall score was the number of remaining drawings. b) Reactive cognitive flexibility In order to assess reactive flexibility, two other tasks were also administered: WCST (Wisconsin Card Sort Task) (Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay, & Curtis, 1993): Each subject was given a set of 128 cards on which were printed up to four identical figures of either stars, crosses, triangles, or circles in one of four different colors. These figures were the basis for three sorting principles: color, form and number. At the beginning of the task, four stimulus key-cards were placed before the subject (one red triangle, two green stars, three yellow crosses and four blue circles). The instruction was to place each of the consecutive response cards in front of one of the stimulus cards, wherever it appears to match best. The subject is not informed of the correct sorting principle but was required to deduce this from the examiner’s responses to his or her placements of the cards (“right” or “wrong” feedback statements). After 10 consecutive correct sorts, the examiner shifted the to-be sorted principle without warning. This procedure continued until either five shifts of sorting category had been completed, or all cards were sorted. The ability to flexibly change response sets in this task was measured by three measures: the number of sorting steps re- quired to complete the first category (WCSTFC), the number of “total errors” (defined as the total number of incorrect sorting steps, WCSTTE) and the number of perseverative responses (defined as a sorting by the previous strategy after a correct  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. sorting by a new strategy, WCSTPR). In all of these measures, higher scores represent greater impairment (i.e. less cognitive flexibility). Trail Making Test (Reitan, 1979). The Trail Making Test contains two sub-sections accompanied by short sample items prior to the administration of each part. In part A, the subject is presented with a page with the numbers 1 through 25 and is required to draw a line connecting the numbers in order, as quickly as possible. In part B, a page is presented with the numbers 1 through 13 and the letters A through L (or the cor- responding Hebrew letters in the Hebrew version of the task). In this part, the individual’s task is to draw a line connecting the numbers and letters in order, alternating between numbers and letters (e.g. 1-A-2-B, etc.). Two scores were obtained, re- flecting the total time in seconds to complete each part (Tr1, Tr2 respectively). In this case, a lower figure indicates better performance. According to the Reitan (1979) administration format, errors are not scored, but when they occurred, the sub- ject was alerted to the mistake and instructed to correct it, thus slowing overall performance time. In order to create a score which reflects the ability to alternate between two sets of stim- uli (cognitive flexibility), another score was calculated by di- viding the performance time of Trails B by the performance time of Trails A (Tr2/Tr1). A higher score represents greater difficulties in performing this task. Results Background Measures Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations for the background measures by subject group. All subjects had normal scores on the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised (WAIS-R). A series of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were con- ducted. Since no significant gender effects were found, gender was ignored in all these analyses. No significant differences were found between the groups on the general raw scores of the Ra- ven’s Matrices, Digit Span Forward, Digit Span Backward or the combined (forward plus backward) measure. The Spatial Span Test also included forward and backward subtests. Whereas no significant differences were found between the groups on the forward subtest, the backwards subtest revealed a signifi- cant difference. Post-hoc Tukey comparisons revealed a just significant difference (p = 0.049) between the Hebrew-domi- nant group and English-dominant group. The combined means of the two subtests indicated no significant group differences. Experimental Measures Table 3 displays means and standard deviations (in paren- theses) on the experimental cognitive flexibility measures. Since there were specific predictions regarding a balanced- bilingual advantage over the other two groups on the cognitive flexibility measures, a series of planned comparisons (t-tests) were conducted. Results are shown in Table 4. Spontaneous cognitive flexibility was examined by two dif- ferent tests: Alternate Uses and Design Fluency. In the Alter- nate Uses Task, t-tests revealed a significant difference between the balanced-bilingual group and the Hebrew-dominant group. The estimated effect size was 0.292. No significant difference was found between the balanced- bilingual group and the English-dominant group, or between the Hebrew-dominant group and the English-dominant group. An additional two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted due to a significant influence of gender in which women had higher scores compared to men, F(3, 45) = 4.01, p = 0.05. However, no interaction was found between gender and group. In the Design Fuency Task, no significant differences were found between any of the three groups. Reactive cognitive flexibility was examined with two other tests; the Trail Making Test (TMT) and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). Planned comparisons (t-tests) for the TMT were conducted for the three measures. For Trails 1, no significant differences be- tween groups were found. However, on Trails 2, the He- brew-dominant group was found to be inferior (slower) than the balanced-bilingual group and the English-dominant group-the Table 2. Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) on background cognitive measures in three groups. Balanced bilinguals Hebrew dominant English dominant M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) F P Vocabulary 1.2 0.21 (WAIS-R) 15.9 (1.34) 16.1 (1.22) 14.3 (1.95) Raven 52.2 (3.05) 50.1 (4.00) 50.1 (5.28) 1.4 0.26 Digit span forward 11.8 (1.92) 10.7 (1.49) 11.3 (1.88) 1.54 0.22 Digit span backward 7.9 (2.52) 8(2.15) 8.4 (1.55) 0.25 0.78 Digit span combined 9.8 (2.00) 9.4 (1.54) 9.9 (1.25) 0.5 0.61 Spatial span forward 8.6 (2.03) 8.5 (2.18) 8.7 (2.00) 0.04 0.96 Spatial span backward 8.8 (1.70) 7.4 (1.69) 8.9 (1.92) 3.83 0.03* Spatial span combined 8.7 (1.48) 7.9 (1.56) 8.8 (1.71) 1.46 0.24 Note: *A Tukeypost-hoc comparisons revealed a significance difference (p = 0.049) between the Hebrew- dominant group and the English-dominant group. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 5  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Table 3. Means and standard deviations on experimental cognitive flexibility measures in three groups. Balanced bilinguals Hebrew dominant English dominant M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) Spontaneous flexibility Alternate Uses 29.4 (5.7) 22.3 (5.6) 26.4 (6.48) Design Fluency 30.8 (10.25) 29.5 (12.86) 33.5 (11.05) Reactive flexibility Trails 1 29 (5.06) 31.7 (6.05) 28.3 (7.44) Trails 2 52.8 (9.25) 61.1 (13.7) 51.4 (9.71) Tr2/Tr1 1.9 (0.36) 1.96 (0.47) 1.9 (0.54) WCSTFC 11.5 (2.35) 11.7 (2.5) 11.7 (2.4) WCSTTE 9.1 (3.32) 9.6 (3.79) ^ 8.5 (2.33) WCSTPR 5.7 (1.87) 6.4 (2.45) 5.8 (1.15) Table 4. Statistical comparisons between pairs of groups. Balanced bilinguals vs. Hebrew dominantBalanced bilinguals vs. English dominantHebrew dominant vs. English dominant t p Eta2 t p Eta2 t p Eta2 Alternate Uses 3.63 0.001* 0.292 1.37 0.18 −1.92 0.064 Design Fluenc y 0.32 0.75 −0.72 0.48 −0.94 0.36 Tr1 −1.4 0.165 0.31 0.76 1.43 0.16 Tr2 −2.01 0.047* 0.118 0.42 0.67 2.3 0.03* 0.148 Tr2/Tr1 −0.75 0.46 −0.35 0.73 0.29 0.77 latter two groups performed at similar levels. No significant differences were found between the groups on the proportion Tr2/Tr1. For the WCST, an aparametric analysis (Mann-Whitney Test) was conducted due to the abnormality of distribution. Results are shown in Table 5. As can be seen in Table 5, there were no significant differ- ences between the groups on any of the three measures. 1) Spontaneous versus reactive flexibility In order to explore the second hypothesis of the study, which predicted that the balanced-bilingual superiority would be greater in cognitive tasks which are assumed to tap spontaneous cognitive flexibility, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. Two composite measures of cogni- tive flexibility (spontaneous and reactive) were created: The spontaneous cognitive flexibility measure was an average of z scores on the Alternate Uses Task and the Design Fluency Task. In order to create the reactive cognitive flexibility composite, we tried different combinations of experimental measures (for example, combining z scores of the Trails 2 measure with z scores of all WCST measures, or mean z scores of Trails 2 and Trails 2/Trails 1 measures with all the WCST measures): the same pattern of results emerged. Using a reactive cognitive flexibility aggregate, which was a mean z scores of Trails 2, Trails 2/Trails 1 and all WCST z scores, the following results were obtained: No (pairwise) interactions were found between group and type of cognitive flexibility when comparing the balanced-bilingual group and the Hebrew-dominant group, F(1,32) = 0.534, p = 0.47; between the balanced-bilingual group and the English-dominant group, F (1,30) = 0.08, p = 0.78; and between the Hebrew-dominant group and the Eng- lish-dominant group, F (1,30) = 0.22, p = 0.64. The Alternate Uses Task is highly demanding from a cogni- tive point of view. It was found that subjects with greater executive capacity were better able to succeed in this task and produce novel uses of common objects (Gilhooly, Fioratou, Anthony, & Wynn, 2007). In the present study a highly significant difference between balanced-bilinguals and the Hebrew- dominant group was found on this task. If the difference between the groups is sig- nificantly greater than the difference between the groups in other less demanding experimental measures (including the Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 6  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Design Fluency Task which also measures spontaneous cogni- tive flexibility) then the assumption that bilingual experience enhances cognitive function will be strengthened. A series of repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted in order to explore this. Once again, standard- ized scores were created for the purposes of these analyses. Results are shown in Table 6. Results indicated that the superiority of the balanced bilin- gual group on the Alternate Uses Task (compared to the He- brew-dominant group) was more pronounced than in most of the Wisconsin measures (WCSTFC and WCSTTE) and in the Design Fluency Task. The interaction was close to significant with the combined measure of performance in the Trails Task (Tr2/Tr1). Discussion Previous studies have indicated that bilingualism contributes to the improvement of cognitive skills from childhood (Bialy- stok, 1999) and adults (Colzato et al., 2008). In the present study, an adult group of balanced bilinguals, who are equally competent in English and Hebrew, was com- pared to two different adult dominant-bilingual groups, each of which had fully mastered only one language. All groups were tested with a series of tests designed to tap two types of cogni- tive flexibility: reactive flexibility (tested using the Trail Mak- ing Test and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) and spontaneous flexibility (tested using the Alternate Uses test and the Design Fluency Task). The aim of the study was reach data that will ultimately lead to a better understanding of the nature and vari- ability of bilingual language and cognitive profiles. Our hy- pothesis regarding the priority of the balanced-bilingual group compared to the other two groups was partially confirmed. The pattern of results obtained in the present study showed that the English-dominant group outperformed the Hebrew-dominant group with significant differences emerging only between the Hebrew-dominant group and the balanced-bilingual group. In this context, similarly to previously reported findings us- ing task switching paradigms, bilingual subjects in the current study did not exhibit significant differences in this domain. In that regard, this result is similar to previous task switching studies in which bilinguals had smaller switch costs but equi- valent overall response times (Prior & Gollan, 2011; Prior & MacWhinney, 2010), but contrasts with findings from conflict resolution tasks, where overall speed advantages are robust (Costa et al., 2009; see also, Hilchey & Klein, 2011). Note that the balanced-bilingual group subjects as well as the subjects of the Hebrew-dominant group have lived all of their lives in Is- rael, excluding a few subjects from the balanced-bilingual group who spent part of their lives in an English speaking country. However, and interestingly, both in the Alternate Uses Task which represents spontaneous cognitive flexibility and in the Trails Task which represents reactive cognitive flexibility, the balanced-bilinguals were found to be superior to the He- brew-dominant group but not compared to those who mastered English as their primary language. Although the Hebrew-dominant group reported having more second language proficiency than the English-dominant group, it is possible that cultural proclivities led to over-estimation. The language histories of both language-dominant groups dif- fered from the distinctive pattern among the balanced-bilingual Table 5. Statistical comparisons (Mann-Whitney) between three groups. Balanced bilinguals Hebrew dominant Balanced bilinguals English dominant Hebrew dominant English dominant Z p Z p Z p WCSTFC 0 0.5 −0.084 0.47 −0.063 0.48 WCSTTE −0.035 0.48 −0.29 0.4 −0.057 0.48 WCSTPR −1.1 0.14 −1.13 0.14 −0.14 0.45 Note: WCSTFC : Wisconsin card sort task first category; WCSTTE: Wisconsin card sort task total error; WCSTPR: Wisconsin card sort task perseverative responses. Table 6. Interactions between balanced-bilinguals and the Hebrew-dominant group and the Alternate Uses Task versus other experimental measures. Z scores Z scores Task Balanced bilingualsHebrew-dominant Task Balanced bilingualsHebrew-dominant F p Trails 2 0.21 −0.50 0.7150.404 Tr2/Tr1 0.12 −0.12 3.21 0.08 WCSTFC 0.05 −0.02 5.08 0.03* WCSTTE −0.02 −0.11 4.8 0.036* WCSTPR 0.16 -0.24 1.91 0.176 WCST-composite 0.07 −0.12 4.5 0.04* Alternate uses 0.51 −0.57 Desflcr −0.03 −0.15 9.4 0.004* Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 7  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. group who had acquired both English and Hebrew in early childhood and used both languages on a daily basis throughout life. In addition, the pattern of results reported above reinforces the assumption that the Hebrew-dominant group overestimated it’s second language proficiency compared to the English- dominant group, since the raw scores on most experimental measures revealed better performance of the English-dominant group. Nonetheless, future research should examine language proficiency by directly evaluating language proficiency. In the Alternate Uses Task, the slight difference between the English-dominant and the Hebrew-dominant groups might be explained by the fact that foreign students were previously exposed in their natural environment to more possible uses of objects from this task. Also, the English-dominant group out- performed the Hebrew-dominant group in the second part of the Trails task which necessitates switching between numbers and letters. Most of the English letters in the Trails task contains only one syllable in contrast to the Hebrew letters which are mostly constructed of two syllables. This fact might be the reason for faster memory retrieval of the English alphabet and therefore for the superior performance of the English-dominant group in this part of the task. Yet, in spite of the putative cul- tural and linguistic advantages of the English-dominant subjects, this group did not outperform the balanced-bilingual group, suggesting genuine cognitive benefits of bilingualism. The second hypothesis of this study predicted that the bal- anced-bilingual group superiority should be greater in cognitive tasks which represent spontaneous cognitive flexibility com- pared to reactive cognitive flexibility tasks. Tasks which neces- sitate spontaneous cognitive flexibility pose a greater cognitive challenge because they require the formation of strategies for searching information in memory and often require a bypassing of automatic responses. Due to the fact that the research sub- jects were primarily high-functioning individuals (students), we hypothesized that the benefits of bilingualism would be more pronounced in tasks which are more cognitively challenging. However, the results of the present study, using two composite measures of the experimental tasks, did not reveal an interac- tion between group and type of cognitive flexibility. Nonethe- less, comparing the two tasks where there was a significant dif- ference between the balanced-bilingual group and the Hebrew- dominant group, showed that the difference between the groups showed twice as much variance in the Alternate Uses Task which requires spontaneous cognitive flexibility than in the Trails task which taps reactive cognitive flexibility. These results demonstrate that the type of linguistic experi- ence (balanced/dominant bilingualism) has more influence on a task which necessitates spontaneous cognitive flexibility. The Alternate Uses Task has the highest cognitive demands among all research tasks. The performance of the balanced- bilingual group compared to the Hebrew-dominant group was significantly better in this task than in most experimental meas- ures. This finding reinforces results of previous studies demon- strating the cognitive benefits of bilingualism (Gilhooly et al., 2007). The Alternate Uses Task involves several executive proc- esses. According to Gilhooly et al. (2007), initial responses in this task are based on a strategy of retrieval from long term memory of already known alternate uses associated with past experience with the target objects. After the initial automatic retrievals have been exhausted, more effortful and executively loading strategies are used in order to find novel alternate uses. Two main executive processes, which are involved in the use of strategies, are inhibition and switching (Baddeley, 2003; Mi- yake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, & Howerter, 2000). In the Alternate Uses Task, the dominant use of the object must be inhibited. In addition, the memory strategy requires inhibition of earlier produced dominant memories as the process contin- ues to produce responses. Furthermore, possible responses will have to be evaluated for suitability and unsuitable ones inhib- ited. A decision must be made as to when to switch from the memory strategy to one of the other strategies. Further deci- sions about switching from one attribute of an object to another are also required in addition to inhibition of previously used cues. Gilhooly et al. (2007) found that subjects with greater execu- tive capacity were better able to switch to more demanding strategies and produce novel alternate uses which were not based on personal past experience. It is possible that life-long bilingual experience requiring consistent switching between two languages along with inhibi- tion of the irrelevant language depending on the situation, con- tributed to the balanced-bilinguals advantage in this task which is based on the executive functions of inhibition and switching. The Alternate Uses Task is considered to be a divergent thinking task (Guilford, Christensen, Merrifield & Wilson, 1978). According to Boden’s (2004: p. 2) terminology, diver- gent production tasks involve “personal-psychological creativ- ity”, i.e., producing an idea that is new to the person who pro- duces it, irrespective of how many people have had the idea before. In validation studies, divergent tests have been found to be better correlated with real life measures of creative behavior, such as gaining patents, producing novels and plays, founding businesses or professional organizations (Plucker, 1999), than with convergent tests of intelligence such as Raven’s Matrices. Future research should examine the relationship between bilin- gualism and creativity in adults using additional divergent thinking tasks like the present Alternate Uses Task. Previous studies among adults reporting a bilingual advan- tage in tasks based on executive functions have used tasks which are based on visuo-spatial perception such as the Simon Task (Bialystok et al., 2004) or the Antisaccade Task (Bialy- stok, Craik, & Ryan, 2006). However, in a few cases, the re- sults have not been fully replicated when the Simon Task was used (Bialystok, Martin, & Viswanathan, 2005). Furthermore, a recent investigation found that daily experience in bilingualism or massive musical training which engages executive control can be generalized to other domains in which executive func- tions are also required (Bialystok & DePape, 2009). The greatest effect was found in tasks which are similar to the type of activity involved in the experience. Therefore we believe that this may reflect the different modality of the task. The results of the present study, in which the balanced-bilingual group's advantage in spontaneous cognitive flexibility tasks was found in a linguistic task (Alternate Uses) and not in a task which is based on spatial perception (Design Fluency), need further research in order to elaborate the linguistic aspect and explore the consistency of the bilingual advantage in linguistic tasks which involve higher cognitive functions. Conclusion and Future Research In this study, we hypothesized that balanced bilingual sub- jects would have superiority in the above tasks compared to Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 8  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. dominant bilingual subjects. We hypothesized that the superior- ity of the balanced bilinguals would be greater in cognitive tasks which required spontaneous cognitive flexibility appar- ently, due to the fact that spontaneous cognitive flexibility re- quired more cognitive resources and more advanced executive abilities than reactive cognitive flexibility. Results of the pre- sent study demonstrated an advantage of bilingualism only compared to individuals who share the same culture. No inter- action was found between group and type of cognitive flexibil- ity. The present study has a limitation that the reader should take into consideration. The background experiences of the three groups were not the same, since the Hebrew-dominant group grew up in Israel while English-dominant group were foreign students studying in Israel. Therefore, it may well be that the educational qualifications of these two groups differ. In order to substantiate the findings of this study, it is therefore warranted to conduct further research using bilinguals who have mastered two closely related languages such as English and Spanish and two dissimilar languages such as Chinese and Arabic. For the Arabic speaking group, it is suggested that the study be repli- cated with attention paid to the diglossic context existing for the Arab readers. This should include more rigorous control re- garding the familiarity of the items in both spoken and literary Arabic as it has proved that the distance between the two forms constitute a kind of bilingualisim and has an impact on lexical representation (Ibrahim & Aharon-Peretz, 2005), cognitive (Ibrahim, 2010) and metacognitive processess (Eviatar & Ibra- him, 2001). REFERENCES Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, 417-423. doi:10.1038/nrn1201 Bialystok, E. (1993). Metalinguistic awareness: The development of children’s representations of language. In C. Pratt, & A. Garton (Eds.), Systems of representation in ch ildren: Development and use (pp. 211 – 233). London: Wiley & Sons. Bialystok, E. (1999). Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind. C hil d Deve lopm ent , 70 , 636-644. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00046 Bialystok, E. (2010). Global-local and trail-making tasks by monolin- gual and bilingual children: Beyond inhibition. Developmental Psy- chology, 46, 93-105. doi:10.1037/a0015466 Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., Grady, C., Chau, W., Ishii, R., Gunji, A., & Pantev, C. (2004). Effects of bilingualism on cognitive control in the simon task: Evidence from MEG. Neur oimage , 24, 40-49. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.044 Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., Klein, R., & Viswanathan, M. (2004). Bi- lingualism, aging and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychology and Aging, 19, 290-303. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.290 Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., & Ryan, J. (2006). Executive control in a modified antisaccade task: Effects of aging and bilingualism. Jour- nal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 32, 1341-1354. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.32.6.1341 Bialystok, E., & De Pape, A. M. (2009). Musical expertise, bilingual- ism and executive functioning Journal of experimental psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 565-574. doi:10.1037/a0012735 Bialystok, E., Martin, M. M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005). Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. Interna- tional Journal of Bilingualism, 9, 103-119. doi:10.1177/13670069050090010701 Boden, M. (2004). The creative mind. 3rd Edition. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Brysbaert, M. (1998). Word recognition in bilinguals: Evidence against the existence of two separate lexicons. Psychologica Belgica, 38, 163- 175. Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. M. (2008). Bilingual experience and ex- ecutive functioning in young children. Developmental Science, 11, 282-298. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x Colzato, L. S., Bajo, M. T., van den Wildenberg, Paolieri D., Nieu- wenhuis, S., La Heij, W., & Hommel, B. (2008). How does bilingua- lism improve executive control? A comparison of active and reactive inhibition mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Ps ychology: Lea rning, Memory and Cognition, 34, 302-312. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.34.2.302 Cicerone, K. D., Lazar, R. M., & Shapiro, W. R. (1983). Effects of frontal lobe lesions on hypothesis sampling during concept formation. Neuropsychologia, 21, 513-524. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(83)90007-6 Costa, A., Hernandez, M., & Sebastian-Gall’s, N. (2008). Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition, 106, 59-86. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013 Cromdal, J. (1999). Childhood bilingualism and metalinguistic skills: Analysis and control in young Swedish-English bilinguals. Applied Psycholin guistics, 20, 1-20. doi:10.1017/S0142716499001010 Eslinger, P. J., & Grattan, L. M. (1993). Frontal lobe and frontal-striatal substrates for different forms of human cognitive flexibility. Neuro- psychologia, 31, 17-28. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(93)90077-D Eviatar, Z., & Ibrahim, R.. (2001). Bilingual is as bilingual does: Meta- linguistic abilities of Arabic-speaking children. Applied Psycholin- guistics, 21, 451-471. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(93)90077-D Gilhooly, K. J., Fioratou, E., Anthony, S., & Wynn, V. (2007). Diver- gent thinking: Strategies and executive involvement in generating novel uses for familiar objects. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 611- 625. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2007.tb00467.x Guilford, J. P., Christensen, P. R., Merrifield, P. R., & Wilson, R. C. (1978). Alternate uses : Manual of instructions and interpretation s. Or- ange, CA: Sheridan Psychological Services. Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of bilingual lexico-semantic sys- tem. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1, 67-81. doi:10.1017/S1366728998000133 Grosjean, F. (1988). Exploring the recognition of guest words in bilin- gual speech. Language and Cognitive Processes, 3, 233-274. doi:10.1080/01690968808402089 Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. M. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental science, 11, 282-298. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x Colzato, L. S., Bajo, M. T., van den Wildenberg, Paolieri, D., Nieu- wenhuis, S., La Heij, W., & Hommel, B. (2008). How does bilin- gualism improve executive control? A comparison of active and re- active inhibition mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition, 34, 302-312. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.34.2.302 Cicerone, K. D., Lazar, R. M., & Shapiro, W. R. (1983). Effects of frontal lobe lesion on hypothesis sampling during concept formation. Neuropsychologia, 21, 513-524. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(83)90007-6 Costa, A., Hernandez, M., & Sebastian-Gall’s, N. (2008). Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition, 106, 59-86. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013 Cromdal, J. (1999). Childhood bilingualism and metalinguistic skills: Analysis and control in young Swedish-English bilinguals. Applied Psycholin guistics, 20, 1-20. doi:10.1017/S0142716499001010 Eslinger, P. J., & Grattan, L. M. (1993). Frontal lobe and frontal-striatal substrates for different forms of human cognitive flexibility. Neuro- psychologia, 31, 17-28. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(93)90077-D Eviatar, Z., & Ibrahim, R.. (2001). Bilingual is as bilingual does: Me- talinguistic abilities of Arabic-speaking children. Applied Psycholin- guistics, 21, 451-471. doi:10.1017/S0142716400004021 Ilhooly, K. J., Fioratou, E., Anthony, S., & Wynn, V. (2007). Divergent thinking: Strategies and executive involvement in generating novel uses for familiar objects. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 611-625. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2007.tb00467.x Guilford, J. P., Christensen, P. R., Merrifield, P. R., & Wilson, R. C. (1978). Alternate uses : Manual of instructions and interpretation s. Or- ange, CA: Sheridan Psychological Services. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 9  R. IBRAHIM ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 10 Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of bilingual lexico-semantic sys- tem. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1, 67-81. doi:10.1017/S1366728998000133 Grosjean, F. (1988). Exploring the recognition of guest words in bilin- gual speech. Language and Cognitive Processes, 3, 233-274. doi:10.1080/01690968808402089 Heaton, R. K., Chelune, G. J., Talley, J. L., Kay, G. G., & Curtis, G. (1993). Wisconsin card sorting test manual: Revised and expanded. Odessa, TX: Psychological Assessment Resources. Hilchey, M. D., & Klein, R. M. (2011). Are there bilingual advantages on nonlinguistic interference tasks? Implications for the plasticity of executive control processes. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 18, 625-658. doi:10.3758/s13423-011-0116-7 Hornby, P. A. (1977). Bilingualism: Psychological, social and educa- tional implications. New York: New York Academic Press, Inc. Ianco-Worrall, A. (1972). Bilingualism and cognitive development. Child Devel opment, 43, 1390-1400. doi:10.2307/1127524 Ibrahim, R. (2010). Literacy problems in Arabic: Sensitivity to diglossia in tasks involving working memory. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 23 , 427-442. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2010.04.002 Ibrahim, R., & Aharon-Peretz, J. (2005). Is literary Arabic a second language for native Arab speakers? Evidence from a semantic prim- ing study. The Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 34, 51-70. doi:10.1007/s10936-005-3631-8 Jackson, G. M., Swainson, R., Cunnington, R., & Jackson, S. R. (2001). ERP correlates of executive control during repeated language swit- ching. Bilingualism: L an g u a g e a n d cognition, 4, 169-178. doi:10.1017/S1366728901000268 Jones-Gotman, M., & Milner, B. (1977). Design fluency: The invention of nonsense drawings after focal cortical lesions. Neuropsychologia, 15, 653-674. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(77)90070-7 Kiesel, A., Steinhauser, M., Wendt, M., Falkenstein, M., Jost, K., Philipp, A. M., et al. (2010). Control and interference in task switch- ing—A review. Psychologic al Bullet in, 136, 849-874. doi:10.1037/a0019842 Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Languag es , 33, 149-174. doi:10.1006/jmla.1994.1008 Lambert, W. E., Havelka, J., & Gardner R. C. (1959). Linguistics mani- festations of bilingualism. American Journal of Psychology, 72, 77- 82. doi:10.2307/1420213 Lu, C. H., & Proctor, R. W. (1995). The influence of irrelevant location information on performance: A review of the Simon and spatial Stroop effects. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2, 174-207. doi:10.3758/BF03210959 Meiran, N. (2010). Task switching: Mechanisms underlying rigid vs. flexible self control. In R. Hassin, K. Ochsner, & Y. Trope (Eds.), Self control in society, mind and brain (202220). New York: Oxford University Press. Milner, B., & Petrides, M. (1984). Behavioral effects of frontal-lobe lesions in man. Trends in Neuroscience, 7, 403-407. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(84)80143-5 Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., & How- erter, A. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychol ogy, 41, 49-100. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 Plucker, J. A., & Renzulli, J. S. (1999). Psychometric approaches to the study of human creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of crea- tivity (pp. 49-100). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Prior, A., & Gollan, T. (2011). Good language switchers are good task switchers: Evidence from Spanish-English and Mandarin-English bi- linguals. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17, 682-691. doi:10.1017/S1355617711000580 Prior, A., & MacWhinney, B. (2010). A bilingual advantage in task switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13, 253-262. doi:10.1017/S1366728909990526 Raven, J. C. (1958). Standard progressive matrices. London: Lewis. Reitan, R. M. (1979). Manual for administration of neuropsychologi- cal test batteries for adults and children. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsy- chology Laboratory. Spiro, R., & Jehng, J. (1990). Cognitive flexibility and hypertext: The- ory and technology for the nonlinear and multidimensional traversal of complex subject matter. In D. Nix, & R. Spiro (Eds.), Cognition, education and multimedia: Explor- ing ideas in high technology (pp. 163-205). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Wechsler, D. (1981). Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised: Man- ual. New York: Psychological Corp. Wei, L. (2000). The bilingualism reader. London: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group. Zied, K. M., Phillipe, A., Karine, P., Valerie, H.-T., Ghislaine, A., Arnaud, R., et al. (2004). Bilingualism and adult differences in in- hibitory mechanisms: Evidence from a bilingual stroop task. Brain and Cognition, 54, 254-256. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.02.036

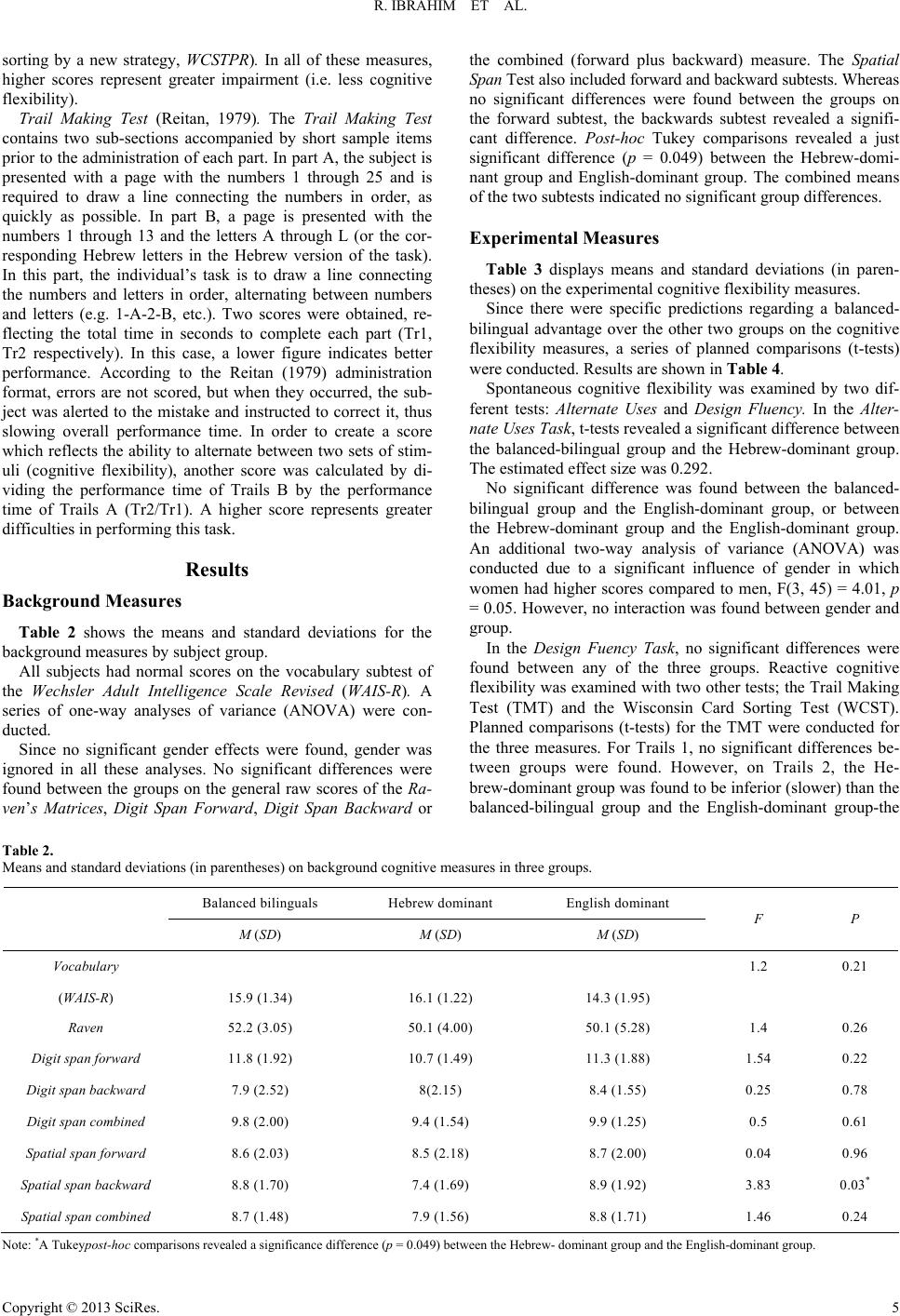

|