Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

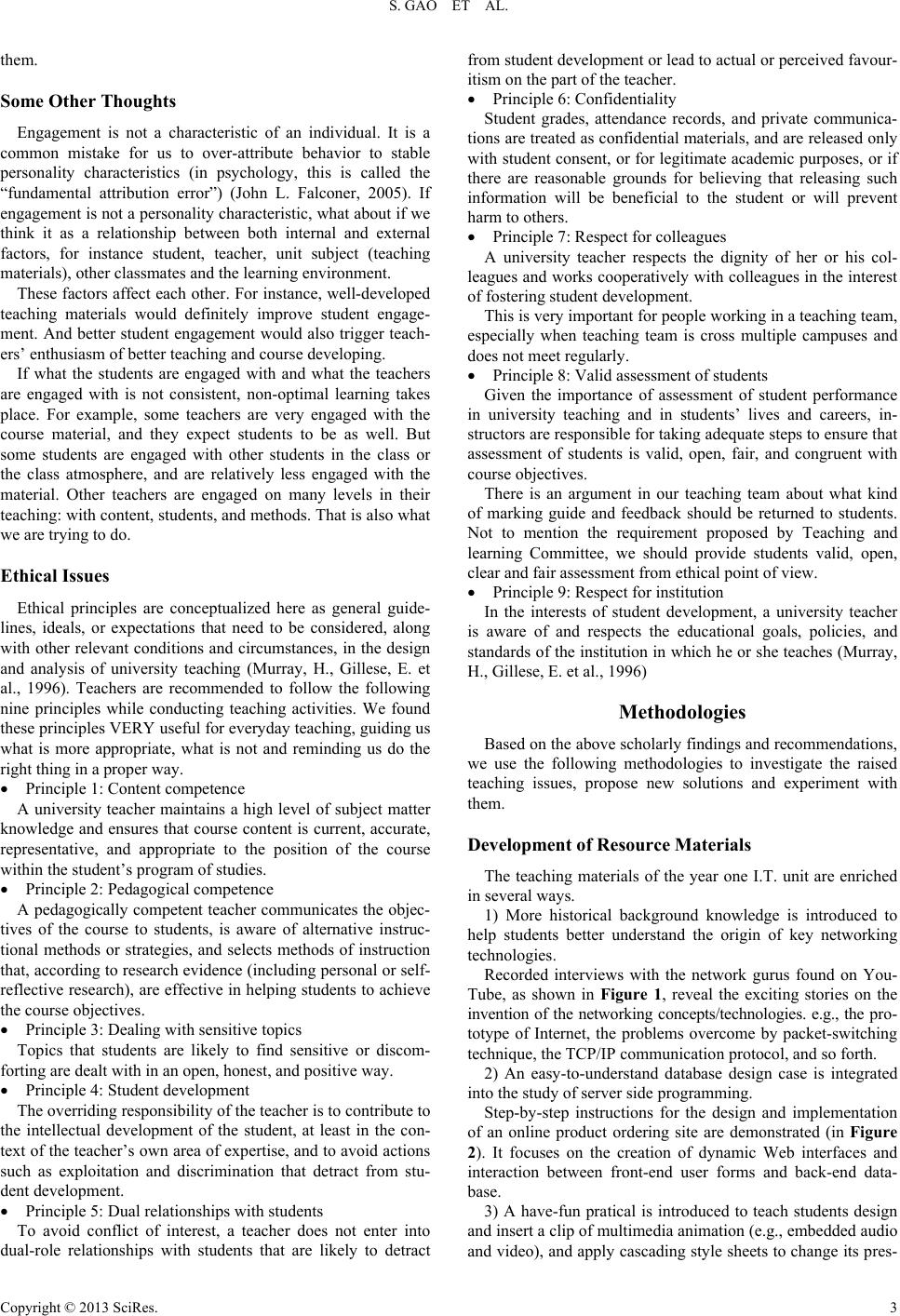

Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.7A2, 1-7 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.47A2001 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 1 Approaches to Improving Teaching Shang Gao, Jo Coldwell-Neilson, Andrzej Goscinski School of Information Technology, Deakin University, Waurn Ponds, Australia Email: shang@deakin.e du.au, jo.neilson@deakin.edu.au, andrzej.goscinski@deakin.edu.au Received May 29th, 2013; revised June 28th, 2013; accepted July 5th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Shang Gao et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons At- tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This paper discusses a few issues related to teaching improvement that are commonly found in tertiary education, such as curriculum development, student engagement, and ethical considerations. Scholars re- search on resolving these issues are investigated. Corresponding approaches to improving teaching of a year one information technology unit are proposed and experience is shared. The importance of teaching scholarship is also emphasized at the end of this paper. Keywords: Tertiary Education; Curriculum Development; Teaching Improvement; Student Engagement; Scholarship of Teaching; Ethical Considerations; Teaching in Information Technology Introduction In the past few years, we have been teaching a first year In- formation Technology unit “SIT104 Introduction to Web De- velopment” at Deakin University. It focuses on how to build a dynamic website by using hypertext markup language, Cascad- ing style sheets, Client side and Server side programming over the WWW framework. Student s explore on-line Web pages and use a variety of HTML tags taught in practical labs and classes to organize and publish information. Every year we have new student cohort which might be slightly different from those of previous years. We attempt different teaching approaches every time and always find new issues. In this paper we would like to share our teaching ex- perience and approaches effectively used throughout these years and hope they are helpful and beneficial to other teaching scholars. The issues found are mainly relevant to curriculum develop- ment and student engagement. Issue 1: Curriculum Development When initially developing teaching materials for SIT104, we aim at providing a unit which helps students not only develop a basic understanding of website design ideas, but also situate those ideas within a broader portrait of advanced web-based ap- plication. It should not focus on particular web authoring tools (e.g. Dreamweaver, or Frontpage) nor even on isolated “skills” (e.g. how to write a conditional program), but rather on the ways in which these technologies have impacted Web design and development. The unit includes topics such as: 1) A variety of examples demonstrating what are good web design and what are not; 2) The notion of a “language” and basic ideas of procedural programming, such as Javascript; 3) Computational models of generic web-based applications, and how they have affected the choice of language, platform and interface; 4) How computational models enable us to create many com- plex web applications as a collection of interactive entities; 5) The notion of “communication” and “information shar- ing”. The practical materials we provide each week are quite in- formative. For some students, reading such a “lengthy” practi- cal is time consuming and boring, especially when they have attended lectures and sometimes the important concepts have been emphasized. At the sa me time, however, for some st ude nts, especially these off-campus students and these who do not usu- ally attend lectures, the detailed practicals provide much infor- mation about the basic and important elements of web devel- opment. They appreciate such kind of “lengthy” practicals and feel like they were sitting in a classroom while reading them. The first question raised is how to balance between being too “lengthy” and being too “concise” when developing teaching materials for different cohort of students? Issue 2: Student Engagement It might be a common phenomenon that there are always some students who prefer sitting at the back of a classroom, talking to each other or doing something else during a lecture. This situation might frustrate teachers to some extent. Is it be- cause the content is not attractive enough? Should more exam- ples be provided to attract students’ attention? Or should teach- ers try to eye contact these students to “remind” them? Are there any effective ways to improving student engagement in class and practical lab? Before answering these questions, first we need to find out what other teaching scholars have done, what good approaches have been investigated and proposed. Then based on the proved teaching improving techniques, we propose our own solutions, while combining our actual situation. This paper is organized as foll ows: Introduction section ra ises  S. GAO ET AL. two teaching issues, followed by literature review relating to the above issues and current practice. A description of adopted methods is included in methodologies part, followed by a con- clusion. Literature on the Scholarship of Teaching There are quite a lot of teaching scholars have been investi- gating and proposing the answers to these above questions. Curriculum Development Grenert, Judith (Judith Grenert, 2006) suggested that every course we develop is a lens into our fields and our personal conceptions of those disciplines. We need to give careful thought to the shape and content of our course. Before the development, we would better ask ourselves the following questions: How does the course begin? Why does it begin where it does? How does our course fit within a larger conception of curriculum, program, and teaching? How do we lecture about or lead discussions around? What are the key assignments or student evaluations? ( What are the main points of the argument? What are the key bod- ies of evidence?) What do we want to persuade our students to believe? Or question? Or do we want them to develop new appetites or dispositions? Are there distinctly different ways to organize our course- ways that reflect quite different perspectives on our disci- pline or field? Do we focus on particular topics while other colleagues might make other choices? Why? How does our course connect with other courses in our own or other fields? To what extent does our course lay a foun- dation for others that follow it? Or build on what students have learned in other courses? Where will our students encounter the greatest difficulties of either understanding or motivation? How does the con- tent of our course connect to matters our students already understand or have experienced? Where will it seem most alien? How do we address these common student responses in our course? How has the course evolved over time in response to them? Professor John L. Falconer from University of Colorado at Boulder found that teaching could be improved in an effort to increase the understanding of the concepts and engage the stu- dents more in class (John L. Falconer, 2005). Student Engagement Professor Bill Briggs at University of Colorado at Denver has been studying student engagement with his colleagues since 2000. They tried to define and measure student engagement and proposed six components of engagement. Here lists each component and one or two representative items (Bill Briggs, 2005): Skills Engagement. e.g. “Sitting toward the front of the class, where it’s easier to pay attention.” “Taking good notes in class.” Emotional Engagement. e.g. “Applying course material to my life.” “Really desiring to learn the material.” Performance Engagement. e.g. “Getting a good grade.” “Doing well on the tests.” Participation Engagement. e.g. “Asking questions when I don’t understand the instructor.” Interactio n Engageme nt. e.g. “Helping fellow students.” Fun Engagement. e.g. “Having fun in class.” Professor Bill also suggested that important aspects of en- gagement are not necessarily observable, but they are related to other aspects of the learning process. For instance, emotional engagement, interaction engagement, and fun engagement are not easily observable by teachers. How- ever, they (and the other components of engagement) are re- lated to the following (Bill Briggs, 2005): Self-reports of engagement were related to emotional, in- teraction, and fun components of engagement. The self-re- ports were NOT related to the other, more observable, components of engagement. If this is true, it is not surprise that sometimes students and teachers may have different understanding of students’ en- gagement. Incremental and entity self-theor ies. Carol Dweck (1999) classified students according to whether they hold an entity or incremental theory of learning. Entity theorists believe they have a predetermined capacity for learn- ing; the “container” may be large, but it is limited. Incremental theorists (who do better at various learning and life tasks) be- lieve that the capacity for learning can be extended and that the container can be stretched in various directions. It is probably much easier for us to understand emotional and interaction engagement than the other parts of engagement and self-theories. Learning and performance goals. Dweck (1999) also proposed that some students set learning goals that are related to increasing their competence, and that other students set performance goals that are more concerned with gaining favorable judgments of their competence (but ac- tually hinder learning). It was found that engagement is related to goals: Students whose primary orientation was performance were more perfor- mance engaged, while students with a learning orientation were higher in emotional, participation, interaction, and fun engage- ment. Is engagement related to grades? The answer is Yes. It was found that skills and participation engagement were related to grades on homework assignments, performance and fun engagement were related to midterm grades, and participation engagement was related to final exam grades. Students in upper-division courses were more interaction and fun engaged than students in lower-division courses. Clearly, engagement is different in different courses. It may also be seen evidence of a developmental process whereby students master the more elemental aspects of en- gagement (e.g., participation, skills) in lower division courses, and develop other levels of engagement (e.g., their ability to relate to other students, relate to teachers, and derive more fun from their courses) in more advanced courses. We also found similar phenomenon from our experience of teaching master units, undergraduate year three units and un- dergraduate year one units. Year one units are the hardest to teach mostly because first year students are still building up their independent learning skills and trying to get familiar with university life. Fun engagement is seemed a good way to help Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 2  S. GAO ET AL. them. Some Other Thoughts Engagement is not a characteristic of an individual. It is a common mistake for us to over-attribute behavior to stable personality characteristics (in psychology, this is called the “fundamental attribution error”) (John L. Falconer, 2005). If engagement is not a personality characteristic, what about if we think it as a relationship between both internal and external factors, for instance student, teacher, unit subject (teaching materials), other classmates and the learning environment. These factors affect each other. For instance, well-developed teaching materials would definitely improve student engage- ment. And better student engagement would also trigger teach- ers’ enthusiasm of better teaching and course developing. If what the students are engaged with and what the teachers are engaged with is not consistent, non-optimal learning takes place. For example, some teachers are very engaged with the course material, and they expect students to be as well. But some students are engaged with other students in the class or the class atmosphere, and are relatively less engaged with the material. Other teachers are engaged on many levels in their teaching: with content, students, and methods. That is also what we are trying to do. Ethical Issues Ethical principles are conceptualized here as general guide- lines, ideals, or expectations that need to be considered, along with other relevant conditions and circumstances, in the design and analysis of university teaching (Murray, H., Gillese, E. et al., 1996). Teachers are recommended to follow the following nine principles while conducting teaching activities. We found these principles VERY useful for everyday teaching, guiding us what is more appropriate, what is not and reminding us do the right thing in a proper way. Principle 1: Content competence A university teacher maintains a high level of subject matter knowledge and ensures that course content is current, accurate, representative, and appropriate to the position of the course within the student’s program of studies. Principle 2: Pedagogical competence A pedagogically competent teacher communicates the objec- tives of the course to students, is aware of alternative instruc- tional methods or strategies, and selects methods of instruction that, according to research evidence (including personal or self- reflective research), are effective in helping students to achieve the course objectives. Principle 3: Dealing with sensitive topics Topics that students are likely to find sensitive or discom- forting are dealt with in an open, honest, and positive way. Principle 4: Student development The overriding responsibility of the teacher is to contribute to the intellectual development of the student, at least in the con- text of the teacher’s own area of expertise, and to avoid actions such as exploitation and discrimination that detract from stu- dent development. Principle 5: Dual relationships with students To avoid conflict of interest, a teacher does not enter into dual-role relationships with students that are likely to detract from student development or lead to actual or perceived favour- itism on the part of the teacher. Principle 6: Confidentiality Student grades, attendance records, and private communica- tions are treated as confidential materials, and are released only with student consent, or for legitimate academic purposes, or if there are reasonable grounds for believing that releasing such information will be beneficial to the student or will prevent harm to others. Principle 7: Respect for colleagues A university teacher respects the dignity of her or his col- leagues and works cooperatively with colleagues in the interest of fostering student development. This is very important for people working in a teaching team, especially when teaching team is cross multiple campuses and does not meet regularly. Principle 8: Valid assessment of students Given the importance of assessment of student performance in university teaching and in students’ lives and careers, in- structors are responsible for taking adequate steps to ensure that assessment of students is valid, open, fair, and congruent with course objectives. There is an argument in our teaching team about what kind of marking guide and feedback should be returned to students. Not to mention the requirement proposed by Teaching and learning Committee, we should provide students valid, open, clear and fair assessment from ethical point of view. Principle 9: Respect for institution In the interests of student development, a university teacher is aware of and respects the educational goals, policies, and standards of the institution in which he or she teaches (Murray, H., Gillese, E. et al., 1996) Methodologies Based on the above scholarly findings and recommendations, we use the following methodologies to investigate the raised teaching issues, propose new solutions and experiment with them. Development of Resource Materials The teaching materials of the year one I.T. unit are enriched in several ways. 1) More historical background knowledge is introduced to help students better understand the origin of key networking technologies. Recorded interviews with the network gurus found on You- Tube, as shown in Figure 1, reveal the exciting stories on the invention of the networking concepts/technologies. e.g., the pro - totype of Internet, the problems overcome by packet-switching technique, the TCP/IP communication protocol, and so forth. 2) An easy-to-understand database design case is integrated into the study of server side programming. Step-by-step instructions for the design and implementation of an online product ordering site are demonstrated (in Figure 2). It focuses on the creation of dynamic Web interfaces and interaction between front-end user forms and back-end data- base. 3) A have-fun pratical is introduced to teach students design and insert a clip of multimedia animation (e.g., embedded audio and video), and apply cascading style sheets to change its pres- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 3  S. GAO ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 4 Figure 1. Video screenshot of internet history documentary. Figure 2. Screenshot of step-by-step database design case.  S. GAO ET AL. entation on screen. 4) Multiple choice question (MCQ) quizzes are created to encourage students’ performance engagement. We create a few sets of 50 multiple choice question (MCQ) quizzes to test students, collecting statistical data about their learning performance, as shown in Figure 3. The quizzes are carried out anonymously in class. Students are encouraged to take notes on the quiz sheets and keep them for later unit revi- sion. Quiz answers are gone through right after the in-class quiz so that students know where they make a mistake and the rea- son. Since the results are released right after the test, the stu- dents have motivation to participate. The score ranges are sta- tistically collected so that we teachers know the score distribu- tion used for future content adjustment. For instance, how many students get more than 40 (out of 50) questions correct; how many achieve between 30 to 40, and 20 to 30, etc. The ques- tions that most students failed are also highlighted, and revised into another form of question for next quiz, to track the im- provement of students’ understanding of the same topic. As the quizzes are anonymous and only used for locating dif- ficult knowledge points and improving teaching, but for pun- ishing or other purposes, students are active to participate and it is encouraging to see the improvement that students make throughout the teaching periods. We accompany the development of the unit with both inno- vative resource materials and experience to encourage the crea- tion of other units in this area elsewhere. Making Lecture More Visual and Engaging Students in the Classroom To improve the students’ engagement, we use the method proposed by John L. Falconer (2005) with some modification. 1) Visualizing important concepts To make the important concepts more visual, a list of impor- tant, difficult and easily confusing concepts are identified. Tho se error prone questions found in in-class quizzes are also added to this list. The visual representations of these concepts are presented in the form of color slides, PowerPoint animation presentations, and Java applet live demonstrations. The representations are uploaded on the unit teaching web site. The creation of these visual representations is also a good candidate for honors thesis or final year students’ project, such as animated representations of package-switching process (in Figure 4), and domain name lookup process. 2) Applying fun-engagement To engage students more in class, periodically during class, we use “fun engagement” technique. For instance, play relevant video/DVD about Internet history, classic hacker stories or le- gend of network gurus/company in class. After the video, “in- teraction engagement” technique is applied to give students a time frame to freely discuss their thoughts. The main objective is to involve the students more in the classroom and engage them more in their learning. It is proved that our class can be an exciting and enjoyable place for students learning and our teaching. Figure 3. Screenshot of in-c lass MCQ quiz. Figure 4. Video screenshot of packet switching animation. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 5  S. GAO ET AL. The only ethical issue might be the selection of video media. We try to select videotapes without sensitive and religious top- ics or examples. Usually it would be all right if sticking to these published materials for education purposes. Recording Lectures All the unit lectures are recorded with iLecture facilities in- tegrated in lecture theatres. Students who missed lectures and off campus students are benefiting from lecture recording (Fig- ure 5). Even though it is only audio record but videotaping, we re- view our lectures and discuss observations within teaching groups. We also observe other good teachers’ class and enrich our understanding of good teaching for further improvement. Conclusion By experimenting with the above discussed techniques and teaching improving approaches in practice, good and solid teaching outcome are achieved. It is encouraging that our teach- ing performance is improved step by step, reflected by students’ unit evaluation scores and positive feedbacks on our teaching at the end of each trimester. As an academic, we are suggested to think about the ways how our course and syllabus represent acts of scholarship (Shu l- man & Hutchings, 1994). We can use the ways how we conduct discipline based research toward our teaching and learning practice, seeing our teaching practices always need further in- vestigation and improvement. Scholarship of teaching is a very interesting topic that many academic have never thought of before. Most of the time, we focus on the “traditional” and “classic” discipline based re- search and almost neglect that we can also combine teaching and research together and treat pursuing better teac hing as sc ho l- arly activities. Teaching and research can be seen as mutually reinforcing. Usually the best scholars are the best teachers: the best teacher is a scholar who keeps updated with new content and methods Figure 5. Screenshot of iLecture recordings. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 6  S. GAO ET AL. of a field through continuing involvement in research and who communicates knowledge and enthusiasm for a subject to stu- dents. Plenty of examples have demonstrated that excellent teaching can also be pursued as scholarly activities. We hope our experience benefits other teaching scholars. REFERENCES Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personal- ity and development. P h i l a d e lp h i a : T h e P s ychology Press Falconer, J. L. (2005). A measure of college student course engagement. http://www.colorado.edu/ptsp/InitiativeEngaged/course_engage.htm Grenert, J. (2006). S c ho l a rl y r e f le c t io n a b o ut t ea c hing. http://sll.stanford.edu/projects/tomprof/newtomprof/postings.html Murray, H., Gillese, E. et al. (1996) Ethical Principles in University Teaching, STLHE/SAPES. Shulman, L., & Hutchings, P. (1994). Excerpt from Peer Review of Teaching Workshop sponsored by AAHE. Tytler, R., & Smith, P. (2006) “The scholoarhsip of teaching” study guide. Waurn P o n d s : D ea k i n U n i v er s i t y. Tytler, R., & Smith, P. (2006) “The scholoarhsip of teaching” CD. Waurn Ponds: Deakin Unive rsity. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 7 |