Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.7, 572-584 Published Online July 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.47083 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 572 Relations between Teachers’ Goal Orientations, Their Instructional Practices and Students’ Motivation Markus Dresel1, Michaela S. Fasching1, Gabriele Steuer1, Sebastian Nitsche2, Oliver Dickhäuser2 1University of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany 2University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany Email: markus.dresel@phil.uni-augsburg.de Received April 21st, 2013; revised May 25th, 2013; accepted June 24th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Markus Dresel et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Relations between teachers’ goal orientations, their instructional practices as expressed in perceived class- room goal structures and students’ goal orientations were analyzed, focusing also on potential moderators. Results of a questionnaire study with 46 Mathematics teachers and their 930 students supported the as- sumption that teachers’ goal orientations affect their instructional practices and students’ goal orientations. These effects were, in part, moderated by teacher beliefs (implicit theories, self-efficacy beliefs). Overall, the results provided strong support for the notion that the mechanisms underlying these effects are based on the functionality of certain instructional practices for the attainment of teachers’ goals. Keywords: Teacher Motivation; Goal Orientation; Instruction; Classrooms; Achievement Motivation Introduction Achievement goal theory is a powerful framework to des- cribe motivation in social achievement and learning contexts, and its consequences in terms of cognition and behavior (Ames, 1992; Dweck, 1986; Nicholls, 1984; for an overview see Elliot, 2005). This is not only true for the population of students, which researchers have extensively analyzed within this frame- work (for an overview see Maehr & Zusho, 2009). Recently, Butler (2007) applied achievement goal theory also to the population of teachers. In the meantime, considerable evidence has been collected to suggest that teachers’ goal orientations determine their experiences and own learning behaviors (e.g., Butler, 2007; Dickhäuser, Butler & Tönjes, 2007; Malmberg, 2008; Fasching, Dresel, Dickhäuser, & Nitsche, 2011; Nitsche, Dickhäuser, Fasching, & Dresel, 2011). Furthermore, it has also been assumed that teachers’ goal orientations influence their instructional practices as well as the motivation and learning behavior of their students. Although researchers provided pre- liminary evidence to support this assumption (Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retelsdorf, Butler, Streblow, & Schiefele, 2010), more research is needed to understand these associations. Therefore, we focus on the relationships between teachers’ goal orienta- tions, their instructional practices as expressed in students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures and the goal orienta- tions of their students. In doing so, we are focusing also on potential moderators of these relationships. Achievement Goal Theory Achievement goal orientations describe which goals indi- viduals preferably pursue in social achievement contexts (Ames, 1992; Dweck, 1986; Nicholls, 1984). The core assumption is that different achievement goal orientations create different motivational systems (e.g., processing self-related and task- related information, inferences concerning own competences, causal beliefs, standards) and therefore lead to different cogni- tive, affective and behavioral consequences (e.g., Elliott & Dweck, 1988). For the most part, research literature discrimi- nates among three different goal orientations (for an overview see Maehr & Zusho, 2009): learning goal orientation (aim to expand one’s own competences)1, performance approach goal orientation (aim to demonstrate own competences), and per- formance avoidance goal orientation (aim to avoid demonstrat- ing own competence deficits). Additionally, in the research tradition of Nicholls (1984), work avoidance goal orientation is sometimes considered, which refers to the aim to minimize effort in achievement settings2. Up to now, the primary focus of research has been on the goal orientations of students. In summarizing the patterns of findings regarding the consequences of student goal orienta- tions (e.g., involvement, persistence, strategy use, emotional experiences, performance), learning goal orientation, on the one hand, are considered to be adaptive, while performance avoid- ance and work avoidance goal orientations, on the other hand, have to be considered maladaptive. Performance approach goal 1To emphasize the focus on the expansion of own competences, we decided to use the term “learning goal orientation” instead of the terms “mastery goal orientation” or “task orientation” which are also used in the literature. 2In the past decade, theorists have also made a distinction between an ap- roach and an avoidance component within learning goals (Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Pintrich, 2000). Although research has provided some evidence that learning avoidance goals lead to different consequences than learning approach goals (for overviews see Huang, 2012; Moller & Elliot, 2006), learning avoidance goals are beyond the scope of the present paper, mainly because no evidence exists to support the validity of this facet o goal orientation for teachers.  M. DRESEL ET AL. orientation must be understood as ambivalent (for an overview see Maehr & Zusho, 2009). Teachers’ Goal Orientations Butler (2007) suggested that achievement goal theory is also suitable to describe teacher motivation and explain its conse- quences, founded on the notion that schools and classrooms not only constitute achievement contexts for students, but for teachers as well. This suggestion provoked a bundle of research in the field of teacher motivation, to the extent that a number of studies now exists to support this point of view (Butler, 2007; Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Dickhäuser et al., 2007; Malmberg, 2008; Fasching et al., 2011; Nitsche et al., 2011; Papaioannou & Christodoulidis, 2007; Retelsdorf et al., 2010; Tönjes, Dick- häuser, & Kröner, 2008). Research on the structure of teacher goal orientations indi- cates that the aforementioned four-dimensional conceptualiza- tion is also appropriate for the population of teachers (Butler, 2007; Dickhäuser et al., 2007; Nitsche et al., 2011): Teachers’ learning goal orientation refers to the aim to expand own pro- fessional competences. Teachers’ performance approach and avoidance goal orientations refer to the aim to demonstrate superior teaching competences or to avoid demonstrating infe- rior teaching competences, respectively. Finally, teachers’ work avoidance goal orientation refers to the aim to spend as little effort as possible in practicing the teaching profession. Existing evidence indicates that a teachers’ learning goal orientation is positively associated with adaptive attitudes towards help and professional development and a more extensive learning be- havior, while, in contrast, teachers’ performance and work avoidance goal orientations are positively associated with mal- adaptive attitudes and stress experiences (Butler, 2007; Dick- häuser et al., 2007; Retelsdorf et al., 2010; Nitsche et al., 2011; Tönjes et al., 2008). In an attempt to more specifically explain teacher goal orien- tation effects, Nitsche et al. (2011) suggested conceptualizing these four goal orientations as broad superordinate dimensions and then differentiating them, on a subordinated level. They proposed to differentiate learning goals with respect to the dif- ferent types of professional competences a teacher can aim to expand, based on the notion that teachers need vastly diverse competences in order to accomplish the multitude of tasks de- manded on them by their profession (Shulman, 1986). There- fore, Nitsche et al. differentiated between three subordinated types of learning goals: learning goals directed towards the expansion of pedagogical knowledge, learning goals directed towards the expansion of subject matter content knowledge and learning goals directed towards the expansion of pedagogical- content knowledge (Shulman, 1986). Moreover, Nitsche et al. proposed to differentiate performance goals with respect to the significant others to which they can be addressed. This is founded in the two components defining performance goals (Elliot, 1999), namely social comparison and appearance, and the presumption that to whom one wants to appear as compe- tent, or does not want to appear as incompetent, is crucial (this presumption was already confirmed for the population of stu- dents; Ziegler, Dresel, & Stoeger, 2008). So, Nitsche et al. dif- ferentiated both the performance approach and performance avoidance goal orientations of teachers with respect to four addressee groups, namely three inter-personal addressees (school principals, teacher colleagues, and students), and the acting teacher himself or herself as an intra-personal addressee (performance goals which are defined by social comparison, but do not imply that a positive appearance to others is a desir- able state or a negative appearance to others is an undesirable state; Ziegler et al., 2008). Nitsche et al. (2011) provided em- pirical evidence that this conceptualization, including super- ordinate and subordinate dimensions, is more suitable to de- scribe the goal orientations of teachers, and that different sub- dimensions of teachers’ learning and performance goal orienta- tions differentially predict attitudes towards help-seeking. Teacher Goal Orientations and Instructional Practices Butler (2007) also proposed considering teachers’ goal ori- entations as antecedents of their instructional practices and, particularly, of the goals they emphasize in the classroom for their students. However, up to now, to the best of our knowl- edge, only two studies have been published which examined associations between teachers’ goal orientations and their in- structional practices (Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retelsdorf et al., 2010). Nevertheless, this preliminary evidence supports the idea that teachers’ professional behaviour in the classroom depends on the goals they pursue for themselves. To adequately describe and explain goal orientation effects on instruction, a suitable conceptualization of teachers’ instruc- tional practices is at first essential. Here, we decided for the concept of classroom goal structures because it provides a broad conceptualization of teachers’ instructional practices which they realize in their classrooms. Moreover, within the framework of achievement goal theory it is the prevailing con- cept to describe differences between the instructional practices of different teachers (for an overview see Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006). Perceived classroom goal structures refer to student perceptions of the goal-related messages in the class- room and the extent to which the classroom environment allows for, or determines, the pursuit of learning and performance goals. Similar to personal goal orientations, classroom mastery goal structures and classroom performance goal structures are distinguished from one another, often complemented by a dif- ferentiation between approach and avoidance components within perceived classroom performance goal structures (Kap- lan, Gheen, & Midgley, 2002; Meece et al., 2006; Schwinger & Stiensmeier-Pelster, 2011)3. It is assumed that teachers create a mastery goal structure if they emphasize the importance of learning and mastery, for example by using meaningful and individually challenging tasks, by making students responsible for personal improvement and understanding the subject matter, or by recognizing student effort and improvement (Patrick, Anderman, Ryan, Edelin, & Midgley, 2001; Turner et al., 2002). In contrast, it is assumed that teachers create a performance approach and/or avoidance goal structure if they strongly focus on grades and the accuracy of answers, realize a normative grading practice, use ability grouping and competition in the classroom, or reward high-achieving students with privileges and/or refuse privileges to low-achieving students. Numerous studies revealed the robust finding that mastery goal structures lead to adaptive motivational and behavior outcomes and per- 3In contrast to personal goal orientations, whereby terms are used heteroge- neously (especially with regard to the terms “learning goals” and “mastery goals”), on the level of contextual goal structures the term “mastery goal structure” is uniformly used in the literature. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 573  M. DRESEL ET AL. formance goal structures lead to maladaptive outcomes on the part of the students. Most important in the present context are associations between classroom goal structures and students’ goal orientations, which, in turn, affect adaptive and maladap- tive learning patterns (for an overview see Meece et al., 2006). The aspects of teachers’ instructional practices, which were found in prior work to be dependent on teachers’ goal orienta- tions, relate to the concept of perceived classroom goal struc- tures. Butler and Shibaz (2008) focused on teacher support and inhibition of question-asking and help-seeking (as perceived by students), which can be understood as important instructional practices in setting up classroom goal structures (nonetheless only partially, as this narrow focus neglects several of the above described aspects of classroom goal structures). They found that a teachers’ learning goal orientation is positively associated with support for question-asking and help-seeking, and that a teachers’ performance avoidance goal orientation is negatively associated with this aspect (Butler and Shibaz iden- tified the opposite pattern for inhibition of question-asking and help-seeking). Moreover, they found positive associations be- tween teachers’ performance avoidance goals and students’ cheating. In two studies Retelsdorf et al. (2010) focused on associations between teachers’ goal orientations and their self- reported use of mastery and performance practices, thus focus- ing the full breadth of the concepts of classroom mastery and performance goal structures. They found, that teachers who strongly pursued learning goals reported a more extensive use of mastery practices, and that teachers who strongly pursued performance goals reported a more extensive use of perform- ance practices as well as a less extensive use of mastery prac- tices in their classrooms. Moreover, the results of Retelsdorf et al. (2010) indicated that teachers with a strong work avoidance goal orientation reported a more frequent use of performance practices. As an interim summary, what can be noted is that teacher goal orientations seem to have effects on instructional practices but one must also acknowledge that the existing studies suffer from a number of shortcomings and therefore more research is needed to qualify and understand these effects. Only one study focused on teachers’ instructional practices in their full breadth (Retelsdorf et al., 2010), nevertheless the exclusive use of teacher self-reports could have led to an overestimation of as- sociations, due to the several biases known for this type of measurement (e.g., shared method variance). Butler and Shibaz (2008), however, used student perceptions of teachers’ instruc- tional practices. Nevertheless, they focused only on a sub-as- pect of instructional practices. Student motivation in a narrower sense has not yet been analyzed in dependence on teachers’ goal orientations. Therefore, the perspective of the present pa- per on students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures and students’ goal orientations in dependence on teachers’ goal orientations is novel, and has the potential to complement ex- isting research literature. Until now, no evidence exists regard- ing teacher factors leading to certain student perceptions of classroom goal structures. Mechanisms Underlying the Associations between Teachers’ Goal Orientations and Instructional Practices Beyond limitations located primarily on an empirical level, the assumed associations between teachers’ goal orientations and their instructional practices are also challenged from a theoretical point of view. Prior work primarily substantiated a generalization hypothesis, which assumes corresponding asso- ciations: Teachers, who endorse learning goals for themselves, i.e., who aim to develop their own professional competences, are expected to apply a learning focus for their students too, i.e., are expected to emphasize learning goals and use mastery ori- ented instructional practices. On the other hand, it was expected that teachers who pursue performance goals for themselves, i.e., aim to demonstrate superior teaching competences or aim to avoid demonstrating inferior teaching competences, also exer- cise a performance focus in their classrooms, i.e., articulate performance goals and use performance oriented instructional practices. These correspondences can be justified with an as- sumed generalization of the motivational system created by teachers’ self-directed goals to teachers’ student-directed goals in terms of definitions of success, evaluation criteria, causal beliefs etc. Nevertheless, other, non-correspondent associations found in prior work can hardly be interpreted as an effect of the generalization of the motivational system (e.g., the effect of work avoidance goals on performance practices; Retelsdorf et al., 2010). Therefore, other mechanisms must exist. We propose con- sidering the functionality of instructional practices for goal attainment as the central and more general mechanism under- lying the effects of teachers’ goal orientations. This notion has its roots in general goal theory—here, a fundamental assump- tion is, that a certain goal increases the probability of a certain course of action if, and only if, the person appraises this course of action or its results as functional for the attainment of the goal at hand (e.g., Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Elliott & Dweck, 1988). We refer to this mechanism by using the term function- ality hypothesis. Under this functionality perspective, correspondences be- tween teachers’ goal orientations and their instructional prac- tices are not as straightforward as they might appear. Teachers’ learning goal orientation should enhance the realization of a mastery goal structure only to the extent that it allows for learning on the part of the teacher (and not on the part of the students), i.e., to the extent that it provides opportunities for the teacher to improve his or her professional competences. This may depend on the specific competence the teacher aims to expand (basically, the functionality of mastery practices is more self-evident for endeavors to expand pedagogical and peda- gogical-content knowledge than for endeavors to expand sub- ject matter content knowledge). On the other hand, teachers’ performance goals should enhance the realization of a per- formance goal structure only to the extent that it allows the teacher to demonstrate his or her teaching competences or con- ceal his or her competence deficits. This may additionally de- pend on to whom he or she wants to appear competent, or avoid appearing incompetent, i.e., the addressees of his or her per- formance goals (e.g., students, principal, the acting teacher himself or herself). Under a functionality perspective, non-correspondent asso- ciations can also be explained. Under the justifiable assumption that performance practices are less demanding for teachers (in terms of the required effort for their preparation and execution) than mastery practices, we predicted that performance practices are more functional, and mastery practices are less functional, for teachers’ work avoidance goals (rf. Retelsdorf et al., 2010). Moreover, under the condition that teachers believe that a good Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 574  M. DRESEL ET AL. teaching performance is manifested in maximized competence improvements for a maximum number of students, and that a good classroom instruction is characterized by a strong mastery focus, it can be predicted that mastery practices are functional for the attainment of teachers’ performance goals. However, under the condition that the teachers are convinced that a good teaching performance is manifested in emphasizing the per- formance aspect as well as the promotion of the best students, the correspondence between performance goals of teachers and performance-oriented instructional practices can be predicted. In the latter case, generalization and functionality hypotheses lead to identical predictions. Moderators Beyond the aforementioned assumptions regarding depend- encies on the specific competence facets on which learning goals can be directed and the specific addressees of perform- ance goals, we assumed that the functionality of specific in- structional practices for the attainment of teacher goals are dependent on a series of beliefs and standards. Among them are beliefs and standards regarding the definition of teaching suc- cess (as illustrated in the example above), regarding incentive policies in the scholastic context, regarding the educational room for manoeuvring a teacher has in developing his or her students’ abilities, or regarding one’s own teaching capabilities. Accordingly, teacher beliefs and school-specific standards can be conceptualized as potential moderators of the effects teach- ers’ goal orientations have on instructional practices. In the present work, it was not our intent to analyse these moderators in a comprehensive manner. Instead, we aimed to demonstrate that such moderation exists and focused on two potential mod- erators: implicit theories of teachers regarding the malleability of students’ abilities and teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Dweck and Leggett (1988) introduced the concept of implicit theories regarding the malleability of abilities to explain adap- tive vs. maladaptive patterns following failure. Their concept originally referred to actors’ own abilities (intelligence) and in their model, two opposing theories are contrasted: Whereas some people hold an incremental theory of their abilities ac- cording to which own abilities are malleable through own ef- forts, others see their abilities as a fixed entity which cannot be changed. As empirical findings generally indicate, different implicit theories have different motivational, affective, cogni- tive and behavioural consequences—with the general pattern, that an incremental theory can function as a protector against maladaptive reactions and an entity theory has to be considered a risk factor for them (for an overview see Dweck & Molden, 2005). Leroy, Bressoux, Sarrazin and Trouilloud (2007) con- veyed Dweck and Leggett’s (1988) concept on teachers’ im- plicit theories regarding the malleability of their students’ abili- ties and provided evidence that teachers are more autonomy- supportive when they believe that the abilities of their students are malleable. Accordingly, we predicted that teachers gener- ally use more mastery practices (autonomy-support can be conceptualized as one of them; rf. Ames, 1992) when they hold an incremental view of their students’ abilities. Although this has not been analysed in prior research, it is more central for the present paper that these teacher beliefs may also moderate the associations between teachers’ goal orientations and their instructional behaviours. For example, it could be predicted that the instructional practices teachers with a strong learning goal orientation select in order to expand their own professional competences depend on their assumptions regarding the malle- ability of student abilities. The concept of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs refers to teach- ers’ future-directed beliefs regarding their capabilities to suc- cessfully accomplish instructional tasks (Woolfolk-Hoy, Hoy, & Davis, 2009). Previous research indicated that teachers with higher self-efficacy beliefs demonstrate more effective instruc- tional behaviour (e.g., supporting learning instead of simply covering the curriculum, working longer with low-achieving students, selecting learning instead of performance goals; for an overview see Woolfolk-Hoy et al., 2009). Accordingly, for teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, a positive association with the use of mastery practices and a negative association with per- formance practices can be predicted. Previous research on these associations is scarce and limited to teacher self-reports (Wolt- ers & Daugherty, 2007). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs may also moderate associations between their goal orientations and their instructional practices. A potential moderation could occur because of the degree of risk-taking which is associated with different levels of teachers’ self-efficacy (Woolfolk-Hoy et al., 2009). It may be that self-efficacious teachers select instruct- tional practices which are characterized by a higher risk of fail- ure but are more promising in terms of attaining a specific goal, while less self-efficacious teachers may select instructional practices which do not pose a high risk of failure, but are less effective in terms of the attaining the goal at hand. Research Questions and Hypotheses The primary research question of the present paper focusses on the relations between teachers’ goal orientations, on the one hand, and students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures (as valid indicators of teachers’ instructional practices) and stu- dents’ goal orientations (as central aspects of their achievement motivation), on the other. Beyond unconditional relationships between broad factors of teacher goal orientations (learning, performance approach, performance avoidance, work avoid- ance) and instructional practices and student motivation, we focussed on effects of specific sub-facets of teachers’ goal ori- entations (with regard to the expansion of specific facets of professional competence and to specific addressees of per- formance goals) and potential moderators in terms of teacher beliefs (implicit theories, self-efficacy beliefs). Generally, we expected that the functionality of instructional practices for the attainment of teacher goals is the central mechanism underlying these associations, and that this mechanism is more suitable to explain them than the generalization of motivational systems implied by teachers’ goal orientations. Specifically, we aimed to test the following hypotheses: H1: Teachers’ goal orientations are associated with their in- structional practices (perceived classroom goal structures). To start with, we expected positive associations between corresponding dimensions (learning goals with classroom mas- tery goal structure, performance goals with classroom perfor- mance goal structures; Butler, 2007; Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retelsdorf et al., 2010) which are in line with both the func- tionality hypothesis and the generalization hypothesis. Addi- tionally, we expected associations between non-corresponding dimensions which are in line with the functionality hypothesis, but not with the generalization hypothesis: 1) We expected that learning goal orientations are negatively associated with class- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 575  M. DRESEL ET AL. room performance goal structures (because of their lower po- tential to expand teachers’ competences). 2) We expected that work avoidance goal orientations are negatively associated with classroom mastery goal structure and positively associated with classroom performance goal structures (because performance practices are less demanding for teachers than mastery practices; rf. Retelsdorf et al., 2010). 3) We expected that performance goal orientations are associated with classroom mastery goal structure, without making a prediction regarding the direction of this association (because the realization of a mastery focus in the classroom can be more or less functional for demonstrating superior teaching competences). Additionally, we expected to find differential relationships for different goal orientation di- mensions on the subordinated level. H2: Associations between goal orientations of teachers and their instructional practices are moderated by teachers’ beliefs (implicit theories regarding the malleability of students’ abili- ties, self-efficacy beliefs for teaching). From the functionality hypothesis (but not from the gener- alization hypothesis) we deduced that the associations between teachers’ goal orientations and their instructional practices de- pend on the belief systems the teachers hold. Therefore, we predicted that these associations are moderated by teacher be- liefs. However, due to an almost complete lack of knowledge on this aspect, we refused to make any predictions regarding the direction of moderation effects. H3: Teachers’ goal orientations are associated with their students’ motivation (students’ goal orientations). These asso- ciations are mediated through teachers’ instructional practices. Based on the extensive literature on the effects of classroom goal structures on students’ motivation and learning behaviour (see Meece et al., 2006, for an overview), we predicted that the expected effects of teachers’ goal orientations on perceived classroom goal structures would spread over to the motivation of their students. Our specific expectations were, therefore, analogous to those regarding Hypothesis 1. Method Procedure We used a data set from a larger cross-sectional study in the subject of Mathematics, which included students and teachers who answered standardized questionnaires during regular les- son periods. Participation was voluntary for both the teachers and the students. Data were collected by trained research assis- tants. Participants In that study we recruited a total of 56 fifth to eighth grade classrooms in eight public and six private secondary schools in urban, sub-urban and rural areas with different socio-cultural structures in southern Germany. In the present analyses, we included those 46 classrooms in which the teachers agreed to complete the respective questionnaire. Among the students in these classrooms 77.9% chose to participate in the study. The resulting sample consists of 46 Mathematics teachers (mean age of 45.3 years; SD = 9.20; 69% female) and 930 of their students (mean age of 13.1 years; SD = 1.01; 47% female). Measurements We used teacher as well as student measures to adequately assess teachers’ goal orientations and beliefs (teacher self-re- ports), teachers’ instructional practices (student perceptions of classroom goal structures), and students’ goal orientations (stu- dent self-reports). Teachers’ goal orientations. We measured teacher goal orientations with the questionnaire developed by Nitsche et al. (2011). It contains a uniform item stem (“In my vocation, I aspire ···”) and subscales for four broad goal orientation factors, namely learning goal orientation (9 items), performance ap- proach goal orientation (12 items), performance avoidance goal orientation (12 items) and work avoidance goal orientation (3 items). The learning goal orientation scale consists of, on a subordinate level, three 3-item sub-factors, which reflect the goals to broaden the three main types of professional teacher competences proposed by Shulman (1986): pedagogical knowl- edge (sample item: “··· to improve my pedagogical knowledge and competence”), subject matter content knowledge (“··· to really comprehend the contents of my subject”), and pedagogi- cal-content knowledge (“··· to really comprehend the process of knowledge transfer in my subject”). The scales for the per- formance approach and performance avoidance goal orienta- tions each consist of four 3-item sub-factors, which reflect relevant addressees of teachers’ performance goals: colleagues (“··· my colleagues to realize that I teach better than other teachers”, “··· to conceal from my colleagues when I do some- thing less satisfying than other teachers”), school principal (“··· my principal to realize that I teach better than other teachers”, “··· my principal not to believe I would master my job less suf- ficient than other teachers”), students (“··· my students to real- ize that I teach better than other teachers”, “··· to conceal from my students when I do something less satisfying than other teachers“) and the acting teacher him/herself (“··· to prove my- self that I teach better than other teachers”, “··· to not have to admit to myself when I do something less satisfying than other teachers“). The scale assessing teachers’ work avoidance goal orientation (“··· that the work is easy”) does not consist of sub-factors. All items were rated on 5-point Likert type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Inter- nal consistencies of the four broad goal orientations were in the range of Cronbach’s α = .78 - .91; those of the 11 sub-scales in the range of α = .61 - .94. Teachers’ implicit theories regarding students’ abilities. Using three items of Dweck, Chiu and Hong (1995), we as- sessed the extent to which teachers implicitly believe that their students can expand their abilities in the subject of Mathematics. The items, which originally focused on one’s own intelligence, were adapted so that they focused on the Mathematics abilities of students from the perspective of the teacher (“My students can learn new things in Mathematics, but they can’t really change their basic abilities for Mathematics”). They were rated using 6-point Likert type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly dis- agree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scale was recoded, so that a higher value represents a more incremental view. α = .87. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching. Five items from the scale developed by Schwarzer and Hallum (2008) assessed teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding demands in the context of teaching (“When I try really hard, I am able to reach even the most difficult students”). Teachers gave their responses on 4-point Likert type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). α = .65. Students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures. We measured students’ perceptions of classroom mastery, perfor- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 576  M. DRESEL ET AL. mance approach and performance avoidance goal structures with the respective scales of the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS; Midgley et al., 2000), which we adapted to the subject of Mathematics and extended in order to enhance reli- ability. The scales measuring mastery goal structure (“In our Math class, really understanding the material is the main goal”), performance approach goal structure (“In our Math class, get- ting right answers is very important”) and performance avoid- ance goal structure (“In our Math class, it’s important not to do worse than other students”) consisted of 7, 6 and 8 items, re- spectively, which were rated on 5-point Likert type scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). α = .76 - .84. Students’ goal orientations. To assess students’ goal orien- tations, we used an instrument well-established in Germany (Spinath, Stiensmeier-Pelster, Schöne, & Dickhäuser, 2002) which we adapted to the subject of Mathematics (item stem: “In Maths class I usually ···”). Learning (“··· want to learn as much as possible”), performance approach (“··· want to show that I am good at something”), performance avoidance (“··· don’t want the other students to think I am stupid”) and work avoid- ance (“··· want to keep my workload small”) goal orientations were measured using 8, 7, 8 and 8 items, respectively. Students rated them on 5-point Likert type scales, ranging from 1 (abso- lutely false) to 5 (absolutely true). α = .81 - .85. Missing Data and Analyses We carried out the study on which the present analyses are based in two cohorts. In the first cohort (17 classrooms), a multi-matrix design was applied on the student level for eco- nomic reasons (Munger & Loyd, 1988). Here, we collected students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures from (ran- domly selected) half of the students within each classroom, and students’ goal orientations were assessed among the other half of the students. Such structurally incomplete designs reveal values similar to those from complete datasets (Smits & Vorst, 2007). In the second cohort (39 classrooms), however, com- plete assessments were made for all students. Moreover, we assessed teachers’ goal orientations and beliefs in full, for all teachers in both cohorts. We imputed missing values due to the partially incomplete design and item non-response (less than 10% for all teacher and student items) using the expecta- tion-maximization algorithm (see Peugh & Enders, 2004). We conducted two-level modelling with HLM 6 (Rauden- bush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2004) using restricted maximum like- lihood estimation (students nested in teachers; intercept-as-out- come-models). We z-standardized all variables prior to analyses —consequently, the coefficients of fixed effects can be inter- preted similarly to standardized regression coefficients. Results We observed significant and moderate variation between teachers for all perceptions of classroom goal structures (error- corrected intraclass correlations ICC* = .12 - .16; p < .001). Moreover, we observed significant and small to moderate variation between teachers for students’ learning, performance approach and performance avoidance goal orientations (ICC* = .05 - .15; p < .001), but not for students’ work avoidance goal orientation (ICC* = .02; p > .05). Relations between Teachers’ Goal Orientations and Students’ Perceptions of Classroom Goal Structures (Hypothesis 1) In the first step, we analysed the effects of the four broad factors of teachers’ goal orientations on their students’ per- ceptions of the classroom goal structures (Table 1). We deleted predictors with relationships in the direction opposite to those of the respective bivariate correlations and non-significant pre- dictors stepwise from the models in order to avoid problems stemming from multicollinearity. As predicted, classroom per- formance goal structures (approach and avoidance) were posi- tively predicted by teachers’ performance avoidance goal ori- entations (performance avoidance goal structure: p = .09) and negatively predicted by teachers’ learning goal orientations. Moreover, in accordance with our expectations, teachers’ work avoidance goal orientations were a negative predictor of class- room mastery goal structures. Additionally, we observed a positive effect of teachers’ performance approach goal orienta- tion on classroom mastery goal structure. However, some ex- pected effects could not be safeguarded; particularly worth mentioning is that no unconditional effect of teachers’ learning goals on classroom mastery goal structures could be proven. In the second step, we replaced the significant predictors in the models with the respective sub-factors (i.e., with the three competence-specific sub-factors of learning goals and the four addressee-specific sub-factors of performance goals, respec- tively) to gain information on which specific aspects of teach- ers’ goal orientations are responsible for certain classroom goal structures. This in-depth analysis revealed that teachers’ per- formance goals which are addressed to themselves (i.e., the goal to demonstrate to oneself, that one teaches better than other teachers) are exclusively responsible for the positive ef- fect of teachers’ performance approach goals on classroom mastery goal structures (β = 0.09; SE = 0.05; p = .05), while teachers’ performance goals which are directed towards exter- nal addressees had no effect. With respect to classroom per- formance goal structures, we observed a similar pattern for both performance approach and performance avoidance goal struc- tures: Responsible for the positive effects of teachers’ perfor- Table 1. Two-level prediction of students’ perceptions of classroom goal struc- tures from teachers’ goal orientations. Students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures Predictor: Teachers’ Goal Orientations (Level 2) Mastery goal structure Performance approach goal structure Performance avoidance goal structure Learning goals - –0.10* (0.05) –0.11* (0.05) Performance approach goals 0.11* (0.04) - - Performance avoidance goals - 0.11* (0.06) 0.09+ (0.06) Work avoidance goals –0.11* (0.05) - - 2 Between R .14 .10 .08 Note: All variables were z-standardized prior to analyses. Predictors were grand- mean centered. Presented are regression coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses). *p < .05. +p < .10. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 577  M. DRESEL ET AL. mance avoidance goal orientations were performance avoidance goals which are addressed to the principal (Performance ap- proach goal structure: β = 0.16; SE = 0.07; p < .05. Perform- ance avoidance goal structure: β = 0.11; SE = 0.07; p = .06) and to their students (Performance approach goal structure: β = 0.17; SE = 0.06; p < .01. Performance avoidance goal structure: β = 0.21; SE = 0.06; p < .01), but not performance avoidance goals which address their colleagues or themselves. Moreover, the analyses revealed that teachers’ learning goals directed towards the expansion of their pedagogical knowledge (Performance approach goal structure: β = –0.12; SE = 0.07; p < .05. Per- formance avoidance goal structure: β = –0.14; SE = 0.08; p < .05) and their pedagogical-content knowledge (Performance approach goal structure: β = –0.12; SE = 0.06; p < .05. Per- formance avoidance goal structure: β = –0.11; SE = 0.07; p < .05) were significant negative predictors of perceived class- room performance goal structures, while teachers’ learning goals directed towards the expansion of their content knowl- edge were not. Moderators of the Relations between Te a chers’ Goa l Orientations and Students’ Perceptions of Classroom Goal Structures (Hypothesis 2) We calculated product terms by multiplying the z-scores of each of the four broad goal orientation factors with the z-scores of each of the two potential moderators (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Multilevel models were extended on level 2 with those product terms which proved to be significant in a series of preliminary analyses (additionally with the corre- sponding unconditional variables). With respect to classroom mastery goal structure, the analy- sis revealed a significant moderator effect of teachers’ learning goals and their implicit theories (β = 0.09; SE = 0.04; p < .05), which is illustrated in Figure 1. Teachers with an incremental view of their students’ abilities realized a slightly stronger classroom mastery goal structure when they pursued learning goals to a stronger extent, while teachers with an entity view demonstrated a weaker mastery goal structure in their class- rooms with increasing learning goals. Additionally, a signifi- cant positive main effect of teachers’ implicit theories on per- ceived classroom mastery goal structure was observed (β = 0.11; SE = 0.06; p < .05). With these effects, the explained between- teacher variance of perceived classroom mastery goal structure increased from R2 = .14 to R2 = .23. For classroom performance approach and avoidance goal structures, we identified interaction effects between teachers’ work avoidance goals and their implicit theories (Performance approach goal structure: β = –0.13; SE = 0.05; p < .05. Per- formance avoidance goal structure: β = –0.15; SE = 0.05; p < .01). While teachers’ work avoidance goals had no, or even slightly negative, effects on classroom performance goal struc- tures when they viewed their students’ abilities as malleable, stronger classroom performance goal structures were perceived with increasing work avoidance goals when teachers had an entity view (Figure 2). Moreover, we observed an interaction effect between teachers’ performance avoidance goals and their self-efficacy beliefs for both classroom performance approach and avoidance goal structures (Performance approach goal structure: β = –0.18; SE = 0.07; p < .05. Performance avoidance goal structure: β = –0.21; SE = 0.07; p < .01). Teachers with strong self-efficacy beliefs tended to realize weaker classroom Figure 1. Moderation of the association between teachers’ learning goal orientations and students’ perceptions of classroom mastery goal structure by teachers’ implicit theories regarding the mal- leability of students’ abilities (predicted values). performance goal structures when they increasingly took aim to avoid demonstrating inferior teaching performances (Figure 3). In contrast, teachers with weak self-efficacy beliefs realized stronger classroom performance goal structures with increasing performance avoidance goals. Independent of these moderator effects, no significant main effects of teachers’ implicit theories and self-efficacy beliefs were evident (|β| < .07; p > .10). Ex- tending the multilevel models with these moderator effects increased the proportions of explained between-teacher vari- ance from R2 = .10 to R2 = .23 and from R2 = .08 to R2 = .30 for perceived classroom performance approach and avoidance goal structure, respectively. Relations between Teachers’ and Studen t s’ Goal Orientations (Hypothesis 3) We examined the effects of teachers’ goal orientations on students’ goal orientations with two modelling steps (Table 2)4. First, we identified the factors of teachers’ goal orientations that are relevant for student motivation as we did for classroom goal structures (Model 1). Second, we inserted students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures into the models on both the aggre- gated teacher level and the level of the individual student (Model 2). We did this in order to examine whether any effects of teachers’ goals on students’ goals were mediated by the in- structional practices of the teachers in terms of the goal struc- 4We excluded students’ work avoidance goal orientations from this analysis since no significant between-teacher variation was observed for them (as eported above). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 578  M. DRESEL ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 579 Figure 2. Moderation of the associations between teachers’ work avoidance goal orientations and students’ perceptions of classroom perform- ance approach and avoidance goal structures by teachers’ implicit theories regarding the malleability of students’ abilities (predicted values). Figure 3. Moderation of the associations between teachers’ performance avoidance goal orientations and students’ perceptions of classroom performance approach and avoidance goal structures by teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching (predicted values).  M. DRESEL ET AL. Table 2. Two-level prediction of students’ goal orientations from teachers’ goal orientations and perceived classroom goal structures. Students’ goal orientations Learning goals Performance approach goals Performance avoidance goals Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2 Teachers’ goal orientations (Level 2) Learning goals - - –0.11* (0.04) –0.03 (0.03) –0.07+ (0.05) –0.01 (0.02) Performance approach goals 0.20* (0.04) 0.10* (0.03) - - - - Performance avoidance goals - - 0.09* (0.04) 0.02 (0.03) - - Work avoidance goals –0.10* (0.06) –0.01 (0.03) - - - - Students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures Between teacher level (Level 2) Mastery goal structure 0.32* (0.03) 0.10* (0.03) –0.00 (0.02) Performance approach goal structure 0.07 (0.08) 0.14* (0.06) –0.01 (0.07) Performance avoidance goal structure 0.04 (0.08) 0.07 (0.06) 0.28* (0.08) Within teacher level (Level 1) Mastery goal structure 0.45* (0.04) 0.16* (0.04) –0.10* (0.03) Performance approach goal structure 0.17* (0.04) 0.47* (0.05) 0.19* (0.07) Performance avoidance goal structure –0.11* (0.05) 0.08+ (0.05) 0.47* (0.06) 2 Between R 2 .29 .96 .32 .86 .03 .99 Within R .00 .23 .00 .32 .00 .35 Note: All variables were z-standardized prior to analyses. Predictors on level 2 were grand-mean centered and predictors on level 1 were group-mean centered. Presented are regression coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses). *p < .05. +p < .10. tures they realized in their classrooms. Estimating Model 1 revealed results which were, overall, quite similar to those for classroom goal structures. Students’ learning goals were positively predicted by teachers’ perfor- mance approach goals and negatively predicted by teachers’ work avoidance goals. Students’ performance approach goals were positively predicted by teachers’ performance avoidance goals and negatively predicted by teachers’ learning goals. However, for students’ performance avoidance goals only one effect on the 10%-level of significance was observed: They were negatively predicted by teachers’ learning goals (p = .08). Inserting students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures led to an almost total explanation of between-teacher differ- ences in students’ achievement goals. The pattern of associa- tions on the between-teacher and within-teacher levels was, generally speaking, in accordance with findings of prior re- search (Meece et al., 2006). Two-level mediation testing (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001) confirmed that the effects of teachers’ performance approach and work avoidance goals on students’ learning goals were (partly) mediated by classroom mastery goal structure (|z| > 2.08; p < .05). Moreover, mediation testing revealed, at the 10%-level of significance, that the effects of learning and performance avoidance goals of teachers on per- formance approach goals of students were mediated by class- room performance approach goal structure (|z| > 1.39; p < .08). Finally, the negative association between teachers’ learning goals and students’ performance avoidance goals was mediated by classroom performance avoidance goal structure (z = 1.74; p < .05). Discussion Overall, the present results support the presumption that teachers’ instructional practices depend on their goal orienta- tions (Hypothesis 1). We were able to resolve important limita- tions of the few prior studies on this topic (Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retelsdorf et al., 2010) through operationalizing teach- ers’ instructional practices by using students’ perceptions of the broadly conceptualized and theoretically well-grounded dimen- sions of classroom goal structures (Meece et al., 2006); there- fore, a unique contribution to the research literature on teacher motivation could be provided. As expected, and in line with prior results based on teacher self-reports to measure instructional practice (Retelsdorf et al., 2010), teachers with a strong performance avoidance goal ori- entation realized strong classroom performance approach and avoidance goal structures. This correspondence may be an ef- fect of the generalization of the motivational system which is associated with teachers’ performance goals to standards in evaluating student achievement, the processing of student-re- lated information and inferences regarding students’ abilities. In addition, these correspondent associations are also in line with Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 580  M. DRESEL ET AL. the functionality hypothesis: The use of performance-oriented instructional practices can be an instrument for teachers who pursue the goal of avoiding having others recognize own poor teaching competences, for example, when they punish and thwart student errors in order to avoid deeper topic discussion and prohibit inferences regarding low teaching quality. An in- depth analysis of the addressee-specific performance avoidance goals further enlightened the positive effects of teachers’ per- formance avoidance goals on perceived classroom performance goal structures. We observed consistent effects for performance avoidance goals, with which teachers aim to avoid appearing incompetent towards their students and the school principal. This pattern of results points to a possible combination of dif- ferent mechanisms. While the effect of performance avoidance goals that teachers address to their students may be a result of both a generalization of motivational systems and appraisals of the functionality for goal attainment, the effect of performance avoidance goals teachers address to their principals can hardly be interpreted in terms of generalization. It can be better inter- preted in terms of the functionality of good or, at least, not bad student performances which serves the goal to not appearing incompetent to the principal. In contrast to prior results, we found, no support for the as- sumption that teachers’ learning goal orientation is, in general, positively associated with the corresponding classroom mastery goal structure (instead, moderation was observed in this context —we will discuss this later). To explain this contradiction be- tween previous findings and the present results, one can suspect that a common method bias (Retelsdorf et al., 2010) or focusing only a specific aspect of mastery practices (Butler & Shibaz, 2008) in prior research, may have led to an overestimation of the association. In accordance with our predictions we observed a series of associations between non-correspondent goal orientations and classroom goal structure components which were only partly detected in prior research. As expected, teachers’ learning goal orientations negatively predicted students’ perceptions of both a classroom performance approach and a classroom performance avoidance goal structure. These effects, which are similar to the effects found by Butler and Shibaz (2008) for perceived teacher inhibition of question-asking and help-seeking, can be inter- preted as a result of the small potential of performance-oriented practices to provide teachers with information regarding the effectiveness of their own instructional practices and, therefore, to expand teachers’ competences. This functionality interpreta- tion is strengthened by the result that the effect at hand was only associated with learning goals directed towards the expan- sion of pedagogical and pedagogical-content knowledge, but not with learning goals directed towards the expansion of con- tent knowledge (Shulman, 1986), since it can be assumed that a low functionality of performance-oriented practices is given, especially for the two former competence facets. Moreover we observed, as expected, a negative effect of teachers’ work avoidance goals on classroom mastery goal structure, which can be interpreted against the understanding that mastery-ori- ented practices are usually demanding in terms of the effort required for their preparation and execution (rf. Retelsdorf et al., 2010). Finally, we found evidence that teachers’ performance approach goals have a positive effect on classroom mastery goal structures. In prior research the performance approach goals of teachers were often unrelated to their experiences and behaviours (e.g., Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retelsdorf et al., 2010). Under a functionality perspective we predicted such a relation- ship, nevertheless declining to make a prediction regarding its direction. The positive effect identified is plausible when one takes into account that teachers frequently define teaching suc- cess in terms of realizing strong instructional contexts to achieve competence development and mastery for all students. Under this definition of teaching success, the degree to which teachers realize a classroom mastery goal structure can actually be interpreted as an indicator of teacher performance. Therefore, realizing a classroom mastery goal structure should be seen as functional for the attainment of performance goals. Under this view, the positive effect of teachers’ performance approach goals (which contradicts, in part, the results of Retelsdorf et al., 2010) is in accordance with the positive achievement effects of performance approach goals reported in the literature for stu- dents (Huang, 2012). In-depth analyses revealed that this effect is exclusively associated with teachers’ self-addressed per- formance approach goals, i.e., goals with which they aim to excel in comparison to other teachers, but do not specifically aim to appear competent towards significant others. This is in accordance with findings of Ziegler et al. (2008) for students, indicating that self-addressed performance goals are associated with actual motivation and achievement more positively than others-addressed performance goals. Overall, predicting perceived classroom goal structures from teachers’ goal orientations without accounting for potential moderators led to relatively small proportions of explained criterion variance. Nevertheless, these proportions were in the range found in prior research (Butler & Shibaz, 2008; Retels- dorf et al., 2010). As predicted only from a functionality perspective, we ob- served a series of moderator effects associated with aspects of the belief systems of teachers (Hypothesis 2). The observation of a small positive association between teachers’ learning goals and a perceived mastery goal structure when teachers hold an incremental theory regarding student abilities, and a strong negative association when teachers hold an entity theory, could be interpreted in terms of the varying functionality of mas- tery-oriented instructional practices for the attainment of teach- ers’ learning goals associated with different implicit theories. If they hold an incremental view, teachers should see teaching competences regarding the development of all students’ abili- ties as most relevant. On the contrary, if they hold an entity view, they should see mastery-oriented strategies as less appro- priate. Moreover, the predicted positive effects of work avoid- ance goals on classroom performance goal structures were ob- served only for teachers with an entity view of their students’ abilities. Obviously, the instrumentality of performance-ori- ented practices for the aim of spending as little effort as possi- ble in practicing the teacher profession is perceived and/or ac- cepted to a lesser degree by teachers when they view the abili- ties of their students as more malleable and, therefore, may perceive a stronger responsibility for their students’ compe- tence development. Finally, interaction effects between teach- ers’ performance avoidance goals and their self-efficacy beliefs were observed. The already discussed positive main effects of performance avoidance goals on perceived classroom perform- ance goal structures were especially strong in the case of weak self-efficacy beliefs, and were absent in the case of strong self-efficacy beliefs. We interpret these moderator effects as an effect of the functionality of performance-oriented practices that varies with varying self-efficacy beliefs, because different Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 581  M. DRESEL ET AL. levels of self-efficacy are associated with different degrees of risk-taking. More specifically, we assume that teachers with both perceptions of weak teaching competences, as well as a strong focus on avoiding the demonstration of these weak competences, tend to see performance-oriented instructional practices as a relatively risk-free way to protect themselves against inferences by others regarding their own weak compe- tences. Accounting for moderator effects resulted in a remarkable increase in the proportions of explained between-teacher vari- ance in students’ perceptions of classroom goal structures. This underpins our assumption that effects of teacher goal orienta- tions are frequently dependent on the beliefs of teachers and salient standards for teachers, and challenge theorists to con- cisely model the conditions under which certain goal orienta- tions lead to certain instructional practices which lead, in turn, to certain qualities of student motivation and learning. It has, nevertheless, to be mentioned that the present research focused on only two potential moderators and other moderators may exist (e.g., definition of teaching success and incentive policies in the organizational/school context of teachers). As a side result we could demonstrate, for the first time, that teachers use more mastery oriented practices when they hold an incremental view of student abilities (see Leroy et al., 2008). With regard to the associations between teacher goals and student motivation we showed, in line with our expectations, that the impact teachers’ goal orientations have on students’ goal orientations is similar to the impact they have on class- room goal structures. This impact was, to the largest extent, mediated through instructional practices in terms of the goal structures the teachers realize in their classrooms (Hypothesis 3). The present work demonstrated, for the first time, the effects of teacher motivation on student motivation within the theo- retical framework of achievement goal theory in a narrow sense. The direct (i.e., through classroom goal structures only partially mediated) effect of teachers’ performance approach goals on students’ learning goals may be a result of associations with the use of certain specific mastery-oriented instructional practices which are not examined in, or associated with, the concept and measure of perceived classroom goal structure used in the pre- sent work (Midgley et al., 2000). In general, we appraise the detailed analyses of associations between teacher goal orienta- tions, specific dimensions of their instructional practices in relation to their realization of certain classroom goal structures (understood as a macroscopic or crystallized indicator of in- structional practice), and student motivation as an important task of future research. Overall, the present results strongly support the functionality hypothesis substantiated in this paper, i.e., the theoretical no- tion that effects of teachers’ goal orientations on their instruct- tional behaviour should be understood in terms of the function- ality or instrumentality of the specific behaviour for the attain- ment of their personal goals. This is supported by a series of significant associations between non-correspondent goal orien- tations and classroom goal structure components, and a series of significant moderator effects according to which the strength and the directions of associations between teachers’ goal orien- tations and classroom goal structures are dependent on the be- lief systems teachers hold. Both non-correspondent effects and moderator effects are not in accordance with the generalization hypothesis. As we argued, the functionality mechanism can be understood as being more general than the mechanism of gen- eralizing the motivational system implied by certain goal ori- entations. The correspondent associations predicted from an assumed generalization of motivational systems (i.e., positive associations of learning and performance goals with classroom mastery and performance goal structures, respectively) can also be explained through the functionality of the respective instruc- tional practices for attaining the corresponding personal goal. Limitations and Prospects for Future Research Although significant limitations over prior studies could be resolved in the present study, namely the use of teacher self- reports, the narrow focus on specific aspects of instructional practice, the neglect of potential moderator effects, as well as specific facets of professional competences to which learning goals could be directed and specific addressees to which per- formance goals of teachers could be directed, some limitations do remain. Here, the relatively small sample on the teacher level has to be mentioned. This could have led to an oversight of (small) effects of teacher goal orientations. However, this does not place into question the identified effects. Their gener- alizability (at least for the population of mathematics teachers in secondary schools) is safeguarded through a relatively di- verse sample of teachers and students from different contexts. Nevertheless, future research should be conducted in different school subjects and grade levels using larger samples on the teacher level. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the present study has to be mentioned—in that causal inferences in a narrow sense are not justified. Indeed, the causal direction opposed to the causal direction that we theoretically assumed may also be (additionally) plausible, e.g., that teachers adapt their goal orientations to student characteristics. Disentangling potential recursive associations is a relevant and challenging task for future research. Nevertheless, for two reasons, the theoretically assumed causal direction interpreting the associa- tions as effects of teachers’ goal orientations is more likely: Firstly, because teacher goal orientations were measured gener- ally without reference to the specific Mathematics classroom in which students’ perceptions of instructional practices and goal orientations were assessed. Secondly, because perceived class- room goal structures would not be expected to function as (full) mediators in the case of bottom-up effects of student character- istics on teachers’ goal orientations. Conclusion Despite these limitations, it could be concluded that the as- sumption that teachers’ goal orientations affect their instruc- tional practices also holds true when conceptualizing instruc- tional practices in a broad and theory-driven manner (classroom goal structures) and when measuring them using student per- ceptions, which are more advisable in order to rule out potential biases of teacher self-reports. The present results provide evi- dence regarding the important, but widely unaddressed, ques- tion regarding the determinants of perceived classroom goal structures, which prevailed within the framework of achieve- ment goal theory to describe differences between classrooms and proved to have important consequences in terms of student motivation, learning behaviour and achievement (Meece et al., 2006). It could be concluded that the effects of teachers’ goal orientations on their instructional practices also spread over in effects on student motivation (i.e., their goal orientations). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 582  M. DRESEL ET AL. Moreover, it could be concluded that the effects of teachers’ goal orientations on their instructional practices are, in part, moderated by teacher beliefs. With respect to the underlying mechanisms it could be concluded that the effects of goal ori- entations of teachers are based, to a vast degree, on the func- tionality of certain instructional practices for the attainment of teachers’ goals, whereas the assumption that a generalization of the motivational systems that goal orientations imply is respon- sible, at best, for a small proportion of the effects of teachers’ goal orientations on their instructional practices and their stu- dents’ motivation. Acknowledgements The study presented in this paper was funded by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research to Markus Dresel (01 HJ 0902) and Oliver Dickhäuser (01 HJ 0901). REFERENCES Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psycholo gy, 84, 261-271. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261 Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 338-375. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338 Butler, R. (2007). Teachers’ achievement goal orientation and associa- tion with teachers’ help-seeking: Examination of a novel approach to teacher motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 241-252. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.241 Butler, R., & Shibaz, L. (2008). Achievement goals for teaching as predictors of students’ perceptions of instructional practices and stu- dents’ help seeking and cheating. Learning and Instruction, 18, 453- 467. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.004 Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied mul- tiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Dickhäuser, O., Butler, R., & Tönjes, B. (2007). That just shows I can’t do it: Goal orientation and attitudes concerning help among pre- service teachers. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 39, 120-126. doi:10.1026/0049-8637.39.3.120 Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040 Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256 Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6, 267-285. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1 Dweck, C. S., & Molden, D. C. (2005). Self-theories: Their impact on competence motivation and acquisition. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 122- 140). New York: Guilford Press. Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and avoidance motivation and achieve- ment goals. Educational Psychologist, 34, 169-189. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3403_3 Elliot, A. J. (2005). A conceptual history of the achievement goal con- struct. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 52-72). New York: Guildford. Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 501- 519. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.501 Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 5-12. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5 Fasching, M. S., Dresel, M., Dickhäuser, O., & Nitsche, S. (2011). Goal orientations of teacher trainees: Longitudinal analysis of magnitude, change and relevance. Journal of Educational Research Online, 2, 9- 33. Huang, C. (2012). Discriminant and criterion-related validity of achievement goals in predicting academic achievement: A meta- analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104, 48-73. doi:10.1037/a0026223 Kaplan, A., Gheen, M., & Midgley, C. (2002). Classroom goal structure and student disruptive behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 191-211. doi:10.1348/000709902158847 Kaplan, A., Middleton, M. J., Urdan, T., & Midgley, C. (2002). Achievement goals and goal structures. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goals structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 21-55). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Krull, J. L., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of indi- vidual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36, 249-277. doi:10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06 Leroy, N., Bressoux, P., Sarrazin, P., & Trouilloud, D. (2007). Impact of teachers’ implicit theories and perceived pressures on the estab- lishment of an autonomy supportive climate. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22, 529-545. doi:10.1007/BF03173470 Maehr, M. L., & Zusho, A. (2009). Achievement goal theory: The past, present, and future. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Hand- book of motivation at school (pp. 77-104). New York: Routledge. Malmberg, L.-E. (2008). Student teachers’ achievement goal orienta- tions during teacher studies: Antecedents, correlates and outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 18, 438-452. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.003 Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. An- nual Review of Psychology, 57, 487-503. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070258 Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L. Z., Anderman, E. M., Anderman, L. H., Freeman, K. E., Urdan, T. et al. (2000). Manual for the Pat- terns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. Moller, A. C., & Elliot, A. J. (2006). The 2 × 2 achievement goal framework: An overview of empirical research. In A. Mittel (Ed.), Focus on educational psychology (pp. 307-326). New York: Nova Science. Munger, G. F., & Loyd, B. H. (1988). The use of multiple matrix sam- pling for survey research. The Journal of Experimental Education, 56, 187-191. Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice and performance. Psychological Review, 941, 328-346. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328 Nitsche, S., Dickhäuser, O., Fasching, M. S., & Dresel, M. (2011). Rethinking teachers’ goal orientations: Conceptual and method- ological enhancements. Learning and Instruction, 21, 574-586. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.12.001 Papaioannou, A., & Christodoulidis, T. (2007). A measure of teachers’ achievement goals. Educationa l Psychology, 27, 349-361. doi:10.1080/01443410601104148 Patrick, H., Anderman, L. H., Ryan, A. M., Edelin, K. C., & Midgley, C. (2001). Teachers’ communication of goal orientations in four fifth-grade classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 102, 35-58. doi:10.1086/499692 Peugh, J. L., & Enders, C. K. (2004). Missing data in educational re- search. Review of Educational Research, 74, 525-556. doi:10.3102/00346543074004525 Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 544-555. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.544 Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., & Congdon, R. (2004). HLM 6 for Windows (Computer software). Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International. Retelsdorf, J., Butler, R., Streblow, L., & Schiefele, U. (2010). Teach- ers’ goal orientations for teaching: Associations with instructional Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 583  M. DRESEL ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 584 practices, interest in teaching, and burnout. Learning and Instruction, 20, 34-43. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.01.001 Schwarzer, R., & Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 152-171. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x Schwinger, M., & Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2011). Performance-approach and performance-avoidance classroom goals and the adoption of personal achievement goals. British Journal of Educational Psy- chology, 81, 680-699. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02012.x Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4-14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004 Smits, N., & Vorst, H. C. M. (2007). Reducing the length of question- naires through structurally incomplete designs: An illustration. Learning and Individual Differences, 17, 25-34. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2006.12.005 Spinath, B., Stiensmeier-Pelster, J., Schöne, C., & Dickhäuser, O. (2002). Scales to assess learning and achievement motivation. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. Tönjes, B., Dickhäuser, O., & Kröner, S. (2008). Goal orientation and perceived lack of achievement in teachers. Zeitschrift für Päda- gogische Psychologie, 22, 151-160. doi:10.1024/1010-0652.22.2.151 Turner, J. C., Midgley, C., Meyer, D. K., Gheen, M., Anderman, E. M., Kang, Y., & Patrick, H. (2002). The classroom environment and stu- dents’ reports of avoidance strategies in mathematics: A multi- method study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 88-106. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.94.1.88 Wolters, C. A., & Daugherty, S. G. (2007). Goal structures and teach- ers’ sense of efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 181-193. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.181 Woolfolk-Hoy, A., Hoy, W. K., & Davis, H. A. (2009). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Hand- book of motivation at school (pp. 627-653). New York: Routledge. Ziegler, A., Dresel, M., & Stoeger, H. (2008). Addressees of perfor- mance goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 643-654. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.643

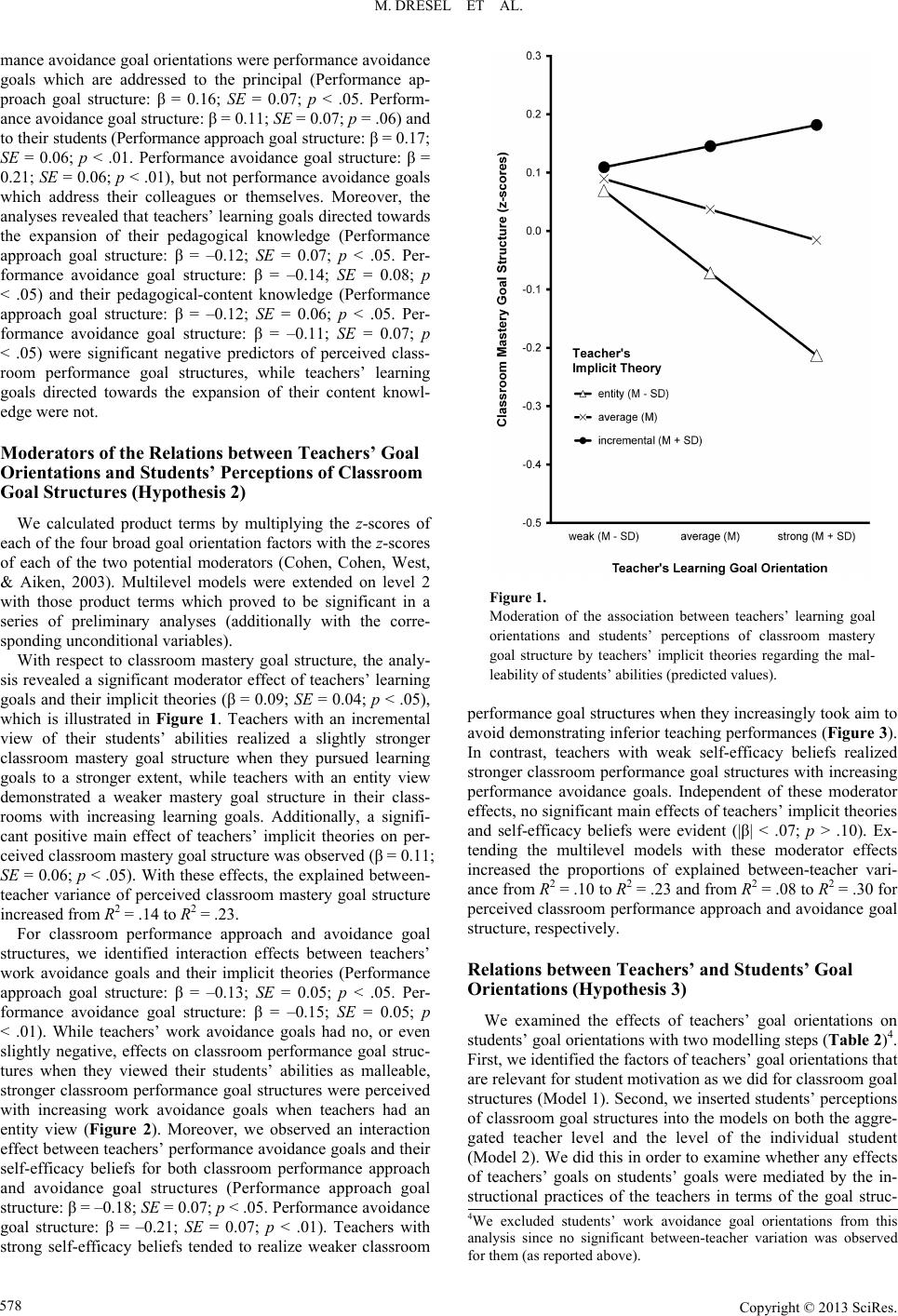

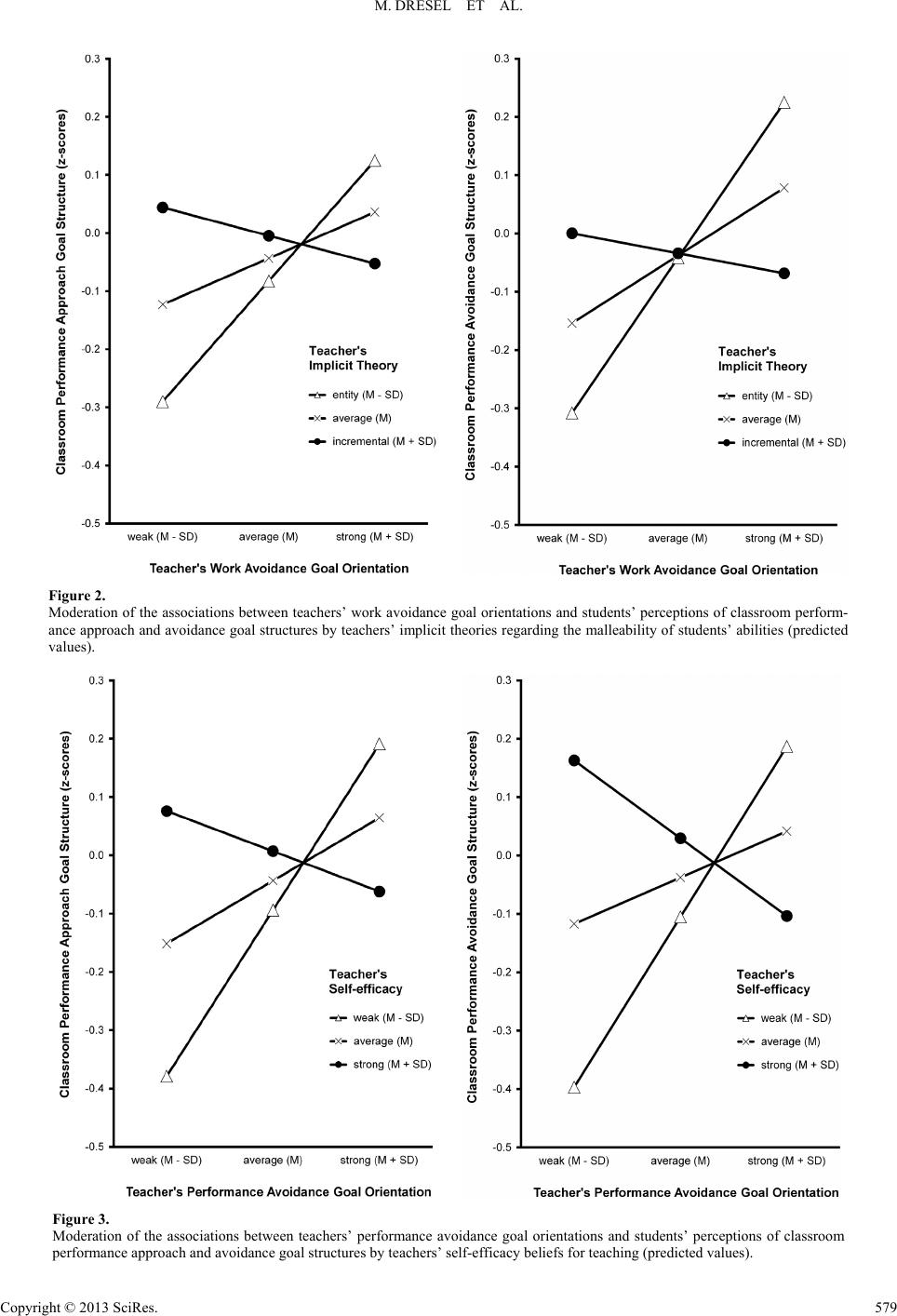

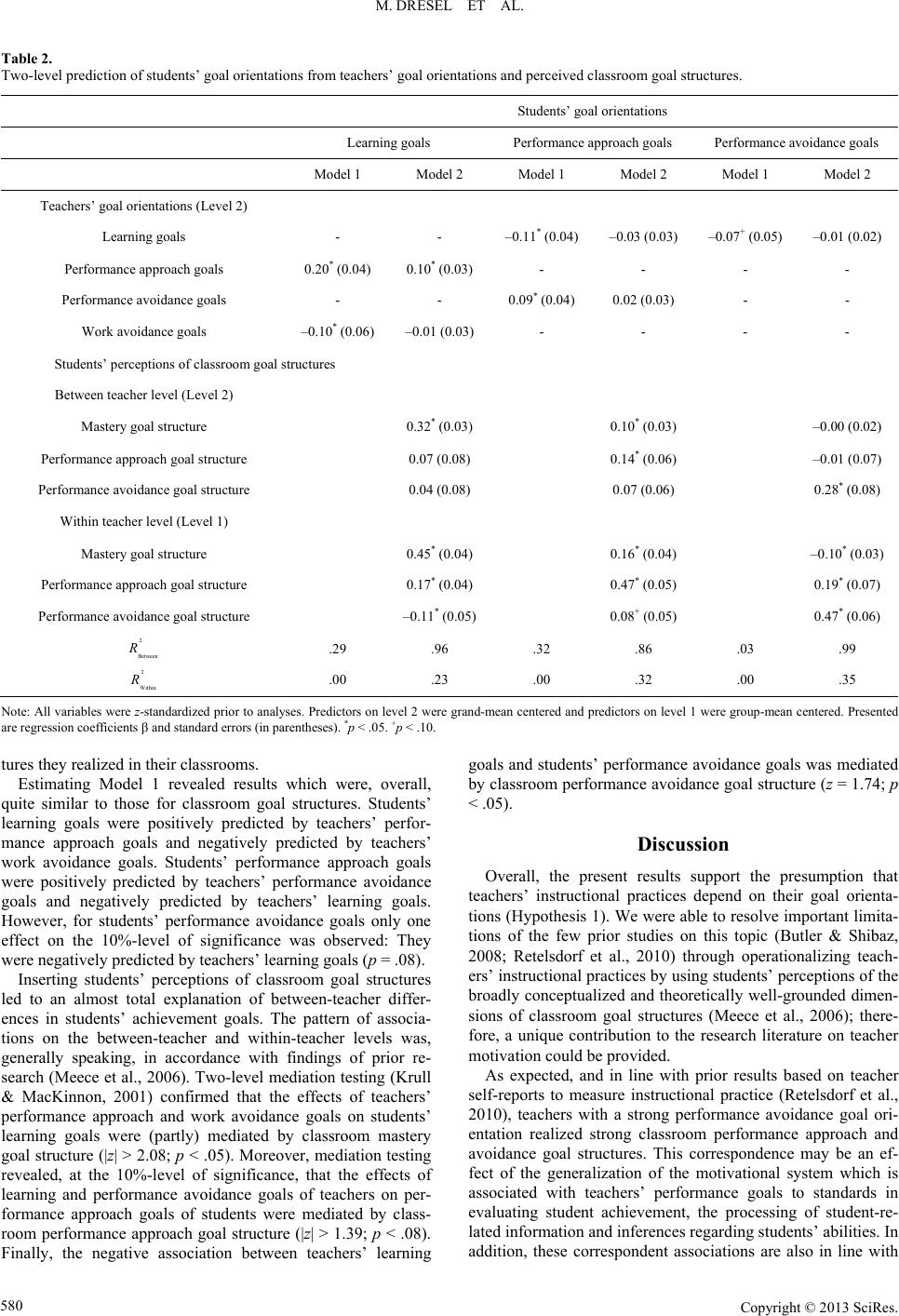

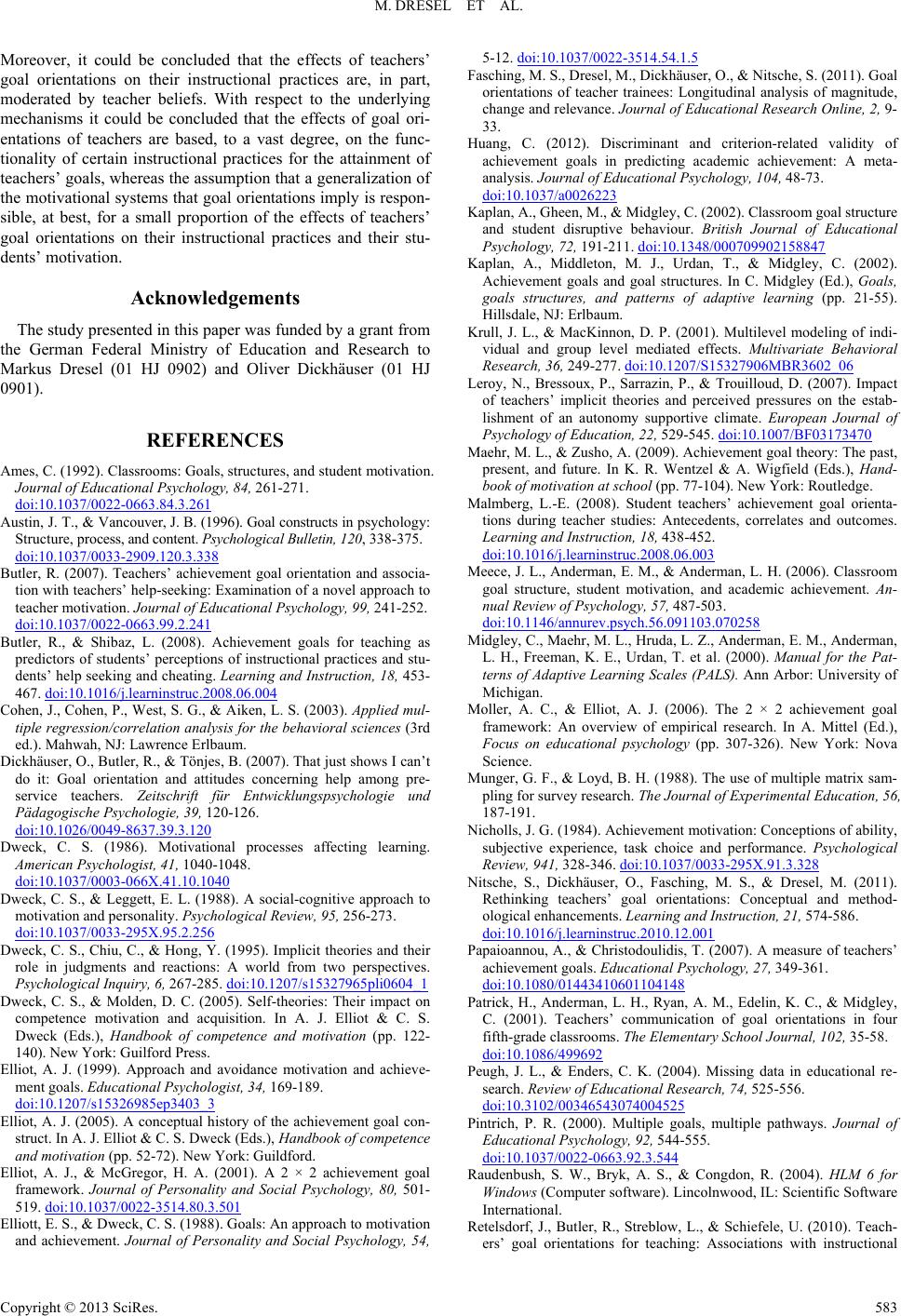

|