Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.6A1, 57-66 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.46A1009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 57 Protective Factors for the Well-Being in Caregivers of Patients with Alzheimer’s: The Role of Relational Quality Caterina Gozzoli1, Antonino Giorgi2, Chiara D’Angelo1 1Department of Psychology, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano, Italy 2Faculty of Education, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano, Italy Email: caterin.gozzoli@unicatt.it Received April 8th, 2013; revised May 11th, 2013; accepted June 9th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Caterina Gozzoli et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The work highlights one of the direct stakeholders of RSA organization, the caregivers of patients with Alzheimer. It studies if and in which measure the caregivers’ level of health are strongly influenced by their perceived Relational Quality of the retirement homes in which their loved ones are hospitalized. Par- ticipants were 111 caregivers of patients with a diagnosis of dementia and recovered in RSA since at least 6 months. The study measures if the relational quality perceived by caregivers has a positive and direct influence on two mood states of caregivers: depression-dejection, anger-hostility. It also investigates if the protective function of relational quality remains significant also in presence of moderator variable such as social support and burden. The analysis confirms that increasing perceived relational quality corresponds to a decreased perception of caregivers’ discomfort humoral. The social support factor does not act as moderator, but it is confirmed the moderator role of burden. The research work provided some important empirical about the important role of caregivers retirement homes. They represent an emotional and rela- tional link that connects the guest on one hand with the familiar net and on the other hand with the service operators. Therefore caregiver is a central resource, who needs protection and valorisation. Keywords: Caregivers Well-Being; Alzeimer’s Disease; Relational Quality Introduction Alzheimer’s dementia falls in the so called primary demen- tiae (or degenerative dementiae), in other words, those forms of progressive and irreversible dementia, that-to this day-are still incurable, because they are caused by a primary brain alteration (Cotelli et al., 2008). This disease usually begins after sixty and the time between the first symptoms of the disease and the death varies from eight to ten years. The gradual, but steady decline, caused by Alzeimer’s disease characterizes itself for a cognitive worsening, that is associated with aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia, behavioural and mood changes-among which depres- sion, nervousness, mood liability, anxiety, sleep and motion disorders, disinhibition-a gradual loss of functional self-suffi- ciency, which corresponds to an ever greater request of cares (Grossberg, 2003). Services struggle to absorbs users and the involvement of the families in the care or caregiving (Pearlin et al., 1990) of the patient is nearly total. Such a task begins with the initial diag- nosis and gradually tends to extend, becoming more substantial, because the patient’s household is called to support the most part of that was defined “the care burden” (Taylor et al., 1985; Ferrel et al., 1990; Nijboer et al., 1998). The caregiver is the one who, in first person takes care of his loved one, assuming a function of accompaniment and physical and material support during the slow decline process (Dunkin & Anderson-Hanley, 1998; Zanetti et al., 1998; Bell, Araki, & Neumann, 2001; Cigoli, 2006). In case of neurodegenerative illness, as the Alzheimer’s de- mentia, caregiving changes and modifies itself in the course of time. From the usual assistance between two people affectively close, it becomes a task that involves the whole relationship, up to arriving to turn the relationship into a unilateral relation, in which one part strongly depends on the other. This overpower- ing condition, that continues for a long time, because of the degenerative nature of the disease, may have very negative ef- fects on the physical and psychological health of caregiver: the care burden he/she experiences, frequently has as its outcome an high stress, that may activate psychopathological states (Miller, Allen, & Mor, 2009; Crespo, Lüpez, & Zarit, 2005; Tamanza, 2001). Today, the attention to caregiving condition is always in- creasing and it is asking, in an ever more pressing way, the necessity to extend the test range. Indeed, the main problems of the caregivers—weariness, stress, anxiety, mood disorders—do not seem to be ascribable only to the carried out task of care and assistance (and then to the serious condition of the relative), not even to the personological features of the subjects involved with the care task, but also to the interaction of factors which are typical of the context in which subjects are included. In front of the same conditions of strain and pain, faced by the caregiver, what can make the difference is the set of relational and social elements (Kahana et al., 1993; Sube et al., 2010). Therefore, the present contribution moves in this direction and studies if and in which measure the caregivers’ level of health are strongly influenced by their perceived relational  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. quality of the retirement homes, in which their loved ones are hospitalized. Given the peculiarity of the residential context for old people in Italy and the newness of the construct of “rela- tional quality” proposed in the present work, below are investi- gated some definitory aspects. The Nursing Homes (RSA) in Italy and the Assessment of Relational Quality According to Decree of the president of the Italian Republic of 14/01/1997, the Nursing Homes/Residenze Sanitarie Assis- tenziali (RSA) in Italy are “presidios which offer to not self- sufficient subjects, old people or not, with consequences of physical, psychic or mixed diseases, not able to be cared at home, a level of medical, nursing and rehabilitative, accompa- nied by an high level of tutelary and hospitality assistance, and, modulated according to the model of care adopted by autono- mous regions and provinces” (D.P.R. 14/01/1997). Literature shows that ricovery in a RSA happens when care- givers do not succeed in doing effectively their care task any- more (Tamanza, 1998; Balardy et al., 2005; Miller, Schneider, & Rosenheck, 2009). The old person and his/her family face a real revolution, that pertains to the generational passage: RSA are, from this point of view, real places in which this passage is managed (Cigoli, Farina, & Gennari, 2008). This means that in the RSA activity, caregivers and operators represent two basic turning points, which carry out specific mediation functions between the patient and the structure, and among the structure, the familiar system and the community (Gozzoli & Frascaroli, 2012). For a while now, just at the light of the awareness to be structures at an high relational rate (Tamanza, 2001), RSA feel the need to monitor clients’ satisfaction compared with the quality of the offered services, in order to improve them as much as possible. Nevertheless, the actual quality assessment models are, as far as we are concerned, incoherent, because they do not consider the intrinsic relationality of such structures. The most diffused quality assessment models are borrowed from an identical ma- trix, born and developped in the industrial overview and then let it pass in this kind of services (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, 1988, 1994). According to such models, the value of the customer satis- faction in the pubblic administration and in the private struc- tures consists in detecting the betterment potential of it, as well as of factors on which is registered the greater gap between what the administration was able to realize and what users ac- tually need or expect to receive from it (Anderson, Farnell, & Lehmann, 1994). Therefore, detecting customer satisfaction serves to build a relation model administration-users based on trust; specifically in Italy, detecting customer satisfaction falls within a mandatory periodical monitoring process of quality of pubblic and private social-health services (Direttiva Ministero Funzione Pubblica, 2003). In the last years we had the development of different and opposite methodological approaches to quality, developed both in international teams and in italian practices: from the sanc- tioning one, aimed at the individuation of errors and the isola- tion of responsibles, to the Clinical Audit focused on the overall assessment of assistance (Kettinger & Lee, 2005), to the Qual- ity Verification and Review (VRQ) (Zanella & Cerri, 2000), up to the theory of the Continuous Quality Improvement, that re- fers to the Total Quality Principles (Ishikawa, 1985; Tanese, Negro, & Gramigna, 2003). Beyond these methods the mainly utilized contribution in the measure of client’s satisfaction, founded on the service perceived quality survey, is the Servq- ual’s model developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml e Berry (1988, 1994). The authors build the perceived quality measure and then the client’s satisfaction through the assessment of expecta- tions, with which users approach to the type of service and to the service perceptions after its fruition. Such comparison is realized by a method called “discrepancy standard”, in which satisfaction is interpreted as a psychological state resulting from a gap between the assessment of prior consumption experience and the consumers’ expectations regarding such experience. This extremely used model in many practical settings, as mar- keting and corporate communication, found application also in detections on health and social contexts, as welfare communi- ties, in which service quality is deeply tied to the perceived quality by single persons involved in it (patients, relatives, in- formal caregivers, operators). The conception of RSA as structures at an high relational rate (Tamanza, 2001) leads us in this context to propose an addi- tional consideration about the adopted model for customer sat- isfaction measure, according to the deepest need to analyze a welfarist system, that for too long time was considered only in its custodialistic aspect. Because of this reason, taking care of the services means also to give meaning to the aspect concern- ing the relation, that unites each actor of the clinic-social sys- tem, represented by an RSA, attributing to this area a crucial meaning in the complex real and symbolic net, that it comes to represent for families entering in its circuit. Then it seems advantageous to combine a service satisfaction measure with also an assessment of the relational quality inside the welfare context, so that the relationship among operators, informal caregivers and guests becomes the summit from which we are able to monitorate the provided services. In fact the sa- tisfaction of the relational area could represent a possible pre- dictor of the relational and existential quality of patients in welfare structures (Gill et al., 2003) and of their relatives, called to redefine the borders of their space of life. Therefore, in this perspective the quality of a service cannot be determined in itself—as objective measure of the gap be- tween the projected model (ideal) and the service provided (real) —but it needs to consider the subjective variability of user per- ceptions, who is an actor actively present and involved in the same process of service production (Cigoli & Farina e Gennari, 2008). Therefore the present work introduces in the quality assess- ment of RSA a variable (Relational Quality) that investigates the caregivers’ perception of the relation between themselves and the actors involved in the cure process. Goal and Research Hypothesis In the light of what is stated, it was decided to define as ob- ject of analysis of the present work, the perception that care- givers have about the taking care of the patient and his family system by RSA service. This in order to investigate if and in what measure such assessment affects the psychophysical well- being/discomfort of caregivers. Specifically, the research hy- potheses are the following: 1) The perceived relational quality has a positive and direct influence on two mood states of caregivers: depression-dejec- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 58  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. tion, anger-hostility; 2) Social support and burden are two moderator variables of the relation between relational quality and the two mood states; 3) The protective function of relational quality remains sig- nificant also in presence of moderators; 4) Hypotheses are confirmed also after the introduction of control variables. Methods Procedures A questionnaire was used for the survey of personal and so- cial data and a structured grid for the participant selection; all participants received explanations and clarifications about re- search purposes and signed the informed consent. Participants The inclusion criteria in the work were the following: being caregivers of patients with a diagnosis of dementia and recovered in RSA since at least 6 months; being caregivers, who keep taking care of the old person, going to RSA at least three times a week, continually. The participants are 111 caregivers with an average age of 61, 16 years (SD = 8.05). For the gender variable, the participants are divided almost equally between 51 males (45.9%) and 60 females (54.1%). This fact differs from what was considered by literature (Gallicchio et al., 2002) that predicts a great preva- lence of female gender on the male gender in the undertaking of caregiver role. The 25% of caregivers are under the age of 57, the 50% are aged between 57 and 67, the remaining 25% are over 67. With regard to marital status, almost all of the participants are mar- ried (85%). Employment status has the 53% of retired caregiv- ers, with a slight prevalence of males on females (32 vs 27). About the 13% are housewives and the 24% has an employ- ment. Measures Indipendent Variable Measures Assessment of Relational Quality (VQR)—Caregivers Scale (Cigoli, Farina, & Gennari, 2008). VQR is a measure and assessment system of the set of pro- cedures and strategies implemented by RSA to preserve and support the relational and familiar net of the old guest; it allows to obtain a total analysis, from which acquiring the strong points and the areas liable to improvement. The relational quality measure perceived by caregivers was obtained from the average of six indices: “Assessment of the user at the entrance”, “Admission protocols”, “Elaboration of individualized intervention projects”, “Relationship with the guest in an ordinary situation”, “Management of critical events in the relationship with the user”, “Relationship with the family and with other user’s significant subjects”. The questionnaire items addressed to caregivers consider a multiple-choice answer, in which the subject indicates, if inside RSA a series of practices—inherent to the six indices listed above—is present (“yes”) missing (“no”) or if he/she is not aware (“I do not know”). In case of affirmative or negative answer, the questionnaire considers also that the caregiver states the importance attributed to such practice through a closed-answer on three level Likert’s scale, from 1 (“indispen- sable”) to 3 (“irrelevant”). Below it is proposed an example of an item. The structure in which your relative is hosted, conducts accompaniment to the death? YES, and I believe that: - this is indispensable - this is useful - this is irrelevant 1 2 3 NO, and I believe that: - this is a serious default - this may compromise a good quality of life - it is irrelevant for a good quality of life 1 2 3 I DO NOT KNOW The tool reliability is very good (alpha = .82). The contents of the questionnaire came out thanks to a the conduction of “focus groups” with sector operators (doctors, nurses, psychologists and educators), aimed at the individuation of aspects that are able to operationalizing the structure com- mitment in taking care of sick people. The preliminary version of the survey questionnaire elaborated in this way, was pre- sented to operators and relatives of ten RSA structures from Lombardia. A standardization procedure is in progress (still in progress through the site www.cencigallingani.it) with a sample built since 2003 and that involved 90 RSA structures, within which were contacted over 1.500 subjects. Potencial Mediating Variables Caregiver Burden Inventory (Novak & Guest, 1989; Italian Validation Marvadi et al., 2005). Caregiver burden means the care burden that caregivers as- sume, often developing an intense and prolonged stress situa- tion; more precisely to experience this type of reaction would be caregivers, who are not be able to fit themselves or modify their strategies to face demands for care (Given et al., 1999; Clyburn et al., 2000). The italian adaptation of tool, that considers four dimensions (Marvadi et al., 2005): Time-Dependence Burden, Physical Burden, Social Burden, Emotional Burden. The score sum ob- tained in the four one, states the perceived burden degree. At high scores in the subscale correspond high levels of burden perceived by the caregiver. The total score sum in the subscale states the total stress burden of the caregiver. A total score greater than 36 states a risk of burning out, while scores close or slightly greater than 24 state the need of looking for some type of substitute assistance. It is a specific stress measure, that includes two aspects: a “personal” dimension, that is the care- giver’s subjective perception about the problems regarding his or her personal situation, caused by caregiving activity; and the “interpersonal” one, that is caregiver’s perception of the rela- tional problems between caregivers and carereceivers. This specific stress conception was preferred to more common ones, just to try to contain the vagueness and the confusiveness that mark the concept. All twenty one items consider a close answer on four level Likert scale, from 0 (= never) to 4 (= almost never); Examples of items are: “In general, how often do you feel like you’ve lost control over your life”, “How often do you feel you receive excessive help requests”, “How much does your spouse/loved one depend on you as the caregiver”. The Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 59  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. reliability is very good (alpha = .80). Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet et al., 1988; Italian Validation Prezza & Principato, 2002). Perceived social support means the set of social relation, that play a role in keeping the psychophysical integrity of an indi- vidual. (Caplan, 1974; Sube et al., 2010). The loss of a suitable social support is related to the intensity of physical symptoms (Cohen & McKay, 1984; Bolgerand & Amarel, 2007). The scale, composed of 12 items, considers the perceived support compared with three subscales: family, friends and significant figures in the wider social field. Each subscale is composed of 4 items with a codified answer mode on a seven point scale from 1 (= totally disagree) to 7 (= fully agree); examples of items are “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family”, “I have friends with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”, “There is a special person in my life who cares about my feel- ings”. The corresponding score to each area is obtained from the average of four questions included within each of them. The total score is obtained from the average of all the questions and allows to make a subjective assessment of the social support suitability; such a score allows to makes a subjective assess- ment of the social support. The reliability is very good (alpha = .88). Dependent Variable Measures Profile of Mood States (McNair et al., 1981; Italian Valida- tion Farnè et al., 1991). The increasing interest for mood states and changes, has given rise to the need of an easy and quick method to identify and quantify particular affective states; so this inventory was built, that measures six factors and as many mood states, going from anxious tension to sense of disorientation The six factors are particularly useful to assess patients with neurotic or stress disorders. The inventory adapted to Italian population (Farnè & Sebellico, 1986) is constituted of 58 items and consists of 58 adjectives and attributive expressions evaluated on a five levels Likert’s scale (0 = nothing at all; 4 = very much), that define six different factors: “Tension-anxiety” or T factor, “Depression- dejection” or D factor, “Anger-hostility” or A factor, “Vigor- activity” or V factor, “Fatigue-inertia” or S factor S, “Confu- sion-bewilderment” or C factor. Subjects are asked to report the answer, that better describes “how have you felt in the last week, including today”. In addition, the factors remain constant in time, when they are asked to indicate their condition both in the immediate present and in the period of a week. In addition to the score for each factor, it is possible to extract a total score given by subtracting the score to the “Vigor-activity” scale from the total sum of raw scores of every scale. The higher the score, the higher the level of severity. For research purposes were used only 2 scales, which in literature result more charac- teristic of the staying in RSA (Tamanza, 2001): “Depression- dejection” e “Anger-hostility”. The single scales give birth to raw scores, mutually inde- pendent, then transformed into T points. The “Depression-de- jection” scale is composed of 15 items. In it are described feel- ings regarding a depressed mood, that goes from the melan- choly to the perception of lack of support from family and friends, to lack of hope in the future and to deep disesteem. It is proposed as an example the items “sorrowful”, “dejected”, “helpless, thrown over”, “a worthless person”. The “Anger- hostility” scale is composed of 12 items. It describes a mood of anger and antipathy towards others. Feelings of intense and clear anger, feelings of more attenuate hostility and feelings of resentment and distrust are moreover described. It is proposed as an example the items “angry”, “highly strung”, “livid”, “ready for pick a fight”. In the present survey the reliability turns out to be excellent for the “Depression-dejection” factor (alpha = .92) and for the factor “Anger-hostility” (alpha = .93). Analysis For the present work we have chosen a non- experimental analysis strategy, that is a cross-sectional research design (Hen- nekens & Buring, 1987; Grimes & Shultz, 2002) of correla- tional type (McBurney & White, 2009), in order to highlight co-variations of design variable (relational quality) and of ob- served variable (mood disorders). In addition, the analysis pro- cedures considered the investigation of possible moderation of two specific variables (caregiver burden and perceived social support) on the observed variable. A preliminary level of statistical data processing concerned the descriptive analysis of the indices of different scales, a sec- ond level of statistical analysis involved the use of the correla- tion (Pearson’s correlation coefficient), in order to verify the existence of statistically significant connections among the va- riables object of research. Based on the results obtained, a third level of analysis was carried out using simple regression to investigate the direct in- fluence of the relational quality perceived/recognized by care- givers on two mood states (“Depression-dejection”, “Anger- hostility”) of caregivers themselves. Finally, through the multi- ple hierarchical regression, it was investigate the role of mod- erator variable, both of stress (burden) and the social support about the existing relation perceived/recognized by caregivers and their three mood states. A last level of analysis concerned the validity through the multiple regression, of model verification even after the intro- duction of control variables selected by literature. Results Compared to the perceived relational quality, the sample shows an average of 67.83 points out of 100 (SD = 16). Fur- thermore, such index calculated separately in the male group, who reported an average of 67.88 (SD = 16.78) and in the fe- male group, who reported an average of 67.79 (SD = 15.45), does not present statistically significant differences (T-Test: p = .977). The Caregiver Burden Inventory has an average score of 27.23 (± 16.25). Furthermore, such index calculated separately in the male and female group does not differ significantly. (T-Test: p = .615). The females have an average of 27.95 (± 16.04), while males have an average of 26.38 (± 16.61). The sample averages the individual subscales are represented in Figure 1. For CBI, in literature we have the following cut-off: 1) scores 0 - 24: no stress; 2) scores between 25 - 36: stress is present with need of help; 3) scores beyond 36: high degree of stress (risk of burn out). The participants are distributed in three levels with the following percentages: 50% at the first level, 19% at the second level, 31% at the third level. Significant differences in the subgroups are not observed (test Chi-Square: p = .963). Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 60  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. 6,23 14,3 3,38 3,38 0 5 10 15 Time-Dependence Burden Physical Burden Social Burden Emotional Burden Figure 1. Burden subscales. As for the perceived social support it is obtained an average of 3.9 (± 1.5) and is statistically lower than the normative av- erage (Z-Test: p < .001). Not significant differences between males and females (T-Test: p = .187). In the three subscales, family, friends, significant figures, are observed the following averages: 5.2 (± 1.7), 3.5 (± 2.0), 3.6 (± 2.3). All the subscale averages are significantly lower than the respective normative averages. Subdividing the social support into three groups according to the normative values (1. low social support: scores below aver- age − 1 SD; 2. medium social support: score between the aver- age − 1 SD e media + 1 SD; 3. High social support: scores above the average + 1 SD), it is obtained the following fre- quency distribution: the 75% of subjects perceives a low social support, the 22.5% medium and the remaining 4.5% an high social support. Compared to mood states, the participants, as for the “De- pression-dejection” factor, have an average score of 55.77 (SD = 13.56). In addition, such index calculated separately in the male and female group does not differ significantly: male av- erage 57.73 (SD = 14.32), female average 54.10 (SD = 12.76) (T-Test: p = .161). As for the “Anger-hostility” factor, the aver- age score is 53.52 (SD = 13.44). Furthermore, such index cal- culated separately in the male and female group shows signifi- cant differences of borderline significance: male average 56.20 (SD = 14.89), female average 51.25 (SD = 11.83) (T-Test: p = .058). From correlation analysis stands that relational quality corre- late negatively in a significant way, both with the “Depres- sion-dejection” factor and with the “Anger-hostility” factor, as shown in Table 1. As for the total measure of caregivers’ burden, it is detected a positive correlation significant both with the “Depression-de- jection” factor and with the “Anger-hostility” factor, as shown in Table 2. As for social support perceived by caregivers, it does not correlate with any of the two considered mood states, as shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 4 perceived Relational Quality variable Table 1. Correlation of relational quality perceived by caregivers with dependent variables. “Depression-dejection” factor −.358 (**) “Anger-hostility” factor −.290 (**) Note: *p < .05; **p < .01. does not correlate significantly with any other variables. On the basis of these results it was possible: affirm that the Relational Quality perceived by caregivers is inversely correlated to the factors related to the interaction of the caregivers’ mood state; establish from now that the perceived social support cannot function as moderator of relationship between Relational Quality and “Depression-dejection”, “Anger-hostility” fac- tors, because there is no significant correlation with the ob- served variables; deepen the nature of the link between each of two factors “Depression-dejection and “Anger-hostility” with Rela- tional Quality; analyze the possible moderation role of the Burden variable in the relation between the perceived Relational Quality and factors “Depression-dejection and “Anger-hostility” factors; verify if the results of the previous analyzes remain previ- ous analyzes, even in the presence of control variables. Through a simple linear regression we proceeded to analyze the possible direct influence of independent variable of the per- ceived Relational Quality with the two observed factors: “De- pression-dejection” and “Anger-hostility”. The regressions were carried out with standardized scores of the perceived Relational Quality variable, for a more direct interpretation of regression coefficients (Fazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004). The regression model is significant (p < .001) and explains the 12% (R2 adjusted) of the total variance of the “Depression- dejection” factor. The regression model is moreover significant (p < .002) and explains the 7.6% (R2 adjusted) of the variance of the “Anger- hostility” factor. Finally, according to the model proposed by Fazier Tix e Table 2. Correlation of caregivers’ burden with dependent variables. “Depression-dejection” factor .533 (**) “Anger-hostility” factor .434 (**) Note: *p < .05; **p < .01. Table 3. Correlation of social support perceived by caregivers with dependent variables. “Depression-dejection” factor −.018 “Anger-hostility” factor .003 Note: *p < .05; **p < .01. Table 4. Correlations between indipendent variables and possibile moderator variables. Relational Quality Burden Social Support Relational Quality1 −.136 .047 Burden −.136 1 −.048 Social Support .047 −.048 1 Note: *p < .05 ; **p < .01. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 61  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62 Barron (2004) on the basis of the indications of Cohen e Cohen (1983), we proceeded to the analysis of the possible moderation model through multiple hierarchical regression per step: As you can observe the Relational Quality has a different in- fluence in the three groups. With the decrease of the level of Burden the direct influence of the Relational Quality on the “Depression-Dejection” Factor diminishes. In particular, at a low level of Burden, the Rela- tional Quality does not influence the levels of the observed variable. 1) regression of the observed variable on the perceived Rela- tional Quality variable and on the Burden moderator variable perceived by caregivers; 2) regression of the observed variable on the perceived Rela- tional Quality variable and on the Burden moderator variable perceived by caregivers and on the interaction between per- ceived Relational Quality and perceived Burden. The first step of regression results significant (p = .000), as well as the second step, that is the moderation effect (p = .037) (Tab le 7 ). The total model explains the 25% of the variance of “Anger-hostility” Factor. The interaction explains ad additional 3%. To see moderation effect we resorted to its graphical repre- sentation with procedures indicated by Frazier, Tix e Barron (2004). The two steps of regression result significant, in particular the one compared with the moderation effect (p = .001) (Table 5). The total model explains the 41% of variance of the “De- pression-dejection” factor. The interaction explains an addi- tional 6%. Regression coefficients are indicated in Table 6. At a medium level of Relational Quality and Burden, the medium level of the “Depression-Dejection” Factor is of 55.36. Moreover, an increase of one point of the Relational Quality, on equal terms for other variables, diminishes the “Depression- Dejection” Factor of 3.19 scores. On the contrary the Burden, at its unitary increase, always on equal terms for other variables, increases of 6.26 scores the “Depression-Dejection” Factor. The Burden moderation effect turns out to be of −3.05. To better see the Burden moderation effect, it is shown the graphic (Figure 2). Figure 2. Graphical representation of the burden moderation effect on the “De- pression-dejection” factor. Table 5. Moderation model—“Depression-dejection” factor. Change Statistics Model R R Square Adjusted R Square Std. Error of the Estimate R Square ChangeF Change df1 df2 Sig. F Change 1 .606a .367 .355 10.884 .367 31.317 2 108 .000 2 .652b .425 .409 10.424 .058 10.738 1 107 .001 Table 6. Regression coefficients—“Depression-dejection” factor. Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized Coefficients Model B Std. Error Beta T Sig. (Constant) 55.766 1.033 53.980 .000 Relational Quality −3.942 1.047 -.291 −3.763 .000 1 Burden 6.690 1.047 .494 6.387 .000 (Constant) 55.356 .997 55.505 .000 Relational Quality −3.189 1.029 −.235 −3.099 .002 Burden 6.260 1.012 .462 6.187 .000 2 Moderation Effect −3.049 .931 −.250 −3.277 .001 Note: aDependent Variable: Depression-Dejection Factor.  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. Regression coefficients are indicated in Table 8. At a medium level of Relational Quality and Burden, the “Anger-hostility” Factor is 53.23. From the model results that an increase of a score of Relational Quality, on equal terms for other variables, diminishes the “Anger-hostility” Factor of 2.63 scores. On the other hand the Burden, at his unitary increase, increases of 5.09 scores the “Anger-hostility” Factor. Also, in this case, as you can observe from graphic (Figure 3), the Rela- tional Quality has a different influence in the three Burden groups. In particular, with the decrease of the level of Burden, the direct influence of the Relational Quality on the “Anger- hostility” Factor diminishes, till the effect at a low Burden level, becomes almost nil. Considering the presence in literature of variables omitted in the two models, that could disguise or modify the obtained results, we proceeded to verify the validity of moderation hy- pothesis, introducing control variables. Discussion A first significant element is related to the research sample of this work. In effects the participants are 111 caregivers, almost equally divided between males (45.9%) and females (54.1%). This element differs from what was highlighted by an ample literature, that considers a clear predominance of the female gender on the male one, in the undertaking of caregiver role: they are overwhelmingly women (73.8% and the percentage rises to 81.2 if the disease is at an advanced stage) (Gallicchio et al., 2002). In and of itself, this condition makes the results of the survey very specific, while reasons may be multiple. This confirms an element in literature, that is the properly intergenerational nature of undertaking the caregiver role (Cigoli, 2006). Indeed, the caregiver role depends mainly upon the immediate following generation: 73% are sons. The guest socio-demographic characteristics show a rather high average age (beyond eighty) and a significant imbalance between gen- ders (77% are females). In relation to the general objective of the research work, both by a correlational analysis and by a regression one, it was con- firmed in a significant way, that at the origin of a protection effect on caregiver mood states, there is a good Relational Quality perceived by them. In other words, the Relational Qual- Figure 3. Graphic representation of the burden moderation effect on the “Anger- hostility” factor. Table 7. Moderation model—“Anger-hostility” factor. Change Statistics Model R R Square Adjusted R Square Std. Error of the Estimate R Square ChangeF Change df1 df2 Sig. F Change 1 .493a .243 .229 11.802 .243 17.294 2 108 .000 2 .522b .273 .252 11.618 .030 4.460 1 107 .037 Table 8. Regression coefficients—“Anger-hostility” factor. Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized Coefficients Model B Std. Error Beta t Sig. (Constant) 53.523 1.120 47.778 .000 Relational Quality −3.165 1.136 −.236 −2.787 .006 1 Burden 5.398 1.136 .402 4.753 .000 (Constant) 53.228 1.111 47.889 .000 Relational Quality −2.625 1.147 −.195 −2.288 .024 Burden 5.090 1.128 .379 4.514 .000 2 Burden Moderation −2.190 1.037 −.181 −2.112 .037 Note: aDependent Variable: Anger-hostility Factor. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. ity seems to be a protection and support factor for caregivers. This support, indeed, may be provided not only by the “natural” nets (we talk about informal support), but also by all, who are part of the “not natural nets” (in this case we talk of formal support), as the entire organizational and professional net of RSA. Basically, the more problematic effects of the caregiving process, that is the effects that may outcome in mood disorders, appear to be modulated by variables of contextual and rela- tional order: in the research the perceived Relational Quality is a contextual and relational variable, that performs a protective function. This proves to be even more significant, if matched with what emerges, in Tamanza’s works (2001), compared with the protective function carried out by the “Quality of family functioning”. Regarding the “Depression-Dejection” Factor, par- ticipants result to be depressed (35.10%) and very depressed (22.50%). Regarding the “Anger-hostility” Factor the 37.80% result to be aggressive, while the l’ 11.70% very aggressive. In agreement with literature (Novak & Guest, 1989), the research obtained data provide a very clear picture: the majority of care- givers suffers, at rather high degree, from depressives and ag- gressive states. Caregivers suffer also from a high stress level: in the 50% are people who need an immediate support and help. The results suggests that the perceived Relational Quality seems to have a different influence on the two considered mood states. Caregivers are more strongly protected for the “Depres- sion-Dejection” Factor (R2 adjusted = 12%), while less strongly about the “Anger-hostility” Factor (R2 adjusted = 7.5%). This result is not comparable to any literature datum, there are no researches on this matter. However, we can try to comment the obtained data. Depression could be assimilated to an emotional residue of a precise elaboration process. In other words, at the acquired awareness of the serious and distressing situation and its con- sequences. In RSA, a good perceived Relational Quality seems to help caregivers to face this depressive process, in order to elaborate both the experiences related to the depressive state (guilt, feelings of worthlessness and sense of helplessness) and the very distressing ones, (that is to feel themselves symboli- cally cause of the death of their loved one,) even to face the inevitable aspect of real death. In RSA you enter, but from RSA you exit, in the vast majority of cases, only after the guest’s death (area 5 and area 6 of VQR). On the contrary, aggressivity may express a difficult just to undertake such elaborative proc- ess. It is an anger, that surrounds the cure and that may move in many directions, among which we find more frequently the class of sanitary operators, or may move in the direction of re- latives or other dear ones, perceived not enough involved, or even in the direction of the suffering old, who, with the passing of time, always asks for more. Among the presumed moderator variables, the perceived So- cial Support did not result as a moderation factor. Effectively, in the research sample, the 73% reports a low level of Social Support, while only the 4.5% reports of a high level of per- ceived Social Support. It is possible to comment on this result by referring to the fact that most likely the long and difficult caregiving task has in fact caused an impoverishment of social nets, and has strongly influenced the perception of social isola- tion, that caregivers experience. This element is similarly pre- sent in literature: the perception of lack of social support influ- ences in a significant way caregiver mental and physical health. The caregiver’s social nets of kinship and friendships with the passing of time undergo a contraction (Caplan, 1974; Sube et al., 2010). Regard the caregivers’ Burden, the data suggest that partici- pants are distributed in three burden levels with the following percentages: 50% at the first level, 19% at the second level, 31% at the third level. In substance, the sample is divided al- most in half between a medium-high burden level and a low or absent burden level. Even in this case the literature showed that the Burden level experienced by caregivers, influence their mental and physical health in a significant way (Clipp & Geroge, 1993; Novack & Guest, 1989; Zarit & Toseland, 1989). In relation to the hyphotesis that caregivers’ Burden function as a moderation factor, the obtained data confirm this hypothe- sis. Along these lines it can be argued that Burden functions as moderator, because it may be intended as the more immediate measure of caregivers’ discomfort, provoked by their care work practice, long before entering in RSA. It represents the first display of caregivers’ burn-out, a kind of manifestation of the work strain, that associates in a generalized and almost inevita- ble way all who carries out such function. Data confirm also the hypothesis, sustained by literature, that burden is highly related with mental and physical discomforts, which are more evident in caregivers (Given et al., 1999; Clyburn et al., 2000). Returning to the Burden moderation effects, the obtained data highlight that they control the relation between the per- ceived Relational Quality and the “Depression-Dejection” and “Anger-hostility” Factors. Even if with different graduations, in presence of the Burden moderator variable, the protective func- tion of Relational Quality perceived by caregivers, remains significant. Examining in depth the moderation effect, we deduce that Burden influences the relation strength between the perceived Relational Quality and the “Depression-Dejection” Factor and the relation between the Relational Quality perceived and the “Anger-hostility” Factor. In the first case, with the decrease of the Burden level, the direct influence of the Relational Quality on the “Depression-Dejection” Factor decreases. In particular at a low Burden level the Relational Quality does not influence the levels of the observed variable. Basically, in the second case, we have the same trend as the first one. The perceived Relational Quality has a different in- fluence in the three Burden levels. In particular, with the de- crease of its level, the direct influence of the Relational Quality on the “Anger-hostility” Factor diminishes, until to make al- most nil the effect, at the level of low Burden. These data assert that certainly Burden is a measure of care- giver’s mental and physical discomfort, which already existed prior the entering in RSA. Clearly, with the entering in RSA, it may increase again or decrease its intensity. However, what appears to be important, is that Burden seems to be strongly predictive of caregivers’ depressive and aggressive states. So, along these lines RSA has to consider the importance of this factor and consequently work in order that caregivers have a low or nil burden. In substance the data assert that Burden is predictive of the caregivers’ depressive and aggressive states and therefore we should pay the greatest attention to this factor. The attention should be also promptly operative from the structure in order to keep this factor at a sufficiently low level. Its assessment, be- sides ongoing, should concern above all the entrance stage in RSA, just for the symbolic significance of entering in the structure, that if it is invented effectively, it is able to represent Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. a domain of winning strategic intervention to make faithful the relationship between caregivers and RSA. The expressed hypothesis is valid even after the introduction of some typical control variables, selected from literature and despite the obtained results are not generalizable; it seemed important to examine in depth, from a scientific point of view, this segment of organizational functioning, with the auspice that further researches can extend the theoretical-methodo- logical models in this area, or that possible operational reper- cussions take a run-up, increasing RSA efficiency. Moreover, since for a good result you need a powerful statistical test of at least 0.80 (Cohen, 1988), almost never reached in the per- formed tests of this work, it is appropriate to predict for the news works an increase of the number of the examined subjects. The non experimental research is often the first step to begin to answer to theoretical questions with empirical methods. So it is indispensable to continue the studies, both to find a further con- firmation of the obtained results and to verify the possible in- fluence of other not considered variables in the examined mod- els. Conclusion The work highlights one of the direct stakeholders of RSA organization, in other words the caregivers of patients with dementia. RSA are required to have a different attention to its stake- holders, performing it also and above all in the way they are able to communicate and relate to caregivers. Therefore Rela- tional Quality seems to be a basic aspect. It was evidenced that a lot of scientific literature on the care- giving process in RSA, shows how much it affects also the health and the well-being of caregivers due, but not only, to an insufficient Relational Quality. This could provoke also a col- lapse of confidence and recognition towards RSA and weaken the patient care process. In this sense, the research work provided some important empirical data, taking a picture of caregivers’ state of health, it aimed at providing a measure of the perceived Relational Qual- ity and even in presence of other intrinsic and extrinsic factors, how much it is able to provide a protection for caregivers re- garding negative and painful aspects of their care task. This prophylactic strategy towards caregivers becomes a valorisation and a recognition of these interlocutors’ role, raising roundly the Relational Quality and the care process in whole. Precisely the institutional and organizational nature of RSA pushes to advance this hypothesis: an organization that takes care must be careful and analytical about the care functions that are generated spontaneously or in advance. The role of relative responsible for the care if on one hand, as we saw, may produce psychic discomfort, on the other it may become, if adequately invented, a possibility to contribute both to the old person’s well-being, and to the good functioning of RSA. Indeed the caregiver represents an emotional and relational link that con- nects the guest on one hand with the familiar net (avoiding the risk of old person’s isolation and affective impoverishment) and on the other hand with the service operators. Therefore care- giver is a central resource, who needs protection and valorisa- tion already inside RSA. The proposed research looks at caregivers in this perspective and individuates in the Relational Quality perceived by rela- tives in RSA a work and growth tool for organization in support of the care processes therein generated. The premise for the real implementation of all this lies in the quality of organizational interest that enterprise should reserve to caregivers. This means that the PR contribution, interpreting Gruning’s lessons (1984) would permit to orientate the enterprise interest to parameters. In this sense caregiver should be a bearer of interest since it becomes a relational driving force for organiza- tion, that in this way would acquire confidence and not only among publics, but also in the collective feeling and thinking. In this sense it is important to evidence that advantages of realizing services careful to exquisitely relational parameters and not only economic ones, would fall not only to caregivers, the guest and his/her family, but would influence, even if mini- mally and indirectly, the community. Such a net work would allow that RSA should carry out the “hinge” functioning be- tween district and citizens, often lacking or ineffective. This research work shows from this perspective all its prac- tical versatility, since it does not stop at caregiver’s diagnostic frame, but it profiles, for this target, possible interventions of prevention and support. REFERENCES Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Finding from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58, 53-66. doi:10.2307/1252310 Balardy, L., Voisin, T., Cantet, C., & Vellas, B. (2005). Predictive factors of emergency hospitalization in Alzheimer’s patients: Results of one-year follow-up in the REAL. Fr Cohort. The Journal of Nutri- tion, Health & Aging, 9, 112-116. Bell, C. M., Araki., S. S., & Neumann, P. J. (2001). The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 15, 129-136. doi:10.1097/00002093-200107000-00004 Bolgerand, N., & Amarel, D. (2007). Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. Journal of Personal- ity and Social Psychology, 92, 458-475. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458 Caplan, G. (1974). Support system and community mental health. New York: Behavioral. Cigoli, V. (2006). L’alber o d el la d is ce nde nz a. Milano: Franco Angeli. Cigoli, V., Farina, M., & Gennari, M. (2008). Dalla valutazione della qualità relazionale all’assessment familiare nelle Residenze Sanitarie Assistenziali: Un programma di ricerca intervento. Giornale di Psi- cologia, 2, 19-30. Clipp, E. C., & Geroge, L. K. (1993). Dementia and cancer: A com- parison of spouse caregiver. Gerontologist, 33, 534-541. doi:10.1093/geront/33.4.534 Clyburn, L., Stones, M., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Tuokko, H. (2000). Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Gerontology: Soc ia l S ci en ce s, 55B, S2-S13. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sci- ences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Cohen J., & Cohen P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erl- baum. Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffer- ing hypothesis. A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, J. E. Singer, & S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (pp. 253-267). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Cotelli, M., Manenti, R, Cappa, S. F., Zanetti, O., & Miniussi, C. (2008). Transcranial magnetic stimulation improves naming in Alz- heimer disease patients at different stages of cognitive decline. Euro- pean Journal of Neurology, 15, 1286-1292. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02202.x Crespo, M, Lüpez, J., & Zarit, S. H. (2005). Depression and anxiety in primary caregivers: A comparative study of caregivers of demented Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  C. GOZZOLI ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66 and nondemented older persons. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20, 591-92. doi:10.1002/gps.1321 Dunkin, J. J., & Anderson-Hanley, C. (1998). Dementia caregiver bur- den: A review of the literature and guidelines for assessment and in- tervention. Neurology, 51, S53-S60. doi:10.1212/WNL.51.1_Suppl_1.S53 Farnè, M., & Sebellico, A. (1986). Emotional reactions in stress condi- tions: The effect of boredom and mental overload. Bollettino della Società Italiana di Biologia Sperimentale, 62, 553-559. Farnè, M., Sebellico, A., Gnugnoli, D., & Corallo, A. (1991). POMS. Profile of Mood States: Adattamento italiano. Firenze: Organizzazi- oni Speciali. Ferrell, B. A., Ferrell, B. R., & Osterweil, D. (1990). Pain in the nurs- ing home. Journal of t h e American Geriatric Society, 38, 409-414. Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 115-134. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115 Gallicchio, L., Siddiqi, N., Langenberg, P., & Baumgarden, M. (2002). Gender differences in burden and depression among informal care- givers of demented elders in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 154-163. doi:10.1002/gps.538 Gill, P., Kaur, J., Rummans, T., Novotny, P., & Sloan, J. (2003). The hospice patient’s primary caregivers. What is the quality of life? Journal of Psychosomatic Re sea rch , 55, 445-451. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00513-0 Given, C. W., Given, B. A., Stommel, V., & Azzouz, F. (1999). The impact of new demands for assistance on caregiver depression: Tests using an inception cohort. Gerontologist, 39, 76-85. doi:10.1093/geront/39.1.76 Gozzoli, C., & Frascaroli, D. (2012). Managing participatory action research in a health-care service experiencing conflicts. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Jour- nal, 7, 275-289. doi:10.1108/17465641211279752 Grimes, D. A., & Schulz, K. F. (2002). An overview of clinical re- search: The lay of the land. Lancet, 359, 57-61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07283-5 Grossberg, G. T. (2003). Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s dis- ease. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 3-6. Grunig, J. E. (1984). Managing public relations. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. Hennekens, C. H., & Buring, J. E. (1987). Epidemiology in medicine. Boston-Toronto: Little Brown and Company. Ishikawa, K. (1985). What is total quality control? The Japanese way. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Kahana, E., Young, R. F., Kerchir, K., & Kaczynski, R. (1993). Testing a symmetrical model of caregiving outcomes during recovery from heart attacks. Research on Aging, 15, 371-398. doi:10.1177/0164027593154001 Kettinger, W. J., & Lee, C. C. (2005). Zones of tolerance: Alternative scales for measuring information systems service quality. MIS Quar- terly, 29, 607-621. Marvardi, M., Mattioli, P., Spazzafumo, L., Mastriforti. R., Rinaldi, P., Polidori, M. C., & Mecocci, P. (2005). The caregiver burden invent- tory in evaluating the burden of caregivers of elderly demented pa- tients: Results from a multicenter study. Aging Clinical and Experi- mental Research, 17, 46-53. McBurney, D., & White, T. L. (2009). Research methods. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1981). Manual for the profile of the mood state. San Diego: Educational Testing Service. Miller, E. A., Allen, S. M., & Mor, V. (2009). Commentary: Navigating the labyrinth of long-term care: shoring up informal caregiving in a home and community-based world. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 21, 1-16. doi:10.1080/08959420802473474 Miller, E. A., Schneider, L. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2009b). Assessing the relationship between health utilities, quality of life, and health services use in Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriat- ric Psychiatry, 24, 96-105. doi:10.1002/gps.2160 Nijoboer, C., Tempelaar, R., & Sanderman, R. (1998). Cancer and care- giving: The impact on the caregivers health. Psychooncology, 7, 3- 13. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<3::AID-PON320>3.0. CO;2-5 Novak, M., & Guest, C. (1989). Caregiver response to Alzheimer’s disease. The International Journal of Aging and Human Develop- ment, 28, 67-79. doi:10.2190/4W02-HLMK-HAMJ-UTQP Parasuraman A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service qual- ity: Implications for further research. Journal of Marketing, 58, 111- 124. doi:10.2307/1252255 Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64, 12-40. Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist, 3, 583-594. doi:10.1093/geront/30.5.583 Prezza, M., & Principato, M. C. (2002). La rete e il sostegno sociale. In M. Prezza, & M. santinello (Eds.), Conoscere la comunità (pp. 193- 233). Bologna: Il Mulino. Sube, B., Rosalind, W., Nori, G., & Barry, J. G. (2010). The Stroud/ ADI Dementia Quality Framework: A cross-national population-le- vel framework for assessing the quality of life impacts of services and policies for people with dementia and their family carers. Inter- national Journal of Geria t r ic Psychiatry, 25, 249-257. doi:10.1002/gps.2330 Tamanza, G. (1998). La malattia del riconoscimento: L’Alzheimer, le relazioni familiari, il processo di cura. Milano: Unicopli. Tamanza, G. (2001). Anziani. Milano: Franco Angeli. Tanese, A., Negro, G., & Gramigna, A. (2003). La customer satisfac- tion nelle amministrazioni pubbliche. Valutare la qualità percepita dai cittadini. Cantieri-Analisi e strumenti per l’innovazione, I Manu- ali. Roma: Rubbettino. Taylor, S. E., Lichtman R. R, Wood, J. V., Bluming, A. Z., Dosik, G. M., & Leibowitz R. L. (1985). Illness related and treatment related factors in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. Cancer, 55, 2506-2513. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19850515)55:10<2506::AID-CNCR2820551 033>3.0.CO;2-0 Zanella, A., & Cerri, M. (2000). La misura di customer satisfaction: Qualche riflessione sulla scelta delle scale di punteggio. In AA.VV. Valutazione della qualità e customer satisfaction: Il ruolo della sta- tistica. Milano: Vita e Pensiero. Zanetti, O., Frisoni, G. B., Bianchetti, G., Tamanza, G., Cigoli, V. & Trabucchi, M. (1998). Depressive symptoms of Alzheimer caregivers are mainly due to personal rather than patient factors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13, 358-367. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199806)13:6<358::AID-GPS772>3.0. CO;2-J Zarit, S. H., & Toseland, R. W. (1989). Current and future direction in family caregiving research. Gerontologist, 29, 481-483. doi:10.1093/geront/29.4.481 Zimet, G., Dahlem, N., Zimet, S., & Farley, G. (1988). The multidi- mensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30-41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

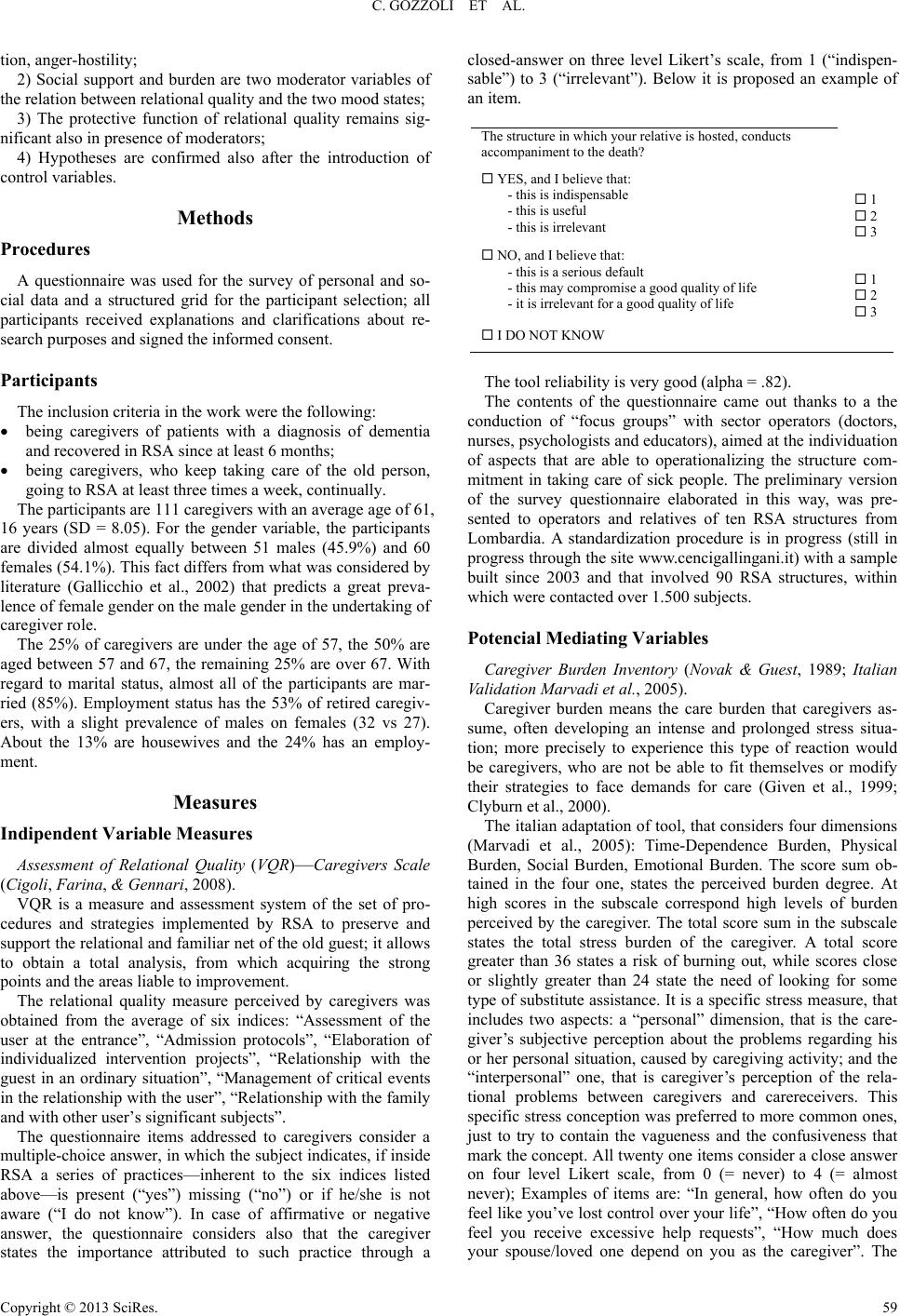

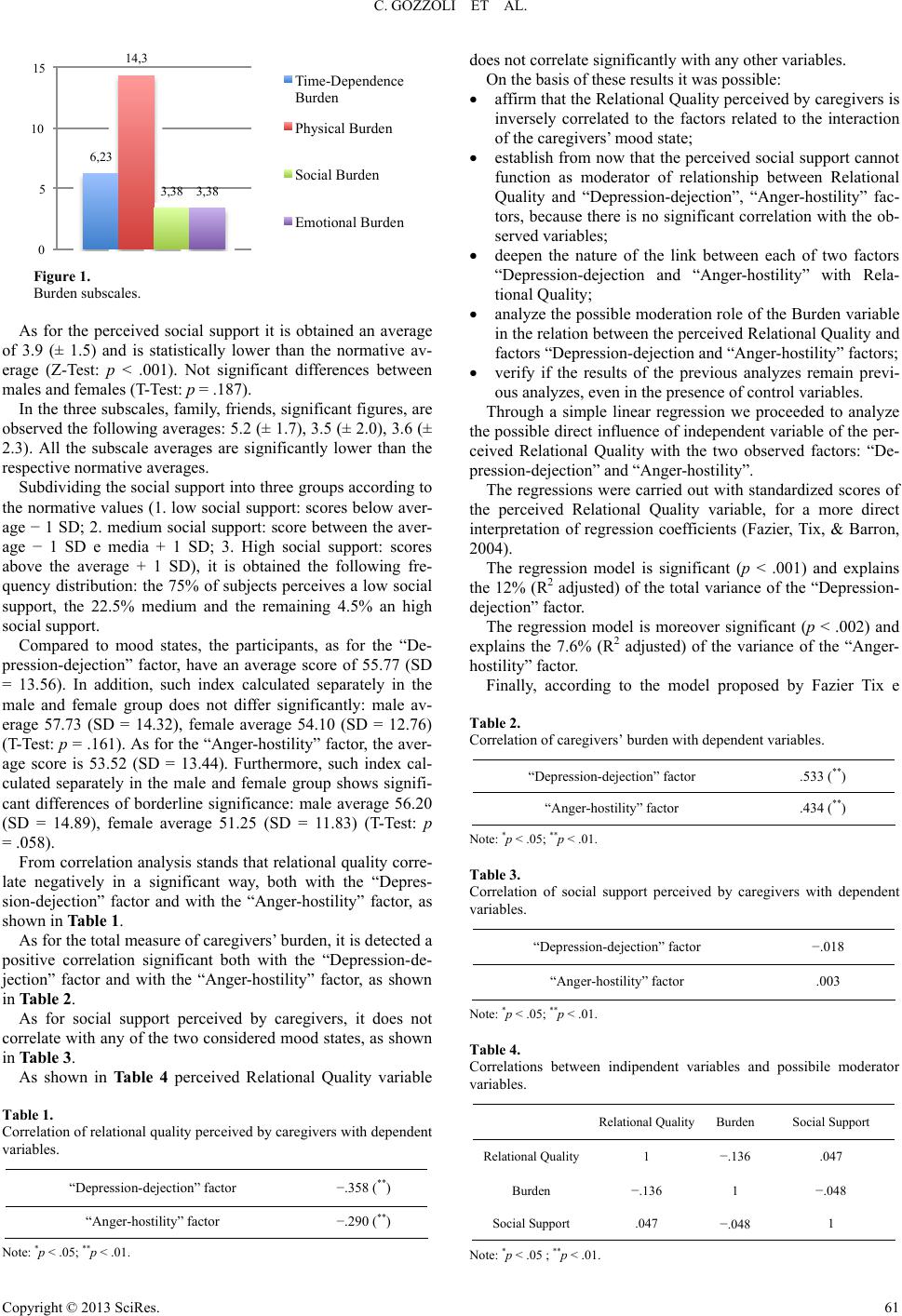

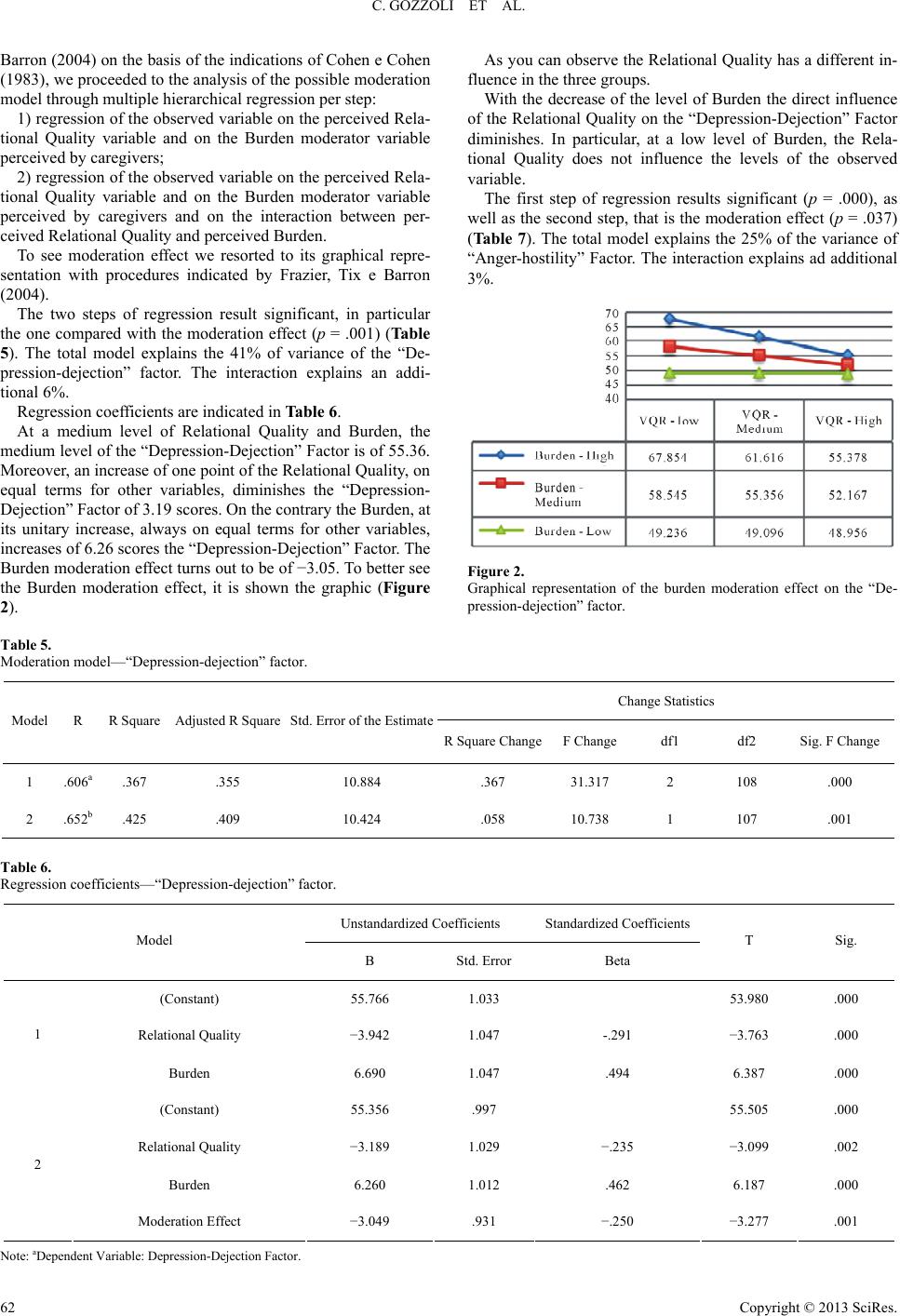

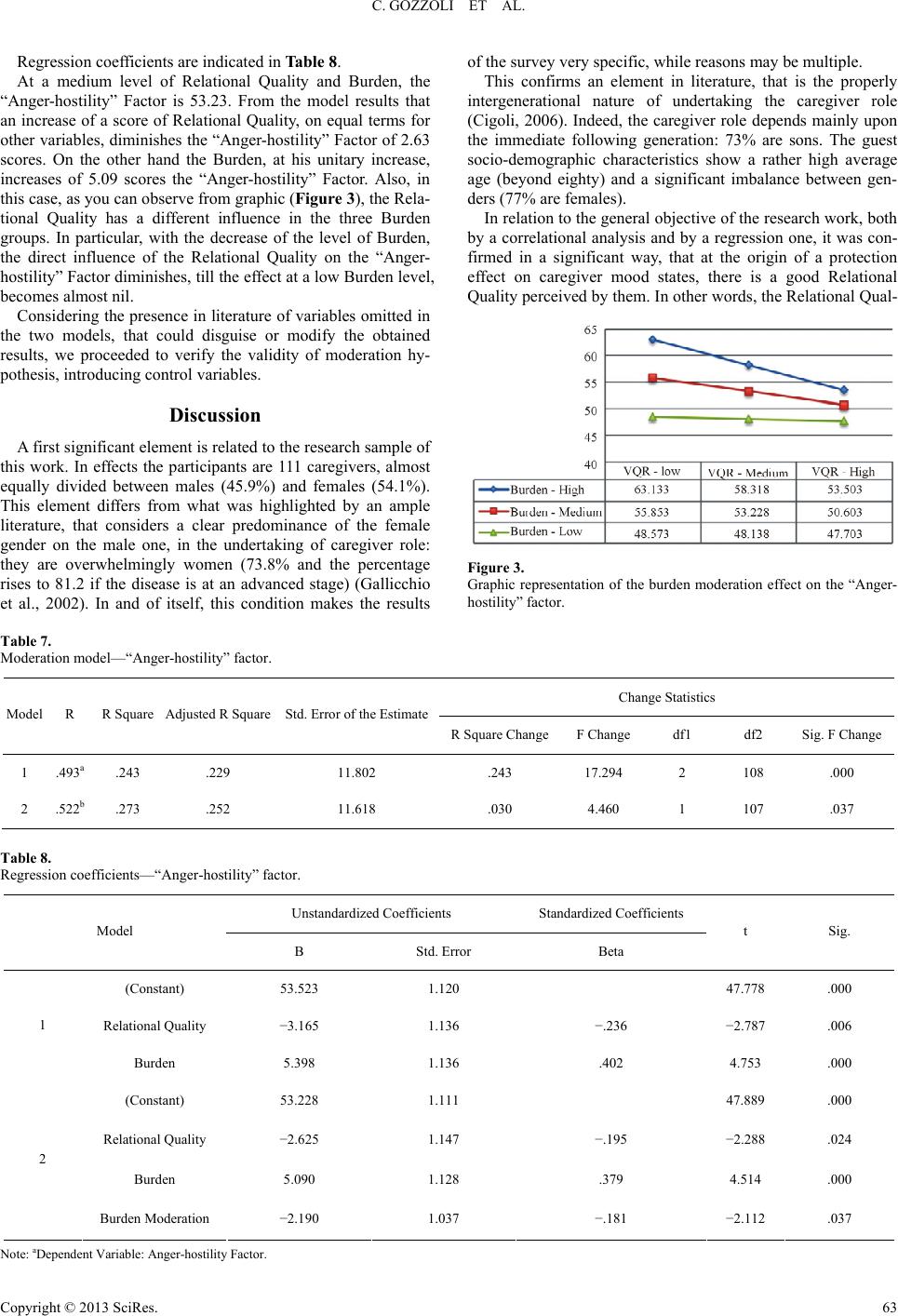

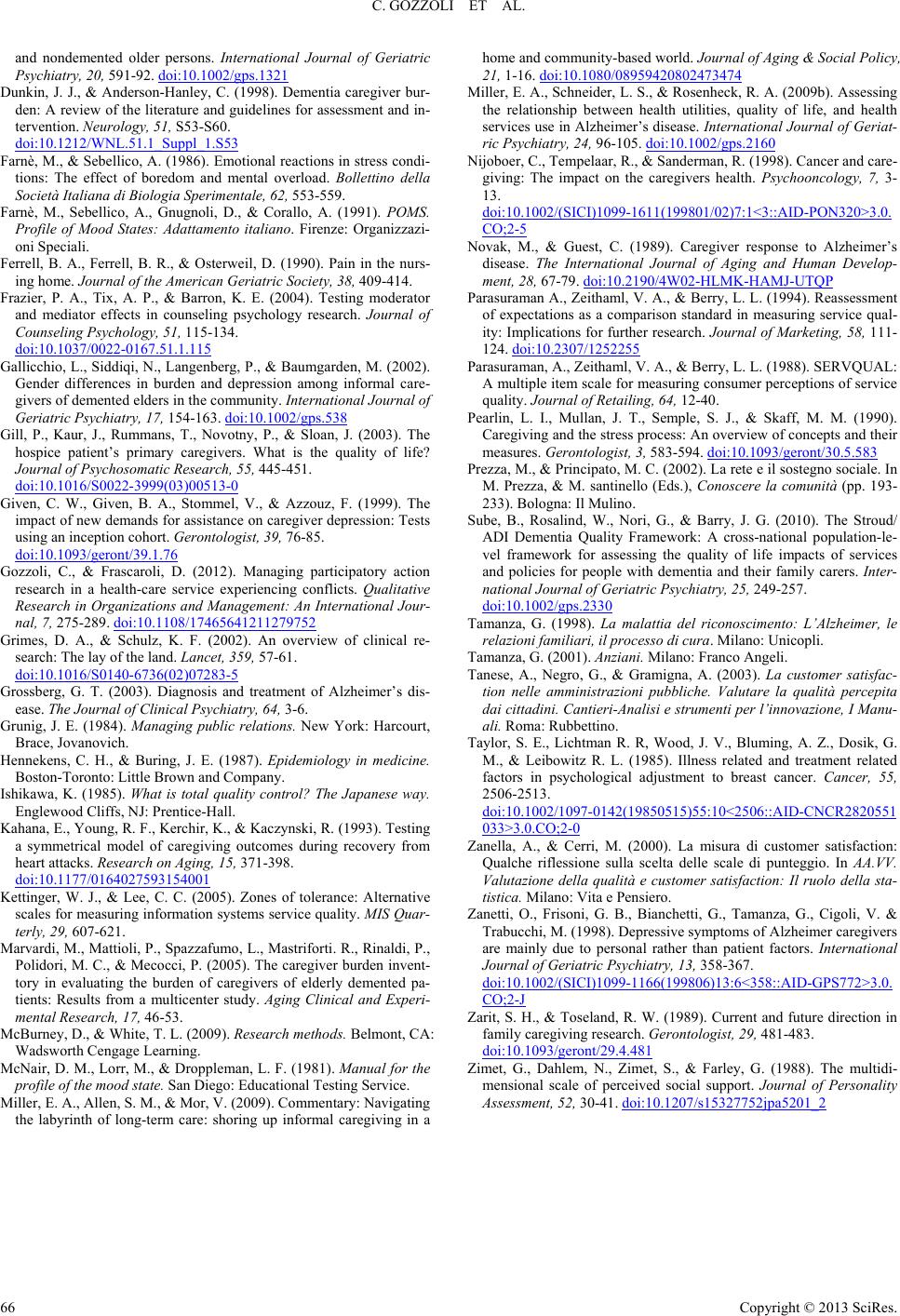

|