Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 85-92 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2013.32011 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 85 Healthcare Technology: A Domain of Inequality Suman Hazarika1, Akhil Ranjan Dutta2 1Department Radiology, International Hospital, Guwahati, India 2Department of Political S cience, Gauhati University, Guwahati, India Email: sumanhazarika@rediffmail.com, akhilranjangu@gmail.com Received February 6th, 2013; revised March 10th, 2013; accepted March 19th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Suman Hazarika, Akhil Ranjan Dutta. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The prevailing perception that technological development facilitates universal empowerment and tran- scends the social domains of discriminations is now challenged by comprehensive studies. Technology itself is a domain of inequality and it accentuates more inequality with technology gradually favoring the privileged sections and the societies. The healthcare technology, which otherwise could have brought miracle achievements in attaining universal health standards, however, has failed to do so due to the in- herent inequality in access to healthcare technology. The growing dominance of monopoly houses on healthcare technology and marginalization of indigenous health technology makes access to technology with a new domain of inequality. With comprehensive empirical data, the present paper investigates into this domain of inequality and argues that a move towards global well being demands a radical restructur- ing of the global domain of healthcare technology. Keywords: Antibiotics; Socioeconomic Status—SES; Prosthesis; Jaipur Foot; Heart Valve Introduction “Medicine arose out of the primal sympathy of man with man; out of the desire to help those in sorrow, need and sickness” (Osler, 1913). Since the era of modern medicine following discovery of an- tibiotics & vaccination, the health of people in general has un- dergone a sea change. Centre for Disease Control and Preven- tion (2013) has identified vaccination as the topper of the list that has impacted on public health. Centre for disease control estimates that in the 20th century about 25 years have been added to life expectancy for the US citizen. Though the accu- rate global data for understanding impact of medical or health- care technology is not readily available, United Nations reports suggest that life expectancy at birth for the world population rose from 48 years in 1950-1955 to 68 years in 2005-2010 (UN, 2012). The report illustrates the transition of different countries through phases of economic developments and the change in the death pattern. It has been seen that with increasing eco- nomic and social development, death from the type I cause (that primarily includes infectious disease) declines. In spite of continued efforts by global agencies, national governments and professional work groups of the benefit of healthcare technology are yet to touch the lives of millions of people across all the continents. Providing access to medicine and health technology has been a priority in the Millennium Development Goals (UN, 2001). There are government inter- ventions (Department for International Development, 2004) to promote dissipation of healthcare technology benefits, but there still lies an access gap for all sorts of health technologies not only medicines. The lack of access to advance diagnostic tech- niques, prosthesis or blood transfusion technology is rarely discussed if compared to concerns for medicines. Similarly most debate on healthcare technolog y access ends up discussing factors of cost and affordability, but the equally important problems of politics and administration, delivery, distribution and technology adoption remain somewhat neglected. Fundamental Theory Historically it was observed that people who are placed con- veniently at the socio-economic hierarchy stood a better chance at life to live longer. What devastated the world as killer disease has changed from cholera and bubonic plague in past centuries to death from cardiovascular accidents and cancer in present era, but the association of socioeconomic status (SES) factors with survival remains across the disease—thus the risk of disease type changes but the association of SES factors persist across the spectrum. To understand SES status factor one needs to consider three core elements-education level, employment & work, and eco- nomic state. The first of the factor education is responsible for knowledge and skill, values and behavior that will shape the structure of work opportunities. The second core element of SES factor is employment & work—a person in employment is paid, but a person doing productive work (like house wife) may not be paid. The employment or work can be categorized in a scale, higher ranked jobs confer more autonomy, economic return and happiness. Third core component of SES factor is economic well being that translates to household income, per- sonal earning, wealth or economic hardships. It is important to understand the impact of each of the core factors separately on health. Averaging out the SES factor while studying a health phenomenon might leave enough gap in knowledge, to make policy related intervention difficult. Effect of education on  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA health and health on education, effect of economic factor on health or health on economic factor and effect of employment or occupation on health and vice versa are not interchangeable propositions. In the United States of America, National Longitudinal Mortality Study (NLMS) is carried out under sponsorship of the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Aging, the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for the purpose of studying the effects of differentials in demographic and socio-economic characteristics on mortality. Confirmation of association of SES factor with mortality comes from National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Researchers have pointed out strong association of mortality with income and education lev- els. While income is mostly a changing variable across the years and education remains static in later part of an indivi- dual’s life, it is interesting to note that the factor of income & education compete with each other to influence ones chances of longer life (Sorlie, Paul, Eric, & Jacob, 1995) Link & Phelan proposed a fundamental cause theory that seeks to bridge association between SES and health outcome over a long time (Link & Phelan, 1995).The observations made in the theory stems from the fact that SES of an individual determines the access to important resources that allow the individual to avoid diseases and their consequences. SES dictates risk factors and disease outcomes that change over time. Thus in fundamental cause theory SES is seen as the basic factor to influence health, morbidity & mortality. The list of resources that need to sustain life is varied and includes wealth, knowledge, skills, power, and social connections. It has been seen over time that the infectious diseases that used to anni- hilate large populations have been somewhat controlled in the developed world by increased sanitation and various other public health measures. In the developed world the leading cause of death now includes heart diseases, stroke and cancer and now we can see that importance of factor like sanitation or drinking water on mortality and survival has decreased but the new factors like smoking, lifestyle have gained importance which again are dependent on SES. We can understand that controlling some disease shift our focus to newer diseases that gain importance and we get to know newer cause association mechanisms. Today when researchers will formulate newer technology or drugs to treat the new killers people in the higher level of SES strata will stand higher chances at survival as resources can be allocated for obtaining such benefit. Thus the historically evident observation remains that no matter what- ever emerges as new risk factor that effects population health at any given point of time those who are at a higher SES ground will tend to fare better and the social disparities in health remain. Empirical research has supported Fundamental cause theory for newer global epidemics of this century. One important study with cholesterol lowering drugs was undertaken to understand the socio-economic bias of utilizing newer interventions. Cholesterol is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease which is emerging as an important cause of mortality in the developing world. Chang et al (Chang & Lauderdale, 2009) used three sets of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data sets that included 1976-1980, 1988-1994, and 1999-2004. The researchers observed the blood cholesterol & Lipid level in an effort to understand the effect of new effective class of costly drugs (statins) that entered the healthcare market. The study used the poverty income ratio, that takes into account family’s income to its appropriate poverty threshold given family size and composition. In analyzing the differential pattern of cholesterol reduction, the statistics suggested that people with higher income scale have experienced a much larger decline in lipid levels than those at the lower end. For example, among men, LDL (low density lipoprotein) decreased by 20.6 units over this period for high-income persons (Poverty Income Ratio = 5), but by only 10.3 units for those at the poverty level (Poverty Income Ratio = 1). Hence, the decline experienced by the wealthy was nearly double than experienced by the poor. While it is important to note that average cholesterol levels declined during this period at all income level still there were significant disparities of gradients favoring the wealthy. In conclusion, Chang et al commented “...wealthy have disproportionately benefitted from the development of a technology to treat this new risk factor, which will likely extend to disparities in cardiovascular mortality and, ultimately, con- tribute to the maintenance of disparities in overall mortality”. Access to Healthcare Technology In a simplified nontechnical way we can define “Access” as one’s ability to obtain a product or service. So if we have to translate the meaning to health care access, it will mean people’s ability to get treated for diseases they have, or people’s ability to get services that provide them health and well being free of disease. Access is not to be understood as a simple matter of logistics to make a technology available or affordable to a population in question. The question of access is also related to social values, cultural bias, economic interests and prevailing political processes that govern the healthcare system. Access can be seen as a continuous process that involves a set of actors over a long period of time throughout different activities. Frost and Reich, has summarized the conception of Access on four “A”s: Architecture, Availability, Affordability, Adoption (Frost & Reich, 2009). Architecture involves the organizational structure that co- ordinates the next three “A”s to produce access. To make a technology or product available one need to consider manu- facturing, storage, distribution and delivery functions. Afforda- bility of a technology has multiple dimensions. Whether it is affordable to end users directly or whether it is affordable for the healthcare system acting for population or whether the technology needs to be affordable to a central government planning all are encompassed within the broad meaning of affordability. At all these levels one need to anticipate the fact that the product or service is not out of reach to the individual or society. Last dimension of access is Adoption that involves global and local levels. A technology needs to be accepted for use by the end users, so that a healthy demand is generated for its continued availability. Once the concept of access is defined, we may proceed to understand how the activities under each component of access translates a healthcare technology product or service to make a difference in disease outcome, or more generally speaking improving health. It is necessary to ensure that mere availability or use of a technology or product is insufficient, one has to ensure appropriate and right use of healthcare technology for the intended purpose, to have an impact over the population Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 86  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA health. While use of a particular technology for the intended purpose is desirable, one can not underestimate innovative users to find another use. It can not be assumed that non-intended newer use will conform to the code of healthcare benefit or patient safety. History of healthcare innovation is replete with examples of employing simple resources to achieve outstanding outcome. One example is Foley Balloon cathater that has the primary use of draining an obstructed urinary bladder. The sight of the cathater serving as tubing for passage of urine from inside the body to a urine collecting bag is all too familiar for any visitor to a hospital. Necessity and innovation has given the simple rubber tube its other uses like as a tubing to drain blood or fluid from chest, drainage of pus from internal body abscess or even as a effective Torniquet to tie around a limb to stop bleeding, so on. One interesting anecdote is transformation of Female condoms to fashion accessories (Steve, 2005). In Zimbabwe Female condoms were distributed by aid agencies, which costs 2 cents each. The condoms were obtained to make a profitable fashion accessories by cutting off the plastic, keeping the rubber ring for use as bangles. The rubber rings are colored and made in a pack of three could be sold for $2. While discussing the problem of access in their publication, Frost and Reich illustrated this case of technology adoption as a reminder to the difficulty arising out of unpredictable human behaviour, which lead to wastage of a product by some people and thereby starving some other people of the products benefit. The socioeconomic barrier is an important factor that gove- rns access to healthcare technology and its benefits. The differ- ential pace of diffusion of healthcare technology can also be attributed to problem of access, apart from level of income and education. It can be argued that a dual strategy of improving socioeconomic condition along with good governance to im- prove access to healthcare technology can deliver better results for population health. Following our orientation on fundamental cause theory and the concept of access and its components we intend to review some of the healthcare technologies for our further under- standing before finding an approach to solve the problem of unequal diffusion of healthcare technologies. Example 1: Prosthesis From the very beginning mankind probably pondered over the unfortunate loss of limb in hunting misadventures and acci- dents. Later with the formation of social groups the phenome- non of war probably claimed its fair share of limbs. In history of medicine the story of limb amputation and development of prosthesis paralleled each other. Its historical twists and turns paralleled the progress of civilization itself. Prostheses were developed for function, cosmetic appearance, and to provide a psychological sense of wholeness. These very patient needs have existed from the dawn of time till the present time. Even today modern healthcare technology innovations are directed towards development of newer devices like implantable joints, organs and devices for functional restoration like artificial lenses and pacemakers. In our discussion for the sake of sim- plicity we are taking the case of limb prosthesis and artificial heart valves (valve prosthesis). Limb Prosthesis In last two centuries industrial revolution and the world war brought about considerable advancement in prosthesis fuelled by money available to amputees and soldiers. With large num- ber of effected population it was right to expect a forced devel- opment in functional limb prosthetics. In the present world there are still large populations of amputees from landmine blasts, accidents or polio. Developing an appropriate prosthetic/orthotic care is challen- ging. Poonekar (Poonekar, 1992) identifies a list of prevailing factors affecting prosthetics and orthotics in India, but these could apply to much of the developing world. Apart from the socio-economic, cultural factors the researcher has identified other factors like climatic condition, local availability of tech- nology & material—which comes to the domain of access. Other researchers too comment on access issues of prosthesis from the view point of making it available where needed. Prop- erly constructing, fitting, aligning, and adjusting a prosthetic limb requires a high level of skill and despite the high demand for this expertise, there are very few training programs in low- income countries. The limited number of skilled person itself creates a problem of access to prosthesis. Studies by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that while the current supply of technicians falls short by approximately 40,000, it will take about 50 years to train just 18,000 more skilled pro- fessionals(Walsh & Wendy, 2005). Keeping aside the financial implications, researchers are looking to identify the factors and trends to promote an equi- table access to technology of prosthetics in the developing world. There are two dominant but often conflicting approaches to circumvent the problem of access to prosthesis. In the “top- down” approach of buying and implementing technology packages from the west, money is spent on procuring and dis- tributing the benefit. The other approach involves developing the simplistic traditional technology with local skill and mate- rial on a sustainable basis. Donor agencies all over would read- ily supply state of the art limbs to amputees of mass disaster. Whereas national governments in resource poor setting prefer to patronize the second approach in a more long term perspe- ctive. The success of Jaipur foot (Box 1), indigenously devel- oped in India with local expertise, material and a continuous interaction between manufacturer and the end users is a testi- mony to the second approach. This experiment needs an elabo- ration. While discussing antipersonnel mine blast victims rehabilita- tion it has been pointed out that access to medical facility, secu- rity, government policy & administration are very important limiting factors alongside the socioeconomic factors. Matsen in his study of Vietnamese amputee population has carried out a field survey and had encountered some interesting facts that highlight the difficult problem of access to prosthetic services, based on various governmental considerations (Mat- sen, 1999). In Vietnam various international agencies are pro- viding prosthetic services through the government. Like many developing countries savaged by wars in the twentieth century, Vietnamese suffer from undetonated mine fields. There are other (social) causes of limb losses like road traffic accidents too. The case study carried out by Matsen, to understand access to healthcare technology in the form of prosthesis showed that allotment of prosthesis was following a hierarchy. For receiving the benefit the favored people are North Vietnamese war heroes, followed by public officials, than the north Vietnamese veterans, and lastly the people who had amputated limb from Non War related injury or disease. Distribution of prosthetic part too Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 87  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA Jaipur foot is a familiar name for who live in the war zones of Afghanistan to Iraq, from Angola to Srilanka. This below knee prosthesis made with wood and rubber or aluminium and rubber has changed millions of life in the developing world. Lightness and mobility are its most attra ctive fea tures. Pe ople spen d close to $30 on a foot and wear it to run, cli mb trees and ri de bicycl es. Pr ice is one of the fact or fav ourin g the Jaipur Foot but the r eal appeal of the techn ology lies in the fact that it take s only 45 minutes to build and a few hours to fit on to the patient, and lasts for more than five years. Being developed by crafts man in a third world country, the technology is perfectly suited to the lifestyle needs of countries such as India and Afghanistan, where people sit, eat, sleep and pray on the floor. The cultural mismatch of western world prosthesis which came with a fitted shoe (poor people do not wear a shoe! Even if poor people have shoes, they do not wear it in ankle deep mud of paddy fields) that limited the person from squatting, crossed leg sitting was a nightmare. Pandit Ram Chandra Sharma is credited as the inventor and designer of the J aipur fo ot, when h e was o n a vi sit to SMS hosp ital to t each art as a therapy to polio effected children, in 1960. “Masterji” as he is widely known, tried to solve the problems faced by the young amputee with imported artificial limbs, by creating a limb locally from vulcanized rubber hinged to a wooden limb and a pro t o type Jaipur foot was born. Jaipur Foot has been continually innovated ever since its first devel- opment with active involvement of Masterji. Its essence has however remained: ease and speed of fabrication, lightness in weight, low cost and suitability for working people in the Third World. Now Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO)—is helping the crafts man to make a foot from Polyurethane’s (PU)—used by the space industry in their rockets and satellites. The se ne w gen erat ion Jai pur f oot a re unde rgoi ng field tr ials and laboratory tests. The new Jaipur foot is lighter and has improved upon its cosmetic appeal. Source: Good News India, Magazine (w eb source: 9th March 2013) Box 1. Local solution of global problem: Jaipur foot. followed a pattern of privileged geographic province. For in- stance, patients waited on average only 1.8 years, while in the province of Quang Tri patients waited nearly five times as long (average 8.9 years) before their first government-provided leg. This waiting period has a strong correlation with the rate at which government pensions are allotted to the patients of the province. These finding complements the perception that the equitable distribution of healthcare technology has many barri- ers beyond the principal barrier of SES, the problem of access based on prevailing political considerations, too needs to be addressed for a solution. Heart valve (valve rosthesis) While most of the rheumatic fever induced developing world heart disease has only limited access to heart valve replacement an estimated 275,000 - 370,000 elderly patient receive valve replacements in developed world (Zilla, Brink, Human, & Be- zuidenhout, 2008). The luxury of cardiac surgery is only avail- able to 8.1% of the Chinese and 6.9% of Indian population. However, given the pace of fast growing economies of some of these countries, it is predictable that they will soon have a high demand for prosthetic heart valves that are affordable and that address the specific needs of their mainly young rheumatic heart disease patients. It is expected that lack of socio economic progress makes outcome from heart valve surgery less accep- table owing to post operative complication of blood coagula- tions. In the post-operative period recipient of the prosthesis needs to be educated for continued monitoring visits, and com- pliance with anti-thrombolytic therapy. In developing countries these thrombo-embolic complications are abundantly multiplied due to lower socioeconomic state, mainly educational deficits. There is alternative technology of biological tissue valves which are not considered to be adequate for young patients of third world due to the fact that biological valves tend to degen- erate fast in younger people. The problem of access to health- care technology in this situation comes in many packets besides the problem of affordability that is attempted to be addressed by locally manufacturing heart valves. One of the problems with local manufacturing is that the technology may not be appro- priate in the intended situation, as the third world replicas are based on a first world objects meant for different set of patient, and at times for different indications. There is little incentive for the multinational companies to do active research in valve prosthesis where profit turn around time is too long from prod- uct design to sales turnover. The fact that most products will have a market in the low paying developing third world in itself undermines the issue considerably for profit seeking corpora- tions. People with valve disease in developing world will con- tinue to face the problem of access based primarily on their socioeconomic status. Unless research is undertaken to develop low cost affordable and effective solution, the gap between the people’s needs and MNC’s commitment will continue to widen. It is frustrating to note the fact that on one side people from threshold countries in need of a new concept of a truly long- lasting valve prosthesis is waiting in desperation and on the other hand elderly patient of first world are overwhelmed by hyped sales effort of long established standard products like coronary stents to keep the narrowed arteries of heart from collapsing. Example 2: Dialysis & Transplantation for ESRD Globally millions of people undergo various forms of treat- ment for end-stage renal (kidney) disease (ESRD). Though renal transplant carries a definitive treatment choice the access to such treatment is not uniform across the globe. There are various other forms of renal replacement therapy like haemo- dialysis and peritoneal dialysis that is offered across the globe. There are a number of national and international databases that provide valuable demographic and epidemiologic information on renal patients since the first report of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EDTA) was published in 1965. These databanks provide valuable data for researchers to under- stand various factors impacting the modality of renal replace- ment therapy. Apart from these databanks there are independent research reports that try to correlate choice of treatment moda- lity with various SES factor. Grasmann et al. (Grassmann, Gio- berge, Moeller, & Brown, 2005) published a research report in 2005, where an attempt was made to correlate financial fac- tors with modality of treatment. In this study, data from 122 nations were obtained for number of ESRD population who were into various forms of renal replacement therapy. Ta bl e 1 is reproduced from the study of Grasmann et al. At the end of 2004, some 1,783,000 people globally were undergoing treat- ment for ESRD. 77% were on dialysis and 23% were with functioning transplant. The table presents the fact that more or less 30 - 70 split in dialysis/transplant patients is usual for North America, Europe and the Middle East, while much less number of patient live with a functioning renal transplant in Asia, Latin America and Africa. Results for Japan are separated from the remainder of Asia due to the significant differences in the patient care infrastructure. Analysis of the study population suggested that economic factors impose restrictions to treatment in countries Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 88  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 89 Table 1. Global and regional overview of ESRD, dialysis and transplant patient numbers and prevalence values per million population at year-end 2004. (Source: Grassmann, A., Gioberge. S., Moeller, S., and Brown, G., ESRD patients in 2004: global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends, Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. (December 2005) 20(12): 2587-2593.) Patient numbers Prevalence values (pmp) ESRD Dialysis (HD + PD)Transplant ESRD Dialysis (HD + PD) Transplant 1,783,000 1,371,000 412,000 Global 280 215 65 492,000 337,000 154,000 North America 1505 1030 470 473,000 324,000 149,000 Europe 585 400 185 (387,000) (252,000) (135,000) (thereof EU) (850) (550) (295) 261,000 248,000 13,000 Japan 2045 1945 100 237,000 196,000 41,000 Asia (e x cluding Japan)70 60 10 205,000 170,000 35,000 Latin America 380 320 65 61,000 57,000 5000 Africa 70 65 5 54,000 39,000 15,000 Middle East 190 140 55 in which the GDP per capita is below a limiting value. In 47 of the 75 countries with the largest ESRD populations, the GDP per capita per annum is under US $10,000. It has been found that less than 10% of Indian end-stage re- nal disease patient receive renal replacement therapy, while up to 70% of those starting dialysis die or stop treatment, due to cost, within the first 3 months (Sakhuja, 2003). For end stage renal disease patient Kidney transplantation promises higher quality of life. But access to transplant facility is skewed in favor of the high SES population. Even in developed world, individuals from socially deprived areas are less likely to re- ceive a pre-emptive renal transplant, in other words to receive a kidney transplant prior to commencing dialysis, than those from affluent class (Roderick, Hollinshead, O’Donoghue, Matthews, Beard, Parker, & Snook, 2001). Similar observations on correlation between financial factors and access to treatment for ESRD were made in a study from Malayasia. In their study Lim et al. (Lim, Goh, Lim, Zaki, & Rozina, 2013) confirms distribution of private sector dialysis facility tend to converge in the economically developed areas where patients are able to afford its services while the public sector is expected to do exactly the opposite in accordance with its social equity mission. It was also noted even the charity sector’s service distribution seems to more closely resemble the private sector than the public sector in its allocation of dialysis. Researchers explained the behavior of charity sector by the operational constraints of such facility where they need to gen- erate part of the cost from paying patient to cross subsidize the indigent ones. While there is rising per capita income by 20 % (In 1997, 2606 RMB/month, and 3249 RMB/month in 2004), during this period the number of patient with access to dialysis treatment rose by 112%. It was found that there was increasing market share of private & charity sector from earlier combined 46% of 1997, to 2004 level of 65% while the earlier high utili- zation of government dialysis facility actually registered a 35% negative growth. Figure 1. Relationship of prevalence of dialysis patient with percapita income of the country (sour c e Rot te r et al.) The researcher states a clear linear relationship with eco- nomy of the country and the prevailing number of population per million on dialysis treatment. For end stage renal disease patient option of kidney tran- splantation is the best choice in terms of quality of life and survival. But across the low and middle income countries such desirable access level to renal transplantation is not easy. In most countries transplantation suffers from lack of infrastruc- ture, and post transplant survival depends critically on the af- fordability of immunosuppressive drugs, malnutrition and in- fectious disease, in particular tuberculosis (White, Chadban, Jan, & Chapman, 2008). Across the globe including the high income country have certain cultural bias towards benefit of organ do- nation. In Japan belief about what happens after death and cul- tural resistance to mutilating the body and the idea of impurity associated with a dead body mean that only 5% of dialysis pa- tient enlist for transplantation. Across the Muslim world brain death has also been a controversial issue leading to debates among Muslim religious clergy which finally led to a 1996 de- claration of the Islamic Organization of Medical Sciences al- To further stress the point of economic factors driving access to treatment in end stage renal disease we refer to Figure 1 that has been reproduced from Rotter et al. (Rotter, 2011).  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA lowing recovery of organs from brain-dead persons. In many countries or communities cultural bias towards organ donation may also be an important issue limiting access. As in case of India, gender inequality limits access to transplantation—For example, in India, transplants from living, related donors typi- cally go from female donors to male recipients (Sakhuja & Sud, 2003). In spite of resource poor environments problem of access to renal transplant has been circumvented by active policy pre- scriptions. Costa Rica is one example: in 2002, 78% of its RRT population had received transplants, among the highest propor- tion in the world. Costa Rica has doubled the number of pa- tients on hemodialysis, and has the highest number of kidney transplants per million population (pmp) in Latin America, with 20.63 transplants pmp in 2000, 27.25 transplants pmp in 2001, and 24.81 transplants pmp in 2002. This is attributed to a public health system which, covering 98% of the population, provides equitable access to RRT; and to high rates of living kidney do- nation (Cerdas, 2005). Following a study across 46 countries (population 1.25 billion) Caskey et al. (Caskey, Kramer, Elliott, Stel, Covic, Cu- sumano, Geue, MacLeod, Zwinderman, Stengel, & Jager, 2011) concluded that macroeconomic and service organization factors are considered to be more important, over population age and health indicators in case of renal replacement therapy. We shall conclude the case of RRT & Transplant by finally highlighting the four “A”s of Access. Affordability is definit ely a driver of technology diffusion in this example as all the stati- stics show, and we have no further observations. What needs to be stressed that Affordability alone is not the determinant, in cases of Japan or the Muslim world adaptation of the trans- plantation technology has nothing to do with cost of treatment but is related to a deep rooted belief system, which often guide many decisions in technology diffusion. Adapting to a particu- lar technology has cultural elements in it. It is the culture and religious belief that may determine availability of organ from dead person, and even if the infrastructure is built benefit of transplantation will be unutilized for lack of availability of do- nated organ. Architecture component of the access phenomenon embeds in itself the care delivery system, the health policy and the political will of the government—Costarica is a good ex- ample to look at where their effective healthcare system in- cludes 98% of the population to give one of the best chances with renal replacement therapy comparable to the High income countries. The ethical & legal confusion surrounding organ donation, the case of benefit for the donor and the role of the for profit third party needs to streamlined in the developing world to build up a system of equitable access to transplantation. Providing Healthcare Technology in Resource Poor Setting Considering the view that continued progress of healthcare technology increases inequality by restricting access of techno- logy to the poorer people one arrives at a difficult juncture to choose between overall progress of medicine and increasing disparity of health status of people. To simplify—the choice is between vertical development in technology driven healthcare vs reducing inequality of health. Phelan et al (Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010) suggest a dual agenda of perusing improve- ment of healthcare technology and innovation without further widening the gap of inequality. In their opinion reducing resource inequality will go a long way to reduced effect of SES factors over health. The argument is that people use their knowledge, money, power, prestige, and social connections to gain a health advantage, and thereby keep the gradient active. As a matter of policy intervention if we redistribute resources in the population so as to reduce the degree of resource inequality, inequalities in health should also decrease. Reducing resource inequality is at the heart of political agenda of many doctrines but the outcome of all such beliefs are in itself unequal. As a corollary to Fundamental cause theory, one may con- clude that designing policy interventions that effect population irrespective of resource gradient will reduce health disparity. Universal programme of immunization, Global eradication pro- gramme for Small pox can be cited as successful policy inter- vention which serve entire population with little regard to SES barrier. More examples can be manufacturing of automobiles compulsorily with air bags as opposed to an option (as preva- lent in many developing countries), adding Iodine to edible salt to prevent thyroid disease, Adding nutrients to edible oils like (Vitamins) rather than recommending balance diet etc. In each example, the former solution does not give an advantage to those with greater resources, because individual resources are unrelated and irrelevant to benefiting from the i nt er ve nt io n. The problem of health technology access in poor countries has been researched by many groups. One notable research by Reich et al. (Reich & Frost, 2010) , titled “Research Studies for Promoting Access to Health Technologies in Poor Countries” comes out with several recommendations for increasing access to heath technologies in resource poor setting, we shall briefly discuss their relevance. The study is based on the case histories of technologies. These observations are made on process of creating access and the role of applied research studies that are needed to design an Access Plan. The first observation by Reich et al is “Developing a safe and effective technology is neces- sary but not sufficient for ensuring technology access and health improvement”. Developments in the laboratory has to find its way through the regulatory & distribution web to the end users. The technology availability and adoption part is equally important. The experience with the contraceptive— Norplant is cited as the complexity of the environment of tech- nology delivery. Norplant was a hormone releasing dermal implant that is surgically put under ones’ skin was developed by the Population Council (a non profit body). The technology was found to be highly efficient in clinical trials, and it demon- strated a high level of safety. By 1996, more than five million implants had been inserted worldwide. But Norplant’s contin- ued use suffered set back in the field. Apart from affordability the major problems faced were related to health systems capa- bility to provide expert service of implanting as well as remov- ing the device. The device suffered adoption hurdles by end users and finally the success story ended with removal of Nor- plant from the market in 2002. The innovators and developers of technology can not expect that developing a good device or technology will guarantee success. Many problems exist with access of technology in resource poor setting, one has to under- stand the limitations of healthcare system’s capability and fac- tors that control end users acceptance of technology. Develop- ing world situations are very different from the developed world where most technologies get designed. Norplant, being a new implant technology, required both insertion and removal by a trained provider. The training provided to the care delivery Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 90  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA system of developing world health system was not deep or comprehensive enough. As a result, many health professionals were not well trained on removal techniques, and these training shortfalls led to later difficulties with implant removals. There were still other problems with Norplant that involved informa- tion dissemination to users and the issue of counseling to make it an informed choice. We are coming to another finding of Reich et al where the importance of end users preference of technology is illustrated by a case. The case illustrates the role of end users choice on diffusion of technology. Using a female condom was seen as a brilliant idea of empowering women, but enthusiasm for the device died off soon. It was seen by many women as a large bulky device to be put inside, they were also prone to slippage during coital movement. The initial developers of the first gen- eration of female condoms did not adequately take into account the perspective of end-users. These problems can be addressed and supportive counselors might help women with practice sessions. It was soon discovered that women were not very comfortable with t he idea of some awkward sessions of practice to use the condom in a proper & right way. The result of end users rejection is effected in the sales figure of the product , by 2004, approximately 12.2 million units were sold per year, rep- resenting only 0.1 - 0.2 per cent of the number of male con- doms sold worldwide. “A”s a corrective measure, developers are now taking user input to make new generation product which are more aesthetically right & inexpensive—to make the technology more acceptable. Healthcare technology can also be viewed as a demand sup- ply equation, while demand for good technology is never a problem one need to consider at least two supply side issue to ensure appropriate resolution of the access gap. There is a prob- lem related to supply side that too can limit access to healthcare technology. The first supply side problem is forecasting the need—which means technology providers or sellers enter a developing countries market without appropriate knowledge of market size and quality. This leads to either oversupply—un- dersupply imbalances and the accessibility of product suffers. Oversupply to a small region cuts off much needed supply to another region where demand exists. Forecasting of health need and a global agency to address these market issues can solve this problem. Another issue that crops up with medicines or technology products in developing world is that there being no effort at health technology assessment, the government gets confused with too many products competing for the same need. Most developing world countries can summon limited capacity to understand the need gap analysis for competing technology. The world health organization have attempted to address the issue by providing updated resource in a website to help pro- curement decisions (“Sources and Prices” document) for ma- laria products. Reducing information asymmetries, by regularly dis- seminating updated information to producers and potential purchasers, can contribute heavily to bridge access gap. Conclusion While SES is cited as a blanket term for most important cause of mortality, from a more inclusive viewpoint to design policy intervention which does not seem right. Not only SES factor affect mortality of populations, geography and ethnicity as well have its claim. SES that includes income, education, employment, social hierarchy needs to be dissected further to develop policy intervention as for each component policy might have to be specifically different. The most common perspective of redistribution of wealth amongst citizen, increasing level of income and eliminating gradient of income might not guarantee health improvement. This approach by itself is insufficient and what we need to respect is the problem of access to health care. It is true that increased level of income will change the mortality pattern or causes of mortality but it can not be guaranteed that without a simultaneous level of improvement in care delivery system, access to facilities big changes will be seen. Redistribution of income or raising earning will be effective only if health is determined chiefly by income or by something determined by income. In preceding sections we have seen apart from issue of income, healthcare technology usage is shaped by various socio-cultural and political factors of access. It must be debated whether continuing to increase income in the poorer people will progressively increase health outcome or not. Resources like wealth if accumulated is not allocated only to healthcare needs, nutrition or sanitation—resources also get spent on various other items that will have no direct positive effect on health. However, there is a general agreement that low income, lack of education, social exclusion need to be addressed for improved healthcare outcome to all. In our opinion these SES factors can be assigned a higher place, but there still are factors down the line-healthcare delivery system, technology development and promotion, technology adoption which also need to be addressed. If the downstream factors of technology access remain unchanged, improving upstream socioeconomic factors will be ineffective. We take the liberty to quote Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen (Sen, 2001), to end this discussion. “Health equity has many aspects, and is best seen as a multidimensional concept. It includes concerns about achievement of health and the capability to achieve good health, not just the distribution of healthcare. But it also includes the fairness of processes and thus must attach importance to non discrimination in the delivery of healthcare. Furthermore, an adequate engagement with health equity also requires that the considerations of health be integrated with broader issues of social justice and overall equity, paying adequate attention to the versatility of resources and the diverse reach and impact of different social arrangements.” Acknowledgements The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Ms Atri Baruah, for manuscript preparation of this article. Valuable intellectual inputs from Dr. Abhijit Hazarika, is also being acknowledged. REFERENCES Caskey, F. J., Kramer, A., Elliott, R. F., Stel, V. S., Covic, A., Cusu- mano A, Geue C., MacLeod, A. M., Zwinderman, A. H., Stengel, B., & Jager, K. J. (2011). Global variation in renal replacement therapy for end-stage. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 26, 1-7 Cerdas, M. (2005). Chronic kidney disease in Costa Rica. Kidney In- ternational Supple ments, 68, 31-33. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09705.x Chang, V. W., & Lauderdale, D. S. (2009). Fundamental cause theory, technological innovation, and health disparities: The case of cholesterol in the era of statins. Journal of Health and Social Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 91  S. HAZARIKA, A. R. DUTTA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 92 Behavior, 50, 245. Department for International Development (2004). Increasing access to essential medicines in the developing world: UK government policy and plans. London: DFID. Frost, L. J., & Reich, M. R. (2009). Creating access to health technologies in poor countries. Health Affairs, 8, 962-973. Good News India Magazine, 2 013. http://www.goodnewsindia.com/index.php/magazine/story/jaipur-foo t/P4/ Grassmann, A., Gioberge, S., Moeller, S., & Brown, G. (2005). ESRD patients in 2004: Global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrology Dialysis Transplant- ation, 20, 2587-2593. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi159 Lim, T. O., Goh, A., Lim, Y. N., Zaki, M., & Rozina, G. (2013). Ine- quality in distribution of dialysis resources: A comparison between providers. http://www.crc.gov.my/documents/posterDialysisInequality.pdf Link, B. G., & Jo, P. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Heal th and S oci al Behavior, 35, 80-94. doi:10.2307/2626958 Matsen, S. L. (1999). A closer look at amputees in Vietnam: A field survey of Vietnamese using prostheses. Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 23, 93-101. http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3109/03093649909071619 Osler, W. (1913). Chapter 1, Evolution of modern medicine, a series of lecture delivered at Yale University. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1566/1566-h/1566-h.htm#2H_INTR Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Tehranifar, P. (2012). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence and pol- icy implications. Journal of Healt h and Social Behavior, 51, S28. doi:10.1177/0022146510383498 Poonekar, R., (1992). Prosthetics and orthotics in India. In: Report of a research planning conference—Prosthetic and orthotic research for the twenty-first century. Bethsheda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Reich, M. R., & Frost, L. J. (2010). Research studies for promoting access to health technologies in poor countries, TDR consultative meeting on implementation research for access and delivery of new and improved tools, strategies, and interventions for the control of diseases of poverty. Kam pala. Roderick, P., Hollinshead, J., O’Donoghue, D., Matthews, B. Beard., C, Parker, S, & Snook, M. (2011). Health inequalities and chronic kid- ney disease in adults. www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/document.php?o=465 Rotter, R. C. (2001). The cost barrier of renal replacement therapy and peritoneal dialysis in the developing world. Peritoneal dialysis Inter- national, 21, S314-S 3 17. Sakhuja, V., & Sud, K. (2003). End-stage renal disease in India and Pakistan: Burden of disease and management issues. Kidney Interna- tional Supplements, 63, 115-118. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.24.x Sen, A. K. (2001). Why health equity? York: International Health Economics Association. Sorlie, P. D., Backlund, E., & Keller, J. B. (1995). US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: The national lon- gitudinal mortality study. American Journal of public health, 85, 949. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.7.949 Steve, V. (2005). Zimbabweans make condom bangles. BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4250789.stm Centre for Disease Control (2013). Ten great public health achievement in 20th century. http://www.cdc.gov/about/history/tengpha.htm United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Popula- tion Division (2012). Changing levels and trends in mortality: The role of patterns of death by cause. United Nations publication, Copyright © United Nations 2012 . http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/levelsandtrendsinmo rtality/Changing%20levels%20and%20trends%20in%20mortality.p df. United Nations (2001). Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations millennium declaration, report of the secretary gen- eral. New York: United Nations Gener al Assembly. Walsh, N. E., & Walsh, W. S. (2005). Rehabilitation of landmine vic- tims—The ultimate challenge 2003. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/81/9/en/Walsh.pdf White, L. S. ,Chadban, S. J., Jan, S., Chapman, J. R., & Cass, A. (2008). How can we achieve global equity in provision of renal replacement therapy? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86. Zilla, P., Brink, J., Human P., & Bezuidenhout, D. (2008) Leading opinion prosthetic heart valves: Catering for the few. Biomaterials, 29, 385-406. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.033

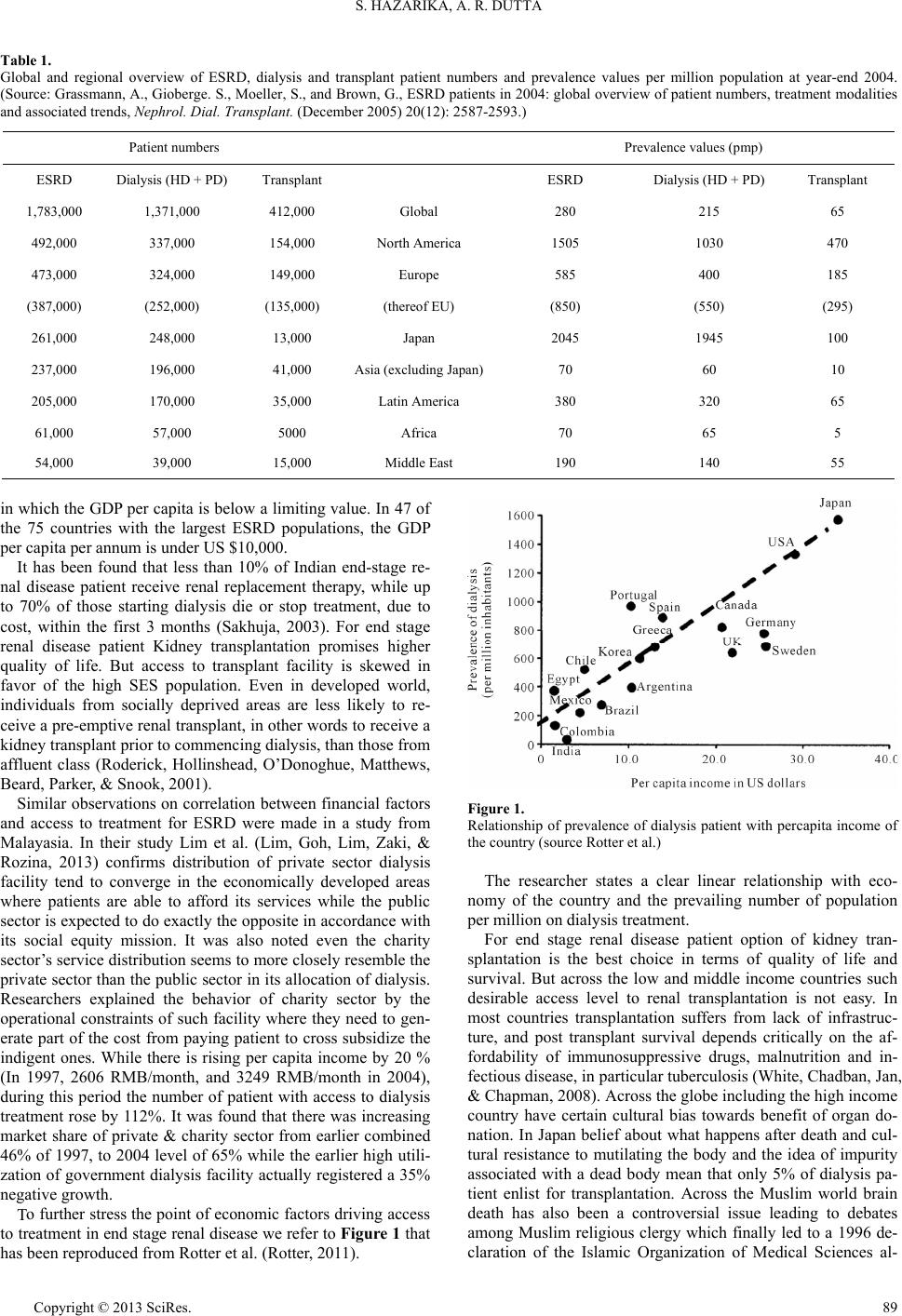

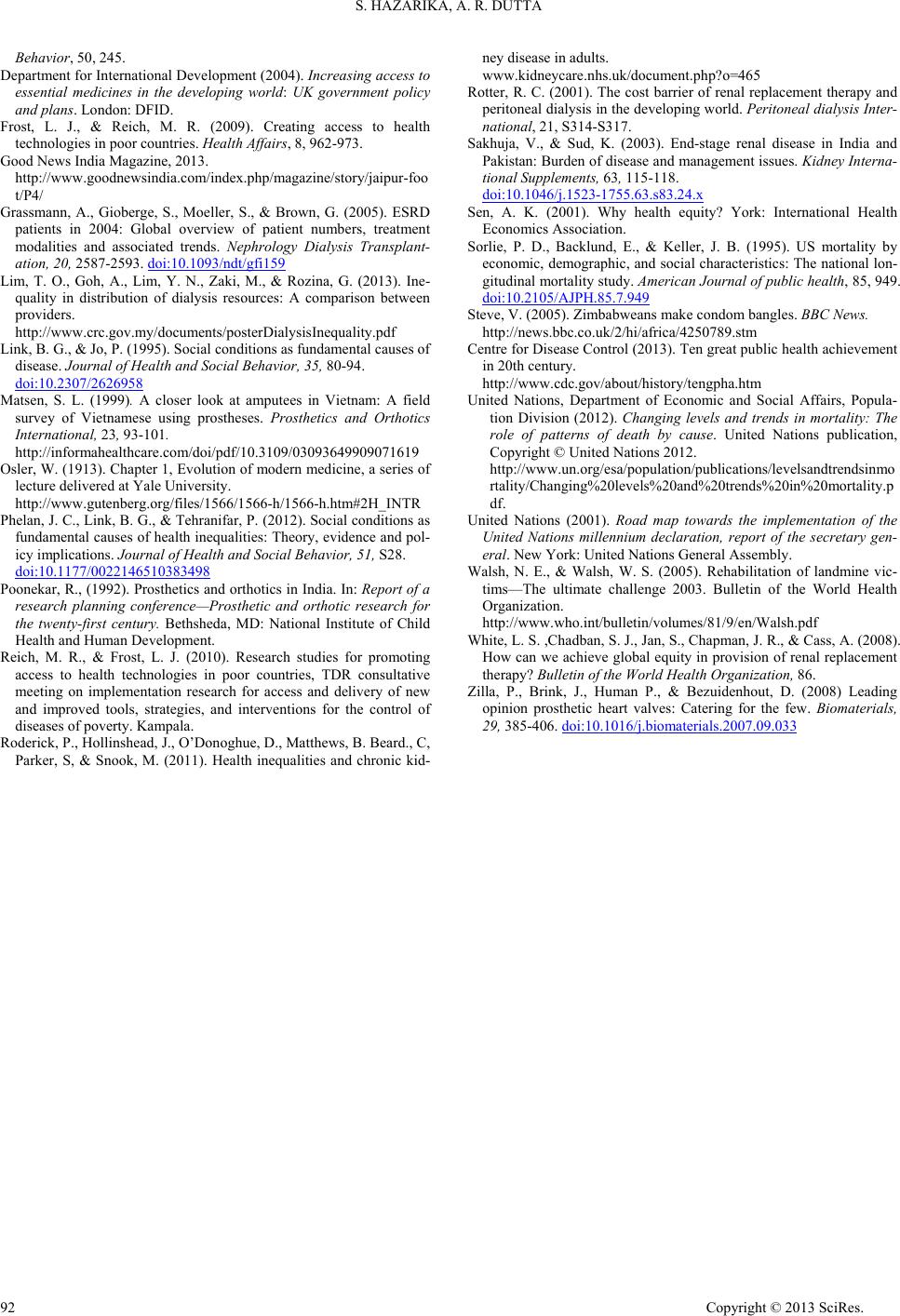

|