Technology and Investment

Vol.3 No.1(2012), Article ID:17455,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ti.2012.31003

Privacy Negotiation in Socio-Technical Systems

1Systems Engineering, IBM, Atlanta, USA

2Systems Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, USA

Email: mr@us.ibm.com

Received October 30, 2011; revised November 30, 2011; accepted December 7, 2011

Keywords: Privacy; Socio-Technical System; Framework; Privacy Framework; Negotiating Protocol; Web Services

ABSTRACT

A socio-technical system (STS) is an approach to complex organizational work design that recognizes the interaction between people and technology in workplaces. The term also refers to the interaction between society’s complex infrastructures and human behavior. In this sense, society itself, and most of its substructures, are complex socio-technical systems. This paper addresses a class of socio-technical systems, represented by web services in a number of domains and attempts to understand the possibility of empowering the web users and consumers to have a say in the development of privacy agreements. This paper examines the likelihood of the web users and consumers leveraging such a capability, should it exist. This should improve the way privacy agreements are handled that benefits both the service providers and the web users.

1. Introduction

A socio-technical system is defined as a mixture of people and technology. Depending upon what the system is addressing, it can become very complex. The actors in a STS context diagram could include hardware elements, software elements, actual physical surroundings, people, procedures, laws & regulations, data sources and data structures. It is configurable meaning that particular components in the STS can change or adjust in response to new requirements over time. For instance, an e-commerce website may introduce payments by PayPal in addition to a credit card by changing the way customers can make payments. But this change may also be reflected in changes in procedure (e.g. criterion for accepting from PayPal) and people (credit history).

The commonly used web services represent a class of socio-technical system that modern society has become increasingly dependent on. The proliferation of such web services, along with the increase in consumer awareness regarding data privacy and corresponding increases in regulatory and legal requirements for personal privacy have resulted in a heightened focus on the need to protect the personal privacy of web service users. While millions of web users leverage web services, a cohesive approach to tackle data privacy has not kept pace with this usage.

In the following sections, this paper will examine the elements of the STS associated with e-commerce transactions including the web consumer, the service provider, and the web services themselves. This is the first in the series of three papers examining the aspects of the privacy negotiation STS and ways to improve how the system operates.

This paper is organized in the following sections: Section 2 is a discussion on web users & privacy. Section 3 discusses the concept of privacy negotiation. Section 4 describes a model for privacy constraints negotiation. Section 5 includes conclusions and future work.

Literature Review

In the recent Web services research area, there are increasing discussions about automated privacy technologies for supporting privacy data of web user. For example, Yee and Korba’s research [1] (“Privacy Policy Compliance for Web Services”) focuses on privacy compliance of web services, the primary research examines privacy legislation to derive requirements for privacy compliance systems. This research proposes architecture for a privacy policy compliance system that satisfies the requirements and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed architecture. The research further discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the architecture for Privacy Policy Compliance Systems (PPCS). Wei Xu [2] introduced a framework that addresses consumer privacy concerns in the context of highly customizable composite Web services. Wei’s approach is based on certain automated techniques to check for compliance of consumer privacy policies to realize customizable privacy conscious composite services. In this framework, privacy obligations are respected when the code for the service is executed.

Carminati’s [3] design proposes a model titled publish-find-bind. In this model, the approach is based on service requestors discovering the published web services by the service creators. Privacy control measures are concerned with what happens to data after individuals have released it to organizations for particular purposes.

With each of these solutions is the absence of a trusted third party within their web services architecture. While the reviewed studies do include a model or architecture, this paper proposes a unique model that includes a third party in the architecture that can broker a negotiated privacy agreement between the web user and the service provider. None of the other related research addresses the privacy aspect of an e-commerce transaction. The proposed framework addresses the protection of privacy information in a harmonized e-commerce transaction. Applying a third party approach to the Generic Framework model makes the current work unique in comparison to reviewed research studies. This current framework proposal may lead to a new type of e-commerce on the Internet, where in service providers are segregated on the basis of their privacy data handling.

In addition, there is no indication that any of the principle researchers cited below focused on protecting the consumer’s privacy data rather than the “sale” itself. This research has more focus on protecting the consumer’s privacy data rather than the “sale” itself. It promotes a harmonized framework to protect the privacy data, obviating the service provider from protecting the privacy data.

2. Web Users & Privacy

As Web services become more prevalent in SOA based applications, the protection of privacy data of web service users is becoming an increasingly important concern. Lack of awareness on the web user’s side gives rise to monopolistic attitudes on behalf of service providers regarding how to treat web user privacy data. Two-thirds of the people surveyed by the UK privacy watchdog (UK Information Commissioner’s Office) organization want marketing opt-outs to be clearer, while 62% want a clearer explanation of how personal information will actually be used. The survey found that 71% did not read or understand privacy policies [4]. When the web users are not serious or care about their privacy data, there is little incentive for the service provider to tighten up privacy policies.

In the prevailing state of web services, privacy constraints and the associated agreement definitions is the responsibility of the service provider. The web user is limited to either accepting or declining this agreement. This is reflected in Figure 1.

This current environment offers us the opportunity to consider the following questions:

Figure 1. Privacy agreement by a service provider.

• Should the web user have an ability to negotiate the privacy agreement with the service provider?

• Should such ability exist, will it help get web service users and consumers to care more about their privacy and engage in the negotiating process?

• Is it possible to develop a generic framework to facilitate the above?

Figure 1 is an example of a typical privacy agreement provided by the service provider. Choices for the web user are limited to either “Accept” or “Decline”. This indicates the upper hand the service provider has in dictating the privacy terms.

3. Privacy Negotiation

3.1. Need for the Web Users to Negotiate

Before proposing any new privacy framework, let’s examine the following: “Is there a need for a web user to read the privacy terms presented in the privacy agreement by the service provider?” Currently, it is the service provider who provides the terms of the privacy agreement including how privacy data of the web consumer is managed. However, these service providers of trust are not foolproof as shown below:

Example 1: Facebook has, in two separate instances, significantly abused the trust of its members by sharing personal information unilaterally without letting the members know in advance [5]. First, when Facebook started providing updates about changes in member profiles, and second, when it broadcasted members’ purchases on other websites to their friends. Facebook is not alone in abusing the members’ personal privacy data [6].

Example 2: ChoicePoint, a Georgia-based Company, sells information in three markets-insurance, business and government, and marketing. According to a 2010 quarterly statement filed at the Security and Exchange Commission, ChoicePoint sells: “claims history data, motor vehicle records, police records, credit information and modeling services, employment background screenings and drug testing administration services, public record searches, vital record services, credential verification, due diligence information, Uniform Commercial Code searches and filings, DNA identification services, authentication services and people and shareholder locator information searches, print fulfillment, database and campaign management services etc.” [7].

An April 13, 2001 article in the Wall Street Journal reported that profiling company ChoicePoint provided personal information to at least thirty-five government agencies [5]. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is conducting an investigation of ChoicePoint on the complaint of giving businesses, private investigators, and law enforcement access to data that previously had been subjected to Fair Information Practices. In February 2005, ChoicePoint announced that the company sold personal information of at least 145,000 Americans to a criminal ring engaged in identity theft. California police have reported that the criminals used the ChoicePoint data to make unauthorized address changes on at least 750 people, and investigators believe that personal private information of up to 400,000 people in the United States may have been compromised [8].

Example 3: On February 20th, 2009, one of the largest payment card transaction processing companies in the United States reported a security breach. Information about the incident emerged slowly and few realized the magnitude and extent of the resulting impact. The final tallies proved shocking: over 100 million card accounts and 100,000 merchants impacted. The company’s stock plunged by 75 percent within six weeks. Stunning as it may be, this incident is merely one in a growing trend of evermore sophisticated, continually ongoing data compromises [9]. These are not one time data breaches either. Data breaches happen more often than reported in the press. With the advent of globalization, number of data breaches globally is increasing and global breaches are not systematically reported as they are in the US. Table 1 provides a partial list of all the data breaches in 2007. What these incidents indicate is that the privacy agreements provided by the service providers are not being strictly enforced either by accident or by negligence.

As socio-technical systems networks evolve into the next generation single window of communication channels for the vast majority of netizens, it is highly likely that users will become more sophisticated about demanding control of their personal information.

A 2009 survey conducted by Ponemon Institute shows that organizations spent an average of $6.6 million per incident and more than $200 per compromised record

Table 1. Partial list of data breaches in 2005.

[10]. According to Privacy Rights Clearinghouse website 542,214,290 data records were breached from 2711 data beaches made public since 2005 [11]. These incidents highlight the dangers of putting personal sensitive data in the hands of profit-making business.

3.2. Motivation for the Service Provider to Negotiate

In the prevailing state of web services, privacy constraints and the associated agreement is provided by the service provider. What is covered in the agreement is at the discretion of the service provider very often wrapped in language hard to understand by the user. It may appear that the service provider has little motivation to participate in the privacy negotiation with the web user. It is not only beneficial for the service provider; in reality it is in their best interests to consider a negotiation process. Privacy negotiations present the opportunity to develop a more systematic approach for handling web users’ privacy data on the web. Using privacy constraints negotiation, certified privacy practices can be represented in the form of digital credentials or a predefined framework that can be disclosed in response to user policies that require certain privacy practice guarantees. By automating the privacy negotiation practices in a framework approach provides the service provider to commit to certain privacy practices that could lessen the privacy liabilities on data.

4. Privacy Constraints Negotiation

4.1. Privacy Negotiations between Service Users and Web Users

The negotiation itself can be real-time, online transactions going and back forth until an agreement is reached. The negotiation sequence is depicted in the Figure 2. The trigger point for the negotiation starts when a privacy agreement is displayed by the service provider. The web user can further negotiate on the terms provided in the privacy agreement presented. For example, the web user can negotiate to restrict the service provider to keep credit card data for no more than 20 days. The service

Figure 2. Privacy negotiation between a service provider and web user.

provider, in turn, can counter this to extend the credit card retention period to 30 days citing a regulatory requirement.

When a privacy agreement P contains sensitive information like Pa, Pb … Pn, where, P1...n are privacy terms such as credit card, SSN, Home address etc., then P itself requires a trusted protection in the form of an agreement for access to P. For example, a client interacting with an unfamiliar web service provider may request to see the exact privacy terms on Pa, Pb that attest to the server’s handling of private information. This situation requires that trust be established through mutual negotiation on individual privacy constraints gradually leading to an agreed upon P, so that sensitive credentials are not disclosed to anyone outside of the defined P.

In the Figure 2, the service provider first throws the privacy agreement at the web user. The web user then chooses to negotiate the privacy terms provided in the privacy agreement. In theory, this negotiation can include several items of different domains, for the sake simplicity, this paper limits the scope to privacy terms such as Social Security Number (SSN) and Credit Card number. In the above example, service provider terms specify the intention of holding web user’s credit card info for 15 days and SSN for 10 days after the transaction is executed. There can be several legal, infrastructural, and technology reasons for service provider choosing the number of days. However, the web user, as shown in Figure 2, may choose to negotiate to limit credit card data for 10 days and SSN for 5 days. Eventually, the service provider and the web user would reach an agreement. These agreed upon terms can then be part of the updated privacy agreement presented to the web user for approval. If the web user and the service provider could not reach an agreement, then the web user has an option of declining the privacy agreement and not to go ahead with the transaction. Alternately, the web user may accept the privacy agreement provided by the service provider and go ahead with the transaction.

The overwhelming question that taunts web users is that, just because a negotiate privacy agreement is reached with the service provider, does that guarantee protection of the privacy terms contained in privacy agreement (P)?

4.2. Third Party Trusted Agency

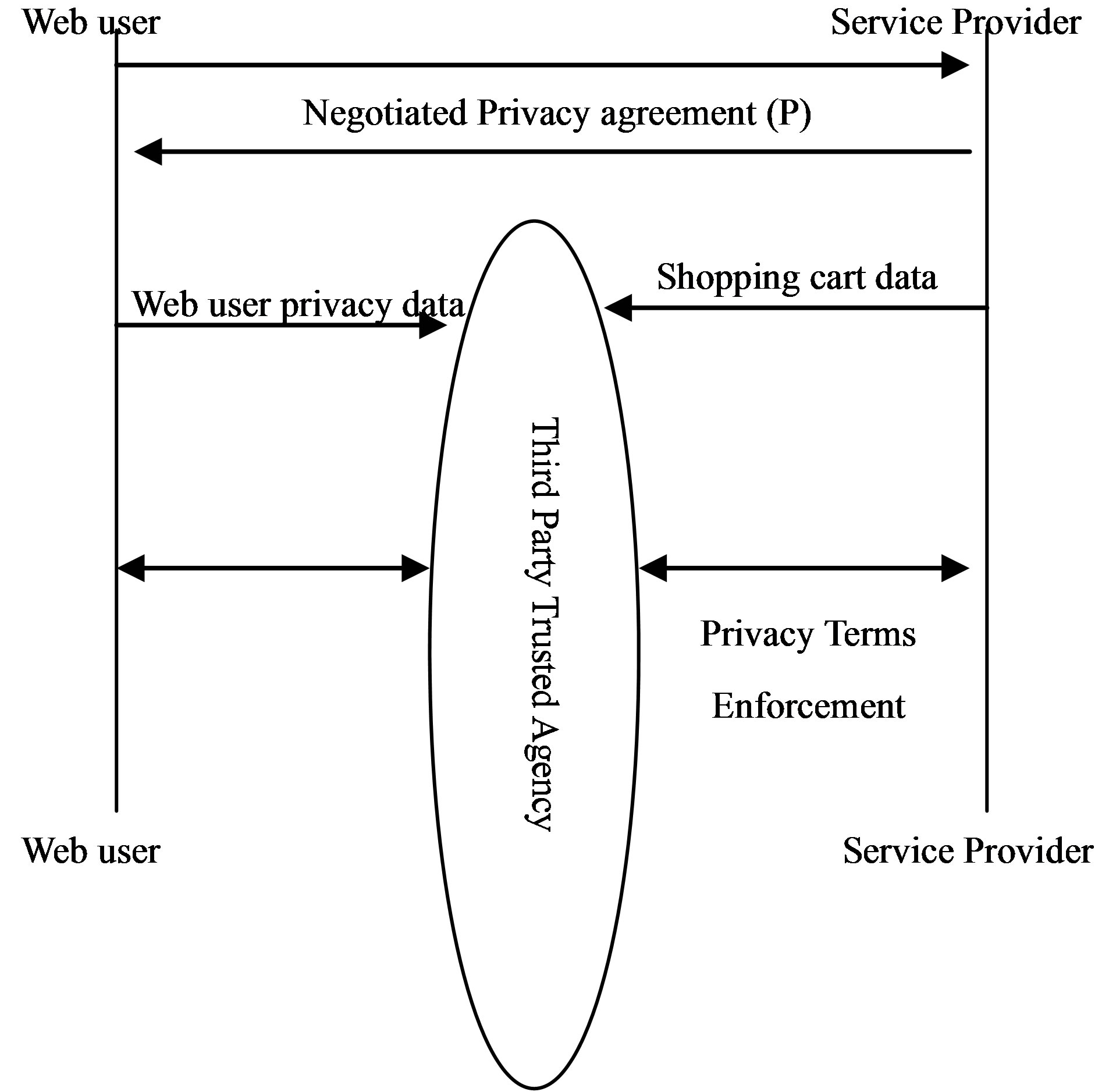

According to Pew research center, 86% of Internet users want to prohibit online companies from disclosing their personal information without permission [12]. That leads to the question of ensuring that service providers are living up to their responsibilities as agreed upon in any negotiated privacy agreement. Web users want control over what information they disclose to service providers, and they want verifiable assurances about what those sites will do with the information once it is disclosed to them. However, control over personal information on line is handled in a self regulatory fashion today, particularly, in a B2C environment. Trust negotiation presents the opportunity to develop more systematic approaches and matured privacy frameworks that web sites can adhere to when handling privacy practices on the web. Current solutions include the web site privacy logos such as TRUSTe (http://www.truste.org) and BBBOnline (http:// www.bbbonline.org ) both of which offer privacy seals to a web site that publishes its policy for privacy handling. However, the seal itself can be forged, and the mere presence of seal guarantees nothing concerning the details of the service providers’ privacy policies. One solution to this is to introduce a third party trusted agency that is acceptable to both web users as well to the service provider community. There are several certificate authorities in existence that act as third party certificate issuers trusted by senders and receivers. The idea is to let the third party trusted agency handle the privacy data as per the negotiated privacy agreement as shown in Figure 3.

In current scenarios the service provider maintains the privacy data of the web user. In the proposed model, the service provider has minimal responsibility of managing the privacy data, as it is handled by the third party trusted agency. Upon completion of the privacy term, it is the third party trusted agency that purges the data as per the privacy agreement. There are big advantages in this model for the service provider. The service providers are relieved of any privacy liability risks from handling the web users’ privacy data giving them the opportunity to focus more on fulfilling its core business rather than privacy management. For the web user, it is a definitive state that the privacy data is now out of the service provider’s domain, handled by the third party trusted agency.

5. Conclusion

Clearly, data privacy is an important topic and each web

Figure 3. An example of a third party trusted agency acting as an intermediary between web user and service provider.

site’s information security system should enforce stated privacy policy. Organizations should explore embedding privacy enhancing technologies such as privacy frameworks in their data privacy mechanisms to assure certified privacy practices in the form of digital credentials. This paper proposes two key privacy concepts—privacy terms negotiation framework and a trusted third party agency. Since privacy vulnerabilities exist when policy disclosures take place, the approach presented in this paper describes an environment to experiment with the proposed framework solution to the privacy problem. This should lead to a more formal definition of a generic privacy framework adaptable by e-commerce websites with relative ease of use. At this point, the physical implementation of the third party trusted agency along with physical and logical architecture is left to future articles work efforts.

6. Acknowledgements

Thanks for helpful discussions with Catherine Rickleman, e-learning architect at IBM, who patiently reviewed the paper for formatting as well as provided content suggestions.

REFERENCES

- G. Yee and L. Korba, “Privacy Policy Compliance for Web Services,” IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS’04), San Diego, 6-9 June 2004, pp. 158- 165. doi:10.1109/ICWS.2004.1314735

- W. Xu, R. Sekar, I. V. Ramakrishna and V. N. Venkatakrishnan, “A Framework for Building Privacy-Conscious Composite Web Services,” IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS’06), Chicago, 18-22 September 2006, pp. 655-662. doi:10.1109/ICWS.2006.4

- B. Carminati, E. Ferrari and P. C. K. Hung, “Exploring Privacy Issues in Web Services Discovery Agencies,” IEEE Security and Privacy, Vol. 3, No. 5, 2005, pp. 14- 21. doi:10.1109/MSP.2005.121

- OUT-LAW News, “Regulators Demand Clearer Privacy Policies,” 2009. http://www.out-law.com//default.aspx?page=9795

- A. Figueroa, “Privacy Issues Hit Facebook Again,” 2010. http://www.csmonitor.com/Business/new-economy/2010/0730/Privacy-issues-hit-Facebook-again

- Nick O’Neill, “10 Privacy Settings Every Facebook User Should Know,” 2009. http://www.allfacebook.com/facebook-privacy-2009-02

- Federal Trade Commission, “ChoicePoint Settles Data Security Breach Charges; to Pay $10 Million in Civil Penalties, $5 Million for Consumer Redress,” 2011. http://www.ftc.gov/opa/2006/01/choicepoint.shtm

- EPIC Staff Publication, “Choice Point: Introduction and Background,” 2001. http://epic.org/privacy/choicepoint/

- K. Tedder, “Don’t Wait for a Data Compromise,” 2010. https://www.firstdata.com/downloads/thought-leadership/fd-data-compromise-wp.pdf

- Ponemon Institute, “Ponemon Institute Research,” 2010. http://www.ponemon.org/about-ponemon-research

- PrivacyRights Group Compilation, “Chronology of Data Breaches Security Breaches 2005 to Present,” 2011. http://www.privacyrights.org/data-breach

- Pew Research Center Report, “Internet & American Life Project,”. http://www.pewinternet.org/Press-Releases/2000/86-of-Intenet-Users-Want-to-Prohibit-Online-Companies-From-Disclosing-Their-Personal-Inf.aspx