Health

Vol.5 No.1(2013), Article ID:26513,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.51003

Why adults and teachers information about sexual behavior and its consequences does not prevent unplanned pregnancies among adolescents in Nairobi, Kenya

![]()

University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya; jkinaro@yahoo.com

Received 31 October 2012; revised 6 December 2012; accepted 13 December 2012

Keywords: Sexuality Education; Source of Sexuality Information; Perceptions on Contraceptive Use

ABSTRACT

Context: Despite a high number of unwanted pregnancies in Kenya, contraceptive use among adolescents is very low. Establishing the nature of sexuality discussions is critical to determine perceptions and barriers affecting contraceptive use among adolescents. Methods: The study used systematic random sampling to collect data to examine sexuality information and knowledge that affect perception and barriers on contraceptive use among 1119 adolescents aged 15 - 19 years in Nairobi. The survey was conducted using the 2009 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey enumeration areas and projections based on the 1999 population census. Data were collected using structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews (IDIs) among adolescents, parents and teachers. Quantitative data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software while qualitative information was analyzed using iT Atlas. Results: Although teachers were identified as a primary source of sexuality information, they were poorly prepared to teach the subject. While the study found negative perceptions on sexuality education, most FGDs and IDIs supported the need for its integration in the school curriculum. Most adolescents who used contraceptives had perceptions that their parents approved. Source of sexuality information, living arrangement and perceptions on contraceptives for unmarried adolescents were statistically associated with contraceptive use. Conclusion: The study showed that sexuality information from parents and teachers was biased against adolescents using contraceptives. There is need to address attitudes in discussing contraceptive use for adolescents by parents and teachers to enhance positive perceptions and increase contraceptive use by adolescents.

1. INTRODUCTION

Although awareness of contraceptives is above 98 percent in Kenya, their use among currently married youth aged below 20 years is only 19.6 percent, although about 36 percent of youth give birth before they are 19 years old [1]. Only 5 percent of all adolescents aged 15 - 19 years use any modern method of contraceptives [1].

Low contraceptive use among adolescents has been reported globally. Despite the risks associated with early pregnancies, various surveys indicate low contraceptive use among sexually active 15 - 19 years old adolescents [2-4]. By age 20 years, over 40 percent of adolescents in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa including Kenya have had a pregnancy [5].

High adolescent fertility influences population growth and has the potential to contribute to a young age structure. According to the 2009 census in Kenya, over 55 percent of the population is below 25 years old [1]. The young age structure presents socio-economic and health challenges for the country. Early and unprotected sexual activities expose young people to pregnancy related complications and sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS. To respond to the challenges of high adolescent fertility, it is crucial to understand the underlying causes of low contraceptive use among the youth. In the Kenyan context, little is known about factors that underlie the low use of contraceptives among adolescents. In addition, little is known and documented about the perceptions of the adolescents regarding access and use of contraceptives. In Kenya, studies have focused on whether adolescents are sexually active, adolescent fertility, information and knowledge of contraceptives, assessment of clinic based family planning services and contraceptive use among high school students. In addition, none of the studies linked sexuality information of adolescents with information from their parents and their teachers. Behavior is a product of perceptions while perception is a function of different factors that influence and are influenced by personal and environmental dynamics [6]. To develop more responsive interventions that address the problem of low contraceptive use among adolescents, it is crucial to understand adolescents’ perceptions and the barriers that contribute to low contraceptive use among young people.

Perceptions about contraceptive use are influenced by the information adolescents receive from the family, school and the media [6]. However, much of sexuallyrelated information has been found to be inaccurate, ambiguous and sometimes misleading; such information has a negative impact on sexual behavior. In addition, clear guidance is lacking on the method or language to use when discussing sexuality issues, leaving messages passed to individual interpretations [7]. Sexually explicit content in the media without pregnancy prevention messages has also been found to foster unprotected sex [8]. Sex decisions among adolescents are also found to be driven by insufficient knowledge and misconceptions about contraceptive use. For example, the belief that a girl cannot become pregnant if, after intercourse, she washes her genitalia or jumps up and down, or if she has sex standing up; some adolescents prefer abortion to contraceptive use for fear of future infertility [9,10].

The social and physical environment affects adolescent perception on reproductive health and contraceptive use. Maternal approval, for example, has been associated with a higher probability of contraceptive use among adolescents [11-13]. However, in many traditional cultures, sexual activities are sanctioned only in marriage.

In African culture, sexuality issues are not freely discussed at home and premarital sex is disallowed. For example, in Nigeria, only 39 percent of parents discuss sexuality issues with their children [13]. Religious organizations oppose sexuality education in schools and they believe that such information will influence early initiation of sexual intercourse, a belief contrary to findings reported by the United Nations [14,15]. A study in Zambia shows that barriers to contraceptive use include cultural beliefs regarding how reproductive health problems are caused, prevented or cured, and perceptions that family planning services are meant for married adults only [16].

A study in Kenya illustrates that sexuality decisions among adolescents are made from insufficient knowledge and misconceptions rather than from rational considerations [16,17]. Case studies in Argentina, KenyaPeru and Philippines show that over 50 percent of adolescents say that sex education in schools is inadequate and teachers focus on discouraging students from sexual activities without teaching safe sex behavior [18]. If knowledge is inadequate or inaccurate, youth are likely to develop negative perceptions towards contraceptives and this de-motivates use through unfounded fear of side effects [19]. Accurate knowledge and communication on contraceptives gives confidence to use the methods and influences informed decision making in preventing unplanned pregnancies and HIV/AIDS [19,20].

Inadequate information and reproductive health services for young people is known to contribute to low contraceptive use among adolescents. Between 1967 and 1994, the focus of reproductive health activities in Kenya was the married woman under the maternal and child health and family planning program. However, after the 1994 International Conference for Population and Development, more attention was focused on adolescents and youth who had previously been marginalized in respect to reproductive health information and services. The Kenya Government has made efforts to promote and protect adolescent reproductive health rights. For example, one of its objectives is to double the rate of contraceptive use among adolescents aged 15 - 19 years from 4.2 percent in 1998 to 8.4 percent by 2015 [21]. Despite the emphasis on providing reproductive health services to adolescents and youth, adolescents who have began childbearing have increased dramatically from 2 percent at age 15 to 36 percent at age 19 [1].

The study used a case study in Nairobi to understand the nature of sexuality discussions that adolescents have with parents/guardians and teachers, the content of the sexual and reproductive health issues and whether information passed positively influences perceptions on contraceptive use among adolescents aged 15 - 19 years old. In-depth interviews with teachers provided understanding of school policies, the content of sexuality issues discussed in schools and recommendations to improve reproductive health discussions with students. Structured interviews were used to obtain information on the main source of sexuality information among the adolescents.

Some limitations confronted efforts to collect information on sexuality issues. The youth reported the discussions held with their family members but it was not possible to cross check the information with all the family members. The information collected was sensitive as it focused on sexuality behavior of respondents and therefore difficult to cross check across causal inferences due to social cultural bias. To overcome the limitation, the study used multiple data collection methods to allow for more probing and validation of information.

2. DATA AND METHODS

Data for this study were collected from three groups of participants: male and female adolescents aged 15 - 19 years in eight administrative divisions of Nairobi; parents; and teachers. The study used household primary data that were generated from a sampling frame of 280,400, the total projected population of adolescent 15 - 19 years in Nairobi based on the 2009 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey enumeration clusters. The study also used systematic random sampling.

The study used both quantitative and qualitative data collection. The qualitative methods were important in gathering information on causal context of contraceptive use among adolescents and some of the challenges and enablers. Quantitative methods were used for statistical measures of perceptions and barriers that influence contraceptive use.

Data collection from adolescents used both structured interviews of 1119 respondents and eight (8) FGDs. The eight FGDs included in-school, out-of-school, married and unmarried adolescents all interviewed separately. FGDs were conducted with adolescents who were identified to be sexually active and those parents who were willing to participate. Parents of adolescents interviewed were identified for IDIs. IDIs were carried out among a group of teachers and parents selected from participating enumeration areas. Forty-two (42) teachers from 30 schools in Nairobi who were mentioned by most adolescents during listing of households were interviewed. Teachers identified for IDIs included school administrators, teachers allocated counseling duties and any other person identified by the school administration to carry out counseling of students. Where the head teacher was also the school counselor, only one teacher was interviewed in that school.

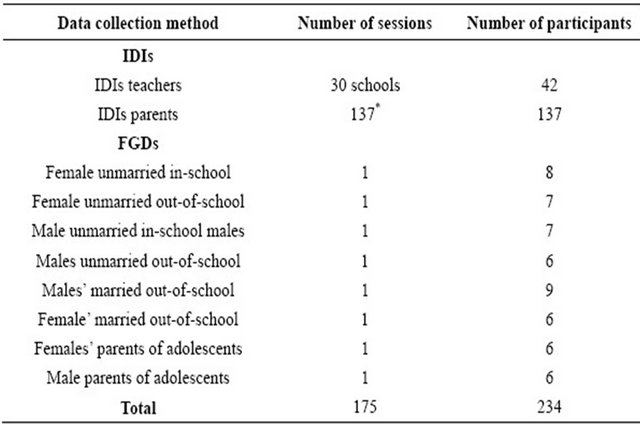

A total of 137 parents of adolescent respondents were also interviewed. Table 1 shows summary list of participants from both FGDs and IDIs. At least 4 parents were interviewed from each enumeration area. Out of 137 parents willing to be interviewed, 29 were male. Parents were interviewed during the same period individual respondent questionnaires were administered. Where the father and the mother were available in the household, they were interviewed separately.

From adolescents interviewed, 519 (46.2 percent) were males and 600 (53.8 percent) were females. Conducting in-depth interviews among parents and teachers helped generate information that contributes to better understanding of sexuality issues and content discussed in schools and among family members as well as perceptions found among these two institutions of socialization.

Data collection tools were shared with some research experts who made useful inputs. Pre-testing the tools was carried out in one of the villages in Nairobi that did not participate in the study. An interview manual was developed to train data collectors, pretest survey tools and guide fieldwork. A list of numbers from the household listing and enumeration area names and maps adopted from DHS clusters formed part of the field work guide. The household listing took three months, between January and April 2010 and interviews took two months to complete.

The ethical approval to conduct the survey was obtained from the National Council for Science and Technology Ethics and Protocols Board. Permission to use the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey enumeration areas was sought from Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The Nairobi Provincial Commissioner approved data collection in the community. The Provincial Commissioner notified and gave a copy of the study authorization to area District Officers, the Provincial Medical Officer and area Administration Chiefs. Administration Chiefs in

Table 1. Results of both FGDs and IDIs data collection.

Note: *Parents who participated in IDIs were parents of adolescents who were interviewed.

their locations provided community leaders to accompany the research team during households listing exercise.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The parents also gave verbal permission to interview their adolescent children who were below 18 years old. The study was explained to the respondents and they were reassured about the confidentiality of their names and the information they gave. Permission was sought for voice recording and taking pictures.

Quantitative data analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) while qualitative data were analyzed using the iT Atlas software package.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes adolescents’ demographic and social environment characteristics. The number of adolescents interviewed was evenly distributed among age groups and by sex. Both mean and median ages were 17 years. Table 2 shows that 46.4 percent of participants were males. Most adolescents were never married (98.3 percent % vs 1.7 percent).

Most adolescents lived with their parents or elsewhere with relatives and friends, or working as house helps (75.9 percent with parents and 22.1 percent lived elsewhere). The largest number of adolescents was reported to be attending school (86.6 percent). The main characteristics of sources of sexuality information among adolescents varied between school, family, friends and other sources. The main source of sexuality information was reported to be by teachers followed by other sources and parents (teacher 67.1 percent, other sources 17.6 percent and parents 15.3 percent). Other sources of information included peers, siblings and the media.

3.2. Sexuality Discussion

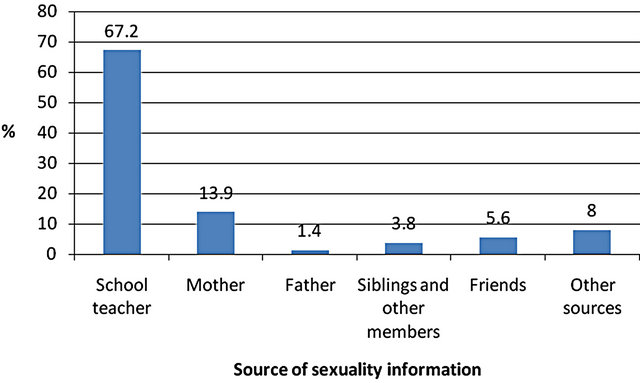

Most respondents received information on sexuality from teachers followed by mothers (Figure 1). About two-thirds (67.2 percent) of respondents received sexuality information from teachers followed by the mother (13.9 percent), and other sources (8.0 percent). The father was the least cited source of sexuality information.

Narratives from male parents support quantitative findings about the inability of the fathers to discuss sexuality issues with adolescent children. The following excerpts illustrate reasons why fathers did not discuss sexuality issues with their children:

Joseph1: “But you know the problem here is that most of the parents do not know about sex education. They do not even know when a child has started her period or menstruation” (Male parent in FGD).

Table 2. Percentage distribution of the study population according to study variables: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010 (N = 1119).

Source: Primary analysis of the data.

Figure 1. Main source of sexuality information.

Jonathan: “I differ with this guy (another parent)… is he telling us that the father as head of the house should teach the children about sex education… if the father comes home late, is he going to wake up the children at midnight to start teaching them…” (Male parent in FGD).

3.3. Sexuality Discussions at Home

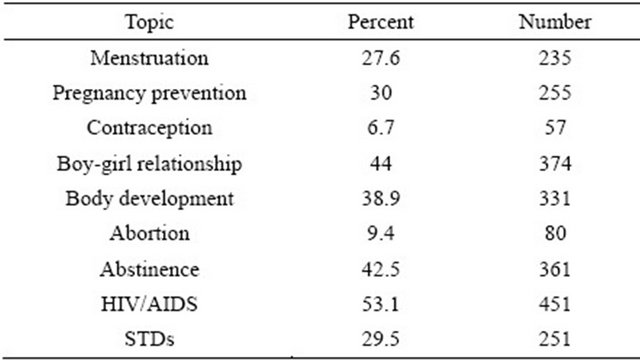

Although parents were mentioned as a main source of sexuality information at home, they rarely discussed contraceptives with their adolescent children. Only 7.5 percent of adolescents discussed contraception with their parents. Sexuality issues discussed at home were: boygirl relationships, HIV/AIDS, pregnancy prevention, abstinence, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), menstrualtion, body development, contraception and abortion in that order (Table 3).

The results of qualitative analysis support the above findings on the sexuality topics discussed at home. Discussion on HIV/AIDS and abstinence was mentioned in all FGDs and IDIs. Adolescents discussed sexuality issues more freely with their peers and siblings than with their parents. The quotes below illustrate reasons why the adolescents preferred to discuss sexuality issues with their peers:

Julianne: “I discuss those issues (sexuality issues) with my sister because she understands most of the issues that I am going through. I discuss with her also because she shares information freely” (A 15-year-old in-school female adolescent).

Selina: “I don’t discuss much with my mother because I am not free with her. We only discuss with my mother about HIV/AIDS when she gets time. For her (mother), she is very busy. She tells me that I should not engage in any sexual activity because I might get Aids and there is no cure” (In-school 18-year-old female adolescent).

The teachers also supported the need for parents to initiate sexuality discussions at home:

Table 3. Percentage distribution of topics discussed at home (N = 1119).

Notes: Calculations on this table may not add to 100 percent because the question attracted multiple responses. Respondents who selected other topics are not represented in this table.

Jerusha: “…parents should be ready to sit down with their children and talk openly because if they don’t, these children are going to get this information elsewhere…: It is the age of Internet… let them not shout at them when they are asking these questions. If parents could undergo some of the trainings… they will find it very easy to approach that subject…” (Female teacher in IDI).

At home, sexuality discussions were not planned and were only introduced when something negative happened. The following interview excerpts tell it all:

James: “My father may just start by saying he does not want to raise grandkids and I have to be patient until my time comes” (A 19-year-old out-of-school male adolescent).

Stella: “We start when I come home and I lie to my mum that I am from a particular place” (A 17-year-old in-school female adolescent).

Qualitative analysis showed that parents had negative attitudes and few talked about contraceptives with their adolescent children. Most respondents among parents in both IDIs and FGDs indicated that if they found their daughters or sons with a contraceptive, they would be annoyed. Parents cited disadvantages of contraceptives as the main focus of discussion. Parents’ negative perception on contraceptive use was found to be contrary to the general consensus about the sexuality topics they indicated to be important to discuss with their adolescent children at home, which included pregnancy prevention. One parent noted:

Mary: “I cannot allow such a thing (contraceptive use) to happen in my house. This family planning thing is a health hazard. That is what I shall tell her (daughter). Family planning destroys one’s body. From a personal experience, I can appeal to my daughter not to use contraceptives” (Female parent in IDI).

Narratives in this study indicated a consensus on sexuality education topics that were found to be important. The topics ranged from pregnancy prevention, contraceptive counseling, STI/HIV/AIDS counseling, drug abuse and abstaining from sex before marriage. However, many parents interviewed found it hard to reconcile with the knowledge that their adolescent children used contraceptives as indicated by one parent in the quote below:

Nancy: “…if I found my daughter with pills, I will swing her neck first before I seek to know where she got them (pills) from. …I will chase her (daughter) from the house and tell her to go and get married” (Female parent in FGD).

Fear of parents was therefore one of the barriers to contraceptive use. When asked what support they needed from parents, many adolescent respondents wanted support and understanding and to be allowed to use contraceptives:

John: “…they (parents) should accept that adolescents are sexually active and they need to protect themselves with condoms and pills… they should not be shouting at you… and telling you that… if I (parent) get you impregnating ladies, you will vacate this house and never sleep here again” (An 18 year-old in-school male adolescent in FGD).

From the narratives, parents seemed to lack adequate knowledge and skills to discuss sexuality issues with their adolescent children. Some of the parents indicated that their children were more knowledgeable than themselves. Language and influence of religion were also found to be a challenge in communicating with adolescents on sexuality issues: “…we are dealing with growing children who are informed. They are now young adults and they know about sex and since they are your own children, you find it embarrassing to discuss issues of sexuality and HIV”. “…some of the children are technically more knowledgeable than parents about how contraception occurs”. The narratives below further illuminate challenges of discussing sexuality issues at home:

Susan: “Using a language that your adolescent child will understand… the language that will bring him to the table becomes very hard” (Female parent in FGD).

Joseph: “To add on that of culture… religion is also a very big barrier… at least when it comes to communicating with a child about sexuality. There is no way as father… may be you go to church or mosque and… they do not speak about sexuality. Even fathers (Catholic fathers) or Imams (Muslim preachers)… they do not tell parents to go and discuss about it. So, that looks like it is prohibited. So you as a father, you do not even try to communicate about that” (Male adolescent in FGD).

3.4. Sexuality Content in School

Adolescents who responded to the question about sexuality content in school were asked to mention the topics that best described what was discussed. Similar to the trend at home, sexuality related information that dominated the discussions in school was: STDs/HIV/- AIDS followed by boy-girl relationship, abstinence and body development (Table 4). Contraception was the least discussed topic, mentioned by only 6.7 percent of the adolescents.

Most adolescents had attended classes on puberty and sexual reproductive health, but an overwhelmingly majority of both male and female adolescents wanted more classes on sexual reproductive health. About 87.3 percent of the males and 86 percent of the females preferred more classes; 2.7 percent males and 3.3 percent females felt the classes should be fewer; and those who felt the classes were about right were 10.0 percent males and 10.7 percent females (Figure 2).

School is an important socialization institution where

Table 4. Percentage distribution of topics discussed in school (N = 1119).

Notes: Calculations on this table may not add to 100% because the question attracted multiple responses.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of adolescents who preferred more sexuality education classes (N = 858).

children learn about life skills. Narratives in this study indicated that the Ministry of Education had introduced life skills curriculum in schools. However, most of the teachers and parents interviewed indicated that sexuality education in school was inadequate and unstructured. Teachers who were expected to carry out counseling activities lacked skills and they felt overburdened. Interview excerpts below illustrate the situation that existed in schools:

John: “Sexuality policy is not there…save for the last one year when they (education managers) brought in life skills…enforcement has been a little bit lacking… I think they just have an idea about that (life skills)… it can be used as a vehicle to get to the young people and their sexuality… I think it can be made better… it just came… we just found ourselves in life skills… I think those on the ground were not told what it was meant to achieve. I am saying there are topics in that syllabus that can be used alongside to teach health reproduction” (Counseling male teacher in IDI).

Janet: “Nobody is handling the subject adequately. Schools lack proper curriculum, then lack qualified teachers, then lack time. They also lack books and facilities” (Counseling female teacher in IDI).

Charity: “First of all as a teacher, we tend to put what we call don’ts… we do not get in detail. We just say do not do this, but nobody sits down with the students to talk to them about their body changes… their sexual urges… and most of the time we just concentrate… like if it is in this sciences… we just say OK, this is the human body… these are the changes that you go through, that (subject) finishes there. If it is religious subject, they (teachers) just say sex is bad… all that… the problem we have is that nobody tells them (students) that in marriage, sex is not wrong… nobody tells them that they are students and they will have those urges” (Counseling female teacher in IDI).

3.5. Perceptions on Contraceptive Use

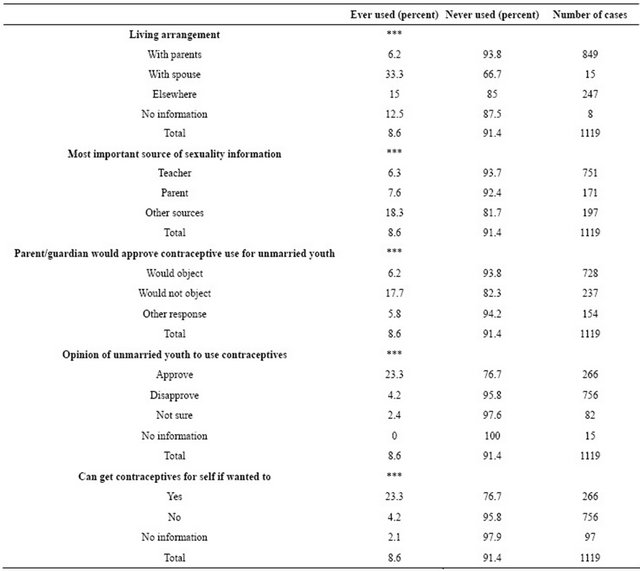

The results show that only 8.6 percent of the respondents ever used a contraceptive. The results of adolescents interviewed (data not shown here) indicated that 65.1 percent of parents disapproved of contraceptive use by unmarried adolescents. Most adolescents (67.6 percent) also disapproved of contraceptive use by unmarried youth. In addition, 67.4 percent of adolescents could not get contraceptives for themselves if they wanted to use.

Although the most important source of sexuality information was the teacher, most adolescents who used contraceptives gave their most important source of information as other sources (peers, siblings and the media). Contraceptive use was also associated with parent’s approval and approval of adolescents whose opinion was positive on unmarried youth to use contraceptives (17.7 percent parent and 23.3 percent adolescent approval) as indicated in Table 5.

Table 5. Differentials in contraceptive use by perceptions, living arrangement and main source of sexuality information.

Results of the narratives showed that the socio-cultural environment influenced contraceptive use among adolescents. Sexuality information from parents and teachers had limited influence on contraceptive use. The adolescents went through the socialization process at home and in school with minimum sexuality instruction that would otherwise have helped them understand biological processes and how to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Parents and the teachers gave inadequate information on sexuality and parents lacked the confidence to discuss sexuality issues. In many schools, sexuality education was left to unskilled teachers who gave negative messages on contraceptive use.

In all respondent interviews, participants agreed that sexuality education was important and that it should take place both in school and at home. Adolescents also indicated that parents should discuss sexuality issues with their children because they needed it: “…parents should discuss sexuality with their children freely because it is important and they should discuss it most of the time…”

The narratives from FGDs and IDIs showed the need to improve current methods used to discuss sexuality issues with adolescents. Respondents also suggested strategies to improve knowledge and skills for parents to include organized training, formation of associations, groups in residential areas and churches: “…one of the ways is to insist that women join women’s groups or belong to mothers group in churches… a mother might be able to learn a lot from mothers who have experience in handling adolescents. It is there (in women groups) that she would be told that …if you don’t teach your very own child whom you gave birth to, someone outside will, with dire consequences…”

The teachers indicated the need for training. They also indicated that trained counselors should be deployed to schools to provide counseling services only, not counseling combined with other duties. The following excerpt from a respondent illustrates the recommendations from teachers:

Jerusha: “We must engage parents in what we call seminars on sex education… because it is not only students but, even parents do not understand certain issues… so, parents should be brought on board. For example, when we are having a meeting with the parents, there should be a seminar organized specifically for them (parents)… it should be taught properly with guidelines, with books written because as much as we want to produce a person who will score an “A” or will be the first one in class, we want an all round person… we want a person who is upright morally…then make it an examinable subject so that they (teachers) take it seriously …and since it is not an examinable subject teachers don’t give all the seriousness to the discussions” (A counseling female teacher).

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study showed that only 8.6 percent of adolescents had ever used contraceptives. Studies elsewhere show that knowledge and a positive attitude towards contraception were associated with increased likelihood of contraceptive use among adolescents [22].

Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, the study found that sexuality information was provided mainly by teachers, parents and other sources (peers, siblings and the media). However, although teachers were the main source of sexuality information, they had the least influence on contraceptive use among adolescents probably because teachers rarely discussed contraceptives or abortion that would arise because of unplanned pregnancy. Narratives from teacher IDIs also confirmed that teachers focused on the “don’ts” of sexual activities without educating students on the consequences and on how to deal with the challenges of growing up. Teachers indicated that they lacked adequate knowledge and the skills to discuss adolescent sexual reproductive health issues and they also lacked a policy to guide them on sexuality education. Teachers also indicated that they lacked adequate time, a curriculum and relevant materials to guide them on sexuality discussions.

Current evidence on low contraceptive use in developing countries indicates that it is due to a socio-cultural environment that discourages sexuality discussions at home and in school [14,21]. This study found that both parents and teachers had negative perceptions on contraceptive use by unmarried adolescents. Studies elsewhere have also found that teachers focused on discouraging students from sexual activities without explaining the consequences and teaching safe sex behavior [18]. If teachers focus on abstinence, and do not discuss safe sex practices, they are unlikely to provide information on condoms and other modern contraceptives. In this study, adolescents indicated that they wanted more information on sexuality issues. This finding supports those from other studies where students indicated that sexuality education in schools was inadequate [15,18].

An earlier study in Kenya found that information on sexuality could be improved through skilled teachers who were able to create a classroom environment that makes the adolescents feel safe to discuss sexuality issues [23].

Evidence suggests that parental influence is important in shaping a child’s behavior [20]. In this study, most adolescents who used contraceptives perceived that their parents would not object. The finding of parental support concurs with other studies that found an increase in condom use among adolescents who perceived that their parents supported contraceptive use [20]. Low contraceptive use may be the result of inadequate discussion on contraception at home. In this study, contraception was among the topics least discussed at home. Inadequate discussions on contraception may be due to cultural bias on premarital sex and contraceptive use among unmarried adolescents.

Results of the qualitative analysis showed that adolescents were freer to discuss sexuality issues with their peers than with their parents. In addition, although parents discussed pregnancy prevention with their children, they focused on the negative aspects and therefore portrayed negative perceptions on contraceptive use.

The findings of this study showed that perceptions on contraceptive use by parents and adolescents on whether unmarried youth should use contraceptives were statistically associated with contraceptive use. The fact that more adolescents who used contraceptives perceived their parental approval challenges policy and programs to ensure adolescents and parents have access to accurate age specific and appropriate sexuality messages to reduce unplanned pregnancies among adolescents. The challenge is therefore to encourage parents to provide a freer environment to discuss sexuality with their adolescent children. This will help the youth make informed choices about when and where they could obtain services to avoid the consequences of unprotected sex. Positive sexuality education with messages that support contraception is likely to influence positive perceptions towards contraceptive use.

Although adolescents wanted more sexuality information, the IDIs responses indicated that parents and teachers focused more on the myths and misconceptions surrounding sexuality instead of being more open on the facts about contraceptives. The narratives showed that adolescents were not free to ask their parents questions on sexuality issues and the fear parents instilled in their children was likely to send them to other sources for information. In this study, some of the parents mentioned fear of their better informed children, indicating that parents felt inadequate to discuss sexuality issues at home.

Although some parents indicated their inadequacy on educating their children on sexuality issues, they suggested several ways in which they could empower themselves. This could be an entry point to strengthen positive discussions on adolescent sexuality issues at home. The finding from parents’ IDIs suggested the need to design and implement programs that focus on parent-child communication.

The qualitative study findings clearly demonstrated that teachers indentified the need for sexuality education in school. However, some of their own cultural and religious beliefs influenced how much information they were willing to give to the students and this had implications on the education. Even in schools where some level of sexuality information was introduced through life skills education, many teachers felt inadequate to handle the topics. The findings showed that sexuality education as a subject in Kenyan schools was not handled adequately due to lack of: a proper curriculum, qualified teachers, hours allocated to teach the subject, and relevant materials and facilities. To address cultural values, the study findings raised policy and program issues to introduce value clarification on the importance of adolescent sexuality discussions by teachers and parents. Value clarification would help parents and teachers explore their own beliefs and the benefits of sexuality education. To guide adolescents in the prevention of unplanned pregnancies, parents and teachers require more knowledge on body changes that influence biological desire to initiate sexual acts during adolescence and on how to build skills among adolescents to prevent conesquences of risky sexual behavior.

Sexuality discussions at home are carried out haphazardly through threats and this finding may explain some of the reasons why sexuality information from parents had little influence on contraceptive use among adolescents. Some parents only discussed sexuality issues when there was a crisis at home or when the child had not performed well in school, as indicated in FDGs.

5. CONCLUSION

Several policy and program issues would improve perceptions and barriers to contraceptive use arise in this study. There was a clear need to review and strengthen the content of sexuality education. The sexuality curriculum needs a clear methodology and strategies for it to be effective. Effective sexuality education requires investment in equipping teachers with knowledge and skills, and the resources to teach the subject.

To enhance contraceptive use among adolescents, programs are needed to strengthen parent-child communication. The study findings suggest the need to educate parents on adolescent sexuality issues with age specific messages. Programs could also explore strategies to enhance integration of adolescent sexual reproductive health information and services with other social activities to reach adolescents where they congregate.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is developed from a PhD thesis on “Perceptions and Barriers to Contraceptive Use among Adolescents: A case Study of Nairobi”. The study was conducted through the Population Studies and Research Institute, University of Nairobi. The work was supported by the African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship offered by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and Ford Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro (2010) Kenya demographic and health survey 2008-2009. KNBS and ICF Macro, Calverton.

- United Nations Commission on Population and Development (2012) Monitoring of population programmes, focusing on adolescents and youth. Report of the Secretary-General, 45th Session, 23-27 April 2012.

- Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) [Kenya], Ministry of Health [Kenya], and ORC Macro (2004) Kenya demographic and health survey 2003. CBS, Ministry of Health (Kenya) and ORC Macro, Calverton.

- Meekers, D. and Klein, M. (2002) Determinants of condom use among young people in urban Cameroon. Studies in Family Planning, 33, 335-346. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00335.x

- Alauddin, M. (1999) Reaching newlywed and married adolescents. Family Health International. http://www.fhi.org/en/youth/youthnet/publications/focus/newlywedandmarried.htm

- Glanz, K. Emory University and Kegler, M. (2002) Concepts of the social cognitive theory health behavior and health education: Theory, research and practice. Wiley and Sons, San Francisco.

- Undie, C., Crichton, J. and Zulu, E. (2007) Metaphors we love by: Conceptualizations of sex among young people in Malawi. Africa Journal of Reproductive Health, 11, 221-235. doi:10.2307/25549741

- Wingood, G., Ralph, J., Harrington, K., Edward, W. and Kim, M. (2001) Exposure to x-rated movies and adolescents’ sexual and contraceptive-related attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics, 107, 1116-1119. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.1116

- Nahar, Q., Tuñón, C., Houvras, I., Gazi, R., Reza, M., Huq, N. and Khuda, B. (1999) Reproductive health needs of adolescents in Bangladesh: A study report, Centre for Health and Population Research Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh ICDDR, B Working Paper No. 130. Prime Printers & Packages, Dhaka.

- Otoide, V.O.F., Oronsaye, F. and Okonofua, F.E. (2001) Why Nigerian adolescents seek abortion rather than contraception: Evidence from focus group discussions. Family Planning Perspective, 27.

- Hulton, L.A., Cullen, R. and Khalokho, S.W. (2000) Perceptions of the risk of sexual activity and their consequences among Ugandan adolescents. Studies in Family Planning, 31, 35-46. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00035.x

- Jaccord, J. and Patricia, J.D. (2000) Adolescent perceptions of maternal approval of birth control and sexual risk behavior. America Journal of Public Health, 90, 1426- 1430. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.9.1426

- Izugbara, C.O. (2007) Home-based sexuality education: Nigeria parents discussing sex with their children. Journal of Sex Education, 4, 63-79.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2009) An evidence-informed for schools, teachers and health educators. The Rationale for Sexuality Education, 1, 2-13.

- Ayiemba, E.H.O. (2001) The effect of health education programs on adolescents sexual behavior: A case study on Nairobi city adolescents. African Population Studies, 16, 87-103.

- Erulkar, A.S., Onoka, C.J. and Phiri, A. (2001) What is youth friendly adolescent’s preferences for RH services in Kenya and Zimbabwe. Africa Journal of Reproductive Health, 9, 51-58. doi:10.2307/3583411

- Kiragu, K. and Zabin, L.S. (1995) Contraceptive use among high school students in Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives, 21, 108-113. doi:10.2307/2133184

- Brown, A.D. and Shireen, J. (2001) Sexual relations among young people in developing countries: Evidence from WHO case studies. WHO, Geneva.

- De Belmonte, L.R., Gutierrez, E.Z., Magnani, R. and Lipovsek, V. (2000) Barriers to adolescents’ use of reproductive health services in three Bolivian cities. Focus on Young Adults/Pathfinder International, Washington.

- Rwenge, M. (2000) Sexual risk behavior among young people in Bamenda, Cameroon. International Family Planning Perspective, 26, 18-123. doi:10.2307/2648300

- National Coordinating Agency and Population Development and Division of Reproductive Health, Ministry of Health (2003) Adolescent reproductive health and development policy. Tonaz Agenies, Nairobi, 1-37.

- Bruckner, H. Martin, A. and Bearman, P.S. (2004) Ambivalence and pregnancy: Adolescents’ attitudes, contraceptive use and pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and reproductive Health, 36, 248-257.

- Khamasi, J., Wand, J. and Undie, C. (2008) Teaching human sexuality in higher education: A case from Western Kenya. In: Mairead, D., Ed., Gender, Sexuality and Development: Education and Society in Sub-Saharan Africa, 189-196. doi:10.1363/3624804

NOTES

1Names of respondents in this article have been changed to ensure confidentiality.