Modern Economy

Vol.07 No.07(2016), Article ID:68757,13 pages

10.4236/me.2016.77081

Determinants of the Wage Gap between Migrants and Local Urban Residents in China: 2002-2013

Xinxin Ma

Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Kunitachi, Japan

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 19 May 2016; accepted 18 July 2016; published 21 July 2016

ABSTRACT

This study explores the determinants of the wage gaps between rural-to-urban migrants and local urban residents in China from 2002 to 2013. Using the Chinese Household Income Project (CHIP) 2002 and 2013 survey data, the study provides an analysis based on the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition model. The estimation results indicate that individual characteristics, regional location, and the distribution differences among industries and public and private sectors were the main factors causing the wage gaps. Furthermore, the main factors causing the wage gaps between 2002 and 2013 are human capital factors, industry sectors, and gender discrimination.

Keywords:

Wage Gap, Migrants, Local Urban Residents, Sector Segmentation, Chinese Urban Labor Market

1. Introduction

In China, along with the transitional economy, the Chinese urban market is segregated into migrant and local urban resident groups; and there exists discrimination against migrants in employment and wages (Meng and Zhang, 2001 [1] ; Wang, 2003, 2005 [2] [3] ; Zhang, 2003 [4] ; Song and Appleton, 2006 [5] ; Ma, 2011 [6] ; Ma and Li, 2016 [7] ).

In previous studies on the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents, Wang (2003) [2] , Xie and Yao (2006) [8] , Deng (2007) [9] , Xing and Luo (2009) [10] , Ma (2011) [6] utilized the Oaxaca-Blinder model (Oaxaca, 1973 [11] ; Blinder, 1973 [12] ), the FFL model (Firpo, Fortin, and Lemieux, 2009 [13] ) or the DFL (Dinardo, Fortin and Lemieux, 1996 [14] ) model to undertake the decomposition analysis and found that both the discrimination and human capital differentials affect the wage gap; however, the influences of the discrimination on the wage gap differ among these empirical study results. Meng (1998) [15] , Meng and Zhang (2001) [1] , Ma and Li (2016) [7] analyzed occupational segregation and the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents and found that occupational discrimination is the main factor underlying the wage gap. However, these studies did not consider the sector selection bias problem in wage functions and the analysis periods reach only the early 2000s. Thus, recent factors contributing to wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents are not clear.

This study presents an empirical approach to answer the following questions: First, do wage gaps exist between migrants and local urban residents? Second, what factors determine the wage levels of migrants and urban local residents? Third, what factors determine the wage gaps between migrants and urban local residents? Finally, has the influence of these factors on the wage levels and wage gaps changed from 2002 to 2013?

This study contributes in the following ways. First, it investigates how unexplained differentials (i.e., discrimination) and explained differentials (e.g., those based on individual characteristics, including human capital factors) affected the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents during the 2000s (from 2002 to 2013). Second, it considers sector segmentations by industry sectors, public and private sectors, and regions in the Chinese urban labor market. Finally, it discusses the changes in the influences that these factors have on the wage gap from 2001 to 2013. The study’s results are new discoveries for the wage-gap issue.

This paper is structured as follows. Part 2 describes the analysis methods, including introduction to models and data. Part 3 is the description analysis results, and Part 4 states the quantitative analysis results. Part 5 presents the main conclusions.

2. Methodology and Data

2.1. Model

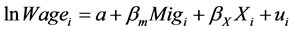

First, to explore the wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents, estimation based on OLS and quantile regression models (Koenker and Baset, 1978) are utilized [16] . The OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) analysis is express by Equation (1.1)

(1.1)

(1.1)

In Equation (1.1), i represents the individual (a migrant or a local urban resident),  is the logarithm of the average wage,

is the logarithm of the average wage,  is the migrant dummy, X represents the other factors (e.g. education, experience years, industries, occupations) which affect wage, u is a random error item. When the coefficient of the migrant dummy (

is the migrant dummy, X represents the other factors (e.g. education, experience years, industries, occupations) which affect wage, u is a random error item. When the coefficient of the migrant dummy ( ) is negatively significant, it is shown that if the other factors are consistent, the average wage level is higher for the migrants than for the local urban residents.

) is negatively significant, it is shown that if the other factors are consistent, the average wage level is higher for the migrants than for the local urban residents.

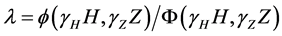

Considering the selection bias problem in Equation (1.1), the selection bias corrected wage function model is proposed (Maddala, 1983) [17] . Equation (1.2) expresses the probability of entry to industry sectors using multinomial logit model. For example, the probability to become a worker in an industry sector is expressed as , and the other probability is expressed as

, and the other probability is expressed as . H represents factors identical to those expressed in Equation (1.1)?including

. H represents factors identical to those expressed in Equation (1.1)?including  and X, Z is used as an identification variable1. Using the estimated results of the distribution function and the density function by probit regression model, selectivity items (

and X, Z is used as an identification variable1. Using the estimated results of the distribution function and the density function by probit regression model, selectivity items ( are calculated. The corrected wage functions expressed by Equation (1.3) can be estimated using these selectivity items.

are calculated. The corrected wage functions expressed by Equation (1.3) can be estimated using these selectivity items.

if

if

(1.2)

(1.2)

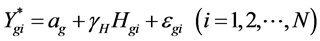

(1.3)

(1.3)

Second, to estimate what factors determine the average wage levels of migrants and local urban residents, the sample bias corrected wage functions by migrants and local urban residents are estimated.

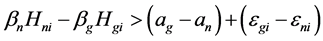

Finally, to estimate which factor determinates he wage gap between migrants and local urban residents, the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition model is utilized. Based on wage functions, the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition model can be derived as Equation ((3.1), (3.2)).

(3.1)

(3.1)

In Equations ((3.1), (3.2)), u represents local urban residents, rm represents rural migrants,

2.2. Data

The survey data of CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013 are used for the analysis. These data are gained from the two surveys of Chinese Household Income Project conducted by NBS, Economic Institute of Chinese Academy Social Science (CASS) and Beijing Normal University (BNU) in 2003 and 2014, including respective information about the individual characteristic factors, industries, workplace ownership types and wages of migrants and local urban residents. Because there are design similarities of the data in the questionnaire, we can use the same information for analysis for two periods.

CHIP surveys cover the representative regions in China, including Beijing, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Anhui, Guangdong, Henan, Hubei, Sichuan, Chongqing, Yunnan, and Gansu in CHIPs2002, and Beijing, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Anhui, Guangdong, Henan, Hubei, Sichuan, Chongqi, Yunnan, Gansu, Shanghai, Zherjiang, Fujian, Hunan in CHIPs 2013. To make comparisons in two periods and address the sample distribution bias problem, we selected the regions (provinces or cities) covered in all two surveys, including Beijing, Shanxi, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Anhui, Guangdong, Henan, Hubei, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu.

2.3. Variables Setting

The wage is defined as the total earnings from work (called “the total wage”). Here, it comprises the basic wage, bonus, cash subsidy, and no cash subsidy. The CPI in 2002 is utilized as the standard to adjust the nominal wage in 2013.

The analytic objects of this study are workers, excluding the unemployed. In considering the retirement system implemented in the public sector―the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the government organizations, to reduce the effect of that system on the analysis result, analytic objects are limited in the groups to between the ages of 16 and 60. No answer samples, abnormal value samples2, and the missing value samples are deleted.

To see the depended variables setting. First, to correct the sample selection bias by the probability of entry to the monopoly or the competitive industry sectors, the probability function of entry to industries is estimated. In the probability function of entry to industries, the depended variable is a category variable. To maintain the analysis samples by each industry category and consider the feature of the industry distributions of migrants, the industrial categories in the CHIPs3 are reclassified. Five kinds of industries―construction, manufacturing, retail and wholesale industries, service, and other industries are utilized to construct the category variable.

Second, in the wage function, the depended variable is the logarithm of the wage rate. The wage rates are calculated based on total wage and work hours. The CHIP survey data for local urban residents are included those who were re-employed as non-regular workers after the employment adjustment of state-owned enterprises. The total wage in those samples are the total value of base salary, bonuses and goods calculated by monetary, excluding layoff living assistance, minimum income assistance, and living assistance by firms, income by asset and financials, security transfer income. For work hours, work hours yearly for local urban residents are calculated by “work hours daily × work days monthly × work month yearly”, and work hours monthly for migrants are calculated by “work hours daily × work days weekly × 4”. Wage rate are calculated by total wage divided by work hours.

The independent variables are the variables likely to affect the wage, they are conducted as the follows.

First, education (primary school or below, junior high school, senior high school/vocational school, college and above), experience years4, age, health status (very good, good, fair, bad) are conducted as the index of human capital. It is though that these might factors affect the wage level.

Second, because labor market is segmented by the public- and private-sectors in China, and it is pointed out that there exists wage gaps between public- and private-sectors (Chen, Demurger, and Fournier, 2005 [18] ; Zhang and Xue, 2008 [19] ; Ye, Li, and Luo, 2011 [20] ; Demurger, Li, and Yang, 2012 [21] ; Zhang, 2012 [22] ; Ma, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016 [23] - [26] ), the public sector dummy variable and the private sector dummy variable are conducted to control the influence of ownerships on the wage gaps. Concretely, the public sector include state-owned enterprises (SOE) and government organizations, the private sector composes of collectively owned enterprises (COE) and foreign/private enterprises, self-employed workers, and other ownerships.

Third, it is thought that the special political membership may affect the wage levels. Party membership dummy is used in the analysis.

Fourth, considering gender, the married, and the race might affect the wage levels, these dummy variables are utilized.

Finally, because there exists regional disparity for economic development levels, and the labor markets are different by the regions, East, Central, West regions dummy variables are used to control these influences.

3. Descriptive Statistics of the Data

3.1. Individual Characteristics Differentials by Migrants and Local Urban Residents in 2002 and 2013

The data’s descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The individual characteristics of the differentials by migrants and local urban residents are observed as follows:

First, the logarithms of the average wage rates are higher for local urban residents than for migrants for both 2002 and 2013. For local urban residents, they are 1.524 and 2.608 for 2002 and 2013, and for migrants, they are 0.861 and 2.442 in 2002 and 2013. In addition, the wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents declined from 2002 (−0.663) to 2013 (−0.166).

Second, the individual characteristic differentials between migrants and local urban residents show that years of experience are greater, and ages are higher for local urban residents than for migrants, in both 2002 and 2013. These results are consistent with the phenomenon that most of the younger labor force with rural registrations is moving to and working in urban areas. However, the differentials of experience years between these two groups become small from 2002 to 2013.

Third, although in both 2002 and 2013 the proportion of workers with higher education (such as senior high school and college/university) is smaller for the migrants group, the proportion of migrant workers that has graduated from senior high school rises from 17.7% (2002) to 22.4% (2013), while the proportion of workers who have graduated from college or university rises from 2.3% (2002) to 12.0% (2013). These results show that education differentials between local urban residents and migrants have changed greatly from 2002 to 2013.

Fourth, in both 2002 and 2013, the proportion of communist party member is greater for local urban residents (29.3% in 2002, 20.8% in 2013) than for migrants (3.3% in 2002, 4.3% in 2013).

Fifth, in both 2002 and 2013, the proportions who answered that their health status is “very good” is greater for migrants than for local urban residents. However, the health differentials between these two groups decreased from 2002 to 2013.

Sixth, in both 2002 and 2013, there are differences in proportions in terms of gender and ethnicity between migrants and local urban residents, though these are smaller than for other factors.

Seventh, in both 2002 and 2013, although most of migrants work in the retail/catering, and service industry sectors, the industry distribution differentials between migrants and local urban residents become smaller from

Table 1. Differentials of variable distributions and mean values between migrants and local urban residents in 2002 and 2013.

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013. Note: Samples limited on age 16 - 60.

2002 to 2013.

Finally, in both 2002 and 2013, most of local urban residents work in the public sector (66.7% in 2002, 40.7% in 2013), whereas the proportion of self-employed workers is greater for migrants (73.0% in 2002, 44.4% in 2013). Moreover, the proportion of workers in the private sectors rises greatly for both migrants and local urban residents. For examples, the proportion rises from 13.8% (2002) to 32.3% (2013) for local urban residents, and it rises from 11.6% (2002) to 39.1% (2013) for migrants. These results reveal that along with the decrease of worker share in the public sector, private sector absorbed more workers (both migrants and local urban residents) from 2002 to 2013.

3.2. Wage Distributions by Migrants and Local Urban Residents in 2002 and 2013

The estimated kernel density of the logarithm of the wage rate is shown in Figure 1, the main finding are as follows:

The density of high-wage groups is greater for local urban residents than for migrants in both 2002 and 2013. It is indicated that the proportion of workers with a high wage is greater for local urban residents than for migrants. It can be concluded that the majority of workers with high wages in 2013 were local urban residents during the 2000s. Additionally, the proportion of individuals with low wages is also greater for the local urban residents than for the migrants. The dispersion of wage rate in the intra-group is shown to be greater for the local urban residents than for the migrants.

Moreover, when comparing the change of the estimated kernel density curve, the differentials between migrants and local urban residents reduced from 2002 to 2013. This indicates that along with the marketization economy system transition from 2002 to 2013, the wage gaps between these two groups decreased.

Table 2 shows the statistical value of the logarithm of wage rate. The mean values and the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of wages are all higher for local urban residents than those for migrants in both 2002 and 2013. For example, the mean values for local urban residents in 2002 and 2013 (1.516 and 2.605 respectively) are higher than those for migrants (0.855 in 2002 and 2.434 in 2013).

Moreover, the maximum values of the logarithm of the wage rate are all higher for local urban residents than those for migrants. Similarly, the minimum values of the logarithm of the wage rate are all lower for local urban residents than those for migrants in both 2002 and 2013. For example, the maximum values of the logarithm of the wage rate for local urban residents in 2002 and 2013 (4.504 and 6.543 respectively) are higher than those for migrants (4.241 in 2002, 4.956 in 2013). In the same manner, the minimum values of the logarithm of wage rate for local urban residents in 2002 and 2013 (−1.515 and −2.092 respectively) are lower than those for migrants (−1.253 in 2002, −1.030 in 2013). Thus, the standard deviation is greater for local urban residents (0.721 in 2002 and 0.792 in 2013) than for migrants (0.684 in 2002 and 0.729 in 2013). These results are consistent with the Kernel Density estimated results.

Figure 1. Kernel density estimates of the logarithm of wage rate distributions by migrants and local urban residents in 2002 and 2013.

Table 2. Statistical values of the logarithm of the wage rate by migrants and local urban residents in 2002 and 2013.

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013.

Although these tabulation calculation results indicate that the individual characteristics, the wage density distributions are different for migrants and local urban residents, and that there exist wage gaps between the two groups, the factors that might affect the probabilities of entry to industry sectors and the wage level differentials have not been controlled in these results. An econometric analysis is thus conducted as follows.

4. Econometric Analysis Results

4.1. Do Wage Gaps Exist between Migrants and Local Urban Residents?

Table 3 demonstrates the results for wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents. First, the wage gap based on model 1 is estimated as −0.654 in 2002 and −0.166 in 2013. Moreover, when the other factors are not controlled, the average wage level for migrants is 65.4%, which is 16.6% lower than that for local urban residents. When the main human capital factors (work experience and education) are consistent (model 2 and model 3), the wage gaps decrease to −0.481 in 2002 and 0.055 in 2013. These results indicate that education is the main factor that causes the wage gap.

Second, when the workplace ownership is consistent, wage gaps decrease to −0.192 (model 9) in 2002. This result suggests that workplace ownership is also a main determinant of the wage gap.

Finally, compared to 2002, the wage gap reduces in 2013. Particularly, when education is consistent, the average wage level for migrants is higher than that for local urban residents. These results can be explained as follows: Along with economic development, the surplus labor decreased and labor productivity increased in the rural region; thus, the wage level of migrants―which is mainly determined by the subsistence level in the rural region―increased. Consequently, the wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents decreased from 2002 to 2013.

4.2. What Factors Determine the Wage Levels of Migrants and Urban Local Residents?

Which factor determinates the wage levels of migrants and urban local residents? To answer this question, wage functions are estimated, the results being shown in Table 3.

First, the Maddala model is utilized to adjust the sample selection bias caused by the choice of entry to an industry. In both 2002 and 2013, the correct items are statistically significant for the local urban residents group and the coefficients of these correct items are all negative values. The results for the local urban residents group will thus be overestimated when these selection biases are not adjusted.

Second, U-shaped curves can be constructed from the estimated results for years of experience and their squared values, with points of inflection at 20 years for migrants and 46 years for local urban residents in 2002,

Table 3. Results of wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents.

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013. Note: Samples limited on age 16 - 60.

and at 13 years for migrants and 23 years for local urban residents in 2013. Thus, while work experience affected wage levels for migrants and local urban residents, the effect was greater for local urban residents than for migrants in both 2002 and 2013.

Third, in 2002, wages for the low-level education group (primary school) were less than those of the mid-level education group (junior high school) and higher for the high-level education groups (senior high school, college/university) for both migrants and local urban residents. However, in 2013, wages for the low-level education group were higher compared to the mid-level education group for migrants. In addition, if other factors are constant, the wage differentials between the different education groups are statistically insignificant. These results show that the returns on education have recently risen for low-skill migrants.

Fourth, in 2002, there are gender wage gaps for both migrants and local urban residents, and this was higher for migrants (−0.518) than for local urban residents (−0.115). However, in 2013, although the gender wage persisted for local urban residents (−0.178), it was not statistically significant for migrants. These results indicate that if other factors remain constant, gender wage gaps increased for local urban residents (female dummy coefficients change from −0.115 to −0.178), but decreased for migrants.

Fifth, considering segmentation by workplace ownership types in 2002, public-sector wages were lower than private-sector wages or for the self-employed sector for migrants, whereas wages were lower for private-sector workers or the self-employed for local urban residents. In addition, while wages for private-sector or self-em- ployed workers in 2013 were lower for local urban residents, they decreased from 2002 to 2013. Moreover, wage gap differentials between each sector were not statistically significant for migrants in 2013. These results indicate that wage gaps by workplace ownership type decreased recently, all other factors remaining the same.

Sixth, we next consider the industry-level segmentation. Both migrant and local urban resident workers earned more in the construction industry than in the manufacturing industry in 2002 and 2013. Moreover, wages for both types of workers were lower for those in the retail/catering and service industries in 2002. However, while the results for the retail/catering and service industries remained consistent with the results in 2002 for local urban residents, the coefficients increased and were not statistically significant for migrants in 2013. Thus, all other factors constant, the industrial wage gaps declined for migrants and increased for local urban residents5.

Finally, In terms of regional location, both migrant and local urban resident workers in the central region earned less than those in the eastern and western regions in 2002 and 2013. These results show that regional wage disparities persisted from 2002 to 2013 for these two groups.

4.3. What Factors Determine the Wage Gaps between Migrants and Local Urban Residents?

Which factors determine the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents? The Oaxaca-Blinder model is utilized to decompose the factors that contribute to the wage gap based on the estimated results shown in Table 4 and Table 5. Table 6 and Table 7 report the decomposition results using the human capital factors and by labor market segmentation (industry, workplace ownership, and region), respectively. The main findings are as follows:

First, in both 2002 and 2013, the main factor causing the wage gap is the contribution of the explained differentials. These contributions are 63.1% (Estimation 1) and 105.1% (Estimation 2) in 2002, and 125.4% (Estimation 1) and 129.7% (Estimation 2) in 2013. The results of Estimation 1 are consistent with Wang (2005) [3] and Mautrer-Fazio and Dinh (2004) [27] , the results of Estimation 2 are consistent with Xing (2008). In addition, if labor market segmentation factors are considered, the contribution of explained differentials becomes greater in both 2002 and 2013. These results indicate that the individual characteristic differentials and the different distributions among industry sectors and regions as well as between the public- and private-sector are the main factors affecting the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents. It is thought that the different distributions among sectors might be caused by the discrimination when the migrants entrance to the monopoly industry sectors or the public sector. So it can be said the labor market segmentation by systems are one of the main factors affecting the wage gap.

Second, to consider in detail the factors underlying the explained differentials, based on Table 4 (Estimation 2), the contributions of ownership (45.1%), education (35.2%), and industry (15.5%) are the greatest in 2002, while the contributions of education (99.8%), ownership (15.8%), and industry (13.4%) are the greatest in 2013. The results indicate that industry, ownership, and education are the main factors causing the wage gaps in the 2002-2013 period.

Finally, to consider in detail the factors underlying the unexplained differentials, based on Table 7 (Estimation 2), experience (29.1%) and industry (22.9%) are the main causes of the wage gap in 2002, whereas in 2013, the influences of experience (26.9%) and gender (31.1%) are the greatest. These results indicated that discrimination within the industry sector, gender discrimination, and discrimination based on a seniority wage system are the main factors affecting the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents.

Table 4. Results of wage functions (2002).

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013. Note: 1) *, **, ***: statistical significant levels are10%, 5%, 1%; 2) The Maddala model is utilized, and the correct items of industry sectors selection bias are controlled in the analysis; 3) U-M = Urban-Migrant.

Table 5. Results of wage functions (2013).

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013. Note: 1) *, **, ***: statistical significant levels are10%, 5%, 1%; 2) The Maddala model is utilized, and the correct items of industry sectors selection bias are controlled in the analysis; 3) U-M = coef. of urban-coef. of Migrant.

5. Conclusions

This study explores which factors determine the wage gap between rural-to-urban migrants and local urban residents in China from 2002 to 2013. Using the Chinese Household Income Project Surveys (CHIPs) for 2002 and 2013, the Oaxaca-Blinder model is utilized for a decomposition analysis of the wage gap. Several major conclusions emerge.

First, when compared with unexplained differentials, the influence of explained differentials is greater in both 2002 and 2013. In addition, if labor market segmentation factors are considered, the contribution of explained

Table 6. Decomposition results of wage gaps (Estimation 1).

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013.

Table 7. Decomposition results of wage gaps (Estimation 2).

Source: Calculated based on CHIPs 2002 and CHIPs 2013.

differentials becomes greater for both 2002 and 2013. These results indicate that the individual characteristic differentials and the different distributions among industry sectors and regions, as well as between the public- and private-sector, are the main factors affecting the wage gap between migrants and local urban residents.

Second, considering the components of the explained differentials, the influences of workplace ownership types, education levels, and industry sectors are the greatest in both 2002 and 2013. It is indicated that the human capital differentials and the sector segmentations are the main factors causing the wage gap in the 2002 to 2013 period.

Third, considering the components of the unexplained differentials, the influences of industry sectors, gender and work experience years are the greatest in both 2002 and 2013. They show that the discrimination in the same industry sector, gender discrimination, and discrimination based on a seniority wage system are the main factors causing the wage gap.

These findings indicate that to reduce wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents, employment equality laws and an equal pay for equal work policy are immediate priorities. Policies that aim to reduce human capital differentials between these two groups, such as education and years of experience, should also be implemented in the long term. Moreover, in order to address the labor market segmentation problems fundamentally, the enforcement of economy systems transition from the planned economy to the marketization economy is an important issue for Chinese government in the long term.

Funding

This research was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 16K03611) of JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion Science), and Joint Usage and Research Center Project, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University.

Cite this paper

Xinxin Ma, (2016) Determinants of the Wage Gap between Migrants and Local Urban Residents in China: 2002-2013. Modern Economy,07,786-798. doi: 10.4236/me.2016.77081

References

- 1. Meng, X. and Zhang, J. (2001) Two-Tier Labor Market in Urban China: Occupational Segregation and Wage Differentials between Urban Residents and Rural Migrants in Shanghai. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29, 485-504.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jcec.2001.1730 - 2. Wang, M. (2003) Wage Differentials in the Transition Period: An Econometric Analysis on the Discrimination. Quantitative & Technical Economics, 5, 94-98.

- 3. Wang, M. (2005) Work Chance and Wage Differentials in the Urban Labor Market: Work and Wage of Migrants. Chinese Social Sciences, 5, 36-46.

- 4. Zhang, Z. (2003) Labor Market. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 4, 45-62.

- 5. Song, L. and Appleton, S. (2006) The Fight between Gaining Interests Group and Non-Gaining Interests group in Chinese Labor Market: Searching for Job and Government Intervention. In: Cai, F. and Bai, N., Eds., Transition and Migrants in China, Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing, 167-188.

- 6. Ma, X. (2011) Immigration and Labor Market Segmentation in Urban China: An Empirical Analysis of Income Gaps between Migrants and Urban Register Workers. Japanese Journal of Comparative Economics, 48, 39-55.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5760/jjce.48.1_39 - 7. Ma, X. and Li, S. (2016) Industrial Segregation and Wage Gaps between Migrants and Local Urban Residents in China: 2002-2013. Center for Economic Institutions (CEI) Working Paper Series No. 2016-3, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University.

- 8. Xie, S. and Yao, X. (2006) An Analysis on the Discrimination on Migrants. Chinese Agriculture Economics, 4, 39-55.

- 9. Deng, Q. (2007) Earning Differentials between Urban Residents and Rural Migrants: Evidence from Oaxaca Blinder and Quantile Regression Decompositions. Chinese Journal of Population Sciences, 2, 8-16.

- 10. Xing, C. and Luo, C. (2009) Income Inequality between Migrants and Local Urban Residents: A Semiparametric Approach. Quantitative & Technical Economics, 10, 74-86.

- 11. Oaxaca, R.L. (1973) Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. International Economic Review, 14, 693-709.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2525981 - 12. Blinder, A.S. (1973) Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimation. The Journal of Human Resources, 8, 436-455.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/144855 - 13. Firpo, S., Fortin, M.N. and Lemieux, T. (2009) Unconditional Quantile Regressions. Econometrica, 77, 953-973.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3982/ECTA6822 - 14. DiNardo, J., Fortin, M.N. and Lemieux, T. (1996) Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973-1992: A Semiparametric Approach. Econometrica, 64, 1001-1044.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2171954 - 15. Meng, X. (1998) Gender Occupational Segregation and Its Impact on the Wage Differential among Rural-Urban Migrant: A Chinese Case Study. Applied Economics, 30, 741-752.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/000368498325444 - 16. Koenker, R.W. and Bassett, G.J. (1978) Regression Quantiles. Econometrica, 46, 33-50.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1913643 - 17. Maddala, G.S. (1983) Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics. Cambridge University Press, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511810176 - 18. Chen, G., Demurger, S. and Fournier, M. (2005) Wage Differentials and Ownership Structure of China’s Enterprise. World Economic Paper, 6, 11-31.

- 19. Zhang, J. and Xue, X. (2008) State and Non-State Sector Wage Differentials and Human Capital Contribution. Economic Research, 4, 15-25.

- 20. Ye, L., Li, S. and Luo, C. (2011) Industrial Monopoly, Ownership and Enterprises Wage Inequality: An Empirical Research Based on the First National Economic Census of Enterprises Data. Management World, 4, 26-36.

- 21. Démurger, S., Li, S. and Yang, J. (2012) Earning Differentials between the Public and Private Sectors in China: Exploring Changes for Urban Local Residents in the 2000s. China Economic Review, 23, 138-153.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2011.08.007 - 22. Zhang, Y. (2012) The Change of Income Differentials between Public and Nonpublic Sector in China. Economic Research, 4, 77-88.

- 23. Ma, X. (2012) Industrial Segregation in Labor Market: An Empirical Study on the Wage Gaps between the Monopoly Industry and Competitive Industry. Chinese Labor Economics, 7, 44-82.

- 24. Ma, X. (2014) Wage Policy: Economy Transition and Wage Differentials of Sectors. In: Nakagane, K., Ed., How Did the Chinese Economy Change? The Evaluations of Economic Systems and Policies in Post-Reform Period. Kokusai Shoin Co., Ltd., Greater Taegu City.

- 25. Ma, X. (2015) Economic Transition and Wage Differentials between Public and Private Sectors in China. China-USA Business Review, 14, 477-494.

http://dx.doi.org/10.17265/1537-1514/2015.10.001 - 26. Ma, X. (2016) Changes of Wage Structures in Chinese Public and Private Sectors: 1995-2007. Management Studies, 4, 243-255.

http://www.davidpublisher.com/Home/Journal/MS - 27. Mautrer-Fazio, M. and Dinh, N. (2004) Differential Rewards to, and Contributions of, Education in Urban China’s Segmented Labor Markets. Pacific Economic Review, 9, 173-189.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0106.2004.00243.x

NOTES

1Age, age-squared are used as identification variables in the study.

2That variable values are not in the range of “mean value ± three times S.D.” is defined as abnormal value here.

3The numbers of industry categories are sixteen in the survey for local urban residents, and they are twenty-five in the survey for migrants in CHIPs.

4Experience years = age − schooling years.

5For the latest empirical study on the industrial segregation and wage gaps between migrants and local urban residents, please see Ma and Li (2016) [7] .