Advances in Pure Mathematics

Vol.06 No.12(2016), Article ID:71951,51 pages

10.4236/apm.2016.612064

The Theory of Higher-Order Types of Asymptotic Variation for Differentiable Functions. Part II: Algebraic Operations and Types of Exponential Variation

Antonio Granata

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Calabria, Rende (Cosenza), Italy

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: September 7, 2016; Accepted: November 8, 2016; Published: November 11, 2016

ABSTRACT

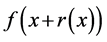

In this second part, we thoroughly examine the types of higher-order asymptotic variation of a function obtained by all possible basic algebraic operations on higher-order varying functions. The pertinent proofs are somewhat demanding except when all the involved functions are regularly varying. Next, we give an exposition of three types of exponential variation with an exhaustive list of various asymptotic functional equations satisfied by these functions and detailed results concerning operations on them. Simple applications to integrals of a product and asymptotic behavior of sums are given. The paper concludes with applications of higher-order regular, rapid or exponential variation to asymptotic expansions for an expression of type .

.

Keywords:

Higher-Order Regularly-Varying Functions, Higher-Order Rapidly-Varying Functions, Smoothly-Varying Functions, Exponentially-Varying Functions, Asymptotic Functional Equations, Asymptotic Expansions

6. Introduction to Part II

We continue the exposition and the section numbering in Part I [1] .

-In §7 we thoroughly examine the types of higher-order asymptotic variation of functions obtained by all basic algebraic operations on higher-order varying functions. For smooth variation the proofs are quite easy using the Balkema-Geluk-de Haan characterization, but proofs for regular or rapid variation require lenghty calculations and careful use of Leibniz’s, Faà Di Bruno’s or Ostrowski’s formulas for higher derivatives of, respectively, a product, a composition or an inversion; these results are not to be found in the literature. Unlike the first-order case the results for higher orders are not granted a priori and in fact restrictions are necessary for definite results in each single case: exhaustive counterexamples are exhibited.

-In §8 we highlight three concepts related to exponential variation which we label as “hypo-exponential” or “exponential” or “hyper-exponential” variation. These classes of functions, though classical, are cursorily treated in the literature and we have collected together all the basic properties, especially many useful “asymptotic functional equa- tions”. Types of higher-order exponentiality are then easily defined.

-§9 contains a detailed account of operations with the three types of exponential variation; results about composition require careful statements and lengthy calculations as in §7. The class of hypoexponentiality is too large and that of hyperexponentiality is too vague to obtain definite results but the additional assumption of rapid variation (in our restricted sense) turns out to be the right one to obtain useful results.

-§10 exhibits two simple applications: an elementary result about the value of the limit of the two ratios

and an improvement of a fundamental classical result about the principal part, as , of a sum

, of a sum  or

or . Results more general than the classical ones are obtained by simpler proofs.

. Results more general than the classical ones are obtained by simpler proofs.

-§11 concludes the paper with a number of asymptotic expansions for an expression of type , as

, as , under assumptions of higher-order variations on f, results which reveal useful in iterative processes to determine the behavior of solutions of some functional equations, such as implicit functions.

, under assumptions of higher-order variations on f, results which reveal useful in iterative processes to determine the behavior of solutions of some functional equations, such as implicit functions.

For later references we quote some known “Combinatorial formulas for composition and inversion”.

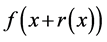

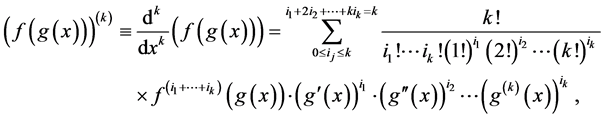

-Faà Di Bruno’s formula for derivatives of a composition, Bourbaki( [2] ; p. I.47) or Comtet ( [3] ; p. 137):

(6.1)

(6.1)

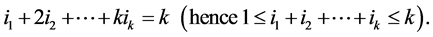

where the summation is taken over all possible ordered k-tuples of non-negative integers  such that

such that

(6.2)

(6.2)

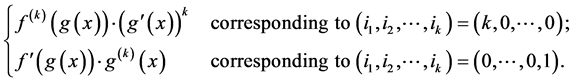

Notice that in the preceding sum there is only one term containing  and only one term containing

and only one term containing , both with coefficient 1, namely:

, both with coefficient 1, namely:

(6.3)

(6.3)

-A formula for higher derivatives of an inverse function, Ostrowski ( [4] ; pp. 20-21, 290-293). For , the inverse function of a k-time differentiable

, the inverse function of a k-time differentiable  with

with , the formula holds true:

, the formula holds true:

(6.4)

(6.4)

where the summation is taken over all ordered k-tuples of non-negative integers  such that

such that

Another version of this formula has been proved by Johnson [5] using combinatorial reasonings.

In this paper, the symbol

7. Operations with Higher-Order Regular and Rapid Variation

We examine in this section what can be asserted about the order of variation of the product, composition and inverse of regularly-, smoothly- or rapidly-varying functions of higher order. The reader may notice that in the theory of Hardy fields the main results in this section are assumed to hold true whereas we, assuming that the involved functions belong to some of the studied classes, show that their product, composition and inverse belong to a specified class; and this requires a certain computational effort the proofs being based on the above-reported formulas for composition and inversion. Let us start from smooth variation.

7.1. Operations with Higher-Order Smoothly-Varying Functions

Balkema, Geluk and de Haan, ( [6] ; p. 412), and Bingham, Goldie and Teugels, ( [7] ; p. 46) notice that the properties

imply

with the appropriate indexes specified in Proposition 2.1 and with a restriction on the index of g. These inferences require no painful direct proofs because the corresponding properties for the associated functions, defined in (3.24), are easily checked. Here is a statement completed with a result about linear combination and a few remarks. Whenever a power

Proposition 7.1. (Operations with smoothly-varying functions). If

For a linear combination, we have the results:

Proof. Without loss of generality suppose

The relations in (3.24) being assumed for

Lemma 7.2.

Proof of the Lemma. The argument is quite easy if based on relations (3.21). To prove (7.7) we use the assumptions “

as

as we have “

We can now prove properties in (7.4) writing

For

7.2. Operations with Higher-Order Regularly- or Rapidly-Varying Functions

We rewrite here the inclusions in (3.39):

which imply that the results involving only regular variation follow at once from the corresponding ones in Proposition 7.1 adding the restriction that the final index is not an integer whereas results involving rapid variation cannot be inferred from properties of the associated functions, as remarked in §4 after (4.25), but must be proved by directly working on formulas (6.1) and (6.4). For rapid variation of higher order we are using the strong concept in Definition 4.1.

Proposition 7.3. (Product of higher-order varying functions). (I) If

then

(II)

(III)

(Notice the assumption on g, milder than

Proof. For part (I) we have, by Proposition 7.1, that

a class of functions coinciding with

First case:

Here, by the positivity of all the terms in the sum, the expression

Second case:

The proof of part (III) requires a different device made clear by the case

having used relations in (4.9) for

Now from both assumptions “

And replacing this last relation into the right-hand side in (7.22), we finally get the sought-for relation

For

where for

,

Remarks on the case of regular variation. 1. A direct proof for

instead of the sole condition for

2. About the restrictions on the indexes notice that, if

then it is not always true that

with a well-defined

Example 1:

Example 2:

Example 3:

3. The function

which is basic and trivially true for

Proposition 7.4. (Quotient). (I) If

then

(II)

Proof. In both cases (7.3) implies

As concerns composition we give some general results with different restrictions on the indexes and exhibit counterexamples concerning the restrictions.

Proposition 7.5. (Composition involving only regular variation). Assumptions for all the cases to be treated:

for the values of k specified in each statement. We already know that

(I) (The case

with no restriction on

(II) (The regular case). If

then Proposition 7.1 and (7.12) imply:

(III) (The exceptional case

then

The above results apply to the special case of a power

Proof. Part (I) is easily proved applying the definition of “

For part (III) let us notice that, by part (I), we already know that

hence we have to prove that h is of order

with suitable coefficients

with suitable constants

with a new constant

which implies

which, together with (7.44) and (7.48), implies

Notice that retracing the foregoing steps by expressing the quantities

Counterexamples showing the non-existence of a definite result in case

Two counterexamples with:

A similar counterexample with:

Proposition 7.6. (Composition involving rapid variation in the sense of Definition 4.1).

(I)

(II)

In particular, if

(III)

Proof. With the position in (7.44)

already knowing, by Proposition 2.2, that

We have used the assumption “

For

where the indexes in the sum are subject to the restrictions specified in (7.45) plus condition

with suitable constants

and

and relations in (7.56) are proved for part (I). For the claim in (II) the situation is different as all the terms have the same growth-order. Expressing

For

And so we get

From (7.45) we get:

and it remains the task of proving that

For

Replacing into the sum we get

,

The restriction

It remains to look for some result about inversion. The simple example of

Proposition 7.7. (Inversion of a divergent function). (I) If

then the inverse function

(II)

(III)

Proof. Part (I) follows from Proposition 7.1 and (7.12). In this proof notations

For

i.e.

its exact value being determined by Proposition 2.6 and the restrictions in (7.69). From formula (6.4):

with suitable coefficients

wherein, by (6.5):

Hence we have:

for some constant

where x must be replaced by

which, by Proposition 4.1, states that

with a suitable constant

Applying the preceding results to

Proposition 7.8. (Inversion of an infinitesimal function). If f is a continuous strictly decreasing function on

Moreover the following inferences hold true:

8. Concepts Related to Exponential Variation

Whereas the study of the asymptotic behavior as

8.1. The Three Concepts of Exponential Variation and Basic Properties

Definition 8.1. If

For brevity we use the symbol

studying separately the properties in the four cases:

-Typical hypoexponentially-varying functions are:

and any regularly-varying function obviously belongs to the class

-All the exponentially-varying functions have the following structure:

as trivially follows from

-Typical hyperexponentially-varying functions are:

Any exponentially-varying or hyperexponentially-varying function obviously is rapidly varying but there are rapidly-varying functions which are hypoexponentially varying, as in (8.3).

Proposition 8.1. (Basic properties of hypoexponentially-varying functions). For

(i) An integral representation of type:

(ii) The asymptotic estimates:

(iii) The asymptotic functional equation:

and in particular:

(More precise asymptotic functional equations cannot be proved for a generic

(iv) The asymptotic relations involving anti-derivatives:

which state that, in the respective cases, either

(v) The asymptotic functional equations involving integrals of

Compare with (5.10) for similar relations where

Proof. Representation in (8.7) follows from (2.12) and

because for each

whence

The two relations in (8.12) are proved by direct application of L’Hospital’s rule with a preliminary remark for the second relation. The assumptions are “

A proof of the special case of (8.15), “

Proposition 8.2. (Basic properties of exponentially-varying functions). For

(i) An integral representation of type:

(ii) The asymptotic estimates:

(iii) The asymptotic functional equations:

and in particular:

(iv) The asymptotic relations involving antiderivatives:

which state that, in the respective cases, either

(v) The asymptotic functional equations involving integrals of

It follows from the above relations that the four functions

have the same order of growth as

Proof. Representation in (8.20) follows from (2.12), putting

whence relations in (8.23)-(8.25) follow. Relations in (8.27) are simply proved by L’Hospital’s rule and those in (8.28) either by L’Hospital’s rule and (8.25) or, directly, by (8.25) applied to a suitable antiderivative of f. To prove (8.29) just notice that either

In both cases L’Hospital’s rule may be applied:

,

Proposition 8.3. (Basic properties of hyperexponentially-varying functions). We are using the notation

(II) If

Proof. (I) Estimate in (8.37) follows from (8.35) by writing

relations in (8.38) follow from the identity “

or also from L’Hospital’s rule:

by the second relation in (8.38). Strangely enough any elementary attempt to prove the third relation in (8.41) failed and we report a proof under the restriction “f convex”; in this case we have at disposal the elementary inequality ( [10] , p. 15):

Analogous procedures for the relations in (8.42) and for the claims in part (II) up to (8.48). For those in (8.49), putting

Analogously for (8.50). ,

The values of the following limit are contained in the foregoing three propositions:

interchanging the values “0” and “

As a simple but meaningful application of the preceding functional equations consider a function of the type “

8.2. Higher-Order Exponential Variation

The right concepts of higher-order types of exponential variation are a consequence of some simple relationships between the types of exponential variation of

Proposition 8.4. (Types of exponential variation for a derivative). Let

Then: “

It follows that, whenever “

Proof. If

If “

and we shall show that “

Examples for

as, in this last case,

Definition 8.2. If

iff all the functions

wherein the correct index “

According to our agreements, an

The above definition excludes the circumstance that:

Using (8.62) it is immediately proved that (8.72) occurs iff there exists a polynomial

We shall not give this class a special name.

Proposition 8.5. (Relationships between higher-order exponentiality and higher-order rapid variation in the strong restricted sense). If

(I) If

implying that

(II) If

Proof. (I) Relations in (8.74) are stronger that those in (4.6), Definition 4.1, and imply those in (4.8) with

which are stronger that those in (4.6) and the assertion again follows from Proposition 4.1. ,

9. Operations with Higher-Order Exponentially-Varying Functions

Rules governing multiplication and composition of functions of the above classes can be proved; the results are not obvious a priori and restrictions on the indexes may be necessary. Some cases would remain completely undecided due to the intrinsic nature of two classes:

Proposition 9.1. (Product). (I) Results for variation of order 1. If

provided that the quantities

(II) Results for variation of order

Proof. It is enough to prove the claims about the product only for

For part (II) we separate three cases: “

and the thesis follows from (8.69). In case “

which do not grant that “

and “

In the third case, for

wherein the last but one equality is legitimate by the fact that the two products

If “

If “

whence:

having used once again (8.68) and Leibniz’s formula to obtain the last equality. ,

For inversion there is no special result: we can only assert that an

Proposition 9.2. (Composition: order 1). Let the functions

(I) If

then

The positive part of the statement is examplified by:

(II) If

then

If

defines an extended real number, then

There is no definite result for the excluded cases. A counterexample for “

the index of exponential variation depending on the value of “

(III) If both functions are exponentially varying with various indexes, namely

then

each of them in the role either of H or f. In both cases:

Proof. For part (I) write

and use “

recalling that “

because the first limit is

Proposition 9.3. (Composition: order 2). Let the functions

(I) Let

and both the products “

For the special case

and f as in (9.23) we have that:

In particular:

(II) If

then:

If

defines an extended real number, then

(III) If both functions are exponentially varying, namely

then

Proof. By Proposition 9.2 we need to estimate the behavior of the sole ratio

For part (I) we use the last expression in (9.31) trivially checking that:

whereas for the remaining cases wherein “

taking account that:

as well as the corresponding results for

Now let

,

Proposition 9.4. (Composition: order

(I) (H regularly or rapidly varying). If

then:

and these relations imply:

If

and

then in each of the four cases we have:

and these relations imply: either

For the special choice

and if

If

then:

whence:

If

then:

whence:

(II) (H exponentially varying, f smoothly varying of positive index). Assume

If

then:

which implies

wherein

If

then:

which implies:

If

(III) (H exponentially varying, f slowly varying). Notwithstanding the counterexample in (9.19) some positive results can be given for

Condition

wherein the last relation follows from “

with some constants

wherein “

This example also shows that, if

(IV) (Both

Case:

Case:

Relations in (9.63) coincide with the first group of relations in (9.47) obtained under the assumption for H in (9.46) which is independent of the present assumption “

In each case it is checked that “

that is “

For “

Proof. Remember that all the claims are already known for order 1 and that, in each single case, one has to replace the appropriate asymptotic relations into the Faà Di Bruno’s formula for

always taking into account restrictions in (6.2) and that all the coefficients

Part (I). Under conditions in (9.37),

whence

Let us now consider the family of polynomials:

where, by (6.2),

This, together with the value

wherein the coefficients

and quite similar calculations as above yield:

having used the obvious equality:

and we get:

and the analogous relation in case

Analogous procedure in case

Instead of (9.69) we now get:

taking into account the fact that into the summation the term with the highest growth-order is the one term corresponding to “

Under conditions in (9.46) we use (9.75) and the scale in (9.79) so getting:

which yield the same relations as in (9.81).

Part (II). The common relations for H are:

If (9.49) holds true then:

wherein

Under condition in (9.52), we use relations in (9.75) for

Part (III). Under assumptions in (9.54), we have the following relations for

with suitable nonzero coefficients

where the sum is some number which may have any sign including zero. This is (9.56). In the third case condition “

Part (IV). If

wherein the leading term is the one corresponding to

wherein the leading term is, once again, the one corresponding to

If

and (9.62) follows. If

that is (9.63). ,

10. Two Simple Applications of Exponential Variation

10.1. Relations between the Integral of a Product and the Product of Integrals

From elementary calculus we know that, generally speaking, an integral of type

Proposition 10.1. Let

(I) In the case “

(II) Under the assumptions “

(III) For

Proof. By L’Hospital’s rule we have:

and then we apply the various results in Propositions 8.1-8.3. The last claims in (10.1) and (10.2) simply follow noticing that the two limits on the right-hand sides in (10.5) are not smaller than the limits of the sole ratios involving f. Part (III) follows from Proposition 2.4-(I). ,

For

and a similar one for

Proposition 10.2. Let each of the two functions

(I) In the case “

(II) Under the assumptions: “

Proof. Again by L’Hospital’s rule:

,

10.2. Sums of Exponentially-Varying Terms

If

Proposition 10.3. For

together with the following asymptotic comparisons between sums and integrals.

(I) If

then:

If

then:

In the particular case “

(II) If

(III) If

then:

Proof. (I) Under conditions in (10.11) it follows from (8.14) that:

and the analogous relation in case of convergence. Under conditions in (10.14) we get from (8.15):

and the analogous relation in case of convergence. And also the equivalence in (10.10) is proved.

(II) From (8.29) we get:

and the analogous relation in case of convergence. (III) For “

whence:

Analogously for

whence:

The equivalence in (10.10) in cases (II) and (III) is implicit in the previous relations. ,

Remarks. 1. Condition “

2. The equivalence in (10.10) for the case

or from the inverted ones. Another classical criterion grants the equivalence in (10.10) under conditions “

3. The mentioned original proofs by Hardy for

Comments and examples on applying the foregoing results. Suppose that the asymptotic behavior of the given sequence

separating the cases of convergence and divergence. If the expansion has the simpler form “

Example 1. For “

In the first procedure we put

Example 2. For “

The sole relation “

Example 3. For

And the same argument can be used to establish the relation:

Example 4. Let

To evaluate

it can be checked that:

Hence for

for:

which is a remarkable relation due to the presence of the possibly oscillatory term

11. Asymptotic Expansions for

In iterative processes aiming at determining the asymptotic behavior of solutions of a functional equation it is sometimes useful to know asymptotic expansions of a quantity like

from a different viewpoint than that in §5. If

Lemma 11.1. (I) If

without any restrictions on sign and monotonicity of

(II) Relation in (11.1) holds true under the following conditions:

which means that, no matter what the growth-order of

Proof. Using the first equality in (5.20) all claims in part (I) reduce to proving that either

and all the assumptions on

,

Simple counterexamples show the necessity of the restrictions on r in (11.6); in fact, even if

Various types of expansions for

Proposition 11.2. (Higher-order regular or rapid variation). (I) If

and the following asymptotic expansion of Poincaré’s type holds true:

If

(II) If

In part (I) the sign of r may be arbitrary. The result in part (II) shows another context wherein our concept of higher-order rapid variation reveals appropriate: the hypothesis “

Proposition 11.3. (Higher-order hypoexponentiality). (I) If

where

(II) If

which may be thought of as an asymptotic expansion either of Poincaré’s type with respect to the asymptotic scale

and, under the additional assumption of monotonicity for

inverting the estimates for

Proofs. The common formula for the various claims is Taylor’s formula with initial point x and Lagrange remainder:

For the claim in Proposition 11.2-(I), we start from formula (3.5): “

and this, because of condition

In any case (11.9) holds true. For the remainder we know that there exists a number

whence (11.10) and (11.11) follow. For part (II) in Proposition 11.2, the assumption is that

and

for

Applying Lemma 11.1-(II) to the three quantities on the right and using the monotonicity of

whence (11.11). For part (I) in Proposition 11.3 we have

whence (11.12) follows. Under the monotonicity assumption we have

and (11.13) follows. The proof for (11.14) is quite the same: relations in (11.25) still hold true and the quantity

We now briefly examine to what extent the powers

Proposition 11.4. (Different arrangements in the expansion of

or

then the asymptotic expansion in (11.14) can be rewritten as the new expansion:

where all the terms, in the given order and with no grouping inside each sum, form an asymptotic scale at

Example. For all

satisfies the conditions in (11.27), and also the conditions in (11.28) with respect to

Proof. The chain

Now, if

As above we see that conditions in (11.32) are satisfied for

If

,

For an exponentially-varying f a possible expansion with more than one term must be of a different type as the n-tuple

Proposition 11.5. (Higher-order exponentiality). Let

If

For

which is directly obtained from (8.26) and the decomposition

12. Conclusions and Open Problems

As cursorily stated in the general introduction to this two-part paper in §1, our job consisted in: first, collecting all almost elementary and standard material about basic properties of regularly-, rapidly- and exponentially-varying functions; second, giving appropriate definitions for higher-order types of asymptotic variation; third, exhibiting several characterizations of higher-order smooth and rapid variation and highlighting the role of a lemma by Balkema, Geluk and de Haan about smooth variation, a role somewhat hidden in the original concise proof. Afterwards, a great deal of work has been required to prove complete results concerning the possible types of asymptotic variation for functions obtained by means of algebraic operations; in so doing much of the material in the previous sections have been used including (seemingly) futile remarks and (seemingly) minor results. On the contrary §5 on asymptotic functional equations is expository in nature its only merit being that of collecting in a systematized way as many such equations as possible. And the same can be said for such types of equations satisfied by exponentially-varying functions and grouped in §8.

All the material in both parts of the paper must be considered as the systematized general theory of higher-order asymptotic variation including the few simple applications in §§10,11. A (here again) semi-expository paper on the applications of such a theory should collect known and new results about asymptotic expansions of parameter-dependent integrals and sums, solutions of differential-functional equations, implicit functions and so on. But this requires a separate long effort.

We end by pointing out a few open problems in the just developed theory.

Open Problem 1. About the limit

-If “

-If “

either “

-If “

-But if “

Open Problem 2. Provide a proof for the third relation both in (8.41) and in (8.42) without the restriction “f convex”, or exhibit a counterexample.

Open Problem 3. A counterexample to monotonicity condition in Lemma 11.1:

Find a pair of functions (f, r) satisfying all conditions in (11.6) except monotonicity such that (11.1) does not hold true.

Open Problem 4. The first sentence after (9.11), concerning the inversion of a function with a definite type of exponential variation is in fact inaccurate; for instance, if the index of exponential variation is a real nonzero number c, then the principal part of the inverse is 1/c times a logarithm and something can be said about higher-order variation of the inverse. Find results for each extended real number c.

Cite this paper

Granata, A. (2016) The Theory of Higher-Order Types of Asymp- totic Variation for Differentiable Functions. Part II: Algebraic Operations and Types of Exponential Variation. Advances in Pure Mathematics, 6, 817-867. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2016.612064

References

- 1. Granata, A. (2016) The Theory of Higher-Order Types of Asymptotic Variation for Differentiable Functions. Part I: Higher-Order Regular, Smooth and Rapid Variation. Advances in Pure Mathematics, 6,

- 2. Bourbaki, N. (1976) Fonctions d’une Variable Réelle-Théorie élémentaire. Hermann, Paris.

- 3. Comtet, L. (1974) Advanced Combinatorics—The Art of Finite and Infinite Expansions. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht.

- 4. Ostrowski, A. (1973) Solution of Equations in Euclidean and Banach Spaces. Academic Press, New York and London.

- 5. Johnson, W.P. (2002) Combinatorics of Higher Derivatives of Inverses. American Mathematical Monthly, 109, 273-277.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2695356 - 6. Balkema A.A., Geluk J.L. and de Haan L. (1979) An Extension of Karamata’s Tauberian Theorem and Its Connection with Complementary Convex Functions. The Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, Oxford University Press, Series 2, 30, 385-416.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qmath/30.4.385 - 7. Bingham N.H., Goldie C.M. and Teugels J.L. (1987) Regular Variation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511721434 - 8. Hardy, G.H. (1924) Orders of Infinity—The “Infinitär Calcül” of Paul Du Bois-Reymond. 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- 9. Dieudonné, J. (1968) Calcul Infinitésimal. Hermann, Paris.

- 10. Roberts, A.W. and Varberg, D.E. (1973) Convex Functions. Academic Press, New York-San Francisco-London.

- 11. Mitrinović, D.S. (in cooperation with) Vasić, P.M. (1970) Analytic Inequalities. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York.

- 12. Mitrinović, D.S., Pećarić, J.E. and Fink, A.M. (1993) Classical and New Inequalities in Analysis. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht-Boston-London.

- 13. Erdélyi, A. (1961) General Asymptotic Expansions of Laplace Integrals. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 7, 1-20.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00250746 - 14. Erdélyi, A. and Wyman, M. (1963) The Asymptotic Evaluation of Certain Integrals. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis, 14, 217-260.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00250704