Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science

Vol.4 No.4(2014), Article ID:45309,11 pages DOI:10.4236/jbbs.2014.44021

The Underlying Reasons of Suicide Attempts among Arab Population in the Holy-Land— Nazareth: View and Overview

Elia Haj, Eisa Hag, Riad Hanna, Farhat Kamal, Bisharat Bishara, Bowirrat Abdalla*

EMMS Nazareth Hospital, Faculty of Medicine in the Galilee, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

Email: *bowirrat@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 7 March 2014; revised 11 April 2014; accepted 19 April 2014

ABSTRACT

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death in many western countries, but in eastern countries this phenomenon was until recently extremely rare. Our study, performed during 2005-2012 comes to shed lights on the prevalence and the underlying reasons of the notable increase of suicide attempts in the conservative and religious Arab community of Nazareth, Israel. Extensive interviews, sociodemographic information, suicide risk factors in addition to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) diagnoses were used in current retrospective study of 772 suicide attempters in the emergency room at the Nazareth Hospital. Statistical analysis using SPSS version 17, Pearson χ2 analysis and percentage distribution were used for the statistical analysis. We considered the differences to be significant at the level of p < 0.05. Three fold frequency of suicide attempts were observed among females (77%) compared to males (23%), (P = 0.0001). During the year 2009 the suicide attempts prevalence was the highest 118 (15.3%) and during 2005 it was the lowest 77 (10%). 76.5% of the attempters arrived to the emergency room within 1 - 6 hours. A single suicide attempt was observed among 60% of males compared to 70.5% among females [OR = 0.846 (CI: 0.742 - 0.966)] additionally, more than one suicide attempt was notified among 40% of males whereas 29.5% among females [OR = 1.367 (CI: 1.099 - 1.701), (P = 0.007)]. Psychiatric patients (59.3%) performed more than one suicide attempt compared to normal subjects (21.5%), [OR = 2.76; CI: 2.276 - 3.354, P-value = 0.0001]. Drugs was preferred for suicide attempts in both genders (87.7%), especially among females compared to males (90.6% vs. 78.8% respectively), [OR = 0.869; CI: 0.801 - 0.942, P = 0.001]. 38 of males (21.3%) committed suicide attempts by causing accidents and self harm compared to 56 females (9.4%); [OR = 2.261; CI: 1.552 - 3.294, (P = 0.0001)]. 40 psychiatric patients (18.7%) chose this method compared to 54 non-psychiatric patients (9.7%), [OR = 1.925; CI: 1.32 - 2.806, P-value = 0.001]. The underlying causes of suicide were as follows: 50% social causes, 26% adjustment reactions and 24% psychiatric diseases. Conclusion: Being the first unique study to shed lights on the increasing phenomenon of suicide in the Arab community, our findings unveiled a tragic transition in the rate of suicide attempts in a supposedly conservative and religious community. Even though the rate of suicide attempts is lower than other communities it should not divert focus away from efforts to develop effective strategies to prevent suicide attempts, especially among females.

Keywords:Suicidal Behaviour, Holly Land, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Prevention Strategy

1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed widespread public concern over the alarming rate of suicide and suicidal thoughts worldwide, which constitute a significant burden on communities and health system especially among youth. Historically, frequency of suicidal behaviors, values and attitudes toward suicidal behaviors, has varied widely across populations. Tradition, religious and social principles play some roles in this regard [1] -[4] .

Suicidal behavior is complex and is a fatal reaction to a potentially preventable public health catastrophe. Some risk factors vary with age, gender and ethnic group and may even change over time. The risk factors for suicide frequently occur in the combination of external factors and internal chemistry [5] .

The reasons that lead a person to commit suicide are as numerous and complex as the thousands of people who do so every year. Attempts of suicide, and suicidal thoughts or feelings are usually a symptom indicating that a person isn’t coping, often as a result of some events or series of events or unbearable psychological pain, hopelessness, helplessness and sense of worthlessness that they personally find overwhelmingly traumatic or distressing. Indeed, suicide may be a result of a conflict between fantasy and reality. When our life expectations roof is high, inevitably our disappointments roof will be high also. In fact, our expectations are in a covariant relation with our disappointments, hence the gap between expectations and the failures of implementation of achievements has a negative psychological impact on the person’s personality. He/she feels betrayed by himself/herself; consequently his/her self-esteem breaks down. Altogether with his/her inability to confront the reality, by carrying the overloaded life responsibilities with a well-merited manner, he/she resorts to get rid of these feelings by committing suicide.

On the other hand, dissatisfaction and failure yield to fatalism, rejecting facing the truth and the lack of rationality, wisdom and patience which are required to deal with adversity and hardship leave the victim helpless, hopeless and lost, which lead him/her to suicide. It seems that suicide has external causes and internal ones [6] -[8] .

The most common external causes or most accurately, external catalysts of suicidal behavior are bullying, peer pressure/incidents, family crises and health problems. Usually these are situational in nature and have an escalating history that has led the individual to feel as if they have no other way out. When external forces become unbearable enough for a person to contemplate, suicide depression and desperation of some sort are always involved. On one hand, the depression causes the individual to make irrational decisions based on unstable emotions [9] .

On the other hand, the internal causes of suicidal behavior are much more complex and harder for the average person to perceive than external causes. Essentially all suicide attempts come down to something inside the suicidal person, but those without external catalysts are often biological in nature [10] .

Severe depression, which is believed to be caused by a combination of external factors and internal chemistry, is one thing that almost every suicide or suicide attempt has in common, and how that depression came to be is the only difference. Some people suffer from depression because of chemical imbalances, whilst to outsiders their lives seem great, or at the very least average, with nothing outstanding that would indicate a reason want to die. While internal suicidal triggers are harder to see from the outside, the warning signs are usually present regardless of whether an attempt is situational/reactionary or psychological in nature. Suicide attempts brought on by a psychological disorder are more likely to be successful at the first try. They are often planned and thought out over a period of time, when the suicidal person normally makes gestures seeking closure with those closest to them shortly beforehand. The most common internal causes of suicide or suicidal behavior are clinical depression, psychiatric disorders or chemical imbalances [9] [11] .

Researchers have revealed that more than 90 percents of individuals who murder themselves have psychiatric and mental illnesses or drug abuse’s disorder [12] . In addition, research points out that modification in the chemical neurotransmitters in the brain are associated with the increase risk for suicide and suicide behavior. Reduced concentrations of neurotransmitters in the brain such as Serotonin have been found in patients with severe depression, impulsive-compulsive disorders, a history of violent suicide attempts, and also in postmortem brains of suicide victims [13] -[16] .

Unfavorable life proceedings and events, in combination with psychiatric disorders such as depression, may guide to suicide. However, suicide and suicidal thoughts are not natural reactions to stress. Countless individuals have one or more risk factors which are not suicidal. In fact, it depends on the strengths and on the rationality of these people. Arrays of risk factors, parts known and other still unknown may underlie the suicide and suicide behaviors: prior suicide experience, family history of mental illnesses or drug addiction, family violence accompanied with history of suicide, sexual abuse, and exposure to the suicidal behavior of others, including relatives, peers, internet, film and television portrayals of suicides or even in the media [17] .

In our era, more adults lose their life from suicide than from all the leading natural causes of death combined, including chronic diseases, cancer, immunodeficiency syndrome, malformations, genetic diseases, and congenital defects, making suicide the tenth leading causes of death for all ages in 2010 [18] .

There were 38,364 suicides in 2010 in the United States—an average of 105 each day [19] .

Suicide accounts for 1.5% of the global burden of disease, which represents 20 million years of healthy life lost due to premature death or disability [20] .

Based on data about suicides in 16 National Violent Death Reporting System states in 2009, 33.3% of suicide decedents tested positive for alcohol, 23% for antidepressants, and 20.8% for opiates, including heroin and prescription pain killers [21] .

Suicide among males is four times higher than that among females and represents 79% of all U.S. suicides and females are more likely than males to have had suicidal thoughts. Firearms are the most commonly used method of suicide among males (56%) and poisoning is the most common method of suicide for females (37.4%) [22] .

Indeed, suicide attempts are much more common than completed suicides; as many as 150 youths attempt suicide for every completed suicide [23] .

A previous suicide attempt is considered as a leading risk factor for completing a suicide. Moreover, suicide attempts, regardless of whether they are completed or not, impose real health care and other costs [24] .

Whereas a plethora of studies have described the specific characteristics of patients who have committed suicide while in the hospital, or analyzed environmental factors relevant to inpatient suicides or suicide attempts [25] , and this study comes to shed lights on the prevalence and on the underlying reasons of notable increase of suicide attempts in the community in general, and in the emergency room in specific, by examining the sociodemographic and medical predictors of attempted suicide in a large population-based sample from Nazareth in northern Israel.

Although, the wish to die is not uncommon among people with depression in Arab cultures, it usually remains at the level of wishing that God would terminate their life, and does not progress to the wish to kill themselves [26] .

Indeed, suicide attempts, characteristics of suicidal and related behaviors differ from other cultures; we react negatively to any suicidal attempts, because this phenomenon is religiously unacceptable whatever the vulnerability and precipitating factors underlying this abnormal act which is against the values of our religion and tradition. Indeed, person who commits a suicide is considered as a traitor to religious values and principles and this prevents him the usual religious rites.

In recent years like everywhere else in the world, suicide attempts in Israeli Arabs have been increasing progressively. The dramatic increase in suicide attempts recently notified in this relatively religious community makes the identification of significant risk factors a matter of public health importance. Therefore, all the suicidal attempts must be taken sincerely and treated accordingly and should be given high priority and never be ignored as simply cries for attention. Improving the understanding of suicide risk assists in the identification of vulnerable individuals as well as in the development of effective strategies to prevent suicide.

2. Methods

Extensive clinical interviews, sociodemographic information, risk factors that predispose suicidal behavior, such as personality disorders, mental disorders and psychosocial factors, such as traumatic life events, unemployment and drug misuse in addition to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) diagnoses were used in current retrospective study of 772 suicide attempters (594 females and 178 males aged from 12 to 82 years, mean age 28.29, SD 11.39) presenting to the emergency services at EMMS Nazareth Hospital (The largest Arab hospital in the Galilee) in the north of Israel from January 2005 to December 2012. Statistical analysis using SPSS version 17, Pearson χ2 analysis and percentage distribution were used for the statistical analysis. The means were displayed with standard deviations. We compared groups on demographic and clinical characteristics using analyses of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests. We also considered the differences to be significant at the level of p < 0.05. The hypotheses were established as two-sided.

3. Results

Overwhelmingly, people who choose to end their lives because of feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness and unbearable psychosocial distress were hopeless they would ever improve.

Arrays of risk factors for making a suicide attempt were examined in this Arab community. Despite the high rate of religiosity and faith that prevail in our society that could deter and prevent suicide attempters from completing their destination, unfortunately the rate of suicide attempters seems to increase considerably. In the current article we discuss the rates of suicide in hospital, related risk factors, and methods of suicidal behavior, and factors which contribute to this tragic event.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the survey participants with the weighted distributions of the sociodemographic characteristics and the number and prevalence of suicide attempt according to the day of the week and month of the year. The total number of the suicide attempters in the study (n = 772); males (n = 178, 23%) and females (n = 594, 77%). Mean age 28.29 ± 11.39; minimum age = 12 years and maximum age = 82 years. We observed a threefold frequency of suicide attempts among females (77%) comparing to males (23%), (p = 0.0001). Age stratification was as follow: 12 - 18 years (n = 161, 21%); 19 - 30 years (n = 326, 42%); 31 - 50 years (n = 258, 33%) and older than 51 years (n = 27, 4%). The prevalence of suicide was more notified in urban location (63%) comparing to rural (37%). We observed a lowest frequency in suicide attempts during the Christians and the Muslims holydays [(Sundays—85 attempts (11%) vs. Fridays—99 (12.8%), respectively]. and a highest frequency of suicide attempts were during Mondays (n = 126, 16.3%). In the other hand, we observed a lowest frequency of suicide attempts during January and February (n = 51, 6.6%) vs. (n = 50, 6.5%) respectively. The highest frequency was found during spring months especially Aprils (n = 79, 10.2%).

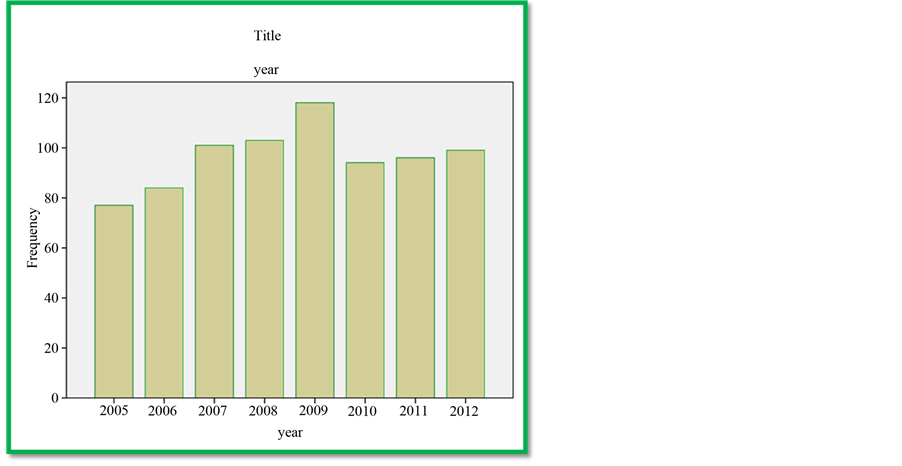

Table 2 describes the distribution of suicidal attempts during the period 2005-2012 which were various according to the year. We clearly notified that during the year 2009 the suicide attempts were highest comparing to suicide frequency during 2005; 118 subjects (15.3%) versus 77 attempters (10%), respectively.

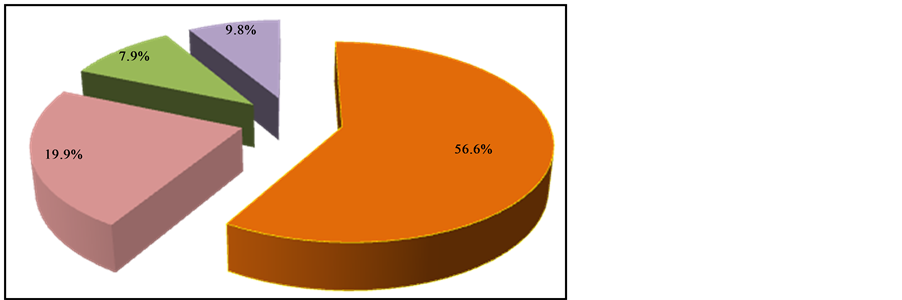

Table 3 shows the time in hours elapsed from the suicide attempt until the access to the Emergency Department. We notified that the majority of attempters [436/772 (56.6%)] arrived within 1 - 2 hours to the emergency department, and the rest arrived between 3 - 24 hours, but only a minority (45 attempters) arrived after 24 hours.

Table 4 shows the comparison between the two genders according to the suicide attempts frequency number. The first time suicide attempt among males was lower than females first time attempt (60% vs. 70.5% respectively), [OR = 0.846 (CI: 0.742 - 0.966)]. In contrary, the frequency of more than one time suicide attempts among males was higher than female’s second attempts (40% vs. 29.5% respectively); [OR = 1.367 (CI: 1.099 - 1.701)]. Both results were statistically significant (p = 0.007).

Table 5 Describes the frequency of suicide attempts among the psychiatric patients and non-psychiatric patients. Only 87 psychiatric patients (40.7%) performed first time suicide attempts comparing to healthy subjects (n = 435, 78.5%); [OR = 0.518, CI: 0.438 - 0.612]. 127 psychiatric patients’ (59.3%) performed more than one suicide attempt comparing to normal subjects [OR = 2.76; CI: 2.276 - 3.354, P-value = 0.0001].

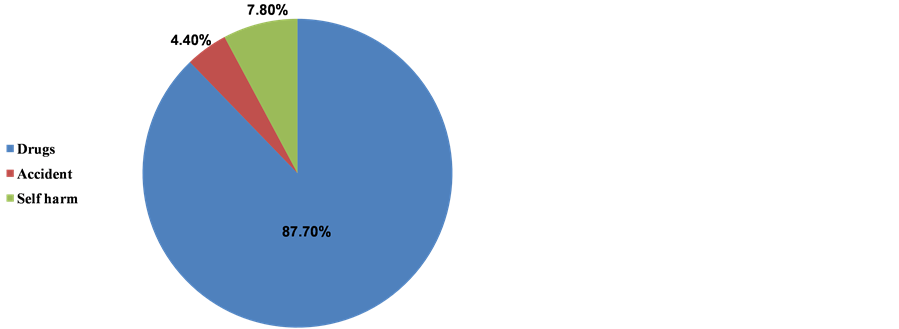

Table 6 shows the manner utilized to perform the suicide attempt. We observed that drugs occupied the first line method for suicide attempts in both gender (87.7%), and was the preferred methods among females comparing to males (90.6% vs. 78.8% respectively, p = 0.001). The second used method was self harm which represents 7.8%, and the latest preferred method was different accident (4.4%).

Table 7 shows comparison between the two genders according to the way of the suicide attempt mode used. This table shows that 38 males subjects (21.3%) committed suicide attempts by causing accidents and self harm comparing to 56 females (9.4%) who used the same methods [OR = 2.261; CI: 1.552 - 3.294]. In other hand, we

Table 1. Sociodemographic and suicide attempts characteristics of the Survey of Arab community in Nazareth.

observed that the preferred way for female suicide attempt is using drugs. In fact, 537 females (90.6%) comparing to 140 males (78.7%) used drugs for their suicide attempts [OR = 0.869; CI: 0.801 - 0.942, P-value = 0.0001].

Table 2. The distribution of suicidal attempts during the period (2005-2012).

Table 8. Patients with psychiatric diseases and non psychiatric diseases patients and the ways of suicide attempts used. This table shows that 40 psychiatric patients (18.7%) choose the Accident and self harm mode for their suicide attempts comparing to 54 non psychiatric patients (9.7%) who do not used this method [OR = 1.925; CI: 1.32 - 2.806, P-value = 0.001]. We also notified that suicide attempters without psychiatric diseases (n = 502, 90.3%) used other methods to commit suicide compared to psychiatric patients who preferred to use drugs (n = 174, 81.3%), [OR = 0.901; CI: 0.840 - 0.966].

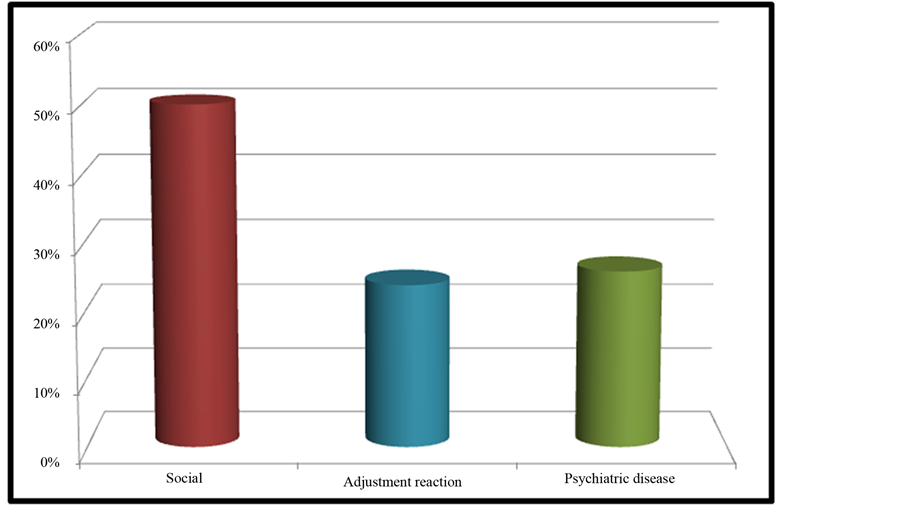

Figure 1 illustrates the significant causes of the suicide attempts according to their frequency in the community. The figure illustrates that the social problems such as (racism, crime, abortion, domestic violence, sex abuse, poverty, hunger, disease, drugs, alcoholism and unemployment) are the first underlying causes of suicide attempts in this community (50.2%), followed by psychiatric diseases such as depression represents the second leading cause of suicide attempts (25.8%), followed by adjustment reactions (24%), (an unexpectedly strong emotional or behavioral reaction that occurs in response to an identifiable stressful life event or life change that occurred within the previous three months).

4. Discussion

Life and spirit are donations of God to human beings; these awards have been bestowed to us in hope to be saved in sanctity.

Table 3. The time passed between the suicide attempt and the arrival to the emergency department.

Table 4. Comparison between the two genders according to the suicide attempts number.

Pearson chi—square 7.317; P-value = 0.007.

Table 5. Comparison between the psychiatric patients and non-psychiatric patients according to the number of suicide attempts.

Pearson chi—square; P-value = 0.000.

Suicide is a profoundly disquieting episode that challenges our suppositions about the meaning and merit of life and leaves a wake of pain and bewilderment among the families and friends of those who end their lives, not to mention the unexpected great pain, the huge and ominous shock in the society. There is no treatment for those

Table 6. The methods used for the suicide attempts.

Table 7. Comparison between the two genders according to the way of the suicide attempt mode used.

Pearson chi—square; P-value = 0.000.

Table 8. Psychiatric patients and non psychiatric patients and the ways of suicide attempts.

Pearson chi—square; P-value = 0.001.

who decide to end their lives. We know our intervention limitations, also we know that we cannot direct the wind but we can adjust the sails; our role and mission is to explain to the suicide attempters that life is worth living despite hardships and adversities. We should give them hope, motivation, empathy by expressing solidarity and support them by finding behavioral strategies that may prevent the repeating of this phenomenon.

Figure 1. Underlying causes of suicide attempts.

Suicide has been condemned in our culture under all the circumstances and reasons and in the past, suicide was a rare phenomenon in this Arab religious society, but in recent years, a wave of changes and transitions occurred in the Arab community related to the worldwide globalization, modernization and life complexity that reflected negatively on the society as a whole. Indeed, suicidal behavioral is a multi-factorial and complex episode of interacting personal and social circumstances. Suicide is just one indicator of distress in communities. Many underlying factors may contribute to suicide such as individual constitution, temperament, or developmental experiences, interpersonal relationships, alcohol and substance abuse, suicidal ideation and previous suicide attempts, and coexisting psychiatric disorders.

In 2000, suicide was the 8th leading cause of mortality among males and the 19th underlying cause of mortality among females [27] .

The mortality among males is more than four times as females die by suicide [28] , while females report attempting suicide during their lifetime about three times as often as males [29] .

Comparing the prevalence of suicide between Israeli Jews and Israeli Arab, the Israeli Jews were at more than a three-fold higher risk for having suicide reported on their death certificates, as compared to Arab (9.8 vs. 2.9 respectively) [30] . Despite the low rates of suicide among the Arab community in Israel compared to Jew community this rate is considered to be weird and abnormal in a society where suicide is denied religiously and morally unacceptable and considered to be a red line and extraordinary phenomenon. In other hand, the attempting suicide among females in our study was extremely brilliant and clear, and it was three times as often as males, which may related to the higher rates of depression [31] [32] .

Similar to previous studies, the rate of suicide behaviors is notably high among Arab women as the notably higher prevalence of attempted suicide among black women [33] .

In the Arab community the economic situation, adjustment reactions and social problems such as (poverty, hunger, racism, unemployment, deprivation, marginalization, powerlessness, stressful life event, anxiety disorders, domestic violence and substance abuse) reflect individual suffering or a wider social predicament and represent more than 75% of the total reasons of suicide attempts. Indeed, 53.2% of the Arab families live under the poverty line, mainly due to low employment rates among Arab women [34] .

The uncertain future, frustration and the lack of opportunities may threaten family stability and increase family violence—for this we note the high rates of the suicidal behaviour among females in our study (594/772; 77%).

Plethora and arrays of risk factors underlying suicide attempts worldwide are various according to communities. The leading cause and risk factors for completed suicide are previous suicide attempts which are the best predictors of an eventual completed suicide and are roughly corresponding to a 30% - 40% times increased risk of mortality for suicide compared with the general population [35] .

Hence, different intervention strategies are warranted to deal with these risk factors separately. In our community, the poverty, deprivation and unemployment should be politically treated and seriously tackled by decision makers, by strengthening the community economically and giving equal employment opportunities. In addition, the prevention of suicide attempts must therefore counteract frustration, hopelessness and unbearable pain in all of their toxic forms, and provide other means of changing or escaping intolerable circumstances. In this way, people will move with their families and communities from a position of marginalization, powerlessness, and pessimism to one of agency, creativity, self-confidence, and hope.

References

- Coleman, J.S. and Coleman, J.S. (1994) Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Marsella, A. and Yamada, A. (2000) Culture and Mental Health: An Introduction and Overview of Foundations, Concepts, and Issues. In: Cuellar, I. and Paniagua, F., Eds., Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health, Academic Press, San Diego, 3-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-012199370-2/50002-X

- Goldston, D.B., Molock, S.D., Whitbeck, L.B., et al. (2008) Cultural Considerations in Adolescent Suicide Prevention and Psychosocial Treatment NIHPA. American Psychologist, 63, 14-31.

- Minois, G. (1999) History of Suicide: Voluntary Death in Western Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Spirito, A. and Esposito-Smythers, C. (2006) Attempted and Completed Suicide in Adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 237-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323

- Barclay, D.J. (1965) Durkheim’s One Cause of Suicide. American Sociological Review, 30, 875-886. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2090966

- Windfuhr, K. and Kapur, N. (2011) International Perspectives on the Epidemiology and Aetiology of Suicide and Self-Harm. In: O’Connor, R., Platt, S. and Gordon, J., Eds., The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention. Wiley Blackwell, West Sussex, 27-57.

- O’Carroll, P., Berman, A., Maris, R., Moscicki, E., Tanney, B. and Silverman, M. (1996) Beyond the Tower of Babel: A Nomenclature for Suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26, 237-252.

- Mehlum, L. (2001) Suicidal Behaviour and Personality Disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 14, 131-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001504-200103000-00006

- Everson, S.A., Goldberg, D.E., Kaplan, G.A., Cohen, R.D., Pukkala, E., Tuomilehto, J. and Salonen, J.T. (1996) Hopelessness and Risk of Mortality and Incidence of Myocardial Infarction and Cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58, 113-121.

- Beck, A.T. (1967) Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

- Kessler, R.C., Chiu, W.T., Demler, O. and Walters, E.E. (2005) Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of TwelveMonth DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617-627. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

- Dombrovski, A.Y., Siegle, G.J., Szanto, K., Clark, L., Reynolds, C.F. and Aizenstein, H. (2012) The Temptation of Suicide: Striatal Gray Matter, Discounting of Delayed Rewards, and Suicide Attempts in Late-Life Depression. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1203-1215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002133

- Moscicki, E.K. (2001) Epidemiology of Completed and Attempted Suicide: Toward a Framework for Prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1, 310-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1566-2772(01)00032-9

- Conwell, Y. and Brent, D. (1995) Suicide and Aging. Patterns of Psychiatric Diagnosis. International Psychogeriatrics, 7, 149-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1041610295001943

- Mann, J.J., Oquendo, M., Underwood, M.D. and Arango, V. (1999) The Neurobiology of Suicide Risk: A Review for the Clinician. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60, 7-11.

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M. and Herberth, A. (2010) Role of Media Reports in Completed and Prevented Suicide: Werther v. Papageno Effects. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 234-243.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2010) Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Milligan, K. (2013) Cognitive Distortions as a Mediator between Early Maladaptive Schema and Hopelessness. PCOM Psychology Dissertations, Paper 256. http://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/psychology_dissertations/256.

- Mann, J.J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., et al. (2005) Suicide Prevention Strategies. JAMA, 294, 2064-2074. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- Karch, D.L., Logan, J., McDaniel, D., Parks, S. and Patel, N. (2012) Surveillance for Violent Deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 States, 2009. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 61, 1-43. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6106a1.htm?s_cid=ss6106a1_e#tab6

- Crosby, A.E., Han, B., Ortega, L.A., Parks, S.E. and Gfoerer, J. (2011) Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors among Adults Aged ≥18 Years—United States, 2008-2009. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 60, 1-22. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6013a1.htm?s_cid=ss6013a1

- Wagman, B.I., Ireland, M. and Resnick, M.D. (2001) Adolescent Suicide Attempts: Risks and Protectors. Pediatrics, 107, 485-493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.3.485

- Appelbaum, P.S. (1993) Legal Liability and Managed Care. American Psychologist, 48, 251-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.3.251

- Mills, P.D., King, L.A., Watts, B.V. and Hemphill, R.R. (2013) Inpatient Suicide on Mental Health Units in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals: Avoiding Environmental Hazards. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35, 528-536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.021

- Fakhr, el Islam, M. (2000) Social Psychiatry and the Impact of Religion. In: Okasha, A. and Maj, M., Eds., Images in Psychiatry: An Arab Perspective, World Psychiatric Association, WPA Publications, Cairo, 21-36.

- Miniño, A.M., Arias, E., Kochanek, K.D., Murphy, S.L. and Smith, B.L. (2002) Deaths: Final Data for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports, 50, 1-119.

- Weissman, M.M., Bland, R.C., Canino, G.J., et al. (1999) Prevalence of Suicide Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Nine Countries. Psychological Medicine, 29, 9-17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798007867

- Lubin, G., Glasser, S., Boyko, V. and Barell, V. (2001) Epidemiology of Suicide in Israel: A Nationwide Population Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36, 123-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001270050300

- Henriksson, M.M., Aro, H.M., Marttunen, M.J., Heikkinen, M.E., Isometsä, E.T., Kuoppasalmi, K.I. and Lönnqvist, J.K. (1993) Mental Disorders and Comorbidity in Suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 935-940.

- Baumeister, R.F. (1990) Suicide as Escape from Self. Psychological Review, 97, 90-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.97.1.90

- Joe, S., Baser, R.S., Neighbors, H.W., Caldwell, C.H. and Jackson, J.S. (2009) 12-Month and Lifetime Prevalence of Suicide Attempts among Black Adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 271-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf

- OECD (2013) Israel Is Poorest of All Developed Countries. The Jerusalem Post, 15 May 2013.

- Blumenfeld, O., Dichtiar, R. and Shohat, T. (2013) Trends in the Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Pediatric Diabetes, 1399-5448.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.