Open Journal of Business and Management

Vol.1 No.2(2013), Article ID:33841,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ojbm.2013.12004

Partnership Evaluation in Local Authorities in Spain

School of Economics and Business, University of Granada, Granada, Spain

Email: fmatias@ugr.es, victorj@ugr.es, msenise@ugr.es

Copyright © 2013 Fernando Matías-Reche et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received May 6, 2013; revised June 8, 2013; accepted June 17, 2013

Keywords: Partnership; Evaluation; Training

ABSTRACT

The current work aims to evaluate the partnerships of various local authorities in Spain. The work considers a number of theoretical approaches to partnership, and reports the results of a survey investigating the state of the partnerships that various local authorities have participated in to help improve training and access to the labour market for the unemployed. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to evaluate these partnerships. The main findings indicate that the main partner, the driving force behind the partnership, makes a more positive evaluation of the partnership than the minor partners, and that the partnership dimensions that are most valued and hence contribute most to the success of the partnership are Promotion of the involvement of collaborators and relevant outside institutions, and Basic elements and realism of the partnership, while the dimensions that are least valued are Emergence of a work network, and Evaluation and learning. We also find that satisfaction with the partnership is conditioned by the intensity of the collaboration.

1. Introduction

Forming institutional partnerships is an essential requirement for the effective delivery of services, both at the individual and group level. Thus, although partnerships have some disadvantages for the partners, such as the time spent on coordination, or the difficulty in understanding the other partners because of their different perspectives, the joint use of financial, material, human, technological and other resources helps the various participating institutions to achieve both their individual and joint goals more effectively and efficiently.

The current work aims to evaluate the partnerships that various local authorities in the province of Granada (Spain) have organised within the framework of the ACERCA III project, a programme that develops training and professional qualifications for groups of people, particularly women, in various rural localities in that province.

Specifically, the evaluation carried out here aims to:

• Understand the effectiveness of the partnerships, on the basis of the most important dimensions in the partnership process.

• Start the process whereby the state of the partnerships can be compared with previous situations, creating a database that can be used to determine the extent to which barriers are overcome or progress is made in the partnerships.

• Systematically identify areas of consensus and conflict, in other words, the strengths and weaknesses of the partnerships, so that a plan can be drawn up to improve the situation.

To achieve the above objectives, this work first carries out a literature review, and then establishes the conceptual framework within which this study can be placed. The following sections describe the empirical methodology used and the results obtained, and discuss the results. The work ends with the main conclusions and recommendations for improvement.

2. Partnership Evaluation and ACERCA III Project: Conceptual framework

ACERCA III is a project co-financed (70% of total) by the 2003-2004 round of the European Social Fund’s Global Subsidy for Objective 1 and Objective 3 regions, approved by the Directorate General for Local Administration of the Spanish Ministry for Public Administration. The ACERCA III project has three main aims:

• To promote employment and new entrepreneurial initiatives. The project provides people out of work with a theoretical qualification and professional experience to improve their chances of finding work or starting their own project. Rather than explicitly creating or maintaining jobs, the project could be said to improve people’s employability [1].

• Equal opportunities for men and women.

• To improve the competitiveness of the organisations in the project’s geographical area of reference. The promoters only considered this objective indirectly when they first designed the project. But the ACERCA III project has had some interesting consequences that will have repercussions for the competitiveness of organisations in this region.

The term partnership has been used to refer to any form of organisational affiliation, but [2] argue that partnership is more integrated. They locate partnership at the end of a continuum of the different ways that organisations can work together [3].

The literature on institutional partnership in three groups. The first group refers to the normative perspective [4-7]. This perspective was initially defended by supporters of NGOs, who see partnership as the ethically correct approach to sustainable development and delivery of services to society. But they criticise the role of the government and stress that the NGOs and civil society should have a larger role. Partnership is seen as an end in itself.

A second group of works describes partnership between institutions from a more enthusiastic perspective than the first group of works. These works argue for improving governments’ public relations aimed at civil society. This perspective is illustrated in some annual reports and programme documentation [8,9].

A third approach perceives partnership as a tool for achieving other objectives to do with efficiency, efficacy and responsibility [10-13]. This perspective has three lines of analysis. The first considers particular types of relationship and their objectives [14-16]. The second looks at the literature on business alliances [17,18]. The third considers network theory, political economy and the new governance models [19-21]. More specifically, this last line of analysis examines inter-organisational collaborative, incentive systems, control mechanisms and structural alternatives.

The current work follows this third line of analysis. Is consider that for the partnership to achieve the best results, it is necessary to identify how effective it has been, in other words, to evaluate it. Thus, evaluation should be understood as one more step in the partnership process, one that will provide feedback to the process to enable suitable modifications for its constant improvement.

3. Research Methodology

The current research on the state of the partnerships between the partners of the ACERCA III project requires information about each of the partners. A total of 12 partners participate in this project, along with the main partner, the Provincial Council of Granada. The population and sample are 13 partners and 12 partnerships (the partnerships between the Provincial Council of Granada and the other 12 partners and therefore, with regard to nature of the study, the sample is the total population). Partners of the Provincial Council are as follows:

• Sierra Nevada-Vega Sur Consortium (Consortium is an alternative name for Association of Municipalities);

• Alhama and Fardes Rivers Association of Municipalities;

• Alhama de Granada Association of Municipalities;

• Baza District Association of Municipalities;

• Guadix District Association of Municipalities;

• Huescar District Association of Municipalities;

• Lecrin Valley Association of Municipalities;

• Montes Orientales Development Consortium;

• Poniente Granadino Rural Development Consortium;

• Vega-Sierra Elvira Development Consortium;

• Sierra Nevada Development Consortium;

• Marquesado del Zenete Association of Municipalities.

Information about the Provincial Council’s partners, as well as all the necessary information about individuals, their contact telephone numbers and e-mail addresses, was provided by Provincial Council staff responsible for the ACERCA III project.

The procedure used to obtain the necessary information was to contact the people responsible for the project in each partner institution, and agree time and place for the structured interview. This interview was based on a semi-open questionnaire with closed-ended questions. The questionnaire asked the respondents in some cases to add comments.

Before the interview took place the questionnaire was sent by e-mail to the people responsible for responding to it to allow them to read the questionnaire at leisure and if necessary note down any aspects that they did not understand, or comments about the items, which they would be able to bring up in the interview. Most of the interviews took place on the established date and using the methodology previously described. In other cases, and after sending the questionnaire, is phoned the respondents to ensure they had received the questionnaire, clear up any doubts, and collect comments about the questionnaire. In these cases, the respondents then returned the questionnaires by e-mail or by post.

With regard to the Provincial Council, after the staff responsible for the project and the research group INVESPYME, from the University of Granada, had examined the questionnaire, it was agreed that these managers would respond to 12 questionnaires, one for each partner, in function of the relationship that the Provincial Council had had with it. The structure of the ACERCA III project leads to bilateral relationships between the Provincial Council and each minor partner, with the minor partners having very little relationship with each other. It was consequently not worthwhile examining the relationships between these partners in any great detail, unlike the relationships between the Provincial Council and each of the minor partners.

The questionnaire evaluating the partnerships between the partners was obtained from previous work carried out in the framework of the European Union [22-24], subsequently adapted to the particular conditions of the ACERCA III project. More specifically, is examined [25] and carried out an in-depth review of the academic and scientific literature (journals, books, presentations in congresses, etc.) on the evaluation of partnerships between institutional partners, in particular local partnerships [3, 26-29].

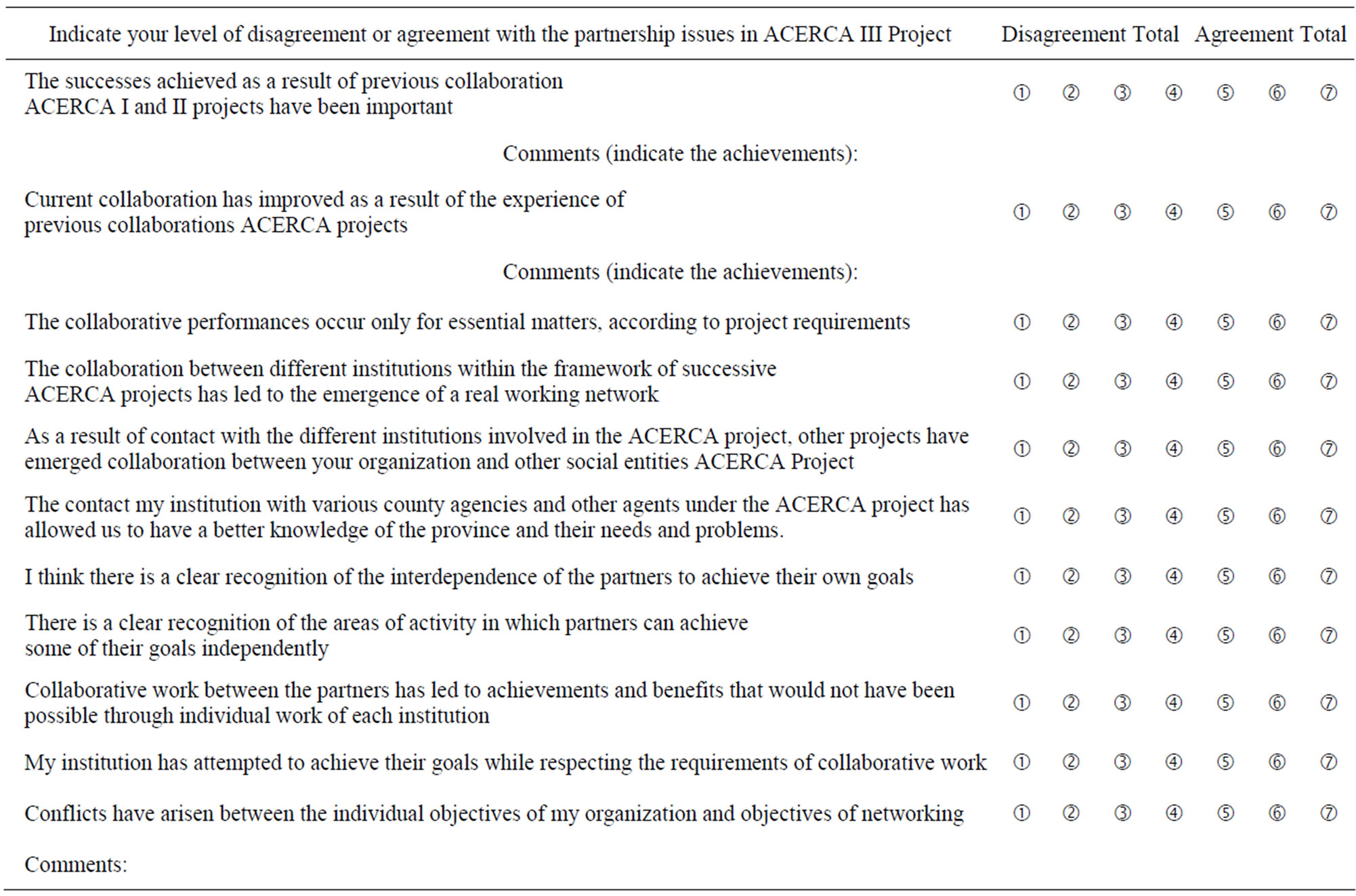

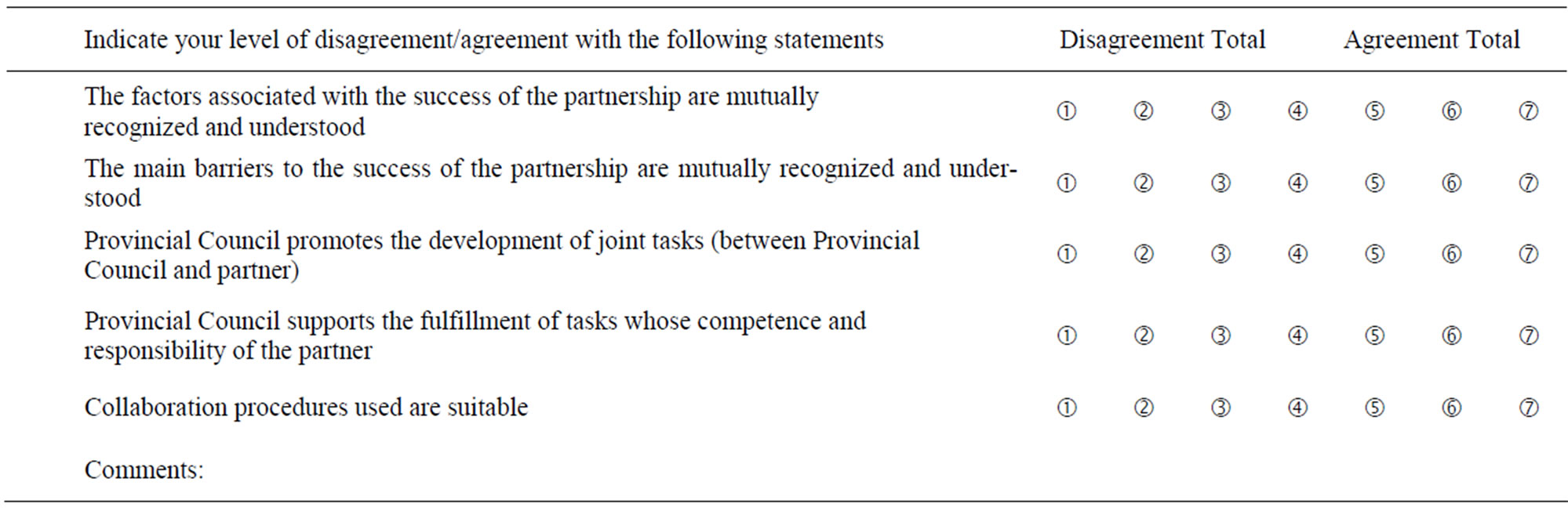

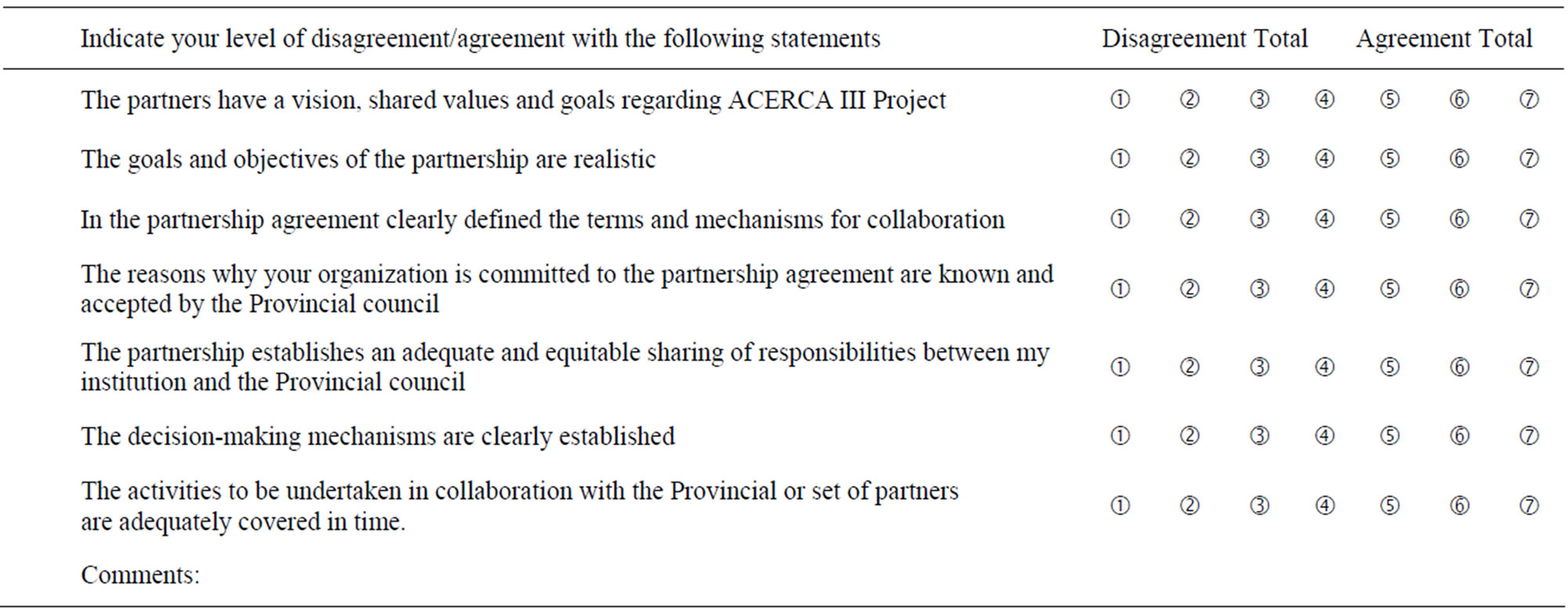

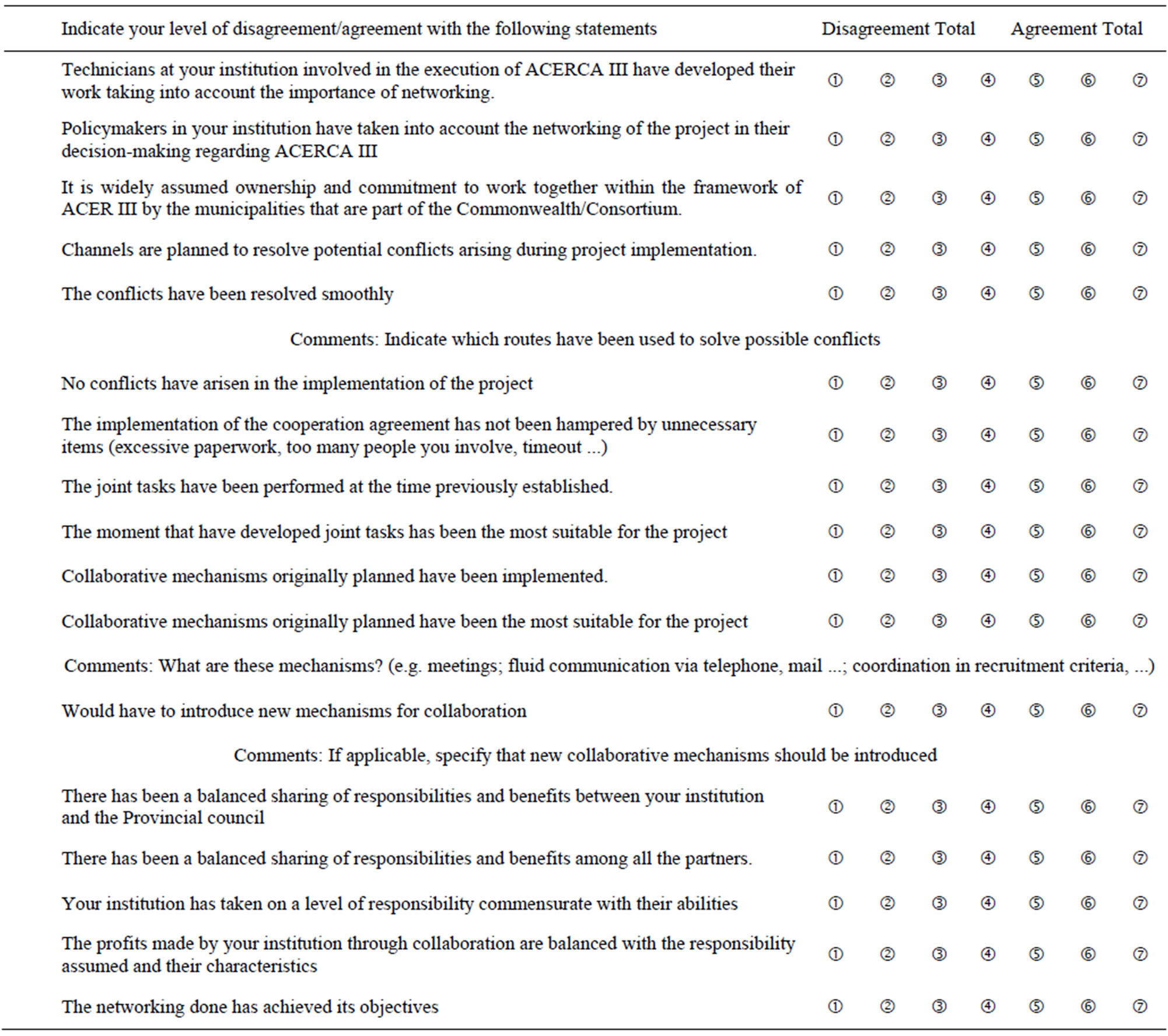

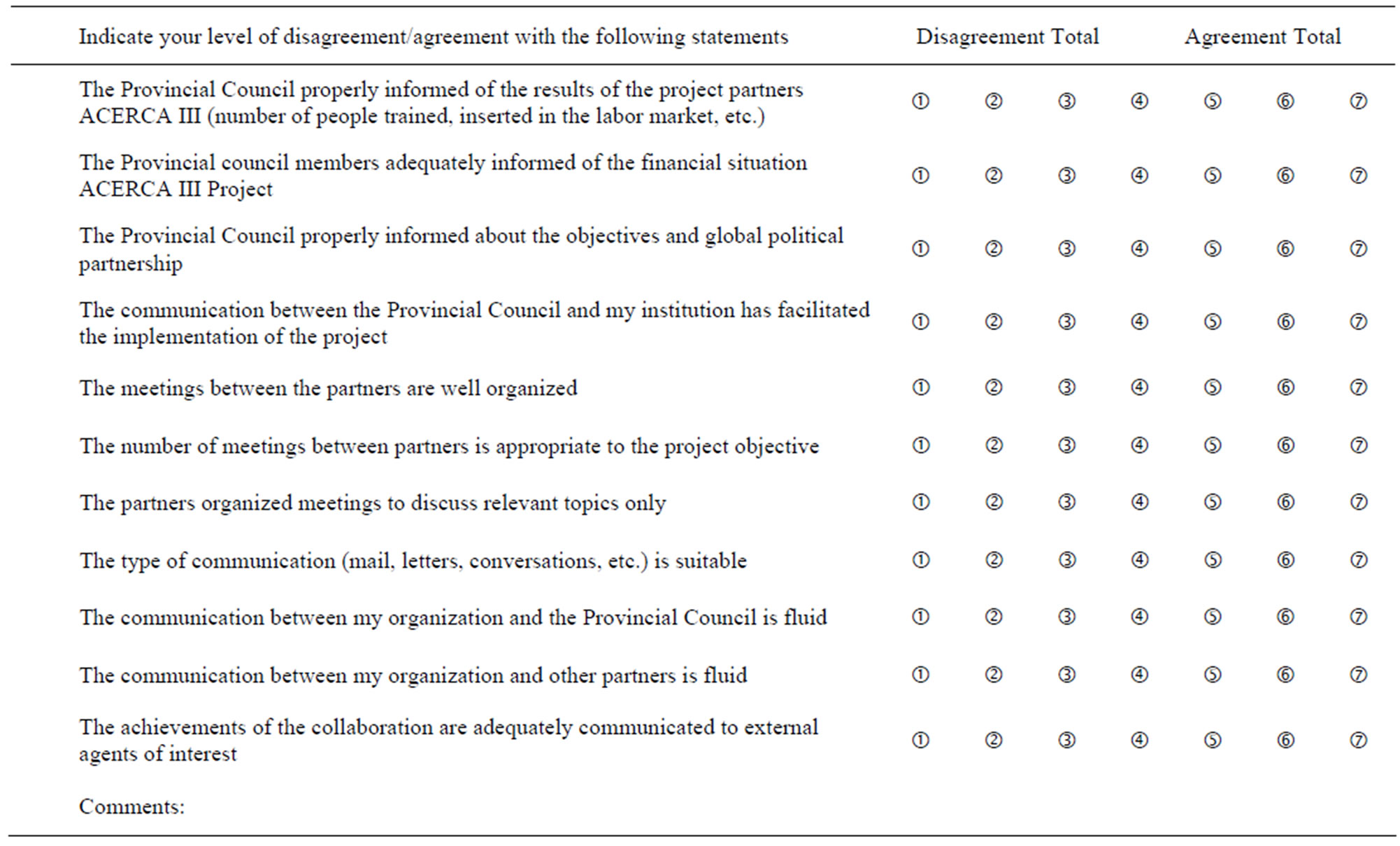

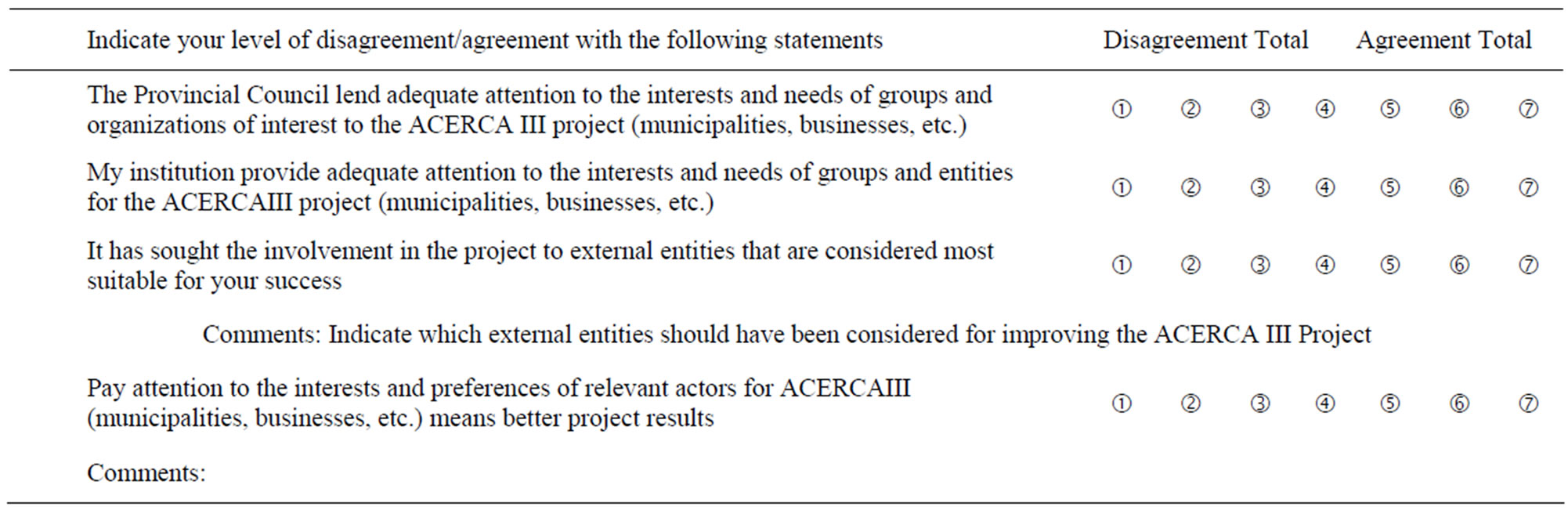

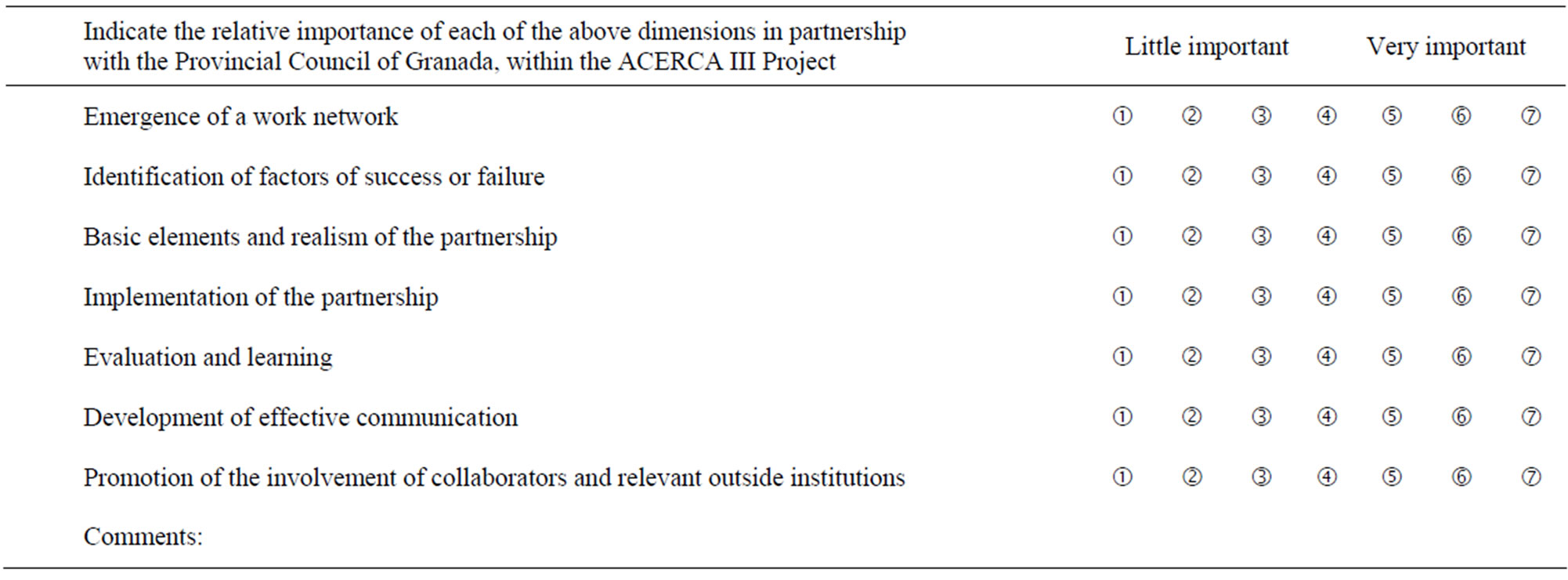

This evaluation tool is based on seven dimensions or principles of working in partnership. Each dimension has been broken down into elements, which will enable us to gain a deeper understanding of each of them and identify more exactly the aspects of the partnership that contribute most to its effectiveness, as well as its strengths and weaknesses.

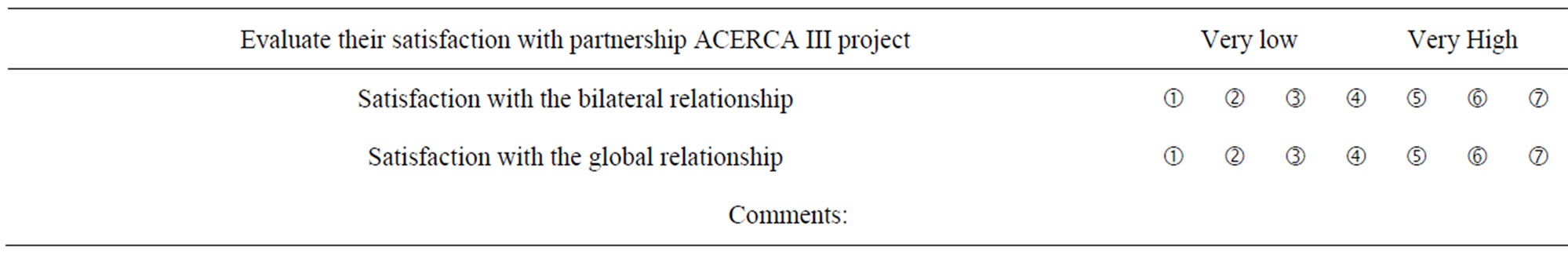

To evaluate the elements of the seven partnership dimensions, is established seven possible responses for each statement, ranging from totally disagree to totally agree. Maximum scores indicate that the partnership is successful, while minimum scores indicate the reverse. The questionnaire also includes space for respondents to make comments, allowing them to go into more detail or clarify some quantitative responses. The questionnaire also includes a section evaluating the relative importance for each partner of the different partnership dimensions. There is also a section to evaluate each partner’s level of global satisfaction with their bilateral relationship with the Provincial Council and with their relationships with the group of partners of the project, weighted by the level of intensity of the relationship concerned.

Finally, in order to consider possible improvements, the questionnaire includes the item new partnership mechanisms should be introduced.

With regard to the reliability of the scales used, the Cronbach alpha coefficient [30] exceeds 0.7 for each of the scales. They are consequently all acceptable for use in the research [31,32].

The questionnaire for the Provincial Council is practically the same as the one for the other partners apart from the logical modifications (e.g., relationship with the Provincial Council changes to relationship with this partner).

With regard to the analytical techniques used, the small number of cases analysed—13 in total—means that most multivariate statistical techniques cannot be applied reliably. Nevertheless, is took some steps to increase the number of valid cases for the analysis. For example, means of the variable stand in for some missing values. The analytical techniques used include analysis of the reliability of the measurement scales using the Cronbach Alpha coefficient. Is also used the Pearson correlation coefficient, descriptive statistics and the difference of means test (t-test).

Is used the statistics package SPSS 13.0 to process and analyse all the information obtained.

4. Results

The mean global evaluation of the partnerships for all the partners in the ACERCA III project, after weighting the dimensions by the relative importance of each dimension according to each partner, is 39.3 (on a scale of 0 to 49). Guadix District Association of Municipalities and Sierra Nevada Development Consortium give the lowest scores, while the Provincial Council gives the highest evaluations, specifically for its partnerships with Sierra Nevada-Vega Sur Consortium and Poniente Granadino Rural Development Consortium (Table 1).

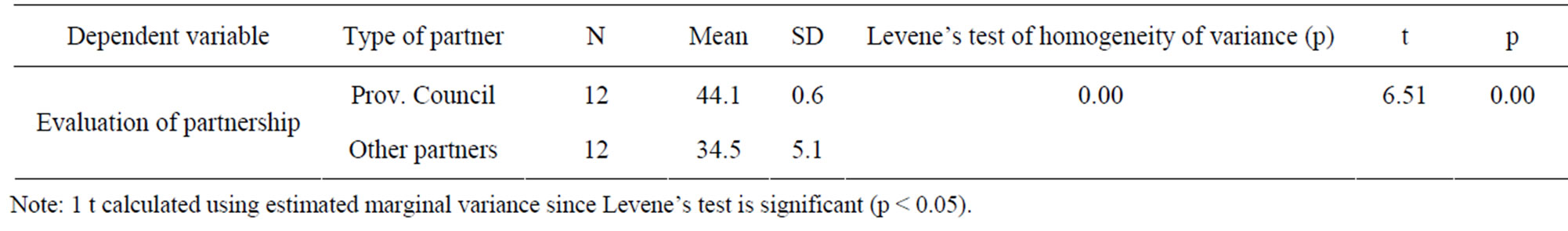

The Provincial Council and the other partners diverge in their evaluations of the partnerships they are involved in. Consequently runs a difference of means test on the evaluations in function of whether the Provincial Council or the other partners are making the evaluation. The results show highly significant statistical differences between the two groups (see Table 2). The Provincial Council gives higher scores to its partnerships than the other partners do.

Given the low standard deviation in the Provincial Council’s partnership evaluations, and in order not to bias the results in the direction of this partner’s response, is included the means of its responses to each item as another case to analyse along with the other partners.

The mean values of the partnership dimensions (see Table 3), once weighted by the relative importance of each dimension according to each partner, show that the two dimensions that are most highly valued in terms of the partnerships in this project are: Promotion of the involvement of collaborators and relevant outside institutions, and Basic elements and realism of the partnership. In contrast, the two partnership dimensions that are least valued are: Emergence of a work network, and Evaluation and learning.

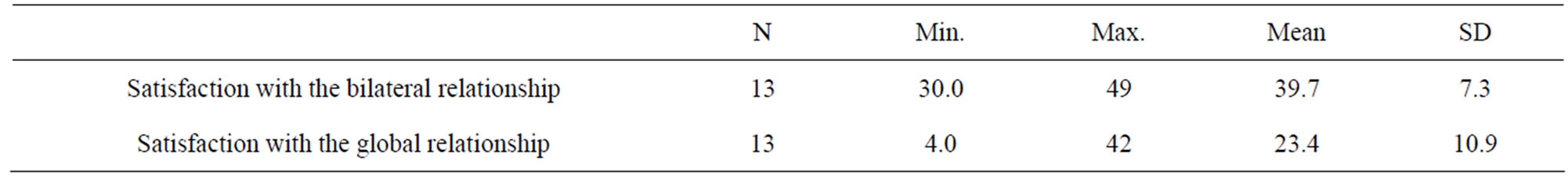

The measures of satisfaction with the partnership within the ACERCA III project, after weighting by the intensity of the relationships maintained (Table 4) show that the satisfaction with the bilateral relationships Provincial Council-each partner has a higher average score than the satisfaction with the global relationships of all the partners with all the rest, or the network as a whole.

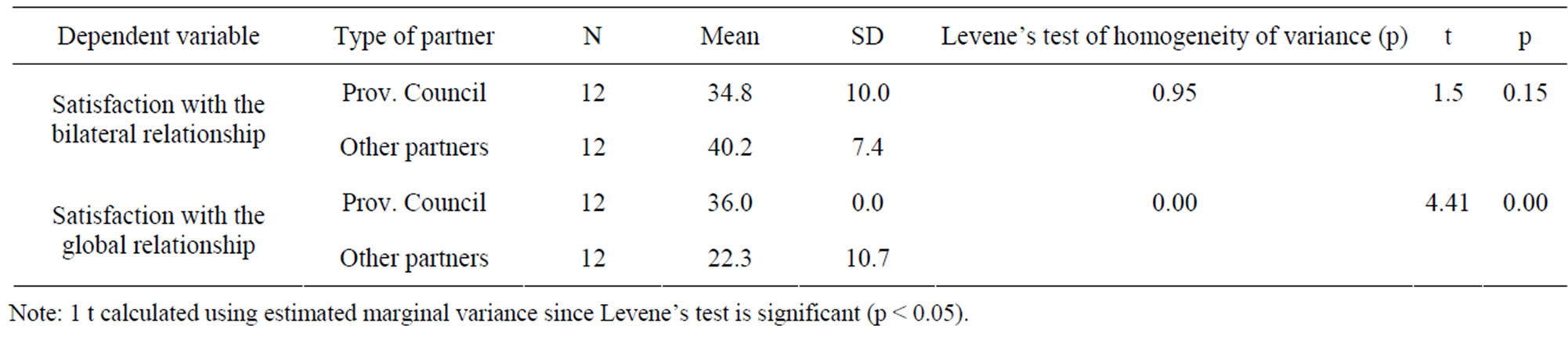

Looking more closely at the analysis of satisfaction with the partnership, differences are apparent in both types of satisfaction considered in this study in function of which partner is making the evaluation (the Provincial Council, as the main partner, or the other, minor partners). But the difference of means test for both types of satisfaction shows significant differences only for satis-

Table 1. Global evaluation of partnership with provincial council (other partners) or with each partner (provincial council).

Table 2. Relation between evaluation of partnership and type of partner.

faction with the global relationship, with the Provincial Council’s evaluation almost a third higher than the other partners’ (36.0 compared to 22.3). Also of relevance is the fact that the other partners are more satisfied with the bilateral relationship than with the global relationship, while the Provincial Council is more satisfied with the global relationship (Table 5).

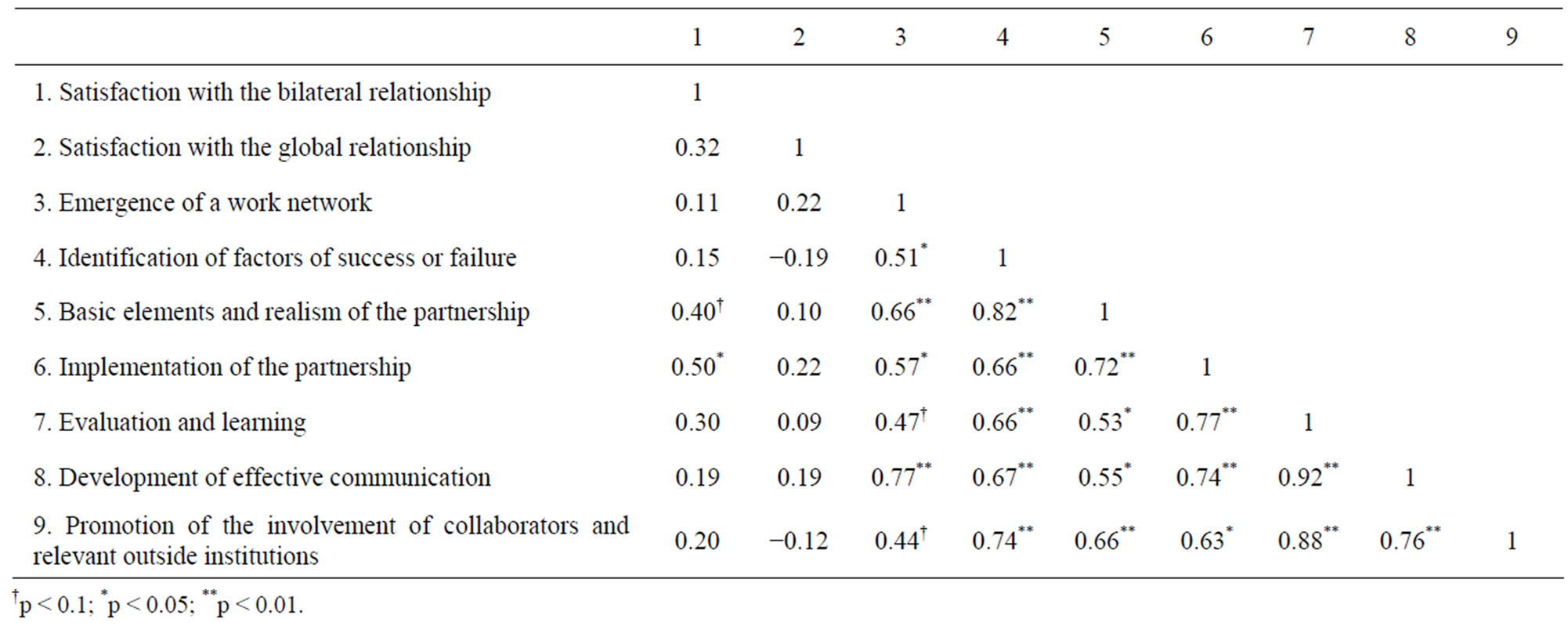

Has been used the Pearson correlation coefficient to study the relation between satisfaction with the partnership within the ACERCA III project and the dimensions of that partnership (Table 6). Of all the dimensions considered, only Implementation of the partnership and Basic elements and realism of the partnership have a positive association with satisfaction with the bilateral rela-

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of partnership dimensions.

Table 4. Satisfaction with partnership.

Table 5. Satisfaction with partnership and type of partner.

Table 6. Pearson correlation matrix.

tionship. On the other hand, satisfaction with the global relationship is not related to any of the partnership dimensions.

With regard to the question of whether new partnership mechanisms should be introduced, the mean score for this item is 4 (on a scale of 0 to 7). This score is over the midway point, but shows that there is still room for including new partnership mechanisms. Looking more closely at the analysis of this item in function of the type of partner responding reveals highly significant statistical differences. Thus, the Provincial Council provides a maximum response to this question, while the other partners barely score this item over the midway point of the range (Table 7).

5. Conclusion, Limitations, Future Research Lines and Recommendations for Improvement

Among the main conclusions of the current evaluation of the partnerships within the ACERCA III project, although the global evaluation is relatively high, the rest of the partners give a significantly lower score than the Provincial Council does. This finding could be explained by the Provincial Council’s stronger involvement in the project, since this partner takes on most of its responsibilities.

The two dimensions that are most highly valued in the partnership are Promotion of the involvement of collaborators and relevant outside institutions, and Basic elements and realism of the partnership. In contrast, the two partnership dimensions that are the least highly valued are Emergence of a work network, and Evaluation and learning.

Promotion of the involvement of collaborators and relevant outside institutions is to some extent inherent to the project, since for example the students have to do work placements in firms, so it is logical that the partners strive to seek and promote relationships with these and other outside agents. Basic elements and realism of the partnership is a fundamental dimension for the project to run well in the future, so it is also unsurprising that the partners stress this dimension, since if they do not previously establish the responsibilities, tasks, partnership mechanisms, and so on, the implementation of the partnership is unlikely to be successful. Moreover, this dimension is positively associated with satisfaction with the bilateral relationship, in other words, efforts expended in aspects to do with this dimension lead to a high evaluation of them and this may have had a positive influence on the satisfaction with the bilateral relationship between the Provincial Council and each partner.

With regard to the dimensions that achieved the worst scores, Emergence of a work network is the least highly valued, because the partners have not really worked as a work network, with all the partners interrelating with each other, and so no synergies have emerged. As to evaluation and learning, is should mention that this is the first time that the partnerships within an ACERCA Project has been evaluated, so it is hardly surprising that the partners have given a low evaluation to this dimension.

Satisfaction with the partnership is higher for the bilateral relationship between partners than for the joint relationship of all the partners, which can be explained by the fact that the minor partners have very little relationship with any other partner apart from the Provincial Council itself. The divergence between the Provincial Council and the other partners in their satisfaction with the global relationship can be explained by the previous point, since the other partners cannot be very satisfied with a relationship that hardly exists, while the Provincial Council’s perspective is totally different, since it has relationships with each of the other partners.

Basic elements and realism of the partnership and Implementation of the partnership are the partnership dimensions that are related to satisfaction with the bilateral relationship, although the latter dimension has the closest positive relation. This finding shows the importance to the partners of the operational aspects of the partnership, as well as the emphasis they put in it. First, they design the partnership mechanisms and then implement them, and this effort is reflected in a greater satisfaction with the bilateral relationship between the Provincial Council and each of the other partners.

Finally, there is no consensus between the partners about whether new partnership mechanisms should be incorporated. The Provincial Council is very favourable to the idea of implementing new partnership tools, but the other partners do not perceive that this is so necessary. This finding could perhaps be explained by the other partners’ relatively low satisfaction with the global relationship. The Provincial Council, as the main partner, conceivably perceives the need to incorporate new partnership mechanisms relating to the joint relationships of all the partners with all the others.

On the basis of these considerations, it concludes this work with a number of recommendations to improve the partnerships in possible future ACERCA projects. These measures should address most of the weaknesses of the current situation and reinforce many of the strengths.

1) Create a true work network, where all the partners interrelate with all the others. All partners would then be able to exploit the synergies generated in the joint rela-

Table 7. Relation between advisability of introducing new partnership mechanisms and type of partner.

tionships of all the partners with all the others. The partners would then be better able to exploit the synergies generated in the joint relationships of all the partners with all the others, and partners could support each other mutually, helping each other to do their individual tasks. This would improve the other partners’ global evaluation of the global relationships and their satisfaction with them, since the partners would then be more involved in all the processes of the partnership.

2) Intensify relationships with outside agents. This action could mean increasing the number of partnership agreements with firms in order to increase the diversity of work placements, and ensure that these fit each student’s profile more closely. The partners could also intensify their interactions with all types of associations and groups in order to incorporate new criteria for student selection in function of the information provided by these groups. Moreover, in the medium and long term this would improve monitoring of the employment, social and economic repercussions of the successive ACERCA projects.

3) Improve the evaluation and learning process of the partnership. More specifically, this might involve the following measures, among others:

• Clarifying among all the partners, and before implementing the project, what criteria will be used to measure success in the achievement of the objectives of both the project and the partnership, so that the partners can stress these aspects. Equally, clarifying the mechanisms of revision of both types of objective and their implementation in function of the results of both evaluations.

• Designing new tools to evaluate the joint relationships, bearing in mind that this would improve awareness of how the partnership works and would not be an obstacle to the partnership, since the global evaluation of whether responding to the evaluation questionnaires is excessive is under 1.5 (on a scale of 1 to 7), meaning there is room to implement new measuring tools.

• Disseminating the results of the evaluation among the partners and agents relevant to the project, including the publication and distribution of the evaluation report.

REFERENCES

- European Commission, “The MEANS Collection: Evaluating Socio-Economic Programmes, 5,” Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 1999

- K. W. Eilbert and V. Lafronza, “Working Together for Community Health—A Model and Case Studies,” Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2005, pp. 185-199.

- J. M. Brinkerhoff, “Government-Nonprofit Partnership: A Defining Framework,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2002, pp. 19-30. doi:10.1002/pad.203

- R. Bush, “Survival of the Nonprofit Spirit in a For-Profit World,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4, 1992, pp. 331-410. doi:10.1177/089976409202100406

- C. Malena, “Relations between Northem and Southem Non-Governmental Development Organizations,” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 16, No. 9, 1995, pp. 7-29. doi:10.1080/02255189.1995.9669577

- G. A. Tilley-Lubbs, “Teaching and Learning for Social Justice: Reciprocal Relationships in the University and Spanish-Speaking Communities,” Career Education Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2011, pp. 18-24.

- H. Van der Heigden, “The Reconciliation of NGO Autonomy, Program Integrity and Operational Effectiveness with Accountability to Donors,” World Development, Vol. 21, No. 4, 1987, pp. 103-112. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(87)90148-3

- Shell International, “Profit and Principles: Does There Have To Be a Choice? The Shell Report-1998,” Shell International, London, 1998

- World Bank, “The World Bank’s Partnership with Nongovernmental Organizations,” World Bank, Washington DC, 1996.

- D. L. Brown and D. Ashman, “Participation, Social Capital, and Intersectoral Problem-Solving: African and Asian Cases,” Word Development, Vol. 24, No. 9, 1996, pp. 1467-1479. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(96)00053-8

- J. M. Coston, “Administrative Avenues to Democratic Governance: The Balance of Supply and Demand,” Public Administration and Development, Vol. 18, No. 5, 1998, pp. 479-493. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-162X(199812)18:5<479::AID-PAD37>3.0.CO;2-Y

- V. Lowndes and C. Skelcher, “The Dynamics of MultiOrganizational Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance,” Public Administration, Vol. 76, No. 2, 1998, pp. 313-333. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00103

- H. Wu, Y. Lin, F. Chien and Y. Hung, “A Study on the Relationship among Supplier Capability, Partnership and Competitive Advantage in Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry,” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2011, pp. 122-138. http://search.proquest.com/docview/877024940?accountid=14542

- J. Arsenault, “Forging Nonprofit Alliances,” Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1998

- C. R. Bell and H. Shea, “Dance Lessons: Six Steps to Great Partnerships and Business and Life,” Barrett Koehler, San Francisco, 1998.

- S. J. Fielden, M. L. Rusch, M. T. Masinda, J. Sands, J. Frankish and B. Evoy, “Key Considerations for Logic Model Development in Research Partnerships: A Canadian Case Study,” Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2007, pp. 115-124. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.01.002

- J. H. Dobbs, “Competition’s New Battleground: The Integrated Value Chain,” Cambridge Technology Partners, Cambridge, 1999.

- D. M. Lambert, M. A. Emmelhainz and J. T. Grardner, “Developing and Implementing Supply Chain Partnership,” International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 7, No. 2, 1996, pp. 1-17. doi:10.1108/09574099610805485

- B. Benito, F. Bastida and Guillamón, “Public-Private Partnerships in the Context of the European System of Accounts (ESA95),” Open Journal of Accounting, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-10. doi:10.4236/ojacct.2012.11001

- K. M. Kanter, “Collaborative Advantage: The Art of Alliances,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72, No. 4, 1994, pp. 96-108.

- S. Kumar and A. Seth, “The Design of Coordination and Control Mechanisms for Managing Joint Venture-Parent Relationships,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, 1998, pp. 579-599. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199806)19:6<579::AID-SMJ959>3.0.CO;2-8

- Audit Commission, “A Fruitful Partnership. Effective Partnership Working,” Audit Commission Publications, London, 1998.

- Liverpool Partnership Group, “LSP Accreditation— LPG’s self Assessment,” Liverpool Partnership Group, Liverpool, 2002.

- Rocket Science, “Communities Scotland and the Community Planning Task Force. Assessment of Partnership Toolkits,” Rocket Science UK Ltd., Final Report: Volume 2, 2003.

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, “Assessing Strategic Partnership. The Partnership Assessment Tool,” Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, London, 2003.

- A. M. Al-Rasheed and F. M. Al-Qwasmeh, “The Role of the Strategic Partner in the Management Development Process,” International Journal of Commerce and Management, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2003, pp. 144-175. doi:10.1108/eb047470

- D. L. Ransley, “Assessing the Randd-Business Relationship,” Research Technology Management, Vol. 40, No. 4, 1997, pp. 12-18.

- M. Stame, “Theory-Based Evaluation and Types of Complexity,” Evaluation, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2004, pp. 58-76. doi:10.1177/1356389004043135

- E. Stern, “What Shapes European Evaluation? A Personnel Reflection,” Evaluation, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2004, pp. 7-15. doi:10.1177/1356389004044411

- L. J. Cronbach, “Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests,” Psychometrika, Vol. 16, 1951, pp. 297- 394. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

- A. A. Buchko, “Conceptualization and Measurement of Environmental Uncertainty: As Assessment of the Miles and Snow Perceived Environmental Uncertainty Scale,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 37, No. 2, 1994, pp. 410-425. doi:10.2307/256836

- J. C. Nunnally, “Psychometric Theory,” 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978.

Annex

Questionnaire about the Provincial Council’s Partners