Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.4 No.1(2014), Article ID:42793,7 pages DOI:10.4236/tel.2014.41003

Can a Carbon Tax Be Effective without a Grand Coalition?

School of Economics, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia

Email: amnon_levy@uow.edu.au

Copyright © 2014 Amnon Levy. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Amnon Levy. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received December 10, 2013; revised January 10, 2014; accepted January 17, 2014

KEYWORDS

Carbon Tax; Abstinence; Understating Expectations; Guilt; Emissions

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes an interaction between a carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition of rich countries, abstaining rich countries and poor countries. The non-coalition countries may suffer from loss of reputation and guilt and may overstate the emission-moderating effect of the carbon tax. As long as these three types of countries react to their counterparts’ emissions, taxing carbon-dioxide emissions unilaterally does not necessarily reduce the global emissions. Nor does it necessarily moderate the emissions of the coalition.

1. Introduction

The atmosphere is an indivisible open-access natural resource. In the absence of property rights, formation of markets for the externalities created by emissions of greenhouse gasses is impossible (cf. Coase [1]). Hence, there is a need for international cooperation. But can a grand coalition of nations for reducing emissions be realised? The international meetings held on this issue suggest that the answer is negative. Internal issues and freeriding of sovereign countries provide explanations to the empty core of the cooperative game of international emission reduction. Moreover, the absence of a mechanism for enforcing sufficiently strong penalties on sovereign countries (large ones, in particular) abstaining from the grand coalition, or the inexistence of an environmentally oriented dictating country, implies that any strong epsilon-core is empty (cf. Shapley and Shubik [2]).

The policy measures for controlling greenhouse-gas emissions and their external effects are classified in the environmental economic literature as quantity-based instruments and price-based instruments. Theoretical comparisons of these instruments have followed Weitzman’s [3] generic analysis of stock-based externalities, which linked their relative efficiency to the relative slopes of the marginal benefits and costs of control. In the context of greenhouse gasses and climate change, Pizer [4], Hoel and Karp [5], Newell and Pizer [6], and Fischer and Newell [7] have provided arguments in favour of pricebased instruments.

Proponents of emission tax expect the tax to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by increasing efficiency in fossil-fuel consumption and encouraging and financing the development and adoption of cleaner sources of energies and technologies. While the responsibility for, and consequences of, greenhouse gas emissions are shared by all countries, only a few are willing to tax emissions. In the absence of international agreement on operative scheme, carbon tax has been unilaterally implemented in Scandinavian and West European countries, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

This paper argues that the reactions of the unwilling countries to the expected emissions of the willing countries are crucial for assessing the effectiveness of the said price-based policy instrument. The analysis leading to this conclusion is based on an environmentally favourable polar framework. Hence, ineffectiveness of a pricebased policy instrument in that framework implies ineffectiveness in a less favourable framework. The considered favourable framework allows a carbon-tax charging coalition of environmentally and reputation concerned rich countries to exist. The coalition taxes members’ emissions and generates a positive common-pool externality for members by concertedly investing the carbontax revenues in improving fossil-fuel consumption’s efficiency and developing and adopting low-emission energy sources and technologies. The abstaining, less environmentally and reputation concerned, rich countries incur international reputation and political loss for per capita emissions beyond the coalition’s level. Poor countries do not incur such loss due to their low per capita emissions and consumption. The positive common-pool externality and the international reputation and political loss strengthen the inclination of the environmentally and reputation more concerned rich countries to stay in the coalition.

The computation of the equilibrium carbon-dioxide emissions also takes into account another environmentally favourable aspect: a possible guilt effect on the abstaining countries’ level of concern for the environment. However, the computation takes into account that some of the expectations of the three types of countries about each other’s emissions can be understated due to a possible excessive impression created by the coalition’s environmental initiatives.

The computed equilibrium reveals that as long as the three types of countries react to their counterparts’ emissions, taxing carbon-dioxide emissions and investing the tax revenues in development and adoption of cleaner energy sources and technologies do not necessarily reduce global emissions, nor do they moderate the coalition’s emissions. This conclusion also holds under accurate expectations and absence of guilt in the abstaining countries. The analysis of the equilibrium identifies the conditions under which the unilateral implementation of the carbon-tax by the coalition decreases the coalition’s emissions and global emissions.

The scepticism implied by the analysis about the effectiveness of one-sidedly implemented carbon tax in a sub group of willing rich countries should not be interpreted as supporting a wait-and-see strategy. The risk of global warming and, consequently, climate change is real. Global warming is mainly a reflection of a chronic and intensifying imbalance in the atmospheric carbon-dioxide cycle. Contrasted with deep historical measurements obtained from Antarctic ice-cores, the Keeling Curve reveals unprecedented levels and rates of accumulation of carbon-dioxide in the atmosphere during the last five decades. This trend is expected to be supported by continued population growth, industrialization of developing countries and deforestation of tropical lands. Since the atmosphere is indivisible and climate change is a global stock-based externality, international cooperation and planning is desirable. The implied scepticism about the effectiveness of one-sidedly implemented carbon tax in a sub group of willing rich countries emphasizes the need for global cooperation.

The analytical part of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 classifies the stakeholders as members of a coalition of carbon-tax paying rich countries, or abstaining rich countries, or abstaining poor countries, and describes their utilities. Section 3 derives the reaction of each stakeholder to the counterparts’ emissions. Section 4 computes the stakeholders’ equilibrium per capita emissions. The computation of the equilibrium emission levels takes into account the possibility that the abstaining countries suffer from guilt and/or overstate the emission-moderating effect of the carbon tax on the coalition countries’ emissions. With the computed equilibrium in mind, Section 5 derives propositions that reflect scepticism about the effectiveness of one-sidedly implemented carbon tax by a group of willing rich countries.

2. Stakeholders and Their Utilities

Suppose that the world has  rich countries divided into two distinct groups by their degree of concern about the state of the world’s environment. Those with the higher degree of concern (denoted by subscript rc),

rich countries divided into two distinct groups by their degree of concern about the state of the world’s environment. Those with the higher degree of concern (denoted by subscript rc),  in number, form a carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. The other

in number, form a carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. The other  rich countries with the lower degree of concern (denoted by subscript ra), abstain. For tractability, the population of each of the coalition countries is

rich countries with the lower degree of concern (denoted by subscript ra), abstain. For tractability, the population of each of the coalition countries is  and the population of each of the abstaining rich countries is

and the population of each of the abstaining rich countries is . The poor countries (denoted by subscript p) are

. The poor countries (denoted by subscript p) are  in number. For simplicity, they have the same size of population,

in number. For simplicity, they have the same size of population,  , and the same degree of concern about the state of the world’s environment.

, and the same degree of concern about the state of the world’s environment.

The three types of countries produce the same composite good, but with different technologies and levels of carbon-dioxide emissions per unit. With  indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the poor countries and

indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the poor countries and  the ratio of his output to emissions, the per capita output and also (with income-tax revenues being redistributed) disposable income in the poor countries is:

the ratio of his output to emissions, the per capita output and also (with income-tax revenues being redistributed) disposable income in the poor countries is:

. (1)

. (1)

Before the formation of the carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition, all the  rich countries have shared a technology that was more fuel-efficient, hence cleaner (per given output), than that of the poor countries. This technology prevails in the abstaining rich countries. With

rich countries have shared a technology that was more fuel-efficient, hence cleaner (per given output), than that of the poor countries. This technology prevails in the abstaining rich countries. With  indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the abstaining rich countries and

indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the abstaining rich countries and  the difference in the output-emission ratio between the abstaining rich countries and the poor countries, the per capita output and also disposable income in the abstaining rich countries is:

the difference in the output-emission ratio between the abstaining rich countries and the poor countries, the per capita output and also disposable income in the abstaining rich countries is:

. (2)

. (2)

With  indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the coalition’s rich countries,

indicating the emissions released by the production process of the representative resident of the coalition’s rich countries,  the carbon-tax rate on domestic emissions set by the coalition, and

the carbon-tax rate on domestic emissions set by the coalition, and  the marginal return on the aggregate carbon-tax revenues

the marginal return on the aggregate carbon-tax revenues invested concertedly by the coalition in development and adoption of cleaner energy sources and technologies, the per capita disposable income in the coalition countries is:

invested concertedly by the coalition in development and adoption of cleaner energy sources and technologies, the per capita disposable income in the coalition countries is:

. (3)

. (3)

The term  displays a positive common-pool externality. In addition to a greater concern about the environment and a potential international reputation and political loss, access to the cleaner energy sources and technologies developed by the concerted investment of the aggregate emission-tax revenues provides an incentive for each of the

displays a positive common-pool externality. In addition to a greater concern about the environment and a potential international reputation and political loss, access to the cleaner energy sources and technologies developed by the concerted investment of the aggregate emission-tax revenues provides an incentive for each of the  coalition countries to cooperate.

coalition countries to cooperate.

Each type of country,  , gains utility from its per capita disposable income,

, gains utility from its per capita disposable income,  , at a rate

, at a rate , which represents a constant, for tractability, marginal utility from disposable income. Each type of country also gains utility from environmental improvement (

, which represents a constant, for tractability, marginal utility from disposable income. Each type of country also gains utility from environmental improvement ( ) and loses utility from environmental deterioration

) and loses utility from environmental deterioration  at a rate

at a rate  that reflects its degree of concern about changes in the environment. Recalling the aforementioned concern-differential between the two types of rich countries,

that reflects its degree of concern about changes in the environment. Recalling the aforementioned concern-differential between the two types of rich countries,  1.

1.

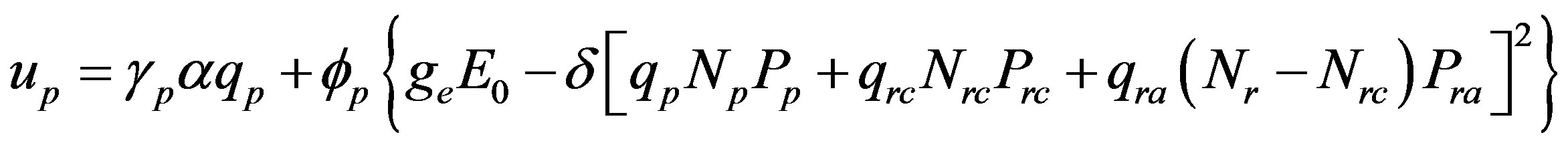

The per capita utility in an abstaining rich country is further diminished by international reputation and political loss from exceeding the coalition’s per capita emission. This loss is intensified by the exceptionality of the rich country’s abstinence and by the power of the coalition.

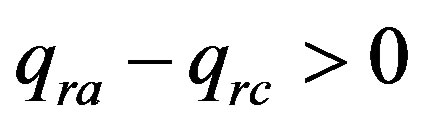

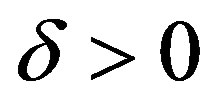

With the scalar  (positive when

(positive when  and zero otherwise) denoting the international reputation and political loss coefficient2:

and zero otherwise) denoting the international reputation and political loss coefficient2:

. (4)

. (4)

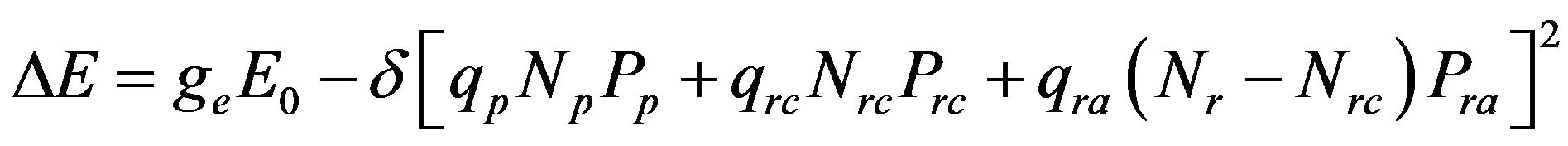

With  denoting the initial state of the global environment,

denoting the initial state of the global environment,  the global environment’s natural regeneration rate, and

the global environment’s natural regeneration rate, and  the coefficient of a convex form (quadratic, for simplicity) representing the damage inflicted by deviations from zero emissions (via global warming and climate change) on the global environment, the change in the global environment is assumed to be given by:

the coefficient of a convex form (quadratic, for simplicity) representing the damage inflicted by deviations from zero emissions (via global warming and climate change) on the global environment, the change in the global environment is assumed to be given by:

. (5)

. (5)

For tractability, the decay of the initial atmospheric carbon-dioxide stock is ignored. While complicating the construction of a convex damage function that receives a negative value when the net change in the atmospheric stock is negative, the inclusion of decay does not change the nature of the conclusions. In addition, the life expectancy of carbon-dioxide molecules in the atmosphere is very long (up to several hundreds of years); namely, the rate of decay of the stock is very low.

In view of (1)-(5), the utilities of the representative agents of the three types of countries are:

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

. (8)

. (8)

3. Reactions to Counterparts’ Emissions

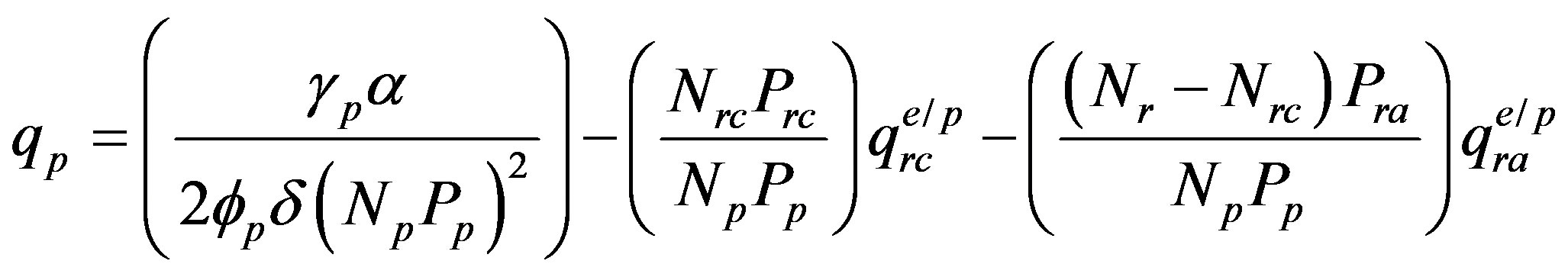

In each of the three types of countries, per capita carbon-dioxide emission is set at a level that maximizes the representative agent’s utility, given the expectations about the foreign counterparts’ emissions. From the necessary condition, the reaction function of the utility-maximizing representative agent living in a poor country to the expected emissions (denoted by the superscript e/p) of the agents living in the coalition’s rich countries and the abstaining rich countries is:

. (9)

. (9)

The first term on the right-hand side indicates the poor countries’ optimal per capita emission in the absence of emissions from other sources. The representative agent of a poor country reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in his richer counterparts’ emissions is expected, proportionally to their relative population size.

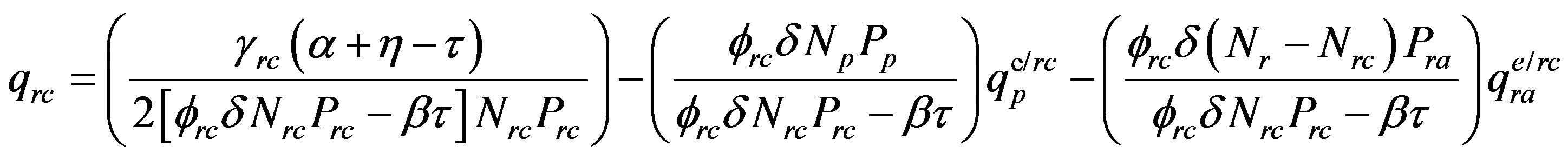

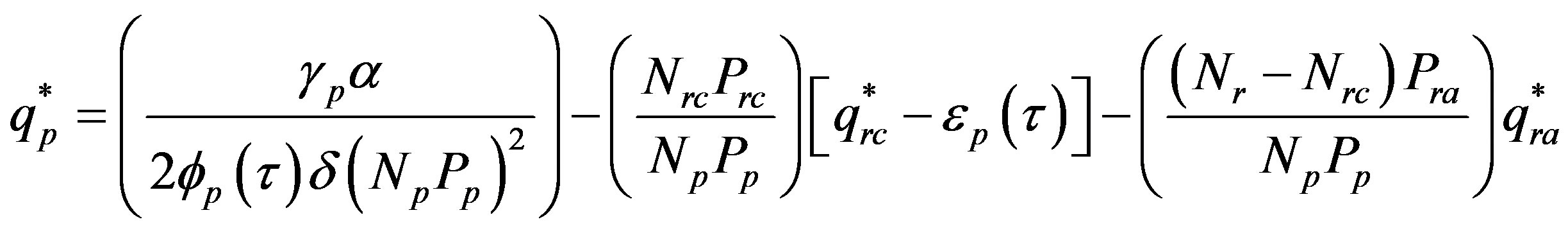

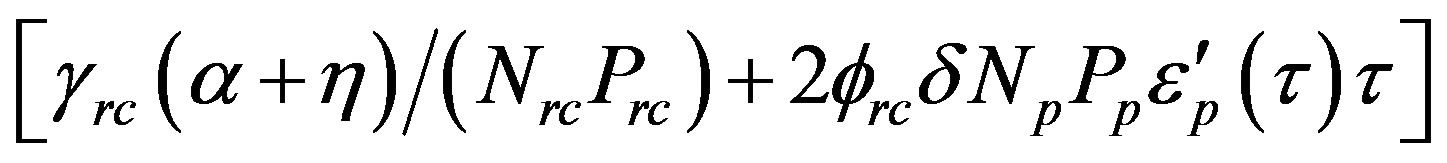

The reaction function of the utility-maximizing representative agent living in a coalition country to the expected emissions (denoted by the superscript e/rc) of the agents living in the non-coalition rich countries and the poor countries is:

. (10)

. (10)

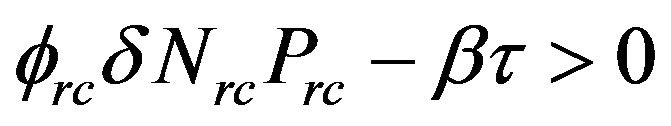

The first term on the right-hand side indicates the coalition’s optimal per capita emission in the absence of emissions from the abstaining countries. Noting that the second-order condition for maximum requires , the representative agent of a coalition country reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in his poor and abstaining-rich counterparts’ emissions is expected. His reaction is intensified by his counterparts’ relative population size and by the return on the investment of the emission-tax in developing and adopting cleaner energy sources and technologies.

, the representative agent of a coalition country reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in his poor and abstaining-rich counterparts’ emissions is expected. His reaction is intensified by his counterparts’ relative population size and by the return on the investment of the emission-tax in developing and adopting cleaner energy sources and technologies.

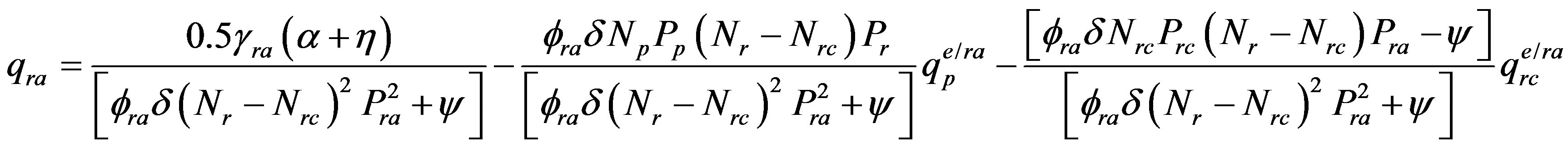

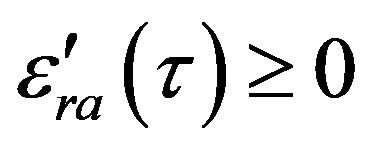

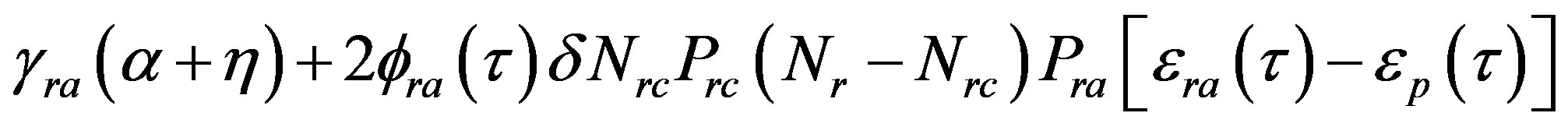

The reaction function of an agent living in an abstaining rich country to the expected emissions (denoted by the superscript e/ra) of the agents living in the coalition’s rich countries and poor countries is:

. (11)

. (11)

The first term on the right-hand side indicates the abstaining rich countries’ optimal per capita emission in the absence of emissions from other sources. The representative agent of an abstaining rich country reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in his poorer counterparts’ emissions is expected. His reaction is intensified by the poorer population’s relative size. If , he also reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in the coalition’s per capita emissions is expected. His reactions are moderated by his marginal international reputation and political loss,

, he also reduces (increases) his emissions when a rise (decline) in the coalition’s per capita emissions is expected. His reactions are moderated by his marginal international reputation and political loss,  , engendered by a deviation from the coalition’s per capita emission.

, engendered by a deviation from the coalition’s per capita emission.

4. Inaccurate Expectations, Guilt and Equilibrium Emissions

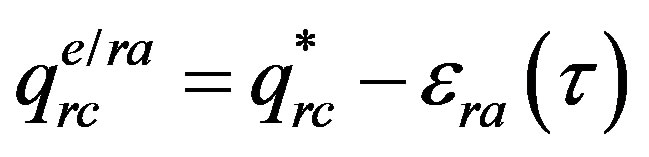

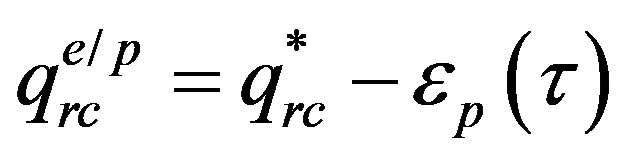

In computing the equilibrium emissions (denoted by asterisks), let us allow some of the expectations of the three types of countries about each-other’s emissions to be inaccurate. It is possible that, being impressed by the coalition’s environmental initiatives, the abstaining countries overstate the emission-moderating effect of the emission tax and hence understate the per capita emissions of the coalition. By the same rationale it is further possible that the higher the tax rate, the stronger the abstaining countries’ impression and, consequently, understatement of the coalition’s actual emission. We let  and

and  indicate the expectation errors of the abstaining rich countries and the poor countries, respectively, with

indicate the expectation errors of the abstaining rich countries and the poor countries, respectively, with  and

and  and

and  and

and , and consider the case where only the expectations about the rich coalition countries’ emissions can be inaccurate:

, and consider the case where only the expectations about the rich coalition countries’ emissions can be inaccurate: ,

,  ,

,  and

and ,

,  and

and .

.

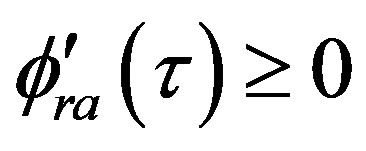

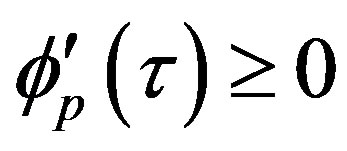

While it can be expected that the abstaining countries’ understatement of the coalition’s emissions contributes to global emissions, it is possible that the coalition’s environmental initiatives intensify the abstaining countries’ sense of guilt and moderate their free-riding. It is further possible that the higher the coalition’s emission tax, the stronger the guilt sensed by the abstaining countries. Their intensified sense of guilt can be manifested in increased concerns about the environment:  and

and , where a zero-gradient indicates a guilt-free disposition.

, where a zero-gradient indicates a guilt-free disposition.

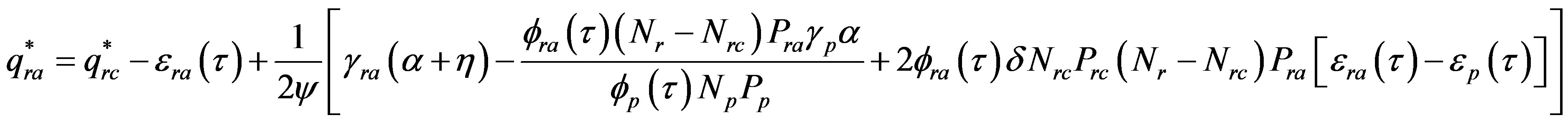

The incorporation of the said expectations and a possible concern-intensifying guilt into the reaction Equations (9)-(11) leads to:

(12)

(12)

(13)

(13)

. (14)

. (14)

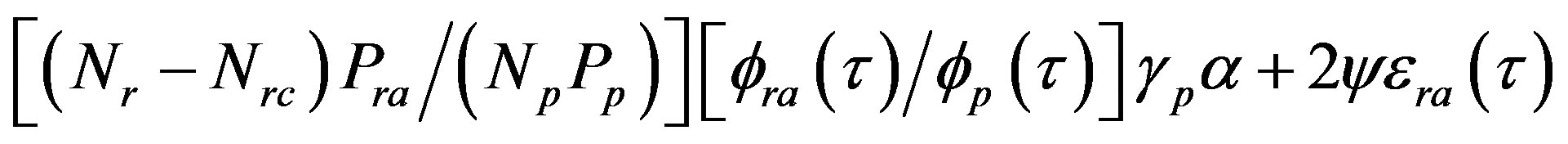

In turn, the equilibrium per capita emissions are3:

(15)

(15)

(16)

(16)

(17)

(17)

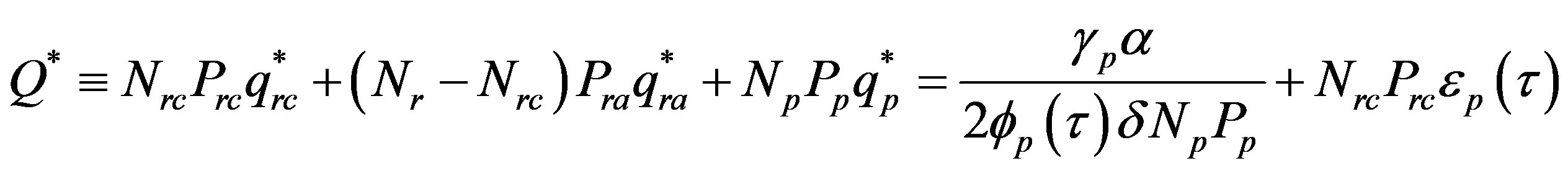

and the equilibrium global emissions are:

. (18)

. (18)

5. Propositions and Concluding Remarks

The equilibrium indicated in equations (15)-(18) leads to the following propositions and concluding remarks.

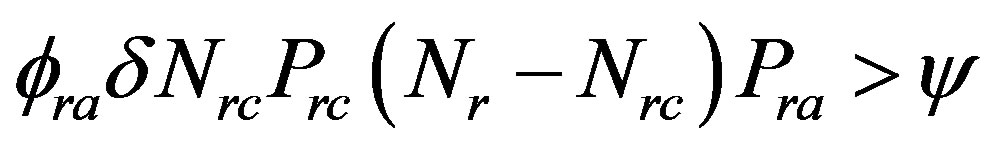

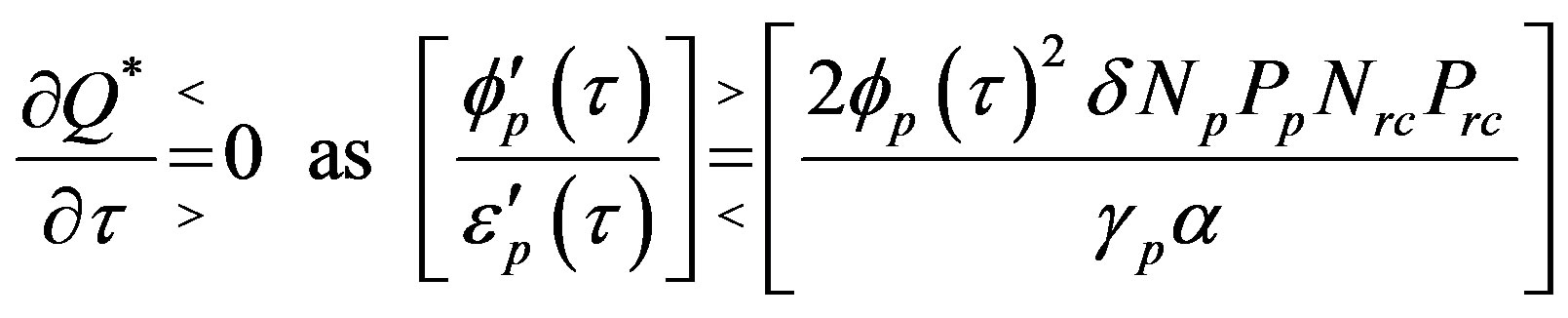

Proposition 1: If

is larger than

then a unilateral implementation of carbon tax and a concerted green investment of the tax revenues by a coalition of rich countries reduce the coalition’s per capita emissions. However, if

then a unilateral implementation of carbon tax and a concerted green investment of the tax revenues by a coalition of rich countries reduce the coalition’s per capita emissions. However, if

is smaller than

then a unilateral implementation of carbon tax and a concerted green investment of the tax revenues by a coalition of rich countries increase the coalition’s per capita emissions. (See Appendix for proof.)

then a unilateral implementation of carbon tax and a concerted green investment of the tax revenues by a coalition of rich countries increase the coalition’s per capita emissions. (See Appendix for proof.)

The effectiveness of the tax in reducing the coalition’s emissions increases with the poor countries’ sense of guilt, but diminishes with the poor countries’ inclination to overstate the moderating effect of the tax on the coalition’s emissions.

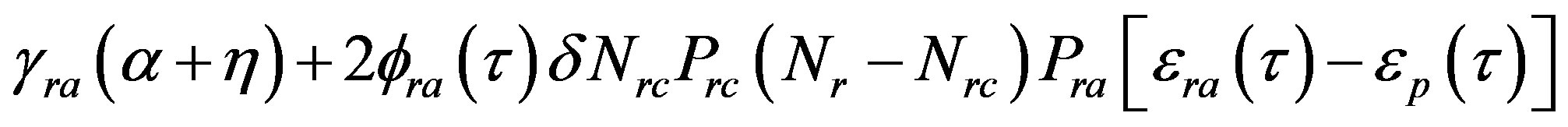

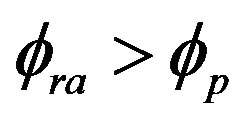

Proposition 2: If

is greater than

then the per capita emission of the abstaining rich countries is larger than the per capita emission in the carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. However, if

then the per capita emission of the abstaining rich countries is larger than the per capita emission in the carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. However, if

is smaller than

then the per capita emission of the abstaining rich countries is smaller than the per capita emission in the carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. (Straightforward from Equation (16))

then the per capita emission of the abstaining rich countries is smaller than the per capita emission in the carbon-tax collecting and investing coalition. (Straightforward from Equation (16))

The possibility of a negative per capita emission differential between the abstaining rich countries and the coalition increases with the abstaining countries’ loss of international reputation stemming from understating the coalition’s per capita emission. It also increases with the poor-countries’ utility from the output facilitated by a unit of emission, weighted by the abstaining rich countries’ relative population and degree of concern about the environment. The said possibility is diminished by the abstaining rich countries’ utility from the output facilitated by a unit of emission. It is also diminished by the coalition-emission’s understatement differential between the abstaining rich countries and the poor countries, amplified by the damage coefficient, by the abstaining rich countries’ population and degree of concern for the environment and by the coalition’s population.

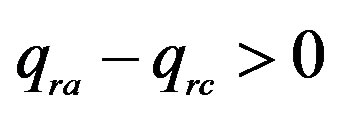

Proposition 3: If

then the global emissions are reduced, not affected, or increased by the carbon-tax set by the coalition, respectively. (See Appendix for proof.)

then the global emissions are reduced, not affected, or increased by the carbon-tax set by the coalition, respectively. (See Appendix for proof.)

This proposition indicates the critical ratio of the poorcountries’ guilt-sensitivity to their inclination to overstate the effect of carbon-tax above which the implementation of carbon-tax by the coalition leads to reduced global emissions.

REFERENCES

- R. H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1960, pp. 1-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/466560

- L. S. Shapley and M. Shubik, “Quasi-Cores in a Monetary Economy with Non-Convex Preferences,” Econometrica, Vol. 34, No. 4, 1966, pp. 805-827. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1910101

- M. L. Weitzman, “Prices vs. Quantities,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 41, No. 4, 1974, pp. 477-491. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2296698

- W. A. Pizer, “Combining Price and Quantity Controls to Mitigate Global Climate Change,” Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 85, No. 3, 2002, pp. 409-434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(01)00118-9

- M. Hoel and L. Karp,“Taxes versus Quotas for a Stock Pollutant,” Resource and Energy Economics, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2002, pp. 367-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0928-7655(02)00014-3

- R. G. Newell and W. A. Pizer, “Regulating Stock Externalities under Uncertainty,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 45, No. 2, 2003, pp. 416-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0095-0696(02)00016-5

- C. Fischer and R.G. Newell, “Environmental and Technology Policies for Climate Mitigation,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2008, pp. 142-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2007.11.001

- T. M. Selden and D. Song, “Environmental Quality and Development: Is There a Kuznets Curve for Air Pollution Emissions?” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1994, pp. 147-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1994.1031

- G. M. Grossman and A. B. Krueger, “Economic Growth and the Environment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 110, No. 2, 1995, pp. 353-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2118443

- A. Diekmann and A. Franzen, “The Wealth of Nations and Environmental Concern,” Environment and Behavior, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1999, pp. 540-549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00139169921972227

- A. Franzen, “Environmental Attitudes in International Comparison: An Analysis of the ISSP Surveys 1993 and 2000,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 84, No. 2, 2003, pp. 297-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540-6237.8402005

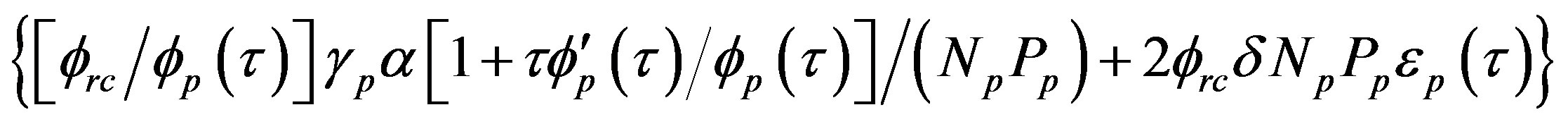

Appendix

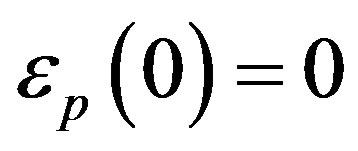

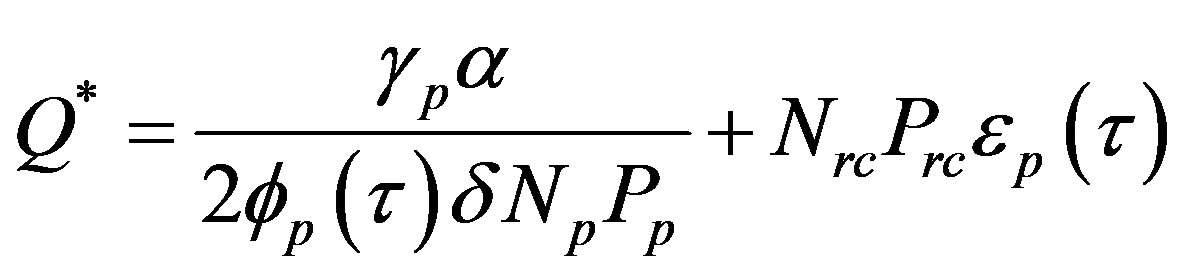

Proof of Proposition 1: From (12),

.

.

Proof of Proposition 3: The equilibrium global emissions are:

.

.

Recalling (15), (16) and (17),

Hence,

.

.

NOTES

1The “environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis” (Selden and Song [8]; Grossman and Krueger [9]) and the “affluence hypothesis” (Diekmann and Franzen [10]; Franzen [11]) suggest that .

.

2When ,

,  can be taken to be proportional to

can be taken to be proportional to  if this ratio represents the exceptionality of abstinence and the power of the coalition.

if this ratio represents the exceptionality of abstinence and the power of the coalition.

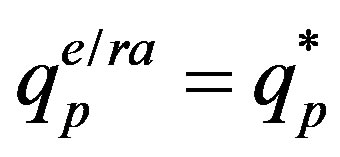

3Equations (15) and (16) are obtained by substituting the right-hand side of (12) into (13) and (14), respectively, and rearranging and collecting terms. Equation (17) is obtained by substituting the right-hand side of equation (16) into equation (12). If entree to, and exit from, the coalition are free and motivated by utility gains, the carbon-tax rate that ensures the stability of  strong coalition is a

strong coalition is a  maintaining equality between the utility of the residents of the coalition and the utility of residents of the abstaining rich countries with equilibrium emissions.

maintaining equality between the utility of the residents of the coalition and the utility of residents of the abstaining rich countries with equilibrium emissions.