Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:42906,11 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.43018

Regaining Normalcy in Relatives of Patients with a Pacemaker

Dan Malm1,2*, Anna Sandgren1,3

1School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

2Department of Internal Medicine, County Hospital Ryhov, Jönköping, Sweden

3Center for Collaborative Palliative Care, Linnaeus University, Växjö/Kalmar, Sweden

Email: *dan.malm@hhj.hj.se

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 November 2013; revised 28 January 2014; accepted 12 February 2014

ABSTRACT

Patients with chronic diseases, such as those with pacemakers, have shown that they have a worsened well-being, which means an increased interest in investigating how relatives of patients with pacemakers experience their situations and how the disease affects their life situations. The aim of this study was to explore the main concerns for the relatives of patients with a pacemaker and how they resolve these issues. A classic grounded theory was used throughout the study for data collection and analysis. Interviews were conducted with ten participants. Striving for normalcy emerged as the main concern for relatives of patients with a pacemaker and was handled through a process of regaining normalcy where the relatives strive to find a way to live as normal as possible. Regaining normalcy is done through developing trust, dwindling and finally life stabilizing, in which they are either holding back or new normalizing. Distinguishing signs are constantly done during the process to quickly notice possible symptoms of the patient. Increased knowledge and understanding of how the relatives of patients with a pacemaker regain normalcy can be used as a guide in order to support and inform the patient as well as their relatives in conjunction with implantation occasions but also in connection with recurring and lifelong follow-up occasions.

Keywords:Grounded Theory; Interviews; Pacemaker; Relatives

1. Background

In Western Europe, 394 million people live with an implanted pacemaker. During the last forty years, the number of pacemaker implantations in Sweden has increased from approximately 100 to 690/million persons a year, with the mean age of approximately 70 years old, and requiring lifelong treatment. The most common indication for the pacemaker implantation is that the patient has an acute onset of fainting together with an atrio ventricular block [1] . The implantation is performed, most often, on the same day as the onset of symptoms, with the patient ready for discharge for home the day after implantation. This short stay hospitalization time is beneficial as it results in fewer infections [2] , as Baman [3] identified in a review that patients with a pacemaker had a lower rate of infection and device malfunction, and that this treatment plan is safe for life threatening arrhythmias [3] . It should be noted that shorter even hospitalisation times can also be negative for these patients as well as their relatives that characterized by high demands to understand the situation and low control to handle it at home [4] . A relative can be described as a hidden patient and life satisfaction of these individuals can often be lower than that of the actual patient [5] . It has been noted that the stress levels of relatives of patients hospitalized can be higher compared with the levels of the actual patients themselves [6] [7] . This may be due to the fact that the relatives of patients with a pacemaker may experience a heightened level of anxiety. In addition to this, a lack of information, uncertainty regarding outcomes, emotional turmoil, need for support, depression and psychosomatic symptoms may also be experienced. These symptoms may last for up to a year after the implantation, and they are similar to those patients who have experienced a myocardial infarction [8] .

The modern pacemaker system of today, with an operational time of up to 15 years, is checked one to two times per year [9] . A patient with a pacemaker and his family is considered to be able to live a normal live even if strong magnetic fields should be avoided because these can inhibit or stimulate the pacemaker. Furthermore, there is a great deal of knowledge available today about the technical performance of pacemakers and the biophysical life of pacemaker patients, but more information is needed regarding these individuals’ own experiences of their life situation [9] -[11] . Knowledge about the life situation of patients with pacemakers is largely based on measures using different life quality instruments from the perspective of the researcher [12] . Berry et al. [13] show in their qualitative study that the confidence which female pacemaker patients have in pacemaker treatment is partially due to emotional feelings regarding the pacemaker [13] . However, shorter care times and quick discharge conversations should be negative for patients as well as relatives when they have difficulty understanding what it is that caused the implantation and how life can further be lived. The patient thus leaves the hospital with unanswered questions and relatives can, because of this, feel worry when the onset is often very dramatic and the patient has at their homecoming difficulty in explaining what has happened [9] [11] .

This can in many cases mean that relatives of patients with chronic diseases in the family have questions of an emotional, existential, and practical nature [14] , which is why relatives need their own support adapted to their personal needs when they have experienced everything from insecurity to security. It has earlier been described that relatives can be overprotective and that they feel inadequate in the new situation [10] [11] [15] [16] .

Studies on relatives of patients with chronic diseases have shown that they have worsened well-being [17] , and it is therefore of interest to investigate the situations of relatives of patients with pacemakers and how the disease affects their life situations. The aim of the present study was therefore to develop a classic grounded theory about relatives of patients with a pacemaker. The research question guiding the study was: What is the main concern for relatives of patients with a pacemaker and how do they resolve it?

2. Material and Methods

Classic grounded theory methodology aims to conceptualize patterns of human behavior [18] [19] , and it is behaviors, not people, that are categorized [20] . Interviews with relatives of patients with a pacemaker were conducted between 2010 and 2012 in a medium-sized county serving 320,000 individuals in southern Sweden. The sample was based on theoretical sampling [19] where data were collected in order to refine and elaborate emergent categories and later on with a focus on categories related to the core concept to develop the emerging theory. Seven women (39 - 77 years, median 53) and three men (51 - 82 years, median 57) were finally included. Two of them had compulsory school education, four had high school level education, and four had university education. Eight participants were married or were cohabiting with the patients, one was sister to a patient and the other one was a daughter and they did not living with the patient.

The relatives were interviewed in their homes, except one which was interviewed at the relative’s workplace. The interviews lasted between 40 and 90 minutes and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also written after each interview as a basis for data analysis. The interviews were more like open-ended conversations and began with the invitation, “Tell me what it is like to live as a relative of a person with a pacemaker.” In classic grounded theory, data collection and analysis occur simultaneously [19] . This means that data analysis was done after each interview and guided further data collection. New ideas emerged during the analysis of what to ask in the following interviews, for example questions about the time before pacemaker implantation, the given information at hospital for the relatives, how their lives had been affected, relationships to friends, and thoughts about the future. Later on when the core category had emerged, more specific questions were asked to refine and elaborate emergent theory.

Conceptual memos were written throughout the whole analytic process to capture creative ideas about categories and the emerging theory [19] . The first phase of the analytic process was open coding, and the data were coded line by line after each interview. A set of questions were asked about the data: What is this data a study of? What category does this incident indicate? What is actually happening in the data? What is the participants’ main concern? How do they continually resolve this concern? These questions helped the researchers to avoid description, and instead stay theoretically sensitive and conceptualize [18] . The initial codes were compared to newly generated concepts, which were compared to other concepts and finally the core concept emerged. This core concept is central in grounded theory and explains the main concern for the participants and how they resolve it. In the selective coding phase, further data collection and coding through theoretical sampling were done in order to delimit, so that only categories which were related to the core concept were left. The coding continued until theoretical saturation was reached, which means that same categories continued to emerge while analyzing new data [19] . In the theoretical coding phase, relationships between the categories and the core concept emerged through hand sorting of the memos. The theoretical codes can be of different kinds; in this study the theoretical code of basic social process emerged, and the theory is therefore built up around this code. After the sorting of the memos, the theory was written; in this stage the elements of time, place and people were left behind, and the theory was written as conceptually abstract [18] [19] . According to classic grounded theory, the literature review was not done until the substantive theory was formulated [18] . The literature was then used as data in the constant comparative process to refine the theory.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to the interviews. They were informed about the study both verbally and in writing, about the aim of the study, as well as about the possibility of discontinuing their participation at any time without the need to give any reason for this [21] . They were also informed that all material would be treated confidentially. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee, Linköping University, Linköping Sweden (Dnr: 98095).

3. Results

Striving for normalcy emerged as the main concern for relatives of patients with a pacemaker.

The relatives know that the pacemaker is life supporting, and they are well aware of its role but worry that it affects their family life as well as hinders them in living as usual and doing normal activities. This worry and insecurity affect the behavior of all involved, and the relatives deal with the wish for normalcy differently depending on their personality and their earlier experiences. The pacemaker may restrict the patients’ energy but also restrict the relatives psychologically. Although they might realize that they cannot live in the same way as before, they are striving towards normalcy.

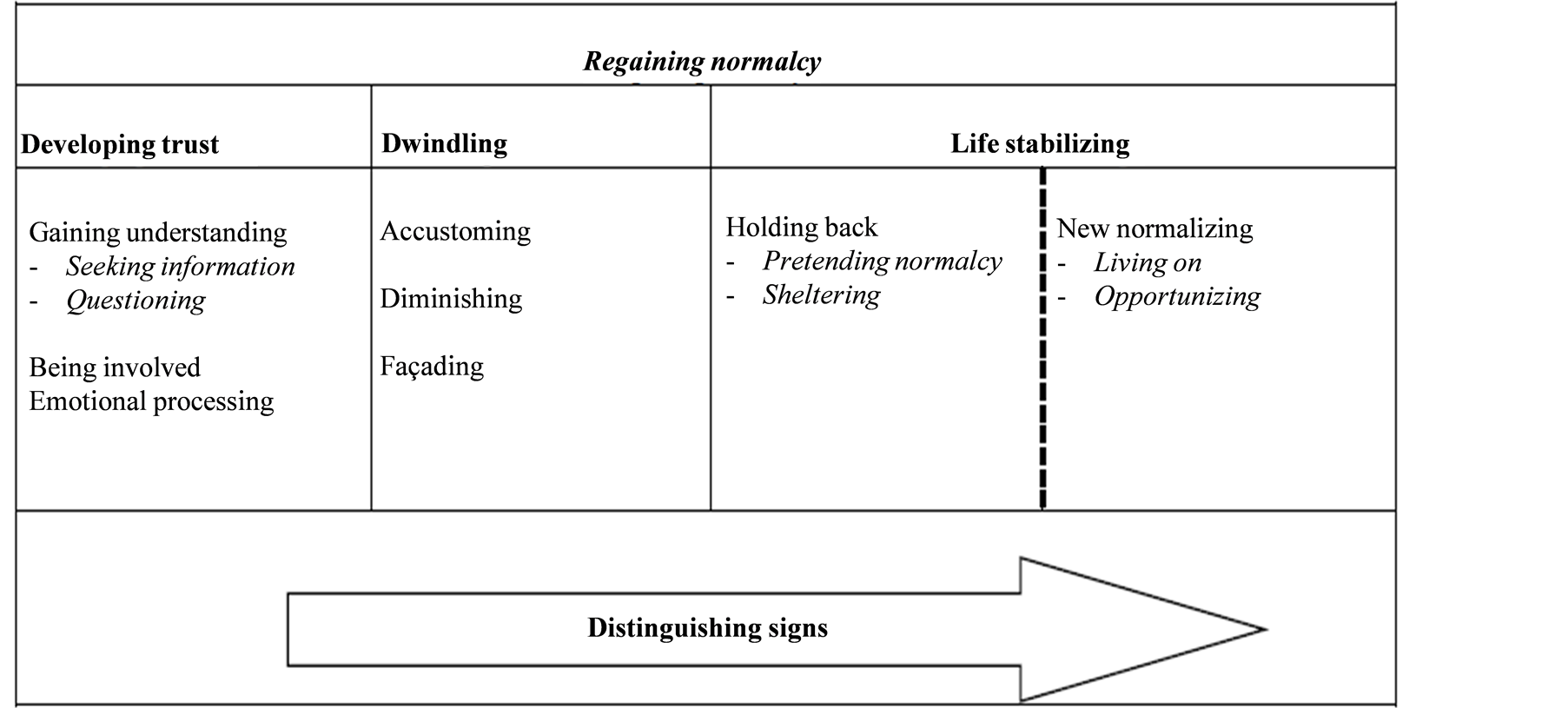

Striving for normalcy is handled through a process of regaining normalcy and is done through developing trust, dwindling and finally life stabilizing in which they either are holding back or new normalizing. During the whole process relatives are constantly distinguishing signs to quickly notice if something is not right (see Figure 1). Relatives need to go through the different stages in the process to be able to regain normalcy although this process may be started all over again if something happens that threatens normal life, for example new symptoms, complications, or another diagnosis.

3.1. Distinguishing Signs

Distinguishing signs means interpreting signs of insecurity and symptoms, such as dizziness and tendency of fainting in the patient. This is done throughout the whole process of regaining normalcy; at first it is done more

Figure 1. The theory regaining normalcy.

consciously, but as time goes by it is done more and more subconsciously. Distinguish signs is easier in close relationships when they have learned to distinguish the body language and nonverbal signs. Through being attentive and guarding, signs are distinguishing. This can be done surreptitiously through being watchful for changes, or it can be done more openly through controlling and asking direct questions, for example “How are you feeling? I can see that you are not feeling okay.” The patients’ status and condition maneuver daily life for the relatives. Living with a patient with a pacemaker is a shared experience, but at the same time they are standing aside. What affects the patients also affects the relatives; for example when the pacemaker “goes on” and causes feelings of discomfort for the patient, this also affects the relatives’ feelings and may increase their worry. Having knowledge of this and its causation helps the relatives to handle the situation and distinguish signs.

When distinguishing signs there is a risk of overprotecting. Caused by a sincere concern, they might overprotect which may hamper a normal life and prevent the patients from performing activities which they actually are able to do. Thus, there must be a balance when distinguishing signs, so that normal life is not restrained by overprotecting.

3.1.1. Developing Trust

Developing trust means gaining trust in the pacemaker but also for life, that life goes on despite what has happened. Developing trust is done through gaining understanding, being involved, and emotional processing.

3.1.2. Gaining Understanding

Gaining understanding is done through seeking information and questioning. This can be done through contact with health professionals but also through friends and social media such as Facebook, Twitter and blogs.

3.2. Seeking Information

Which kind of information is needed depend on how the patient has received the pacemaker. If the situation was dramatic, information is sought about what happened. “It was so dramatic; it came as a chock. Did not know that he was so sick, and lack of information made it worse.” If the patient received the pacemaker after being sick for a while, another kind of information is needed. The relatives sometimes do not realize the seriousness of the patients’ symptoms since they appeared slowly, not affecting the patients’ lives so much. When realizing the seriousness it can lead to insecurity. Receiving information can therefore both increase and decrease the security. When developing trust, there is a risk of over-faithing, which means having overconfidence in what the pacemaker actually can do. Taking for granted that everything will be okay since the patient now has a pacemaker and goes to regular check-ups. This overconfidence is often caused by a lack of knowledge in how a pacemaker works. There might be unrealistic expectations that the pacemaker will protect, for example, from getting a heart attack.

3.3. Questioning

Questioning the reliability of the pacemaker and if it will work as it is supposed to is a way to develop trust, such as questioning if the pacemaker is correctly calibrated and that the battery will last the expected time. “Could it handle the change from year 1999 to 2000? I was worried even if the doctor said it would be okay.” There can also be worries that electronic machines, for example cell phones, microwaves oven and security checks at airports, will affect the pacemaker and change its technical adjustments.

If the person had a great deal of symptoms before receiving the pacemaker and now has recovered, it eases and can also speed up the process of regaining normalcy. “Life goes on; you leave the worry and you put your trust in the pacemaker, in the technique.” Through testing boundaries the patients are stretching the limits to see if they can deal with the new experience and how far they can go before stopping. During this testing of boundaries, the relatives are constantly distinguishing signs of discomfort or other symptoms in the patients. Even though questioning leads to trust, there might still be a nagging feeling of distrust in the technique. This feeling of not trusting 100% may decrease as time passes.

3.3.1. Being Involved

Being involved means being included in the situation, such as attending follow-ups. The wish to be involved does not depend so much on age; it depends more on the kinds of their relationships. When patients do not want any involvement from relatives, this can cause feelings of passivity and being left out. Being excluded hinders them to support or to be involved as much as wanted, which then may lead to feelings of powerlessness.

Even when the patients want the relatives to be involved, the relatives themselves may not want to be included, which can be caused by distancing or surrendering. Relatives may distance themselves caused by difficulties in handling all of the received information. This can actually be a way to protect themselves. “When you feel that something is not right, you might try to shield yourself and pretend that everything is okay. What you do not know, you do not have to worry about.” Relatives may also surrender to care, which means that they put all of their trust in the health professionals leading to security and the relief of not being responsible.

3.3.2. Emotional Processing

Through emotional processing the relatives process what happened, and their need for this depends, for example, on if the situation when the patient received the pacemaker was dramatic or not. If it happened during dramatic circumstances and the situation was life threatening, professional help might be needed to process, while others may view the new situation as a relief and can let go of their feelings without further notice. One explanation for this could be that they see a total transformation in the patient, a total change from being so sick to now being healthy; it is as if “a new person is born.” This transformation of the patients’ situations facilitates the emotional process and the development of trust. A lack of emotional processing, on the other hand, leads to ruminating and imagining stories about what actually happened.

3.3.3. Dwindling

Dwindling means minimizing the impact of the new situation as a way to regain normalcy and is done through accustoming, diminishing and façading.

3.3.4. Accustoming

By accustoming, an adjustment to the new situation is done. Depending on how their life was before, they have more or less of an ease of ability to accustom. When the persons have been sick for a long time, the pacemaker may be seen as a gift which gives them a new life. This can differ from when healthy people suddenly become ill. Then the relatives have to adjust, both to the fact that the patients were close to death but also now that they have a pacemaker. In either way, accustoming is more easily done when the relatives have processed what happened and feel involved. Accustoming can also be facilitated by time. “After a while you do not think about the pacemaker; it just is there, and you have total trust in it.” Getting back to social networking can facilitate the accustoming process although handling expectations and questions from friends can be perceived as difficult. Accustoming leads to feelings of comfort and safety in addition to making the focus shift from the pacemaker to regaining a normal life.

3.3.5. Diminishing

Diminishing the role of the pacemaker in their life is one step towards normalcy. Although there is an awareness of its existence, they will not let it affect life more than necessary. At first, the pacemaker affects life through some restrictions; the patients are, for example, not allowed to lift heavy objects. As time passes, however, the interference in their lives is diminished. The pacemaker is seen as a peripheral issue and is considered as a constant companion that is living together mutually: “It is like living with an extra companion.” Although the scar is a constant reminder of the pacemaker, it can go several days without thinking about it. “The pacemaker just is there, a part of his life, but does not impact on life.” It is in the back of their mind, emerging when distinguishing symptoms or discomfort, or when it is time for the patients’ check-ups and change of battery. It can also be a reminder when travelling, passing through security checks, which can cause insecurity.

3.3.6. Façading

Façading means not showing their worry since it may transmit to the patients. The relatives want to be regarded as strong, “When one is weak, the other person needs to be strong.” This includes taking command and maybe taking the leading role during occasions when the patients are not feeling well. When meeting friends, the façading may be used since they do not want pity; they rather want to act normal and be regarded as normal again. When friends still regard the persons as sick, it decreases the process of regaining normalcy. Through façading the relatives are holding up a façade so that they can regain normalcy.

3.3.7. Life Stabilizing

Life stabilizing means shifting focus and finding a way to live as normal as possible again and can either be done through holding back or through new normalizing. Which strategy the relatives choose depends on their developed trust and the dwindling of the situation. There can be a transition from holding back over to new normalizing for example if support is received, support which can lead to increased understanding and feelings of security. On the other hand, there can be a transition from new normalizing to holding back if new symptoms appear or if there are problems with the pacemaker.

3.3.8. Holding Back

Holding back is done when distrusting the pacemaker or the new situation, caused by a lack of knowledge or uncertainty in how to handle the situation. If the relationships between relatives and patients are strained, it hinders their ability to regain normalcy. Holding back is done through pretending normalcy and sheltering.

3.4. Pretending Normalcy

When pretending normalcy, the relatives act as if everything is as usual, although they still are grappling with trusting the pacemaker and the situation. A gnawing feeling of worry affects the relationships and their social life, although they try to live on as normal. Pretending normalcy can be seen as a protection but also as an invisible burden, which can contain fear of the future or that something bad will happen to the patient. This is not obvious every day but emerges periodically while distinguishing signs and finding alarming signs such as dizziness and fainting.

Pretending normalcy is a way to hold on to life but may lead to a decreased amount of social life since they keep on façading. They can have difficulties in handling the worry and fear of friends who act “as if death is coming any minute.” Being different and not a “normal family” can affect their social network, which leads to isolation instead of confronting attitudes and values held by friends. A change in the social network may be a consequence with new friendships where these friends do not know about the patient’s pacemaker.

3.5. Sheltering

Sheltering is a balance of preventing a bad thing from happening and hindering the patient in living life fully. Distrust leads to loss of control and to restrictions in life, although the relatives dissipate these thoughts through distraction. This includes supervising what the patients are doing and deciding what they are allowed to do or not. The desire to shelter may therefore lead to overprotecting but is justified by their concern for the well-being of the patients. They fear that symptoms might appear which will rule their lives and hinder them from regaining normalcy. When distinguishing signs, the relatives might therefore over-interpret signs, leading to even more overprotection. These feelings can be a torment when being overprotective and distressing oneself about everything that might happen.

Sheltering may decrease social life and avoidance of situations which they think can lead to problems. Avoiding travelling to warm countries even though the patients actually want to go. If the relatives agree to travel, they plan for possible situations that might happen, such as planning their stay close to a hospital; this includes thinking through all possible situations that might happen in order to be prepared. As time passes, the relatives may create trust in the pacemaker, which finally leads to a transition to new normalizing.

New Normalizing

New normalizing is possible when trusting the pacemaker and the situation. Through living on and opportunizing, a new normality is created. The relatives may believe that they are returning to normal, but it is in reality a new normalcy. Returning back to the “old normality” is not possible since the pacemaker always will be there as a companion throughout life.

3.6. Living on

When living on, relatives have a total trust, which makes it easier to regain normalcy: “No idea to distrust even if there is a risk that something might happen.” An interruption in their new normal living can be when it is time for yearly check-ups, which then can cause feelings of insecurity since they then are being reminded of what happened. Living on involves regaining social status; it is important to be seen and looked at as a normal family which can do normal things. Living on as normal again can affect others’ attitudes and expectations on the family. Social networking protects but can also cause overprotection, which leads back to façading.

3.7. Opportunizing

Opportunizing means taking chances to enjoy life; in looking back, they realize that they are blessed with a new chance for normalcy. When opportunizing the relatives are allowed to plan in advance, but if things are not going as planned, they do not become disappointed. Through distinguishing signs the relatives can be aware if something unexpected happens and take care of it immediately. There is awareness that life can be disrupted, and they therefore need flexibility in normal life. There might be a risk of overdoing it since they want to live as before. Through moment capturing, they take one day at a time since it is not helpful to worry about the future. Especially if the patients had been very affected by their disease, the relatives now see new possibilities in life thanks to the pacemaker. When the family is going through a rough time, they might joke about it i.e., “Now you have to put on your turbo (the pacemaker).”

4. Discussion

The choice of classic Grounded Theory was appropriate, since it is a method used in areas where there have not been studies done [18] . The emergent nature of classic grounded theory methodology enabled the discovery of the main concern, which would unlikely have been done with methods focusing on predefined problems and questions [18] . The theory of regaining normalcy does not represent the relatives’ entire being or doing, and they are surely engaged in other patterns of behavior that need to be further explored.

A grounded theory should be judged by fit, workability, relevance, and modifiability [18] . Fit means how closely the concepts fit with the incidents that they are representing. Relevance means that the real concern of the participants has emerged and therefore evokes grab. Workability means that it is explained how the concern is resolved and with much variation. Modifiability means that the theory can be modified. Grounded theory generates hypotheses which are conceptual and therefore can be applied to any relevant time, place and people [19] . Through constant comparison with new data, the theory can be modified to other substantive areas. So although this theory emerged from the context of the pacemaker, the theory might well be expanded to other areas where striving for normalcy exists, contributing to an understanding of how people deal with their desire to regain normalcy.

Striving for normalcy emerged as the main concern in this first study on relatives of patients with a pacemaker. How relatives handle their wish for normalcy depends on the situation when the patient received the pacemaker, if the situation was dramatic with an acute onset of unconsciousness or non-dramatic, with periods of dizziness, or maybe without any symptoms at all. This result is consistent with previous studies of how relatives of patients with chronic diseases experience time from the onset to the start of the treatment [22] [23] .

When disease, such as dizziness or fainting, disturbs the individual’s ability to perform daily activities, often the husband/wife takes over a large portion of the responsibility for the patient, which an earlier study about relatives of patients with heart failure also showed [24] .

During the first year after the pacemaker implantation, overprotection is one of the most common strategies used in order to handle worry and fear about the symptoms of dizziness and fainting being able to return. Here it emerged, as well as in a study on the chronically ill, that the relatives must be strong and adopt a leadership role in order to ease the worry that the patient experiences. This can be perceived as difficult when the relatives feel the same worry and therefore have an increased risk to have the onset of a stroke and even die early in heart disease [25] .

A study showed that female relatives to older family members with chronic illnesses, experience more stress than men which can be caused by that they feel a societal responsibility of adopting duties and responsibility, which can lead to an overwhelming caregiver burden that thereby initiates a hidden patient [26] .

To be able to regain normalcy, the relatives have to accustoming to the new situation and sometimes façade their own fear and worry. Flemme [27] showed that patients that were treated with the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) lived with daily insecurity. Despite this, it was important to perform daily activities – even if they were performed in a somewhat limited way [27] . When accustoming and diminishing the roll of the pacemaker, it is important for the relatives that the daily activities are able to continue as before but at the same time they are distinguishing signs to quickly notice symptoms that the patient had before the pacemaker implantation.

Critical for regaining a normal life is that the relatives dare to trust the pacemaker. During the first time after the implantation, the relatives experience a time pressure as a result of that the patients want test their limits for what they now can perform compared with previously. In this study as in Kamphuis’ [28] study of patients who have received the ICD, one of the most important issues was to have clarity in how the first year after the implantation will be [28] . The relatives seeking information through medical care services, and converse with other relatives about if it really is possible to trust that the pacemaker takes over that which the healthy heart was able to do before. Also if the pacemaker does not function as planned, which symptoms can then be expected to occur and how can they distinguish these symptoms? Previous study show if the medical care services meet the relatives’ search for information from a person-centered approach, it allows the opportunity for an in-depth conversation that gives increased knowledge, which causes the relatives’ worry to decrease [29] . Gaining understanding via social media is additionally today an increasingly feasible way to acquire knowledge when neither the medical care services nor friends and acquaintances have the answers they are seeking. It is important that the medical care services meet this need [30] . The relatives perceive the annual checks at the pacemaker ward as an important part of the security in order to develop trust and certify that everything is fine. However, there is a difficulty in not ceasing to distinguish the signs of for example, the dizziness attacks as before the implantation, so they continue in “secrecy” in order to see if these signs have disappeared or not. Mårtensson et al. [31] showed in their study that follow-up via the telephone was meaningful primarily for older relatives with a social network that was not sufficient [31] . This should mean that it can be very beneficial to even relatives of patients with a pacemaker to have similar telephone contacts with medical care services principally during the first year when there are many questions and there is much insecurity over if the pacemaker works in an excellent way. This contribution can be critical for well-being, which also should be considered given that the patient has a lifelong treatment that is never able to be cancelled.

Remembered the turn of the millennium and the societal debate about the risk that computers would “lose their memory” and what would then happen to all of those with pacemakers [32] , some of the relatives perceived this time as dramatic and difficult but attempted to living on and pretending normalcy as usual. A general fear is still experienced regarding using the cell phone. A review has shown that they can disturb the functions of the pacemakers [33] , although several studies have shown that today’s cell phones do not interfere with the pacemakers implanted in the last 10 years, which means that the patients can feel entirely safe [34] -[36] . When the relatives dwindle situations that are perceived as inhibiting or limiting for the patient, it gives security in daring to living on as in the past, before the pacemaker implantation. So through both relatives and patients receiving more knowledge and thereby daring to try and test varying situations, it gives security and opportunities to regain a normal life.

In order to stabilizing life, the relatives use different strategies to handle and solve daily situations. Life stabilizing has earlier been used in the context of family with cancer to explain how the family handle their new situation [37] . In our study, life stabilizing emerged as two different ways to regain normalcy, depending on the developed trust in the pacemaker and the new situation. When relatives are holding back and use sheltering as a protection, it can be compared to not have anyone to share their troubles with. They feeling isolated and could not participate in social activities in the same way as previously [24] [31] . It emerges in our study as well as in Birkeland et al. [38] that the relatives must be responsive to the needs that the patient have and use different strategies [38] , such as sheltering through holding back. This worked well by the relatives toning down the importance of meeting their friends as often as before when they know that worry and fear can be caused by social contexts where the patient feels insecure. The relatives thought that it worked really well even if this overprotection was stressful for both partners, which also emerged in an earlier study on how couples handled their situation in connection to a myocardial infarction [39] . If relatives hold back own opinions and feelings it leads to frustration and reduces respect of own space in the relationship [40] . However, even the opposite of holding back emerged, namely living on and fully trusting the function of the pacemaker and together continuing to live the life that they previously had lived. This means that the relatives instead live here and now to protect normal life in their relationship, even if there is worry that the patient would overexert himself or herself. This could be compared to moment-living, which means living in a total presence and making the best out of every situation to maximize the well-being [41] .

Bergbom [42] showed in his study that the relatives have an important role when the patient has made it through a life threatening condition, such as cardiac arrest, through their presence increasing the patient’s feeling of strength and support [42] . There is a strong connection between leisure activities and social relationships in order to new normalizing, and as a measure of welfare opportunizing the possibility of travelling together is often used [43] . This means that the relatives have an important task also so that they will function as a relative and be able to regain normalcy. There has long been evidence that is known as a fact that good social relationships are significant for the welfare of the individual in several respects [44] . Close and trustful relationships give a basis for security in life, but interpersonal relationships also mean a great deal for connection with other people as well as meaningfulness in life. Relationships, in the form of a social network, can also be a significant, supportive resource for relatives as well as the patient, chiefly when the care times at the hospital are becoming shorter, and this can create pressing social life situations, which several studies have shown [43] [45] .

5. What’s New: Summary and Implications for Practice and Research

• Relatives to patients with pacemaker need guidance (of the health care professional), support, and skills to manage the life situation

• Relatives seek characters for supporting the patient

• Relatives are developing trust that the pacemaker was the right treatment

• Relatives solve daily situations by different strategies such as shifting focus through holding back

• Future longitudinal studies would be of interest in order to obtain in-depth knowledge on how relatives to patients with pacemaker increased knowledge and understanding of the effect on daily life can be used as guidance in order to support and inform the relatives in conjunction with implantation occasions but also in connection with recurring (ongoing throughout life) follow-up occasions

• This is the first study that contributes knowledge about relatives to patients with pacemaker.

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Jönköping County Council, Sweden.

References

- European Society of, C., et al. (2013) ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: The Task Force on Cardiac Pacing and Resynchronization Therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in Collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace, 15, 1070-1118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/europace/eut206

- Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU). Antibiotikaprofylax Kapitel 6 2011 [cited 2012 12-10] (in swedish).

- Baman, T.S., et al. (2011) Safety of Pacemaker Reuse: A Meta-Analysis with Implications for Underserved Nations. Circulation. Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 4, 318-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.110.960112

- Karner, A.M., Dahlgren, M.A. and Bergdahl, B. (2004) Rehabilitation after Coronary Heart Disease: Spouses’ Views of Support. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46, 204-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02980.x

- Lukkarinen, H. and Kyngas, H. (2003) Experiences of the Onset of Coronary Artery Disease in a Spouse. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2, 189-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00062-8

- Thomson, P., et al. (2013) Patients’ and Partners’ Health-Related Quality of Life before and 4 Months after Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery. BMC Nursing, 12, 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-12-16

- Woloshin, S., et al. (1997) Perceived Adequacy of Tangible Social Support and Health Outcomes in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. The Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12, 613-618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07121.x

- Frasure-Smith, N., et al. (2000) Social Support, Depression, and Mortality during the First Year after Myocardial Infarction. Circulation, 101, 1919-1924. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.16.1919

- Malm, D., Karlsson, J.E. and Fridlund, B. (2007) Effects of a Self-Care Program on the Health-Related Quality of Life of Pacemaker Patients: A Nursing Intervention Study. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 17, 15-26.

- Rassin, M., Zilcha, L. and Gross, D. (2009) “A Pacemaker in My Heart”—Classification of Questions Asked by Pacemaker Patients as a Basis for Intervention. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 56-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02432.x

- Malm, D. and Hallberg, L.R. (2006) Patients’ Experiences of Daily Living with a Pacemaker: A Grounded Theory Study. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 787-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105306066642

- Malm, D., et al. (2003) Health-Related Quality of Life in Pacemaker Patients: A Single and Multidimensional SelfRated Health Comparison Study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 17, 15-26.

- Beery, T.A., Sommers, M.S. and Hall, J. (2002) Focused Life Stories of Women with Cardiac Pacemakers. West Journal of Nursing Research, 24, 7-23; Discussion 23-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01939450222045680

- Brannstrom, M., et al. (2007) Being a Close Relative of a Person with Severe, Chronic Heart Failure in Palliative Advanced Home Care—A Comfort but Also a Strain. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 21, 338-344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00485.x

- Beach, E.K., et al. (1992) The Spouse: A Factor in Recovery after Acute Myocardial Infarction. Heart & Lung, 21, 30-38.

- Timmins, F. and Kaliszer, M. (2003) Information Needs of Myocardial Infarction Patients. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing: Journal of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Nursing of the European Society of Cardiology, 2, 57-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1474-5151(02)00089-0

- Pihl, E., et al. (2005) Depression and Health-Related Quality of Life in Elderly Patients Suffering from Heart Failure and Their Spouses: A Comparative Study. European Journal of Heart Failure, 7, 583-589. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.07.016

- Glaser, B. (1998) Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Sociology Press, Mill Valley.

- Glaser, B. (1978) Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Sociology Press, Mill Valley.

- Glaser, B. (2001) The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description. Sociology Press, Mill Valley.

- Frye, R.L., et al. (2009) Ethical Issues in Cardiovascular Research Involving Humans. Circulation, 120, 2113-2121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752766

- Nygardh, A., et al. (2011) Empowerment in Outpatient Care for Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease—From the Family Member’s Perspective. BMC Nursing, 10, 21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-10-21

- Pihl, E., Fridlund, B. and Martensson, J. (2010) Spouses’ Experiences of Impact on Daily Life Regarding Physical Limitations in the Loved One with Heart Failure: A Phenomenographic Analysis. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20, 9-17.

- Karmilovich, S.E. (1994) Burden and Stress Associated with Spousal Caregiving for Individuals with Heart Failure. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 9, 33-38.

- Haley, W.E., et al. (2010) Caregiving Strain and Estimated Risk for Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease among Spouse Caregivers: Differential Effects by Race and Sex. Stroke: A Journal of Cerebral Circulation, 41, 331-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568279

- Hooyman, N.R. and Gonyea, J.G. (1999) A Feminist Model of Family Care: Practice and Policy Directions. Journal of Women & Aging, 11, 149-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J074v11n02_11

- Flemme, I., et al. (2011) Uncertainty Is a Major Concern for Patients with Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators. Heart & Lung, 40, 420-428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2011.02.003

- Kamphuis, H.C., et al. (2004) ICD: A Qualitative Study of Patient Experience the First Year after Implantation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 1008-1016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01021.x

- Paul, F. and Rattray, J. (2008) Shortand Long-Term Impact of Critical Illness on Relatives: Literature Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 276-292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04568.x

- Crowe, A. (2011) The Social Media Manifesto: A Comprehensive Review of the Impact of Social Media on Emergency Management. Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning, 5, 409-420.

- Martensson, J., Dracup, K. and Fridlund, B. (2001) Decisive Situations Influencing Spouses’ Support of Patients with Heart Failure: A Critical Incident Technique Analysis. Heart & Lung, 30, 341-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mhl.2001.116245

- Dassen, W.R., et al. (1999) The Impact of the Millennium Problem on Implantable Pacemakers and Defibrillators. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology: PACE, 22, 517-520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00480.x

- Carranza, N., et al. (2011) Patient Safety and Electromagnetic Protection: A Review. Health Physics, 100, 530-541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/HP.0b013e3181f0cad5

- Ismail, M.M., et al. (2010) Third-Generation Mobile Phones (UMTS) Do Not Interfere with Permanent Implanted Pacemakers. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology: PACE, 33, 860-864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02707.x

- Tiikkaja, M., et al. (2012) Electromagnetic Interference with Cardiac Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators from Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields. Europace, 15, 388-394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/europace/eus345

- Hayes, D.L., Wang, P.J., Reynolds, D.W., Mark Estes, N.A., Griffith, J.L., Steffens, R.A., Carlo, G.L., Findlay, G.K. and Johnson, C.M. (1997) Interference with Cardiac Pacemakers by Cellular Telephones. The New England Journal of Medicine, 336, 1473-1479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199705223362101

- Jussila, A.L. (2008) Stabilising of Life: A Substantive Theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 7, 29-41.

- Birkeland, A.L., Rydberg, A. and Hagglof, B. (2005) The Complexity of the Psychosocial Situation in Children and Adolescents with Heart Disease. Acta Paediatrica, 94, 1495-1501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08035250510037272

- Coyne, J.C. and Smith, D.A. (1991) Couples Coping with a Myocardial Infarction: A Contextual Perspective on Wives’ Distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 404-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.404

- Coleman, C.I., Coleman, S.M., Vanderpoel, J., Nelson, W., Colby, J.A., Scholle, J.M. and Kluger, J. (2012) Factors Associated with ‘Caregiver Burden’ for Atrial Fibrillation Patients. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 66, 984-990. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02996.x

- Sandgren, A., Thulesius, H. and Petersson, K. (2010) Living on Hold in Palliative Cancer Care. The Grounded Theory Review, 9, 79-100.

- Bergbom, I. and Askwall, A. (2000) The Nearest and Dearest: A Lifeline for ICU Patients. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: The Official Journal of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses, 16, 384-395.

- Tidenman, M. (2000) Normalization and Categorization-On Disability Ideology and Welfare Policy in Theory and Practice for Intellectually Disabled Persons. In: Tidenman, M., Ed., Student litteratur AB, Lund.

- Konlaan, B.B., Bygren, L.O. and Johansson, S.E. (2000) Visiting the Cinema, Concerts, Museums or Art Exhibitions as Determinant of Survival: A Swedish Fourteen-Year Cohort Follow-Up. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 28, 174-178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/14034948000280030501

NOTES

*Corresponding author.