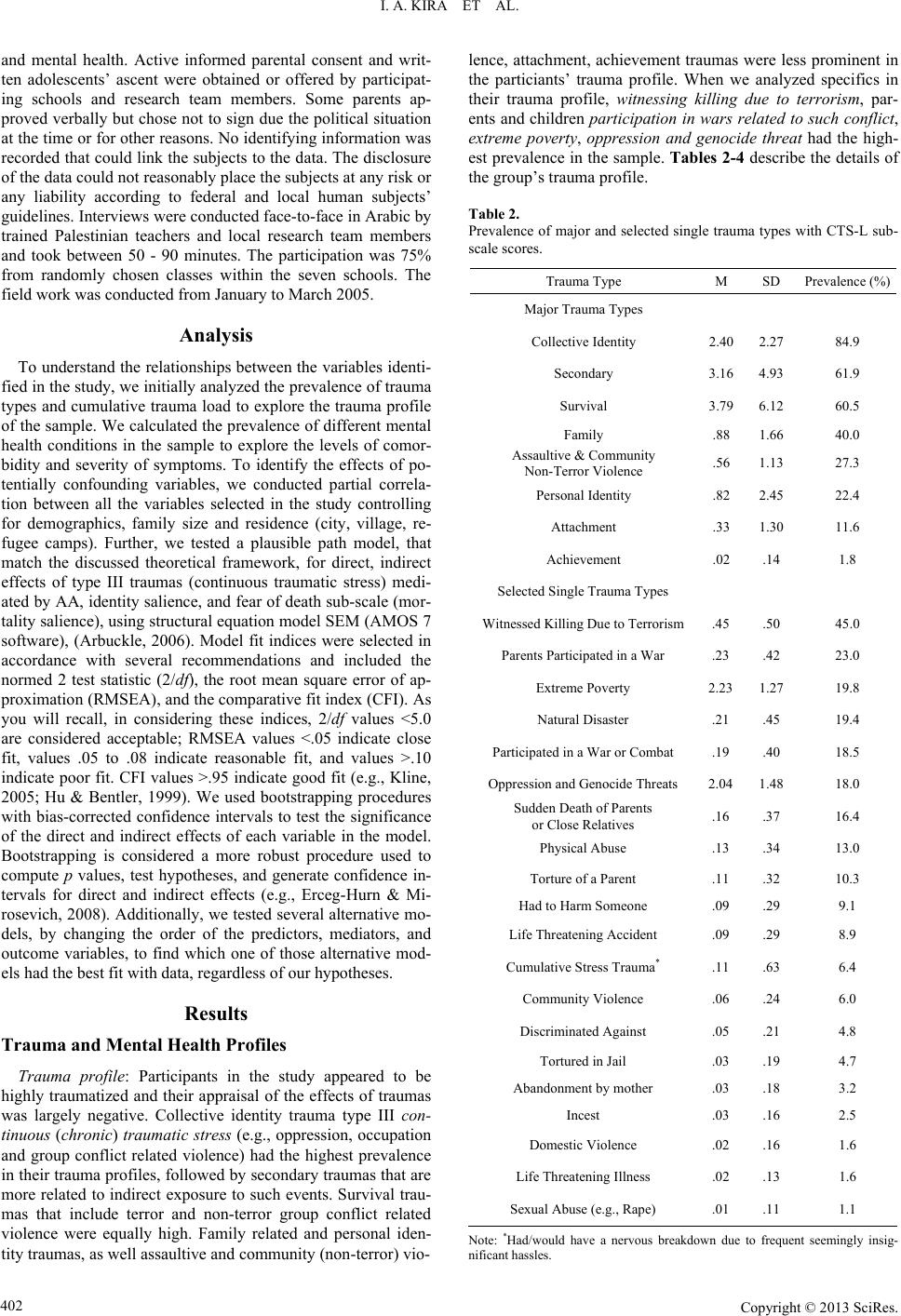

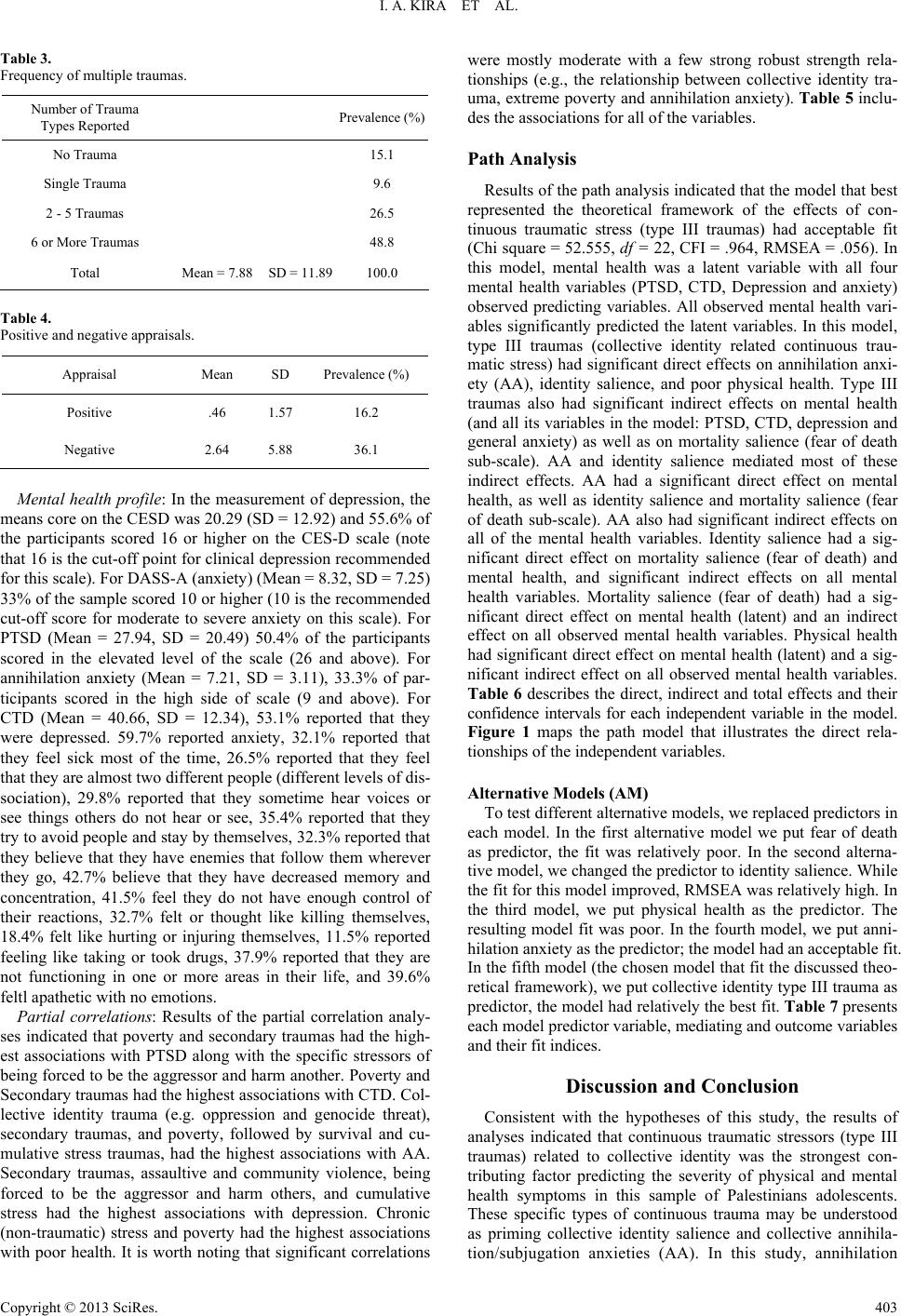

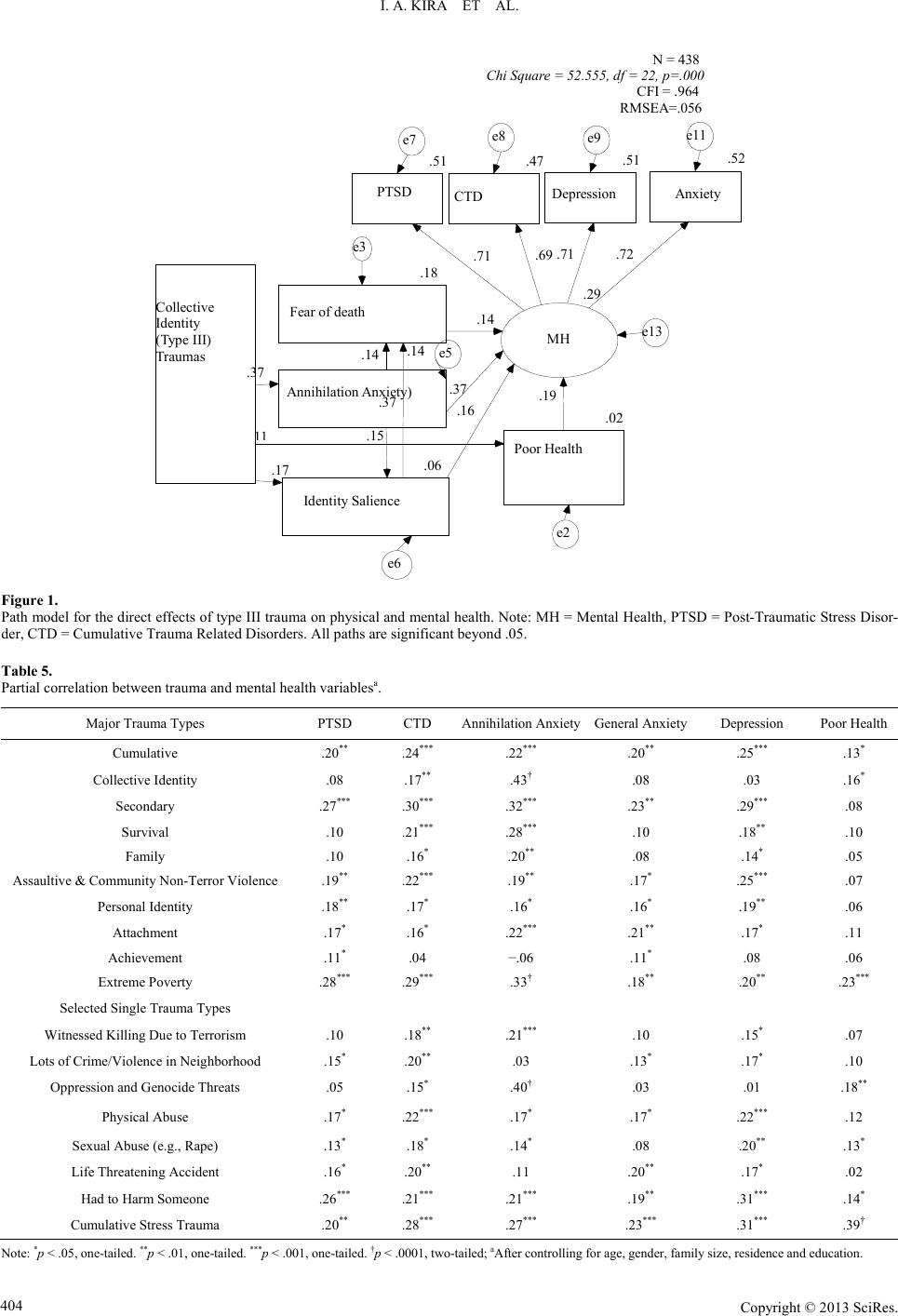

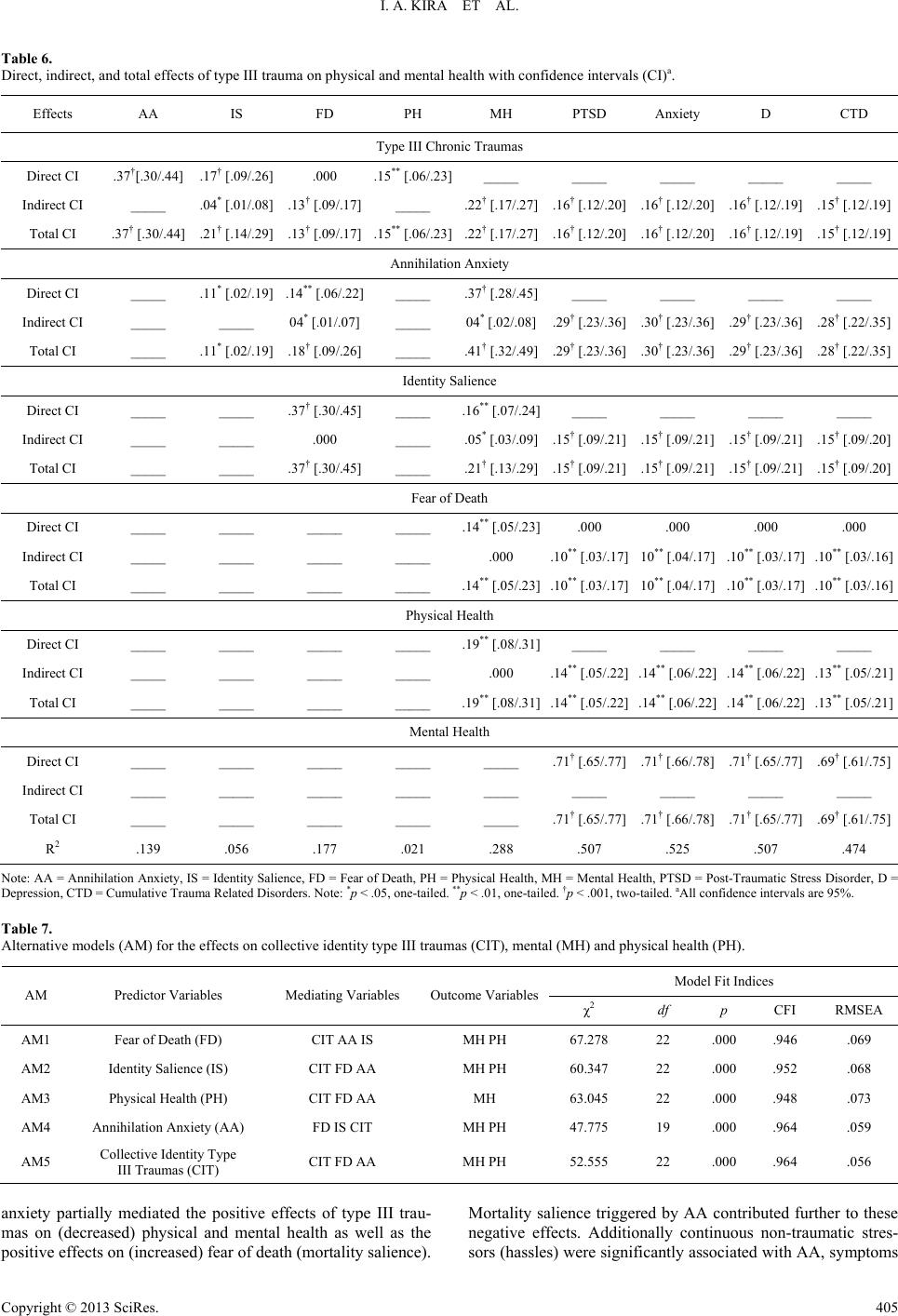

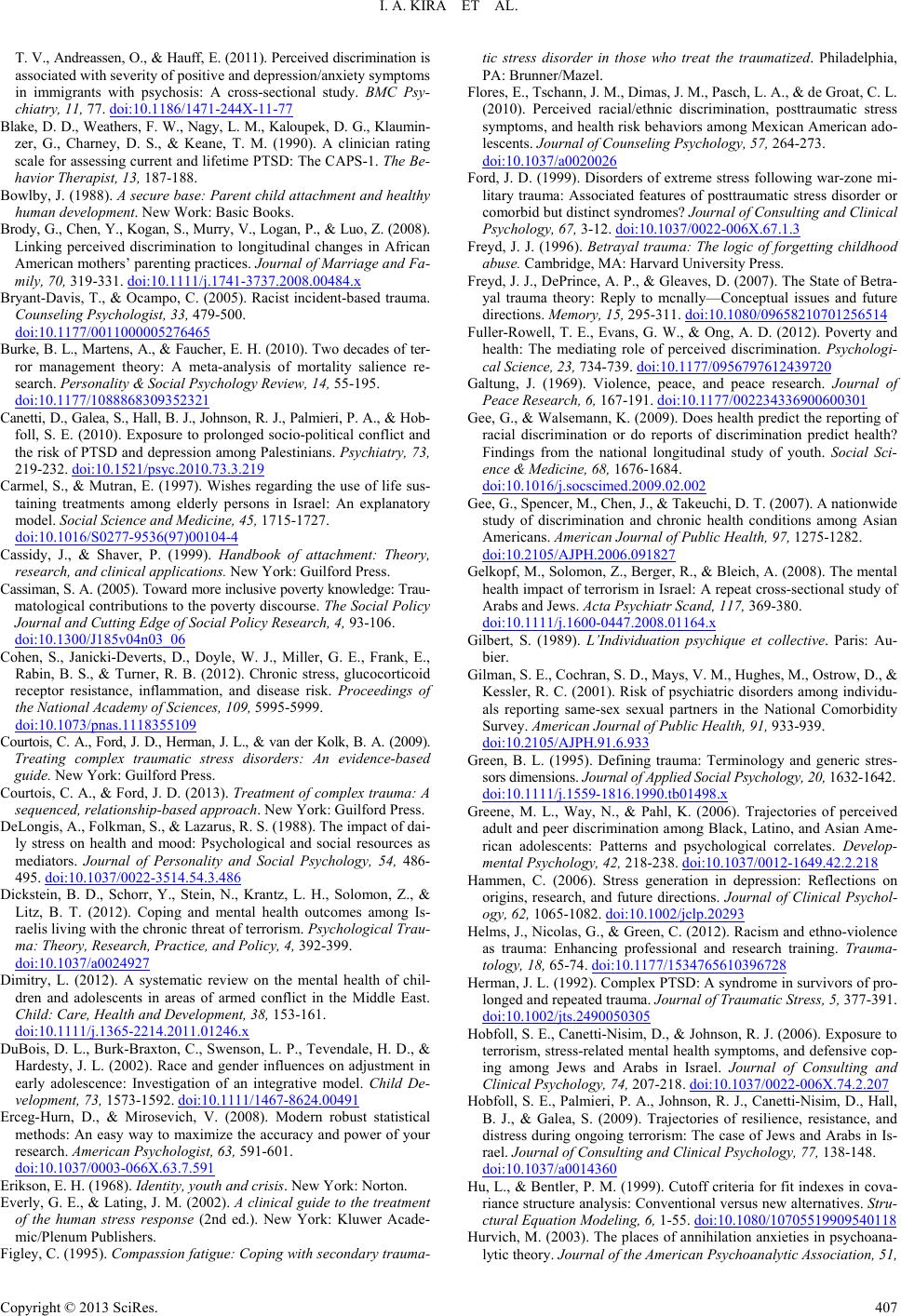

Psychology 2013. Vol.4, No.4, 396-409 Published Online April 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.44057 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 396 Advances in Continuous Traumatic Stress Theory: Traumatogenic Dynamics and Consequences of Intergroup Conflict: The Palestinian Adolescents Case Ibrahim A. Kira1*, Jeffrey S. Ashby2, Linda Lewandowski3, Abdul Wahhab Nasser Alawneh4, Jamal Mohanesh5, Lydia Odenat6 1Center for Cumulative Trauma Studies, Stone Mountain, USA 2Georgia State University, Atlanta, USA 3University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA 4Arab and Middle East Resource Center, Dearborn, USA 5ACCESS Community Health and Research Center, Dearborn, USA 6Emory University, Atlanta, USA Email: *kiraaref@aol.com Received January 21st, 2013; revised February 25th, 2013; accepted March 21st, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ibrahim A. Kira et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The goal of this paper is to advance the theory of chronic and traumatic stressors that have been identified as type III traumas in the trauma developmentally-based framework (DBTF) and use it to investigate the mental and physical health effects of such traumas on impacted individuals and groups. Participants were 438 Palestinian adolescents from the West Bank who had been exposed to a number of types of trauma including chronic intergroup violence. The age of participants in the sample ranged from 12 to 19 with a mean of 15.66 and SD of 1.43. The sample included 54.6% males, 52.3% resided in cities, 44.4% resided in villages, while 3.2% resided in refugee camps. The study utilized a measure for cumulative traumas that is based on the DBTF and measures of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), cumulative trauma re- lated disorders (CTD), depression, anxiety, collective annihilation anxiety (AA), identity salience, and fear of death. The results of partial correlation and path analyses indicated that continuous traumatic stress was a significant predictor of mental health. The analyses also indicated that poverty predicted identity salience and AA that mediated their negative effects on physical and mental health of Palestinian adoles- cents. The relevance of these results to peace, social and clinical psychology was discussed. Keywords: DBTF Trauma Framework; Type III trauma; Stress Generation; Stress Proliferation; Collective Annihilation Anxiety Toward a Theory of Continuous Traumatic Stress Researchers and theorists (e.g., Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995) typically identify three types of stressors: traumatic stress, life events or “ordinary stress”, and chronic stress. Typically the focus of clinical, social and political psychology is more on stressors that have the potential of generating psychological and social pathology and inter-group conflicts rather than the more inconsequential ordinary life stressors. While the literature ge- nerally identifies stressors in these ways, there is a rift in the theory and study of stress. There are two competing but related paradigms including the stress, appraisal, and coping theory that originated initially from the physiological and sociological literature (e.g. Selye, 1956; Lazarus, 1999; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Everly & Lating, 2002) and the theory of traumatic stress that originated mostly from psychiatric, psychological, and psy- cho-political literature (e.g., van der Kolk, Weisaeth, & van der Hart, 1996; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999; Freyd, DePrince, & Glea- ves, 2007; Herman, 1992; Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005). Further, within the theory of traumatic stress there is a divide between three major paradigms in studying traumatic processes: the psychiatric paradigm that focused mostly on the physical survival types of traumatic stress that threaten the “physical integrity”, or risk of serious injury or death, to self or others, and on the resulted post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) sym- ptoms (e.g., Green, 1995; Rothschild, 2000), the psychoanalytic, and developmental paradigms that focused more on studying the effects of abandonment, child maltreatment and other betra- yal traumas in early childhood (e.g., Bowlby, 1988; Cassidy & Shaver, 1999; Freyd, DePrince, & Gleaves, 2007), and the inter- group paradigm as evidenced in studying discrimination, geno- cide, holocaust, torture and other shared politically motivated micro and macro aggressions (e.g., Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Sue, 2010; for analysis of discrimination as a trauma, see Helms, Nicolas, & Green, 2010, for meta-analysis of the effects of discrimination , see Pascoe & Richman, 2009). There are at least three potential problems with the current status of trauma theory and research. The first is its fragmenta- *Corresponding author.  I. A. KIRA ET AL. tion that may allow for the focused study of specific trauma but does not allow for a comprehensive trauma assessment that considers the whole picture of traumatic exposure that the indi- vidual may has endured. Second, current theory and research is more focused on past traumatic events, commonly ignoring the present ongoing and potentially continuous traumatic stressors that may not stop across the lifespan. For example, the psychi- atric paradigm is limited to “physical survival types of trau- matic stress” which focus on a “single trauma type” ignoring the considerable literature addressing the impact of ongoing traumas, as well as systemic traumas, not all of which involve threats to life (although they may involve harm and serious threats to personal or collective identity). Third, current re- search and theory has an individualistic bias that tends to ignore the traumatogenic dynamics of intergroup conflict and of struc- tural, institutional, and ecological traumas. These may include extreme poverty, caste systems, dangerous neighborhoods, hos- tile schools, uprootedness and exclusion from social support networks, disadvantaged social location, and accelerated glob- alization that increase trauma transmission and proliferation, which are key factors in predicting heightened risk for psycho- logical and social pathology. The application of the existing trauma frameworks to contexts of ongoing threat and danger is problematic. Their exclusive focus on past traumas is problem- atic because it tends to obscure the dynamics of the ongoing traumatic events that have unique effects that may modulate, add to, or amplify the effects of past traumas and increase vul- nerability to future traumas. A relatively new, bidimensional, developmentally based stress and trauma framework (DBTF) of stress and trauma attempts to integrate and synthesize the disparate parts of current theory and research. DBTF integrates the factors of chronic stress along with the three main streams of trauma theories in a uni- fied development-based stress and trauma paradigm that in- cludes the previously missing temporal dimensions of chro- nicity and severity by including the impact of ongoing chronic stress and continuous traumatic stressors. DBTF offers a dual lens paradigm through which stress and traumas can be mapped in an individual’s life. DBTF also presents a template to apprise stress and trauma as magnifying or attenuating the effects of exposure to such chronic and traumatic stress (e.g., Kira, 2001, 2004, 2010; Kira et al., 2008a; Kira et al., 2010a, 2010b; Kira et al., 2006; Kira et al., 2012c; Kira, Fawzi, & Fawzi, 2012). The focus of DBTF is on both the individual and group’s traumatization. DBTF defines traumatization as a process that can be triggered by stressors with different levels of intensity that range from chronic hassles to severe traumatic complex stressors, such as the Hiroshima bombing and the holocaust. These identified stressors have the potential to trigger post- trauma spectrum disorders, and/or post-trauma spectrum com- petencies and growth. The synergistic trans-theoretical DBTF offers a wider lens and a defined conceptualization of the trau- matization process and its cumulative dynamics. Based on the general framework of human development and attachment theory (e.g., Bowlby, 1988; Erikson, 1968; Gilbert, 1989), the first dimension of DBTF is development-based and includes attachment traumas, identity traumas that constitute violation of the identities that were developed through the indi- viduation process and emerged in adolescence and adulthood. Identity traumas include four sub-kinds: personal identity trau- mas, collective, social or group identity trauma, and role iden- tity or self-actualization trauma, and physical identity (physical survival) traumas. The source of physical trauma can be either internal, or external. Additionally, interdependence dynamics that are one of the landmarks of adolescent and adult develop- ment may yield socially-made traumas. Socially-made traumas may be perpetuated, directly or indirectly, by institutions, inter- group conflict, and social-structural violence and through glob- alization dynamics. Indirect socially-made traumas can be tran- smitted through secondary and tertiary dynamics (e.g., Figley, 1995; Kira, 2004; Kira, Fawzi, & Fawzi, 2012). Some traumas reverberate continuously horizontally and/or vertically in the fabric of social networks to spread activation of waves of sec- ondary and tertiary trauma and can continue cross-generation- ally. Trauma proliferation theory (Pearlin, Aneshensel, & Leb- lanc, 1997) highlights a class of traumas that spills over to more subsequent traumas. Proliferation refers to the tendency for stressors to beget stressors. For example, job loss can trigger the emergence of a cascade of subsequent serious stressors (e.g., home foreclosure or divorce resulting from job loss). Three important mechanisms of traumatic stress proliferation may be involved. First, chronic stressors and continuous traumatic stress, as well as other non-chronic traumatic stressors, may initiate more subsequent traumas, such as job loss due to discrimina- tion. Second, they may make the individual more vulnerable and susceptible to victimization. This potentially vulnerability is consistent with the stress generation theory. Stress generation theory distinguishes between dependent and independent stres- sors. Independent stressors (stressors out of the individual con- trol, e.g., childhood abuse), tend to generate dependent stressors that the individual controls (e.g., those related to interpersonal relationship, for example. divorce, domestic violence). Stress generation theory proposes that independent life stressors in- crease an individual’s susceptibility to dysfunctional cognitions, attitudes, and behavioral patterns that persist and are, in turn, associated with greater likelihood of subsequent dependent stressors (e.g., domestic violence) (Hammen, 2006; Uliaszek et al., 2012; for a review see Liu, 2013). Integrative models of multiple risk factors that may mediate the relationship between independent and subsequent dependent stressors provide the opportunity for a more comprehensive understanding of stress generation (Liu, 2013). Stress generation theory can be extended to include not only being a victim, but also being a perpetrator which may involve a different set of dependent stressors. For example, committing violence can be dependent on other independent stressors, like be- ing abused as a child, being exposed to killing in combat, or to discrimination and oppression. Perpetrating is a dependent stres- sor that may be a stress generator as well (e.g., McNair, 2002; Hecker et al., 2013). Perpetration-induced trauma is a self- stressor that can generate further stressors related to severe stress- sful consequences, for example, jail, divorce, and social exclu- sion. Even committing violence against self, for example self- cutting, hair bulling, and suicide is a dependent stressor within the causal chain of stress generation that can be a stress gen- erator to self and or others. The third mechanism of traumatic stress proliferation occurs when secondary (indirect) and terti- ary (across individuals and generations) traumas that reverber- ate in the targeted social network and is a third trauma prolifera- tion mechanism (e.g., Kira, 2004; Kira, Fawzi, & Fawzi, 2012). The second dimension in DBTF is more vertical in terms of changing degree or level of chronicity and severity, with sever- ity being dependent on both chronicity and intensity of events. Traumatic events may include, at this level, at least two kinds: Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 397  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 398 single episode (type I) (e.g., car accident) and complex traumas. Complex traumas, in terms of chronicity, include two kinds: type II (repeated similar traumatic episodes that have ceased, for example sexual abuse) (see Terr, 1991), and type III (con- tinuous, repeated and ongoing events, e.g., racism). Examples of continuous chronic personal identity traumas are prostitution and trafficking. Examples of continuous collective identity trau- mas include protracted conflict and related terrorism and other forms of intergroup violence. Another kind of chronic traumatic stressor is social structure-based violence and includes such conditions as extreme poverty and relative deprivation, caste system, and slavery (e.g., Cassiman, 2005; Kira, 2001, 2004; Kira et al., 2008a). Type IV traumas, in this taxonomy, is cu- mulative trauma (CT) across the life time and includes events in the past and ongoing chronic traumas. CT has different cumula- tive dynamics. Table 1 illustrates some of the elements of this model, (see also tables and diagrams published in Kira, 2001; Kira, 2004; Kira et al., 2008a; Kira et al., 2012c, Kira, Fawzi, & Fawzi, 2012e). The etiology of mental health symptoms, social pathology, and intergroup conflict is one of the main focuses of clinical, social, political, and peace psychology. While chronic non- traumatic stressors (e.g., hassles) found to have negative effects on health were the initial focus of stress theory (e.g., DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus; 1988; Lazarus, 2000), traumatology fo- cuses much more on chronic traumatic stress. Type III traumas that are continuous and do not stop, as contrasted to types I and II that occurred but have now stopped, may be considered as having the most serious negative effects on individuals and groups, especially if they have an added intensity. Chronic tra- umatic stress, based on DBTF frame work can include chronic attachment traumas like children separated from parents, chro- nic personal identity trauma like the case in prostitution and human trafficking, chronic collective identity trauma like the case in oppression and discrimination, chronic survival traumas like terrorism and protracted intergroup conflict, and chronic secondary traumas often transmitted through media and other means of secondary continuous exposure. All of the above pro- duce different cumulative trauma profiles that may yield com- plex post-traumatic stress disorder (Ford, 1999; Herman, 1992), continuous traumatic stress syndrome (Straker et al., 1987), and different types of cumulative trauma disorders (Kira, 2001, 2010; Kira et al., 2012b, 2012e) that include different profiles of mental and physical health comorbid disorders. Studying continuous traumatic stress provides one way of researching the psychological impact of living in community conditions where there is a realistic threat of continuous present and future danger, rather than only experiences of past trau- matic dangers and threats. Type III trauma model provides a theoretical basis to study not only past traumas but also differ- ent types of continuous traumatic stress that is still ongoing (e.g., continuous structural violence within group dynamics), as well as other continuous present traumas like chronic extreme poverty, gender or ethnic discrimination and oppression, com- munity violence, human trafficking, prostitution, homelessness, poverty, caste systems, and other ongoing traumas. Such tra- uma types pose endemic limitations on occupational and edu- cational opportunities, and produce marginalization and suf- fering. Structural violence has been recognized as a subtle form of serious complex trauma (Galtung, 1969; Winter & Leighton, 2001). In a type III trauma model structural traumatic violence is triggered by the dynamics of systemic intergroup conflict and related interpersonal macro and micro aggressions. Macro ag- gressions may take a variety of forms including targeted hate crimes, oppression by dominant powerful actors in the form of occupation, insurgency, counter-insurgency, and slavery (pre- sent, past or even those historical or cross-generationally trans- mitted) and reverberate through interdependent structures and networks to produce traumatogenic dynamics for those who Table 1. Taxonomy of severe stressors. Physical Traumas Attachment TraumasIndividuation Traumas Interdependence Traumas Salience Mortality Connection, IntimacyIdentity, Annihilation Group Elimination, Subjugation and Dominance Developmental Task Safety Security Individuation Affiliation and Interdependence (Belonging, Inclusion and Exclusion Dynamics) Internal ExternalChild Adult Personal IdentityCollective Identity Role IdentitySecondary Tertiary+ Systemic Violence Type I Severe Pain Car Accident Parental Neglect Failed Relationships Rape Pearl Harbor Attack Serious Failure (School, Business) Witnessing Murder Multiply Transited - Type II Life Threatening Illness, Reproductive Trauma Combat Parental Neglect Failed Relationships Sexual Abuse, Perpetration- Induced Trauma September 11, 2001, War on Terror Dropping Out of School, Bankruptcy Domestic Violence (Child), Vicarious Trauma (Therapist) - Genocide Type III HIV Protracted Violent Conflict Terrorism Foster Care Failed Relationships Prostitution Human Trafficking Oppression, Racism, Slavery Homelessness Violence Media Exposure Globalization Historical Trauma, Cross-Generation Extreme Poverty, Caste System Type IV Multilateral Continuous Traumatic Stress—Cumulative Traumatic and Non-Traumatic Stress (Chronic Stress) across Life Span*. N ote: *Multilateral traumas are those that involve the overlap of two or more of these basic severe stress elements.  I. A. KIRA ET AL. belong, identify with, or empathize with the targeted groups. Some identity focused type III traumas are may be internal- ized or resisted by some. Internalization of inferiority can cause diminished self-capacity and efficacy and inferiority feelings that may be associated with poor physical, mental and quality of life. Resistance, especially if unsuccessful, can cause sys- temic social conflict or intensify individual distress and social suffering. For example, in discrimination, as a process of chro- nic traumatization, while micro aggressions (e.g., Sue, 2010), demean or exclude the targeted persons, they act as reminders of the overwhelming macro aggressions and the implicit and explicit threats and stereotypes of dominant actors or their rep- resentatives. These reminders may trigger feelings of existential annihilation/subjugation/oppression anxieties, feelings of socie- tal betrayal, stereotype threats that result in decreased self-es- teem, and suppressed self-efficacy. Because such trauma types (collective and personal identity traumas) threaten the core and identity salience of the individual, they can be associated with specific feeling of self-annihilation or subjugation threats and cause annihilation anxiety (e.g., Kira et al., 2012a; Hurvith). This is in contrast to some of the physical identity trauma types that are more associated with harm or death threats and may yield fear of death or death anxiety and trigger mortality Sali- ence (for a review of mortality salience theory, see Burke, Mar- tens, & Faucher, 2010; see also Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszc- zynski, 1991). The links between perceived oppression and discrimination, and poor physical and mental health in adolescents and adults are fairly well established (e.g. Kira et al., 2010a, 2010b; Pas- coe & Richman, 2009; Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2011; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Prospective studies show that perceived discrimination precedes poor psychological and phy- sical health, rather than the other way around (Brody et al., 2008; Gee & Waslemann, 2009). Similar results were found for discrimination against Asian Americans (e.g., Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007), Mexican Americans (e.g., Flores, Tschann, Dimas, Pasch, & de Groat, 2010), immigrants (e.g., Berg et al., 2011), refugees (e.g., Kira et al., 2010a), and female gender (e.g., Kira, Smith, Lewandowski, & Templin, 2010b; Kira et al., 2012d) and for discrimination against sexual minori- ties (e.g., Gilman et al., 2001). Traditionally, Type three traumas have often been underes- timated or ignored and, as a result, have not been identified as extreme traumatic stressors. However, their inclusion may be very important for group, social peace, conflict resolution, and clinical psychology. The lack of inclusion may be explained, in part, by the nature and origins of the traumas. For instance, most of these types of trauma are related to socio-politics, in which the dominant majority or the damaged or inherited social systems, and their governing institutions are the major actors contributing to the continuous traumatic conditions. This makes it difficult to objectively acknowledge their importance and, ei- ther consciously or unconsciously, they may be minimized, dis- couraged or silenced. Living in such traumatic chronic contexts can have deleteri- ous effects on the functioning of biological stress regulatory systems across the life span and, ultimately, on health and psy- chological well-being (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009). Recent research suggests that coping with continuous and cu- mulative stressors elicits a cascade of biological responses that may be functional in the short term but over time they “weather” or damage the systems that regulate the body’s stress response. Allostatic load (AL), a marker of chronic physiologi- cal stress and cumulative wear and tear on the body, illustrates the disease-promoting potential of continuous adjustment to stress (McEwen, 2000; Seeman, McEwen, Rowe, & Singer, 2001; Sterling & Eyer, 1988). Chronic psychological stress has been associated with the body losing its ability to regulate the inflammatory response which promotes the development and progression of disease (Cohen et al., 2012). Elevated continu- ous or prolonged, chronic coping demands sets in motion a cascade of physiological changes that contribute to the devel- opment of chronic illnesses, including hypertension, cardiac di- sease, diabetes, stroke, and psychiatric disorders (Seeman et al., 2001). The effects of type III chronic identity trauma (e.g., dis- crimination) may be particularly detrimental to adolescents. Adolescence is a developmental period characterized by indi- viduation and identity development, as well as cognitive, bio- logical, and social changes. Discrimination stressors signifi- cantly impact youths’ development, psychosocial functioning, and mental and physical health (e.g., Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; DuBois et al., 2002, Williams & Mohammed, 2009). The Israeli Palestinian conflict and its continuous collective identity terror and ongoing exposure to political violence (type III trauma) have exerted a negative toll on Israeli and Palestin- ian adolescents and adults (e.g., Kira, 2006). There is an im- portant and rich literature on the negative mental health effects of terrorism and continuous traumatic stress on Jews and Arabs adolescents and adults in Israel (e.g., Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, & Johnson, 2006; Hopfoll et al., 2009). There is also rich research on the effects of different traumatic stressors on Palestinians adolescents (e.g., Madianos, Sarhan, & Lufti, 2011; Canettti et al., 2010; Al-Krenawi, Graham, & Kanat-Maymon, 2009). De- mitiri (2012), in a meta-analysis of the effects of political vio- lence on Israeli, Palestinian, Lebanese and Iraqi adolescents, found that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents was 5% - 8% in Israel, 23% - 70% in Palestine, and 10% - 30% in Iraq. These results suggest that Palestinian adolescents may be enduring the most severe con- tinuous traumatic stress and distress compared to Israeli, Leba- nese, or Iraqi adolescents. Using a DBTF framework to exam- ine the seemingly disproportionate physical and mental health damage in Palestinian adolescents may offer a much needed perspective. Using the DBTF framework may help explore the effects of such protracted exposure to prolonged political con- flict and other social and/or interpersonal traumas on physical and mental health in Palestinian adolescents, and also examine the utility and validity of the DBTF chronic traumatic stress model. A salient concern that may be precipitated by such chronic traumatic stress exposure is existential annihilation anxiety, which involves apprehension about life and death, as well as personal and collective identity. Most studies have tended to focus on two types of existential concern, i.e., fear of death (or mortality salience) (e.g., Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 1991), and annihilation anxiety related to individual or collec- tive identity (identity salience) (Hurvich, 2003; Kira, 2012a). One of the purposes of this study is to explore whether fear of death and annihilation anxiety mediates the relationship be- tween type III traumas and mental health (e.g., PTSD, Complex PTSD, depression and anxiety) as well as physical health. We expected that fear of death in this community that is caught in continuous intergroup conflict, is more directly related to iden- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 399  I. A. KIRA ET AL. tity salience and related annihilation anxiety and not vice versa. We expected annihilation anxiety to be directly related to type III trauma and related identity concerns more than to fear of death. The Goals of the Current Study The goal of this study was to empirically explore the contri- bution of type III chronic traumas, as compared to the other trauma types, to the negative mental health and physical health of Palestinian adolescents who were exposed to intergroup structural violence among other trauma types. We hypothesized that collective identity threats inherent in type III traumas would predict identity salience, annihilation anxiety, and fear of death (mortality salience), and that these construct would medi- ate the relationship between trauma and mental and physical health. The effects of continuous non-traumatic stress (e.g., hassles), and the effects of contextual conditions that forced some young children and adolescents to commit atrocities ter- rorizing others and traumatizing themselves in the same time, were also of interest in the current research, as they may inten- sify the effects of such continuous traumatic stress. Methods Participants were 438 Palestinian adolescents from the West Bank, age ranged from 12 to 19 with a mean of 15.66 and SD of 1.43%, 54.6% males (N = 239) and 45.4% females (N = 199), 39.9% were attending middle school (N = 175) and 60.1% were attending high school (N = 263). For place of residence, 52.3% resided in cities (N = 229), 44.4% resided in villages (N = 195), while 3.2% resided in refugee camps (N = 14). Ninety nine percent were Muslim Sunni, while 1% were Christians. The mean family size in this sample was 7.99 with SD of 2.69. It also worth mentioning that 20.4% (N = 89) evaluated their school achievement as excellent, 34.9% (N = 153) as very good, 22.5% (N = 99) as good, 15.2% (N = 67) as fair (just pass), and 7% (N = 30) as poor. Measures The measures used in this study as identified in the following section, have previously been shown to have adequate reliabil- ity and validity on Iraqi and Arab populations and in Arabic and English languages (e.g., Kira, Clifford, Wiencek, & Al- haidar, 2001; Kira et al., 2006, 2008a). These measures were originally constructed in English and subsequently translated into Arabic by three bilingual mental health professionals who each individually translated the measures and then met together to establish a consensus on the final version. A fourth mental health professional did the reverse translation. These measures were pilot tested in focus groups. Independen t V ar iables Measures (Cum ulative Trauma Scale) Cumulative trauma scale long version (CTS-L) includes 61 items and is based on the DBTF (Kira, 2001; Kira et al., 2008a, 2008b). Each item describes an extremely stressful event that belongs to one of 6 different types of traumas: attachment, per- sonal identity, collective identity, and secondary, survival, and achievement traumas. Examples are: I was led to sexual contact by one of my caregiver/parents, my mother has abandoned or left/or separated from me when I was a child. On each item, the participant is asked to report if he/she has had this experience or not, how many times the event was experienced on a 5-point likert scale (0 = never, 4 = many times), the age of first event, and how much the event affected him or her positively or nega- tively on a scale from 1 (extremely positive) to 7 (extremely negative). In the analysis, the appraisal scale was divided into two sub-scales: Positive appraisal (1 - 4) and negative apprais- als (5 - 7). The measure includes two single item measures: one for continuous not-traumatic stress (hassles): “I experienced a nervous breakdown or felt like I was about to have one (e.g., about to lose control) due to seemingly small but recurrent or continuous chronic stresses or hassles”. The other single item measured being forced to commit a harmful act to others (I had to harm some body). CTS-L provides us with general scales for two of the cumulative trauma doses: Occurrence and frequency of happenings, two appraisal sub-scales: negative and positive appraisal. It includes, at this level, four sub-scales for each tra- uma types. The measure has been used previously with differ- ent clinical and community populations of adults and children, and proved to have adequate reliability (Alpha of .80 - .90) and good construct and predictive validity (Kira et al., 2008a, 2008b; Kira et al., 2011a). The reliability of the CTS-L was found adequate in the current study (alpha = .98). For the purpose of the current study, we used the occurrence sub-scales and con- structed additional measure that included 8 items that measured assaultive and community non-terror related violence (8 item scale) to compare its effects with the continuous conflict related violence. The measure had an alpha of .69 in the current data. The reliability of the CTS-L occurrence was found to be good in the current study (alpha = .98). Reliabilities for collective identity, personal identity, survival, family, and secondary, attachment and achievement trauma occurrences were .90, .89, .88, .92, .70, and .68 respectively in the current study. Potential Me diating a nd/or Moderating Variabl e s (Fear of Death, Identity Salience, and Annihilation Anxiety) Fear of death and dying measure (12-item measure): The measure was previously developed and tested in Hebrew and Arabic languages in Israel. Fear of death and dying was meas- ured by 12 items, such as “I am afraid of death” and “The thought of being unable to do things for myself at the end of life troubles me very much” (Carmel & Mutran, 1997). Each item was measured by a five-point scale ranging from 1 = com- pletely disagree to 5 = completely agree. According to the re- sults reported by Carmel and Mutran (1997) and Werner, P. & Carmel, S. (2001), two indices, one for fear of dying and one for fear of death, were found. Both factors had an adequate internal validity: Cronbach’s alpha = .80 for the six items in the fear of death factor and Cronbach’s alpha = .81 for the six items of the fear of dying factor. The final score for each factor is the average of the answers to the relevant items. The higher the score, the greater the participant’s fear of death or/and dying. In our study, we found evidence for the same two factors. Internal consistency reliability (alpha) for the current study was .80. In the current study, we utilized the fear of death sub-scale as indicator of mortality salience. Identity salience scale (Kira et al., 2011b) is 10 items scale that had been developed in two studies with 880 Palestinian adolescents. Identity salience or dormancy refers to the status of Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 400  I. A. KIRA ET AL. one group identity in their nested hierarchy, whether it is cen- tral, or peripheral. It includes questions like: I feel personally threatened by hate crimes committed against me or the mem- bers of my race, religion, culture or ethnic group or against another group of my belonging; Sometimes I wish to die or kill somebody or myself before my ethnic, or religion or nation or any other group of my belonging gets harmed, eliminated or subjugated. The response indicates how much he/she disagrees or agrees on a scale from 1 to 7 (1 indicates absolutely disagree and 7 absolutely agree). Higher scores indicate high identity salience. There are follow up questions about the relative im- portance of each group. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis found support for two sub-scales: identity commitment and identity militancy. Internal consistency reliability (alpha) for the measure was .80 for adolescents (and .81 in another adult Palestinian sample, N = 132), with alphas of .74 for com- mitment and .75 for the militancy sub-scale. Test-retest reli- ability after three weeks was .76. The measure was found to have good predictive validity. Increased personal and collective identity traumas predicted increases in identity salience. In- creased identity salience predicted increase in AA and mortality salience. Annihilation anxiety scale (AA) (Kira et al., 2012a) is based on the assumption that there are at least three main sources of the emergence of annihilation threats: threats to personal iden- tity, threats to collective identity, and threats from severe so- cietal structural inequalities. Three items that represent the three components were used in the study. For example, because of what has happened to me personally or is happening to me personally, I sometimes worry that I just lose my sense of self (I worry that I will cease to exist as an individual person). The answer was structured on 5 point-likert-type (5 indicating strongly agree 4 and 1 indicating strongly disagree). The 3- item scale has been used before in a study of Iraqi refugees in the United States and studies including three samples of Pales- tinian adults and adolescents and has showed good reliability (alpha. ranged between .90 - .95) as well as evidence for con- vergent, discriminant, and predictive validity. Results of a fac- tor analysis of AA and general anxiety suggested that AA is independent factor from general anxiety (Kira et al., 2012a). The internal consistency reliability (alpha) for the measure in this study was .93. Dependent Variable Measures (PTSD, Depression, Anxiety, Cumulativ e Trauma Disorders (CTD), and Physical Health) Clinician-administered PTSD scale (CAPS-2) (Blacke et al., 1990) is widely used to assess PTSD. It is a structured clinical interview that assesses 17 symptoms rated on frequency and se- verity, each on a 5-point scale. CAPS demonstrated high reli- ability with a range from .92 - .99 and showed good convergent and discriminant validity. The measure has four subscales: re- experiencing, avoidance, arousal and emotional numbness, de- tachment or dissociation (Palmieri, Weathers, Difede, & King, 2007). In this study, we used the frequency sub-scale of CAPS- 2 that is widely used in the psychiatric literature. Alphas of the four sub-scales in our sample were adequate (.96, .92, .89 and .85 respectively). Internal consistency reliability for the entire mea- sure in this study was .97. Center for epidemiologic studies depression measure (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977): is a 20 item scale that has been widely used with adults and adolescents. Each item is assessed on a 4-point scale and reflects the frequency that each symptom is experi- enced (0 = none of the time, 3 = all of the time). A cutoff score of ≥16 is commonly used for the CES-D to indicate a need for further assessment of the presence of major depressive disorder (Radloff, 1977). High internal consistency (ranging from .85 to .92) and good convergent and discriminant validity, sensitiv- ity and specificity had been reported (e.g., Mulrow et al., 1995). Alpha for the measure in this study was .91. Depression anxiety stress scales-anxiety (DASS-A): Anxiety sub-scale (14 items): DASS was developed by Lovibond & Lovibond (1995) and includes three sub-scales that measure depression, anxiety, and stress. For the purpose of this study, we used only the 14-item DASS-A sub-scale designed to mea- sure anxiety. The DASS is increasingly used in different clini- cal and research settings. A variety of studies (e.g., Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) have offered support for the convergent and predictive validity and reported internal consistency reliabilities (alphas) of .84 in non-clinical samples and .91 in clinical sam- ples. Alpha for the measure in the present study was .95. Cumulative trauma related disorders measure (CTD) (Kira et al., 2012b). This 15 item measure was developed with five community and clinic samples of African American and Arab adolescents and adults. The CTD is an index measure for co- morbid clustered syndromes that assesses 13 different symp- toms: depression, anxiety, somatization, dissociation, auditory and visual hallucinations, avoidance of being with people, pa- ranoid ideations, concentration and memory deficits, loss of self control, feeling suicidal, and feeling like hurting self. The re- sults of exploratory factor analysis found support for four fac- tors: Executive function deficits/loss of control, suicidality, dis- sociation/psychosis, and depression/anxiety/somatization comor- bidity. Confirmatory factor analysis results offered additional support for the factor structure. The measure appears to have good reliability (ranging from .85 and .98). Test-retest reliabil- ity in a 6 week-interval was .76. Alpha for the measure in the current study was .91. A number of studies (e.g., Kira, Clifford, & Al-Haider, 2003) offered support for the measure’s predic- tive validity. Specifically, Kira et al. (2003) found that different kinds of traumas, and cumulative trauma in general accounted for significant variance as predictors of CTD symptoms. Health problems measure: The measure is a checklist (yes/no) of eight types of health problems (based on DSM IV Axis III codes 024-031) including cardiovascular (e.g., blood pressure, heart problems), neurological (e.g., epilepsy), respiratory, di- gestive, musculoskeletal, endocrine, and metabolic diseases that the participant experienced. Higher scores indicate the exis- tence of more health problems of the individual. Internal con- sistency for the measure in the current study was .94. Procedures The study was approved by Palestinian Authority and IRB of the authors’ respective institutions. Participants were recruited through a West Bank School system and included 7 schools. The seven schools were randomly selected from the Jenin area and included schools that included students primarily from refugee camps. Participation was completely voluntary and fully informed. Research participants were told that they may withdraw from the study at any time. Parents were informed that the purpose of the research was to understand the effect of different traumas experienced by children and their physical Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 401  I. A. KIRA ET AL. and mental health. Active informed parental consent and writ- ten adolescents’ ascent were obtained or offered by participat- ing schools and research team members. Some parents ap- proved verbally but chose not to sign due the political situation at the time or for other reasons. No identifying information was recorded that could link the subjects to the data. The disclosure of the data could not reasonably place the subjects at any risk or any liability according to federal and local human subjects’ guidelines. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Arabic by trained Palestinian teachers and local research team members and took between 50 - 90 minutes. The participation was 75% from randomly chosen classes within the seven schools. The field work was conducted from January to March 2005. Analysis To understand the relationships between the variables identi- fied in the study, we initially analyzed the prevalence of trauma types and cumulative trauma load to explore the trauma profile of the sample. We calculated the prevalence of different mental health conditions in the sample to explore the levels of comor- bidity and severity of symptoms. To identify the effects of po- tentially confounding variables, we conducted partial correla- tion between all the variables selected in the study controlling for demographics, family size and residence (city, village, re- fugee camps). Further, we tested a plausible path model, that match the discussed theoretical framework, for direct, indirect effects of type III traumas (continuous traumatic stress) medi- ated by AA, identity salience, and fear of death sub-scale (mor- tality salience), using structural equation model SEM (AMOS 7 software), (Arbuckle, 2006). Model fit indices were selected in accordance with several recommendations and included the normed 2 test statistic (2/df), the root mean square error of ap- proximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). As you will recall, in considering these indices, 2/df values <5.0 are considered acceptable; RMSEA values <.05 indicate close fit, values .05 to .08 indicate reasonable fit, and values >.10 indicate poor fit. CFI values >.95 indicate good fit (e.g., Kline, 2005; Hu & Bentler, 1999). We used bootstrapping procedures with bias-corrected confidence intervals to test the significance of the direct and indirect effects of each variable in the model. Bootstrapping is considered a more robust procedure used to compute p values, test hypotheses, and generate confidence in- tervals for direct and indirect effects (e.g., Erceg-Hurn & Mi- rosevich, 2008). Additionally, we tested several alternative mo- dels, by changing the order of the predictors, mediators, and outcome variables, to find which one of those alternative mod- els had the best fit with data, regardless of our hypotheses. Results Trauma and Mental Heal t h Pr o fi l e s Trauma profile: Participants in the study appeared to be highly traumatized and their appraisal of the effects of traumas was largely negative. Collective identity trauma type III con- tinuous (chronic) traumatic stress (e.g., oppression, occupation and group conflict related violence) had the highest prevalence in their trauma profiles, followed by secondary traumas that are more related to indirect exposure to such events. Survival trau- mas that include terror and non-terror group conflict related violence were equally high. Family related and personal iden- tity traumas, as well assaultive and community (non-terror) vio- lence, attachment, achievement traumas were less prominent in the particiants’ trauma profile. When we analyzed specifics in their trauma profile, witnessing killing due to terrorism, par- ents and children participation in wars related to such conflict, extreme poverty, oppression and genocide threat had the high- est prevalence in the sample. Tables 2-4 describe the details of the group’s trauma profile. Table 2. Prevalence of major and selected single trauma types with CTS-L sub- scale scores. Trauma Type M SD Prevalence (%) Major Trauma Types Collective Identity 2.40 2.27 84.9 Secondary 3.16 4.93 61.9 Survival 3.79 6.12 60.5 Family .88 1.66 40.0 Assaultive & Community Non-Terror Violence .56 1.13 27.3 Personal Identity .82 2.45 22.4 Attachment .33 1.30 11.6 Achievement .02 .14 1.8 Selected Single Trauma Types Witnessed Killing Due to Terrorism .45 .50 45.0 Parents Participated in a War .23 .42 23.0 Extreme Poverty 2.23 1.27 19.8 Natural Disaster .21 .45 19.4 Participated in a War or Combat .19 .40 18.5 Oppression and Genocide Threats 2.04 1.48 18.0 Sudden Death of Parents or Close Relatives .16 .37 16.4 Physical Abuse .13 .34 13.0 Torture of a Parent .11 .32 10.3 Had to Harm Someone .09 .29 9.1 Life Threatening Accident .09 .29 8.9 Cumulative Stress Trauma* .11 .63 6.4 Community Violence .06 .24 6.0 Discriminated Against .05 .21 4.8 Tortured in Jail .03 .19 4.7 Abandonment by mother .03 .18 3.2 Incest .03 .16 2.5 Domestic Violence .02 .16 1.6 Life Threatening Illness .02 .13 1.6 Sexual Abuse (e.g., Rape) .01 .11 1.1 Note: *Had/would have a nervous breakdown due to frequent seemingly insig- nificant hassles. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 402  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Table 3. Frequency of multiple traumas. Number of Trauma Types Reported Prevalence (%) No Trauma 15.1 Single Trauma 9.6 2 - 5 Traumas 26.5 6 or More Traumas 48.8 Total Mean = 7.88 SD = 11.89 100.0 Table 4. Positive and negative appraisals. Appraisal Mean SD Prevalence (%) Positive .46 1.57 16.2 Negative 2.64 5.88 36.1 Mental health profile: In the measurement of depression, the means core on the CESD was 20.29 (SD = 12.92) and 55.6% of the participants scored 16 or higher on the CES-D scale (note that 16 is the cut-off point for clinical depression recommended for this scale). For DASS-A (anxiety) (Mean = 8.32, SD = 7.25) 33% of the sample scored 10 or higher (10 is the recommended cut-off score for moderate to severe anxiety on this scale). For PTSD (Mean = 27.94, SD = 20.49) 50.4% of the participants scored in the elevated level of the scale (26 and above). For annihilation anxiety (Mean = 7.21, SD = 3.11), 33.3% of par- ticipants scored in the high side of scale (9 and above). For CTD (Mean = 40.66, SD = 12.34), 53.1% reported that they were depressed. 59.7% reported anxiety, 32.1% reported that they feel sick most of the time, 26.5% reported that they feel that they are almost two different people (different levels of dis- sociation), 29.8% reported that they sometime hear voices or see things others do not hear or see, 35.4% reported that they try to avoid people and stay by themselves, 32.3% reported that they believe that they have enemies that follow them wherever they go, 42.7% believe that they have decreased memory and concentration, 41.5% feel they do not have enough control of their reactions, 32.7% felt or thought like killing themselves, 18.4% felt like hurting or injuring themselves, 11.5% reported feeling like taking or took drugs, 37.9% reported that they are not functioning in one or more areas in their life, and 39.6% feltl apathetic with no emotions. Partial correlations: Results of the partial correlation analy- ses indicated that poverty and secondary traumas had the high- est associations with PTSD along with the specific stressors of being forced to be the aggressor and harm another. Poverty and Secondary traumas had the highest associations with CTD. Col- lective identity trauma (e.g. oppression and genocide threat), secondary traumas, and poverty, followed by survival and cu- mulative stress traumas, had the highest associations with AA. Secondary traumas, assaultive and community violence, being forced to be the aggressor and harm others, and cumulative stress had the highest associations with depression. Chronic (non-traumatic) stress and poverty had the highest associations with poor health. It is worth noting that significant correlations were mostly moderate with a few strong robust strength rela- tionships (e.g., the relationship between collective identity tra- uma, extreme poverty and annihilation anxiety). Table 5 inclu- des the associations for all of the variables. Path Analysis Results of the path analysis indicated that the model that best represented the theoretical framework of the effects of con- tinuous traumatic stress (type III traumas) had acceptable fit (Chi square = 52.555, df = 22, CFI = .964, RMSEA = .056). In this model, mental health was a latent variable with all four mental health variables (PTSD, CTD, Depression and anxiety) observed predicting variables. All observed mental health vari- ables significantly predicted the latent variables. In this model, type III traumas (collective identity related continuous trau- matic stress) had significant direct effects on annihilation anxi- ety (AA), identity salience, and poor physical health. Type III traumas also had significant indirect effects on mental health (and all its variables in the model: PTSD, CTD, depression and general anxiety) as well as on mortality salience (fear of death sub-scale). AA and identity salience mediated most of these indirect effects. AA had a significant direct effect on mental health, as well as identity salience and mortality salience (fear of death sub-scale). AA also had significant indirect effects on all of the mental health variables. Identity salience had a sig- nificant direct effect on mortality salience (fear of death) and mental health, and significant indirect effects on all mental health variables. Mortality salience (fear of death) had a sig- nificant direct effect on mental health (latent) and an indirect effect on all observed mental health variables. Physical health had significant direct effect on mental health (latent) and a sig- nificant indirect effect on all observed mental health variables. Table 6 describes the direct, indirect and total effects and their confidence intervals for each independent variable in the model. Figure 1 maps the path model that illustrates the direct rela- tionships of the independent variables. Alternative Models (AM) To test different alternative models, we replaced predictors in each model. In the first alternative model we put fear of death as predictor, the fit was relatively poor. In the second alterna- tive model, we changed the predictor to identity salience. While the fit for this model improved, RMSEA was relatively high. In the third model, we put physical health as the predictor. The resulting model fit was poor. In the fourth model, we put anni- hilation anxiety as the predictor; the model had an acceptable fit. In the fifth model (the chosen model that fit the discussed theo- retical framework), we put collective identity type III trauma as predictor, the model had relatively the best fit. Table 7 presents each model predictor variable, mediating and outcome variables and their fit indices. Discussion and Conclusion Consistent with the hypotheses of this study, the results of analyses indicated that continuous traumatic stressors (type III traumas) related to collective identity was the strongest con- tributing factor predicting the severity of physical and mental health symptoms in this sample of Palestinians adolescents. These specific types of continuous trauma may be understood as priming collective identity salience and collective annihila- tion/subjugation anxieties (AA). In this study, annihilation Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 403  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 404 .02 Poor Health .14 Annihilation Anxiety) e5 .29 MH .51 PTSD e7 .47 CTD e8 .51 Depression e9 .52 Anxiety e11 e2 e13 = 438 Chi Square = 52.555, df = 22, p=.000 CFI = .964 RMSEA=.056 Collective Identity (Type III) Traumas .06 Identity Salience e6 .18 Fear of death e3 .37 .14 .19 .16 .37 .17 .72 .69 .71 .71 .15 .37 .14 Figure 1. Path model for the direct effects of type III trauma on physical and mental health. Note: MH = Mental Health, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disor- der, CTD = Cumulative Trauma Related Disorders. All paths are significant beyond .05. Table 5. Partial correlation between trauma and mental health variablesa. Major Trauma Types PTSD CTD Annihilation AnxietyGeneral Anxiety Depression Poor Health Cumulative .20** .24*** .22*** .20** .25*** .13* Collective Identity .08 .17** .43† .08 .03 .16* Secondary .27*** .30*** .32*** .23** .29*** .08 Survival .10 .21*** .28*** .10 .18** .10 Family .10 .16* .20** .08 .14* .05 Assaultive & Community Non-Terror Violence .19** .22*** .19** .17* .25*** .07 Personal Identity .18** .17* .16* .16* .19** .06 Attachment .17* .16* .22*** .21** .17* .11 Achievement .11* .04 −.06 .11* .08 .06 Extreme Poverty .28*** .29*** .33† .18** .20** .23*** Selected Single Trauma Types Witnessed Killing Due to Terrorism .10 .18** .21*** .10 .15* .07 Lots of Crime/Violence in Neighborhood .15* .20** .03 .13* .17* .10 Oppression and Genocide Threats .05 .15* .40† .03 .01 .18** Physical Abuse .17* .22*** .17* .17* .22*** .12 Sexual Abuse (e.g., Rape) .13* .18* .14* .08 .20** .13* Life Threatening Accident .16* .20** .11 .20** .17* .02 Had to Harm Someone .26*** .21*** .21*** .19** .31*** .14* Cumulative Stress Trauma .20** .28*** .27*** .23*** .31*** .39† N ote: *p < .05, one-tailed. **p < .01, one-tailed. ***p < .001, one-tailed. †p < .0001, two-tailed; aAfter controlling for age, gender, family size, residence and education.  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Table 6. Direct, indirect, and total effects of type III trauma on physical and mental health with confidence intervals (CI)a. Effects AA IS FD PH MH PTSD Anxiety D CTD Type III Chronic Traumas Direct CI .37†[.30/.44] .17† [.09/.26] .000 .15** [.06/.23]_____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Indirect CI _____ .04* [.01/.08] .13† [.09/.17]_____ .22† [.17/.27].16† [.12/.20].16† [.12/.20] .16† [.12/.19] .15† [.12/.19] Total CI .37† [.30/.44] .21† [.14/.29] .13† [.09/.17].15** [.06/.23].22† [.17/.27].16† [.12/.20].16† [.12/.20] .16† [.12/.19] .15† [.12/.19] Annihilation Anxiety Direct CI _____ .11* [.02/.19] .14** [.06/.22]_____ .37† [.28/.45]_____ _____ _____ _____ Indirect CI _____ _____ 04* [.01/.07]_____ 04* [.02/.08].29† [.23/.36].30† [.23/.36] .29† [.23/.36] .28† [.22/.35] Total CI _____ .11* [.02/.19] .18† [.09/.26]_____ .41† [.32/.49].29† [.23/.36].30† [.23/.36] .29† [.23/.36] .28† [.22/.35] Identity Salience Direct CI _____ _____ .37† [.30/.45]_____ .16** [.07/.24]_____ _____ _____ _____ Indirect CI _____ _____ .000 _____ .05* [.03/.09].15† [.09/.21].15† [.09/.21] .15† [.09/.21] .15† [.09/.20] Total CI _____ _____ .37† [.30/.45]_____ .21† [.13/.29].15† [.09/.21].15† [.09/.21] .15† [.09/.21] .15† [.09/.20] Fear of Death Direct CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .14** [.05/.23].000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .000 .10** [.03/.17]10** [.04/.17] .10** [.03/.17] .10** [.03/.16] Total CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .14** [.05/.23].10** [.03/.17]10** [.04/.17] .10** [.03/.17] .10** [.03/.16] Physical Health Direct CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .19** [.08/.31]_____ _____ _____ _____ Indirect CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .000 .14** [.05/.22].14** [.06/.22] .14** [.06/.22] .13** [.05/.21] Total CI _____ _____ _____ _____ .19** [.08/.31].14** [.05/.22].14** [.06/.22] .14** [.06/.22] .13** [.05/.21] Mental Health Direct CI _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ .71† [.65/.77].71† [.66/.78] .71† [.65/.77] .69† [.61/.75] Indirect CI _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Total CI _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ .71† [.65/.77].71† [.66/.78] .71† [.65/.77] .69† [.61/.75] R2 .139 .056 .177 .021 .288 .507 .525 .507 .474 Note: AA = Annihilation Anxiety, IS = Identity Salience, FD = Fear of Death, PH = Physical Health, MH = Mental Health, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, D = Depression, CTD = Cumulative Trauma Related Disorders. Note: *p < .05, one-tailed. **p < .01, one-tailed. †p < .001, two-tailed. aAll confidence intervals are 95%. Table 7. Alternative models (AM) for the effects on collective identity type III traumas (CIT), mental (MH) and physical health (PH). Model Fit Indices AM Predictor Variables Mediating Variables Outcome Variables χ2 df p CFI RMSEA AM1 Fear of Death (FD) CIT AA IS MH PH 67.278 22 .000 .946 .069 AM2 Identity Salience (IS) CIT FD AA MH PH 60.347 22 .000 .952 .068 AM3 Physical Health (PH) CIT FD AA MH 63.045 22 .000 .948 .073 AM4 Annihilation Anxiety (AA) FD IS CIT MH PH 47.775 19 .000 .964 .059 AM5 Collective Identity Type III Traumas (CIT) CIT FD AA MH PH 52.555 22 .000 .964 .056 anxiety partially mediated the positive effects of type III trau- mas on (decreased) physical and mental health as well as the positive effects on (increased) fear of death (mortality salience). Mortality salience triggered by AA contributed further to these negative effects. Additionally continuous non-traumatic stres- sors (hassles) were significantly associated with AA, symptoms Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 405  I. A. KIRA ET AL. of depression, general anxiety, PTSD, CTD and poor physical health. Another important finding of this study was that being forced, contextually, to be an aggressor (e.g., committing terror act) and harming others was significantly associated with AA, sym- ptoms of PTSD, CTD, depression, and general anxiety for the potential aggressor. The contextual conditions that forced some to commit atrocities terrorizing others and traumatizing them- selves, in the same time, appeared to have serious negative effects, not only to the victims, but also to those who commit- ted such acts. These results highlight the importance of an ex- tension of stress generation theory to include perpetration as a dependent stressor in the stress generation causal chain. Continuous collective identity and secondary traumas, re- lated to the Israeli Palestinian conflict, seem to be more of a contributing factor to negative physical and mental health con- ditions compared to other trauma types (e.g., personal identity and attachment traumas). The experience of these traumas are were most strongly related to the highest PTSD and other syn- dromes found in this population, compared to other severely traumatized populations (e.g., Israelis & Iraqis; Dimitry, 2012). The fact that Palestinians are a minority group who have suf- fered occupation and subjugation for an extended period of time may be an important factor for their health and well-being. Gelkopf, Solomon, Berger, and Bleich (2008) found that after 19 months of terrorist attacks Arab Israelis and Jewish Israelis reacted similarly to the situation. However after 44 months, PTSD in the Arab population increased three-fold, and resil- iency almost disappeared. They concluded that specific condi- tions inherent in political conflict may put minorities at risk and only be observable as terrorism-related stressors become chro- nic. Further, a recent study on Palestinian adults found that such collective identity traumas are associated with negative post-traumatic growth (Kira et al., 2013). The results of this study highlight the importance of resolu- tion of the ongoing continuous conflict and achieving peace. Alleviating the annihilation and subjugation anxieties normally associated with the occupation and collective identity threats resulted from specific policies (e.g. collective punishment and loss of national identity), is important to help Palestinian chil- dren. The results of this study support the centrality of collective identity salience related anxieties that may be activated by po- litical conflict and the related ongoing traumatic stress. This noted centrality suggests it is at the core of the etiology of re- lated pathology as well as a key for resolution (cf., Kelman, 2001; Kira, 2002; Kira, 2006; Kira et al., 2011b). The results of this study highlight the primacy of identity salience over mor- tality salience in such dynamics as, in this study, mortality sa- lience was triggered by collective identity salience and related annihilation anxieties and not vice versa. Addressing collective identity concerns in resolution efforts of this conflict and working on positive identity development with Palestinian adolescents might help alleviate such concerns. Kelman, 2001, argues that long-term resolution of this deep- rooted conflict requires changes in the groups’ national identi- ties, such that affirmation of one groups’ identity is no longer predicated on negation of the other’s identity. However, con- flict resolution by peacemaking with mutual accommodations and cultural changes on both sides while acknowledging simi- larities and differences in their basic identity structures, and assumptive stereotypes does seem possible. Further, the results of this study highlighted the severe nega- tive effects of poverty as a continuous social structural danger to physical and mental health. Fuller-Rowell, Evans, & Ong (2012), in a longitudinal study, found that 13% of the effect of poverty on allostatic load is explained by perceived discrimina- tion due to poverty. They suggest that social-class discrimina- tion is one important mechanism behind the influence of pov- erty on physical health. The importance of alleviating poverty through economic and social development may be one of the important keys to improving the overall health and mental health of Palestinian children. Recent research by Dickstein et al. (2012) on coping strate- gies with continuous traumatic stress (e.g., terrorism) of Israelis found that substance use coping, denial/disengagement and so- cial support seeking strategies were all associated with psy- chiatric symptoms, and the only coping strategy found to be protective strategy was acceptance and positive reframing (see also Nuttman-Shwartz & Dekel, 2009). Positive reappraisal, being optimistic, and possessing a futuristic orientation have been significantly negatively correlated with AA and depres- sion (e.g., Kira et al., 2011a). Chronic stress and continuous traumatic stress is a serious complex trauma. Newer advance- ments in complex trauma treatment (e.g. Courtois, Ford, Her- man, & van der Kolk, 2009; Courtois & Ford, 2013), and mul- ti-systemic, multi-modal, multi-component ecological approa- ches could be utilized for those who exhibit severe post-com- plex trauma symptoms (Kira, 2010). Additionally, while DBTF integrative trauma framework is theoretically plausible and may have greater heuristic and ex- planatory power than other trauma frameworks, the results provide further evidence of its utility and empirical validity. The goal of the paper was to advance the theory of chronic tra- umatic stress and test one of its basic assumptions that type III traumas are the most severe type for those who are subjected to it. The inclusion of continuous traumatic stress, as the most se- vere type of trauma, is an important contribution. Future research is needed to replicate such results on victims of different types of continuous traumatic stress that may in- volve different or similar dynamics. Limitation of th e S tudy The current paper investigates empirically the relationship between several variables using a cross-sectional, correlational approach. The research points to only relationships and predic- tions. Cross-sectional studies can draw only probabilistic con- clusions from the results. Unobserved confounding variables can distort statistical inference. Further, using snowballing sam- pling in the study limits the generalizability of the results. Fu- ture studies that use longitudinal or controlled approaches and larger representative samples are needed. Nevertheless, the findings provide evidence of the association between continu- ous traumatic stress and the severity of physical and mental health symptoms in Palestinians adolescents. REFERENCES Al-Krenawi, A., Graham, J., & Kanat-Maymon, Y. (2009). Analysis of trauma exposure, symptomatology and functioning in Jewish Israeli and Palestinian adolescents. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195, 427- 432. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050393 Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). A mos 7.0 User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS. Berg, A. O., Melle, I., Rossberg, J., Romm, K., Larsson, S., Lagerberg, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 406  I. A. KIRA ET AL. T. V., Andreassen, O., & Hauff, E. (2011). Perceived discrimination is associated with severity of positive and depression/anxiety symptoms in immigrants with psychosis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psy- chiatry, 11, 77. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-77 Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Klaumin- zer, G., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1990). A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. The Be- havior Therapist, 13, 187-188. Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent child attachment and healthy human development. New Work: Basic Books. Brody, G., Chen, Y., Kogan, S., Murry, V., Logan, P., & Luo, Z. (2008). Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and Fa- mily, 70, 319-331. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00484.x Bryant-Davis, T., & Ocampo, C. (2005). Racist incident-based trauma. Counseling Psychologist, 33, 479-500. doi:10.1177/0011000005276465 Burke, B. L., Martens, A., & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of ter- ror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience re- search. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 14, 55-195. doi:10.1177/1088868309352321 Canetti, D., Galea, S., Hall, B. J., Johnson, R. J., Palmieri, P. A., & Hob- foll, S. E. (2010). Exposure to prolonged socio-political conflict and the risk of PTSD and depression among Palestinians. Psychiatry, 73, 219-232. doi:10.1521/psyc.2010.73.3.219 Carmel, S., & Mutran, E. (1997). Wishes regarding the use of life sus- taining treatments among elderly persons in Israel: An explanatory model. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 1715-1727. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00104-4 Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. (1999). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical a pp l ic at i ons. New York: Guilford Press. Cassiman, S. A. (2005). Toward more inclusive poverty knowledge: Trau- matological contributions to the poverty discourse. The Social Policy Journal and Cutting Edge of Social Policy Research, 4, 93-106. doi:10.1300/J185v04n03_06 Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Doyle, W. J., Miller, G. E., Frank, E., Rabin, B. S., & Turner, R. B. (2012). Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Scie nc es , 1 09 , 5995-5999. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118355109 Courtois, C. A., Ford, J. D., Herman, J. L., & van der Kolk, B. A. (2009). Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. New York: Guilford Press. Courtois, C. A., & Ford, J. D. (2013). Treatment of complex trauma: A sequenced, relationship-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The impact of dai- ly stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 486- 495. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486 Dickstein, B. D., Schorr, Y., Stein, N., Krantz, L. H., Solomon, Z., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Coping and mental health outcomes among Is- raelis living with the chronic threat of terrorism. Psychological Trau- ma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 392-399. doi:10.1037/a0024927 Dimitry, L. (2012). A systematic review on the mental health of chil- dren and adolescents in areas of armed conflict in the Middle East. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38, 153-161. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01246.x DuBois, D. L., Burk-Braxton, C., Swenson, L. P., Tevendale, H. D., & Hardesty, J. L. (2002). Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of an integrative model. Child De- velopment, 73, 1573-1592. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00491 Erceg-Hurn, D., & Mirosevich, V. (2008). Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American P sy ch ol og is t, 63, 591-601. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591 Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton. Everly, G. E., & Lating, J. M. (2002). A clinical guide to the treatment of the human stress response (2nd ed.). New York: Kluwer Acade- mic/Plenum Publishers. Figley, C. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary trauma- tic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel. Flores, E., Tschann, J. M., Dimas, J. M., Pasch, L. A., & de Groat, C. L. (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American ado- lescents. Journal o f Counseling Psychology, 57, 264-273. doi:10.1037/a0020026 Ford, J. D. (1999). Disorders of extreme stress following war-zone mi- litary trauma: Associated features of posttraumatic stress disorder or comorbid but distinct syndromes? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 3-12. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.3 Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Freyd, J. J., DePrince, A. P., & Gleaves, D. (2007). The State of Betra- yal trauma theory: Reply to mcnally—Conceptual issues and future directions. Memory, 15, 295-311. doi:10.1080/09658210701256514 Fuller-Rowell, T. E., Evans, G. W., & Ong, A. D. (2012). Poverty and health: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Psychologi- cal Science, 23, 734-739. doi:10.1177/0956797612439720 Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6, 167-191. doi:10.1177/002234336900600301 Gee, G., & Walsemann, K. (2009). Does health predict the reporting of racial discrimination or do reports of discrimination predict health? Findings from the national longitudinal study of youth. Social Sci- ence & Medicine, 68, 1676-1684. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.002 Gee, G., Spencer, M., Chen, J., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2007). A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. American Jou rnal of Public Health, 97, 1275-1282. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827 Gelkopf, M., Solomon, Z., Berger, R., & Bleich, A. (2008). The mental health impact of terrorism in Israel: A repeat cross-sectional study of Arabs and Jews. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 117, 369-380. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01164.x Gilbert, S. (1989). L’Individuation psychique et collective. Paris: Au- bier. Gilman, S. E., Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., Hughes, M., Ostrow, D., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Risk of psychiatric disorders among individu- als reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 933-939. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.933 Green, B. L. (1995). Defining trauma: Terminology and generic stres- sors dimensions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20, 1632-1642. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1990.tb01498.x Greene, M. L., Way, N., & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian Ame- rican adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Develop- mental Psychology, 42, 218-238. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychol- ogy, 62, 1065-1082. doi:10.1002/jclp.20293 Helms, J., Nicolas, G., & Green, C. (2012). Racism and ethno-violence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Trauma- tology, 18, 65-74. doi:10.1177/1534765610396728 Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of pro- longed and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 377-391. doi:10.1002/jts.2490050305 Hobfoll, S. E., Canetti-Nisim, D., & Johnson, R. J. (2006). Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and defensive cop- ing among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 7 4, 207-218. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.207 Hobfoll, S. E., Palmieri, P. A., Johnson, R. J., Canetti-Nisim, D., Hall, B. J., & Galea, S. (2009). Trajectories of resilience, resistance, and distress during ongoing terrorism: The case of Jews and Arabs in Is- rael. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 138-148. doi:10.1037/a0014360 Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in cova- riance structure analysis: Conventional versus new alternatives. Stru- ctural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 Hurvich, M. (2003). The places of annihilation anxieties in psychoana- lytic theory. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 407  I. A. KIRA ET AL. 579-616. doi:10.1177/00030651030510020801 Kelman, H. C. (2001). The role of national identity in conflict resolu- tion: Experiences from Israeli-Palestinian problem-solving work- shops. In R. D. Ashmore, L. Jussim, & D. Wilder (Eds.), Social iden- tity, intergroup conflict, and conflict reduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Kira, I. (2001). Taxonomy of trauma and trauma assessment. Trauma- tology, 2, 1-14. Kira, I. (2002). Suicide terror and collective trauma: A collective terror management paradigm. Chicago, IL: American Psychological Asso- ciation Annual Convention. Kira, I. (2004). Secondary trauma in treating refugee survivors of tor- ture and their families. Torture, 14, 38-44. Kira, I. (2006). Collective identity terror in the Israeli-Palestinian con- flict and potential solutions. In J. Kuriansky (Ed.), Terror in the holy land, inside the anguish of Israeli-Palestinian conflict (pp. 125-130). New York: Praeger. Kira, I. (2010). Etiology and treatments of post-cumulative traumatic stress disorders in different cultures. Traumatology: An International Journal, 16, 128-141. doi:10.1177/1534765610365914 Kira, I., Clifford, D., Wiencek, P., & Al-Haidar, A. (2001). Iraqi refu- gees in Southeast Michigan: First report. Dearborn: ACCESS com- munity Health and Research. Kira, I., Clifford, D., & Al-haider (2003). Assessing and treating cu- mulative trauma disorders (CTD) in Iraqi refugees. Toronto: Ameri- can Psychological Association Annual Convention. Kira, I., Templin, T., Lewandowski, L., Clifford, D. Wiencek, E., Ham- mad, A., Al-Haidar, A., & Mohanesh, J. (2006). The effects of tor- ture: Two community studies. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 12, 205-228. doi:10.1207/s15327949pac1203_1 Kira, I., Lewandowsk, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008a). Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of trauma. Trauma- tology, 14, 62-87. doi:10.1177/1534765608319324 Kira, I., Lewandowski, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Chiodo, L., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008b). Measuring Cumulative Trauma dose, types and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of tra- umas: The long version. Boston, MA: American Psychological Asso- ciation 116th Annual Convention. Kira, I., Lewandowsi, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., Mo- hanesh, J. (2010a). The effects of perceived discrimination and backlash on Iraqi refugees’ physical and mental health. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 5, 59-81. doi:10.1080/15564901003622110 Kira, I., Smith, I., Lewandowski, L., & Templin, T. (2010b). The ef- fects of perceived gender discrimination on refugee torture survivors: A cross-cultural Traumatology Perspective. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 16, 299-306. doi:10.1177/1078390310384401 Kira, I., Templin, T., Lewandowski, L., Ramaswamy, V., Bulent, O., Abu-Mediane, S., Mohanesh, J., & Alamia, H. (2011a). Cumulative Tertiary appraisal of traumatic events across cultures: Two studies. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping, 16, 43-66. doi:10.1080/15325024.2010.519288 Kira, I., Alawneh, A. N., Aboumediane, S., Mohanesh, J., Ozkan, B., & Alamia, H. (2011b). Identity salience and its dynamics in Palestini- ans adolescents. Psychology, 2, 781-791. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.28120 Kira, I., Templin, T., Lewandowski, L., Ramaswamy, V., Bulent, O., Mo- hanesh, J., & Abdulkhaleq, H. (2012a). Collective and personal anni- hilation anxiety: Measuring annihilation anxiety AA. Psychology, 3, 90-99. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.31015 Kira, I., Templin, T., Lewandowski, L., Ashby, J. S., Oladele, A., & Ode- nat, L. (2012b). Cumulative trauma disorder scale: Two studies. Psy- chology, 3. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.39099 Kira, I., Lewandowski, L., Somers, C., Yoon, J., & Chiodo, L. (2012c). PTSD, Trauma types, cumulative trauma, and IQ: The Case of Afri- can American and Iraqi refugee adolescents. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Pract i c e , and Policy, 4, 128-139. doi:10.1037/a0022121 Kira, I., Ashby, J., Lewandowski, L., Smith, I., & Odenat, L. (2012d). Gender inequality and its effects in females torture survivors. Psy- chology, 3, 352-363. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.34050 Kira, I., Fawzi, M., & Fawzi, M. (2012e). The dynamics of Cumulative Trauma and Trauma types in adults’ patients with psychiatric disor- ders: Two cross-cultural studies. Traumatology. Kira, I., Abou-Mediene, S., Ashby, J., Odenat, L., Mohanesh, J. & Ala- mia, H. (2013). The dynamics of post-traumatic growth across diffe- rent trauma types in a Palestinian sample. Journal of Loss and Trau- ma: International Perspectives on S tr es s & Coping, 18, 120-139. doi:10.1080/15325024.2012.679129 Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. Liu, R. T. (2013). Stress generation: Future directions and clinical impli- cations. Clinical Psychology Review. Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety and stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33, 335-342. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer. Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. American Psychologist, 55, 665-673. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.665 Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Madianos, M. G., Sarhan, A. L., Koukia, E. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorders comorbid with major depression in West Bank, Palestine: A general population cross-sectorial study. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 25, 19-31. doi:10.4321/S0213-61632011000100003 McEwen, B. S. (2000). The neurobiology of stress: From serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Research, 886, 172-189. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02950-4 McNair, R. (2002). Perpetration-induced traumatic stress: The psycho- logical consequences of killing. Westport, CT: Praeger. Nuttman-Shwartz, O., & Dekel, R. (2009). Ways of coping and sense of belonging to the college in the face of a persistent security threat. Journal of Traumatic Str e s s, 22, 667-670. Palmieri, P., Weathers, F., Difede, J., & King, D. (2007). Confirmatory factor analysis of the PTSD Checklist and the Clinician-Adminis- tered PTSD Scale in disaster workers exposed to the World Trade Center Ground Zero. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 329-341. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.329 Pascoe, E. A., & Richman, S. L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531-554. doi:10.1037/a0016059 Pearlin, L. I., Aneshensel, C. S., & Leblanc, A. J. (1997). The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: The case of AIDS caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 223-236. doi:10.2307/2955368 Peretz, T., Baider, L., Ever-Hadani, P., & De-Nour, A. (1994). Psycho- logical distress in female cancer patients with Holocaust experience. General Hospital Psychiatry, 16, 413-418. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(94)90117-1 Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Meas- urement, 1, 385-401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 Rothschild, B. (2000). The body remembers: The psychophysiology of trauma and trauma treatment. New York: W. W. Norton & Com- pany. Seeman, T. E., McEwen, B. S., Rowe, J. W., & Singer, B. H. (2001). Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. PNAS: Proceedings of the National Aca- demy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 4770-4775. doi:10.1073/pnas.081072698 Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill. Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease preven- tion. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 2252-2259. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.754 Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1991). A terror man- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 408  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 409 agement theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of esteem and cultural worldviews. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 93-159). San Diego, CA: Aca- demic Press. Sterling, P., & Eyer, J. (1988). Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In S. Fisher, & J. Reason (Eds.), Handbook of life stress, cognition, and he al th (pp. 629-649). Oxford, England: Wiley. Straker, G., & The Sanctuaries Counseling Team (1987). The continu- ous traumatic stress syndrome: The single therapeutic interview. Psy- chology in Society, 8, 46-79. Sue, D. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. Ame- rican Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 10-20. Turner, R. J., Blair, W., & Donald, L. (1995). The epidemiology of so- cial stress. American So ci o logical Review, 60, 104-124. doi:10.2307/2096348 Uliaszek, A. A., Zinbarg, R. E., Mineka, S., Craske, M. G., Griffith, J. W., Sutton, J. M., Epstein, A., et al. (2012). A longitudinal examina- tion of stress generation in depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 4-15. doi:10.1037/a0025835 van der Kolk, B. A., Weisaeth, L., & van der Hart, O. (1996). History of trauma in psychiatry. In B. A. van der Kolk, A. C. McFarlane, & L. Weisaeth (Eds.), Traumatic stress. The effects of overwhelming ex- perience on mind, body, and so c i et y . New York: Guilford Press. Werner, P., & Carmel, S. (2001). Life-sustaining treatment decisions: Health care social workers’ attitudes and their correlates. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 34, 83-97. doi:10.1300/J083v34n04_07 Williams, D., & Mohammed, S. (2009). Discrimination and racial dis- parities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behav- ioral Medicine, 32, 20-47. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 Winter, D. D., & Leighton, D. C. (2001). Structural violence. In D. J. Christie, R. V. Wagner, & D. D. Winter (Eds.), Peace, conflict, and violence: Peace psychology in the 21st century (pp. 99-101). New York: Prentice-Hall.