Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

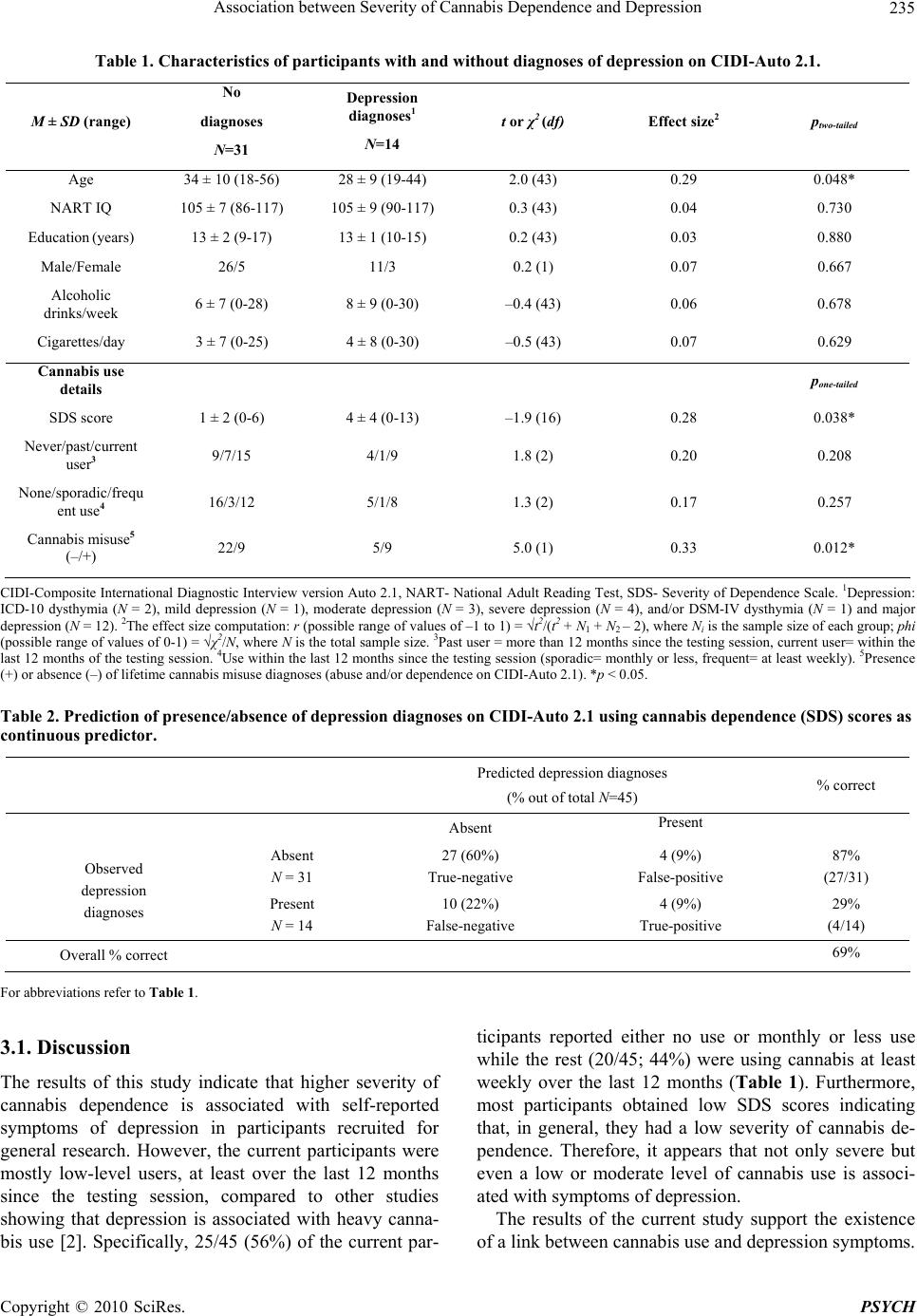

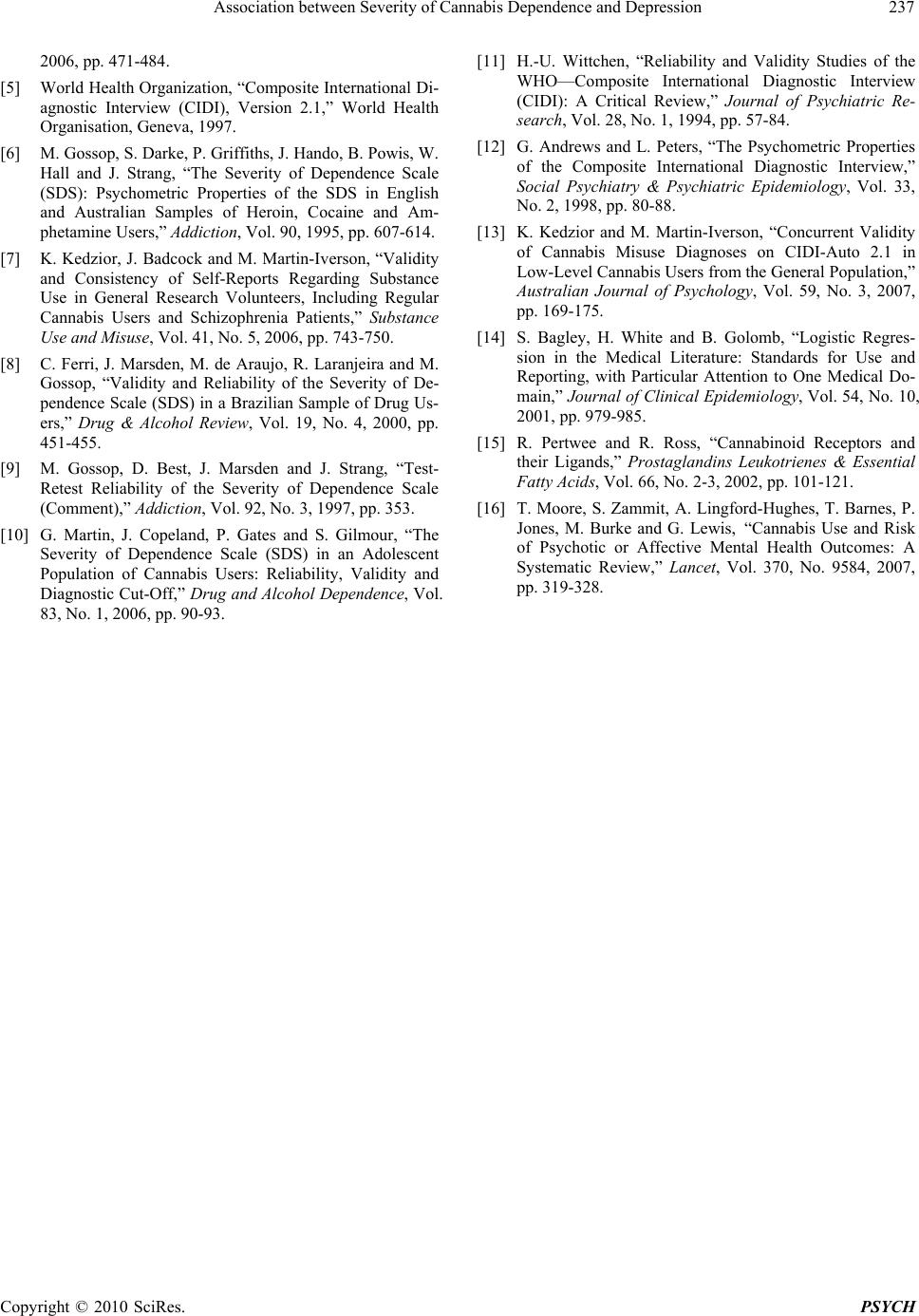

Psychology, 2010, 1, 233-237 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.14031 Published Online October 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 233 Association between Severity of Cannabis Dependence and Depression Karina Karolina Kedzior1,2*, Mathew Martin-Iverson1,2 1,2Clinical Neurophysiology Unit, Graylands Hospital, Mt Claremont, Australia; 1,2Pharmacology & Anaesthesiology Unit, School of Medicine & Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry & Health Sciences, University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia. Email: kkedzior@graduate.uwa.edu.au Received May 19th, 2010; revised June 21st, 2010; accepted August 23rd, 2010. ABSTRACT Objective. The aim of the current study was to investigate the relationship between self-reported severity of cannabis dependence and symptoms of depression. Method. The lifetime diagnoses of depression and cannabis misuse (abuse and/or dependence) were obtained from 50 participants recruited from the general community, using a self-completed diagnostic interview (CIDI-Auto 2.1). The lifetime severity of cannabis dependence was established using a standard questionnaire, Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS). Results. Of the 19 participants with mental illness diagnoses, 14 (74%) reported depression symptoms. The 14 participants with depression diagnoses had significantly more cannabis misuse diagnoses and significantly higher SDS scores compared to those without mental illness diagnoses (N = 31). SDS scores significantly predicted presence or absence of CIDI depression diagnoses with a 69% overall rate of cor- rect predictions. As SDS scores increased the odds of classification into depressed versus non-depressed groups was 1.3 (95% C.I. 1.02-1.57). Conclusion. The presence of lifetime depression symptoms is associated with higher lifetime severity of cannabis dependence and more lifetime cannabis misuse symptoms in otherwise healthy research volunteers. Keywords: Severity of Cannabis Dependence, Depression, CIDI-Auto 2.1, SDS 1. Introduction People with psychotic illnesses have a higher rate of regular cannabis use than those from the general popula- tion [1]. Even though not receiving as much attention, the link between cannabis use and affective disorders, such as depression, also appears to exist [2]. In general, well- designed, large epidemiological studies of the general population in Australia and New Zealand suggest that heavy cannabis use and depression co-occur at levels significantly greater than chance [2]. While the severity of cannabis use is often measured in terms of frequency of use, a more appropriate measure might be dependence on cannabis. Specifically, the con- struct of dependence combines an increased frequency of substance use with psychological and physiological con- sequences of such a use [3]. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investi- gate the association between severity of dependence on cannabis and presence of depression symptoms in volun- teers from the general population recruited for non-treat- ment related research. Based on the epidemiological evi- dence mentioned above, it was hypothesised that partici- pants reporting depression symptoms would also report greater severity of cannabis dependence. Furthermore, it was hypothesised that absence or presence of depression symptoms could be predicted using severity of cannabis dependence. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Participants This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees at the University of Western Australia and the North Metropolitan Mental Health Service in Perth, Australia. Following the informed consent, 50 volunteers participated in the current study included in a larger pro- ject investigating the effects of cannabis use on the startle reflex [4]. The participants were recruited from the gen- eral community of Perth using advertisements at Red Cross blood donation clinics and at a major newspaper (“The West Australian”). The participants were screened for absence of major psychiatric illnesses except for de- pression, neurological disorders, and substance use dis- *Corresponding Author: Dr. Karina Kedzior De Santis, Jacobs Univer- sity Bremen, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Campus Ring 1, 28759 Bremen, Germany.  Association between Severity of Cannabis Dependence and Depression Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 234 orders other than cannabis misuse. Of the 50 participants, 28 reported using cannabis for at least 12 months pre- ceding the testing session. The participants received AU $20 for their participation in the project. 2.2. Procedure All participants self-completed a Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CIDI-Auto 2.1 [5], to establish their lifetime presence of major psychiatric symptoms and/or cannabis misuse symptoms (abuse and/or de- pendence) according to the ICD-10 and/or DSM-IV di- agnostic systems. Of the 50 participants 31 had no psy- chiatric diagnoses (‘No diagnoses’ group) and 19 were assigned psychiatric illness diagnoses. The participants with diagnoses other than depression were excluded (N = 5; ICD-10 and/or DSM-IV delusional disorder N=3 and brief psychotic disorder N = 2) such that the final ‘De- pression diagnoses’ group consisted of 14 participants with diagnoses ranging from dysthymia to severe depres- sion according to DSM-IV and/or ICD-10 (refer to Table 1 for a full list of diagnoses). All participants who had ever used cannabis completed a self-reported questionnaire, Severity of Dependence Scale, SDS [6], to establish their lifetime severity of can- nabis dependence. The SDS is a five-item questionnaire focusing on the psychological aspects of dependence, such as control over cannabis use, anxiety about use, and difficulty stopping [6]. The severity of dependence is established by rating each answer on a scale from 0 to 3. The range of possible scores on this questionnaire is be- tween 0-15 indicating minimum to maximum severity of cannabis dependence respectively. Participants who had never used cannabis were automatically assigned a score of zero indicating lack of cannabis dependence. The self-reports regarding cannabis use were found to be valid and consistent in the current sample of partici- pants [7]. Similarly, both the CIDI-Auto 2.1 and SDS have acceptable psychometric properties. Specifically, high Cronbach’s alphas and intra-class correlation coefficients indicate a good internal consistency and test- retest reli- ability of SDS [6,8-10]. The validity of SDS is shown by correlations between SDS scores and either behavioural patterns of drug taking, such as dose, frequency and dura- tion of use [6,7] or DSM-IV criteria for cannabis depend- ence [8,10]. The test-retest and interrater reliability studies of the CIDI show good to excellent kappa coefficients for most diagnostic sections of the interview [11]. The CIDI also has an acceptable validity [12]. For example, those with cannabis misuse diagnoses (dependence and/or abuse) on CIDI-Auto 2.1 have a significantly higher frequency of use and significantly higher SDS scores than those without such diagnoses [13]. 2.3. Analysis All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 17.0. The various participant characteristics in the ‘No diag- noses’ and ‘Depression diagnoses’ groups were com- pared using independent samples t-tests ( p < 0.05) or chi-square tests ( p < 0.05). A binary logistic regression analysis was used to investigate if severity of cannabis dependence can predict absence or presence of depres- sion diagnoses on CIDI-Auto 2.1 in all 45 participants. The model was computed using one dichotomous de- pendent variable (absence = 0 or presence = 1 of depres- sion diagnoses), one continuous predictor (SDS scores) and a .5 cut-off for classification of participants into ei- ther of the groups. The two assumptions relevant to a one-predictor logistic regression model were met [14]. Specifically, the ratio of cases to predictors was above 10 (45 cases to one predictor) and the model goodness-of-fit comparing the observed with predicted classification of cases was assumed based on a non-significant Hosmer and Lemeshow Test; χ2(4) = 3.3, p = 0.513. 3. Results The results reported in Table 1 show that the ‘No diag- noses’ and ‘Depression diagnoses’ groups were matched on IQ, duration of formal education, male to female pro- portion, and alcohol and nicotine use frequency over the last 12 months since the testing session. However, the participants with no diagnoses were significantly older than those with depression diagnoses (Table 1). The assessment of cannabis use characteristics has shown that compared to the ‘No diagnoses’ group the participants with lifetime CIDI diagnoses of depression had significantly higher severity of cannabis dependence (higher SDS scores) and a significantly higher proportion of these participants had concurrent lifetime CIDI diag- noses of cannabis misuse (abuse and/or dependence ac- cording to ICD10 and/or DMS-IV; Table 1). Furthermore, the binomial logistic regression model was significant (χ2(1) = 5.1, p = 0.024). Specifically, the higher SDS scores were able to significantly predict presence of depression diagnoses (B = 0.2, Wald χ2(1) = 4.4, p = 0.036, odds ratio = 1.3, 95% confidence interval: 1.02-1.57). The odds ratio suggests that, as the predictor (SDS score) increases by one unit, the odds of being classified into the depression diagnoses group are 1.3 compared to the no diagnoses group. The overall rate of correct classification was 69% and SDS was able to bet- ter predict absence (87% correct predictions) than pres- ence of depression diagnoses (29% correct predictions; Table 2). Finally, only little variance in the dependent variable was explained by the predictor according to Cox and Snell’s R = 0.11 and Nagelkerke’s R = 0.15.  Association between Severity of Cannabis Dependence and Depression Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 235 Table 1. Characteristics of participants with and without diagnoses of depression on CIDI-Auto 2.1. M ± SD (range) No diagnoses N=31 Depression diagnoses1 N=14 t or χ2 (df) Effect size2 ptwo-tailed Age 34 ± 10 (18-56) 28 ± 9 (19-44) 2.0 (43) 0.29 0.048* NART IQ 105 ± 7 (86-117) 105 ± 9 (90-117) 0.3 (43) 0.04 0.730 Education (years) 13 ± 2 (9-17) 13 ± 1 (10-15) 0.2 (43) 0.03 0.880 Male/Female 26/5 11/3 0.2 (1) 0.07 0.667 Alcoholic drinks/week 6 ± 7 (0-28) 8 ± 9 (0-30) –0.4 (43) 0.06 0.678 Cigarettes/day 3 ± 7 (0-25) 4 ± 8 (0-30) –0.5 (43) 0.07 0.629 Cannabis use details pone-tailed SDS score 1 ± 2 (0-6) 4 ± 4 (0-13) –1.9 (16) 0.28 0.038* Never/past/current user3 9/7/15 4/1/9 1.8 (2) 0.20 0.208 None/sporadic/frequ ent use4 16/3/12 5/1/8 1.3 (2) 0.17 0.257 Cannabis misuse5 (–/+) 22/9 5/9 5.0 (1) 0.33 0.012* CIDI-Composite International Diagnostic Interview version Auto 2.1, NART- National Adult Reading Test, SDS- Severity of Dependence Scale. 1Depression: ICD-10 dysthymia (N = 2), mild depression (N = 1), moderate depression (N = 3), severe depression (N = 4), and/or DSM-IV dysthymia (N = 1) and major depression (N = 12). 2The effect size computation: r (possible range of values of –1 to 1) = √t2/(t2 + N1 + N2 – 2), where Ni is the sample size of each group; phi (possible range of values of 0-1) = √χ2/N, where N is the total sample size. 3Past user = more than 12 months since the testing session, current user= within the last 12 months of the testing session. 4Use within the last 12 months since the testing session (sporadic= monthly or less, frequent= at least weekly). 5Presence (+) or absence (–) of lifetime cannabis misuse diagnoses (abuse and/or dependence on CIDI-Auto 2.1). *p < 0.05. Table 2. Prediction of presence/absence of depression diagnoses on CIDI-Auto 2. 1 using c a nnabis de pe ndence (SDS) scores as continuous predictor. Predicted depression diagnoses (% out of total N=45) % correct Absent Present Absent N = 31 27 (60%) True-negative 4 (9%) False-positive 87% (27/31) Observed depression diagnoses Present N = 14 10 (22%) False-negative 4 (9%) True-positive 29% (4/14) Overall % correct 69% For abbreviations refer to Table 1. 3.1. Discussion The results of this study indicate that higher severity of cannabis dependence is associated with self-reported symptoms of depression in participants recruited for general research. However, the current participants were mostly low-level users, at least over the last 12 months since the testing session, compared to other studies showing that depression is associated with heavy canna- bis use [2]. Specifically, 25/45 (56%) of the current par- ticipants reported either no use or monthly or less use while the rest (20/45; 44%) were using cannabis at least weekly over the last 12 months (Table 1). Furthermore, most participants obtained low SDS scores indicating that, in general, they had a low severity of cannabis de- pendence. Therefore, it appears that not only severe but even a low or moderate level of cannabis use is associ- ated with symptoms of depression. The results of the current study support the existence of a link between cannabis use and depression symptoms.  Association between Severity of Cannabis Dependence and Depression Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 236 It can only be speculated that, similarly to the relation- ship between cannabis use and psychotic illness, canna- bis could either contribute to development of affective mental illnesses or it could be used as self-medication against existing symptoms of such illnesses. However, the most likely scenario is that the relationship between affective mental illness and cannabis use is due to other common factors, such as a family history of depression, similar age of onset of depression and cannabis use, or common childhood stressors, including abuse, neglect or unhealthy family dynamics. A common neurobiological factor, such as changes in various neurotransmitter sys- tems, including serotonin, noradrenaline, GABA, and acetylcholine or CB1 receptors [15], may also link can- nabis use with depression. The third-factor explanation is supported by the evidence that the regular cannabis use appears to explain only a small proportion of depression in the population unlike the relationship between canna- bis use and psychosis [2,16]. Even though the data in the current study were ob- tained from self-reports these were found to be accurate and consistent in the current participants. Specifically, there was a high agreement between the self-reported cannabis use and urine screens for cannabis over the last 24 h since the testing session [7]. There was also an ac- ceptable consistency between multiple self-reports of past cannabis use [7]. Furthermore, the current partici- pants were also able to consistently report the symptoms of cannabis misuse disorders (abuse and/or dependence) on CIDI-Auto 2.1 [13]. In general, it appears that par- ticipants in behavioural research unrelated to treatment, such as participants in the current study, have very few reasons for providing false reports about their substance use and mental health particularly if they can remain anonymous and are required to attend one testing session only [7]. Therefore, even though it cannot be ruled out, it is likely that the results of the current study were not sys- tematically confounded by invalid and unreliable self- reports. Similarly to other studies [16], the relationship be- tween cannabis use and depression can be considered weak in the current study for a number of reasons. Firstly, the small sample size could have accounted for a low statistical power in the results which were marginally significant and with low-medium effect sizes. Further- more, the high variance in the data might have resulted from the heterogeneity of the sample in terms of the various types of depression diagnoses and the gender of participants. Therefore, a larger, homogenous sample should be used to assess the relationship between canna- bis use and depression in males and females separately. Secondly, the overall rate of correct predictions of de- pression diagnoses using the severity of cannabis de- pendence was low in logistic regression (69%) possibly due to limitations of the two instruments used (SDS and CIDI-Auto 2.1) and the low number of depression diag- noses. Therefore, one way to improve this study would be to utilise clinicians to confirm any psychiatric diag- noses. Thirdly, it is also likely that the relationship be- tween cannabis use and depression is more pronounced in participants using cannabis more frequently than those included in the current study. Therefore, a larger sample of participants using cannabis with low- and high-fre- quencies would help to investigate the role of heaviness of use in the relationship between cannabis use and de- pression. If replicated in larger samples, the finding that even a low-frequency use of cannabis is associated with depression could be useful for cannabis policy develop- ment. Currently most cannabis policies are driven by research showing the link between heavy cannabis use and psychotic mental illness. However, it would also be important to focus on a link between a low-level use and depression because many users have limited access to cannabis and use it irregularly. In conclusion, the severity of cannabis dependence appears to be associated with depression symptoms in low-level cannabis users recruited from the general popu- lation for non-treatment related research. More studies are required to explain the directional meaning of such an association and its neurobiological bases. 4. Acknowledgements This research was funded by The Western Australian Foundation for Research into Schizophrenic Disorders and the NHMRC (grant no. 254619). The authors would like to thank Ms. Andra Raisa Petca (B.A.) and Dr. Mi- lan Dragovic for their assistance with preparation of this manuscript. REFERENCES [1] H. Verdoux, “Cannabis and Psychosis Proneness,” In: D. Castle and R. Murray, Eds., Marijuana and Madness: Psychiatry and Neurobiology, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2004, pp. 75-88. [2] L. Degenhardt, W. Hall, M. Lynskey, C. Coffey and G. Patton, “The Association between Cannabis Use and De- pression: A Review of the Evidence,” In: D. Castle and R. Murray, Eds., Marijuana and Madness: Psychiatry and Neurobiology, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2004, pp. 54-74. [3] American Psychiatric Association, “Diagnostic and Sta- tistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV),” Ameri- can Psychiatric Association, 1994. [4] K. Kedzior and M. Martin-Iverson, “Chronic Cannabis Use is Associated with Attention-Modulated Reduction in Prepulse Inhibition of the Startle Reflex in Healthy Hu- mans,” Journal of Psychopharmacology, Vol. 20, No. 4,  Association between Severity of Cannabis Dependence and Depression Copyright © 2010 SciRes. PSYCH 237 2006, pp. 471-484. [5] World Health Organization, “Composite International Di- agnostic Interview (CIDI), Version 2.1,” World Health Organisation, Geneva, 1997. [6] M. Gossop, S. Darke, P. Griffiths, J. Hando, B. Powis, W. Hall and J. Strang, “The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): Psychometric Properties of the SDS in English and Australian Samples of Heroin, Cocaine and Am- phetamine Users,” Addiction, Vol. 90, 1995, pp. 607-614. [7] K. Kedzior, J. Badcock and M. Martin-Iverson, “Validity and Consistency of Self-Reports Regarding Substance Use in General Research Volunteers, Including Regular Cannabis Users and Schizophrenia Patients,” Substance Use and Misuse, Vol. 41, No. 5, 2006, pp. 743-750. [8] C. Ferri, J. Marsden, M. de Araujo, R. Laranjeira and M. Gossop, “Validity and Reliability of the Severity of De- pendence Scale (SDS) in a Brazilian Sample of Drug Us- ers,” Drug & Alcohol Review, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2000, pp. 451-455. [9] M. Gossop, D. Best, J. Marsden and J. Strang, “Test- Retest Reliability of the Severity of Dependence Scale (Comment),” Addiction, Vol. 92, No. 3, 1997, pp. 353. [10] G. Martin, J. Copeland, P. Gates and S. Gilmour, “The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) in an Adolescent Population of Cannabis Users: Reliability, Validity and Diagnostic Cut-Off,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Vol. 83, No. 1, 2006, pp. 90-93. [11] H.-U. Wittchen, “Reliability and Validity Studies of the WHO—Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A Critical Review,” Journal of Psychiatric Re- search, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1994, pp. 57-84. [12] G. Andrews and L. Peters, “The Psychometric Properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview,” Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, Vol. 33, No. 2, 1998, pp. 80-88. [13] K. Kedzior and M. Martin-Iverson, “Concurrent Validity of Cannabis Misuse Diagnoses on CIDI-Auto 2.1 in Low-Level Cannabis Users from the General Population,” Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol. 59, No. 3, 2007, pp. 169-175. [14] S. Bagley, H. White and B. Golomb, “Logistic Regres- sion in the Medical Literature: Standards for Use and Reporting, with Particular Attention to One Medical Do- main,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, Vol. 54, No. 10, 2001, pp. 979-985. [15] R. Pertwee and R. Ross, “Cannabinoid Receptors and their Ligands,” Prostaglandins Leukotrienes & Essential Fatty Acids, Vol. 66, No. 2-3, 2002, pp. 101-121. [16] T. Moore, S. Zammit, A. Lingford-Hughes, T. Barnes, P. Jones, M. Burke and G. Lewis, “Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychotic or Affective Mental Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Lancet, Vol. 370, No. 9584, 2007, pp. 319-328. |