Open Journal of Gastroenterology, 2013, 3, 55-63 OJGas http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojgas.2013.31009 Published Online February 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojgas/) Irritable bowel syndrome in Chinese nursing and medical school students—Related lifestyle and psychological factors Yukiko Okami1,2*, Gyozen Nin2, Kiyomi Harada3, Sayori Wada3, Tomiko Tsuji1, Yusuke Okuyama4, Susumu Takakuwa5, Motoyori Kanazawa6, Shin Fukudo6, Akane Higashi3 1Department of Health and Nutrition, Nagoya Bunri University, Inazawa, Japan 2Ex-Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Kyoto Prefectural University, Kyoto, Japan 3Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Kyoto Prefectural University, Kyoto, Japan 4Department of Gastroenterology, Japan Red Cro ss Kyoto Daiichi Ho spital, Kyoto , Japan 5Department of Education, K yoto Women’s University, Kyoto, Japan 6Department of Behavioral Medicine, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan Email: *okami.yukiko@nagoya-bunri.ac.jp Received 17 December 2012; revised 19 January 2013; accepted 25 January 2013 ABSTRACT Background: Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is 10% - 15% in the general population. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort and disordered defeca- tion associated with a stressful lifestyle. However, the cause of IBS has not been clarified yet. Based on a similar, previous study in Japan, this study investi- gated the prevalence of IBS and the relationship be- tween IBS and stress, lifestyle and dietary habits among nursing and medical school students in China. Methods: Designed to investigate IBS symptoms, life- style, dietary intake, life events, anxiety and depress- sion, a blank self-administrated questionnaire was used to survey 2500 nursing or medical students in China. Questionnaires were collected from 2141 stu- dents (85.6%) and responses obtained from 1934 stu- dents (90.3%) were analyzed. Results: On the whole, the prevalence of IBS was 32.1% in this study, 26.6% in males and 33.6% in females. In females, the IBS group showed a bedtime later than that in the non-IBS group, and the length of time asleep in the IBS group was shorter than that in the non-IBS group (p < 0.001, p = 0.005). In females, the IBS group showed a frequency for the intake of vegetables and potatoes that was lower than that of the non-IBS group (p = 0.007, p = 0.023). The prevalence of IBS among nursing and medical school students in China (32.1%) was significantly lower than that in Japan (35.5%). Especially, the number of females in the constipation dominant IBS subgroup in China (11.8%) was less than that found in Japan (20.4%). Conclu- sions: The prevalence of IBS was high among nursing and medical students in China, but lower than that shown in Japan. Keywords: China; Irritable Bowel Syndrome; Nursing School; Medical School; Lifestyle; Food Frequency; Dietary Habits 1. INTRODUCTION A functional disorder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is associated with ab- dominal pain or discomfort, with a concurrent distur- bance in bowel habits [1]. The mechanism and cause of IBS remain unknown. However, it has been clarified that most of the reported disorders, for example, dysregula- tion of the nervous system, altered intestinal motility, and increased visceral sensitivity, result from dysregula- tion of the bidirectional communication between the gut with its enteric nervous system and the brain (the brain- gut axis) [2]. The neural network of the brain that gener- ates this stress response is called the central stress cir- cuitry [3], and it receives input from the somatic and visceral afferent pathways and also from the visceral motor cortex. The output of this central stress circuit is known as the emotional motor system, and it includ es the autonomic efferents, such as the hypothalamus-pituitary- adrenal axis and pain modulatory systems [3]. In Western countries, the prevalence of IBS is 15% - 24% in the general population, regardless of age or eth- nicity, with a males/females ratio of 1:1.5 [4,5]. In most Asian countries, the prevalence of IBS is 5% - 10% [6], lower than that found in Western countries. The preva- lence of IBS was found to be 5.7% in Korean college and university students [7], 10.4% in undergraduates in South- *Corresponding a uthor. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 56 east China [8,9], and 7.9% in college and university stu- dents in North China [10]. The incidence rate per year is between 1% and 2% [11,12]. The frequency of young females with defecation problems has been increasing recently. In general, more females have IBS than males [14,15] and the prevalence of females with IBS is 1.5 to 2 times higher than that shown for males in many coun- tries [7,15-17]. Reports have been published on IBS in China since 1990. The prevalence of IBS was reported to be 0.82% in 1996 [18], 5.6% in 2001 [19], and 20.2% in 2006 [20]. In a study conduc ted in Japan between 2006 and 2007 [21], we investigated the prevalence of IBS and the rela- tionship between IBS and stress, lifestyle, and dietary habits in nursing and medical students, who were se- lected as the subjects of the study because they had a more stressful life than students with other majors or the general population due to their demanding schedule with the university curriculum and clinical practice. The re- sults of that study showed that the prevalence of IBS was 35.5% on the whole, 25.2% in males and 41.5% in fe- males. In addition, IBS was related to anxiety and de- pression, dietary habits including less intake of fish, fruit, milk and green-yellow vegetables, and much intake of retort food products, as well as with unhealthy lifestyles, including irregular meals and sleep disturbances [21]. Based on these results, we investigated the prevalence of IBS and the tendency in China, which is located close to Japan. In addition, we also chose nursing and medical students as the subjects of this study in order to compare the results with the Japanese study [21]. The purpose of this study was to clarify the prevalence of IBS and the relationship between IBS and stress, lifestyle and dietary habits in nursing and medical school students in China, and to compare the results obtained from the Chinese subjects with data obtained from our previous Japanese study [21]. Therefore, the hypothesis of this study was sufficiently different from the Japanese study [21]. 2. METHODS In order to compare the results obtained from the Chi- nese subjects with data previously obtained from our Japanese study [21], we used similar subjects and the same questionnaires (in Chinese, rather than Japanese), the same IBS definitions and the same assessment crite- ria as in the Japanese study [21]. From the copyright holder, we obtained permission to show the data in the previously published Japanese study [21] as the refer- ence. 2.1. Study Population Initially, questionnaires were issued to a total of 2500 students for participation in this study, selected from the 3169 university students majoring in nursing or medical technology at Zhengzhou University in Henan Province. A total of 2141 students answered the self-administered questionnaires. According to our eligibility criteria, un- der the age of 30 years old, no diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases, and no data inadequacy, 207 students were considered inelig ible. Therefore, we analyzed ques- tionnaires obtained from a total of 1934 students aged 16- to 24-year-old (19.7 ± 1.4), including 414 (21.4%) males and 1520 (78.6%) females. Study participants were asked to sign an informed consent form before they participated in the study. This study was approved by the Ethical Board of Kyoto Pre- fectural University and Zhengzhou University. This was an observational and cross-sectional study conducted fr om October through November in 2007. 2.2. IBS Definitions Patients with IBS were diagnosed with Rome II criteria [22]. Subjects were classified into three subgroups as follows: The diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), the constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C), and th e alteration type IBS (IBS-A). We used a modified Chinese version of the Rome II modular questionnaire, including 15 items complied by Shinozaki et al. [23]. 2.3. Questionnaire Information (Table 1) In order to obtain a questionnaire suitable for our pur- pose, we combined well-known criteria with some origi- nal items. The questionnaire con tained 67 items, with the Table 1. The questionnaire information items (n). Bowel habits (Rome II criteria) 15 Psychological factors (HADS*) 14 Stressful life events 1 Lifestyle Sleeping Habitation Drinking Smoking Desire to be thin Dieting experience Exercise frequency Exercise items Time spent sitting Use of laxatives 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Dietary habits and food frequency 20 Subjective factor for physical condition 1 Physical characteristics Sex Age Height Weight Hometown 1 1 1 1 1 Treatment of d is e a s e 1 Total 67 *Hospital anxiety and depression scale. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 57 OPEN ACCESS following sections; bowel habits (Rome II criteria) (15 items), psychological factors (Hospital anxiety and de- pression scale: HADS) (14 items), stressful life events (1 item), subjective physical condition factors (1 item), life- style (10 items), dietary habits and food frequency (20 items), physical characteristics (5 items), and treatment for disease (1 item). There were six optional answers in the subjective physical condition factors section; stress, sleep, diet, ir- regular mealtimes, smoking and drinking. 2.4. Psychological Assessments In order to evaluate the stress situation correctly, we as- sessed both the stress response and the stressor. 2.5. Stress Response The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) [24] was employed, a scale proven to be reliable and valid when screening for mood disorders. HADS can be di- vided into a subscale for anxiety (HAD-A) and a sub- scale for depression (HAD-D). In either of the HAD subscales, a score above 10 indicates definite clinically significant anxiety or depression, respectively, up to a maximum score of 21. Respectively, a score of more than 11 points is regarded as a definite type, a score be- tween 8 and 10 is doubtful and a score of less than 7 points indicates no mood disorder. 2.6. Stressor A stressor is a life event considered to be a stressful and subjective event. The subjects were asked whether or not such an event had occurred within the past three months as defined in the IBS definitions and the HADS. They answered “YES” if they thought it was such a life event in their subjective viewpoint, because the form of per- ception is different from person to person. The subjects provided a free description of the content of the life event. Two examples of a life event were provided in the questionnaire, such as the divorce of parents or a roman- tic breakup. 2.7. Exercise Assessment The exercise guideline for health in Japan published in 2006 [25] used “METS” as the unit for the intensity of exercise and “Exercise” as the amount of exercise. “METS” indicates a multiple number of 1 MET, which is the intensity of ex ercise in the resting state. “Exercise” is “METS” multiplied by time. The questionnaire asked about the kind of exercise done and the exercise time period. These items were calculated and “Exercise” was used a s a unit. 2.8. Statistical Analysis Values were expressed as mean ± SD. An an alysis of the proportions among the IBS diagnostic groups was per- formed using Pearson’s chi-square test. Statistical analy- ses for significant differences in parameters were per- formed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test between two groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to measure differences among the three groups. All statisti- cal computations were performed using SPSS (version 11.5 for Windows). A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Prevalence of IBS Out of 1934 students, 110 (26.6%) males and 511 (33.6%) females were diagnosed as having IBS. The predominant type was IBS-A in both males (14.5%) and females (12.5%) (Table 2). The prevalence of IBS and IBS-C in females was higher than that found in males (IBS: p = 0.006, IBS-C: p < 0.001) (Table 2). 3.2. Characteristics of the Subjects by IBS Status In males, there were no statistically significant differ- ences in age, height, weight, BMI or hometown between the IBS and the non-IBS groups (age: p = 0.208, height: p = 0.752, weight: p = 0.944, BMI: p = 0.572, home- town: p = 0.294). In females, age and height were higher in the IBS group than those in the non-IBS group (age: p Table 2. IBS prevalence among nursing and medical school students in China. Males Females Total p* Total 110 (26.6) 511 (33.6) 621 (32.1) 0.006 IBS-D 27 (6.5) 141 (9.3) 168 (8.7) 0.078 IBS-C 23 (5.6) 180 (11.8) 203 (10.5) <0.001 IBS subgroup IBS-A 60 (14.5) 190 (12.5) 250 (12.9) 0.284 Non-IBS subgroup 304 (73.4) 1009 (66.4) 1313 (67.9) To tal 414 (100.0) 1520 (100.0) 1934 (100.0) Data are pres ented as n (% ). IBS ir ritable b owel s yndro me, IBS- D diarrh ea predo minan t IBS, I BS-C con stipat ion pr edominan t IBS , IBS-A alteration type IBS, *Chi-square test (m ales vs. females).  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 58 < 0.001, height: p = 0.021). However, there were no sta- tistically significant differences in weight, BMI or home- town between the IBS-group and the non-IBS group (weight: p = 0.059, BMI: p = 0.697, hometown: p = 0.573). The average weight for males subjects in the IBS-A subgroup was heavier, compared with the other subgroups (p = 0.039). 3.3. The Relationship between Psychological Factors and IBS In females, the anxiety scores were significantly higher in the IBS group, compared with the non-IBS group (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). Females in the IBS-C subgroup had higher anxiety scores than the other subgroups (p = 0.015) and the average scores were over 10 points. Conse- quently, for females, the IBS group showed a more defi- nite anxiety type, compared with the non-IBS group (p < 0.001). Females in the IBS-C subgroup showed a more definite anxiety type than the other subgroups. In both males and females, there were more life events in the IBS group than in the non-IBS group (males: p = 0.015, females: p = 0.013) (Table 3). In males, the IBS-C subgroup had more life events than the other subgroups (p = 0.012). 3.4. Lifestyle In females, the IBS group had more sleep disturbances than the non-IBS group (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). In fe- males, the bedtime of the IBS group was later than shown for the non-IBS group (p < 0.001) (Ta ble 4). In females, the number of sleeping hours in the IBS group was less than that shown in the non-IBS group (p = 0.005). In females, the IBS-C subgroup used more laxa- tives than the other subgrou ps (p = 0.030) (Figure 3). In males, the rate of students using lax atives more than one time a week was 5.4% in the IBS group and 1.9% in the non-IBS group. In f emales, it was 3.5% in the IBS group Figure 1. Anxiety and depression scores on the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in the IBS group and the non-IBS group among nursing and medical school students in China. *p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test. Table 3. Life events in the IBS and the non-IBS groups among nursing and medical school students in China. Males Females IBS Non-IBSp* IBS Non-IBSp* Positive17 (15.7)23 (7.6)0.015 63 (12.3) 84 (8.3)0.013 Negative91 (84.3)278 (92.4) 924 (91.7) 448 (88.7) Total 108 (100.0)301 (100.0) 1008 (100.0) 511 ( 1 00.0) Data are pr esented asn (%). IBS irritable b owel syndrome, *Chi-square test. * Figure 2. Sleep disorder in the IBS group and the non-IBS group among nursing and medical school students in China. *p < 0.001, Chi-square test. and 2.6% in the non-IBS group. In females, the IBS group had more di et experiences than the non-IBS group (p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant dif- ferences shown for either males or females between the IBS group and the non-IBS group in drinking, smoking, exercise and time spent sitting. 3.5. Dietary Habits and Food Frequency of Intake In females, the intake of less leafy vegetables, other vege- tables, and potatoes wa s less in the IBS group, compared with the non-IBS group (p = 0.007, p = 0.023) (Table 5). Females in the IBS-C subgroup ate less beans or bean products, and mushrooms, and drank less milk (p = 0.012, p = 0.006, p = 0.005). Females in the IBS group had more irregular meals and skipped meals more frequently than the non-IBS group (p = 0.002, p = 0.018) (Figures 4 and 5). Especially in males, the rate of missing meals almost everyday was 33.3% in the I B S-D su b- gro u p. 3.6. Subjective Factors Affecting the Body In females, more students in the IBS group thought that the factors affecting their bodies were stress, food, and sleeping time, compared with those in the non-IBS group (p = 0.043, p = 0.032, p = 0.006). More males in the IBS-C subgroup thought the factor affecting their bodies was food, co mp ar ed with th e ot h er su bg rou ps ( p = 0.005). More females in the IBS-C subgroup thought the factor Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 59 Table 4. Sleep time and exercise in the IBS and the non-IBS groups among nursing and medical school students in China. Males (n = 414) Females (n = 1520) IBS Non-IBS p* IBS Non-IBS p* Hours of sleep (h/day) 6.9 ± 0.8 7.0 ± 0.9 0.617 7.0 ± 0.8 7.1 ± 0.9 0.005 Bedtime (time (AM) ± min) 23:43 ± 5523:39 ± 520.254 23:11 ± 5023:01 ± 57 <0.001 Amount of exercis e n (exercise/day) 8.8 ± 7.2 9.4 ± 7.6 0.591 6.6 ± 6.2 6.1 ± 5.7 0.264 Time spent sitting (h/day) 8.2 ± 2.7 8.6 ± 2.5 0.222 8.4 ± 2.2 8.2 ± 2.3 0.139 IBS: irritable bowel syndrome. Data are presented as mean ± SD, *Mann-Whitney U test. Figure 3. Use of laxatives in the IBS group and the non-IBS group among nursing and medical school students. *p = 0.030 (IBS-D, IBS-C vs. IBS-A), Chi-square test. Table 5. Frequency of intake in the IBS and the non-IBS groups among nursing and medical school students in China. Milk Meat Fish Eggs Leafy vegetables Other vegetables and potatoes Everyday 12 (10.9) 33 (30.0) 4 (3.6) 32 (29.1) 68 (61.8) 60 (54.5) 1 - 5 times a week27 (24.5) 52 (47.3) 26 (23.6) 56 (50.9) 38 (34.5) 40 (36.4) IBS Nothing 71 (64.5) 25 (22.7) 80 (72.7) 22 (20.0) 4 (3.6) 10 (9.1) Everyday 39 (13.0) 91 (30.4) 12 (4.0) 105 (35.1) 177 (59.2) 160 (53. 5) 1 - 5 times a week80 (26.8) 139 (46.5) 99 (33.1) 149 (49.8) 104 (34.8) 124 (41.5) Non-IBS Nothing 180 (60.2) 69 (23.1) 188 (62.9) 45 (15.1) 18 (6.0) 15 (5.0) Males * 0.728 0.925 0.163 0.362 0.782 0.234 Everyday 48 (9.5) 38 (7.5) 6 (1.2) 90 (17.8) 208 (41.1) 185 (36.6) 1 - 5 times a week109 (21.5) 182 (35.9) 101 (19.9) 261 (51.5) 251 (49.6) 283 (55.9) IBS Nothing 350 (69.0) 287 (56.6) 400 (78.9) 156 (30.8) 47 (9.3) 38 (7.5) Everyday 95 (9.5) 83 (8.3) 26 (2.6) 192 (19.2) 493 (49.3) 433 (43.3) 1 - 5 times a week228 (22.8) 357 (35.7) 196 (19.6) 507 (50.8) 415 (41.5) 483 (48.3) Non-IBS Nothing 676 (67.7) 559 (56.0) 777 (77.8) 300 (30.0) 91 (9.1) 83 (8.3) Females * 0.821 0.803 0.184 0.773 0.007 0.023 Data are pr esented asn (%). IBS irritable bo wel syndrome, *Chi-square test. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 60 Figure 4. Meal time in the IBS group and the non-IBS group among nursing and medical school students in China. *p = 0.002, Mann-Whitney U test. Figure 5. Skipping meals in the IBS group and the non-IBS group among nursing and medical school students in China. *p = 0.018, Chi-square test. affecting their bodies was stress, compared with the other subgroups (p = 0.025). 3.7. Comparison between Chinese and Japanese (Figure 6) The prevalence of IBS among nursing and medical school students in China (32.1%) was lower than that found in Japan (35.5%) [21] ( p = 0.028). More Japanese females’ subjects had IBS than their Chinese counter- parts (p < 0.001). In females, the prevalence of the IBS-D subgroup was higher in China than that in Japan (p = 0.014), and the prevalence of the IBS-C subgroup in China was lower than that in Japan (p < 0 .001). In males, there were no statistically significant differences between China and Japan in the prevalence of IBS or the sub- groups. 4. DISCUSSION The results of this study showed that the general preva- lence of IBS was 32.1% in nursing and medical school students in China, 26.6% in males and 33.6% in females. Two major findings were revealed in the results. First, the prevalence of IBS was higher than that * ** Preval ence of IBS (% ) Figure 6. Prevalence of IBS (%) between nursing and medical school students in China and those in Japan [21] (printed with permission). *p = 0.014, **p < 0.001, Chi-square test. shown in other Asian studies [6-10]. One of the reasons for this difference was that the subjects were nursing and medical school students, who wor ked irregular hours du e to their studies and clinical practice schedules. Some studies [26,27] have shown that there are a variety of stressors in clinical practice. Jimenez et al. [28] identi- fied three types of stressors (clinical, academic and ex- ternal) and two categories of symptoms (physiological and psychological) linked to clinical practice. The sub- jects of the study perceived clinical stressors more in- tensely than academic or external stressors. In general, most students don’t have any practical experience in the clinical field. Timmins et al. [29] reported that one third of the students in their study felt some degree of stress in their relationships with teachers and staff in the ward, and that the clinical experience and the death of patients were independent sources of stress. Thus, these students might feel more stress than other students or people in general. In support of this hypothesis, other studies that targeted nursing or medical school students also showed a high prevalence of IBS, 35.5% in Japan [21], 15.8% in Malaysia [15], 26.0% in Pakistan [30], and 26.1% in Nigeria [31]. Especially, the prevalence of IBS in nursing and medical school students in Japan [21] and China were both higher than that found in other countries. Prior to recent studies, no large-scale research studies on nurs- ing and medical school students have been conducted. These recent studies have made it clear that nursing and medical school students in the Asian region have a high prevalence of IBS. However, Chang et al. [6] reported that more than 90% of nurses have very limited knowl- edge in regard to IBS, and are unable even to explain it clearly. It is important to expand their knowledge of their own symptoms. Second, the prevalence of IBS in females was higher than that shown in males. This result was consistent with other studies [4-10,21]. The difference between China and Japan was the prevalence of the IBS-C subgroup in females (China: 11.8%, Japan: 20.4%), showing that Ja- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 61 panese females were more constipated than Chinese fe- males. When the food frequency was compared be- tween Chinese females and Japanese females, each food study showed significant differences. Chinese females ate more beans, bean products, and fruit than Japanese females. On the other hand, Japanese Females ate more meat, eggs, milk, dairy products, mushrooms, instant noodles, retort products, confectionery, juice, coffee and tea than Chinese females. These results indicate that the consumption of fiber prevents Chinese females from having constipatio n. However, in addition to dietary hab- its, other elements could also be factors in this difference. For example, the number of females living in a dormi- tory was 1403 (92.4%) in China and 192 (17.3%) in Ja- pan and, the number of females living at a home of their own was 105 (6.9%) in China and 608 (54.6%) in Japan (p < 0.001). The Japanese study [21] showed that students with IBS felt more anxiety than tho se without IBS, which was consistent with the findings of other studies [10,15,21]. Therefore, it can be inferred that anxiety is a predictor of IBS diagnosis, and that psychological factors play an important role in the development of IBS [32-35]. In addition, Drossman [36] reported that psychological fac- tors themselves influence motor abdominal functions, the sensory threshold and the stress reactivity of the intes- tines. The PSLES score, indicating stressful life events, was higher in the IBS group (p < 0.001) in a study con- ducted by Pinto et al. [37]. Furthermore, in that study, both males and females in the IBS group had more life events than the non-IBS group. As mentioned above, more than ninety percent of the subjects of this study were living in a dormitory at the university and they took their meals in the dormitory dining room. Thus, the lifestyles of the subjects were similar. That could be the reason why the results were similar for hometown and habitation between the IBS group and the non-IBS group, despite the fact that life- styles in the urban and rural areas in China are so differ- ent. In the IBS group, females went to bed later, had less sleeping time and more experienced difficulty in falling asleep than the females in the non-IBS group. It is said that peptides synthesized by intestinal bacteria act as a sleeping substance and bowel flora affects non-REM sleep [38]. On the other hand, Burr et al. [39] reported that differences in neuroendocrine levels during sleep were great between the IBS group and the non-IBS group in females. Jarrett et al. [40] also reported that the sym- pathetic/parasympathetic nervous system balance across sequential non-REM periods and REM cycles was mo du- lated differently among the subgroups. The results of these studies inferred that there is an interaction between the sleeping state and abnormal defecation, especially in females. Compared with the non-IBS group, in females, the in- take of leafy vegetables, other vegetables, and potatoes was less in the IBS group. In the Japanese study [21], females in the IBS group also showed a lack of fruit and vegetables. Especially, females in the IBS-C group showed a lack of fruit. These results were consistent with the results shown in this study. Furthermore, both the Japanese study [40] and the Korean study [7] sh owed th e same results for meal times. In females, the IBS group tended to have meals irregularly and to skip meals fre- quently. It is said that skipping meals causes a decrease in the gastro-colonic reflex and restrains defecation [38]. Regardless of the IBS, this study revealed that about 20% of the students skipped meals almost everyday. Re- cently it has been said that young people show a lack in the intake of fruit and vegetables [41,42]. Not only for IBS patients, but also for young students, it is important to regulate their lifestyles, including meal times and the content of meals. More females in the IBS-group chose food as their subjective factors affecting the body, com- pared with those in the non-IBS gro up. This result shows that they recognized their current situation. IBS is asso- ciated with many complicated factors. Sakata et al. [43] reported that the factors affecting IBS differed greatly in individuals. Furthermore, in a study on QOL [44], it was shown that the manner in which people accept situations is different between the races. For example, people in Switzerland considered disease to be more serious than people in Greece did, and it affected their mental health. Treatments are also different, depending on the individ- ual, such as medical therapy, hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and so on. This study was limited in three respects. First, it is dif- ficult to view the results of the study as being valid for the whole country, because this questionnaire was con- ducted in one university. Another limitation was the fact that the students were not living in a general environment, since most of them were living in a dormitory at the uni- versity. Thirds, the number of females was more than three times than that of males, because nursing students are mostly females. We analyzed all data by sex. In conclusion, the prevalence of IBS in nursing and medical school students in China was high, and almost the same as that found in Japan. In females, subjects in the IBS group showed more anxiety than those in the non-IBS group. In both males and females, subjects in the IBS group experienced more life events than those in the non-IBS group. In females, the IBS group had more sleep disturbances, showed more irregular and skipped meals, and intake of leafy vegetables, other vegetables, and potatoes was less than that in the non-IBS group. Because this study was a cross-sectional study, however, the cause and effect relationship was not clarified. Fur- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 62 ther intervention studies are needed to clarify the cause of IB S in th e future. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to express our thanks to the staff at Zhengzhou Univer- sity, including Y. Shi, and all of the students that collaborated in this research. REFERENCES [1] Fujii, Y. and Nomura, S. (2006) The effects of psychoso- cial factors and daily habits of irritable bowel syndrome carriers on the symptoms and disease-specific QOL. Sho- kaki Shinshin Igaku, 13, 14-25. [2] Mach, T. (2004) The brain-gut axis in irritable bowel syndrome-clinical aspects. Medical Science Monitor, 10, RA125-31. [3] Bhatia, V. and Tandon, R.K. (2005) Stress and the gas- trointestinal tract. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepa- tology, 20, 332-339. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03508.x [4] Agréus, L., Svärdsudd, K., Nyrén, O. and Tibblin, G. (1995) Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: Overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology, 109, 671-680. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(95)90373-9 [5] Frank, L., Kleinman, L., Rentz, A., Ciesla, G., Kim, J.J. and Zacker, C. (2002) Health-related quality of life asso- ciated with irritable bowel syndrome: Comparison with other chronic diseases. Clinical Therapeutics, 24, 675- 689. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(02)85143-8 [6] Chang, F.Y. and Lu, C.L. (2007) Irritable bowel syn- drome in the 21st century: Perspectives from Asia or South-east Asia. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepa- tology, 22, 4-12. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04672.x [7] Kim, Y.J. and Ban, D.J. (2005) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome, influence of lifestyle factors and bowel habits in Korean college students. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42, 247-254. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.015 [8] Dai, N., Cong, Y. and Yuan, H. (2008) Prevalence of ir- ritable bowel syndrome among undergraduates in South- east China. Digestive and Liver Disease, 40, 418-424. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2008.01.019 [9] Dong, L., Dingguo, L., Xiaoxing, X. and Hanming, L. (2005) An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syn- drome in adolescents and children in China: A school- based study. Pediatrics, 116, e393-e396. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2764 [10] Dong, Y.Y., Zuo, X.L., Li, C.Q., Yu, Y.B., Zhao, Q.J. and Li, Y.Q. (2010) Prevalence of irritable bowel syn- drome in Chinese college and university students as- sessed using Rome III criteria. World Journal of Gastro- enterology, 16, 4221-4226. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i33.4221 [11] Talley, N.J. (1999) Irritable bowel syndrome: Definition, diagnosis, and epidemiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 13, 371-384. doi:10.1053/bega.1999.0033 [12] Miwa, H. (2008) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Japan: Internet survey using Rome III criteria. Journal of Patient Preference and Adherence, 2, 143-147. [13] Drossman, D.A., Li, Z., Andruzzi, E., Temple, R.D., Talley, N.J., Thompson, W.G., et al. (1993) US house- holder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders: Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Diges- tive Diseases and Sciences, 38, 1569-1580. doi:10.1007/BF01303162 [14] Kumano, H., Kaiya, H., Yoshiuchi, K., Yamanaka, G., Sasaki, T. and Kuboki, T. (2004) Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in a Japanese representative sample. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 99, 370-376. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04048.x [15] Tan, Y.M., Goh, K.L., Muhidayah, R., Ooi, C.L. and Salem, O. (2003) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in young adult Malaysians: A survey among medical stu- dents. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 18, 1412-1416. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03212.x [16] Sperber, A.D., Shvartzman, P., Friger, M. and Fich, A. (2007) A comparative reappraisal of the Rome II and Rome III diagnostic criteria: Are we getting closer to the 'true' prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome? European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 19, 441-447. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e32801140e2 [17] Endo, Y., Satake, M., Fukudo, S., Shoji, T., Karahashi, K., Sagami, Y., et al. (2007) The characteristics of high school students with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Japanese Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine, 47, 641- 647. [18] Pan, G., Lu, S., Ke, M., Han, S., Guo, H. and Fang, X. (2000) An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syn- drome in Beijing—A stratified randomized study by clustering sampling. Chinese Medical Journal, 21, 26-29. [19] Xiong, L.S., Chen, M.H., Chen, H.X., Xu, A.G., Wang, W.A. and Hu, P.J. (2004) A population-based epidemi- ologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in Guangdong province. National Medical Journal of China, 84, 278- 281. [20] Li, D.G., Zhou, H.Q., Song, Y.Y., Zong, C.H., Hu, Y., Xu, X.X. and Lu, H.M. (2007) An epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome among adolescents in China. Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine, 46, 99-102. [21] Okami, Y., Kato, T., Nin, G., Harada, K., Aoi, W., Wada, S., et al. (2011) Lifestyle and psychological factors re- lated to irritable bowel syndrome in nursing and medical school students, Journal of Gastroenterology, 46 , 1403- 1410. doi:10.1007/s00535-011-0454-2 [22] Thompson, W.G., Longstreth, G.F., Drossman, D.A., Heaton, K.W., Irvine, E.J., et al. (1999) Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut, 45, 43-47. [23] Shinozaki, M., Kanazawa, M., Sagami, Y., Endo, Y., Hongo, M., Drossman, D.A., et al. (2006) Validation of the Japanese version of the Rome Ⅱ modular question- naire and irritable bowel syndrome severity index. Jour- nal of Gastroenterology, 41, 491-494. [24] Hatta, H., Higashi, A., Yashiro, H., Ozasa, K., Hayashi, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  Y. Okami et al. / Open Journal of Gastroenterology 3 (2013) 55-63 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63 OPEN ACCESS K., Kiyota, K., et al. (1998) A validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Japanese Journal of Psy- chosomatic Medicine, 38, 309-315. [25] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (2006) Exercise and physical activity guide for health promotion 2006. [26] Hsiao, Y.C., Chien, L.Y., Wu, L.Y., Chiang, C.M. and Huang, S.Y. (2010) Spiritual health, clinical practice stress, depressive tendency and health-promoting behav- iours among nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nurs- ing, 66, 1612-1622. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05328.x [27] Chan, C.K., So, W.K. and Fong, D.Y. (2009) Hong Kong baccalaureate nursing students’ stress and their coping strategies in clinical practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25, 307-313. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2009.01.018 [28] Jimenez, C., Navia-Osorio, P.M. and Diaz, C.V. (2010) Stress and health in novice and experienced nursing stu- dents. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 442-455. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05183.x [29] Timmins, F. and Kaliszer, M. (2002) Aspects of nurse education programmes that frequently cause stress to nursing students—Fact-finding sample survey. Nurse Education Today, 22, 203-211. doi:10.1054/nedt.2001.0698 [30] Jafri, W., Yakoob, J., Jafri, N., Islam, M. and Ali, Q.M. (2005) Frequency of irritable bowel syndrome in college students. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 17, 9-11. [31] Okeke, E.N., Agaba, E.I., Gwamzhi, L., Achinge, G.I., Angbazo, D. and Malu, A.O. (2005) Prevalence of irrita- ble bowel syndrome in a Nigerian student population. Af- rican Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences, 34, 33- 36. [32] Faresjö, A., Grodzinsky, E., Johansson, S., Wallander, M.A., Timpka, T. and Akerlind, I. (2007) Psychosocial factors at work and in every day life are associated with irritable bowel syndrome. European Journal of Epidemi- ology, 22, 473-480. doi:10.1007/s10654-007-9133-2 [33] Hazlett-Stevens, H., Craske, M.G., Mayer, E.A., Chang, L. and Naliboff, B.D. (2003) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome among university students: The roles of worry, neuroticism, anxiety sensitivity and visceral anxi- ety. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 501-505. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00019-9 [34] Gros, D.F., Antony, M.M., McCabe, R.E. and Swinson, R.P. (2009) Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety and depres- sion. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 290-296. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.004 [35] Shen, L., Kong, H. and Hou, X. (2009) Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and its relationship with psy- chological stress status in Chinese university students. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 24, 1885- 1890. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05943.x [36] Drossman, D.A. (1998) Presidential address: Gastrointes- tinal illness and the biopsychosocial model. Psychoso- matic Medicine, 60, 258-267. [37] Pinto, C., Lele, M.V., Joglekar, A.S., Panwar, V.S. and Dhavale, H.S. (2000) Stressful life-events, anxiety, de- pression and coping in patients of irritable bowel syn- drome. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 48, 589-593. [38] Hosoda, S. (2004) Life style and discomfort on defeca- tion. Juntendo Medical Journal, 50, 330-337. [39] Burr, R.L., Jarrett, M.E., Cain, K.C., Jun, S.E. and Heit- kemper, M.M. (2009) Catecholamine and cortisol levels during sleep in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 21, 1148-1197. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01351.x [40] Jarrett, M.E., Burr, R. L., Cain, K.C., Rotherme l, J.D. and Landis, C.A. and Heitkemper, M.M. (2008) Autonomic nervous system function during sleep among women with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Diseases and Sci- ences, 53, 694-703. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-9943-9 [41] Dumbrell, S. and Mathai, D. (2008) Getting young men to eat more fruit and vegetables: A qualitative investiga- tion. Australian Health Promotion Association, 19, 216- 221. [42] Hussein, R.A. (2011) Can knowledge alone predict vege- table and fruit consumption among adolescents? A tran- stheoretical model perspective. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 86, 95-103. doi:10.1097/01.EPX.0000407136.38812.55 [43] Sakata, Y., Ishigure, S. and Shimbo, S. (2000) Weight of feces and its daily fluctuation in young women Part 1. A survey of the relation fecal weight and dietary habits and life-styles. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi, 47, 385-393. [44] Faresjo, A., Anastasiou, F., Lionis, C., Johansson, S., Wallander, M.A. and Faresjo, T. (2006) Health-related quality of life of irritable bowel syndrome patients in dif- ferent cultural settings. Health and Quality of Life Out- comes, 4, 21. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-21 Abbreviations BMI: body mass index; HADS: hospital anx iety and depression scale; HAD-A: subscale for anxiety; HAD-D: subscale for depression; G I: gastrointestinal; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-A: alteration type IBS; IBS-C: constipation-predominant IBS; IB S - D : di arrhea-predominant IBS; METS: metabolic equivalents; SD: standard deviation.

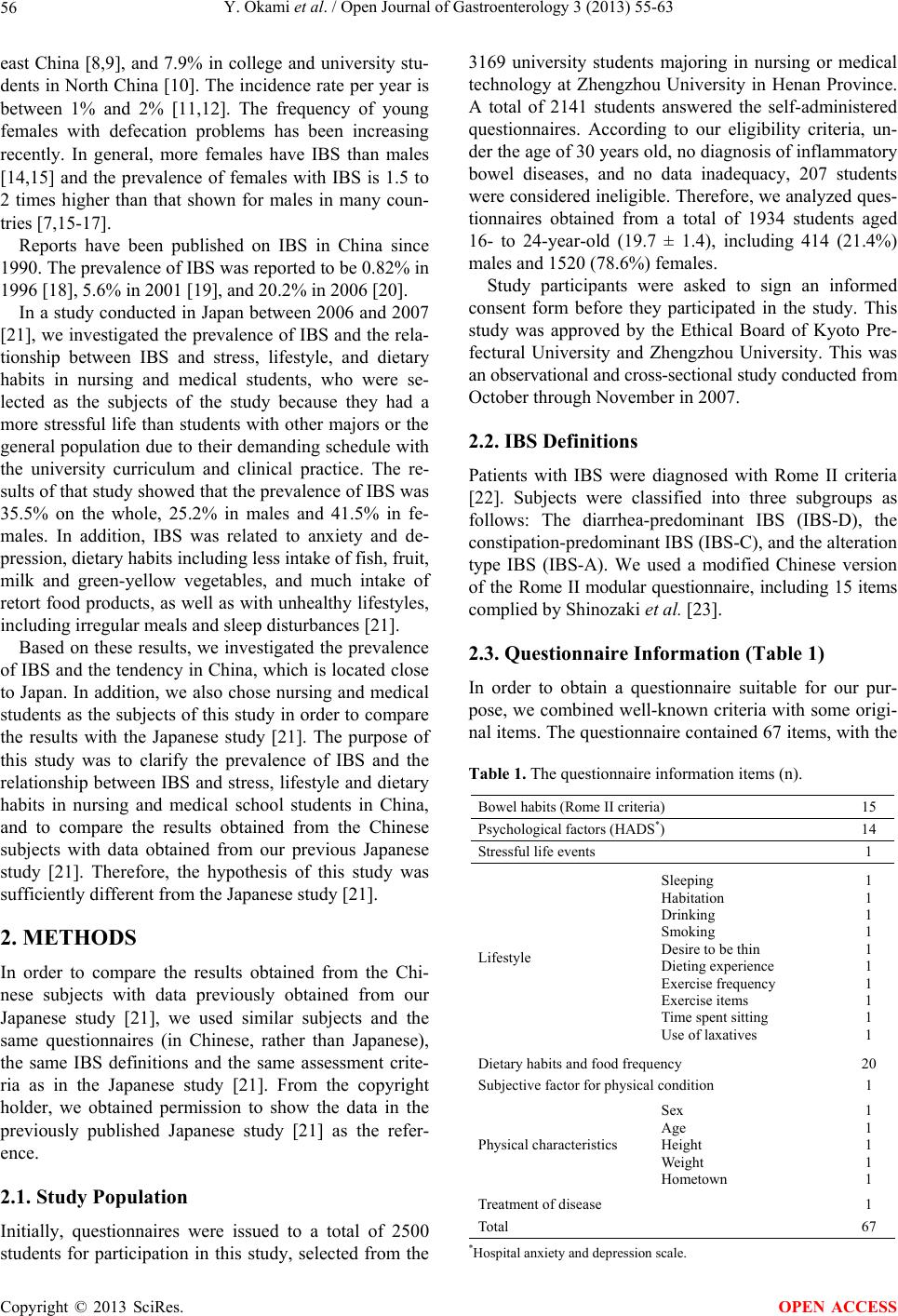

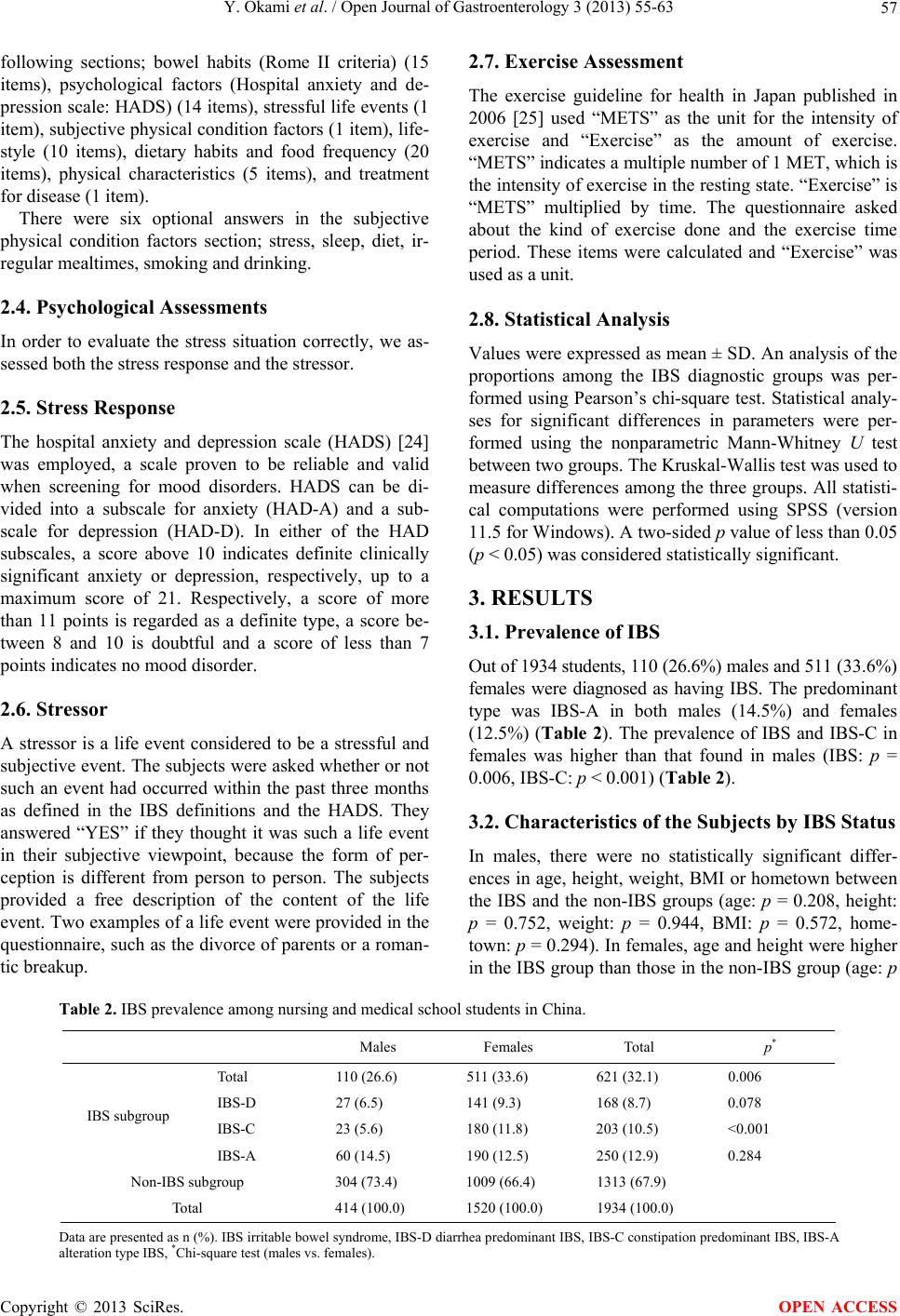

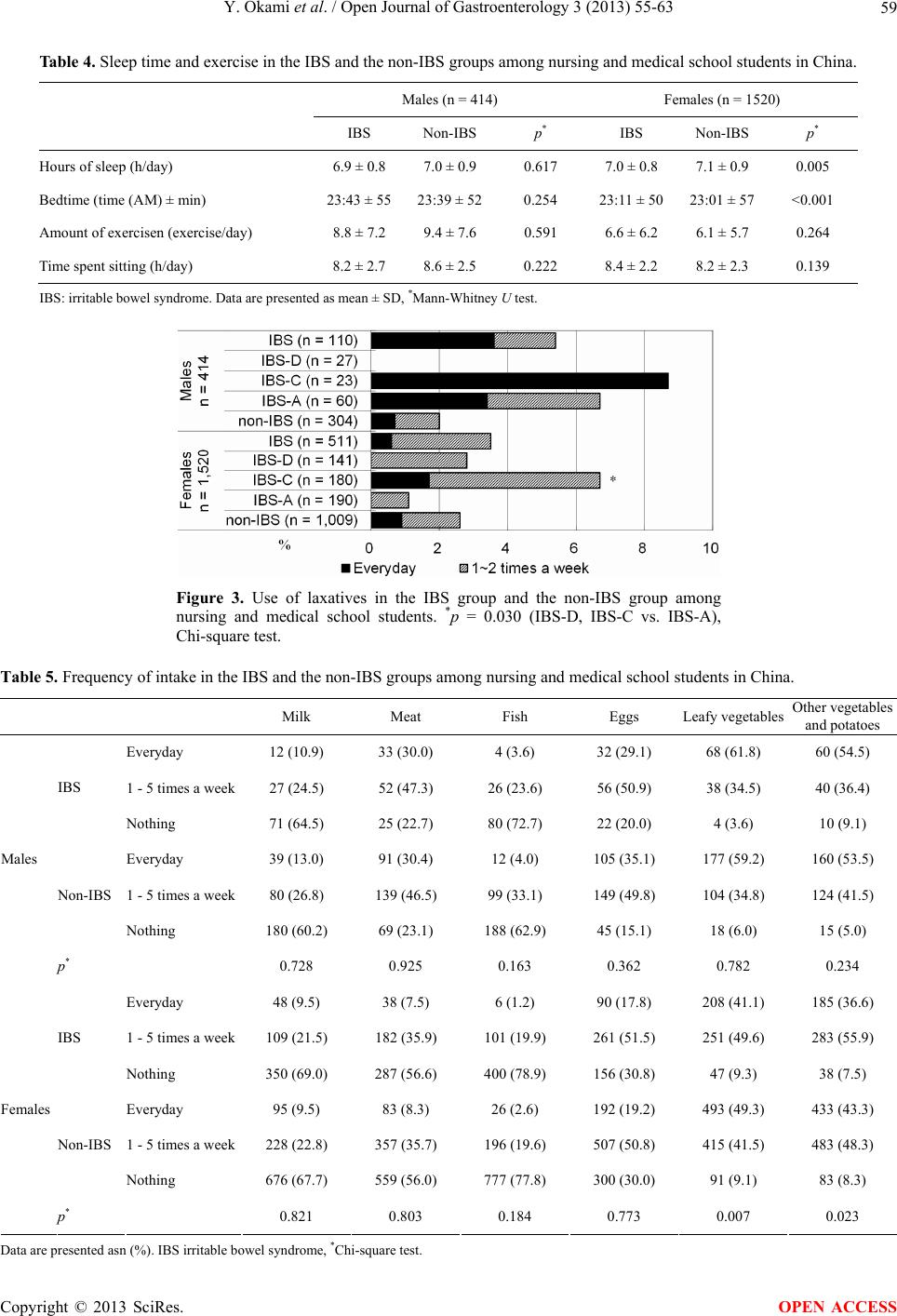

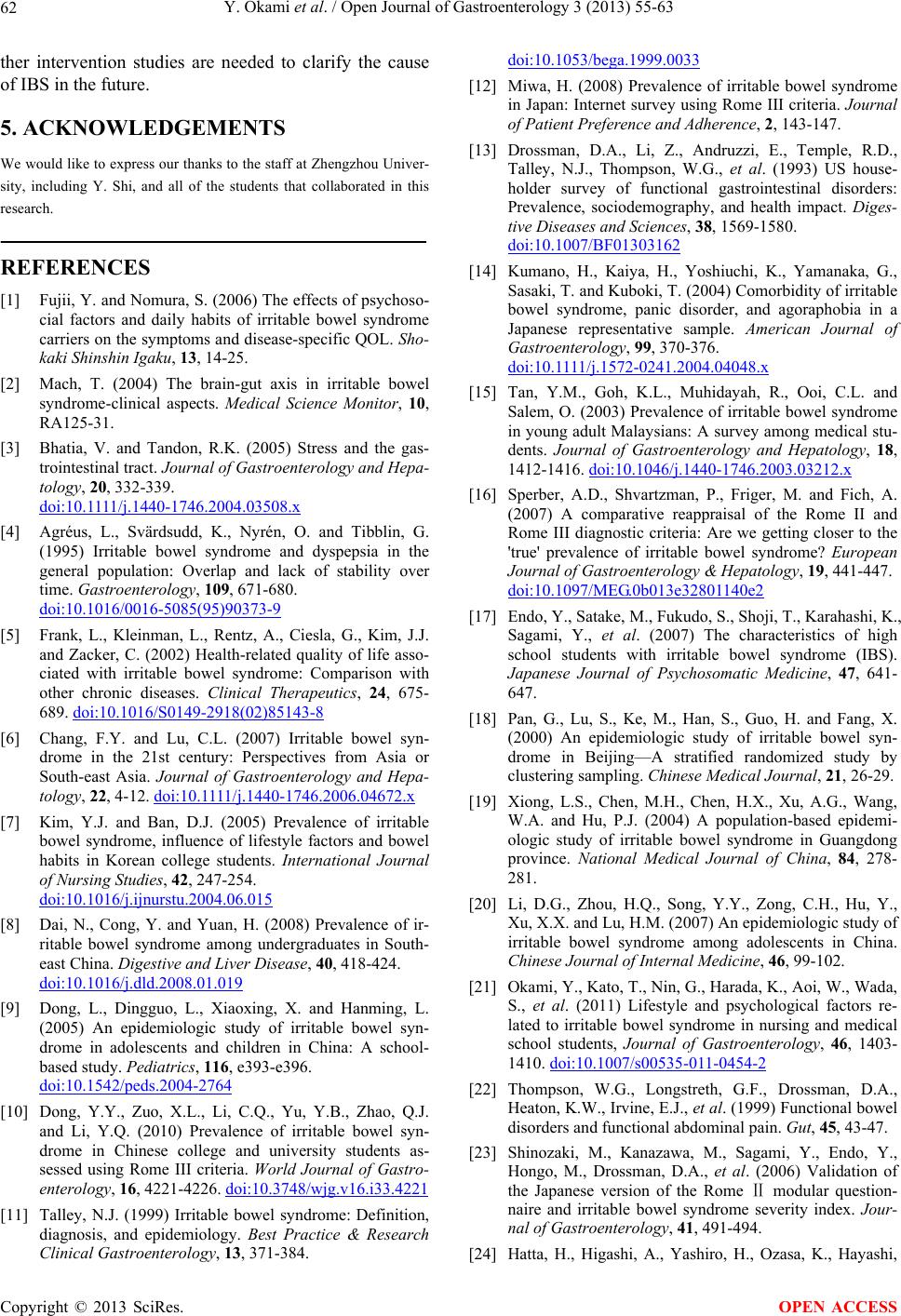

|