K. D. F. ALKAHTANI

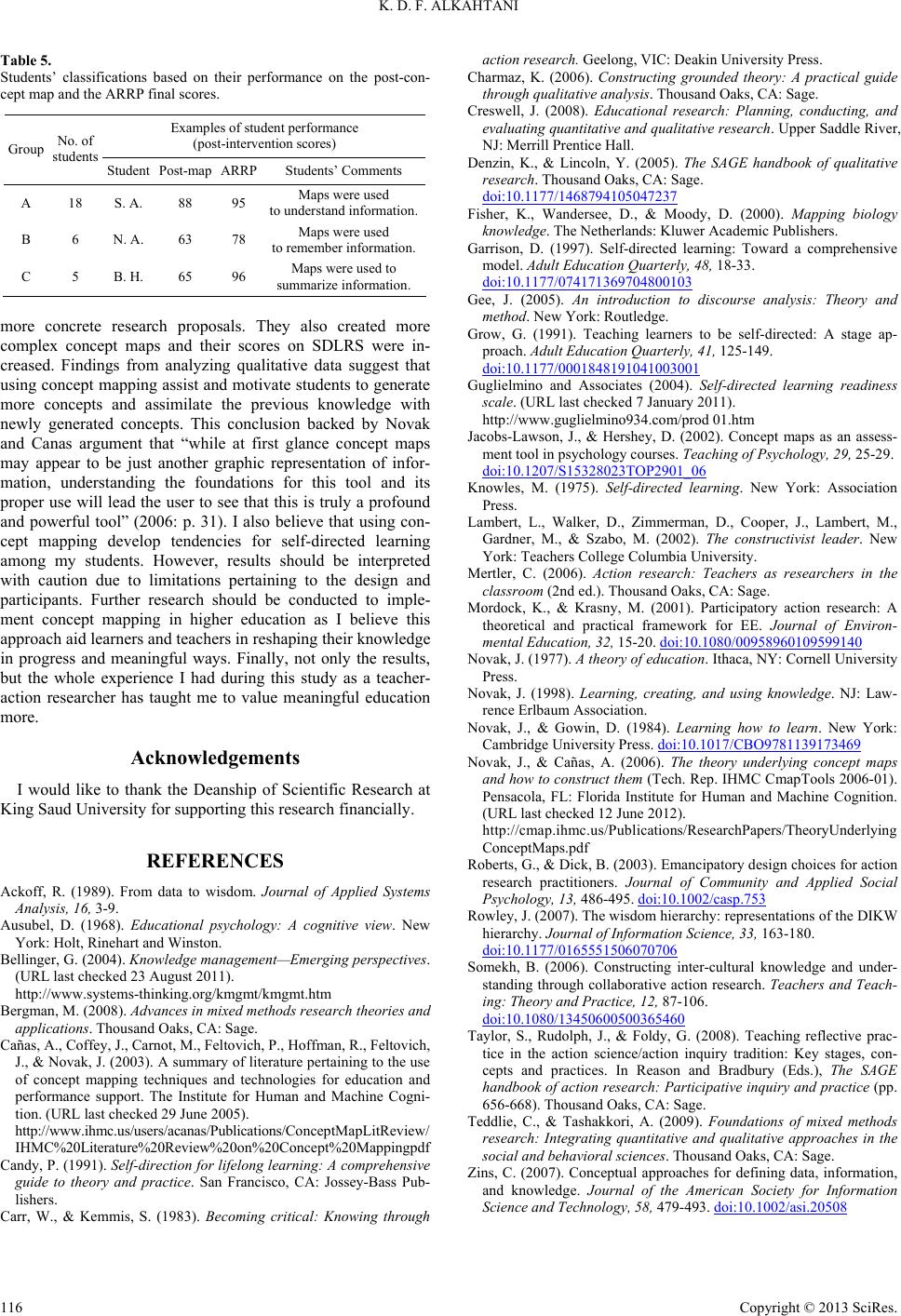

Table 5.

Students’ classifications based on their performance on the post-con-

cept map and the ARRP final scores.

Examples of student perfo rmance

(post-interve nti on s c ore s)

Group No. of

students Student Post-map ARRP Students’ Comments

A 18 S. A. 88 95 Maps were used

to understand information.

B 6 N. A. 63 78 Maps were used

to remember information.

C 5 B. H. 65 96 Maps were use d to

summarize in f o rmation.

more concrete research proposals. They also created more

complex concept maps and their scores on SDLRS were in-

creased. Findings from analyzing qualitative data suggest that

using concept mapping assist and motivate students to generate

more concepts and assimilate the previous knowledge with

newly generated concepts. This conclusion backed by Novak

and Canas argument that “while at first glance concept maps

may appear to be just another graphic representation of infor-

mation, understanding the foundations for this tool and its

proper use will lead the user to see that this is truly a profound

and powerful tool” (2006: p. 31). I also believe that using con-

cept mapping develop tendencies for self-directed learning

among my students. However, results should be interpreted

with caution due to limitations pertaining to the design and

participants. Further research should be conducted to imple-

ment concept mapping in higher education as I believe this

approach aid learners and teachers in reshaping their knowledge

in progress and meaningful ways. Finally, not only the results,

but the whole experience I had during this study as a teacher-

action researcher has taught me to value meaningful education

more.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at

King Saud University for supporting this research financially.

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. (1989). From data to wisdom. Journal of Applied Systems

Analysis, 16, 3-9.

Ausubel, D. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New

York: Holt, Rinehart a n d Winston.

Bellinger, G. (2004). Knowledge management—Emerging perspectives.

(URL last checked 23 August 2011).

http://www.systems-thinking.org/kmgmt/kmgmt.htm

Bergman, M. (2008). Advances in mixed methods research theories and

applications. Th o usand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cañas, A., Coffey, J., Carno t, M., Feltovich , P., Ho f fman, R., Feltovich,

J., & Novak, J. (2003). A summary of literature pertai ning to the use

of concept mapping techniques and technologies for education and

performance support. The Institute for Human and Machine Cogni-

tion. (URL last checked 29 June 20 05).

http://www.ihmc.us/users/acanas/Publications/ConceptMapLitReview/

IHMC%20Literature%20Review%20on%20Concept%20Mappingpdf

Candy, P. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning: A comprehensive

guide to theory and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Pub-

lishers.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1983). Becoming critical: Knowing through

action research. Geelong, VIC: Deakin University Press.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide

through qualita t i ve analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and

evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Denzin, K., & Lincoln, Y. (2005). The SAGE handbook of qualitative

research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

doi:10.1177/1468794105047237

Fisher, K., Wandersee, D., & Moody, D. (2000). Mapping biology

knowledge. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Garrison, D. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive

model. Adult Educatio n Quarterly, 48, 18-33.

doi:10.1177/074171369704800103

Gee, J. (2005). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and

method. New York: Routledge.

Grow, G. (1991). Teaching learners to be self-directed: A stage ap-

proach. Adult Education Quarterly, 41, 125-149.

doi:10.1177/0001848191041003001

Guglielmino and Associates (2004). Self-directed learning readiness

scale. (URL last checked 7 January 2011).

http://www.guglielmino934.com/prod 01.htm

Jacobs-Lawson, J., & Hershey, D. (2002). Concept maps as an assess-

ment tool in psychology c o urses. Teaching of Psychology, 29, 25-29.

doi:10.1207/S15328023TOP2901_06

Knowles, M. (1975). Self-directed learning. New York: Association

Press.

Lambert, L., Walker, D., Zimmerman, D., Cooper, J., Lambert, M.,

Gardner, M., & Szabo, M. (2002). The constructivist leader. New

York: Teachers College Columbia University.

Mertler, C. (2006). Action research: Teachers as researchers in the

classroom (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: S a g e .

Mordock, K., & Krasny, M. (2001). Participatory action research: A

theoretical and practical framework for EE. Journal of Environ-

mental Education, 32, 15-20. doi:10.1080/00958960109599140

Novak, J. (1977). A theory of education. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Novak, J. (1998). Learning, creating, and using knowledge. NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum Association.

Novak, J., & Gowin, D. (1984). Learning how to learn. New York:

Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139173469

Novak, J., & Cañas, A. (2006). The theory underlying concept maps

and how to construct them (Tech. Rep. IHMC CmapTools 2006-01).

Pensacola, FL: Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition.

(URL last checked 12 June 2012).

http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryUnderlying

ConceptMaps.pdf

Roberts, G., & Dick, B. (2003). Emancipatory design choices for action

research practitioners. Journal of Community and Applied Social

Psychology, 13, 486- 495. doi:10.1002/casp.753

Rowley, J. (2007). The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW

hierarchy. Journal of Information S c ience, 33, 163-180.

doi:10.1177/0165551506070706

Somekh, B. (2006). Constructing inter-cultural knowledge and under-

standing through collaborative action research. Teachers and Teach-

ing: Theory and Practice , 12, 87-106.

doi:10.1080/13450600500365460

Taylor, S., Rudolph, J., & Foldy, G. (2008). Teaching reflective prac-

tice in the action science/action inquiry tradition: Key stages, con-

cepts and practices. In Reason and Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE

handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp.

656-668). Thous and O aks, CA: Sage.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods

research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the

social and behavioral sciences. T h o u s a nd O a k s , CA: Sage.

Zins, C. (2007). Conceptual approaches for defining data, information,

and knowledge. Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, 58, 479-493. doi:10.1002/asi.20508

Copyright © 2013 SciR es .

116