Creative Education 2013. Vol.4, No.1, 62-70 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2013.41009 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 62 Using Problem Based Learning to Develop Class Projects in Upper Level Social Science Courses: A Case Study with Recommendations Dani V. McMay1*, Kathleen Gradel2, Christopher Scott1 1Department of Psychology, SUNY-Fredonia, Fredonia, USA 2Department of Language, Learning & Leadership, College of Education, SUNY-Fredonia, Fredonia, USA Email: *Dani.McMay@fredonia.edu Received October 27th, 2012; revised November 29th, 2012; accepted December 13th, 2012 Problem Based Learning is often used as the pedagogy for an entire course. However, instructors wanting to try PBL for the first time may find this intimidating. An alternative is to use this pedagogy for a class project and not the entire class. Students in an upper level psychology course used Problem Based Learn- ing to create a transitional facility for ex-offenders in a rural county where currently none exists. Students gained insight into community services, the needs of the target population, and how to match clients’ need with services in the community. This project can be used as a model for instructors in the fields of psy- chology, sociology and social work. Keywords: Problem Based Learning; Class Projects; PBL; Social Science Education; Group Projects; Grading Rubrics Introduction Pairing field-based and service-learning experiences with traditional campus-based courses is becoming more typical in professional preparation programs (Academy of Criminal Jus- tice Sciences, 2005; Davidson, Petersen, Hankins, & Winslow, 2010; Harvey & Mitchell, 2006; Kenny, Simon, Kiley-Brabeck, & Lerner, 2002; Kezar & Rhoads, 2001). However, there are often a great many challenges to setting up service learning opportunities for an entire class in the short span of a semester (e.g., Kretchmar, 2001; Tapp & Macke, 2001) An alternative non-field-based instructional model for courses that intention- ally combines campus-based pedagogy with authentic, real world-referenced work is Problem Based Learning (hereafter, PBL). PBL is a pedagogy model in which students work to solve real-life problems, engaging in critical thinking and deep learning through an instructor-supported but largely stu- dent-driven inquiry experience (e.g., Thomas, 2000; Thomas, Mergendoller, & Michaelson, 1999; Woolfolk, 2010). Typically conducted in student groups, PBL offers relevant opportunities for course instructors to embed authentic learning experiences in their college coursework (e.g., Murray & Sum- merlee, 2007). In PBL, real-world problems are used to stimu- late deeper engagement in course content, hopefully resulting in deeper understanding of concepts and practices used in the discipline (Blumenfeld et al., 1991; Marx, Blumenfeld, Krajcik, & Soloway, 1997). Core to PBL is the instructor’s facilitation of student-driven constructive investigation through inquiry, knowledge gathering, and generation of solutions (Grant, 2002). Typically, problem investigation is pursued over a period of time, culminating in final products that address authentic prob- lems and/or that mimic products such as those that would be generated in the field (Jones, Rasmussen, & Moffitt, 1997; Thomas, Mergendoller, & Michaelson, 1999). Using this pedagogy, content material that is normally dis- seminated in lecture form during class instead is learned as the students go through the process of solving problem cases pre- sented by the instructor. Class meeting time is devoted to working on the presented problem case, typically in small groups, with the instructor serving as a facilitator for the stu- dents’ efforts rather than as the lecturer regarding course con- tent. The problem case may take several class sessions to solve, or new problem cases may be presented at each class session. The activities that students experience in PBL are similar to those skills required of most people in the workplace: develop- ing and using novel solutions to problems encountered, effec- tively working with others to solve the problems under consid- eration, and adjusting activities based on feedback from super- visors. According to Barron et al. (1998), there is ongoing commit- ment among educators, standards-producing organizations, and accreditation bodies to “push the envelope” on connecting knowledge to application; PBL has been cited as a model that can, indeed, do that. Additionally, Barron et al. (1998) reported that students experiencing PBL instruction demonstrated better understanding of interrelated concepts. Beyond traditional knowledge and skills outcomes, PBL is associated with higher expectations for student ownership of learning, as well as meaningful opportunities for students to self-assess (Brown, Bransford, Ferrara, & Campione, 1983; Stiggins, 1995). Much of the research on PBL describes using this pedagogy as the structure for an entire course, with all class sessions be- ing comprised of problem solving work by students, and all content being acquired through the problem solving process (e.g. Murray & Summerlee, 2007; Searight & Searight, 2009; Thomas, 2000; Woolfolk, 2010). However, this type of com- plete and radical change in the way a course is organized can be *Corresponding author.  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. off-putting for an instructor wanting to try PBL for the very first time. One way to incorporate the key aspects of (and the benefits associated with) PBL into a course initially is to use PBL for completion of a large class project rather than for the entire term. The project may be worked on throughout the en- tire course as one part of each class meeting, or during a set number of class sessions. All work on the project is done using PBL, but the instructor can still provide much of the content for the course through lectures. Courses in the social sciences (e.g., social work, criminal justice, and psychology) lend themselves particularly well to exploring the use of PBL. First, the subject matter of these dis- ciplines often focuses on problems within society where only limited success has been achieved in finding good solutions. Second, many students in these disciplines will become li- censed practitioners with required competencies in specific skill sets needed to qualify for licensure. PBL helps students develop skills that are in line with the skills and knowledge required by these disciplines for board certification. Finally, students enter- ing these professions will most often be required to assess the needs of clients and help ensure those clients receive services. This component of assessing a current problem state and find- ing an effective solution is at the heart of PBL. The project described here was one component of an up- per-level forensic psychology course on incarceration and community reentry. The project gave the students the opportu- nity to work on the real-world problem of matching service providers in the community with needs of ex-offenders transi- tioning from prison back into the community. Other than the work on this class project, class sessions were comprised of lectures by the instructor and guest speakers and did not use the PBL pedagogy. The specifics of our project are only used to illustrate the principles of designing such a class project and can serve as a template for an instructor wanting to include PBL as one component of a course. Our example can be adapted for any upper level social science course where the instructor desires the students to work on a real world problem in the discipline. Designing the PBL Project When using PBL to develop a class project, there are several things to consider: construction of the problem case, determin- ing how group assignments will be made, and determining how the final project will be assessed. The instructor should spend time completely developing each of these elements prior to assigning the project to the students. In this section, we will discuss the development of each of these elements and provide templates from our own experience. Problem Case Construction Following the definition of PBL developed by Thomas (2000), the problem case used for the project should focus stu- dents on central concepts within the discipline, and should be based on a real problem in the area of inquiry. The instructor should pick one or more of the learning objectives for the course and develop a good problem case that is not more than one paragraph in length (For an overview of steps to creating good PBL problem cases please see Searight & Searight, 2009). Our project was designed to give students a way to identify the full scope of services needed by ex-offenders upon their release from incarceration, and to evaluate the accessibility of these services in a rural setting. The full problem case statement for our project was: “Can you create a facility that can provide transitional services for criminal offenders being released into our county? You will need to find a potential building space to rent, decide which services to provide inside the facility (and which to access elsewhere), and organize your facility to effec- tively provide services and information between the hours of 8 am and 6 pm. You may provide any service at the facility you desire, but for all services, there must be a likely source of funding (e.g., grants, allocation of current funding streams). Although your facility is entirely imaginary, your facility must be viable in the real world; running a facility and providing services costs money, thus you are required to find a potential source of funding for every service provided.” The example problem case statement above includes several tenets of good problem case construction (Searight & Searight, 2009). First, the problem case should have a pre-determined scope of enquiry. If a problem case statement is too vague, students’ inquiries may expand in ways that make it difficult for them to actually come up with a good solution to the problem. If the problem case statement is too strict, students may not discover enough of the content material that makes PBL a good alternative to lecture-based instruction. In our example, the scope was limited to creating a non-residential facility and re- quiring a potential course of funding for each service provided. By requiring students to find funding for all services provided it was less likely students would dream beyond a truly feasible real-world solution. Second, the problem case statement should include specific “clues” to areas and places the students should explore to find solutions to the problem. In our example, it was indicated that some services could be provided outside the fa- cility, hinting that students should explore service providers in the surrounding community. In addition, by specifically requir- ing funding sources for services proposed, students should be alerted to explore sources of funding in the government and the community as part of their project. Finally, the problem case statement should leave plenty of room for novel solutions to the problem. For projects in the social sciences, part of the interest for the students will lie in coming up with a solution to a cur- rent real-world problem that has not already been solved. In our example, there is no such transitional facility in the county the college is located so there is no concrete model to follow nearby. Making the facility non-residential and requiring poten- tial funding put real world limits on the scope of their informa- tion search, but the design, location, and choice of services provided at their facility was entirely up to the students in the course. The balance between limiting the scope too much (which can dampen creativity) and having too few constraints (which can end with the students overwhelmed by choices well beyond a feasible end product) is a delicate one. Keeping with the three tenets of problem case construction listed above should help the instructor to strike the right balance. Group Assignments There are always challenges when determining working groups for large class projects and these can be even more dif- ficult when attempting to follow a PBL approach. The first challenge is determining who will choose the categories or topics each working group will focus on. The instructor may predetermine group topics based on desired learning outcomes, or the instructor can allow students to determine the exact Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 63  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. groupings from a larger list of choices. The latter is more in line with the PBL approach, but there is risk of not having the right working groups to achieve the desired learning outcomes. Thus, even if the instructor allows the students to self-select group topics, the instructor should provide guidance to help ensure each group has a separate part of the whole project, with no one grouping having too large a workload. A second challenge is deciding how individual students will be assigned into each working group. Students may be ran- domly assigned to working groups, the instructor may assign students to working groups based on a predetermined criterion, or students may be allowed to self-select their working group. Again, the latter is most in line with the PBL approach. In addi- tion, research indicates that when students self-select their group for assignments they are more invested in the projects and achieve better learning outcomes (Myers, 2012; Papado- poulos, Lagkas, & Demetriadis, 2012). It is best to have each group have the same number of participants, if possible, and if the working groups are to coordinate with each other to produce a single final outcome, it is best to limit the number of individ- ual working groups. In determining groups for our class project, we used some- what of a hybrid of the approaches listed above. For ease of working on such a large project, as the course had 30 students enrolled, the instructor pre-determined that the class would be divided into five working groups of six students each. The stu- dents were told that each working group should focus on pro- viding one service area to the ex-offender. The instructor led a discussion of the various service areas that might be provided, writing them on the board in a list as students suggested them. However, students were not told which of the areas on the list to include in their facility; instead, they were to determine this as a class through discussion. Students were told to first deter- mine the five areas of service provision for the facility, and then assign themselves to the group that most interested them per- sonally. It was stressed that there were to be exactly six stu- dents in each group, and that compromises might need to be made so that every student could find a group that was satis- factory to them. If there was insufficient interest in one service area, perhaps another service area would be a better choice for the facility. The instructor left the room, and the students were given 30 minutes to decide their groupings. Project Ass essment The last major component of designing a class project using PBL is to determine how the learning objectives will be as- sessed. There are many ways of assessing student performance and learning efficacy. The most common way is having all assessment of the project done solely by the instructor. The instructor can assess progress at various stages of project com- pletion, or can do one summative evaluation of the final com- pleted project. If the instructor desires a more complete picture of the problem solving process inside the working groups, we also recommend including peer reviews and self-assessment. A growing body of research indicates that including these other types of assessment are useful for improving student learning outcomes, especially in group work (e.g., Crack, 2007; Saito & Fujita, 2009; Scott, Van der Merwe, & Smith, 2005; Topping, 1998, 2009) For our project, students presented their solution to the prob- lem case in one large oral presentation with each working group presenting individually as one section of the whole. Instead of presenting solely to the instructor, the oral presentation was given to a group of approximately 60 stakeholders from the rural community surrounding the college (e.g., social workers, parole officers, correctional officers, court appointees, and law enforcement). Each working group was to present their groups’ contribution to the whole solution. We included the three types of assessment mentioned above: summative assessment by the instructor, peer review by working group members and self-assessment. We will cover each of these assessment types in turn. Assessment by the Instruct or When the instructor is assessing the project, using rubrics al- lows for more uniformity in grading and, if given to the stu- dents at the project’s start, serves to solidify the instructor’s expectations for the final product (for an overview of creating and using rubrics for assessing learning, please see Burke, 2011; Quinlan, 2011; Stevens & Levi, 2004). Research indicates that students generally favor the use of rubrics in grading (e.g. Holmes & Smith, 2003; Reddy & Andrade, 2010). Students perceive that rubrics increase their understanding of instructors’ expectations and rationale for point deductions (Gezie, Khaja, Chan, Adamek, & Johnsen, 2012), however, rubrics are re- garded most useful when given to the students at the time the assignment is made (e.g., Petkov & Petkova, 2006; Reitmeier, Svendsen, & Vrchota, 2004). In addition, simply handing out the rubric is not enough; many students need instruction on how to use the rubric as a tool toward increased performance (Green & Bowser, 2006; Reddy & Andrade, 2010). For our project, the rubric used to grade the oral presentation was distributed at the same time as the assignment was given. A copy of the rubric used can be found in Appendix B. Stu- dents were shown that there were two parts to the rubric: one part evaluated the cohesiveness and content of their working group’s presentation, and the second part evaluated their per- sonal performance during their group’s presentation. The ma- jority of the criterion for individual student performance was focused on their oral presentation skills. Individual students were required to orally present at least two minutes of their working group’s entire presentation. This ensured that each student contributed to the actual oral presentation, not just to research and problem solving strategy for the final project. The majority of criterion for grading the performance of each working group was focused on content. Each working group was required to turn in copies of all materials used during their presentation (e.g., handouts, copies of Powerpoint slides) to assist in accurate grading. Our rubric used a 4-point Likert-type scale with point values corresponding to Exceptional 4), Ade- quate 3), Marginal 2) and Unacceptable 1). As mentioned ear- lier, there are many resources to assist instructors with making assignment-specific rubrics. (Several well respected online sites that offer assistance with creating rubrics for specific assign- ments and disciplines are: rubistar.4teachers.org, www.teach-nology.com, and rubrics4teachers.com). Peer Re vi ew A common complaint students express regarding group pro- jects is the worry that someone in their group will not perform well and this will affect the final grade for the others. A typical desired learning outcome for group projects is for individual students to successfully work together as one unit. When per- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 64  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. sonality and strategy conflicts arise between students, the PBL pedagogy encourages the instructor to direct the student(s) to go back to the group and work it out without interference. Re- solving individual conflicts within the group is, indeed, part of the project. However, simply encouraging the students to work out individual conflicts themselves within the structure of the working group (much as they would have to in the work envi- ronment), often does little to ease frustration when conflict is already evident. One way to diminish this type of frustration is for instructors to be very clear about their expectations for the group work process beforehand (Burdett, 2007). The use of grading rubrics can help all students in the group be equally aware of the performance expectations and should help to di- minish conflict regarding what the students should do in order to receive high marks. An additional way to ease the frustration of group conflict is to give the students in each working group a chance to assess their fellow group members using peer review. Research by Yining and Hao (2004) showed that students’ fa- vor peer review as a way to reduce group conflict and social loafing on the part of individual group members. The same study also indicated that to be most effective, students should be told how the peer evaluations will be used. Students primar- ily take the assessments seriously when their feedback is in- corporated into their peers’ final grades. If the peer reviews are merely a way to inform the professor of social loafing or group conflict, and are not incorporated into the final grading scheme for each student, the motivation to take the review seriously is greatly decreased (Yining & Hao, 2004). In order to be most beneficial, students should be trained on how to complete fair and consistent peer reviews (e.g., Khabiri, Sabbaghan, & Sab- baghan, 2011). For the peer review for our project, we designed a rubric for the students to use that addressed three areas of group work: quality of work, team membership and communications (A copy of this grading rubric used can be found Appendix C). For each area addressed, the rubric included a letter grade and a detailed description of the level of performance that was re- quired to earn that grade. Students were specifically told that the rubric provided was to increase assessment consistencies between working groups as well as within each working group. In our case, the peer review rubric was the same rubric used for self-assessment, which we will turn to next. Student Self-Assessment Including student self-assessment is useful for gaining fur- ther understanding into the group process and dynamics during completion of the project (e.g., Falchikov, 2004; Li, 2001). This form of assessment affords the student a chance to reflect on the entirety of the group process and their personal contribution to the final product. It is also a good window for the instructor to view the contrasts between group-mates’ perceptions of each other and a student’s perception of their own efforts and con- tributions. The scoring grid used in our project can be found in Appendix A. It was our choice to use the same rubric for self-assessment as for peer review. The advantage of this ap- proach is that students will be grading themselves on the same criterion as they graded their peers. The disadvantage of this approach is that it is more limiting in the types of self-reflection the instructor is able to ask the student to complete. Although we did not choose to do this, it may be preferable to add several questions to the self-assessment that are solely focused on self-reflection. (Our project chose instead to have all students rate their experience with the PBL process). Consideration of Target Audience An interesting opportunity presents itself when asking stu- dents to work on a real-world problem. If the problem case used in the project is relevant to stakeholders in the community sur- rounding the campus, the instructor should consider inviting interested stakeholders to the final presentation. Inviting com- munity members to attend the students’ presentation of their solution to the problem case adds a level of realism to the stu- dents’ efforts often rare in class assignments. The instructor will want to monitor the progress of the project very carefully to ensure that the presentation will warrant the time investment of the community members. In the case of our project, the stakeholders included people in law enforcement, probation/parole, social services, and local volunteer and faith-based organizations involved with reentry. Many of the stakeholders were already known to the instructor through their work in their primary area of research. However, contact information for people in these agencies and organiza- tions is readily available online. Approximately five weeks prior to the presentation date (which was during final exam week at the college), the instructor informed the students in the course that the results of their group effort on this project might be of interest to stakeholders in the community and that stake- holders in the area of reentry would be invited to their presenta- tion. The instructor shared a list of all the agencies and organi- zations that an invitation would be sent and asked the students to indicate any omissions. Once the invitation list was finalized, the instructor sent out a brief synopsis of the class project along with an invitation to attend the presentation. In addition, the letter indicated that the addressee should feel free to invite any other interested parties in their organization. The invitations were sent on letterhead through the postal service as well as through email. The instructor invited approximately 100 stake- holders and the night of the presentation more than 60 were in attendance. Managing Progress of the PBL Project Once the class project is assigned, the instructor’s role during class sessions should move into one of support and away from one of direct leadership. The instructor should refrain from structuring the work time for groups or leading the groups’ pursuit of background information, solutions, or design. The primary assistance provided during the work sessions should be to remind students of the pre-set scope of the project. In our example, students were reminded that they needed to have a viable source of funding for each element of their programming or service offered in their transitional facility. It is important to note that during in-class work sessions, students often will ask questions such as, “Can we do X?” or “How should we accomplish Y?” In order to make PBL effec- tive, the instructor should turn these questions back over to the students. In order for students to learn how to solve problems in their own manner, they are the ones who need to find answers to questions they encounter along the way (Thomas, 2000). Even if the instructor knows the answer to the question asked, the instructor should reply along the lines of, “I don’t know, can you?” or “How long is typical for appointments with clients to last?” For example, when our students asked which social service agencies they should contact for information, the in- Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 65  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 66 structor guided students to explore the county’s online phone book and determine the agency that best fit their needs, but did not answer the question directly. Example Class Project Outcome At the end of the semester, more than 60 stakeholders at- tended a presentation of the students’ class project. Each work- ing group did an oral presentation that lasted approximately 15 minutes, with five minutes for questions. Each student in a group was required to contribute at least two minutes to the oral presentation of their group. Elements of the facility presented by each group included a list of services that could be provided by that group, the sources of funding that could be used to pro- vide these services, and a mock-up schedule of how their group could put their part of the building space to best use. Each group presented their service component in isolation, culminat- ing in a final summation in which one person from each group presented as a member of a core group of organizers. This last part of the presentation was completely developed by the stu- dents themselves, and had not been a part of the project re- quirements. These five core students had served as liaisons among all the individual groups, determining how all the services could best work together to help a person in transition or family members of those still incarcerated. During the presentation, this group discussed a sample case of one person coming to the facility with various needs, demonstrating how the facility would coor- dinate as a whole to help this individual. It is important to note that in the subsequent semesters this class project has been assigned, there are always unique ele- ments developed by the students. When students are required to solve a problem, they rise to this challenge in surprising ways. Often the topics chosen for each working group are not the same categories as previous semesters. Given the changing availability of funding, the changing nature of community ser- vice provision, and the specific interests of students from se- mester to semester, the same problem case statement can result in dramatically different solutions. This variance contributes to the excitement for both students and instructors. Student Evaluations of Experience In addition to their peer reviews and self-assessment, as part of the general end-of-course evaluation, the students were asked to rate the PBL experience. The students overwhelmingly liked using PBL, and they reported that they benefited from it. When asked if they would take another course that incorporated PBL, 100% of the students chose ratings from “maybe” to “defi- nitely”, with 44% saying that they “definitely” would. Students were also asked to assess their learning experience by respond- ing to seven statements specific to the nature of the project. A 5-point scale was used with anchor points ranging between “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree”. Table 1 summarizes results of this questionnaire. The first three statements asked the students to rate how well work on the project increased their ability to find and use resources from a variety of sources. These statements assessed students’ impressions of their in- crease in general problem-solving skills after completing the project. When asked if work on the project had increased their ability to gather and use information to solve problems, 96% of the students responded that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with those statements. With regard to increasing the general ability to find and analyze information, 92% of students an- swered “strongly agree” or “agree”. The last four statements on the evaluation asked about disci- pline-specific skills that students should have developed. For example, one question asked the student to indicate the extent to which he/she understood resources and services currently available in the county; this is information that a person work- ing in the field of social work and/or mental health services would be expected to know. Ninety-six percent of the students indicated they “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with that state- ment. Discussion and Recommendations Completing a project of this type can provide students a way Table 1. Student perceptions of learning after project completion. Rating Question: Strongly agree Agree Neither agree or disagree Disagree Strongly disagree The structure of this project helped me learn how to obtain information from a variety of sources. 73% 23% 4% - - As a result of work on this project, my ability to use a variety of resources to solve a problem has increased. 73% 23% 4% - - As a result of work on this project, my ability to find, read and analyze information has improved. 46% 46% 8% - - After developing the reentry facility I have a better understanding of the elements needed in the first 90 days by a person coming out of prison. 88% 12% - - - After developing the reentry facility I have a better understanding of the programs and opportunities currently available in Chautauqua County for men and women coming out of prison. 69% 27% 4% - - After developing the reentry facility I have a better understanding of how many different services available during reentry can be coordinated to help achieve a better result. 65% 27% 8% - - After developing the reentry facility I have a better understanding of sources of funding available for reentry from the federal government. 15% 78% 4% 4% -  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. to learn about the challenges similar to those that they will face in their future careers. If the project is well designed, students will work at high levels of critical thinking by evaluating and synthesizing design factors and their potential impacts. The “real world” aspect of the problem in their own community created special interest for many students who lived on campus and rarely left its grounds. One challenge to implementing PBL is the reluctance of stu- dents to engage in a new way of learning when their focus is often entirely on final grades. One way to counter this anxiety is to be clear about the problem statement, as well as both the parameters within which students are to work, and how their work will be evaluated. In this study, requiring students to find a potential source of funding for all services provided proved helpful in curbing students’ desire to “fix all the problems in the world”. In addition, the instructor’s anticipation of barriers that students would likely face helped to diminish frustration. For example, the instructor chose to limit the facility created by the students to a non-residential facility operating between the hours of 8 am-6 pm. This pre-determination eliminated the major hurdle of zoning restrictions for residential facilities (par- ticularly those for ex-offenders) that students would face when seeking an acceptable space to rent. Using PBL in the classroom poses challenges for the in- structor, as well. Students’ expressions of difficulties should not always be taken as expectations for the instructor to solve the problems—or answer questions—for them. Fighting the urge to help and letting students struggle to find good solutions is truly at the heart of this pedagogy. The better the initial prob- lem statement is designed by the instructor, the more opportu- nities there are to turn the students’ questions back to them. When a student asks, “Can we ···?” It is entirely acceptable to reply, “I don’t know. Can you?” This gives “permission” for students to make the decision. Setting aside the lecture format, and thus a great deal of con- trol over the course content, is one of the most frequently cited difficulties for instructors using this pedagogy (e.g., Pepper, 2008). Designing a specific structure for class meetings can help reduce this anxiety. For example, setting benchmark dates for students to make decisions about aspects of their project helps give students a focus for each block of class time, while reassuring the instructor that progress was made during that class session. Another implementation element is the re-allocation of time and the change in the instructor’s role in a PBL model. In our example, we used a “standard” course design for the first two-thirds of the course. For the last month of the course, the instructor role shifted to that of facilitator. Reminding students of potential resources in the community and asking questions that prompted students’ own critical thinking became the new instructor roles. Gradually incorporating PBL into the course aided both instructor and students to adapt to the differing roles required of traditional vs. PBL pedagogy. An initial positive experience with using PBL in one segment of the course can give an instructor the confidence to use this approach in the future as the primary method of instruction for the entire course. There are several areas that future instructors might consider implementing to improve the experience for instructor and stu- dent. First, projects can be enhanced when an authentic audi- ence assists in actually evaluating project outcomes. Being given advanced notice and a student assessment form would allow the stakeholders to give feedback rather than just observe; the students can benefit from this type of feedback from people working in their future career fields. In addition, feedback from stakeholders can help the instructor determine if their grading of the students’ efforts is too harsh or too lenient in comparison to industry standards. Finally, allowing the students to self-evaluate their whole group final product (rather than just the efforts of their working group) affords them the opportunity to assess what went well, and identify areas they might choose to do differently. Incorporating any or all of these suggestions should be beneficial to both students and instructors attempting this pedagogy for the first time. Acknowledgements The authors wish to acknowledge the help of Jeffrey Wentz and Chris McQuiggan in implementing this pedagogy in the classroom. Thanks also to Barbara K. Fowler and Andrea A. Zevenbergen for helpful comments on an earlier version of this work. REFERENCES Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences (2005). Certification standards for college/university criminal justice baccalaureate degree programs. URL (last checked 10 October 2012). http://www.acjs.org/pubs/uploads/ACJSCertificationStandards-Bacc alaureate.pdf Barron, B. J. S., Schwartz, D. L., Vye, N. J., Moore, A., Petrosino, A., Zech, L., & Bransford, J. D. (1998). Doing with understanding: Les- sons from research on problem- and project-based learning. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7, 271-311. Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M., & Palinscar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sus- taining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington DC: Na- tional Academy Press. Brown, A. L., Bransford, J. D., Ferrara, R., & Campione, J. (1983). Learning, remembering and understanding. In J. H. Flavell, & E. M. Markman (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Cognitive development (4th ed., pp. 77-166). New York: Wiley. Burke, K. (2011). From standards to rubrics in six steps: Tools for student learning (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Crack, A. M. (2007). Undergraduate group projects: Student experi- ences of collaboration and self-assessment. International Journal of Learning, 14, 163-169. Davidson, W. S., Petersen, J., Hankins, S., & Winslow, M. (2010). Engaged research in a university setting: Results and reflections on three decades of a partnership to improve juvenile justice. Journal of Higher Education Outreach a nd Engagement, 14, 47-67. Falchikov, N. (2004). Involving students in assessment. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 3, 102-108. doi:10.2304/plat.2003.3.2.102 Gezie, A., Khaja, K., Chang, V., Adamek, M. E., & Johnsen, M. (2012). Rubrics as a tool for learning and assessment: What do baccalaureate students think? Journa l of Teaching in Social Work, 32, 421-437. doi:10.1080/08841233.2012.705240 Grant, M. M. (2002). Getting a grip on project-based learning: Theory, cases and recommendations. Meridian: A Middle School Computer Technologies Journal, 5, 1-17. Green, R., & Bowser, M. (2006). Observations from the field: Sharing a literature review rubric. Journal of Library Administration, 45, 185- 202. doi:10.1300/J111v45n01_10 Harvey, L. K., & Mitchell, A. D. (2006). Beyond the criminal arena: The justice studies program at Winston-Salem State University. Journal of Higher Educati o n O utr ea ch and Engagement, 11, 41-52. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 67  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. Holmes, L. E., & Smith, L. J. (2003). Student evaluations of faculty grading methods. Journal of Education for Business, 78, 318-323. doi:10.1080/08832320309598620 Jones, B. F., Rasmussen, C. M., & Moffitt, M. C. (1997). Real-life problem solving: A collaborative approach to interdisciplinary learning. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10266-000 Kenny, M. E., Simon, L. K., Kiley-Brabeck, K., & Lerner, R. M. (2002). Learning to serve: Promoting civil society through service learning. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Kezar, A., & Rhoads, R. (2001). The dynamic tensions of service learning in higher education: A philosophical perspective. The Jour- nal of Higher Education, 72, 148-171. doi:10.2307/2649320 Khabiri, M., Sabbaghan, S., & Sabbaghan, S. (2011). The relationship between peer assessment and the cognition hypothesis. English Lan- guage Teaching, 4, 214-223. Kretchmar, M. D. (2001). Service learning in a general psychology class: Description, preliminary evaluation, and recommendations. Teaching of Psychology, 28, 5-10. doi:10.1207/S15328023TOP2801_02 Li, L. Y. (2001). Some refinements on peer assessment of group pro- jects. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 26, 5-18. doi:10.1080/0260293002002255 Marx, R. W., Blumenfeld, P. C., Krajcik, J. S., & Soloway, E. (1997). Enacting project-based science. The Elementary School Journal, 97, 341-358. doi:10.1086/461870 Murray, J., & Summerlee, A. (2007). The impact of problem-based learning in an interdisciplinary first-year program on student learning behaviour. Canadian Journal of Higher Edu cati on, 37, 87-107. Myers, S. A. (2012). Students’ perceptions of classroom group work as a function of group member selection. Communication Teacher, 26, 50-64. doi:10.1080/17404622.2011.625368 Pepper, C. (2008). Implementing problem-based learning in a science faculty. Issues in Educational Research, 18 , 60-72. Papadopoulos, P. M., Lagkas, T. D., & Demetriadis, S. N. (2012). How to improve the peer review method: Free-selection vs assigned-pair protocol evaluated in computer networking course. Computers & Education, 59, 182-195. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.005 Quinlan, A. M. (2011). A complete guide to rubrics: Assessment made easy for teachers of K-College (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35, 435- 448. doi:10.1080/02602930902862859 Reitmeier, C. A., Svendsen, L. K., & Vrchota, D. A. (2004). Improving oral communication skills of students in food science courses. Jour- nal of Food Science Educati on, 3, 15-20. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4329.2004.tb00036.x Saito, H., & Fujita, T. (2009). Peer-assessing peers’ contribution to EFL group presentations. RELC Journal: A Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 40, 149-171. Scott, E., Van der Merwe, N., & Smith, D. (2005). Peer assessment: A complementary instrument to recognise individual contributions in IS student group projects. The Electronic Journal of Information Sys- tems Evaluation, 8, 61-70. Thomas, J. W., Mergendoller, J. R., & Michaelson, A. (1999). Pro- ject-based learning: A handbook for middle and high school teachers. Novato, CA: The Buck Institute for Education. Topping, K. J. (1998). Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities. Review of Educational Research, 68, 249-276. doi:10.2307/1170598 Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory into Practice, 48, 20-27. doi:10.1080/00405840802577569 Woolfolk, A. (2010). Educational psychology (11th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Yining, C., & Hao, L. (2004). Students’ perceptions of peer evaluation: An expectancy perspective. Journal of Education for Business, 79, 275-282. doi:10.3200/JOEB.79.5.275-282 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 68  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. Appendix A Project Component: _______________________________________________ Honor Pledge: To the best of my recollection and ability, the ratings I give below accurately reflect my performance and the per- formance of my peers. My Name: ____________________________ Signature: ______________________________________ My Grade (circle one in each category): Quality of Work: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Team Membership: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Communications: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F OVERALL: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Comments: (Print legibly, or type your comments on a separate sheet) Project Partner: ________________________________________ Partner’s Grade (circle one in each category): Quality of Work: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Team Membership: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Communications: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F OVERALL: A A− B+ B B− C+ C C− D F Comments: (Print legibly, or type your comments on a separate sheet) Appendix B Grading rubric for final presentation Rating ExceptionalAdequateMarginal Unacceptable Skill 4 3 2 1 NA Individual Student Dimensions Verbal skills Speaks clearly with natural variations in enunciation, volume, speed, and pitch. 4 3 2 1 NA Uses professional and exact language that is intentional and appropriate for the audience.4 3 2 1 NA Nonverbal skills Maintains natural eye contact with audience. 4 3 2 1 NA Utilizes any notes as a cue and does not read. 4 3 2 1 NA Dresses and grooms professionally. 4 3 2 1 NA Moves naturally with a comfortable posture. 4 3 2 1 NA Whole Group Dimensions Content Engages the audience with interesting information. 4 3 2 1 NA Matches content to the audience. 4 3 2 1 NA Demonstrates preparation through accurate content, knowledge of content, and ability to answer questions. 4 3 2 1 NA Fulfills goals of the assignment (multiple services, potential sources of funding). 4 3 2 1 NA Structure Provides an introduction that gains attention, and previews the main points. 4 3 2 1 NA Presents information in a logical order w/distribution of content split among members 4 3 2 1 NA Provides transitions between speakers w/in group 4 3 2 1 NA Provides a conclusion that signals the end of the speech, summarizes key points, and provides a good transition to the next group. 4 3 2 1 NA Visual aids Creates visual aids that are clearly visible to all audience members. 4 3 2 1 NA Connects visual aids to speech content. 4 3 2 1 NA Creates uniform, professional-looking visual aids. 4 3 2 1 NA Creates visual aids that contribute to the content of the speech but are not distracting in appearance or in the amount of material presented. 4 3 2 1 NA Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 69  D. V. MCMAY ET AL. Appendix C Group Project Self Assessment/Peer Review Rubric In nearly all professional jobs you will have regular reviews with your boss. You will also need to provide reviews of those on your team and those you supervise. Performance reviews of your peers can be really hard to do, but it is a necessary part of professional work. We are asking you to do a review for yourself and your pro- ject partners. The letter grades you give to yourself and your project partners will be confidential. Peer reviews will consti- tute 30% of your final grade. Self-assessment will constitute 15% of your final grade. Letter Grade Guidelines You can decide how to rate yourself and your team members on a letter grade scale in the following three areas. Here is a detailed rubric for you to consider as you assess your peers: Quality of W o rk A: Does exceptional work consistently and reliably. Exceeds expectations. A−/B+: Does very good work; did what was promised. B: Work and progress on the project was good, but “nothing to write home about.” B−/C+: Work and accomplishment lagged what was needed. C/C−: Just did the minimum to get by; work was of marginal quality. D: Has done only minimal work or very poor quality work. F: Has basically dropped out from the project and is not con- tributing in any way. Team Membership A: Has been an integral and important team member; has made significant contributions to the overall oral and written report; attends and participates in all team meetings. A−/B+: Is a helpful team member; contributes time and effort to solving problems; participates in team meetings. B: Effective worker; team interaction is adequate. B−/C+: Satisfactory but sporadic team interaction; not very effective in team results. C/C−: Does not contribute effectively to the overall team ef- fort; needs frequent prodding. D: Works with little or no interaction with the team; could have done without this partner. F: Has basically dropped out from the project and is not con- tributing in any way. Communications A: Writes and prepares documents/their part of slide show exceptionally well; exceptional communication skills. A−/B+: Writes very well; has good documentation skills; communicates effectively with team. B: Writing and communication skills are adequate. B−/C+: Written contribution is somewhat helpful; commu- nication skills need improvement. C/C−: Documentation and communication skills are below expectations. D: Produces no useful documentation of work finished; communication skills poor. F: Has basically dropped out from the project and is not con- tributing in any way. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 70

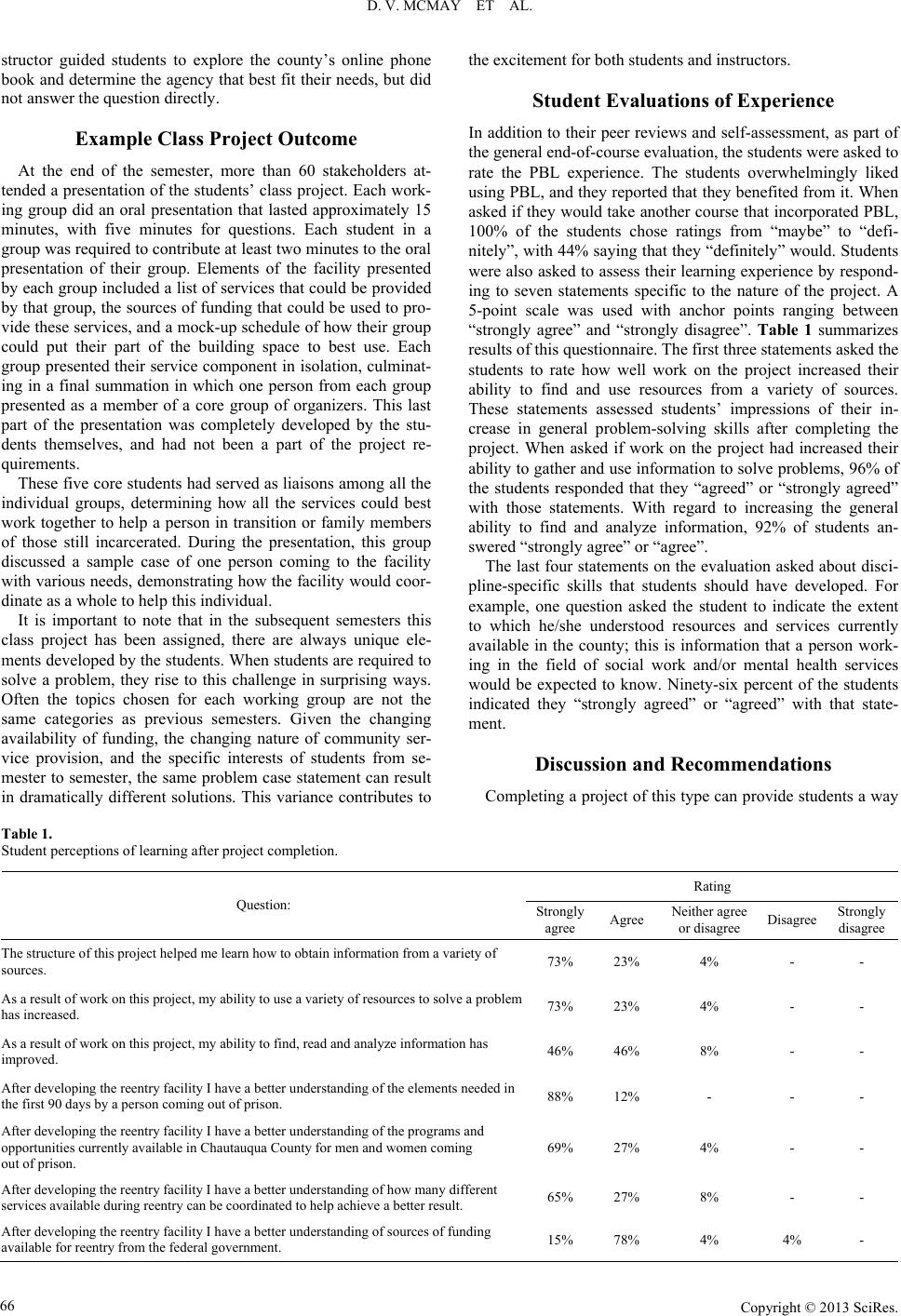

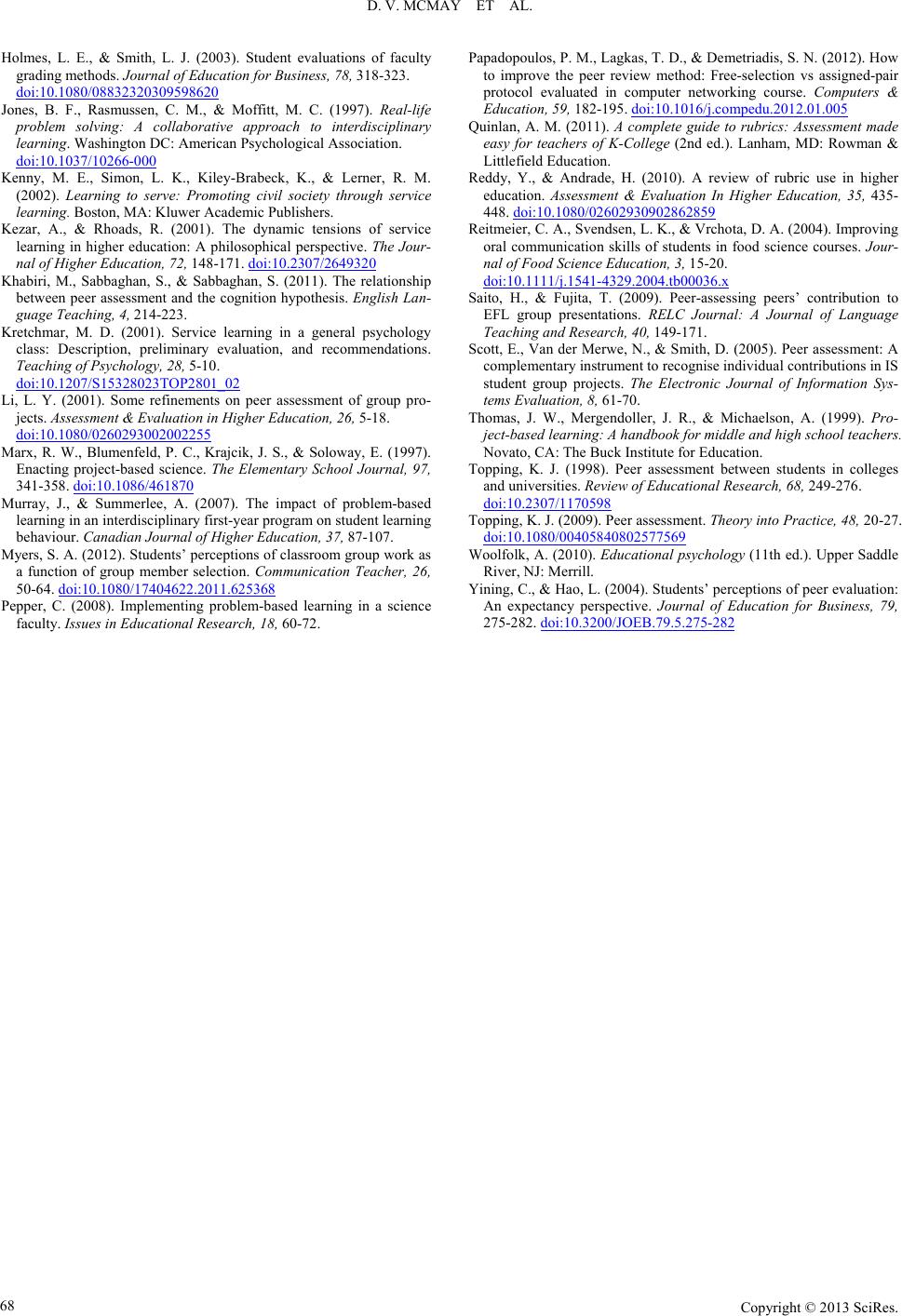

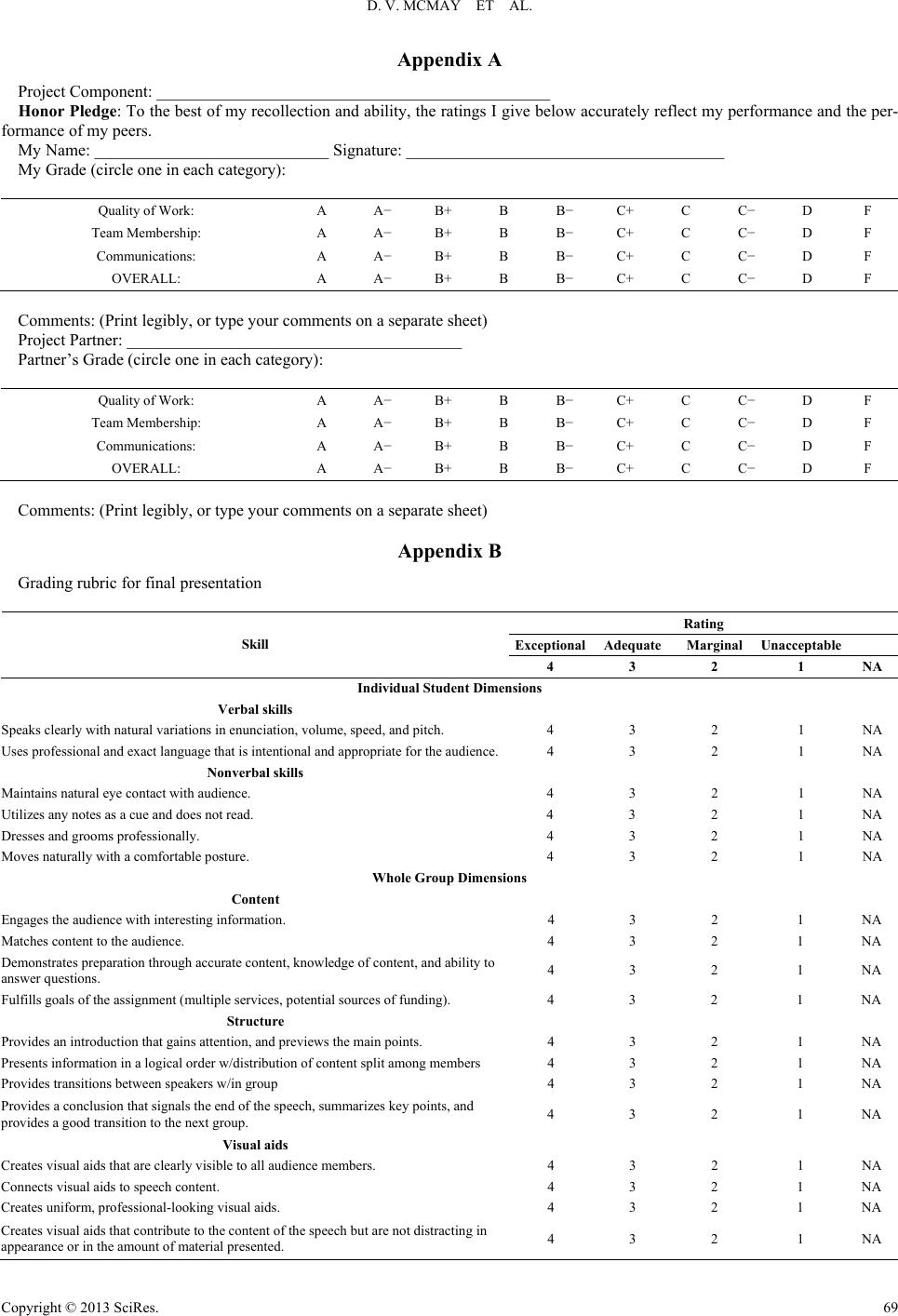

|