Sociology Mind 2013. Vol.3, No.1, 25-31 Published Online January 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2013.31005 Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 25 Family, Poverty and Inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean Cristina Gomes Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, Mexico City, Mexico Email: cristinagomesmx@gmail.mx Received September 13th, 2012; revised October 20th, 2012; acce p t e d N o vember 3rd, 2012 This article adopts the concept of development as freedom and the relationship between income and capa- bilities to analyze and compare macroeconomic, demographic and poverty trends and inequalities in Latin American and the Caribbean countries, and the responses from governments to promote the inclusion of the poorest and marginalized population groups in development and policies. Differences in population structures indicate that poverty and gender, generational and race inequalities fragment societies. Policies oriented to reduce poverty have been implemented with a set of combined programs such as cash transfers articulated with actions in nutrition, health, education, day-care programs for poor children, civil registra- tion and other programs to promote poverty reduction and the conciliation of domestic and work life for poor women and social protection. Some good practices are discussed, particularly in Brazil and Mexico. During the last 15 years, the Conditioned Cash Transfers programs raised public support and political consensus, guaranteeing continuity in their implementation, development and integration with other social protection programs. Currently there are 18 countries implementing such programs, covering approxi- mately 25 million households and over 133 million people, representing 19% of the Latin American and Caribbean. Policies to reduce poverty, in combination with income distribution and social protection in nutrition, health, education, civil registration and day-care for children, have contributed to human devel- opment, and also promoted internal market of consumers, even in rural areas, mobilizing local economies and promoting the return of investments to development. Despite the economic crisis in 2008-2009, Latin America had a relatively good performance in the world economy, demonstrating that social and eco- nomic inclusion can be compatible with development. That positive balance is fundamental to guarantee the inclusion of rural, indigenous, women and youth in access to services, as well as to reducing poverty and inequalities in the region. Keywords: Poverty; Inequalities; Policies; Latin America and the Caribbean Introduction Amartya Sen (1999) defines development as liberty and pov- erty as capability deprivation, since a low level of income af- fects people’s capabilities in education, health, survival, work, and other rights. Moreover, poverty is a lack of income, but is also a lack of capabilities, since an adequate income level is not the only generator of capacities. Social justice implies eradicat- ing poverty promoting capabilities and liberty to make decisions. And the relationship between income and capabilities varies among families and individuals. There are personal differences in age, sex, race-ethnic characteristics, health, disability, illness, that shape a diversity of capacities and needs to be taken into account by policies: children, youth, adults and elderly, men and women have specific capacities and needs. Moreover, these differences may be coupled at individual, family and commu- nity levels. Individuals and families live in a diverse environment, which varies in climate, level of drought, flooding and heating needs, related to infectious diseases and specific risks by areas of residence, urban or rural. Social inequalities generate differences in income and also in quality of life, access to public services, prevalence of crime and violence, pollution and community, relationships and per- spectives, patterns of behavior, conventions and customs. For example, relatively poor individuals live with less poor groups, and although they are not below the official poverty line, par- ticularly teenagers change behaviors and some take risks to achieve the same consumer level of their pairs and friends. Population heterogeneity is related to inequalities in income and capabilities, with individual, family social and environment differences. The level and distribution of resources and respon- sibilities in family reproduces the expected male and female roles. Maternity is related to family care and domestic obliga- tions for women, shaping different levels of wellbeing and freedom for men and women of different ages, and according to poverty condition. As a result, poor girls use to receive less food and care, and attend school less the school than boys, los- ing the opportunity to develop their higher potential and capaci- ties in the future, and reproducing poverty inter-generations (Lloyd & Blanc, 1996; Fathalla, 1997). Women, indigenous and afro-descendants have a lower level of nutrition, health and education. These groups accumulate discriminating characteristics and are less likely to enter into the labor market, to receive equal wages and to work in more skilled and productive positions, compared to their counterparts (Gomes, 2007). Poor populations have a lower life expectancy and will have more difficulties to convert their income into new capacities, even if they receive an additional income from cash transfer programs to poverty reduction.  C. GOMES Poverty of capabilities can be more intense than poverty of income, but both are always linked, since income is a mean to obtain skills, and once a person has more skills, he/she can increase family income (Sen, 1999). Policies to promote universal wellbeing may recognize and take into account these diversities and inequalities that affect individual capacities and family income, to integrate compo- nents from diverse spheres involved in poverty reproduction. The Human Development Index is a synthetic indicator that integrates three dimensions of poverty as capability deprivation: low per-capita income, illiteracy and low level of education and health, measured as survival, adapting Amartya Sen’s approach. This indicator has been very useful in comparing poverty and human development among and inside countries, providing relevant information to orient integrated policies and to imple- ment Poverty Reduction Programs. Macroeconomic Policies, Population Trends and Inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean The 1980’s development in Latin America and the Caribbean started a large period of crisis that continued during the 1990s. The combination of restrictive policies and economic crises contributed to increase poverty, which achieved high levels and began to decrease slightly only in the early 2000s. The rise and persistence of poverty in the 1990s and early 2000s had a nega- tive effect on economic growth and human development. It is estimated that if poverty increases by 10 percent it causes a de- crease of 1 percent in annual growth. In turn, if the GDP grew by 1%, poverty level would diminish by 1.25% in Latin Amer- ica (World Bank, 2006). Between 1950 and 2000 life expectancy increased from 45 to 70 years, and between 1960 to 1990 fertility rates were reduced to a half, from 6 to 3 children per woman in average. The rapid demographic transition impacted national and family economy and structure, the labor market, policies and societies (Gomes, 2001). From 1970 to 2000 the ratio of producers to dependents contributed to raise the annual rate of growth of output per effective consumer by about 0.5 to 0.6 percentage points annu- ally. This period of demographic dividend was similar in Asia and Latin America. In Asia it contributed to an increase in capi- tal accumulation, since families place a high value on education expenditures for children. In Latin America, the first two dec- ades of demographic bonus-1980 to 2000-coincided with re- current crisis and macro-economic adjustment, without the ne- cessary investments in schooling and employment generation. Policies that make it easier for young parents to study and work were insufficient for the growing young and adult population. Therefore, the potential contribution of demographic dividend for economic growth was not completely realized. Latin Ameri- can and the Caribbean countries did not take enough advantage of the demographic dividend in the two first decades of this potential bonus, as Asian countries did. (Bloom et al., 2003; Lee & Manson, 2003). Mortality and Fertility Rates Are Higher among the Poor, Indige nous and Af ri can Descend ants at All Ages, and Shape Different Population Pyramids within and am ong Countrie s Mortality and fertility rates are higher among the poor, in- digenous and African descendants of all ages. These groups have a lower life expectancy, are younger and have more chil- dren than their counterparts—the most advantaged groups, who live longer, control their fertility and have less dependent chil- dren. The population pyramids reflect different structures of age by sex, since the poorest populations have a large base of children and adolescents, while the richest have an aging popu- lation structure, a pattern reproduced in several countries, for example, Mexico, Argentina and Brazil. The groups between the poorest and richest, such as moderately poor and mul- lato-mestizo (mixed-race individuals) are in an intermediate position in the demographic transition. As a result, these indi- vidual and social inequalities produce different populations inside and within countries and outline specific demographic pyramids for different social groups (Figures 1 and 2). Moreover, demographic transition and changes in population structure also impact family structure and composition. In Bra- zil and Mexico, during the period 1910-2000, cohorts of male and female adults increased life expectancy and mostly contin- ued living in marriage during all their life, until the death of one of the partners. At the same time, increases in life expectancy and differentials in gender mortality promoted the higher wo- men survival, high proportions of female widows and of elderly women heading one-person and one-parental house-holds (Go- mes, 2001). Poverty Trends in Latin America and the Caribbean Considering poverty of income, the proportion of population living with one dollar per day in LAC region decreased from 22.6% in 1990 to 12.3% in 2010 (70 million). In this article, Latin American and the Caribbean countries are contrasted to the BRIC group (Brazil, Russia, India and China). Poverty line in dollars and adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP) is the best comparative indicator. However, the national poverty line, defined politically by each government, is presented and ana- lyzed also, as an indicator of the aspirations of each society and its governments. According to UNDP (2011), Uruguay, Jamaica, Costa Rica, Chile and Argentina have less than 1% of the population living with less than one dollar and half per day and a higher GNI per capita and adopt conservative national poverty lines, compared to the other countries in the region, as well as a similar pattern to Russia. Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, Dominican Republic, Para- guay, El Salvador, Peru and Panama have from 3.4% to 9.5% of their population living with less than one dollar per day, and middle GNI per capita, and most of them adopt a higher na- tional poverty line, compared to the richest group of countries (Figure 3). The highest proportions of poverty are found in Bolivia (14.0%) Nicaragua (15.8%), Colombia (16.0%). Al- though Colombia has a proportion of poverty and a GNI per capita similar to China, the national poverty line adopted by China government is more than ten times lower than the line adopted by the government of Colombia, characterizing much more ambitious goals of governments and higher aspirations of the population in the region. The group with higher proportions of poverty includes Guatemala (16.9%), Honduras (23.3%), São Tomé and Príncipe (28.6%) and Haiti (54.9%), the last one surpassing India. This group has also a very low GNI per cap- ita and very high national poverty line (Figure 3). Poverty levels decreased in the region only after 2000, due to the substitution of liberal economic policies by anti-cyclic and Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 26  C. GOMES Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 27 Figure 1. Population pyramids by poverty condition Mexico and Argentina 2006. Figure 2. opulation pyramids by race Brazil 2010. P  C. GOMES Figure 3. Poverty line of $1.25 dollars a day, national poverty line and GNI per capita, Latin American countries compared to BRICs countries. Source: UNDP (2011). social policies in the majority of the countries, which allow the region to face adequately the crisis of 2008. According to Amartya Sen, income is an important compo- nent of well-being, however, there are other components, such as ed ucat ion , heal th a nd ge nd er equality that improve capacities and the potential to reinvest income for human development. To express this concept, the Human Development Index (HDI) combines income, years of education and life expectancy. UNDP estimate also the non-income HDI, which includes only the mean years of education and the life expectancy. In the figure (Figure 4) this non-income HDI is useful to in- dicate that in Latin America and the Caribbean, these compo- nents of human development are higher than 0.8, and have a relevant weight in the total HDI. Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, Mexico, Panama and some Caribbean countries have very similar levels of education and health than Italy, even higher than Russia. The main differences in the total HDI is related to the level of income per capita, which reduce substan- tially the HDI in Latin American countries, putting them in a Figure 4. Human development index and non-income human development index Latin America, BRICs countries and Ita ly. Source: UNDP 2011. major disadvantage, compared to more developed countries. The large majority of countries have a lower IDH but a similar nom-income IDH than Russia. But almost all Latin American and the Caribbean countries have a much higher IDH and nom-income IDH and non-income IDH than China, which is the case of Costa Rica, Venezuela, Jamaica, Peru, Ecuador, Bra- zil, Colombia, Dominican Republic and others. Suriname, El Salvador, Paraguay, Bolivi a and Guy ana h ave a similar non-income HDI to the previous groups, but a lower HDI including income, even a much higher non-income HDI, as the case of Bolivia; while Honduras, Nicaragua and Guate- mala are under 0.6 level of HDI, but a high level of non-income HDI, and both indexes are higher, compared to India. Finally, Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 28  C. GOMES only Haiti has a lower HDI and non-income HDI than India. Latin American and the Caribbean countries are ranked high- er than India, most of them on a pair with China, Brazil is in the middle and some are up to Russia, in level of Gross National Income per capita, in poverty reduction and HDI, but mainly in non-income components of HDI, education and life-expectan- cy. Poverty Reduction Programs in LAC Region Are Based in Conditioned Cash Transfers for Families Amartya Sen’s approach on poverty as deprivation of capaci- ties has been applied in the Human Development Index, a very useful measure to compare poverty and human development among and inside countries, providing relevant information to orient integrated policies and inter-sector actions. Programs of Conditioned Cash Transfers (CCT) adopt the same approach, providing a complementary income and making poor families co-responsible for increasin g access to basic health services for all the family members and children education and nutrition. Therefore, CCTs protect family income and con- sumption levels in the short term and also contribute to human development in the long term. During the last 15 years, CCT has reached an important cov- erage in LAC region, raising public support, political and in- ternational consensus. Currently there are 18 countries imple- menting such programs, covering approximately 25 million households and more than 133 million people, 19% of the Latin American and Caribbean population (Rawlings & Rubio, 2005; Handa & Davis, 2006; Lagard et al., 2007). The largest pro- gram, Bolsa Familia in Brazil, started in 1995. In 2002, it’s rep- resented 6.9 percent of the GDP, and in 2009 9.3 percent (Cas- tro & Modesto, 2010). Some principles and characteristics have been shared through South-South cooperation, and collaborated for the dissemina- tion of CCTs. The concept of poverty as human development integrates cash transfers with actions to improve access to nu- trition, health and education. The condition to continue receiv- ing cash transfers is the family co-responsibility in promoting capacities (health and education. The programs focus upon in poor families with children in school age and women are the recipent of cash transfers, since previous studies demonstrated that women are likely to invest in human development of the family members, particularly in children. And cash transfers provide more freedom and autonomy to poor people to decide about their needs and how to use the benefit, compared to pre- vious programs centered in food or stamps. CCTs have been positively evaluated in several countries, particularly achieving improvements in coverage in nutrition, education, health and poverty reduction, and additionally in strengthening local economies, citizen empowerment, social inclusion and cohesion (Rawlings & Rubio, 2005; Handa & Davis, 2006; Téllez & Gomes, 2006; Lagard et al., 2007; Cas- tro & Modesto, 2010). The main obstacle faced by the CCTs in Latin America is in es- tablishing synergies between the program and health and edu- cation systems and in guaranteeing service quality for poor beneficiaries. Structural problems of administration, transpar- ency and quality cannot be solved by CCTs themselves, be- cause these problems are under responsibility of other authori- ties and Ministries, which shape a very complex situation to resolve through inter-sector ne gotiations and agreements. Evaluation processes have indicated the relevance to improve not only the budget and coverage of these services, but mainly to increase the quality and results in education and health pro- vided for poor groups. In Mexico, the program Oportunidades has been evaluated since the beginning, 1997. A very important achievement is gender equality in basic school, since for more than ten years the girls received a higher value of benefits than boys. This procedure reverted the cultural trend to do not value girls’ edu- cation, which was predominant among poor and indigenous families. Another additional component is the meetings with mothers to promote practices of sexual and reproductive health and the obligation of all the members of the family to be exam- ined two times annually by a health agent, in order to prevent illnesses, particularly infections, that can affect children and school attendance and performance. This component has achie- ved also results in reducing maternal mortality among poor wo- men. Additionally, in Mexico, the component for poor elderly im- plemented since 2006 provides cash transfers and promotes health, increasing food consumption, particularly protein, access to medicines and other domestic basic assets, and empowerment of poor elderly in family and communities. Evaluations of CCTs have indicated other poverty dimensions to be integrated or complemented contribute to achieve dignity to poor people: land and housing property, infrastructure and access to water, electricity and gas, access to technology (communication) and employment are some examples. In Mexico a qualitative eva- luation demonstrated that poor elderly living in extremely high temperatures, in the border with the US, or in extremely low temperatures, in the mountains or in the forest in the centre and south of the country, cannot pay for electricity or combustible, for gas or water. Some of them live in regions where the tem- perature exceeds 40 degrees Celsius, but they do not have enough resources to pay for electricity, even if they receive the CCP, and even if they have refrigerators, fans or conditioned air donated by their children or found in the trash, but these equipments are always disconnected. Other elderly live in con- ditions of below 10 degrees Celsius, without water and hot bath, heaters, and have to carry wood and water from the fields, and prevent from having hygiene practices due to lack of infra- structure. The government ha s complemented the poverty reduc- tion program creating also exemptions for these groups do not have to pay elect r icity bills and gas (Téllez & Gomes, 2006). In Brazil, the program Bolsa Familia has no gender prefer- ence for girls, but for ethnic groups. The indigenous and afro- descendants have facilities to be selected, and to receive special civil registration to be included in the program, since a high proportion of them could not prove their existence as citizens, because they do not have a birth registration or an official ID. These documents have been provided progressively during ten years by the program, in collaboration with the Civil Regis- tration institutions. Indigenous people in the Amazon region and other groups such as quilombolas1 or rural population liv- ing in inaccessible areas receive the benefits through special transport, such as offices and banks operating in ships and other mobile means to facilitate access to isolated population groups. 1Quilombolas are groups formed by descendants of African slaves who over a century ago fled the plantations, as well as other poor and marginalized groups who escaped from rural and urban areas for different reasons and have lived isolated for decades, and some remain isolated until today. Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 29  C. GOMES Even in Amazonia rainforest the program increased the partici- pation of the indigenous and other peoples of the forest in civil and social rights, such as the right to vote and develop citizen- ship and mechanisms of participation. These procedures con- tributed to identify exclusion-errors of the program, and pro- vided solutions for the inclusion of some of the poorest groups. The national coverage of Bolsa Familia increased from 1.15 million of families in 2003 to 12.37 million in 2009. In the poorest region (North-East) the program covered 2.13 million of families in 2003 and increased to 6.2 million in 2009, repre- senting half of the total of families receiving the program (Cas- tro et al., 2010). The implementation of CCTs put in evidence that Civil Reg- istration and Identity services are indispensable in guaranteeing the recognition of the self-declaration of age and identity for in- digenous, quilombolas and other isolated groups, who could receive their birth certificate and IDs for the first time, to par- ticipate not only in CCT, but also by the State and policies. In Brazil, México, Peru, Honduras and other countries in LAC region there are examples of increasing the coverage of identity and citizenship among poorest groups, through the elimination of taxes to provide birth certificate and extension of free ser- vices to isolated groups (Téllez & Gomes, 2006; Castro & Mo- desto, 2010). In Mexico the recognition of the Baptism certificate for poor elderly who have never had a birth certificate, was relevant to in- creasing coverage, while Ci vil Registration is in expansion. Cur - rently several countries provide IDs for children and adoles- cents, in order to guarantee their inclusion in social programs. Moreover, in Mexico and Brazil the CCTs progra ms achieved positive unexpected results in mobilizing local markets in poor- est regions, since the cash transfers are reinvested as popular consumption at local level, which has been beneficial, particu- larly in periods of economic crisis (Castro & Modesto, 2010). Families with More Children Are Likely to Be Poor, and Poor Women Are Likely to Have Small Children Families with more children are likely to be poor, and the proportions of poor children are above the average and the proportions of poor for all the other age groups (Gomes, 2001, 2006). As poverty lines are estimated based on the family income or expenditure per capita, the higher number of members who are dependents, particularly children, determines the division of fa- mily income among more members, and as a result, the lower income per capita, below the poverty line. That is the main rea- son why the most effective policies to reduce poverty are ori- ented to families with small children. Fertility rate is higher among women with low education level, poor, indigenous and Afro-descendants, compared to their counterparts. Families with a higher number of small children and where women do not work have a higher proportion of poverty. Poor women (and many poor children) spend most time in domestic work and caring for small children. They do not have enough time to study and work outside the home to generate additional income to overcome poverty. The predominantly domestic role of poor women is related to the combination of gender and social inequalities: women, poor, indigenous and afro-descendants are more discriminated in the labor market. They have higher unemployment rates, receive lower wages and have more difficulty in entering in the most skilled positions and to access social security and protection, compared to their counterparts (Chant, 1999; Gomes, 2006). An important indicator of gender discrimination is the gender income gap between. In LAC countries this gap is negatively related to the size of GDP, due to gender wage gap lies in ine- quality of labor insertion and discrimination against women. The deeper gender gaps in Chile, Argentina, Mexico and Peru, do not correspond to the high GDP of these countries, compared to the rest of the region. In Haiti, Bolivia and Nica- ragua the gender gaps are considerably smaller than in the rich- est LAC countries, but it may simply reflect the homogeneity of low wages and poverty for men and women in poorest countries (UNDP, 2004). The gender wage gap is not explained only by education, but also by specific gender discrimination in the labor market. These inequalities are unacceptable, and they undermine social cohesion and efficiency, generating and reproducing conflicts and poverty. In these countries, additional years of education, work and income for women, combined with day care institu- tions for children would be crucial components for poverty re- duction. Moreover, female discrimination in the labor market and gender inequalities in wages may be relevant objectives in labor market policies and rules. In most of Latin American countries, particularly in the less developed, the majority of women do not work. Women with a higher level at education are more often working, planning their lives, have higher expectations of the future and have fewer children. At the other extreme, illiterate women and those with lower education level have more children, dedicate more time to domestic work and do not have social protection to reconcile domestic and work life, facing difficulties to enter in the labor market and to receive higher wages to contribute to their fami- lies budget an d escape poverty (Gomes, 2007). Discussion Although Latin America and the Caribbean countries achie- ved important increases in life expectancy and family planning, these improvements were unequal, with disadvantages for poor and ethnic women and youths, reproducing poverty in families with more children, making difficult to include poor mothers in the labor market to contribute to the family income, and creat- ing obstacles for poor women to reconcile domestic and work life. Differences in population structures indicate that poverty and gender, generational and race inequalities fragment socie- ties. Human development is related to the level of income per capita, but non-income plays an important role in Latin Ameri- can and the Caribbean countries, placing them at a much higher level than China and India. Life-expectancy and education are important components of human development in the region, where population analysis contributes to move the concept of poverty from lack of income to development as capacities and freedom, and to reorient policies to reduce poverty and ine- qualities, involving several spheres of economy and society. Countries where the State has assumed a pro-activism con- ducting not only the macro-economic stability, but also the abandonment of the paradigm of minimal state, investing in de- creasing poverty and inequalities and in the inclusion of his- torically marginalized groups, it is possible to reorient policies and budgets to promote economic sustainable development Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 30  C. GOMES Copyright © 2013 SciRes. 31 with income distribution. To expand social policies, as well employment generation, formal jobs, inclusion in social secu- rity and social protection programs and child-care to promote poor women to study and work, are some mechanisms adopted to promote citizenship, achieving combined positive effects to reduce poverty and inequalities. Considering that all citizens are subjects of rights, the chal- lenge for the CCT programs is to create real possibilities for inclusion of the poor and vulnerable in society, establishing guarantees for their empowerment and inclusion respecting the principles and content of the rights approach. The incorporation of human development and rights ap- proaches to programs has allowed governments to identify op- portunities for achieving higher levels of policy responses and results from an integral perspective. The CCT programs are initiatives aimed to combating the structural poverty. These programs have achieved results in en- couraging access to nutrition, basic health services and edu- cation for poor families, contributing to building capacities and to promote equality for more than ten years of implementation. Moreover, the programs protect certain levels of consumption in the short term, strengthening the family income through the resources transferred, and have mobilized and strengthened local markets, particularly in rural areas and periphery areas of the cities. A commitment of the State to inclusive social policies and programs, designed with a focus on rights and development as freedom and capabilities, social inclusion and citizen empo- werment contributes decisively to decrease poverty, hunger and inequalities. At the same time, decentralization and empowerment of local governments facilitates the protection of vulnerable groups, who depend mainly of the efficiency of national policies and budget distribution. The federative role to promote cooperation among federal, states and municipal governments, as well as citizen- ship participation are indispensable to overcome the obstacles in access and quality of services provision. The main challenge for the countries in the region is to create also legal mecha- nisms to encourage collaboration among different levels of government, and to guarantee responsibilities and fiscal instru- ments to involve all levels of government with specific respon- sibilities to implement sector policies. The combination of policies: rural and urban pensions or cash transfers for poor and informal workers, access to educa- tion and health system, unemployment benefit, conditioned cash transfer and decentralization, have converged with distri- bution effects, particularly including the poorest in the marked. Conclusion Latin American countries have applied different sets of com- bined social policies, and exchange of experiences through South-South cooperation have contributed to protect economies and populations in the region from the effects of economic crises. CCTs should be analyzed considering the context in which these policies are applied, and their integration with other pro- grams. Although CCTs is only one possible tool share to over- come poverty, they do not constitute the center, or the complete social policy. As the State is responsible to guarantee human development and rights in a general policy context, a combina- tion of specific programs may contribute directly or indirectly to the realization of rights. In the specific case of CCTs, their impacts would present increases in access to social services and household income, which can be considered mechanisms to promote human rights realization, especially in food, health, education, social protection and civil registration. Effective re- sults depend upon if they are designed in a context of dynamic articulation and integratio n with other social policies. Despite the economic crisis in 2008-2009, Latin America had a relatively good performance in the world economy, demon- strating that social and economic inclusion can be compatible with development. REFERENCES Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2003). The demographic dividend. A new perspective on the economic consequences of po- pulation change. Pittsburg, PA: Rand. Castro, J. A., & Modesto, L. (2010). Bolsa família 2003-2010: Avanços e desafios. Brasília, DF: Ipea. Chant, S. (1999). Informal sector activity in the third world city. In M. Pacione, (Ed.), Applied geography: An introduction to useful re- search in physical, environmental and human geography (pp. 509- 527). London: Routledge. Fathalla, M. F. (1997). Gender discrimination undermines right to health for girl child. Geneva: International Pediatric Association, In- ternational Child Health. Gomes, C. (2001). Demographic dynamics, family and institutions. A comparative study—Brazil and Mexico, with emphasis in the elderly situation. Ph.D. Thesis, Mexico City: El Colegio de México. Gomes, C. (2006). Households in moderate poverty in mexico: Profile and demographic interactions. In A. Venzor, C. Gomes, & G. Valenti, (Eds.), El Reto de la Informalidad y la Pobreza Moderada (pp. 147-184). Méxic o: Presidencia de la República: IBERGOP. Gomes, C. (2007). Transición demográfica en América Latina: Impacto y desafíos desde el trabajo y la reproducción. In J. Astelarra (Ed.), Género y Cohesión Social (pp. 53-62). Madrid: Fundación Carolina. Handa S., & Davis, B. (2006). The experience of conditional cash transfers in Latin America and the Caribbean. Development Policy Review, 24, 513-536. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00345.x Lagard, M., Haines, A., & Palmer, N. (2007). Conditional cash trans- fers for improving uptake of health interventions in low- and mid- dle-income countries: A systematic review. Journal of American Me- dical Association, 298, 190 0-1910. doi:10.1001/jama.298.16.1900 Lee, R., & Mason, A. (2003). What is the demographic dividend? Bekerly, CA: Bekerly University. Lloyd, C., & Blanc, A. (1996). Children schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa: The role of fathers, mothers and others. Population and De- velopment Review, 2, 265- 298. doi:10.2307/2137435 Rawlings, B., & Rubio, G. M. (2005). Evaluating the impact of condi- tional cash transfer programs: Lessons from Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press and The World B ank . Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Téllez, M. M., & Gomes, C. (2006). Diagnosis on welfare and life conditions of the beneficiaries of the elderly component of the pro- gram oportunidades. Mexico City: Insp-Sedesol. UNDP (2004). H uman development report 2004. New York: UNDP. World Bank (2006). World development report. Equity and develop- ment. Washington DC: The World Bank.

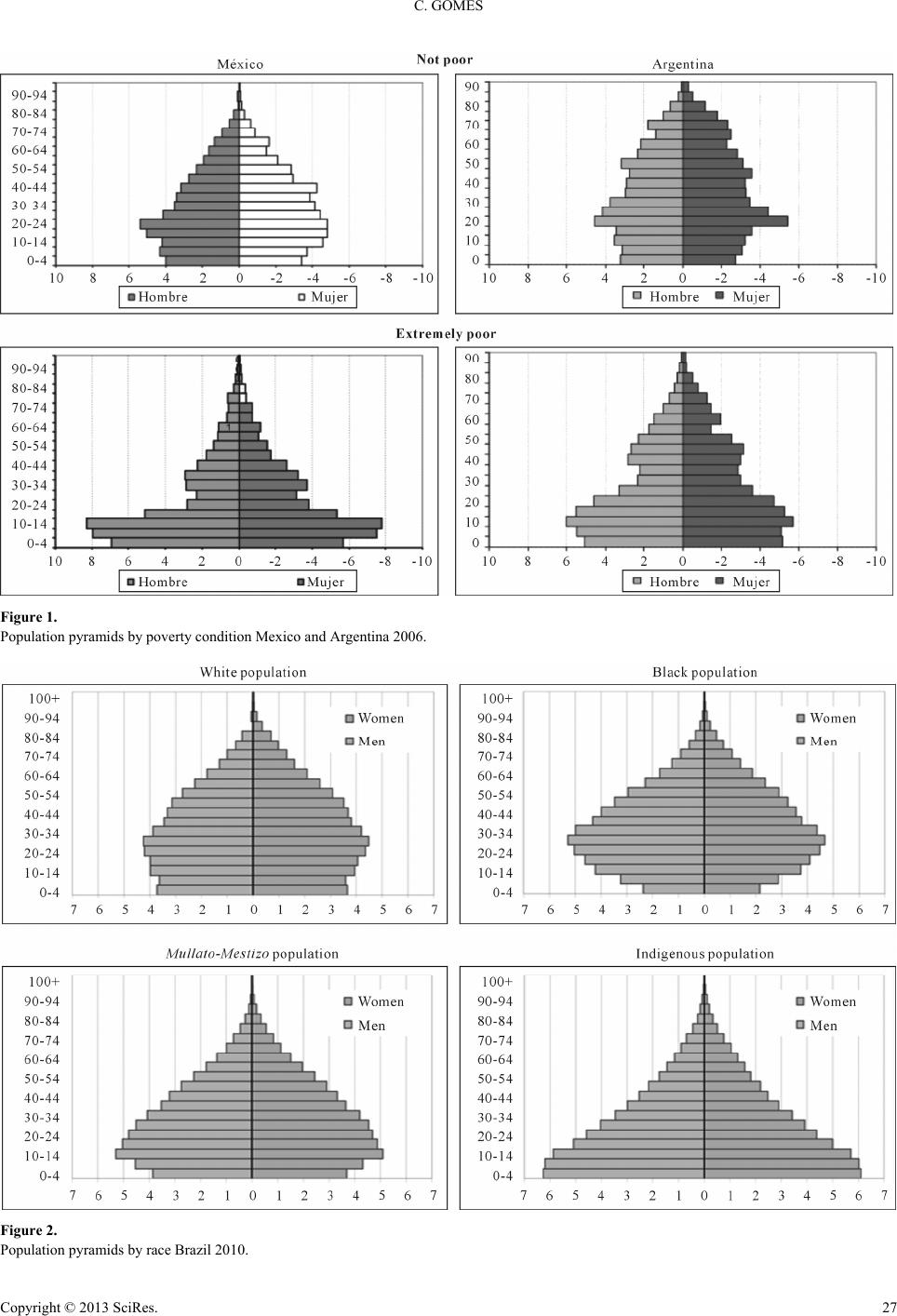

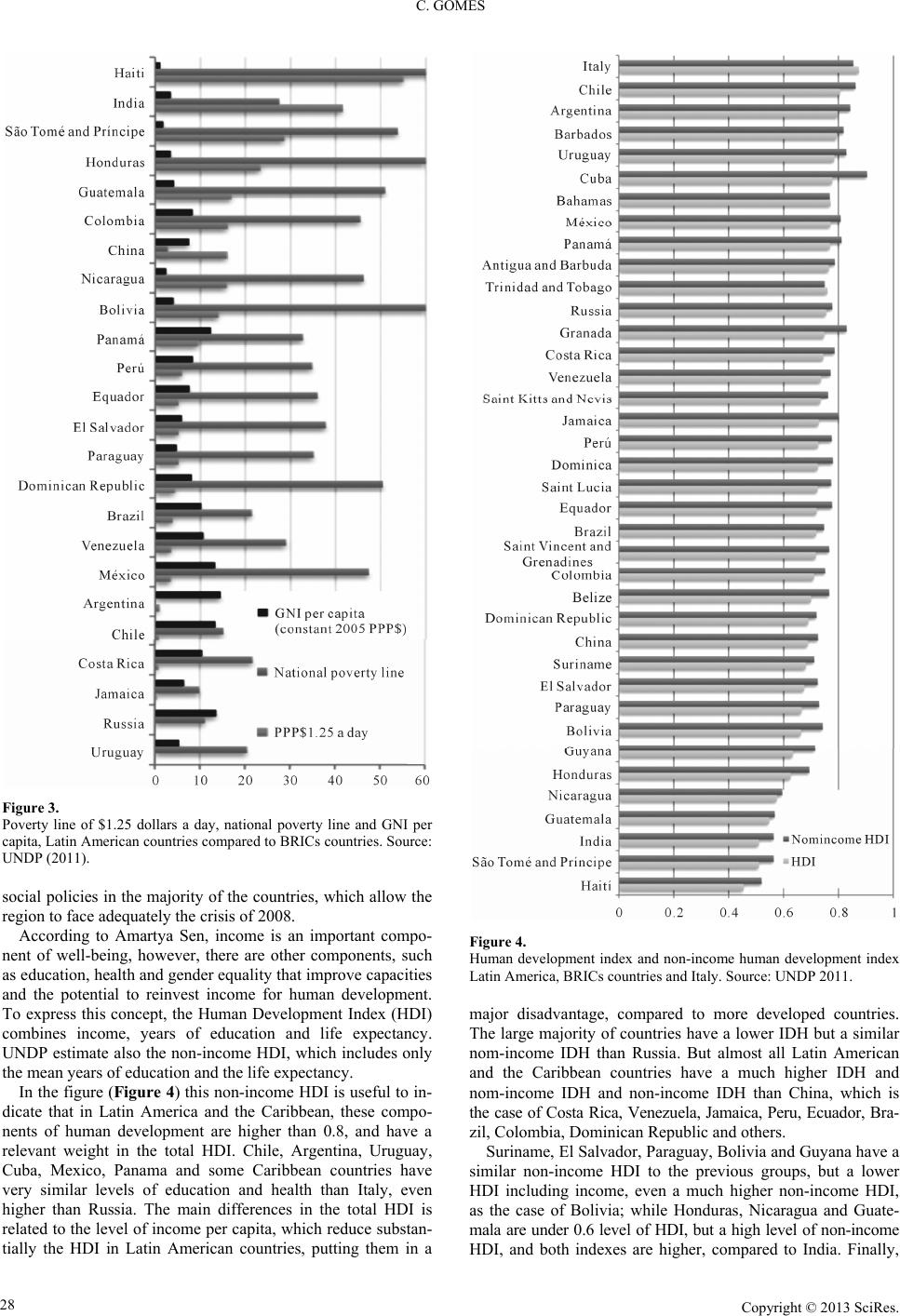

|