Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.12A, 1166-1173 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A172 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1166 Personality Fit and Positive Interventions: Extraverted and Introverted Individuals Benefit from Different Happiness Increasing Strategies Stephen M. Schueller1,2* 1Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA 2Positive Psychology Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA Email: sschuell@psych.upenn.edu Received July 19th, 2012; revised August 18th, 2012; accepted September 15th, 2012 The current investigation examined if introverts and extraverts benefit differentially from specific positive psychology interventions. Across two studies participants completed various interventions: three good things, gratitude visit, savoring, signature strength, and active-constructive responding. In study 1, each participant (N = 150) completed 1 of the 5 interventions over a one-week period. All 5 interventions led to increases in happiness, t(144) = 3.80, p < .001, and reductions in depressive symptoms t(144) = 5.20, p <.001. Neither exercise was more beneficial overall. The results of an ANCOVA (with baseline levels as a covariate) found that the interaction term for extraversion and condition was at a trend level F(4, 139) = 2.36, p = .056 and planned contrast analyses supported a pattern of person-activity fit. Extraverts bene- fited more from the gratitude visit and savoring exercises, whereas introverts benefited more from the ac- tive-constructive responding, signature strength, and three good things exercises. In study 2, participants (N = 85) were assigned to one of three groups: the gratitude visit performed either in-person, over the phone, or via mail. Participants completed each exercise over a one-week period. No differential efficacy was found for the 3 interventions, F(1, 74) = .056, p = .95. Results from Study 1 were replicated as the gratitude visit in person was more beneficial for extraverts than introverts, although these results were not significant, t(25) = 1.01, p = .32. Pooling the participants who completed the gratitude visit in person across the two studies into a single statistical test showed that the gratitude visit was more beneficial for extraverts than introverts t(55) = 2.03, p = .04, d = .55. These studies provide support for the notion that introverts and extroverts may benefit from pursuing different strategies to promote happiness. Keywords: Positive Psychology; Intervention; Matching; Personality; Extraversion Introduction Positive psychologists have created a range of strategies to increase happiness. These exercises deemed positive psychol- ogy interventions (PPIs) promote positive emotions, behaviors, and thinking to improve short-term and long-term individual well-being (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). PPIs target various pathways such as gratitude (Emmons & McCullough, 2003), optimistic thinking (Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, 2011), and savoring (Jose, Lim, & Bryant, 2012). In an initial qualitative review of the literature, Duckworth, Selig- man, and Steen (2005) suggested that over a hundred strategies have been proposed, although far fewer have been the subject of rigorous empirical evaluation. In a recent meta-analysis, 51 empirical studies of PPIs were identified which on average led to moderate increases in well-being (r = .29) and decreases in depressive symptoms (r = .31; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Despite evidence that demonstrates that PPIs are efficacious on average, it is unlikely that each intervention will work for every person. Indeed, several researchers have suggested an important area of research is to examine individual variation in response or “person-activity fit.” For example, in highlighting the importance of intentional activity’s contributions to long- term changes in happiness, Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade (2005) acknowledge that “any one activity will not help every- one become happier” (p. 121) and researchers have been en- couraged to consider “[is] there a personality type for whom some exercises ‘take’ and others do not?” (Seligman, Steen, Peterson, & Park, 2005: p. 420). Evaluating these questions re- quire investigating moderators of intervention efficacy. Initial Evidence Suggesting People Benefit from Different Positive Interventions One of the earliest empirical tests of PPIs was of an educa- tional classroom based program deemed the “14 Fundamentals” which contained a list of cognitive and behavioral recommend- dations (Fordyce, 1979, 1983). These recommendations in- cluded strategies such as be active, socialize, stop worrying, plan things out, think optimistically, and remain present-ori- ented. Participants benefited from the program overall yet par- ticipants did not typically engage in all 14 suggestions. Instead, participants focused on different strategies with no one strategy an overwhelming favorite. Indeed, in other applications of PPIs, when given various options people act in a similar way, honing in on a few favorite strategies. For example, an iPhone applica- tion of PPIs, Live Happy, disseminated through Apple’s online app store, contained 8 different PPIs (Parks, Della Porta, Pierce, *Now at the Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine.  S. M. SCHUELLER Zilca, & Lyubomirsky, 2012). An analysis of the usage patterns from 2928 users who purchased the application and used at least one strategy more than once revealed that the largest grouping of people used 3 exercises (18.2%) with by far the fewest individuals actually using all 8 (5.2%). In analyzing the preferences, the most favored strategy was goal tracking (30.63% of users practiced it the most) and savoring was the least popular (2.7% of users practiced it the most). Thus, quite a range existed in popularity of the PPIs. No one strategy was an overwhelming favorite and each strategy was the favored by some individuals. This suggests determining characteristics that might predict individual preferences and differential benefits is a valuable research endeavor. Previous Evidence for Personality Fit in Positive Interventions Several studies have examined personality characteristics as possible moderators of the benefits of PPIs. These studies have typically evaluated one or two interventions and investigated if a particular personality trait relates to differential intervention efficacy. This line of research is identified as investigating per- son-activity fit within PPIs as it tries to determine which PPI is the best “fit” for a given individual (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Lyubomirsky, 2005; Schueller, 2012). Empirical studies of person-activity fit have used interventions such as promoting self-compassion and optimism (Shapira & Mongrain, 2010), performing acts of compassion towards others (Mongrain, Chin, & Shapira, 2010), practicing gratitude or listening to uplifting music (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011), and reflecting on daily events (Giannopoulous & Vella-Brodrick, 2011). The personal- ity characteristics used to assess “fit” are as varied as the inter- ventions themselves including self-criticism (Shapira & Mon- grain, 2010; Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011), connectedness (Shapira & Mongrain, 2010), anxious attachment style (Mon- grain et al., 2010), and orientation towards happiness (Gian- nopoulous & Vella-Brodrick, 2011). A majority of these studies were conducted as part of a large- scale Internet-based project evaluating PPIs entitled “Project HOPE.” This project recruits participants from Internet ads that direct interested individuals to an online web portal. Findings from “Project HOPE” generally support the notion that per- son-activity fit can alter the benefits from PPIs; however, it is hard to synthesize research findings into general recommenda- tions for those practicing PPIs. One study found that individu- als high in connectedness received larger boosts in well-being than those low in connectedness when writing a letter to sooth and comfort oneself (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011). These re- searchers concluded that those high in connectedness were skilled at soothing others and thus could easily apply this skill to themselves. Findings from self-criticism were mixed, how- ever, with some evidence supporting that those high in self- criticism benefited more than those low in self-criticism from both self-compassion and optimism but these findings did not replicate across all analyses. Comparing gratitude and a music intervention, they predicted that gratitude would appeal to self-critics and that music would appeal to needy individuals (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011). Although the researchers found some support for the fit of the gratitude exercise for individuals high in self-criticism, as they experienced greater increases in happiness, self-esteem, and decreases in physical symptom severity, they did not find that the music condition was a good fit for individuals high in neediness. As another test of per- son-activity fit, they examined whether an anxious attachment style, as measured by a self-report questionnaire, predicted response to a PPI designed to increase compassionate actions (Mongrain et al., 2010). Indeed, people with an anxious at- tachment style reported a greater decrease in depressive symp- toms after completing the intervention than those who scored low on the measure of anxious attachment. Although, these results were not replicated in the analyses of the 6-month fol- low-up data, it provides some support that completing compass- sionate acts for others might be a useful strategy for those with an anxious attachment style. Within a PPI, instructions can be modified to be more con- sistent with personality, possibly increasing the “fit.” Gian- nopoulous and Vella-Brodrick (2011) modified a gratitude exercise and instead had participants reflect on experiences that related to different orientations to happiness (see Peterson, Park, & Seligman, 2005). Participants were randomly assigned to one of four groups, with each group reflecting on three events from the day that they found 1) pleasurable, 2) engaging, 3) mean- ingful, or 4) one event from each of the three categories. Well-being increased in all of the interventions with the largest boosts associated with the condition which reflected on an event in each category (pleasure, engagement, and meaning). Person-activity fit was partially supported, as an interaction emerged immediately post-intervention but not at a 2-week follow-up. The researchers found, however, that the best match- ing addressed participants’ deficits as those who were assigned to an intervention that was different from their dominant orient- tation received the largest increases in well-being. Overall, these studies support that person-activity fit is im- portant but also show the limitations of this line of research. First, using a small sample of interventions complicates inter- pretation of the findings. Unless interventions show clear dif- ferences across subgroups it is difficult to determine if the se- lected characteristic is a prescriptive variable (a variable that predicts differential benefit across interventions or speaks to “fit”) or a prognostic variable (a variable that indicates particu- lar good or poor outcomes for all interventions). As an example, neediness might indeed be a prognostic variable indicating poor response to PPIs as evidence suggests that individuals high in neediness were a poor fit for both gratitude and music interven- tions (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2011). Second, tests of modera- tion are often underpowered within a single study and therefore require either large samples or replication. Lastly, selecting personality characteristics that might predict fit is not straight- forward. Measuring multiple variables, however, can be prob- lematic for conducting statistical analyses as researchers need to conduct multiple tests with reduced statistical power or use advanced data mining and analytic techniques. The current studies address these limitations by using multiple PPIs and adopting a widely studied personality construct—extraversion. Current Investigation The current investigation addresses person-activity fit th- rough a series of studies examining extraversion as a mod- erator of the efficacy of various PPIs. In a first study, several PPIs are provided to participants to determine if extraversion is a reasonable personality characteristic to consider and which PPIs might be more beneficial for extraverts versus introverts. In a follow-up, a single PPI is modified in terms of mode of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1167  S. M. SCHUELLER delivery to examine if this alters the specific benefits for extra- verts and introverts. This investigation is merited as existing research supports the idea that person-activity fit is a worth- while consideration in selecting PPIs (see Lyubomirsky, 2008; Schueller, 2010) but more research is needed to provide spe- cific recommendations. These studies address that gap. This investigation used five PPIs all of which have received empirical support in previous studies: 3 good things (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Seligman et al., 2005), conducting a gratitude visit (Seligman et al., 2005), using your signature strengths (Seligman et al., 2005), savoring (Jose et al., 2012; Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006), and ac- tive-constructive-responding (Seligman et al., 2006, Gable, Reis, Impett, & Asher, 2004). In study 1, each participant re- ceived one of the five PPIs and completed it for a week period. In study 2, one PPI, the gratitude visit, was examined in further detail by providing a modification on the specific instructions to attempt to increase fit (i.e., Giannopoulous & Vella-Brodrick, 2011). In this modification, participants either completed the gratitude visit in person, over the phone, or via mail. Extraversion was selected a measure of person-activity fit because it is one of the most studied personality traits and there is theoretical support for the notion that introverts and extra- verts would benefit from different activities. Extraverts enjoy social interactions more than introverts (Emmons & Diener, 1986; Emmons, Diener, & Larsen, 1986) are more likely to live in areas that had easier access to social interaction (Murray et al., 2005), and are more highly motivated by social attention (Ashton, Lee, & Paunonen, 2002). It is predicted that extraverts and introverts will benefit from different PPIs. Specifically, extraverts will receive larger in- creases in well-being from PPIs with a social component and introverts will receive larger increases in well-being from PPIs without a social component. Study 1 Study 1 investigated extraversion as a moderator of 5 PPIs. The selected PPIs were 3 good things, active-constructive re- sponding, gratitude visit, using a signature strength, and savor- ing as these PPIs had been previously investigated in a group format (Seligman et al., 2006) and other Internet-based investi- gations of sequences of individual exercises (Schueller 2010; 2011). These exercises are described in detail elsewhere (Schueller, 2010). Of these PPIs, the gratitude visit and ac- tive-constructive responding have a social component thus pre- dicted to correspond to greater efficacy for extraverts and the 3 good things, strengths, and savoring exercises do not have a social component thus predicted to correspond to greater effi- cacy for introverts. Method Participants and Procedure The participants were 150 University of Pennsylvania under- graduate students participating for course credit for their psy- chology classes. The mean age of the participants was 18.81 (SD = 1.167). The sample was predominantly female (76% female, 24% male) and Caucasian (70%), whereas other ethnic groups were less represented (20% Asian, 3.3% Black, 1% Latino, 6% other). Participants first filled out dependent meas- ures and then received instructions for one randomly assigned PPI: 3 good things (n = 30), gratitude visit (n = 30), savoring (n = 29), using your signature strength in a new way (n = 30), and active-constructive responding (n = 31). Because the goal of this study was to look at person-activity fit no control group was used. Each day (with the exception of the gratitude visit which is done once during a week) for a week participants per- formed and wrote a brief summary of their assigned exercise on an online web diary. At the end of the one-week period partici- pants received a link to a follow-up questionnaire which con- tained dependent measures. Measures Brief Big Five Inventory (Brief BFI; Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, 2002). The Brief BFI is a 10-item measure of person- ality, with two items tapping each of the five factors. Partici- pants rated the extent to which each pair of adjectives refers to them using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). For the extraversion subscale the scale had a reliability of α = .78. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Lar- sen, & Griffin, 1985). The SWLS is a 5-item measure of gen- eral life satisfaction (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”, “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”). The participants rated themselves on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The responses to the five items were averaged, with higher scores representing higher levels of general life satisfaction. This scale had a reli- ability of α = .88 for the pretest and α = .91 for the posttest. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The PANAS consists of 20 adjec- tives, 10 related to positive affect (e.g., “interested,” “enthuse- astic,” “determined”) and 10 related to negative affect (e.g., “afraid,” “nervous,” “guilty”). Participants rate each adjective using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely) to represent the extent that the adjective de- scribed them. The positive affect subscale had an α = .89 for the pretest and α = .92 for the posttest. Whereas the negative affect subscale had an α = .85 for the pretest and α = .90 for the post- test. Authentic Happiness Inventory (AHI; Seligman et al., 2005). The AHI is a 24-item measure of general happiness. Each item consists of a series of 5 statements and participants indicated the statement that corresponded to how they felt at the time. An example is: A. I am unhappy with myself. (1) B. I am neither happy nor unhappy with myself—I am neu- tral. (2) C. I am happy with myself. (3) D. I am very happy with myself. (4) E. I could not be any happier with myself. (5) The AHI has been found to be less skewed than other meas- ures of happiness (Seligman et al., 2005). The AHI had an α = .94 for the pretest and α = .96 for the posttest. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item measure of indicated the amount of depressive symptoms the respondent has experi- enced over the past week. Participants rated how often they experienced each symptom ranging from rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) to most or all of the time (5 - 7 days). Sample items include “I felt depressed”, “I did not feel like eating; my appetite was poor” and “I thought my life had been a Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1168  S. M. SCHUELLER failure.” The CES-D had an α = .91 for the pretest and α = .91 for the posttest. Demographics: Age, ethnicity, and gender were recorded for each participant. Results Statistical Analyses In all analyses a person was classified as an introvert or ex- travert based on a median split of the data producing 67 intro- verts and 83 extraverts.1 The blessings condition had 14 intro- verts and 16 extraverts, the gratitude condition had 16 introverts and 14 extraverts, the savoring condition had 11 introverts and 18 extraverts, the strengths condition had 16 introverts and 14 extraverts, and the active-constructive condition had 10 intro- verts and 21 extraverts. Five participants did not complete fol- low-up measures and were thus excluded from the analysis for changes due to intervention. These participants, however, were retained for analyses of baseline differences. In order to better interpret intervention efficacy, an overall measure of well-being was created using a composite of dependent measures. Scores on each scale were transformed using z-scores and combined into a linear composite that gave equivalent balance to positive scales (AHI, SWLS, PA) and negative scales (CES-D, NA). The use of composite measures of well-being to determine overall benefit from PPIs is well-established and a composite of similar measures constructed this same way has been used by other researchers (e.g., Lyubomirsky, Tkach, & Sheldon, 2004) and mirrors Diener’s (1984) definition of subjective well-being being a multifaceted construct made up of cognitive and affec- tive aspects. Given the specific hypothesis for person-activity fit, planned contrast analyses were conducted to determine if the prediction correspond to differential efficacy of intervene- tions for introverts versus extraverts. Baseline Differences Introverts scored lower at baseline on all dependent measures including lower happiness, t(148) = 7.10, p < .001, life satisfac- tion, t(148) = 5.58, p < .001, and positive affect, t(148) = 1.83, p = .07, and higher negative affect, t(148) = 1.95, p = .05, and depressive symptoms, t(148) = 4.43, p < .001. These differ- ences are consistent with the common finding that extraversion is a strong predictor of well-being (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Thus for subsequent analysis we controlled for initial levels of well-being and extraversion. Changes in Well-Being Overall the interventions led to increases in happiness, t(144) = 3.80, p < .001, and reductions in depressive symptoms, t(144) = 5.20, p <.001. ANCOVA was used to assess overall interven- tion effect and examined extraversion as a moderator. A model was tested using overall well-being at baseline as a covariate, and condition, extraversion, and the condition by extraversion interaction as predictors of post-intervention well-being. There was no main effect of intervention, F(4, 139) = .32, p = .86, as all strategies seemed to be just as effective at improving well-being. Additionally, there was no main effect of extravert- sion, F(1, 139) = .10, p = .75. The interaction term of extravert- sion by condition F(4, 139) = 2.36, p = .056 did not reach sig- nificance, although was at a trend level. Given a specific prior hypothesis as to which interventions would be a better fit for extraverts and introverts, planned contrast analyses were con- ducted with the following weights (gratitude visit: λ = .5, ac- tive-constructive responding: λ = .5, savoring: λ = –.33, strengths: λ = –.33, three good things: λ = –.33) with positive values suggesting that extraverts would benefit more than in- troverts. This planned contrast was significant, t(140) = 2.21, p = .03, suggesting that this hypothesized pattern fit the data well, ralerting = .60. In order to further investigate the nature of the interaction between extraversion and exercise, each exercise was looked at separately for introverts and extraverts. This is warranted given the trend level finding of the moderator variable and the highly significant contrast test. Given the relatively small sample sizes within each intervention, these effects failed to reach signifi- cance, however, the corresponding effect sizes provide a mag- nitude of the differences between benefits accrued by extraverts and introverts. Table 1 displays change scores on well-being as well as corresponding t-tests and effect sizes. Extraverts bene- fited more than introverts in the gratitude visit and savoring conditions, whereas introverts benefited more than extraverts in the 3 good things, active-constructive responding, and strengths conditions. Discussion This study examined the differential efficacy of a set of 5 PPIs using extraversion as a predictor of person-activity fit. First, this study replicated previous findings that these interven- tions can increase well-being—boosting happiness and reduc- ing depressive symptoms. Second, no overall differences emerged, on the whole, each intervention appeared just as effi- cacious within the total sample. However, taking into account personality demonstrated the extraverts and introverts benefit more from different interventions. Specifically, extraverts bene- fited more from the gratitude visit and savoring exercises and introverts benefited more from the three good things, active- constructive responding and strengths exercises. Although these differences did not reach significance, the magnitude of the effects in most cases were medium to large and on par with the difference found between treatment and control in many studies of PPIs (see Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). This provided initial support for the notion that extraversion may be an important predictor of how benefits from select PPIs and supports the suggestion that personality types might exist such that certain interventions might “take” while others do not (Seligman et al., 2005). Limitations in this study, however, were that the PPIs represented a variety of different skills and strategies. Although, some were predicted to be more social in nature and thus appeal uniquely to extraverts or introverts, this prediction was not altogether supported by the data. Further- more, it could be that some aspect of the instructions provided more of the unique matching to personality than the social component of the intervention. Lastly, given the small sample size many of the effects did not reach significance therefore replication of these findings is key to ensure that they are ro- bust. 1Extraversion was also used as a continuous measure and analyses were also run using quartiles of extraversion. Analyses using a continuous measure produced similar significance values and for analyses dividing partici ants into quartiles, analyses confirmed that a median split produced similar re- sults. Thus, as the goal was to be able to identify individuals who might enefit from a specific intervention a median split was retained despite the fact that moderator analyses are better powered with continuous measures. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1169  S. M. SCHUELLER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1170 Table 1. Change scores on composite well-being by exercise for extraverts vs introverts. Extraverts Introverts Exercise M SD M SD t p d 3 Good Things (n = 29) –.21 .43 .14 .54 1.98 .06 –.75 Active-Constructive (n = 30) –.12 .45 .22 .38 2.03 .05 –.75 Gratitude Visit (n = 29) .12 .39 –.11 .38 1.60 .12 .60 Savoring (n = 28) .04 .38 –.01 .44 0.34 .73 .13 Strengths (n = 28) –.05 .25 .11 .40 1.21 .24 –.45 Notes: Active-Constructive = Active-Constructive Responding. Positive d values reflect that extraverts benefited more than introverts, negative d values reflect that intro- verts benefited more than extraverts. Study 2 In Study 2 a single intervention, the gratitude visit, was modified to be more or less socially focused. This control for the possible confound between PPI strategy and social compo- nent of the intervention that was present in Study 1. In this study, participants completed the gratitude visit either in person, over the phone, or by mailing the letter to the target either via standard or electronic mail. Another aim of this study is to ex- amine whether delivering the gratitude letter in person is a nec- essary component of the exercise although doing so is empha- sized in the instructions (Seligman et al., 2005) and has been described as an emotional and moving part of the experience (Peterson, 2007; Seligman, 2002) other empirical evaluations have used the same exercise but modified as to be completed only via writing, with no actual delivery of the letter (Boehm, Lyubomirsky, & Sheldon, 2011; Lyubomirsky et al., 2011). No study has included both modifications of this design in the same study. It is predicted that findings from Study 1 will be replicated and that extraverts will benefit more from the in per- son gratitude visit exercise than introverts but that this pattern will be reversed for the phone and mail delivered interventions. Method Participants and Procedure Participants were 85 University of Pennsylvania undergradu- ate students who completed this study in exchange for course credit. The gender distribution was roughly equivalent with slightly more male (53.6%) than female (46.4%) participants. A mean age of 18.66 years (SD = 1.29) was consistent with using an undergraduate sample. The sample was predominantly Cau- casian (56.3%), whereas other ethnic groups were less repre- sented (20.5% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7.1% Black, 6.3% Hispanic, and 9.8% other). Participants were recruited from the University of Pennsyl- vania undergraduate subject pool. They were randomly as- signed to one of three conditions: a gratitude letter delivered in person (n = 29), via the phone (n = 28), via mail (n = 28) and provided instructions for the assigned exercise. Participants completed a baseline assessment measure that included the same measures as Study 1 with the exception that the Brief Big Five Inventory was replaced with a longer 44-item version. Participants completed their exercise during a week period and then completed post-intervention measures on a web-based survey. Descripti on o f Measures Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999): The BFI is a 44-item measure of personality. Each item is a descriptive phrase that taps into one of Big Five traits: openness (e.g., “is original, comes up with new ideas”), conscientiousness (e.g., “does things efficiently”), extraversion (e.g., “is talkative), agreeableness (e.g., “is helpful and unselfish with others”), and neuroticism (e.g., “can be tense”). Participants rate each item on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). For extraversion α = .89, for agreeableness α = .76, for conscientiousness α = .81, for neuroticism α = .89, and for openness α = .78. The remaining measures were the same as Study 1 including the Satisfaction with Life Scale (α = .84 at baseline and α = .85 at posttest), Authentic Happiness Inventory (α = .94 at baseline and α = .96 at posttest), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (positive affect subscale: α = .89 at baseline and α = .91 at posttest; negative affect: α = .88 at baseline and α = .90 at post- test), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (α = .89 at baseline and α = .91), and demographics including age, ethnicity, and gender. Results Statistical Analyses Statistical analyses followed the same rational as Study 1. Again, a median split of the measure of extraversion was used to create two groups of participants. In this study, 38 partici- pants were identified as introverts and 48 participants were identified as extraverts. A composite measure of well-being was created by z-scoring each of the dependent measures (hap- piness, life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, and de- pressive symptoms). The positive measures (AHI, SWLS, PA) were summed and given equal weighing before subtracting the sum of the equally weighted negative measures (NA, CES-D). This controls for the imbalance created by using three positive measures of well-being and two negative measures. This com- posite includes both cognitive and affective measures which is consistent with measurements of subjective well-being (Diener, 1984). Lastly, planned contrasts were conducted using the fol- lowing λ weights (in person: λ = 2, phone: λ = –1, mail: λ = –1) with positive values corresponding to the prediction that extra-  S. M. SCHUELLER verts would benefit more than introverts. Baseline Differences Study 2 largely replicated Study 1 in terms of baseline dif- ferences. Extraverts reported significantly greater levels of happiness, t(83) = 4.17, p < .001, life satisfaction, t(83) = 4.09, p < .001, and lower levels of depressive symptoms, t(83) = 2.85, p = .006. The groups did not differ on baseline reports of posi- tive affect, t(83) = 1.92, p = .06 or negative affect, t(83) = 1.13, p = .26. However, given the difference on the majority of de- pendent measures and the results and analyses in Study 1, base- line levels of well-being and extraversion were controlled for in all further analyses. Changes in Well-Being The three gratitude visit conditions led to significant in- creases in happiness, t(80) = 4.11, p < .001 and life satisfaction, t(80) = 2.38, p < .001 over the one week period. Decreases in negative affect, t(80) = 1.16, p = .25 and depressive symptoms, t(80) = 1.95, p = .05, were not statistically significant. Changes in positive affect, t(80) = 1.62, p = .11, were not significant as well. There were no significant differences between the condi- tions in changes in well-being, F(2, 78) = .01, p = .99. AN- COVA was used to investigate the interaction between extra- version and condition efficacy. No significant interaction be- tween intervention efficacy and extraversion was found, F(2, 74) = .35, p = .71. Planned contrast analyses were conducted to evaluate the specific theory that introverts would benefit more from the phone and mail conditions and extraverts would bene- fit more from the in person condition. The contrast analysis was not significant, t(79) = 1.03, p = .31 although the pattern of λ weights corresponded closely to the means of the groups ralert- ing = .87. Indeed, the condition that was identical to that of Study 1 (the gratitude visit in person) revealed a numerical greater benefit for extraverts (M = .02, SD = .93) than introverts (M = –.18, SD = .63) although this difference was not statisti- cally significant, t(25) = 1.01, p = .32, d = .40. Discussion This study addressed whether the gratitude visit could be modified to be a better “fit” for a given personality. Specifically, it was modified such that participants would either perform the visit in person, over the phone, or by mailing the letter to the recipient (either through standard or electronic mail). This ad- dressed one of the major concerns people often voice over the gratitude visit in that reading it aloud to another person seems like it might be uncomfortable. The prediction was that this form of social interaction would be especially problematic for introverts and therefore reduce the benefits of this PPI. Results confirmed that all formats of the gratitude visit led to improve- ments in well-being with no one format standing out as the most efficacious. Results with regards to specificity of mode of delivery and personality were mixed as in general the patterns supported the predictions and replicated the findings of Study 1 but again did not reach statistical significance. Again, the sam- ple in this study was small and it might be that larger studies are needed to address moderators of treatment efficacy given the power needed to find such effects. Combined Results Because Study 1 and Study 2 shared an identical condition (the gratitude visit in person), recruitment and study procedure, and a sample drawn from the same population (undergraduates from the University of Pennsylvania subject pool), the data from the two studies were combined using mega-analytic tech- niques. There was no significant study by treatment interaction which justified pooling participants from the studies together and giving each participant equal weight. Using this larger sample, it was found that extraverts receive larger boosts in well-being from the in-person gratitude visit exercise than in- troverts, t(55) = 2.03, p = .04, d = .55. General Discussion This series of studies investigated various PPIs to examine if extraversion could predict who might benefit from specific interventions. Summing across the studies, results supported the notion of “fit” by finding that extraverts who performed the gratitude visit in person received larger benefits to their well- being than introverts who performed the same exercise. Fur- thermore, in Study 2, some data suggested that gratitude visit might be more beneficial for introverts if performed either over the phone or by mailing the letter to the recipient by this finding needs additional confirmation. In general, moderation findings need replication across studies to demonstrate that effects are robust and transcend initial contexts in which studies are per- formed. These two studies complement each other in several ways. Both explored a single personality dimension (extraversion). Study 1 examined a set of 5 PPIs and investigated extraversion as a moderator, whereas Study 2 explored a specific PPI in more detail by modifying the instructions to determine if this could affect the “fit” of intervention based on extraversion. In this way, the second study serves as a replication of the findings based on one of the conditions contained within study 1. Repli- cating findings related to person-activity fit is particular impor- tant before using results as justification for recommendations. It is worth noting that across both studies, the efficacy of the interventions on average did not differ significantly. When personality was not considered, counting one’s blessings, per- forming a gratitude visit, savoring experiences, responding in an active-constructive manner, or using a signature strength in a new way, all increased well-being. Similarly, writing a letter of gratitude and then delivering it either in person, over the phone, or through the mail all increased well-being. An important question with regards to the “fit” of PPIs is whether interventions should match an individual’s strengths (e.g., extraverts performing social interventions) or address an individual’s deficits (e.g., introverts performing social interven- tions). This investigation found support for both models. For example, in Study 2 it did appear that extraverts gained larger boosts in well-being when performing the gratitude visit in person rather than performing it over the phone or mailing it to the recipient. In Study 1, however, introverts benefited more than extraverts from the active-constructive responding exercise. It is possible that introverts learned a new skill from this inter- vention: how to interact in a more active-constructive manner when responding to good news presented by other people. No research has examined whether extraverts are better active- constructive responders prior to being trained to respond this Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1171  S. M. SCHUELLER way, however, this style of responding is characteristic of cou- ples who enjoy greater relationship satisfaction (Gable et al., 2004). More research interested in addressing the question of personality fit should examine baseline differences in regards to the skills taught in PPIs. For example, how often people spon- taneously express gratitude, savor experiences, and respond in active-constructive manners and observe how much this relates to “fit” when practicing these interventions. Although it could be that the strategies that people sponta- neously use do not relate to those they benefit the most from when instructed in positive psychology strategies. A recent study examining the behaviors of those seeking happiness found that self-reported happiness-seeking strategies did not match the interventions people selected from a set of PPIs available via a smartphone application (Parks et al., 2012). These findings, however, compared groups of participants from two different procedures and additional research would be nec- essary to see if these replicating within-person as would be most relevant to research on person-intervention fit. Another possibility for the pattern of findings in this investi- gation is that sensitivity to social interaction is not a key feature of extraversion and the predicted pattern of matching needs to be modified. Lucas and Diener (2001) argue that extraverts are motivated by a strong desire to experience positive affect. Therefore, extraverts do not simply prefer social situations more than introverts, but extraverts enjoy pleasant situations more than introverts. It could be that the pattern of results comes from this tendency. Support for this notion comes from the observation that extraverts benefited more than introverts from the savoring exercise which is related to the experience of positive affect in the moment. Various limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of these studies. First, many of the relationships be- tween differential intervention efficacy and extraversion within a study were not statistically significant. In Study 1, despite a trend level moderation effect and confirmation of the overall specific matching hypothesis through planned contrast tests the statistical tests within each intervention demonstrating differen- tial benefit for introverts versus extraverts were not significant. Importantly, the gratitude visit in person condition which was shared across Studies 1 and 2 replicated the findings and the combined sample produced a significant finding. This demon- strates the importance of replicating results and ensuring that results are robust before drawing conclusions and making rec- ommendations for practice. This sample also used an under- graduate population and further work needs to determine if these findings would generalize to non-student samples. Fur- thermore, this sample was recruited from the university subject pool and some research indicates that differences exist between those who are recruited to complete PPIs versus those who are seeking out PPIs to engage in as an effort to increase their hap- piness (Lyubomirksy et al., 2011). As motivation might play an important role in person-activity fit examining fit in both self-selected happiness seeking samples and naïve populations is important to determine the universality of person-activity fit. Lastly, this study used personality as the determinant of person- activity fit and only examined extraversion. Although extraver- sion is a widely studied personality trait it might be worth con- sidering other variables such as participant’s preferences (i.e., Schueller, 2010, 2011). Expressed preferences of the partici- pants might be related to personality characteristics but be more proximal to decisions that might actually affect person-activity fit. Given that in most cases those working to recommend PPIs can gather feedback from those who aim to use the strategies it might be worth leaving personality behind altogether and fo- cusing on more revealed variables. Nevertheless, this study did support that exercises can be matched to a person’s personality. Results from study 1 sup- ported that extraverts benefit more from socially based PPIs and introverts benefit more from individually based PPIs. Study 2 supported that a specific PPI, the gratitude visit, could be modified to make it more or less socially focused and therefore a better fit for extraverts of introverts accordingly. Preliminary data from study 1 suggests that using a signature strength in a new way, counting one’s blessings, and responding in an ac- tive-constructive way are good fits for introverts; whereas, extraverts benefit more than introverts from conducting a grati- tude visit and savoring experiences. Following from these findings, practitioners using positive psychology should take into account people’s personalities when making recommenda- tions for PPIs and present modifications that might make a PPI a best fit for that person (see Lyubomirsky, 2008). Author Note and Acknowledgements Part of this work was completed as the author’s master’s the- sis at the University of Pennsylvania. The author would like to thank the members of his thesis committee: Marty Seligman, Robert DeRubeis, and Michael Kahana for their advice and guidance on this research. Furthermore, the author would also like to thank Acacia Parks and Nuwan Jayawickreme for com- ments on drafts, Angela Duckworth and Tara Chaplin for statis- tical advice, and Mike Maniaci for assisting with issues relevant to the Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by NIMH grant F32MH095345 (Schueller, P. I.). REFERENCES Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., & Paunonen, S. V. (2002). What is the central feature of extraversion? Social attention versus reward sensitivity. Journal of Personality a nd Social Psychology, 83, 245-252. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.245 Boehm, J. K., Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). A longitudi- nal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness- enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cognition & Emotion, 25, 1263-1272. doi:10.1080/02699931.2010.541227 DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1994). The happy personality: A meta- analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psycho- logical Bulletin, 124, 197-229. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197 Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1105-1117. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.5.1105 Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 Diener, E., Larsen, R. J., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). Person × situation interactions: Choice of situations and congruence response models. Journal of Personality a nd Social Psychology, 47, 580-592. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.3.580 Duckworth, A. L., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychol- ogy, 1, 629-651. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154 Emmons, R. A., Diener, E., & Larsen, R. J. (1986). Choice and avoid- ance of everyday situations and affect congruence: Two models of reciprocal interactionism. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1172  S. M. SCHUELLER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1173 chology, 51, 815-826. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.4.815 Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and sub- jective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377-389. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377 Fordyce, M. W. (1977). Development of a program to increase personal happiness. Journal of Counse ling Psychology, 24, 511-521. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.24.6.511 Fordyce, M. W. (1983). A program to increase happiness: Further stud- ies. Journal of Counseling Psycholog y, 30, 483-498. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.30.4.483 Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 228-245. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228 Giannopoulos, V. L., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2011). Effects of posi- tive interventions and orientations to happiness on subjective well- being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 95-105. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.545428 Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504-528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 Jose, P. E., Lim, B. T., & Bryant, F. B. (2012). Does savoring increase happiness? A daily diary study. Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 176-187. doi:10.1080/17439760.2012.671345 Lucas, R. E., & Diener, E. (2001). Understanding extraverts’ enjoyment of social situations: The importance of pleasantness. Journal of Per- sonality and Social P sychology, 81, 343-356. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.343 Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want. New York: Penguin Press. Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion, 11, 391-402. doi:10.1037/a0022575 Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111-131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111 Lyubomirsky, S., Tkach, C., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Pursuing sus- tained happiness through random acts of kindness and counting one’s blessings: Tests of two six-week interventions. Unpublished raw data. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111 Mongrain, M., Chin, J. M., Shapira, L. B. (2010). Practicing compas- sion increases happiness and self-esteem. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 963-981. doi:10.1007/s10902-010-9239-1 Murray, G., Judd, F., Jackson, H., Fraser, C., Komoti., A., Hodgins, G. et al. (2005). The five factor model and accessibility/remoteness: Novel evidence for person-environment interaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 715-725. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.007 Parks, A. C., Della Porta, M. D., Pierce, R. S., Zilca, R., & Lyubomir- sky, S. (2012). Pursuing happiness in everyday life: The characteris- tics and behaviors of online happiness seekers. Emotion. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0028587 Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full versus the empty life. Jour- nal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25-41. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Meas- urement, 1, 385-401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 Schueller, S. M. (2012). Person-activity fit. IIn A. C. Parks (Ed.), The Handbook of Positive Interventions. New York: Wiley-Interscience. Schueller, S. M. (2011). To each his own well-being boosting interven- tion: Using preference to guide selection. Journal of Positive Psy- chology, 6, 300-313. doi:10.1080/17439760.2011.577092 Schueller, S. M. (2010). Preferences for positive psychology exercises. Journal of Positive Psycholog y , 5, 192-203. doi:10.1080/17439761003790948 Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psy- chotherapy. American Psychologist, 61, 774-788. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774 Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Posi- tive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410-421. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 Sergeant, S., & Mongrain, M. (2011). Are positive psychology exer- cises helpful for people with depressive personality styles? Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 260-272. doi:10.1080/17439760.2011.577089 Shapira, L. B., & Mongrain, M. (2010). The benefits of self-compas- sion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. Journal of Positive Psycholog y , 5, 377-389. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.516763 Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alle- viating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 467-487. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593 Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

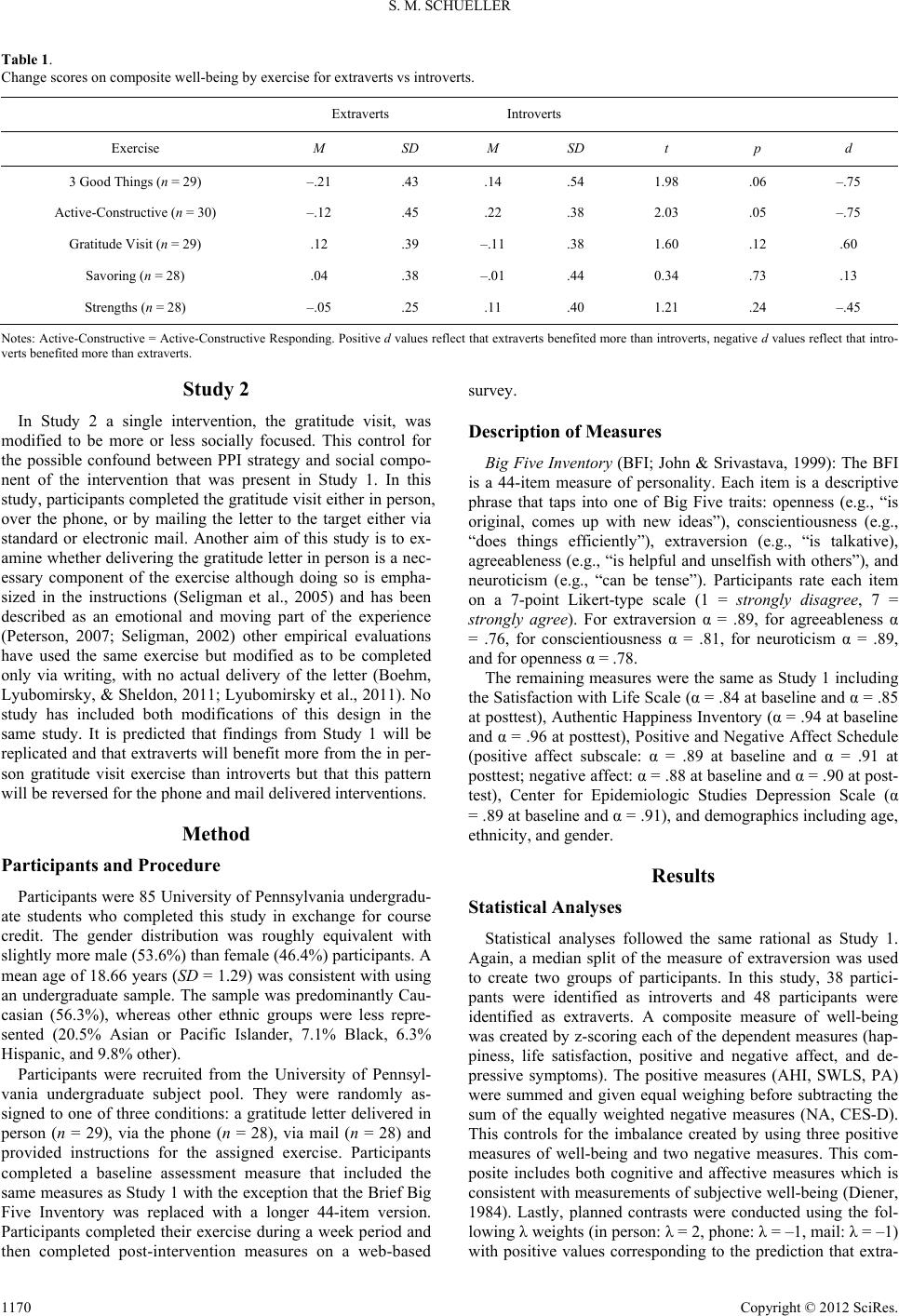

|