Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.12A, 1116-1124 Published Online December 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A165 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1116 The Impact of Positive Psychology on Diabetes Outcomes: A Review Joyce P. Yi-Frazier1*, Marisa Hilliard2, Katherine Cochrane3, Korey K. Hood4 1Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, USA 2Johns Hopkins Adherence Research Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA 3Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, USA 4Madison Clinic for Pediatric Diabetes, University of California, San Francisco, USA Email: *joyce.yi-frazier@seattlechildrens.org Received September 29th, 2012; revised October 23rd, 2012; accepted November 25th, 2012 Background: Due to the intensive treatment requirements needed to maintain diabetes control, optimal diabetes outcomes can be difficult to achieve for individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes from child- hood through adulthood. While risk factors related to individual differences in outcomes have been stud- ied in depth, there is a growing body of research that has revealed the effects of positive personal and en- vironmental characteristics on diabetes management and glycemic control. The goal of this review is to summarize the existent literature on the role of positive characteristics in diabetes outcomes. Method: Ex- tensive literature searches were conducted using Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL to identify studies as- sessing positive personal and environmental characteristics and diabetes outcomes. Included articles were published between 1989 and 2012. Results: Across the lifespan, positive personal characteristics such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, and adaptive coping were associated with diabetes management and glycemic control. Positive environmental factors such as parental monitoring and support were also important pre- dictors of good outcomes, particularly for adolescents. Conclusions: Positive personal and environmental factors have been shown to be associated with diabetes outcomes and should be addressed in efforts to improve outcomes at all life stages. Clinical research and practice may be enhanced through efforts to evaluate and promote positive personal and environmental factors with the ultimate goal of reducing bar- riers to optimal diabetes management and control. Keywords: Positive Psychology; Diabetes Introduction The beginning of the millennium signified an important turn- ing point for health research. As highlighted in the January, 2000 American Psychologist issue dedicated to “positive psy- chology,” a dramatic shift towards the study of “health” versus “illness” was emerging (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). As an alternative to the study of poor outcomes, the positive psychology movement provided the springboard for health researchers to begin to look at the other side of the coin: under- standing the role of positive traits, experiences, and environ- ments factors that contribute to wellness. Given the wide vari- ability in how patients with chronic illness are able to manage the daily behaviors needed to maintain physical and mental well-being, positive psychology has provided a particularly useful framework to identify the factors that promote successful disease management. Diabetes affects almost 26 million people and is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, with a total esti- mated cost to society of $174 billion (Centers for Disease Con- trol and Prevention, 2011). Nationally and internationally, the incidence and prevalence of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are growing (DIAMOND Project Group, 2006; Fox et al., 2006). Type 1 diabetes, often diagnosed in youth, is a disease in which the body does not produce insulin, thus requiring regular insu- lin administration and adjustment to mimic the function of the pancreas. Type 2 diabetes, which can develop anytime but often develops in adulthood, is much more common and is marked by insulin resistance, in which the body produces insulin but does not process it sufficiently. Type 2 diabetes treatment typically includes lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, physical activity) and may or may not require medication and/or insulin admini- stration. To manage diabetes optimally, intense efforts by the patient are needed. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes are both com- plex chronic diseases involving a variety of components of care, including medication adherence, diet, exercise, glucose moni- toring, and general disease awareness such as recognizing high or low blood sugars, managing sick days, and social adjustment at work or school. Inevitably, burnout, stress, or other life cir- cumstances may provide a barrier to optimal diabetes manage- ment and glycemic control, but debilitating complications can occur if attention to one’s disease is neglected (Diabetes Con- trol and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993; Polonsky, 1996). Barriers to self-management occur at all stages of life. Al- though much has been discussed about distress, depression, and other predictors of poor outcomes in diabetes, more recently there has been a rise of interest and publications on the positive traits, mechanisms, and environments that associate with better diabetes management and glycemic control (Christie & Barnard, 2012; Hilliard, Harris, & Weissberg-Benchell, 2012). This re- *Corresponding author.  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. view focuses on the adoption and impact of positive psychol- ogy in the area of diabetes care, specifically in regards to the positive individual characteristics and environmental factors that have been reported with diabetes management and/or gly- cemic control. Method Literature searches were conducted from Medline, CINAHL and PsychInfo search engines between July and August 2012. Table 1 outlines the operational definitions and measurement tools used for the search terms used hypothesized to be related to diabetes outcomes based on general positive psychology literature (i.e., Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). The primary diabetes outcomes examined were diabetes management and glycemic control. Measures of diabetes man- agement generally capture information on self-care behaviors such as checking blood glucose levels, frequency of exercise, administering and adjusting insulin or other medications, and meal planning. In some cases, non self-report data are used to describe diabetes management, such as downloading a blood glucose meter and gathering data such as the average number of blood glucose checks per day. Diabetes control, or glycemic control as referred henceforth, is measured by the hemoglobin A1c value, which is obtained from a blood sample. A1c is the definitive measure of glycemic control as it approximates average blood glucose values over the prior 2 - 3 months. It has been used in all major clinical trials of diabetes (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993) and is part of standard diabetes care. In healthy persons, average A1c typically ranges from 4.0% - 6.0%, and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recom- mends an A1c level of <7.0% for most adults (American Dia- betes Association, 2011). In youth, ADA recommendations are <8.5 for youth < 6 years olds, <8.0 for 6 - 12 year olds, and <7.5 for 13 - 18 year olds (Silverstein et al., 2005). As the landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial showed, A1c is directly related to the onset and severity of diabetes complications. From a prevention standpoint, lowering A1c one point confers a 40% risk reduction of retinopathy, a major com- plication of diabetes (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1993). A1c is therefore the gold standard measure of control in people with diabetes. To capture the range of positive constructs that have been studied in diabetes, research in both pediatric and adult litera- ture were included, spanning type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Asso- ciation statistics between the positive characteristics and diabe- tes outcomes were presented when possible, thus qualitative studies were excluded. Further, so that associations could be generally compared, this review did not include studies that Table 1. Operational definitions and measurement tools of positive individual and environmental factors linked with diabetes outcomes. Operational definition Examples of measurement tools used in cited research Individual f actors: Self-efficacy A person’s confidence in their ability to complete certain diabetes-specific actions related to diabetes management Self-efficacy for diabetes self-management, Perceived diabetes self-management scale Self-esteem An individual’s perception of self-worth Rosenberg self-esteem scale Personality traits Traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness, and openness NEO Personality Inventory, Personality Research Form Resilience An individual’s capacity to maintain psychological and physical well-being in the face of stress Wagnild and Young Resilience Scale, or combination of constructs Adaptive coping Effectively dealing with a stressor Responses to Stress Questionnaire, Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations, Diabetes Coping measure, COPE, Coping Styles, Emotional Approach Coping Scale Internal locus of control The belief that outcomes depend on one’s own behavior, as opposed to external forces or circumstances Diabetes Locus of Control Scales, Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scales Sense of coherence One’s enduring feeling of confidence to meet demands and challenges across internal and external environments Sense of Coherence Scale Optimism/Hope Expectations for positive outcomes Life Orientation Test Children’s Hope Scale Religion/ Spirituality Religious participation Specific questions re: participation Environmental factors: Family communication Positive, optimistic discussions about diabetes management and possible complications Family Communication about Diabetes and Future Health Scale, Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Communication scale) Parental involvement Parental sole or shared (e.g., with youth) responsibility for executing tasks of diabetes management and/or monitoring and supervision of youth completion of diabetes management tasks Collaborative Parent Involvement Scale, Parental Monitoring of Diabetes Care Scale, Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire Family Environment Family characteristics including cohesion, adaptability, and organization Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales, Family Environment Scale Family and Social support Perception of care from others, including friends and parents Diabetes Care Profile, Social support Questionnaire, Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist, Diabetes Social Support Interview, Mother-Father-Peer (acceptance scale) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1117  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. incorporated an intervention to bolster positive characteristics. Lastly, only articles written in English were included. Results Over 80 distinct studies describing an association between positive psychosocial factors and diabetes outcomes (diabetes management and/or glycemic control) published between 1989 and 2012 in pediatric or adult diabetes settings were assessed (Table 2). The following sections highlight the prominent posi- tive individual characteristics and environmental factors that have been reported. Positive Individual Characteristics Self-esteem, or perception of one’s self-worth, was fre- quently cited as having positive impact on diabetes outcomes. Self-esteem was associated with diabetes management and A1c in youth with type 1 diabetes (rs = .41, –.36, ps < .001 respec- tively, Schneider et al., 2009). For young adults with type 1 (Johnston-Brooks, Lewis, & Garg, 2002) and adults with type 1 and type 2 (Kneckt, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, Knuuttila, & Syrjälä, 2001; Weinger, Butler, Welch, & La Greca, 2005), self-esteem associated with diabetes management (i.e., β = .29, p < .05 in young adults), but not A1c (Johnston-Brooks et al., Table 2. The major positive psychosocial variables associated with diabetes outcomes across age groups and type 1 (T1) and type 2 (T2) diabetes populations, as represented in the literature. Youth/Adolescents (T1) (age ≤ 18) Young Adults (T1) (specifically ages 18 - 35) Adults (T1) (ages 18+) Adults (T2) (all ages)* Individual f actors: Self-esteem Schneider et al., 2009 Johnston-Brooks, 2002 Kneckt et al., 2001 Weinger et al., 2005 Fry et al., 2011 Weinger et al., 2005 Self-efficacy Chih et al., 2010 Helgeson et al., 2011 Iannotti et al., 2006 Johnston-Brooks, 2002 de Ridder et al., 2004 Sousa et al., 2005 Weinger et al., 2005 Cherrington et al., 2009 Fry et al., 2011 Hunt et al., 2012 Nakahara, 2006 Nozaki et al., 2009 Sharoni & Wu, 2012 Sousa et al., 2005 Venkataraman et al., 2012 Weinger et al., 2005 Zulman et al., 2012 Personality traits Helgeson & Palladino, 2012 Vollrath et al., 2007 Wheeler et al., 2012 Giles et al., 1992 Fry et al., 2011 Lane et al., 2000 Resilience Perfect et al., 2012 Yi et al., 2008 Yi-Frazier et al., 2010 DeNisco, 2010 Mertens et al., 2011 Yi et al., 2008 Yi-Frazier et al., 2010 Adaptive coping Jaser et al., 2012 Jaser and White, 2011 Bazzazian et al.,2012 Luyckx et al., 2010 Hartemann-Heurtier et al., 2001 Yi-Frazier et al., 2010 Smalls et al., 2012 Yi-Frazier et al., 2010 Environmental factors: Family communication Berg et al., 2011 Palmer et al., 2011 Wysocki et al., 2011 Parental involvement/monitoring Anderson et al., 1997 Berg et al., 2008 Berg et al., 2011 Ellis et al., 2007 Helgeson et al., 2008 Horton et al., 2009 Palmer et al., 2011 Wysocki et al., 2009 Family Environment Cohen et al., 2004; Hanson et al., 1989; Hauser et al., 1990; Herge et al., 2012; Jacobson et al., 1994 Family and Social support Berg et al., 2011 Ellis et al., 2007 La Greca et al., 1995 Aalto et al., 1997 Boas et al., 2012 Brody et al., 2008 Hunt et al., 2012 Khan et al., 2012 Note: *Only manuscripts addressing adults with type 2 diabetes were found for this review. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1118  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. 2002; Kneckt et al., 2001; Weinger et al., 2005). Related to self-esteem, general self-efficacy can be defined as a person’s confidence in their ability to complete certain actions (Bandura, 1997), but this construct was most often op- erationalized specific to diabetes management (Table 1). Scales assessing diabetes self-efficacy, though varied, generally meas- ured the perceived ability to perform various diabetes manage- ment tasks. Among adolescents, self-efficacy associated with better diabetes management for younger (ages 10 - 12) and older (ages 13 - 16) type 1 youth, rs = .25, .37 respectively, ps < .05; (Iannotti et al., 2006). Similarly, studies reported signifi- cant associations between self-efficacy and A1c in this age group (r = –.21, p < .05 for 13 - 16 year olds; Iannotti et al., 2006; r = –.30, p < .05 in 12 - 20 year olds; Chih, Jan, Shu & Lue, 2010). In fact, Chih et al. (2010) reported that patients with higher self-efficacy scores were 1.63 times more likely to achieve ADA targets for glycemic control, a feat that adoles- cents rarely meet (Petitti et al., 2009). In young adults, self-efficacy alone was the best predictor of diabetes management (β = .63, p < .0005) and A1c (β = –.30, p < .05), performing better as a predictor than self-esteem (Johnston-Brooks et al., 2002). For older adults with type 2 diabetes, self-efficacy was associated with diabetes manage- ment and glycemic control both cross-sectionally (Venkatara- man et al., 2012; Zulman, Rosland, Choi, Langa, & Heisler, 2012) and longitudinally (Nakahara et al., 2006). One study in individuals with type 2 diabetes reported a sex difference in the association between self-efficacy and glycemic control, show- ing a stronger effect for men versus women (Cherrington et al., 2008). Both self-esteem and self-efficacy were associated with a reduced risk for mortality in older adults with type 2 diabetes (Fry & Debats, 2011). Among general personality traits such as the “Big Five”, (the five major dimensions of personality), agreeableness, the ten- dency to value cooperation and social harmony, and conscien- tiousness, the tendency to engage in self-discipline and be achievement-oriented, were found to be associated with better glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes (rs = –.31, –.35 respectively, ps < .05; Vollrath, Landolt, Gnehm, Laimbacher, & Sennhauser, 2007). Conscientiousness and extraversion, the tendency to be outgoing, positive, and seek social interactions, were also found to be associated with better diabetes manage- ment in adolescents with type 1 diabetes (rs = .48, .52, respec- tively ps < .01; Wheeler, Wagaman, & McCord, 2012). Hel- geson and Palladino (2012) reported that for adolescents with type 1 diabetes, a positive orientation towards others (called communion) was associated with both better self-management and glycemic control. In adults with type 1 diabetes, personality traits such as higher achievement and social desirability associ- ated with better control (Giles, Strowig, Challis, & Raskin, 1992). For adults with type 2 diabetes, the traits of neuroticism and perfectionism, which may not traditionally be considered “positive”, associated with better outcomes (r = –.22, p < .05 for neuroticism/A1c association; Lane et al., 2000; relative risk for mortality was 29% lower for those with high perfectionism scores; Fry & Debats, 2011). Resilience was also well-cited as an important individual characteristic contributing to diabetes health. For this review, resilience was distinguished as a personal resource, defined as a “baseline” or “innate” characteristic as opposed to other defini- tions of resilience that emphasize resilient outcomes (Hilliard et al., 2012). In youth, resilience (as defined by sense of mastery and optimism) was associated with A1c (rs = –.36, –.32 respec- tively, p < .05; Perfect & Jaramillo, 2012). In adults, a study using the Wagnild and Young Resilience Scale found resilience to be associated with glycemic control in African American women with type 2 diabetes (r = –.27, p < .05; DeNisco, 2011). Yi, Vitaliano, Smith, Yi and Weinger (2008) reported resilience (factor score of self-mastery, self-esteem, self-efficacy, opti- mism) associated with 1-year follow-up A1c (β = –.39, p < .01) in adults with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. In fact, higher levels of resilience were found to buffer the effects of rising distress on rising A1c. As a follow-up to that study, the authors reported high levels of resilience were also associated with adaptive coping (Yi-Frazier et al., 2010). Studies showing adaptive coping as a means towards better diabetes outcomes were prevalent (Har- temann-Heurtier, Sultan, Sachon, Bosquet, & Grimaldi, 2001; Yi-Frazier et al., 2010). In adolescents, coping was found to be associated with outcomes such that primary control behaviors (including problem solving, emotional expression, and emo- tional regulation), and secondary control behaviors (including acceptance, positive thinking, cognitive restructuring, and dis- traction) were associated specifically with diabetes manage- ment behaviors (rs = .37, .30 respectively, ps < .001), general quality of life (rs range from .43 to .54, ps < .01) and A1c (rs range from –.14 to –.43, ps < .05) across two studies (Jaser et al., 2012; Jaser & White, 2011). In young adults with type 1 diabetes, task oriented coping predicted better adjustment to diabetes (Bazzazian & Besharat, 2012) and high levels of tackling spirit and diabetes integration, subscales of an adaptive coping measure, associated with better A1c (rs = –.22, –.17 respectively, ps < .05; Luyckx, Vanhalst, Seiffge-Krenke, & Weets, 2010). In adults with type 2 diabetes (Smalls et al., 2012), emotional processing and emotional ex- pression were associated with diabetes management behaviors (rs ranged from .13 to .23 on measures of adherence to general diet, exercise, and blood sugar testing, all ps < .05). Positive individual resources less-frequently mentioned in the literature included locus of control, sense of coherence, optimism, and spirituality. In a meta-analysis of internal locus of control and glycemic control, the authors found no correla- tion across 13 studies (r = –.01, p = n.s.; Hummer, Vannatta, & Thompson, 2011). It seems that locus of control may be most useful in the context of a more specific patient population, as one study of adults with type 2 diabetes reported a significant effect between locus of control and A1c for those with low self-efficacy and high outcome expectancy (O’Hea et al., 2009). Research on sense of coherence, one’s confidence to meet demands, has shown associations with acceptance and well- being in adults, but not with glycemic control (Lundman & Norberg, 1993; Richardson, Adner, & Nordström, 2001). However, Cohen and Kanter (2004) showed an indirect effect from sense of coherence to glycemic control mediated by ad- herence and Ahola et al. (in press) reported that patients with a strong sense of coherence achieved an A1c level below 7.5% more frequently than those with a weak sense of coherence. Only a few studies exist that assess optimism or hope in rela- tion to diabetes outcomes. In youth with type 1 diabetes, Lloyd, Cantell, Pacaud, Crawford and Dewey (2009) found hope to be associated with diabetes management and A1c (rs = .63, –.39 respectively, ps < .01). De Ridder, Fournier and Bensing (2004) reported no association of optimism with either diabetes man- agement or A1c for adults with type 1 diabetes (2004). One Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1119  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. research group (Yi-Frazier et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2008) assessed optimism within a factor score they termed “resilience”, which was previously discussed. Lastly, spirituality was reported in one study of outpatients with type 2 diabetes with a co-occurring mental disorder, and found to be associated with quality of life, but not glycemic control in these patients (Murray-Swank et al., 2007). Positive Environmental Factors Consistent with a social-contextual framework of adjustment and self-management in chronic conditions, the friends and families of individuals with diabetes play an important role in their well-being, successful self-management, and achievement of in-range glycemic control (Modi et al., 2012). As children move through adolescence, maintaining effective family com- munication and supportive parental involvement in diabetes management are among the most critical processes in diabetes management and control (Jaser & White, 2011; Palmer et al., 2011; Wysocki, 2002). Optimistic, positive family communica- tion about diabetes and its complications has been linked with better diabetes management (rs range = .25 to .64, p < .01; Berg et al., 2011; Wysocki, Lochrie, Antal, & Buckloh, 2011) and in some cases glycemic control (rs range = –.11, p = n.s.; Berg et al., 2011 to .42, p < .0001; Wysocki et al., 2011). Parent and teen collaboration and shared responsibility for executing the tasks of diabetes management have also been associated with better diabetes management (rs = .25 - .29, p < .05; Anderson, Ho, Brackett, Finkelstein, & Laffel, 1997) and control (Hel- geson, Reynolds, Siminerio, Escobar, & Becker, 2008; Wy- socki et al., 2009). Specifically, shared responsibility between parents and youth has demonstrated up to 0.5% - 1.0% im- provements in A1c (i.e., 9.0% vs 8.2%; Helgeson et al., 2008; Wysocki et al., 2009). In adolescence, mother-, father-, and teen-reports of parental monitoring of diabetes management task completion (e.g., through direct observation, discussion, or other methods of supervision), have been linked with better diabetes management in the range of r = .13 (p = n.s.; Berg et al., 2008) to .47 (most ps < .05; Berg et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2007; Horton, Berg, Butner, & Wiebe, 2009) and with lower A1C in the range of r = .04 (p = n.s.; Ellis et al., 2007) to –.31 (most ps < .05; Berg et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2011; Horton et al., 2009). Broadly, positive family relationships have demonstrated links with better diabetes outcomes in youth, although less con- sistently than negative family interaction patterns (e.g., conflict; Laffel et al., 2003). Cohen, Lumley, Naar-King, Patridge and Cakan (2004) report significant differences in diabetes man- agement (p < .01) and in glycemic control (p < .01) among children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes with higher ver- sus lower levels of family cohesion. Others have found similar results, with parental perceptions of family cohesion demon- strating associations with better self-management (r = .32, p < .05; Hauser et al., 1990) and with a faster rate of improve- ment in boys’ (but not girls’) glycemic control over four years (r = –.71, p < .001; Jacobson et al., 1994). While Hanson and colleagues (Hanson, Henggeler, Harris, Burghen, & Moore, 1989) did not replicate the link between cohesion and glycemic control (r = –.14, p = n.s.), they reported significant associa- tions between glycemic control and adaptability, another posi- tive family characteristic (r = –.25, p < .05). Cohen et al. (2004) also evaluated adaptability and did not find significant links with diabetes management or glycemic control. Finally, some studies find associations between family organization and dia- betes management (rs range .05, p = n.s. to .35, p < .05; Hanson et al., 1989; Herge et al., 2012) and glycemic control (rs range –.07, p = n.s. to –.16 p < .05; Herge et al., 2012; Jacobson et al., 1994). Specific parenting behaviors have been evaluated with rela- tion to youths’ diabetes management and control and tend to show stronger relations to diabetes management than to glyce- mic control. While parental support (emotional, tangible, and related to encouraging youth autonomy) has largely demon- strated associations with better self-management (rs range from .08, p = n.s., to .37, p < .05; Berg et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2007; La Greca, Swales, Klemp, Madigan, & Skyler, 1995; Palmer et al., 2011), links with glycemic control have not al- ways been significant (r range: –.03, p = n.s. to –.15, p < .05; Berg et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2007). Similarly, evaluations of parental acceptance (Berg et al., 2008; Berg et al., 2011) and empathy (Lloyd et al., 2009) generally show relations with better diabetes management (rs range from .09, p = n.s. to .40, most ps < .05), and inconsistent associations with better glyce- mic control (rs range: –.13, p = n.s. to –.28, p < .05). Other parent characteristics that have shown links with better diabetes management and control, include authoritative parenting style, with higher versus lower levels linked with better diabetes management, p < .01 (Monaghan, Horn, Alvarez, Cogen, & Streisand, 2012) and family knowledge about diabetes, which independently predicts glycemic control after controlling for other influences, p = .05 (Butler et al., 2008). Social support and relationships have been found to be im- pactful for adults as well. Dale, Williams, and Bowyer (in press) conducted a systematic review of peer support interventions on diabetes outcomes in adults and reported that of 13 RCTs that used A1c as an outcome, three found peer support to be statis- tically significant on A1c. Other positive health outcomes were also reported, including better/improved blood pressure, cho- lesterol, BMI, diabetes management, and psychological out- comes. One study of rural African-American adults with type 2 diabetes showed an indirect association between social support and A1c, through promotion of glucose monitoring (Brody, Kogan, Murry, Chen, & Brown, 2008). Summary Model Based on this review, Figure 1 is proposed as a conceptual model of how positive individual and environmental character- istics may directly and indirectly relate to behavioral and bio- logical diabetes outcomes. This model is based on other con- ceptual models of individual and environmental factors im- pacting health behaviors and outcomes (Hilliard et al., 2012; Modi et al., 2012). At the far left, innate characteristics may interact with environmental variables (as indicated with the double-headed arrow) to both directly and indirectly associate with diabetes outcomes (far right of Figure 1). Interactions between individual and environmental factors were not detailed in this review, as they are not routinely analyzed or reported. However, consistent with social-ecological models of health behavior (e.g., Modi et al., 2012), many studies evaluated both sets of influences on diabetes management and control (Herge et al., 2012, Berg et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2007). Coping and self-efficacy (Figure 1, center) are distinguished from the other individual characteristics (i.e., self-esteem, resilience, and per- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1120  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1121 Innate Characteristics: Self-esteem Resilience Personality Behavioral Mechanisms: Coping Self-efficacy Outcomes Diabetes management Glycemic control Environmental Characteristics: Social support Family dynamics Communication Figure 1. Hypothesized path model of positive characteristics as they influence diabetes health outcomes. sonality traits) as they represent behavioral processes by which the innate and environmental characteristics theoretically im- pact diabetes management and control. In addition, these mechanisms are more likely to be modifiable through interven- tion. As noted above, several studies examined path models that mirrored our conceptual model. For example, on an individual level, Yi-Frazier and colleagues (2010) showed how resilience may impact diabetes management and control through en- hanced coping, and Johnston-Brooks and colleagues (2002) showed similar associations between self-esteem, self-efficacy, and diabetes outcomes. The associations of family-level posi- tive factors were demonstrated by Herge and colleagues (2012), who examined a path model linking family organization, self- esteem, and diabetes management and control in youth. Both diabetes management and glycemic control are important out- comes, with robust evidence to support the order of effects depicted here (i.e., Hood, Peterson, Rohan, & Drotar, 2009). Discussion As evidenced by the numerous articles cited in this paper, diabetes research has embraced the positive psychology move- ment. Positive individual and environmental factors have been explored and found to be impactful correlates of behavioral and biologic diabetes outcomes across the lifespan. Numerous and consistent reports were found demonstrating significant asso- ciations between positive characteristics and diabetes self-care and glycemic control. These findings were often supported across diverse populations of age, race, location, and diabetes type. When available, correlation or standardized coefficients were reported to give a more precise picture as to the strength of the associations between the positive characteristic and diabetes outcomes. In general, association statistics were small to mod- erate (rs most often ranged between .2 and .4) yet often statis- tically significant. Clearly additional demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors are involved in predicting diabetes out- comes, but the consistency and pervasiveness of the results for the ones highlighted here support the role of these positive variables in diabetes health outcomes. Discrepancies in associations may be due to the variety of measurements used to assess these factors, particularly those that are not diabetes-specific. For example, many measures of general family characteristics (e.g., cohesion, organization) were used across studies, resulting in a particularly wide range of association statistics for those variables. Also, diabetes management was assessed in multiple ways, through self-report, frequency of blood glucose monitoring, and/or interviews, each of which may produce different values (Kichler, Kaugars, Maglio, & Alemzadeh, 2012) and may have influenced the strength of associations reported here. Of all search terms for individual characteristics used for this review, self-efficacy was the most prominent, both in quantity of articles assessing the construct, and for the overall magnitude and consistency of the associations with diabetes outcomes. This was true spanning pediatric through older adult popula- tions, for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and across urban and rural settings. Clearly one’s confidence in the ability to perform the tasks needed to maintain optimal glycemia is critical. The abil- ity to specify domains or types of self-efficacy (e.g. exercise self-efficacy) make it amenable to precise, targeted intervention. Indeed, these types of interventions have been shown to im- prove self-efficacy and subsequent outcomes (George et al., 2008; van der Heijden, Pouwer, Romeijnders, & Pop, 2012; Wu et al., 2011). Coping is another area where interventions have shown beneficial effects on diabetes management and control through their impact on coping behaviors (Grey, Boland, Davidson, Li, & Tamborlane, 2000; Grey, Jaser, Whittemore, Jeon, & Lindemann, 2011). Our results indeed support inter- vention efforts to promote adaptive coping, as consistent evi- dence for the association of adaptive coping and outcomes was found, particularly for self-care behaviors. As self-efficacy and coping are generally thought to be mechanisms of diabetes outcomes (Figure 1), it was interesting that a handful of the more innate individual characteristics were found to be similarly impactful on diabetes health. In particular, self-esteem, resilience, and personality traits were fairly strong correlates of outcomes, particularly with diabetes management. As depicted in Figure 1, one hypothesis might be that the in- nate characteristics influence the modifiable behavioral mecha- nisms (e.g., coping and self-efficacy), which in turn affect dia- betes management and A1c. Given the relative success of in- terventions targeting personal resources (e.g., self-esteem, op- timism) in other populations (i.e., Meevissen, Peters, & Alberts, 2011), more attention should be given to interventions bolster- ing these resources among individuals with diabetes, with the goal of strengthening behavioral mechanisms that facilitate better diabetes management and control. This review revealed that positive environments also affect outcomes in children and adults with diabetes. Family charac- teristics including cohesion, organization, and adaptability were all linked with better youths’ diabetes outcomes. It may be that positive family factors like these are components of a house- hold that prioritizes diabetes management and provides the structure for successful self-management, which can promote self-efficacy and ultimately set the stage for effective family  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. teamwork in executing the multiple tasks of diabetes manage- ment (Herge et al., 2012). Specific positive family behaviors were also shown to have a robust relationship with youths’ diabetes outcomes. Just as conflict can hamper positive com- munication and problem-solving, families who interact in posi- tive, collaborative ways may encourage open communication and thus make it possible for youth and their parents to col- laborate in managing the multiple components of diabetes care. Parents’ encouraging and supporting youth in completing their own self-management may exert positive effects on diabetes outcomes by providing opportunities for teens to gain experi- ence coping with and solving diabetes-related challenges, there- by supporting adolescents’ emerging autonomy (Berg et al., 2011; Wysocki, 2002), and promoting their self-efficacy (Berg et al., 2011). Thus, intervening at the level of the family to promote a supportive, collaborative environment has consis- tently demonstrated benefits for diabetes management and con- trol (Anderson, Brackett, Ho, & Laffel, 1999; Laffel et al., 2003; Wysocki et al., 2007; Wysocki et al., 2008). In sum, the purpose of this paper was to provide a compre- hensive synthesis of the developing literature on positive psy- chology in diabetes research and practice. There is clear evi- dence of the impact of the positive psychology framework on the daily management and health outcomes of people with dia- betes. In general, this suggests that our research and clinical encounters for people with diabetes should equally focus on what is going well as opposed to only the areas that need im- provement. More specifically, clinicians and researchers should 1) implement measurements of wellness, and 2) target positive areas in addition to deficits during our interventions in these encounters. Much work is left to be done in achieving these specific goals from both clinical and research perspectives. For example, more work could be done to further explore how the associations between individuals’ positive characteristics and health outcomes may be influenced by characteristics of their environments (e.g., perhaps high levels of family support am- plify the impact of self-efficacy on diabetes management and control). However, this review emphasizes the significant pro- gress made thus far and shows that the field is indeed on the right track toward optimizing health outcomes for this impor- tant segment of our population. REFERENCES Ahola, A. J., Saraheimo, M., Forsblom, C., Hietala, K., Groop, P. H., & Group, F. S. (in press). The cross-sectional associations between sense of coherence and diabetic microvascular complications, gly- caemic control, and patients’ conceptions of type 1 diabetes. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 142. American Diabetes Association (2011). Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care, 34, S11-S61. doi:10.2337/dc11-S011 Anderson, B., Ho, J., Brackett, J., Finkelstein, D., & Laffel, L. (1997). Parental involvement in diabetes management tasks: Relationships to blood glucose monitoring adherence and metabolic control in young adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of Pe- diatrics, 130, 257-265. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70352-4 Anderson, B. J., Brackett, J., Ho, J., & Laffel, L. M. (1999). An office- based intervention to maintain parent-adolescent teamwork in diabe- tes management. Impact on parent involvement, family conflict, and subsequent glycemic control. Diabetes Care, 22, 713-721. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.5.713 Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: WH Freeman Co. Bazzazian, S., & Besharat, M. A. (2012). An explanatory model of adjustment to type I diabetes based on attachment, coping, and self-regulation theories. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 17, 47-58. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.575168 Berg, C. A., Butler, J. M., Osborn, P., King, G., Palmer, D. L., Butner, J. et al. (2008). Role of parental monitoring in understanding the bene- fits of parental acceptance on adolescent adherence and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 31, 678-683. doi:10.2337/dc07-1678 Berg, C. A., King, P. S., Butler, J. M., Pham, P., Palmer, D., & Wiebe, D. J. (2011). Parental involvement and adolescents’ diabetes man- agement: The mediating role of self-efficacy and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 329- 339. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq088 Brody, G. H., Kogan, S. M., Murry, V. M., Chen, Y. F., & Brown, A. C. (2008). Psychological functioning, support for self-management, and glycemic control among rural African American adults with diabetes mellitus type 2. H ealth Psychology, 27, S83-S90. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S83 Butler, D. A., Zuehlke, J. B., Tovar, A., Volkening, L. K., Anderson, B. J., & Laffel, L. M. (2008). The impact of modifiable family factors on glycemic control among youth with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 9, 373-381. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00370.x Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Dis- ease Control and Prevention. Cherrington, A., Ayala, G. X., Amick, H., Scarinci, I., Allison, J., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2008). Applying the community health worker model to diabetes management: Using mixed methods to assess im- plementation and effectiveness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19, 1044-1059. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0077 Chih, A. H., Jan, C. F., Shu, S. G., & Lue, B. H. (2010). Self-efficacy affects blood sugar control among adolescents with type I diabetes mellitus. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 109, 503- 510. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60084-8 Christie, D., & Barnard, K. D. (2012). Supporting resilience and posi- tive outcomes in families, children, and adolescents. In K. D. Bar- nard, & C. E. Lloyd (Eds.), Psychology and diabetes ca r e (pp. 47-68). London: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-85729-573-6_3 Cohen, D. M., Lumley, M. A., Naar-King, S., Partridge, T., & Cakan, N. (2004). Child behavior problems and family functioning as predictors of adherence and glycemic control in economically disadvantaged children with type 1 diabetes: A prospective study. Journal of Pedi- atric Psychology, 29, 171-184. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsh019 Cohen, M., & Kanter, Y. (2004). Relation between sense of coherence and glycemic control in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Behavioral Medicine, 29, 175-183. doi:10.3200/BMED.29.4.175-185 Dale, J. R., Williams, S. M., & Bowyer, V. (in press). What is the effect of peer support on diabetes outcomes in adults? A systematic review. Diabetic Medicine, 29, 1361-1377. De Ridder, D., Fournier, M., & Bensing, J. (2004). Does optimism affect symptom report in chronic disease? What are its consequences for self-care behaviour and physical functioning? Journal of Psy- chosomatic Research, 56, 341-350. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00034-5 DeNisco, S. (2011). Exploring the relationship between resilience and diabetes outcomes in African Americans. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practit ioners, 23, 602-610. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00648.x Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993). The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and pro- gression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 977-986. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291401 DIAMOND Project Group (2006). Incidence and trends of childhood Type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990-1999. Diabetic Medicine, 23, 857- 866. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01925.x Ellis, D. A., Podolski, C. L., Frey, M., Naar-King, S., Wang, B., & Moltz, K. (2007). The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1122  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 907-917. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009 Fox, C. S., Pencina, M. J., Meigs, J. B., Vasan, R. S., Levitzky, Y. S., & D’Agostino, R. B. (2006). Trends in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus from the 1970s to the 1990s: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 113, 2914-2918. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613828 Fry, P. S., & Debats, D. L. (2011). Perfectionism and other related trait measures as predictors of mortality in diabetic older adults: A six-and-a-half-year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology, 16, 1058-1070. doi:10.1177/1359105311398684 George, J. T., Valdovinos, A. P., Russell, I., Dromgoole, P., Lomax, S., Torgerson, D. J., et al. (2008). Clinical effectiveness of a brief edu- cational intervention in Type 1 diabetes: Results from the BITES (Brief Intervention in Type 1 diabetes, Education for Self-efficacy) trial. Diabetic Medicine, 25, 1447-1453. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02607.x Giles, D. E., Strowig, S. M., Challis, P., & Raskin, P. (1992). Personal- ity traits as predictors of good diabetic control. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 6, 101-104. doi:10.1016/1056-8727(92)90019-H Grey, M., Boland, E. A., Davidson, M., Li, J., & Tamborlane, W. V. (2000). Coping skills training for youth with diabetes mellitus has long-lasting effects on metabolic control and quality of life. Journal of Pediatrics, 137, 107-113. doi:10.1067/mpd.2000.106568 Grey, M., Jaser, S. S., Whittemore, R., Jeon, S., & Lindemann, E. (2011). Coping skills training for parents of children with type 1 diabetes: 12 month outcomes. Nursing Research, 60, 173-181. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182159c8f Hanson, C. L., Henggeler, S. W., Harris, M. A., Burghen, G. A., & Moore, M. (1989). Family system variables and the health status of adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psy- chology, 8, 239-253. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.8.2.239 Hartemann-Heurtier, A., Sultan, S., Sachon, C., Bosquet, F., & Gri- maldi, A. (2001). How type 1 diabetic patients with good or poor glycemic control cope with diabetes-related stress. Diabetic Medi- cine, 27, 553-559. Hauser, S. T., Jacobson, A. M., Lavori, P., Wolfsdorf, J. I., Herskowitz, R. D., Milley, J. E. et al. (1990). Adherence among children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus over a four-year longitudinal follow-up: II. Immediate and long-term linkages with the family milieu. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 15 , 527-542. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.527 Helgeson, V. S., & Palladino, D. K. (2012). Agentic and communal traits and health: Adolescents with and without diabetes. Peer & So- cial Psychology Bulletin, 38, 415-428. doi:10.1177/0146167211427149 Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., Siminerio, L., Escobar, O., & Becker, D. (2008). Parent and adolescent distribution of responsibility for diabetes self-care: Links to health outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33, 497-508. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm081 Herge, W. M., Streisand, R., Chen, R., Homes, C., Kumar, A., & Mackey, E. (2012). Family and youth factors associated with health beliefs and health outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37 , 980-989. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jss067 Hilliard, M. E., Harris, M. A., & Weissberg-Benchell, J. (2012). Dia- betes resilience: A model of risk and protection in Type 1 Diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports, 12, 739-748. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0314-3 Hood, K. K., Peterson, C., Rohan, J., & Drotar, D. (2009). Association between adherence and glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 124, e1171-e1179. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0207 Horton, D., Berg, C. A., Butner, J., & Wiebe, D. J. (2009). The role of parental monitoring in metabolic control: Effect of adherence and externalizing behaviors during adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 1008-1018. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp022 Hummer, K., Vannatta, J., & Thompson, D. (2011). Locus of control and metabolic control of diabetes: A meta-analysis. The Diabetes Educator, 37, 104-110. doi:10.1177/0145721710388425 Iannotti, R. J., Schneider, S., Nansel, T. R., Haynie, D. L., Plotnick, L. P., Clark, L. M. et al. (2006). Self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and diabetes self-management in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27, 98-105. doi:10.1097/00004703-200604000-00003 Jacobson, A. M., Hauser, S. T., Lavori, P., Willett, J. B., Cole, C. F., Wolfsdorf, J. I. et al. (1994). Family environment and glycemic con- trol: A four-year prospective study of children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Psychosomatic Medicine, 56, 401-409. Jaser, S. S., Faulkner, M. S., Whittemore, R., Jeon, S., Murphy, K., Delamater, A. et al. (2012). Coping, self-management, and adapta- tion in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Annals of Behavioral Medi- cine, 43, 311-319. doi:10.1007/s12160-012-9343-z Jaser, S. S., & White, L. E. (2011). Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 335- 342. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01184.x Johnston-Brooks, C. H., Lewis, M. A., & Garg, S. (2002). Self-efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with Type I diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 6 4 , 43-51. Kichler, J. C., Kaugars, A. S., Maglio, K., & Alemzadeh, R. (2012). Exploratory analysis of the relationships among different methods of assessing adherence and glycemic control in youth with type 1 dia- betes mellitus. Health Psychology, 31, 35-42. doi:10.1037/a0024704 Kneckt, M. C., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S. M., Knuuttila, M. L., & Syrjälä, A. M. (2001). Self-esteem as a characteristic of adherence to diabetes and dental self-care regimens. Journal of Clinical Perio- dontology, 28, 175-180. doi:10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028002175.x La Greca, A. M., Swales, T., Klemp, S., Madigan, S., & Skyler, J. (1995). Adolescents with diabetes: Gender differences in psychoso- cial functioning and glycemic control. Child Health Care, 24, 61-78. doi:10.1207/s15326888chc2401_6 Laffel, L. M., Connell, A., Vangsness, L., Goebel-Fabbri, A., Mansfield, A., & Anderson, B. J. (2003). General quality of life in youth with type 1 diabetes: Relationship to patient management and diabe- tes-specific family conflict. Diabetes Care, 26, 3067-3073. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.11.3067 Laffel, L. M., Vangsness, L., Connell, A., Goebel-Fabbri, A., Butler, D., & Anderson, B. J. (2003). Impact of ambulatory, family-focused teamwork intervention on glycemic control in youth with type 1 dia- betes. Journal of Pediat ric s, 142, 409-416. doi:10.1067/mpd.2003.138 Lane, J. D., McCaskill, C. C., Williams, P. G., Parekh, P. I., Feinglos, M. N., & Surwit, R. S. (2000). Personality correlates of glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 23, 1321-1325. doi:10.2337/diacare.23.9.1321 Lloyd, S. M., Cantell, M., Pacaud, D., Crawford, S., & Dewey, D. (2009). Brief report: Hope, perceived maternal empathy, medical regimen adherence, and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 1025-1029. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn141 Lundman, B., & Norberg, A. (1993). The significance of a sense of coherence for subjective health in persons with insulin-dependent diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18, 381-386. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18030381.x Luyckx, K., Vanhalst, J., Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Weets, I. (2010). A typology of coping with Type 1 diabetes in emerging adulthood: as- sociations with demographic, psychological, and clinical parameters. Journal of Behavioral Medici ne , 33, 228-238. doi:10.1007/s10865-010-9249-9 Meevissen, Y. M., Peters, M. L., & Alberts, H. J. (2011). Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: Effects of a two week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry, 42, 371-378. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.012 Modi, A. C., Pai, A. L., Hommel, K. A., Hood, K. K., Cortina, S., Hil- liard, M. E. et al. (2012). Pediatric self-management: A framework for research, practice, and policy. Pe diatrics, 1 29, e473-485. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1635 Monaghan, M., Horn, I. B., Alvarez, V., Cogen, F. R., & Streisand, R. (2012). Authoritative parenting, parenting stress, and self-care in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1123  J. P. YI-FRAZIER ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1124 pre-adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Psychol Med Settings, 19, 255-261. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9284-x Murray-Swank, A., Goldberg, R., Dickerson, F., Medoff, D., Wohl- heiter, K., & Dixon, L. (2007). Correlates of religious service atten- dance and contact with religious leaders among persons with co-occurring serious mental illness and type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1 9, 282-288. Nakahara, R., Yoshiuchi, K., Kumano, H., Hara, Y., Suematsu, H., & Kuboki, T. (2006). Prospective study on influence of psychosocial factors on glycemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Psychosomatics, 47, 240-246. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.240 O'Hea, E. L., Moon, S., Grothe, K. B., Boudreaux, E., Bodenlos, J. S., Wallston, K. et al. (2009). The interaction of locus of control, self-efficacy, and outcome expectancy in relation to HbA1c in medi- cally underserved individuals with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Be- havioral Medicine, 32, 106-117. doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9188-x Palmer, D. L., Osborn, P., King, P. S., Berg, C. A., Butler, J., Butner, J. et al. (2011). The structure of parental involvement and relations to disease management for youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pedi- atric Psychology, 36, 596-605. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq019 Perfect, M. M., & Jaramillo, E. (2012). Relations between resiliency, diabetes-related quality of life, and disease markers to school-related outcomes in adolescents with diabetes. School Psychology Quarterly, 27, 29-40. doi:10.1037/a0027984 Petitti, D. B., Klingensmith, G. J., Bell, R. A., Andrews, J. S., Dabelea, D., Imperatore, G. et al. (2009). Glycemic control in youth with dia- betes: The SEARCH for diabetes in Youth Study. Journal of Pediat- rics, 155, 668-672. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.05.025 Polonsky, W. H. (1996). Understanding and treating patients with dia- betes burnout. In B. J. Anderson, & R. R. Rubin (Eds.), Practical psychology for diabet e s c l in i c i a n s (pp. 183-191). Alexandria: ADA. Richardson, A., Adner, N., & Nordström, G. (2001). Persons with insu- lin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Acceptance and coping ability. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 758-763. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01717.x Schneider, S., Iannotti, R. J., Nansel, T. R., Haynie, D. L., Sobel, D. O., & Simons-Morton, B. (2009). Assessment of an illness-specific di- mension of self-esteem in youths with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34 , 283-293. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn078 Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5-14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 Silverstein, J., Klingensmith, G., Copeland, K., Plotnick, L., Kaufman, F., Laffel, L. et al. (2005). Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Dia- betes Care, 28, 186-212. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.186 Smalls, B. L., Walker, R. J., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., Campbell, J. A., Davis, K. S., & Egede, L. E. (2012). Associations between coping, diabetes knowledge, medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with type 2 diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34, 385- 389. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.018 Van der Heijden, M. M., Pouwer, F., Romeijnders, A. C., & Pop, V. J. (2012). Testing the effectiveness of a self-efficacy based exercise in- tervention for inactive people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Design of a controlled clinical trial. BMC Public Health, 12, 331. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-331 Venkataraman, K., Kannan, A. T., Kalra, O. P., Gambhir, J. K., Sharma, A. K., Sundaram, K. R. et al. (2012). Diabetes self-efficacy strongly influences actual control of diabetes in patients attending a tertiary hospital in India. Journa l of C om m unity Health, 37, 653-662. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9496-x Vollrath, M. E., Landolt, M. A., Gnehm, H. E., Laimbacher, J., & Sennhauser, F. H. (2007). Child and parental personality are associ- ated with glycaemic control in Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 24, 1028-1033. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02215.x Weinger, K., Butler, H. A., Welch, G. W., & La Greca, A. M. (2005). Measuring diabetes self-care: A psychometric analysis of the Self- Care Inventory-revised with adults. Diabetes Care, 28, 1346-1352. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.6.1346 Wheeler, K., Wagaman, A., & McCord, D. (2012). Personality traits as predictors of adherence in adolescents with type I diabetes. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psych iatr ic Nursing, 25, 66-74. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6171.2012.00329.x Wu, S. F., Lee, M. C., Liang, S. Y., Lu, Y. Y., Wang, T. J., & Tung, H. H. (2011). Effectiveness of a self-efficacy program for persons with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13, 335-343. Wysocki, T. (2002). Parents, teens, and diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum, 15, 6-8. doi:10.2337/diaspect.15.1.6 Wysocki, T., Harris, M. A., Buckloh, L. M., Mertlich, D., Lochrie, A. S., Mauras, N. et al. (2007). Randomized trial of behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes: Maintenance of effects on diabetes outcomes in adolescents. Diabetes Care, 30, 555-560. doi:10.2337/dc06-1613 Wysocki, T., Harris, M. A., Buckloh, L. M., Mertlich, D., Lochrie, A. S., Taylor, A. et al. (2008). Randomized, controlled trial of behav- ioral family systems therapy for diabetes: Maintenance and generali- zation of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behavior The- rapy, 39, 33-46. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.001 Wysocki, T., Lochrie, A., Antal, H., & Buckloh, L. M. (2011). Youth and parent knowledge and communication about major complica- tions of type 1 diabetes: Associations with diabetes outcomes. Dia- betes Care, 34, 1701-1705. doi:10.2337/dc11-0577 Wysocki, T., Nansel, T. R., Holmbeck, G. N., Chen, R., Laffel, L., Anderson, B. J. et al. (2009). Collaborative involvement of primary and secondary caregivers: Associations with youths’ diabetes out- comes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 869-881. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn136 Yi-Frazier, J. P., Smith, R. E., Vitaliano, P. P., Yi, J. C., Mai, S., Hill- man, M. et al. (2010). A person-focused analysis of resilience re- sources and coping in diabetes patients. Stress and Health, 2 6, 51-60. doi:10.1002/smi.1258 Yi, J. P., Vitaliano, P. P., Smith, R. E., Yi, J. C., & Weinger, K. (2008). The role of resilience on psychological adjustment and physical health in patients with diabetes. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 311-325. doi:10.1348/135910707X186994 Zulman, D. M., Rosland, A. M., Choi, H., Langa, K. M., & Heisler, M. (2012). The influence of diabetes psychosocial attributes and self- management practices on change in diabetes status. Patient Educa- tion and Counseling, 87, 74-80. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.013

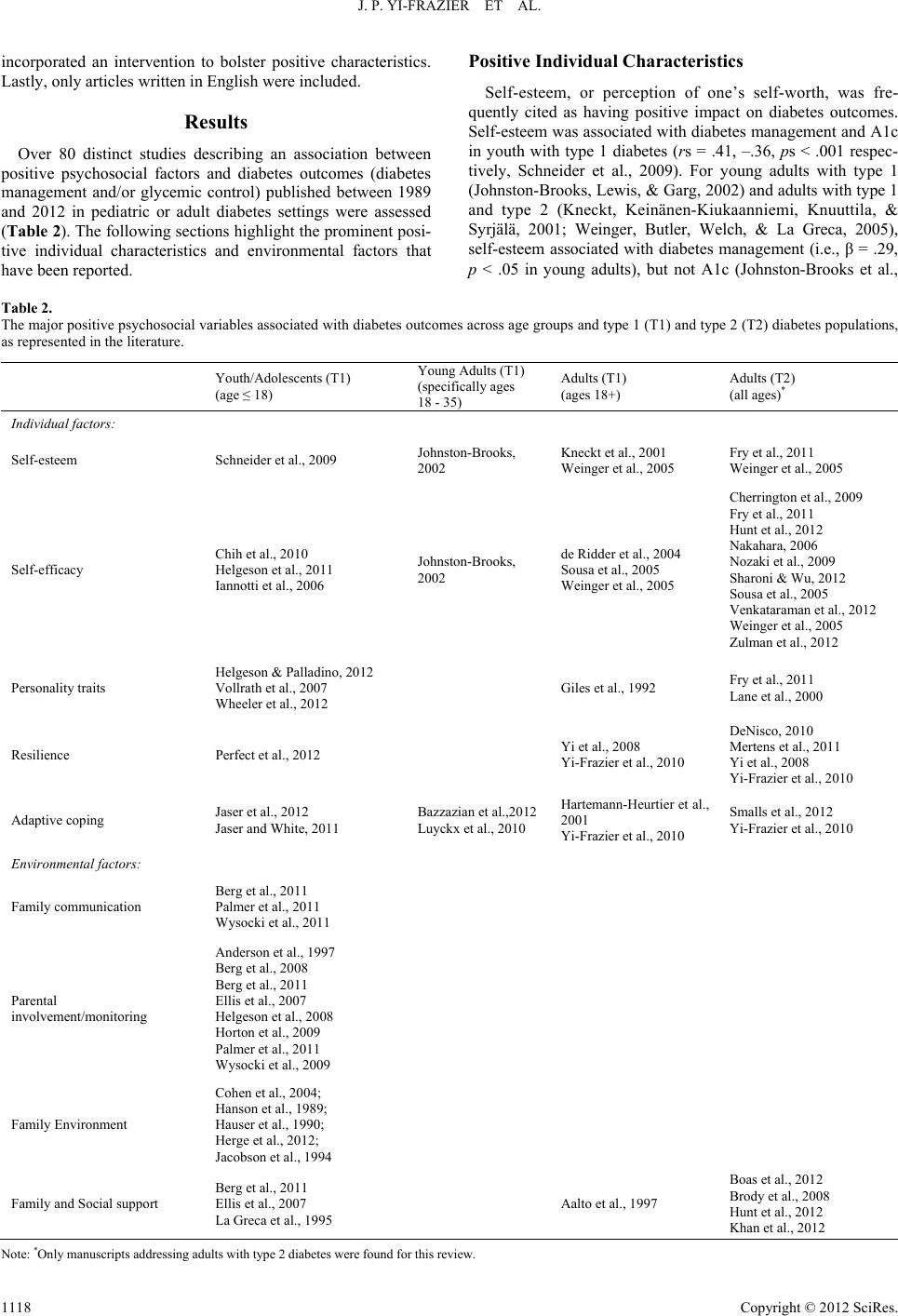

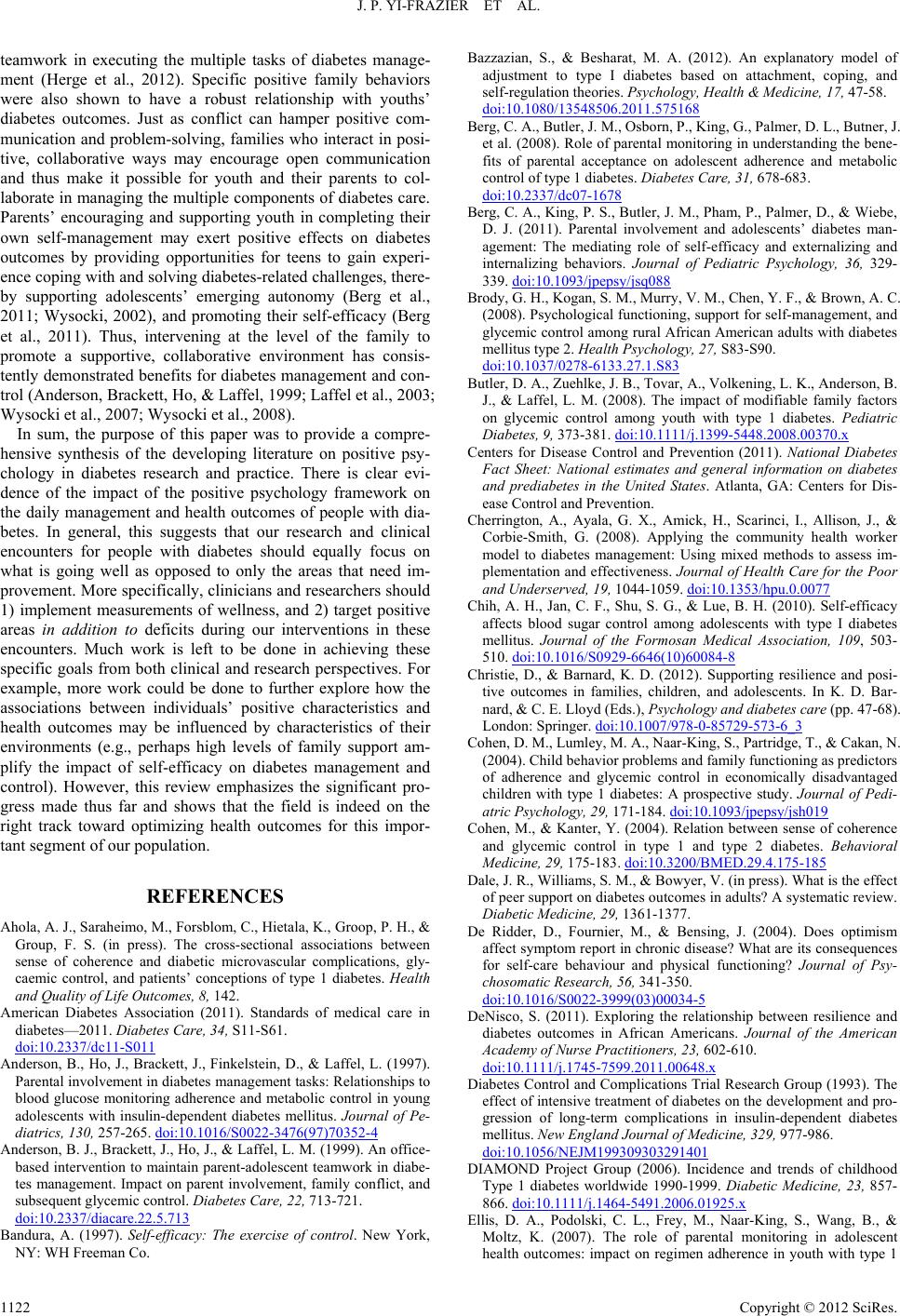

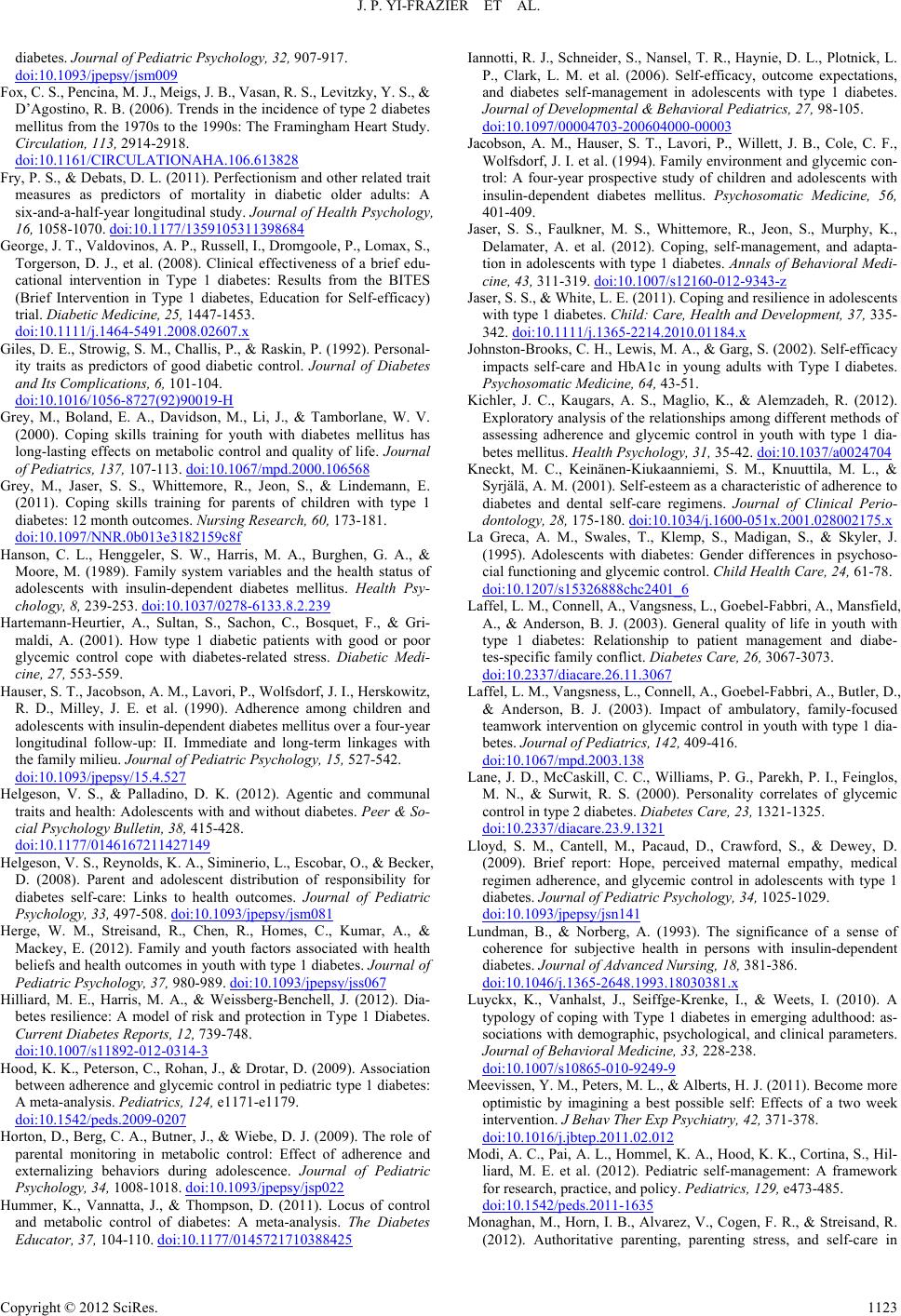

|